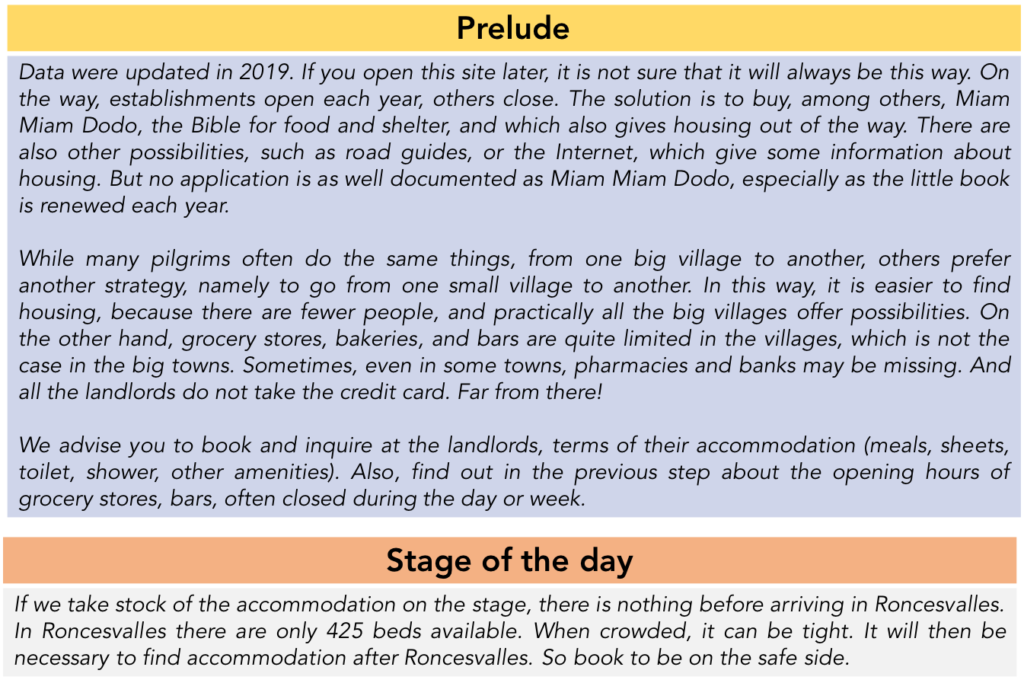

Viva España in the rain or good weather

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

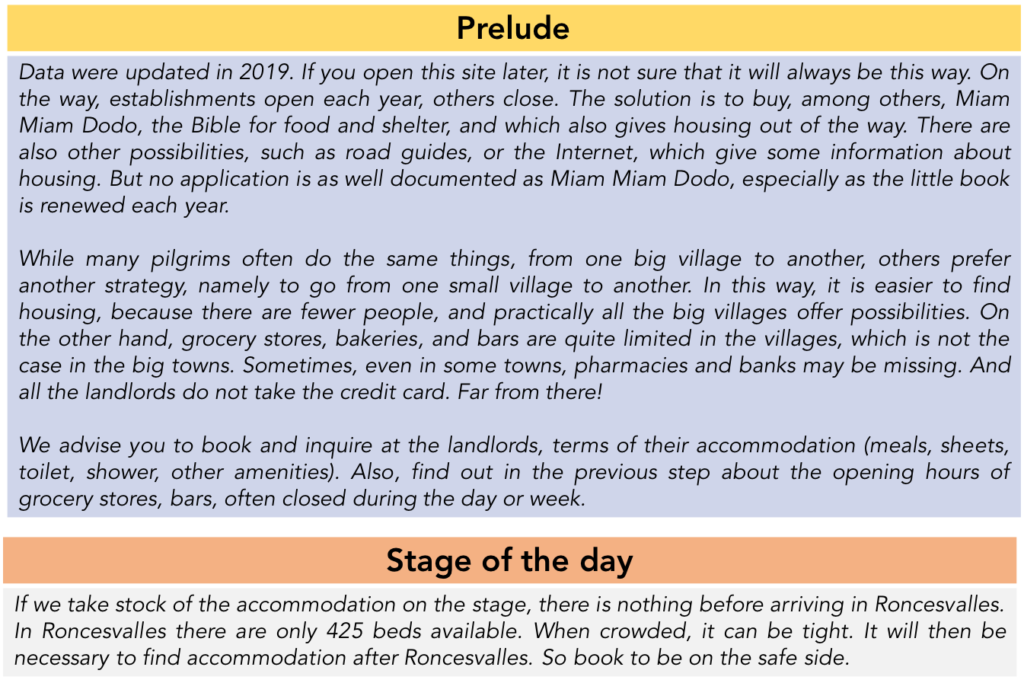

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-st-jean-pied-de-port-a-roncevaux-par-le-gr65-31352108

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

The Compostela pilgrimage, proclaimed in 1987 as the “First European Cultural Route” by the Council of Europe, has become a worldwide phenomenon, bringing together people of over 120 nationalities. The film The Way, shown in Anglo-Saxon countries, has done a lot in the growth of the number of pilgrims in recent years, particularly from Canada, Australia and the United States..

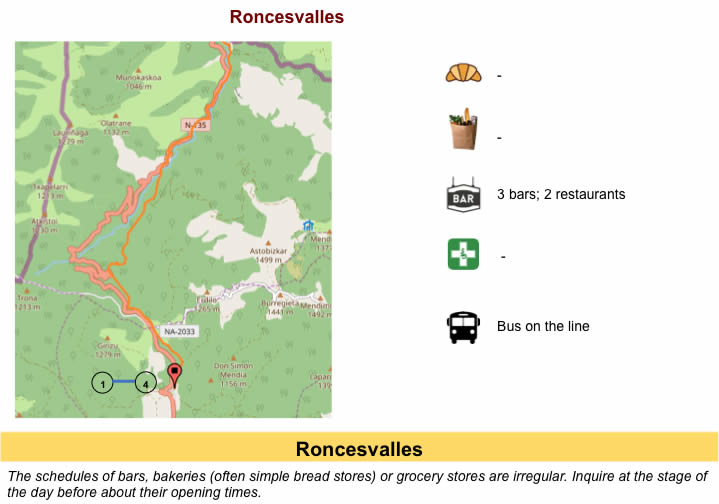

You have to read between the lines the difficult statistics of France and Spain to try to understand the flow of pilgrims across the border. Around 4,000 people arrive each month in St Jean-Pied-de-Port in the village, or between 100 and 150 per day. More than 250,000 pilgrims travel to St Jacques de Compostela each year. They obviously do not all leave from France. The Spaniards say that in 2013, 29,344 (or 12.34%) pilgrims started the journey in Saint-Jean Pied-de-Port, 8,268 (or 3.9%) having started from Roncesvalles. The others left from all the Spanish stages on the way to Santiago. In the busiest months, namely May and September, 9,000 pilgrims leave each month from St Jean-Pied-de-Port, or around 300 per day. This means that the flow in St Jean Pied-de-Port doubles on average compared to that of Via Podiensis. And it all depends on the days. Monday is often the busiest day, as those starting their trip to St Jean-Pied-de-Port often arrive here on weekends. Therefore, on certain days, you may have daily peaks of nearly 500 people in Roncesvalles. Further on, in Spain, there will often be more than 1,000 per day on the way, sometimes even 2,000 near Santiago.

The passage over the Pyrenees to Spain is a magnificent stage, outside the box, even if it requires a sustained effort, rarely undertaken so far on the course beyond Le Puy. The climb to Bentarte Pass is practiced in a landscape of arid moors, where sheep frolic, but also where vultures soar, which spot fragile sheep. And what about the descent to Roncesvalles. Beautiful in a large beech forest, but so difficult in bad weather. But there! It often rains on the Pyrenees, and then the course can become very difficult. Also, we will describe here this course, made at two different times, in the rain and the good weather. We will show the first part of the route in bad weather, the second in good weather, sometimes showing places where the images are mixed, to show you, but you also know it, that the rain or the sun radically change your state of spirit and the memory that you will keep of this queen stage of the Way of Compostela. It goes without saying that we rather wish you the sun when you walk here.

Difficulty of the course: It is a tough stage, with rare moments of respite, both uphill to the Bentarte Pass and down to Roncesvalles, beyond Leopeder Pass. This is the most dreaded stopover for pilgrims. But, when you have already crossed France on foot, it is not insurmountable. Slope variations (+1353 meters/-587 meters) are far from being a trifle. The most severe slopes are beyond Huntto, uphill, and especially in the forest of Roncesvalles, downhill.

The climb to the Pyrenees takes place almost entirely on tar. On the other hand, when you reach the heights, in Spain, the dirt roads rule:

- Paved roads: 14.0 km

- Dirt roads: 10.0 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

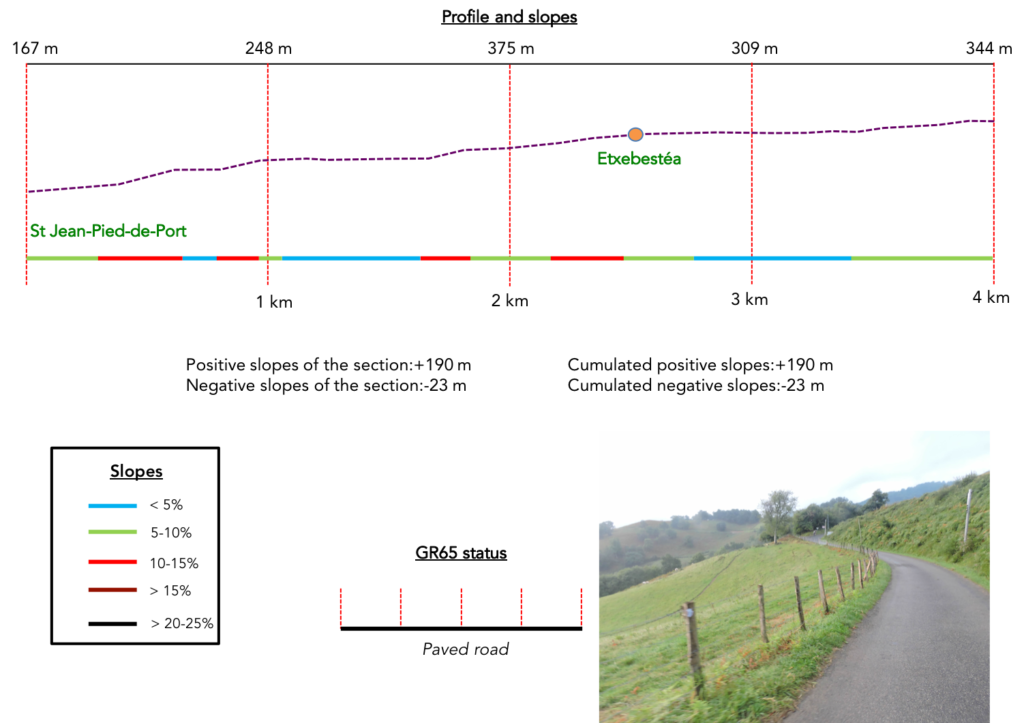

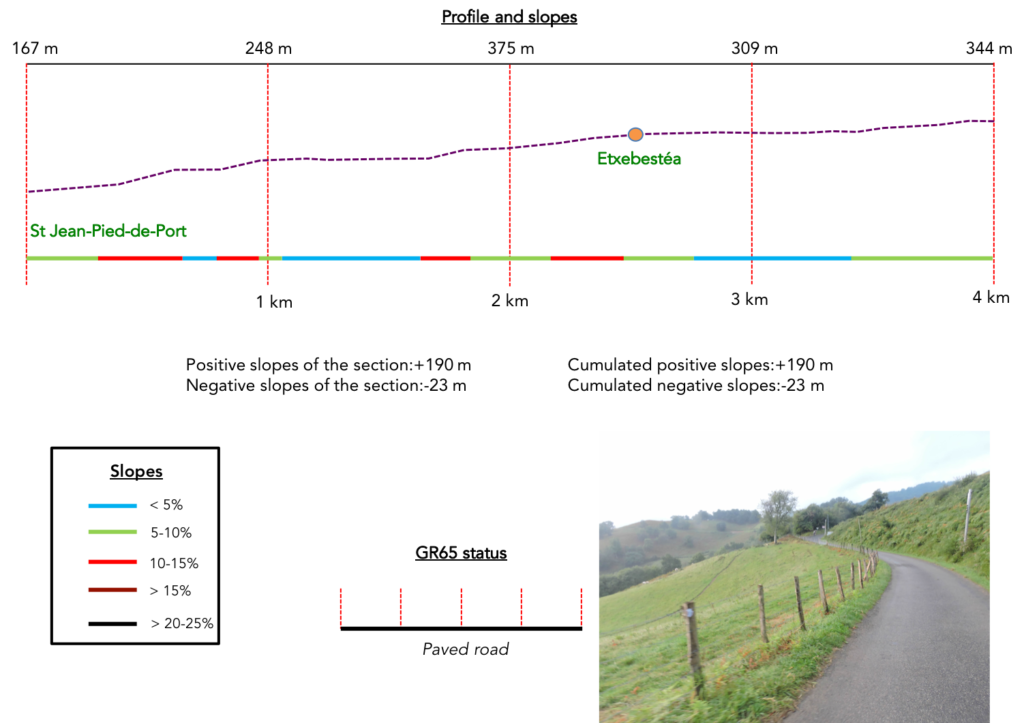

Section 1: An exit from St Jean-Pied-de-Port which announces a steep slope.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: at the beginning, the slope is quite bearable.

The first time we passed here, that night the weather had become gloomy in St Jean Pied-de-Port. We had spent the night in accommodation on rue du Maréchal Harispe, a street which climbs steeply at the exit of the city, heralding strong slopes. You will quickly see how the lives of the hundreds of pilgrims who leave for Roncesvalles are organized. It is still dark, around 5 a.m. You hear the characteristic screeching of trekking poles clawing the tar on the sloping street. You open one eye, surprised, ajar the shutters. Headlamps cast a pale shadow on the surrounding walls. A fine rain is falling, so fine that you can hardly see it in the halos of the lamps. Some pilgrims like to leave early, regardless of the conditions. But do you still have to be able to read the directions of the GR on the way? The headlamp light will do what is necessary. Wrapped up in their oilskin, their cape, their poncho, their windbreaker or their Gortex jacket, the pilgrims move forward in silence, rain in their eyes.

Your mood is not breaking records. You have in front of you the most beautiful stage of the Camino de Santiago, one that all pilgrims expect as much as they fear. You’ll probably have to go with a less light heart, soak up the sly humidity, listen to the music of the drops of water falling from your hat onto your face, then into the puddles. You also already know that all that plastic covering you and your bag will limit your horizon, that your soles will splash in the puddles and that the insidious mud will stick you to the shoes. How warm it is in your bed! You will be returning soon. But not for eternity! “Everything comes at the right time for those who know how to wait” is probably not the best saying adapted to the toil of the pilgrim. Whether the hour strikes or does not strike, you must always leave, whatever fate awaits the pilgrim. For now, God, Allah and Zeus have not agreed to give the pilgrim some respite.

| And already, in the morning, there is a crowd at the office of the pilgrims, who come for information. For many reasons, including the weather, the conditions of the route, the accommodation, but also to bring the “credencial”, the passport of the pilgrims, for those who start the journey here, and this is the majority. The street where the guestrooms and shops stand against each other is still quite empty. It all depends on your departure time. |

|

|

| The route starts from the center, near the church and the clock tower on the river. |

|

|

| The pavement is slippery, dripping with rain, and the street climbs towards the Porte d’Espagne, where large car parks are grouped. |

|

|

At the Porte d’Espagne, track organizers offer you the program: 4h30 for the Bentarte Pass, 6h35 for Roncesvalles. The pilgrims bat their eyelashes, because here the altitude is 173 m, and it will be necessary to climb to more than 1,500 meters.

| So, here, it’s the last moment of the choice: the easier way (well, easy, so to speak) towards Valcarlos, the Winter Way, or the Napoleon Road, the only real way, that of the pilgrims in their wildest dreams. |

|

|

It happens that in terrible weather, with snow at the rendezvous, this route is closed, but this does not bother all the pilgrims.

| At the beginning of the Napoleon road, the route follows the Rue du Maréchal Harispe, a very pleasant street with almost a 20% gradient. The pilgrim is quickly put to the exercise, without preliminaries. |

|

|

| The crowd of pilgrims is already on the march. You have to pass the first ramp of Portaleburu at the exit of the village, in the middle of the lodgings and the guestrooms which drag on, on the height. These accommodations are often taken by pilgrims who have not found a place at the bottom of the town or by those who want to take advantage of already taking a little height. |

|

|

Further up, the road arrives at Ithurburua, at an altitude of 230 meters, we will say the real start of the Napoleon road. Here, the program is annonced. Roncesvalles (Orreaga) is 23.6 kilometers away and the Franco-Spanish border only 15.4 kilometers away. 4h 20 walk to reach the pass.

| The road zigzags here again in the middle of the guest rooms, and the slope becomes steeper again |

|

|

| Further up, the slope decreases a little towards Othatzenea and accommodation soon becomes scarce. |

|

|

In the Pyrenees, the weather can change in less time than it takes to write it down. A very fine rain hums drops of music that rhythmically beat on the pilgrims’ raincoats. Here, the cyclist does not care. He is still straight, proud on his bicycle. It won’t last. The slope will quickly swell, becoming unbearable to his muscles. Even the Tour de France cannot pass through here.

| Further up, the road leaves more and more houses until it reaches Etxebestéa, before the Route Napoléon climbs more steeply towards Huntto. |

|

|

| It’s not just pilgrims here. The Manech sheep pay little attention to the drizzle. They’re used to it. |

|

|

Over there, at the bottom of the valley, St Jean-Pied-de-Port wakes up.

| Further ahead, GR path climbs steeply in the bends of the road. Now, there is no real sky or horizon, because the mist seeps in, insinuates itself until the differences are erased in a cottony blur. Pilgrims are sometimes like beads of a rosary lost in the bends of the road. |

|

|

| Up there are the houses of Huntto |

|

|

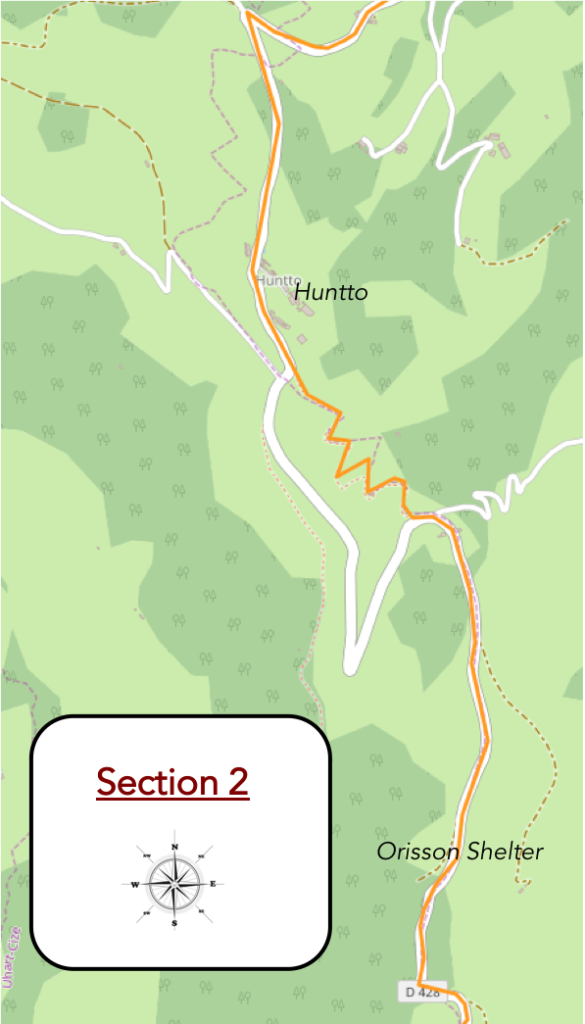

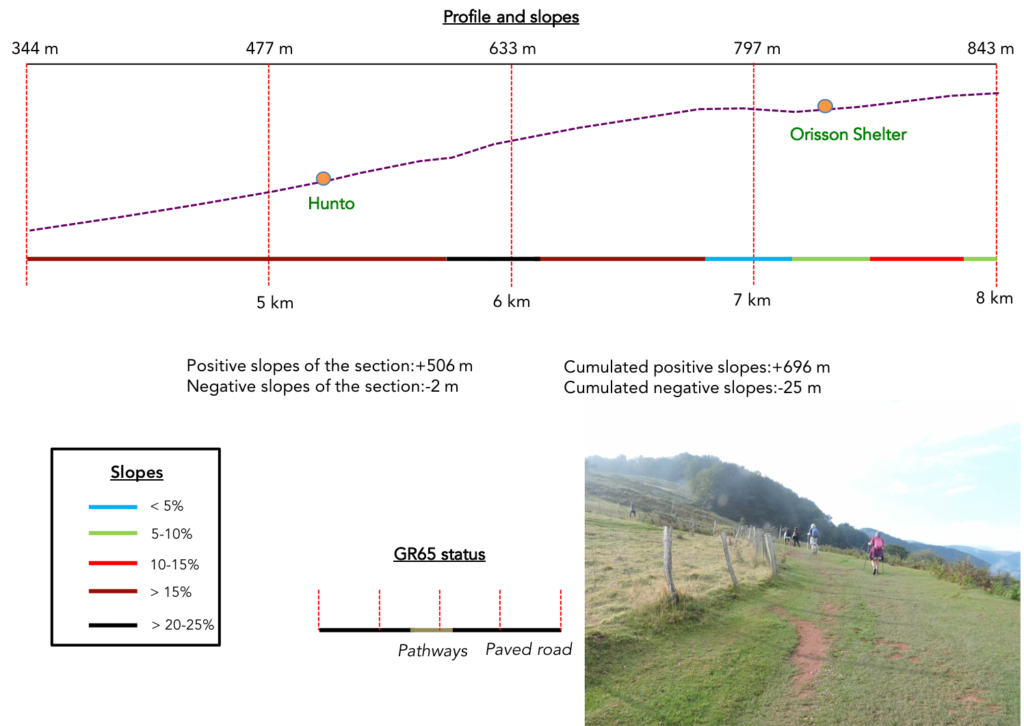

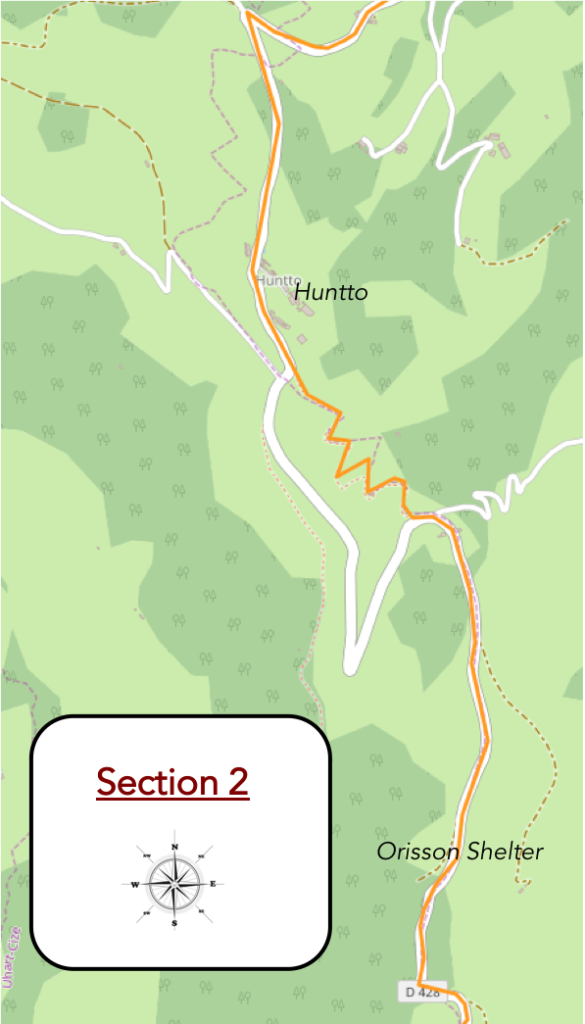

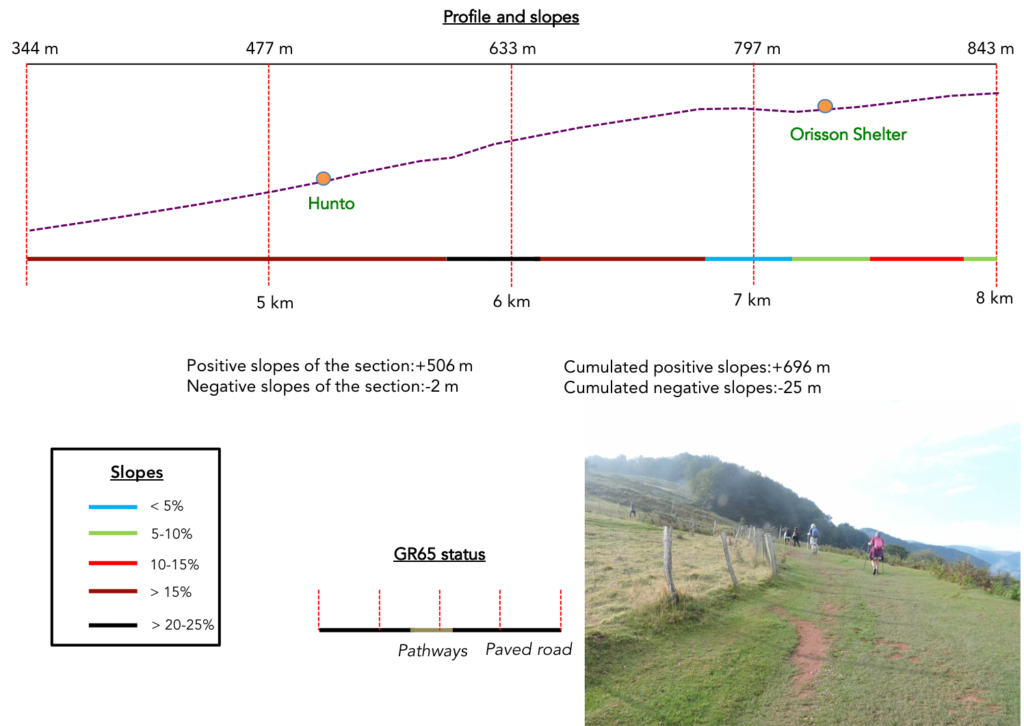

Section 2: In the pain of the Huntto and Orisson bends.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: the most tough passage of the stage, with slopes clearly above 15%, sometimes with a little rare respite.

| Like anonymous silhouettes trapped in the curls of a smoky Scottish bar, the pilgrims move forward, bending under the weight of their bags on the laces that stretch out in the green Basque meadow. A lady, quite old, fairly wrapped up, will probably not reach the pass today. On the other hand, for the red-headed Manech, no matter the drizzle or the slope. Under their drooping woolen fleece, it’s the high life. Climb, descend, graze, graze, and graze again until they present their udders to allow the production of such a good Ossau-Iraty cheese. |

|

|

| And the road gets longer, more and more steep. You knew it was no surprise, but very steep, until you got to Huntto, its little houses and its bar. Some pilgrims may have stayed here to shorten the stage. You have in fact already taken more than 350 meters in height since the start. Total happiness, for a first coffee after breakfast. Warm. Rain that suddenly stopped almost by magic. The gods have come to an agreement. For the moment. |

|

|

| A little above Huntto, GR path arrives at a somewhat strategic crossroads. The paved road goes off to the right. Few pilgrims take this route, which cyclists tend to follow. Pilgrims prefer the pathway that climbs straight ahead. When we say straight ahead, that’s a way of saying it. This pathway, winding and stony at will, likes to walk its visitors with more than 30% of slope in places.

Do pilgrims sense it, know it or anticipate it? Still, they wisely put away their rain gear and rolled up their sleeves. It looks like summer! And yet, the stubborn, sly mist flows from the valley to imprison the mountain, even if you have the feeling that the time is about to rise. It must be tricky to ensure the weather in the region. |

|

|

It’s almost a kilometer to swallow on the gray red limestone pebbles, in the middle of ferns charred by the summer heatwave. The slope is so severe that the pilgrims often dawdle, stop, then set off again, taking the opportunity to glance back to be satisfied with their duty already accomplished. Almost of the enjoyment can be read on certain looks. Indeed, Huntto gradually disappears below the hill. St Jean de Pied-de-Port, at the far end, is no longer within gun range, either.

| Almost always then comes that blessed moment that nature has provided for poor walkers. The slope softens and the soles take comfort on the soft grass. The grass is so green, so short that you could play golf on it. So, some pilgrims take out their cell phones. Others stuck their noses up, almost humming songs. You may even meet Asians “doing push-ups” to relax after exercise. From here you will sometimes have the feeling of walking in South Korea, all the way to Santiago. All of humanity is on its way to Santiago. |

|

|

| A little up, the road and the pathway meet again, near an annex of Orisson refuge. There are so many pilgrims who want to spend the night at the refuge, that the owners have been forced to expand. But beware! The refuge is still a good kilometer from here. Here, pilgrims enjoy viewing the valley on a planisphere. What happiness! It’s clearing up. The sky is visibly blue. Long live Roncesvalles! |

|

|

| Here, the slope becomes a little more human, and you have the choice of walking on the tar or on the grass. The weather is almost fine, and yet it is better to look around to get a better idea. At the next bend in the road, disaster looms. The mountain people know the premises well. When the fog comes up the valley and clings to the spruces, the mist begins to blur the horizon, the rain is not far away. Space can thus remain silent, as if paralyzed, for long hours, even days. But all it takes is a small spark, a gust of wind for example, for nature to lash out. |

|

|

You know very well that “Morning rain does not stop the pilgrim”. No more here than elsewhere. As the slope has become more human, the pilgrims, who are not convicts, often stop to take in the landscapes, casting a rarely worried gaze on the horizon. They are not like the peasants who watch with their black eyes the storm that will destroy their harvest.

| Because for a few moments now, the fog has risen a little higher and densified on the mountain. And the road slopes up again … |

|

|

| … until reaching Orisson refuge, stormed by the pilgrims. A few rare pilgrims spend the night here, which allows to split the difference. It’s better, of course, to book in advance. There are not many places available.

As for the climate of the day, the wind must have turned in another direction, because at the refuge, it is almost the sun that appears. People are dining on the terrace in the sun, with their sleeves rolled up. |

|

|

| There are crowds here. You do not know what language to speak. Korean, Portuguese, German, Turkish, the choice is yours! The restaurateurs, on the other hand, speak broken English, like many pilgrims elsewhere. The queue for the toilets is endless. Here is the last sign of civilization before Roncesvalles. |

|

|

| Our South Korean friends have a big smile. This is the start of the road for them and they love to pose for the photographer. |

|

|

| Can we leave you with a mixed impression of such a beautiful stage partly evaded by the rain? No, and for that you just have to repeat the stage, another time, for example if luck is with you, on a sunny day. Many pilgrims have been bitten by Compostela, and have made the journey several times. By practicing in this way, we then know quite precisely where the difficulties of the track are, the time which is necessary to arrive at the end of the stage. However, there are a series of uncontrollable parameters, including the weather and the general condition of your engine. Therefore, if you have done Roncesvalles once, you learn that it is better to leave later, when the horde of pilgrims has already started on the way for a long time. Not that the crowd of pilgrims on the mountain is something unpleasant, but isn’t it magical to be able to walk almost alone in the splendor of the bare mountain?

Here, under the sun, later in the morning the refuge of Orisson, in the morning usually so crowded. Only a few tourists, who do not make the journey, drink coffee on the terrace. Donkeys are no longer bothered by the line of pilgrims waiting outside the bathroom door. |

|

|

| You are at an altitude of 810 meters, starting from 167 meters. It is still more than 700 meters of vertical drop in the knees and joints. Patience! There is still more than 600 meters of climb. The next scheduled stop is at the Virgin of Biakorri, 3.7 kilometers to here. |

|

|

| Beyond Orisson refuge, the slope becomes less steep than before. Finally, everything is relative on the tracks and mountain roads! It still climbs in places to over 15%, but the brain automatically decreases the degree of difficulty, when it is less steep. Are the old oak trees being cut here so that the cows can see the grass grow? The landscape here is often a rare steppe, with here and there a grove of trees, oaks above all. |

|

|

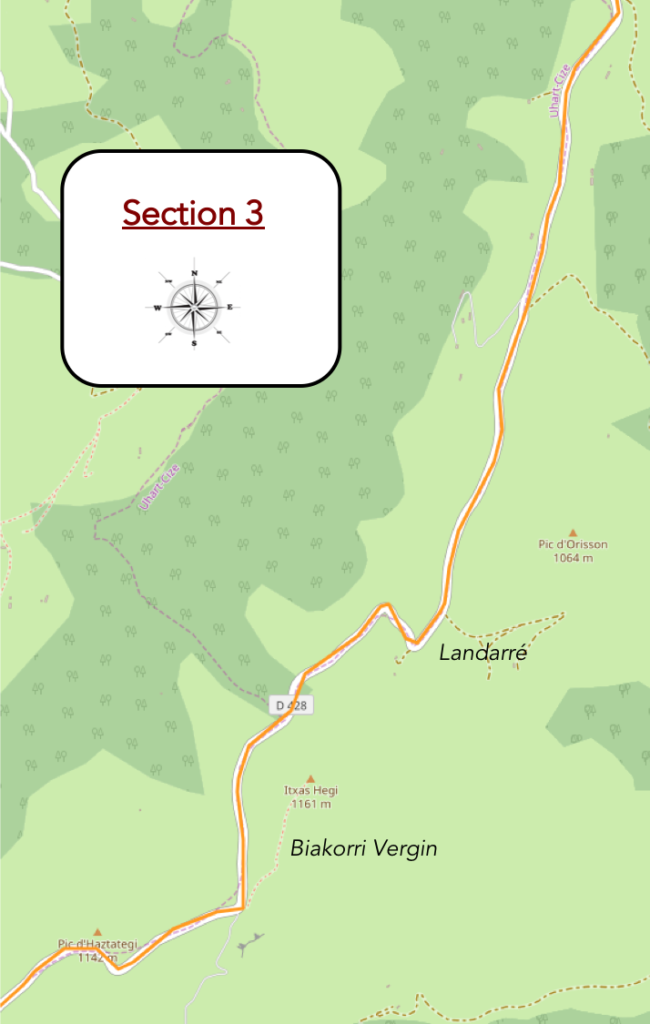

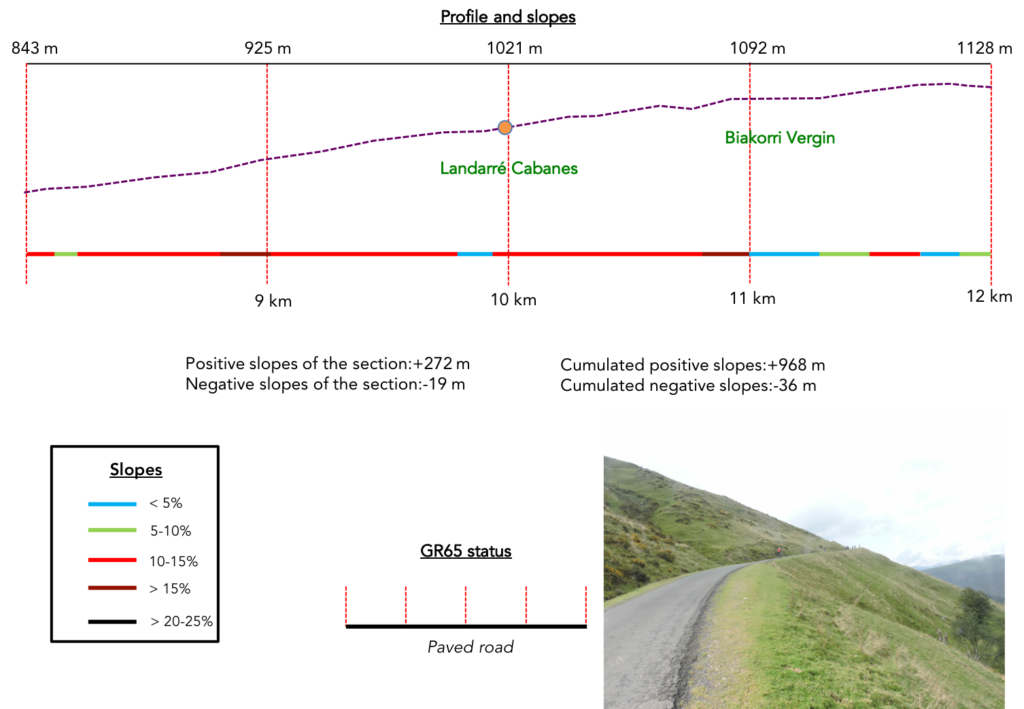

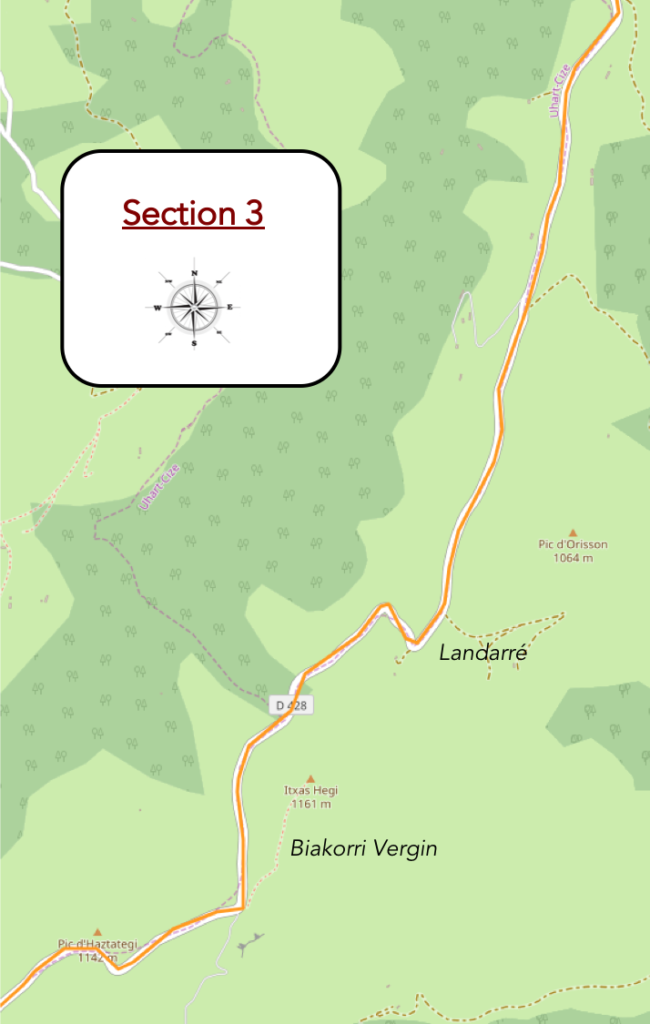

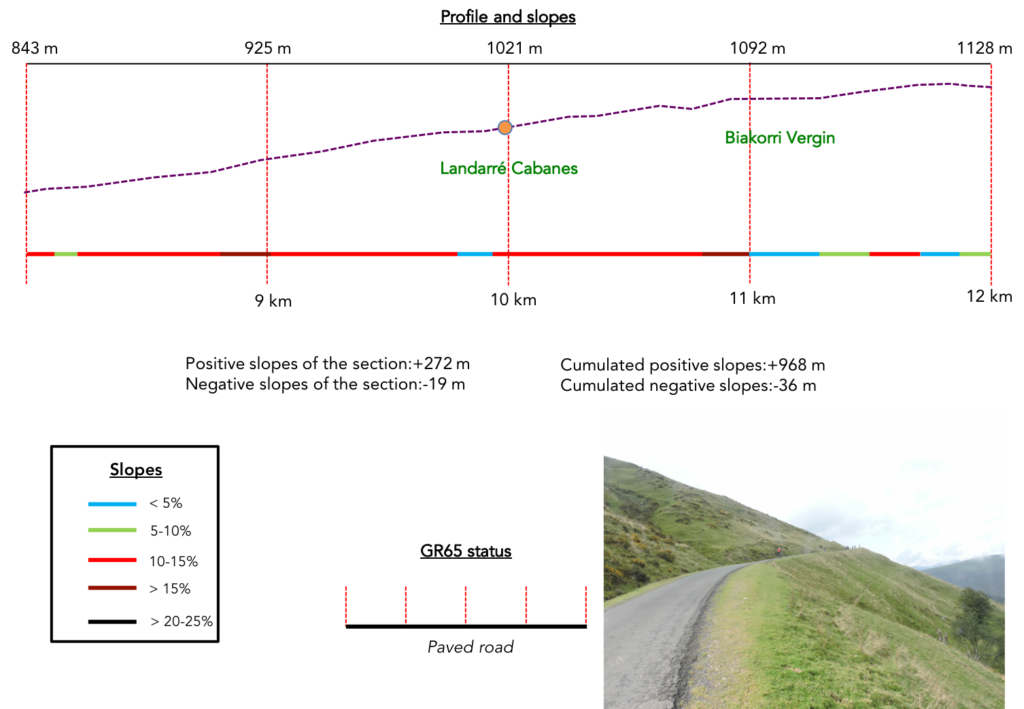

Section 3: In the splendor of the pastures, up there towards Orisson Virgin.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: in the previous section, we took almost 500 meters of height; here it will only be half!

| The pilgrims walk alone or in groups, it depends. Either way, the lyrics are muted, when the tongue hangs under the strain. Above all, do not feel when you pass here that the country is yours. The Basques work there too. Below the road, the oak grove is probably not only used for decoration. |

|

|

But the work of the locals, the pilgrim here does not care. Rather, it’s his lace that bothers him.

| And the road to climb tirelessly in the middle of withered broom, junipers and ferns. Sometimes you are alone in the world. Vegetation is becoming increasingly rare in the bare beauty of the mountain. Cows do not eat broom or ferns. Sheep love broom, but prefer young shoots in spring. Food made from broom is claimed to make them immune to viper bites. Ferns, they also appreciate them, but tender, at the edge of streams, not those branches dried by time and wind. Goats eat almost everything, but they don’t abound here.

When you’ll reach the ridge, you will have the feeling that the hardest part is behind you. And it is, momentarily. The slopes will not exceed 10% for a few hectometers, with sometimes even slight plateaus. |

|

|

| We are at the beginning of September. The beginning of summer is marked by the arrival of herds of sheep, cows and horses in the high pastures, the summer pastures, where the mountain flowers and the grass are richer than in the plains. This is the period of transhumance, as in Aubrac. From June, the bells ring out here, making the mountain sing. They choose calm animals, sheep or cows, which are draped around the neck of one of these little wonders. From there, it’s the Pavlovian reflex. The herd recognizes the sound of the mother bell and that one, following the cowbell wherever it goes. So, no more traffic jams on the way up and down the mountain pasture, no more cattle disappearing in the fog. Animal life is pretty simple, right? These beautiful young White Aquitaine cows disdain the broom within their reach. They probably know what is good. And they are not at the factory like their mothers in the plains. They are on vacation, in the great outdoors. Here, you will hardly meet the other breed of cows in the country, which is the Béarnaise cow. Here, the magnificent peasants left them their beautiful lyre-shaped horns. Cows aren’t just pintles, of course. |

|

|

| The road then reaches the Cabanes of Landarré. You climbed to 1020 meters, 200 meters higher than Orisson refuge. These huts are undoubtedly refuges for shepherds. While you may sometimes feel that all of these herds live independently, this is not quite the case. We know that more than 200 shepherds go pasture in Béarn Pyrenees. You hardly meet them and yet they are there, a bit like the gendarmes you never see, but almost certainly you meet when you accidentally run a red light.

Opposite, the mountain is a spectacle. When you live in your small, tight world, sometimes you feel dizzy with so much space. |

|

|

A little further up, on a plateau (yes there are some, but they are as rare as shepherds), a pilgrim has put his bicycle down at the foot of a cairn, to take a nap facing the Pyrenees. But yes, there is sun. Consider the shadow the bike casts on the grass. However, opposite, the Pyrenees get angry. It’s not just rising fog anymore. This time the barrier of clouds has become more and more compact, more threatening.

| And the road continues to climb through increasingly bare mountain pastures. Cycling here doesn’t get you any faster at the end of the stage. We left at the same time as this cyclist from St Jean-Pied-de-Port. Leaning over his handlebars, he, like the walker, has plenty of time to dive into this unique, almost unreal, completely naked world. Sometimes a rare vehicle passes, probably a shepherd who goes to see where his flock has gone. |

|

|

| On a neighboring hill appear small luminous points. They are sheep. The shepherd does not have to go there every day. Or maybe he is looking at them through binoculars? Unless the dogs see to it. |

|

|

| Further up, you can see a small plateau, so the pace of walking is accentuated a little, automatically. |

|

|

Then, again, the slope softens in the broom and short grass, with the Pyrenees straight in front of the eyes. Is it the ringing bell attached to the necks of horses that tells you that you have arrived in a strange world? A horse with a bell on its neck, would you have fallen into another universe?

| Today’s shepherds have changed the customs of their ancestors somewhat. Of course, they still proudly wear the Basque beret, but today they arrive by car, accompanied by their dog, most often little shepherds from the Pyrenees, with their hair that goes so far as to cover their shaved faces, these dogs that consider the herd as their family, protecting them from predators such as wolves or vultures. This shepherd has a family resemblance, that of old engravings of the Basque country. |

|

|

| Then in front of you, on a plateau, the pilgrims congregate again. The road arrives on the rock where Biakorri Virgin rests, also known as the Virgin of Orisson or the Virgin of the Shepherds. The statue was in a school in St Jean-Pied-de-Port in the XIXth century. More than 60 years ago, the local station master sealed this statue on the rock of Biakorri, the place “where the winds blow”, as said in Basque, a place known for its violent thunderstorms. It was necessary to protect the shepherds and the flocks from lightning and to guide the pilgrims in these lost places. A few years ago, the metal statue was struck down. They gave him his head. As the shepherds did not come down to mass every Sunday, the pastor went up there for the celebration. It has since become a pilgrimage on the Sunday following the feast of August 15. They pray for the flocks and for the shepherds. Consider the religiosity of the place, when you unpack your picnic here.

You may implore Our Lady, but the fog climbs tirelessly from the bottom of the valley. |

|

|

| Then the slope softens among the flocks of sheep on the low mountain. The pastures widen as you slope up. |

|

|

Further up, GR path even becomes generous, offering a small descent to its guests. The pilgrims then say to themselves that it was almost silly to make such a fuss about this dreaded stage.

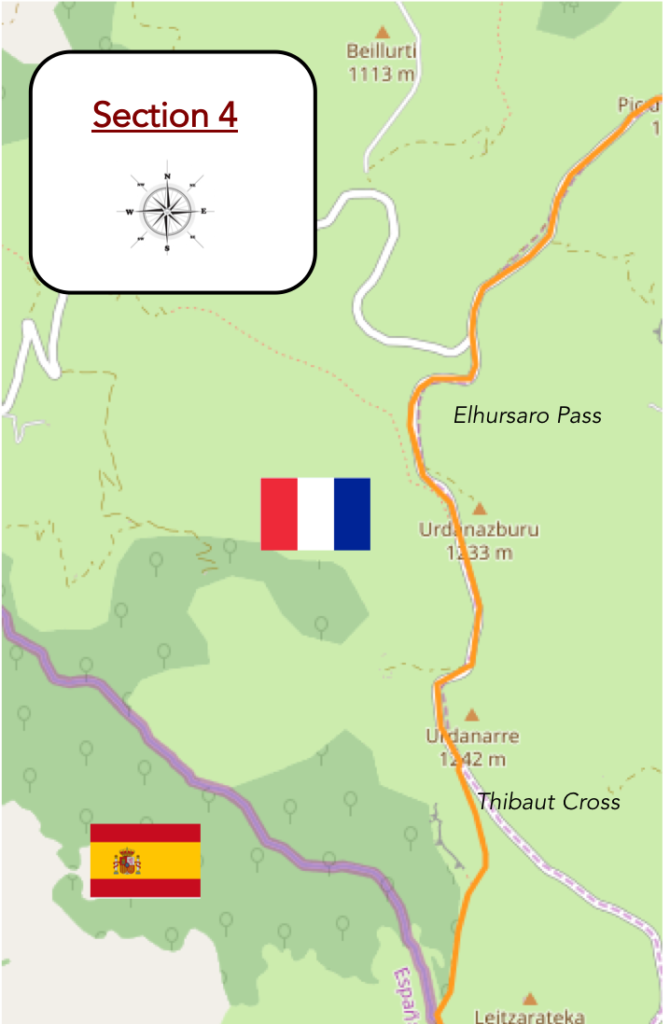

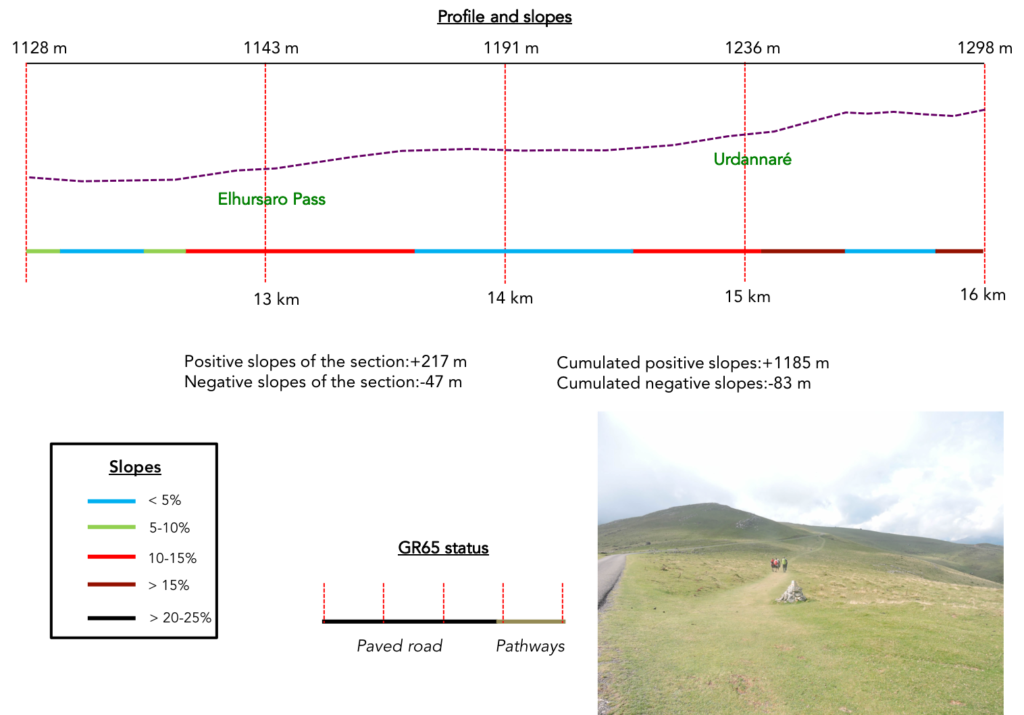

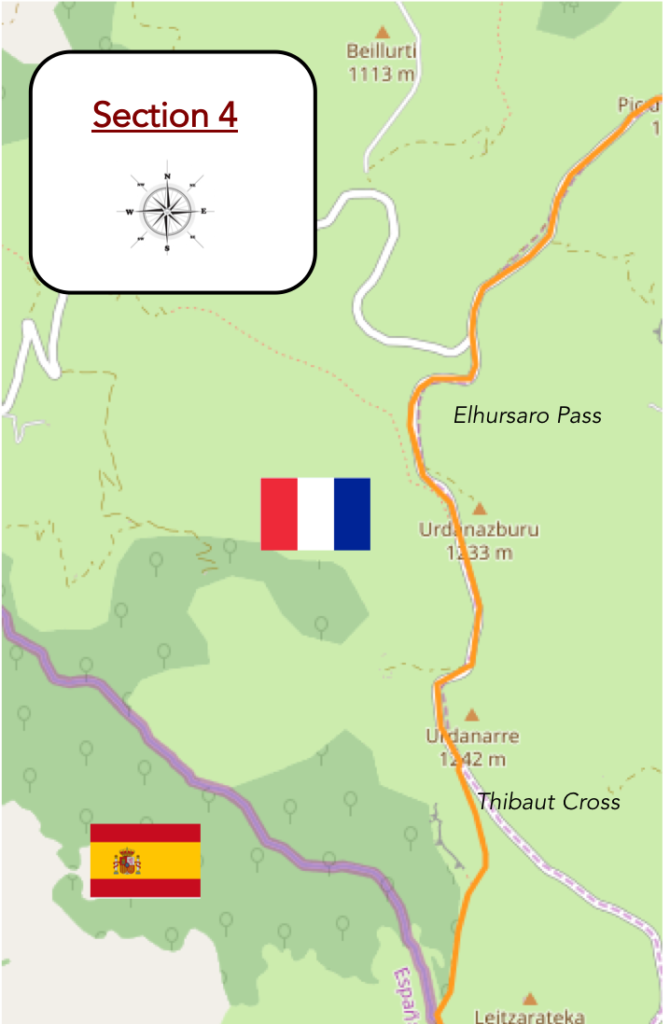

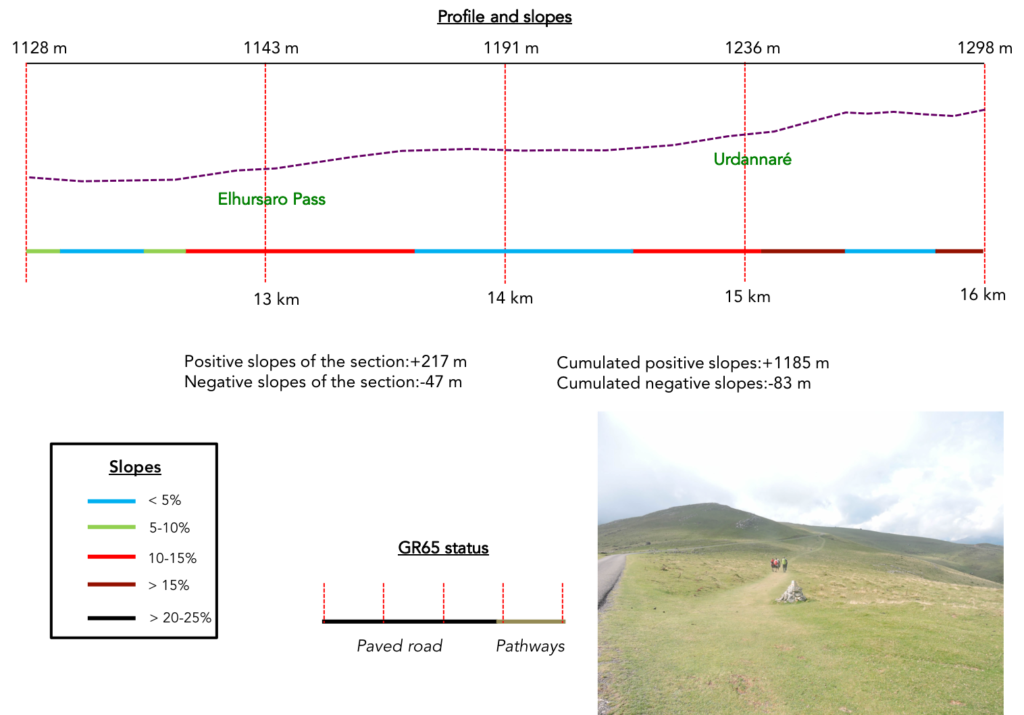

Section 4: Vultures keep watch in these huge sheep pens.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: the more you climb, the less you gain in altitude; here, on the section, it will hardly be more than 200 meters. Just nothing, right!

Bells are then heard jingling, clashing in a crystal clear, shrill sound bouncing off the hill. These are herds of horses that live here in the summer pastures. In the Pyrenees there are quite a few horse breeds. There are pottocks, the soul of the Pyrenees, horses that still live almost in the wild on the foothills of the mountain. And then, the Mérens, the black prince of the Pyrenees, also trots and climbs on the rocks, like goats. Here, they are horses of Castillon breed, another breed covered with their melodious bells. For millennia, breeders have taken their horses to the green mountains during the summer pastures.

| A small shortcut in the dry lawn, and GR path finds the road back a little up. Here, it’s the holidays, as the road flattens or even slightly climbs. Small paved roads crisscross the mountain. This will take you far to reach Spain. Instead, follow the flow of pilgrims who almost always know where they are going. |

|

|

And the flow of pilgrims reaches Elhursaro Pass, at 1135 meters above sea level. Another effort to reach Lepoeder Pass, a stone’s throw from Spain, which planted its banner 1427 meters above sea level.

| Here, the magnificent black-headed Manech are at their lunch break, painted blue, like the Indians on the warpath. |

|

|

| The red-headed Manech, with their abundant hair, are less present in the highlands. Rather, they are milking animals.. |

|

|

Then war begins, or at least a tough fight awaits the pilgrim. On the mountain that looms on the horizon, the faint tiny particles of water have finished flying away and now form a threatening cloud. We see the time coming when, depending on the pressure or the winds, they will eventually aggregate into raindrops. It’s going to explode any minute. Now there is no room for doubt.

| In front of the pilgrim then stands a small basalt rock, a sort of sentinel forward on the pasture. From a distance, we can guess like teeth on the heights. On the pasture there are now only meager shreds of flowers and foliage. Even the moles are at work, disdainful of the pilgrim who progresses in the nakedness of the steppe. |

|

|

| The road runs around the rock, in a horizon that has suddenly become darker. Only the ewes and the sheep in the distance still offer spots of light. The mountain is even more beautiful when it is threatened.

Alas, the threat is not just for the pilgrim. It is also for cattle. Because a wise eye, or better still the zoom of the camera, will quickly reveal that the teeth on the height of the jagged limestone are sometimes mobile. A pack of vultures is here for advice. The discerning eye will also recognize that they are griffon vultures, with long and broad wings, with their white head and ruff. These animals live in colonies, adore the summer pastures, then leave for a few years to sunbathe in southern Spain, before returning to procreate in the Pyrenees. |

|

|

| The presence of vultures is a bit of an irremediable herald of imminent death. They wait patiently for the moment when they can dive in to tear the still warm bowels or placentas of the newborns. These scavengers are in fact useful animals. They are the mountain garbage collectors. If only, they would also clear away the plastic bags left by the climbers, without consuming them of course. |

|

|

| Then suddenly the board ends. So, the birds spread their large wings and spin in the sky slowly, as griffon vultures do. Have they spotted a weak link in the crowd of pilgrims? |

|

|

| Are you kidding me? Not so sure. Vultures, a protected species, have become the No1 enemy of shepherds. They are so numerous that the carrion and its delicacy, the placenta of cows, become minimal. They now prey on living, injured or vulnerable animals when the herds are not being guarded. Their attitude has changed, and they no longer flee in the presence of humans. We even read in the press that a lady had been closely pursued by a horde of vultures that she disturbed near the carcass of a horse. Of course, this is not everyday reality. The vultures have better things to do, with all this stall of meat piling up around. |

|

|

| The road then arrives at Urdanarré, in the middle of the horses, in the music of their bells. |

|

|

| This is where GR path leaves the paved road, which will continue through the mountain to serve the many huts in the region, probably shepherds’ huts. You can see the cabins of Larronda in front of you, more than vulgar cabins in short. The horses who love the company come to ring their bells near the crowd of pilgrims who press near the small bus, filled with drinks and sheep’s cheese, wrapped in vacuum. You do not stop progress at the top of the Pyrenees! Today, pilgrims are reluctant to make a prolonged stop, for the flood ahead is coming. |

|

|

| Just above, GR path heads to Croix Thibaut. Here is the rest of the program. Bentarte Pass, near the border is 1.6 kilometers away, Roncesvalles 10 kilometers. |

|

|

Beyond Croix Thibaut, the slope is again very tough, sometimes more than 20% in the pasture.

Invisible reserves of indomitable energy have massed in a sky wavering between black and milky white. One drop, two drops… blah! The pilgrims, who have crossed almost all of France, sometimes in similar situations, are used to the game. Some drop their bags at lightning speed to put on their rain gear. You have to have something dry to get on at the end of the stage. Others are still hesitant.

So, suddenly the rain is there, wild. After too long hesitation, the clouds empty of this accumulated tension. A deluge tumbles in large cold, noisy drops. Here, no way to take refuge under the trees to calmly wait for a clearing. First, there are no more trees and the sky has turned uniformly black, ink and the wind howls. Through the curtains of rain, everyone frantically adorns their survival gear. Up there, a zombie has already left for Bentarte Pass.

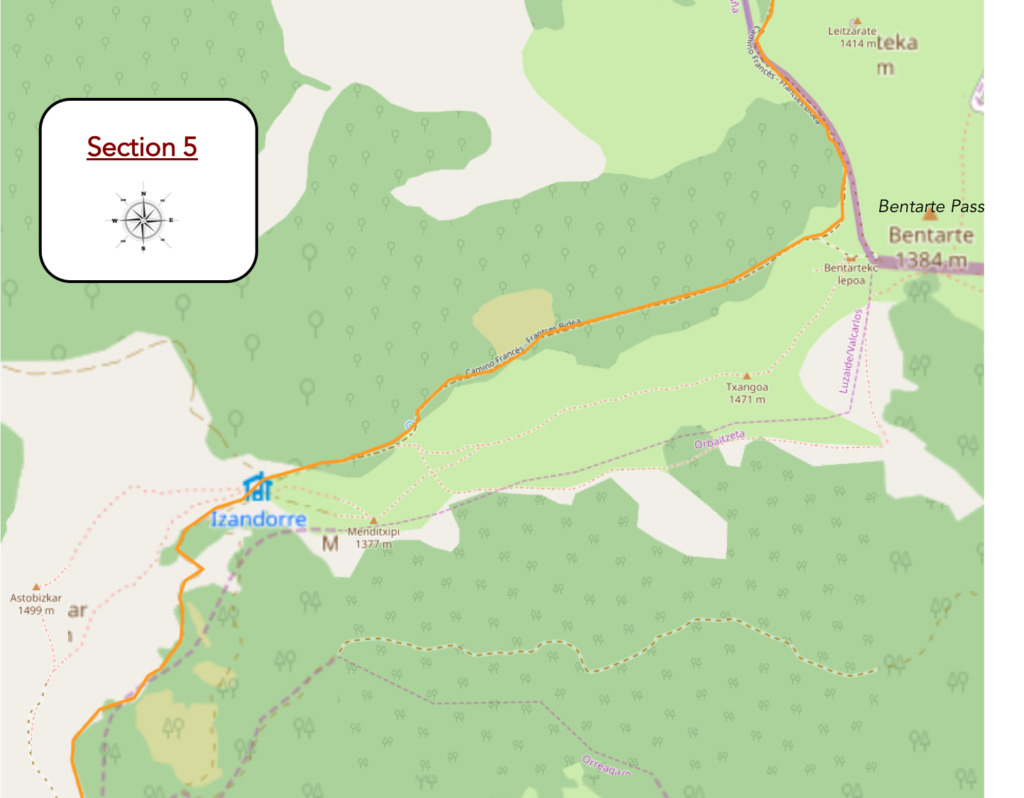

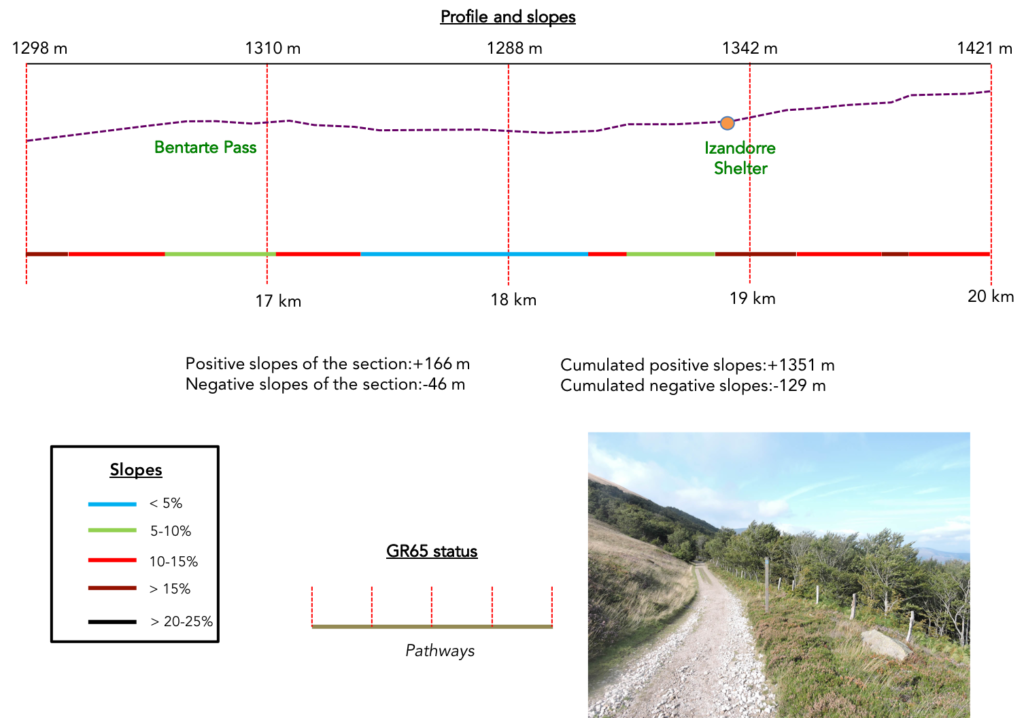

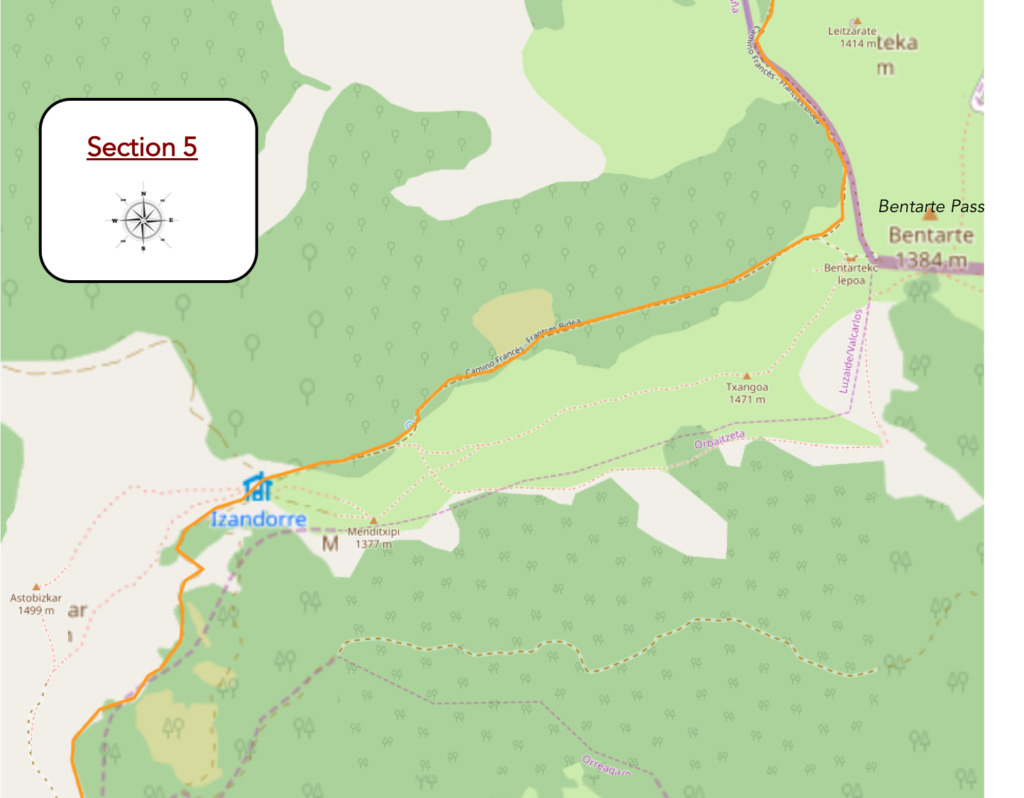

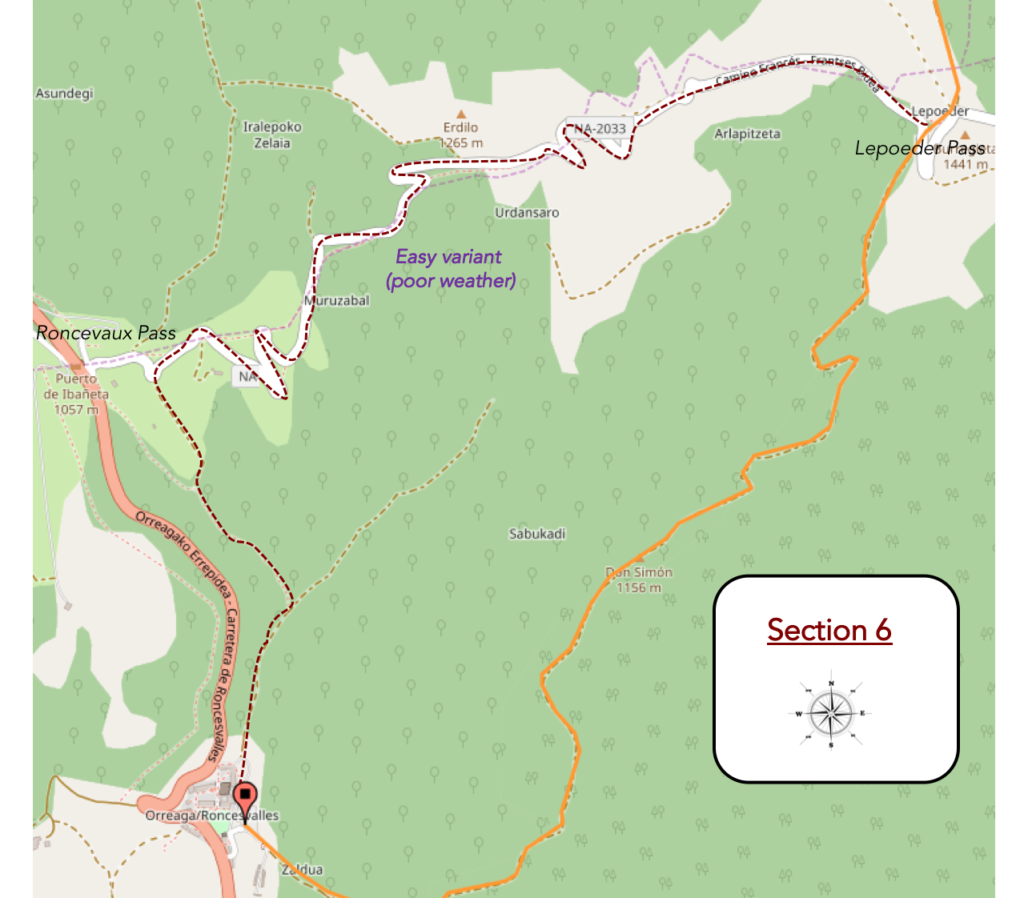

Section 5: Here, Roland would have sounded the horn.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : the higher you climb, the less you gain in altitude; here, on the stretch, it will be hardly more than 150 meters. We’re getting there, aren’t we?

| Here is this journey in the great bad weather. 5 kilometers of walking in often apocalyptic conditions. The rain beat violently on the hoods. The water trickles down the foreheads, stealthily seeping into the poorly protected joints. For the photographer, it’s just the doldrums. Unless you have a camera capable of taking underwater photos, there is only one solution: put away your equipment until the good weather returns. Thus, you will only have a few rare shots of this trip torn from the rain, between two brief clearings, when it was possible to dry a little, sheltered, a heavily fogged lens. So here are some images before reaching Leopeder Pass, at the top of the mountain, when the pilgrim enters into himself to save himself better. |

|

|

|

|

Beyond the Croix Thibaut, the pathway leaves the tarmac to climb in an incredible landscape, in good weather. And the pathway climbs in the grass towards Bentarte Pass, to come face to face with a slate plate screwed to the rock, which is called in particular the stele of Roland, or better the stele of Bentarte Pass. But why?

Here is engraved “Ibili eta amets egin”, which the Basque exegetes translate as “walk and dream”. The text begins as follows: “The weather is very gloomy this morning at the gates of Saint Jean Pied de Port and Jérôme is walking. On the climb to Huntto, the small drizzle mixes on his face with pearls of sweat. He soon disappears, caught in the fog, like a wall pass in this whitish tunnel. Apart from his stick, his shoes and a bit of asphalt, nothing can distract him. The silence outside makes his thoughts almost noisy. Moreover, no matter the sun or the rain, the silence or the noise, day or night the road is still so long which leads to Saint Jacques in Galicia. It is almost 9am on July 25 and Jérôme is still walking”.

Even a fool would understand it so far. For the rest, you must call on Champollion to unravel the poetry hidden under the words. Long live historical poetry!

| Bentarte Pass is not a real pass, and no one really knows where to locate it. Here, near the stele with the obscure message or further near the fountain of Roland? Who knows? Maybe the geographers? Still, a magnificent path climbs gently down through short heathland or through beech trees. |

|

|

| Below, the horizon drowns in the ravines of the valley. |

|

|

| The pathway runs under the peak of Leizar Athéka. A granite marker, planted in the heather, bears the number 199. These are markers that mark the border between France and Spain. My friends, you are now in Spain. No more customs here, it’s the Schengen area. Viva España! Another more explicit marker tells you that you have reached the respectable height of 1275 meters above sea level. More than 200 meters of climb! |

|

|

| The pathway then passes in front of the Fontaine de Roland, a work whose origin we do not know. It bears a simple inscription “Bidea, Iturria, Bizia”, ie “The path, the fountain, the life”. But, you also learn that there is 765 kilometers of walking left to reach Santiago. |

|

|

| Beyond the fountain, the pathway flattens between beeches and heather in a rare landscape. A stele announces Navarre. How sweet it is to be so informed, lost at the end of the world. The stele is old. In the past, did smugglers use these poles to make sure they were not in the wrong country? You think you are dreaming. |

|

|

| On the other hand, today’s pilgrim is completely disoriented, a few hundred yards away, at the array of directions to hang out. You are no longer on GR65 path and the direction signs now speak Spanish. Fortunately, the shell shows the way. It is said in the country that many pilgrims get lost every year on the way to Roncesvalles. But, it’s so beautiful here that you might sometimes be tempted to get lost in it. |

|

|

| For kilometers, a magnificent pathway will gently undulate between beeches, heather and peeled mountains. Sometimes it slopes up, sometimes down. |

|

|

| Sometimes still, it retains the aftereffects of recent rains, so frequent in the Pyrenees. |

|

|

| Here, a red-headed Manech must have got lost on the way. Nay! The animal just fell a little behind his comrades. When the path is no longer invaded by pilgrims, the animals also regain some of their rights. |

|

|

| At the bottom, it may still be France. But who knows where? Are you not in Navarre? |

|

|

| The pathway then heads to a rare grove. Here, the beeches are beginning to rule and the oaks are gradually becoming silent. Conifers are almost absent from these regions. |

|

|

| From time to time, the pathway comes out of the woods to open onto the moor, in the middle of the heather. Elsewhere, hawthorns and junipers cover the ground. Doesn’t Roncesvalles mean “valley of hawthorns” in Spanish and Orreaga “valley of junipers” in Basque? |

|

|

| When the country opens up, you can see up there, in this almost lunar landscape, the pathway that climbs to Leopeder Pass. Behind the mountain is Roncesvalles, and below in the valley, St Jean-Pied-de-Port, somewhere. |

|

|

| Then the slope narrows sharply and the pathway stops at Izandorra refuge. At these times and in good weather conditions, the cabin is empty, this changes in rainy weather. |

|

|

| Here there are even solar panels. The Spaniard met further down with his Pomeranian dog will no doubt spend the night there. |

|

|

| Beyond the refuge, this is the last slope to climb to reach Lepoeder Pass. A wide, very stony path climbs there. Here the sheep speak Spanish, but they are also Manech, with black heads, who eat the same short grass as French cousins. |

|

|

| It may seem paradoxical, but the more the pathway climbs, the more vegetation is present. But, you will understand the situation above. The French side of the mountain is peeled, the Spanish side completely wooded. So here, oaks, beeches, and even a few conifers play the stars. |

|

|

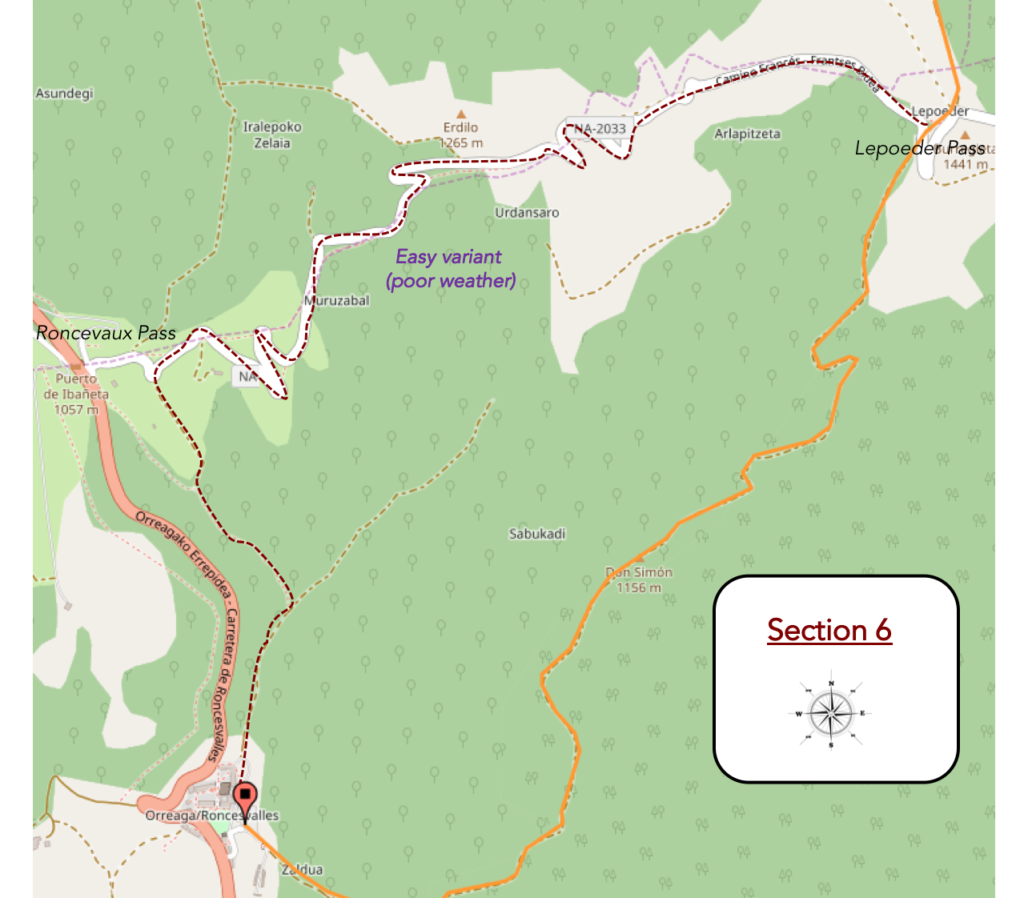

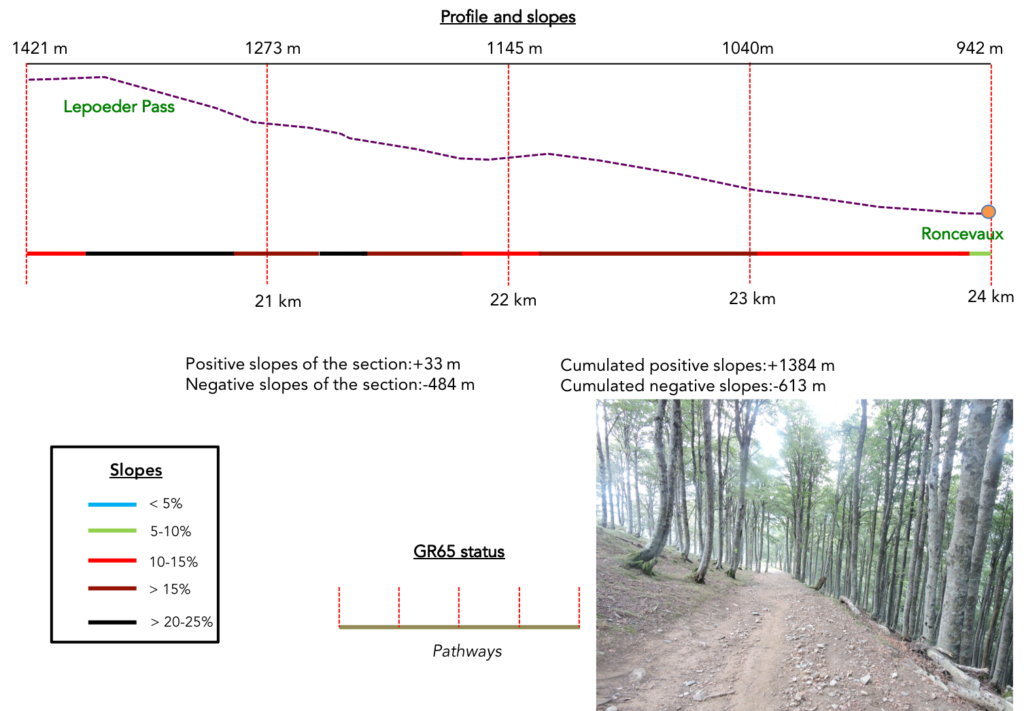

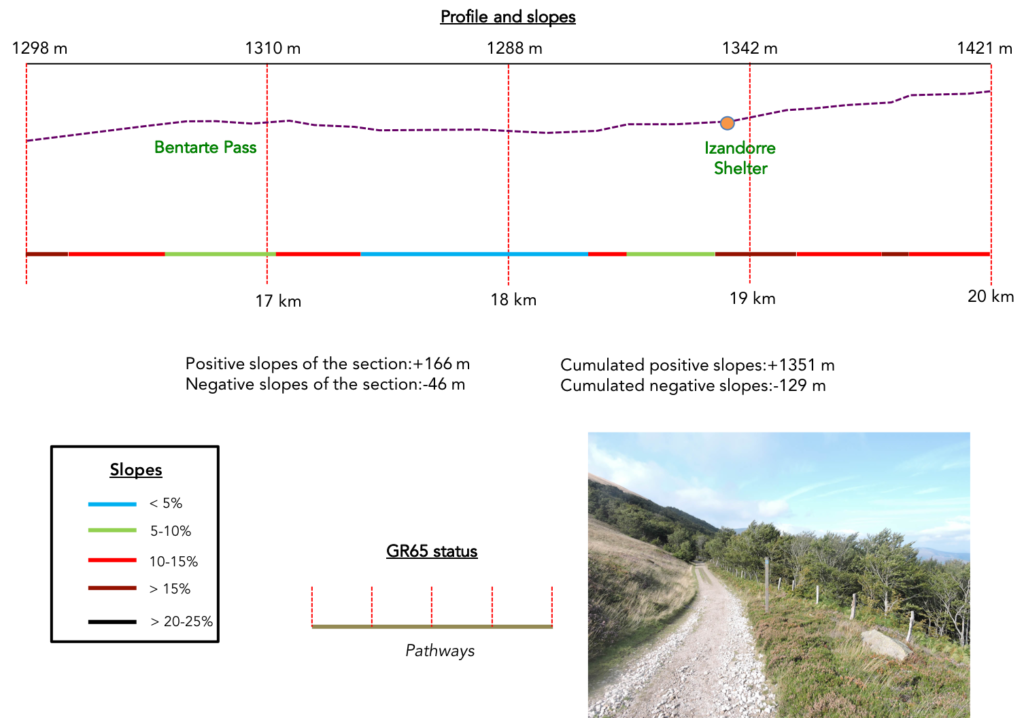

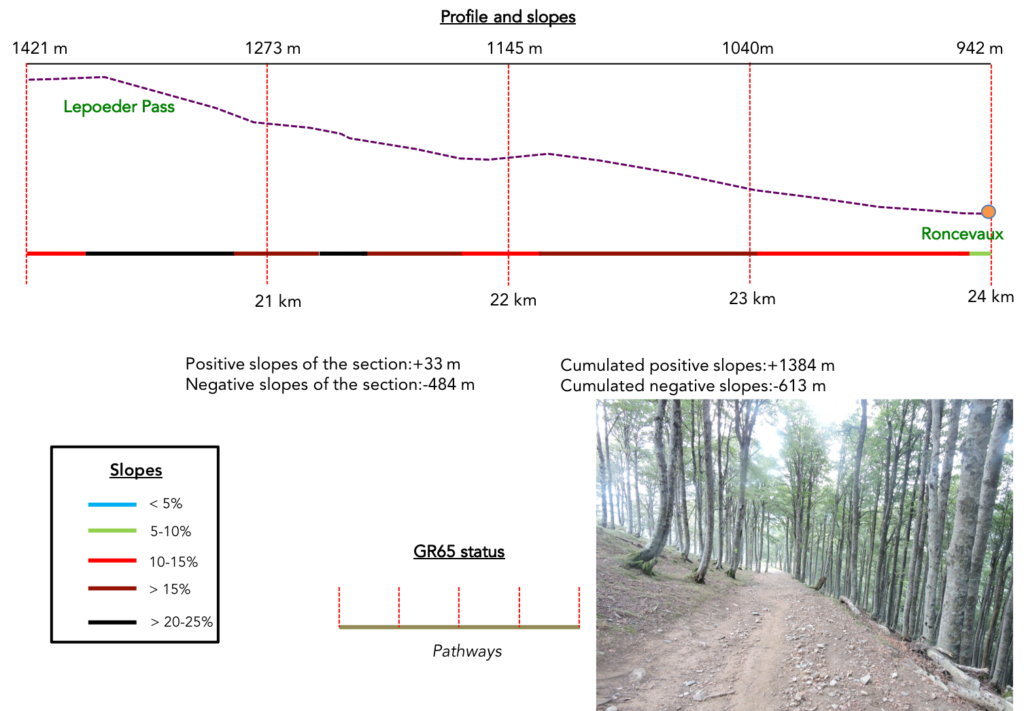

Section 6: The often-merciless descent to Spain.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: perhaps the most difficult descent of the Camino de Santiago, but it is not so sure, in good weather at least; 500 meters downhill, sometimes 30% gradient.

| The top of the mountain is very close. So, one last little ramp, just for fun. |

|

|

| You’ll arrive at Lepoeder Pass, 1426 meters above sea level. Today you have climbed almost 1300 meters. |

|

|

| At the pass, it is total luxury, with a telephone terminal and WIFI. |

|

|

| Just below, in a tangle of direction signs, it’s all about choosing the right one. There are two trackss to reach Roncevaux. And for good reason, the slope is incredibly severe. If you follow the shell, you will take the real pathway, the one indicated by “Camino de fuertes pendientes” (Steep slope path), and you will not be disappointed. The alternative is to follow “Alternativa suave al Camino de Santiago” (Gentle alternative to the Camino de Santiago). This usually follows a small road that descends to Roncesvalles, passing Ibañeta Pass, where it joins the winter variant that comes from St Jean-Pied-de-Port. It is highly recommended to use this route instead in bad weather conditions. Yet many pilgrims use the traditional track in poor conditions. Just for fun! |

|

|

| The pilgrims have been told so much about the joys and vicissitudes of this pathway, that the majority of them reject the gentle alternative of the sloping track. Very quickly, the stony pathway will enter the forest, and this until Roncesvalles. |

|

|

| The descent to Roncesvalles is already one of the most difficult on the way to Compostela in dry weather. So, imagine it under a downpour. The pathway is a marsh of red mud where the foot slips and is exhausted. The clay sticks to the soles, which weighs down the walk until it is exhausting. So, some, out of breath, curse the sky. Others remember their holidays in the sun. But all of them wipe with their hands the raindrops that accumulate on their faces and hide their walk. The wind blows in the branches of the beeches and chases waterspouts that stream from the foliage towards the track. |

|

|

| Even in good weather it is difficult. The slope becomes tough (more than 35%) on the land which hesitates between red and ocher, in the middle of beech trees planted like drum sticks. |

|

|

| Some pilgrims pray that this will last. For the others, their knees ask thank you. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the first great descent, the most vertiginous, the pathway opens onto a magnificent clearing, with its heather scattered among the limestone touches. |

|

|

| The two sides of the mountain are quite different. On the French side, these are great pastures. In Spain, the forest dominates. Sheep are likely to be fewer on this side. |

|

|

| On leaving the clearing, the pathway again approaches the forest. |

|

|

Further down, the pathway plunges again into this incredible forest, a beech grove, among the largest in Europe. No parasitic tree dares to grow here. There are no more landmarks, because the forest has replaced the sky.

| Potentially a few sheep must graze around here, at the edge of the clearings, behind the electrified wires. |

|

|

| Sometimes the ground becomes redder, and the trees, straight as columns, line up in avenues in the depths where the gaze is lost. At night, goblins and fairies must prowl around here. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway slopes up a little. The ground becomes more humid, and the generous beech trees let the ferns and weeds express themselves. |

|

|

| The climb to the small hill is short, and then the pathway will continue its descent in increasingly humid terrain, often red, and in an increasingly lush forest. |

|

|

| The pathway approaches now Roncesvalles, 5 minutes away. There is no longer any reason to get lost despite the large number of directions there are here. Viva España! |

|

|

Charlemagne, the very Christian king, on his return from an expedition against the Muslim Saracens who had seized power in Spain, suffered from the perfidy of the Basques. Having imprudently divided his army in the passage of the Pyrenees, he was attacked by the Basques, who completely defeated his rearguard engaged in the valley of Roncesvalles. The Basques killed, after a fierce battle, all the men of the rear guard down to the last, including Roland, commander of the marches in Brittany. So much for the story, or at least what we think we know. But, if Roland is historically of little importance, his figure in the Chanson de Roland, a chanson de geste of which we do not know the author, has taken on a chivalrous, heroic proportion. The emperor with the flowery beard commands the front of the army; the rear guard is under the orders of his nephew Roland, the Duke of Brittany, assisted by his friend Olivier. Unfortunately, they are betrayed by Count Ganelon, which allows the Saracens to ambush the Frankish troops at the Roncesvalles Pass. The Saracens (in fact the Basques) let the king and the main body of the army pass, but they rushed towards the rear. The twelve francs fight like hell. Roland puts on the show with Durandal, his legendary sword. But, they fall one after the other. On the wise advice of Olivier, Roland blows with all his might his horn, which resounds for seven leagues, to call Charlemagne for help. In vain. Faced with the desperate situation, he resolves to break his sword, so that it does not fall into the hands of the enemy. But the sword is too strong, and it shatters the rocks on which Roland tries to smash it. This is the Roland Breach, a gigantic fault, over 50 meters high, that can still be seen in the Pyrenees! Seeing that the sword would not break, he would have thrown it with all his might as far as Rocamadour in the Lot. Come on! Charlemagne of course has heard Roland’s horn. He turns around, but when he arrives, it is too late, All the valiant men have died under the blows of the Infidels.

No one knows exactly where exactly these historical events took place. The Camino de Santiago does not run through Roncesvalles Pass, also known as Ibañeta Pass. If you take the winter track, you will walk through this pass. This one is on the road which goes from St Jean-Pied-de-Port to Roncesvalles. But the legend has passed that way. Since then, monuments have been erected all over the country in memory of the valiant knights.

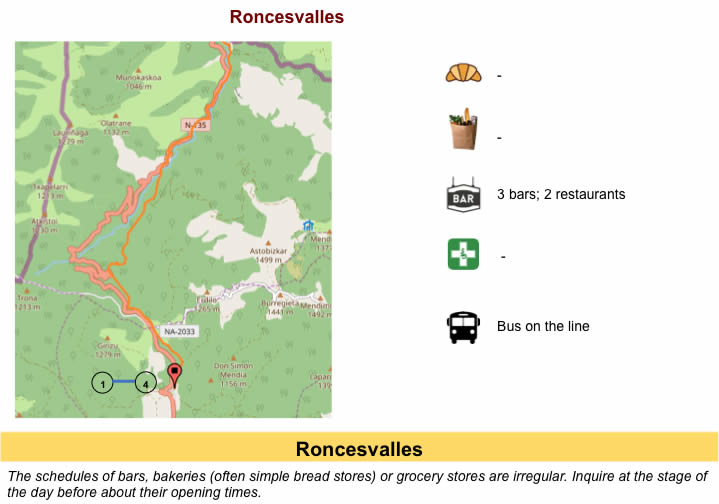

Roncevaux (Orreaga in Basque, Roncesvalles in Spanish) is as big as a pocket square, but the buildings are gigantic. In Roncesvalles, the Roland stele faces the magnificent Hotel Roncesvalles and the entrance to the Collegiate Church. This discreet monument commemorates the battle, where the split stone symbolizes the breach, next to bronze bas-reliefs telling the legend.

| There is little doubt that Ibañeta Pass has always been an easy passage through the Pyrenees, given its low altitude (1057 meters). There is also little doubt that there was a chapel there, and later a hospital. At the beginning of the XIIth century, everything was transferred to Roncesvalles, in a more welcoming place. This is the date of birth of the collegiate church, which was entrusted to canons of the order of St Augustine. The church was transformed and in the XIIIth century, the collegiate church of Roncesvalles, since Gothic, had become a must-see site for pilgrims. Towards the end of the XVth century, tens of thousands of meals were distributed here per year. Then came the decline, the revolutions, the wars. Roncesvalles was promised to ruin. In 1844, there was even talk of selling the abbey. It took the revival in popularity of the pilgrimage at the end of the last century and the ardor of the people of Navarre to make this place a new myth. This is where the Camino Francés leaves for Santiago. |

|

|

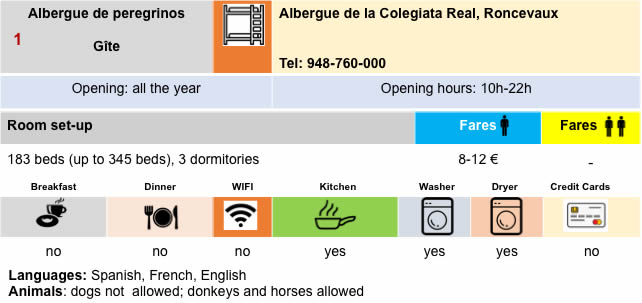

It was in 1982 that the monastery, now secularized, was reopened to welcome pilgrims. It is a gigantic gîte, which can accommodate up to 300 pilgrims.

Adjacent to the Collegiate Church is the small church of St Jacques, also known as the Pilgrims’ Church, a small rectangular building of gray stone. The bell is said to have come from the old chapel at Ibañeta Pass.

The St Esprit chapel, next door, also known as Silo de Charlemagne, is said to be the oldest building here, dating from the XIIth century. This Romanesque chapel had a funeral vocation. It is said that Charlemagne would have buried here the 12 peers who died in combat, including Roland. Over the centuries, it has rather served as a mass grave or as a burial place for pilgrims who died on the Way.

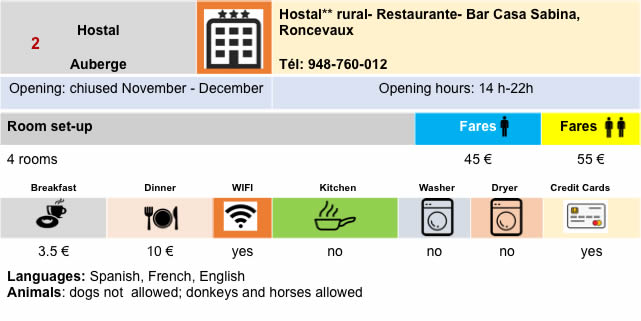

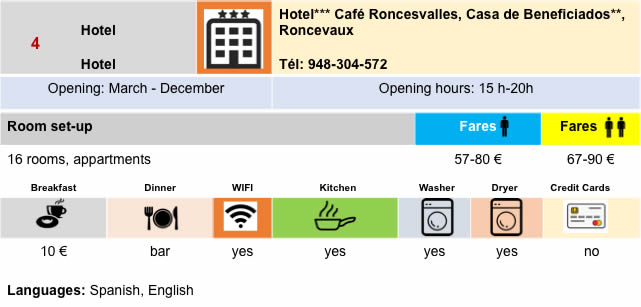

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 1b: From St Jean-Pied-de-Port to Roncevaux by the alternative |

|

|

Back to menu |