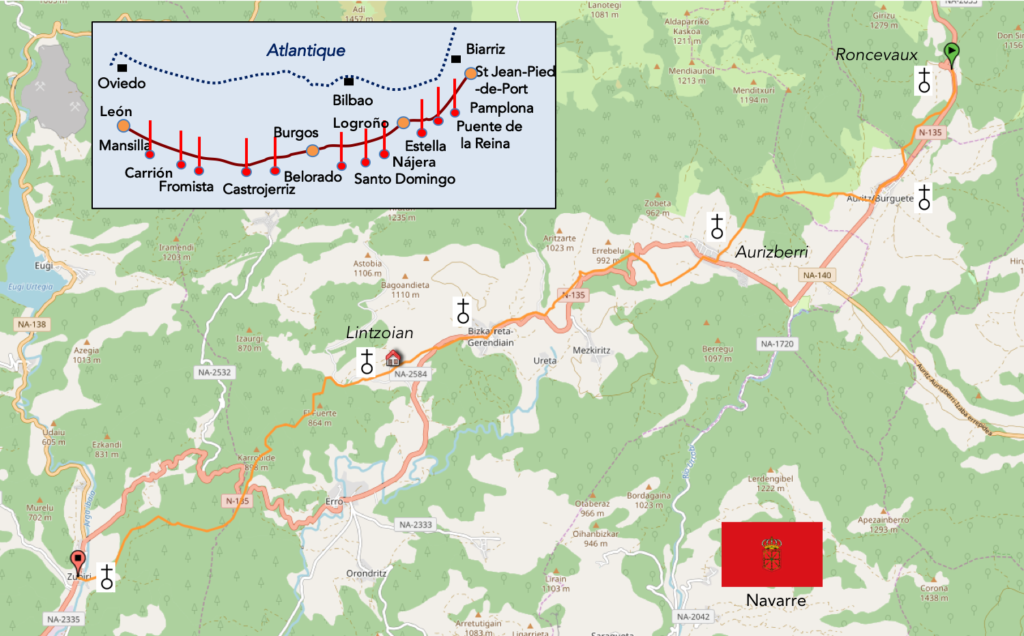

In the beautiful beech and pine forests of Navarre

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

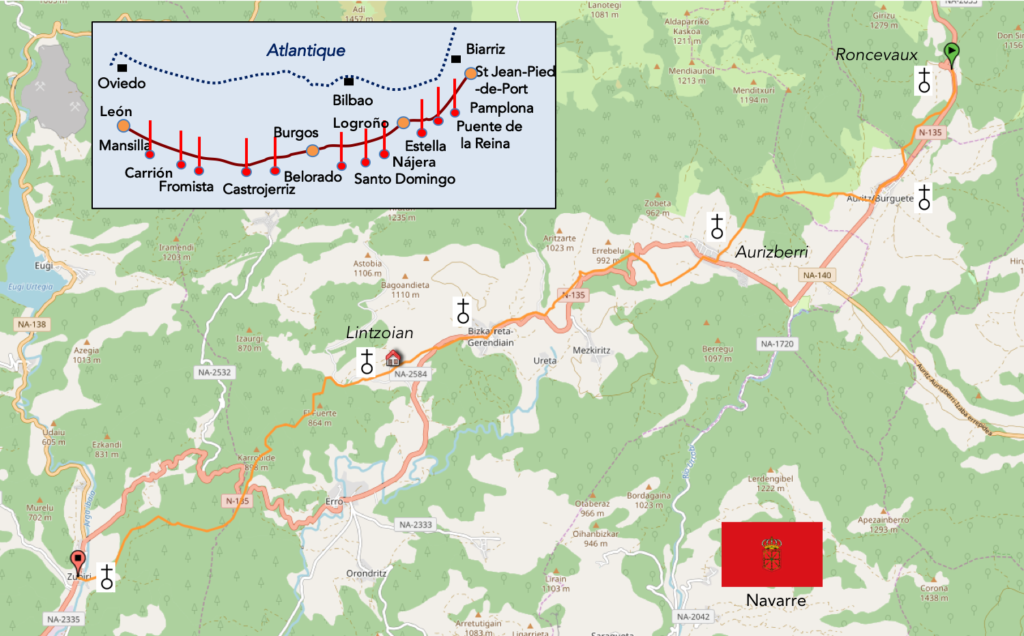

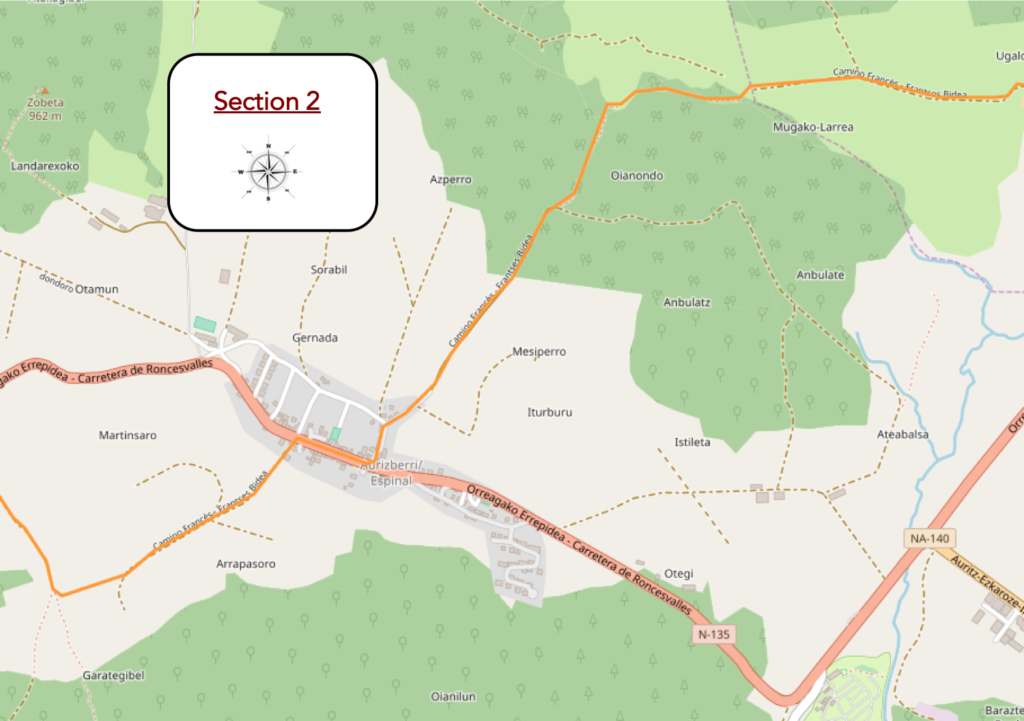

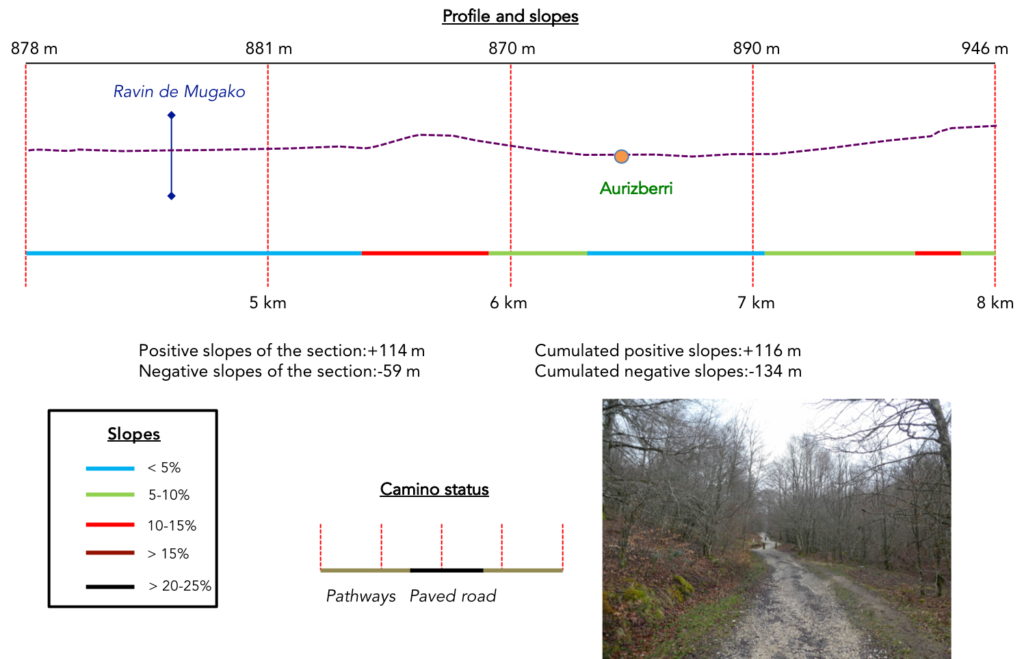

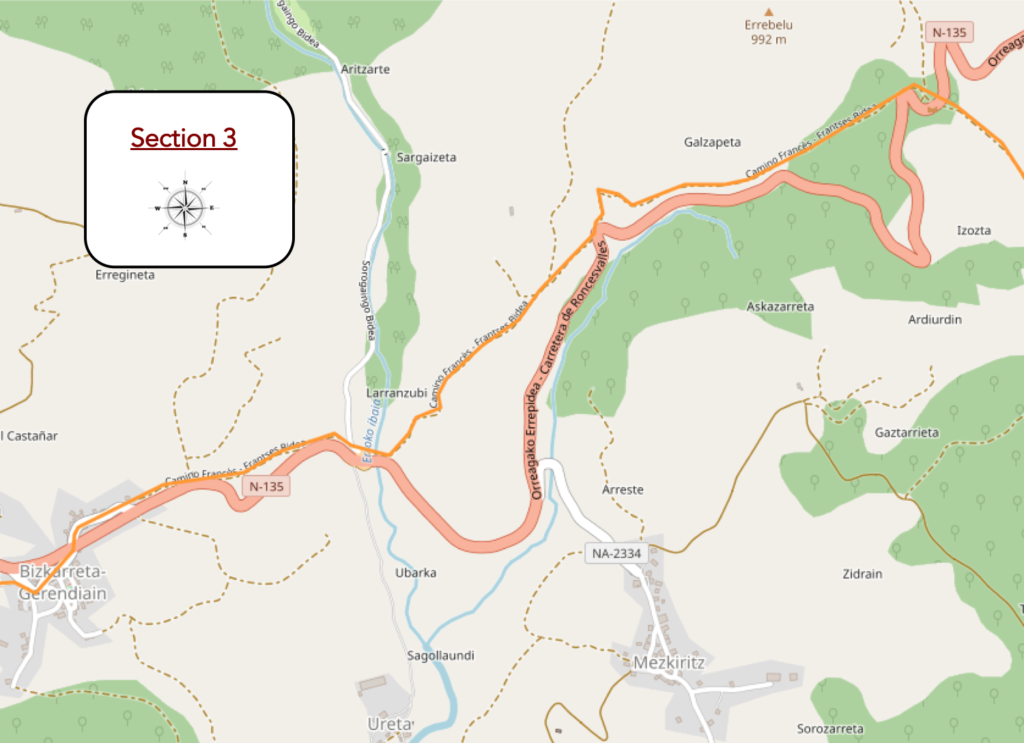

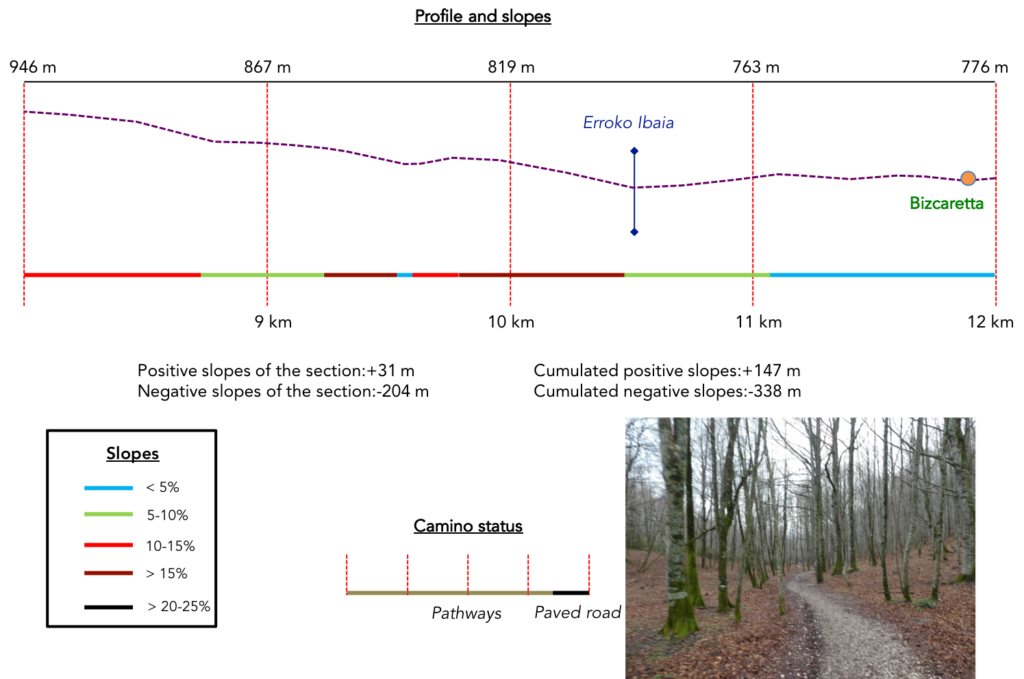

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-ronceveaux-a-zubiri-par-le-camino-frances-37582828

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

The Santiago Registry Office provides statistics on attendance and distribution of pilgrims on the way every year. Here are the 2018 data recorded according to the months of the year:

| Month |

Number of pilgrims |

Month |

Number of pilgrims |

| January |

1’628 |

July |

50.668 |

| February |

2’181 |

August |

60.415 |

| March |

11.056 |

September |

47’006 |

| April |

22.068 |

October |

35’602 |

| May |

40’665 |

November |

7’651 |

| June |

45’665 |

December |

2’553 |

| Total number : 327.378 |

Obviously, these are statistics, based on questionnaires filled by pilgrims, to which they are asked for the track used, the place of departure, the nationality. These figures are those of pilgrims who come to the office, with their “credencial” to receive their diploma. The figures do not include pilgrims who do not go to the office. And there are many for example not to have a“credencial”. But, most pilgrims who go to Spain, play the game, in principle.

As these figures say, the peak of participation is in summer. Poor pilgrims who must undergo the heat of the Meseta! At the time we are describing the way, we are at the end of April-beginning of May, with a participation estimated at 35’000 pilgrims per month, so about 1’200 pilgrims a day arriving in Santiago. Now, of course, all the pilgrims do not start at St Jean Pied-de-Port or Roncesvalles. But, we also know the starting statistics by locality. In 2018, 10.1% of pilgrims left St-Jean-Pied-de-Port and 1.69% of Roncesvalles. In total, you find 11.79% of pilgrims who could have left Roncesvalles, that is 1’200 x 11.8%, or 140 people per day. But, we can assure you that there are more than 140 people at Roncesvalles.

Now let’s play another game using nationalities, considering the Santiago register. In 2018, Americans accounted for 5.68% of pilgrims, Koreans 1.8%. Playing a bit with these numbers, and assuming that 2019 might look a bit like 2018, we should meet today with 11 Americans and 3 Koreans a day on the way. However, this is not the case, they are much more numerous, representing more than a quarter of the pilgrims on the stages of the first week. When you send the night to the lodgings and see the same heads every day, you have another idea of statistics. Because obviously the statistics give only the figures on arrival in Santiago, and not the departure by nationality at each entrance of the track.

So, here is another register, to complicate matters. This is the registration office of St Jean-Pied-de-Port.

| Month |

Number of pilgrims |

Month |

Number of pilgrims |

| January |

292 |

July |

6.173 |

| February |

320 |

August |

8.320 |

| March |

2.077 |

September |

10.189 |

| April |

7.499 |

October |

4.135 |

| May |

10.837 |

November |

602 |

| June |

7.148 |

December |

289 |

| Total number : 58.884 |

And you understand right away how difficult it is to compare data from partial statistics. If 58’000 pilgrims (French statistics) leave St Jean-Pied-de-Port, and 327’378 arrive in Santiago (Spanish statistics), this would mean that 18% of pilgrims have left St Jean-Pied-de-Port. However, the Spanish claim that only 10% of pilgrims left St Jan-Pied-de-Port, that is two times less. Who is right? The problem is in the analysis of the questionnaires,

Now, let’s try to understand why in the first stages of the journey in Spain, there are so many Koreans and Americans, which the Spanish analysis does not show, which concludes that there are 3 Koreans and 10 Americans a day. So, as St Jean-Pied de-Port is still quite far from Santiago, it is better to rely on French data in this area, for the beginning of the route. According to their data, the peak is in May, with 10,837 pilgrims, so that 10’837/ 30, namely 360 pilgrims going daily to Roncesvalles. This also shows the difficulty of lodging in Roncesvalles, because the major lodging accepts only 189 people. But, there are other possibilities of housing here, or else you have to go further on the way. The French also give the origin of the pilgrims, with 10.8% of Americans and 7.5% of Koreans. We should then meet 40 Americans and 27 Koreans on the way, which fits pretty well with what you may observe on the way.

Considering French data, out of the 58,884 departures from St Jean-Pied-de-Port, 6350 Americans and 4413 Koreans leave each year. According to the Spain, 18,850 Americans and 5,665 Koreans arrive in Santiago. This means that the majority of Koreans start the Camino at St Jean-Pied-de-Port, which is only true for a third of Americans. You have to realize that for an American, an Australian or a Korean, coming here is just an expedition. These pilgrims do not come here just for a couple of days. They are here for the very long term. This is why you find many representatives of these countries at St-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Roncevaux. In contrast, Spanish pilgrims, who represent the 50% of pilgrims on the way, can enjoy a holiday to walk a few steps, from one year to another. We know that today fewer European pilgrims leave their country to walk straight off to Santiago or Finisterra.

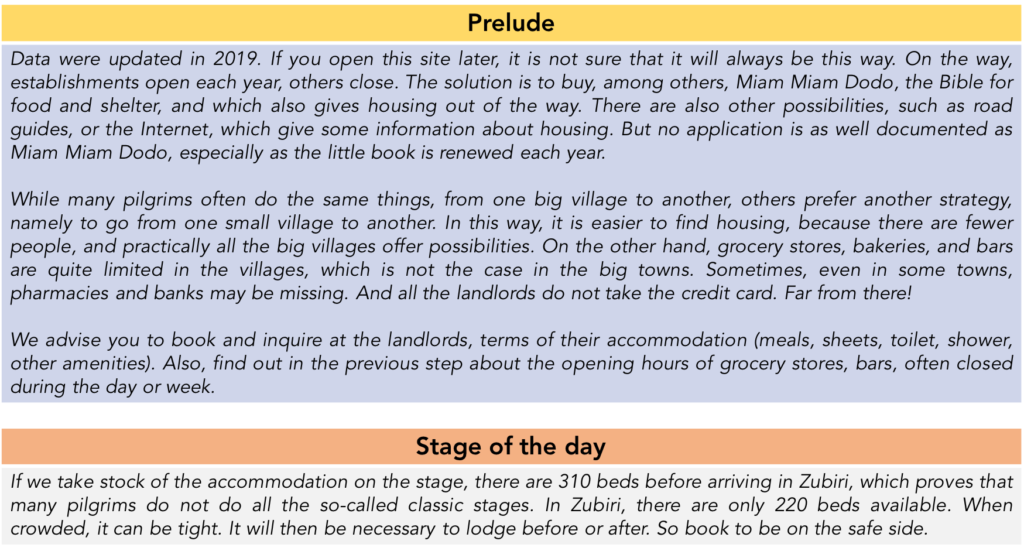

Anyway, the stage of the day is a beautiful walk in the forests of Navarre, in the middle of the beech trees first, then in the pines. The forests around Roncesvalles are known to be the largest beech forests in Europe. The villages are charming with stone houses, strongly decorated and emblazoned, made to withstand the harsh climate that characterizes these regions. This land was Hemingway’s favourite land.

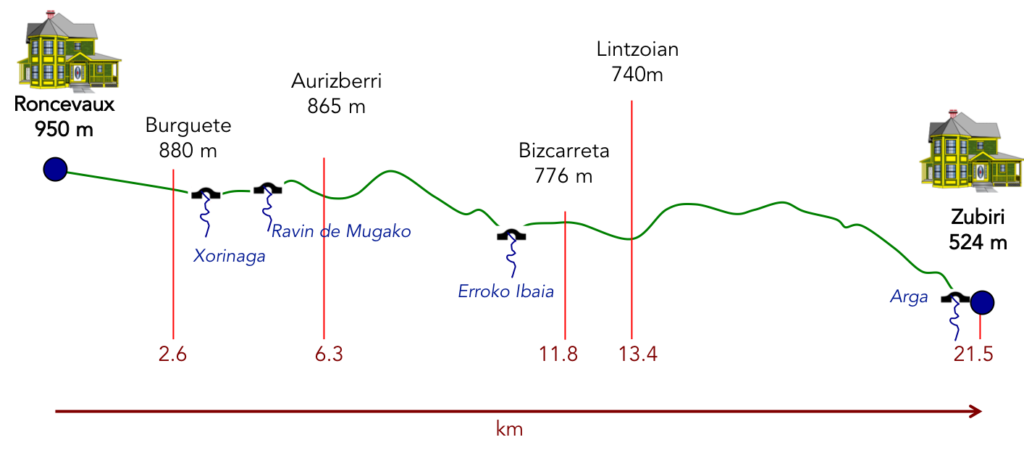

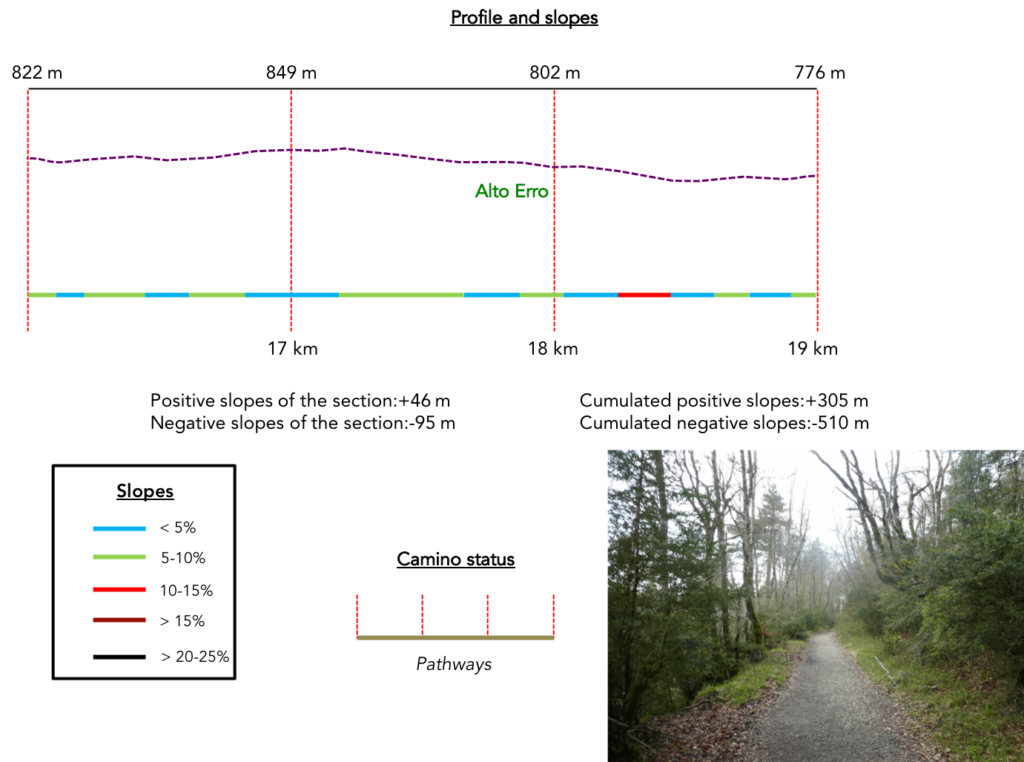

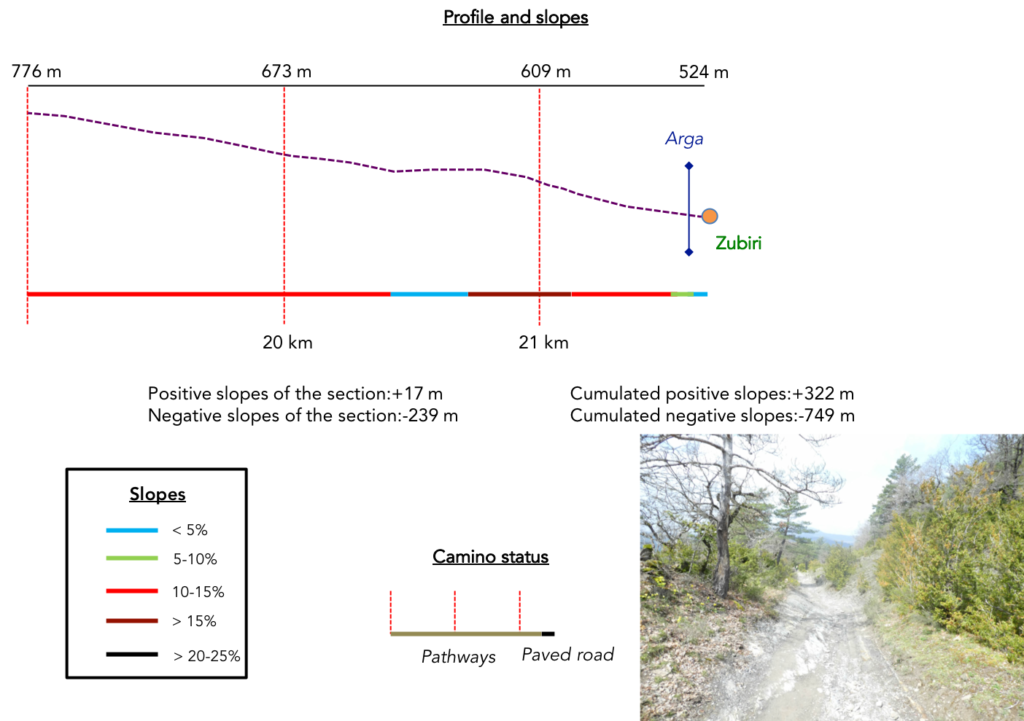

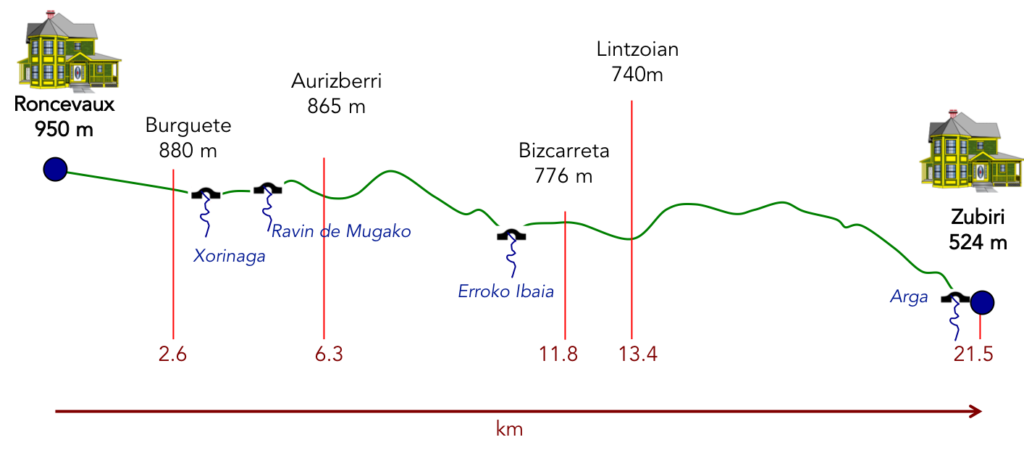

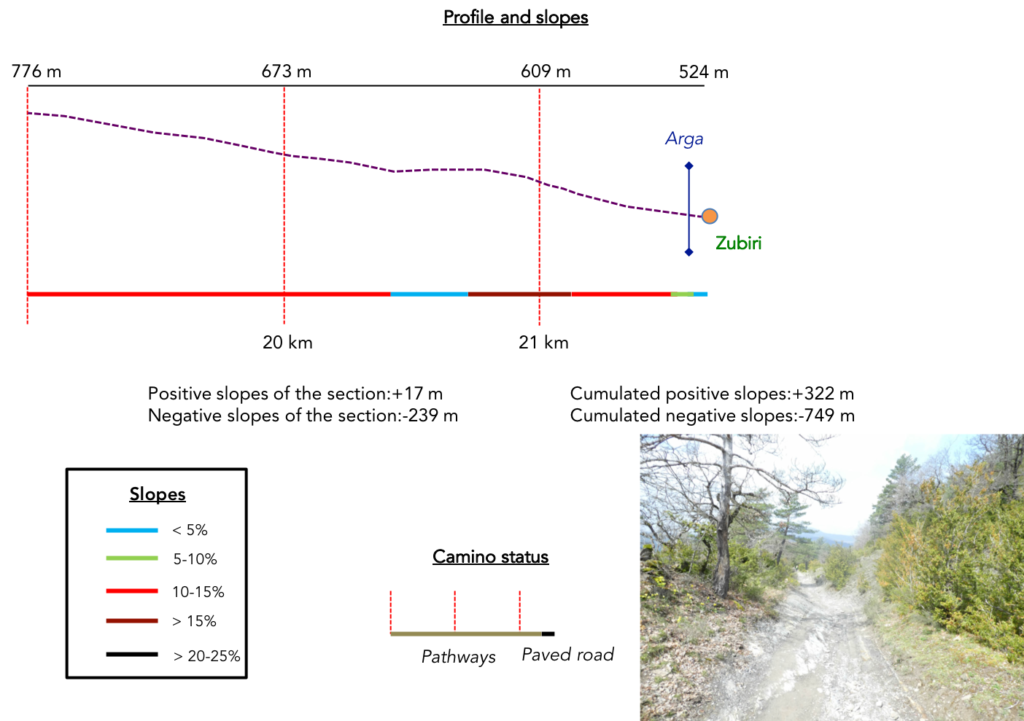

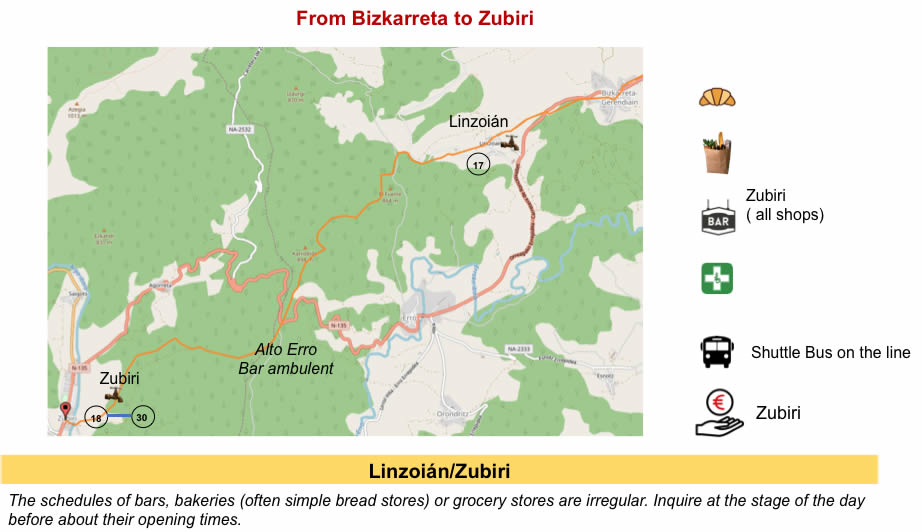

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations today are pretty high (+322 m /-749 m). It’s downhill foremost. For uphill climbing conditions, there are only three real bumps, a short before Autrizberri, a longer beyond the same village, then a serious after Lintzioian. But it’s little more than 300 meters of positive sloping in all. The descents are often on slabs, or in the painful descent on Zubiri on brittle stones.

In this stage, the route is almost exclusively on the pathways. Some pathways are paved. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true dirt road, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 2.7 km

- Dirt roads: 18.8 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

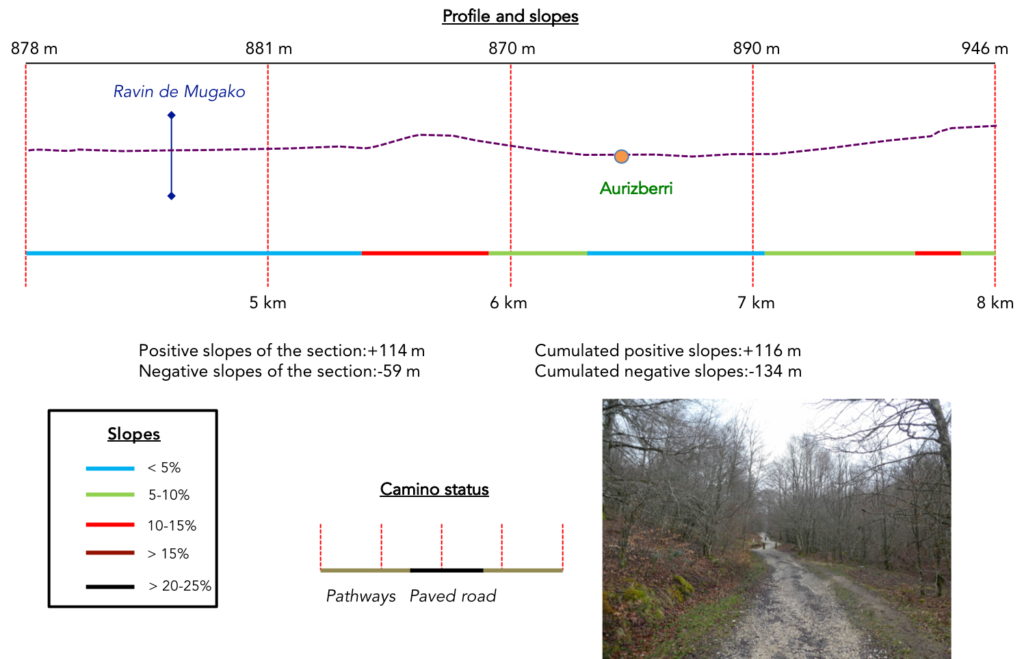

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

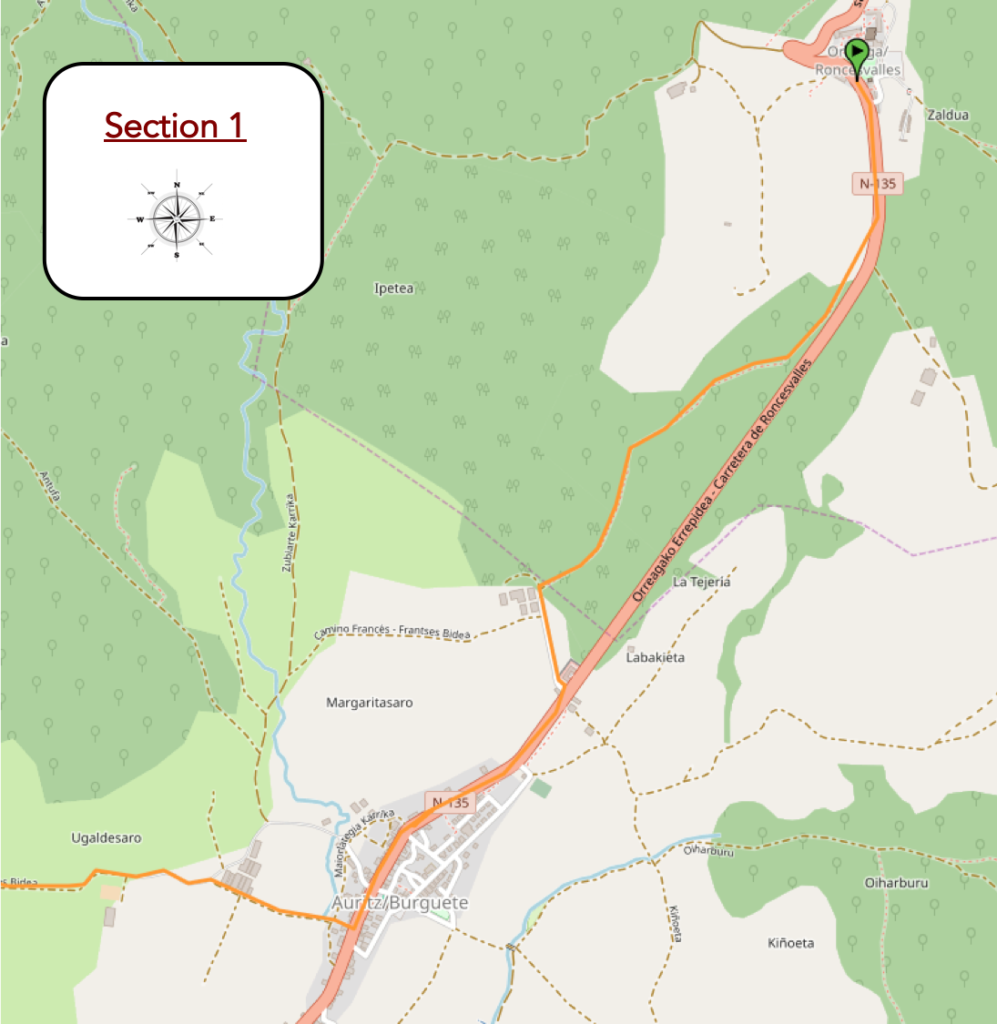

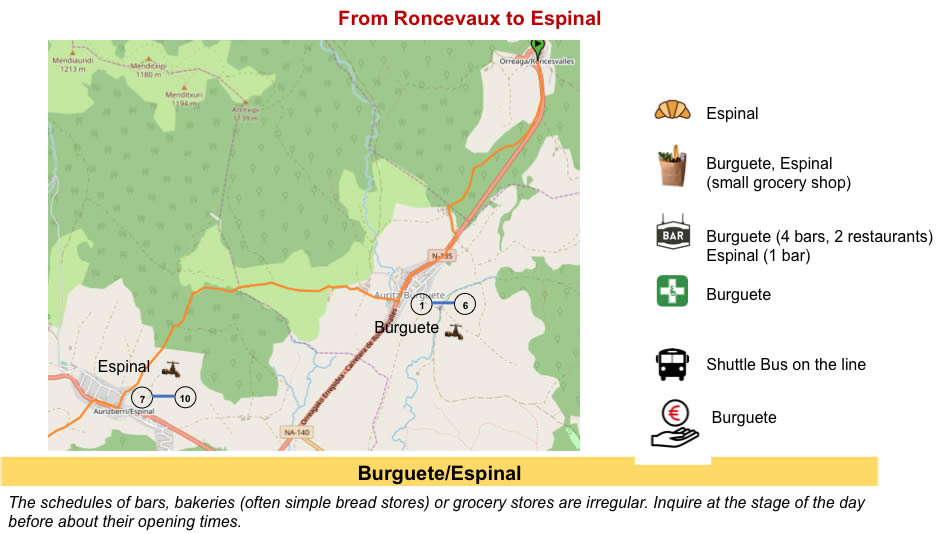

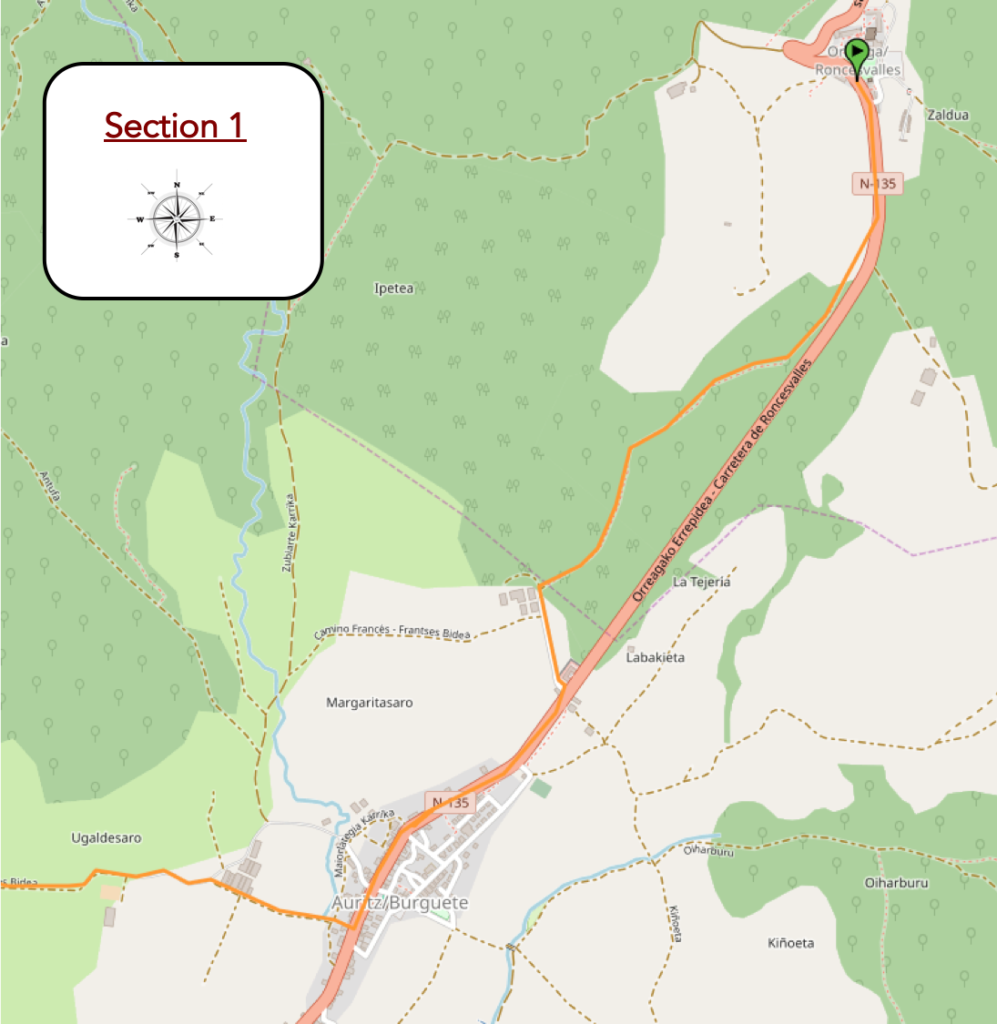

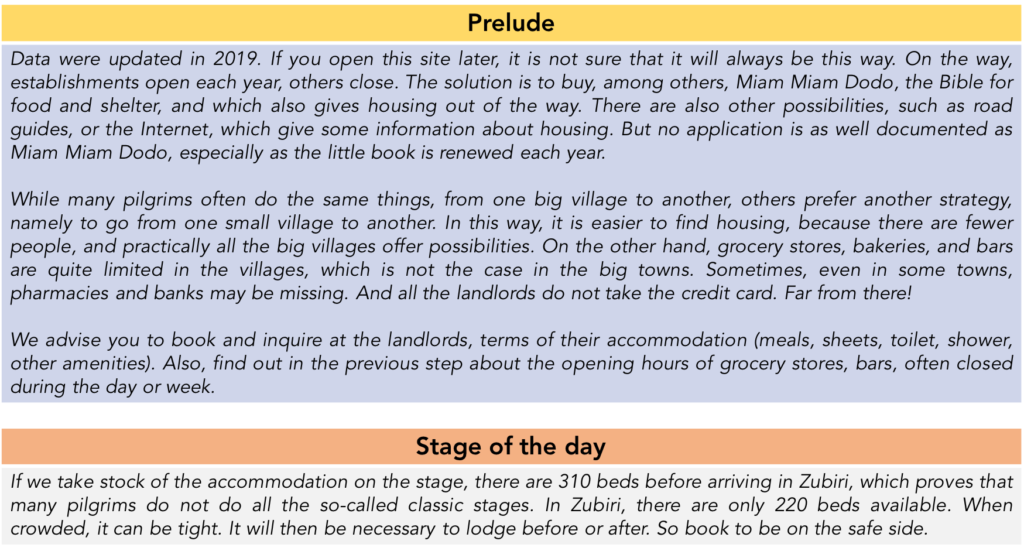

Section 1 : Through the beeches to the beautiful village of Burguete.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Today, the rain stopped on the Pyrenees. But, the sky is still dangerously cloudy, in a temperature that borders on 10 degrees. In Roncesvalles, you don’t see many people at the start. The Koreans are already on their way. They leave early. |

|

|

| Here, the program is announced. Santiago is next door, 790 kilometers away. A dirt road descends gently under the beeches, along the national N-135 road. |

|

|

Along the way, you’ll find the “Pilgrim’s Cross”, a very austere XIVth century Gothic Calvary, under the trees.

| Sometimes, moss colonizes the stone walls, along the beech trees of all sizes, erected like sticks. In this early spring, the trees have not yet really put their leaves. |

|

|

| Here, you encounter tall majestic beech trees. The track crosses here one of the largest beech groves in Europe, and these trees will be found for a long time to come in the first stages in Spain. |

|

|

| Further down, towards the exit of the wood, the pathway twists a little on the black ground. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino comes out of the forest, in the outskirts of Burguete. |

|

|

| The Camino then joins the national road near a supermarket, where pilgrims go to do their shopping. There is no grocery store in Roncesvalles. |

|

|

| Then, along a small park, the road quickly arrives near the first houses of the village. |

|

|

| Burguete, nicknamed “little Switzerland” is a remarkable village with its emblazoned stone houses, along a single street. When crowds are high, pilgrims who have not found a place in Roncesvalles stay here. |

|

|

| It is a village where the stone is rich and solid, in strong contrast to what you will see in the poor villages of the Meseta, later on the route. It is a village classified as a “Good of Cultural Interest”. Hemingway, who loved bullfighting, liked to stay here to indulge in fishing in this area which he described as “the most detestably wild territory of the Pyrenees”. |

|

|

| The Church of San Nicolás is of medieval origin, but destroyed many times by fires. Its current appearance dates from the end of the last century. Here, an expiatory procession was organized in the past, in memory of the death of Roland, in the valley near Roncesvalles, because the Navarrese had killed the hero. The people covered with a hood, carried heavy crosses on their backs to appease the plaintive soul of the hero whose horn was sometimes heard ringing in the mountains. The horn has probably ceased to sound, because for a century, the custom has disappeared. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, the Camino crosses the Xorinaga stream and runs into the countryside. |

|

|

|

|

| Here, it smacks of the real countryside. Cow breeds are very complex in Spain. Local breeds, there are many in the north of the country, especially in Cantabria, Asturias or Galicia, most often meat breeds. But, what does local mean for a breed? In the XVIth century, the Habsburg Empire included Germany, Austria and Spain, and crossbreeding also took place for cattle. Then there was the growing influence of the races of the French Southwest, including the whites of Aquitaine and the limousines. So most of the cows here are part of what the breeders call the “blond and red branch”. For example, the pilgrim will be very clever if he dares to say that the cows here look more like blondes from Aquitaine than blondes from Carinth, in Austria. And then, it also needed milk, not just meat. So. farmers cheerfully crossed these local cows with Holsteins or Simmentals.

The bull here, perhaps a savage specimen of the Betizu breed, does not watch with a complacent eye the hikers pass in front of his domain. In any case, a revealing panel does not encourage pilgrims to go and see it too closely. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway runs, first on the tarmac, then on the dirt, in the middle of the countryside along the alleys of beech trees. Pilgrims often leave at almost the same time. From then on, you rarely walk alone and the queues get longer on the tracks. |

|

|

| The impermeable ground here has kept the memory of past rains. |

|

|

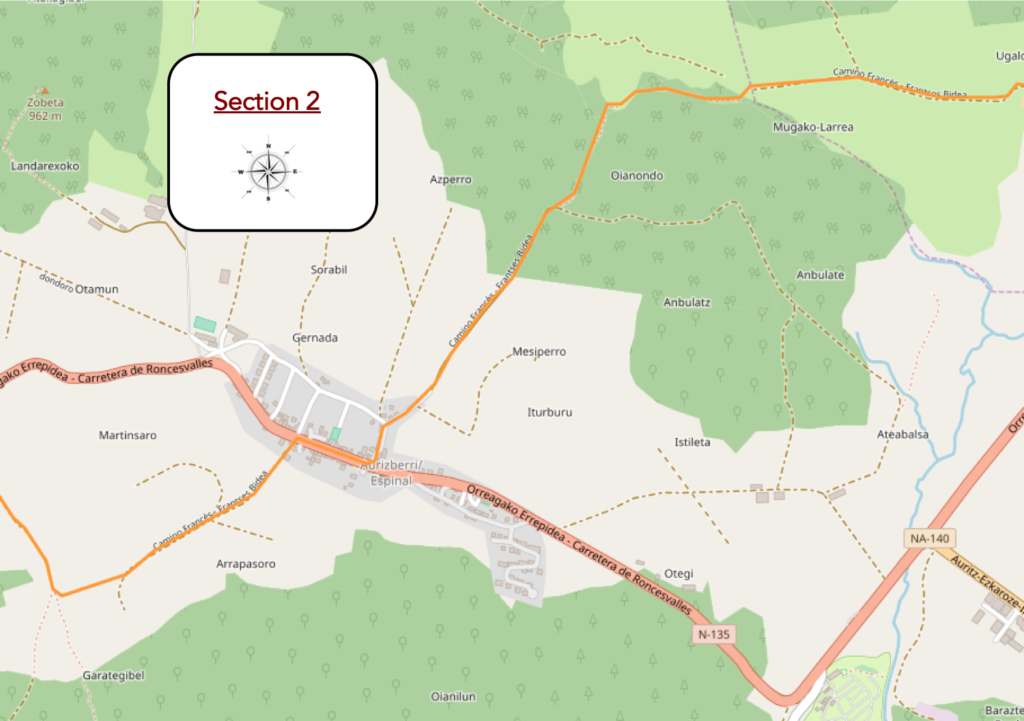

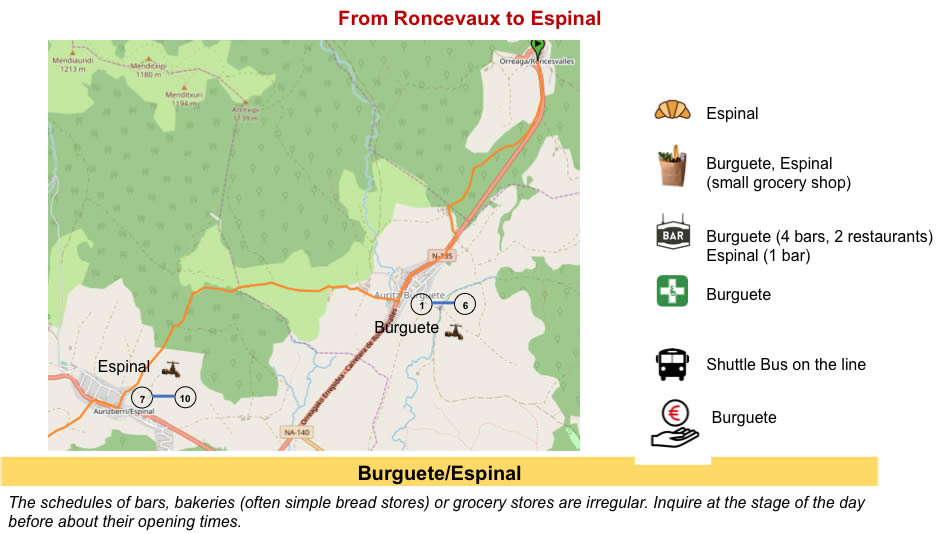

Section 2 : Some ripples in the woods.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some steeper slopes.

| The pathway then gets in a more humid area, furrowed with small streams that squirm in all directions. Pilgrims are not allowed to wade in the water of the streams in Spain. Everywhere, small works are erected to keep the feet of the walker dry. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the dirt road runs between meadow and undergrowth, under the stunted beeches and the charred fern hedges of the past season. And the pathway begins to climb up the hill. |

|

|

| Here, this region is called the Mugako ravine. Of ravine, it has only the name. It is rather a marshy ground. |

|

|

| Then comes the first effort of the day in the form of a very stony pathway that climbs for quite a long time to the top of a hill. In these conditions, this is also what you observe when the big trucks start to climb a steep climb, the line of pilgrims forms, because they do not all travel at the same speed on a slope between 10% and 15 %. |

|

|

| And some are already taking a break. At the top of a forest where the beeches, generous, sometimes allow a few oaks to grow (it is often the opposite), tar replaces the stony ground on the descent of the hill. |

|

|

| The road then slopes down on the other side of the hill, near a small trickle of water. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent the road approaches the village of Espinal. Here is the plain. But, if you have looked at your roadbook, you know that it will not last forever. |

|

|

| Espinal is a pretty village as is Burguete. These two villages date back to the Middle Ages with the birth of the Camino, when pilgrims had to be assisted. Towards the end of the XVIIIth century, the French passed through here and burned down all the villages. This one, like the previous one, was rebuilt in the XIXth century, on a consistent plan, stone houses along a large main street. It must be said that the street is still narrow for a national road. |

|

|

| In the village, even the bakery is in a vintage house, without storefronts. |

|

|

| In Spain, the directions are very well indicated, even in the agglomerations where sometimes it is possible to get lost. On leaving the village, the road heads back into nature. As expected, the path will slope up. It’s enough to look at the queue of pilgrims, bent under their heavy bag. |

|

|

| In the surrounding meadows graze small horses equipped with bells, quite similar to those encountered in the mountain pastures of Roncesvalles in summer or autumn. These horses are Burguete of Navarre who also live in semi-freedom. And when there are cattle in the Pyrenees, there are also often vultures. The latter fly in an organized band above the herd. Is there a sick horse around here? |

|

|

| The tarmacked road climbs steadily here, at almost 10%. |

|

|

| Further up, the road gradually gets closer to the forest where spruces are emerging. The tar then gives way to a narrow lane. |

|

|

| The stony pathway climbs more steadily to the top of the hill, often mired, along spruce trees, then back into beech trees. Here, the track wanders at an altitude of 950 meters. |

|

|

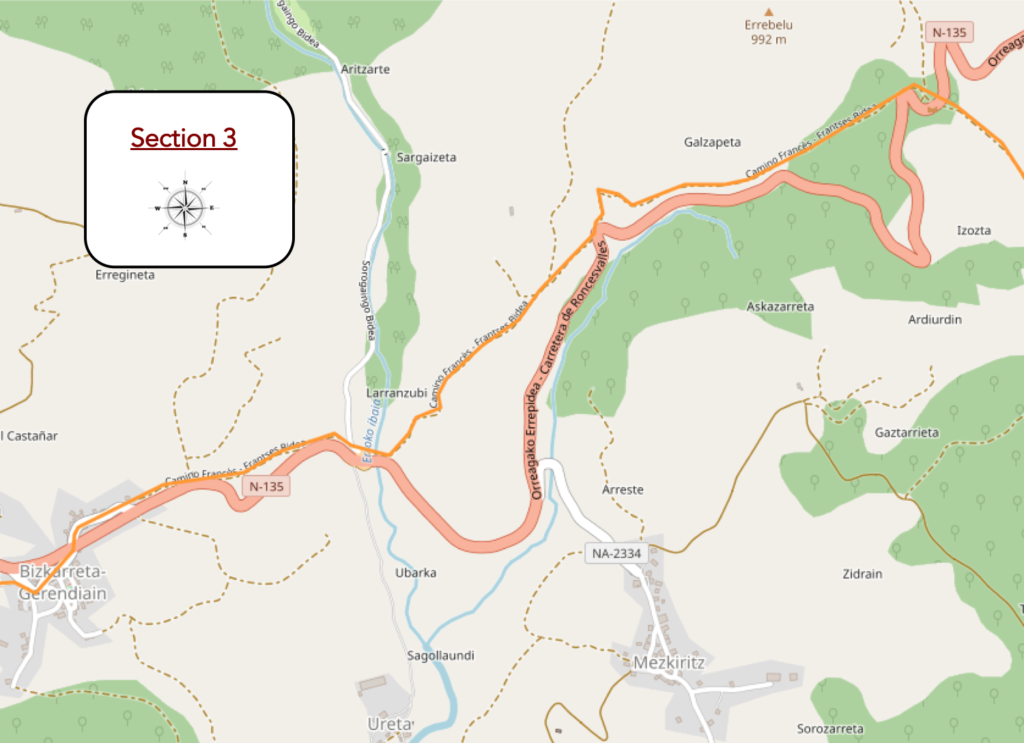

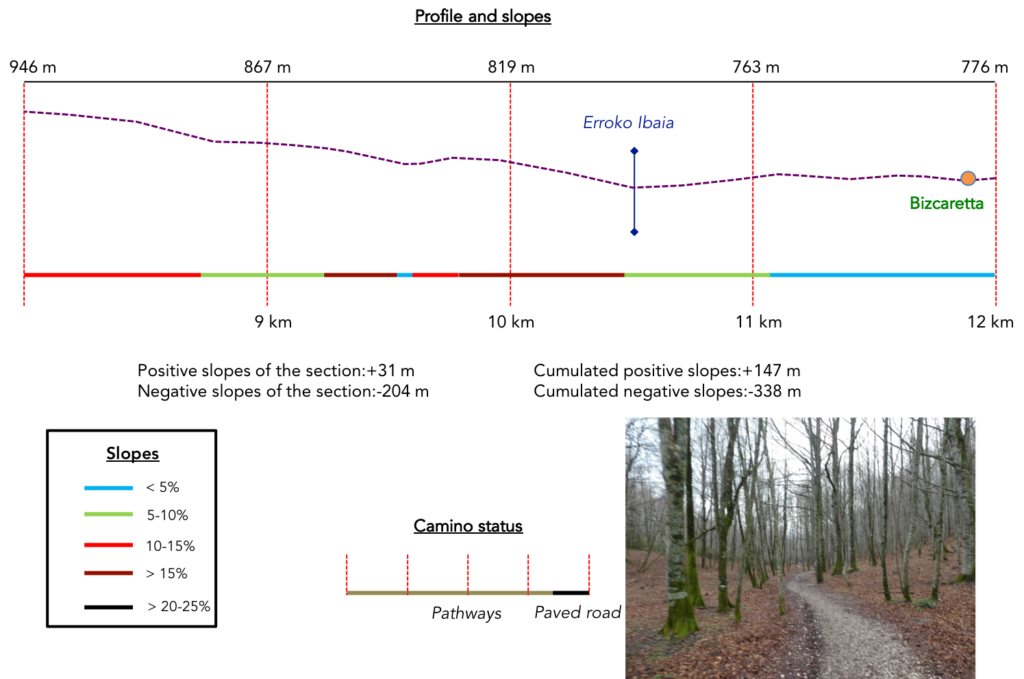

Section 3 : On the axis of N-135 road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: breaking-legs course downhill.

| At the top of the hill, the pathway turns at a right angle and gently descends the side of the hill along the hedgerows. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it quickly gets at a place called Mezkiritz, near a picnic area. |

|

|

| There, the route crosses the N-135 road, the Pass road that comes out of Espinal. |

|

|

Here you are 13 kilometers to Zubiri.

| The pathway then crosses an incredible forest of sumptuous beeches, which nature or men have planted there, like notes on a score, as long as the masts of sailless ships, sometimes creaking from one side to the other under the effect of gusts of wind whistling on the treetops. Then the wind dies down and then the forest is almost silent. You’re finally ready to listen to the silence, but there’s the cavalry charge behind you. Two Americans charging forward, bellowing their tongues as if they needed to be heard on the other side of the ocean. These people, at least many Americans, behave like conquistadors. They are in another relationship to time and space. What a pity! |

|

|

You let the American army pass, giving them a sound “Buen Camino”, so as not to offend them. Then, you may hear the slight screeching of bicycle wheels behind you, discreet as not allowed, even braking behind you. They are cyclists who make the way. These athletes now make up nearly 5% of pilgrims, according to Spanish statistics.

| Further down, the beeches take up less and less space and the forest dissipates among the bushes, beech shoots, broom and wild grass that appear on the slopes. |

|

|

| Then, the slope becomes severe, more than 15%. So, Europe, which decreed the Camino Francés as an important track, invested millions to improve it. Here, slabs have replaced pebbles and mud. Soon the track may be a highway, if they continue like this. But, the Korean lady walking here will come down with a bit more ease. Nevertheless, at the rate she is advancing, she had to leave at dawn this morning. Korean equipment manufacturers must not know what the Camino de Santiago is. For them, the shell of Shell Company is the same as the Compostela shell. |

|

|

| On the slabs, the pathway then gets a little closer to the Pass road. |

|

|

| Further afield, it sinks again into the chlorophyll and the moss of the undergrowth, on the saving slabs. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope is even steeper in the damp undergrowth, where ivy colonizes the beeches, where the hedges are covered with brambles and holly. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway finds the Erroko Ibaia brook. On the way, the Koreans are very discreet, the complete opposite of the Americans. Some are often very young. They know that the passport is to always pronounce the same refrain. So, they give “Buen camino”, each time you meet them. Because their English is quite basic, a bit like that of the French people you meet on the way. |

|

|

| We will always be amazed by the ways the Spaniards use to simplify the difficulties of the track. |

|

|

| Beyond the river, the pathway climbs gently on the slabs towards the Pass road. Here, one of two things. Either the ground is often soggy to justify their use, or money was enough to pave the way to the village. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village of Bizkaretta/Gerendiain, the bar is taken over by pilgrims. Local craftsmanship is given less consideration. Will we ever come back here to buy a scrap pilgrim to put in our garden next to the garden gnomes? |

|

|

| The village is a stone’s throw from the bar. |

|

|

| Here, the Camino passes on the other side of the Pass road and crosses the village. |

|

|

| Again, one of those beautiful villages of Navarre, with solid houses, with their colored moldings, of which you can read on the pediments that some date back to the end of the XIXth century. We know that the village was a stopover for pilgrims in the Middle Ages, mentioned that it is in the Pilgrim’s Guide. The houses are even more opulent than in the French Basque Country, when it was once the same country. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino finds the small slabs, fords a trickle of water and heads to the meadows. |

|

|

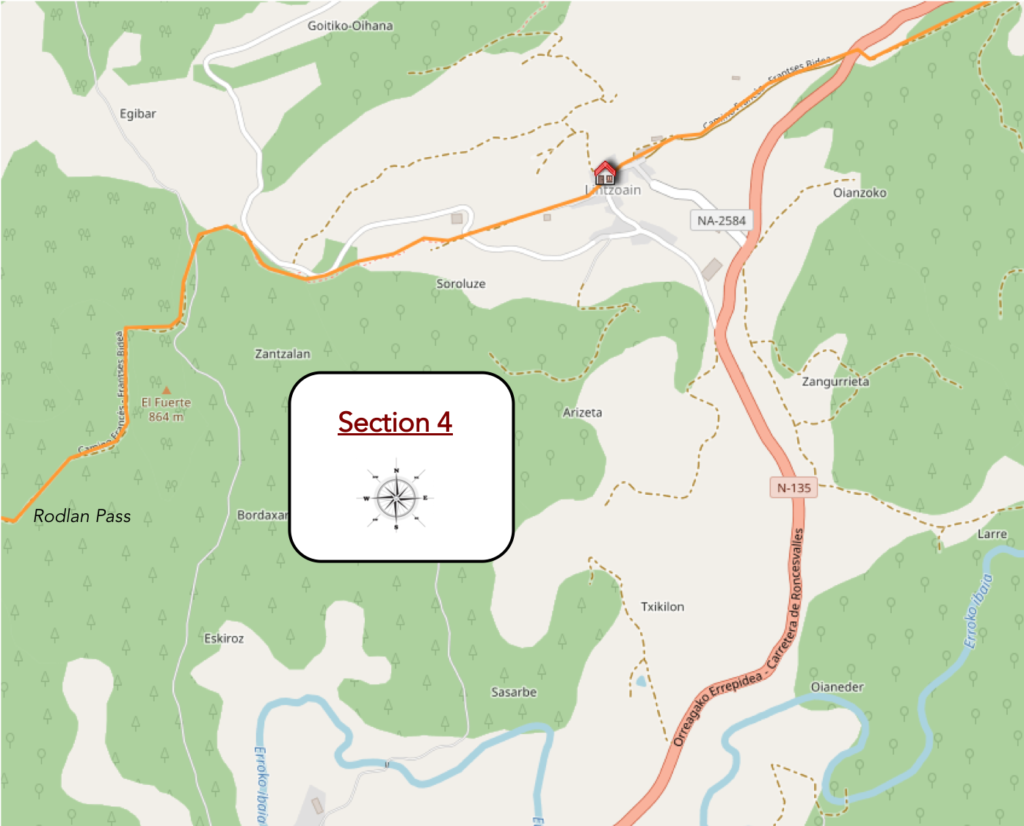

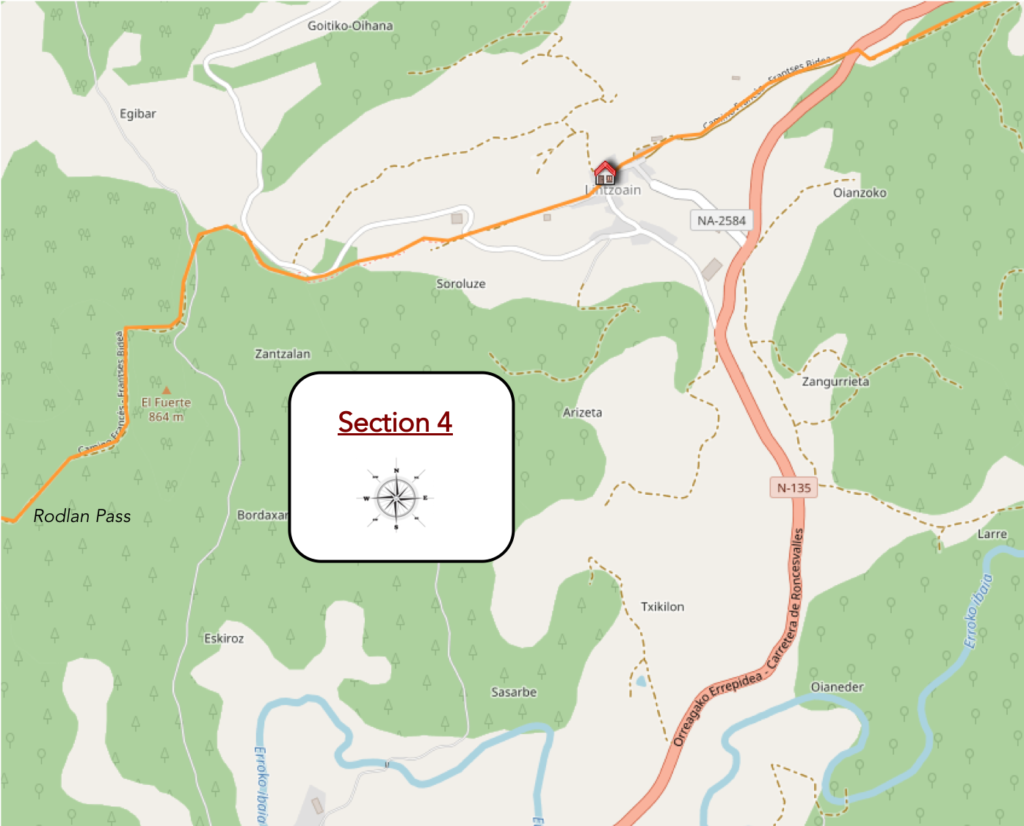

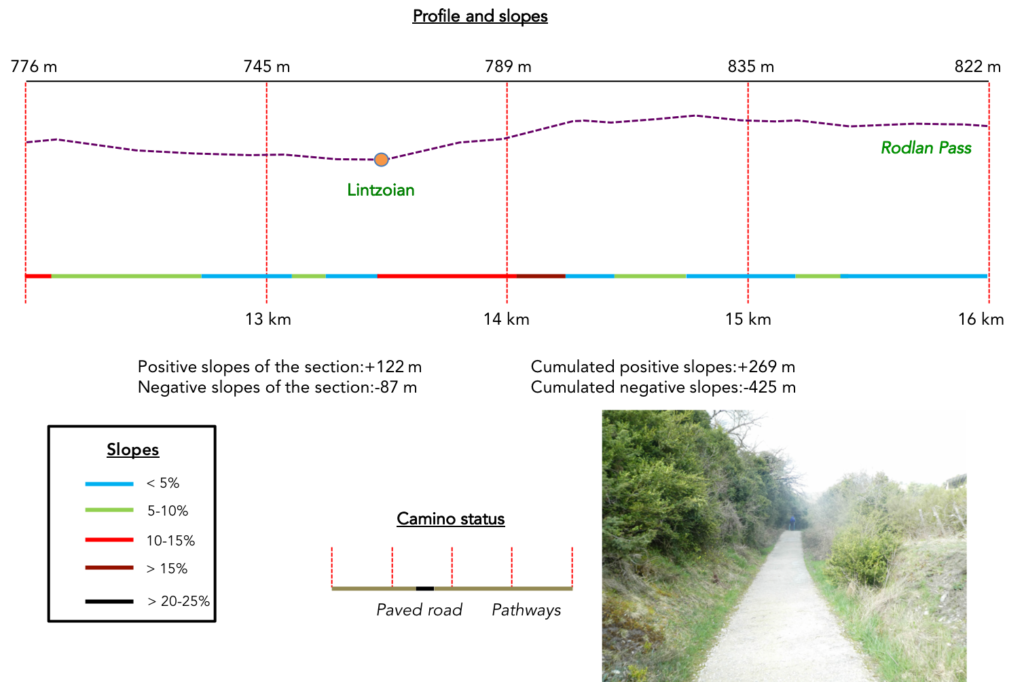

Section 4 : On the way to the great forest of Alto Erro.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: the biggest difficulty of the day, with climbing for a while between 10% and 20%, but it is not long. The rest is just fun.

| Shortly after, the Camino runs along the national road, passes in front of the cemetery… |

|

|

| …and enters an undergrowth along the N-135 road. |

|

|

| A narrow pathway gently slopes down through the sparse deciduous undergrowth. Here, in addition to beeches, also grow oaks, maples and even alders. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino crosses the national road to end up on the other side. |

|

|

| It is then a stony pathway that nods along the undergrowth in the brush. |

|

|

| On the way, black-headed Manech sheep graze on a grass that must not have grown abundantly, when the way arrives at Lintzoian. |

|

|

| The small village is not the most elegant of those encountered here in the region, although you can play Basque pelota. |

|

|

| However, there are beautiful houses, apparently recently redone. |

|

|

In front of you, there is a small passage that will wake you up if you tend to doze off.

| And for good reason. It is a pathway on concrete slabs, which climbs between 10% and 20% for almost a kilometer. In this lunar landscape grow a few box trees and a few brooms, in the rockeries of sharp schists. It is almost always in this kind of place that athletes are active, who quickly disappear from view. The latter, when they walk on the flat, take a break. |

|

|

| At the top of the climb, the pathway arrives in the pines. It is often at the top of the climbs that pilgrims, catching their breath, quibble on the way. An Italian harangues all the pilgrims, in all languages, railing against Europe, which has concreted “his track”. In the past, walking was on stones here, it is true. |

|

|

| On the plateau, you are 7 kilometers to Zubiri, just over 4 kilometers to Alto Erro, a strategic point of this stage, when the pathway joins the Pass road. When we say Pass here, it’s a way of saying it. This is not the Roncesvalles Pass. There is nothing intrepid, inaccessible here. They are just small, gentle hills. The pathway will nod for many kilometers, sometimes with clearings. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway runs on the side of the hill in limestone and brittle shales. The pathway is lined with boxwood under the pines. |

|

|

| Fullness and harmony dwell here. If you are lucky enough, when you pass here, not to be prompted by the loud voices that rise from certain groups of pilgrims who pass all the way chatting, you can develop a feeling of loneliness at your leisure. All you have to do is lower the pace of your steps or pause a little to let them pass. In fact, it is not the presence of potential pilgrims in front or behind you that will change anything. You can ignore all of their dreams, their concerns, think only of you. You will then only share the cabin, this immense and sumptuous forest, as humanity is supposed to share the planet. |

|

|

| When the forest rarely opens up, there are only hills and valleys covered with trees on the horizon. |

|

|

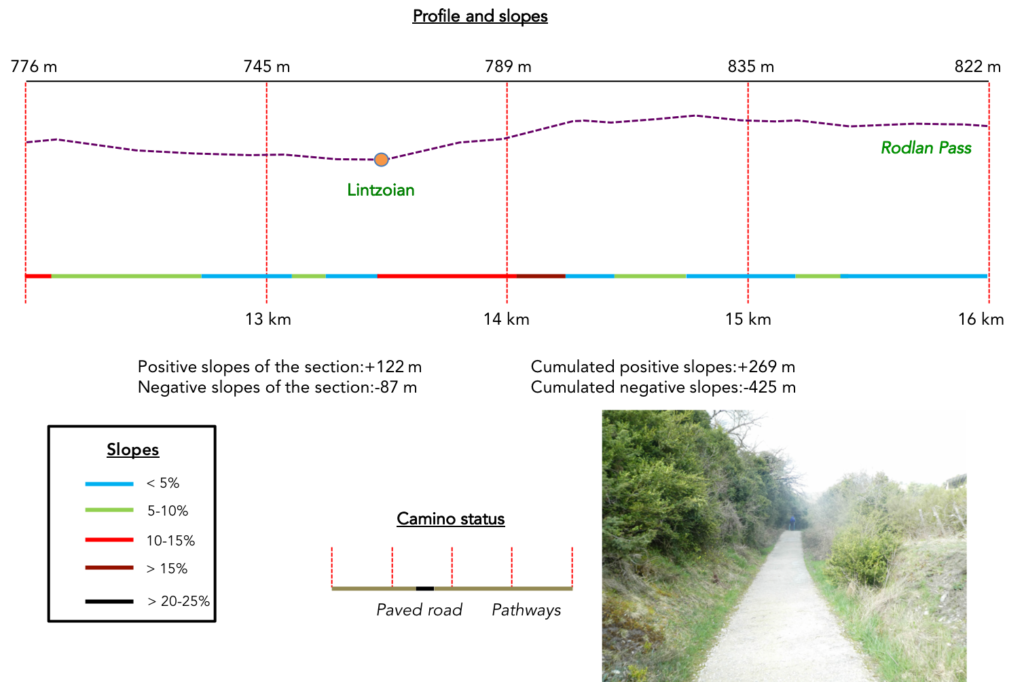

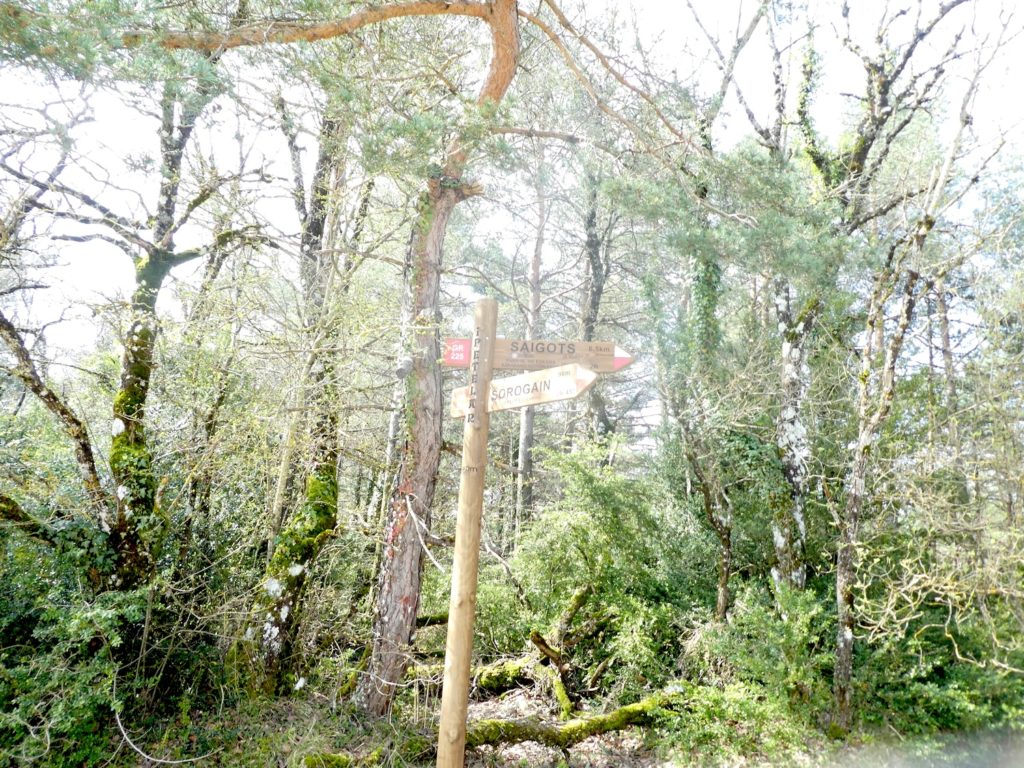

And it is in this universe of peace and wadding, that the pathway reaches a fork which indicates the Paso (Pass) of Rodlan. Here runs another great hiking trail, because there are also GR in Spain.

| Sometimes, the pathway widens a little and nods voluptuously in the woods. |

|

|

| Here, beeches gradually give way to oaks. If you walk alone, then there will be only silence in this disturbing and restful wildness. The pines, like fortresses, rise calmly towards the light, and sometimes their branches are tangled above the boxwood. |

|

|

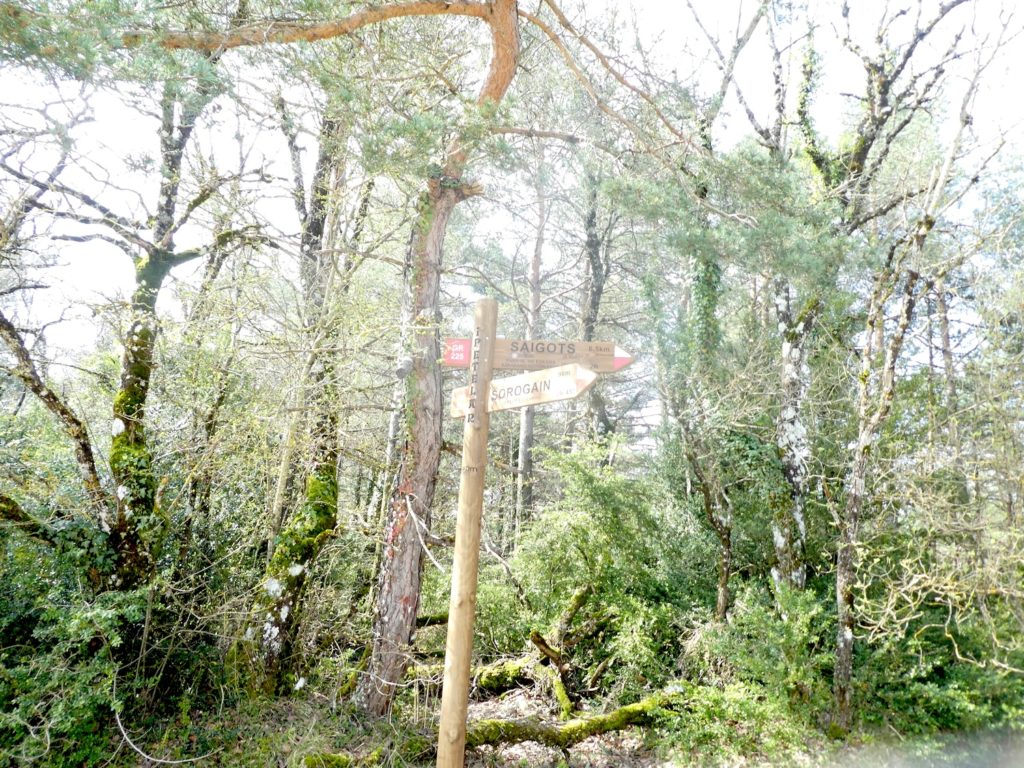

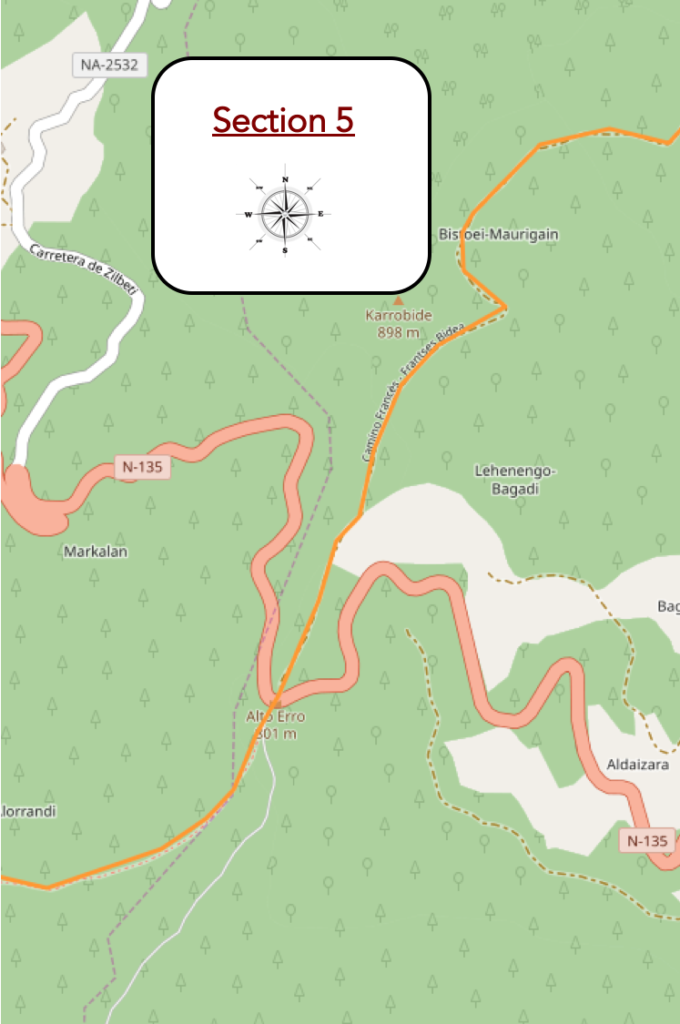

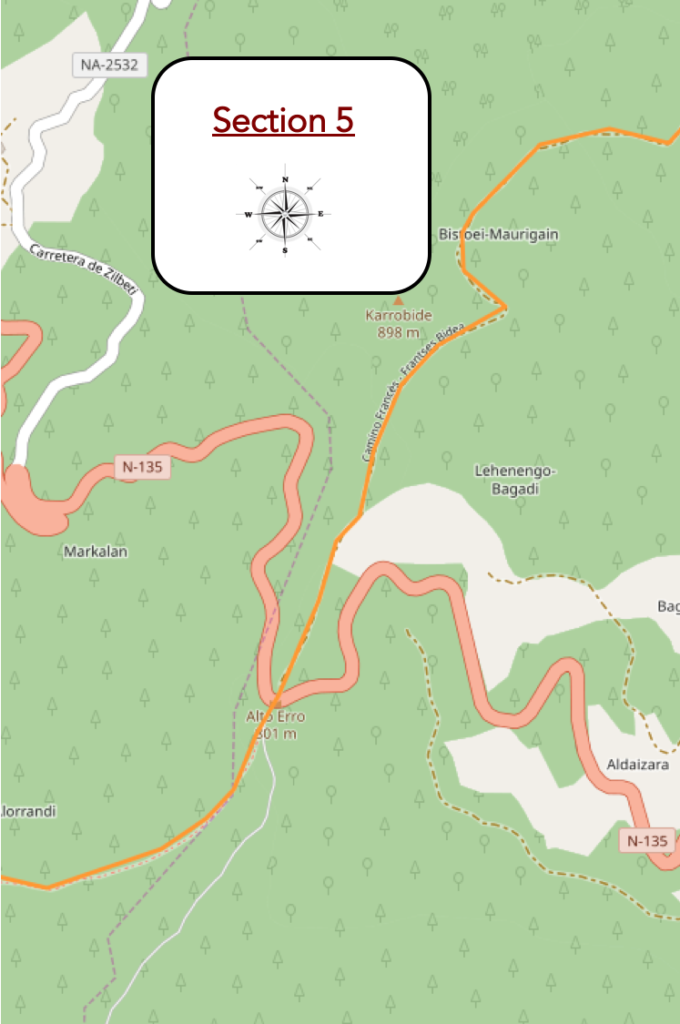

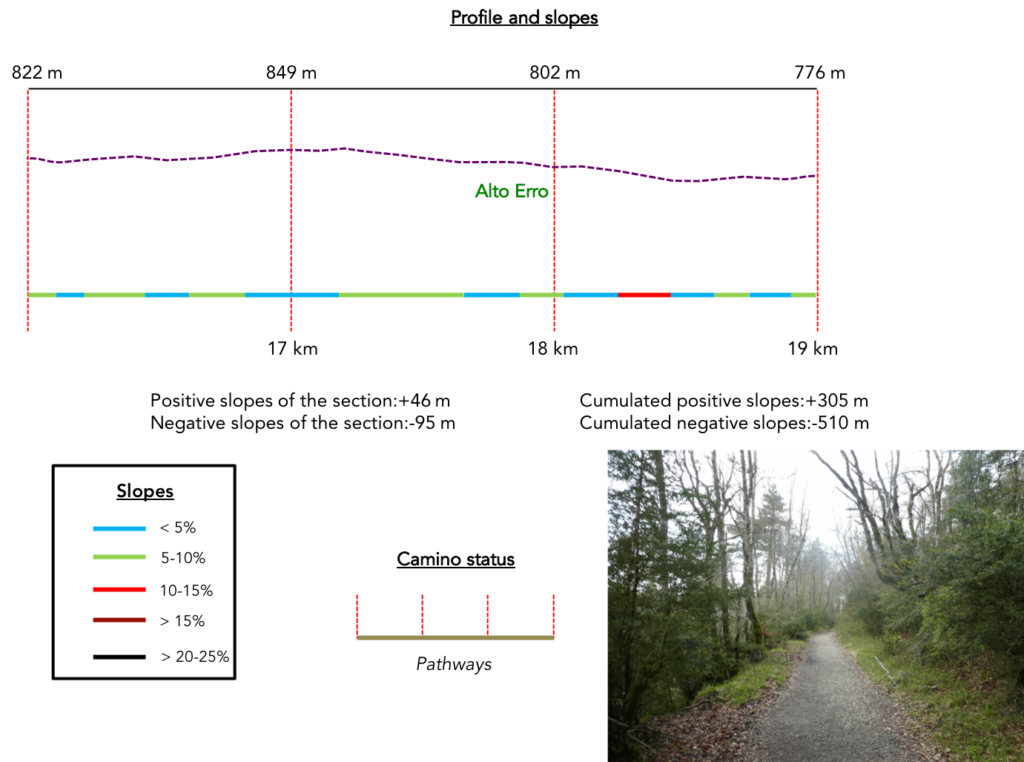

Section 5 : From one Pass to another.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: some slopes, but without difficulty.

| Shortly after, the pathway reaches Rodlan Pass. You will never have had the feeling of climbing a pass on a route of noticeable smoothness. |

|

|

| With the large number of pilgrims on the way, you will rarely be alone. It is also a good way to prove to yourself that you have not taken the wrong course. |

|

|

| Sometimes the limestone outcrops on the pathway, in the shade of pines, large oaks and beech woods, often in the form of shoots. |

|

|

| You’ll walk for a long time with respect through this landscape filled with mystery, even spirits. Mosses, lichens, all this miniature world has developed here according to the opportunities, having fun arranging greenery here and there. |

|

|

| The pathway undulates gently, generally downhill. You will sometimes find the red and white mark of the GR, although in Spain you will hardly pay attention to it, the track being mainly indicated here by the shell and the yellow arrows. |

|

|

| Then, the big beeches come back in force. Stretching their arm towards the clouds, they pray, gather in silence. The moss revels in the ambient humidity, and draws on the branches and trunks hairy arms, phantasmagorical and deformed trunks. |

|

|

| A little further on, the landscape changes and the tall trees disappear in favor of bushes and boxwood. On the stony pathway, the groups of pilgrims get organized, sometimes merging and constantly separating. |

|

|

| At the end of the straight line, the pathway rejoins the N-135 road, at the Alto Erro pass. The traders here do not lose sight of the north, disembarking with their small business, to the great pleasure of many pilgrims, who start commenting on the trip again and again. The Way of Compostela is also a great moment of temporary conviviality. |

|

|

Here you are just over 3 kilometers to the end of the stage, in Zubiri.

| On the way nothing changes. slopes down slightly on the side of the ridge, in the luxuriant vegetation. |

|

|

| Remember the signs of the courses in Spain, mainly the shell and the yellow arrows. |

|

|

| Through the boxwoods, the pathway emerges in a small clearing, with a house in ruins. In front of you, you can see that the pathway will now slope downhill seriously./td> |

|

|

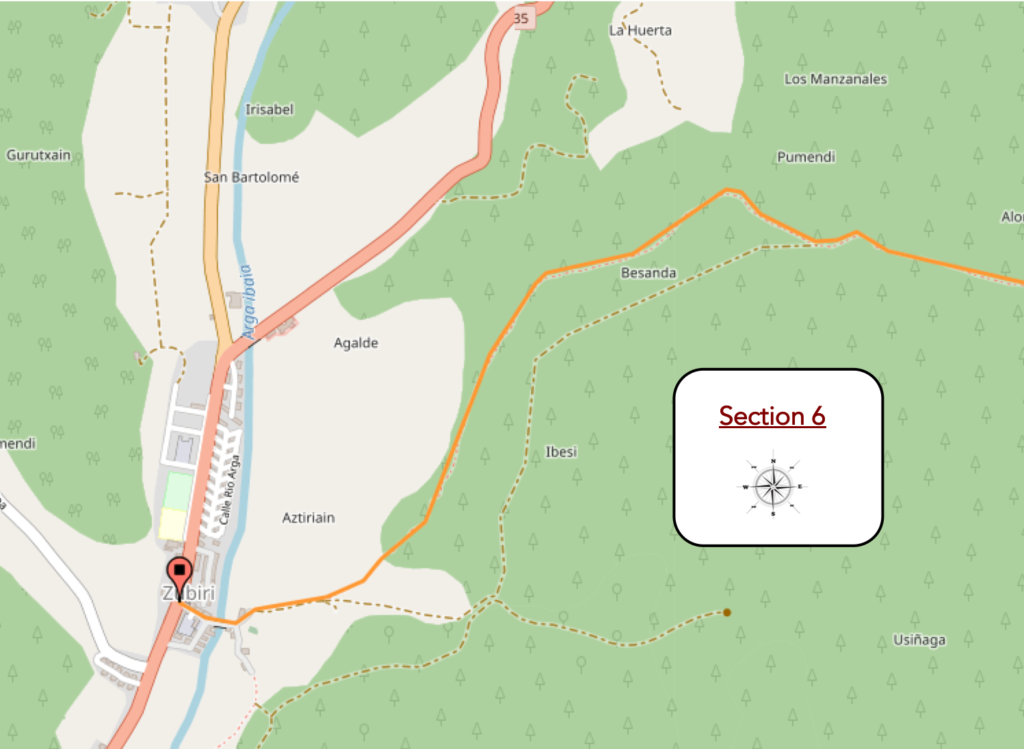

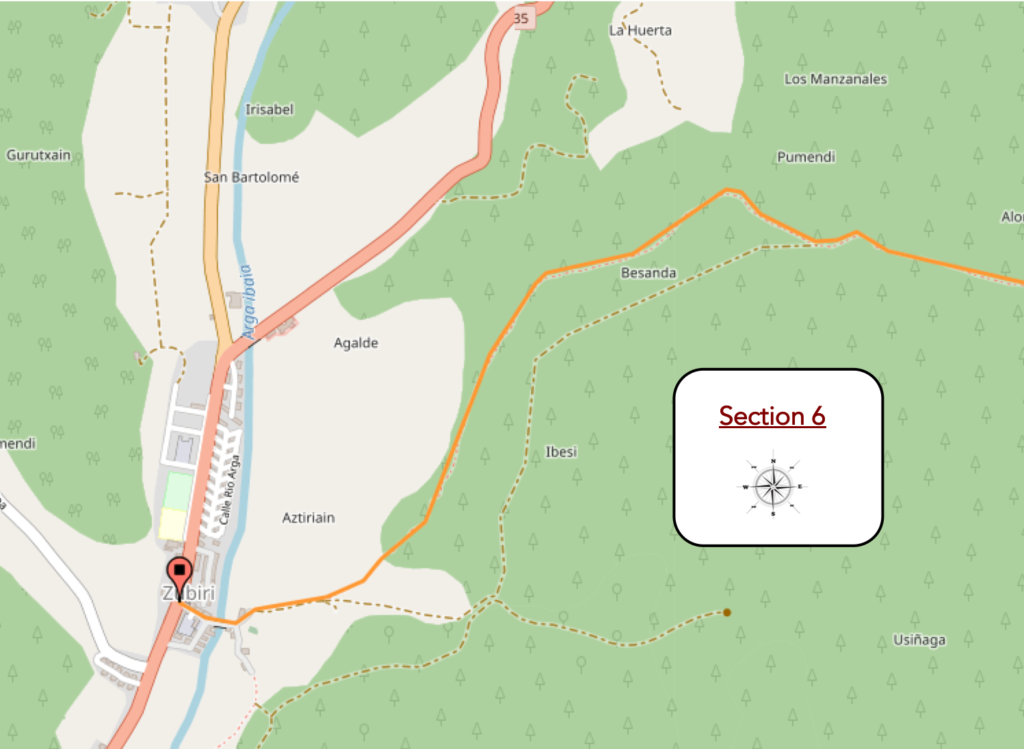

Section 6 : A tough descent on the sharp pebbles.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: breaking-legs course, tough and demanding sloping down.

| The descent to Zubiri is not really what you could qualify as part of the pleasure. In this magnificent desolate universe where box trees and pines grow, the patwayh descends at the beginning, steep, in shales and white and brittle limestones. |

|

|

| It is still nearly 250 meters of altitude difference, between 10% and 20% slope over more than 2 kilometers. Sometimes the pathway, in its great generosity, is more forgiving, sparing the soles of walker’s feet. |

|

|

| When the stones stop attacking you, then the mud can potentially take over. |

|

|

| But, let’s stop whining. The descent is just magnificent. |

|

|

| Soon, you’ll see Zubiri below, all in length in the plain. |

|

|

| So, the pathway, to please you, again offers you a bit of mountaineering on the brittle rocks, then in the canyons created by the rains. |

|

|

| The pathway soon arrives in Zubiri (450 inhabitants). |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, a very beautiful and powerful medieval bridge crosses the Arga river. It is the “Puente de la rabia” so called because, it was said, an animal that passed three times under it cured rabies. |

|

|

| Zubiri is not the most beautiful village in the valley. It is an endless village on the long straight line of the Pass road. But, the village abounds in « albergue », which often resemble barracks. Pilgrims will go to bed early tonight, because there is nothing to do, nothing to see either. |

|

|

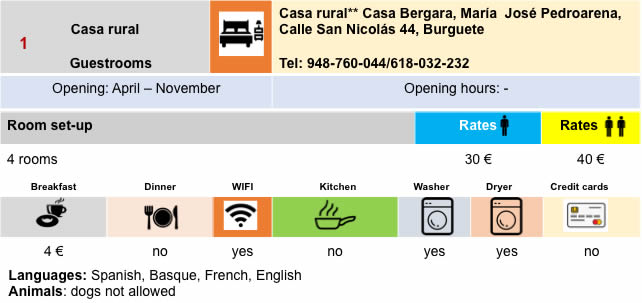

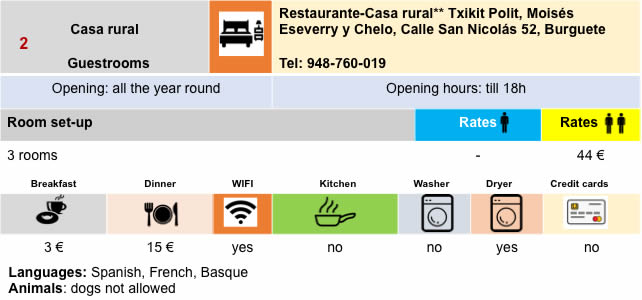

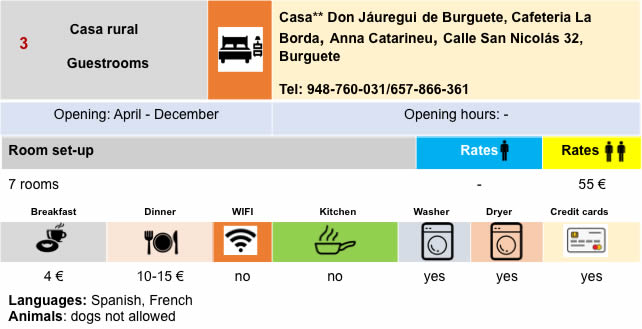

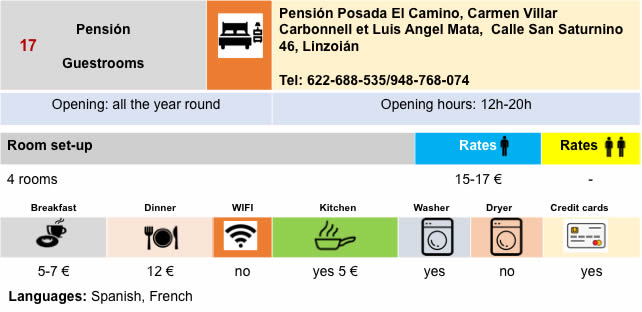

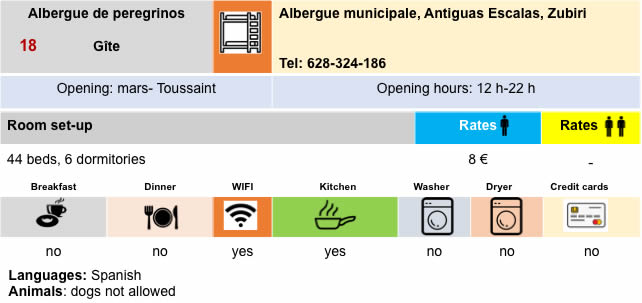

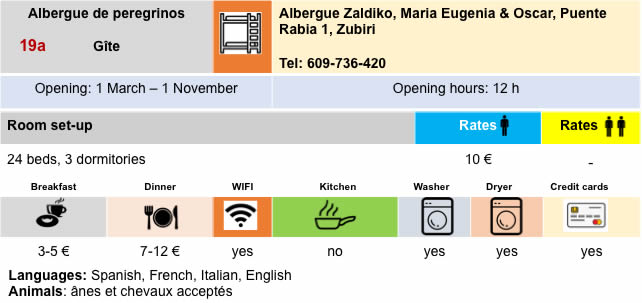

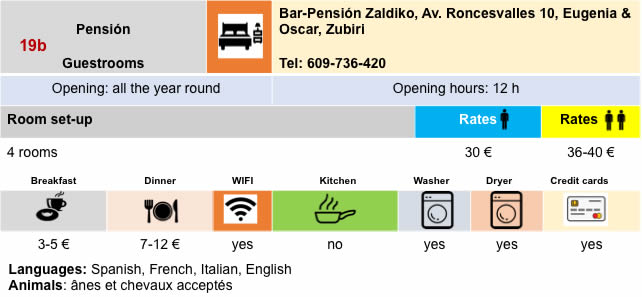

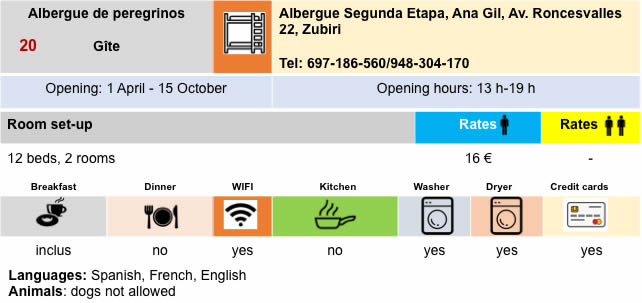

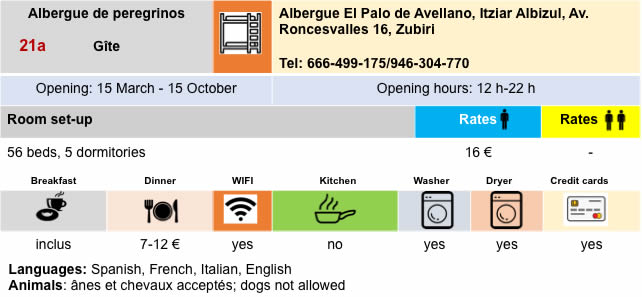

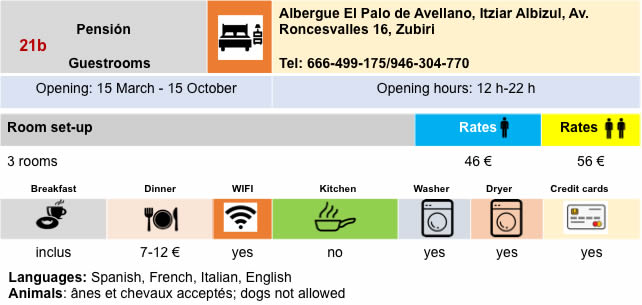

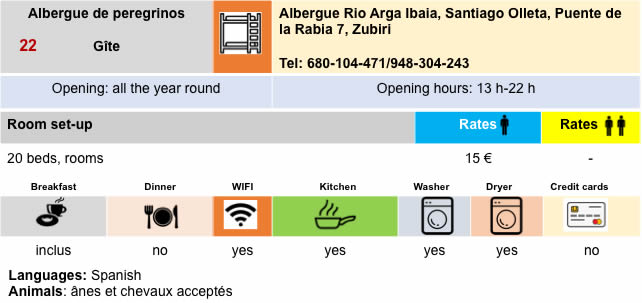

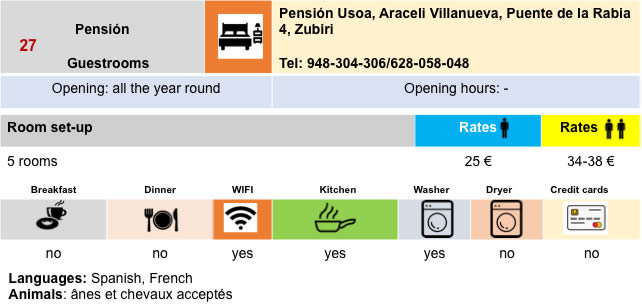

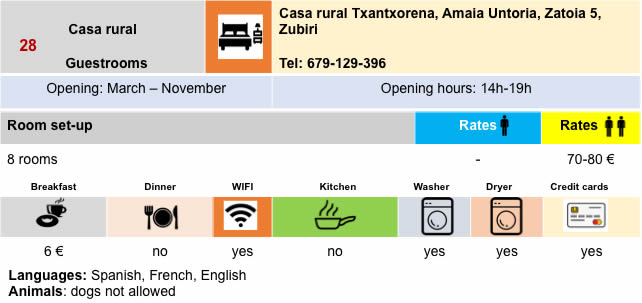

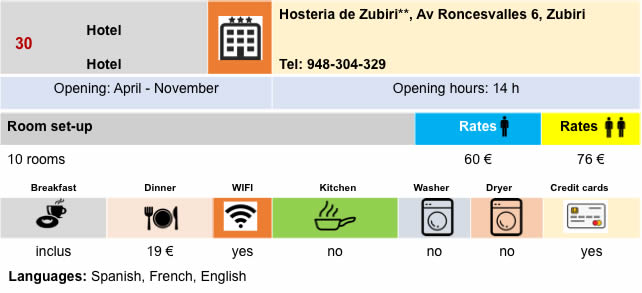

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 3: From Zubiri to Pamplona |

|

|

Back to menu |