Through the Maragateria

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-astorga-a-rabanal-del-camino-par-le-camino-frances-117303011

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

You may have tasted in Astorga the cocido maragato, the star of the local gastronomy. Today, you will have to digest all this. The stage therefore takes you through the Maragateria to Rabanal del Camino, another legendary location on the Camino Francés. The Maragateria is not only local cuisine and delicious very sweet and jammy pastries that are the mantecadas. It is also a patois and a culture. In the past, men wore baggy trousers, a big belt, white shirts, red garters and a big hat. Women also wore hats, lace coats, heavy black skirts and earrings.

The origins of the name Maragato are obscure. According to tradition, the Maragatos could date back to the VIIth century, when King Mauregato and his followers isolated themselves in this remote region during the Arab invasions. Mauregato was also the name of a famous VIIIth century king of Asturias, possibly the son of a Moorish captive. Another explanation is that the Moors who invaded Spain intermarried with Goths (Gotos), giving birth to children who were neither Moors nor Goths, but maurogotos. (Maragatos).

The journey will gradually take you to the foothills of the Montes de León. It is still a magnificent stage, even if most of the route takes place on a new “senda de peregrinos”, “ruta de de peregrinación”, so common to the Spanish route. But here it is not the monotony of the track that you have experienced on the N-120 road. You have left behind cereals and maize as far as the eye can see of the Meseta. You will now progress in a mountain landscape. Certainly, you are not going to climb vertiginous peaks, or venture into deep valleys. On the menu, you will rather have rounded ridges, in an often-rough vegetation, where small oaks proliferate. The route is dotted with stone villages, which almost disappeared at the end of the last century. The Maragateria was a country of muleteers, a bit like a caste of peasants and merchants who sold their products, here and in a large part of Spain. The railroad killed them. But today they have renovated their villages, to make them little jewels, and have put themselves at the service of pilgrims.

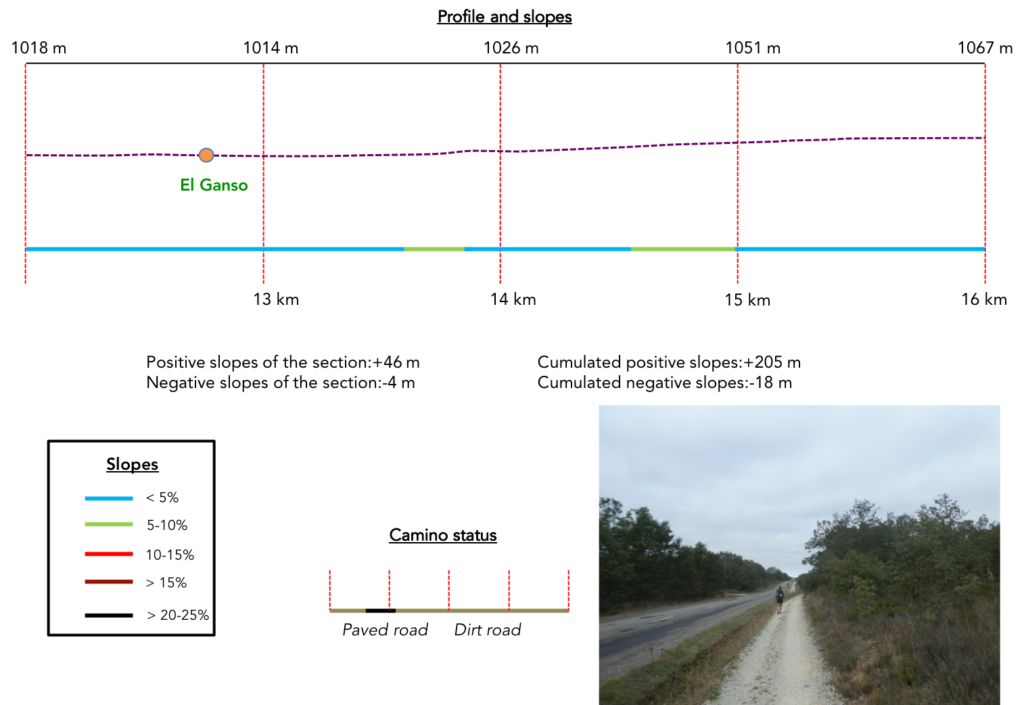

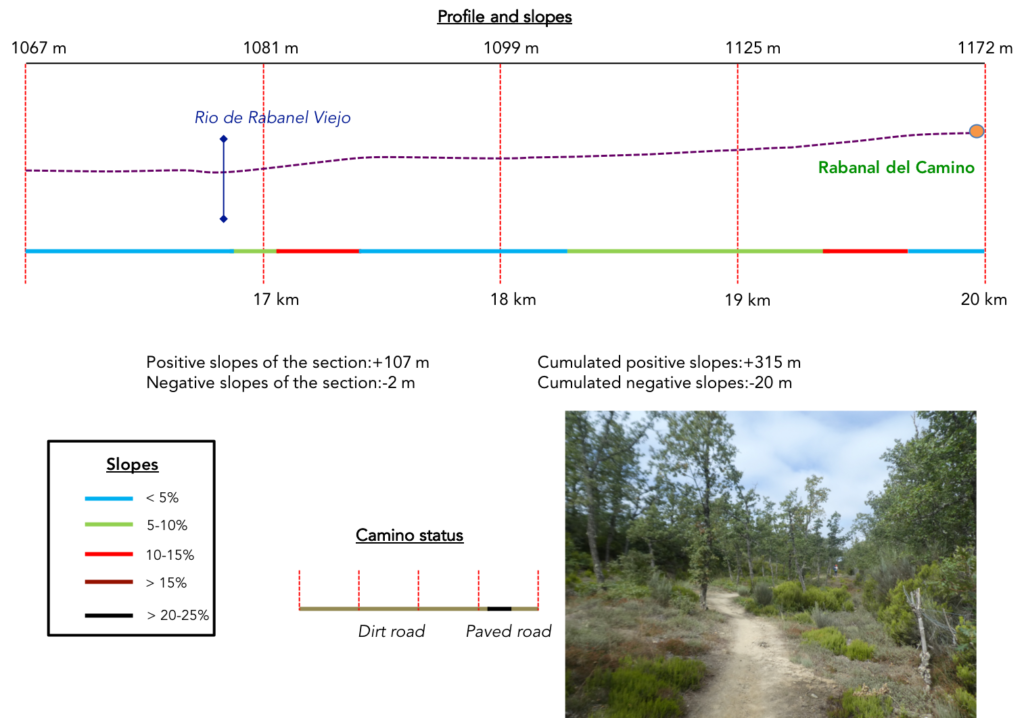

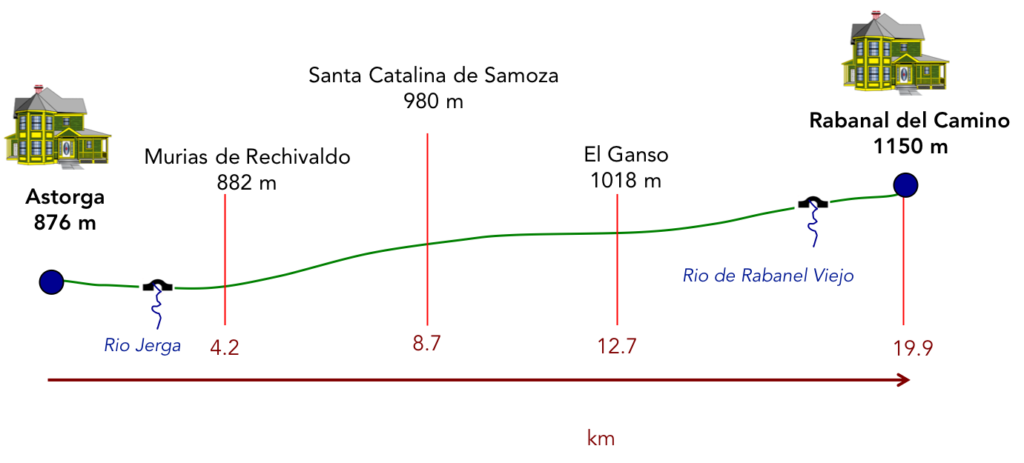

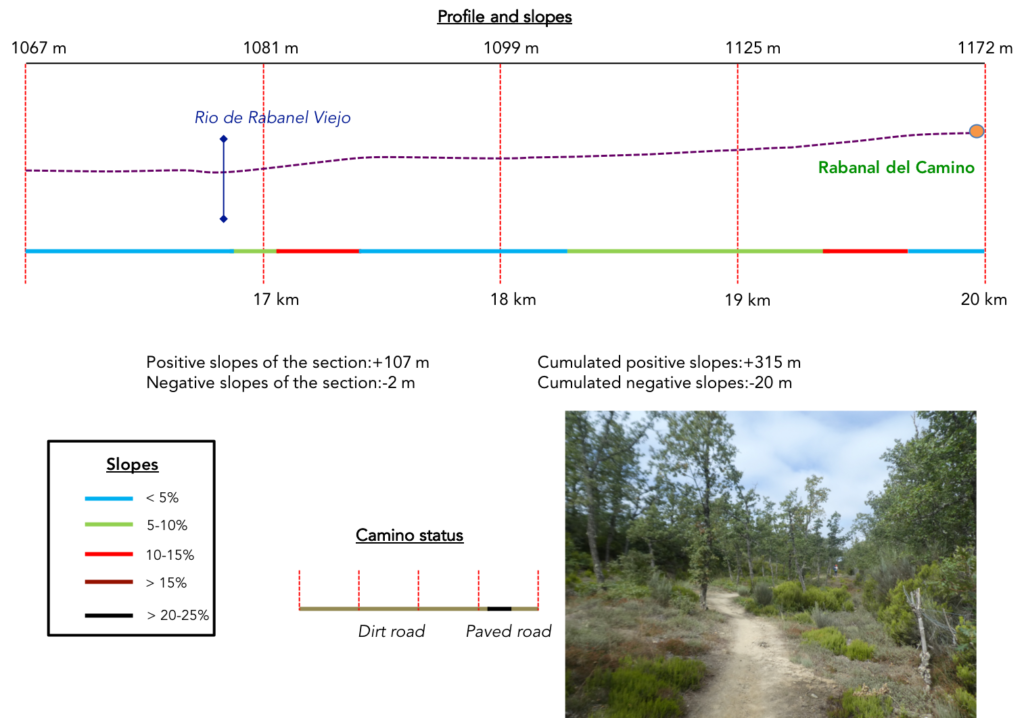

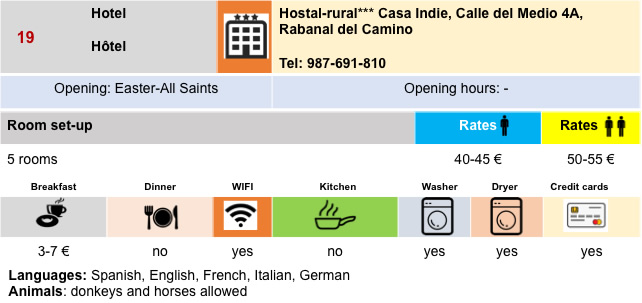

Difficulty of the course: Today, slope variations (+315 meters/-20 meters) are again very low. However, you will have the feeling that the course is much steeper than that. The course climbs a little, but there are many almost flat passages.

Today the pathways clearly have priority, as is the norm in Spain. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. Here, they are often real pathways along the roads, as are all the “senda de peregrinos”:

Today the pathways clearly have priority, as is the norm in Spain. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. Here, they are often real pathways along the roads, as are all the “senda de peregrinos”:

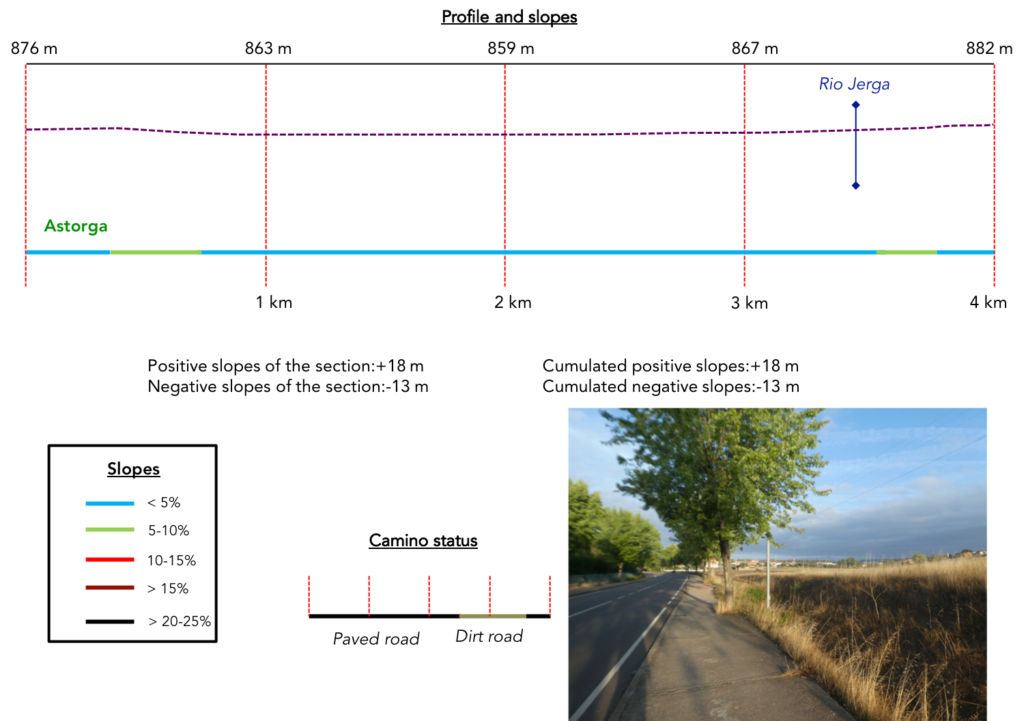

- Paved roads: 4.8 km

- Dirt roads: 15.2 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

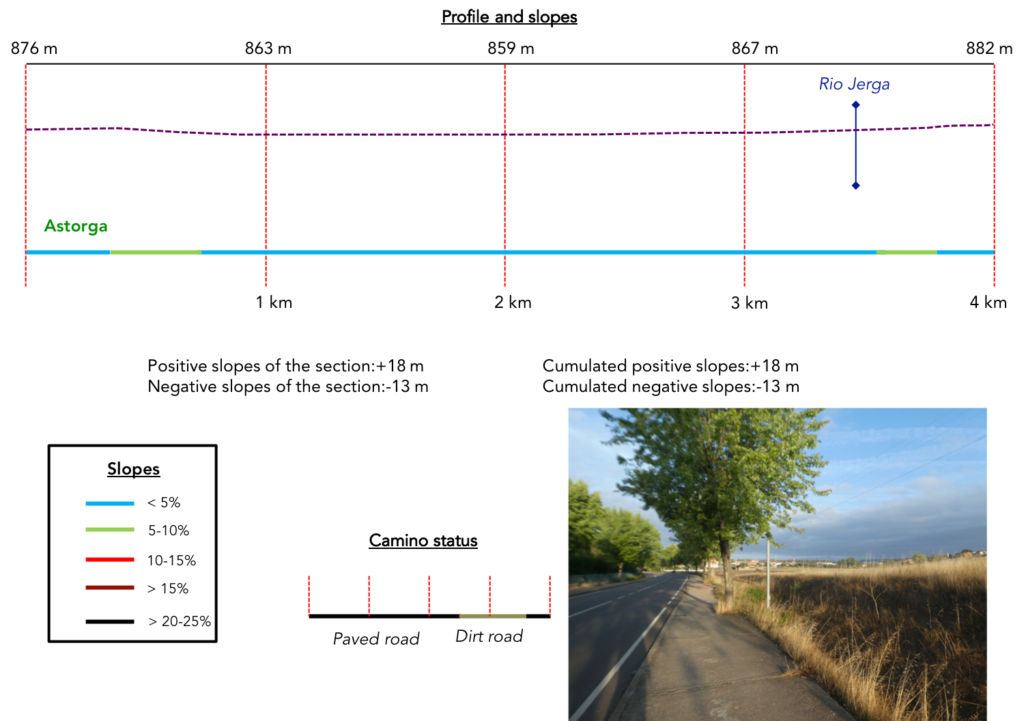

Section 1: Departure for a new “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| The Camino leaves Astorga behind the cathedral and enters a narrow street. |

|

|

| Further on, it crosses more important streets on the outskirts… |

|

|

| …heads to a modern church and descends to the sidewalk towards the exit of the city. |

|

|

| It will progress quite a long time on the sidewalk under the maples. |

|

|

| In front of you appears the village of Valdeviejas, but the Camino does not go there. |

|

|

| It continues to progress under the maples… |

|

|

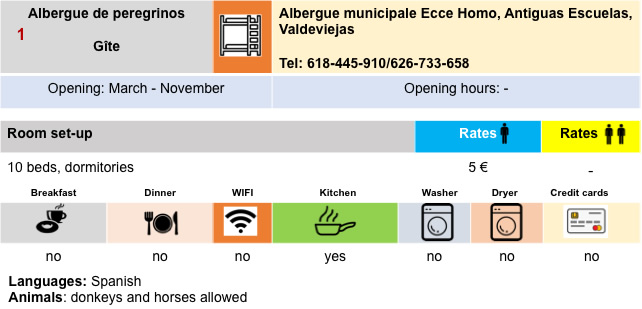

| …before finding the small hermitage of Ecce Homo by the side of the road. The current Ecce Homo hermitage dates from the XVIth century, built next to an old well. It was originally dedicated to San Pedro (Saint Peter). However, according to legend, a woman on her way to Santiago de Compostela stopped at the well to draw water, and unfortunately her son fell into the well. When the mother prayed Ecce Homo, the water rose, saving the boy. Therefore, the name of the sanctuary was changed to Ecce Homo. The chapel was rebuilt in the XVIIIth-XIXth century.

It is always a moment of contemplation for the pilgrims, the opportunity to have the “credencial” stamped and to slip a few coins into the potato chip, to thank the speaker for his services. When it’s open, which is the case here. |

|

|

| Beyond the hermitage, the Camino crosses the highway. Here is the A6, the Autovia del Nordeste. Spain is served by a very large number of motorways. |

|

|

| The Camino is still a few moments on the road… |

|

|

| …before embarking on a new “senda de peregrinos”, “ruta de de peregrinación”, so common to the Spanish route. |

|

|

| IHere you definitely leave the N-120 road. But have you gained from the change? Now it’s the LE-142 road. |

|

|

| You are now 260 kilometers to Santiago and from here the pilgrimage milestones will appear at each intersection. It is both encouraging, but also disappointing to see that you are not progressing quickly. |

|

|

| Black poplars and oaks of all varieties accompany you on your journey. |

|

|

| In fact, it is here a double track and you see the pilgrims choosing the track where the small pebbles hit the soles less. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino passes on the other side of the LE-142 and leaves it. |

|

|

| It crosses the Rio Jerga and heads towards Murias de Rechivaldo. |

|

|

| It is on an ocher dirt road, parallel to the road that leads to the village, that the Camino reaches the village under the maples. |

|

|

| The village does not look like the poor villages that you have often encountered so far in Castile. The street is wide, the sidewalk clean, alongside rather opulent residences.

Murias de Rechivaldo is a village that provided mules and carters to the whole region. The origin of the particular name comes from the word muria, which was a pile of stones, a kind of milestone that the ancient Asturian tribes used to delimit territories. Rechivaldo was undoubtedly the name of a Visigoth owner of this region, who came to this region to flee Arab domination, who distinguished himself against the Arabs. His courage was so great that these lands became the “land of Rechivaldo” and Murias de Rechivaldo became a motto of the Christian reconquest. |

|

|

|

|

San Esteban Church, in neoclassical style from the XVIIIth century, has a belfry typical of the region. There is an outside staircase that leads to the belfry. As is also quite common in the region, there will undoubtedly be a stork’s nest at the top of the belfry.

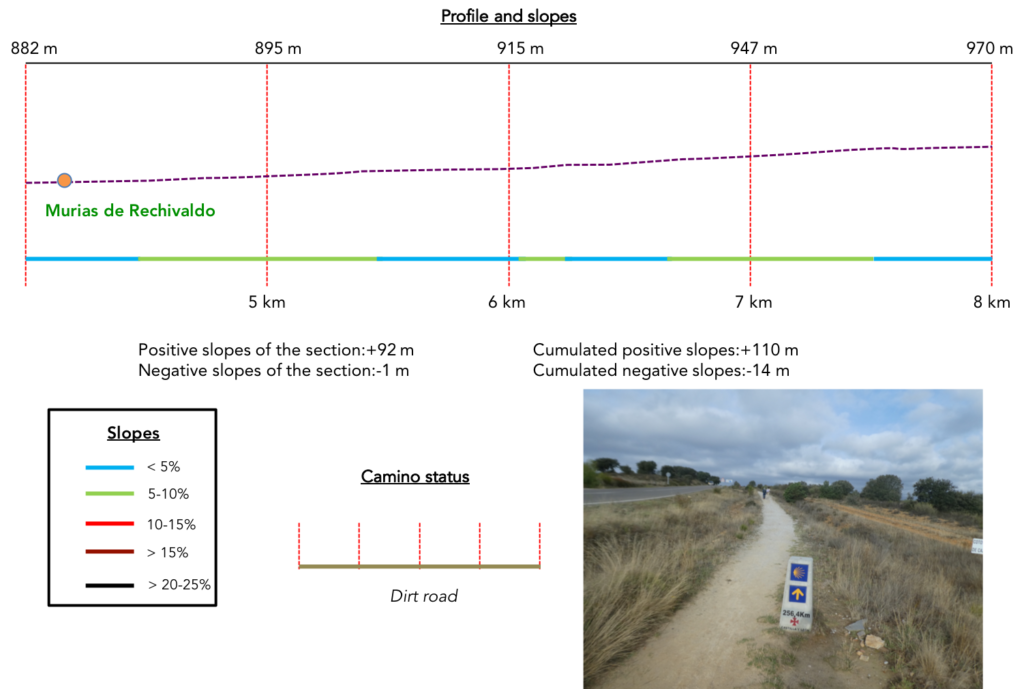

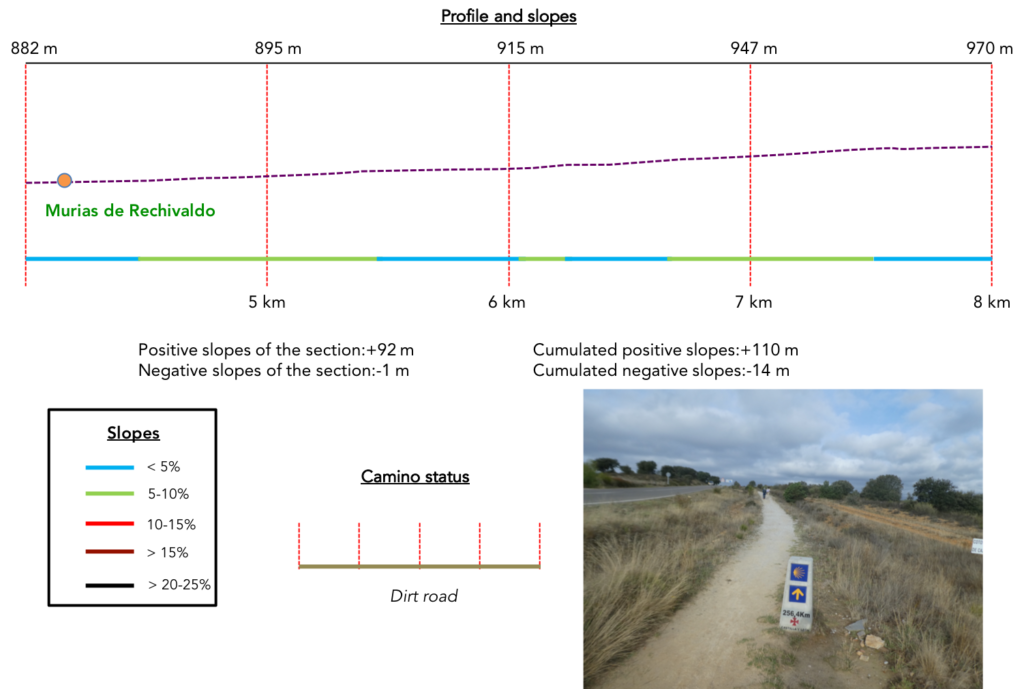

Section 2: Some undulations on the “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without problem, even if the course climbs constantly in an imperceptible way.

| The pathway crosses and leaves the village, to quickly find the dirt road. The landscape will change. The soil on these ridges is not very good for agriculture. Farmers practice rather the breeding, but you will not see many sheep and cows on the course. |

|

|

| You often hear the gravel sizzling behind you. It is the cyclists who make the way, often with a minimum package. Luggage transport companies are very active on the Spanish route. |

|

|

| Here you have the choice between ocher dirt or gray gravel. But, whatever your choice, the pathway is not smooth. |

|

|

| The pathway climbs, but imperceptibly. It is a pleasant walk between bushes, rosehips, herbs roasted by the sun, with sometimes dwarf poplars or stunted oaks, most often holm oaks. |

|

|

Sometimes heavily laden cyclists run by, real pilgrims in a way.

| The straight Camino continues its merry way in this gentle nature… |

|

|

| … before arriving at an intersection with the LE-142 road. Here, it will now be the LE-6304 road that will accompany you. Roads rarely let you travel alone on the Camino francés. As the pathway climbs along the ridges, the vegetation changes to oaks, heather, bushes and wild thyme. A little further on, the harsh climate eliminates the trees completely, leaving only rough, almost impenetrable brush. |

|

|

| Then, the slope is a little steeper on the gravel pathway at the edge of the road. As usual, the organizers of the Spanish course have multiplied the signs to signal potential dangers, which in fact hardly ever exist. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway nods in the rough vegetation. There are no crops here, only something resembling a vast moor. Throughout this region the bushes often resemble broom, but in fact true broom is quite rare. These are most often species of cypress, varieties of laburnum, lavender or artemis, and many other herbs known only to botanists, professionals or enlightened amateurs. |

|

|

| Occasionally, a few vehicles run on the road, perhaps to justify the presence of the signs. |

|

|

| At the top of the gentle climb, you can make out the village of Santa Catalina de Samoza in front of you. |

|

|

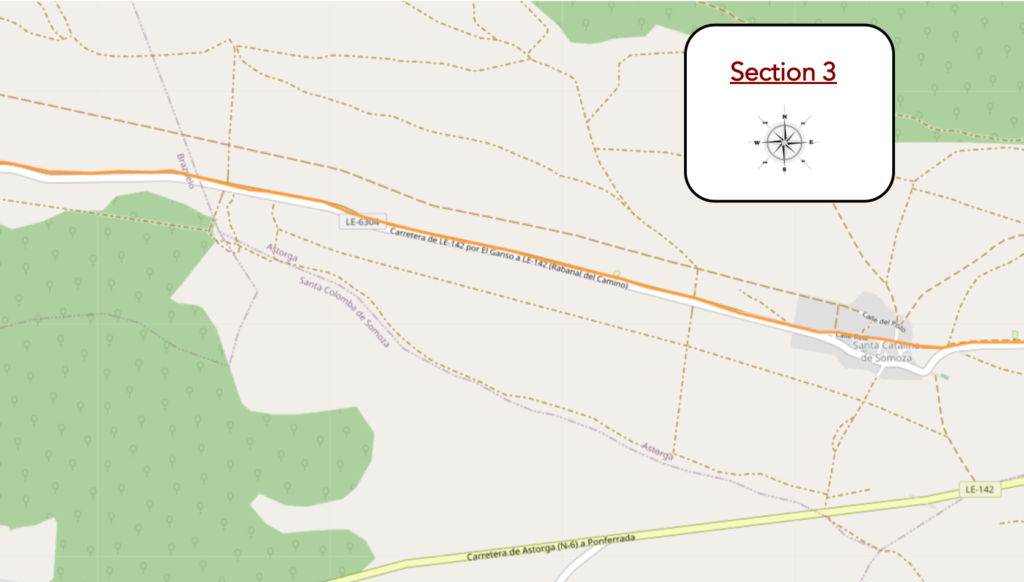

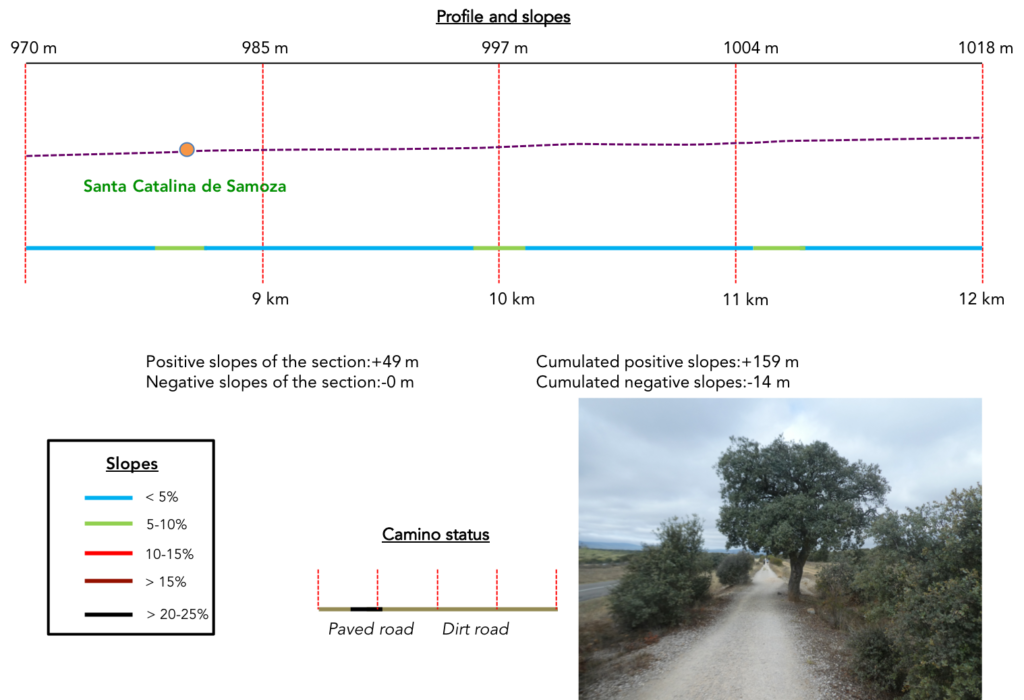

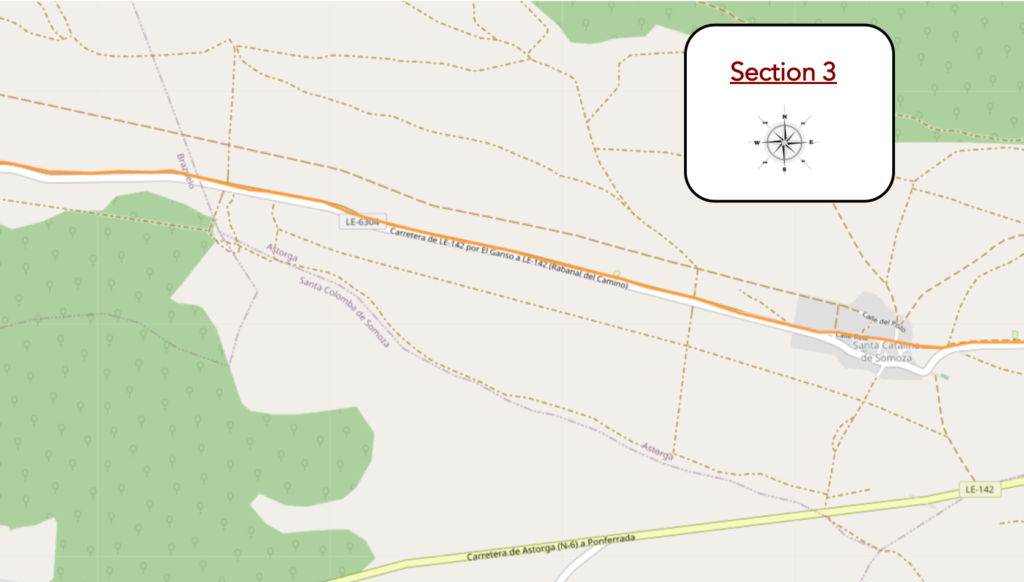

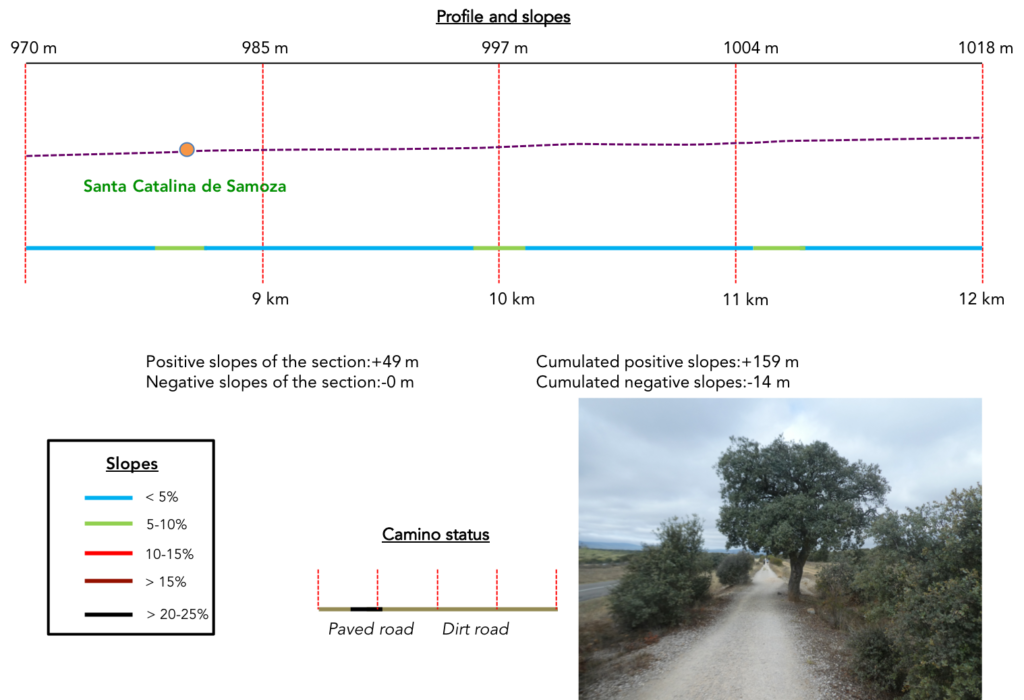

Section 3: Some new undulations on the “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| You always have the choice to walk on the gravel, on the small stones, which roll under your feet, or on the stony ocher ground. Shortly after, the pathway heads to a picnic area. |

|

|

Your gaze always embraces a hill as vast as it is wild.

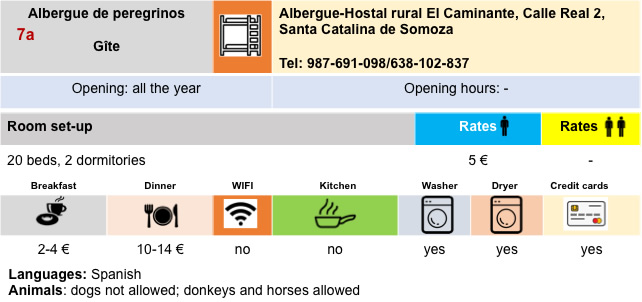

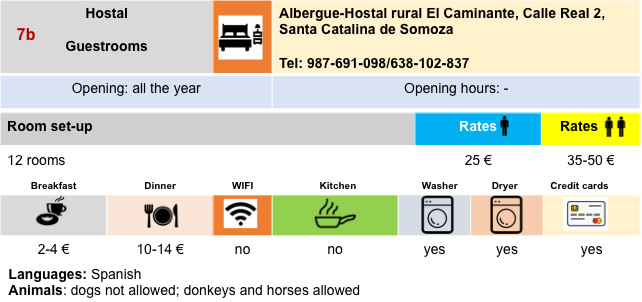

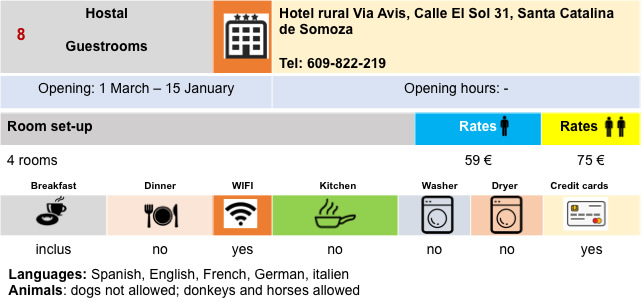

| Gradually, the pathway approaches Santa Catalina de Samoza. The village is another typical Maragato village of the region, in its layout, its typical muleteer houses. In the Middle Ages, the village was known by the name of “Orchard of the Hospital”, because of the presence of a hospital for pilgrims which was baptized thus. Then, the village took the name of Santa Catalina, since it was the original name of the church, dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria, around which the village was built. However, the parish church today is dedicated to Santa María. Like many villages in this region, it bears the suffix Somoza, from the Latin sub montia (under the mountain). In Roman times, this name was given to the entire region. Calling it the Maragatería is a relatively modern invention. |

|

|

| A pathway, along the dry-stone walls, leads to the village. These are the first stonewalls that we have seen for a very long time. The village has only about fifty inhabitants, probably all devoted to the service of pilgrims. |

|

|

There are often crowds here in the bars of this charming village. The place has a great reputation for Jacobean hospitality, with rare hospitality. There were hospitals for pilgrims here in the Middle Ages, which no longer exist today. There is even an emergency establishment with bandages available. The village is another example of the “pueblo-camino” built around a main street, Calle Real.

| A beautiful rough stone church with a bell tower stands at the edge of the main street. Closed to our passage, it’s known for an image of San Blas, the patron saint of the village. The church dates from the beginning of the XVIIIth century. It has a bell tower and a porch above the entrance, both typical of the region. |

|

|

| This village, like the others in the region, was destined for certain death. But the Camino has taken off for about twenty years. So, people renovated the dilapidated houses, so that today the ruins have almost disappeared and you find magnificent stone houses, sometimes decorated with flowers. The low stone houses have roofs of locally quarried slate, although some originally had thatched roofs. The windows in these houses are tiny to keep the heat in. You sometimes see overhanging balconies, protecting the entrance from the summer heat wave and from the snow in winter. Because the climate is harsh in the valley. Sometimes a large stone placed near the front door serves as a bench. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the village on the LE-6304 road… |

|

|

| … before embarking on a new “senda de peregrinos” which pilgrims love. |

|

|

| Here, a local has set up his small business where he tries with difficulty to sell a few wooden pilgrim sticks, which are soon no more than relics on the Camino de Santiago. |

|

|

| The pilgrimage milestones then follow each other on a long straight line that dawdles, with the mountains of León in the background, which you will have to cross one day. |

|

|

| The burnt grass curls endlessly. The Camino unrolls its uniform carpet in an immensity that sometimes makes you dizzy. |

|

|

| Do not imagine that here it is only a landscape of rockeries, disheveled grasses, oaks of all kinds or rosehips. There must also be some meager cultivation, as a portal in the road sometimes suggests. It is hard to imagine that these doors hide second homes. |

|

|

| As the pathway always remains split between gravel and ocher dirt, cyclists prefer the dirt, which seems to be less dangerous for the tubulars of bicycles. |

|

|

| Further on, the vegetation is more present, represented above all by holm oaks, the Spanish encinas. |

|

|

| Sometimes, pilgrims, or rather sportsmen pass you and disappear in front of you. These, often lean to the bone, are of all ages. We repeat it again here. These athletes, you will find them further on, seated on a terrace. On the other hand, if the case arises with a pilgrim carrying a big bag, that one, there is little chance of seeing him again one day. |

|

|

| Further on, another pilgrimage milestone to indicate that the pathway continues straight. Is it really a surprise? |

|

|

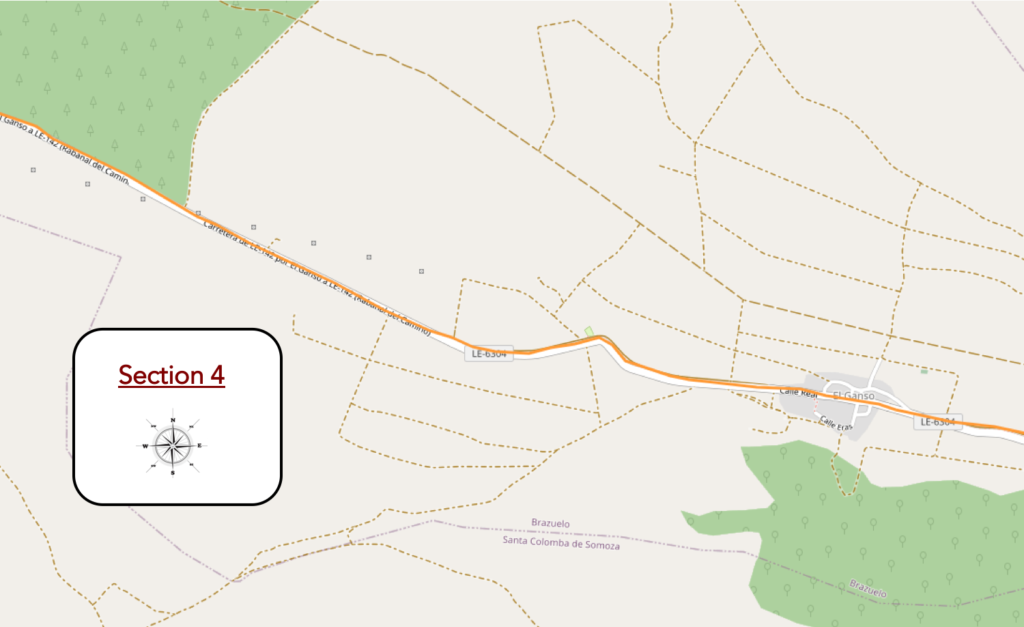

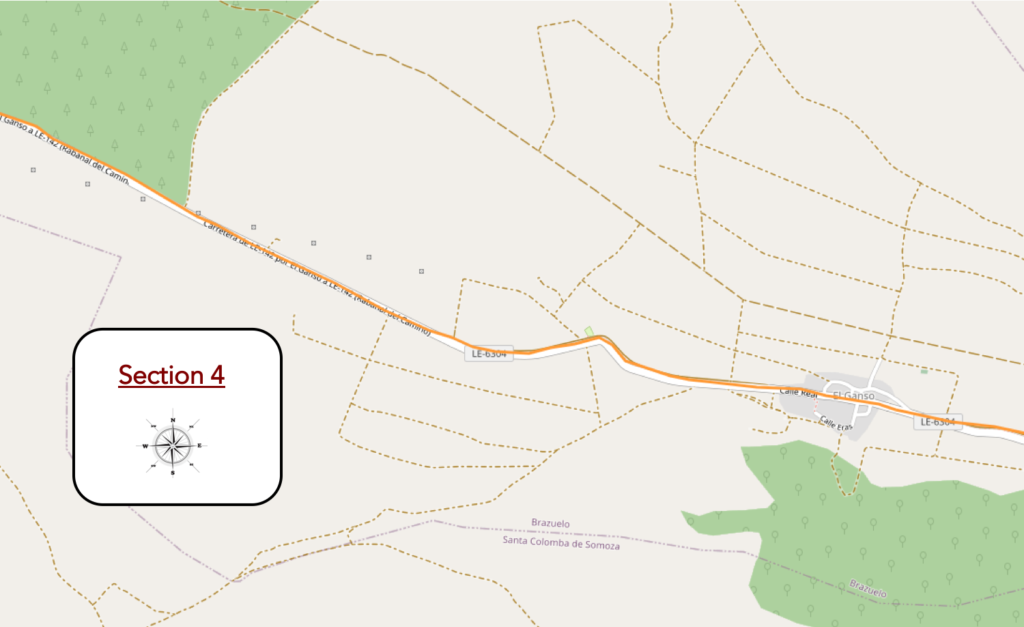

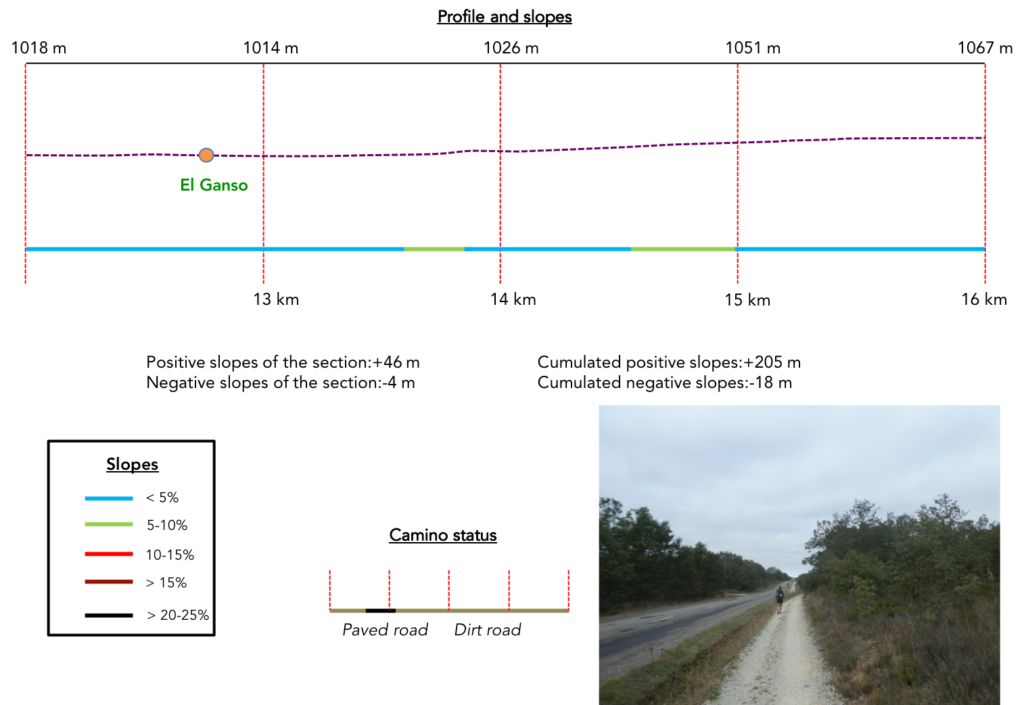

Section 4: Again, and again on the “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Further on, you can see more cultivated fields, in the middle of the moor. You are approaching El Ganso. |

|

|

| Soon you’ll see the village. Here, for an eternity now, cows are grazing, some specimens of which for once are not indifferent to the passing pilgrim. A passing Spaniard told us that according to him, these cows were of the Asturiana breed, cousins of the Aubrac breed, in France. But, he could not exclude that in the number, there were also some Rubia Gallega cows, cousins of the French Limousine. We could not contradict him, having no expertise in Spanish cows. In the North of Spain, in Asturias, in Cantabria and in Galicia, there coexist a good ten breeds of cows, unknown in France or Switzerland. Be that as it may, the Spaniards who love horns, keep their cows their prerogatives, which changes from Holsteins, these cows which are nothing more than dangling teats, dehorned for life. |

|

|

| But, of the poetry of cows, most pilgrims care about it as their first panties. They pass here, without even glancing at them. They have other things to do. Cows can be found in butcher shops, right? |

|

|

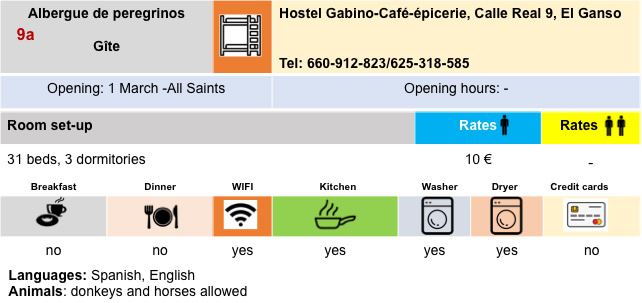

| Further on, the Camino leaves the LE-6304 road, climbs into the village between the stonewalls. El Ganso means goose. In the XIIth century, the village had a small church and a pilgrim hospital, Hospital de San Justo, run by Cluniac Benedictines. A small monastery was founded there in the XIIIth century. Nothing remains of either. |

|

|

| El Ganso is the twin sister of Santa Catalina de Samoza, with the same story, decay followed by resurrection thanks to the Camino de Santiago. Many houses in El Ganso were thatched-roof houses, muleteer houses. Many of them nowadays have roofs covered with tiles or slates, which are much easier to maintain. |

|

|

| The village also has a modest church, in stone, from the XVIth century, the parish church of Santiago, with an openwork bell tower typical of the region, and bells. According to an ancient local legend, the Apostle James himself celebrated masses here. Built into an outer wall is a medieval cross-shaped burial stone, possibly from a pilgrim cemetery near the village. |

|

|

| On leaving the village, the Camino finds the “senda de peregrinos” back, along the LE-6304 road. |

|

|

| Here, the landscape is more agricultural than before, with the presence of many cultivated fields. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway, still just as stony, stops near a picnic spot, neglected by pilgrims, as often. |

|

|

| Beyond the cross on the picnic spot, the pathway runs back along the road. On this gravel pathway, the oaks provide a nice contrast. There are, so to speak, only oak trees capable of growing on this ungrateful land. |

|

|

| Sometimes the Camino takes on the air of a marathon. Here a group of Spanish walkers is in a hurry: to reach the finish. So, they move forward on the road, the stones limiting their speed. It’s amazing how loud the Spaniards speak when they walk in groups. For little, you should hear them all the way to the depths of Andalusia. If the Americans mingle at the concert, which happens, so you don’t even hear the sound of your footsteps crunching on the gravel. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino reaches a large forest of slender pines, which it will skirt for almost a kilometer. |

|

|

Section 5: A stop at the beautiful village of Rabanal del Camino.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : sometimes steeper slopes, but nothing very difficult.

| Here, the pine forest is of formidable beauty, a lost open-air paradise. |

|

|

| You soon learn from the pilgrimage milestone that you are 246 kilometers to Santiago. Just nothing, right? Especially for pilgrims who come from northern Poland or Germany. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino comes to a crossroads. Here, a street vendor sells her creations by the side of the road. You are at a place called Ponte de Panote, where the Rio de Rabanel Viejo flows discreetly. |

|

|

| Here, the Camino leaves the “senda de peregrinos”, along the LE-6304 road, for a little recreation in the undergrowth. |

|

|

| The pathway climbs steadily through the oaks. It is a suspended moment, like a postcard of serenity and wildness at the same time. |

|

|

| As you slope up, the landscape becomes more grandiose and lonelier, and the soles roll on the stones. |

|

|

| At the top of the climb, the pathway joins the “senda de peregrinos” back, along the road. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway deviates a little from the road to cross an undergrowth of oaks. |

|

|

| Then, coming out of the wood, it finds and runs along the “senda de peregrinos”, until you find a small road, which is the direction of the heliport of Rabanal. |

|

|

| It is then again, a journey that extends along the road… |

|

|

| …to reach the first houses of Rabanal del Camino. At the bar, there are people and discussions aloud, as has become the prerogative of the Camino de Compostela. |

|

|

| Next to the bar, it is more religious. It is the hermitage of Bendito Cristo de la Vera Cruz, a XVIIIth century Baroque temple where an image of the crucified Christ is venerated. Closed often, as usual, especially during siesta times. Today, the chapel presides over the cemetery. |

|

|

| Following Calle Real, which coincides with the Camino de Santiago, is the small XVIIIth-century Hermitage of San José, the Pilgrims’ Oak, and a house where King Felipe II would have spent the night during his pilgrimage to Santiago. This is why this street is called Calle Real. The slope is steep up to the top of the village. Like many other villages in this region, the village is a “pueblo-calle” laid out along a main street. In Rabanal, the street is paved.

The first references to the existence of Rabanal del Camino date back to legendary events such as the marriage of a knight of Charlemagne with a Saracen princess in the VIIIth century. It is certain that the village has had a centuries-old tradition of welcoming pilgrims before they take the steep track that climbs and crosses the Montes de León. It is believed that the Templars maintained a garrison there as early as the XIIth century, to protect pilgrims crossing the pass to Ponferrada. The village is included in the Codex Calixtinus as the end of the stage of the Camino which begins in Astorga. Traditionally, it was the last stop before the demanding crossing of the Montes de León, dangerous because of wolves and bandits. |

|

|

| This village was dead in 1980, when the English installed a first gîte here. And yet, Rabanal is cited in the Codex Calixtinus as a milestone. During the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, Rabanal was a maragato stronghold, therefore a village of muleteers. Then, the decline of the muleteers, as we said in the Astorga stage, led to a migratory movement towards the cities. Rabanal went from more than 200 inhabitants in 1960 to only 40 in 2000. Since the English, the village has been completely transformed with renovated stone houses, bars and « albergue » in abundance. It is so pleasant here, that even if the pilgrims for the vast majority know nothing of the Codex Calixtinus or do not care about it, they stop here to spend the night. That’s life. A little publicity, European funds, and recognition by UNESCO as a Universal Way, and the deal is in the bag. Long live the Spanish Compostela. As the Way of Compostela gradually loses its soul, we wonder whether one day we could not transpose all this trade to Kamchatka. Of course, there is no moralizing here. People go on the Camino de Santiago for their personal reasons. And there is nothing to complain about it. It is their pleasure and their right. |

|

|

|

|

| At the top of the village stands the parish church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, with its XIIth century Romanesque apse, surmounted by a slender XVIIth century bell tower and a clock. It is of Templar descent. |

|

|

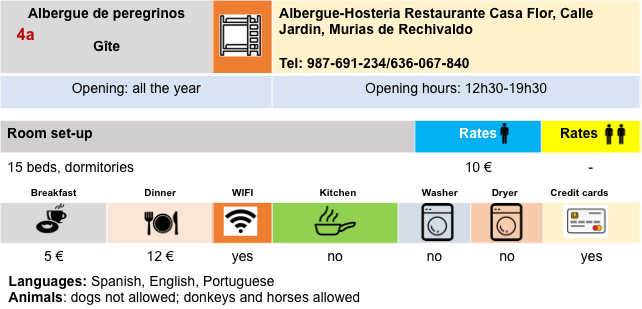

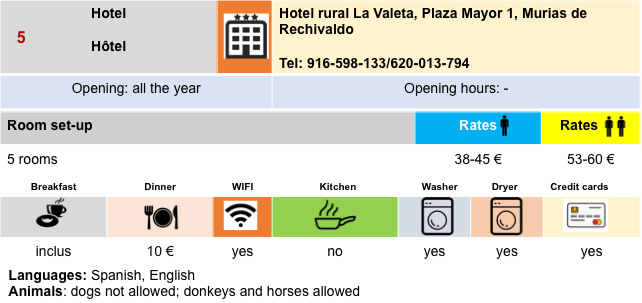

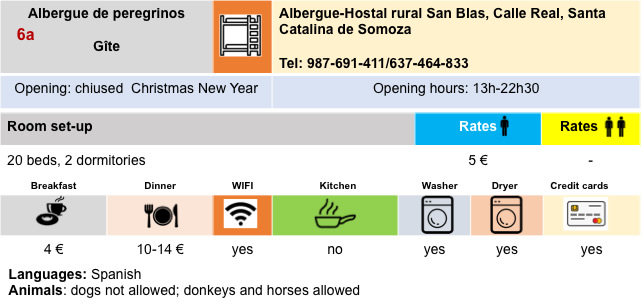

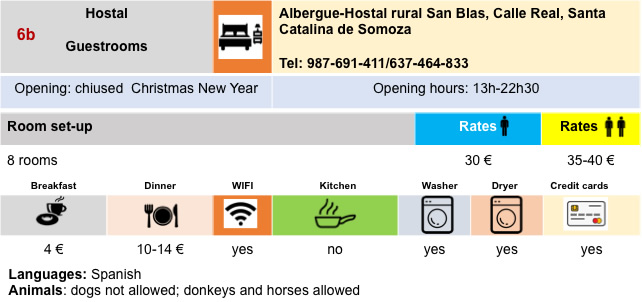

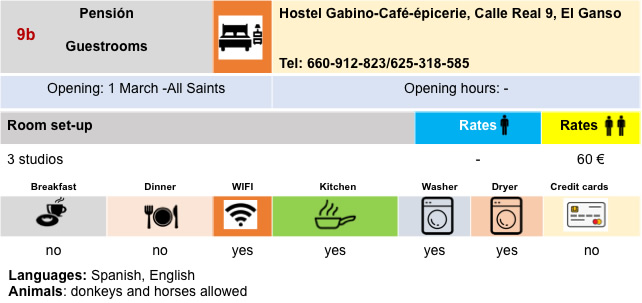

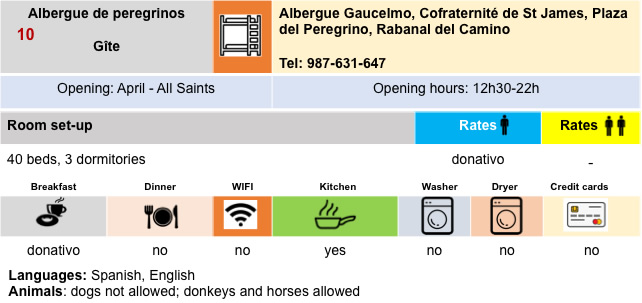

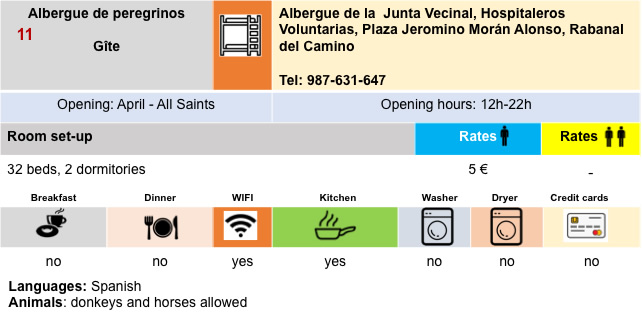

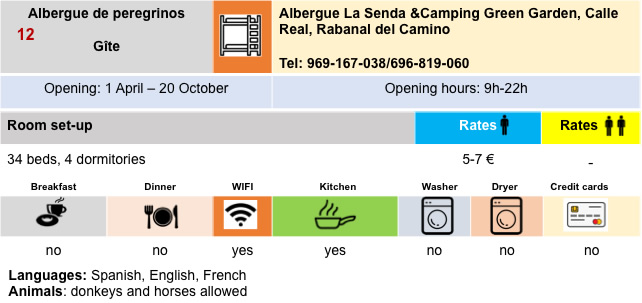

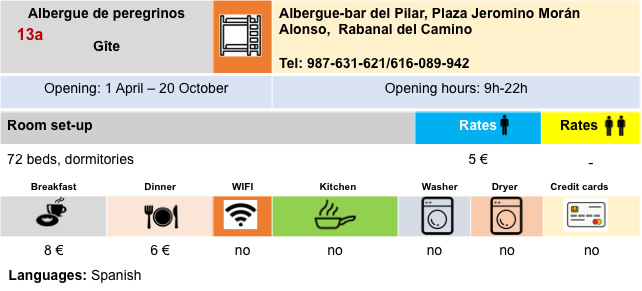

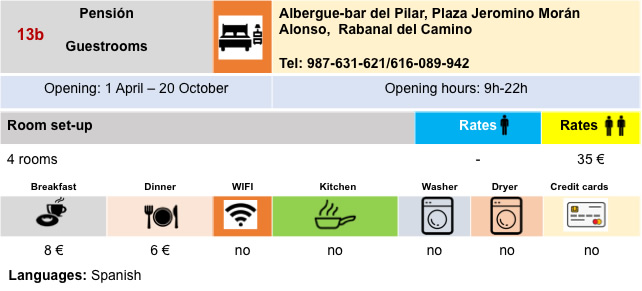

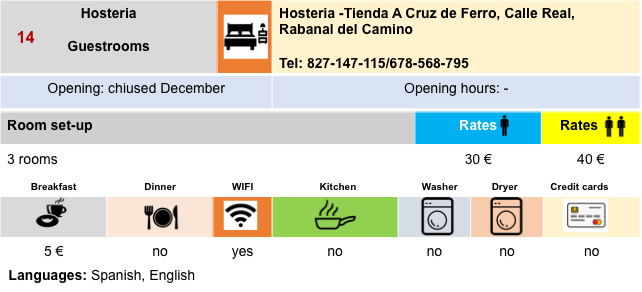

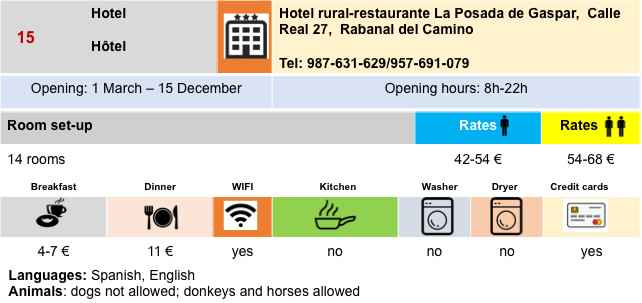

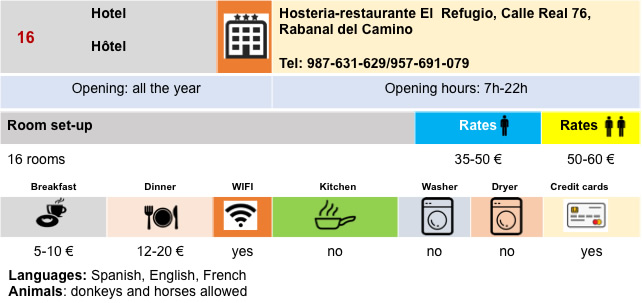

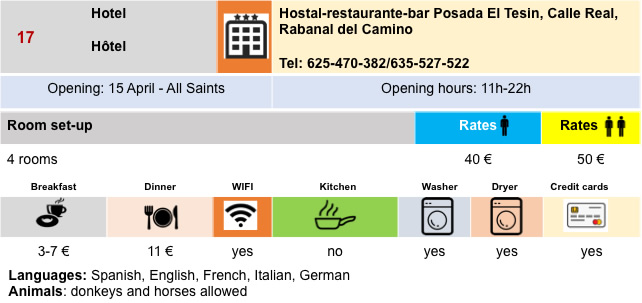

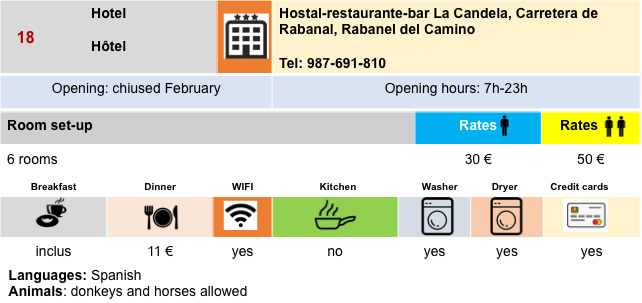

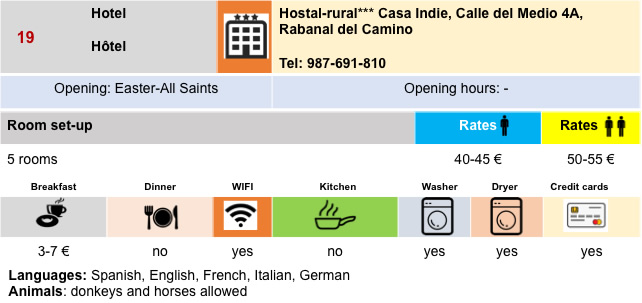

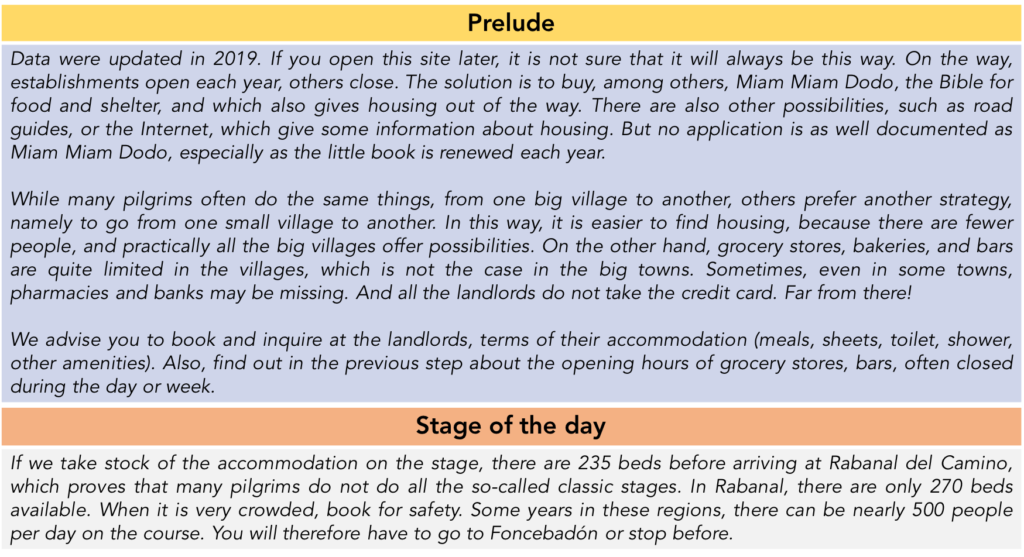

Housing

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 5: From Rabanal del Camino to El Acebo |

|

|

Back to menu |

Today the pathways clearly have priority, as is the norm in Spain. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. Here, they are often real pathways along the roads, as are all the “senda de peregrinos”:

Today the pathways clearly have priority, as is the norm in Spain. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. Here, they are often real pathways along the roads, as are all the “senda de peregrinos”: