Under the gigantic wind turbines

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

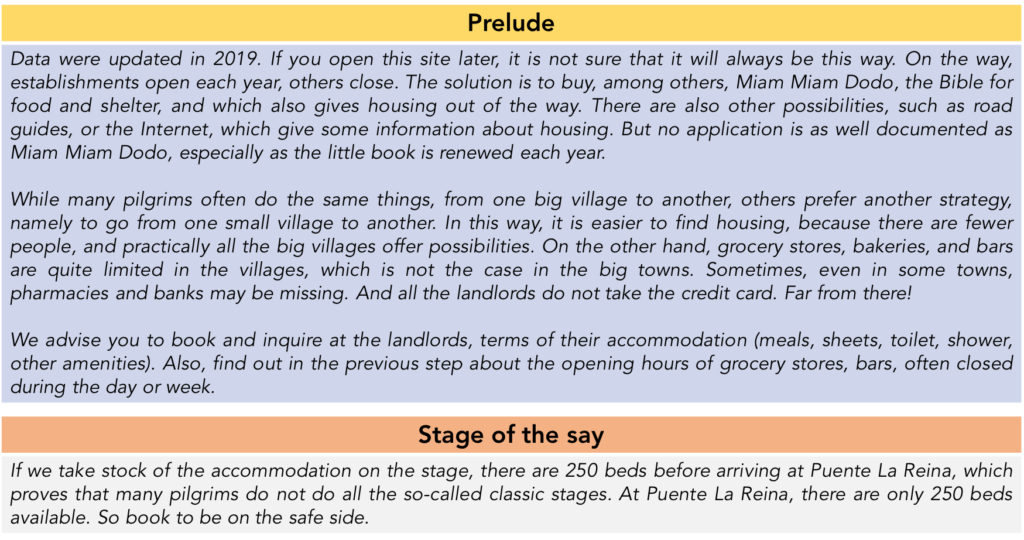

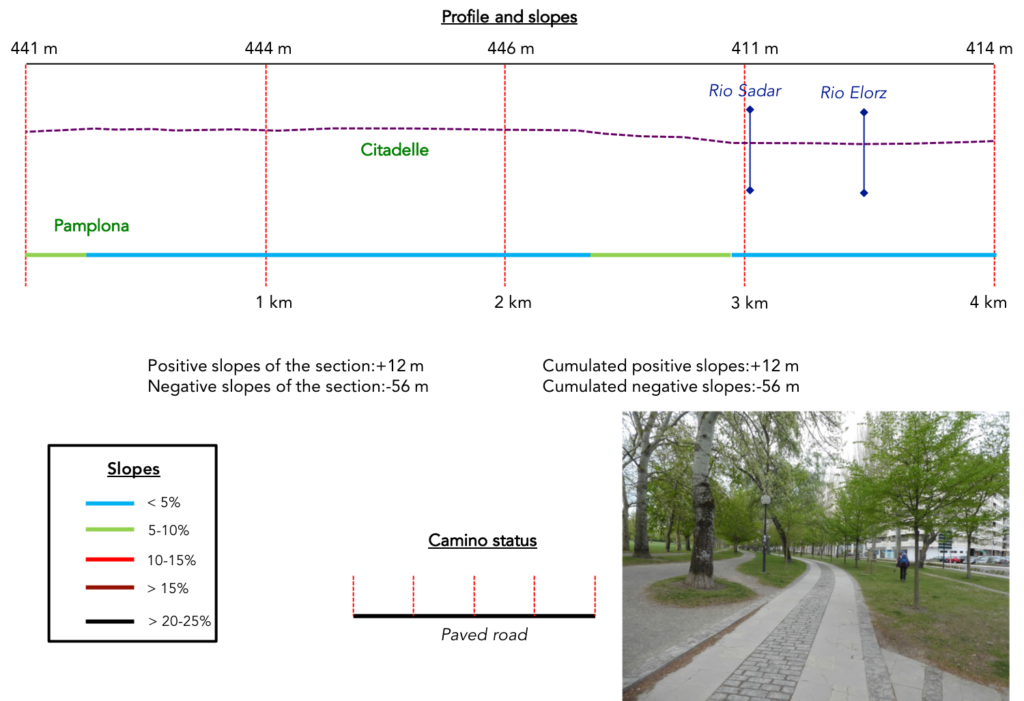

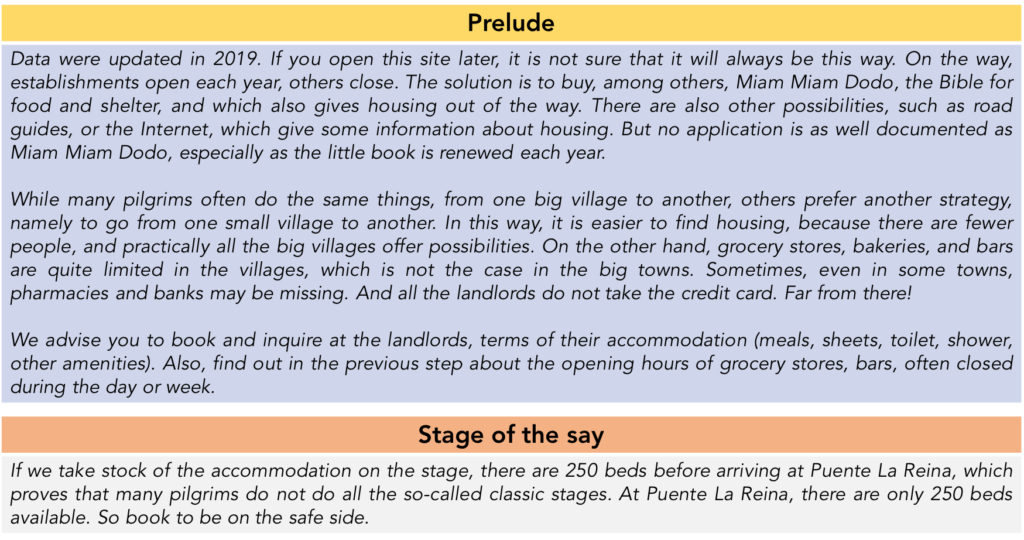

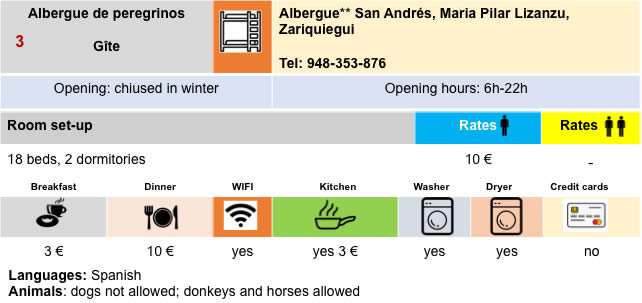

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of theCamino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-pamplona-a-puente-la-reina-gares-par-le-camino-frances-33640432

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

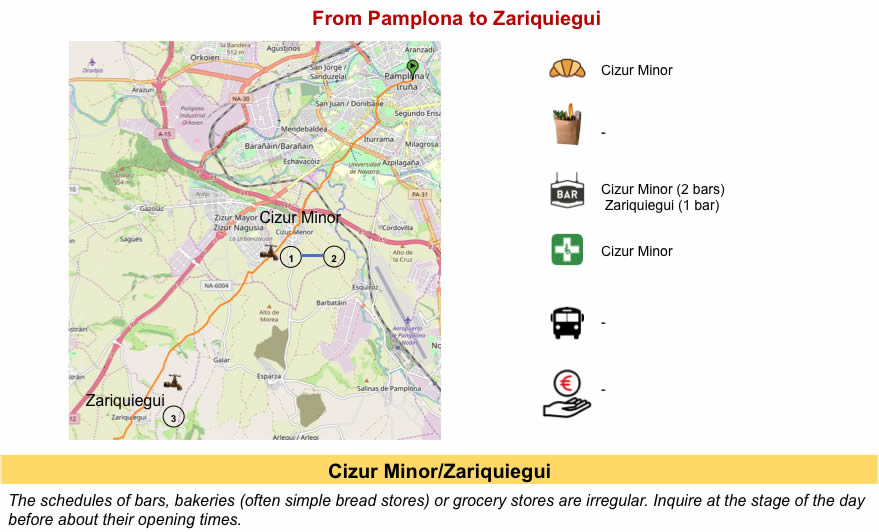

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

You were briefly told the beginnings of the history of Navarre in the previous stage, arriving in Pamplona. So, back with a little more detail, after Charlemagne time, in a region where many powers clashed, including France. In the IXth century, Louis I The Pious, son of Charlemagne, is emperor of the West. He enters into conflict with the people of Navarre, but he is beaten again in Roncesvalles. Pamplona becomes a kingdom, which knows its apogee with Sanche III the Great at the beginning of the XIth century. At this time, the kingdom of Navarre includes almost all the north-east of Spain, and its competitors are Castile and Aragon. Then come years of conflict between Navarre and Aragon for control of the country. Later, France also comes into play. All this is not only a story of wars, but also of marriages, where the regions pass from one sovereign to another. At the end of the XIIIth century, the marriage of Jeanne I of Navarre with Philippe IV temporarily unites the crown of Navarre and that of France. But it does not last long. For two centuries civil wars will succeed here between Navarre, Aragon and France.

It is in the meantime that a considerable king, Charles-Quint, comes into play. Because Spain has not always been Spain. Charles-Quint (1500-1558) controls many territories. Do you want the titles of this potentate? Charles of Habsburg, Dutch prince, was Prince of the Netherlands, Archduke of Austria, King of Castile, Aragon and Naples, King of Spain, Emperor of the Holy Germanic Empire, plus another dozen possessions. At that time, Spain is divided into two kingdoms belonging to Charles-Quint, the kingdom of Castile and the kingdom of Aragon. Navarre is trying to nest between, and with France too. The enemy number one of Charles-Quint is François I, the king of France. Then, Charles V sends his troops for the conquest of Lower Navarre. Henry II and François I are taken prisoners in Pavia. After these episodes, it all boils down to a story of beds and weddings. Henry II escapes and marries the sister of Francois I, then resumes St Jean-Pied-de-Port. To give good weight, François I married the sister of Charles-Quint. How beautiful is the story of kings when everything happens in the alcoves! Then the fate of Navarre is momentarily settled. Charles-Quint abandons the idea of reconquering Lower Navarre. Henry II is now happy with Lower Navarre. Upper Navarre and Pamplona remain Spanish.

But, do not think that we will stop there. Jeanne d’Albret, the daughter of Henri II marries Antoine de Bourbon, a French prince, again creating a risk for Navarre. Then Charles-Quint proclaims his son Phillippe, King of Navarre. It is to this last one, become king later, that one owes the fortresses of Pamplona. On the French side, Antoine de Bourbon and Jeanne d’Albret will give birth to Henry III of Navarre, who will become Henry IV, the founder of the Bourbon dynasty. Henry IV, who calls himself King of France and Navarre, declares war to Spain in 1595. He loses the war and has to sign peace, definitively losing Spanish Navarre, preserving only Lower Navarre and Bearn. However, Louis XIII, son of Henry IV and his successors will always add the title of King of Navarre to that of King of France.

Navarre is now separated into two entities. On the one hand there is Upper Navarre, with a viceroy representing Spain, and on the other, Lower Navarre, French, a group of small valleys of little importance. Then come continuous conflicts between the two countries, which will last for nearly two centuries. In 1700, Charles II, King of Spain, and therefore also of Navarre, dies without children. The Dauphin Louis of France, son of Louis XIV and Marie Therese, sister of Charles II, is, by descent, likely to reunite on his person the kingdoms of France and Spain and also reunify the Kingdom of Navarre. But the Dauphin does not want Spain, reserving for the throne of France, that he will never get, dying before his father Louis XIV. The dolphin gives his rights to his son who will become Philip V of Spain, after a war of succession in Spain. Upper Navarre remains a faithful supporter of Philip V throughout the conflict. To reward this fidelity Philippe V makes them additional favors, by confirming the « fueros », the local privileges. Today we can better understand the different privileges and the relative autonomy of certain regions of Spain. At the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the division of the kingdom of Navarre is final. There will now be two kingdoms of Navarre: the Spanish kingdom of Upper Navarre, and the Kingdom of Navarre in Lower Navarre. And it’s still a paradox. The French and Spanish kings, are of the same family, all from Louis XIV. We will tell you more later on our trip, the quarrels between Navarre and neighboring Castile.

You will be told in Pamplona that the Santiago track is the business of Sancho III the Great, king of Pamplona at the beginning of the XIth century. Streets, squares and « albergue » are named after him. Before him, the road passed from Roncesvalles to Pamplona, then further north to Burgos. But, to better control his kingdom, he deviated a little way south, taking advantage of ancient routes of Roman origin, passing through Puente la Reina, Estella, Logroño, Nájera, Santo Domingo de la Calzada and Burgos. The route was shorter and avoided narrow passages or gorges, facilitating the passage of pilgrims, merchants, and incidentally his armies. You will probably have a little doubt about it, having faced the mountain of Alto del Perdón, the mountain of Pardon. No doubt the Roman road preferred the plain to the high hill and its wind turbines. It does not matter to you! The way to the wind turbines is great. At the end of the day, you will reach the most famous bridge of the way, the Romanesque bridge of Puente la Reina, which according to the historians or the legend, would have been sponsored by Mayor, the wife of the great king.

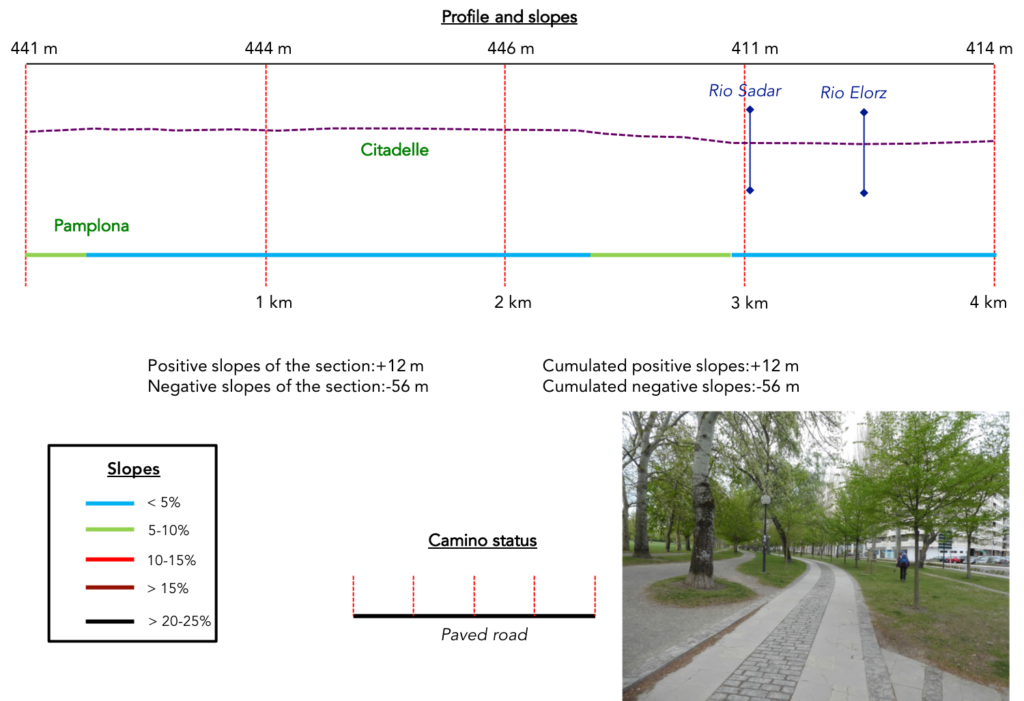

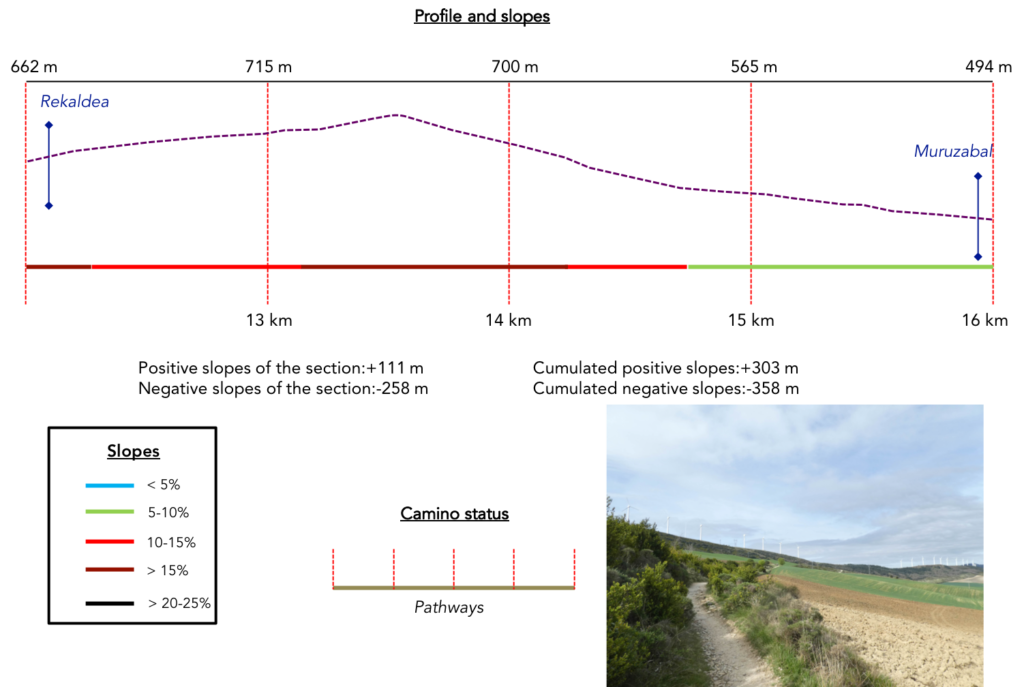

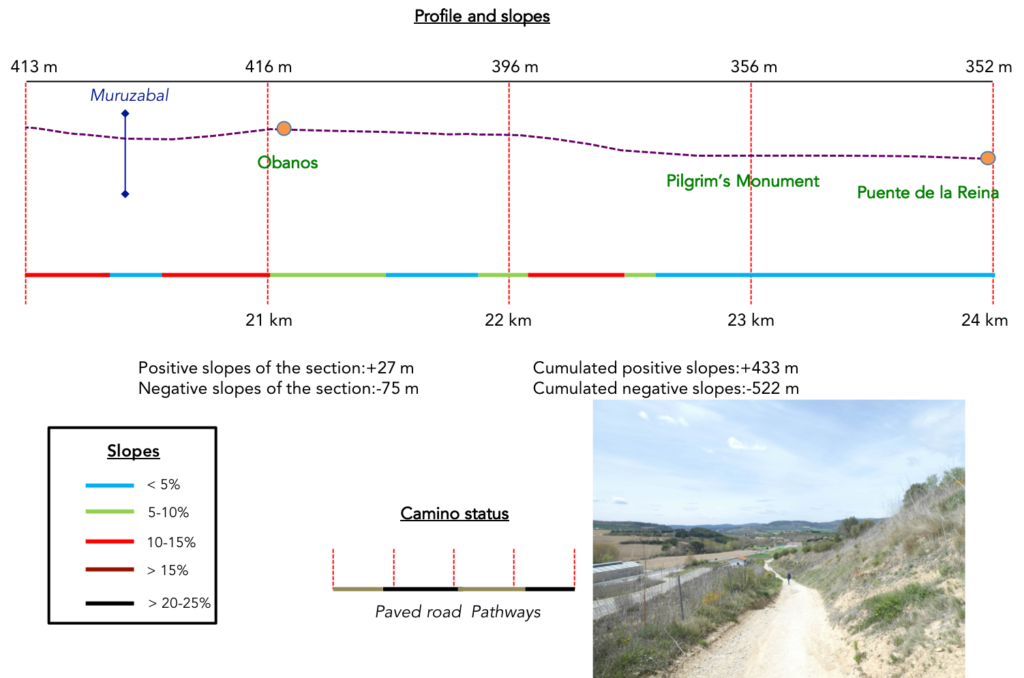

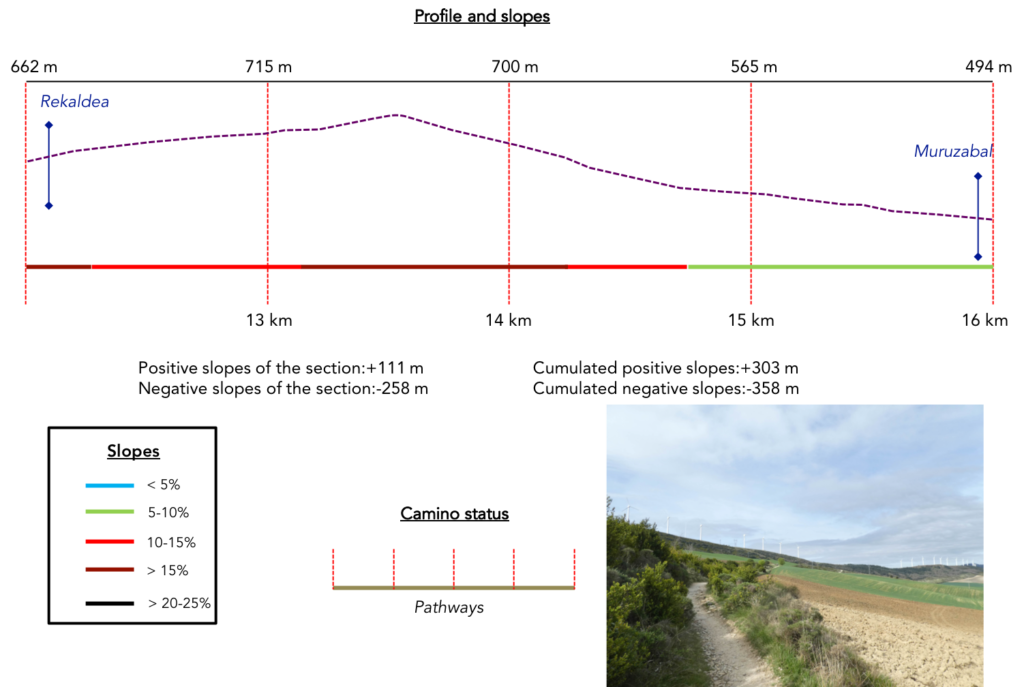

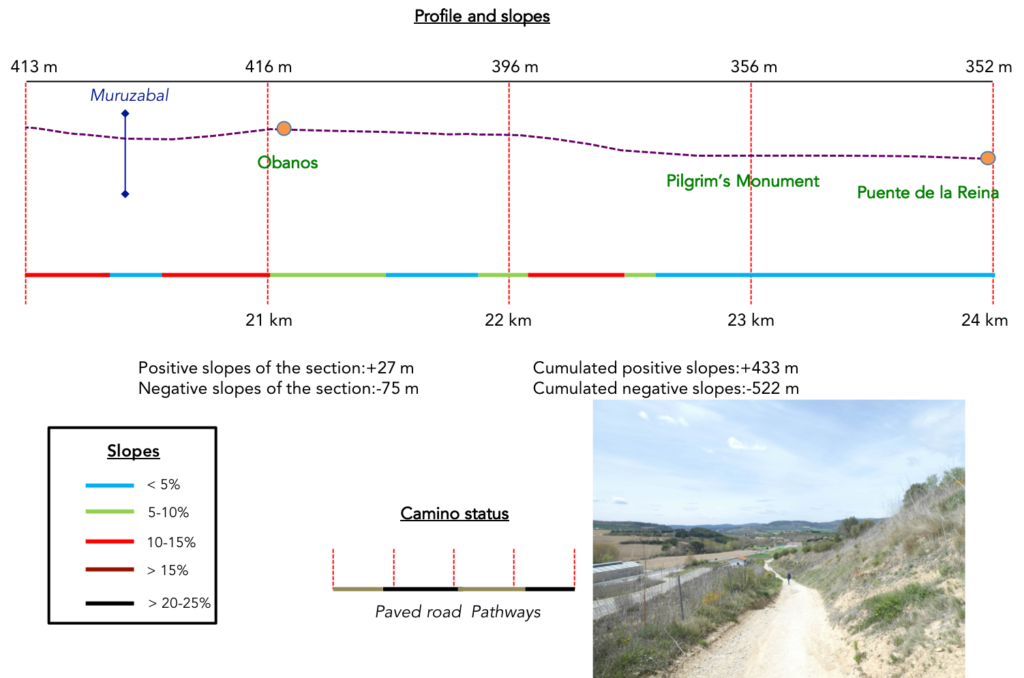

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+433 meters /-522 meters) are quite important for a stage in Spain, which are mostly low. In fact, there is only one difficulty, it is the Alto del Perdón, a long climb towards the wind turbines, but especially a breaking-legs descent in the scree. Everything else is almost a walk.

In this stage, the advantage is to pathways, as is the custom in Spain. Some pathways are paved. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true dirt road, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 9.2 km

- Dirt roads: 15.8 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

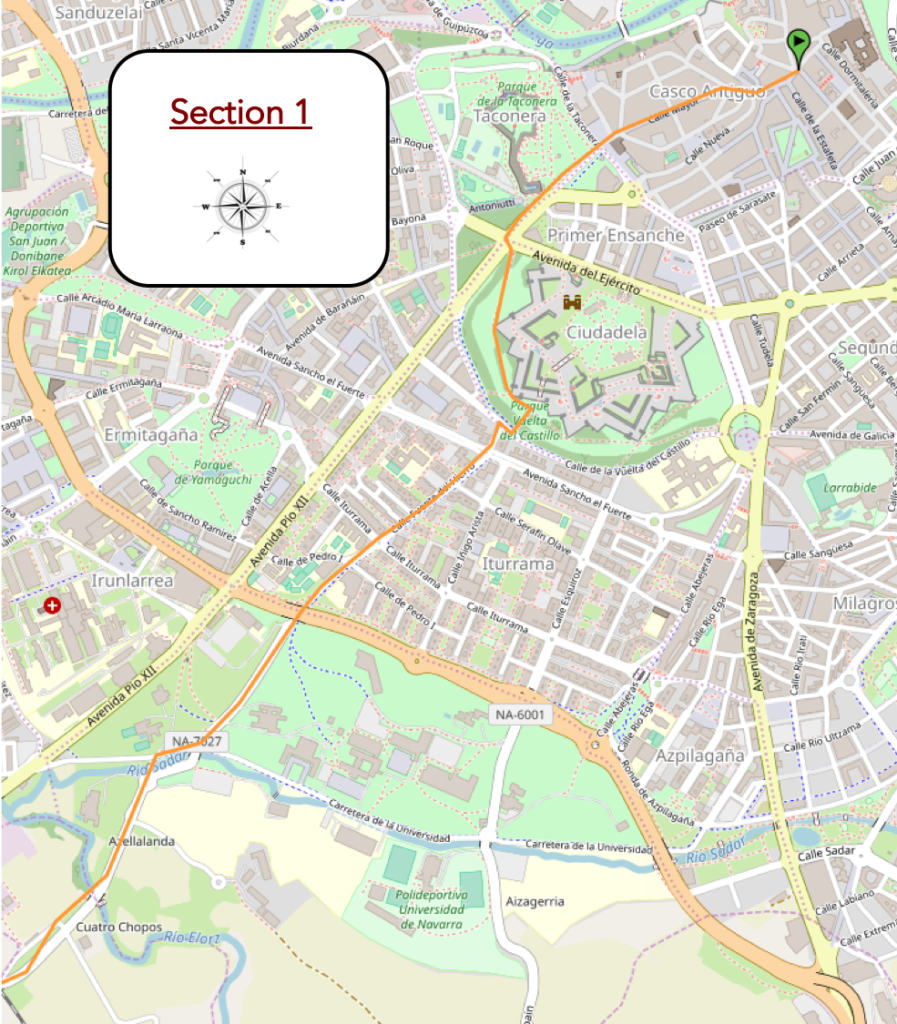

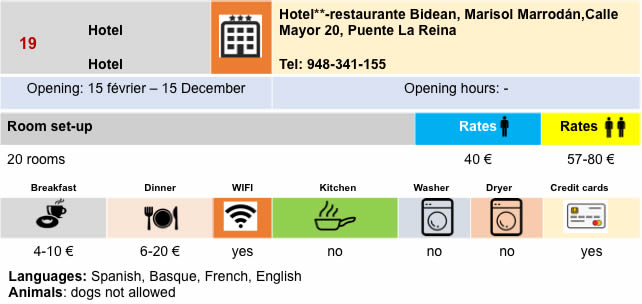

Section 1: Crossing Taconera Park.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| If you are near the Plaza de Los Burgos, in the city center, you have to follow Calle Mayor, deserted in the morning, to reach the Church of San Lorenzo, on the edge of the old town, near the large park of Taconera, where the citadel spreads out. |

|

|

| The Camino then runs along the park, crossing from time to time the walls or gates of the citadel. |

|

|

| The extensive Taconera Park is the lung of the city. |

|

|

| The Camino runs quite far from the surrounding walls, under the tall black poplars. Further on, it leaves the park to run through a more modern part of the city. |

|

|

| On the sidewalk, it heads past buildings toward a nearby roundabout on the outskirts of town. |

|

|

| After the roundabout, the Camino leaves the city, passing under the national road that bypasses the city. |

|

|

| It then crosses a small park, where the University of Navarre and a “credencial” accreditation center are located. They do not joke with the passports of Compostela in Spain. It is a real institution. |

|

|

| Further on, under chestnut trees and poplars, the route leaves Pamplona definitively, passing over an old stone bridge thrown over the Rio Sadar. |

|

|

| A little further, the Camino crosses another river, the Rio Elorz. Rivers and streams are numerous in northern Spain. |

|

|

| Beyond the exit of Pamplona, the Camino follows the road on a strip of tarmac. For people who prefer dirt or grass, they can also go that route. People have gotten so used to walking on tarmac that they walk on tarmac, for the vast majority. Shortly after, the road passes over the railway line, where the TGV passes through northern Spain to Barcelona. |

|

|

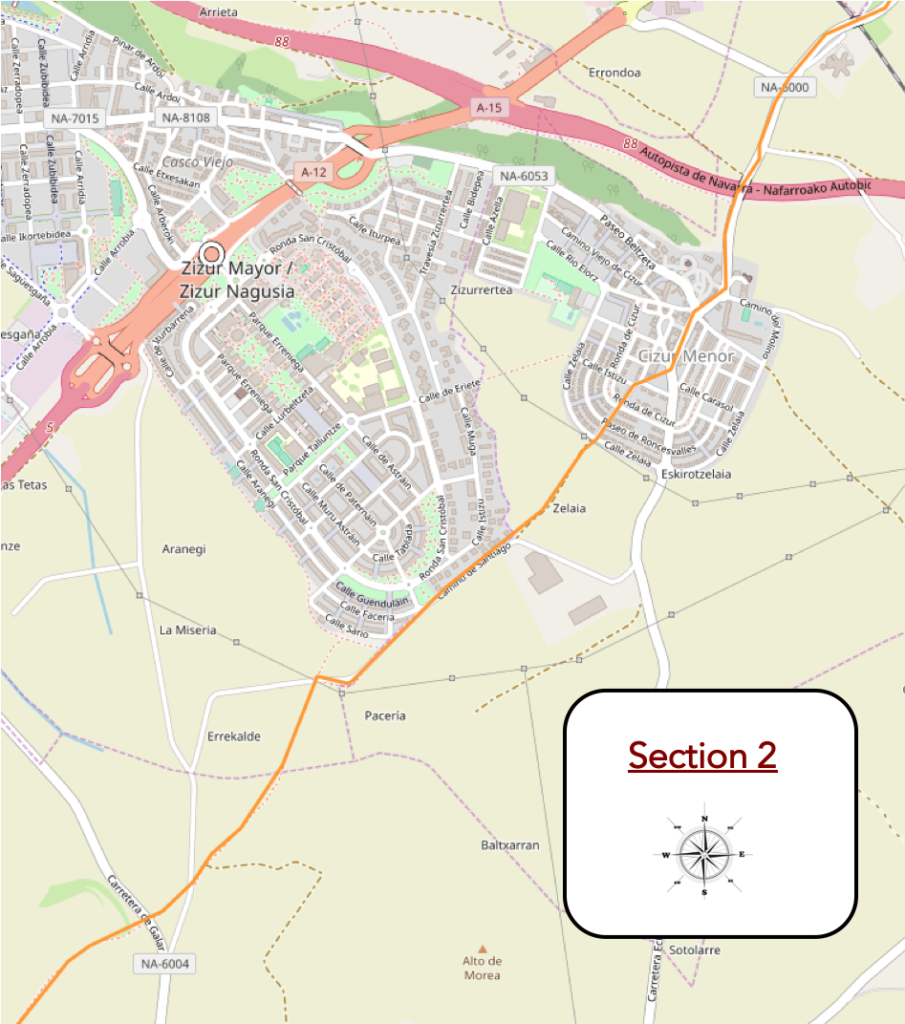

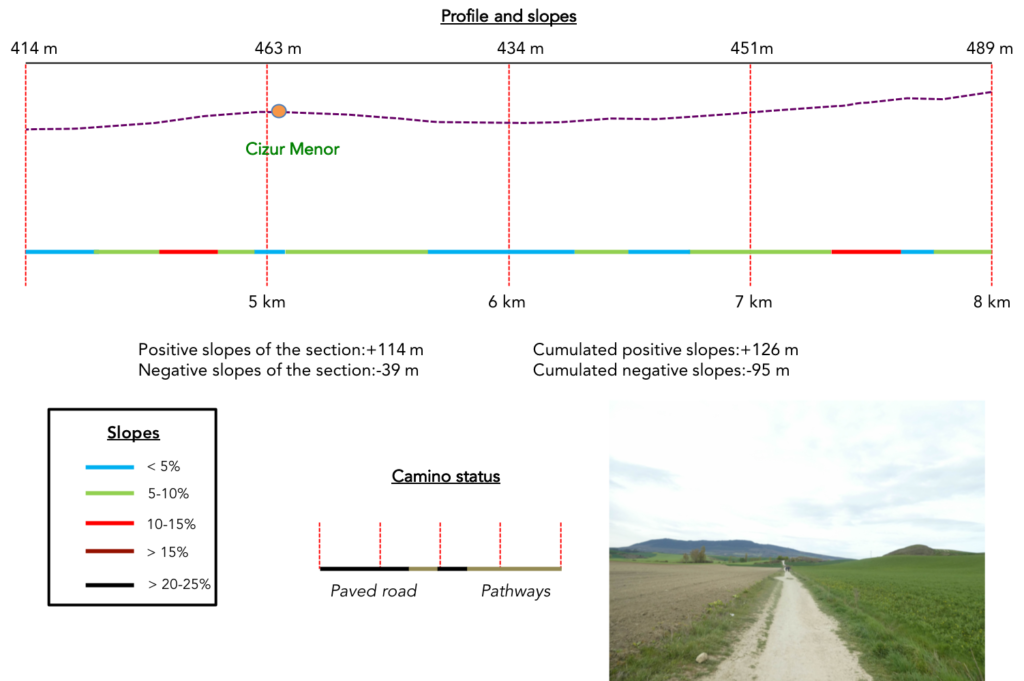

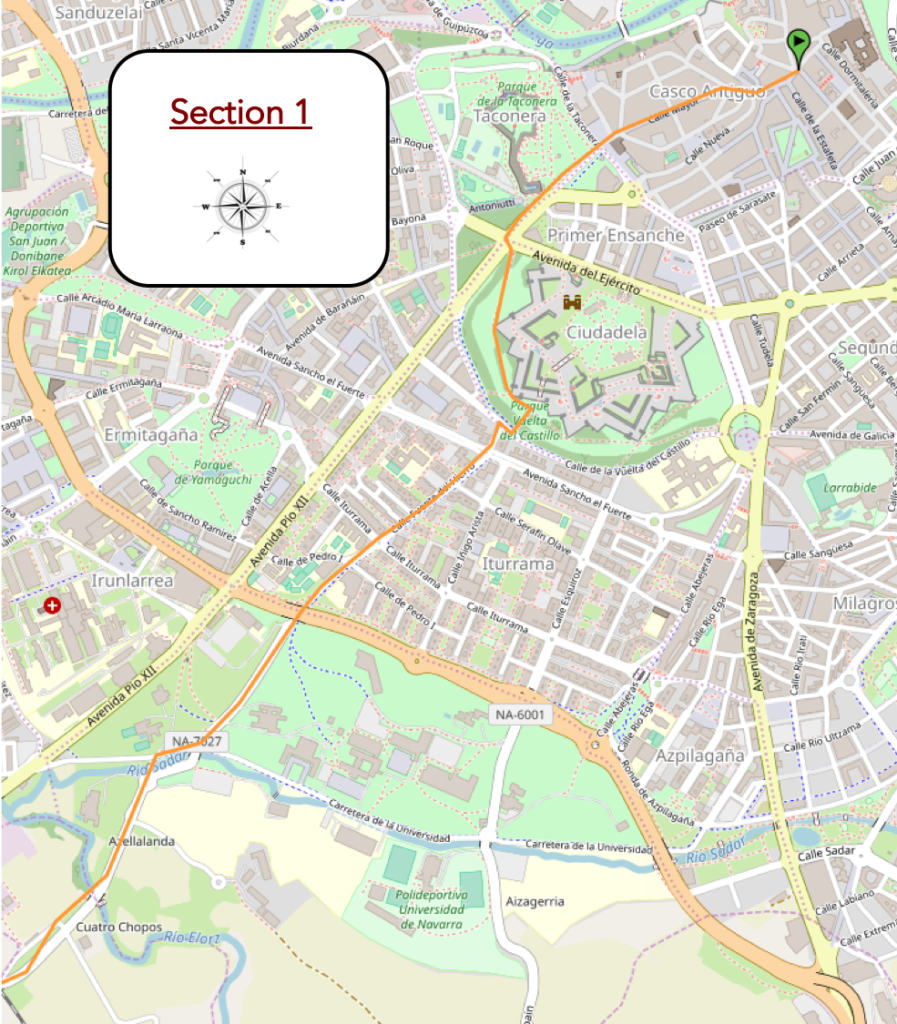

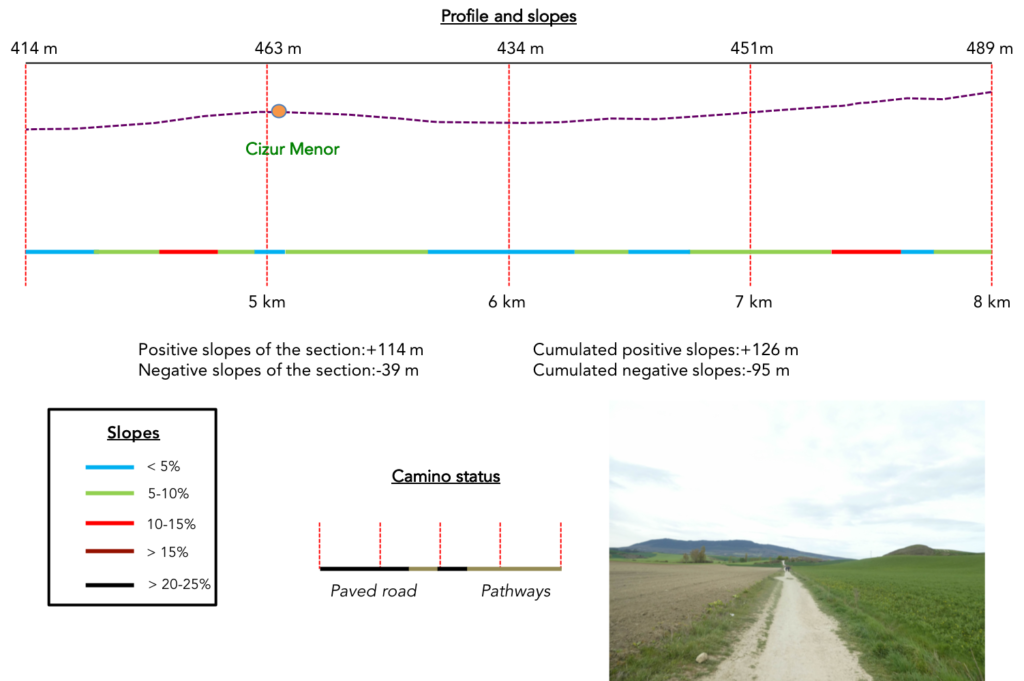

Section 2: Climbing progressively to Alto del Perdón.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, uphill fairly light, sometimes with a little more slope, but rarely.

| The Camino then climbs quite gently on a sidewalk towards the village of Cizur Menor, in the middle of rapeseed fields. |

|

|

| Soon, it runs over the Navarre highway, where the traffic does not seem overflowing. But it’s morning and today is Sunday. |

|

|

| Then, the slope becomes more pronounced under the large black poplars, before the road arrives at Cizur Menor. |

|

|

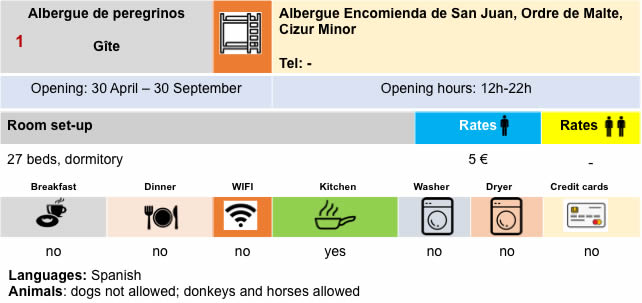

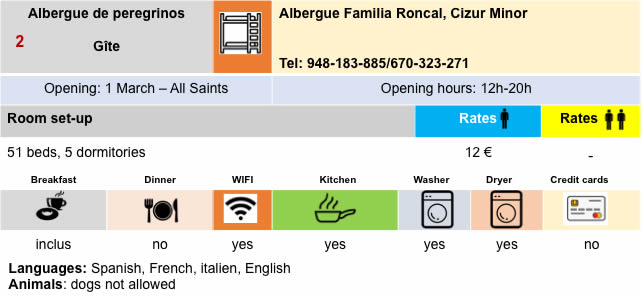

The Hospitallers of the Order of St John of Jerusalem had a commandery in the XIIth century, of which only the church hidden in the village remains.

| The Koreans take the first break of the day. Here, the temperature is cool, at 10 degrees. This will be the usual temperature for more than 15 days. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino slopes down beyond the village towards Cizur Mayor, on the sidewalk. |

|

|

| Further down, the dirt finally makes its appearance. “Finally, the way!” will sigh, in very large majority, the pilgrims. |

|

|

| But, here it is of short duration and The Camino then runs along the bottom of the village on a small asphalt road. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino then follows on a strip of land a road used by the farmers for their crops of wheat and rapeseed. |

|

|

You realize quite quickly that the pathway will slope up the hill, you just have to see in the distance the clusters of pilgrims on the track.

| Soon, there will only be the pathway that undulates in the countryside. Here it begins to be the Spain of the north, with its immense green fields in spring, scorched the rest of the year by the sun. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the slope is a little more marked, but not exceeding 10%. Sometimes the slabs replace the dirt, probably when the pathway runs through more flood-prone land. Long live Europe! This modification of the track is the fact of European funds. Rapeseed is being transplanted everywhere on the slopes. |

|

|

Turning around, the large village of Cizur Mayor and, in the background, the plain of Pamplona disappear behind the cereal fields.

| There are crowds on the way, pilgrims on foot for the most part, but also on bicycles, and many local hikers who come to try out the Camino de Santiago during the weekends. The pathway crosses a small road which joins a village on a hill. When you look at the nature of the soil, you can see that the local farmers don’t waste a lot of time de-stoning their fields. |

|

|

| Here, wheat and barley are grown, as in the whole Meseta. The plowed fields are probably waiting for the corn to be planted. But in this region, farmers also plant a lot of rapeseed, which is not the rule in Spain. |

|

|

| A little further on, the pathway approaches an undergrowth and the slope becomes steeper. |

|

|

Up on the hill, a village feels all alone in the world.

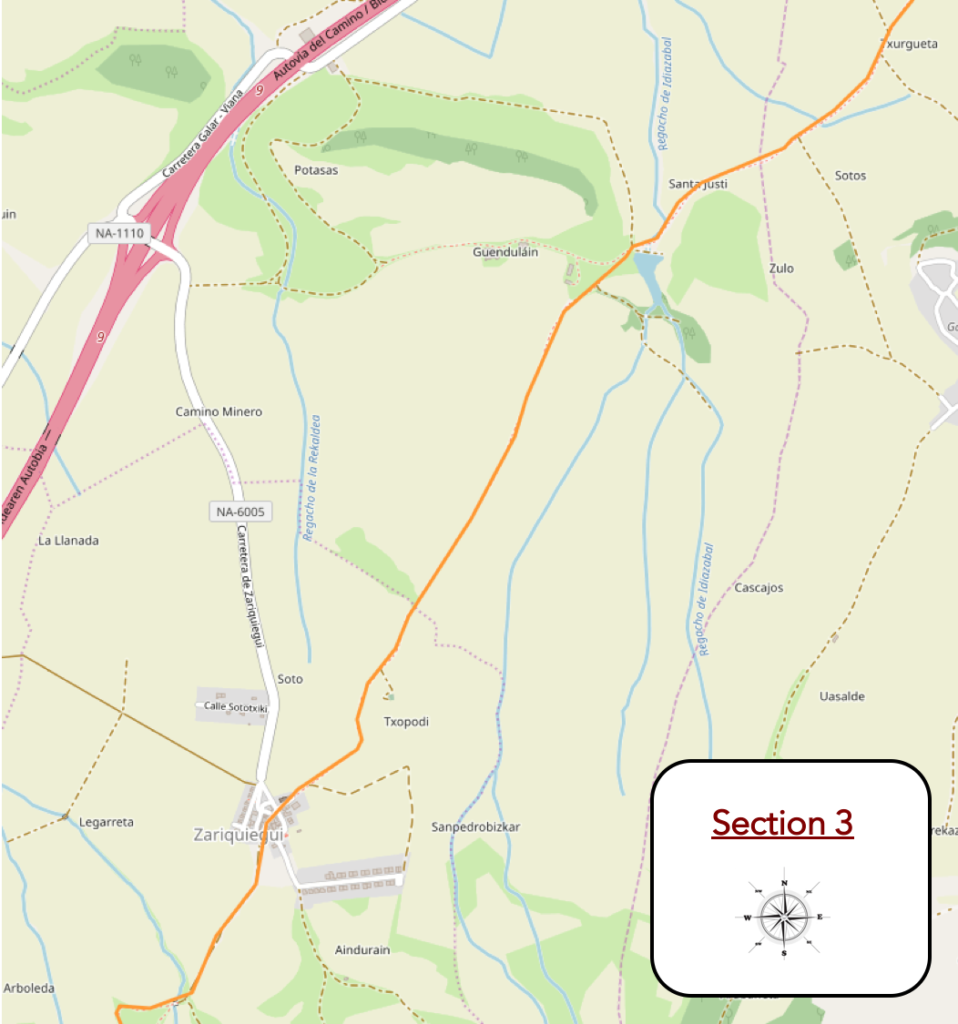

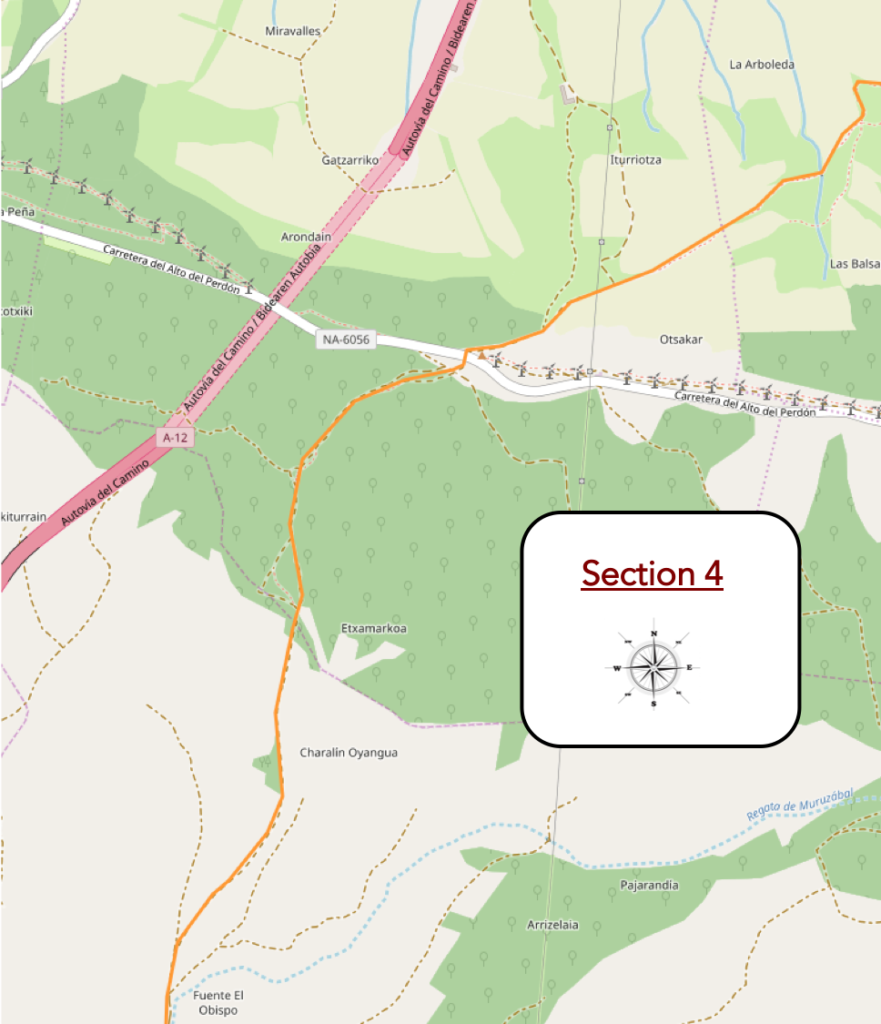

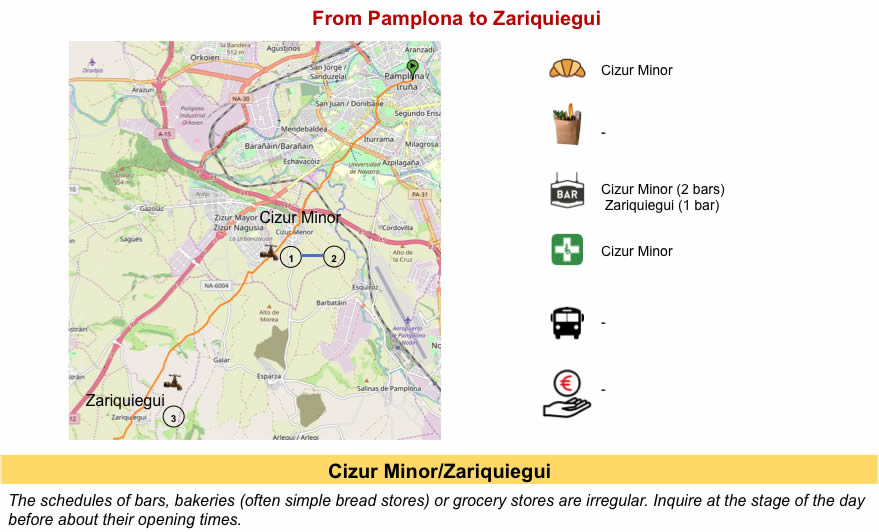

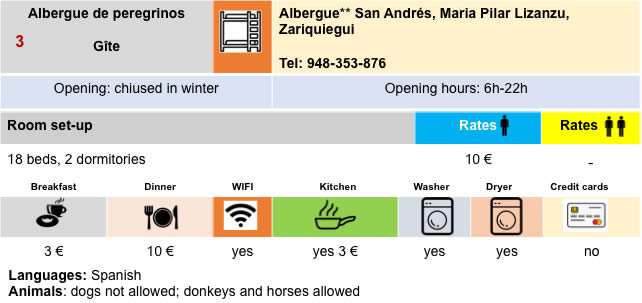

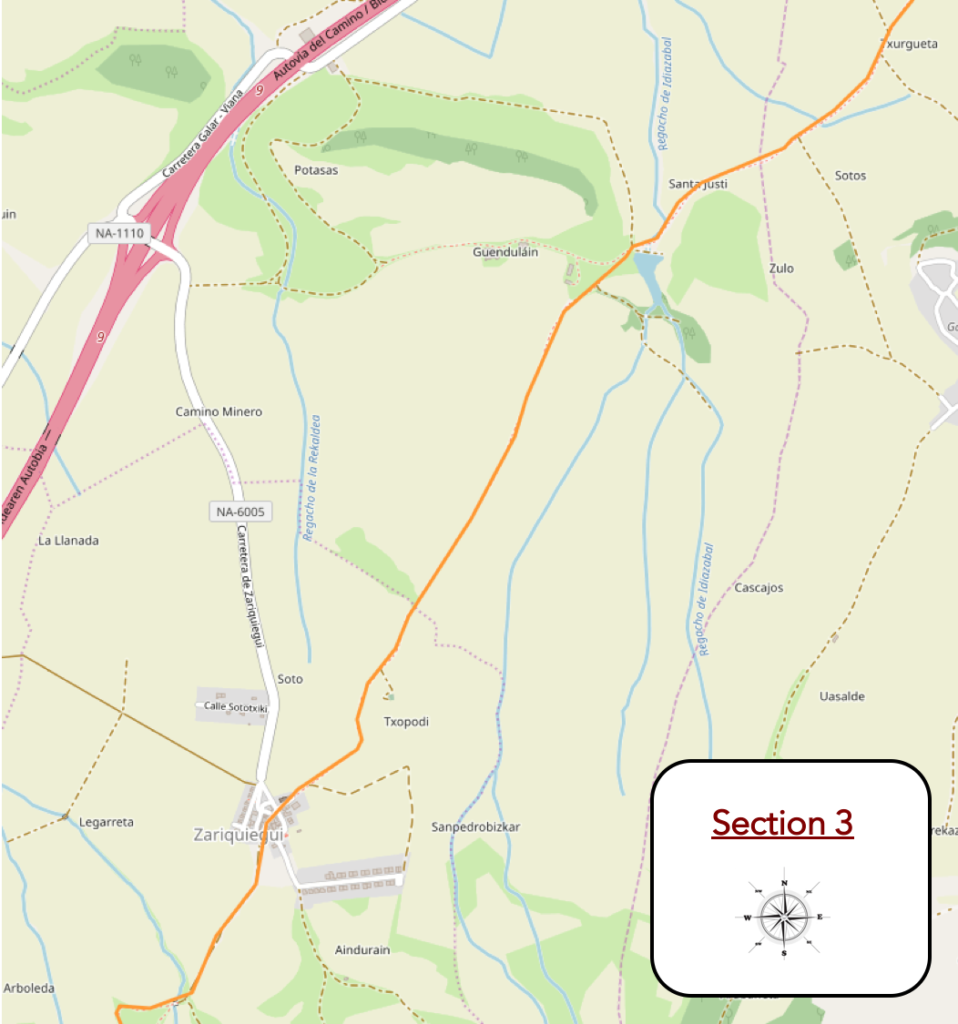

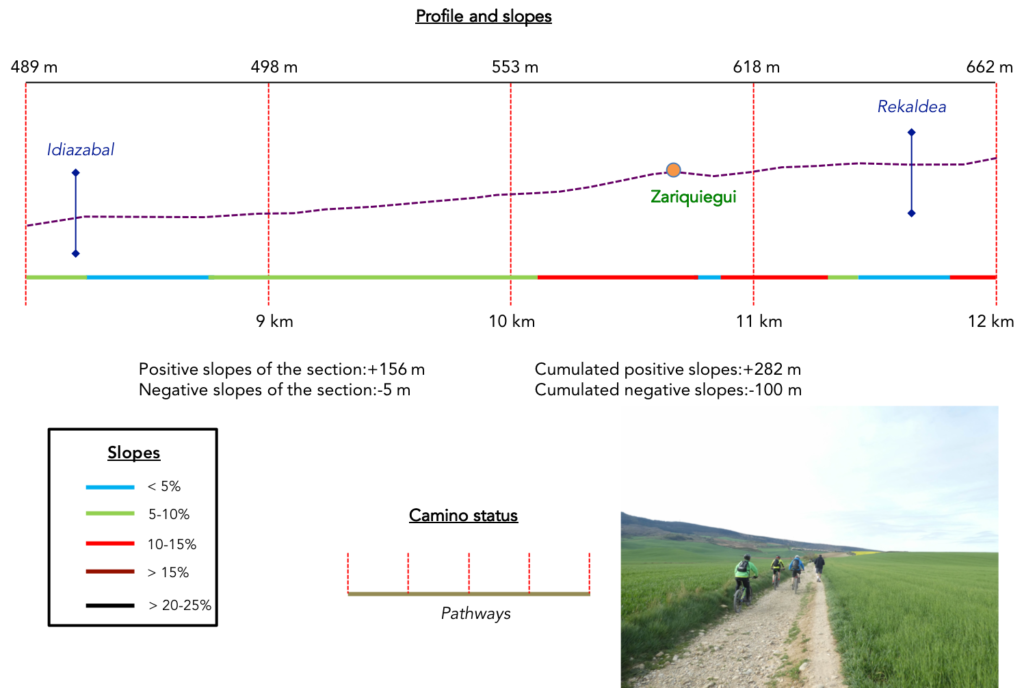

Section 3: Zariquiegi or the pilgrims’ break.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: first easy part, then it gets complicated, between 10% and 15% around Zariquiegui.

| The slope remains marked in the scrub until it reaches the Idiazabal stream under the black poplars. |

|

|

| Just above, the pathway gets at a place called Guendulain, 4.3 kilometers to the Alto del Perdón, the Pass where the Camino will find further. Here, a family from Oregon with children. In America, you can not send your children to school and educate them yourself. To see the face of the little boy, we will not say that he will keep an imperishable memory of his trip to Spain. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope softens again in the immense fields of cereals, on a slightly rockier pathway. |

|

|

| Up there, in front of you is the village of Zariquiegui. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway begins to climb a little stronger. In front of you, the line of pilgrims thins out and sometimes gets lost in the bends. |

|

|

| It is when the slope is steeper that you see that the cyclists hardly climb faster than you. Up there, above the village, the barrier of wind turbines, which can be seen from the bottom of the valley, is becoming more and more visible. |

|

|

| Another little effort at nearly 15% incline, and the Camino lands at Zariquiegui. It’s always fun to see how frenziedly pilgrims pounce on tortillas and other Spanish delicacies, as if they’ve been fasting for a week. |

|

|

This high-perched village was also held by the Hospitallers of St Jean who built here in the 12th century a massive church, dedicated to St Andres, with a square tower. The church is closed, but the restaurant is open.

| Beyond the village, a wide dirt road descends until it crosses the Rekaldea stream, almost invisible under the brushwood. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway gradually leaves the crops and enters a kind of maquis where only boxwood, broom and brambles grow. Here, the pathway begins to climb toughly, at nearly 15% gradient. |

|

|

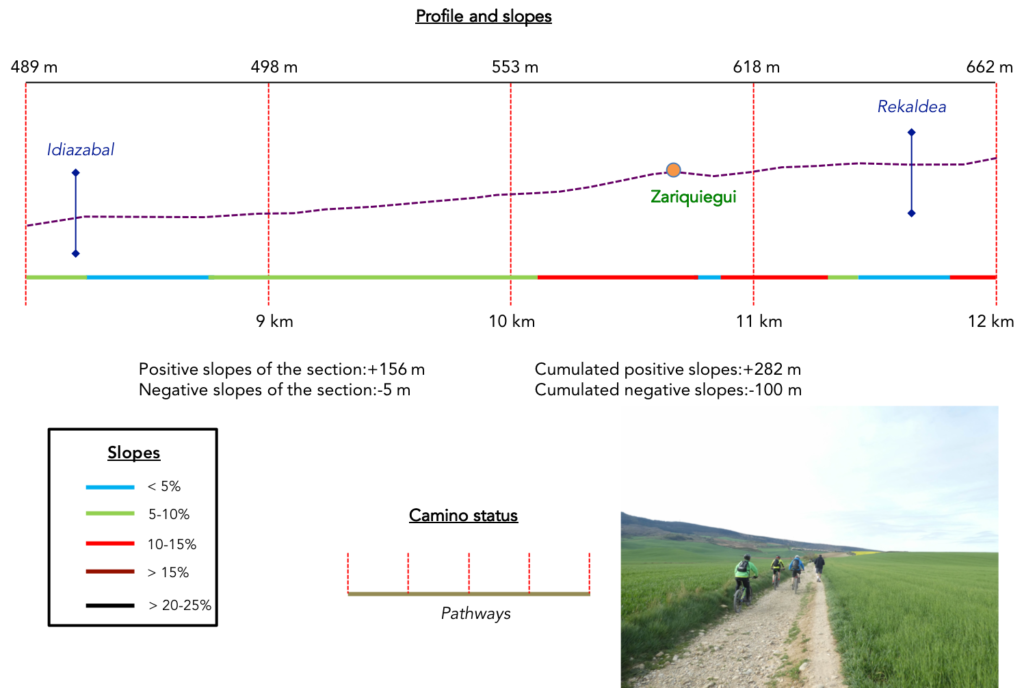

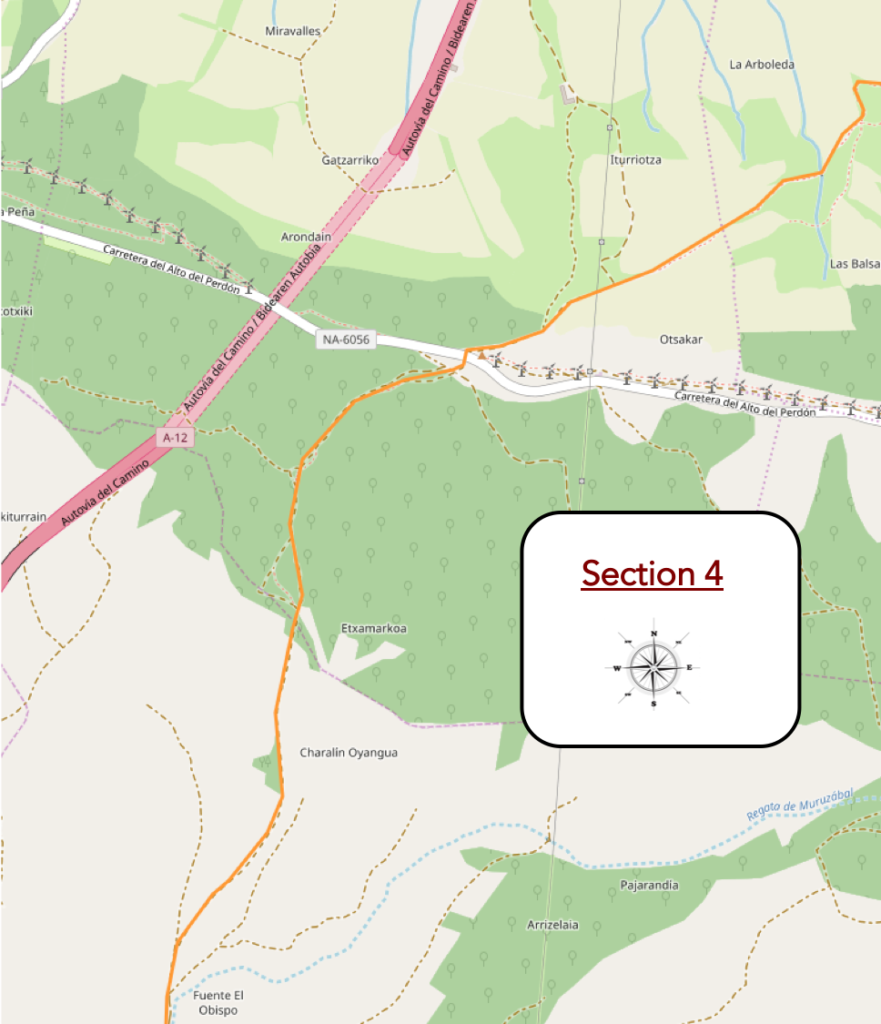

Section 4: Up there at Alto del Perdón.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: breaking-leg course, at almost 20% of slope often. It is especially the descent into the scree which is demanding.

On a small ridge, you can see how far you have come from Pamplona, right there, at the bottom of the plain.

| The small pathway will constantly climb, up to 20% slope, in the broom and boxwood. In season, pilgrims must suffer here under the heat wave. You can see the wind turbines better and better on the ridge line, but for the moment you cannot hear them yet. |

|

|

| This approach has a bit of a troubling edge to it. The wind turbines, sometimes you have the feeling of touching them with your fingers, then at a bend in the road, they disappear again, like mirages in the deserts. |

|

|

|

|

| Further up, in a fairly regular but bearable roar here, the blades of the wind turbines cut through the air, a hundred meters above the scrub. The west wind is blowing vigorously and the turbines are running at full speed. These enormous machines raised towards the sky to capture the energy of the wind do not murmur, do not sing lullabies. They moan instead. They are like the teeth in the jaws of sharks, ready to engulf anything that comes their way, and not just the wind.

Voices are rising more and more to stop the massacre of migratory birds, which die by the thousands each year. People go so far as to install radars to stop the turbines when birds pass, crushed by these huge jaws. In Spain, more than 20,000 wind turbines are arranged on the ridges, like so many wind corridors. Here, for some, they in no way disturb the aesthetics of the mountain. They are no less ugly than the hideous cable cars that climb the Alps to attack mountains and glaciers. But, in the plain, will you tell me? Recently a big controversy has developed in France about the Nozay wind farm. The cows are getting sick, dying in greater numbers, even refusing to be milked, leering at the wind turbines. Nearby humans complain of sleep disturbances. So, wind turbines, just wind, who knows? Case to follow, as they say in the good gazettes, scientific or otherwise.

In any case, here, where life is derisory, they must not disturb the sleep of pilgrims, but perhaps that of marmots. |

|

|

| Just above, the pathway arrives on the angular stones at the Alto del Perdón, the mountain of Perdón. |

|

|

| Here, the Hospitallers watched over the pass and a hermitage offered hospitality. Today, there remains only a metal sculpture erected in 1996, in memory of the pilgrims. From here the view of Navarre is spectacular. There are of course street vendors who have replaced the knights of yesteryear, with the credit card. If you ever drive down the highway that descends from the north towards Burgos, you will see these monstrous rows of wind turbines. They are so imposing that they are drawn on topographic maps. The highway passes under the mountain. |

|

|

| The pathway then plunges towards the plain. Below are small hills. You also see the highway coming back towards the light. But you are far from there. The descent is bad, on hideous stones which roll under the foot, because such is their fate when they are laid out on a severe slope. |

|

|

| In this arid universe grow small holm oaks, which must be undemanding to survive. Here, these trees are called encinas. Holm oaks (Quercus Ilex) are not made like traditional oaks. They look like oaks, yes, but their leaves are not twisted, multi-lobed, but either smooth or slightly toothed, a bit like holly leaves. Here, you find these two species. |

|

|

| At one point, you will be offered to follow either the pathway for cyclists or the one for pedestrians. But, rest assured, it’s the same song, the same nightmare for some. We even came across a Korean pilgrim here walking backwards. We have heard no more from her. |

|

|

Here, there is no shortage of building small cairns.

| Towards the bottom of the descent, the slope decreases, but not the density of stones. |

|

|

| However, all good things come to an end. Then, the legged TGVs overtake you and slip through your fingers. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway then becomes easy on land that is almost sand. Then, cereal fields and some meadows reappear. |

|

|

| It is often a slight descent, sometimes a little more marked, with here and there a clump of holm oaks. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway reaches the Muruzabal stream, hidden in the wild grass under the black poplars. |

|

|

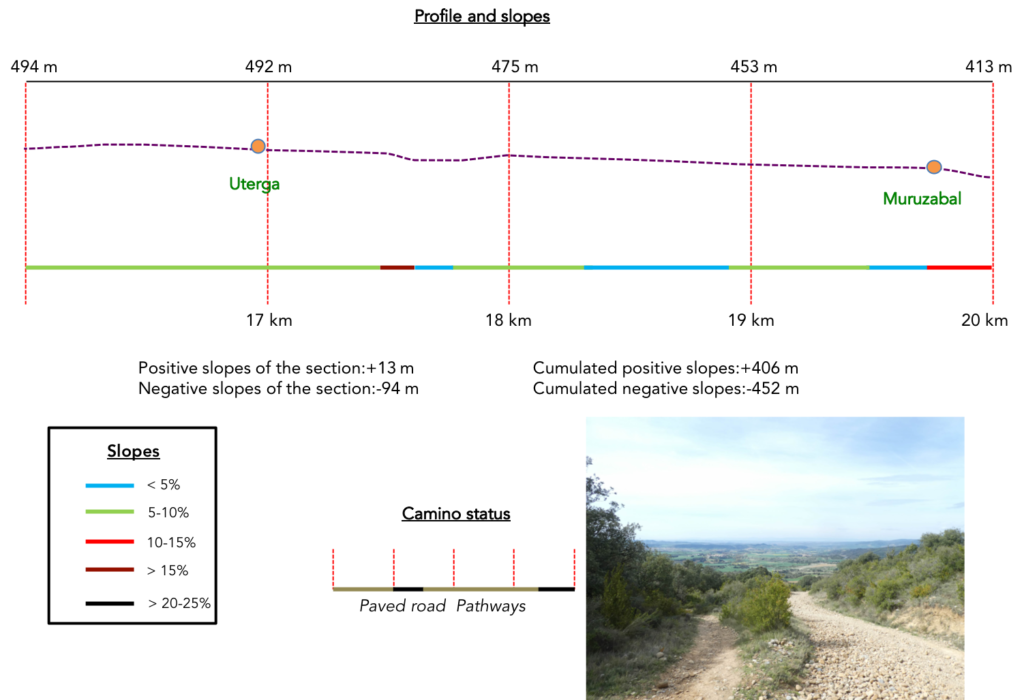

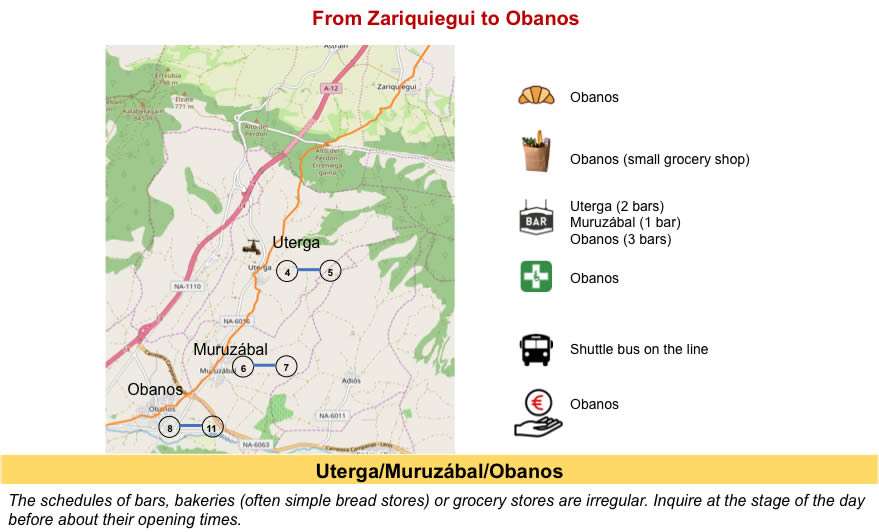

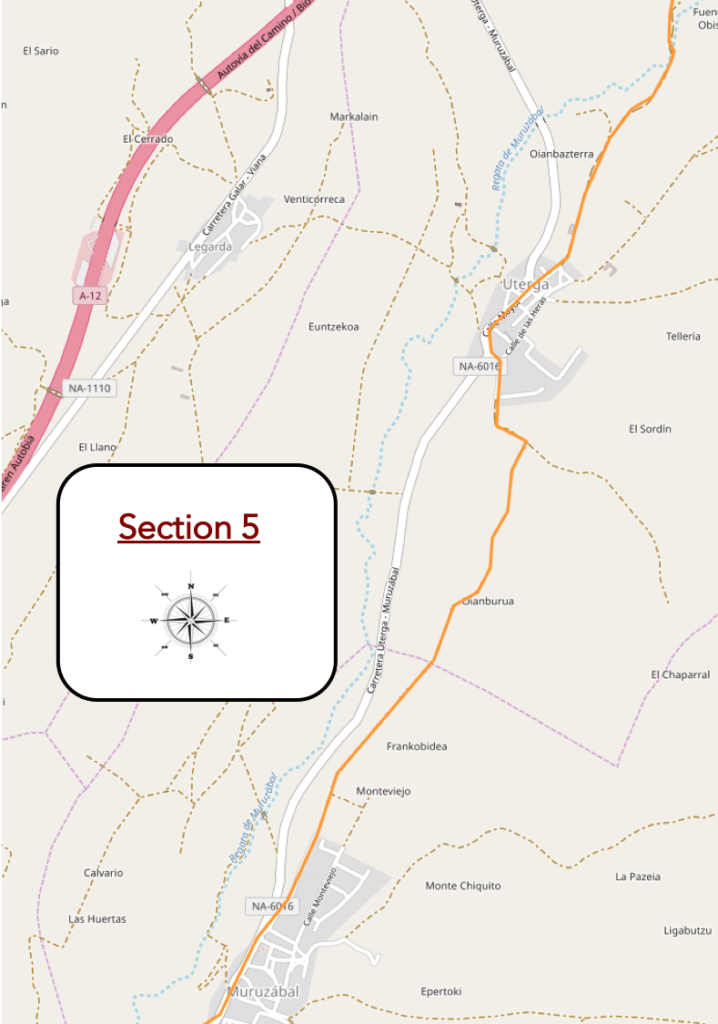

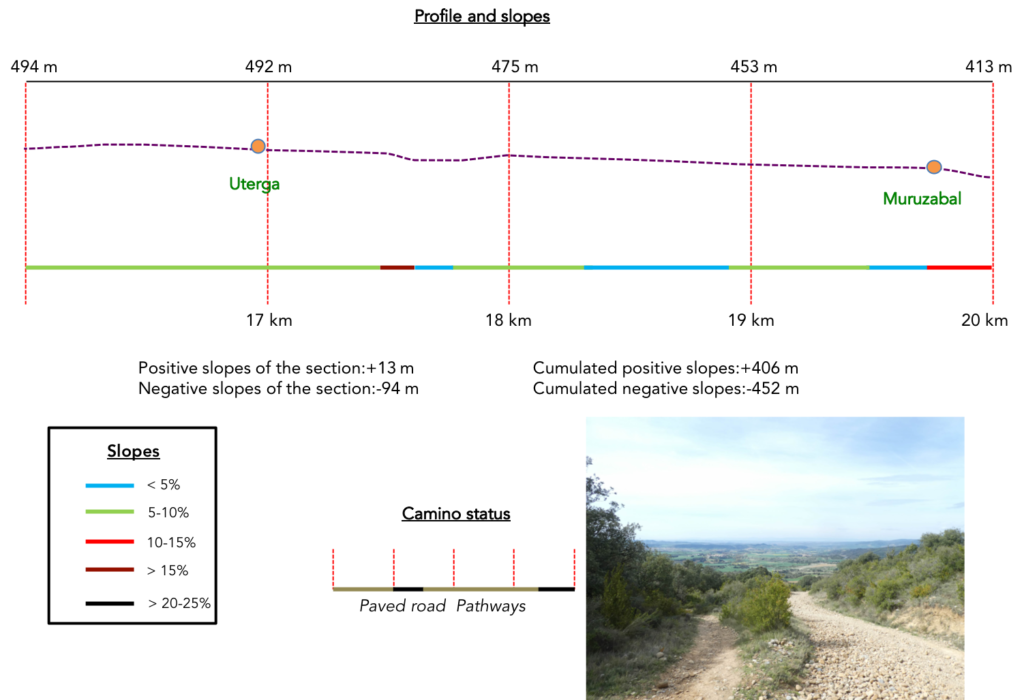

Section 5: Unimportant undulations.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without difficulty, in light descent.

| Beyond the stream, the pathway slopes up a little between holm oaks and large black poplars. |

|

|

| It heads to a statue of the Virgin erected under the large oak trees. |

|

|

Here, you can already get an idea of what the Meseta will be like further on, the green paradise of cereal fields in spring.

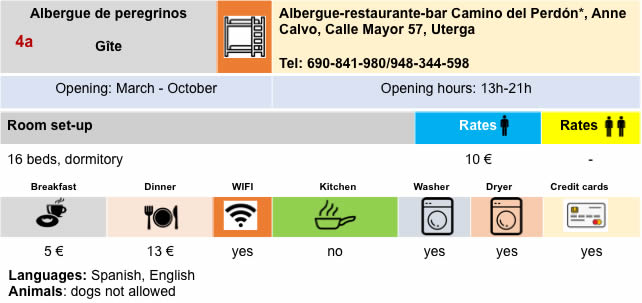

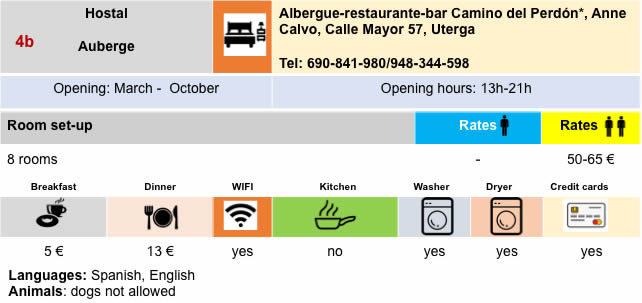

| A little further, the pathway arrives in Uterga. |

|

|

| It is Palm Sunday, and the whole village is gathered near the church, palms in hand. There is still a fervor intact in Spain, at least in the countryside, where young and old people take part in religious ceremonies. |

|

|

| There was a time, very distant now, when pilgrims would have joined the procession. Today, the majority of them are content to take a break at the “albergue”. |

|

|

| A road leaves the village, quickly replaced by a stony pathway. In front of you, you can see the bell tower of Muruzabal in the distance. |

|

|

| The pathway twists a little in the brush hedges and small poplars. |

|

|

| Further on, along the hedges, the pathway undulates for a long time and progresses in the fields of cereals. |

|

|

| The pathway approaches the village. Here appear almond trees, with fruits already present. |

|

|

| Under the almond trees, the pathway arrives in Muruzabal. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino crosses the village on the road, towards the massive church. |

|

|

Section 6: Rough lands towards Puente La Reina.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: a small climb to Olbanos, then downhill sometimes marked, but nothing of consequence.

| Muruzabal, although it has a disproportionate church, is not a big village. |

|

|

| At the exit, the Camino starts again on a dirt road along the brambles, in the rapeseed fields. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the fairly steep descent, the pathway crosses the Murazabal stream, passes under a regional road, and climbs up an equally steep pathway towards the village of Obanos. |

|

|

| The climb is supported on concrete slabs. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the Camino crosses the first part of the village, quite common. |

|

|

| When you cross the second part of this village, you will have the feeling of seeing old stones. But this is not the case. The Church of San Juan Bautista dates from the beginning of the XXth century, rebuilt in a Gothic style on an old church which was falling into ruins. |

|

|

| However, there is still an almost medieval atmosphere here, with “Gothic” buildings. Near the plaza de los Fueros there is even a triumphal arch, also from the 20th century. Nearby, padel is practiced, a racket sport derived from tennis, surrounded by walls and fences. |

|

|

| Just outside the village, the Camino crosses the San Salvador hermitage. It is said that it is here that the two routes of the Spanish track met, on the one hand the Camino Navarro coming from Roncesvalles, and the Camino Aragones, coming from the Somport Pass. It is the last way of Compostelle which comes from the east and the north of Europe. |

|

|

Now, the tracks can travel together to cross the Arga River in Puente la Reina.

| Quite quickly, the Camino returns to dirt. Northern Spain is said to be covered in poppies in spring. For our part, we have seen very few. Did we go too early or too late? On the other hand, rapeseed reseeds everywhere on the slopes. |

|

|

| The pathway slopes down here, sometimes on a slightly steeper slope towards the national NA-6064 road, which runs in the plain. Here grow a few vines and some fruit trees, very rare in Navarre. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway joins the national road. |

|

|

| It crosses the road to run among the market gardeners. |

|

|

| In the past, the track crossed the other side of the river and arrived at the center of the village of Puente la Reina. Today, it gets at the entrance of the village, near a large hotel complex with hotel and “albergue”. It is almost always so. “First come, first served”. There are other “albergues” in the town, but this one is taken over. On the square, a modern statue of the pilgrim apostle (1965) is erected. It symbolizes the union of the Navarro and Aragonese tracks, with the inscription mentioning “Aqui, los caminos se hacen uno” (from here there is only one track). |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino follows the national road to arrive at the entrance of the old town, at the level of a pilgrims’ inn. |

|

|

Section 7: A visit to Puente La Reina.

| Puente la Reina (2,700 inhabitants) is called Gares in Basque. It has nothing to do with the railway, which does not pass through here. The city dates back to the XIIth century, because previously there was only a ford on the river. With the arrival of the pilgrims, a bridge was built, from which the pilgrims leave the city. Puente la Reina takes its name from this bridge with six arches that a queen would have erected in the XIth century.

The city is designed as a bastide, completely squared in parallel and perpendicular narrow streets. Ramparts were built there, and privileges (fueros) were also distributed here to those who wished to settle there. Then came the Templars who settled in the XIIth century, building the Church of Santa Maria de las Huertas, known as the Church of the Crucifix. When the order was dissolved, the Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem took over, founding a large hospital there. The Church of the Crucifix is a beautiful church, square, like the Templars, topped with a steeple. The interior is completely bare, filled with religiosity. In the dark, you can barely see the statues, that of Santa Maria de los Huertos, to which the building was dedicated, and the wooden crucifix that appeared later in the XIVth century. The church has undergone minor modifications over the centuries. |

|

|

|

|

| In the Middle Ages, the entrance to the city was between two towers of the wall that has now disappeared. Then the route passed, as it still does today, under the arch connecting the hospital (now a college) and the Iglesia del Crucifijo. Then, as still today, the route was Calle de los Romeus, now Calle Mayor. |

|

|

| In Calle Major stands the Church of Santiago (St James), a church originally built at the end of the XIIth century, but later modified, notably in the XVIth century. There are still some Romanesque and Muslim details in the portico, but the interior smells full of Baroque. Some like it, especially the Spaniards. On the other hand, the statues, have a small air, almost of modernity. |

|

|

| When we passed here it was early afternoon, curfew or siesta time in Spain. Besides, it was Sunday. The Plaza Mayor was empty, like all the surrounding streets. But rest assured that if you pass by when the pilgrims go to bed, Spain will wake up to live again. It’s like this every night in Spain. |

|

|

| And then, Puente la Reina is obviously the bridge. The town owes its name to this strategic bridge, essential for crossing the tumultuous Arga. This XIth century bridge, where you had to pay a toll, was originally defended by three towers, one on each side and a third in the middle, with the Virgin of Le Puy. From the year 1824, we document here the visits of a txori (small bird in Basque), fascinated by the Virgin, whose cobwebs he cleaned and washed his face. We were crying out for a miracle, a miracle that lasted for years, much longer than the life of a normal bird..

Then came the Carlist Wars, the Wars of Spanish Succession, between the liberal legitimist troops of Madrid and the conservative rebel troops of Carlos. The city was then ruled by the Legitimist faction, but the minds of the people were distinctly Carlist. Even today, this whole region still votes clearly to the right. The young Count Cristobal Manuel de Villena, who was entrusted with the garrison, declared that this bird story was only stupid superstition. He even had the cannon fired to scare the bird away. But there ! The Carlist troops defeated the Liberal troops and the Carlist general had the count shot. When the people of Puente La Reina heard the news, they took it as divine retribution for mocking and wanting to drive the bird away.

Once the war was over, the bird continued its visits until 1843. That year, the liberal authorities, tired of all this history, demolished the central tower of the bridge where the statue of the Virgin was. The statue was transported with great fanfare to the parish of San Pedro, on the other side of the river, where it still occupies its place within the altar. So, imagination, dream or reality, who knows? |

|

|

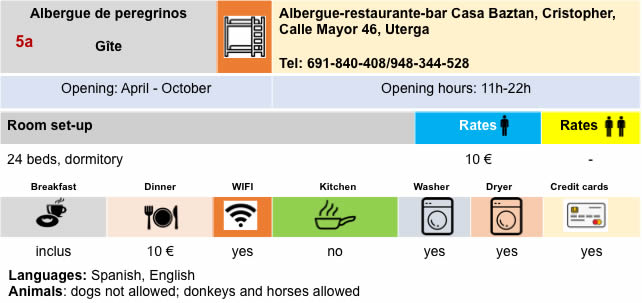

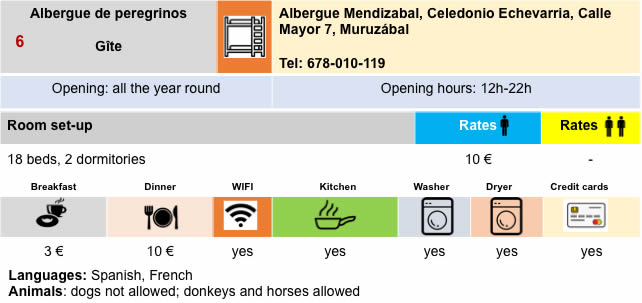

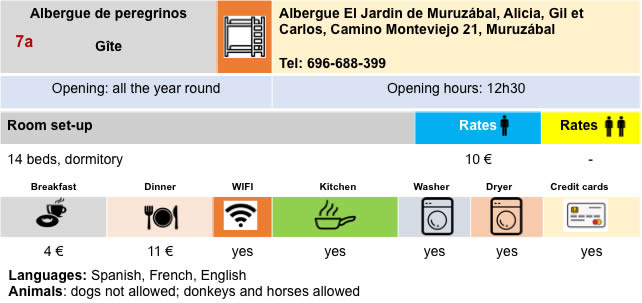

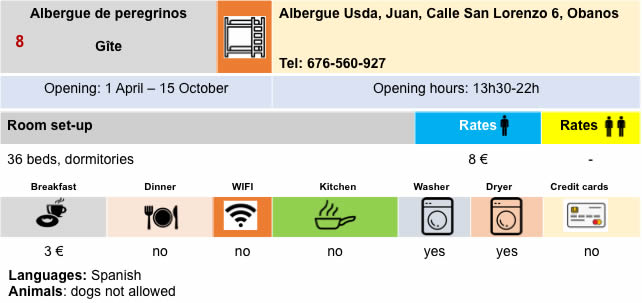

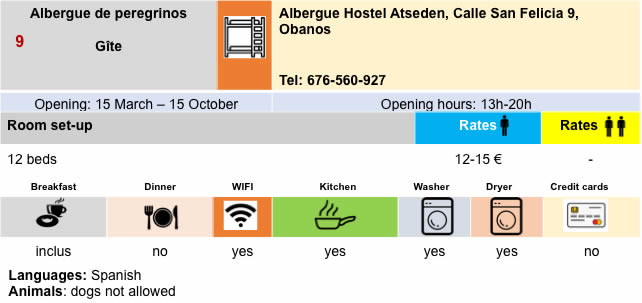

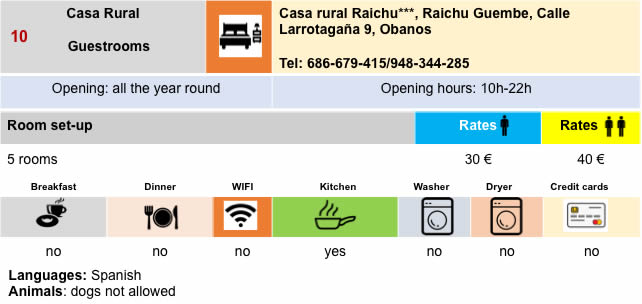

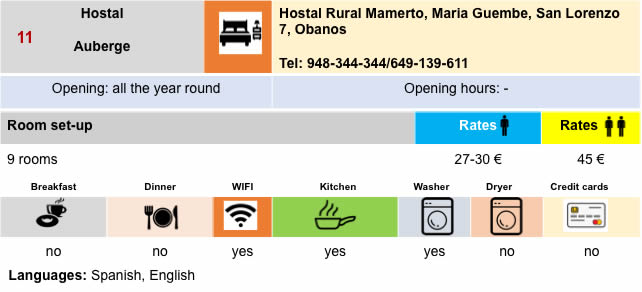

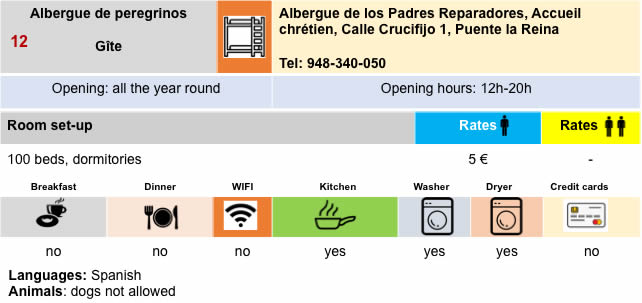

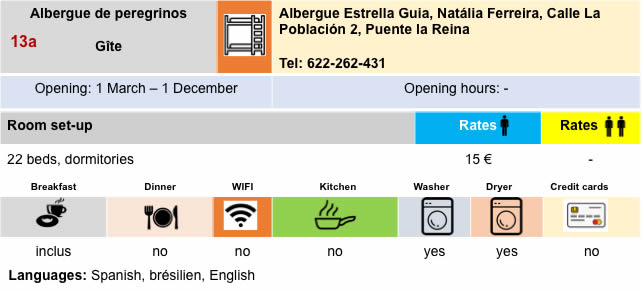

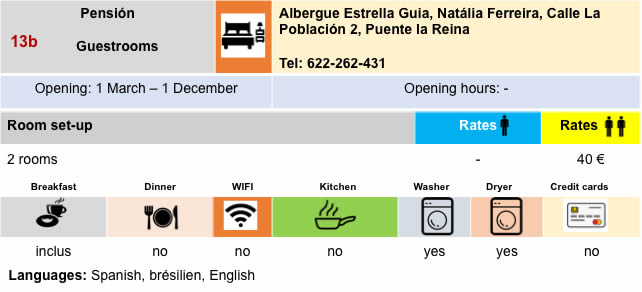

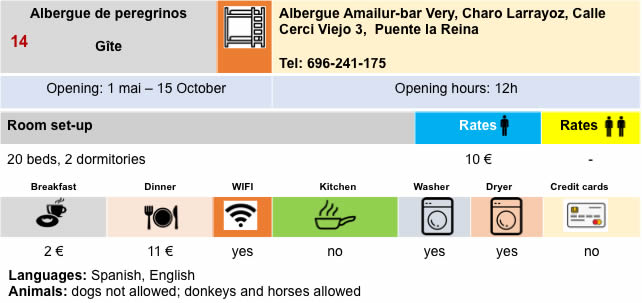

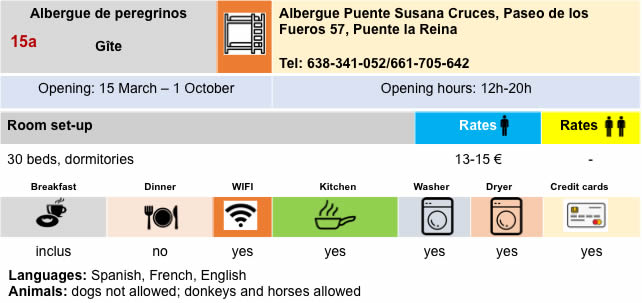

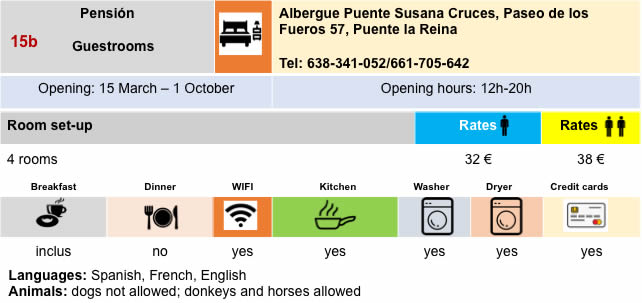

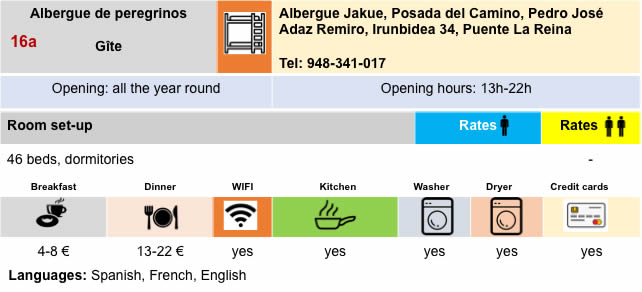

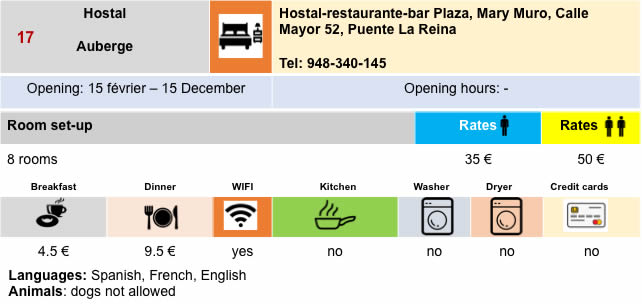

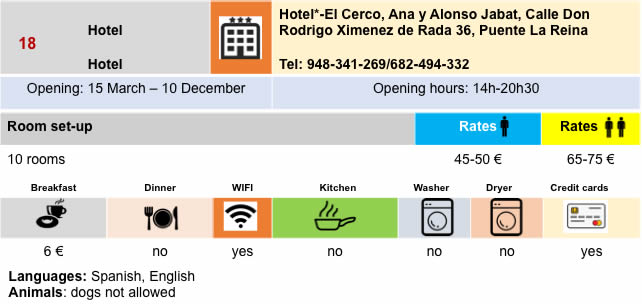

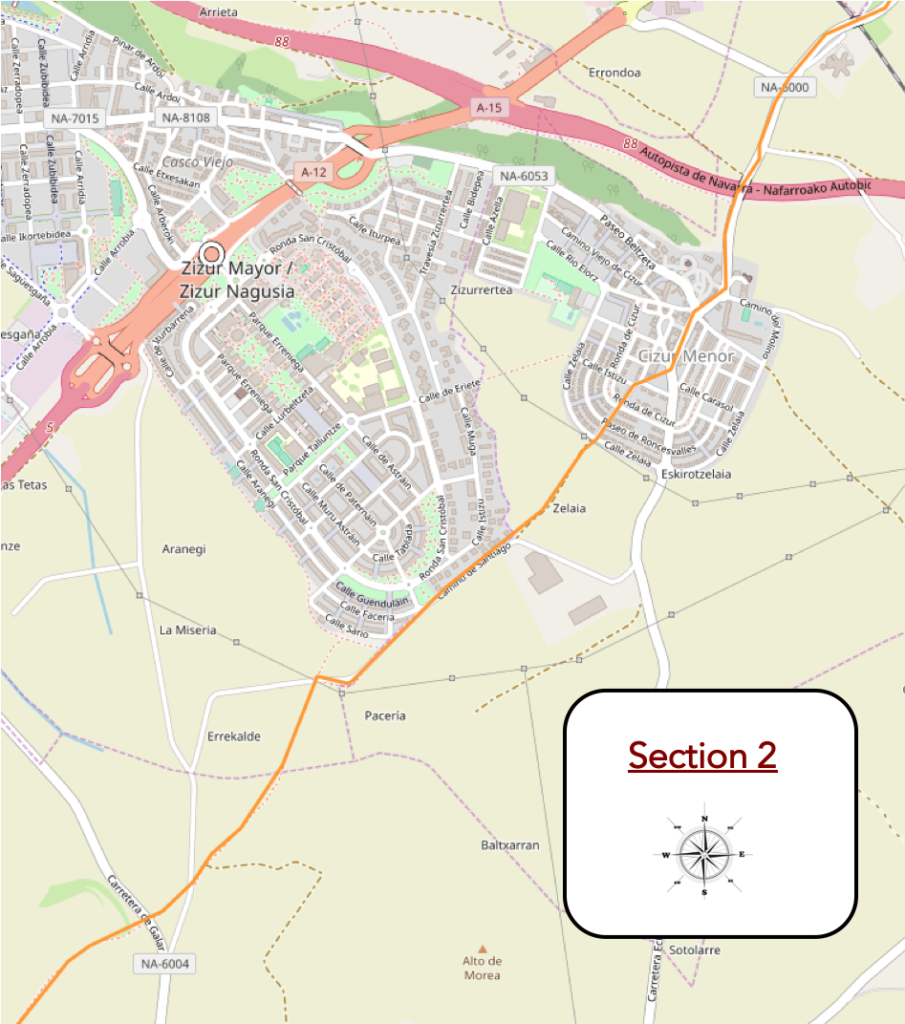

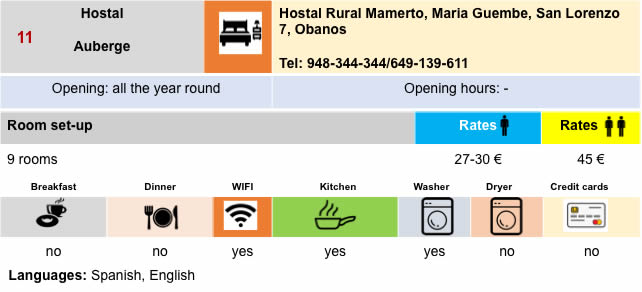

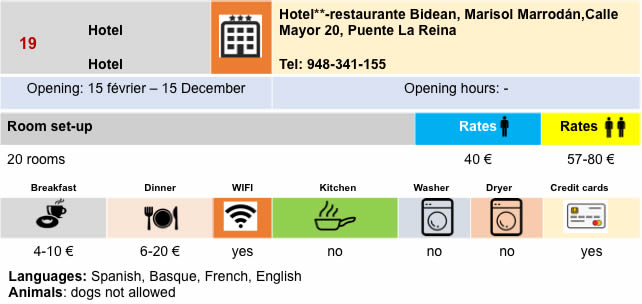

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 5: From Puente La Reina to Estella |

|

|

Back to menu |