On the “Way of Stars” but also along the Pilgrim Highway

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

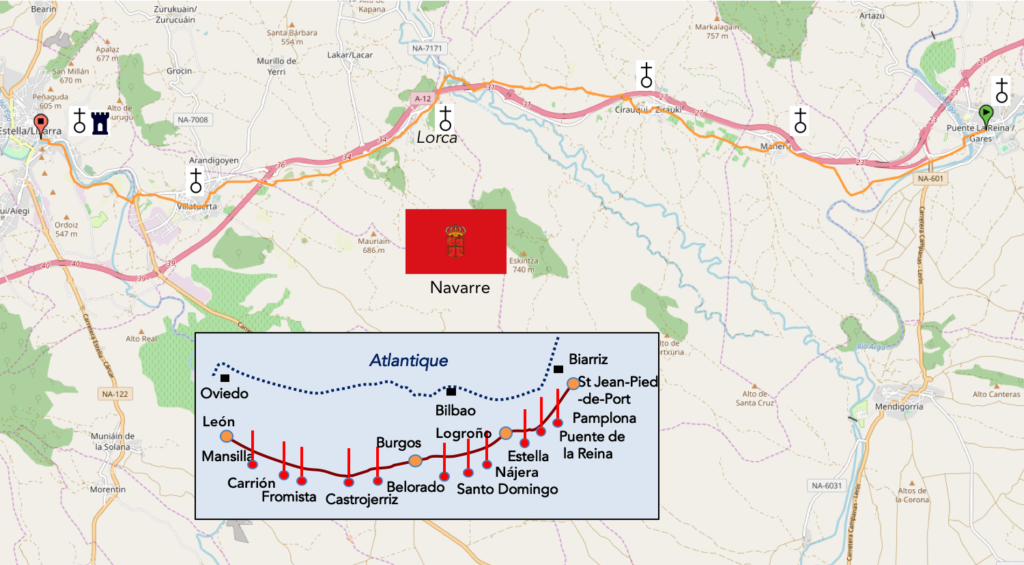

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-puente-de-la-reina-a-estella-lizarra-par-le-camino-frances-33648399

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

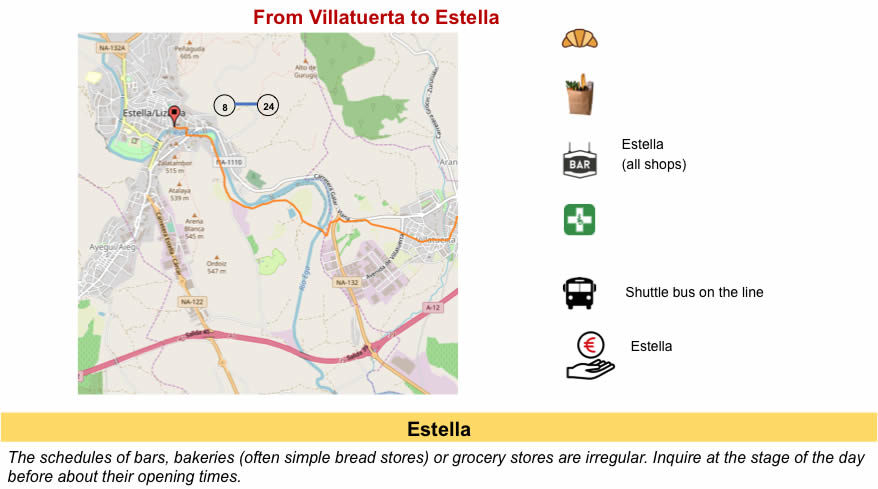

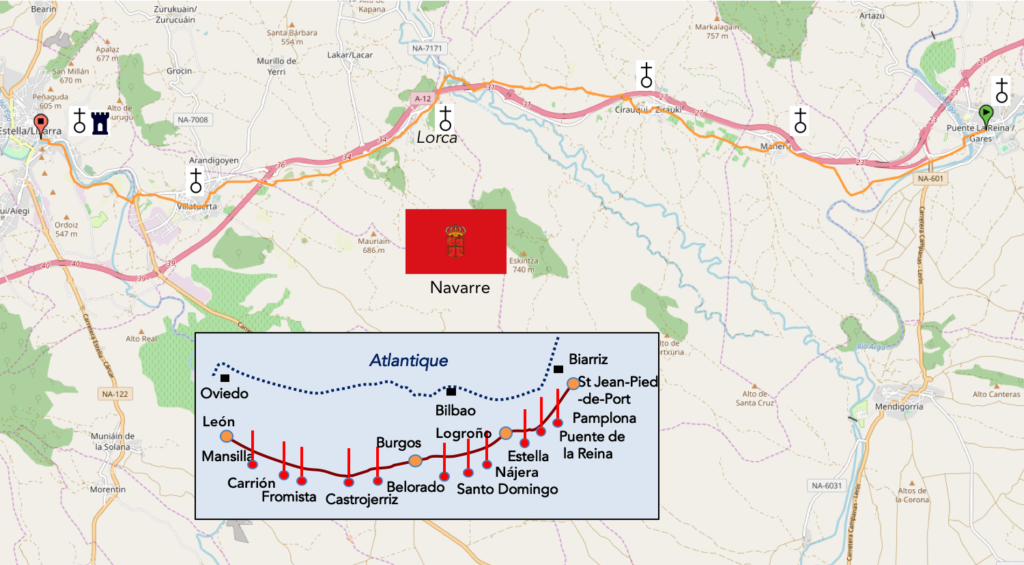

Estella already existed at the time of the Romans under the Roman name of Gebalda. Legend has it that in the 1000s, shepherds saw a shower of stars over here and discovered the statue called Notre-Dame-du-Puy. So, the village was given the Basque name of Lizarra meaning star, then the Castilian name of Estella which means the same thing.

In the XIth century, a colony of francs was established here, the francos, the Germanic people at the origin of France, part of Germany, the Netherlands, but also colonies in Spain. The king of Navarre and Aragon granted them fueros, privileges. The idea was to bring here tradesmen, bourgeois. These are the latter who developed here the Way of Compostela, many francos from Puy-en-Velay or Tours, building many hospices. Soon other communities appeared here, including the Navarrese. From the XIIth century, the city experienced a great development, and many churches were built, making the city the Romanesque jewel of Navarre. The city quickly became the flagship stop of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, with the church of San Pedro de la Rúa, the church of San Juan and several hospitals, assisted by brotherhoods.

The city knew its apogee in the XIIIth century. The city was enriched by building several convents and many hospitals and inns to welcome pilgrims. A castle and a fortress were added to contain the fancies of neighboring Castille. Then, the city fell progressively into decadence, following the many conflicts that confronted France which had Lower Navarre, Navarre and Castile, during the XIVth and XVth centuries. The city fell to the hands of Castile in the early XVIth century and they demolished the castle and the fortress. Then, during the Carlist Wars for the succession of the throne of Castile, the pretender Carlos, with the support of Navarrese who supported him, installed his court in Estella and reigned “in Navarre”, the city becoming the capital of the Carlist state. But the final victory of the centralizing Liberals of Madrid, legitimate supporters of the king, will lead to the abolition of the regime of fueros, namely privileges, and High Navarre then became a simple Spanish province in 1841.

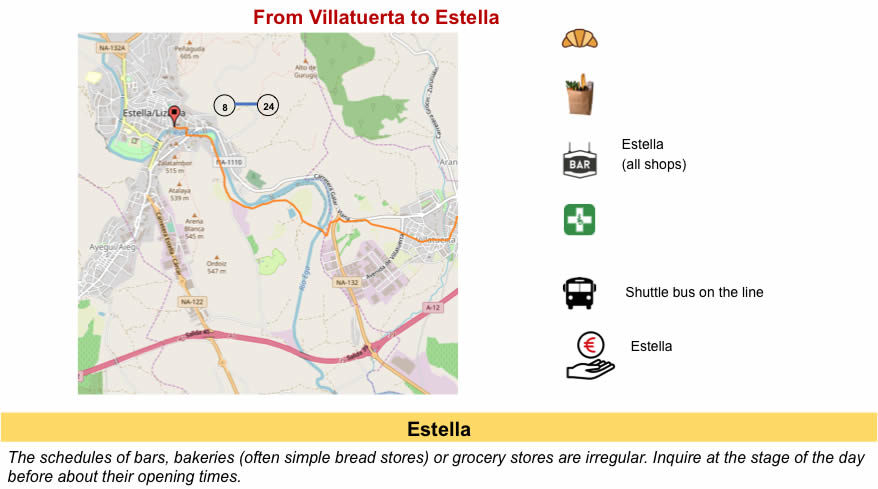

Today is a beautiful walk, one of the most beautiful on Camino francés in Navarre. The villages are pleasant, some medieval, the track is wide, little stony, undulating on small hills. Certainly, but grumpy people will say that the road is close to the highway. It’s true, but it does not bother. First, you are not next door, as will be the case later on the way. Then the traffic is low, because you do not cross a dense region of the country. And then, you’ll arrive in a pretty incredible city. Which pilgrim who was not born in Spain has already heard of Estella? None, in all likelihood. Estella is a minor city, but it is an ancient capital of Navarre, with a wealth of stunning monuments. There are more monuments here than in many large cities in Spain. To tell you it’s an important city, the train goes here, while in Burgos, you have to get out of the city to take the train.

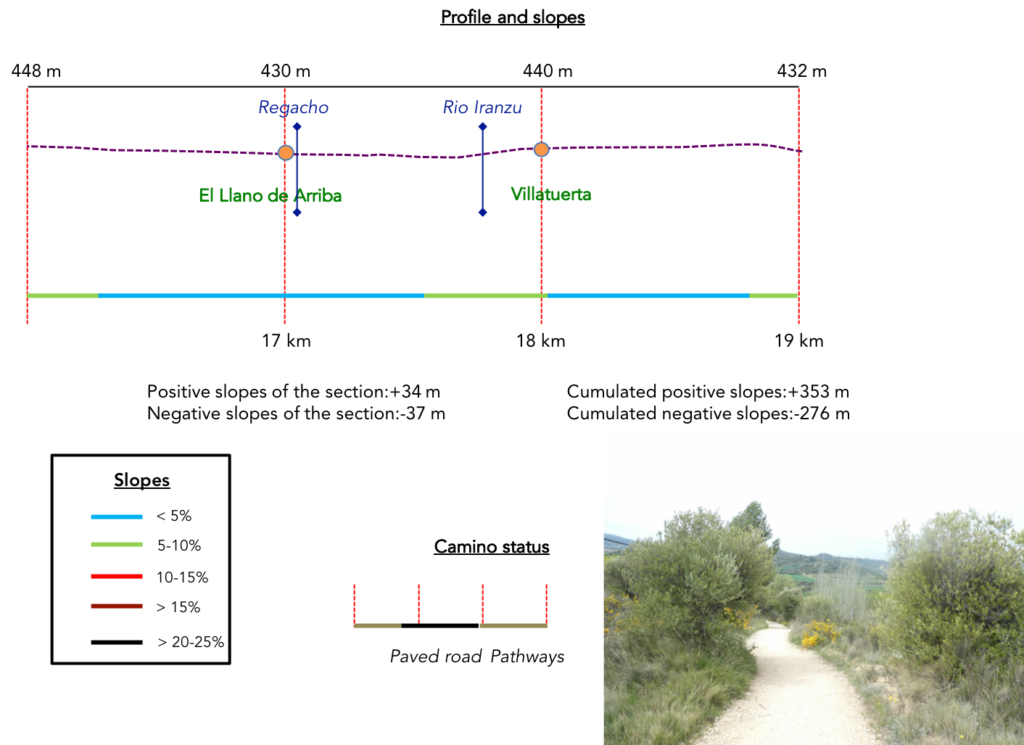

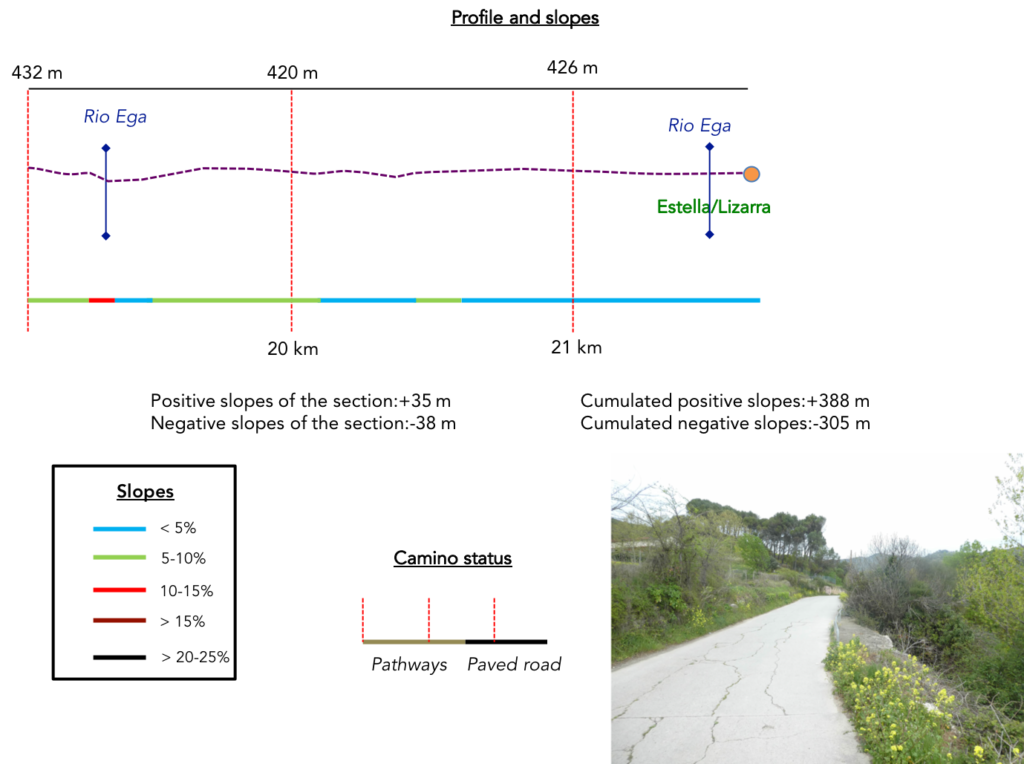

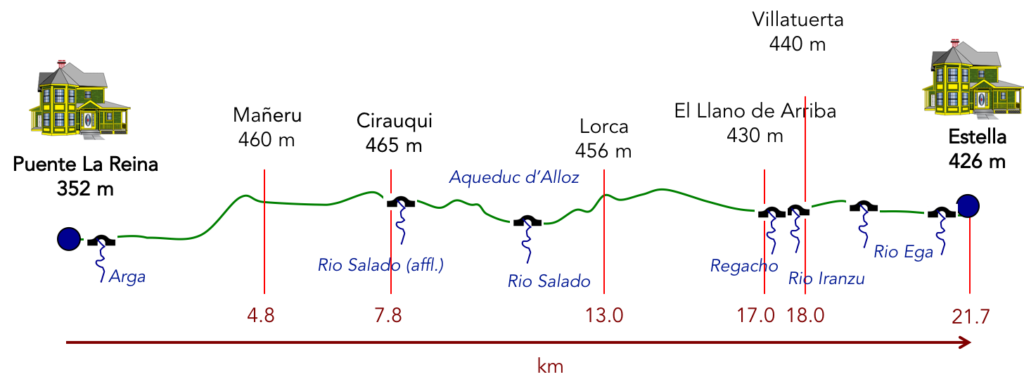

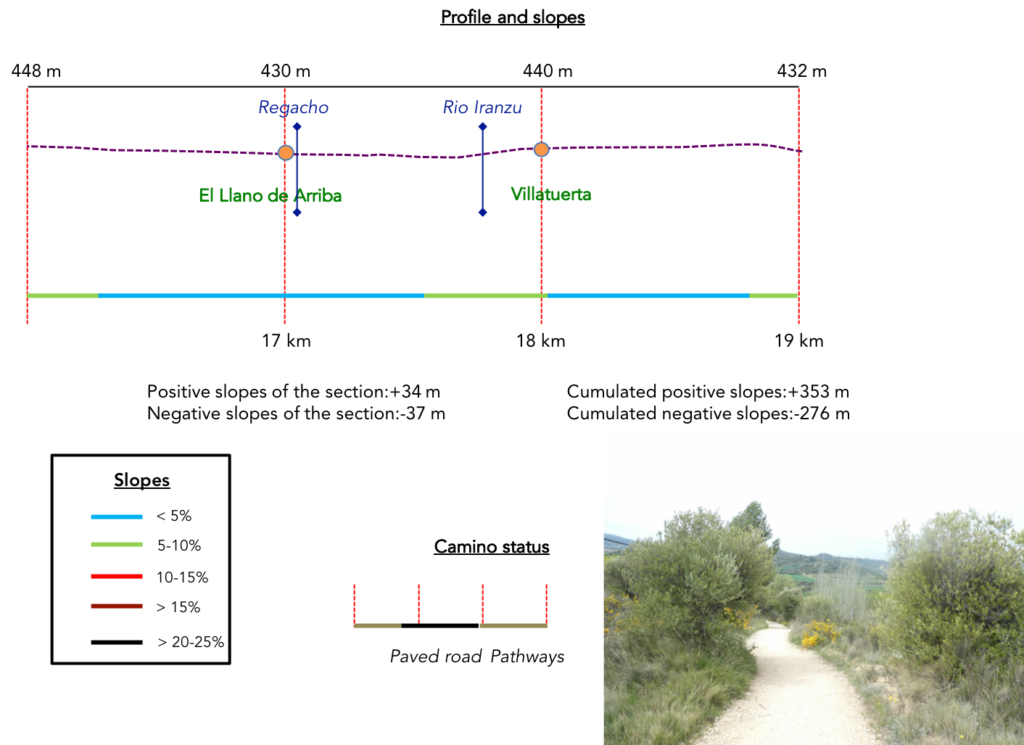

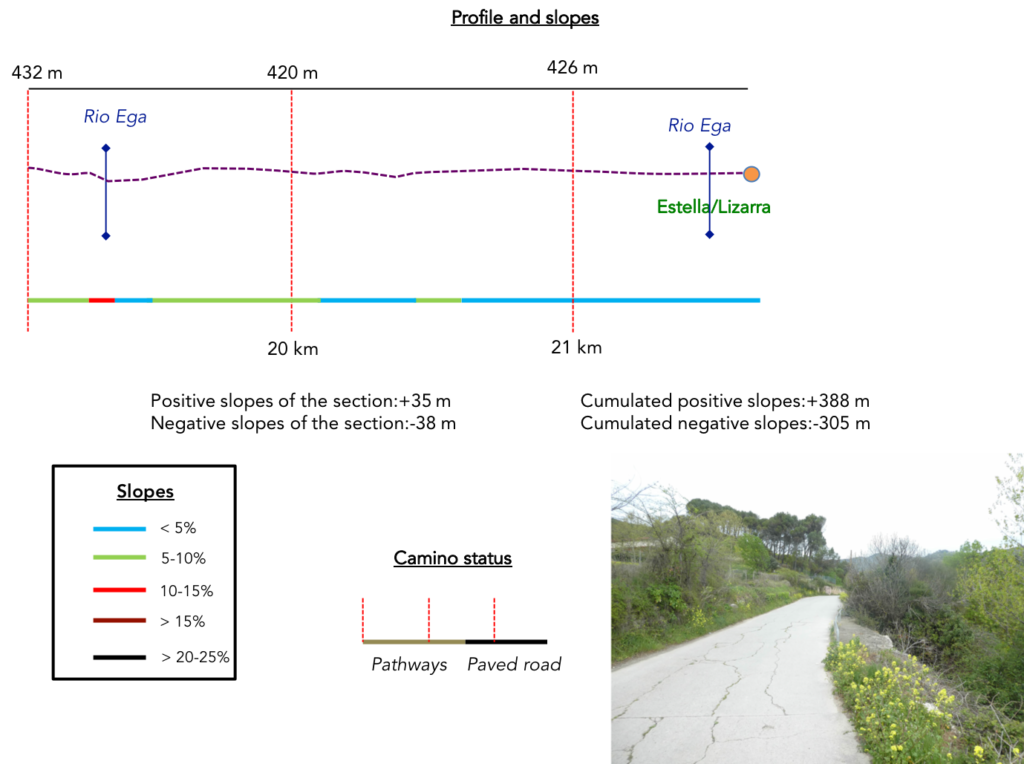

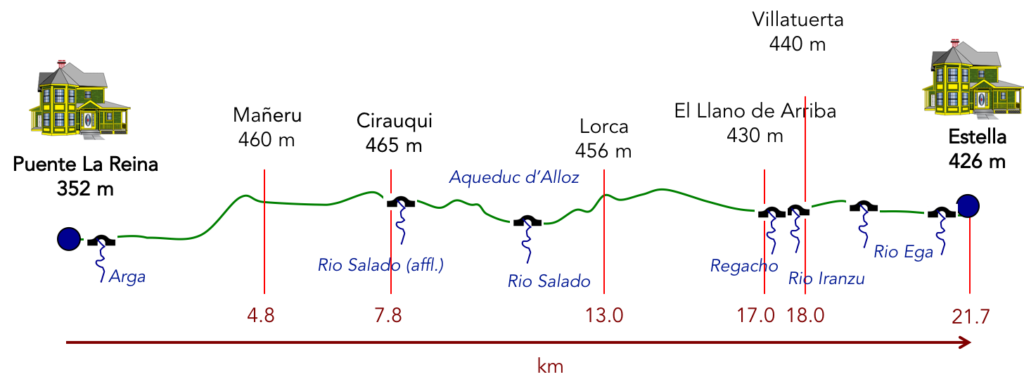

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the day (+388 meters /- 305 meters) are quite insignificant. There are only two passages where you will be asked a slight effort, first the climb to the highway shortly after Puente la Reina, then the climb to the village of Orca. Everything else is just a pleasure to walk.

In this stage, most of the course is on pathways. The passages on the paved road are only in the villages and the city. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 5.8 km

- Dirt roads: 15.9 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

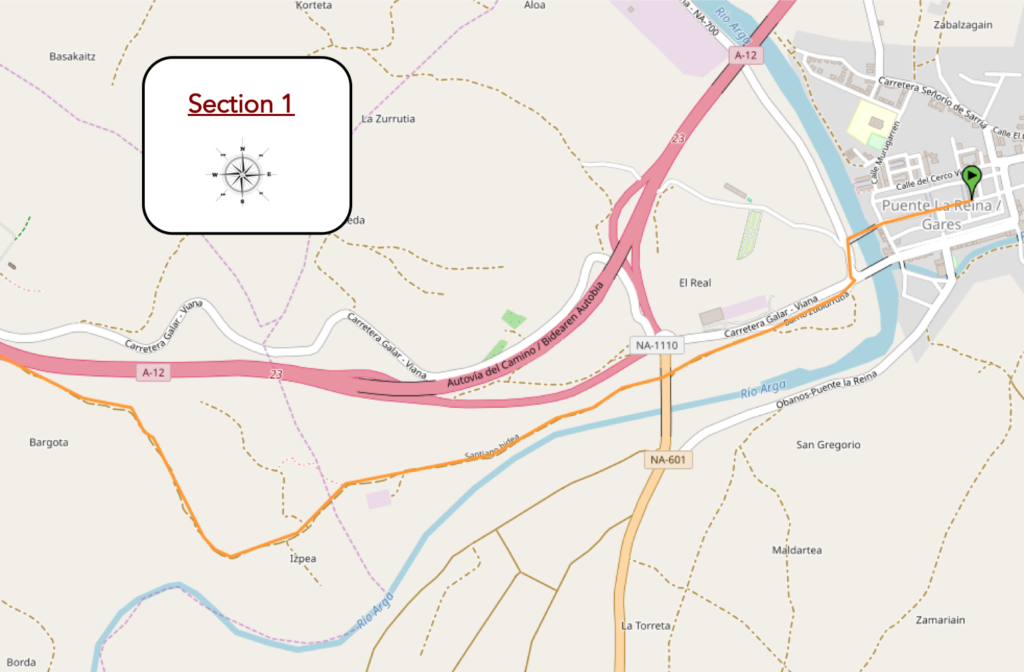

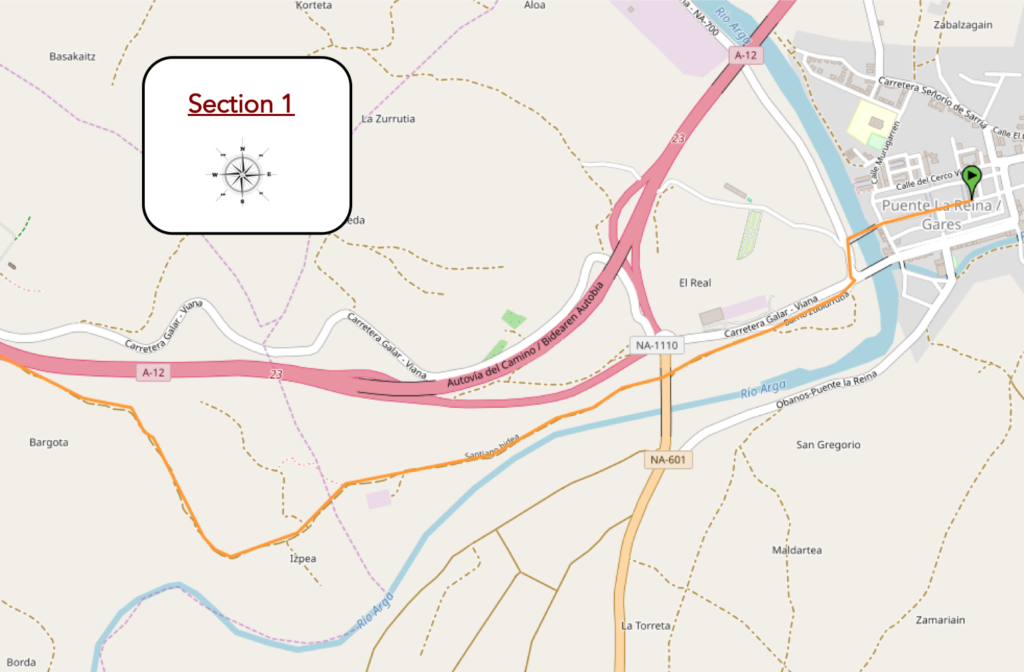

Section 1: In the Arga plain before sloping up to the highway.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: flat, then a sustained climb between 10% and 15% towards the motorway.

| At the end of Calle Mayor, the Camino arrives at the Puente La Reina bridge. |

|

|

| You saw in the previous stage the importance of this bridge thrown over the turbulent waters of the Arga River. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses the river. A little further, the national road also crosses the river on another bridge. |

|

|

| The Camino quickly leaves the main road, heads to the San Pedro church. The church is open, but inside it is dark. Is it to dissuade potential people from once again stealing the virgin from Le Puy, whose story we told in the previous stage? |

|

|

| The route leaves the village, runs on a wide dirt road, not very far from the A12 motorway, called Autovia Del Camino de Santiago, because it follows the pilgrimage route. It connects Pamplona to León, passing through Logroño and Burgos. If you take this highway in summer, you will see the armies of pilgrims walking before your eyes. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway runs along the river. Poppies and rapeseed are sown on the slopes. You see almond trees, but especially black poplars, these ubiquitous trees in Navarre and Castile. |

|

|

| It is Easter, an early and rainy year, and the poplars are gradually and slowly becoming covered with foliage. |

|

|

| The walk is very pleasant. It’s the Easter holidays, and Spanish families with children are coming a long way. In general, children tend to drag their shoes around, not all enthusiastic about the holidays offered to them. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway leaves the river. |

|

|

| The ground hesitates between ocher and red. Cultures are discreet here. |

|

|

| At the end of the plain, the pathway begins to climb under the Cembra pines and black poplars. In Navarre, Cembra pines are sometimes present, which is not the case on the French tracks. |

|

|

| Here, the effort is sustained. It is a climb of almost a kilometer, between 10% and 15% of slope. So, often, you hear behind you the sound of sticks jerkily scraping the ground and approaching quickly. They are athletes who like to get some exercise. Quickly, they disappear from your horizon. |

|

|

| In summer, it must be ecstasy here. The pines, poplars and holm oaks will hardly shade you. Above the highway hums.. |

|

|

| Soon, the summit of the climb is announced. Then you will have the privilege of taking a few steps along the highway. Your first steps… |

|

|

Section 2: Through the medieval village of Cirauqui.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without great difficulty.

| Further ahead, the pathway crosses a few fields before finding arid land and broom. |

|

> > |

| It then undulates a little before reaching the village of Mañeru. |

|

|

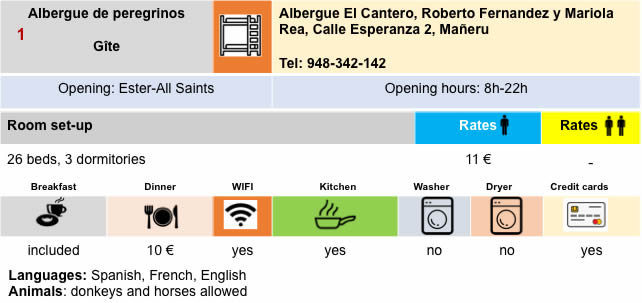

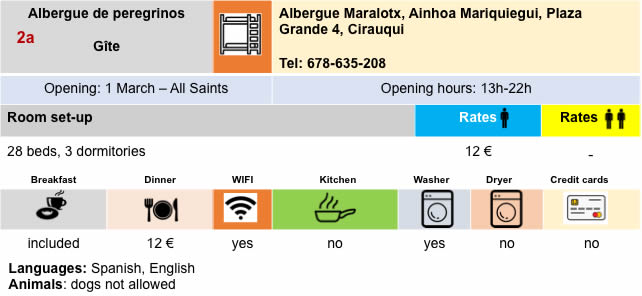

| In this village with its many jointed stone houses, some pilgrims take their first break. The climb was tough. It is time to replenish your energy at the “albergue”. Others continue. You are not going to take a break every 5 kilometers all the same! The church, as usual, is closed.. |

|

|

| The pathway leaves the village, heads towards the cemetery, distant from the village, undulating on gentle hills in the middle of cereals, poppies, rapeseed, with sometimes a few brooms in flower on the embankments. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway reaches a place called Uberoeta, through pines and almond trees. You also see vines for the first time. Here the village of Cirauqui is announced, 2 kilometers away, which you see emerging on a hill. |

|

|

| The pathway will meander along hedges and low walls in a diverse countryside. In addition to the vineyard, you also see olive trees. For many tourists, Spain is olive trees as far as the eye can see. In the center and in the south, yes. In the north, they are very rare, like bulls elsewhere. |

|

|

| The stone walls, the vine and the olive trees, it’s like being in the South. |

|

|

Further on, the village gets closer. The landscapes here are as bucolic as you could wish, with the rapeseed resewing itself and making colored spots in the wheat, with a village on the horizon so clear that one could imagine oneself in Morocco or the Greek islands.

| Shortly after, the climb is a little more sustained. |

|

|

| The pathway, after a long moderate climb, arrives in the village. |

|

|

Beauty, charm and the sweetness of life reign in this place.

| You enter through a porch and the slope is steep in the village. |

|

|

| Cirauqui is a very beautiful medieval village, with houses climbing up to the San Roman church at the top of the hill. The sloping lanes are narrow and the houses often feature carved balconies or coats of arms on the walls. The Spaniards often decorate the front of their houses with flowerpots, either hung on the walls or in the Italian style, in front of the doors or windows. The Gothic church of the XVth century retains some Romanesque parts of the XIIth century, with a strong fortress aspect. In the village there is a more modest church, Santa Catarina, whose last transformations date back to the XVIth century. Here, rosé wine is one of the jewels of Navarre. |

|

|

A charming little square is perched at the top of the village.

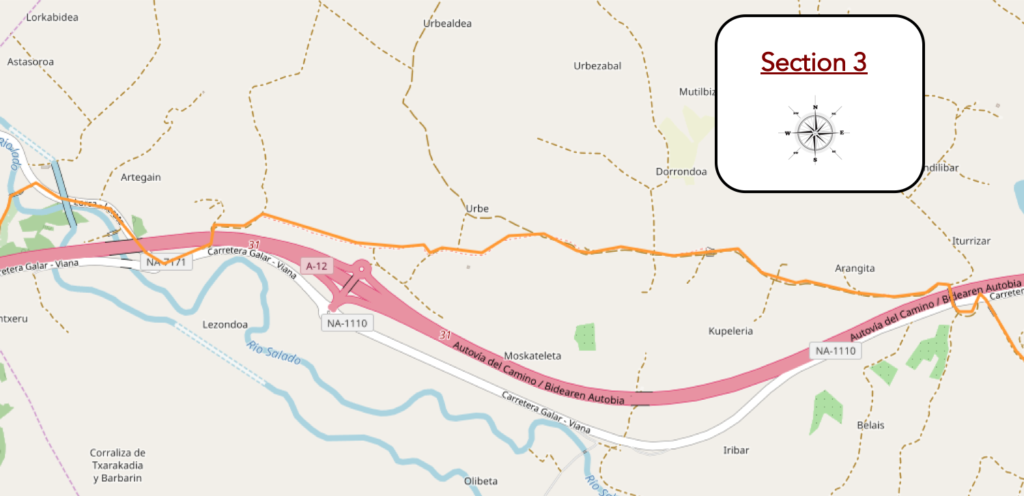

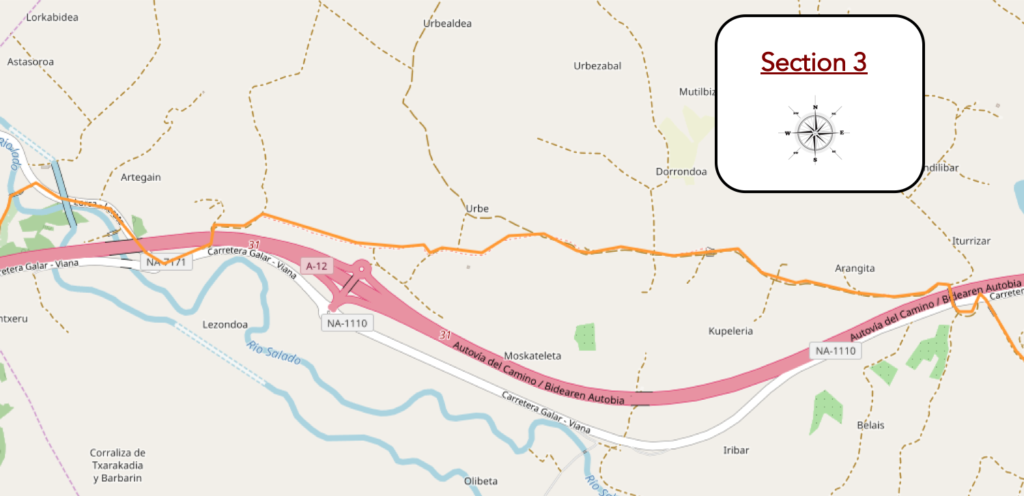

Section 3: Undulations on an old Roman road or what remains of it.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course a little more difficult, with frequent but short slopes, especially downhill.

| The Camino descends the sloping lanes on the other side of the village and arrives on an old Roman road. Here, pilgrims have replaced the legionnaires of old on the worn stones. Here, a few sidewalks and cobblestones remain, as well as a Roman bridge, the upper part of which was transformed at the beginning of the XVIIIth century. |

|

|

| There is little time here to soak up the magic of the old stones, because there is a little left on the paved pathway and on the ramps of the old bridge which crosses a tributary of the Rio Salado here. Especially since the Romans, the highway passes through here and the Camino crosses it. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a wide dirt road will then undulate up the side of the hill, on a less Roman version of the track. The vegetation is quite rough, with sometimes broom or holm oaks. |

|

|

| In a landscape where vines sometimes grow, an old Korean lady has taken refuge in her inner world. |

|

|

| The pathway, which winds through a kind of steppe with occasional crops, runs up and down constantly, sometimes with steeper slopes. Cattle are rarely present in this region, where true grasslands are rare. |

|

|

| Along the way, there is a direction for a dolmen near an esoteric site hidden under the olive trees, the meaning of which, we will admit, we did not quite understand. They even offer you a book exchange, but you couldn’t find any. Pilgrims pass here, all taken aback |

|

|

| Shortly after, the sand pathway splits, for no apparent reason. |

|

|

| Then, it rolls gently from one slide to another. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway undulates like this, sometimes on large stones, which you wonder if they are part of the Roman road, until you see the motorway below appear at the end of the ridge. Here you are almost 3 kilometers to the village of Lorca. |

|

|

Below, the highway winds between gentle hills.

| Further afield, the pathway slopes down very steeply on possibly Roman slabs, then the slope gradually softens on a wide dirt road. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent in the cereals, the pathway passes under the A12 motorway. |

|

|

| After crossing the highway, the pathway runs along the NA-7171, the national road, for a while, then crosses it, also passing under the highway, and continuing to follow the national road. |

|

|

It then crosses the magnificent Alloz aqueduct. Alloz is a dam located a few kilometers to the north. In Franco’s time, great projects were carried out to irrigate the country. Spanish engineers have diverted some of the water from the Rio Salado to circulate it through these modern-day concrete aqueducts, structures as monstrous as they are elegant.

| Shortly after, the Camino leaves the national road… |

|

|

| … to head towards the Rio Salado. In the Pilgrim’s guide, by Aimery Picaud, which is not proven, as we have already said, it is written: “in a place called Lorca, towards the east, flows a river called the salt stream; there, take good care not to put your mouth near it or to water your horse there, because this river gives death. On its banks, while we were going to Santiago, we found two Navarrese seated, sharpening their knives: they have the habit of removing the skin from the mounts of pilgrims who drink this water and die of it. To our question they answered falsely, saying that this water was good and drinkable; so we gave it to our horses to drink and immediately two of them died, whom these people flayed on the spot. ” (excerpt given by Wikipedia). This is probably the Rio Salado (salt stream). |

|

|

A very beautiful stone bridge crosses the river. Here you have an American, unfortunately often quite representative on the way. The bridge is his. From up there, like a rooster on his perch, he takes care of his affairs, howling into his phone, indifferent to all the pilgrims crossing the river.

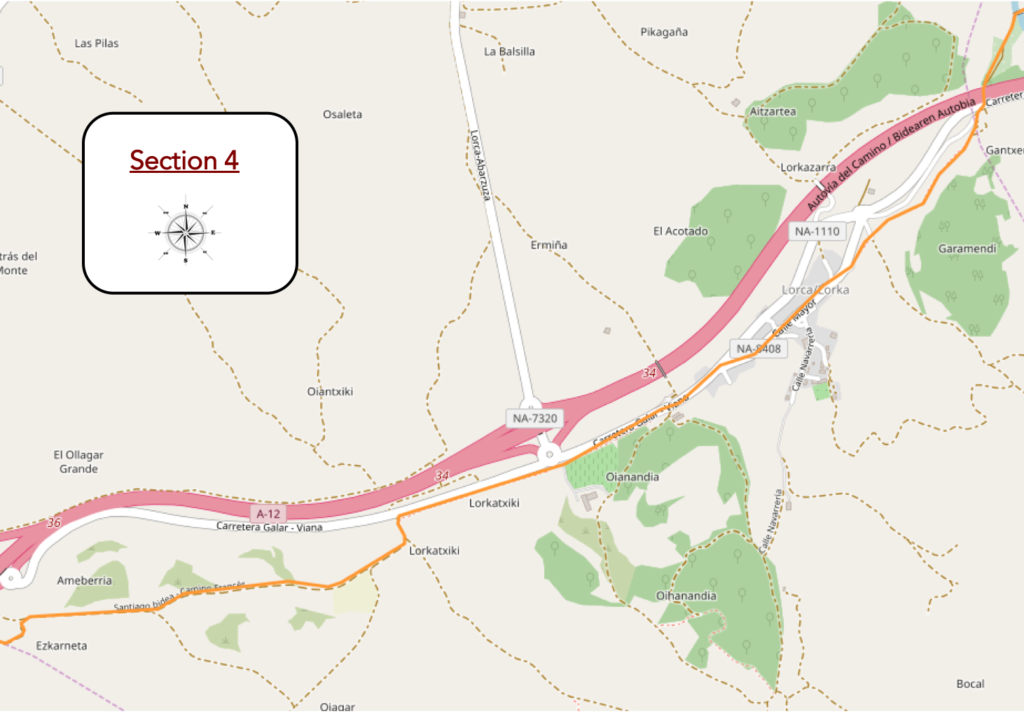

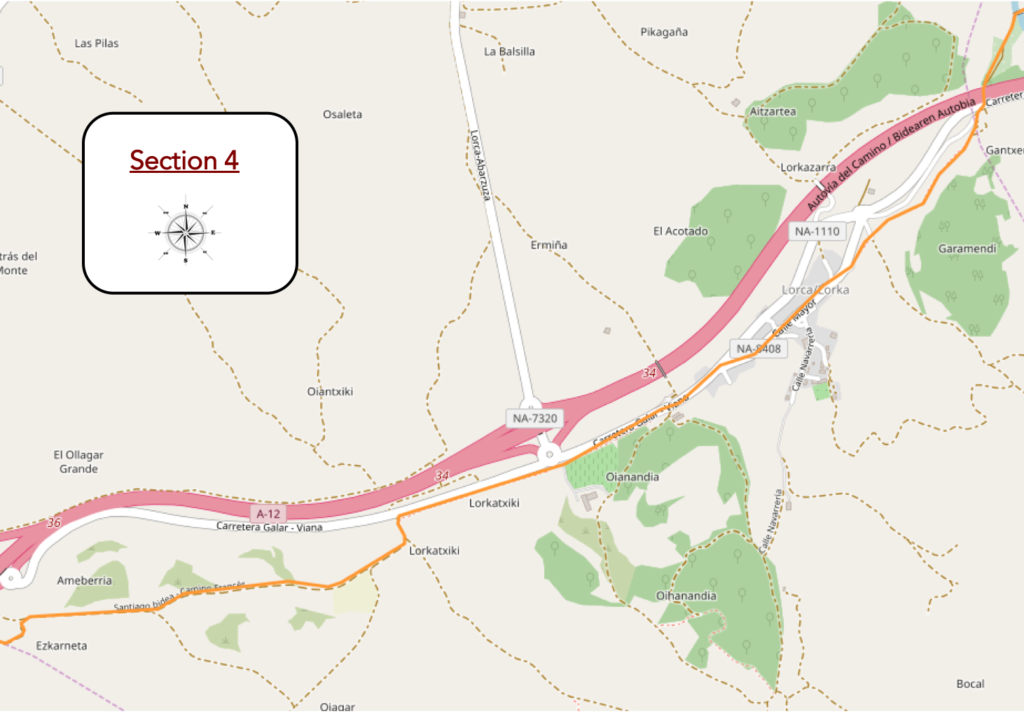

Section 4: A small dialogue with the often-nearby highway.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: except for the climb to Lorca, no difficulty.

| Beyond the Rio Salado, where the water does not flow freely, probably because it was amputated to supply the canal, the pathway follows the dale a little. |

|

|

| It then plays with the highway again, sloping up a fairly steep slope on a concrete road in the holm oaks and wild grass… |

|

|

| …and run back to the other side of the highway. |

|

|

| There, it leaves the concrete to follow a gently downhill pathway through plowed fields and holm oak undergrowth. |

|

|

| But the gentle pathway does not continue and the slope becomes steep to reach the village of Lorca. Here, in the middle of brambles and broom, a few rare olive and almond trees grow. |

|

|

| Many pilgrims catch their breath here at the entrance to the village. |

|

|

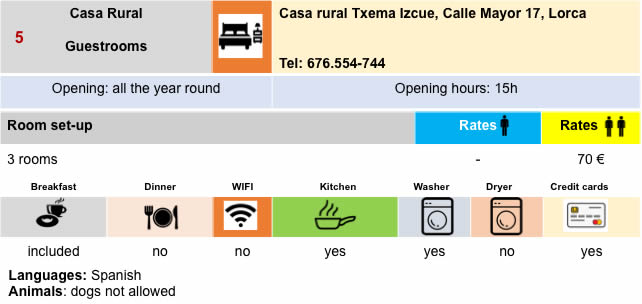

| The pathway crosses a village with opulent houses, sometimes emblazoned, passes in front of the San Salvador Church, closed, with its Romanesque XIIth century chevet. Decidedly, it becomes a habit to close the churches. One day, you will have to pay a tax to enter. Here, in the Middle Ages, there was a hospital for pilgrims. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino crosses the newer part of the village, where many pilgrims take a break at the “albergue”. |

|

|

| At the end of the village, the Camino then follows the national road again, but to deviate from it a little later. But so little! Here you find a few chestnut trees in the middle of black poplars and holm oaks. |

|

|

| Here, it is only a prelude to what will soon be your daily lot, namely kilometers along national roads. Only the landscape will change under the trees. Here, it is the vines and the fields of cereals. |

|

|

| A little further on, the pathway crosses an unimportant stream. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway leaves the main road to sink a little further into the fields of wheat and barley. When you have traveled many routes to Sanrtiago in Europe, you have seen farms everywhere outside of villages. In Spain, none of that. You won’t see any farms in the countryside. The peasants and their equipment are arranged in the villages. |

|

|

| It is now a wide, smooth dirt road that winds through the fields. |

|

|

| On the embankments where the pathway runs, the rapeseed reseeds itself in the middle of the brambles, under the holm oaks. Soon you’ll see Villatuerta on the horizon. |

|

|

| Little by little, Villatertuata approaches at the end of the plain. |

|

|

| The spring has been rainy and cold this year, and the cereals have not really grown. Some fields are still covered with green manure, sown in autumn. Green manures perform all sorts of functions. They provide nitrogen, improve soil structure, keep soils free of weeds. In principle, the list of plants used is endless. It is most often legumes (beans, peas, clover, lupins, vetches) which are popular, but also other species such as rapeseed, ryegrass, buckwheat, sunflower, barley and still others are used. When the flowers arrive in buds, farmers mow everything, crush it and bury it under the ground, before planting. |

|

|

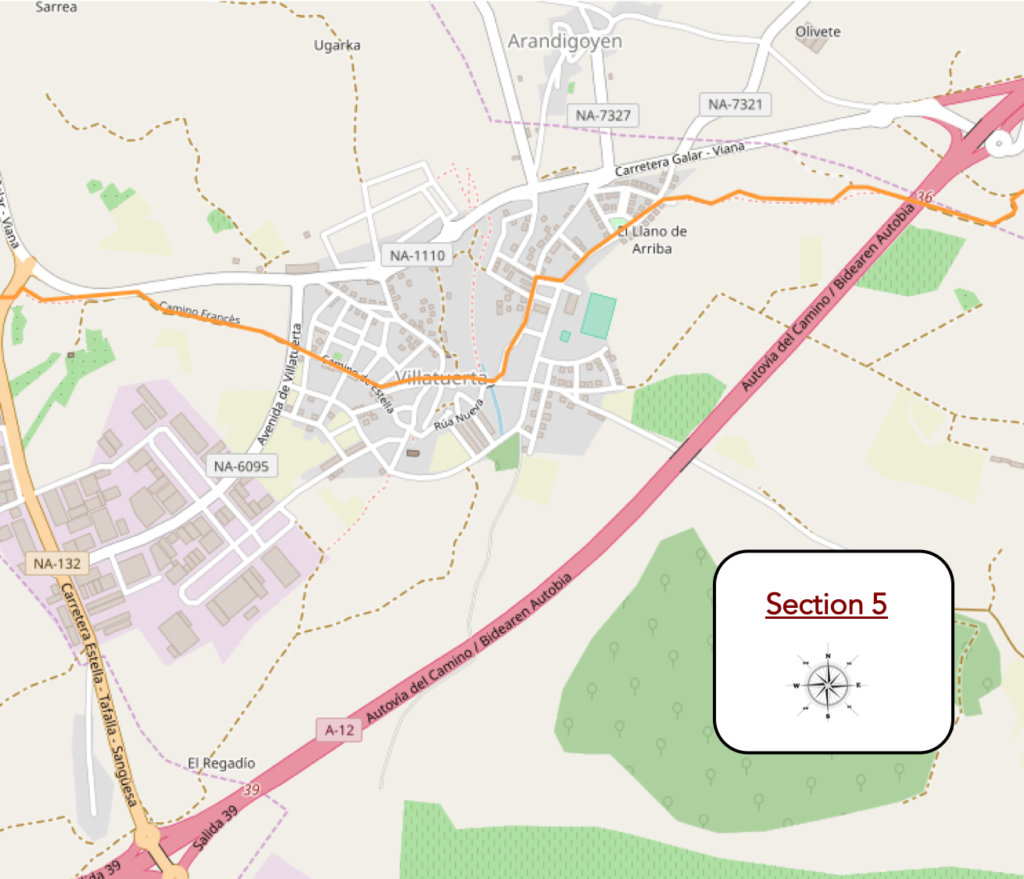

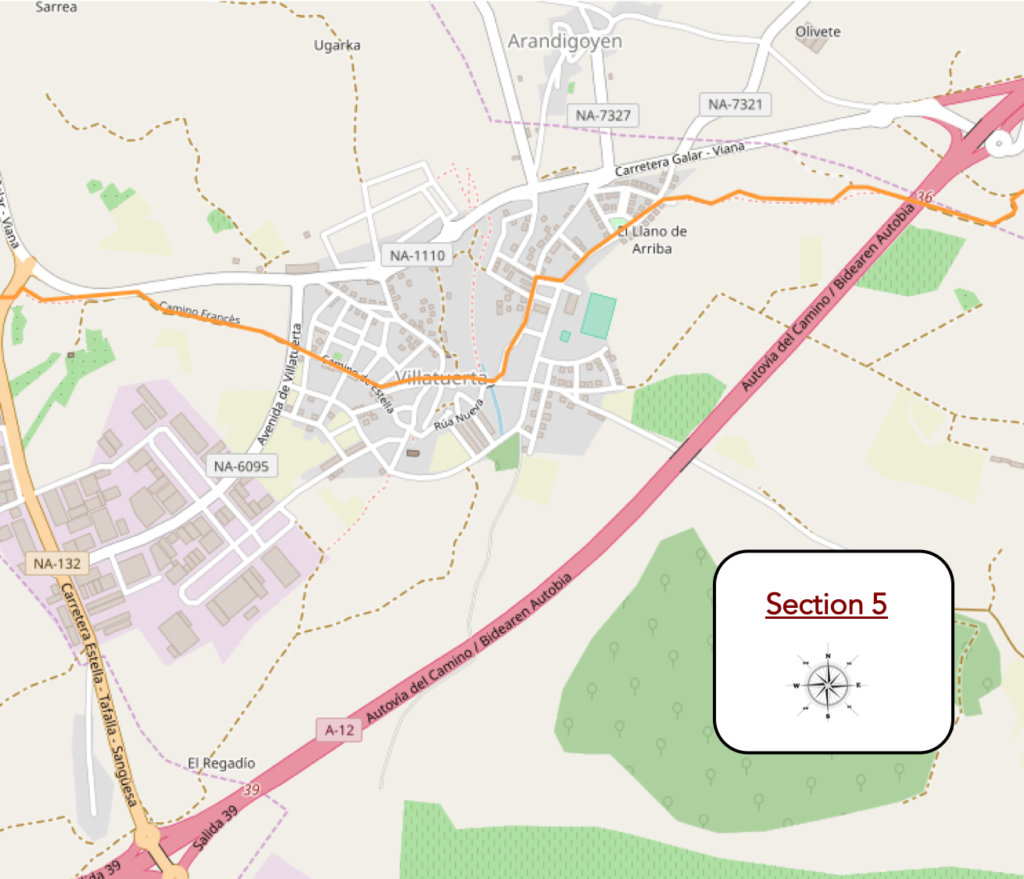

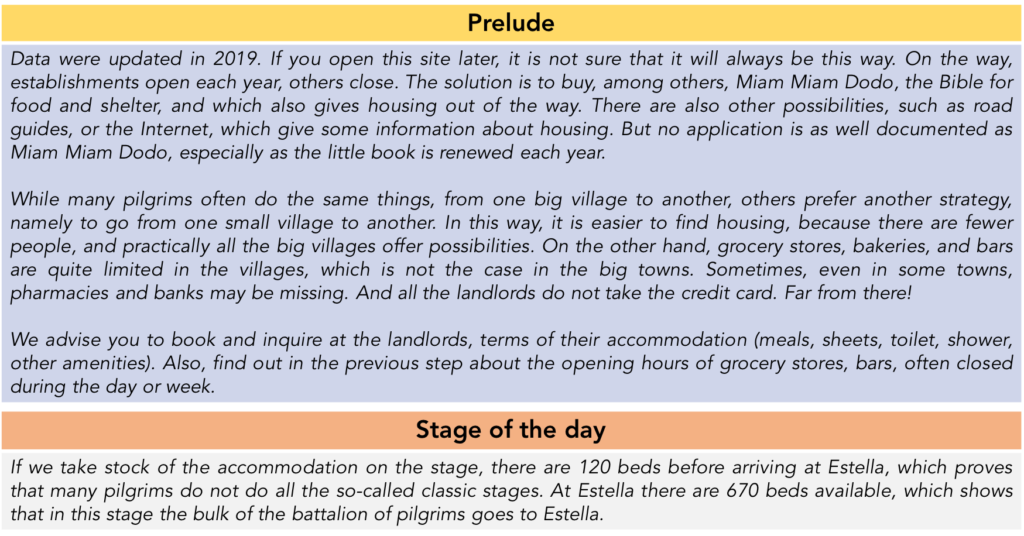

Section 5: Villatuerta, a large village in the plain.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| It is then a long passage in the plain, in the middle of cereals and asparagus. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway runs under the highway again and gets even closer to Villatuerta. |

|

|

| The pathway then arrives at the village of El Llano de Arriba and crosses the small stream of Regacho. |

|

|

| There is no transition between El Llano and Villatuerta. The Camino crosses the two villages for quite a long time. In the region, there are now many houses built of exposed brick. |

|

|

| Villatuerta is divided into two parts separated by the Rio Iranzu. The Camino passes heads to the XIIth century Romanesque medieval bridge in irregular stones, thrown over the river on the back of a camel. |

|

|

| On the other side of the bridge, the Camino crosses the village towards the parish church. The Church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción has thick walls with strong buttresses, and the base of its tower rests on a primitive structure from the XIIIth century. The rest of the original church, built during the transition from Romanesque to Gothic, was destroyed during the war between Navarre and Castile. The reconstruction in the Gothic style began and ended in the XVth century. In the square in front of the church is a statue of San Veremundo, patron saint of Villatuerta. In the churches, when they are open, there are always local people to stamp your “credencial”. Or you can do it yourself. Pilgrims prefer to display the seal of a church on their way passport rather than that of an inn. |

|

|

| Here, at the exit of the village, you are 2.4 kilometers to the end of the stage. |

|

|

| The pathway then runs back into the wheat. |

|

|

Along the way, a hermitage stands on the hill. But there! You have to walk more than 200 meters out of the way to get there! Therefore, the pilgrims do not go there. But why on earth are we still talking about pilgrims? The Camino Francés soon sees only metronomes pass by, who no longer raise their heads, eager to reach the end of the stage as quickly as possible. One day, it will be Club Med here or forced labor, it depends.

| And yet, they are wrong not to make the detour. The hermitage of San Miguel Arcángel was the church of a monastery that no longer exists. It is said to be the oldest and best-preserved church in all of Navarre, originally dating back to the XIth century, to which some renovations have been made over the centuries. The chapel was closed for a long time, which had become a refuge for vagabonds. But today it is open, so go there. |

|

|

| Beyond the hermitage, the pathway descends from the hill in bushes, olive trees and black poplars to cross a national road. |

|

|

Section 6: Towards Estella, an ancient capital of Navarre.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway then descends steeply through dense scrubland and oaks towards the Rio Ega. |

|

|

| Here, no medieval stone bridge, but a simple wooden bridge to cross the river under the alders and black poplars, a fairly wide river, the major tributary of the Ebro. |

|

|

| Beyond the river, a wide dirt road, sometimes stony, slopes up gently. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway flattens for quite a long time, in dense deciduous trees, in the middle of holm oaks, poplars and stunted ash trees. |

|

|

| As you approach the city, tar replaces dirt. |

|

|

| Soon, Estella-Lizzara appears, nestled at the bottom of the dale, along the Rio Ega. To see the signs at the entrance to the city, pilgrims will have no difficulty finding accommodation here. |

|

|

Section 7 : A quick trip to Estella.

In the famous Pilgrim’s Guide, it is said: “the bread is good, the wine excellent, the meat and fish abundant, and full of all delights”. It is also added about the river: “a river of fresh water, healthy and extraordinary”. (text taken from Wikipedia). In this city that the pilgrims called “Estella la bella“in the Middle Ages, there were six hospitals. Today, the city remains a fairly large city, with 14,000 inhabitants. The monuments are numerous here. It is when you cross these high places of the Camino francés that you really realize the impact that the Camino de Santiago created in the Middle Ages. There would never have been the explosion of these buildings in all the towns and villages of northern Spain without the pilgrims. You also understand why only the Camino francés has had the honor of being named a universal and European track, no offense to all the other European countries, where the tracks run all the same.

https://guiailustradadenavarra.com/que-ver-en-estella/

| Estella was made up of three independent boroughs (barrios): San Pedro, San Juan and San Miguel, each surrounded by its own walls. In the XIIIth century, the different barrios were unified into a single city. The first monument the Camino passes by is the Church of the Santo Sepulcro, seat of the brotherhood of the same name since the XIIth century. The church is at the end of the old Rúa de los Peregrinos, today the street of the Tanners. It is a grandiose and monumental building, in the Cistercian Romanesque style from the end of the XIIth century, with Gothic additions from the XIIIth and XIVth centuries. Of the original church, only the nave and the apse remain.Everything is massive here, in this church that looks like a fortress. |

|

|

| You can access the interior (when it is open!) through a grandiose Gothic portal from the XIVth century. It is magnificent, all adorned with arches, covings, moldings filled with biblical characters. |

|

|

| The Santo Domingo Convent is just above the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This imposing building, which looks like a fortified castle, dates from the XIIIth century. |

|

|

| It belonged to the Benedictines until 1839. Today it is integrated into an asylum for the elderly. These two buildings form a large complex on the heights of the city, where the castle and the fortress also once stood. |

|

|

| From the esplanade, you have an extensive view of the city center, with the Church of San Miguel in front of you, and at the top of the hill the Basilica of Notre-Dame Du Puy. |

|

|

| Then, the Camino engages in the old Rúa de los Peregrinos towards the historic center. |

|

|

| Along the way, you will come across the Carlist Museum. The region is politically very right. |

|

|

| Shortly after, you can cross the river on Le Puente de la Cárcel (Prison Bridge). This bridge, in one piece, is recent. It replaces identically a medieval bridge from the XIIth century, which was destroyed in the XVIIIth century during the Carlist wars, the wars of succession to the throne of Spain. If you cross the river, you will come to the city center, as most of the city is located on that side of the river. |

|

|

| But, if you follow the Camino on the old Rúa de los Peregrinos, you will arrive at the historic center of the city, at Plaza San Martin, which was the center of the city where Franks from the North had come to settle. This is where the Tourist Office is located, the former palace of the Kings of Navarre, and the Church of San Pedro de la Rúa. |

|

|

| In this district which has kept a medieval character, stands above the church of San Pedro de la Rúa, on the foothills of the cliff where the castle was located. The church stands opposite the Palace of the Kings of Navarre. It was in this church-fortress that the kings of Navarre held their services, the fueros swore. This church has been mentioned as a parish church since the end of the XIIth century, becoming the major church of the city. It is reached by a monumental staircase which opens onto a portico, richly decorated where the Cistercian and then Moorish Romanesque influences blend. The construction of the building began in the last quarter of the XIIth century, probably on the foundations of an older church. The interior still presents parts of the first church of the XIIth century, in particular the bedside. The naves are from the XIIIth century, in the Gothic style. The rest of the building is divided between the XVIth and XVIIth centuries. It is therefore a very composite building. This church is in an area of the city originally founded as a separate burgh to settle French pilgrims who had decided to stay and live here after their pilgrimage to Santiago.

The church is quite bright, with many altarpieces, where, if you appreciate baroque and rococo, you will find what you are looking for. |

|

|

|

|

| In the Romanesque cloister adjoining the church, two galleries disappeared when the neighboring castle was blown up in the XVIth century. The cloister is magnificent, sober, with beautiful capitals, and even some curious oblique columns. |

|

|

| From the steps of the church, you can see the Palace of the Kings of Navarre below, a Romanesque building built in the second half of the XIIth century. The building is pierced with arcades and galleries with beautiful capitals. |

|

|

| Across the river is the city center. The city has many small squares, most with arcades. The largest is the Plaza de los Fueros, the commercial center of the city, where the parish church of San Juan Bautista stands. This church, originally dating from the XIIth century, has undergone many transformations over the centuries, mixing Romanesque, Gothic and especially neo-classical, the current facade dating from the XIXth century. The Retablo de los Santos Juanes altarpiece, dedicated to San Juan Bautista and San Juan Evangelista, is said to be one of the finest Renaissance altarpieces in Navarre. Perhaps, but it would probably be necessary to open the church to verify it. |

|

|

| The old town is criss-crossed by narrow, charming streets with gutters, deserted at midday, as is customary in Spain. |

|

|

| You have to climb above the Plaza de los Fueros on a rocky escarpment that also served to defend the city, to find the imposing church of San Miguel. Like all the other churches in the city, it dates from the XIIth century, during the expansion of the city caused by the influx of pilgrims from Compostela. Like all the others too, it has been transformed over the centuries, with a little Romanesque, but above all a lot of Gothic and Baroque. It is not difficult to imagine the competition that must have taken place here in the construction of all these churches between different communities, Franks, Navarrese, Jews, on both sides of the river. |

|

|

| The church looks like a fortress. |

|

|

It is accessed through two gates. On the south side, the XIIIth century portal is bare, simple, with bare arches supported by capitals decorated with plants. The North portal is rich, covered with scenes from the Old Testament and the New Testament, mixing the late Romanesque, then the Baroque, having been revised in the XVIIth century

| The interior of the church is dark, and you can barely make out the statues. The chevet, with its five apses, dates from the end of the Romanesque period, with barrel vaults. The three naves are Gothic, having been remodeled in the XIVth century. |

|

|

|

|

| Leaving the city center, you will find the inevitable Plaza de Toros. Here, there are places reserved for the authorities, the mayor and the doctors, the latter being probably there to treat the injured bulls.

On the hilltop stands the basilica of Notre-Dame Du Puy, the current very recent basilica replacing an old baroque church. The basilica, closed to our passage, should have a painting of the Virgin of Le Puy, patroness of the city, covered in silver, dating back to the 14th century.

Another little word of gastronomy to end the visit. This is where you eat the gorrín, the suckling pig. It is practiced as in neighboring Portugal, by grilling it on a spit over the embers. You have to spend the weekend here to find it. But if you are lucky, it is an incomparable delight. |

|

|

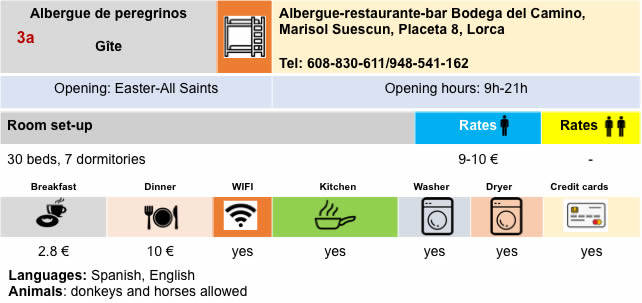

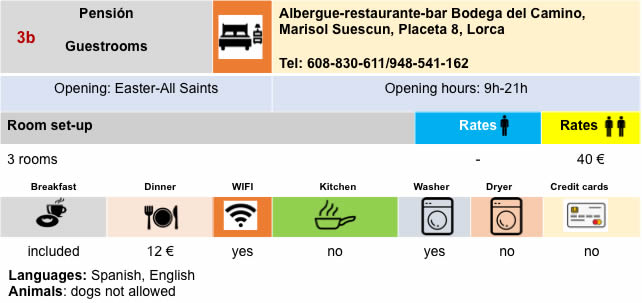

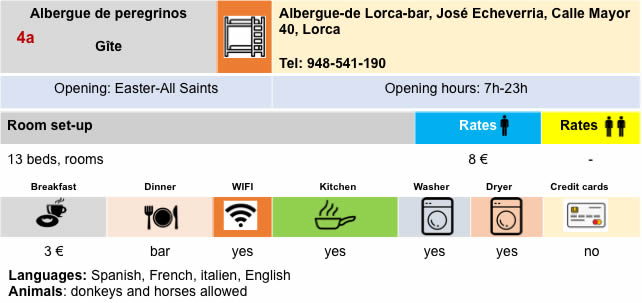

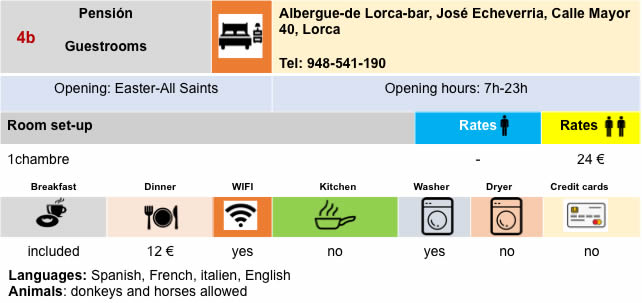

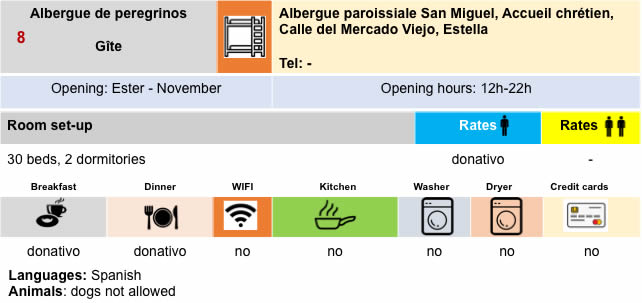

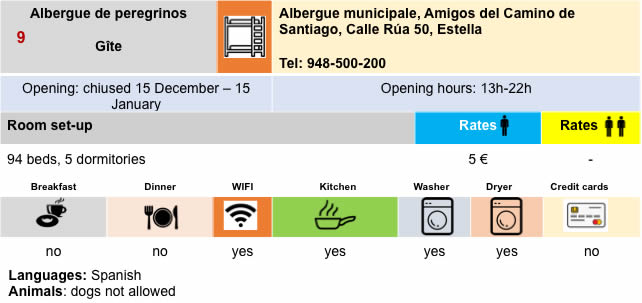

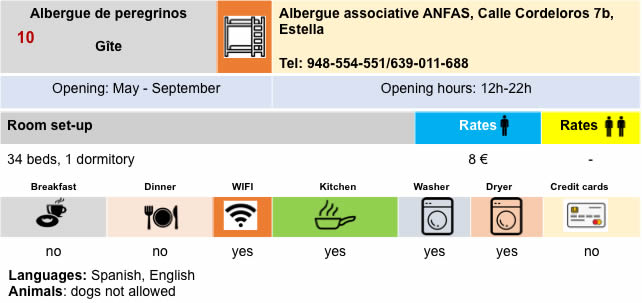

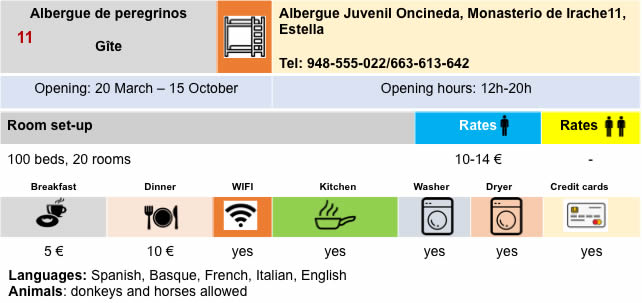

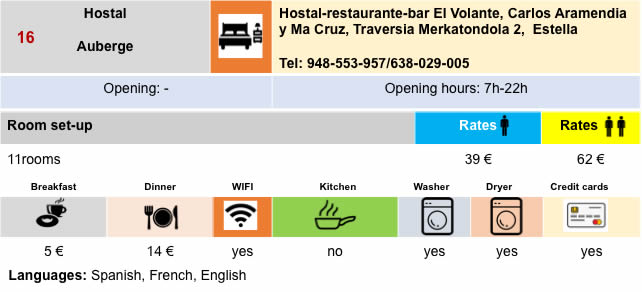

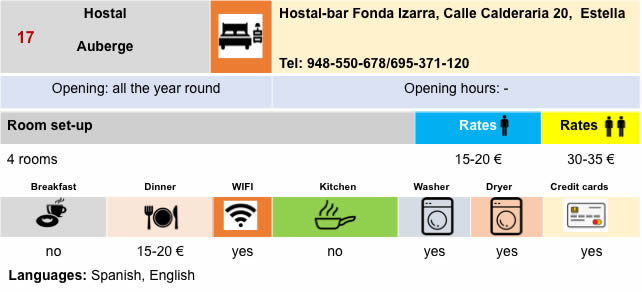

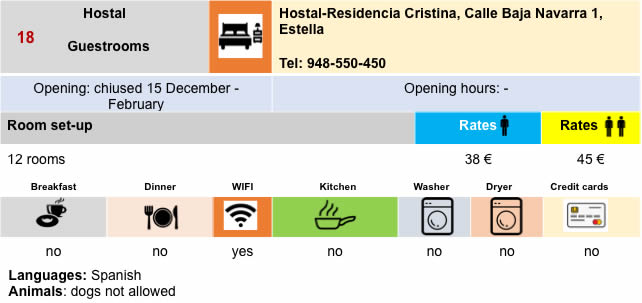

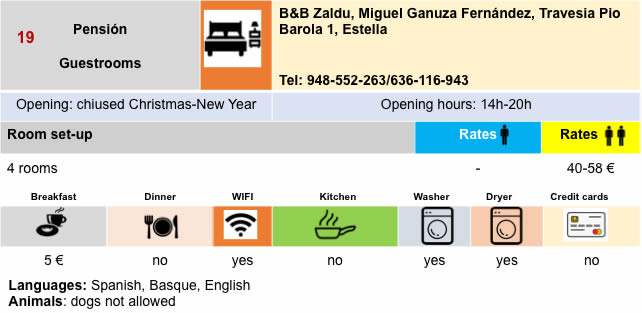

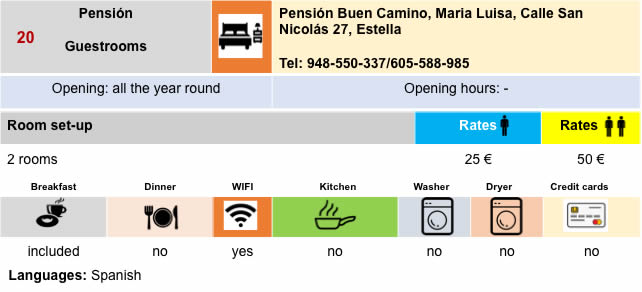

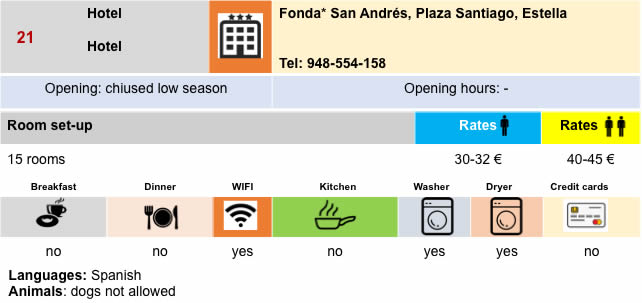

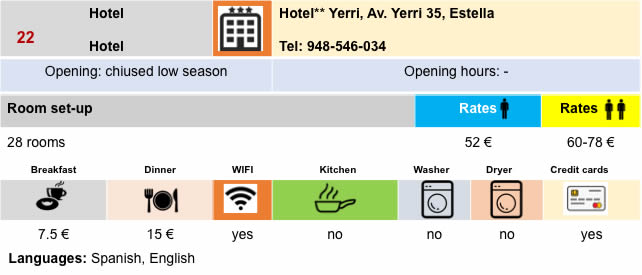

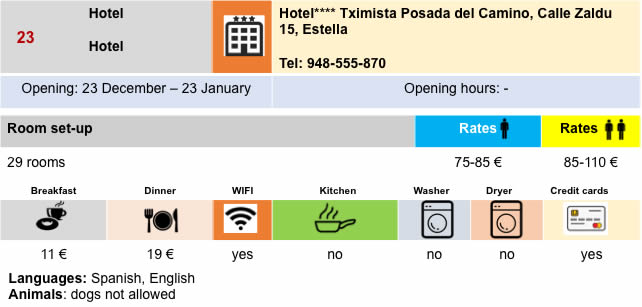

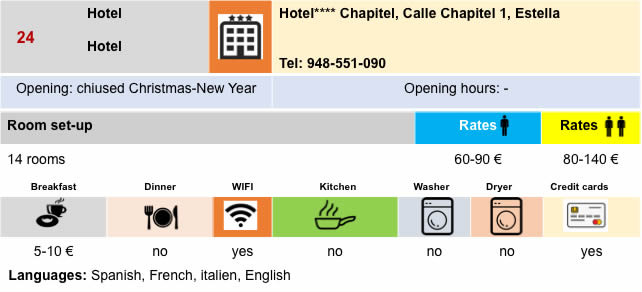

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 6: From Estella to Los Arcos |

|

|

Back to menu |

>

>