At the foot of the Cruz de Ferro

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

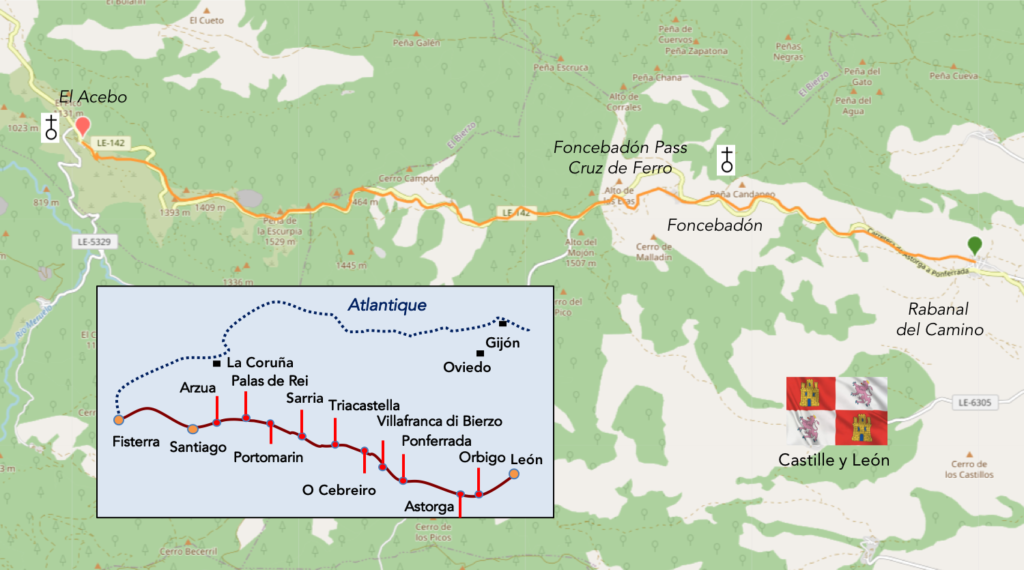

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-rabanal-del-camino-a-el-acebo-par-le-camino-frances-117323087

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

It is at Cruz de Ferro, at 1500 meters above sea level, that the first ritual act of the pilgrimage takes place. At the foot of this cross, stuck at the top of a long pole, the pilgrim places a stone symbolizing his sins. In the Middle Ages, it is said that pilgrims turned their backs on the sanctuary when making their request, a ritual that had also been adopted by the muleteers of recent centuries when crossing the pass. Today, only rare pilgrims who bring a stone in their bag from the start or take it from another place along the way know the ritual. At Le Puy-en-Velay, for example, the prior suggests that pilgrims do so and deposit it here as a testimony of their passage. Others leave sentences written on the round stones or on a paper that they leave attached to one of their travel objects. From then on, this place, like the terminus of the track at Fisterra, by the sea, tends to become more like garbage cans than places of offerings. Road garbage collectors check these common landfills from time to time.

Due to its geographical position, the mast probably also served as a road indicator in winter, during heavy snowfalls. A wrought iron cross was placed by Gaulcemo, abbot of the hospitals of Foncebadón and Manjarín at the end of the Xth century, for the benefit of pilgrims. The original cross has been kept in the Museum de los Caminos de Astorga since 1976. And fortunately, the original has been preserved, because often the replica of the pass has suffered snubs, and sometimes the mast has even been taken away.

The other two ritual acts are now abandoned. According to tradition, in Triacastela, the pilgrim also took on a limestone stone and had to transport it to Castañeda, where it was transformed into lime to be used in the construction of the basilica of Compostela. The third ritual took place about ten kilometers from Santiago, at Lavacolla, where the pilgrim had to purify himself in a river before presenting himself to St Jacques in Santiago. These places were mentioned in the Calixtinus codex. So, go the myths of the pilgrimage. Others see in this pile of pebbles an altar dedicated to offerings to the god Mercury or to Celtic deities. But, of course, the pilgrims have also greatly contributed to increasing the volume of the heap over the centuries. Now, you could well imagine that if each pilgrim had brought his stone, the heap would be much higher and that a cable car would have been needed to climb it. Or, some have come to draw from the heap for their constructions.

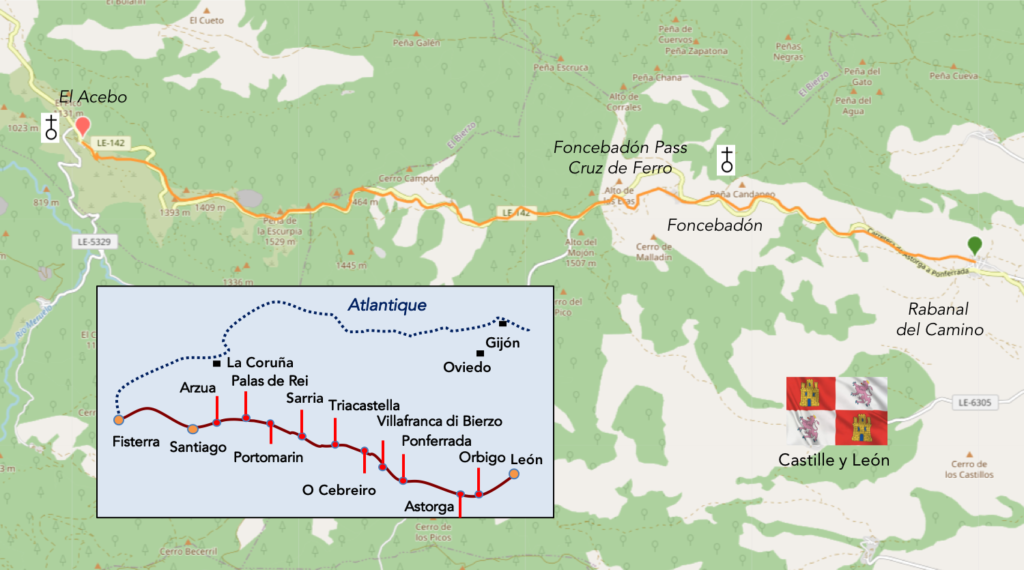

In the route of the day, you’ll walk again in Maragateria until the pass of Foncebadón, somewhere in the Montes de León. Then, beyond the pass, you switch to the Plain of Bierzo, a fairly wide valley that runs between the mountains of León. In two days, beyond the Bierzo, you will have the leisure again to climb the other side of the mountains of León to cross at the top the pass at O Cebreiro towards Galicia.

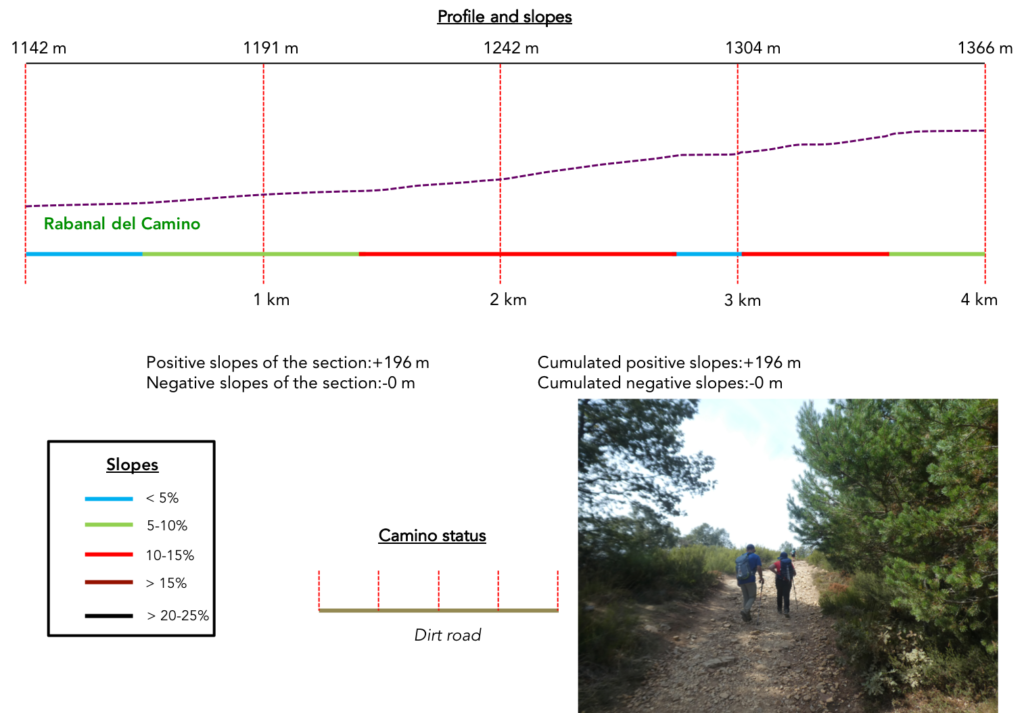

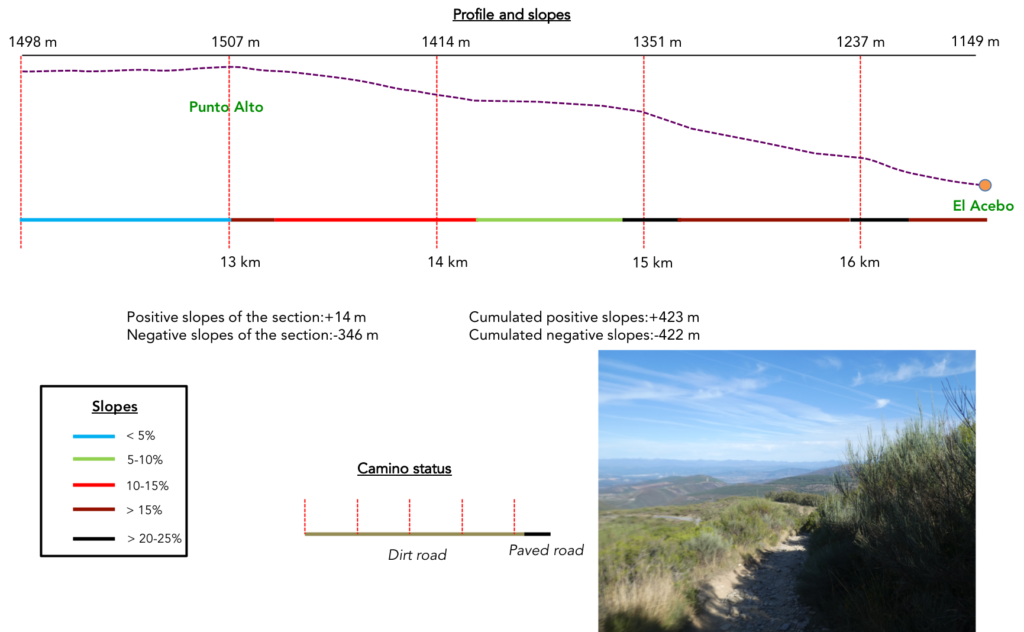

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+423 meters/-422 meters) are substantial for a fairly short stage. If the climb to the pass does not pose great difficulties with reasonable slopes, the descent at the end of the stage is delicate, very demanding. It is beyond Navarre the most significant difference in altitude of the route.

Today the pathways have very clearly the priority. There are no roads, except in the villages. Total happiness, right? Except that downhill, they are not really pathways, let’s say rather scree:

- Paved roads: 0.6 km

- Dirt roads: 19.4 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

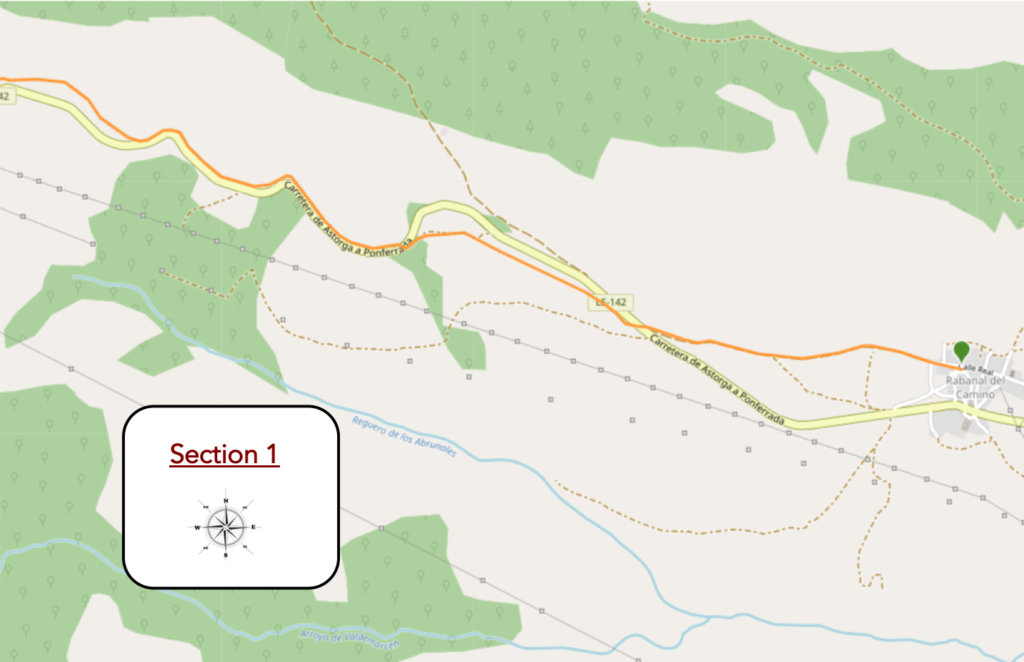

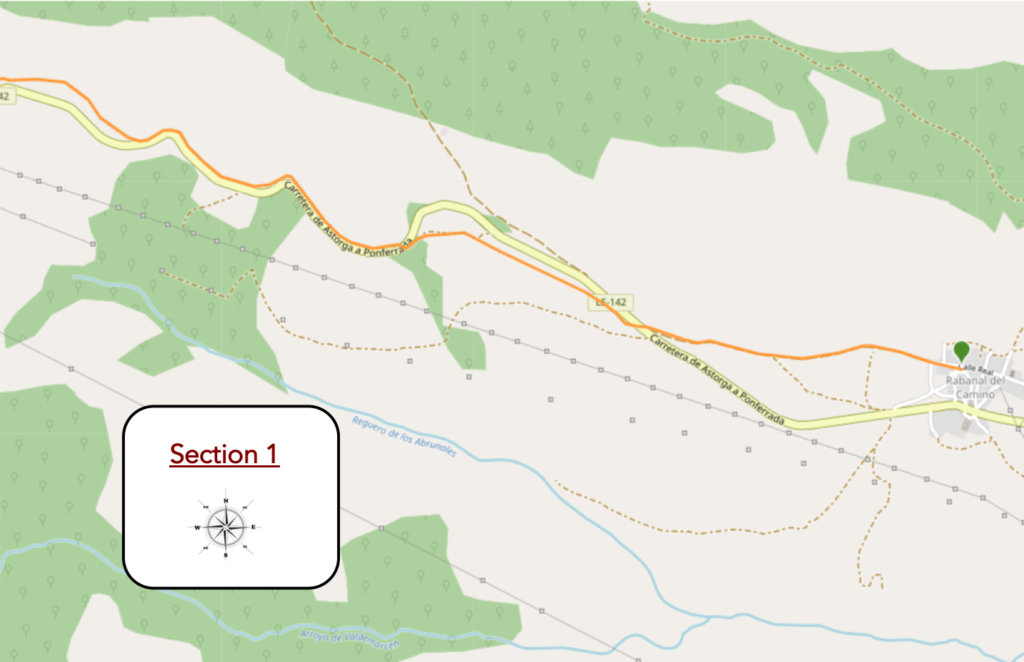

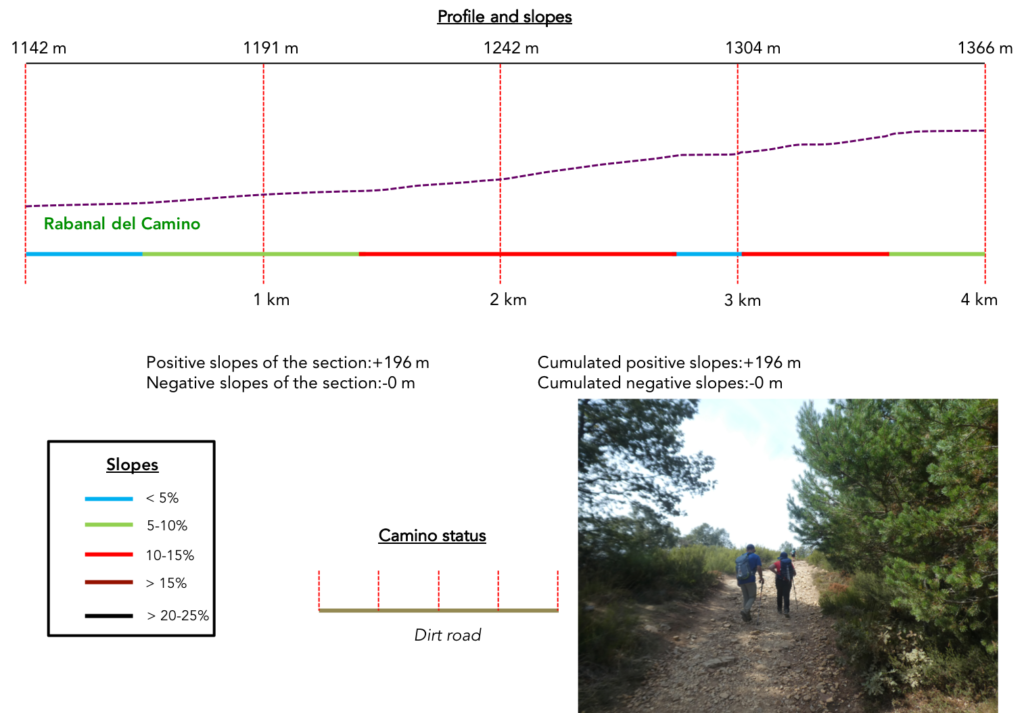

Section 1: On the way to Montes del León.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : slopes often more than 10% to reach Foncebadón.

| Foncebadón is 5 kilometers higher than Rabanal de Camino. Here you are already at the foot of the mountains of León. The Camino leaves Rabanal at the top of the village. |

|

|

| Today the weather is fine. |

|

|

| The pathway climbs steadily above the village. |

|

|

| The stony pathway will bump in the characteristic bushes of this whole region and the oaks lost in nature. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses the mountain road that goes towards Foncebadón, and begins to climb in the wild nature. |

|

|

| The ground here often turns ochre. It is an arid, dry land where dry grass alternates with low clumps of broom, lavender and cypress, which somehow succeed in the sunny climate that must reign over these hills. Humidity should not haunt these places, and you will probably never see moss around here, although the ferns grow. |

|

|

| But, the hill still remains a little civilized. In fact, there is a picnic spot. For who? You won’t often see pilgrims unpacking their wares in these places. It must be said that they rarely run by here at noon. |

|

|

| There are only oaks that cling to the hill and vegetate on this ungrateful land. Further up, the slope increases to more than 15%. You have to cling here, because you see the pass road running above. |

|

|

| One more thrust, and it’s on the road. Cyclists do not pass on this pathway. They will continue wisely on the road. |

|

|

| The pathway then continues its climb in a space that sometimes resembles scree. Often the pilgrim is a convict breaking his daily ration of pebbles. Here, it is the domain of limestone, with its harsh landscapes, with few trees, except oaks or stunted pines that grow here and there. Below, the pass road zigzags through wild pines and cypresses. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway becomes civilized again, passing through more abundant vegetation. Sometimes real pilgrims pass by with heavy bags. These are becoming more and more an exception. As we have already said, the Camino de Compostela tends to become more and more a Club Med where walkers take care of themselves with the minimum, having their luggage transported. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway pauses near a fountain where clear water flows… |

|

|

| … then set off again on the stony slope. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway again approaches the pass road in the oaks. |

|

|

| Then, the slope increases again. So, the athletes, loaded or not, are sure to overtake you, it’s written in advance. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway encounters slabs of glossy shale, for a short time. Nature is beautiful and wild here, on this steep side where garlands of wild plants run.. |

|

|

| Soon, you’ll see at the top of the mountain communication antennas and the slope softens a little… |

|

|

| …but it’s to start again a little up. On this pathway, the slope is continuous but never constant. |

|

|

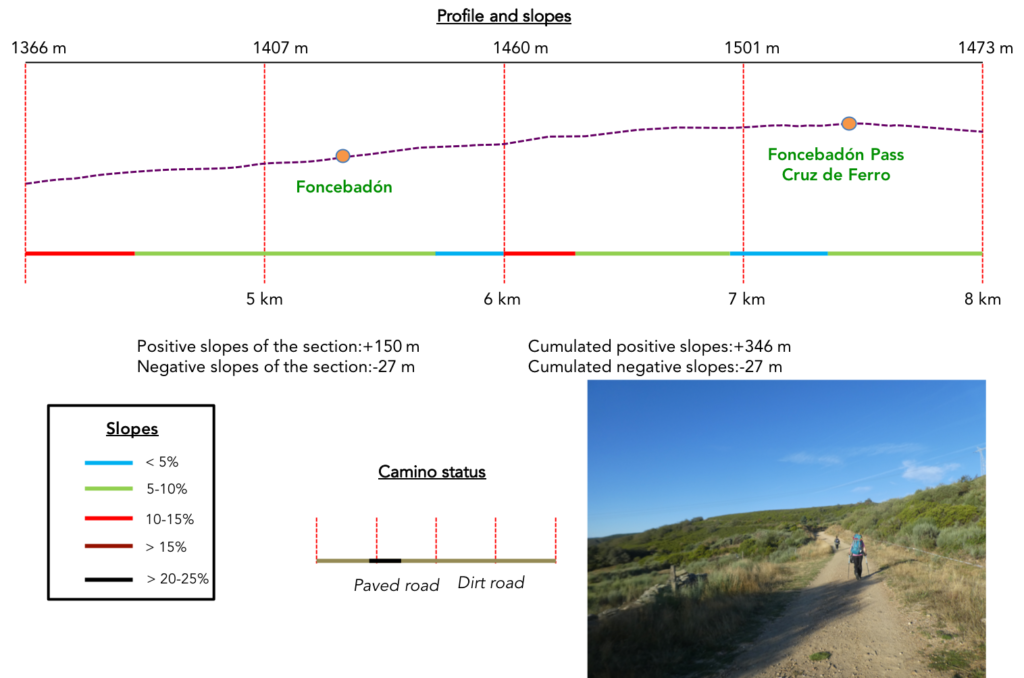

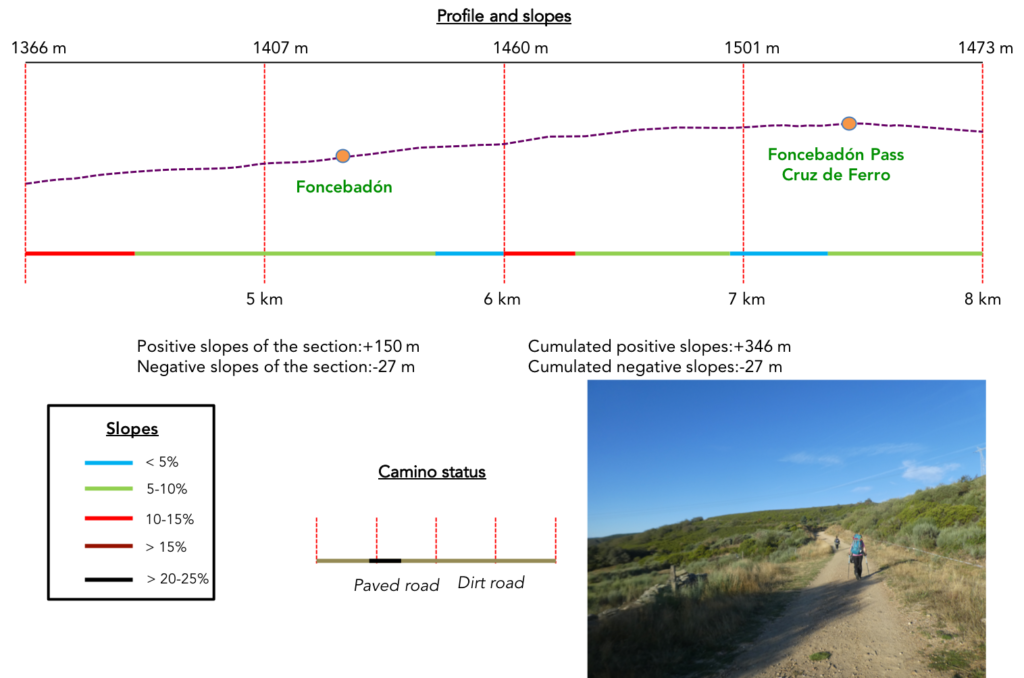

Section 2: On the way to the Cruz de Ferro.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : constantly uphill, with often more reasonable slopes.

| Further up, a little corner of paradise, a carpet of purple heather and green cypress colonizes the shale and catches our eye. |

|

|

Wherever you look in the valley, only forests fill the space.

| Further up, the steep climb comes to an end, and soon you have in the near horizon the road that zigzags towards Foncebadón. |

|

|

| There is still a picnic spot here. For whom, one wonders, the village is a stone’s throw away. The pathway then approaches the road, but does not follow it. |

|

|

| So, another demanding and pretty ramp on the stony pathway… |

|

|

| …and the Camino disembarks under the village. Foncebadón is a very small village on the slope of Mount Irago. Foncebadón is the last village of the Maragatería. The first documentation of the village dates back to the Council of Monte Irago in the Xth century, during which the Bishop of Astorga gathered together all the abbots, priests and deacons of the diocese, to solve the problem of the constant thefts and murders committed on the route of the Camino. On this mountain, bandits prowled taking advantage of the rough terrain and the usual bad weather from October to April, with lots of thick fog and snow. |

|

|

| At the height of the Camino in the XIIth century, Foncebadón had its own pilgrim hospital, hospice and church built shortly before by the hermit Guacelmo. The XIth century church later became an abbey. But, it was devastated during the War of Independence (1808-1814) and had to be rebuilt. At the end of the XIXth century, the construction of railways and new roads in the region led to the decline of the village. In the 1960s and 1970s, many residents migrated in search of employment. In the 1990s, there were only 2 people, a mother and her son, living among the ruins. Today most of the houses are abandoned, but this semi-abandoned village comes back to life with the revival of the Camino. As for the other “pueblo-calle” of the region, the street that crosses the city is called Calle Real. |

|

|

| You are definitely not going to plan your next vacation here. You will have to organize your leisure time if, as some have done, they have taken a step ahead of their comrades who have stopped below, at Rabanal del Camino, for the next day. |

|

|

Of what the hermit Gaucelmo built, who dedicated his life to the care of pilgrims, there is not much left, except the dilapidated church of Santa María Magdalena in honor of the patron saint of the village, which requires some improvements.

In 1991, Foncebadón being practically uninhabited, the Bishop of Astorga decided to remove the bells from the Church de Santa María Magdalena and transfer them to the Museum of the Way of Astorga. On the appointed day, the people in charge of the task arrived in the village. María, the old mountain woman who, together with her son, were the only inhabitants of the village, welcomed them. She was perched on the roof near the belfry and brandished a stick, shouting that they should leave the village without the bells, which were to remain there to warn people if a fire was discovered in the village or to guide pilgrims in the fog. The men were so surprised by María’s attitude that they left without them.

| The pathway leaves the village behind the ruins of the church. Up there behind the green hills dance the wind turbines planted on the ridges of the mountains of León. |

|

|

The effort is less demanding when you cross such beautiful landscapes.

| Here is what remains of the hermit’s monastery. It’s not much, but it’s filled with emotion, all the same. When Foncebadón had to be rebuilt after being completely destroyed during the War of Independence (1808-1814), it was moved slightly to the east; thus, what appears are the remains of a belfry from the tower of the old church. |

|

|

| Nature is graceful and divine here, in a moor where broom, heather and wild cypresses run along stonewalls. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope becomes more demanding in the moor, and the pebbles sometimes roll under the soles. |

|

|

| Today, wind turbines will not buzz in your ears. They will swing away. But all the mountains here are covered with them. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope is much gentler and you can see the pine forests emerging. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway crosses the road of the pass, which crosses the Maragateria, this road that you know well from Astorga. |

|

|

| You are now 236 kilometers to Santiago, and the pathway slopes up above the road in the brittle and lustrous shales. |

|

|

| The pathway then wanders delightfully above the road. |

|

|

| Tall grass and pines accompany you as if to go in procession towards the Cruz de Ferro. |

|

|

| Soon it appears before you, tall and simple at the end of the track. The emblematic Cruz de Ferro stands on top of a pebble mound which could be of Celtic origin, since at that time it was customary to build stone mounds at the highest, strategic and symbolic points of a road. Some say it was here that the Celts erected an altar to the Roman god Mercury. Others believe that its origin could be due to the milestones that marked the territorial limits in Roman times. Whatever its true origin, this custom would have been Christianized by the hermit Guacelmo, founder of the Abbey of Foncebadón, when he placed a cross on top of the mound at the end of the XIth century. |

|

|

| You sometimes have to wait long minutes to be able to fix it on film, alone, with integrity, because an army of pilgrims spends the time coming to be photographed, as if nailed to the post of the cross for eternity. What derision!

We stayed here almost half an hour to do our little statistics. No pilgrim has placed a pebble today. It must be said that on the Spanish Way of Compostela, three-quarters of the pilgrims travel with a small bag, and there is therefore hardly any room to slip a pebble into it. Still, this shapeless heap is undeniably charming, full of meaning and mystery. Don Quixote and Sancho Pansa stand guard there. |

|

|

| In the 1980s, a chapel dedicated to St Jacques and a fountain were built nearby. This is often where pilgrims leave their written messages, when they have them. Here you are at the Foncebadón pass, also called Puerto Irago, at 1,504 meters above sea level, the highest point of the Camino francés, even higher than the Lepoeder pass, on the road to Roncesvalles, which is not is only 1,410 meters above sea level.

The pass separates the Maragatería from the Bierzo. Monte Teleno, the highest mountain of the Montes de León, at 2,188 m, dominates it. It was the sacred mountain of the Asturian tribes who inhabited these lands before the Roman conquest. Monte Teleno is a mountain with a gentle profile, with rounded hills and moorland at the top. The peak is in the center of the Sierra del Teleno, which runs northwest to southeast, serving as a natural border between the regions of La Cabrera, Maragatería and Bierzo. It is said that hundreds of muleteers and pilgrims were killed by brigands, attacked by wolves, or lost in the middle of a blizzard, on Monte Teleno. Today, everything is safe here. |

|

|

| Beyond the pass, the Camino gently slopes down next to the road. |

|

|

| It’s a dirt road, sometimes quite stony, along rows of tight pines with here and there a mountain ash that stands out. |

|

|

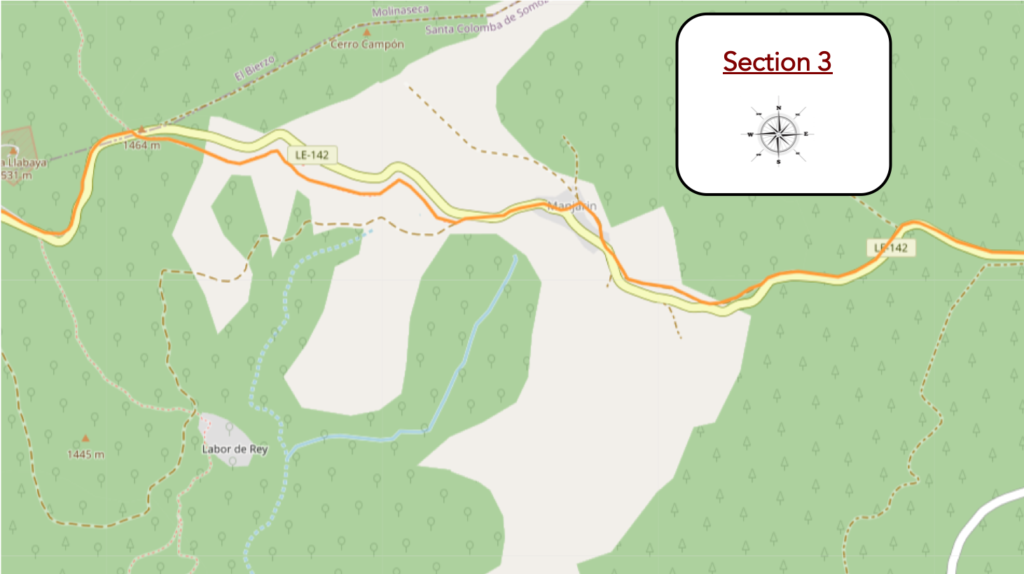

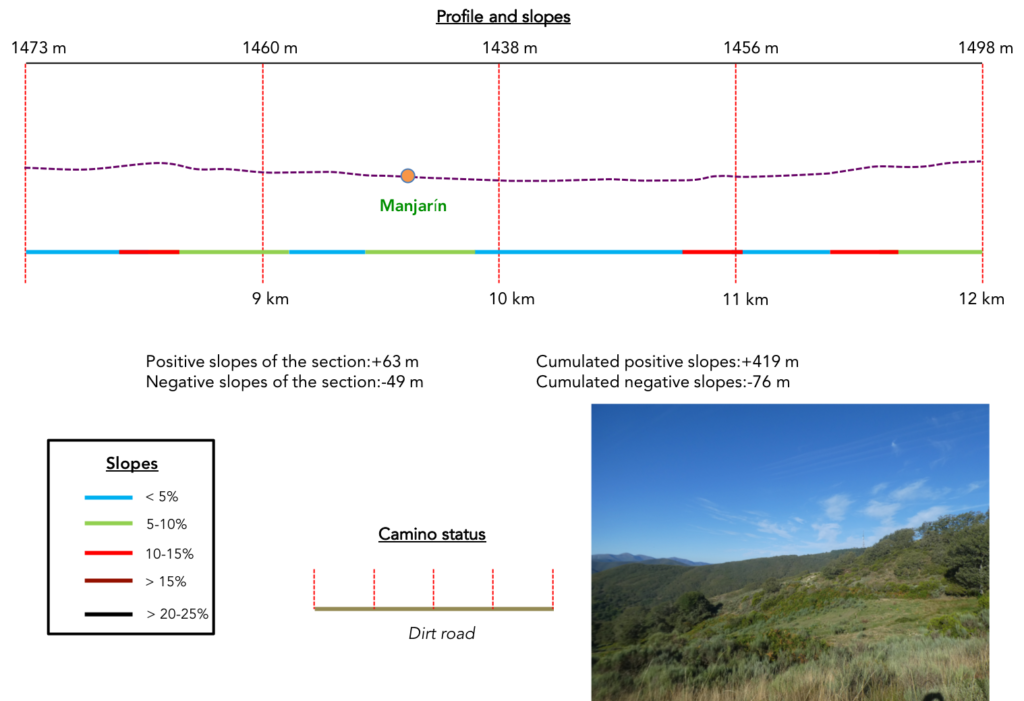

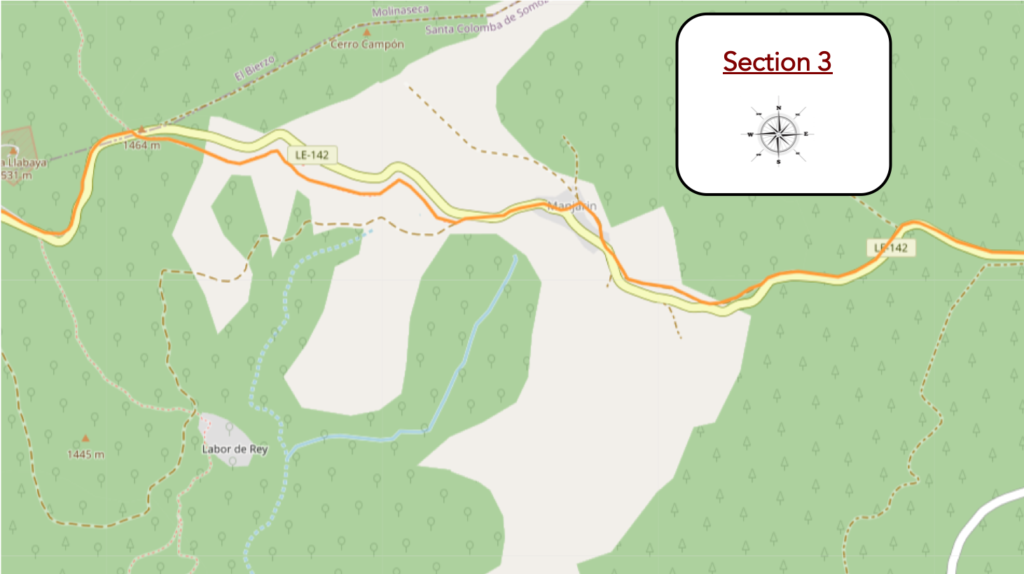

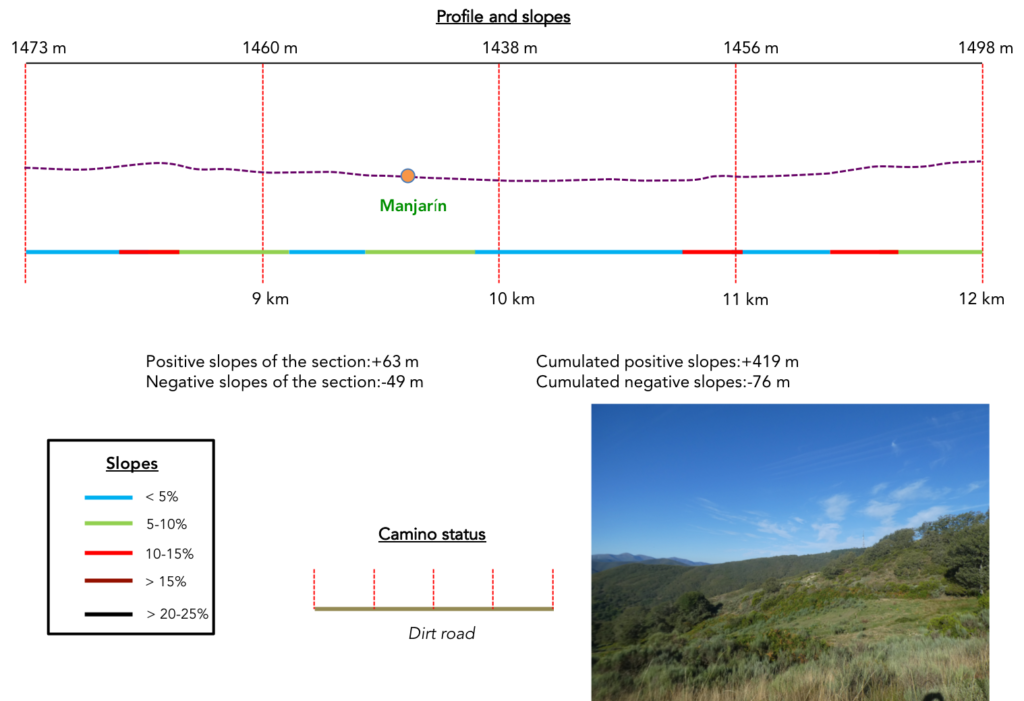

Section 3: Gorgeous ripples in the wilderness.

General overview of the difficulties of the route/u> : with often slightly steeper slopes.

| The pathway follows the gently sloping road for quite a long time. Traffic is derisory on the axis. |

|

|

| The route is marked with stakes for the winter. The snow must be abundant here. |

|

|

| Further down, beyond a wooden cross, the pathway runs under the road in the undergrowth. Here grow rowans, oaks, maples and also some poplars. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway nods a little more, climbs more toughly towards the road. |

|

|

| However, it remains on the same side of the road, and begins a slight descent towards Manjarín. |

|

|

On the horizon, on the hills, wind turbines rise like the masts of ships. Who dares claim that wind turbines make landscapes ugly? In Spain, when they play with the wind in the distance, they are very elegant. But, it is better to observe them from afar. There, they do not disturb anyone, except the birds.

| Just below is Manjarín, an abandoned hamlet, but which maintains local activity in an adorable bric-a-brac run by Tomás, one of the famous characters on the way.

There were mines here in Roman times. The village was founded in the IXth century. In the XIth century, it developed thanks to the monk Guacelmo, who built a hostel for pilgrims. A pilgrim hospital run by the Templars existed here as early as the XIIth century. The village was completely abandoned at the beginning of the IXth century. With the decline of the Camino de Santiago and the arrival of the railway and industry, people began to move to the cities. It was uninhabited from the late 1970s until the arrival in 1993 of Tomás, a hermit from Madrid. Today, he and an assistant are the only villagers. He is a modern knight hospitalero who operates the “albergue” in an abandoned house that he has renovated. He sometimes disguises himself as a Knight Templar for his visitors. Outside the “albergue”, wooden boards indicate the distances to various places in the world. There are only 3 or 4 houses left standing. Everything else is in ruins. |

|

|

| Seven kilometers separate Manjarín from El Acebo, a route that initially continues along the road. There is a bit of dirt on the side. But, the traffic is discreet on the pass. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway runs under the road. In front of you appear on the horizon on the hill the antennas of a military installation. |

|

|

| Ahead of you is a vast moor, an expanse of tall grass and grass, a landscape of sparse vegetation, punctuated by scattered bushes and disheveled grasses. You see that the pathway takes on the air of a snake that undulates in the distance. |

|

|

Shortly after, a fountain distills its fresh water into more abundant vegetation.

| Then, the moor is reborn, on a slightly more undulating relief, always wilder, in the boxwoods, the wild cypresses and the lavender burnt by the sun. Up there, the antennas are getting closer. |

|

|

| Further on, the slope becomes steeper, in the heather, when the pathway reaches the sometimes more compact forest. |

|

|

The pathway then crosses a space where the stocky holm oaks have taken over.

| Le chemin traverse alors un espace où les chênes verts trapus ont pris le pouvoir. |

|

|

| Now the antennae are growing visibly. |

|

|

Below, the hills are lost one after the other in the wildness. No one should set foot there.

| Further up, the pathway crosses the road to the pass, goes on the other side, 232 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

| It is then a beautiful walk under the august pines above the road. |

|

|

| But, do not imagine that track organizers will let you walk around without effort. Soon, the pathway will slope up on the stony pathway to say hello to the antenna. |

|

|

| Well, you’ve seen the antenna. Then, the pathway will slope down to the level of the pass road. Here is Punto Alto (1,515 m), a few meters higher than Puerto Irago. But, you even climbed higher than the pass. However, there is no reason to declare the Camino de Santiago as a high-altitude route! |

|

|

| Here you cross a road that goes up to the antenna. This is military land. With transmitting antennas. |

|

|

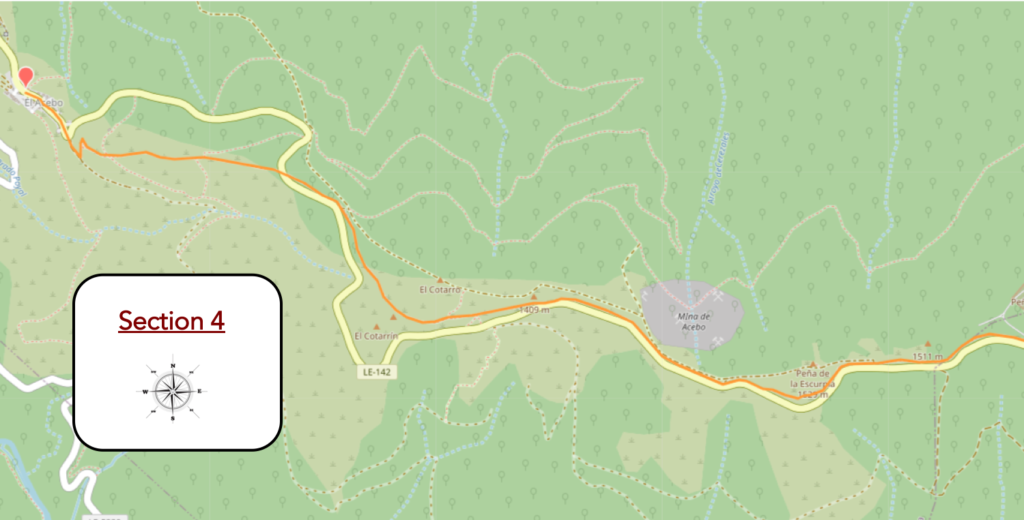

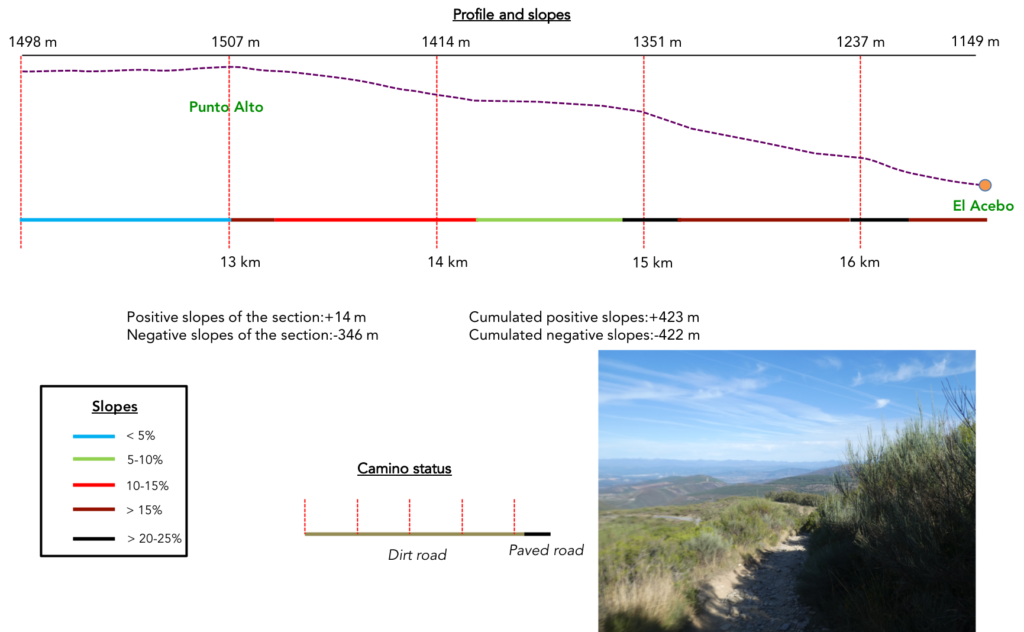

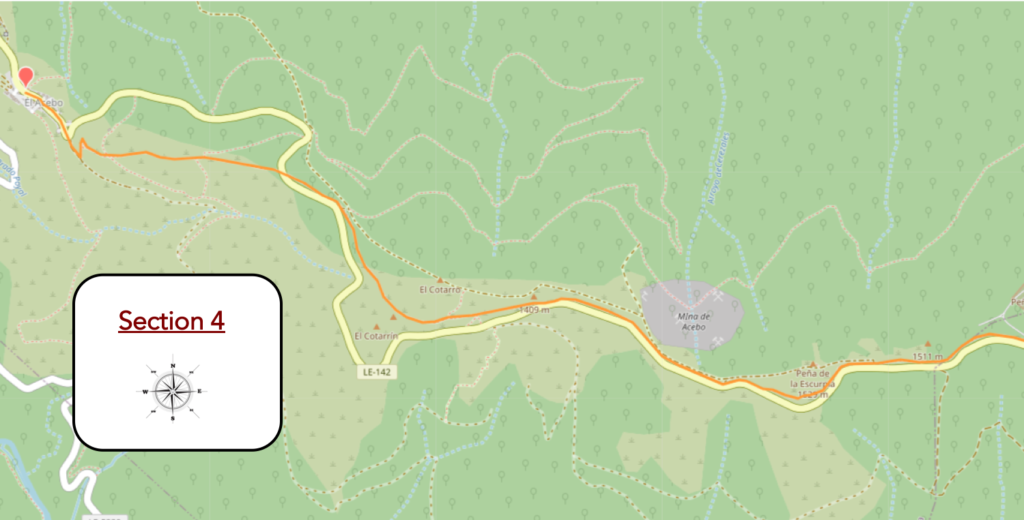

Section 4: A terrible descent to El Acebo.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : without problem at the start, then of the great sport

| Beyond the antennas, a beautiful pathway wanders through the moor, the heather and the cypresses above the road. |

|

|

| In these landscapes, the word big takes on its full meaning. |

|

|

| It is a magical moment, an almost perfect work that only nature can do. |

|

|

| You can’t get enough of a landscape that looks like it came straight out of a painting. |

|

|

| The pathway climbs a little higher in the greenery… |

|

|

| … before softening on the side of the ridge. Over there, the wind turbines are watching you. |

|

|

| From there, everything changes. The landscape becomes as beautiful as it is tortured. The laughs are over. It will slope down more and more toughly. You then make a first acquaintance with the scree that is the track, which descends to join the road to the pass. The scree is shale and large limestone pebbles. It is often a morainic material. The glaciers must have passed through there in the past. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway tumbles for a long time in the scree. The brittle and lustrous shales groan under your feet. And you too. Walking then becomes demanding and unsafe. With each step, the risk of tripping increases. Admittedly, it is not hell but it looks a bit like it. However, the muleteers of yesteryear probably also passed through here. |

|

|

| So, a little advice here. You see the road below. And to shorten the torture, you can just as well leave the scree and go down the road for a while. At least until the first corner. Thereafter, return to the pathway, because you never know where the road may lead you. |

|

|

| Further down, you will enjoy a well-deserved break. The pathway drags on the ridge. Here, a pilgrim must have thought that it was more comfortable to walk barefoot. |

|

|

| And the break goes on for quite a long time on the edge of the ridge, in the rough vegetation. |

|

|

| Below, on the road, you don’t see any vehicles, but the cyclists of the Camino de Compostela who rush, their noses in the handlebars. |

|

|

| Then everything will speed up again. You then see Ponferrada below on the horizon, in the plain of Bierzo. |

|

|

| Here, for fun, the slope will easily exceed 30%, and the stones have not disappeared. The vegetation is so rough that you can even see gorse. You could imagine yourself on the cliffs of Brittany. |

|

|

| Then you hear the pebbles groaning behind you. The muffled sound is getting closer. A cyclist descends the scree. This one won’t have a chance. A few meters below, he will be ejected from his machine. But that won’t stop him from continuing his hard work. |

|

|

| Further down, it’s calm, and the pathway gets closer to the road again… |

|

|

| …to get off to a better start on the descent. Below, the valley opens more and more. On the horizon, it is still the mountains of León, which rise behind the plain of Bierzo. |

|

|

| Further ahead down, the pathway crosses the road. An inn is announced, 1200 meters away. Nirvana, right? |

|

|

| And you’ll see the pathway calm down on the ridge. You got out of the infernal slide that swallows you, right? |

|

|

| But, do not rejoice too quickly, because in front of you the slope increases again. There is a small advantage here. You may prefer dirt to pebbles. |

|

|

| Further down is happiness, as the black slate roofs of El Acebo appear. But, to get there, it is not a pathway covered with roses. This is practiced on a slope that sometimes exceeds 30%. |

|

|

| Further down, it is a steep, but more reasonable pathway that leads you to the village. |

|

|

| Here, you will have time to treat your sores, your blisters, your sprains and your tendinitis. But, still consider booking if you want to spend the night here, in this little paradise. El Acebo, which means holly, is still a “pueblo-calle” with a main street, still called Calle Real. The road is canalized, which must indicate very frequent rains in this sloping village. |

|

/td> /td> |

| El Acebo is a beautiful village. It looks like a mountain village, such as you encounter in the Alps of Italy or Switzerland, with gleaming black slate roofs and wooden bacon. Here, it is the end of the poor adobe and brick houses of Castile. It breathes stone, solidity, to resist the winter climate. As in the previous villages, El Acebo once had many houses in ruins. However, in recent years, as tourism and the popularity of the Camino has increased, it has brought in money and people have returned to live here. |

|

|

| The Romanesque parish church of San Miguel, from the XIIth century, is located at the end of the village. Even the church is worth a visit, as it is open. |

|

|

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 6: From El Acebo to Ponferrada |

|

|

Back to menu |

/td>

/td>