A first learning about the “Meseta”

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

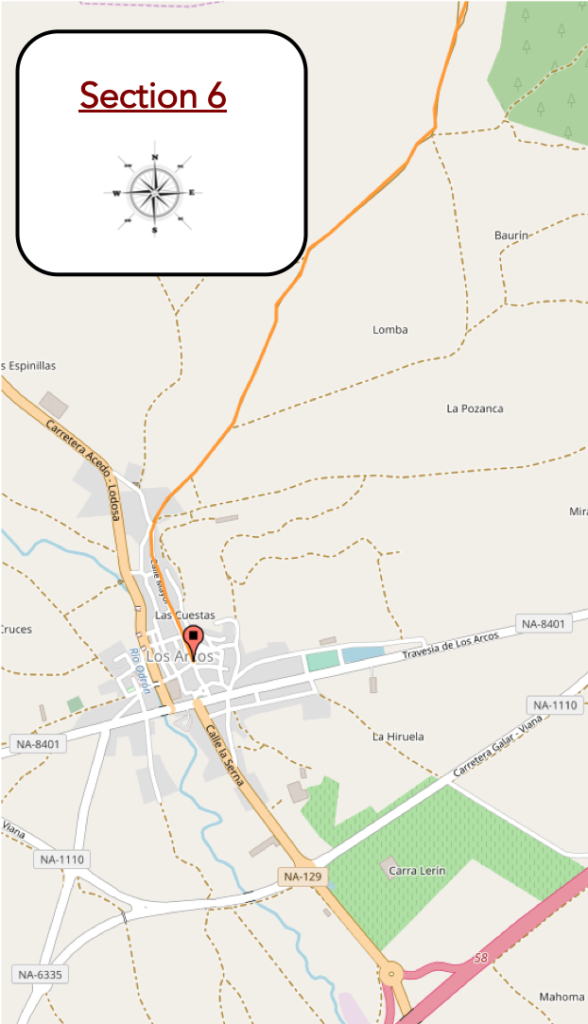

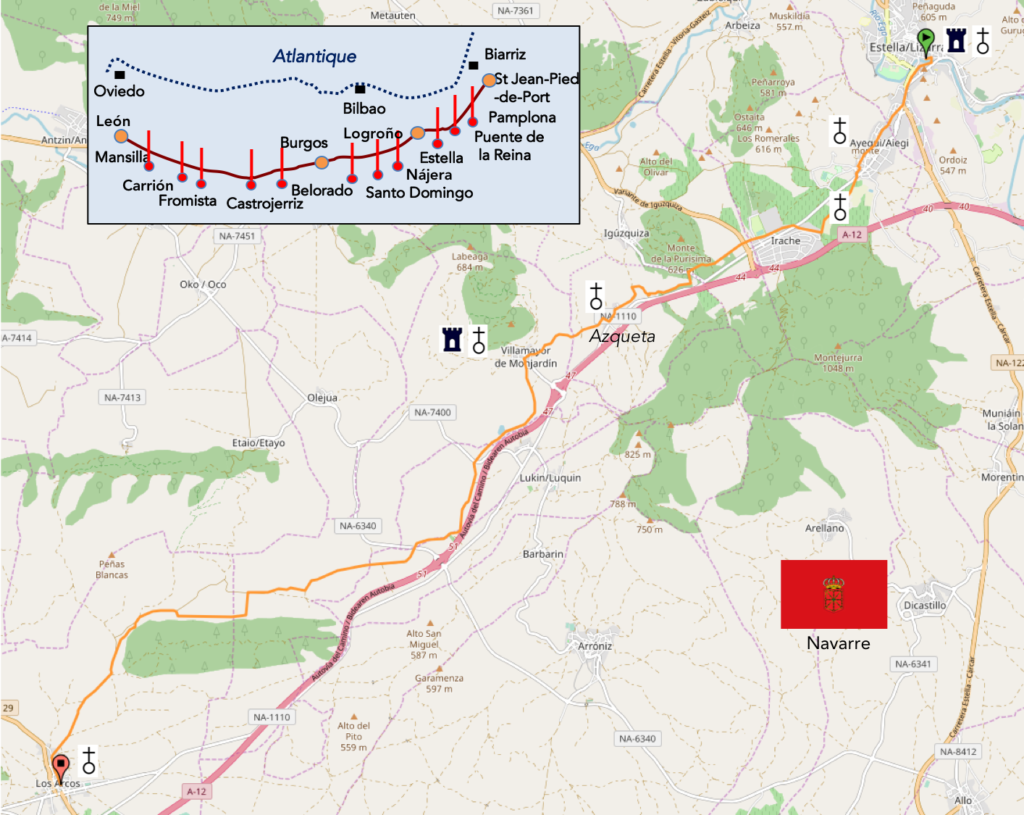

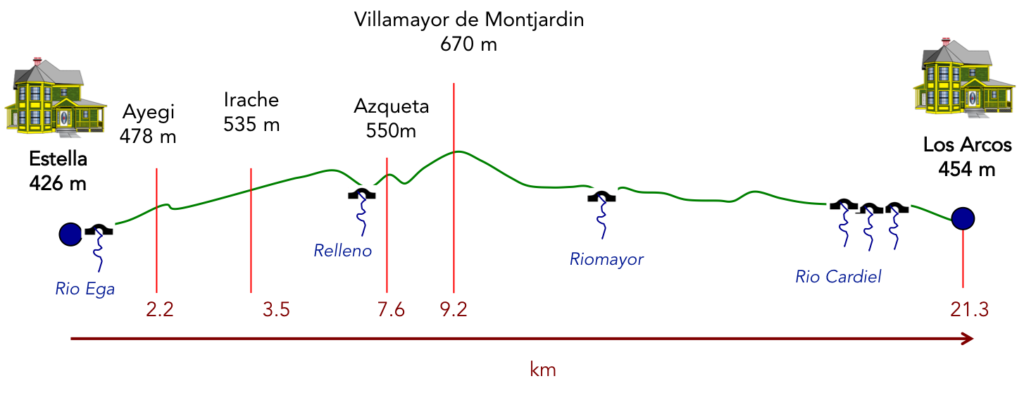

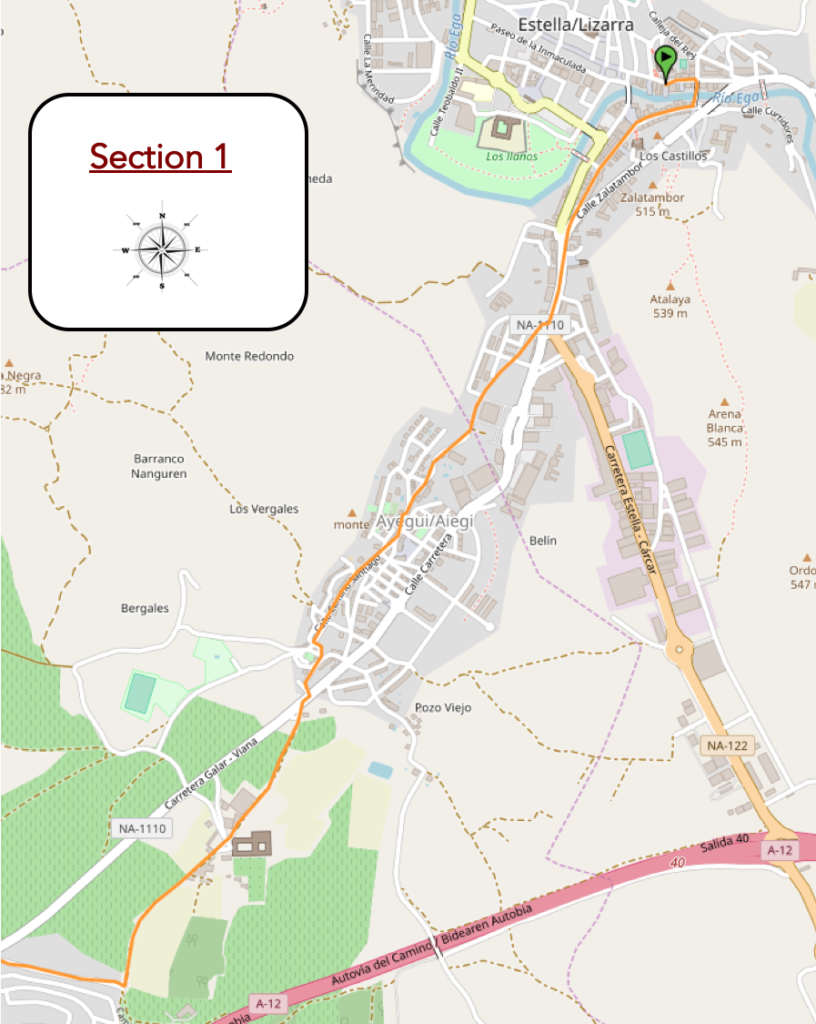

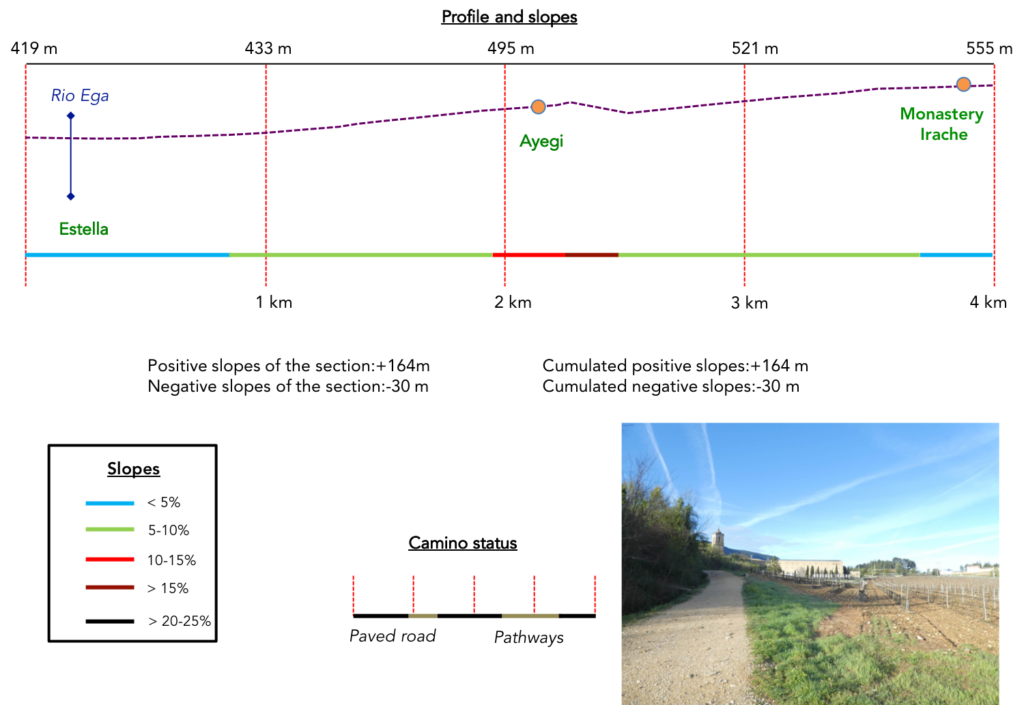

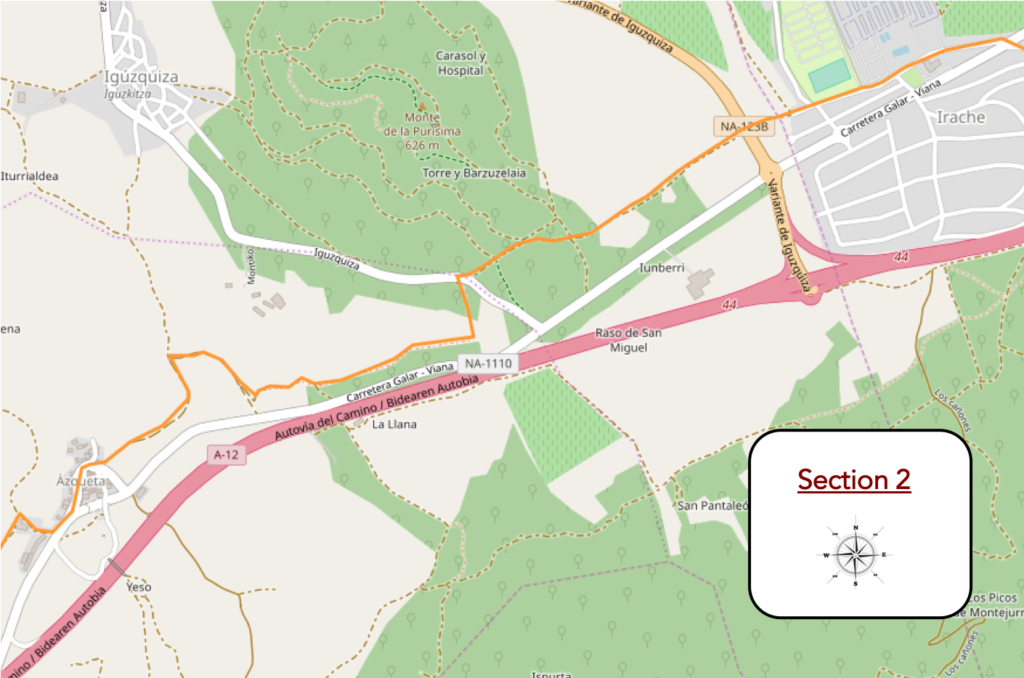

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-estella-lizarra-a-los-arcos-par-le-camino-frances-33669770

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

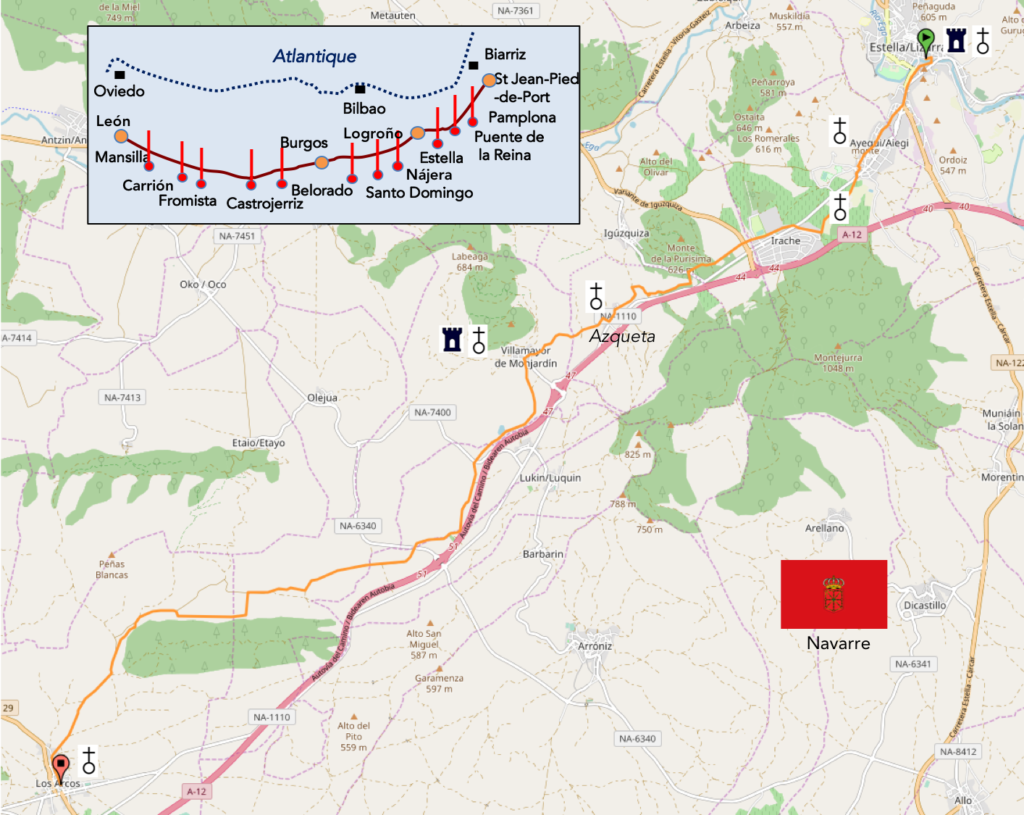

Navarre is a fairly composite country, at least where the path goes. After crossing the beautiful beech and pine forests at the start of the track into valleys and high hills, the landscape has changed in recent days. We are now very far from the Pyrenees and Navarre extends in the Meseta, this huge plateau that covers more than half of Spain. This is obviously less stimulating for the vast majority of pilgrims, who see this change as an evil eye. The stage of the day is a little sister to the previous one, but the stages are not all alike. It depends on the height of the hills and the extent of the forests, when there are any. For the rest, it is a monotony that will become usual, endless grain fields, a complete lack of life outside the villages. When you’ll cross the villages, you have the feeling that they are there only for pilgrims, local people mostly absent, probably caulked in their homes, because during this cold and rainy spring, we did not meet any peasant in the fields for three weeks.

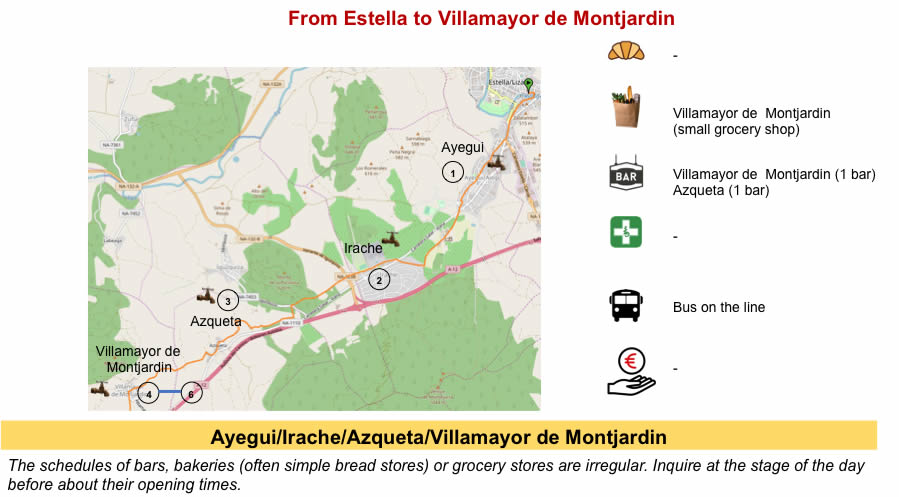

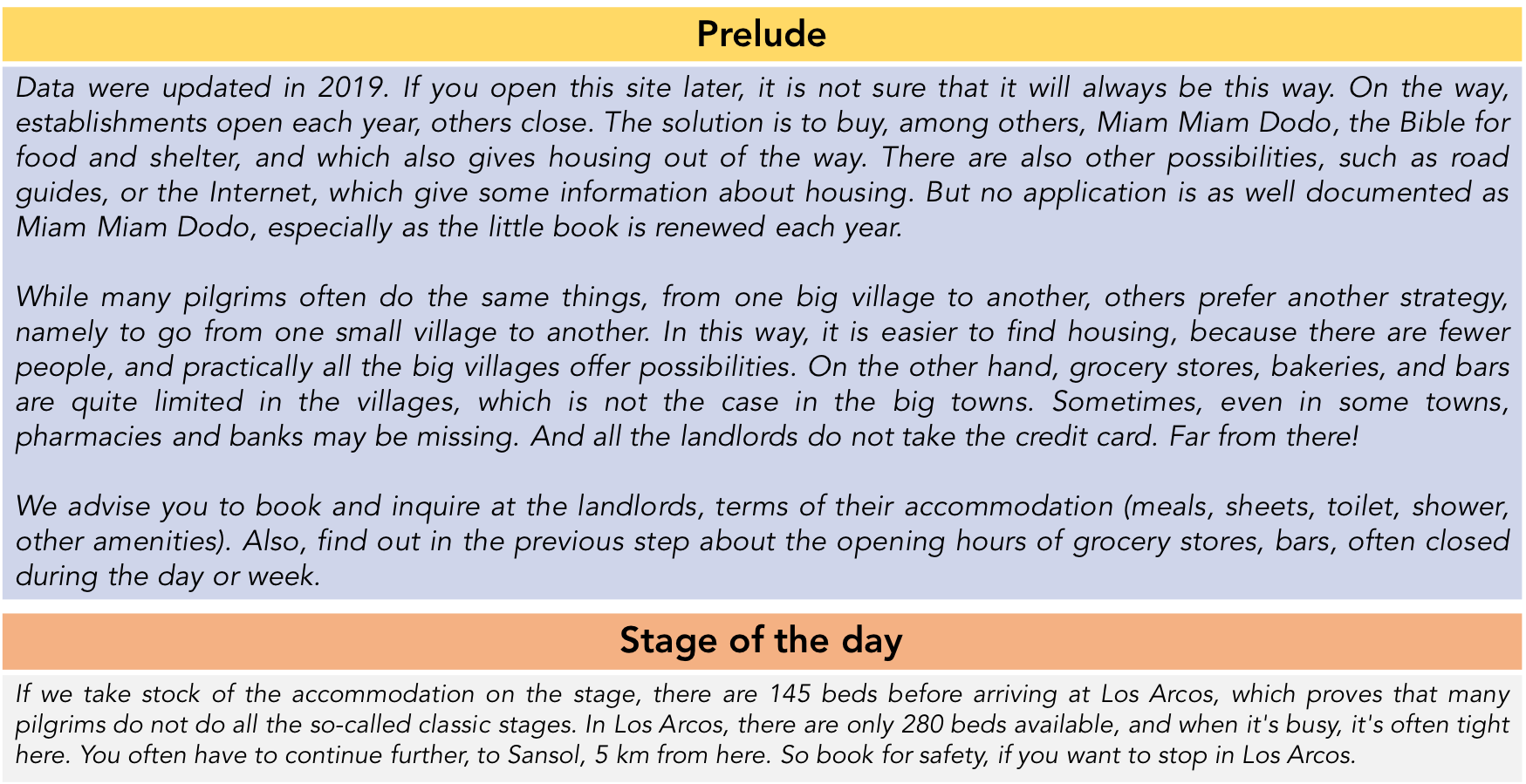

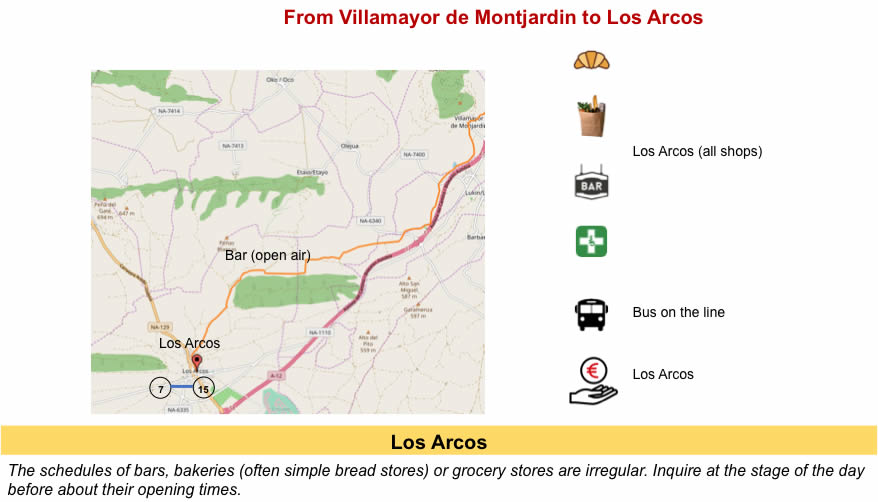

Today, you’ll drink gratis at the cellars of Irache. All pilgrims have spoken extensively about that in the “albergue” at night. The life of pilgrims is often made of little things. Then after a day in the Meseta, arriving at Los Arcos, it will still be necessary to occupy his spare time. There is nothing to do, except to sip a drink in the square, or hurry to find the only grocery in the village, to refuel before others. When you are told that the life of pilgrims is sometimes made of little things.

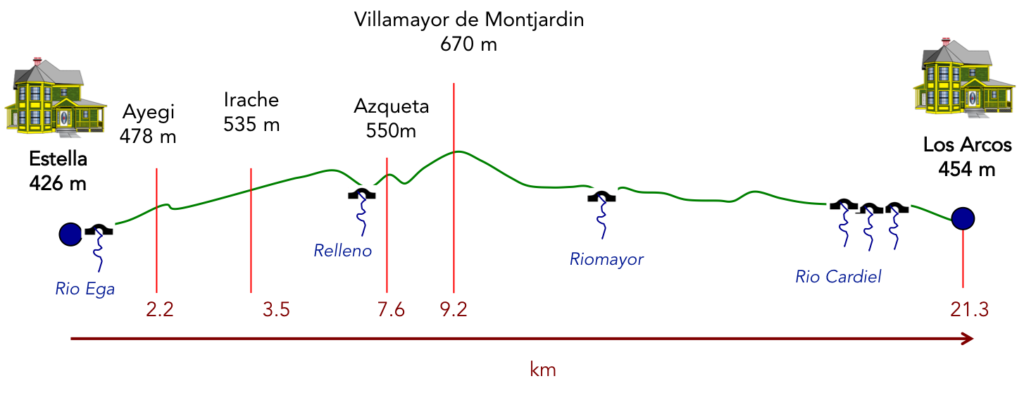

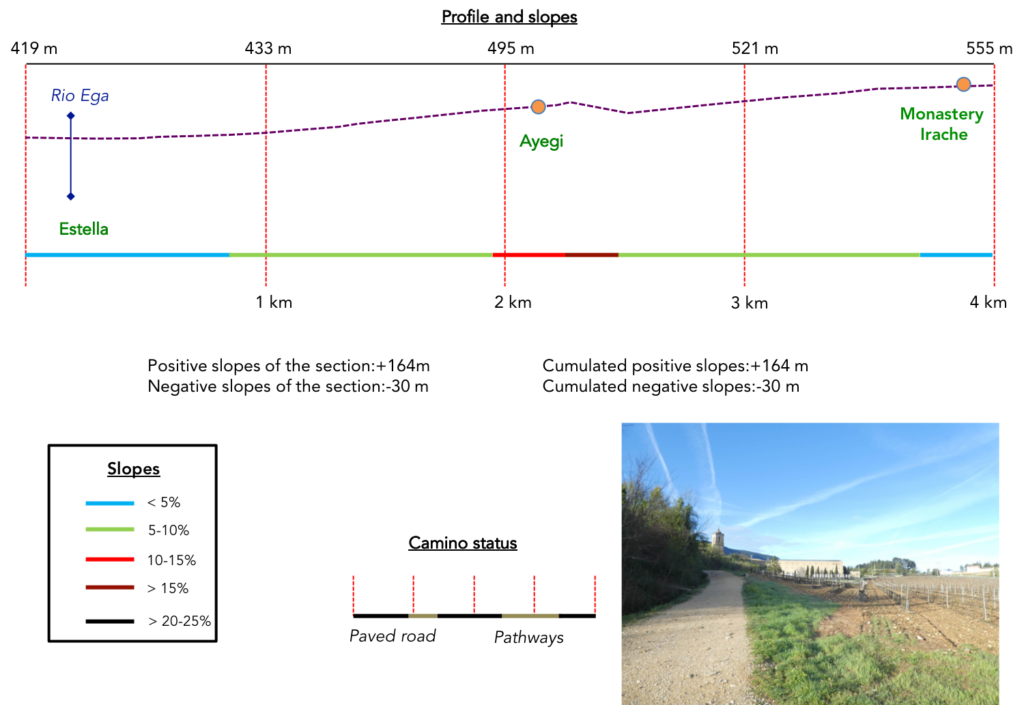

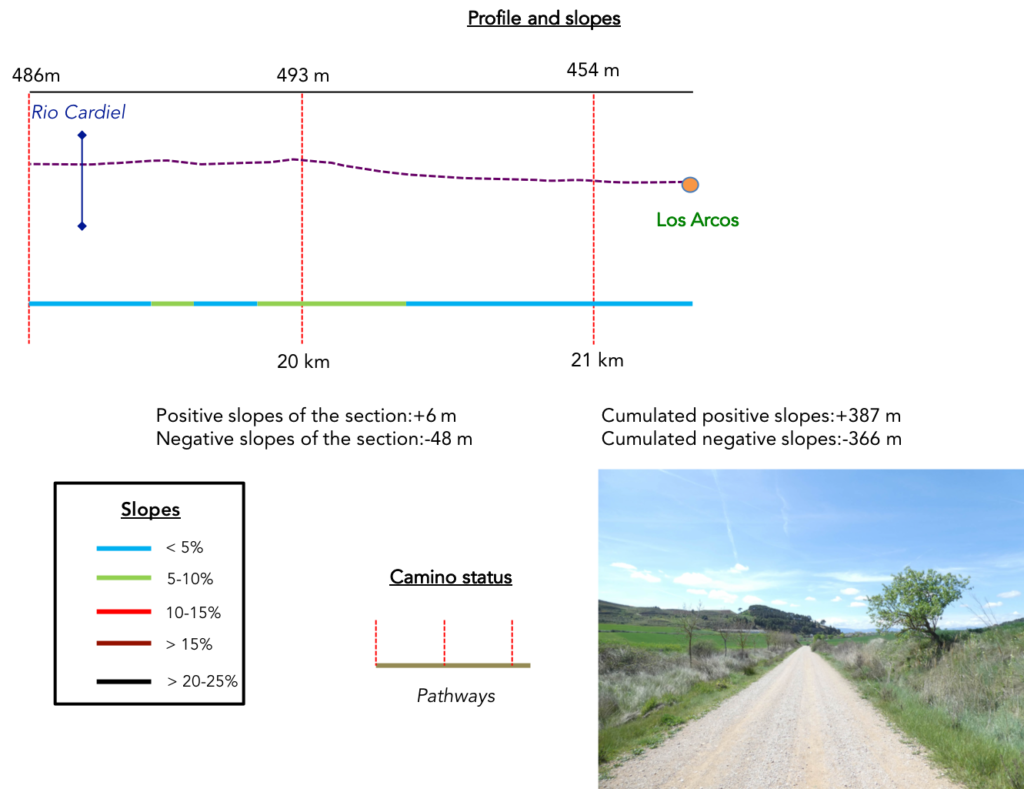

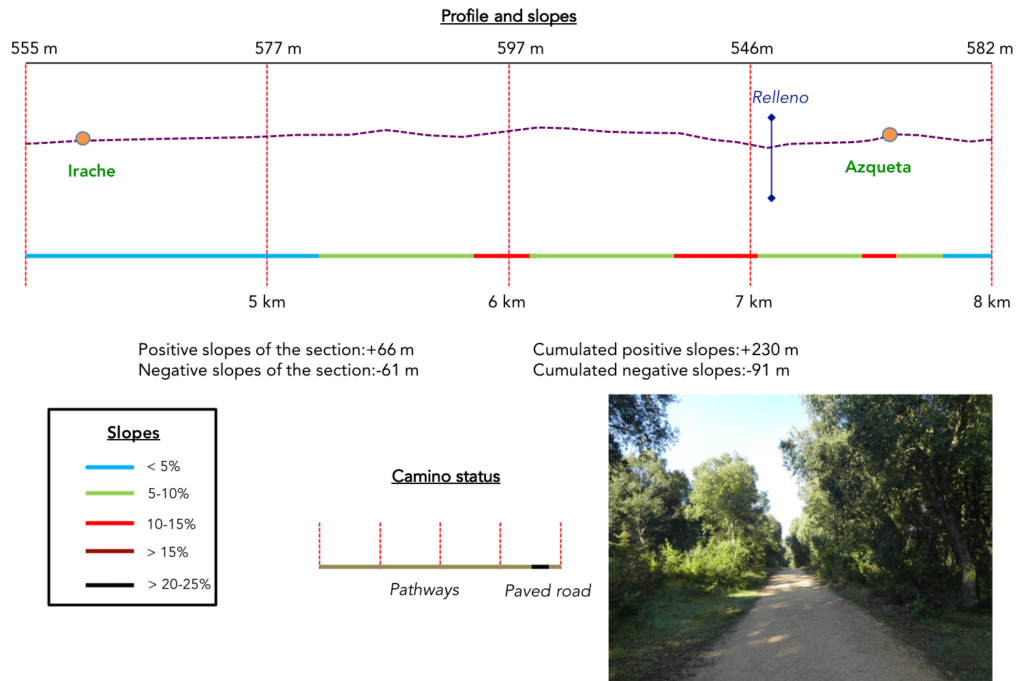

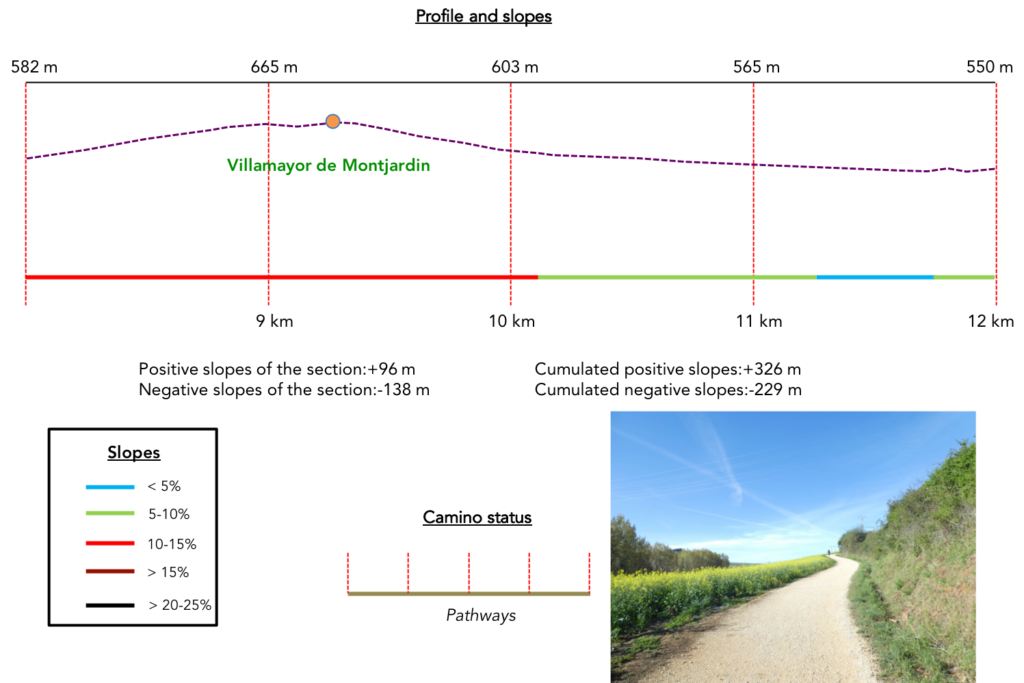

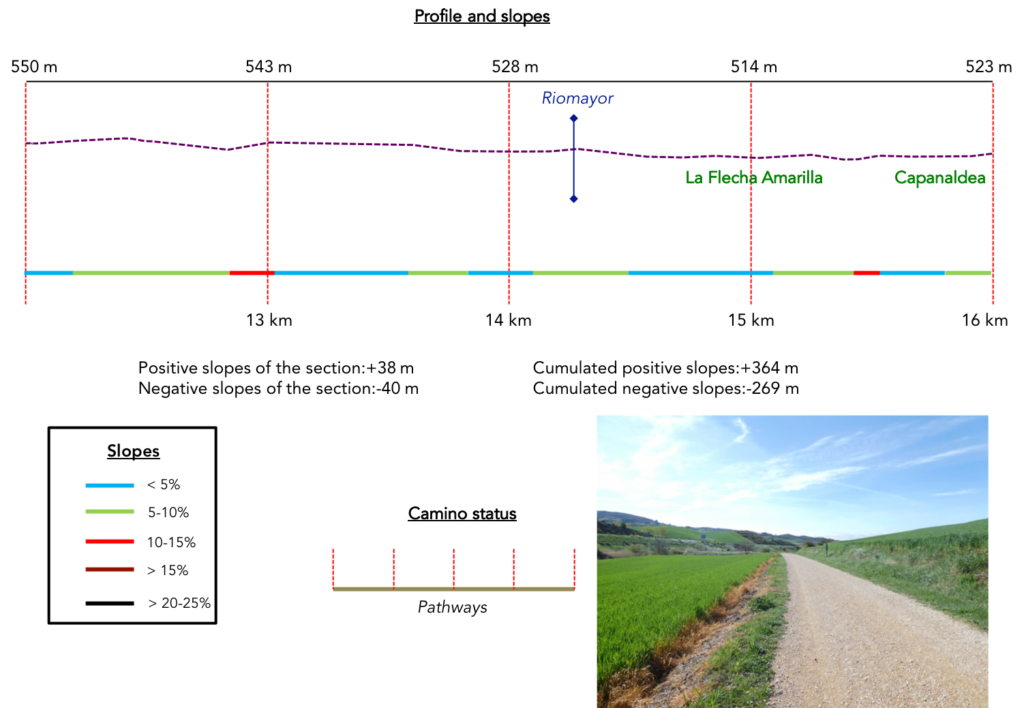

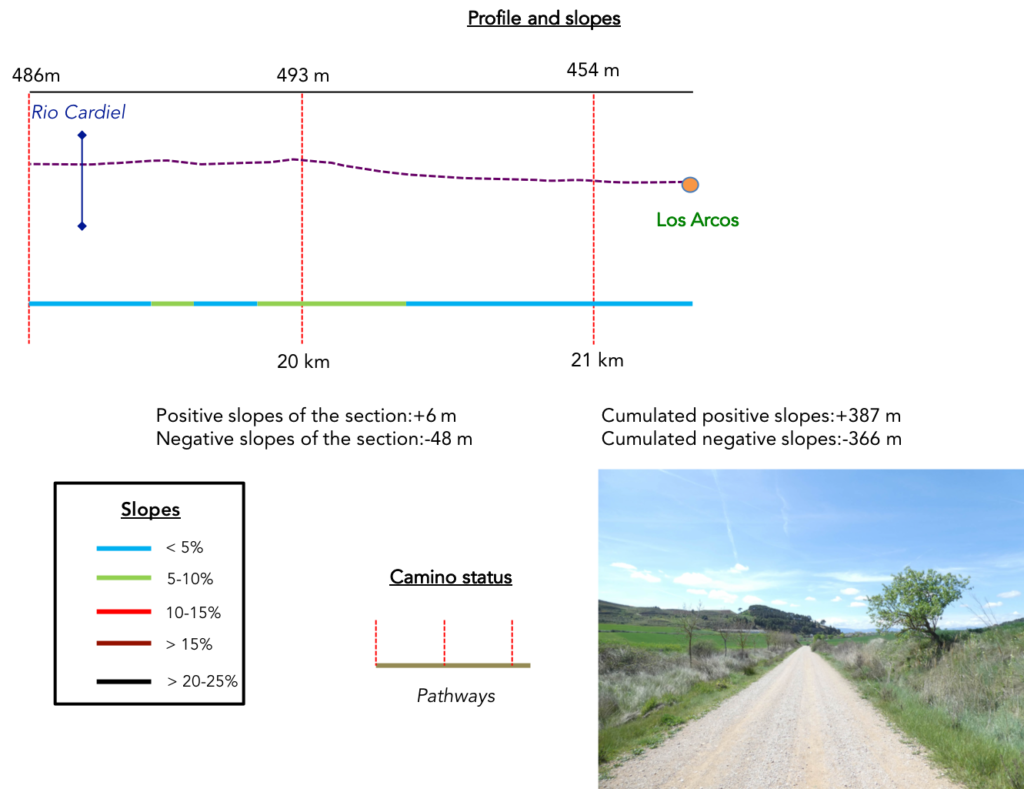

Difficulty of the course : Slope variations of the day (+387 meters /-366 meters) are light. There are only two passages where you will be asked a slight effort, first at first the gradual climb to the Monastery of Irache, then especially the passage to Villamayor de Montjardin, where the slope is tough, uphill and downhill. All the rest is just a ride on wide pathways that often look like highways.

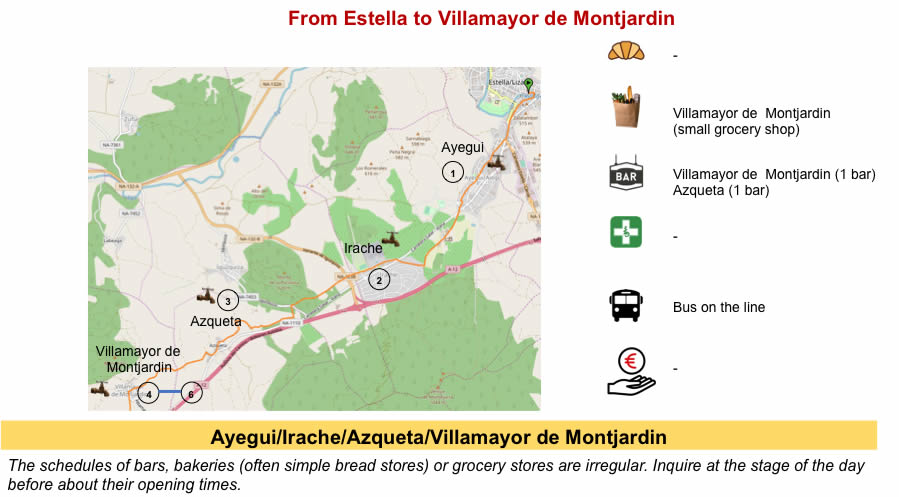

In this stage, the course is almost entirely on dirt roads. The passages on the paved road are only in the villages. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 2.9 km

- Dirt roads: 18.4 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

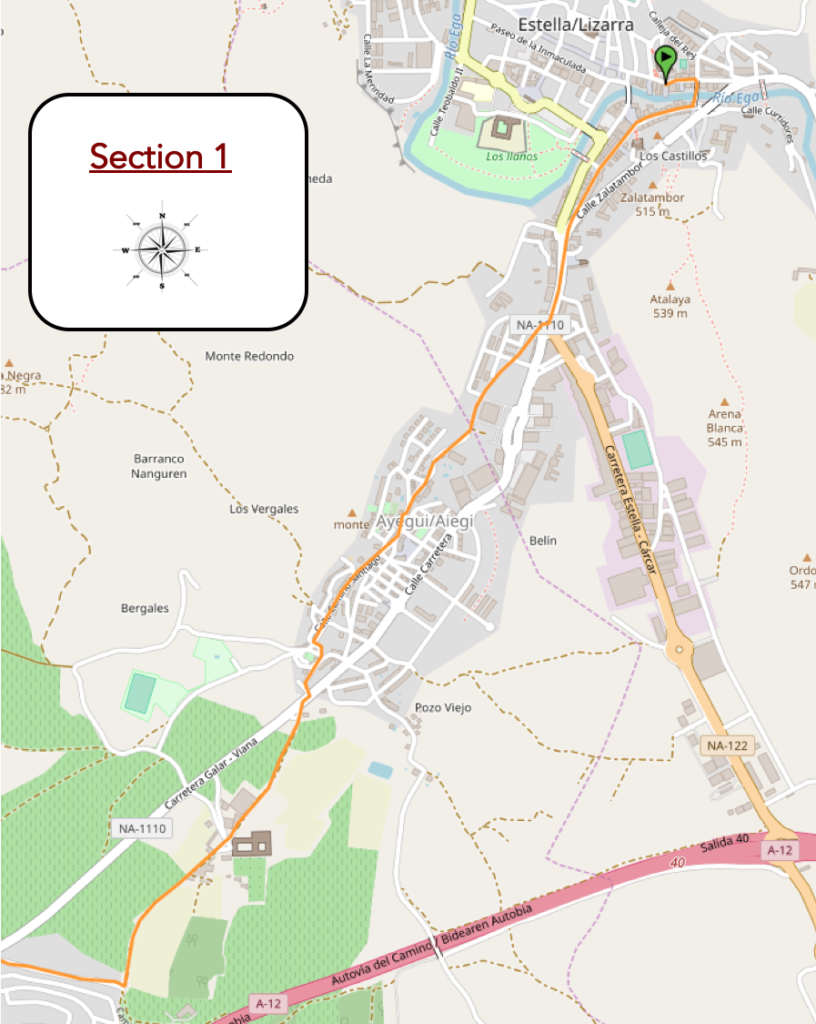

Section 1: Cheers! here’s to you!

Overview of the difficulties of the route: almost continuous uphill with reasonable slopes, if not tougher around Ayegi.

| To leave Estella from the city center, it is best to start at the railway station, cross the river and reach the Tourist Office, near the Palace of the Kings of Navarre. |

|

|

| The Camino runs up Calle San Nicolás and passes under San Nicolás Gate or Porte de Castilla, a XVIth century gate, which is believed to have been put in place during the visit of King Philip II of Castile in the XVIth century. This is all that remains of the walls of the city. |

|

|

| The Camino then crosses part of the new town, passes in front of the convent of the Capuchins, now transformed into a pilgrim’s inn. The “albergue” is next to the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Rocamadour. This church, like all the others of the city dates back to the XIIth century. Then, it was transformed to become baroque in the XVIth century. As in Rocamadour, in France, the church houses a virgin and child. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the Camino leaves the new city for the suburbs. |

|

|

| It soon follows a paved road that gently climbs gently towards the village of Ayegi. |

|

|

| It crosses a village in length. The slope becomes tougher the more you climb in the village. Here, a pilgrim carries his equipment on a trolley with wide wheels. Not sure that this way of doing things is easier than the bag on the back. |

|

|

There is almost a kilometer of walking from the bottom to the top of the village.

| Shortly after, the paved road steeply slopes down from the hill to the national NA-1100 road. In front of you stands the monastery of Irache. |

|

|

| After crossing the national road, a dirt road climbs to the cellars of Irache. Here, it is not advertising that is lacking to announce that you can wash your mouth out at the fountain. |

|

|

| The cellar is slightly above. |

|

|

| A crowd formed upstream. |

|

|

| And for good reason. Here is the famous Fuente del Vino, the wine fountain. So, now you’ll see the pilgrims extract from their bag a goblet or a gourd, to taste the precious nectar offered by the local winemakers. They offer wine, not glasses, so do not exaggerate. Here, the wine flows from the fountain since 1991, a tradition taken by the Benedictines who occupied the place. Some pilgrims just dip lips, others fill their gourd. Even Korean pilgrims stop there. At 8 o’clock in the morning, it is not really time for an extended tasting. |

|

|

| The Benedictine monastery of Irache is just above. It is a vast quadrilateral flanked by a Romanesque church with a square tower, a building dating back to the XIth century. The building mixes Romanesque and Gothic styles. The Cistercian monks then transformed it partly into a hospital for pilgrims. The cloister was built in the XVIth century. The facade and the convent were rebuilt in the XVth century. It is a Plataresque cloister. Plateresque means “like a goldsmith” (plata means silver in Spanish). It is a style quite exclusive to Spain, between late Gothic and early Renaissance, with countless decorations.

If the cellars are open at 7 a.m., the church does not open until 10 a.m., when all the pilgrims have passed. When we tell you that the Camino francés is made for pilgrims! |

|

|

| No more than the monastery and the cloister, the pilgrims will not visit the cellars. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a wide dirt avenue flattens along the enclosure of the monastery before reaching the hedges. |

|

|

| Further on, after crossing the national road, it is the sidewalk along a small road that runs towards a campsite. |

|

|

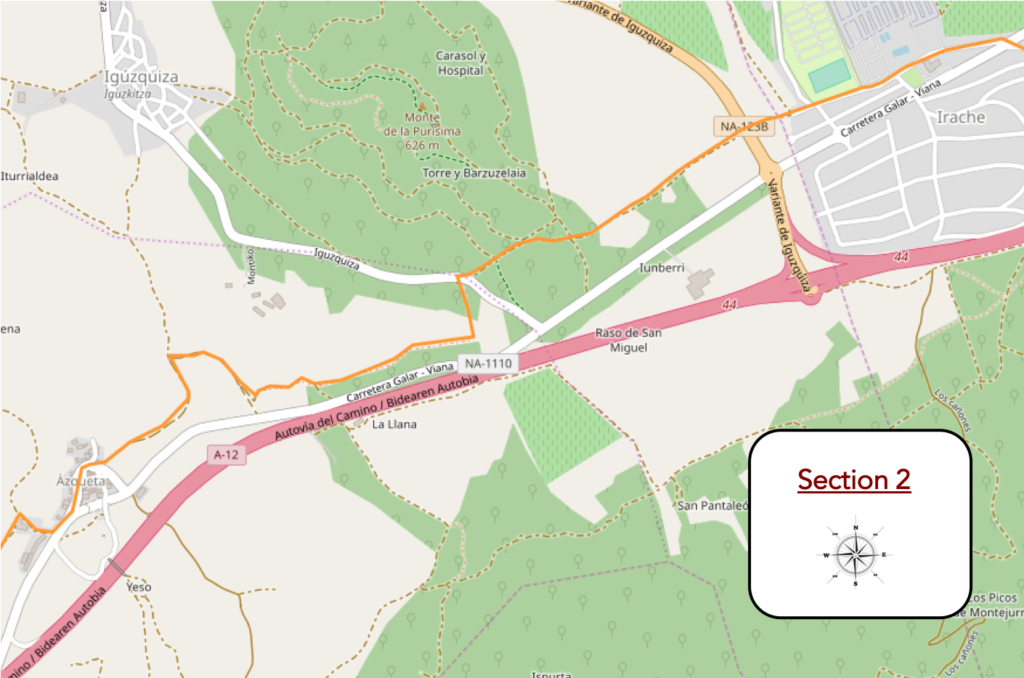

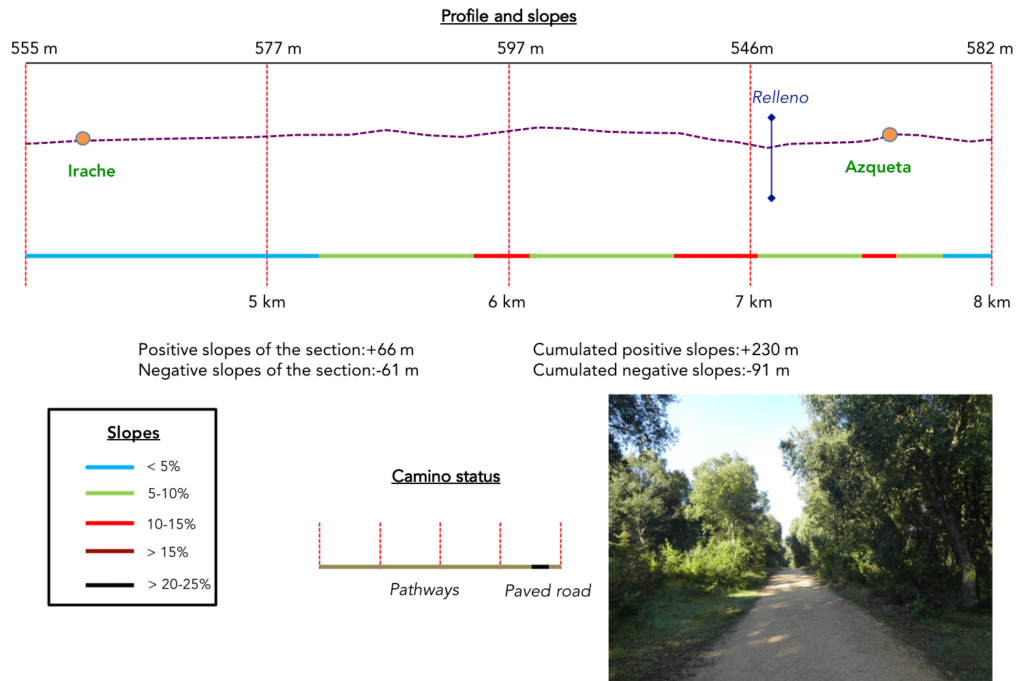

Section 2: In the sweet nature.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some oscillations sometimes a little more marked, without problem.

| The road then runs along the new housing developments of Irache, past the campsite. |

|

|

| The passage on the paved road ends when a dirt road takes over to pass under the NA-1238 road. |

|

|

| The dirt road then crosses the cereal fields. Nature is sweet here, serene. Then, the pathway heads to the forest. . |

|

|

| The pathway will undulate in the forest of Purisima, a beautiful forest dominated by small green oaks, the encinas of Spanish people. |

|

|

| Here is the world of serenity, beauty and inner peace. |

|

|

| And the game goes on until crossing a small forest road. |

|

|

| At the exit of the woods, the dirt road runs along the green oaks and the cereal fields. The region here is made up of gentle hills which are lost from one valley to another, and which change color according to the cultures or the big groves which enamel the country. |

|

|

| At the end of the clearing, the pathway changes register and slopes down into a dale. On the other side, you may catch a glimpse over Azqueta. |

|

|

| The pathway descends in the sandy soil along the green oaks and in the brooms. At the bottom of the dale appear the traditional black poplars.. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the dale, the pathway crosses the Relleno brook, hidden under the weeds, and gently climbs on the other side of the valley in the scrubland on the heavy ground. |

|

|

| The climb is a little tougher as the village of Azqueta approaches, but at no point in this stage is the walker facing excessive slopes. |

|

|

| In Azqueta, there are many pilgrims at the break. Americans, on average, are still arrogant, pretentious. The Koreans start to give less and less “Buen camino”. Well! It will soon be a week since they are on the way. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway will go for a walk in the vegetable gardens below the village. |

|

|

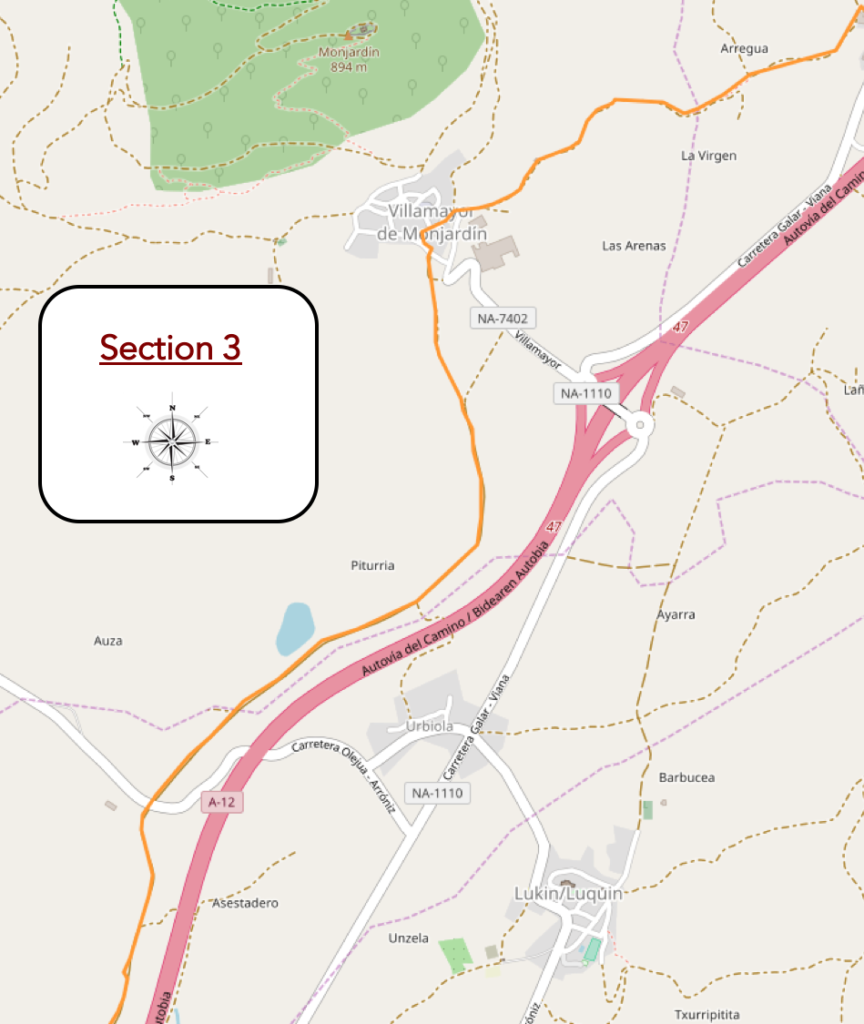

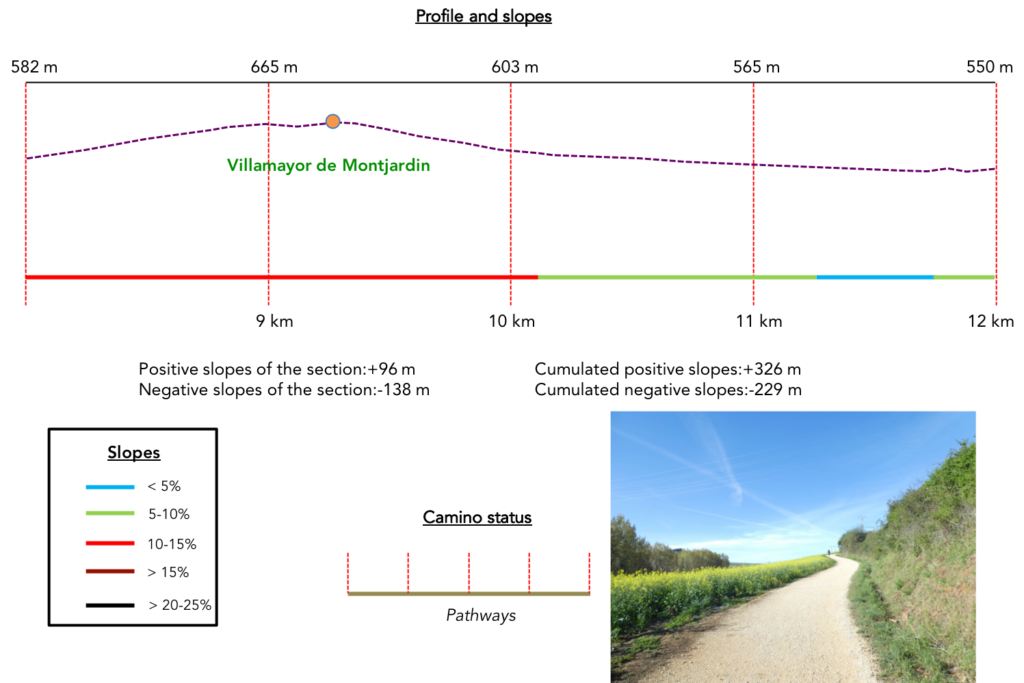

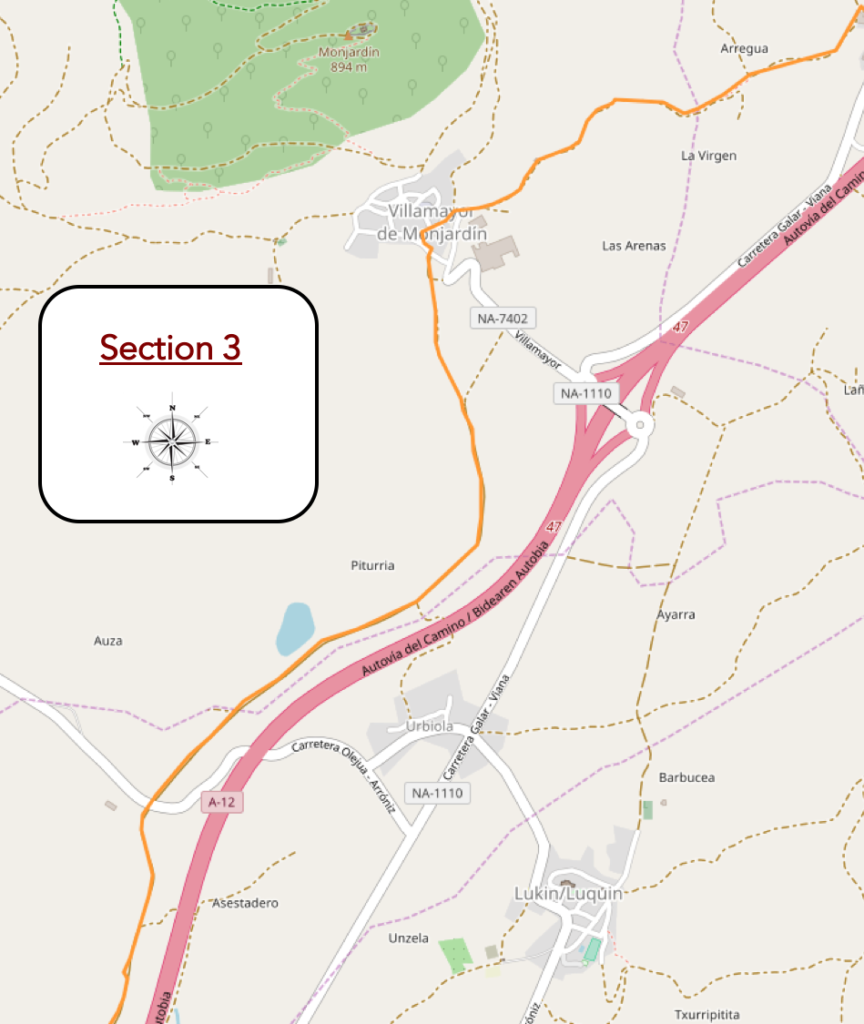

Section 3: An effort near the remarkable site of Villamayor de Montjardin.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: the only real effort of the day, between 10% and 15% of slope, uphill and downhill.

| Beyond Azqueta, a little effort is asked to the pilgrims, who have strolled so far, it must be said. The pathway will climb to Villamayor for a good kilometer, oscillating between 10% and 15% of slope. |

|

|

| It starts in the rape fields. |

|

|

| No shadow, so to speak, it must be an extreme joy to pass here under the heat. Further up, wheat takes over rape, along small walls. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope becomes less tough when Villamayor de Montjardin appears at the top of the hill. |

|

|

The pathway passes in front of La Fuente de los Moros, the Fountain of the Moors, a Gothic fountain from the XIIth century, built at the time for the ablutions of pilgrims. It is a Mozarabic building. The Mozarabs were Iberian Christians who lived under Moorish rule. They remained unconverted to Islam, but became Arabized by adopting elements of Arabic language and culture. It is a deep pool where you descend by steps. The water here is cool, even in summer. There is little doubt that in periods of heat wave, some pilgrims will not hesitate to dive there. But, this year in the spring, the temperature is below 10 degrees. No pilgrim will attempt the feat.

| Above the medieval swimming pool, the pathway gets to the village. |

|

|

| The castle can be guessed up there, above the colorful streets of the village. Monjardín Castle was built in the XIth century, after the expulsion of the Moors. All that remains of this medieval castle are a few ruins on the hill. These are the ruins of the Castillo de San Esteban. Tradition says that the current name of the mountain comes from the Navarrese monarch Sancho Garcés I, who conquered Castillo de San Esteban de Deyo, a fortress located at the top of the mountain, in the Xth century. |

|

|

| Here, the king is honored. The king was buried here. Sancho Garcés I was King of Pamplona, perhaps the first king of the Kingdom of Navarre, before him a small kingdom that he expanded considerably, reaching La Rioja through a series of military campaigns against the Muslims. He conquered Nájera and established his court there, providing a definitive organization of the Kingdom of Pamplona, which later became known as the Kingdom of Navarre. |

|

|

| San Andrés Church is a Romanesque church from the XIIth century, with a baroque tower from the XVIth century. Closed, of course. |

|

|

Below the village there is a good class hotel.

| Further afield, the pathway descends steeply for almost a kilometer, through fields and vineyards. The horizon is clear on the valley below where the highway passes. The vines are growing in number. You are getting closer to Rioja, and some Rioja are also produced in Navarre. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope softens on the red dirt. The vines disappear when the black poplars return. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway runs near a psychedelic shelter with a Roman statue as a fireplace. There is little doubt that this type of establishment is often used at night by penniless pilgrims. |

|

|

| The pathway then arrives in the plain and its crops, a stone’s throw from the motorway. |

|

|

| Further on, it crosses a small local road and sinks into the cereal fields. |

|

|

| Then begin long stretches that undulate in the cereals, not far from the highway. The traffic is not severe on this axis, at least in this spring season, which does not in any way disturb the pilgrim sunk in his thoughts, because here there is time for that. |

|

|

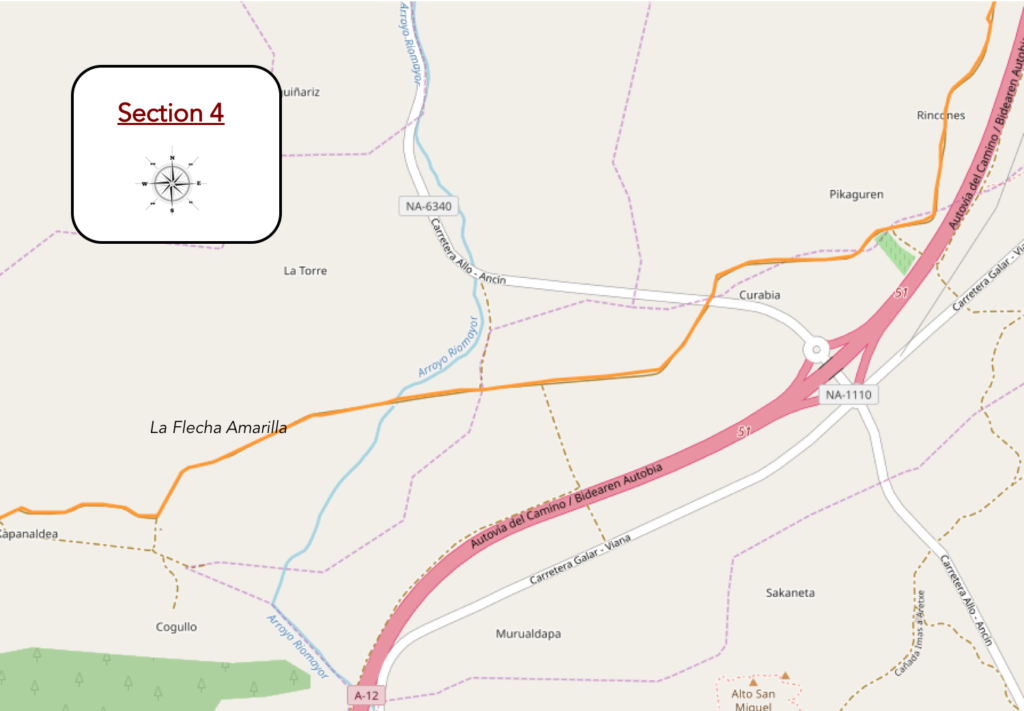

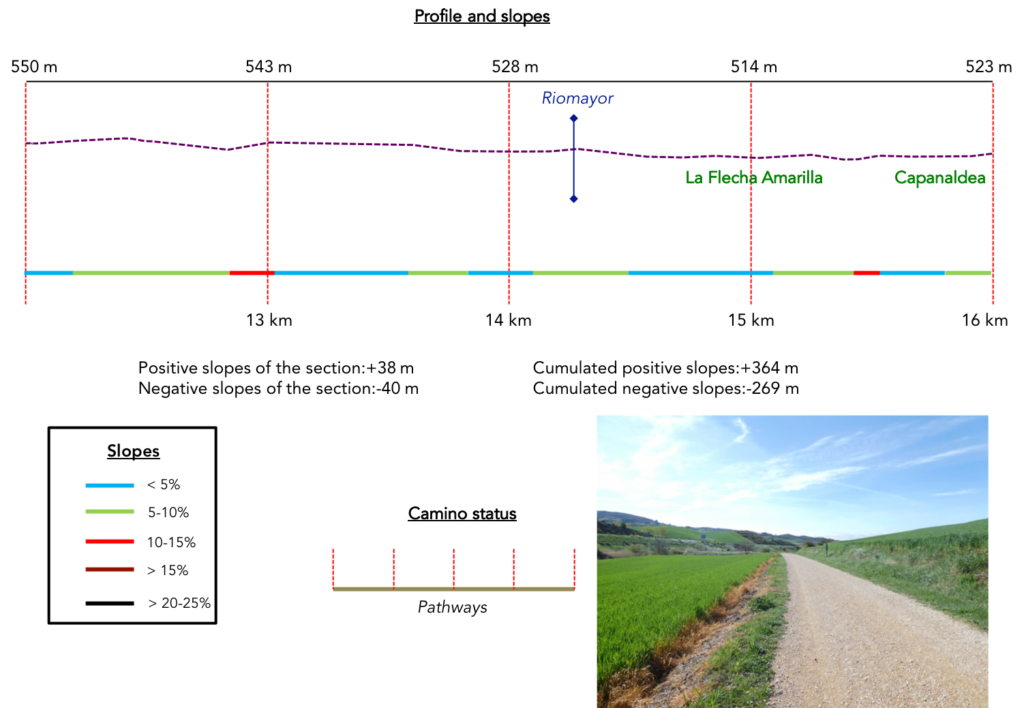

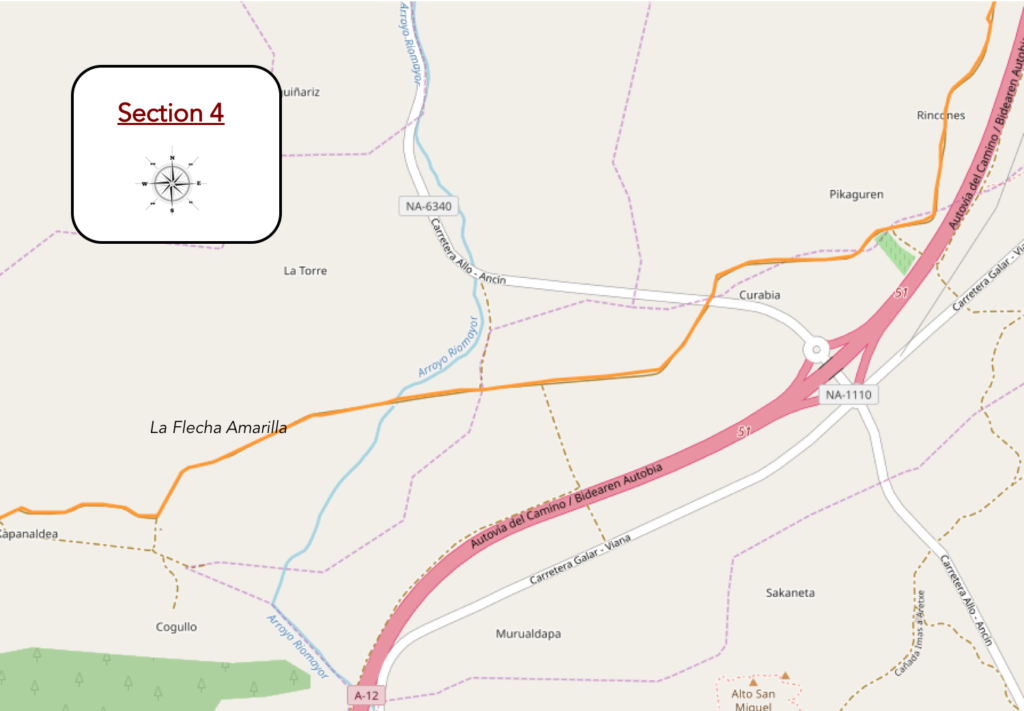

Section 4: A foretaste of what is called here “Meseta”.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathways in Spain are on average wide, much wider than on the other tracks of Compostela. Well! When the Spanish way is called The Way, there is reason for that. The pathway then crosses the fields on gentle hills, not far from the highway. |

|

|

| Further on, it abandons the main road. Silence again, a sort of dive into time and space. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the landscape changes a little with a few meager olive trees by the side of the road. But it’s very brief, and the pathway still leads through the wheat. Further, always further, like the waves in the sea. |

|

|

| Then, come back the lengths in the big fields of cereals, with some rare other cultures, as here asparagus. You guess, because you read in the guides, that this type of landscape will become the daily lot for the next 10 days. |

|

|

| Sometimes, some vines, because we are getting closer to Rioja, which we will reach tomorrow. On the way, there are lonely, married couples or friends and groups. Some pilgrims prefer loneliness. So, they can let themselves be rocked in their inner world. Others hate loneliness. So, they organize themselves at the start or during the trip. With two or more, the walk seems less long. They spend hours and days telling each other their lives or the stages of the journey. |

|

|

| And it is in these places, as here in the open-air bar of the Flecha Amarilla that crystallizes the spirit of the track. Almost all pilgrims stop in these places, where the Santiago track is told. It is a real tower of Babel, in an insufficient Spanish or in an often-elementary English language. The Americans are still talking so much, the Koreans stay between them, like the Spaniards. Other nations are doing as well as they can. |

|

|

| Breaks are never eternal. You have to respect the schedule. But why, in fact? In this first part of the track, the stages are of the order of 20 kilometers, a little more sometimes. As the pilgrims, for the most part, are advancing at about the same speed, between 4 and 5 kilometers per hour, they will have arrived at the end of the stage at about midday, the slowest ones a little later. The afternoon and the evening will be long, throbbing even, in the “albergue” and dormitories! But the pilgrims do not care, tomorrow will be another day. Then, the line of pilgrims is again running away over the gentle hills. |

|

|

| The pathway gets soon to a place known as Capanaldea. For the local peasants, these places probably represent a lot. They know the territory inch by inch. For pilgrims, this is only a place in the middle of nowhere. Not a house on the horizon. But, these signs on the way make it possible to measure what remains to be done. Here we are 5.7 kilometers to the end of the stage, in Los Arcos. |

|

|

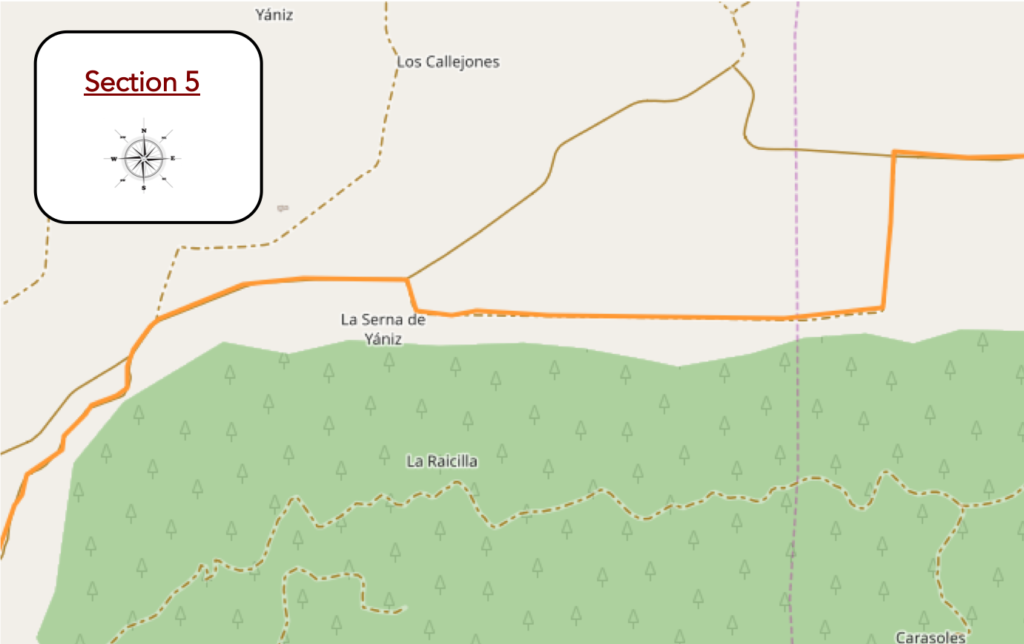

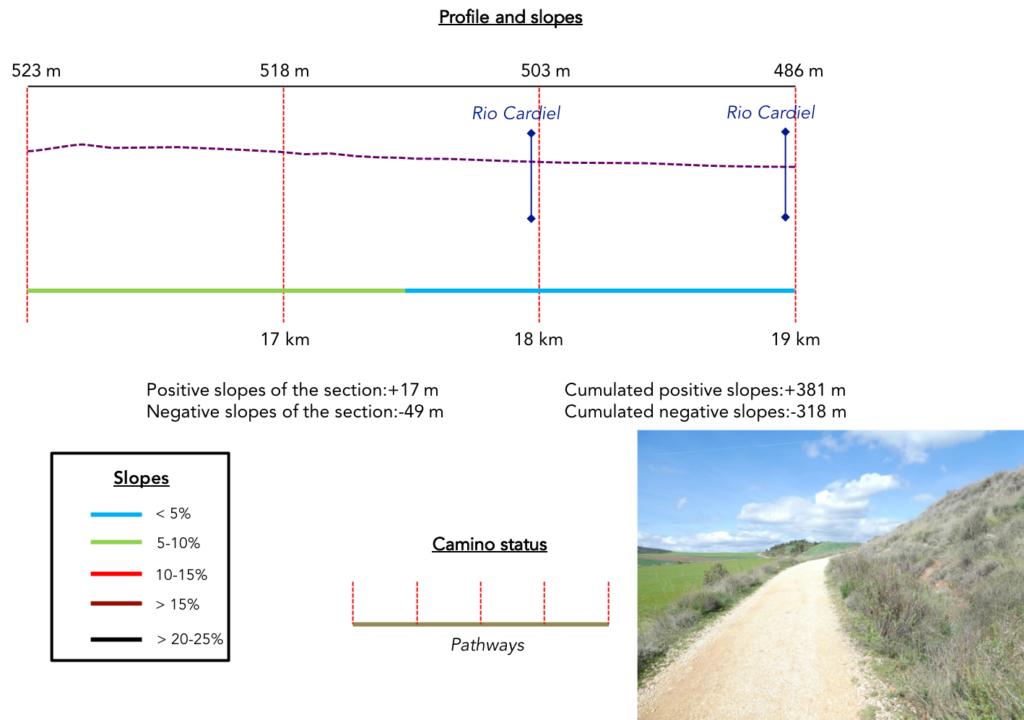

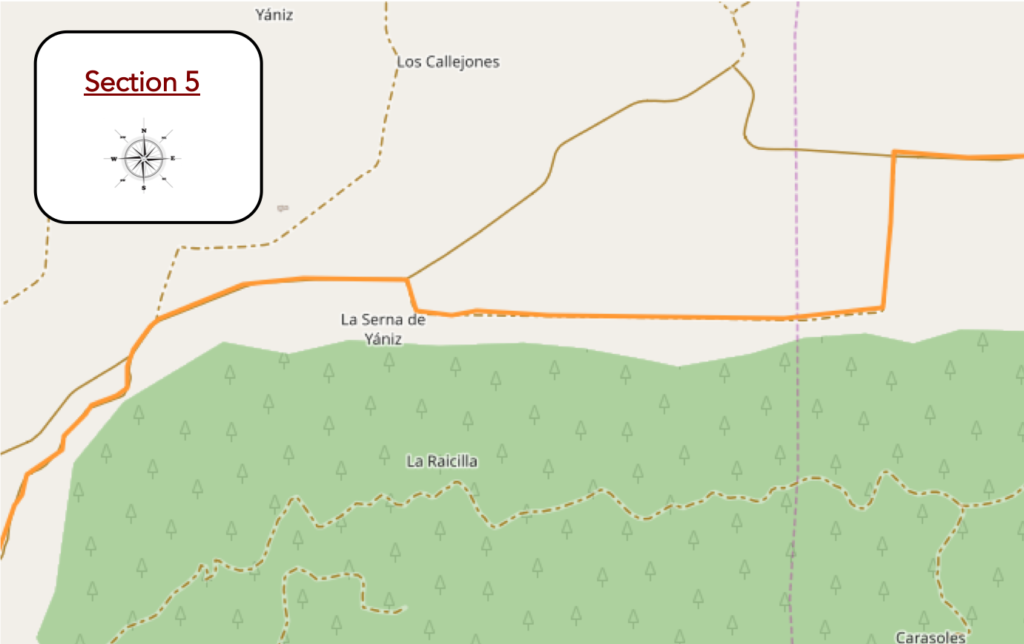

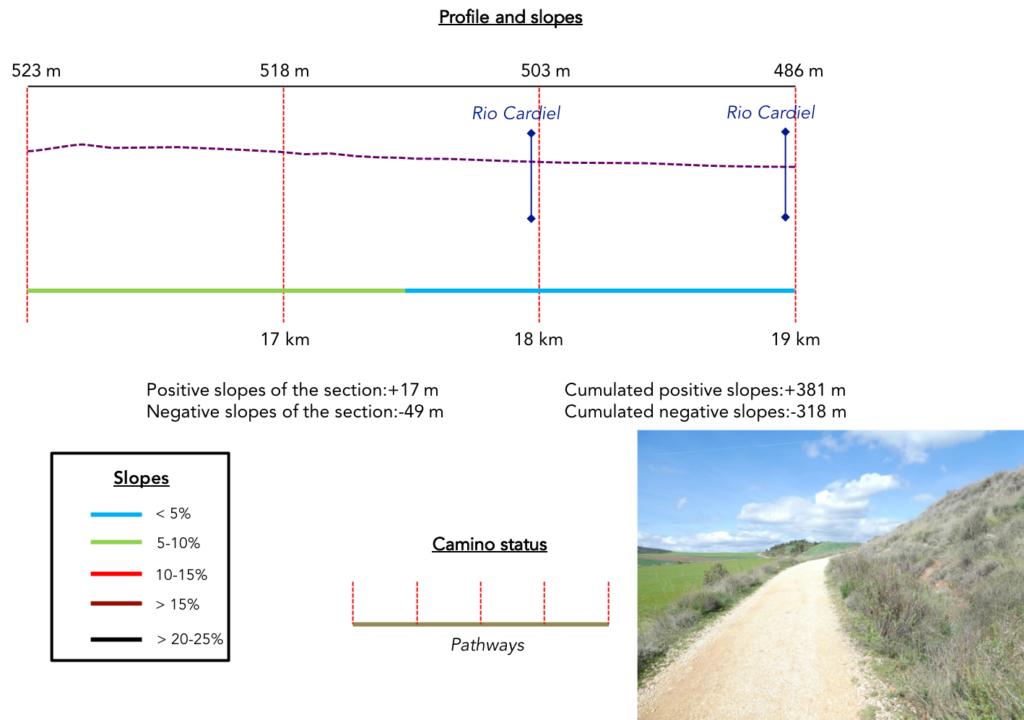

Section 5: In the cereal fields along the wooded hill.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The nose plunged on the dirt, some pilgrims feel a little lost in these infinitely large spaces escaping them, in this setting where often calm and silence are at the rendezvous. But sometimes, reality catches up with them. Footsteps screech on gravel. So, the reality of the track comes back. The TGVs almost always pass without saying hello. They do not have time. |

|

|

In this infinity where the end meets the sky beyond the hills, the sea of wheat vibrates under the wind, like a capricious swell. It feels like a scent of ground that emerges from the wheat that barely grow, because of a rainy spring.

| Dunes and groves serve as landmarks in this immensity which floats, which defies and stimulates thought. The pathway now runs along a wooded hill. |

|

|

| There is never a house or farm that could serve as a landmark. The only landmarks you have are pilgrims in front of you, fluctuating landmarks as possible, or a river, as here the little Cardiel brook. |

|

|

| PFurther on, a few lost vines, a little yellow, rapeseed, which brings a little color and contrasts with all this green of the wheat and the brownishness of the bare hill in front of you. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a sign announces that the end of the stage is not far, less than 3 kilometers. |

|

|

| The pathway then momentarily leaves the cereals for the pines. Here, you’ll find one of the arms of Rio Cardiel. You can bet that here, in hot weather, pilgrims will take a little cool under the trees. |

|

|

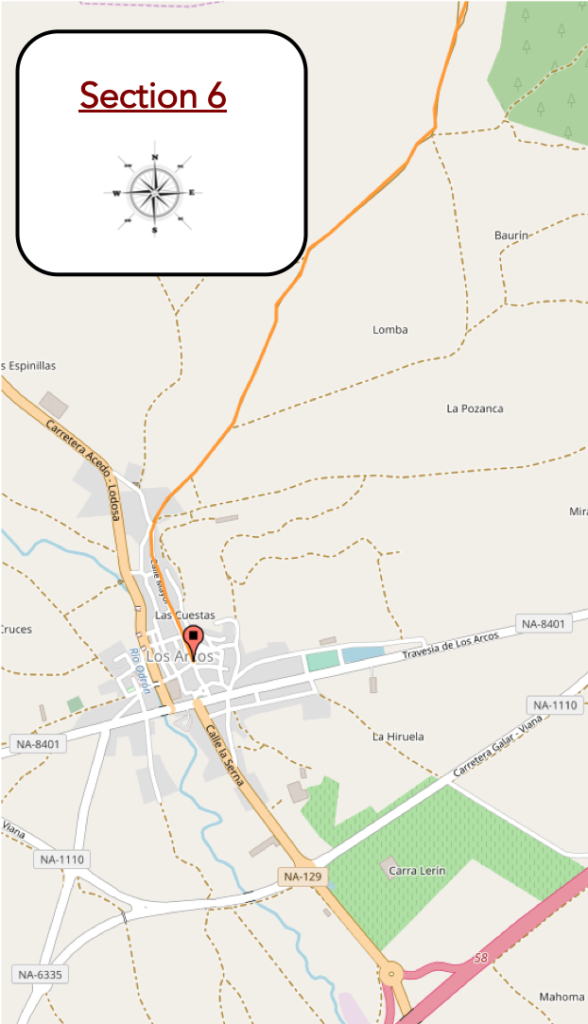

Section 6: Light ripples in the countryside towards Los Arcos.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway skirts the pine forest, crosses Cardiel Creek one last time. Here, we catch up, as we catch up every day, an American lady slowly advancing on the road. Languages quickly loosen on the way. After a week, the pilgrims know each other almost on the way, at least from sight, because the stages are almost obligatory because of the accommodations. So, everyone knows that this lady leaves before the others and arrives after the others. The Camino francés may be universal, it’s a small world, like many others. |

|

|

| Then, it is the return to current affairs, a wide pathway that ripples in the wheat, with brooms and rapeseed that push back on the banks of the peeled hill. The Camino francés is an eternal resumption. |

|

|

| Further on, a small bend and a long straight stretch which you wonder if it has an end… |

|

|

| …and which will end all the same at the top of the gentle hill in the olive trees.. |

|

|

| Beyond the hill, the pathway slopes down again in the middle of some almond trees towards Los Arcos, which can be seen in the plain. |

|

|

| As you approach the borough let’s say a large village, tar replaces dirt. |

|

|

| Los Arcos, originally a Roman city, was a favorite place of the kings of Navarre. King Sancho Garcés I reconquered it from the Muslims in the Xth century. In the XIth century, the King of Navarre gave the city a coat of arms with bows (arcos) and arrows, and since then it has been called Los Arcos. The center of the medieval village was once surrounded by walls. Three of the original seven gates remain to recall the city’s role as a fortress: Portal del Estanco, Portal de Castilla and Portal de San José. Like all cities in northern Spain, or at least a large part, Los Arcos is built in length along the central street. The houses seem quite old, turning to ochre, some even with balconies and moldings, others emblazoned. |

|

|

As in many large villages in the region, there was once a castle here, in a city that flourished in the XIth-XIIth century, after the Navarrese drove out the Muslims. As for all the cities of the region, the Castilians also eyed the side of this city of Navarre. It will pass into the hands of the Castilians at the beginning of the XVIth century, and Philip II, the King of Spain and Castile also granted them the traditional privileges, the fueros, which he later abolished. It was during this Castilian period that the city reached its peak, and everything was transformed into Baroque in the city. At the end of the XVIIIth century, the city passed into the hands of Navarre and lost its Castilian privileges, in particular its permanent market or its possibility of exporting wheat to Castile.

The soul today of the village (1,100 inhabitants) is the Plaza de Santa Maria near the church of the same name. Its southern flank is occupied by the portico of the church, while the other sides have buildings from the XVIIth century, also with porticoes, lintels, arches and pillars. Here, pilgrims, as soon as they arrive, gather at the square bar to chat about their moods and their exploits on the route.

| The church is central in the arcaded square, at the end of which stands the Porta de Castilla, in the shape of a triumphal arch, overlooking the Odrón River. It is a XIIth century reconstruction, restored again in the XVth century. |

|

|

| The Church of Santa María de los Arcos is one of the most important churches in Navarre. The original Romanesque church built in the XIIth century was one of the largest on the Camino de Santiago. It was embellished from the XVIth to the XVIIIth century with Gothic, Baroque and Classical elements. The bell tower, which has Gothic and Renaissance elements, is also from the XVIth century. However, the interior of the church is its current claim to fame, especially with its baroque altarpiece and its Virgin, Nuestra Señora Santa María de Los Arcos. When we first passed here, the building was closed during our visit. It really begins to be a hateful attitude to close the churches. In the past, about ten years ago, the churches were almost all open to the Camino francés. Why are churches closed? For fear of vandalism and theft. However, most of these thefts are carried out in closed churches. A closed church secures thieves more than the building. People close the churches, because they do not have the financial means, it is said, to install an effective and appropriate protection system there. Churches are also closed because the police demand it and so that penniless pilgrims do not use them for their convenience, or even their natural needs. To close a church is to privilege the accessory, to the detriment of the essential. It is to make the church a museum, a dead place. |

|

|

|

|

| But there! Some pilgrims often repeat the same journey, or at least part of it. So, by chance, or rather the period, you sometimes find these churches open. The first time was Easter week in a rotten spring. So, people skipped the Holy Week processions. This second time was also Holy Week, but in good weather. So, the preparations were at their fullest and the church was open. It is said to be one of the most beautiful churches in Spain. Certainly, if you swoon over the golds, bronzes, and frills of all styles. It’s dripping everywhere. The Spaniards love the genre. But, will say all the same that it is a little loaded. |

|

|

| The interior of the church is its current claim to fame, with above all its baroque altarpiece and its Virgin, Nuestra Señora Santa María de Los Arcos. |

|

|

Actually, a replica of the Virgin is also drawn on a chariot during Holy Week processions.

| Here, the chariots for the Holy Thursday procession were being prepared. You should know that in Spain a cofradía (brotherhood) is the section of a congregation that is responsible for organizing the Holy Week procession. Depending on the cities or the number of churches, there are several, of course. In this type of organization, there is a Spanish word for all actions such as: the crowd present in some of the streets where a procession passes, the cone-shaped hood, made of cardboard or plastic, or the veil that also masks the face, the foreman who is in charge of guiding the porters throughout the procession, the time and the distance traveled between the moment when the porters lift the chariot and the moment when they put it down again, the porters who support the weight tanks, with their espadrilles, their wide belt and their big bag which they place on their head, under a folded canvas, to avoid hurting themselves. |

|

|

| Unlike the church, the cloister is absolutely sober. |

|

|

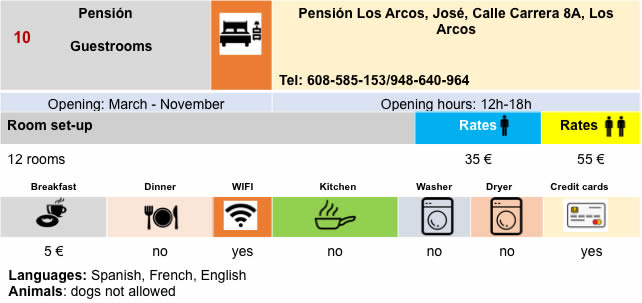

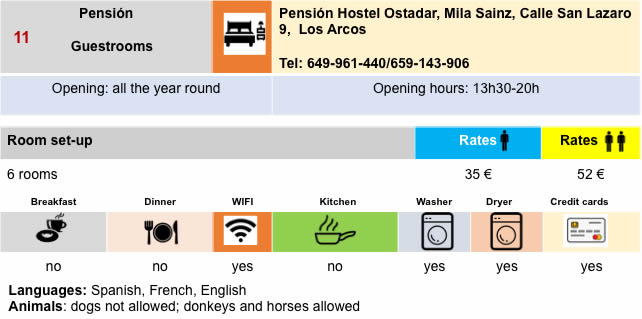

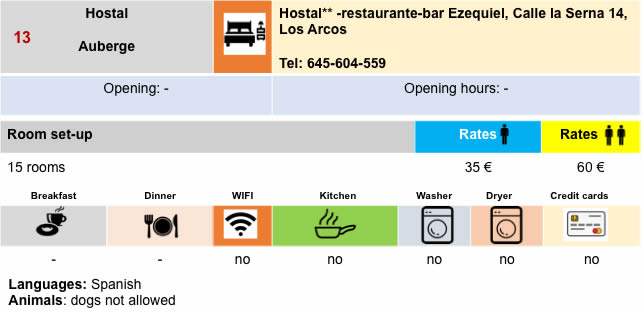

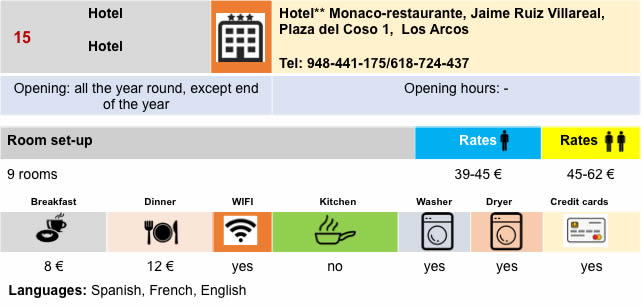

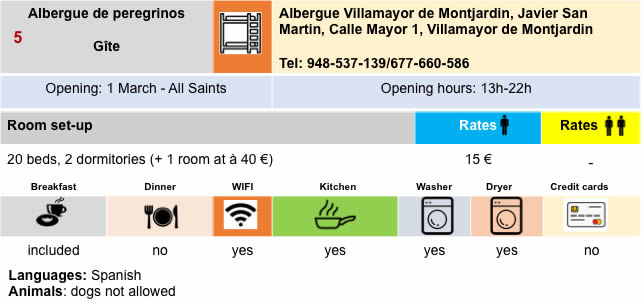

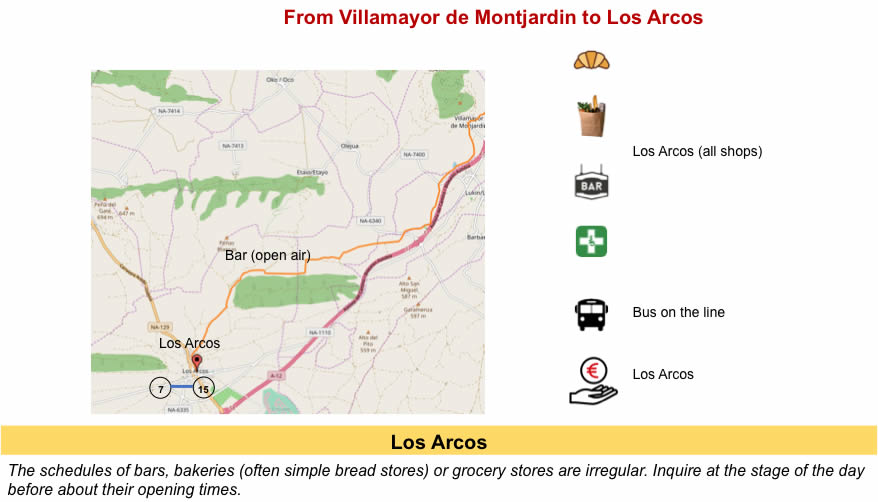

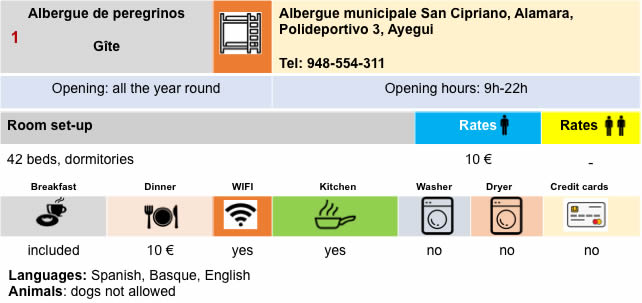

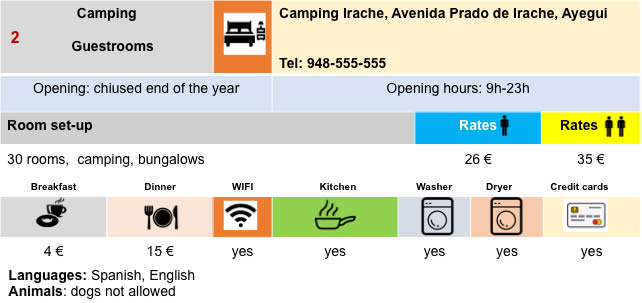

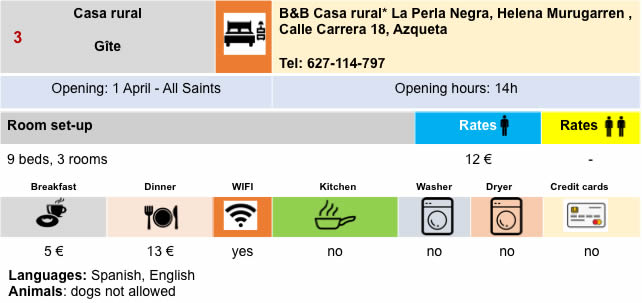

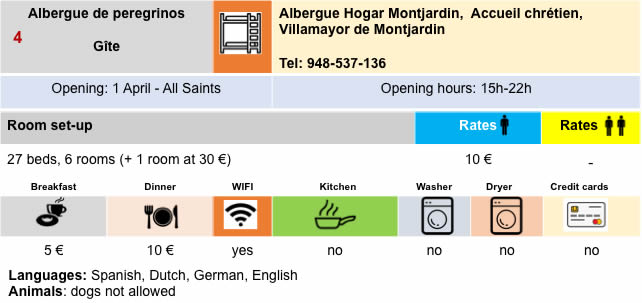

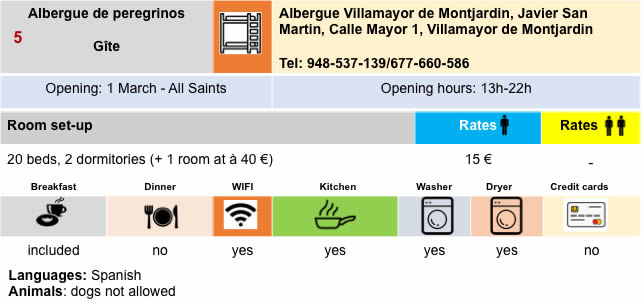

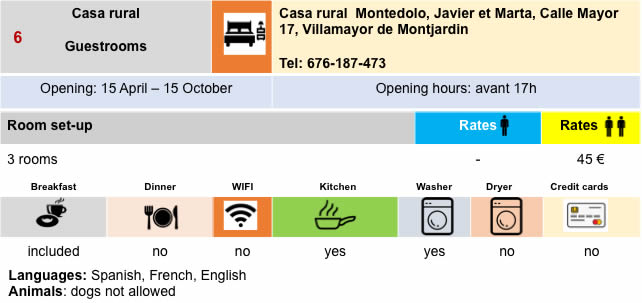

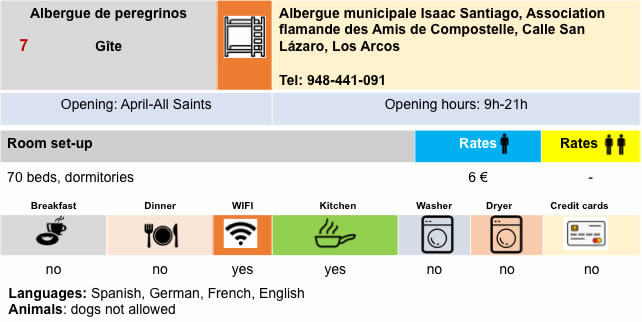

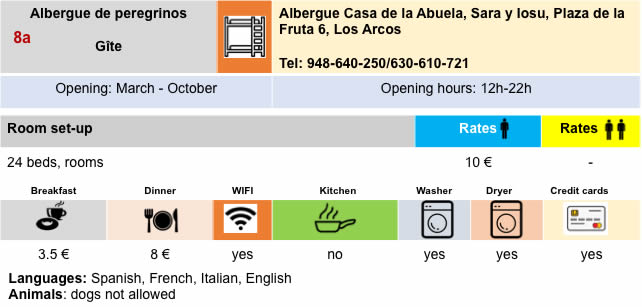

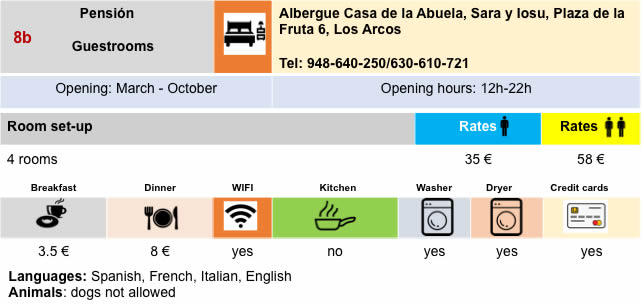

Lodging

|

/td> /td> |

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 7: From Los Arcos to Logroño |

|

|

Back to menu |

/td>

/td>