In the vineyards of Rioja

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

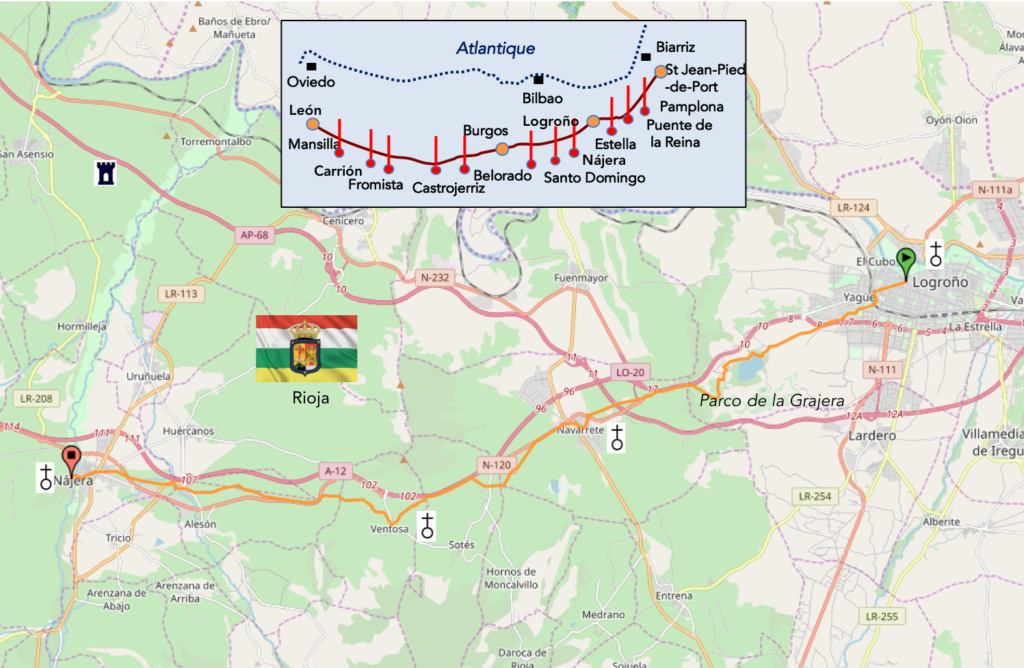

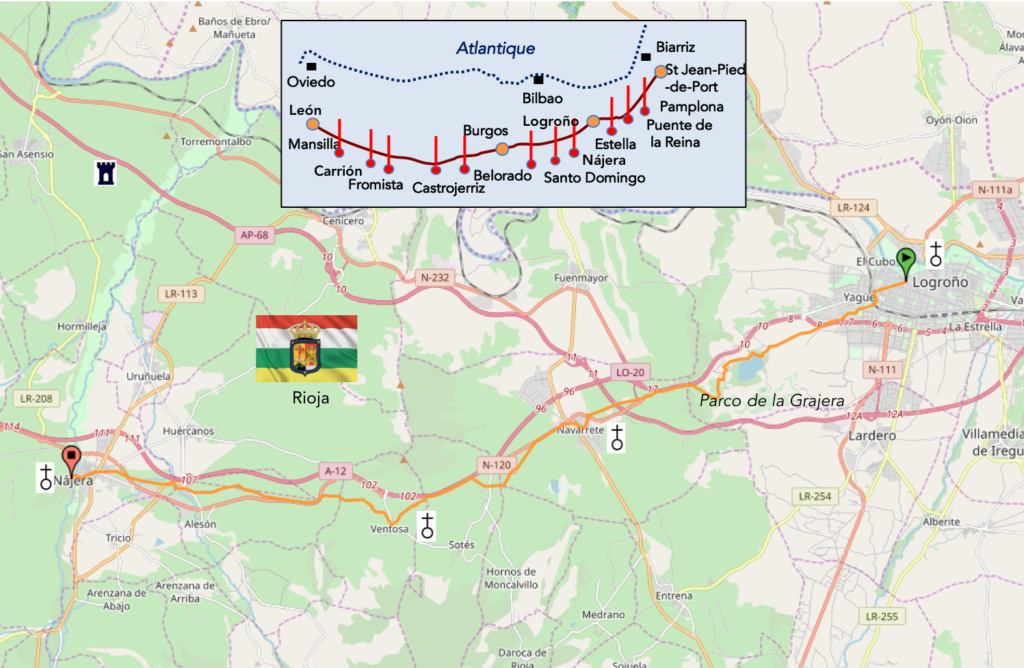

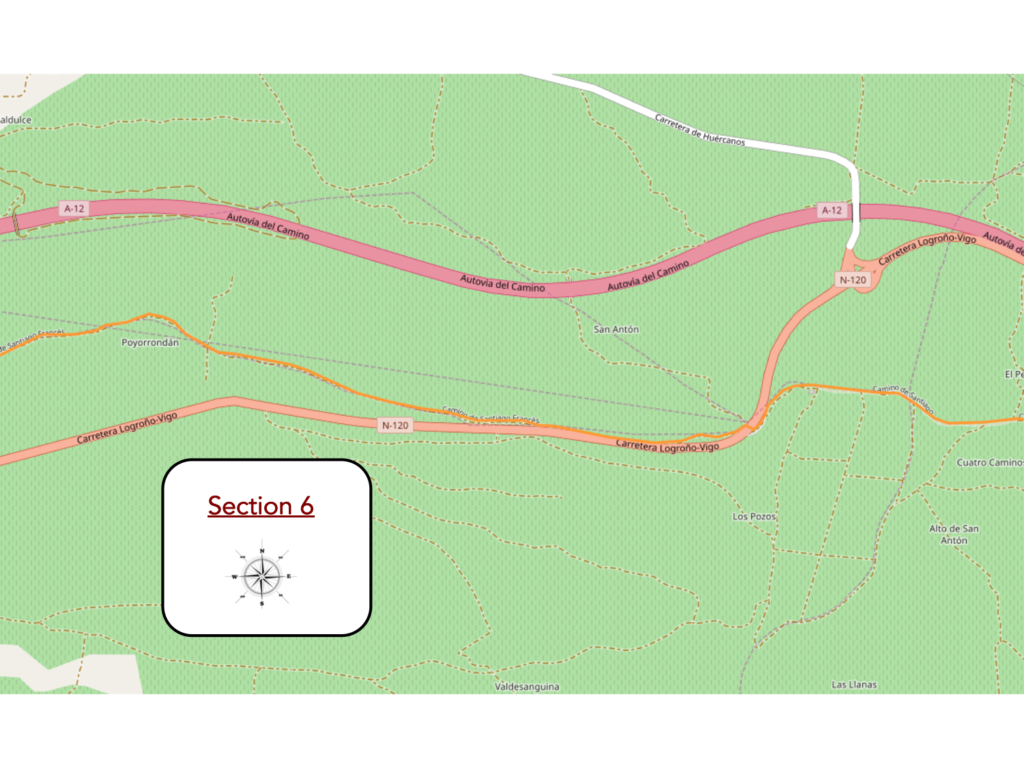

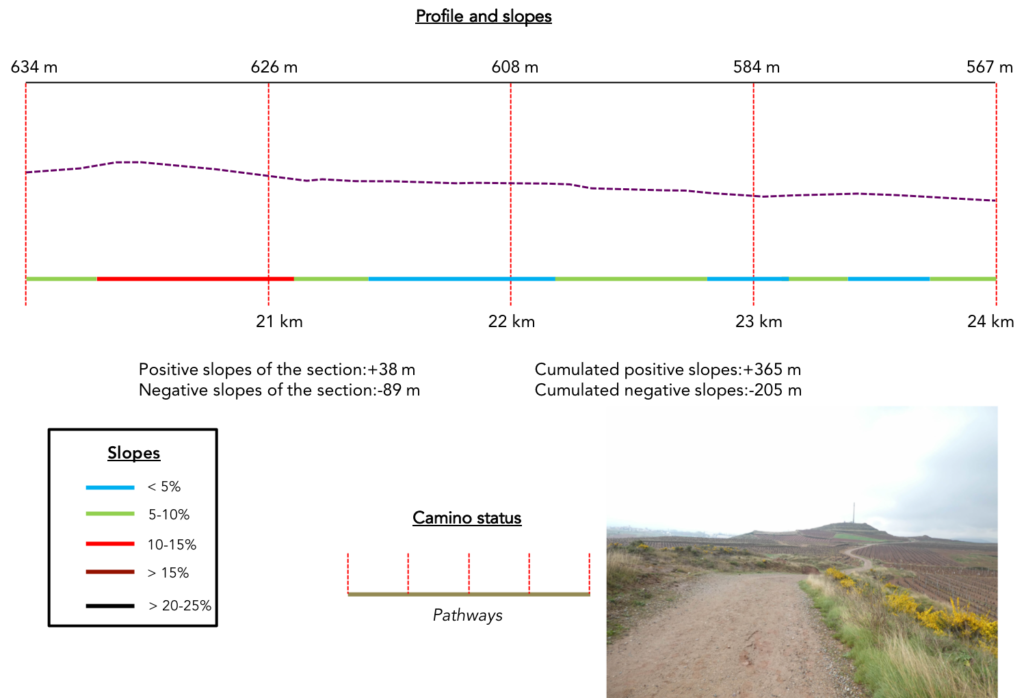

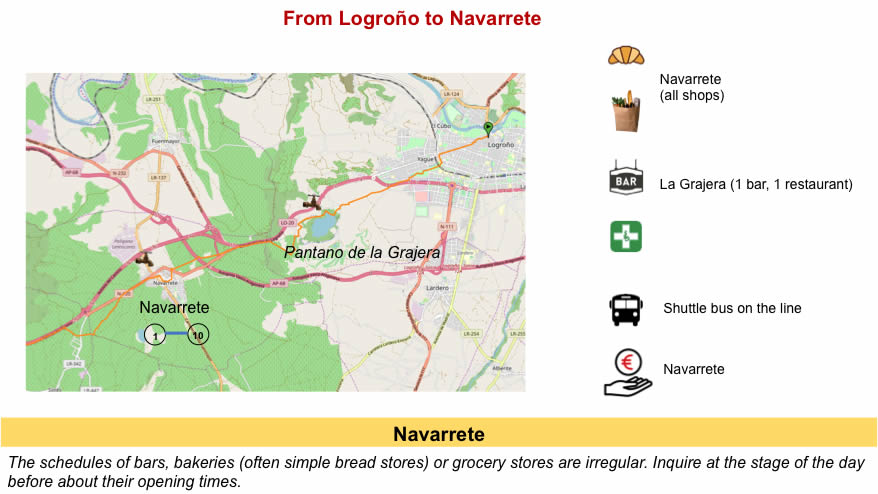

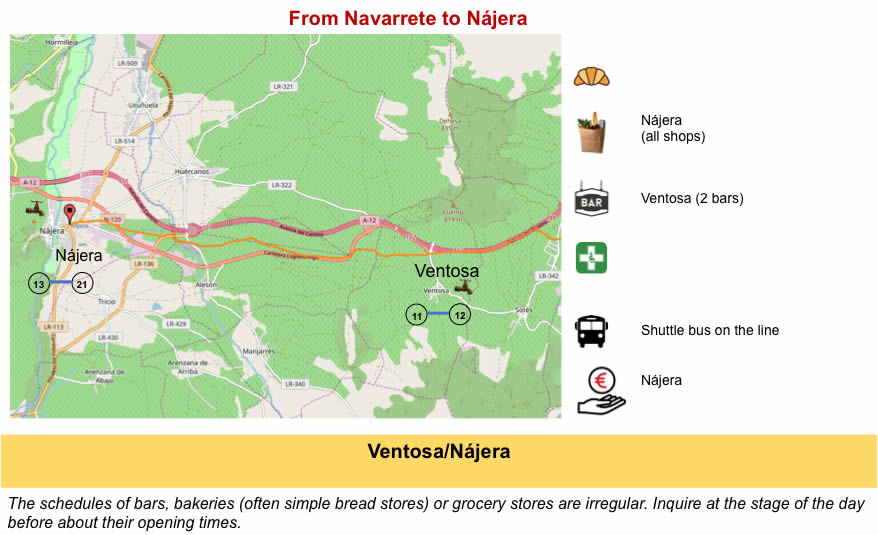

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-logrono-a-najera-par-le-camino-frances-37876911

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

In area, the vineyard of Spain is the largest in the world. The country produces many table wines, but several regions emerge, in red wines, among the best wines of the world. These are Rioja, Ribera del Duero, a little further south in Castilla, and the Priorat in Catalonia. In the north, Galician wines are primarily white wines.

Source : technorest.org

The wines of Rioja are multiple, because they come from distinct regions with varied climates, altitudes and soils. In the lower regions, they are often fruity, to drink young. When the vines grow on upper hills and the soils are poorer, the wines are more complex, wines of guard.

Rioja is usually divided into three regions:

• La Rioja Alta: region between 400 and 500 meters, less hot, with an Atlantic climate influence, involving freshness and humidity, which is better for wines. The king variety is tempranillo (Temprano means “early” in Castilian).

• Roja Alavesa: a climate similar to Rioja Alta, but the soil is rockier, giving wines as fine, but rounder and denser than in Rioja Alta. The king grape variety is still tempranillo.

• La Rioja Baja: a warmer vineyard, down to 300 meters above sea level in the east of the region, with a rather Mediterranean climate, with significant sunshine or even drought. The wines are more structured. The king variety is Grenache.

Source : Cellartours.org

Come on, this is not an insult to the Rioja Baja, but the great wines are mainly in the other two regions, especially in the vineyards near the Ebro River. If the well-known wineries Marqués de Riscal and Marqués de Murrieta are located not far from Logroño, other well-known wineries, such as Marques de Cáseres, Muga, Lan, Roda are in Rioja Alta, and Artadi in Rioja Alavesa. But, it is not so obvious as that. Consider, for example, one of the best-rated wines, a wine from the winery called “Rioja Alta”, simply. This estate has belonged to five families since 1890. These people have 470 hectares in Rioja Alta, 65 hectares in Rioja Alavesa, 63 hectares in Rioja Baja, and even vineyards in Galicia and Ribeira del Duero. They will not tell you easily where the plot is located that gives the best wine. Wine is classified as in many other regions of Spain in “Rioja” when the wine spends at most a few months in oak barrels, in “Rioja Crianza”, when it is aged at least two years, of which at least one in oak casks, in “Rioja Reserva” with three years of aging, including one in oak casks, finally in “Rioja Gran Reserva” with at least two years in oak casks and at least three years in bottles.

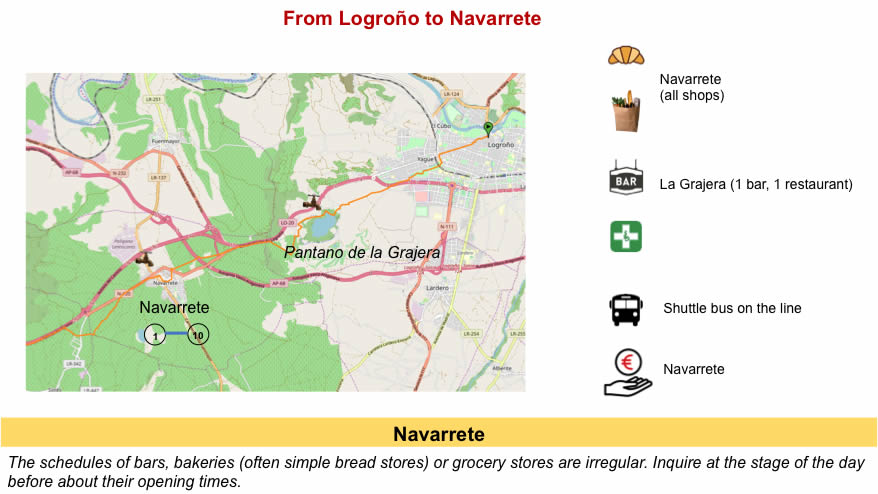

Today, the vineyards of Roja Alta, where the track runs, are in the southern part of the vineyard. Unfortunately, you’ll cross these vineyards in the rain. Today, cereal fields are much more discreet, and from vineyard to vineyard, the course gets to Nájera, an ancient capital of Navarre, became Castilian for centuries, before being in Rioja recently.

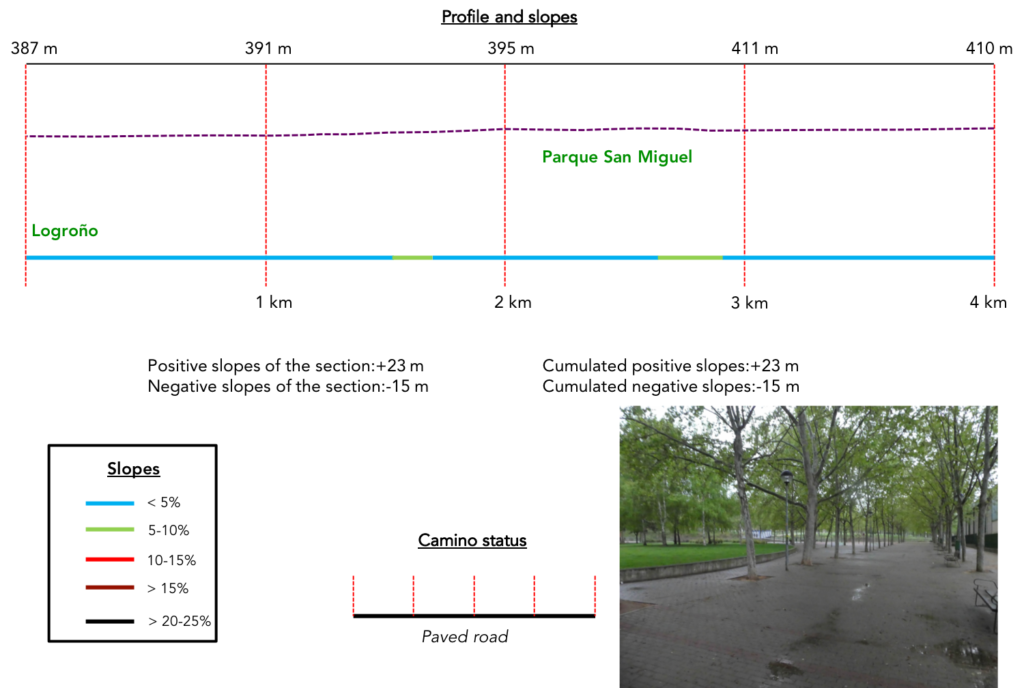

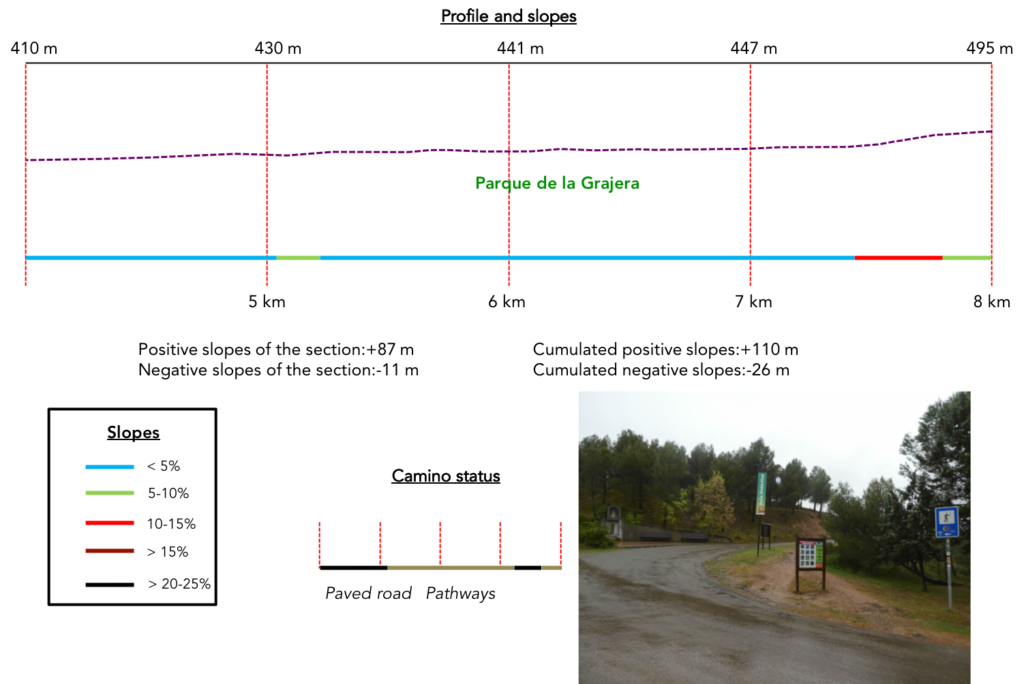

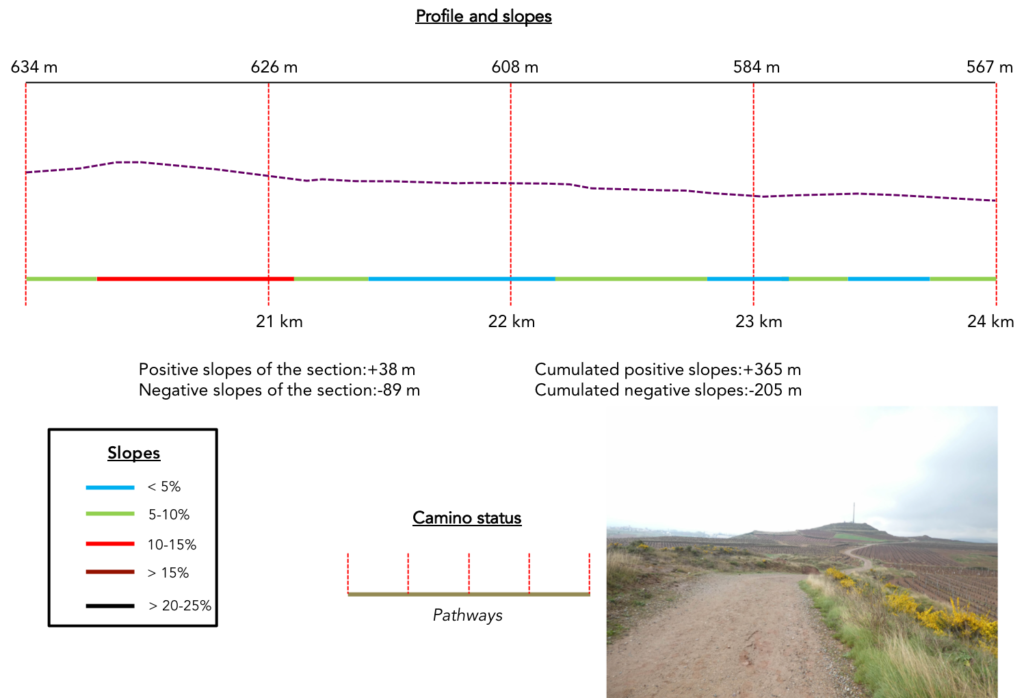

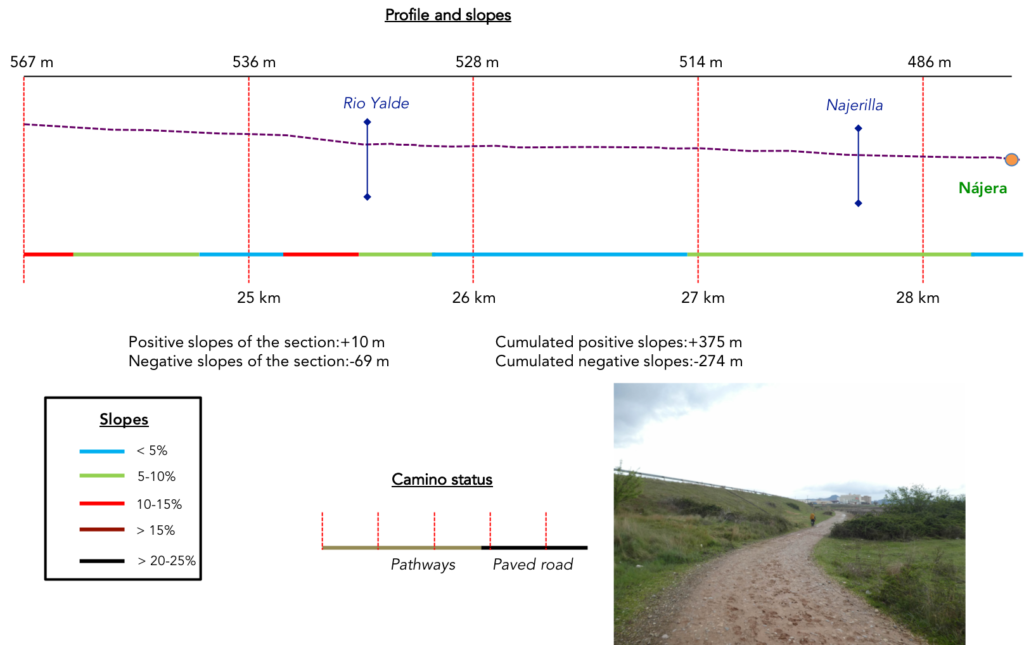

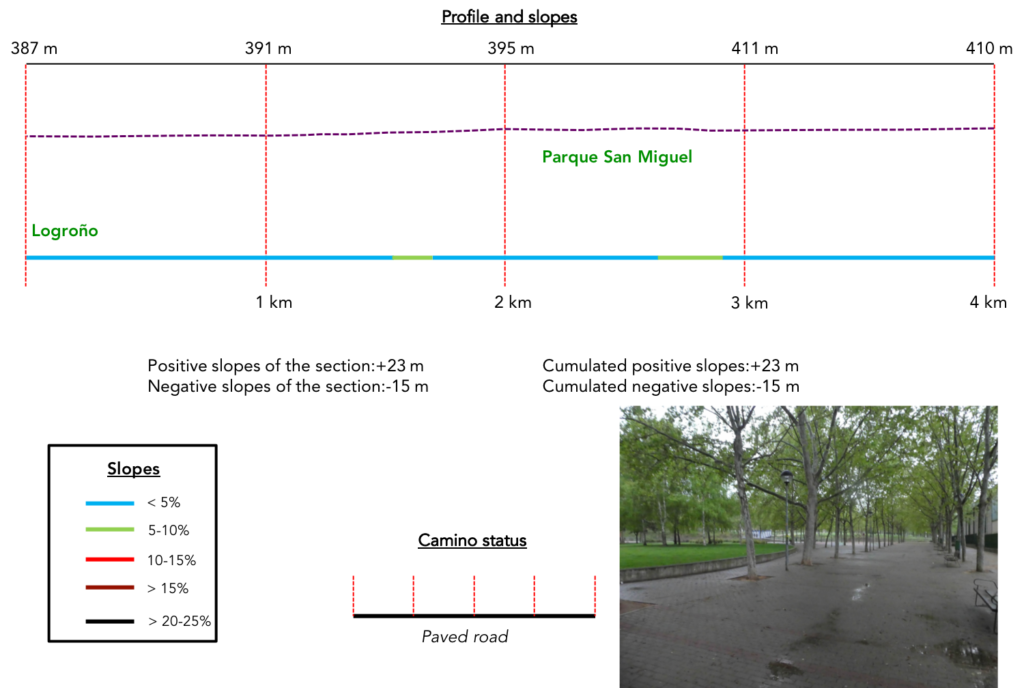

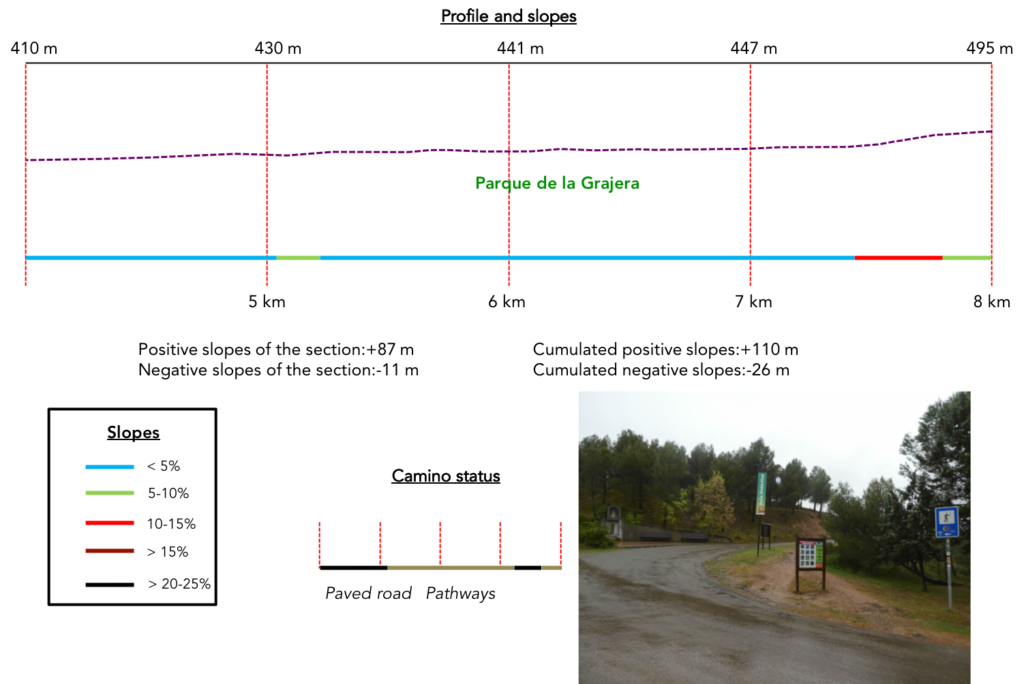

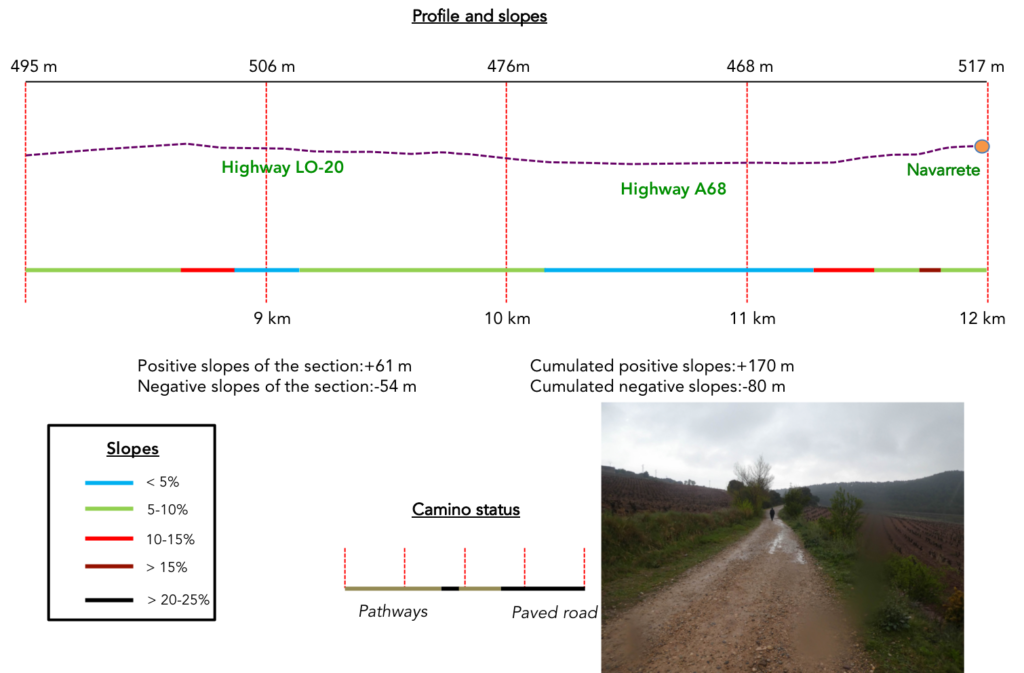

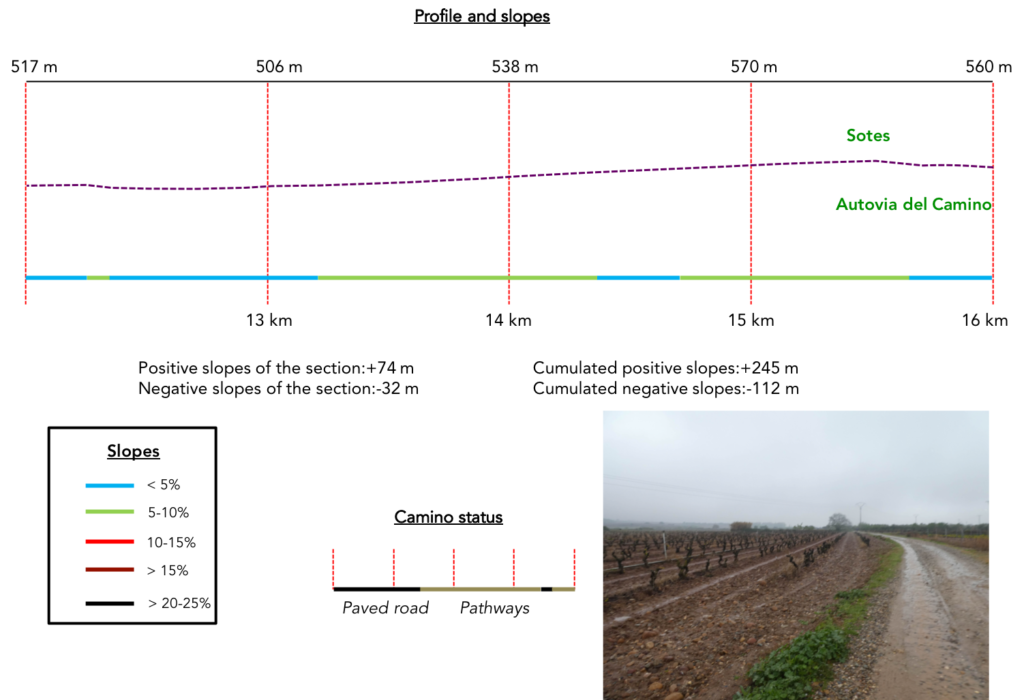

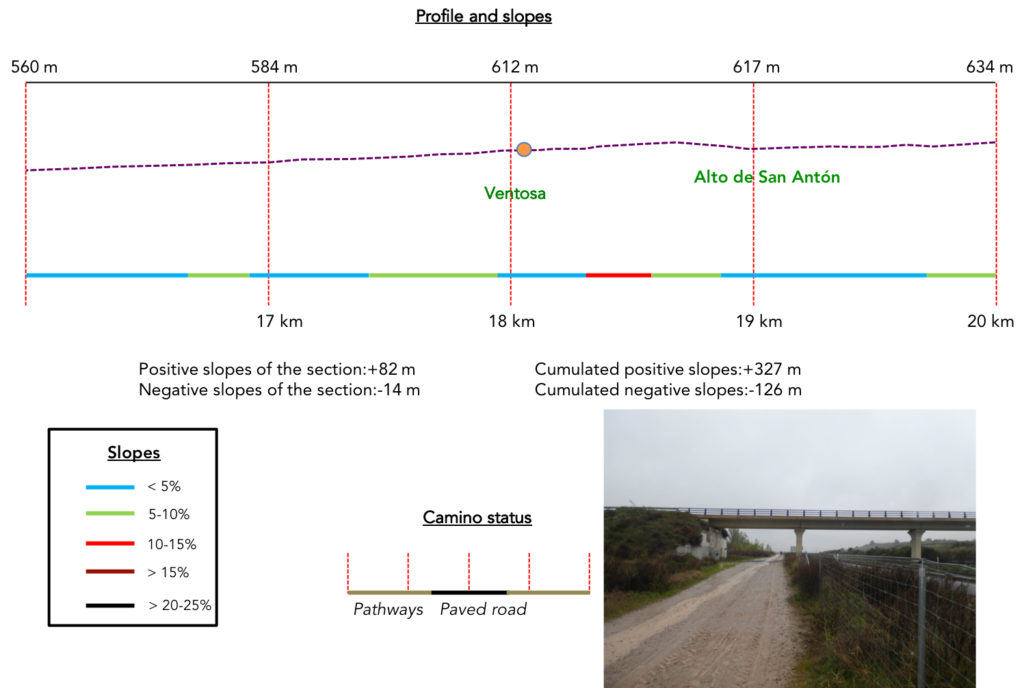

Difficulty of the course : Slope variations today (+375 meters/-274 meters) are low for a stage of more than 28 kilometers. The Camino francés remains a low altitude course, even if today you do not really walk on the high plateau, but rather on hills. It is flat to the Grajera Park, where the pathway climbs steeply up the vineyards to the highway. Afterwards, the route is quiet for a long time, usually with a very slight climb, before climbing a little further under the Alto de San Antón, beyond Ventosa. In fact, the major difficulty, for us today, is the bad weather that makes the roads very muddy. May you enjoy the vineyards on a sunny day.

In this stage, there is a lot of paved roads, which is not common on the Camino francés, even if most of the trip is still on the roads. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads :

- Paved roads: 11.9 km

- Dirt roads: 16.6 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: The way out of the city.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Today it is raining on Rioja and the weather forecast for Holy Week is not good for all of Spain. Wind, rain, cold, these are the celebrations announced, with perhaps some clearing. The Camino leaves the Plaza Alférez Provisional, where you arrived the day before, and heads to the new town on the long Calle Marqués de Murieta, then on Calle Duques de Nájera. What you see is that this part of the city is opulent, with well-appointed modern buildings. |

|

|

| At the end of the street, it reaches the park of Europe under the poplars and there it crosses the railroad track. |

|

|

| The Parque de l’Europe is followed by the Parque San Miguel, on cobblestones that hardly slip even under the downpours that fall on the pilgrims, the only brave people present at these early morning hours. |

|

|

| There are pleasant bodies of water. You guess that the world must crowd into this pleasant park in good weather. But today won’t be a day to walk the strollers. |

|

|

| The park stretches long into the outer suburbs, when the Camino then leaves town passing under LO-20, the bypass highway. When it’s raining hard, it’s not the time to take out your camera every minute. It took you nearly 4 kilometers to leave the city for good. It will be said that the outskirts of Logroño are perhaps the nicest and best maintained among the towns we visited on the Spanish way. |

|

|

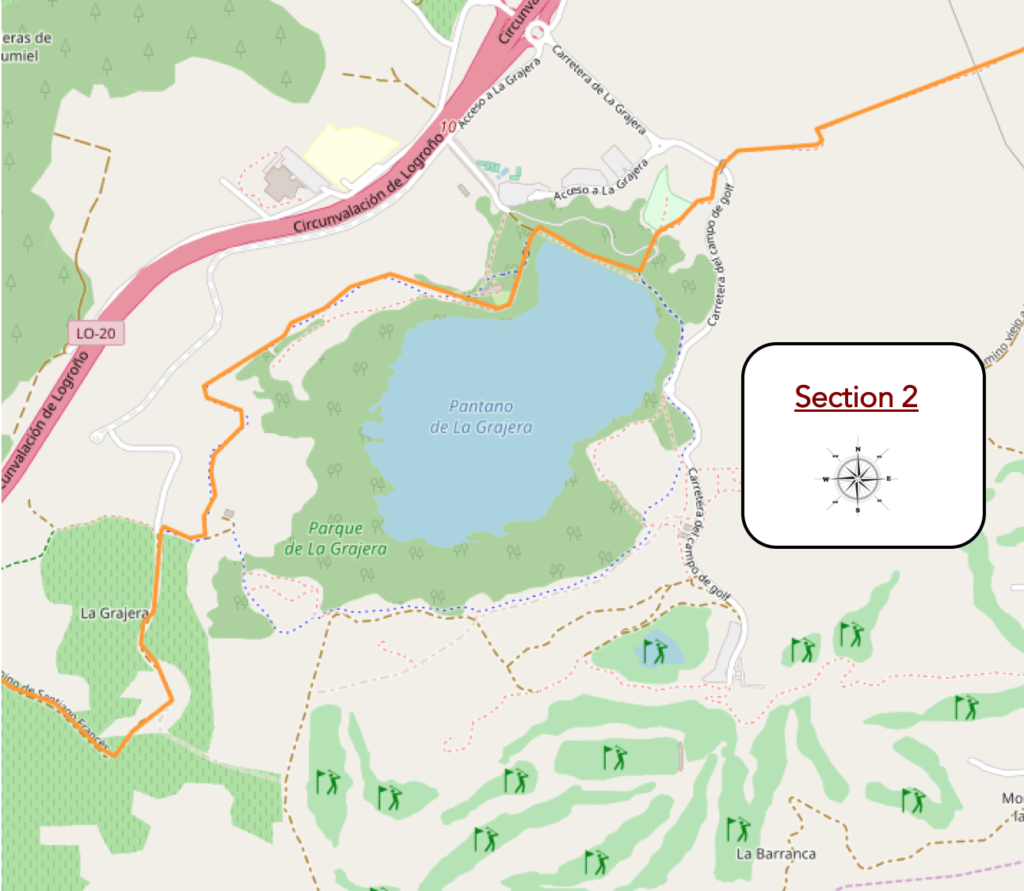

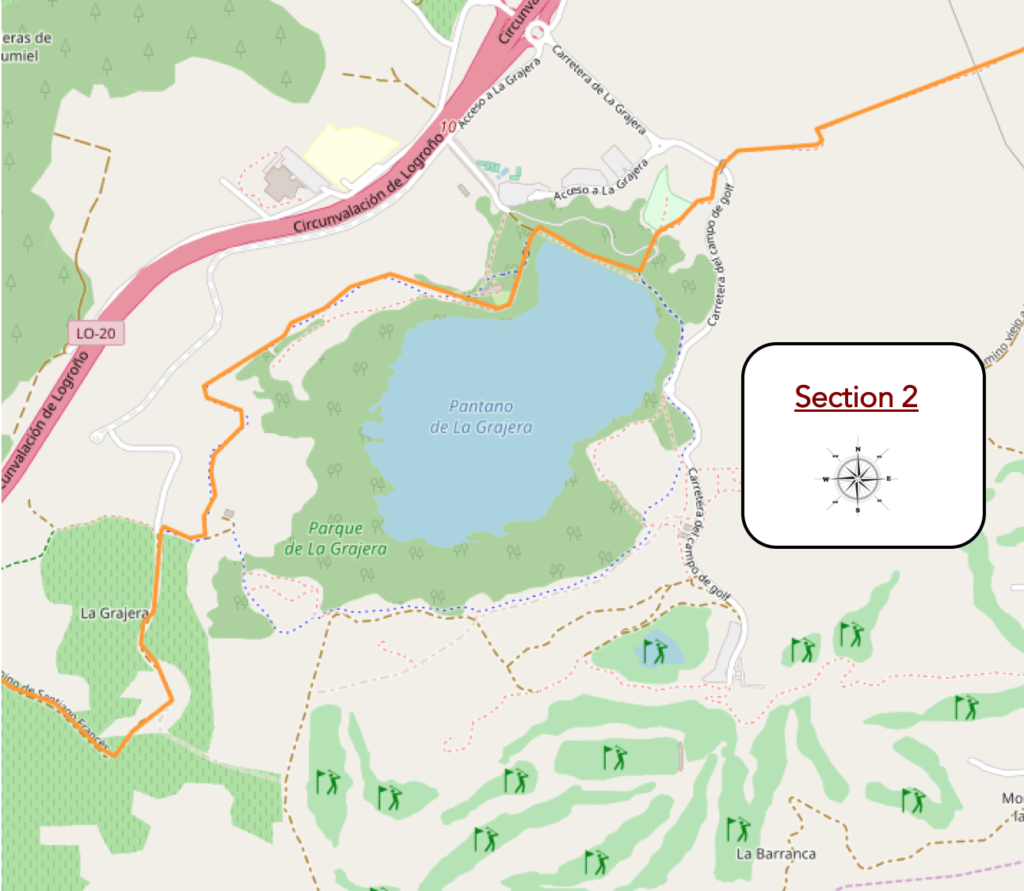

Section 2: Through the beautiful park of Grajera.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| A small paved road then flattens to the plain. Here, you’ll find again the symbolism of the Santiago track on the granite poles, those that you found when arriving at Logroño. Now, the rain redoubles, and the wind rushes under the capes. |

|

|

| The road crosses meadows and cereal fields under poplars. Here, white poplars were added to black poplars. There are also maple and almond trees. |

|

|

| There are even benches to take a break. But today, we will not be careful. |

|

|

| Much further, the straight road turns on the approach of a pine wood. |

|

|

| The paved road soon arrives in the middle of the joggers in the park of Grajera, who apparently don’t hate drizzle. |

|

|

| At the park, there is everything necessary to please families. |

|

|

| It is a beautiful park with a large body of water. We imagine that under the sun the lake is not tinged with this gray, sinister color. But, bad weather must not disturb the fish. Today only fishermen are active in the area. |

|

|

| The park has a didactic room and a bird observatory. This park is beautiful, even in the rain. A pathway winds through the pine forest, where huge black poplars and maples also climb to the sky. There are even eucalyptus trees here. |

|

|

| A little further, the pathway is wider under the pines, in the great sweetness of the park, today greatly disturbed. |

|

|

| Today, at the end of the park, the sky becomes even darker, the color of ink. The rain begins to redouble with violence, cold, and a terrible wind of face joins the festivities. The water runs on the pilgrims and drips on the fronts. So, a shelter allows some to readjust their rain gear. But, it is little thing in this turmoil. |

|

|

| A vineyard route then leaves the park to reach the vineyards of Rioja alta. |

|

|

| Today, we will not want to see if the tempranillo grows next to the monastel, or to check the Internet to see if Parker has distributed notes above 90 in this area of the vineyard. But, this region, even if it can give good wines, no one doubts, is not the land of choice of the greatest wines of the Rioja appellation. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road, that becomes quickly a dirt road, starts to climb in the vineyard. |

|

|

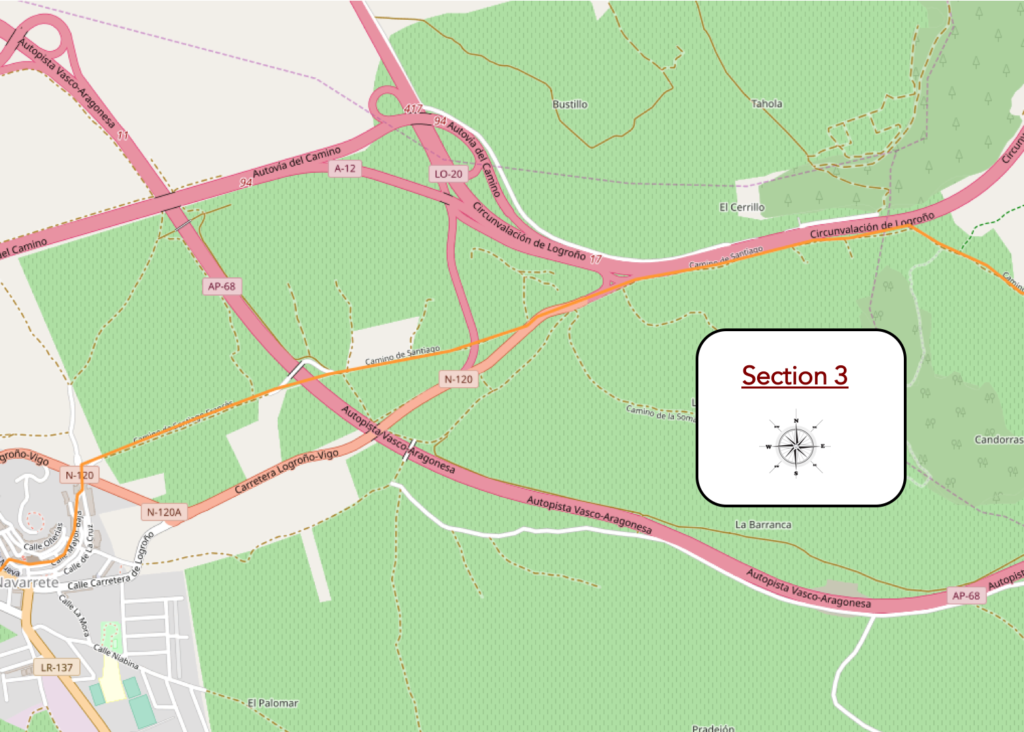

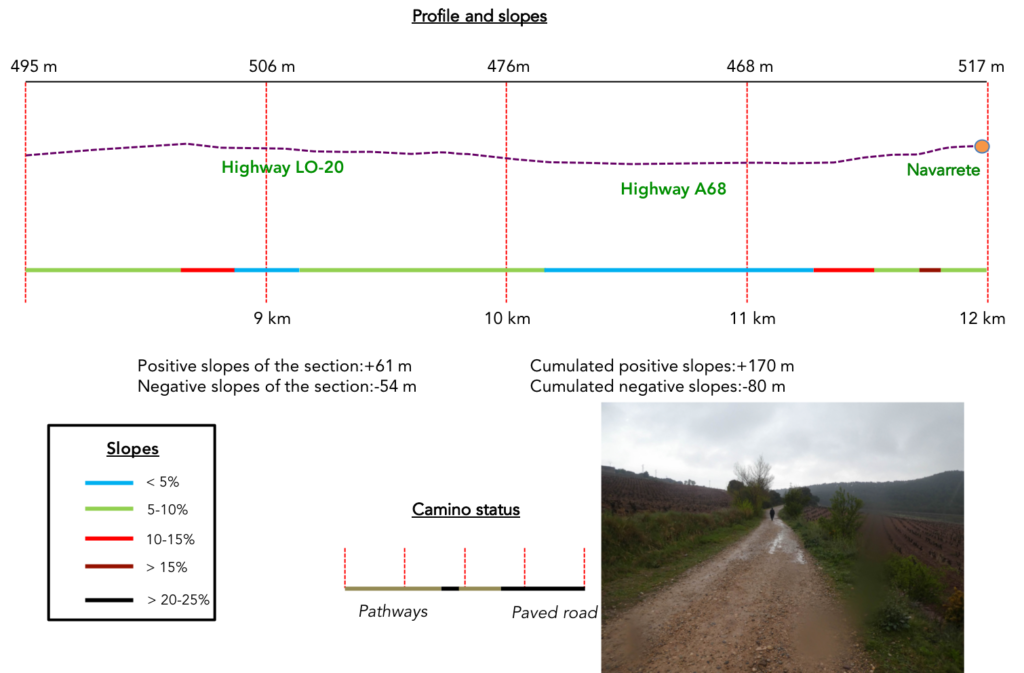

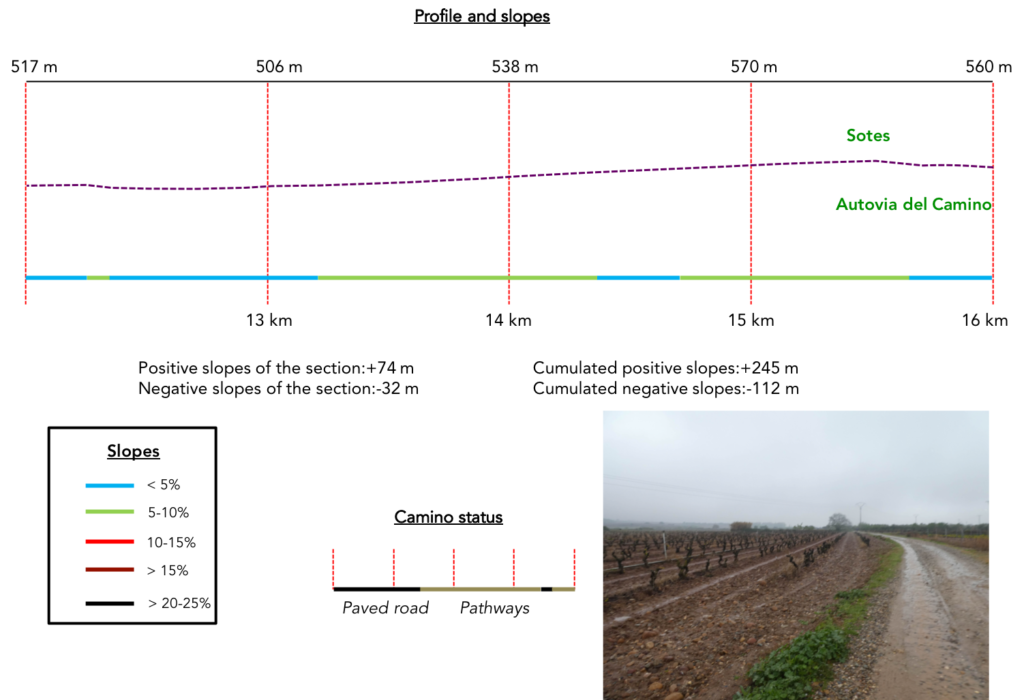

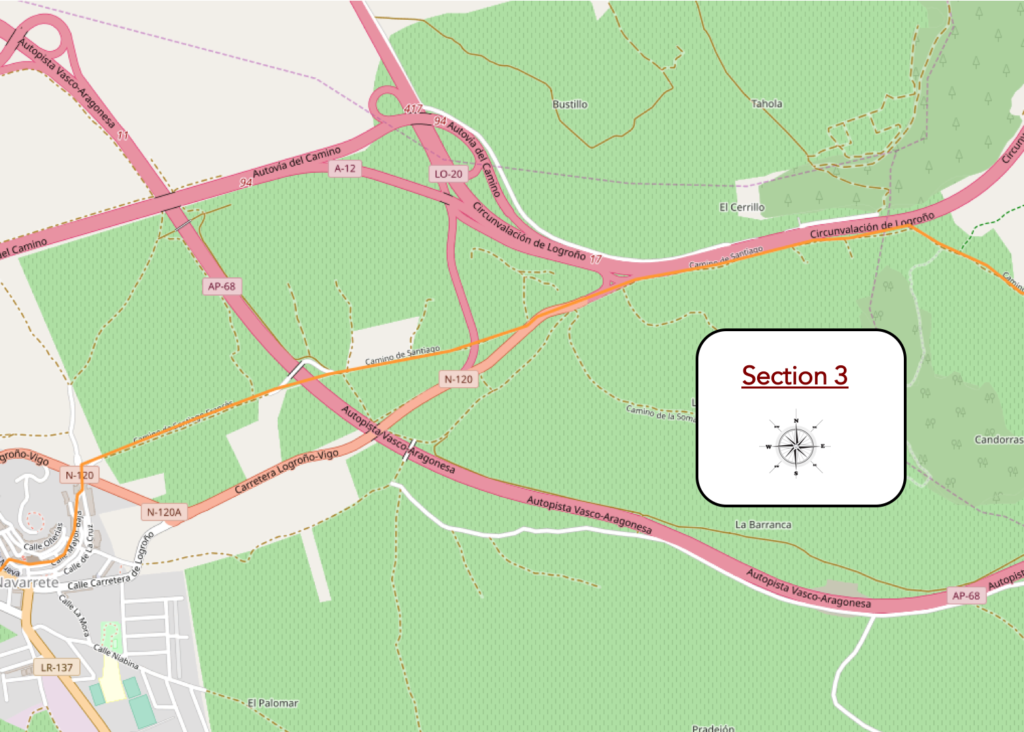

Section 3: Vines and highways.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, but two small sections with steep slope, just before the highway and then to climb to Navarrete.

| Further up, a stony pathway, which gradually gulps, replaces the tar and continues to climb in the vineyard. The slope is steep when the road arrives at the level of the LO-20, the highway bypass of Logroño. The wind is so violent that it rushes under the capes badly closed, and the rain squirts in the face. |

|

|

| Today, it’s almost dark on the soggy path along the ramp. The atmosphere is sinister, almost nightmarish. May you walk a good day here, even if the highway will be more visible. |

|

|

| In this industrial area, even the bull perched on the hill, the emblem of Spain that is often found along the highways, does not give any comfort to the pilgrims who grumble under their cloak. We hardly met any pilgrims in this stage who said they liked Spain. |

|

|

| Then, the highway ramp takes another direction and then appears the N-120 road. The pilgrim will start a small piece of serenade with this national road. The N-120 road will become for some a nightmare for an infinite number of days. For fun, this route goes to Vigo, in the depths of Galicia, at the edge of the sea. But rest assured, it will be abandoned sometimes. |

|

|

| Yet here, the pleasure on this road will be brief, and quickly you’ll find a dirt road, today mired at will, which slopes down into the vineyards. The land here is red, with its big limestone pebbles, an ideal terrain for the vineyard, right? |

|

|

| In front of you, you can guess Navarrete, drowned in the mist and the downpour on the hill. |

|

|

| The pathway gets closer until it crosses the Vasco-Aragonese highway. The region is a real fabric of highways and national roads. |

|

|

| Beyond the highway, the Camino takes a small road that heads to the ruins of an old pilgrim hospital, St Juan de Acre, founded towards the end of the XIIth century to lodge and aid pilgrims. Excavations have brought to light the main walls of the old hospital, a large church and a tower, as well as some burials. San Juan de Acre (Saint John of Acre) is the name the Knights of the Order of Malta gave to the ancient Israeli city of Acre after its capture during the Third Crusade. In the XIXth century, the hospital was destroyed and the remains used for construction. The beautifully carved entrance porch has been repositioned as the gate to the cemetery that we will find on leaving Navarrete. |

|

|

Behind the building stands a large cellar. We do not want to advertise, but we will say that here, the domain of Don Jacobo, also associated with the Way of Compostela, produces one of the most celebrated wines of Rioja.

| The paved road then approaches the village, clinging to the hill. |

|

|

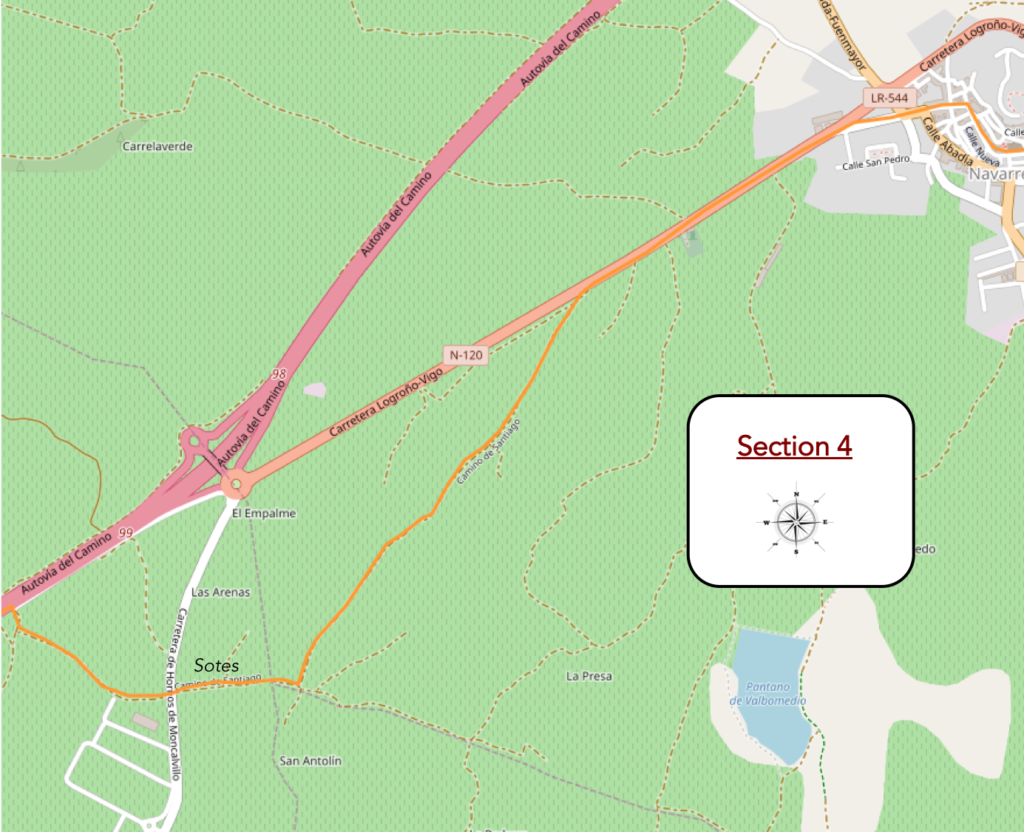

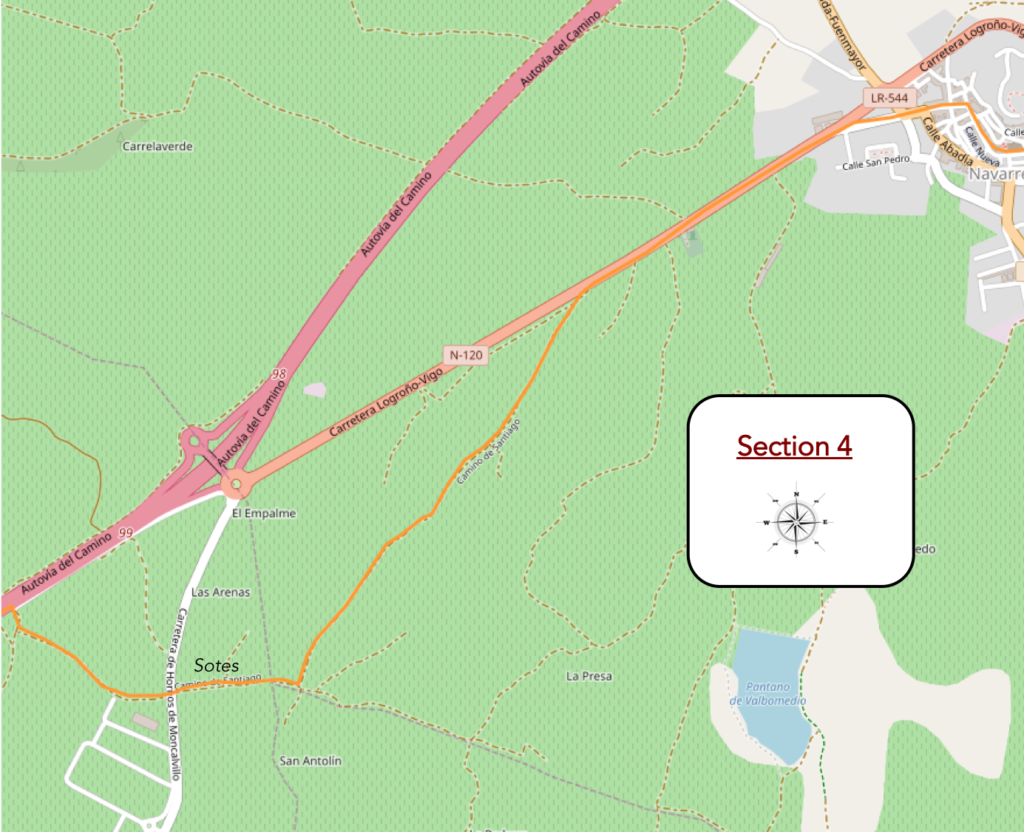

Section 4: A pretty village, before returning to the vineyards.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The road climbs fairly steeply towards the village and stairs lead up to the bottom of the village. The city was founded by the King of Castile as part of a plan to defend its borders, and the name has a link with the neighboring kingdom of Navarre, the word Nafarrate in Basque meaning “Gateway to Navarre”. When King Alfonso VIII of Castile, in the XIIth century, recovered this part of La Rioja from the Kingdom of Navarre, he proposed to the inhabitants of the old villages of the area to make it a defensive place, which took the name of Navarrete, for a best defense against Navarre. |

|

|

| Pilgrims hasten their pace to find a little comfort in the “albergue” to avoid the rain for a moment. Let’s be honest. In rainy weather, the atmosphere is discreet, contained in the cafes. Everyone is thinking, alas, of the moment when they will have to harness their cloak again. |

|

|

| At the beginning of the XVIth century, the old church of Navarrete, located at the top of the hill next to the castle, was already uncomfortable and small. Thus, it was deemed appropriate to seek a license from the Bishop of Castile to build another church in a wider and lower location. But the church became too small in the XVIth century. The current Iglesia de la Asunción is a Renaissance church of considerable size, whose construction lasted almost a century, completed in the XVIIth century, with the pyramidal spire tower. It is so dark inside the building you can barely see the gold and bronze of the baroque altar whose beauty is praised. |

|

|

Will people one day organize fashion shows to praise pilgrim equipment in the rain? If so, the latter would probably have had the palm.

| In the village, there are many houses with exposed bricks. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino runs for a few hectometers on N-120 road. |

|

|

| The Camino heads to the cemetery which has the very beautiful portal which hesitates between the Romanesque and the Gothic of the XIIth century, with Mudejar, Arabic influences, which comes from the old San Juan de Acre hospital. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino runs along the N-120 road for a few moments, before going on a dirt road. |

|

|

| You can see a few fruit trees along the sodden ground. |

|

|

| Further on, the course leaves the road for olive trees and vineyards, with the immeasurable joy of wading through the mud. You will clean ourselves in the evening at the “albergue”. At the bend in the pathway, a pilgrim slipped surreptitiously on a terminal. |

|

|

| We sink up to our ankles in the mud that lines the pathway. The mud clings to you tirelessly, engulfs you, hinders you. In the pounding rain, you no longer even want to look at the surrounding vines, engulfed under your hood, which is crying profusely. |

|

|

| It is now raining so hard that sometimes the pathway turns into a real lake and the pebbles glisten in the vines. It is a small game of duck over almost two kilometers. Just that! |

|

|

| The grueling little game continues until you approach the Sotes wine estate. |

|

|

| Here, a short stretch of paved road. So, you see some pilgrims rubbing their shoes for a long time in the grass, then advancing on the saving tar. |

|

|

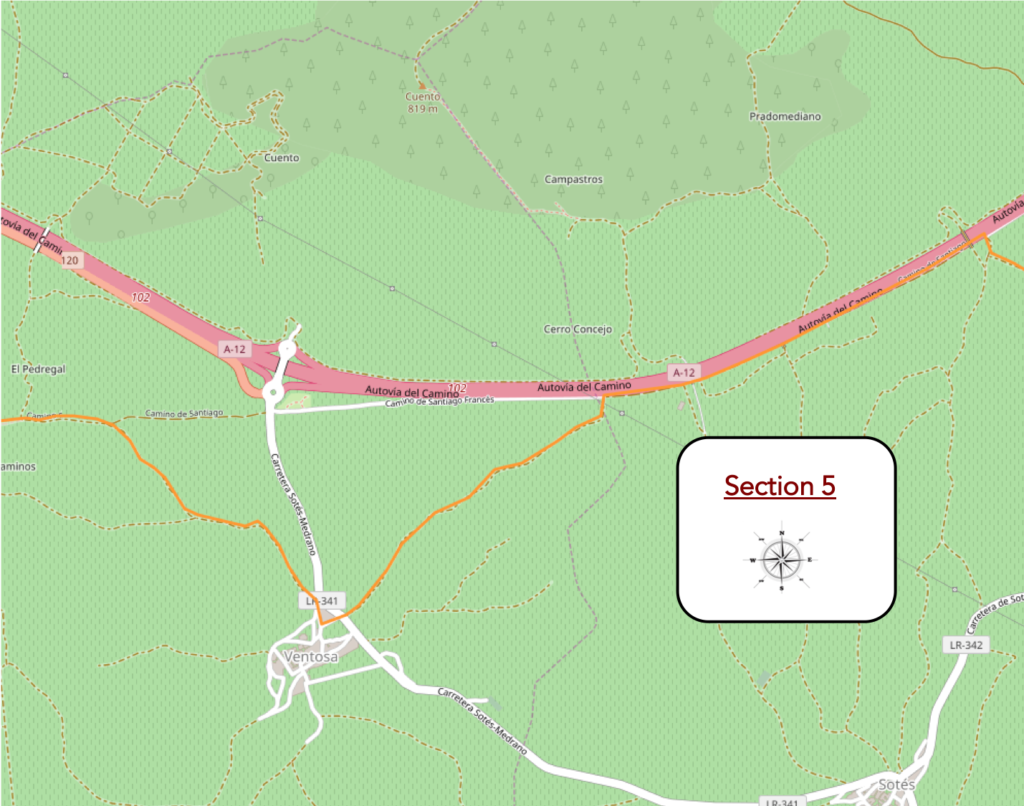

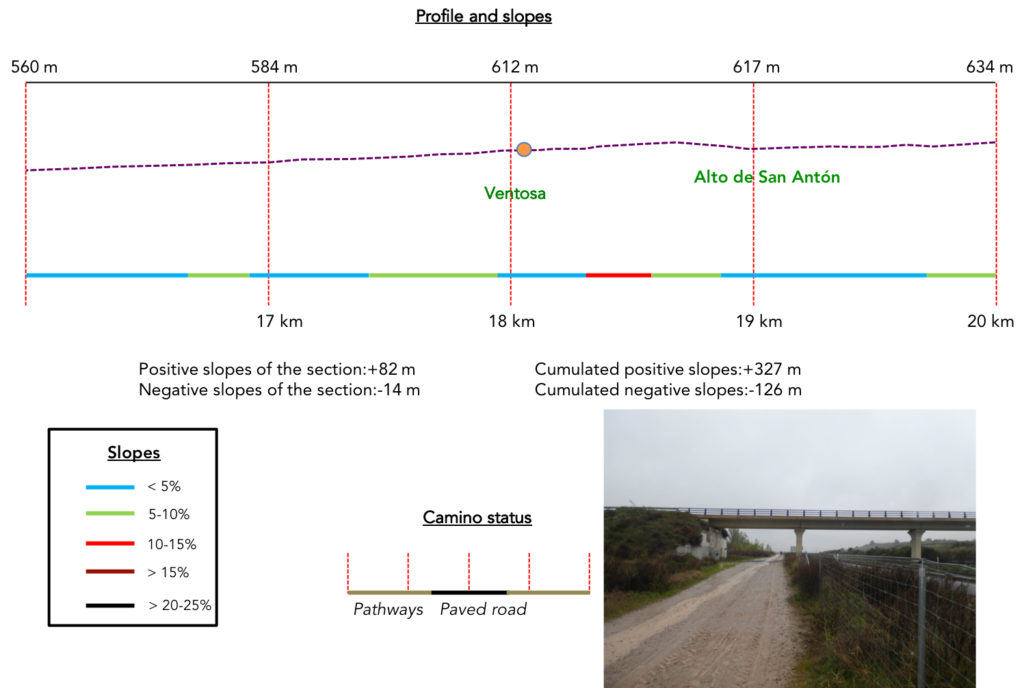

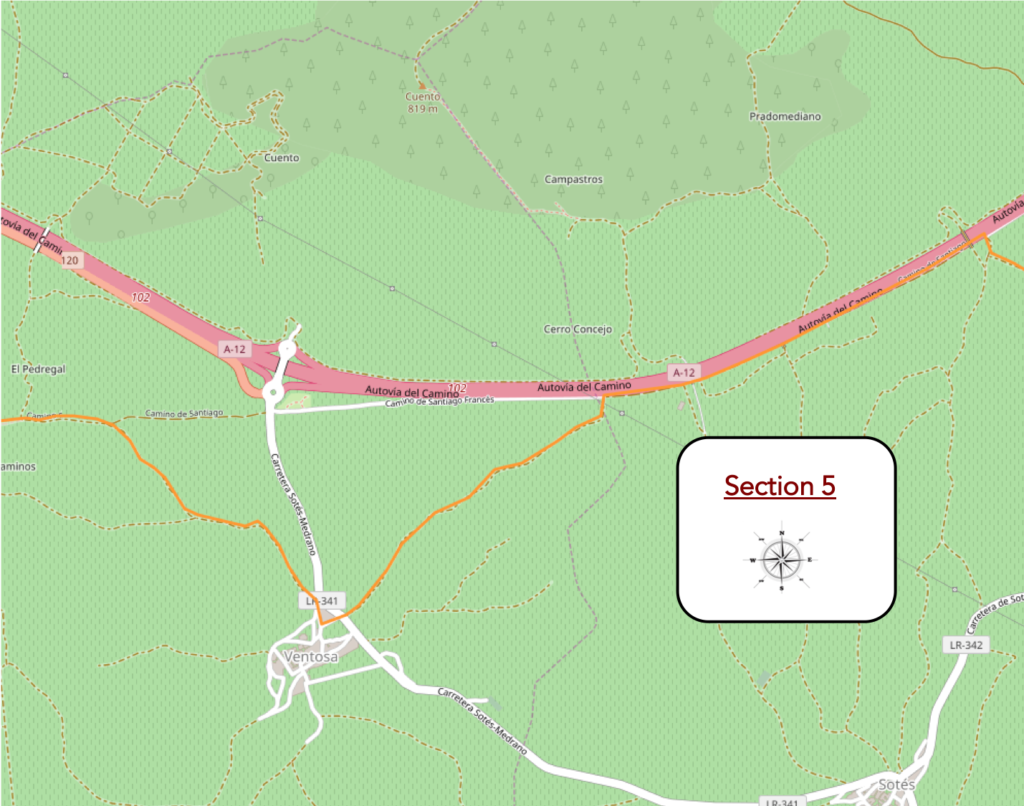

Section 5: A small stretch of highway to vary the pleasure, then again, the vines.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: just a little effort beyond Ventosa.

| But, the paved road is soon away… |

|

|

| …and, for us today, the mud takes its rights little by little, when the Camino arrives near the highway A-12, the big highway of the north which goes down from France towards Burgos. It is the Autovia del Camino, the highway of the Santiago track, that, when you will travel perhaps in summer, you will see an army of pilgrims suffering under the heat wave. |

|

|

| Here, you have about 2 kilometers walk between the vineyards and the highway. Here you are not in Germany, where the trucks are moving in line. The circulation is discreet. In Spain, there are virtually no villages or so few between cities. Therefore, people do not often leave their scope of activity. |

|

|

The wind and the rain are relentless and you are in a hurry to finally get out of your prison of red or gray clay that is trapping you.

| At the end of an endless straight line, the dirt road leaves the highway and cereal fields appear among the vineyards. Here, the Camino flattens on a paved road in direction of Ventosa. In the past, the track continued along the highway. Have they had pity for the pilgrims by diverting the way to the village? Or was it to give the village a little more purchasing power? |

|

|

| The road leads fairly quickly to the village of Ventosa. The village had a pilgrim hospital in the XIIth century. Its XVIth century Gothic church, dedicated to San Saturnino, is away from the road, in the village. With the rain that persists, we will not make the detour. |

|

|

| In this village of winegrowers, indications of tracks whose meaning we have not understood. But anyway, just follow the shells so you don’t get lost! |

|

|

Immediately, a pathway leaves the village in the vineyards.

| You can’t see a drop of it today in the increasing rain and the trailing fog. And when you walk in the mud, the difficulty is to take off the sticky sole and the foot weighs tons. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino gives you a little pleasure giving you the opportunity to warm up. It momentarily leaves the vineyard to climb long enough through brush, large stones and holm oaks to pass under the Alto de San Antón. |

|

|

| Alto de San Antón is the site of a former pilgrim hospital established by the Antonine Order. Nothing remains of the hospital or the monastery associated with it. A little further, the pathway leaves the scrubland, the large ocher limestone and climbs a little further, finding the vineyard back. |

|

|

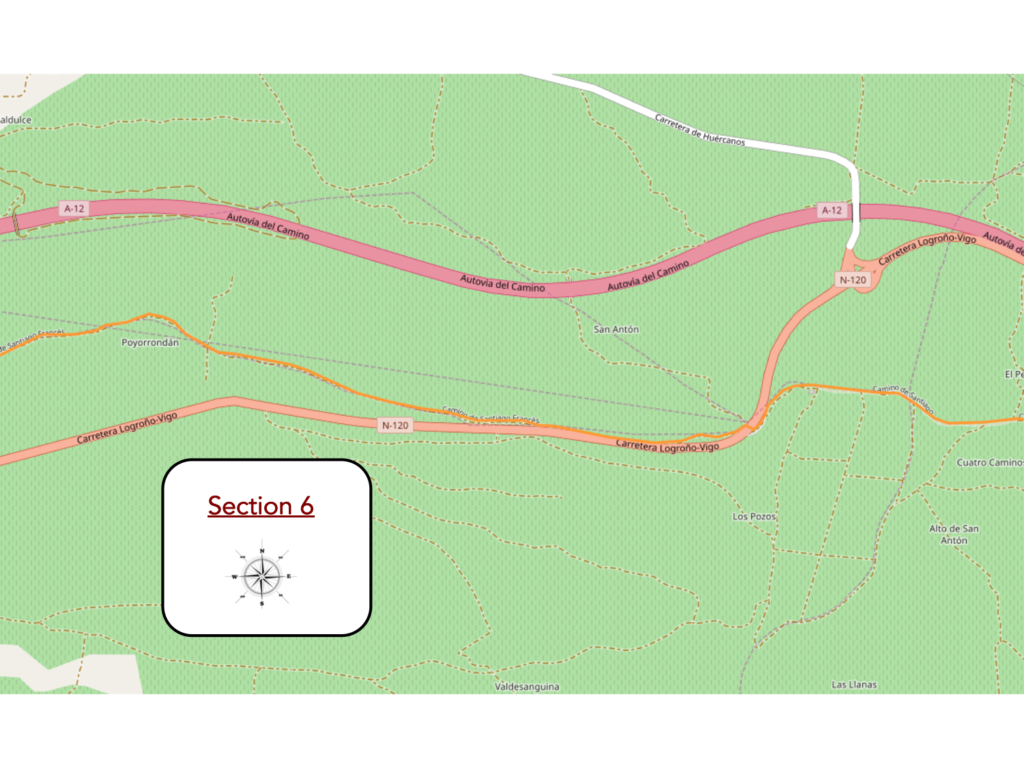

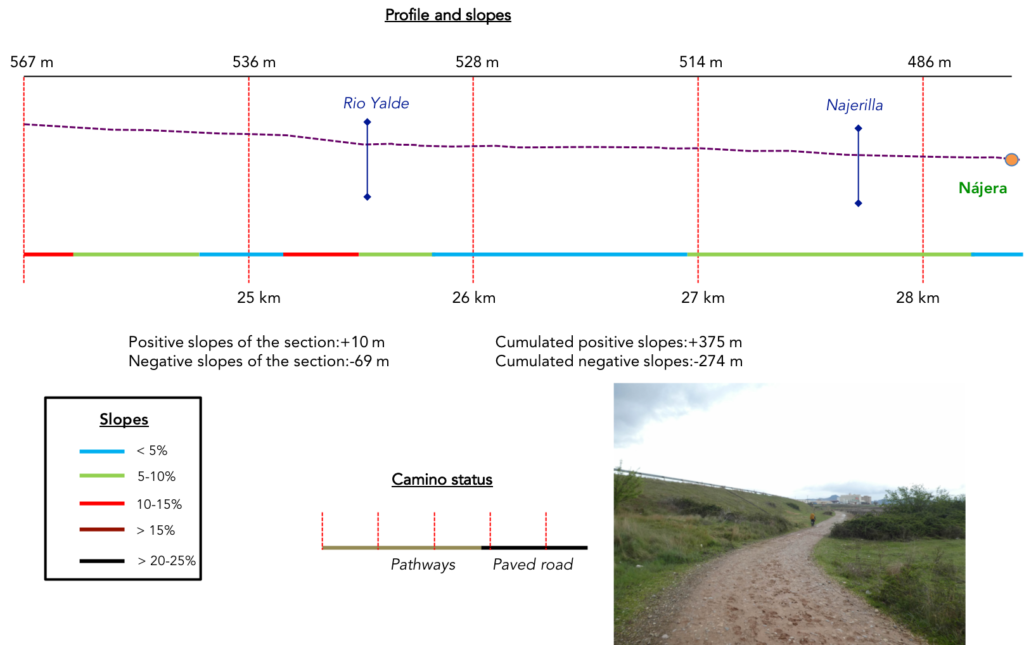

Section 6: Still and always in the vineyards of Rioja.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: descent above all, without difficulty, even if the slope is sometimes more important.

| In the vines rich in red clay and large limestone pebbles, the vines are sometimes organized on wires or trellises, but very often also free of any constraint. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway slopes down again in the vineyards to pass on the other side of the N-120 under the black poplars. The national road runs here not very far from the A12 motorway. Luckily for us, now the rain has stopped and the fog has lifted, but the ground remains soggy to the core. |

|

|

| The pathway then runs along the national N-120 road in the vineyard. In summer, it must be very hot around here. Not a tree for protection, or so little. |

|

|

| Irrigation systems run in the vineyards. Here, they protect the new vines. Are there animals that roam the area? |

|

|

| Shortly later, the pathway leaves the axis of national road to run deeper into the vineyards. There, in front of you, the television antenna on the hill will become your landmark for a few tens of minutes. |

|

|

| It’s long, very long to the antenna. The usefulness of the landmarks in the lengths of the track must be overemphasized. Getting close to it encourages many pilgrims to take one step in front of the other. At the bottom of the hill, an industrial zone is emerging where the N-120 road runs. |

|

|

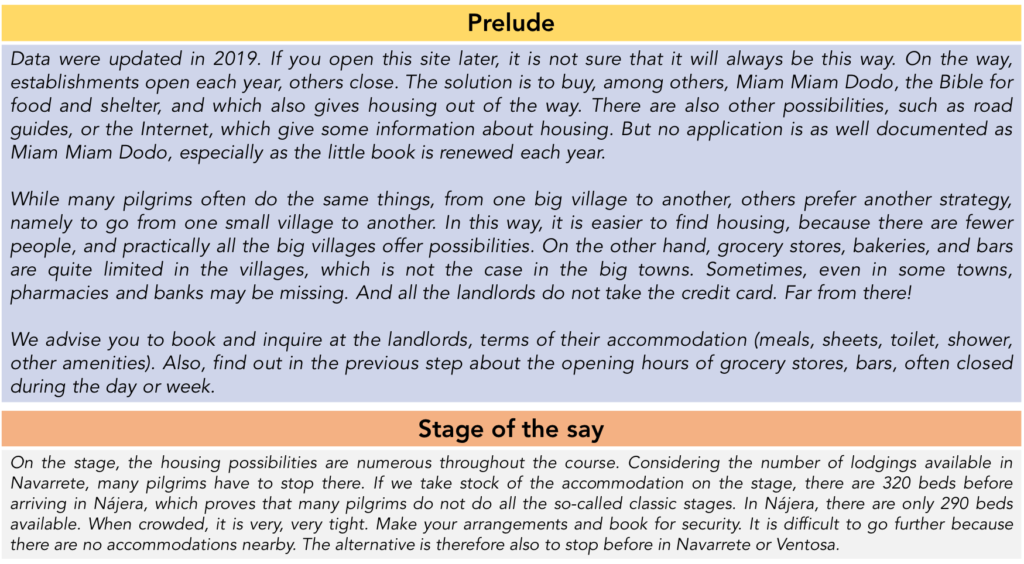

Section 7: On your way to the citadel of Nájera.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: descent above all, without difficulty, even if the slope is sometimes more important.

| The pathway then skirts the hill and its antenna in the vineyards. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino descends on the other side in a wide pathway, sometimes steeper. |

|

|

| Further down is the Poyo de Roldán, poyo meaning hill. It looks like a heap of pebbles of no great importance. The place is linked to a legend similar to that told in the Old Testament and which continues to this day. It is said that in the castle of Nájera lived Ferragut, a Syrian giant descended from Goliath, who defeated the best warriors of Charlemagne except Roland (Roldán), nephew of the emperor, who came to this place to free the Christian knights imprisoned by the giant. While on a bench, he saw the giant sitting at the gate of his castle and threw a heavy stone at him which hit him in the forehead causing his death. Since then, this hill has acquired its name. A reference to this legend can be found in two capitals in the village of Navarrete. It is also the place where a huge treasure is said to be hidden, as payment from the local inhabitants to the French captains of Roland.

Another version comes from the Codex Calixtinus, in Book 4, Chapter XVII. It is said that Ferragut, in a moment of truce, would have entrusted Roland with his secret of invulnerability. He could only be injured in the navel, a method the latter used to end his life by stabbing him with a dagger and freeing the Christians. This scene can be seen in the former palace of the kings of Navarre in Estella. How beautiful are legends! For another it was the heel, for him, it was the navel. In any case, this myth permeated the Jacobean world, which represented the two characters in various monuments. At the bottom of the descent, the pathway arrives in an industrial area. For the happiness of the pilgrims, today the rain has stopped. |

|

|

| The pathway then descends towards the industrial area which is far from rising in charm, as almost all suburbs often do. Here the pathway comes to a crossroads near a gravel pit. |

|

|

| At the crossroads, the Camino continues straight. |

|

|

| Here, you have to be careful, the course is not very well indicated. You see many pilgrims who are mistaken. You have to find the small wooden bridge that crosses the Rio Yalde… |

|

|

| …and continue on the vacant lot, pass under the piles of a bridge and find a small picnic park just behind. |

|

|

| The approach to the city is not the most elegant, in the wastelands, the industrial zone, near a large flour factory. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway crosses a canal and in the wasteland heads again towards the N-120 road. |

|

|

| The route then crosses the N-120 which bypasses the city and continues on a wide dirt road towards the suburbs. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino enters the new part of the city (8,000 inhabitants).. |

|

|

Section 8 : Short visit to Nájera.

| Nájera is divided into two parts separated by the Rio Najerilla. The Camino first crosses the new town, which is, without insulting the inhabitants of the city, a part without much interest. |

|

|

| Then, the Camino reaches the river. The old city appears at the foot of the red cliffs. The Arabs gave it the name of Náxara (place between the rocks). There was here in the XIIth century, a beautiful seven-arch bridge built by Santo Domingo de la Calzada and San Juan de Ortega, who did so much for the Santiago track. This bridge has long since disappeared, and the current bridge dates from the end of the XIXth century.

When the Muslims left, the city was taken over by Ordoño II of Galicia and León for his ally, Sancho I Gracés, King of Navarre. But, at that time, the Muslims pillaged and destroyed Pamplona, forcing the king to move the court from Navarre to Nájera. In the XIth century, King Sancho III modified the Camino route so that Nájera became an important stopover for passing pilgrims. It was the capital of the Kingdom of Navarre in the XIth and XIIth centuries. It remained the capital of Navarre and La Rioja until the end of the XI1th century, when La Rioja became part of Castile. But, as we said above, Rioja spent most of its history until the autonomy of 1982 under Castilian domination. |

|

|

|

|

| There is not much left of its former capital rank. But, the old city is full of charm. Here, you do not need a detailed plan to circulate in the city. Just orient yourself in relation to Calle Mayor, the beautiful shopping street. |

|

|

| Santa Cruz church, the parish church was in the XIIth century a chapel dependent on the great monastery of Santa Maria Real. It was not until the XVIth century that it became independent. This stone building mixes all styles, from Gothic to neoclassical, but is especially noticeable by its cupola and lantern, and its beautiful Christ. Here, too, they were preparing the statues for the Holy Week processions. Alas, you know that they will just arrange them for the next year, if time allows it again. |

|

|

|

|

| But the monument of the city is the Monastery of Santa Maria la Real, founded by the King of Navarre in the XIth century, King Don García de Nájera in homage to the Virgin, whom he discovered here while hunting doves, a statue in a cave. The king ordered the construction of the building as an episcopal seat, family vault and monastery originally for the monks of the Order of San Isidoro. The original Romanesque church with Mozarabic influences was consecrated at the end of the XIth century. The walls were high for defensive purposes and the buttresses functioned as bastions. Built on the remains of an old Romanesque church, the current church is Gothic, completely rebuilt in the XVth and XVIth centuries, where the Gothic and Renaissance styles intertwine. Seen from the outside, the building appears severe, like a large fortress, with a large quadrangular tower. But, in fact, this austere building is a royal pantheon. It includes the Royal Pantheon of the Kings of Navarre and later of Castile and León. More than 30 members of the royal family are buried there. It also houses the Mausoleum of the Dukes of Nájera. Flash photos being prohibited, we will not be able to show you images of the church, the Baroque cloister, the grotto and the Romanesque tombs of the crowned heads, decorated with so much grace and finesse. But, it’s beautiful, go ahead.

Then, over the centuries, as the popularity of the Camino de Santiago waned, so too did the fortunes of the monastery. At the beginning of the XIXth century, the monastery suffered attacks and looting both by French troops and by guerrillas during the war of independence. At the beginning of the XIXth century, by anticlerical pressure, the monks had to abandon the monastic complex, which was then vandalized and suffered significant damage. The building was then used as a warehouse, school and barracks, until it was declared a National Historic Artistic Monument in 1889. |

|

|

|

|

| Attached to the Convent of Santa Clara stands the Church of Maria de Dos, a complex built in the XVth century to serve as a hospital for the poor and pilgrims. Today, the church and the house are the private property of the descendants of the founders and the brotherhood. |

|

|

| The originality of the city is undoubtedly this great wall of shale clay, large reddish blocks against which is backed the city. It’s like a western setting planted in nature. These large walls, which are the Mota and Malpica above the city, where vultures and storks fly, are real Emmental cheese (Gruyeres does not have holes), created by the rains which attack with pleasure this friable material, a universe where they have taken refuge during centuries the vagabonds. But the pilgrim has little time for speleology. And it started raining again. The castle of La Mota, the Alcazar and the Malpica, perhaps the pilgrim will come back to visit, to stroll up there in the old fortresses and ruined castles of the city, built by the Muslims first then by the kings of the region. Tonight, he will just fantasize about this since his “albergue”. |

|

|

| Of course, the beauty and charm of places is always a function of time. This is what the great wall of shale by the river looks like in another period, in good weather |

|

|

| Under these conditions, the two monuments of the city seem less austere |

|

|

| And the weather then lends itself to allow people to gather at the edge of the river, on holidays. |

|

|

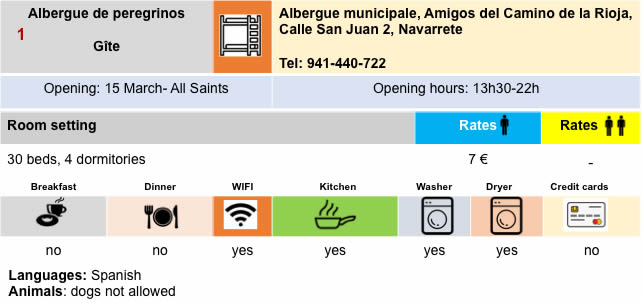

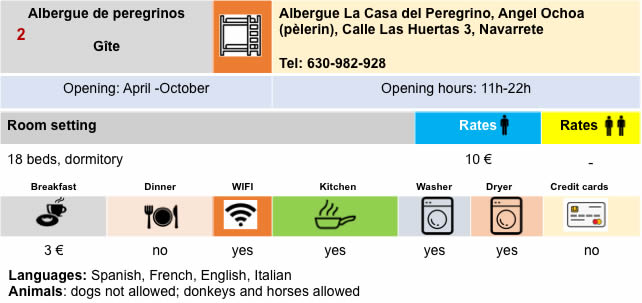

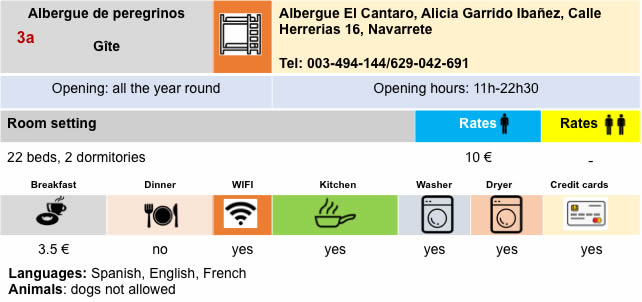

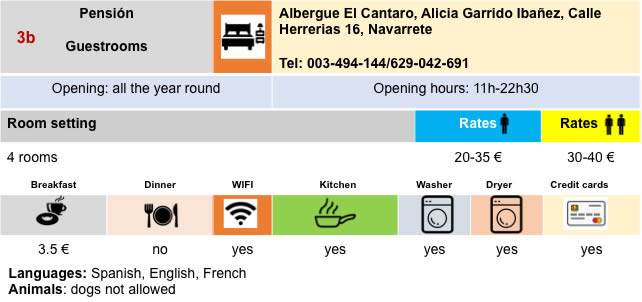

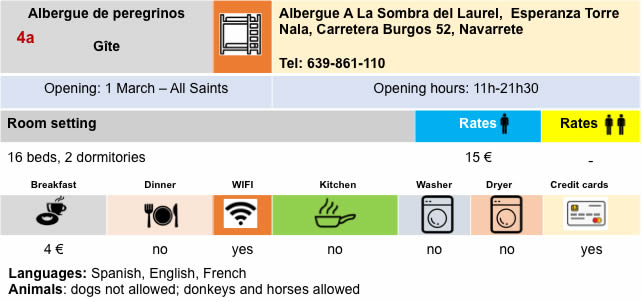

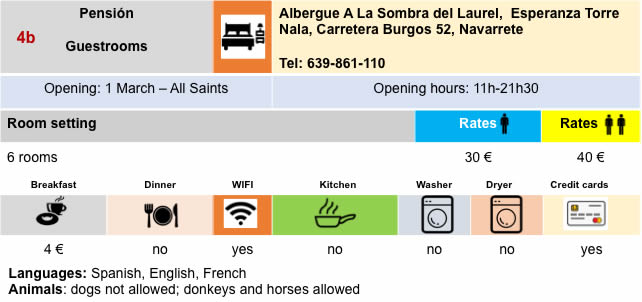

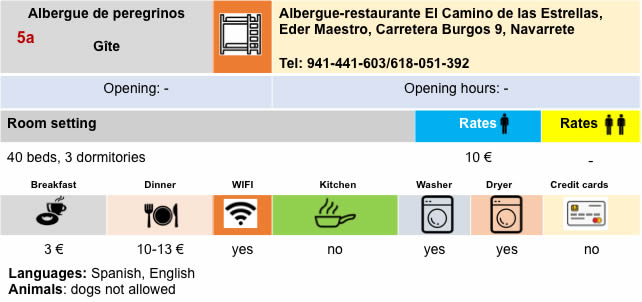

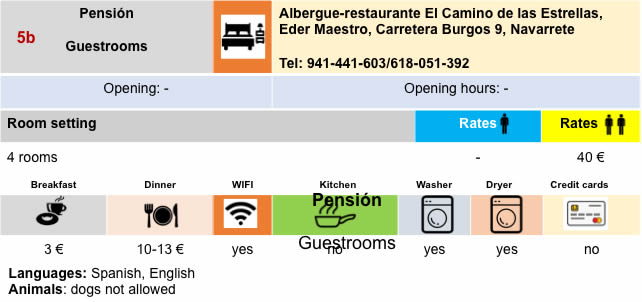

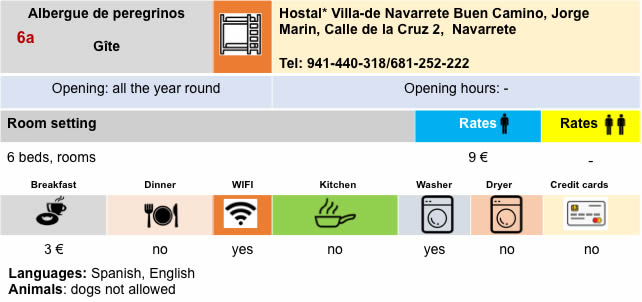

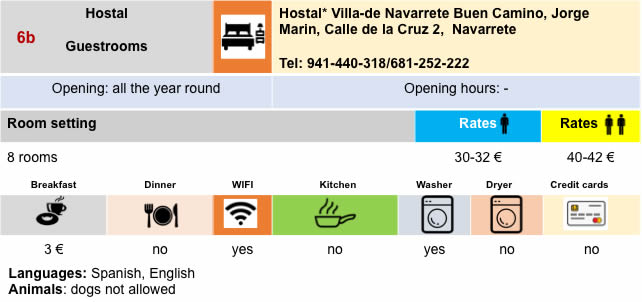

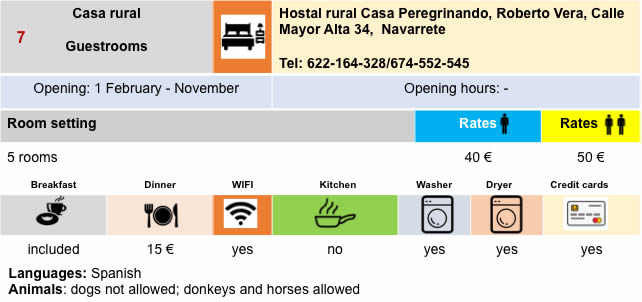

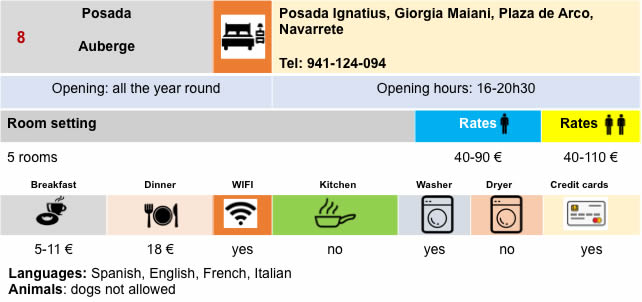

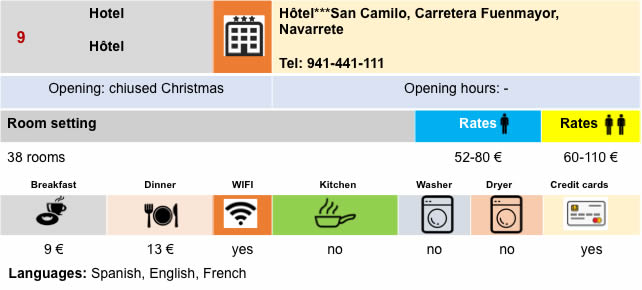

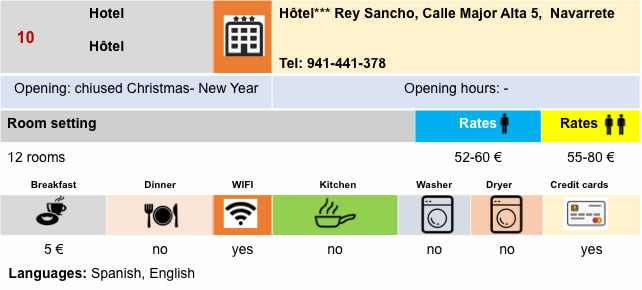

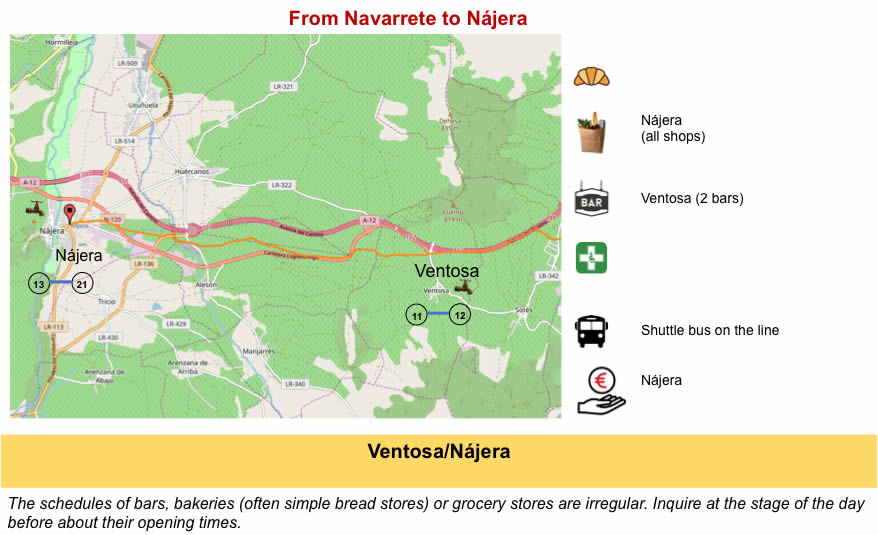

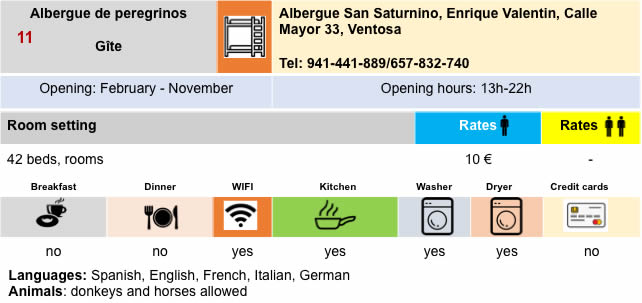

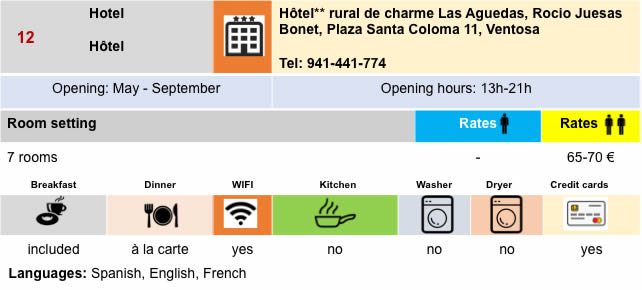

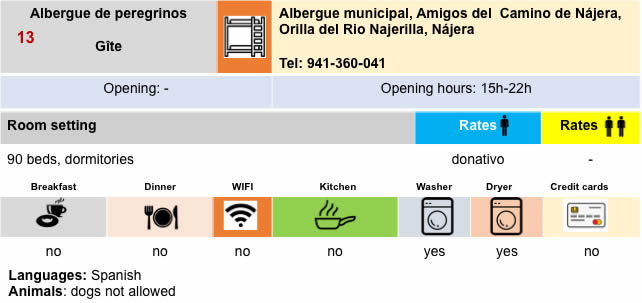

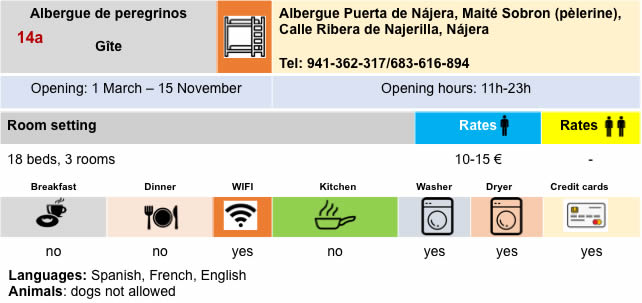

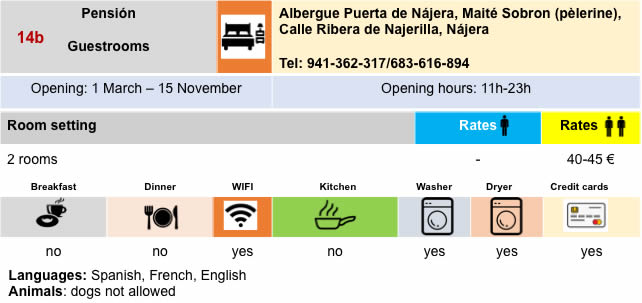

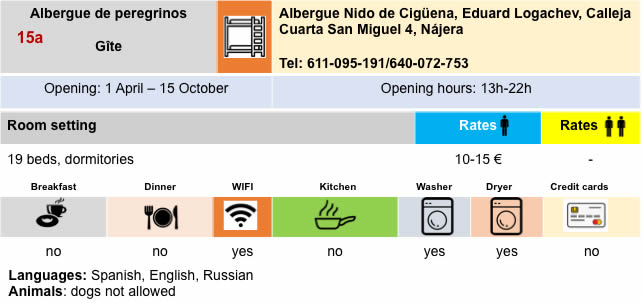

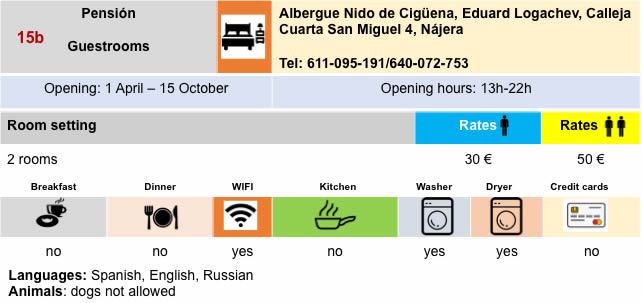

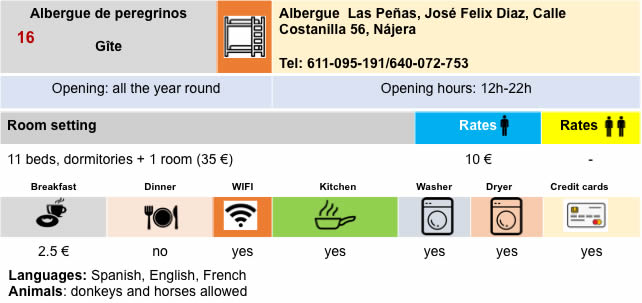

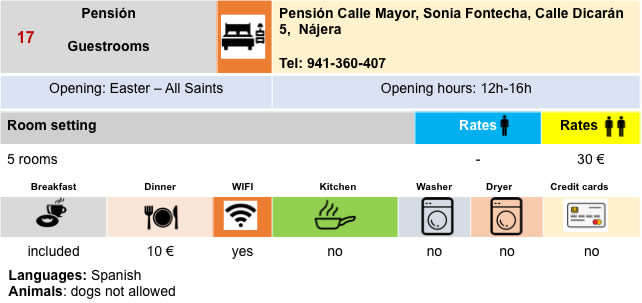

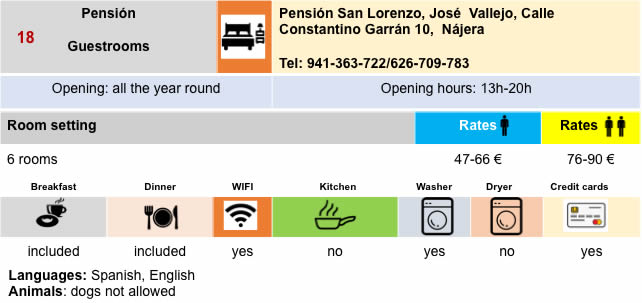

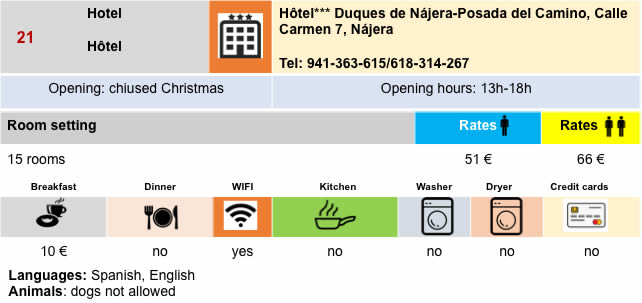

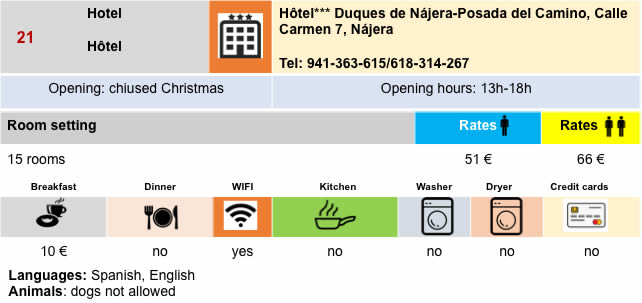

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 9: From Nájera to Santo Domingo de la Calzada |

|

|

Back to menu |