At the house of the good Santo Domingo de la Calzada

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

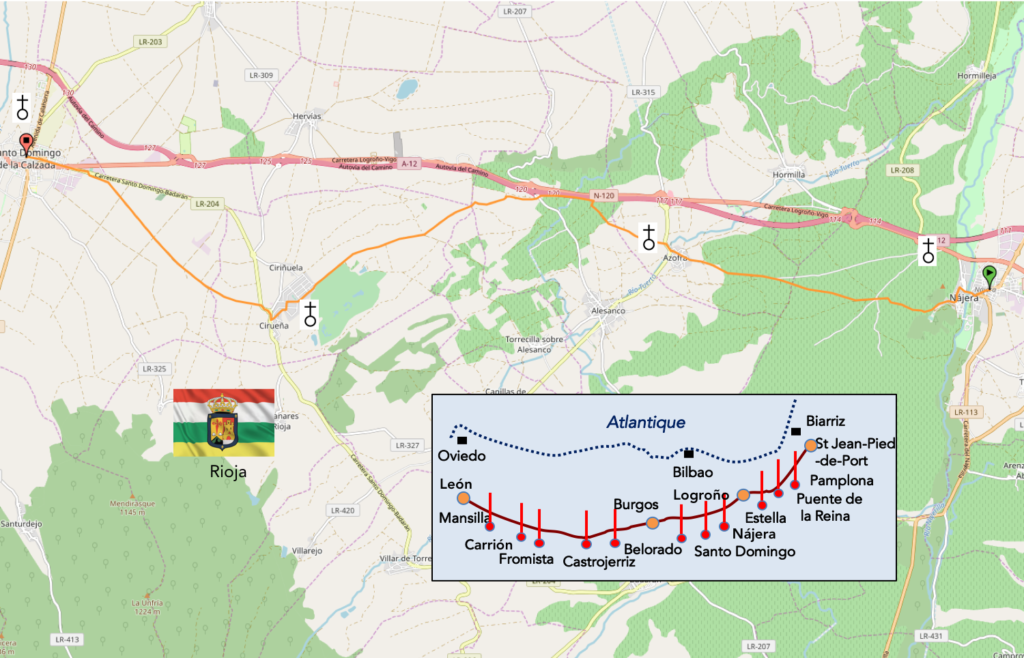

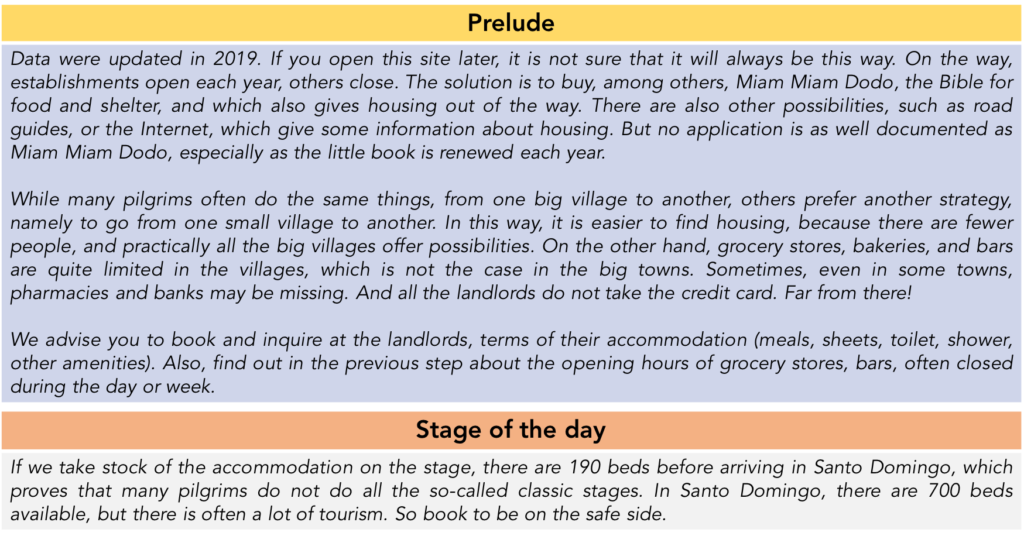

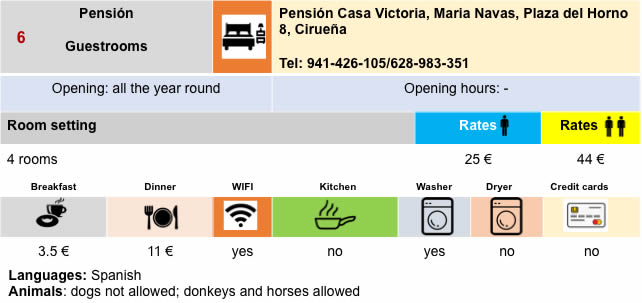

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-najera-a-santo-domingo-de-la-calazada-par-le-camino-frances-33771724

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

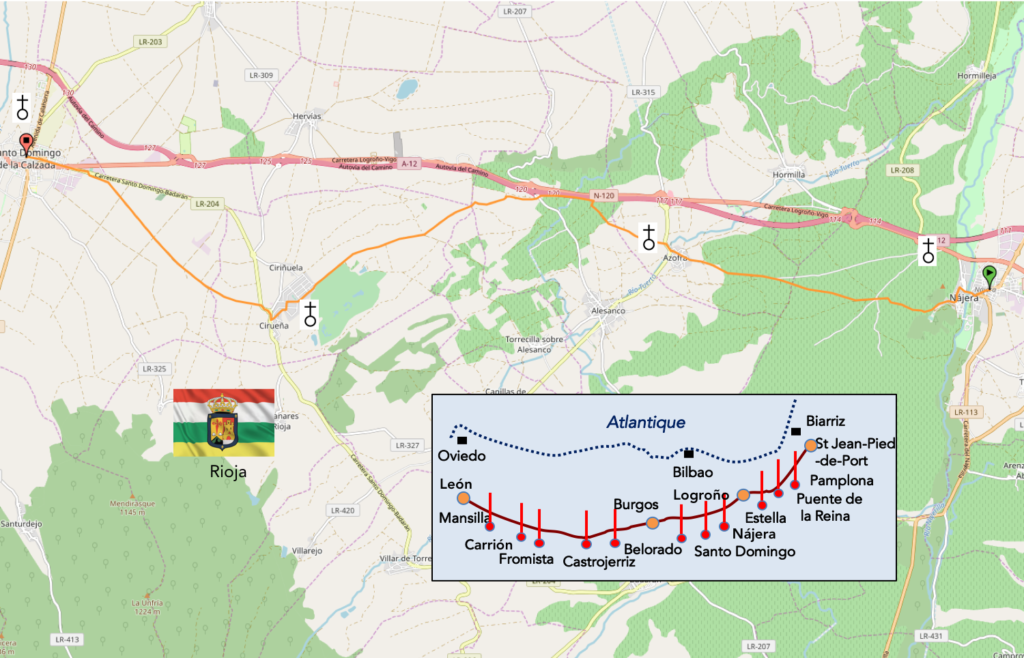

In the stage of the day, the Camino francés enters Rioja, in the middle of the vineyards. Unfortunately, it is raining today, and we will not be able to taste the charm of the vines. We will spend most of our time in the mud and we will just eye the vineyards or the rarest cereal fields of the region. What a pity! May the heaven be favorable to you when you pass by here.

So, let’s still say a few words about the wines. The white grape varieties are Viura, which is largely dominant, Malvasia and Grenache Blanc. But Spanish people do not produce white wines for gastronomy. Four red grape varieties are used in the composition of Rioja: tempanillo, garnacha, mazuelo and graciano. Tempranillo, which does not like drought, is by far the most widespread variety, producing fine wines. Garnacha, that is grenache, the grape variety mostly grown in the world, with harder, more tannic wines. Mazuelo is carignan noir, a variety imported from France, which produces a very tannic wine and little aromatic. Graciano is an indigenous grape from Rioja, representing less than 1% of the region’s vineyards, but it is the one that gives the most aromatic wines. So here for your cellar, if you find them and if you have the money to buy them, the new Parker 2018 notes for the great vintages of the region. Two things to specify here. The great wines of the region do not reach high price ceilings as in France. In 2020, the most expensive are about 350 Euros per bottle, but you can find very nice wines at less than 100 Euros per bottle, and even much less. Secondly, the great guru Parker has stopped operating, but he has formed a team that has the same tastes as the master, namely very full-bodied and powerful wines. So, Artadi El Pisón leads with 98 points. Here, we know the grape variety and the vine. It is tempranillo from a vineyard planted in Laguardia in 1945, 480 meters above sea level, on deep clay-limestone soils, in Rioja Alavasa. But, it’s not just the tempranillo that is celebrated by Parker. The second wine, at 96 points, is the Quiñón de Valmira, a wine of Álvaro Palacios, one of the great masters of wines in Spain. The vines are on Mount Yerga at 615 meters above sea level in Rioja Baja and the grape variety is grenache. The third wine cited, at 95 points, is Pozo Alto, in Rioja Alavasa, from centenary vines planted mostly in graciano. Actually, there are great wines in the three regions of Rioja and it’s not just tempranillo to taste.

It is the year 1044. Dominique García, who will become Santo Dominique de la Calzada, builds here a bridge on Oja River. He also creates a pavement (calzada) to cross these marshlands. You will find that this saint is so famous in the region, that sometimes he is attributed all the way that crosses Rioja and even a part of Castile. So long, some Spaniards even think that he contributed to the writing of the Pilgrim’s Guide! Here, he erects a chapel dedicated to Santa María, a hospital and an “albergue” for pilgrims. Thus, some houses built around the hermitage during his life develop during the XIth century. Throughout the early Middle Ages, the city develops thanks to Santiago track. At this time, Rioja does not exist, and the city depends on Castile. It is precisely the king of Castile, Alfonso VIII who grants at the end of the XIIth century, useful fueros which give many privileges to the city. The city then knows a great rise, which will be accentuated until the end of the XVIth century. Of course, the city was later modified, but it retains a structure quite similar to that of XVIth century.

Today, along the vineyards, but also along the highway, where sometimes drivers make you brights, the course follows pleasant hills. The stage ends in one of the jewels of the Spanish way, the old town of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, named in this way to pay tribute to the local saint.

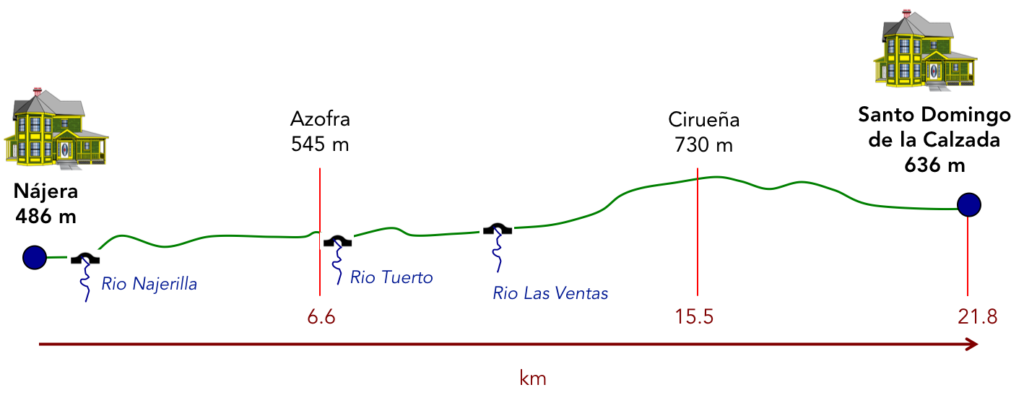

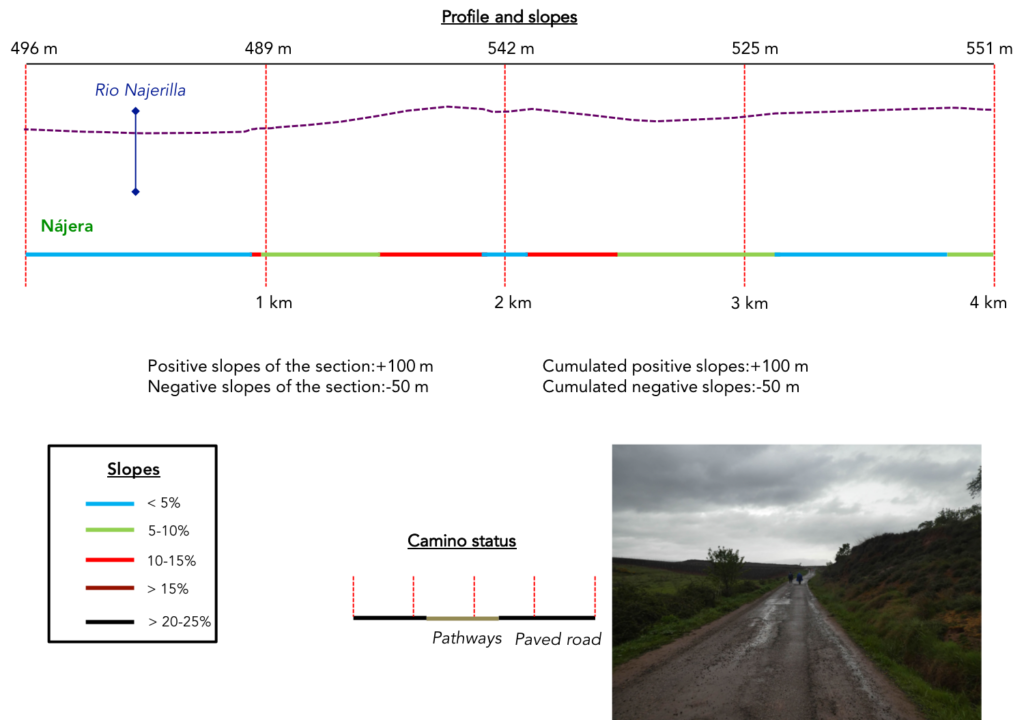

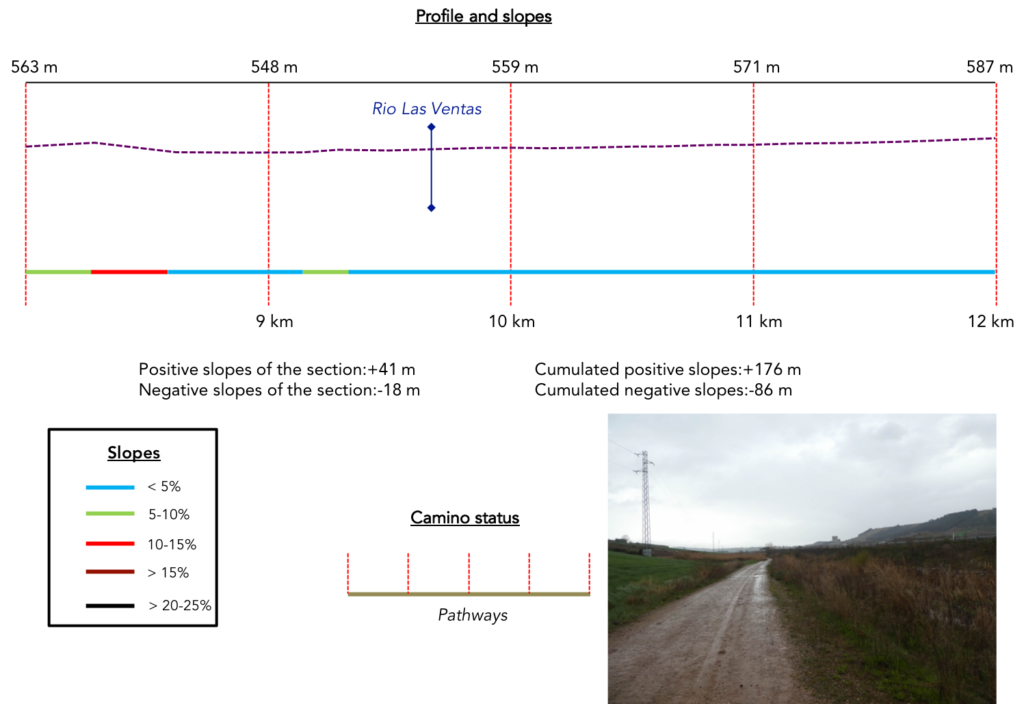

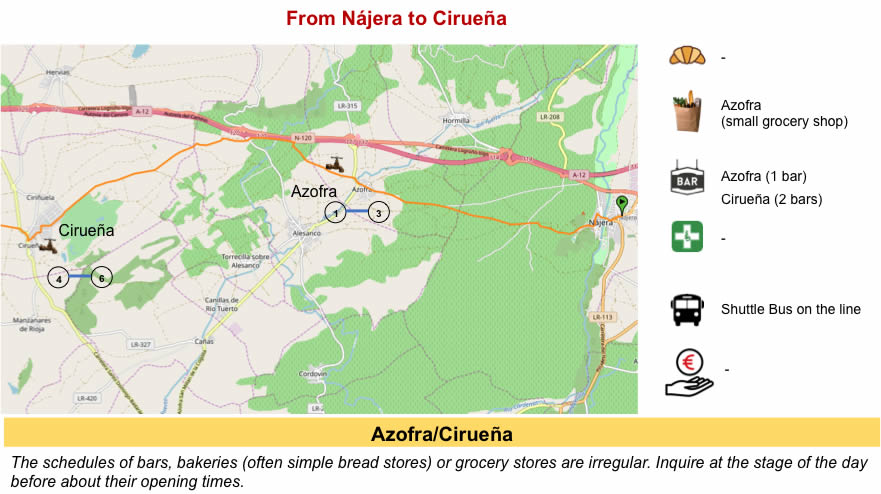

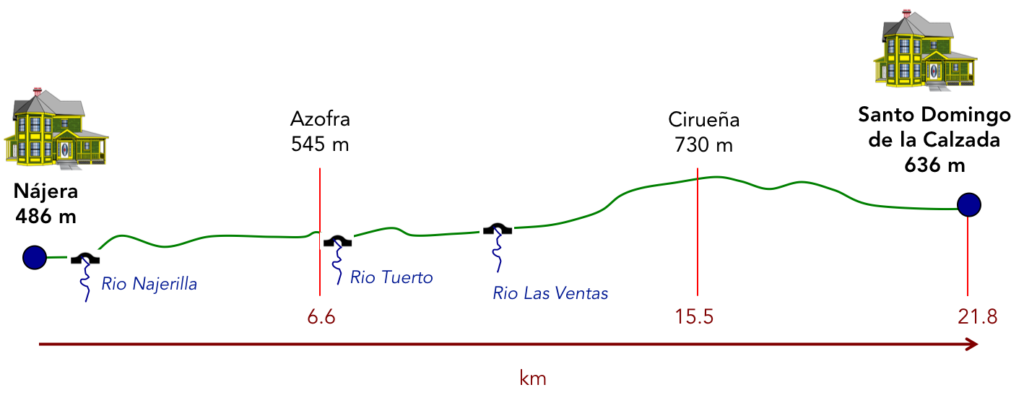

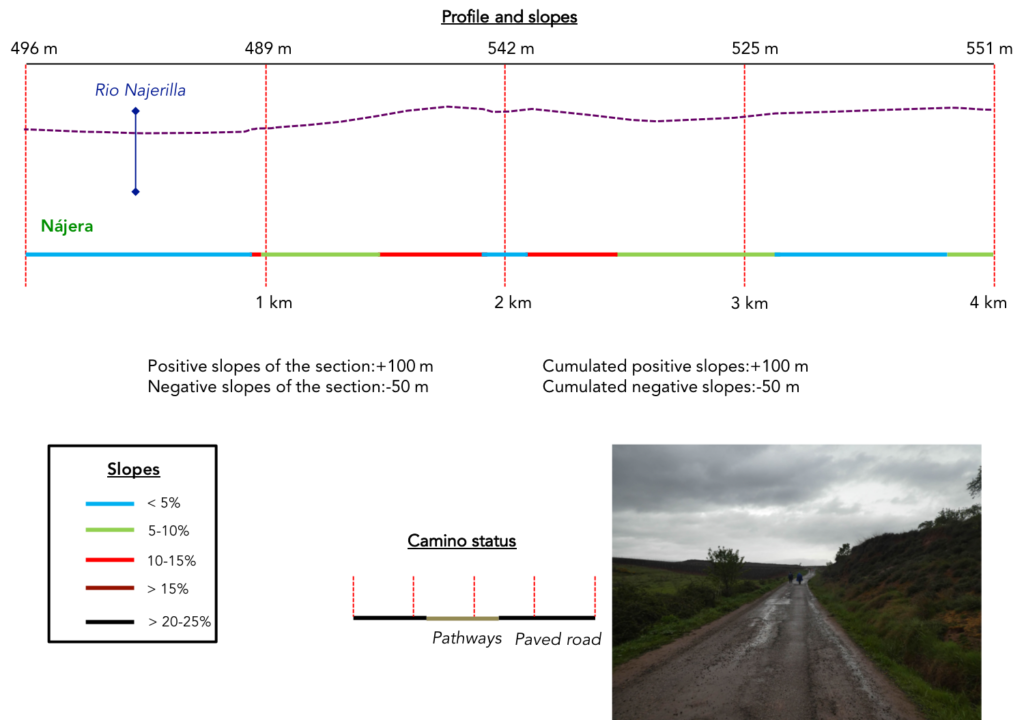

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the day (+343 meters /-217 meters) are not very consistent. There are only two places where the coast is a little more pronounced, first coming out of Nájera, under Mount Malpica, then climbing towards the golf course in Cirueña. For the rest of the course, you’ll go for a little ride.

In this stage, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other paths of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on the pathways:

- Paved roads: 5.0 km

- Dirt roads: 16.8 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

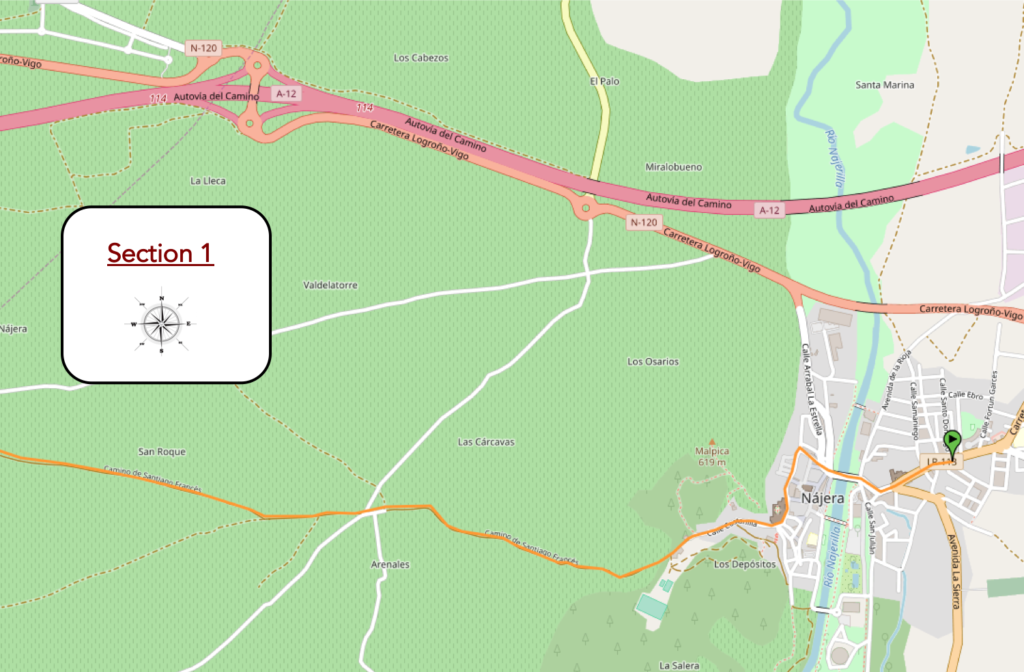

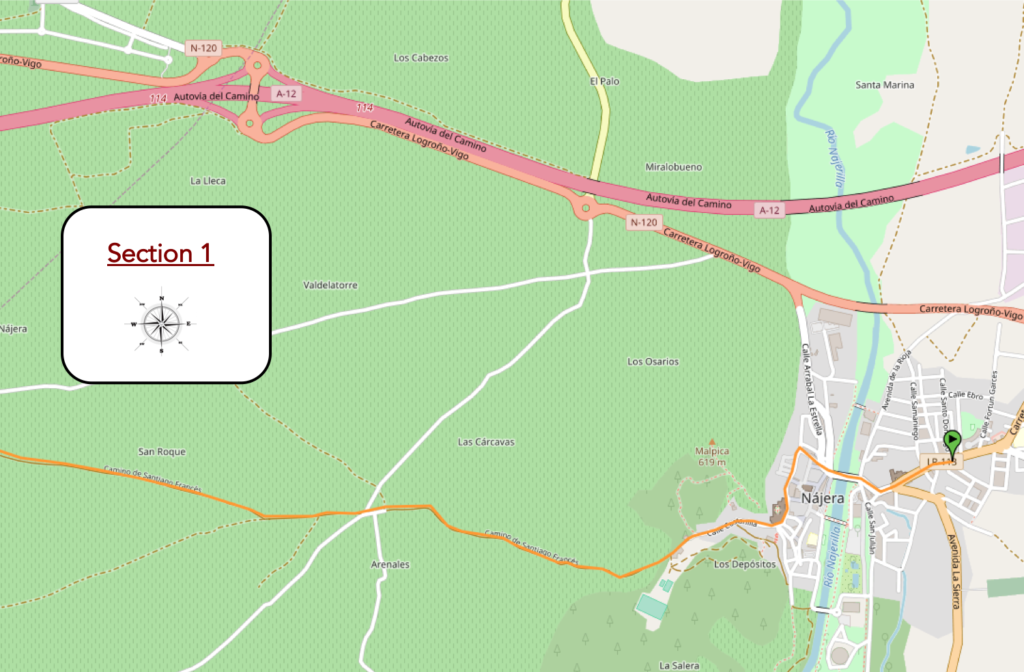

Section 1: On the heights of Nájera.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: you still have to pass the small hill of Malpica above the city.

| Today, it is still pouring rain in La Rioja and the weather forecast is pessimistic for most of the week. It will still be rotten weather, greyness, wind, rain, and cold, but we say “bad weather does not stop the pilgrim”, right? Whether you spent the night in the new town or the old town, you will have to find the monastery of Santa Maria Real. As the stages are often short, you will have had plenty of time to crisscross the city several times and you will find it easily, because the indications in the city are quite complex and chaotic. |

|

|

| This morning, it is almost dark in broad daylight. The Camino therefore leaves Nájera behind the monastery and climbs. Without saying anything, you may listen to the rain pattering on the slippery cobblestones above the city. |

|

|

| You are under the Malpica mountain and soon a pathway, which replaces the road, slopes up into the pine forest. |

|

|

| The wide dirt road climbs steeply through a magnificent pine forest where heather runs through the red clay. A car passes splashing mud. Our two pilgrims, whom we see every day since the start, with their travel cart, struggle a little on the road. Let’s say that on the first 10 days of the trip, we often meet the same pilgrims on the road. It is only afterwards that all this flow of pilgrims is diluted and that we no longer always find the same faces and the same uniforms. |

|

|

No, it is not a Dominican sister who got lost on the way. Our pilgrim wears a uniform that sacrifices the desire to please, which makes her as anonymous as it is mysterious, but which undoubtedly allows her to find her style, for a little more comfort. And it is necessary, under the rain which pours in torrents.

| At the top of the hill, all this nice little world threads its way between the red shales. Korean pilgrims are always so polite. They still give “Buen camino”, when you cross them. But we have a feeling that it will not last until Santiago and that some are already beginning to abandon the use. The Americans do not care and continue to gesticulate and speak loudly. They will continue like this until the end of the road. They came for this. Shortly after, the Camino forks on another road, in a day almost as dark as the night. |

|

|

| Here, an active or abandoned farm, who knows? there is no life around. To see a farm in the landscape is as rare as finding a four-leaf clover in the area. The Spaniards will never live outside the villages. They must fear loneliness, because their way of life is to stroll in groups in the evenings in villages and towns. Not even sure that they watch American series on TV in the evening. |

|

|

| Under the dense and cold rain, the pilgrims save themselves, curl up under their dripping diving suits to pass the top of the ramp. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino runs on a very bad tarmac road between the vines and the fields of cereals, which are rarer. For the first time, curious concrete irrigation canals appear. |

|

|

| Further on, the road reaches a kind of plain and you may hear the powerful blowing of gusts of wind and the murmur of rain. |

|

|

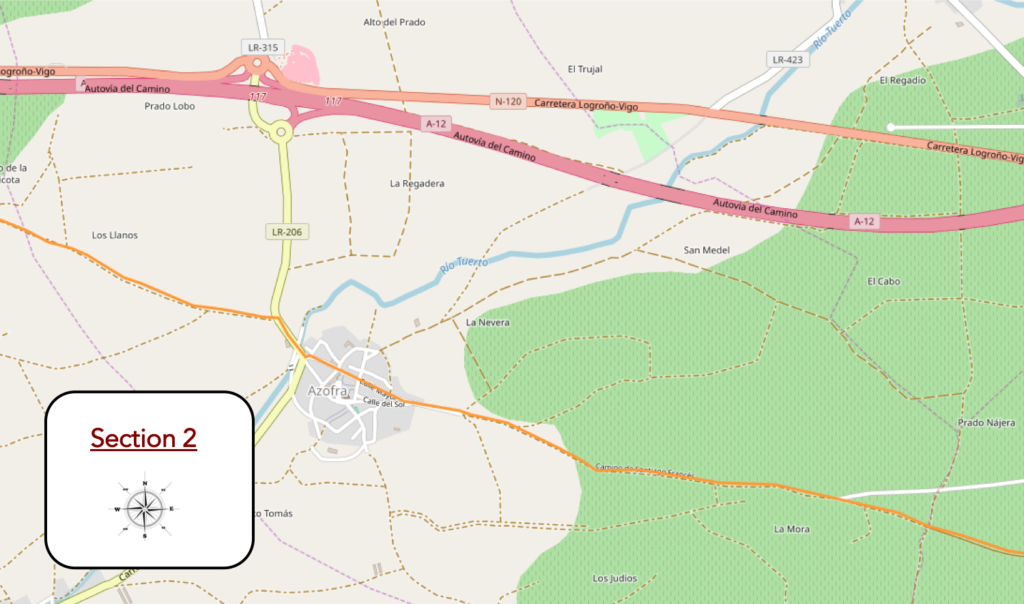

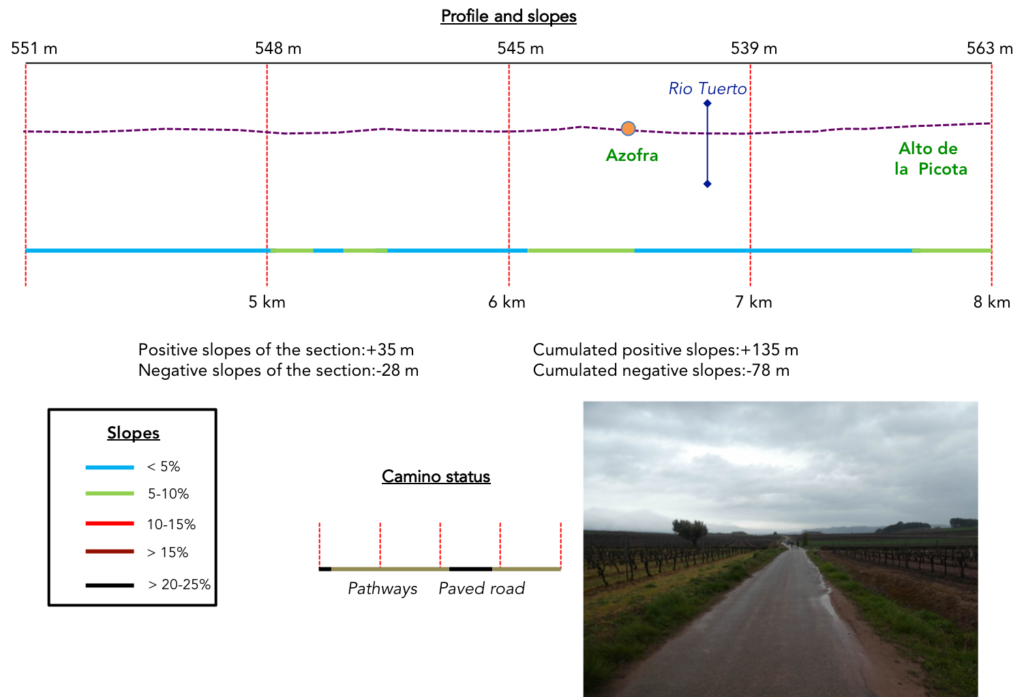

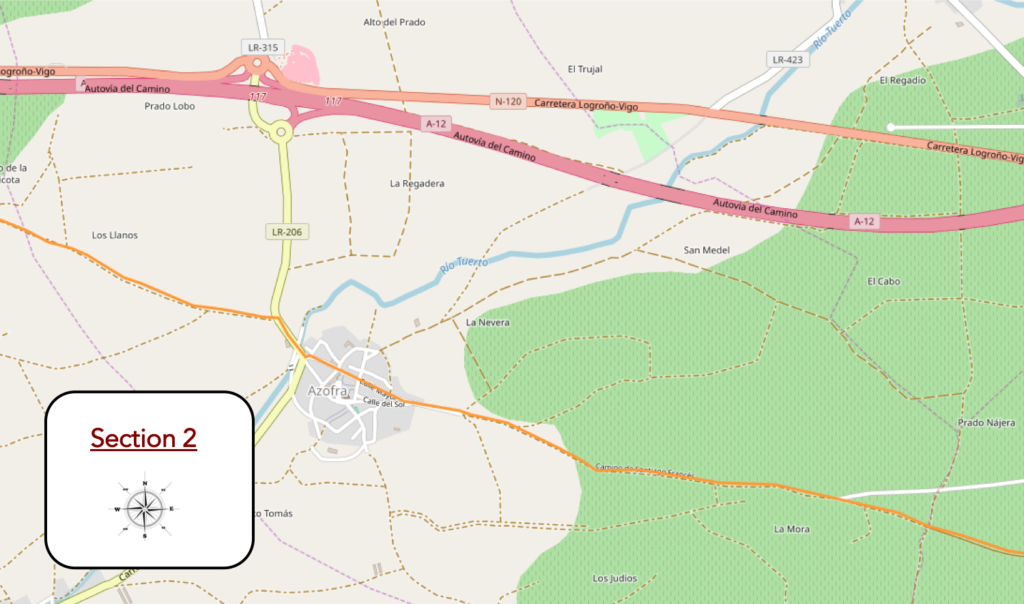

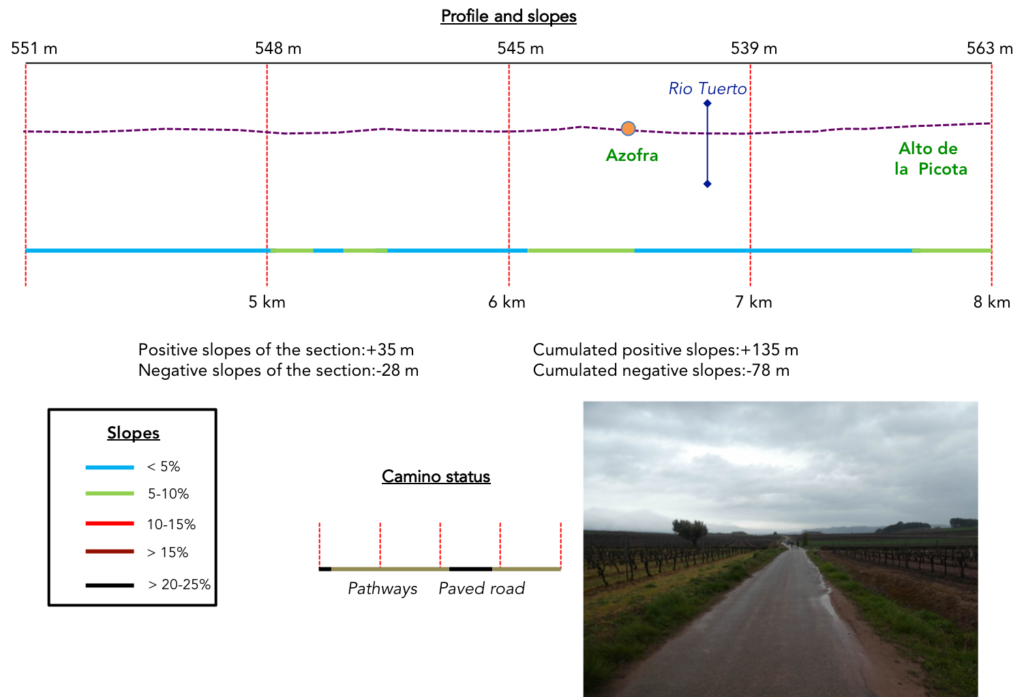

Section 2: In the vineyards of Rioja.

AGeneral overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Further on, the route alternates between the road and the soggy dirt along the vines. |

|

|

In Franco’s time, Spain made a great effort to irrigate the country. There are many concrete canals that collect rainwater, but no doubt also water from the many small invisible streams. These canals always end in small water towers, connected to each other, from which water is drawn. With what is falling these days, there should be no scarcity.

| Further on, you’ll leave the damp ground for a small vineyard road. There is not a single worker in the vineyards, nor more than a peasant in the fields. The vines were pruned and the wheat planted in autumn. And in this impossible spring, what would they do there? |

|

|

| The road is peopled with this huge procession of pilgrims, who parade with tight lips. This is not a day for wishy-washy chatter. |

|

|

| Further afield, the road has become almost straight, along the irrigation canals, leading to the outskirts of Azofra. |

|

|

| Azofra is a small village, all shutters closed, in which no doubt the winegrowers make up the numbers. The name of Azofra would come from the Arabic as-suxrta, which means homage or from the Hebrew zophar which means beautiful. Anyway, the village is of Arab origin. A pilgrims’ hospital was founded there in the XIIth century, which disappeared in the XIXth century. |

|

|

| The houses are very colorful, combining ocher and pink, but you can guess that the constructions are light and that they probably do not all have heating in this country that is difficult to live in in winter and spring. These are no longer the stone, opulent mansions of Navarre. Farmers and winegrowers must not run on gold here. By the way, we saw some prices posted in the region: around 2,500 Euros per hectare for a vine in full bearing. Of course, the plots of the great Riojas are more expensive. Do you want a comparison to define the purchasing power of people here? In Bordeaux, the vines of the small appellations sell for between 6,000 Euros and 25,000 Euros per hectare. Forget the grand crus. If you want one hectare, you will have to pay more than 2 million per hectare, and some vines are not for sale! |

|

|

| On leaving the village, the Camino crosses the Rio Tuerto stream and continues for a very short time on tarmac. |

|

|

| Then, it’s the return of the dirt, let’s say rather today filthy mud where shoes stick, then come off. Pilgrims plod through the sodden ground, the sneaky, icy mud spattering their trouser bottoms. So, the pilgrims, when you meet them, exchange remarks, laugh. None of them are crying or grumbling. Against whom anyway? Nobody made them come and get stuck here. May you spend a day here in good weather, perhaps, but without the heat wave. |

|

|

| So, the pilgrims, like toads on the run, move forward, splashing through the ocher mud of this magnificent country, perhaps even more beautiful in the rain. Some make improbable slaloms to find here and there a saving blade of grass. But it is often in vain. So, they wade like the others, seeing the A12 motorway pass by in the distance, which has become silent, the violent wind suppressing any potential noise from the engines. |

|

|

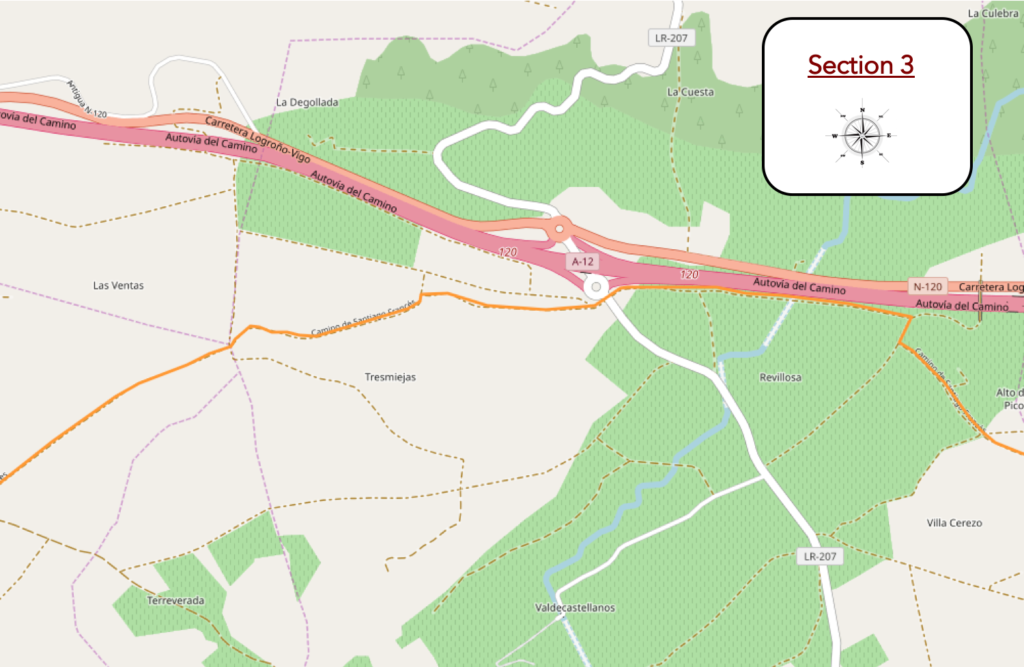

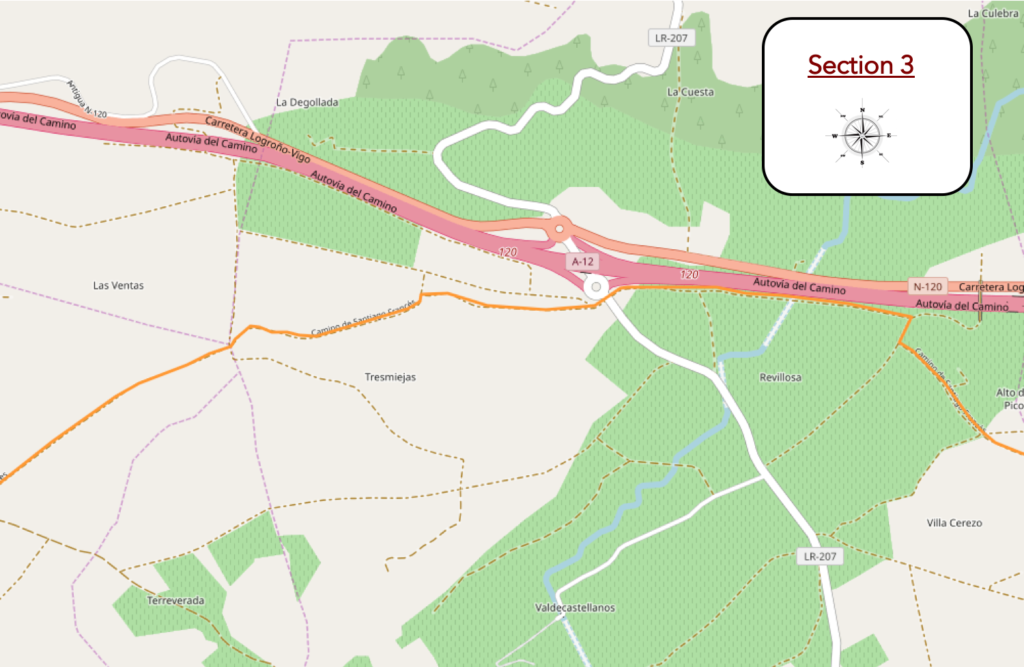

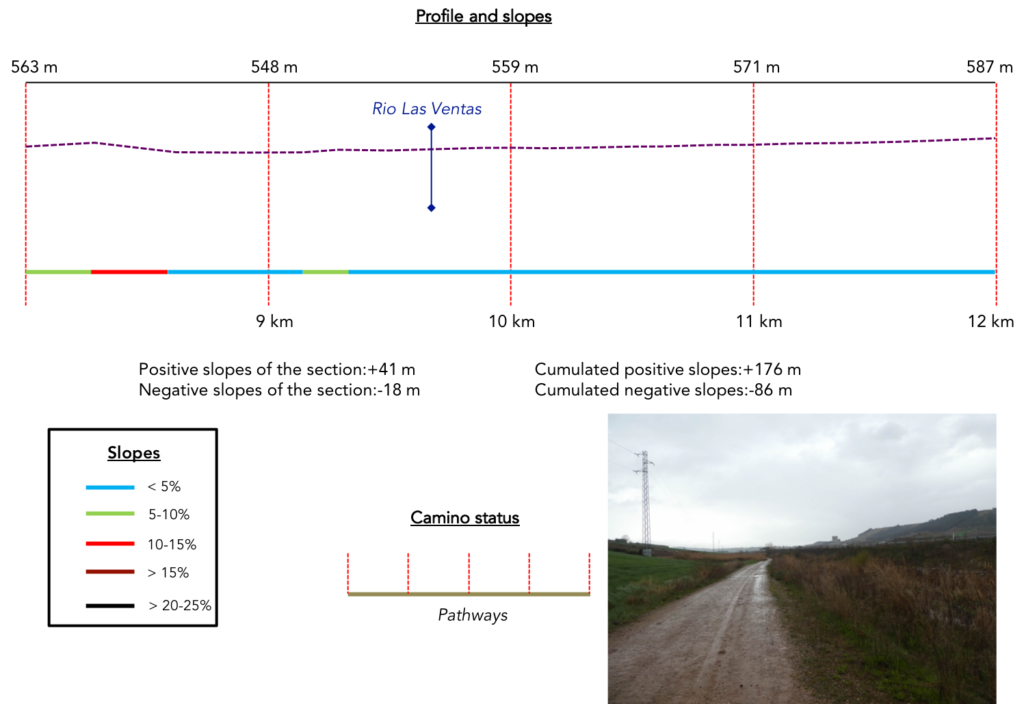

Section 3: Today in the mud of Rioja.

General overview of the difficulties of the routes: course without any difficulty.

The legs are already heavy, weigh tons. Your ears hear the lapping of shoes taking on water of any quality and sucking you into the thick, deep, sticky mud. Each bad step requires a sustained effort to get out of it. You didn’t come here to get bogged down before seeing Santiago, did you? It would only miss the passage of tractors here, so that the happiness is total, right?

| The pathway then approaches the highway. It is almost dark on the sodden track. The viscous mud that chokes you has now become more slippery, but the foot still slips. However, the rain seems to be calming down. Prayers to the good saint seem to bear fruit. |

|

|

| A stream runs through here, the La Ventas stream, which lives up to its name with the west wind blowing in your face. Take a good look at these landscapes. When you pass here in the summer on the highway, there will be nothing but Pilgrim zombies crawling through the desert, dry to the bone. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway heads to a roundabout, where the highway and the N-120 pass, which runs parallel to the highway. The Camino crosses the Ventas stream, near a small regional road. |

|

|

| And the show continues, haunting some would say, extraordinary and out of the ordinary, even exceptional, others would say. In sticky mud, or sometimes in puddles. It’s like art, it’s all about perspective. |

|

|

| Soon, the vines tend to disappear in favor of cereals. The wheat hasn’t come up yet, and it’s mid-May. Many fields are still covered with green manures, those plants that are grown to enrich the soil before planting crops. |

|

|

| When you scan the horizon, you see far ahead a pathway that climbs the hill. No doubt yours! |

|

|

There is in these landscapes something like the magic of solitude, without falling into the anguish of isolation, the image of a fluid space where man loses himself in his reverie, where his gaze embraces the sky above. above the hills. And it’s even more beautiful when the light plays with the rain and the clouds, in a unique green striped with ocher.

| Since the start of the stage, you have already been walking in the classic landscapes of the Meseta du Nord, this high plateau that crosses almost all of Spain in the north of the country. Besides, the pilgrims have already understood. They read the guides before coming here. For them, in their reading, The Meseta was just a three-syllable word, very little to hold their attention, to kind of pique their interest. But now the dice are rolled. It will have to be done. There are more than ten days. So, it will be a question of putting one step in front of the other, without cursing the sky. Today, some are even jumping for joy, and for good reason. The wind has driven away the black clouds, has stopped and the rain has stopped, even if the shoes are still lapping in the residual puddles. |

|

|

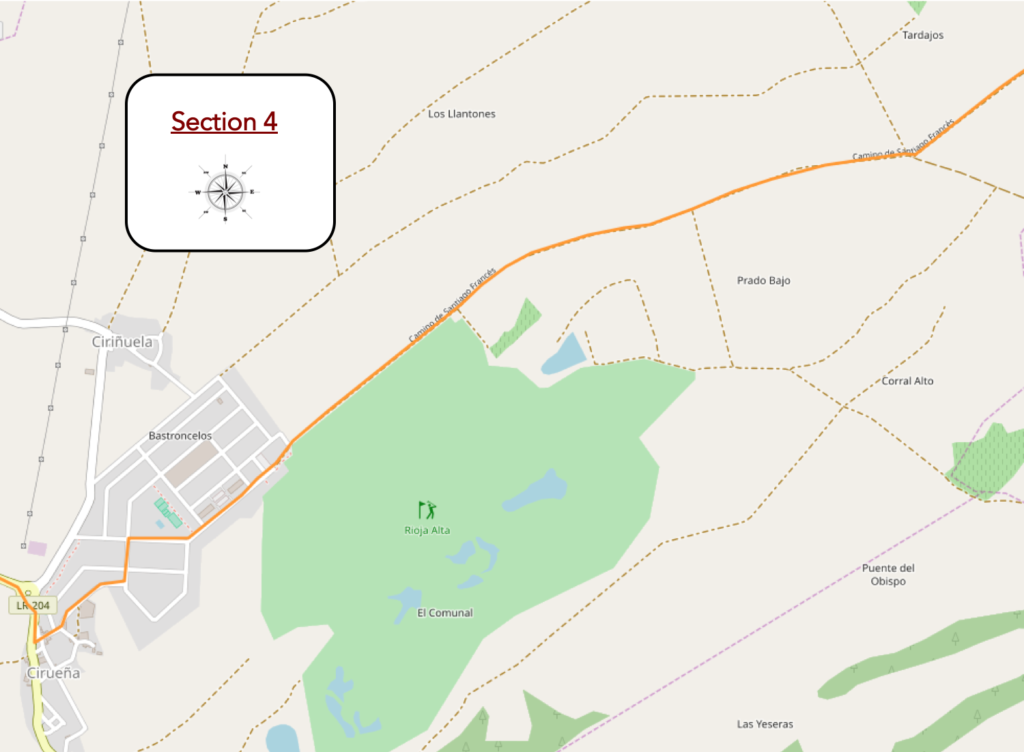

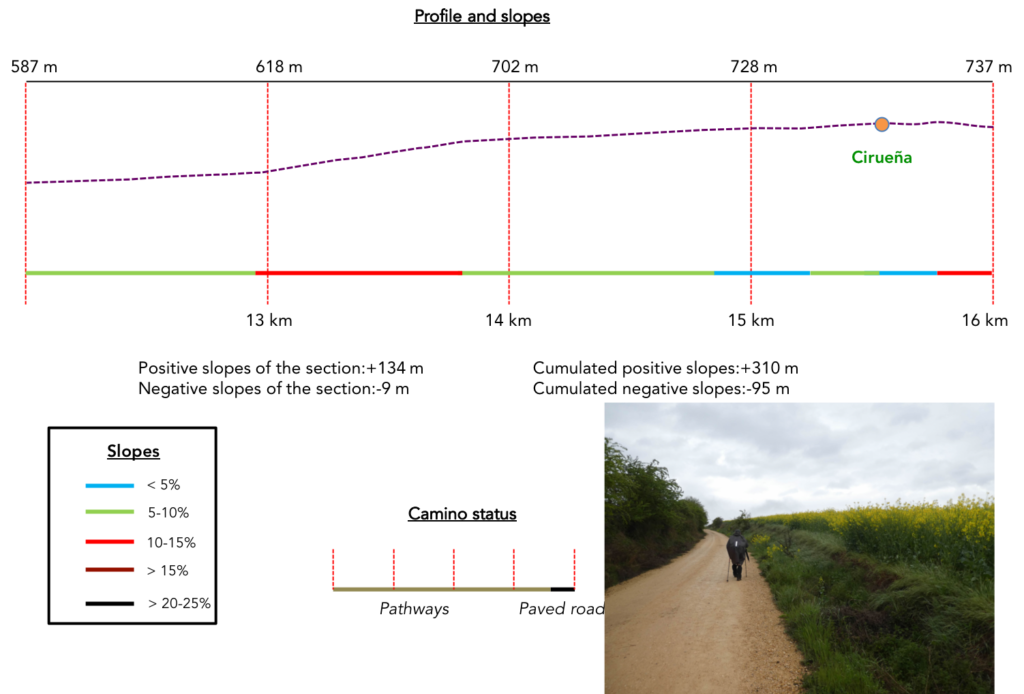

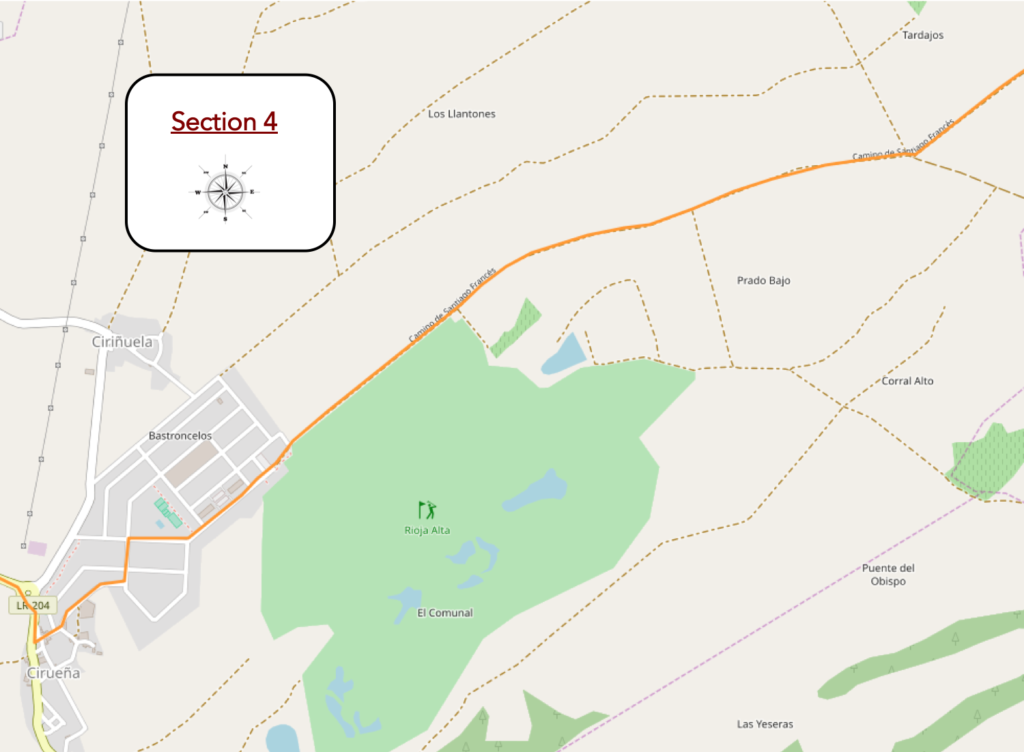

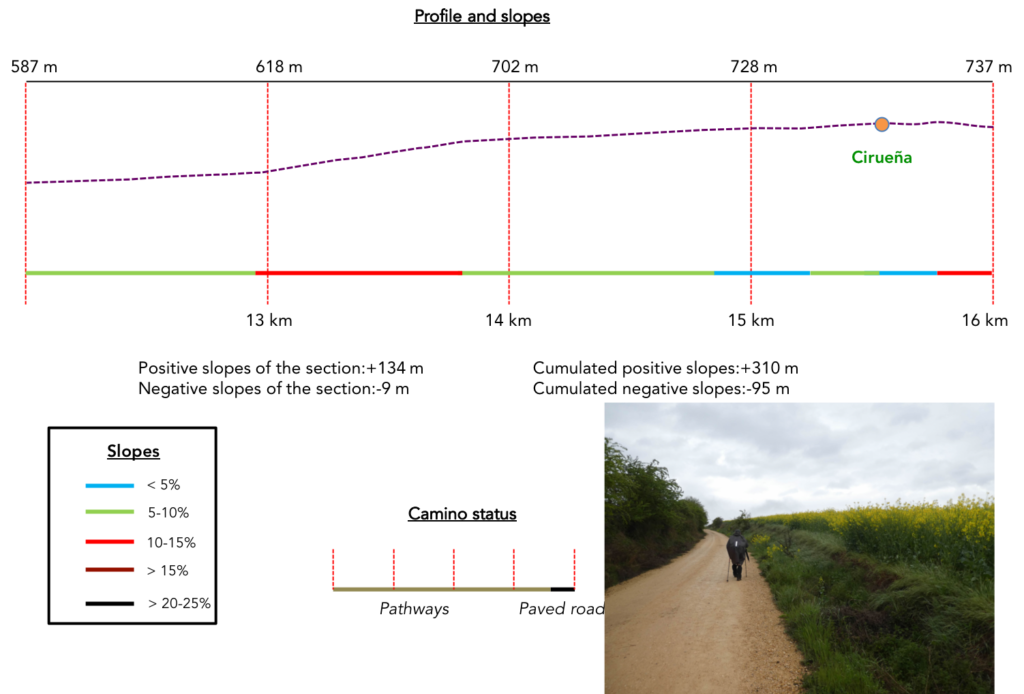

Section 4: A little round of golf, ladies and gentlemen.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: the second effort of the day, in the form of a climb of almost a kilometer with a fairly steep gradient, but never really exceeding 15%.

| The pathway then slopes up gently towards the hill. Here, a cyclist makes the Way. They are today more than 5% of the pilgrims. Most of them travel with the minimum. In Spain, many organizations manage the transport of luggage, whether for cyclists or walkers. Dirty as they are today, they will have work to clean themselves and their work tool. |

|

|

| Here again, the fields of cereals clearly dominate the vines. Some pilgrims have not removed a gram of their protection against the rain. It might come back, who knows? |

|

|

| Further up, the slope becomes steeper on the wide ocher pathway, which has dried up considerably. |

|

|

It’s beautiful again here. The light plays with the ground, cuts out the fields, instilling an impression of movement while delightfully modulating the color variations.

| Gradually, the pathway comes to the top of the hill. It’s not warm enough to picnic but pilgrims have time to put away some of our rain gear. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway runs along the Rioja Alta golf course, close to the village of Cirueña. |

|

|

| Here the symbolism of the Camino de Santiago accompanies golfers. |

|

|

| Today there are no crowds on the greens. Promoters have seen big and sometimes even luxury here. Everything smells artificial. |

|

|

| It must be difficult to occupy all these small apartments. |

|

|

| The Camino soon leaves the golf developments and heads into the village proper, a stone’s throw away. |

|

|

| The village is much less luxurious. References to Cirueña date back to the Xth century, when the King of Navarre won a fierce battle there against the Castilians. The current Iglesia San Andrés is a recent construction, on the base of a pre-Romanesque church dating from the Xth century, which adjoined a monastery. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino arrives at a roundabout. Here golfers will know, if they do not already know, that the Camino de Compostela passes. They can then sometimes abandon their golf clubs for a little while. When you are told that Compostela in Spain is not just a pilgrimage, but also a lot of business, too much pretense. |

|

|

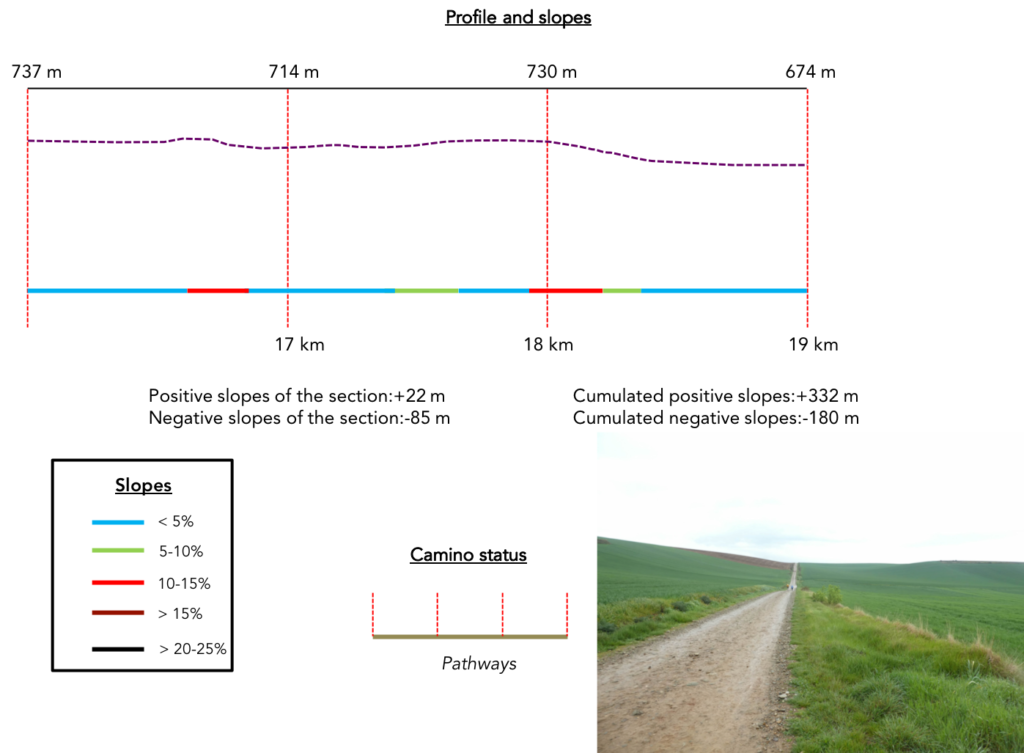

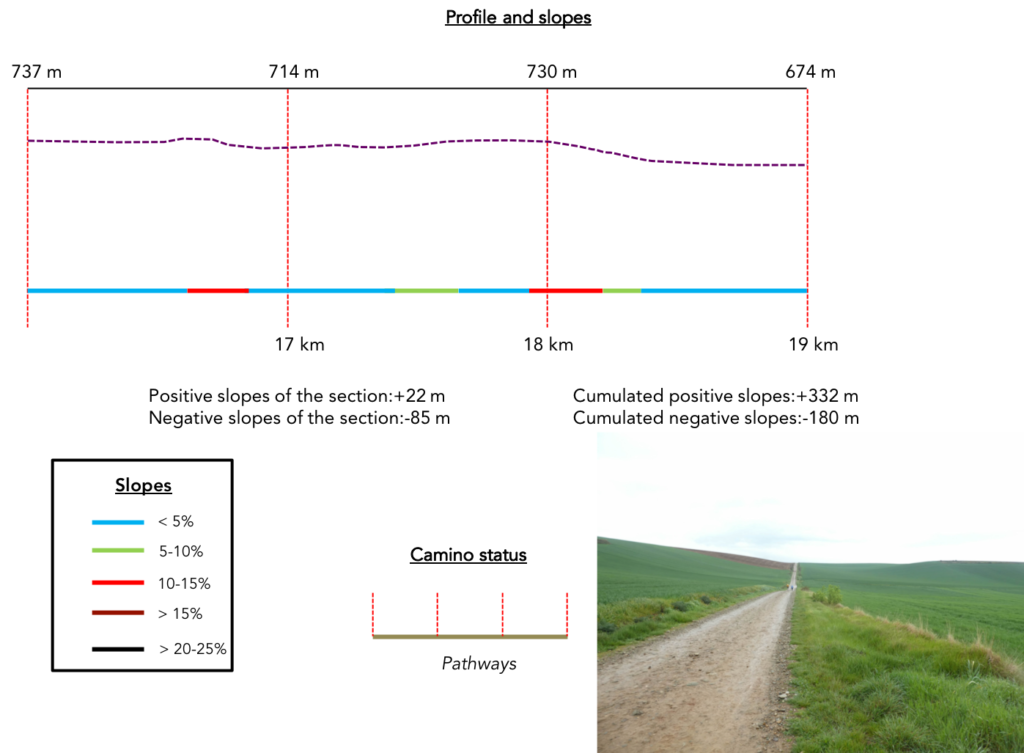

Section 5: Some light bumps in the Meseta cereals.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, with sometimes more marked undulations.

| It is then back to business as usual, in the cereal fields, today on the sodden ground, with sometimes a few brambles on the small embankments. Here, the vines have disappeared. |

|

|

| Almost not a tree. Since the beginning of the day you have only crossed a few rare almond trees and discreet black poplars. Still, there was probably a time when there were trees here. But this was to prevent the passage of tractors. So, people shaved it all off. One day, with global warming and the total loss of biodiversity with this way of doing things, the Meseta may be a real desert. It is high time to bring back the hedges to avoid disaster and eliminate this intensive, unbearable culture. |

|

|

| But that would deprive you of the visual vertigo offered by these fields which extend without being able to limit their end. |

|

|

Here space is silence and solitude. It’s so big that far ahead of you, the pilgrims are sometimes little bigger than ants.

| Much further, the pathway gets at the top of the gentle hill. |

|

|

Here, it’s like an open window on time and space, like a great strolling wander.

| Further on, the spectacle opens on Santo Domingo de la Calzada, which you’ll see appearing on the horizon. From time to time you will see peasants who no doubt come to measure the progress of their crops. But nothing really grows in this rotten spring. |

|

|

| The pathway then begins to slope down. The descent is quite steep at the start, but the slope reduces quickly. Here a few holm oaks must have been lost or forgotten. From a distance, the city looks a bit like a large industrial village lost in the vastness of the plain. |

|

|

| It is then a long straight pathway in the plain in the middle of wheat, rapeseed and probably corn waiting. Don’t think the town is right next door. |

|

|

| The approach to San Domingo de la Calzada is endless, on the gigantic plain. Some pilgrims wonder what they came to do in this country. There are so many beautiful tracks before you get here, they say. |

|

|

| Yet the borough is getting closer, isn’t it? You can clearly see the bell tower of the church. And it stopped raining a long time ago. |

|

|

| To say that you are approaching an exceptional place, the arrival is not royal. First of all, it’s flat as the hand, there are no hills here. And then, all the suburbs of the world compete in bad taste. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the Camino enters a part of the borough outside the walls which offers no interest… |

|

|

| …before entering the old town. Santo Domingo de la Calzada has dedicated its life to improving the routes of pilgrims, being the basis for the construction of many of the roads and bridges that you cross, although many have been rebuilt since the XIth century. He was born Domingo García in 1019 in the village of Viloria, through which you will pass tomorrow. Diverted in his efforts to become a Benedictine monk, he became a hermit in the forests, where he lived alone and cared for pilgrims, until the bishop ordained a priest. In 1044, he founded a small village around his hermitage which later became the city that bears his name today. Dominic and his disciple Juan de Ortega began to build a church. After his death, the village had grown, and his church was elevated to the rank of cathedral. He was buried in the cathedral. |

|

|

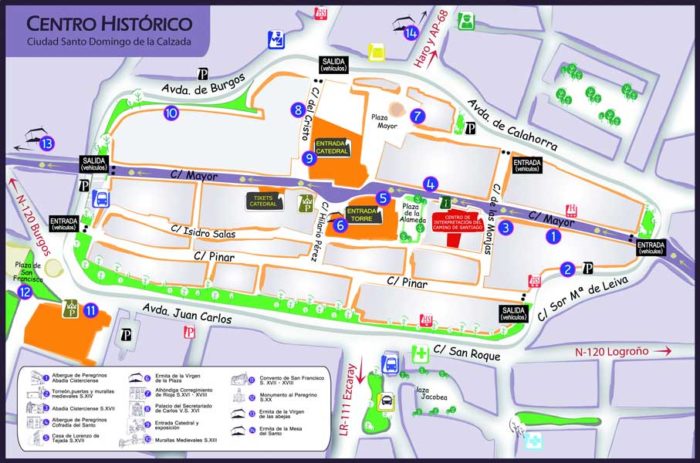

Section 6 : Visit of the old town.

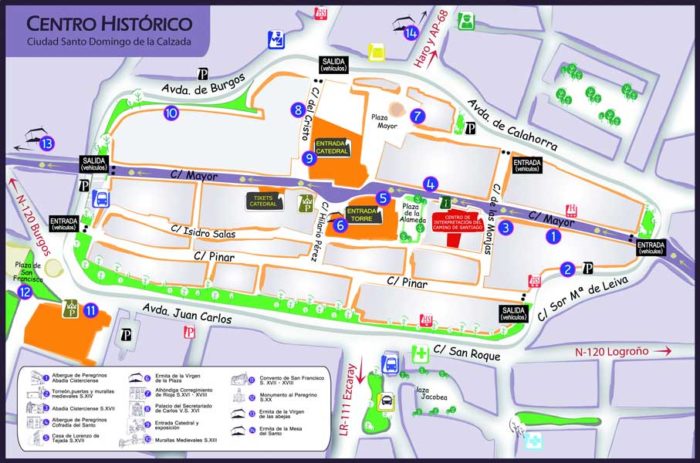

The map of the city (6,000 inhabitants) is simple. Almost everything happens in Calle Mayor which crosses the city from one side to the other.

https://www.elbalcondemateo.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Mapa-Centro-Historico-Santo-Dominog-de-la-Calzada.jpg

| The cathedral of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, whose baroque bell tower stands out from the church, was seen from afar, for miles around from the top of the hill. The cathedral is the treasure of the city, one of the great and beautiful churches in Spain. Here, the work of the Romanesque church began at the end of the XIIth century, on the basis of the primitive church of Santo Domingo. The cathedral had three towers during its history. The primitive, Romanesque style, was destroyed by lightning in the XVth century. A second Gothic tower fell into ruins. The current tower is baroque, raised in the XVIIIth century, 70 meters high, built outside the church for reasons of weak ground. It has eight bells and a clock. |

|

|

| The south portal, the portal of the saint, which dates from the XVIIth century, is decorated with niches, in which appears Santo Domingo de la Calzada flanked by the holy martyrs Emeterio and Celedonio. Many visitors, and there are a lot of them here, will prefer the western portal, hesitating between Romanesque and Gothic, from the end of the XIIIth century, completely bare. |

|

|

| The church was modified several times between the XIIIth and XIVh centuries. From then on, the interior of the church wanders from the most Romanesque style, but not very present, in the chevet, in the apse, with a beautiful ambulatory and chapels, to the most charged Baroque of the altarpiece, with beautiful Gothic naves and beautiful capitals. The church is quite bright, which is better for the visit. |

|

|

| The sepulcher of the saint is present in a small chapel. It is dated to the XIIth century. A whole mythology has been built here with the miracles performed by the saint. During the construction of the bridge, the legend of the wheel was born. A pilgrim who slept at the entrance to the bridge was reportedly run over by a cart driven by bulls. The saint would have brought him back to life. Another miracle would be that of the sickle, with which he managed to cut down an entire beech forest. There is sometimes confusion between the miracles of Santo Domingo and those of St Jacques recounted in the Codex Calixtinus. |

|

|

| The attraction of the cathedral is the Gothic henhouse, subject of interrogation for the pilgrims who do not know the history. This XVth century Gothic work, located near the sepulcher of the saint, houses a white hen and rooster. The birds are replaced each month by volunteers from the brotherhood of Santo Domingo. Archives from the end of the XIVth century attest to the presence of these gallinaceans. The pope granted indulgences to the faithful who prayed here to the saint, or who better made the rooster sing (“miransen al gallo ya la gallina que hay en la iglesia”) (where a hen crowed after being cooked).

There are two versions of this story, one French, another Spanish. But, in both versions, there is a German pilgrim from the XIth century. In the Spanish version, the young pilgrim spent the night at the inn, with his parents. He refused the advances of a servant. Annoyed, the latter hid a silver dish in her luggage. At the time of departure, she accused the pilgrim of theft, who was hanged for an offense he had not committed. His parents continued the journey to Santiago while praying to the saint. On the way back, they heard their son say from the top of the gallows that he lived, thanks to the protection of the saint. They addressed the judge, seated at the table, tasting a roast rooster and hen. The judge answered them ironically: “If your son is alive, this hen and this rooster will start crowing on my plate”. As in all good stories or miracles, the story has a moral ending. The rooster began to crow and the hen cackled. The judge made the young man hang and hanged the maidservant in his place.

The miracle of the “hanged-hung” is the seventh miracle of the second book of the Codex Calixtinus. |

|

|

| Below the tomb of the saint, a false crypt was erected in 1958 to house the relics of the saint. A large slab of marble sheltering the relics and an ambulatory were placed there to turn around, according to the canonical rules. Marko Roupnik, a Slovenian Jesuit priest, great creator of mosaics, holder of the ecumenical art of religious art in Rome, was later entrusted with the task of creating frescoes illustrating the life and history of Santo Domingo. This crypt and the mosaics are remarkable. |

|

|

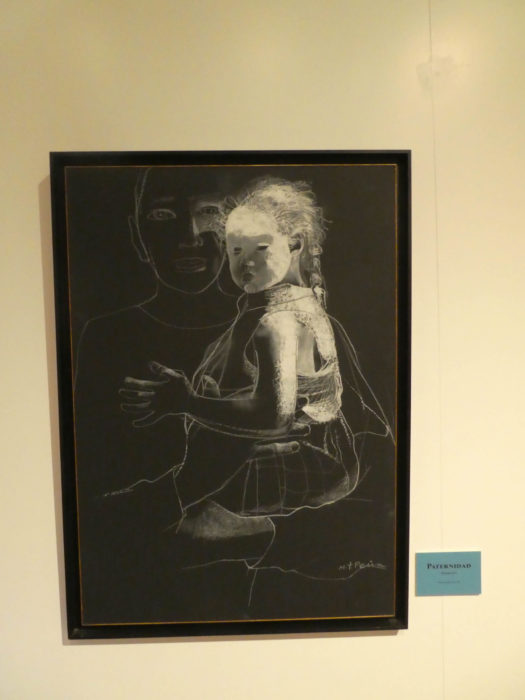

| Adjoining the church, in the direction of the cloister, is the museum of religious art of the Cathedral. There are pieces of goldsmithery, Hispano-Flemish paintings, but also quite modern paintings of beautiful craftsmanship. It must be said that today’s museums, also in Spain, have made great progress in the arrangement of the works presented. |

|

|

| The visit to the cathedral ends with a visit to the cloister. The cloister dates from the XIVth century, but it was deeply modified in the XVIth century. Here there is still a stripped-down Cistercian monastic atmosphere on the tight cobblestones of the square |

|

|

| The Cistercian monastery “Our Lady of the Annunciation” is a stone’s throw from the cathedral. Again, it’s a long story. Before arriving here, the nuns officiated in another convent, far from here. The place being inhospitable, so they requested the transfer to Santo Domingo de la Calzada, a transfer which was granted to them at the beginning of the XVIIth century. Arrived here, they lived for a few years, the time of the construction of their church, in a house close to the chapel of Notre Dame de la Place. The monastery church has the shape of a Latin cross and its interior, full of bishops’ tombs, is very Baroque. The sisters are still there, and run a hostel for pilgrims close by. A real institution, with rooms hardly larger than cells, collective meals and prayers, where Spanish pilgrims flock. Among the Cistercians, life is like this. Some pray, others shop. |

|

|

| Near the cathedral, Calle Mayor is a real open-air museum of old patrician residences, almost all emblazoned, some transformed into “albergue” for pilgrims. Note that of the brotherhood of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, whose name dates back to the XIIth century. Enter it to see the monument that is the guestbook, a real tower of Babel. Of course, these buildings have undoubtedly undergone alterations over the centuries, but some walls date back very far in time, to the XVth-XVIth century. Moreover, the city seems to be a highly touristic place. It’s black with Spanish tourists, for the most part. They are so charmed by the city that they even forget the early afternoon siesta. |

|

|

| When we passed, there was a market in the Plaza de la Alameda, a stone’s throw from the Plaza del Santo in front of the cathedral. Yes, there were plenty of local handicrafts, but there was even a wheel of Gruyères, which you’ll be hard pressed to find in Switzerland. |

|

|

| More depopulated was the Plaza Mayor, also known as Plaza de España, just behind the cathedral. This large paved square, surrounded by arcades, seems to house a permanent market, but it was the midday break and the vast majority of the stalls were closed. In the Middle Ages, it was a market place, outside the walls, then it became an arena for bullfighters. It now houses many administrative buildings, those that have not been moved to the place where everyone meets, the Plaza del Santo, a very small space in front of the cathedral and the parador de Santo Domingo. |

|

|

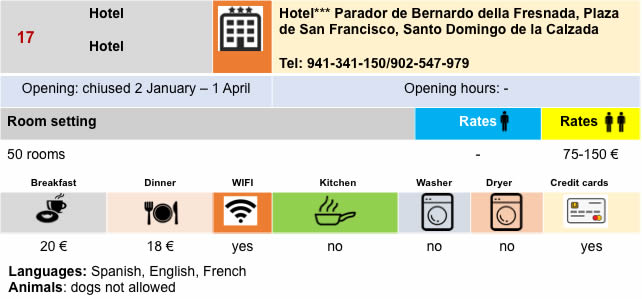

| You cannot leave the Plaza del Santo without pointing out the presence of a magnificent parador. The Paradores de Turismo de España are luxury hotels promoted since 1928 by King Alfonso XIII to encourage Spanish tourism. These establishments are located in castles, fortresses, convents, monasteries or other historic buildings. The Portuguese equivalent is the Pousadas de Portugal category founded in 1942. Even if Mariano Rajoy tried to privatize some hotels, today these, around a hundred, still remain state property. The Parador de Santo Domingo de la Calzada is the old hospital dating back to Santo Domingo itself, transformed of course. Some pilgrims, when they have slept for more than a week in small or medium category “albergue”, like to treat themselves sometimes. The paradores, even if they are luxury, here a 4 star, charge very affordable prices. |

|

|

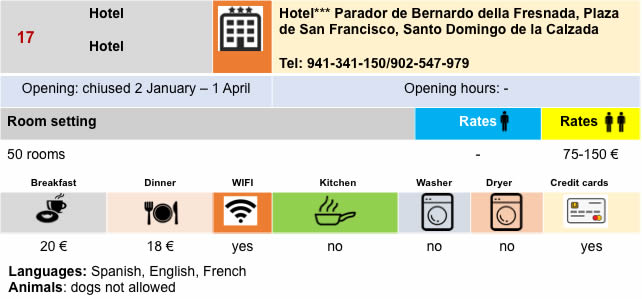

| Now, if you go to the end of Calle Major, where you will be leaving tomorrow, you will find another parador, the Parador de Santo Domingo Bernardo de Fresneda. It is still surprising to find two paradores in such a small town. This tells you the rich heritage of this place. The parador is part of the former Franciscan convent. The Convent of San Francisco was built at the beginning of the XVIIth century. The church is closed for worship. When we went, the church was closed. The decorations for the processions of Holy Week were prepared there. Currently part of the convent is a residence for the elderly, called Hospital of the Saint. It goes in and out, all day. It is still a privilege to grow old in such a setting. Another part of the convent is an art restoration workshop. |

|

|

| The parador here is just one category above the previous one. It is a three star, but it has perhaps even more charm. Eating in a cloister remains quite intriguing. |

|

|

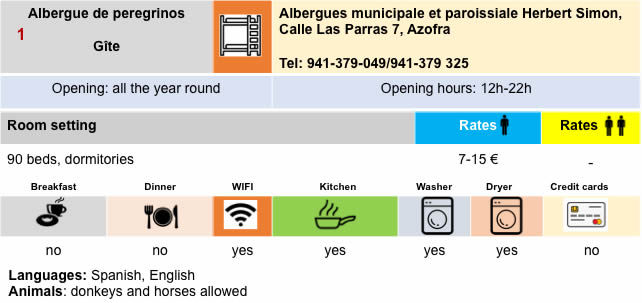

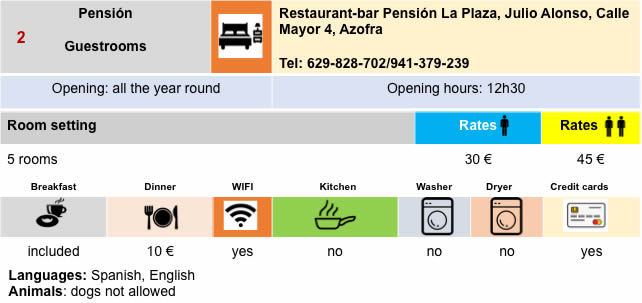

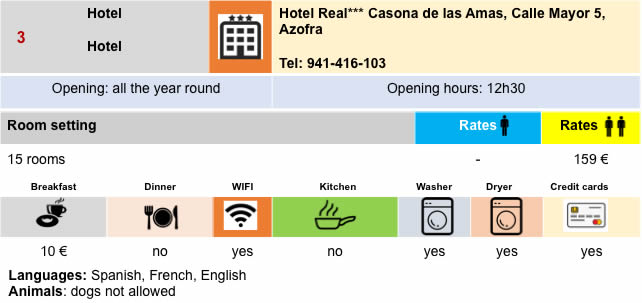

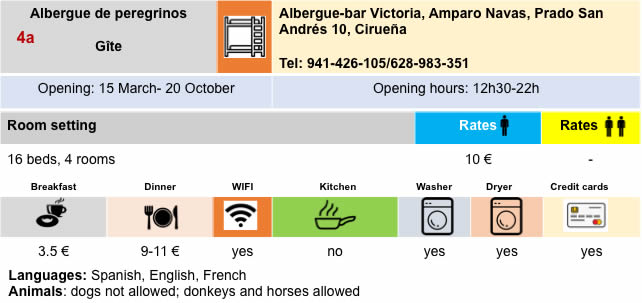

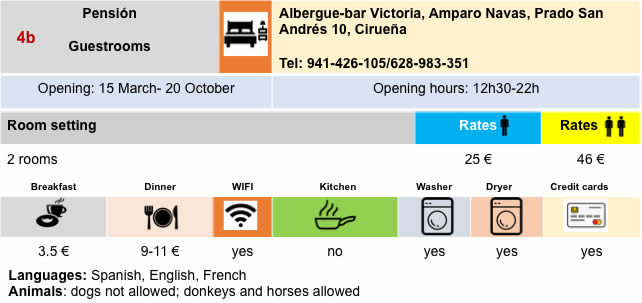

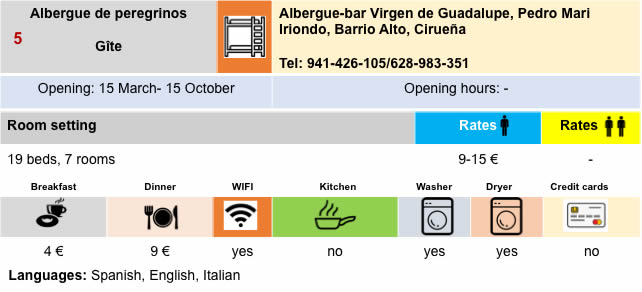

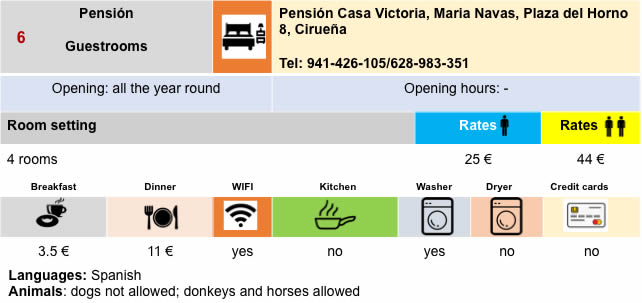

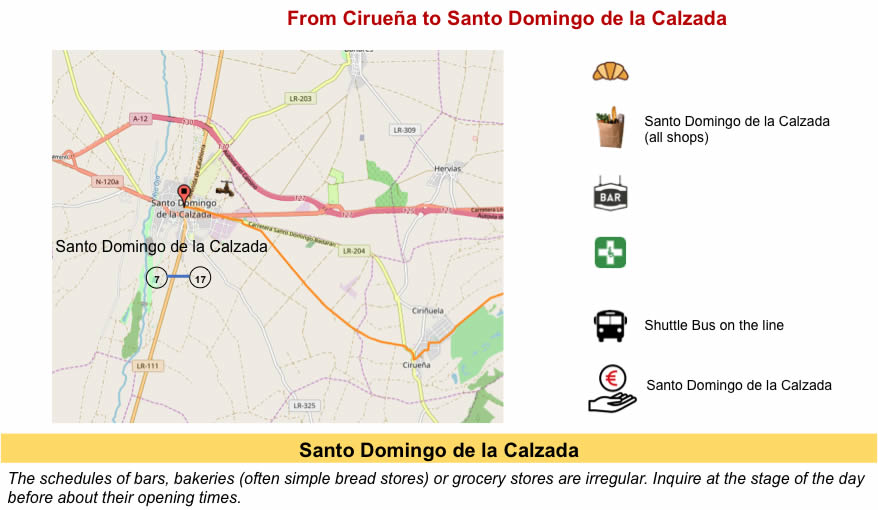

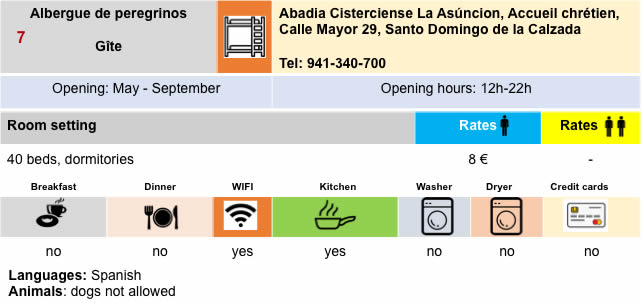

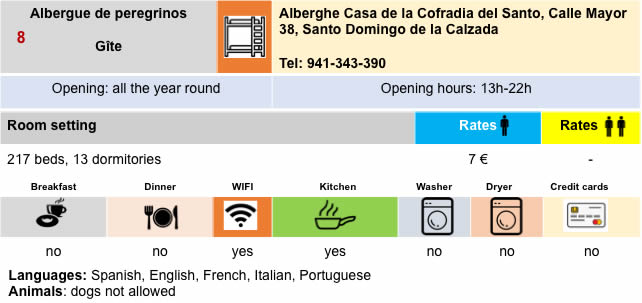

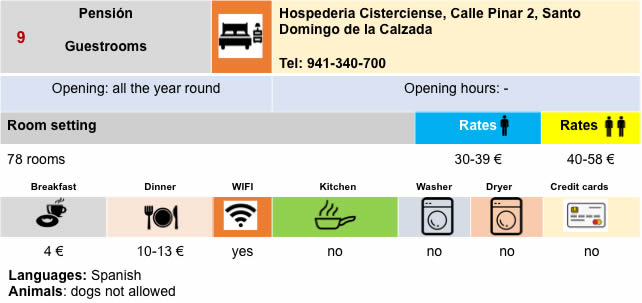

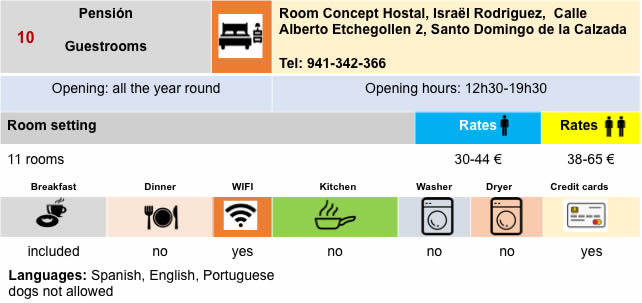

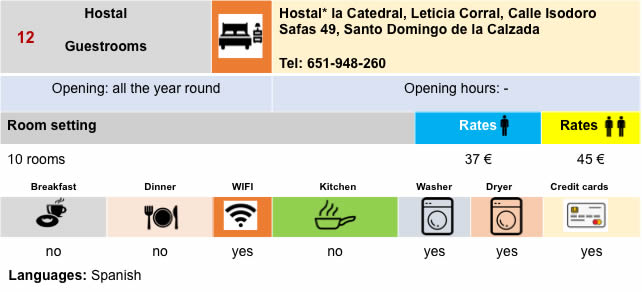

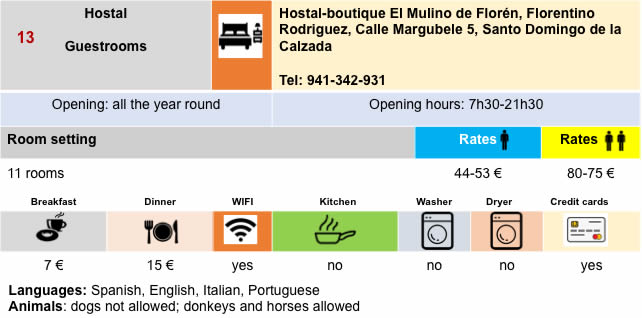

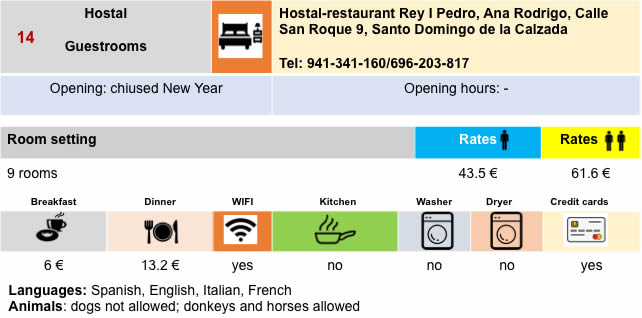

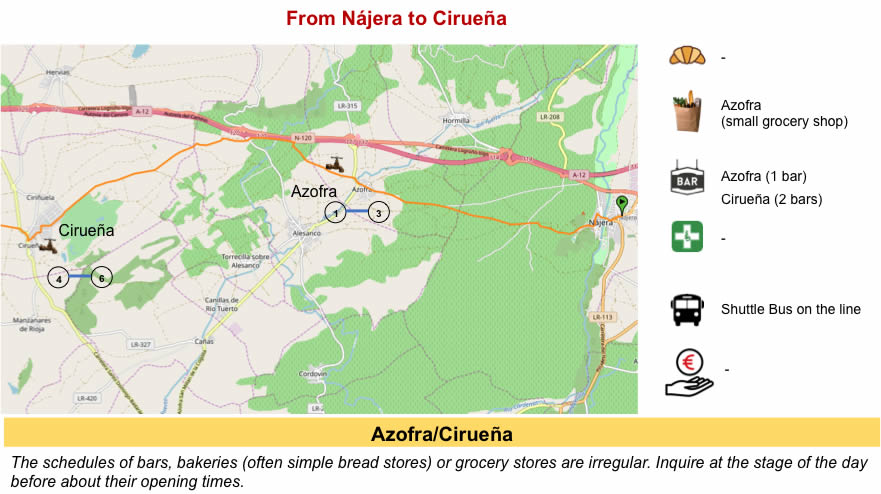

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 10: From Santo Domingo de la Calzada a Belorado |

|

|

Back to menu |