Long life to N-120 road

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

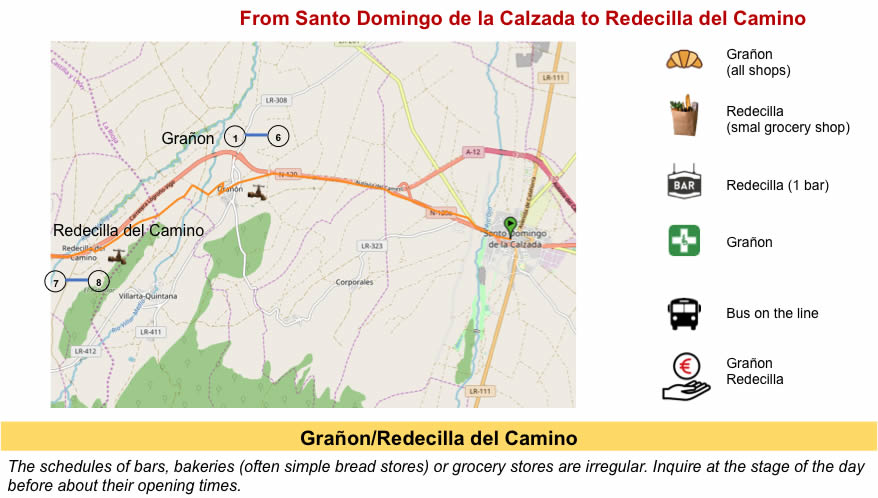

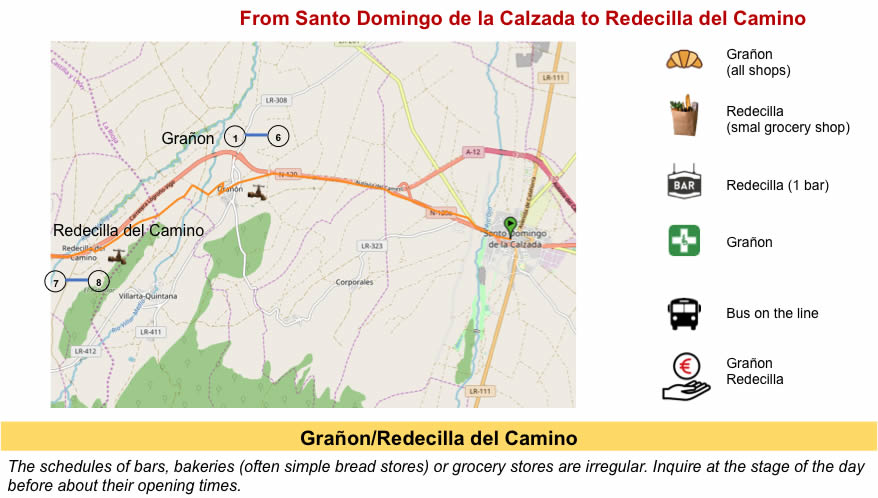

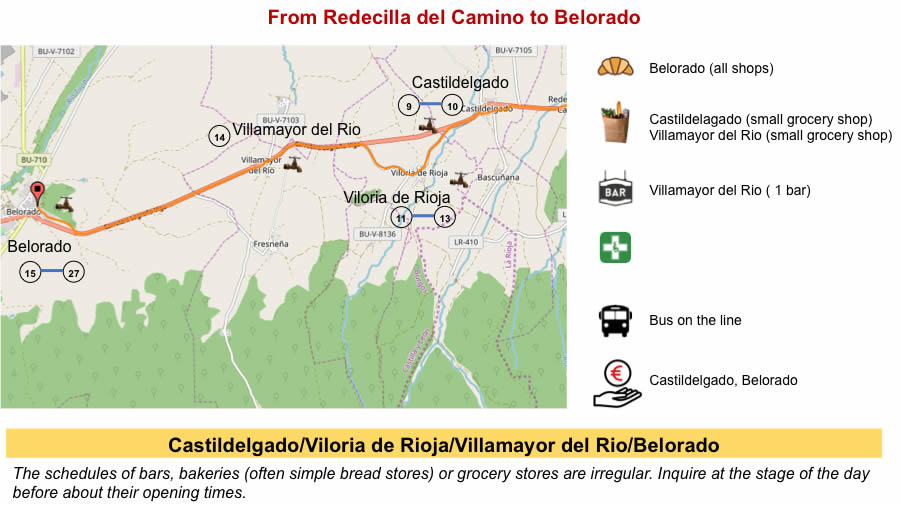

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-santo-domingo-de-la-calzada-a-belorado-par-le-camino-frances-33790819

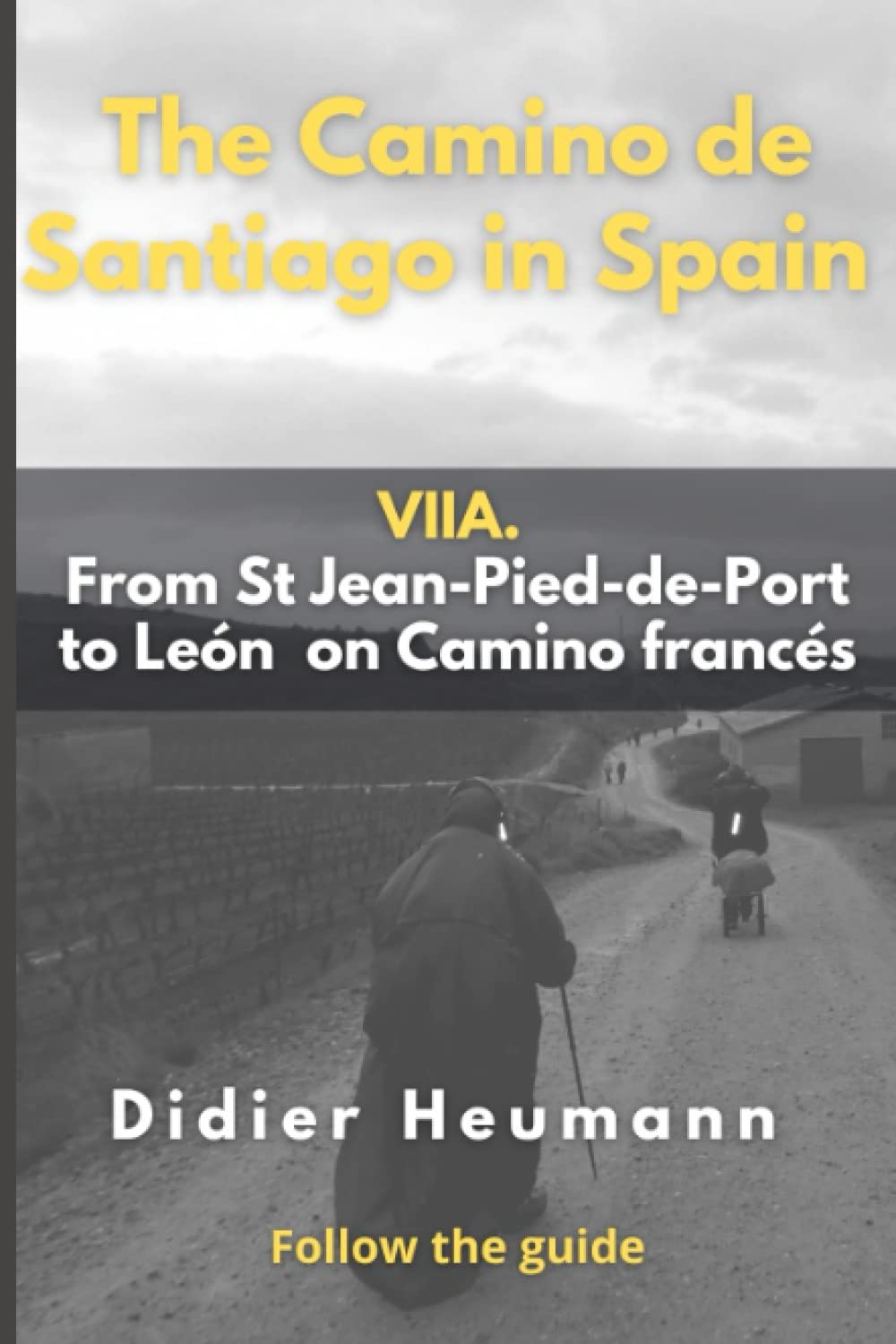

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

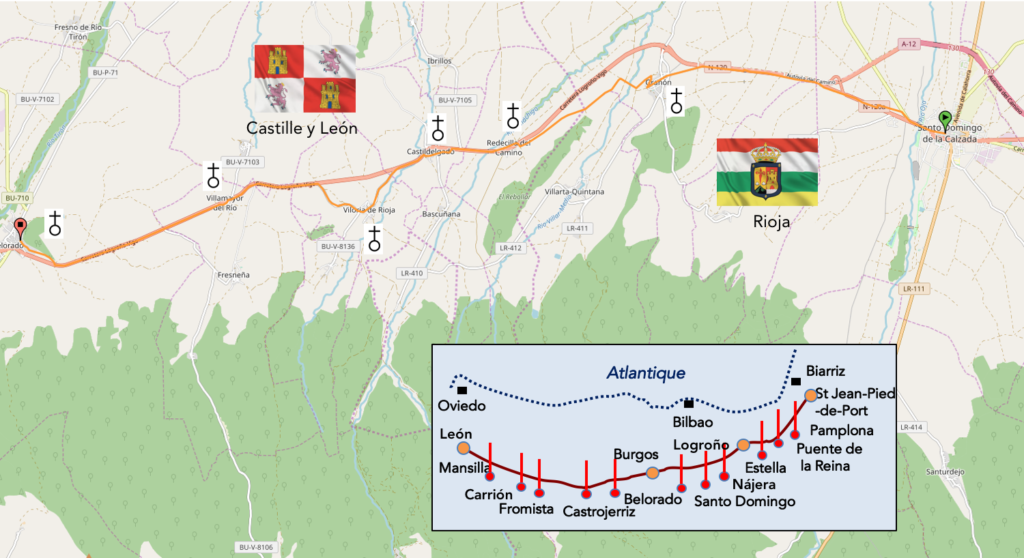

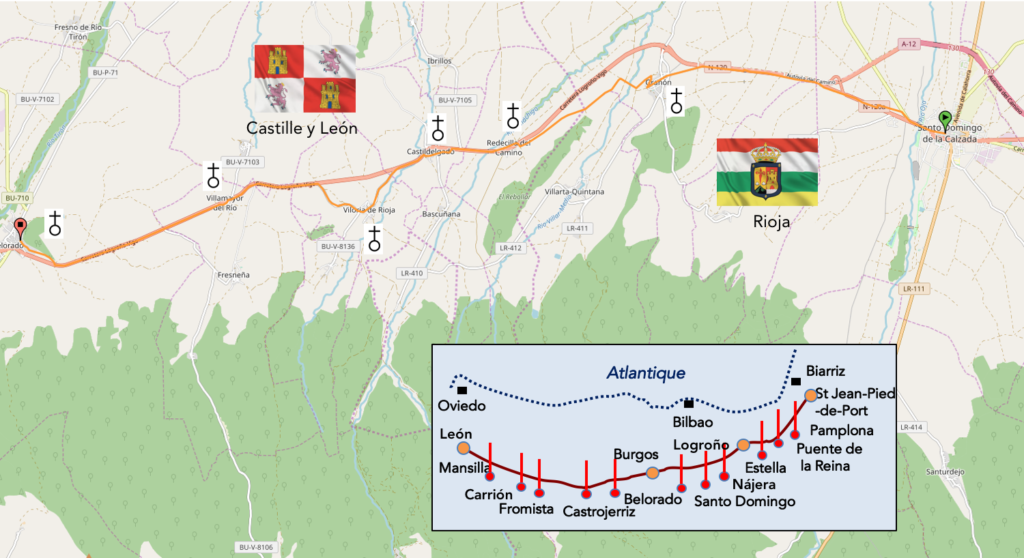

Today, the Camino will leave Rioja to run for many stages in Castile y León, the most extensive region of Spain. In the confines of Rioja, the vines have disappeared to make way for the incredible grain surfaces of the Meseta. Come on, today you will get a more precise idea, clearer than the one you read in the guides, about what will be the continuation of the journey to León for many stages, with some exceptions. Because here your feet will directly measure space and geography. You will also have a very good taste of what is the N-120, this road that crosses the country from here and goes to the sea. You will have plenty of time to tame it, and, who knows, taming it in your imagination.

Castile y León traces its history back to the medieval kingdoms of Castile and León, around the Xth century. Together with Asturias and Navarre, they took part in the Reconquista, to reconquer the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims. The two kingdoms were united intermittently until finally merging in the XIIth century. The first dynastic union of León and Castile took place in the XIth century, when Ferdinand I, Count of Castile, claimed the crown of León. Although he promoted himself emperor of all Spain, the union ended on his death, when Castile, León and Galicia were divided by his sons who fought to the death, dividing up the empire. It was not until Ferdinand III of Castile, later canonized as San Fernando, that the definitive union of the two crowns took place.

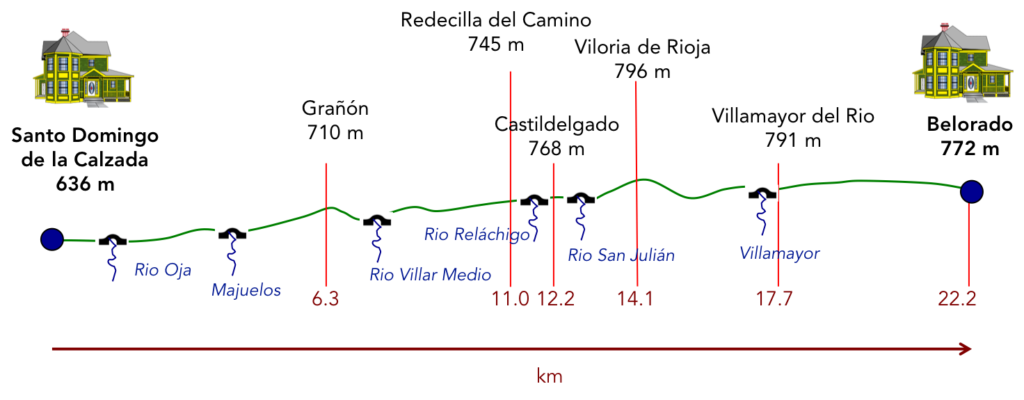

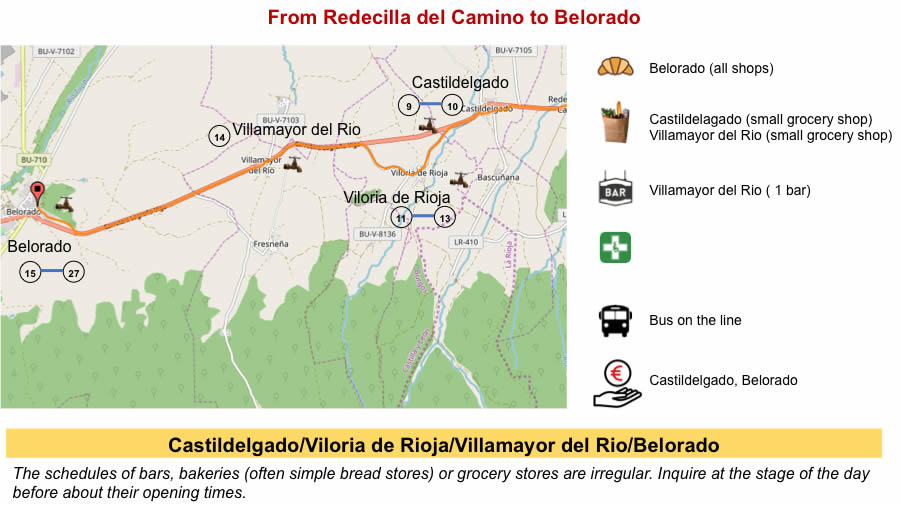

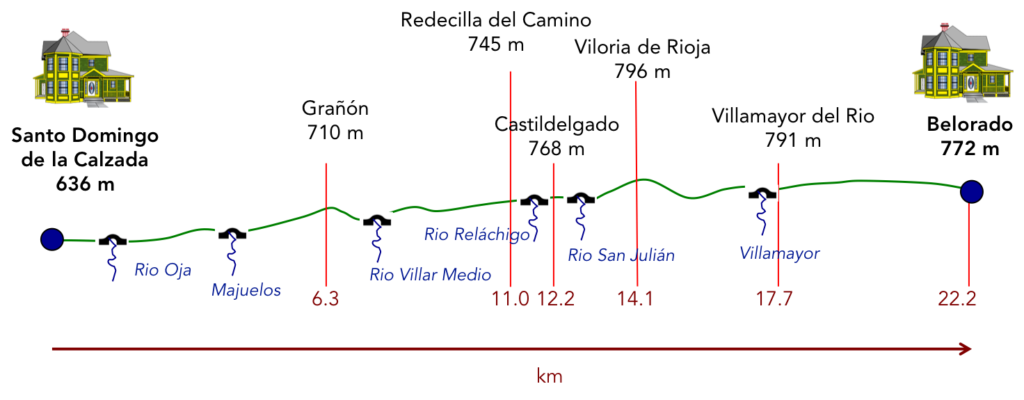

Difficulty of the course : Slope variations today (+308 meters /-195 meters) are weak. There are no major difficulties on the course, at most some ups and downs a little more pronounced between Castidelgado and Viloria, but nothing bad.

In this stage, most of the route is on the paved roads, often along the N-120 road. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true dirt road, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 5.2 km

- Dirt roads: 17.0 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

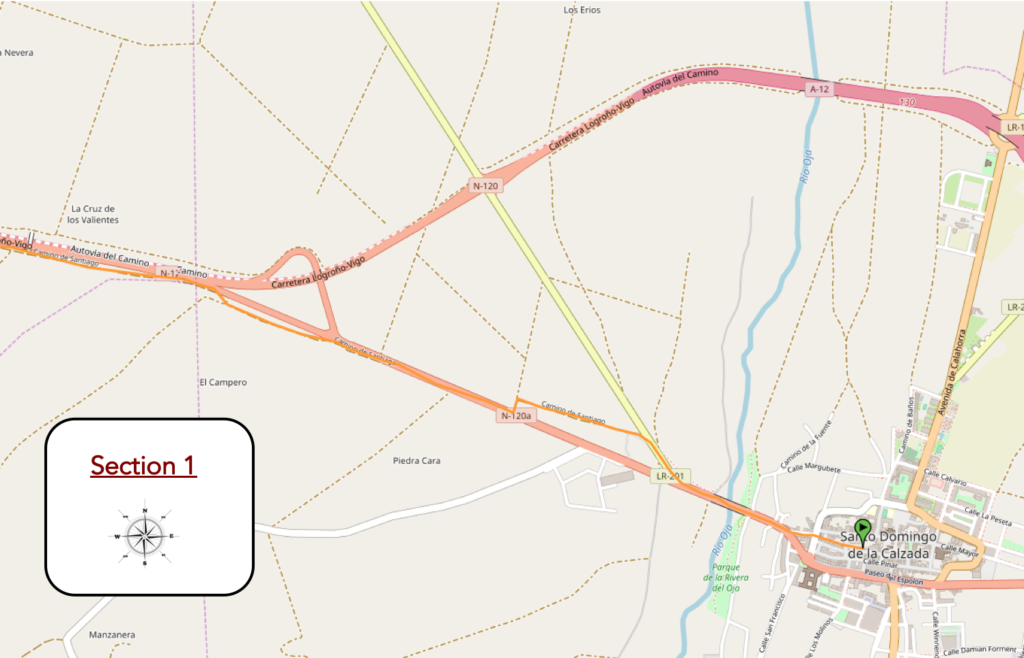

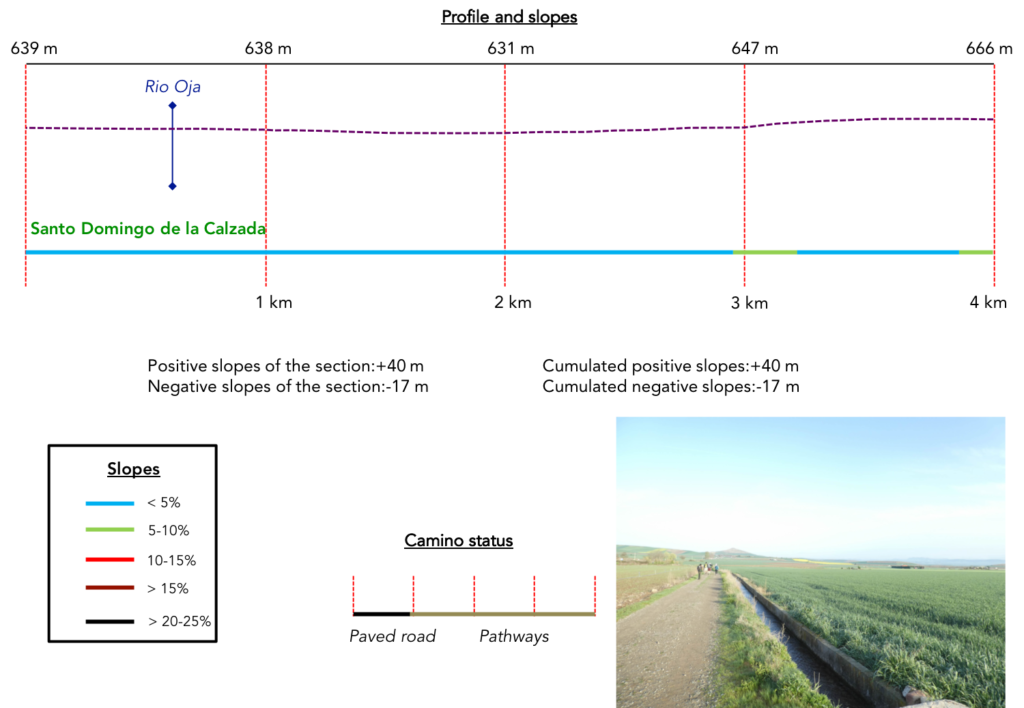

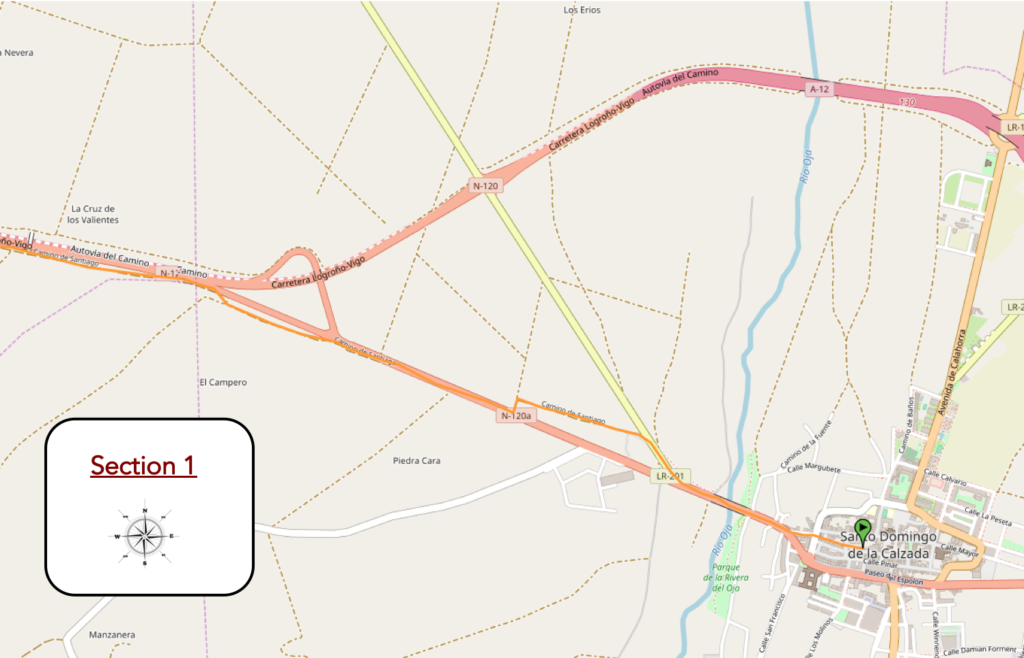

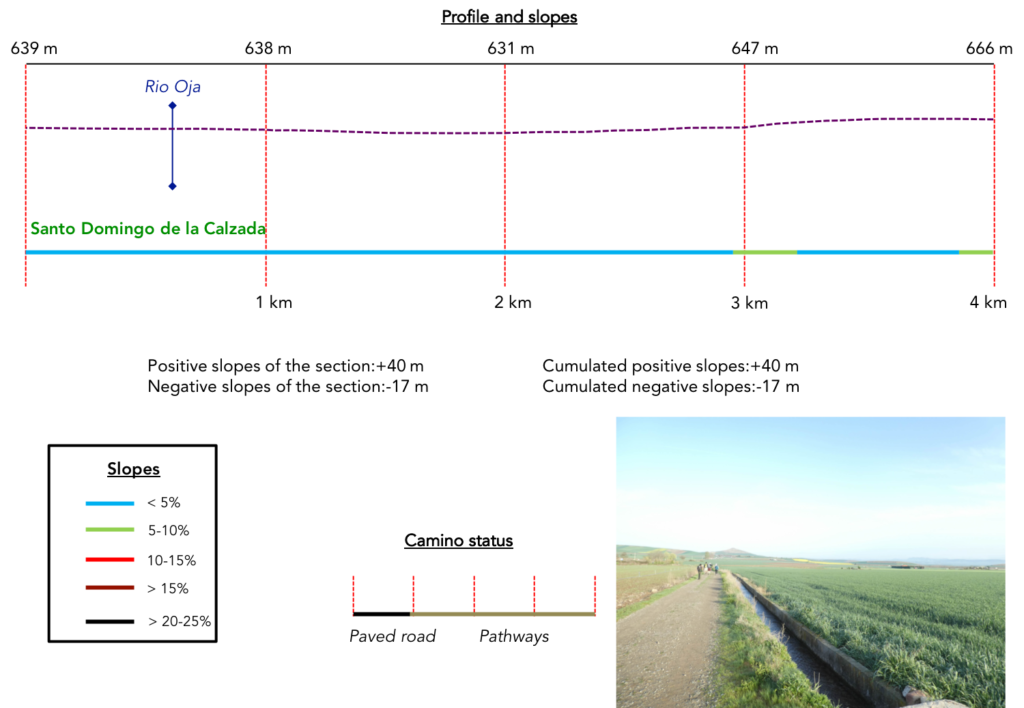

Section 1: Along N-120 road.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

Today the weather is favorable. Good weather is announced in La Rioja, but the forecasts for the end of Holy Week are terrible. The route leaves the Cathedral of Santo Domingo….

| …and continues on Calle Major, on the other side of the borough, in a less historic part. |

|

|

| It then joins the San Marco convent, at the end of the borough. |

|

|

| At the exit of the borough, the Camino passes near the hermitage of Pontus, a neo-Romanesque chapel, dedicated to Santo Domingo, erected at the beginning of the XXth century, near the Rio Ojo. This whole region was once a great swamp, which the good saint modified for the passage of pilgrims. This chapel is the symbol of the colossal work carried out by the saint. The Puente de Santo Domingo (aka Puente del Santo) is built on the same spot where Santo Domingo built the bridge in the IXth century.. |

|

|

| The Camino then runs through the cereals on a wide dirt road, for a few hundred meters to the right of a small departmental road which leaves the borough to join shortly after the N-120 which bypasses it. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses it to find himself on the left of the road. |

|

|

| And all this nice little world of pilgrims lines up along the road, along the irrigation canals. At this time of year, the sunflowers are barely emerging from the ground. But, this region is known for its sunflowers. |

|

|

| Sometimes a vehicle passes. It is said that motorists like to honk their horns, roll down the windows and encourage pilgrims. But here they must be tired of doing it. They see hundreds of them parade every day. |

|

|

A few bushes, rare black poplars and the sun that floods this universe of cereals on the gentle hills. We have a little pity, in anticipation, for the pilgrims who will pass through here in summer. Today it is 12 degrees in Rioja.

| In the Meseta, the pilgrims are quite discreet, except for some talkative Americans. They may save themselves. This will change much further in Galicia. |

|

|

| Our Korean friends are now almost integrated into the landscape that you might think they are Spanish. |

|

|

Further on, a cross, a bench almost in the shade under the trees, and some are already taking a break.

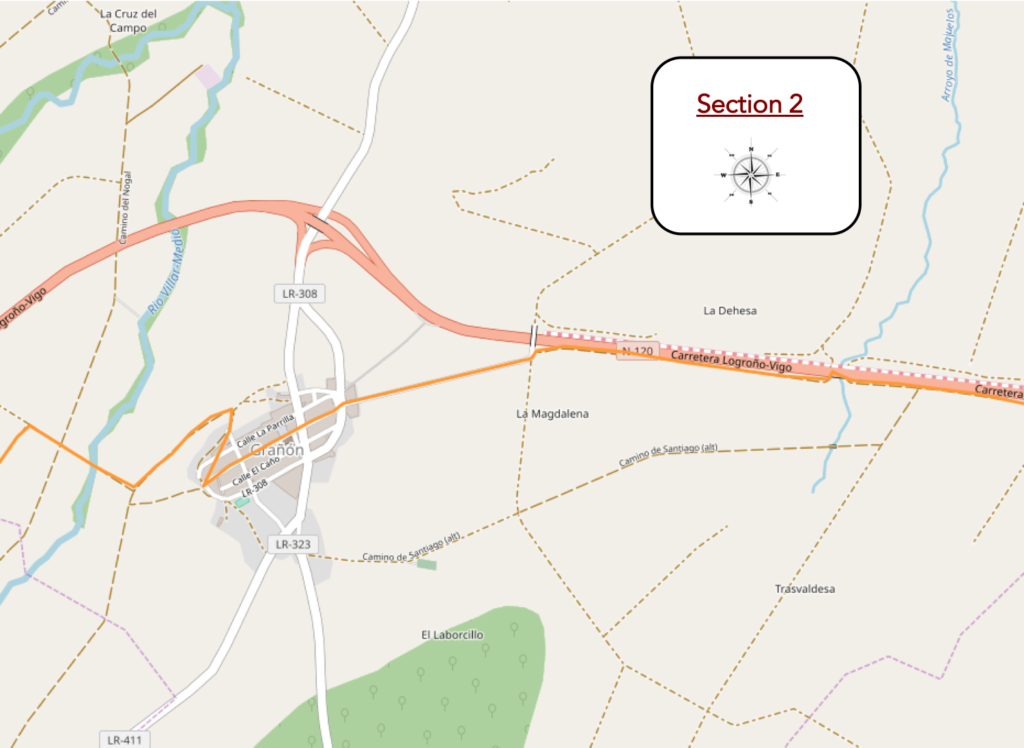

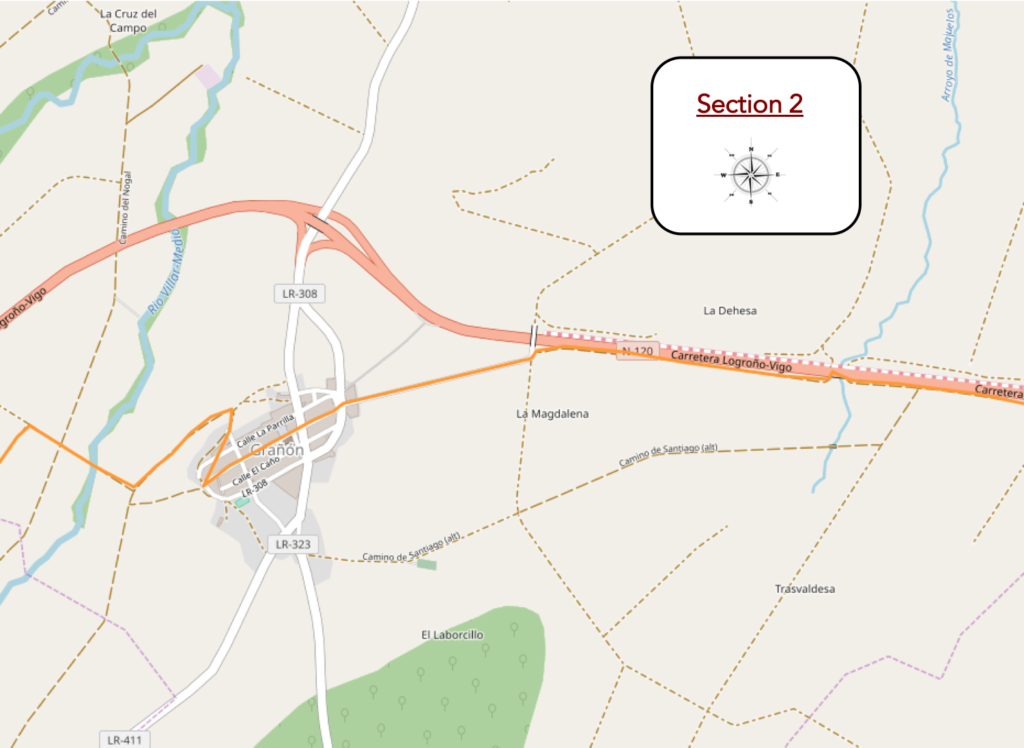

Section 2: The Camino will forget for a moment N-120 road.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| At the level of the cross, you are at the junction point of the secondary road and the N-120 road. From now on, the N-120 road will become your big business. Here, a Swiss proudly wears a bear on his luggage, symbol of his canton of Bern. |

|

|

| Fields of cereals on the right, fields of cereals on the left, sometimes a few crops of emerging sunflowers, and in the middle the pilgrims break down on the wide pathway in the company of the national road. What happiness, right? |

|

|

| Further on, the dirt road approaches a structure to cross the Majuelos stream. In front of you is the village of Grañón. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the pathway climbs on the hill next to the national road. |

|

|

| In these stages where no natural obstacle disturbs the space, the monotony and the uniformity of the place, you will often have the feeling of being very close to the goal. But it’s not really progressing. For you, the village is still just as far away. |

|

|

| However, a bend and the village appears way up there on the hill at the end of the tarmac road. |

|

|

Grañón is the last village in La Rioja before entering Castile. It is an important village, the proof there is even a pharmacy, which always signs the real villages throughout Europe. It has always been a border town. It dates back to the IXth century, when the King of León built a castle there. It was involved in territorial struggles between the kings of Navarre and Castile at the end of the XIth century.

Of course, when you pass through the village, in fact a long-cobbled street, you cannot guess that at any time, in the Middle Ages, there was a castle here, walls. The city belonged to Castile and the Camino de Compostela was instrumental in its development. Santo Domingo de la Calazada diverted the way to pass through here. You see that the routes of the tracks have always been a political and economic question. Nothing has really changed since the Middle Ages.

| In the middle of the village, the church of San Juan Bautista still has baptismal fonts from the original XIIth century church, but it was built between the XVth and XVIth centuries. Everything is dark in this church, open for once. |

|

|

| The straight and narrow street extends well beyond the church. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the landscape opens onto the hills of Castile-y-León, verdant with cereals in the spring. You will therefore not have stayed long in Rioja, just to have noticed that there are vineyards, even if the track did not cross the region of the great wines of Rioja, which are closer to the Ebro River. But, you will at least be able to locate the country when you come across a bottle of rioja in your favorite supermarket. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a wide pathway, it looks like a highway, descends from the hill to the plain. On the horizon runs the N-120 road. |

|

|

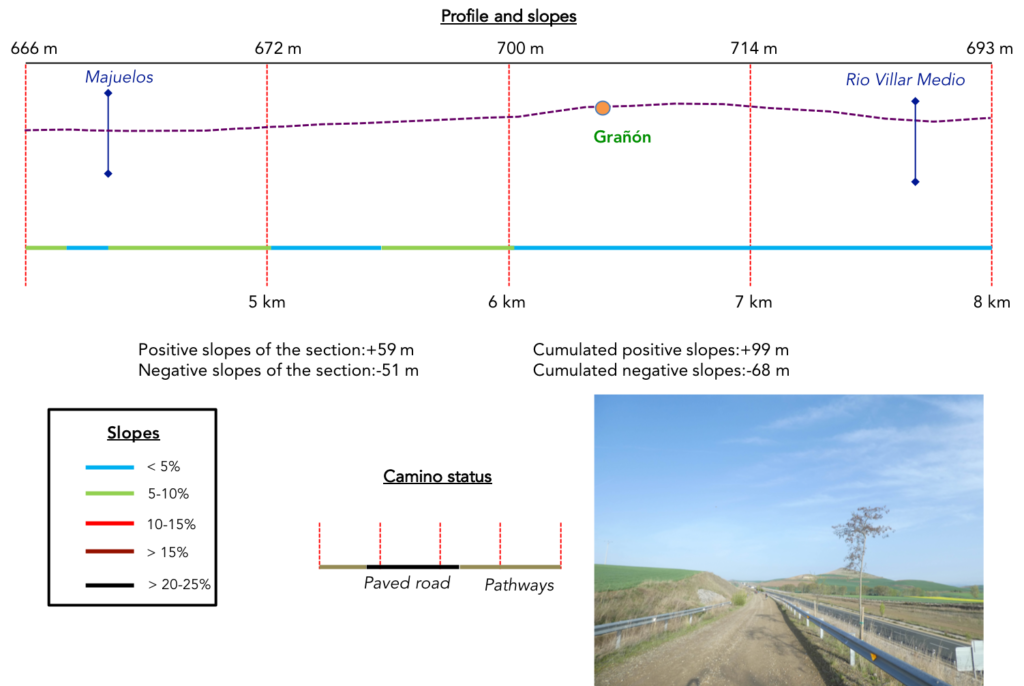

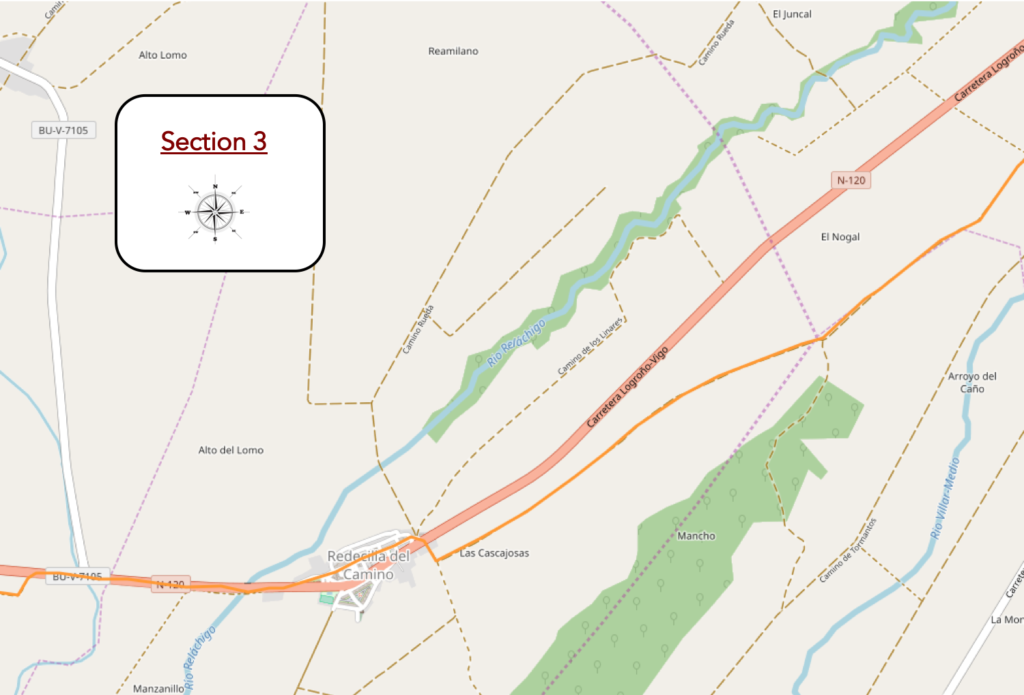

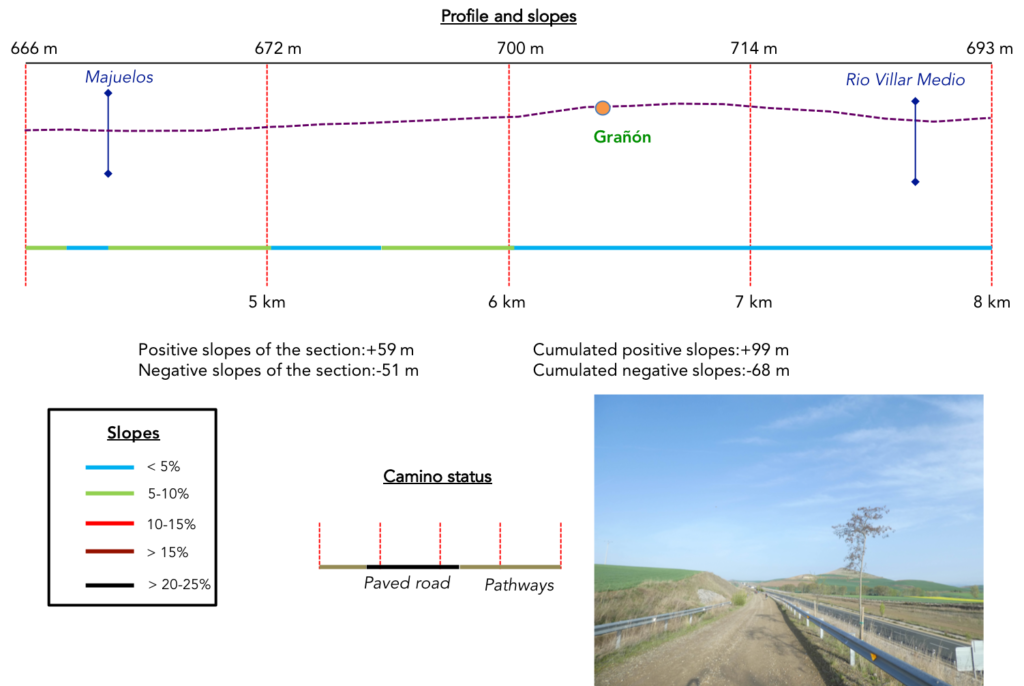

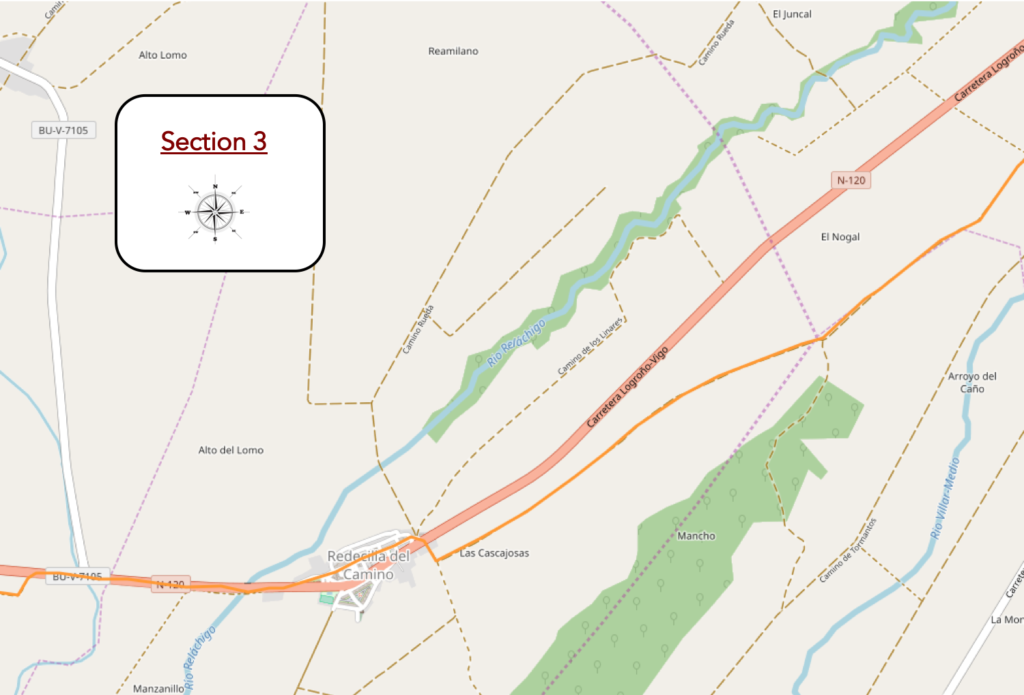

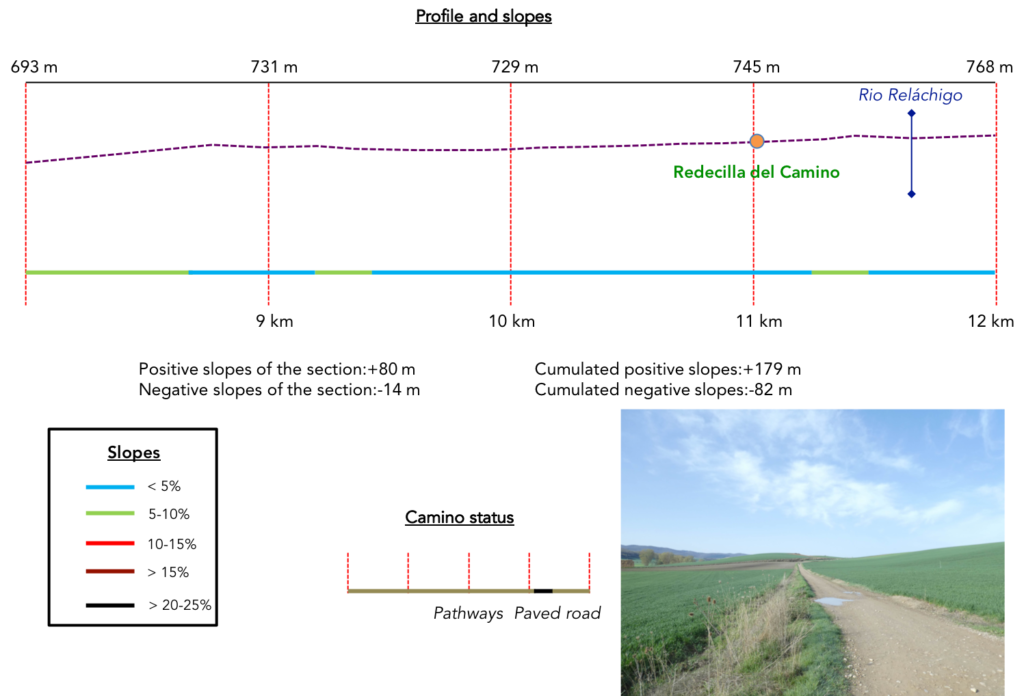

Section 3: From Rioja to Castile y León.

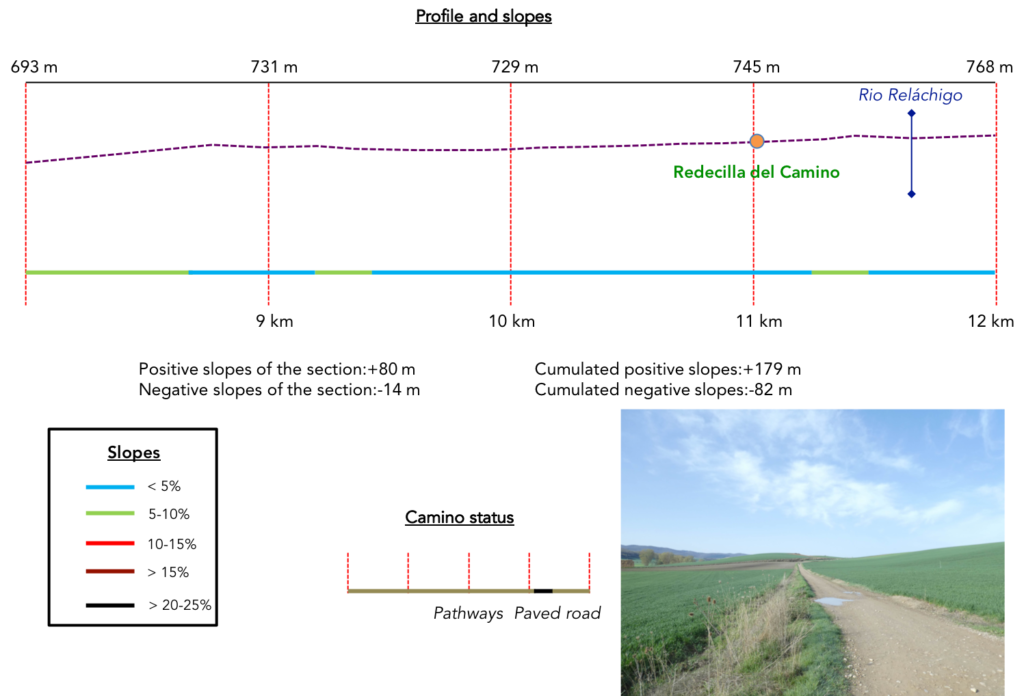

Overview of the difficulties of the route: some slight slopes.

| At the bottom the pathway crosses the modest Villar Medio stream and slopes up the hillside on the other side. |

|

|

| Here, there are no more vines, and there have not been any since Santo Domingo de la Calzada. There is only the immensity of fields of cereals and sunflowers. For space, infinity, nothingness, some grumpy pilgrims will say, rejoice, here it is only just beginning on the track that gently climbs the hill. Not a tree, not a single shady spot on the horizon. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, a sign indicates that you are in Castile y León. Where does the border pass, for the pilgrim, it doesn’t matter, but for the peasant who has his fields here, who knows? The autonomy of the regions of Spain means that taxes are not the same everywhere. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway becomes long, very long, almost straight in the cereals to go to the next village, to Redecilla del Camino. Fortunately, for many pilgrims, the N-120 road is a little out of the way, which lessens their depression a little. One wonders to know in which universe the pilgrims of the Middle Ages traveled. No doubt there were trees, before the peasants transformed the country into a green desert in the spring, brown in the summer. The only thing that remains is the relief, the hills and the plains that men have not yet modified. |

|

|

| Desire to go there, to walk and to walk again, over endless lengths, far behind the hills, to go and meditate for the salvation of one’s soul, near a saint whose veracity is not authenticated, all this program, in the Middle Ages, pilgrims hardly asked the question. But nowadays? And the pathway goes on again, with a little further on the tarmac. Looks like an airstrip. |

|

|

| However, further on, the Camino still lands in the village. The village of Redecilla del Camino, whose existence is documented since the Xth century, was on the old Roman road that Santo Domingo de la Calzada reconditioned to be the main route of the Franks to the tomb of Santiago. It was called Radicella in the Codex Calixtinus. In the XVIth century, there was a hospital for pilgrims in the village. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, near a memorial overlooked by a Calvary, the fountain offers fresh water. In fact, in this part of Spain, they are not real calvaries, but jurisdictional rollos, columns generally made of stone and often surmounted by a cross, marking the limits of medieval territory. |

|

|

| The Camino then crosses the village. You see more and more houses made of exposed brick, others even in cob and adobe. The villages of Castile are not opulent, deserted most of the time. The only living ones that you see are the pilgrims or the locals who serve the pilgrims in the “albergue”. There are virtually no cattle here. |

|

|

These villages, for the most part, have no shops, or rarely a small shop with the essentials, or sometimes a pharmacy like here, but all have a large church. It is always like this in Spain on the course. The baroque Nuestra Señora de la Calle church was rebuilt between the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, closed of course.

| At the exit of the village, the Camino hastens to find the N-120 back… |

|

|

| … and shortly after to cross the Rio Reláchigo. |

|

|

| The Camino then borrows, for a brief memory, part of the old N-120 road. Pilgrims who have passed here in the past all remember the old N-120 road, a real nightmare at the time. Next to it, today passes the new national N-120 road, a little frequented boulevard with here a little more sustained traffic. This is so because the highway does not pass around. |

|

|

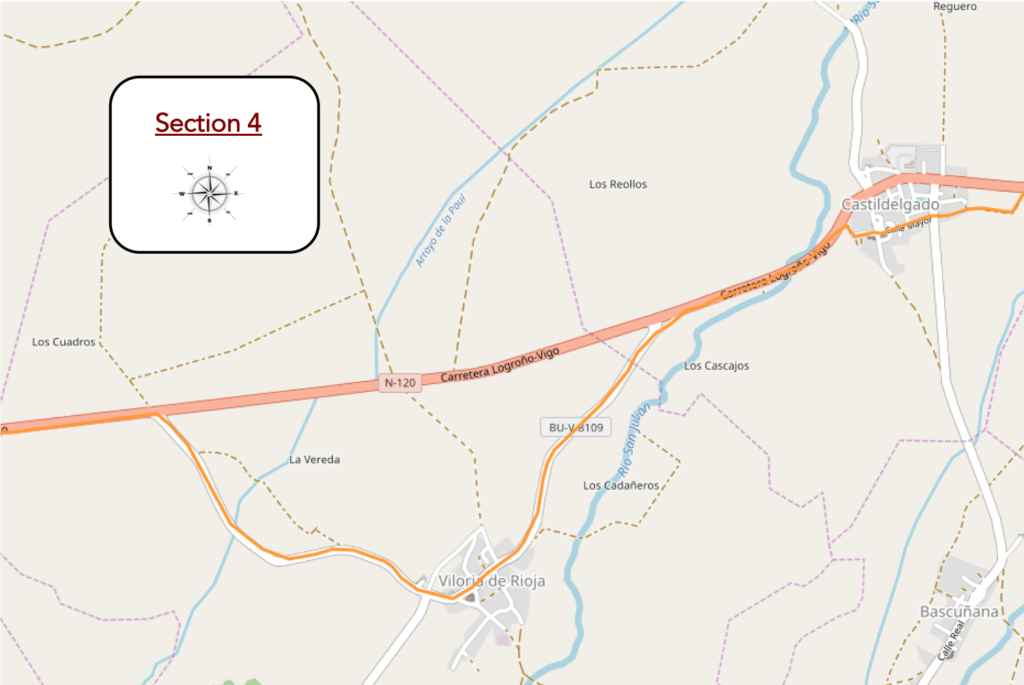

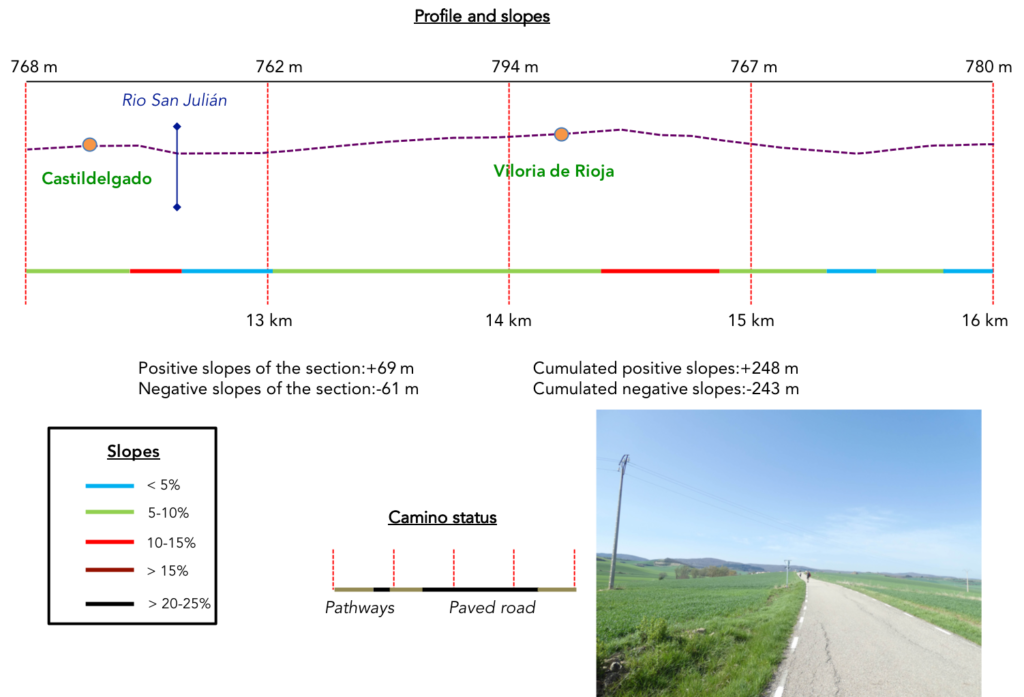

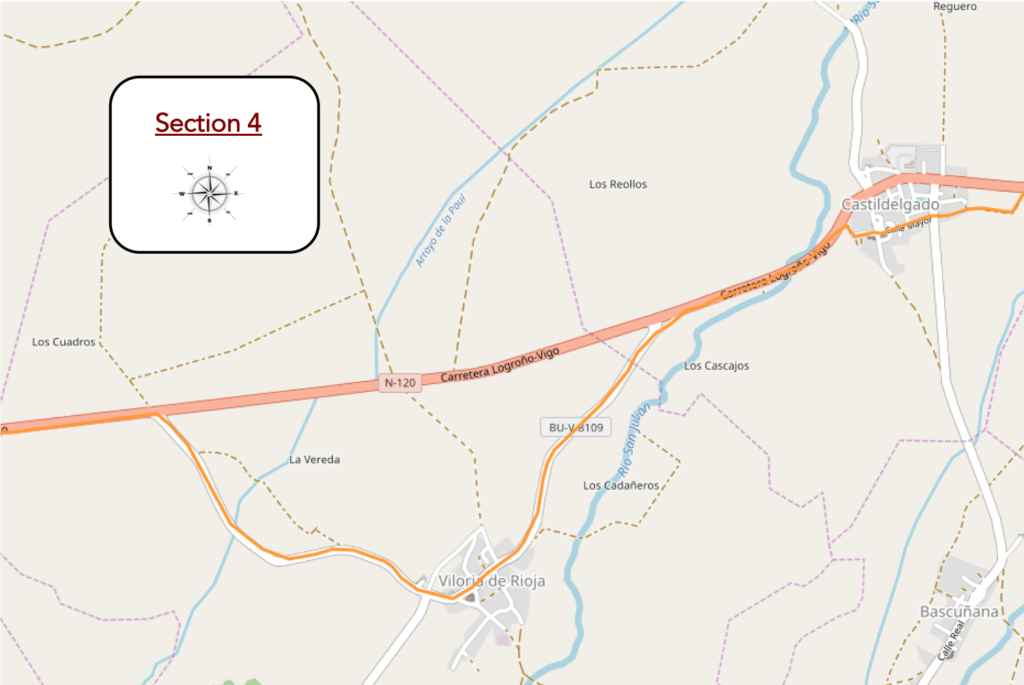

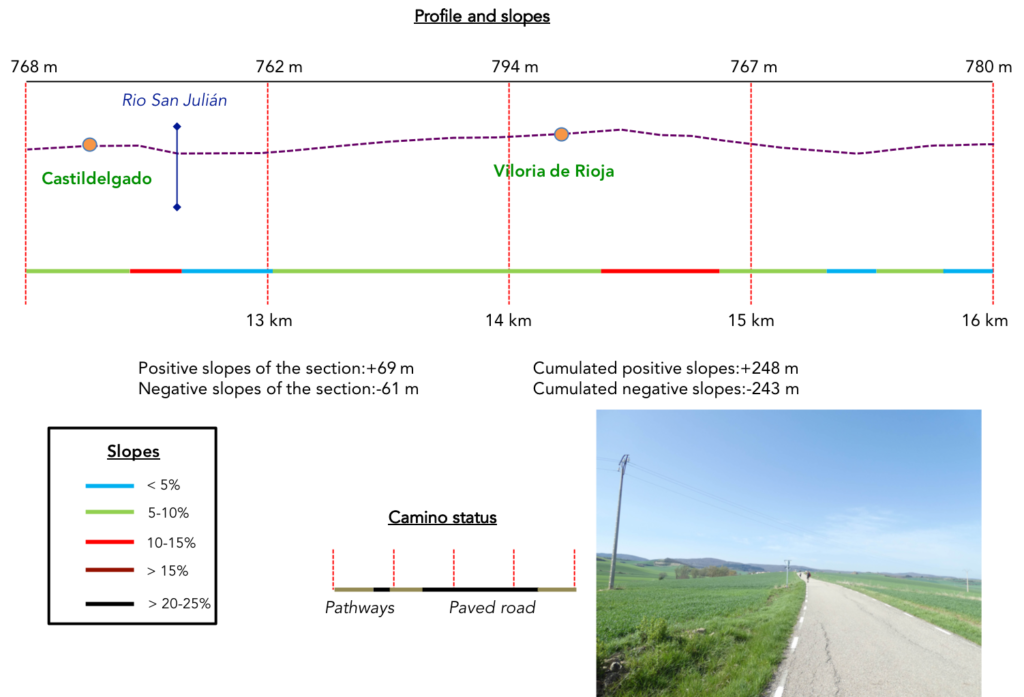

Section 4: Nothing changes here in the landscape.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: the only part of the course a little more tormented, but without great difficulty.

| The Camino quickly joins the new N-120 road and proceeds on the dirt road on the side. Quickly looms the village of Castildelgado at the end of the long straight. Here, farmers must have planted corn recently in the middle of barley and wheat. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway deviates a little from the main road, as if to give you the illusion of breathing a little easier. It’s the Easter holidays, and you sometimes see a couple or a father with children. The latter seems more cooperative than other comrades of the same age encountered on the march. But the detour is a decoy, because the pathway quickly arrives at Castildelgado. |

|

|

| The village is as depopulated as the other villages in the region, as poor as well. There is of course the “albergue” and the large church. |

|

|

| There was also a hospital for pilgrims, now in ruins. The village has two monuments. The XVIth century Church of San Pedro is of late Gothic style. Inside are the remains of his most illustrious son, Don Francisco Delgado, who was Archbishop of Burgos. It has a slender tower and baptismal funds. We can only believe it; the church being closed. The other monument is the hermitage of Santa María la Real del Campo, with its Baroque façade from the XVIIth century, also closed. |

|

|

Koreans walk a bit like Chinese shadows. You can guess them by their gait in advance. You can talk with them, at least with those who know a few words of English. They remain as mysterious as all the mysteries of the Orient. One day, they will also have to create a track there at home, so that Europeans will get lost and perhaps not understand anything.

| At the exit of the village, the program of the next kilometers is displayed in front of you, like an open book. You see with your sharp eye the pilgrims marching to the next village along the national road. It’s no surprise, you walk there as soon as the pathway joins the paved road under the black poplars, near the San Julian stream. |

|

|

Further afield, the serenade with the national road begins again. In the distance, the advancing pilgrims are only small motionless dots on the horizon. And you are not alone on the way. Here also pass the lovers of the European route No1 which crosses Castile to go to Portugal. These, you don’t know who they are. They do not wear a European crest on their bag as some pilgrims on the way do with their shells. But, we suspect that they must not be legion.

| Further on, the Camino leaves the axis of the national road for a small paved road that heads towards Viloria de Rioja. A surprise here? Are you going to temporarily leave Castile to return to Rioja, which would have pushed its horn a little here? Is that why the road is paved? People’s lives are often about doing little things, which are not unimportant for you, but decisive for them. |

|

|

| Here, the N-120 runs further offshore, lonely. |

|

|

| When the road arrives at the village of Viloria, people specify Viloria de Rioja. The village is the cradle of Santo Domingo de la Calzada. The name of the village is somewhat confusing, since it is not located in the current autonomous community of La Rioja and its population is entirely Castilian. The village has its origins beyond the XIth century, when there was already a village named Villa Oria. Alfonso VI of Castile annexed La Rioja in the XIth century. In the XVIth century, this entire region and most of what is today the autonomous community of La Rioja was part of the province of Burgos within the Kingdom of Castile. The division of Spain into provinces in the XIXth century separated this part of the La Rioja region, which became part of the province of Burgos. This part was called Riojilla because it is considerably smaller than the other part of La Rioja. La Riojilla includes the villages of Camino de Redecilla del Camino, Castildelgado, Viloria de Rioja, Vilamajor del Río and Belorado. |

|

|

| However, nothing distinguishes a village of Rioja from a Castilian village. They are the same poor brick and cob houses, the same church, the same “albergue”, except that here people really insist on remembering that Santo Domingo was born here. |

|

|

We understand a little the pride of the people of Viloria de Rioja. 1019-2019, the millennium of the road to Santo Domingo, perhaps, but what a fuss!

| At the exit of the village, the road skirts the hill and descends towards the N-120 road which can be seen in the distance. |

|

|

| This one, you will not avoid it. Today you are married. And at all the cardinal points, low hills on the few stretch the cereals. The virtue of spring is to leave the fields green. In summer and autumn, it is earlier sadness around here. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway runs back along the N-120 road. Here, a pilgrim takes stock on his phone. Does he check his emails or does he make a point to find out if the track has left Rioja to find Castile y León? The direction signs on the roads are distressing or reassuring, it depends. Here you learn that by road you are still 7 kilometers to Belorado and 52 kilometers to Burgos? “America is far away, dad”? “Shut up, swim”. |

|

|

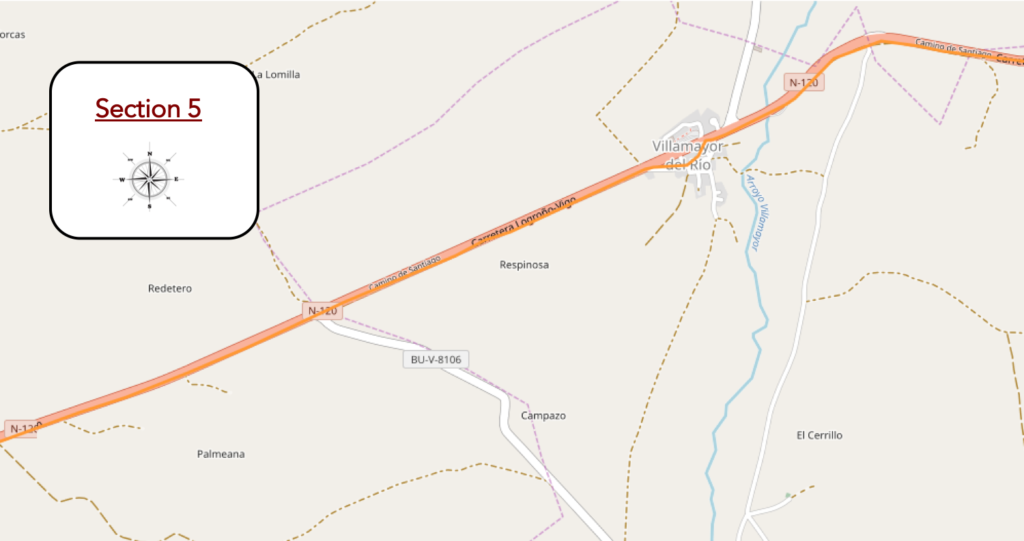

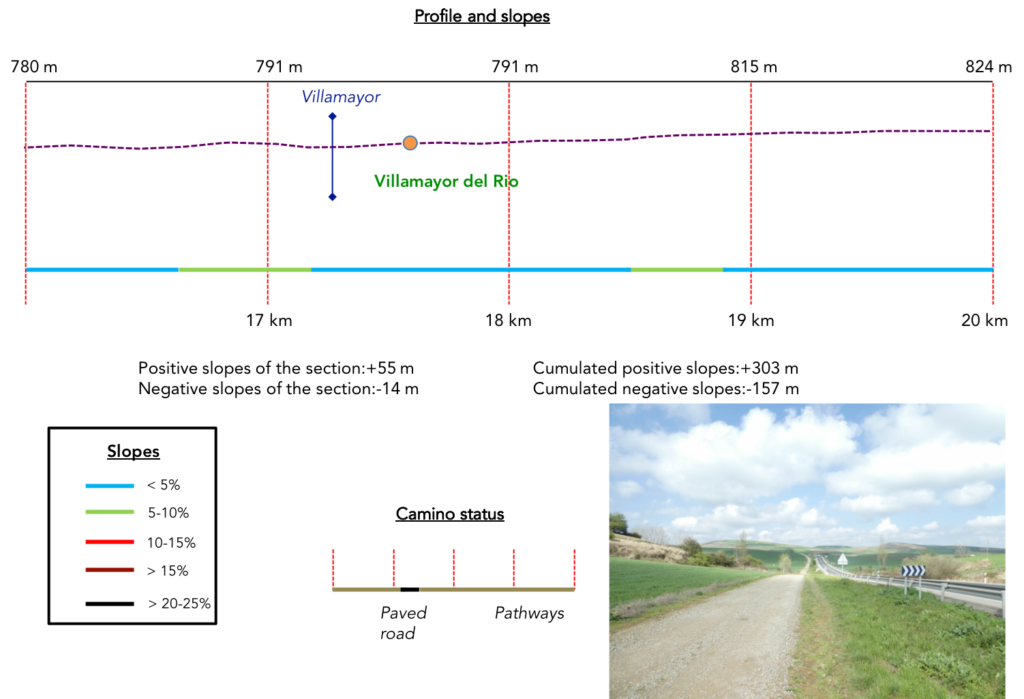

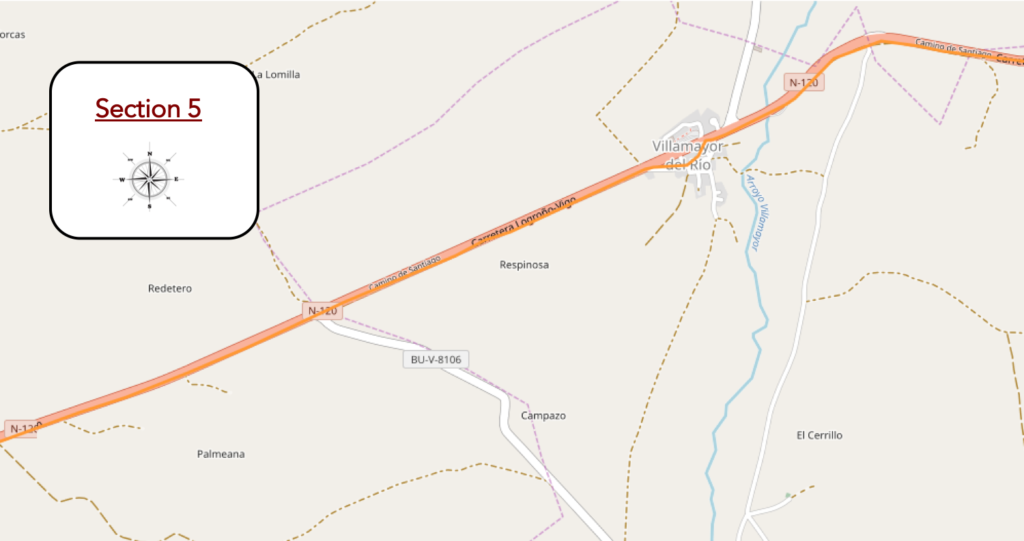

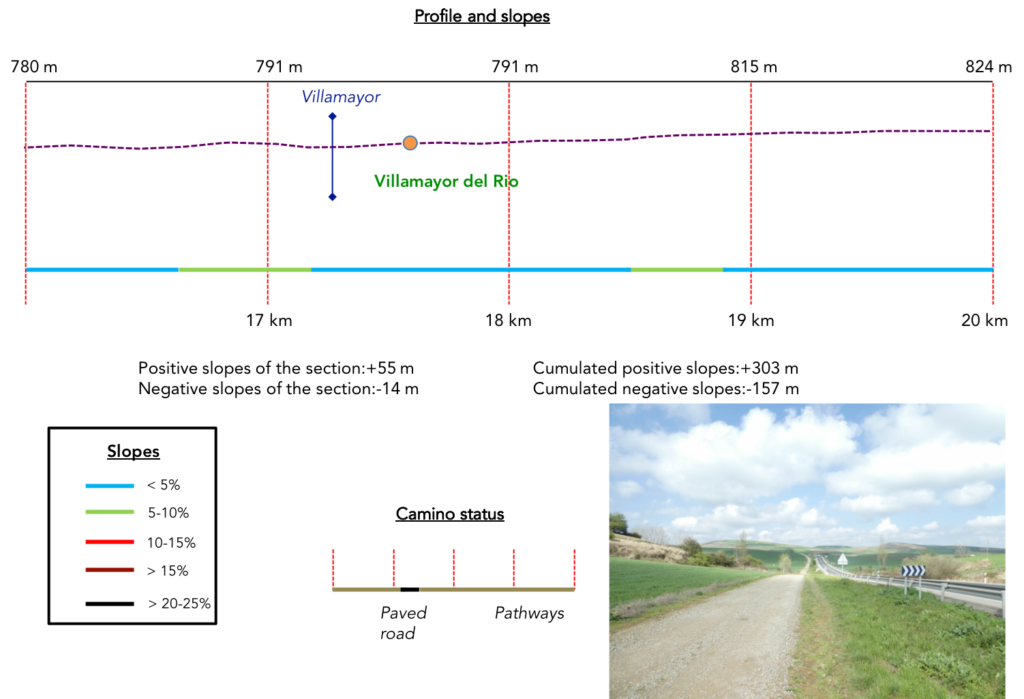

Section 5: Along the N-120 road which never ends.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Sometimes, the pathway and the road bob together on low hills, in an endless country, with so few landmarks, too big and to be constantly rediscovered, some will say, boring to the point of nausea, others will say. |

|

|

| In good weather, here the view is so far that discouragement is never far away. By car, it’s easy, you catch the landscapes that offer little interest. On foot, it’s different. Learning is commensurate with idleness or monotony. |

|

|

| Further on, a road which goes towards a village, not lost for all, cuts the axis. |

|

|

| Just after, you’ll see the village of Viollamayor del Rio. When you are told that there are few landmarks in this cereal desert. Shortly before the village, the pathway crosses the Villamayor stream. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, the Camino abandons the N-120 road for a bit. |

|

|

| In the small village, you will not be able to quench your thirst at the communal fountain or visit the Church of San Gil Abad, built in the XVIIIth century in neo-classical Baroque style. |

|

|

| On leaving the village, return to cereal fields and a few rapeseed fields and sunflowers along the national road. As you advance on the way to Santiago, the flow of pilgrims is diluted. As you can spend the night in all the villages, some stop there, and you will no longer see them. But, others arrive, in particular the Spaniards who occupy their Easter holidays today. |

|

|

| When you’ll walk by here, you will sometimes have the feeling of walking in the desert, without dromedary, without shadow as far as the eye can see, without goal and without possible return. But where have the Korean and American legions gone from the beginning of the journey? Like mirages, vanished behind the dunes? But no. The pilgrims, for the most part, even if the flow is diluted in the wide-open spaces, do the same stages as you. You will find them in the evening by the fire or on the bunks, in the “albergue”. |

|

|

Gait calibration is a well-known game among hikers. Some count the steps, a way to pass the time, like a kind of pause in the middle of disparate thoughts.

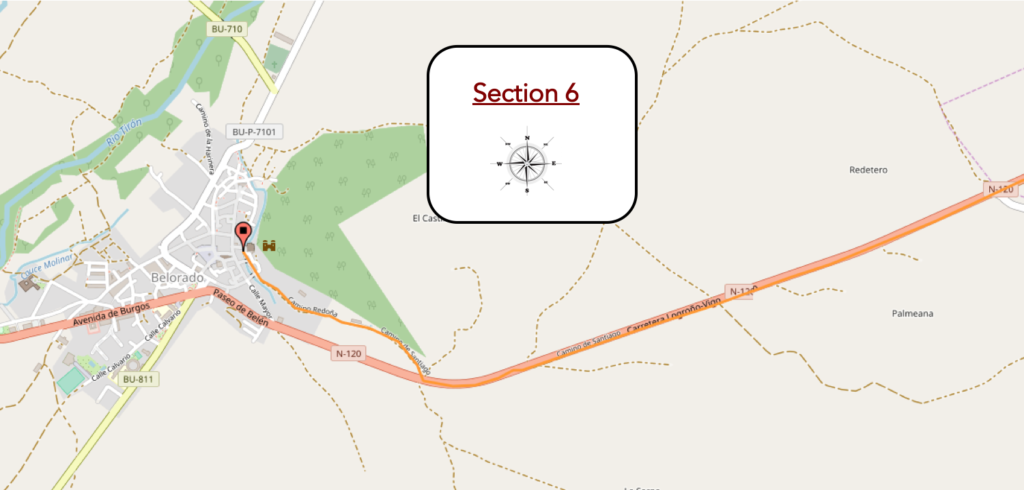

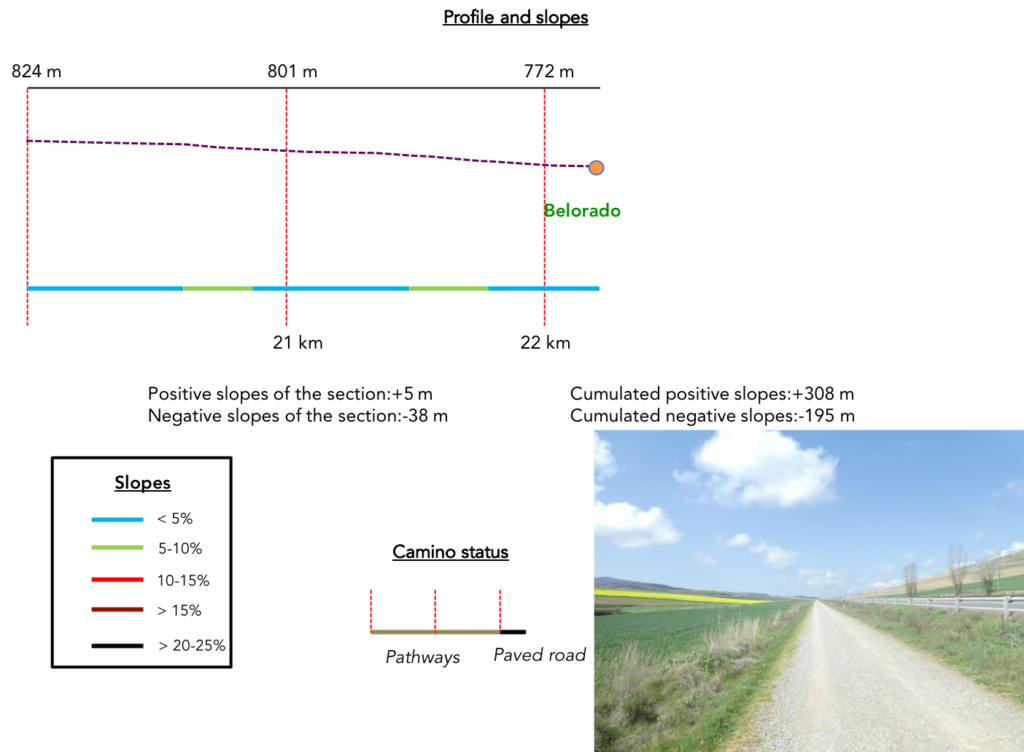

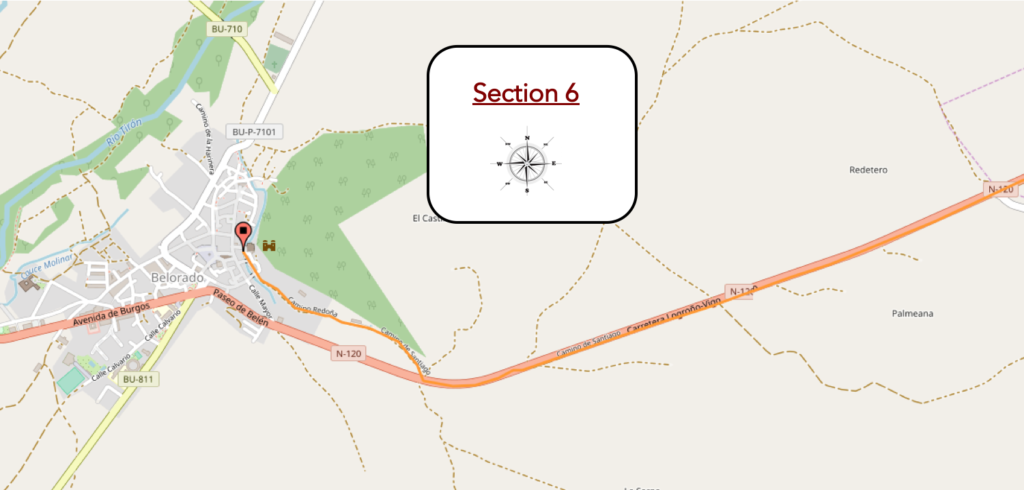

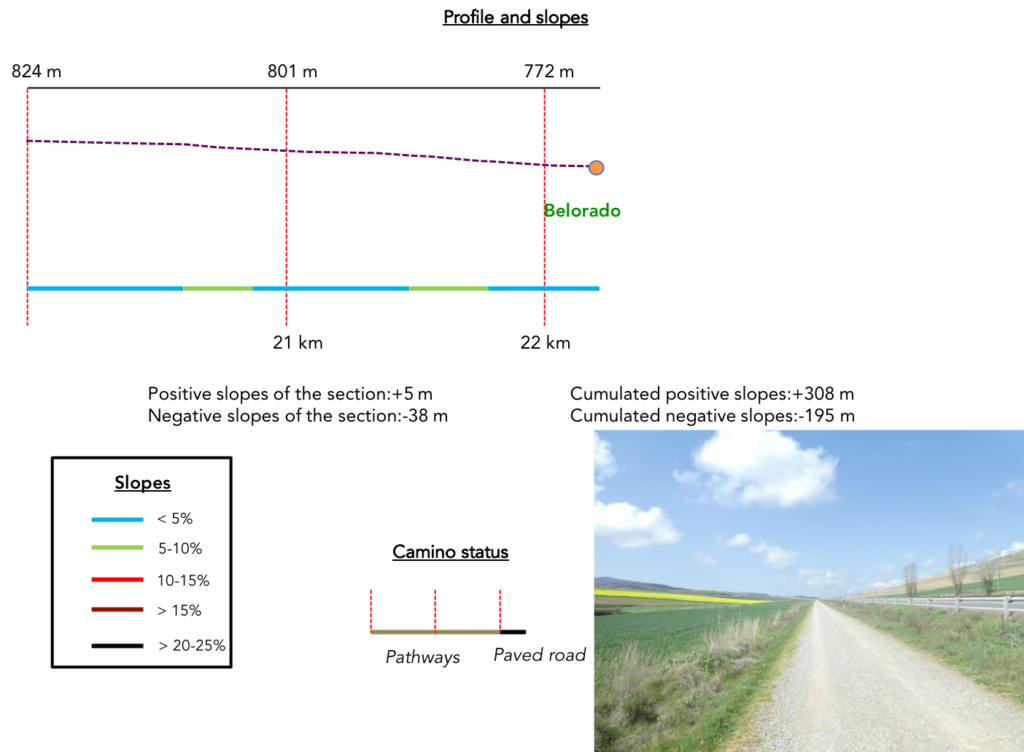

Section 6: Today there is Belorado at the end of the road.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Further on, the Camino intersects a road that goes to a distant village. |

|

|

| And all along the way, these granite markers that measure the distance. So many useless landmarks, which make the journey even longer, more haunting. |

|

|

| Imagine the pleasure your playmates will have when they walk here in the burnt corn, in summer or in autumn, with perhaps the empty gourd, at more than 40 degrees of temperature. So, we slow down a little, out of compassion, so as not to arrive at the “albergue” too soon. |

|

|

| What more can you add to such monotony? Oh yes! That we are delighted to arrive at the end of the stage and that our comrades who take the European path no1 will probably share our moods. Let’s understand each other. It is not the immensity, the tireless repetition of the cereal fields that poses a problem for many pilgrims. Some love it, others suffer it without cursing. No, it’s the road that spoils the fun, even if the traffic is not frantic on the axis. Pilgrims don’t like roads. They came to recharge their batteries in nature, real nature, not that of tar. |

|

|

| For today, the punishment ends, Belorado looming before you. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino crosses the N-120 road and continues down the hill above the village. It is also the direction of a castle in ruins, built during the conflicts with the Muslims in the IXth century. After the civil wars in Castile ended, the castle was left to deteriorate. Then, it is demolished again to avoid landslides. Today it is just a pile of stones. No pilgrim will take me up there, except to get a little more exercise. And even… |

|

|

| On the heights of the borough, the prices are announced with great fanfare. There is often little doubt about it: the first are the best served. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway slopes down towards the borough. Belorado is of Celtic origin. In the Middle Ages it was the border between Castile and Navarre. It was even a stronghold of El Cid. It is now the capital of Riojilla. |

|

|

| Belorado (1,800 inhabitants) was known as Belforatus, the “well pierced”, in the Pilgrim’s Guide. The streets of the old town are narrow, often winding. In the Xth century, Castile, in thanks to the inhabitants for having liberated the city from the King of Navarre, granted the city many fueros, including the privilege of holding a market on Mondays, a custom that still animates the Plaza Mayor. Like what, there are privileges that span the centuries. Let’s be realistic, without insulting the people here, pilgrims will not long remember this borough where there is nothing to do and not much to see. |

|

|

| There are two churches, both closed to our passage. The Church of San Pedro, on the town square, of medieval origin, was deeply transformed in Baroque style in the XVIIIth century. The other church, Santa María La Mayor, with its beautiful bell tower, redone in the Renaissance style in the XVIth century, leans against the cliff at the entrance to the borough. |

|

|

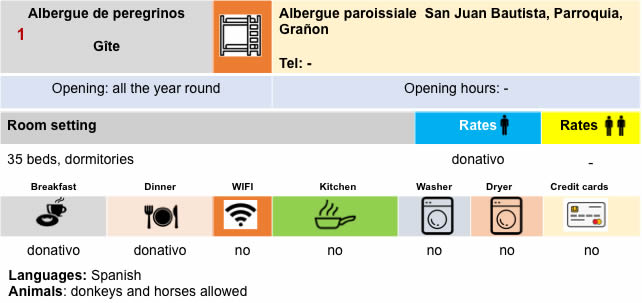

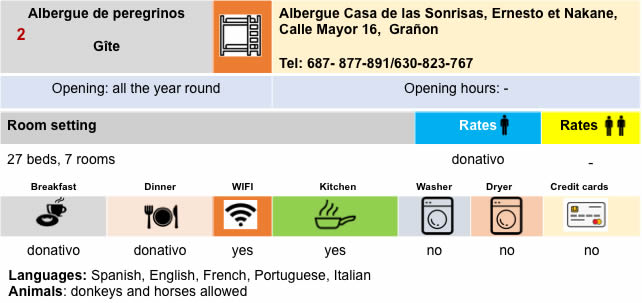

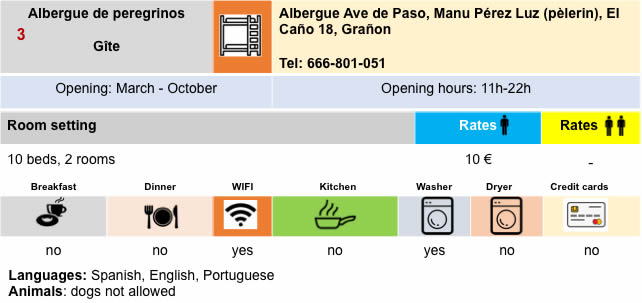

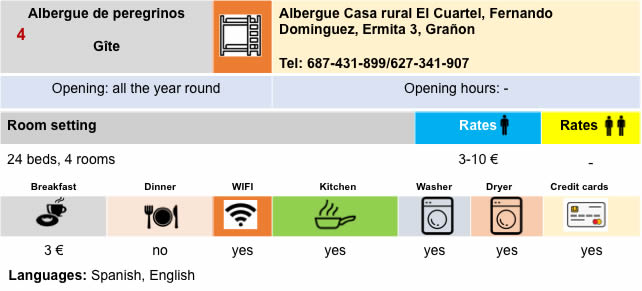

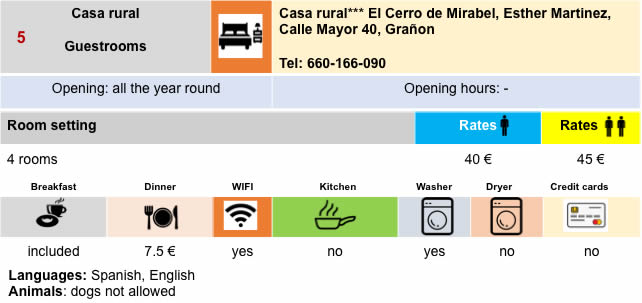

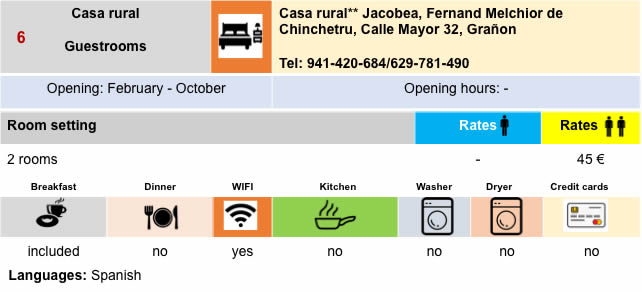

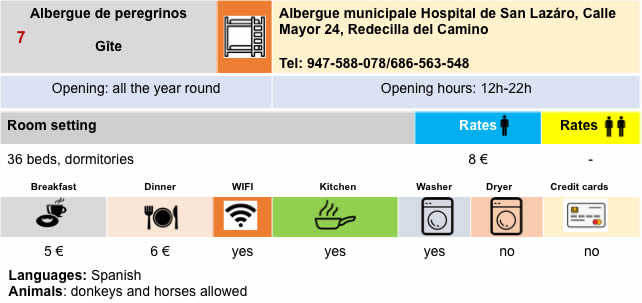

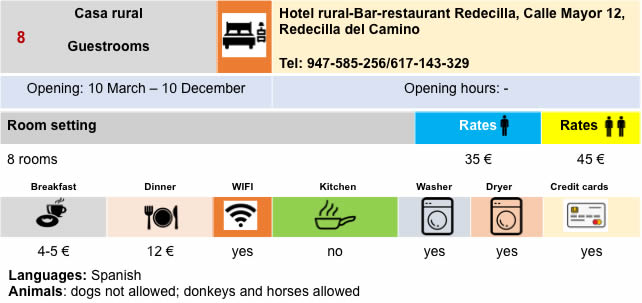

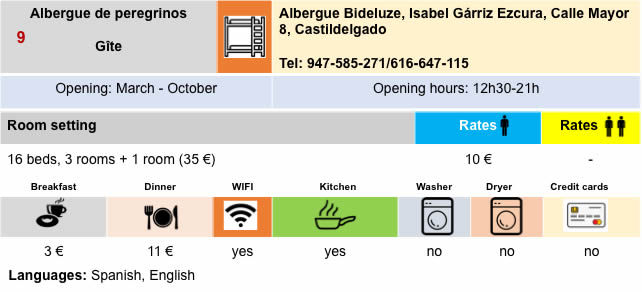

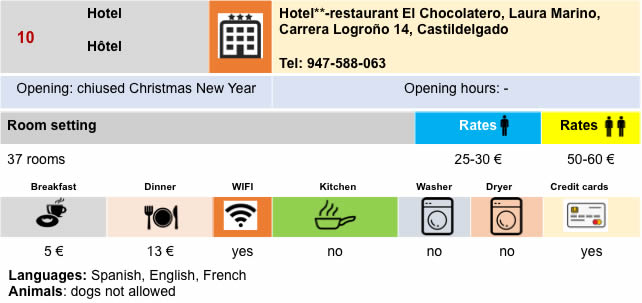

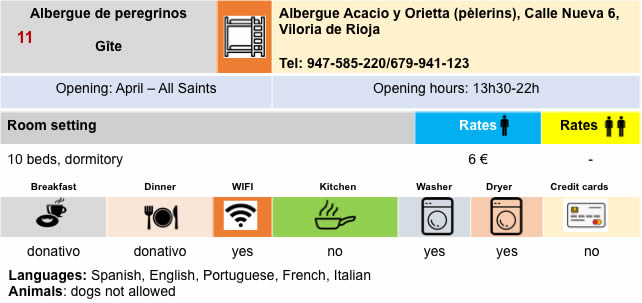

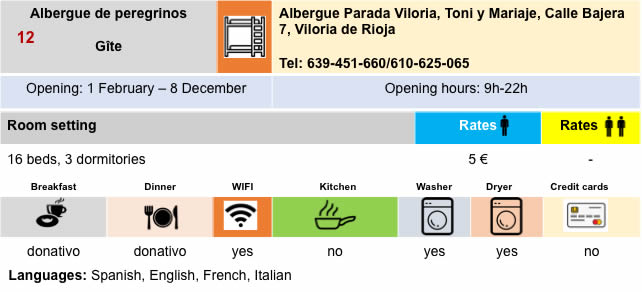

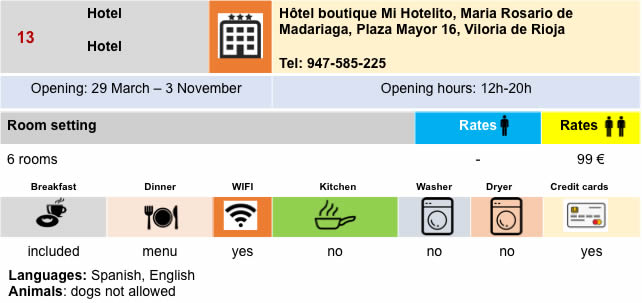

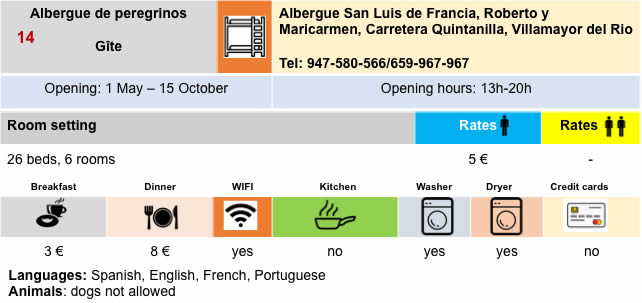

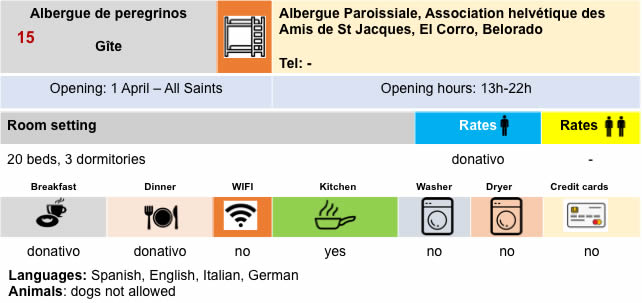

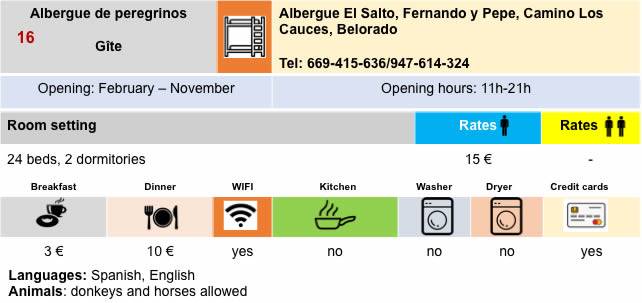

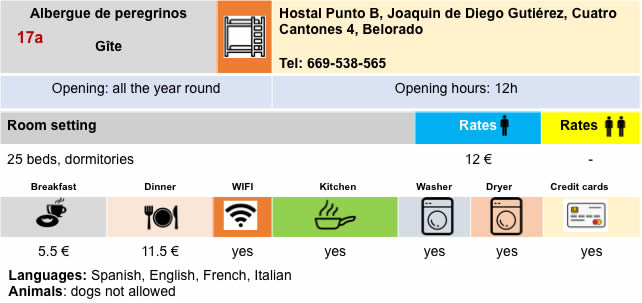

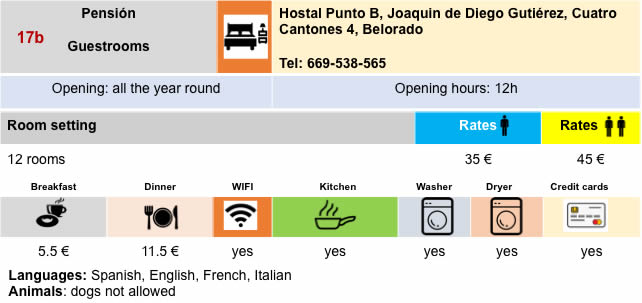

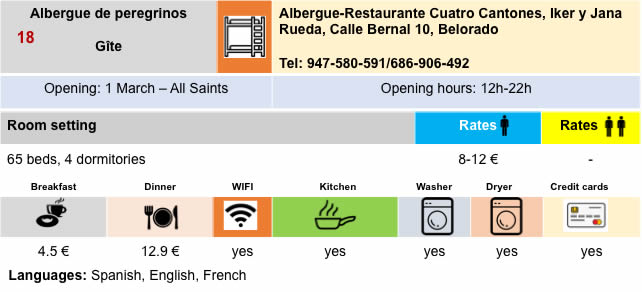

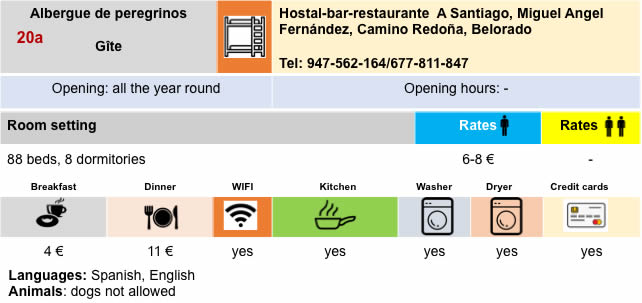

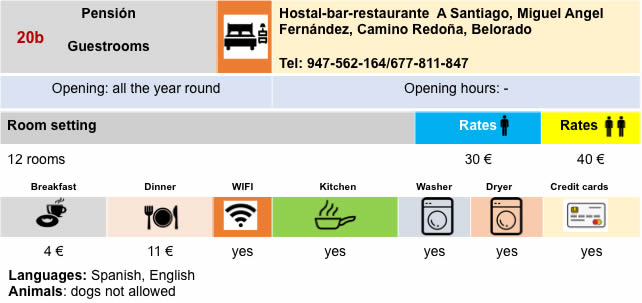

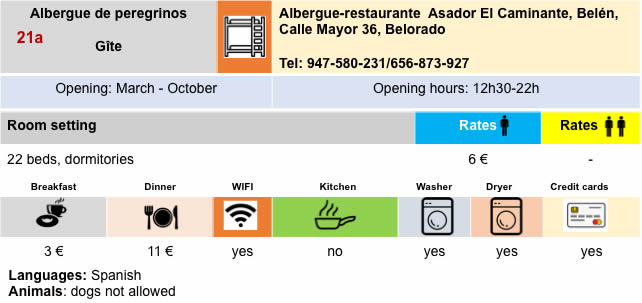

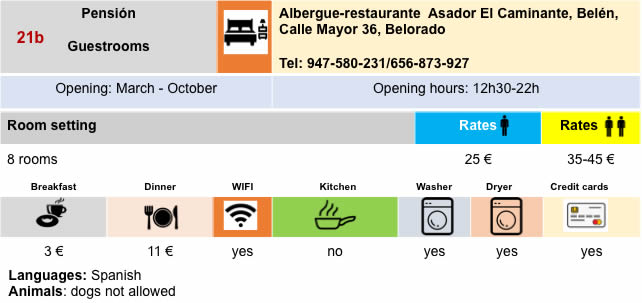

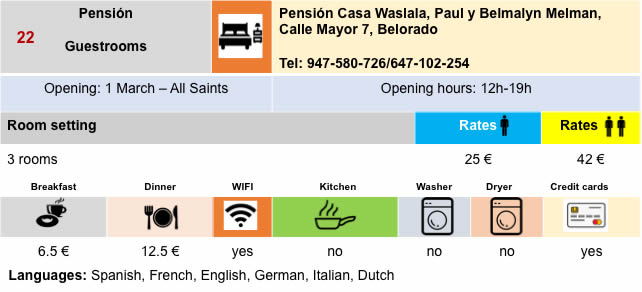

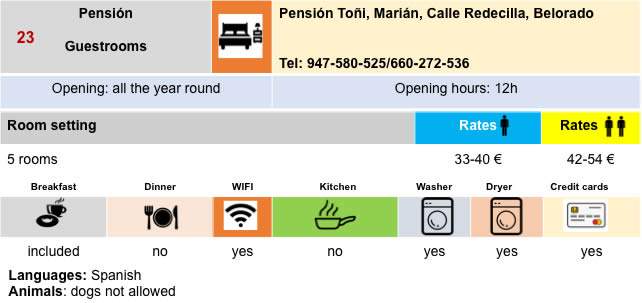

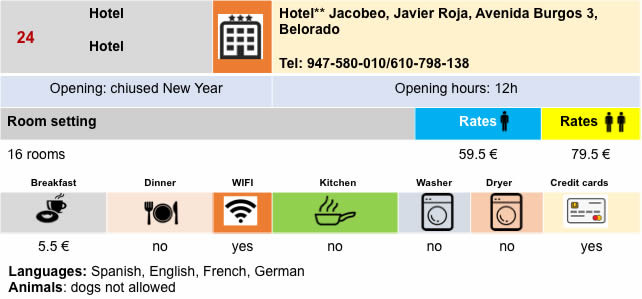

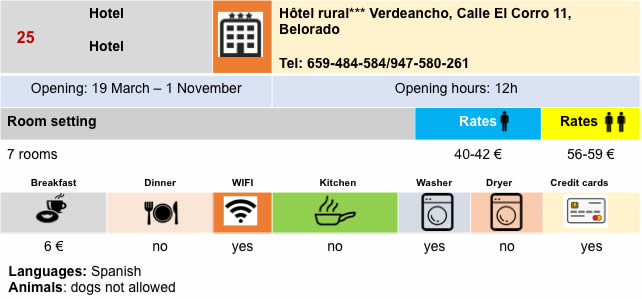

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 11: From Belorado to Atapuerca |

|

|

Back to menu |