In the vernacular heritage and the hórreos of Galicia

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

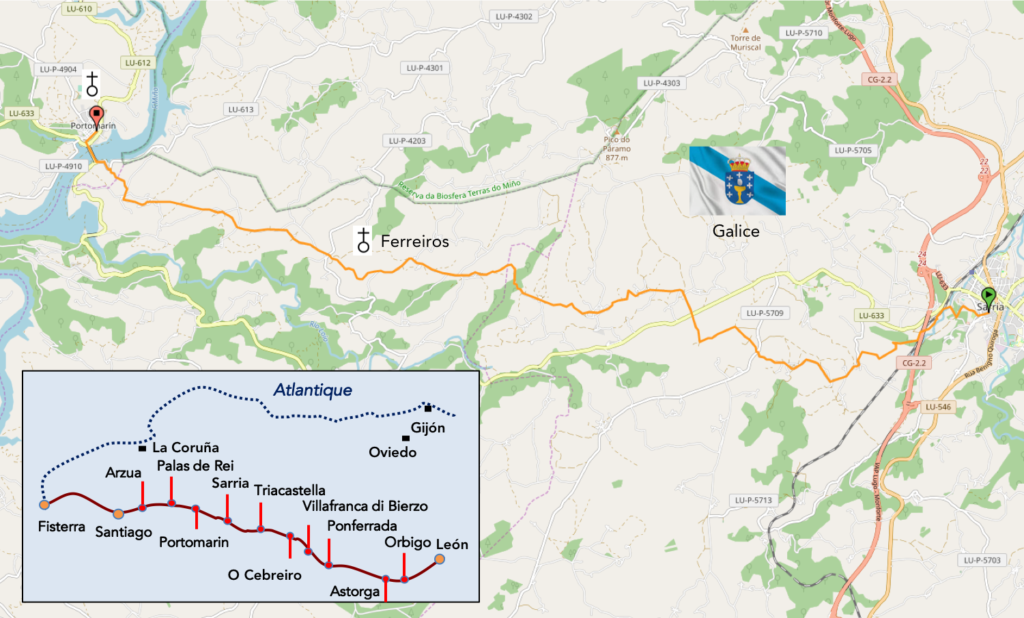

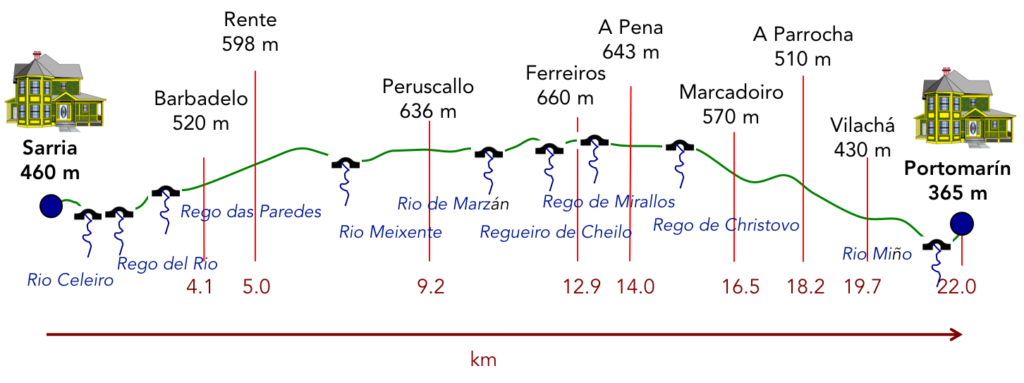

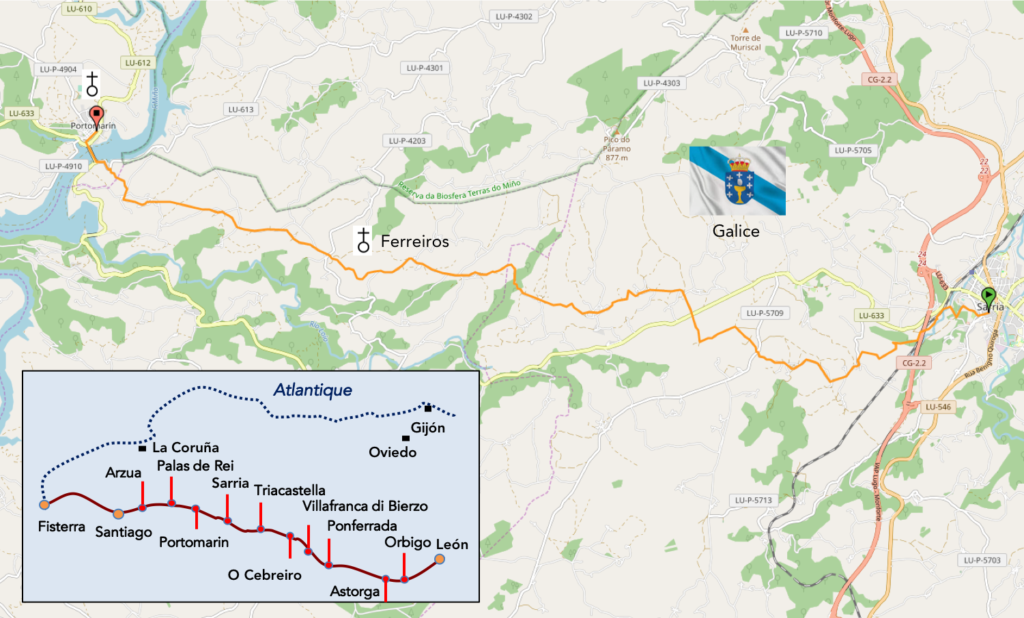

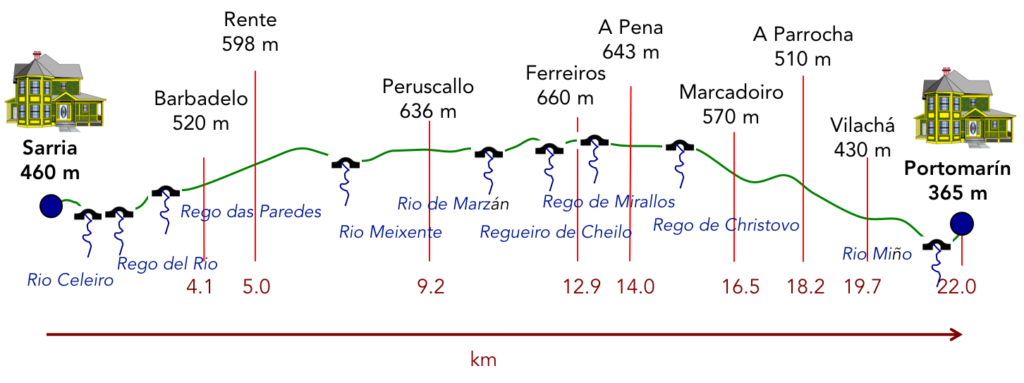

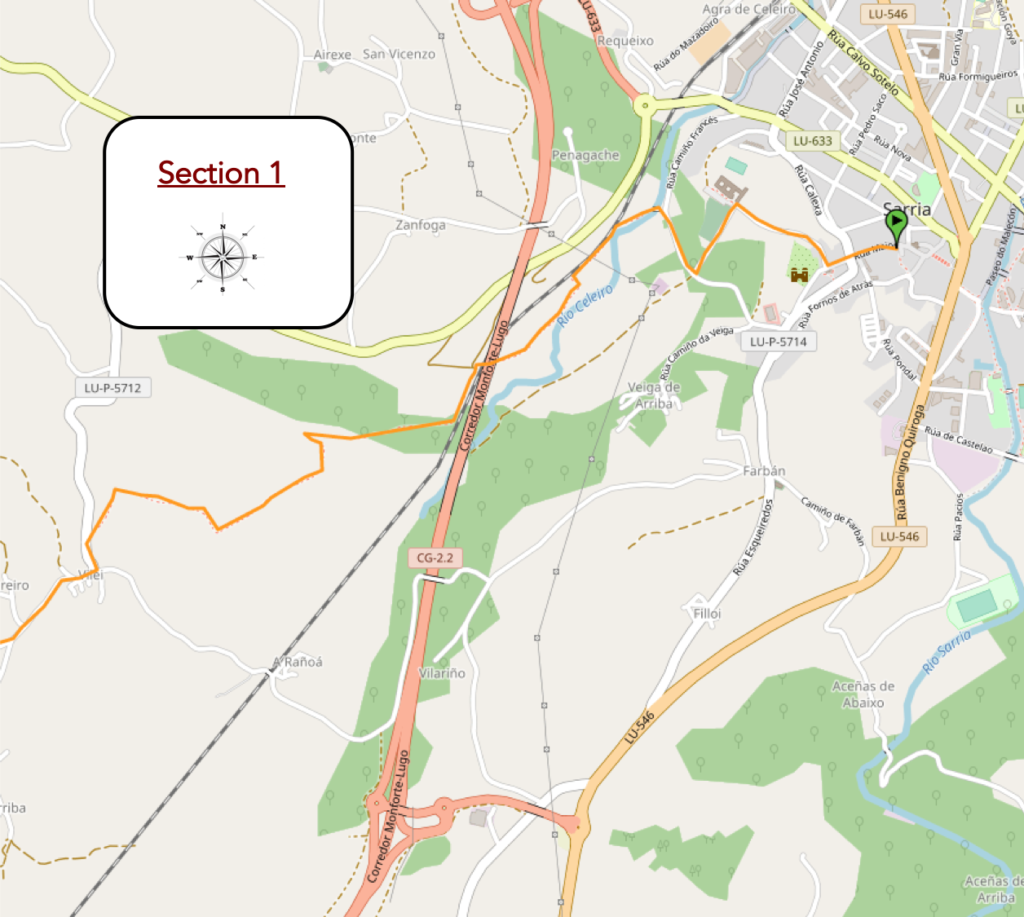

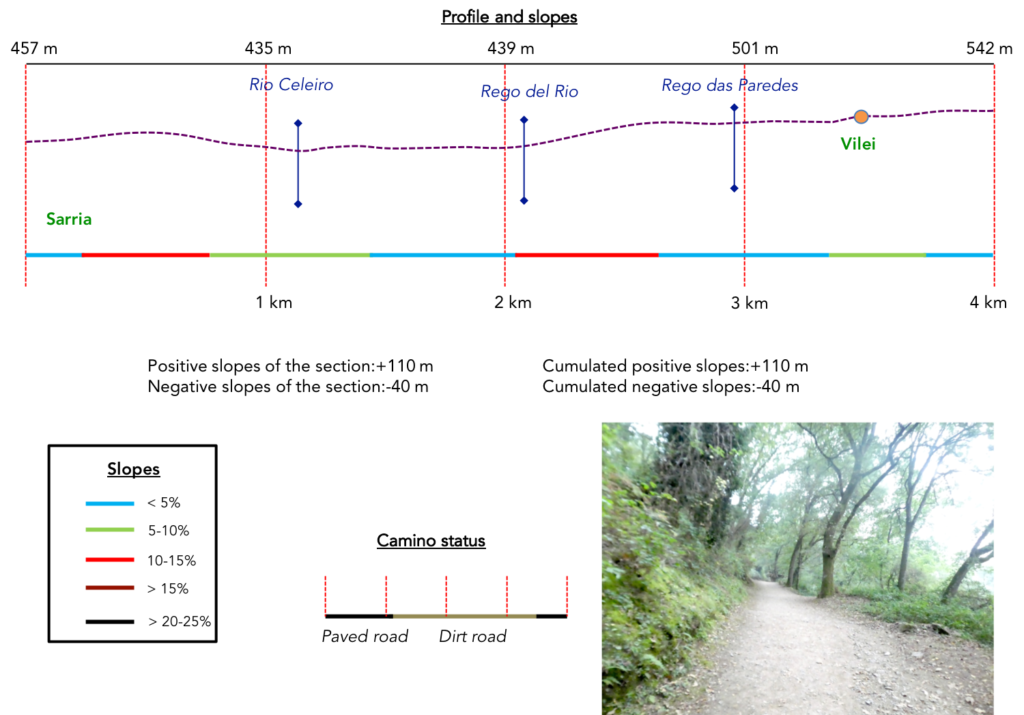

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-sarria-a-portomarin-par-le-camino-frances-43354761

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Galicia has its own language, Galician (gallego in Spanish or galego in Galician). It is the most western of the Roman languages, having separated from Latin at the beginning of the Middle Ages. During the Reconquista, in the XI and XIIth centuries, Galicia pushed south into what is now Portugal. Therefore, the southern dialect of Galician is Portuguese. Galician was considered the elegant court language of León until the XIIIth century. Signs in Galicia are most often in the Galician language rather than Castilian Spanish. The most notable spelling differences are that X replaces J, as in Perexe (Pereje) where you went uphill to O Cebreiro. The R replaces the L, as in praia (beach) or praza (place). And differences, there are many others. In the 1991 census, 91% of residents said they spoke Galego. Galego tends to be heard more in rural areas and among older people. But for the vast majority of non-Spanish pilgrims, their ear will not feel the difference between Galego and Castilian. And from Spanish they hear two words.

In today’s stage, the hórreos are flourishing. Hórreos are mainly found in northwestern Spain (Galicia and Asturias) and northern Portugal. There are two main types of hórreo: rectangular in shape, the most extensive, usually found in Galicia and the coastal areas of Asturias; and square-shaped hórreos from Asturias, León, western Cantabria and eastern Galicia. The Galician hórreo is a construction for agricultural use intended to dry and store corn, and even other cereals, before shelling and grinding them. It consists of a storage chamber, narrow and permeable to the passage of air, separated from the ground to prevent the entry of humidity or animals. Similar granaries were common throughout Europe. There are espigueiros or canastros in northern Portugal. French Savoy, Swiss Valais and Italian Val d’Aosta have attics for the same purpose, often called raccards. Norway has its stabbur and Sweden its häbre. Hambars are found in the Balkans and Turkey.

The origin of the term hórreo refers us to the Latin horreum, which designated a building in which the fruits of the fields, especially grain, were kept. In its beginnings, the use of hórreos in Galicia was linked to the cultivation of millet, which was already practiced in the culture of the Visigoth castros, a crop that lasted throughout the Middle Ages and was then replaced by corn when it arrived in Europe in the XVIIth century. Bread was the staple food of the people. In 1973 a decree was issued for the protection of all old granaries in Galicia and Asturias, which attempted to deal with the consequences of the abandonment of the rural way of life and the loss of use of the granaries. Some Galician granaries are considered historical monuments. The Galician-Portuguese type is essentially composed of a plinth, a chamber, a means of access and some ornamental and symbolic elements. The ornaments represent the power of the house or the protection of the deity.

Today Sarria is the starting point for an armada of pilgrims who begin their Camino, since there are only 5 days left and just over 100 km to Santiago, meeting the minimum requirement to receive a Compostela certificate. A large number come from South America or Central America. But not only. There are also many Americans and people from all continents. Pilgrims who have come from Eastern Europe, Germany, Switzerland or Italy and all the pilgrims who have crossed France before arriving here, have a rather negative idea of these « 100 kilometer tourists”, with their derisory bag. It is therefore what some call the “Tourist Camino”. And that’s true. Today’s stage is one of the most beautiful stages of the Camino francés, in often bewitching landscapes.

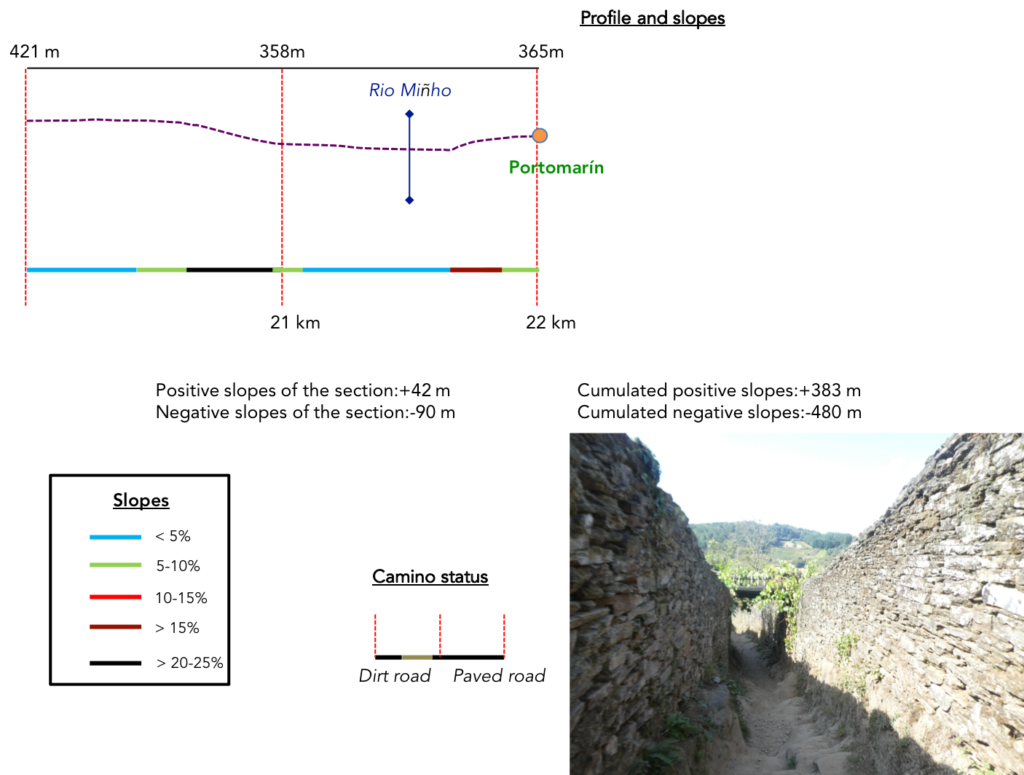

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the day (+383 m/-480 m) are quite pronounced for a Spanish stage, which crosses hills. The route climbs for the first 6 kilometers, often on fairly marked slopes. Then, there are permanent undulations, until the steep descent to Portomarín.

Today, passages on roads or on pathways are very equivalent:

- Paved roads: 11.5 km

- Dirt roads: 10.5 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

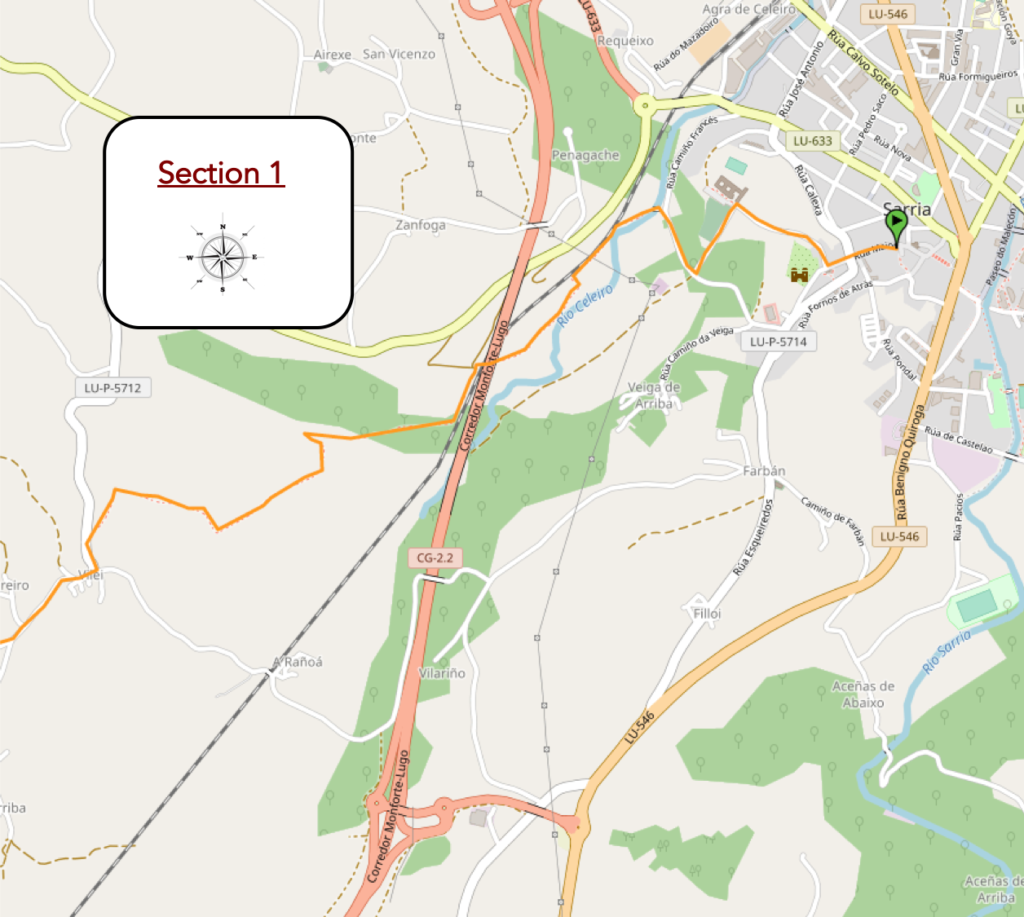

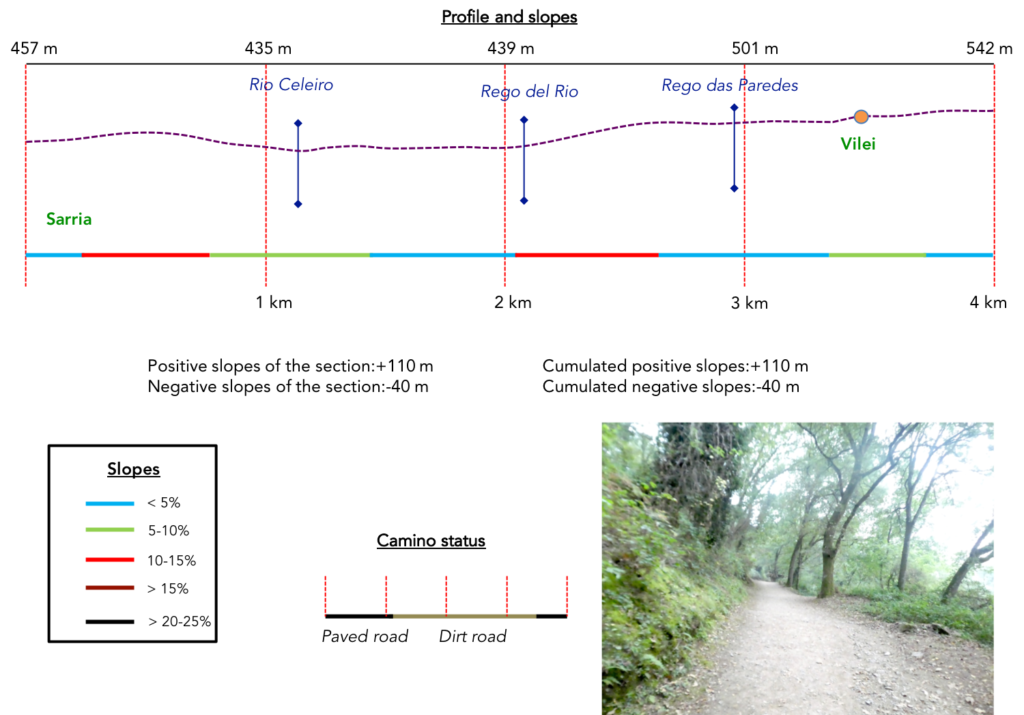

Section 1: In the forests of Sarria.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some steep slopes in the woods.

| The sky is a bit gray this morning over Sarria. Wherever you spent the night, you have to meet in the old town. The Camino starts from the top of Rua Mayor, at the level of the Tourist Office, the old preventive house. |

|

|

| It slopes up to the top of the street, where stands a cruceiro, with a Christ on the cross, which dominates the lower town. |

|

|

| Just below stands the convent of La Magdalena. It was founded as a hospital for pilgrims in the XIIIth century by the Order of Penance of the Blessed Martyrs of Christ, Italian monks under the rule of St. Augustine on their way to Santiago. In the XVIth century, the Magdalenos who had ruled the monastery for three centuries were incorporated into the Augustinian Order. The building was partly rebuilt in the XVIth century, mixing original Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque. The monastery remained under the protection of Italian monks until the XIXth century. After serving as a prison and barracks, the buildings were abandoned. Then it passed under the tutelage of the priests of the Mercedarian Order, who restored it and continued the traditional welcome of pilgrims. The hospital operated until the beginning of the XXth century. Today it is a private school run by the Mercedarian Order. |

|

|

| Beyond the convent, the road runs along the cemetery and descends into the undergrowth towards the river. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the Camino passes over the XIVth century medieval bridge, the Ponte Áspera (Rough Bridge), a magical bridge, the most famous of the bridges in Sarria. This bridge over the Celeiro River has three arches built in ashlar. The lustrous pavement must have seen hundreds of millions of pilgrims challenged over the centuries. |

|

|

| A narrow smooth pathway then flattens through the abundant vegetation towards a secondary railway line. Attention! Beyond Sarria, there is a high proportion of complementary routes. Here, follow the majority Camino that does not cross the track. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway gently follows the railway line. |

|

|

| It flattens gradually towards a long highway bridge. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway crosses the railway line under the motorway bridge. |

|

|

| It still flattens a few hundred meters… |

|

|

| …before crossing the tiny Rego del Rio stream and climbing steeply into the woods. |

|

|

| Here, chestnut trees and oaks share the wild hill. |

|

/td> /td> |

| The chestnut trees, probably several hundred years old, hunchbacked, twisted, tortured, seem to have taken upon themselves all the pain of the years. Their shredded stumps serve as branches. They don’t have much head left. |

|

|

| Further up, the oaks gradually take over and the forest dissipates. |

|

|

| The pathway then runs along stonewalls under the trees… |

|

|

| … and leads to a high plateau in the meadows. We have a feeling that the fog will perhaps dissipate. The Sarria region is renowned for its often-tenacious fog. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway skirts the hamlet of Vilei, along stonewalls covered with moss. |

|

|

| It is then a wide dirt road that winds gently through the meadows. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway gradually approaches Barbadelo. |

|

|

Section 2: Between countryside and undergrowth.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: sloping course at the start, then the holidays.

| The pathway does not take long to reach the village. |

|

|

| As is often the custom, many pilgrims have breakfast at the first village, as not all “albergues” serve breakfast. Here, the “albergue” has appropriated the village cruceiro, where a kitsch but votive fountain also flows. |

|

> |

| Barbadelo has existed since the Xth century. It was originally part of a large monastery, built in the late IXth century, which housed both nuns and monks, an arrangement of cohabitation which ceased to suit the power of Samos, which affiliated the monastery to the convent of Samos, and entrusted it only to men, with the aim of making it also a hospital for pilgrims. The Church of Santiago dates from the second half of the XIIth century and is mentioned in the Codex Calixtinus. It was built on the remains of the old monastery. The area is known locally as O Mosteiro in reference to the first monastery. The church that you see today is the only remaining building of the monastery. It is one of the best examples of Galician Romanesque art and was declared a Property of Cultural Interest (BIC) in 1980.

Because of the fog, and unaware of its location away from the village, we borrow some images from the Internet.. |

|

Wikipedia ; auteur : Jos Antonio Gil Martinez |

| Wikipedia ; auteur : Jos Antonio Gil Martinez |

Wikipedia ; auteur : Jos Antonio Gil Martinez |

| A square fortified tower at an angle dominates the church. The portals have carvings of weird and fantastic animal and human figures roughly carved into the granite. The church is closed, like most churches in the region. |

|

|

| Wikipedia ; auteur : Gerd Eichmann |

Wikipedia ; auteur : Gerd Eichmann |

| The Camino crosses the village. The innkeepers lure the customer here by offering stamps for their “credencial”. It’s a good war. It must be understood that the pilgrims who started the journey in Sarria have more of the passport than the pilgrims who come from further away. Many of them have come to fill the precious viaticum that will be co-signed in Santiago. It is claimed that the valuable document helps to improve the CV in South America. |

|

|

| A road leaves the village, and climbs in levels on the hill. The peasants planted large blocks of granite to make the fences for the cattle. |

|

|

| Advertising for accommodation or bars is displayed everywhere. The Camino francés is a real business beyond Sarria. |

|

|

| Unfortunately, the fog does not rise, drowning the landscape. It’s just that you can still see the big granite piles on the side of the road or the rare fruit trees. |

|

|

| Here two pilgrims, a Spaniard and an American, advance with their noses glued to the tar. Landscape, clear or blocked as today, they have nothing to do. What worries them is the independence of Catalonia for the Spanish, and the Civil War for the American. They will take kilometers to draw parallels. We understand, but still, come here to talk about it! |

|

|

| Further up, the Camino comes near Renfe. So, it momentarily leaves the road to reach the village by a dirt road. The mist that creeps into the oaks and the pilgrims who save themselves, that’s just beautiful poetry. |

|

|

| In the village, the high-stemmed cabbages rise clearly on their spurs. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the Camino leaves the hamlet on the road, on a variable slope, along oaks and chestnut trees, 109 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

| The old chestnut trees take on their lanky appearance here, which is often their charm. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope softens as you approach A Serra. You got to the top of the hill climb from the start in Sarria. |

|

|

There is in these rural landscapes, in the simplicity of the work in the fields, all the mystery of these numbed places where nature resonates in you like a sweet melody.

| Shortly after, the road arrives near the few houses of A Serra at the edge of a road. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses the paved road and goes behind the hamlet. |

|

|

| Then, quickly it is the return of the dirt under the big trees. |

|

|

| Further on, American GIs are on the attack. These people, you hear them coming from afar. |

|

|

They will not go for a dip in the swimming pool reserved for the use of pilgrims. Nor the other pilgrims for that matter. It’s definitely not a good day for swimming.

| The American cavalry fades little by little. Soon, all you can hear is a murmur carried by the wind. |

|

|

| These two pilgrims are calmer, more charged too. And all this nice little world of pilgrims parades on the dirt in what the Galicians call corredoiras, these pathways closed on the sides by stones covered with moss, under the venerable trees. Why all these barriers? Cattle are not often seen frolicking in the meadows. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway, soft so far, suddenly descends in a steady slope. There is a stream here, the Rio Meixente. |

|

|

| The Galicians call pasadoiros, these fordings of streams, on large aligned stones. In general, on the Camino, all the streams have an easy passage, which is not always the case with the other routes to Santiago. |

|

|

| The Camino takes a few more steps in the undergrowth before emerging into an emptier space. |

|

|

| It will then cross a secondary road. As usual, the organizers point out a road where the traffic is not overflowing. Here, the Camino road network is at work. This brave man tells us that he comes by several times a month to pick up the papers. There are incorrigible pilgrims. Yes!! |

|

|

| There, a road heads towards Peruscallo. |

|

|

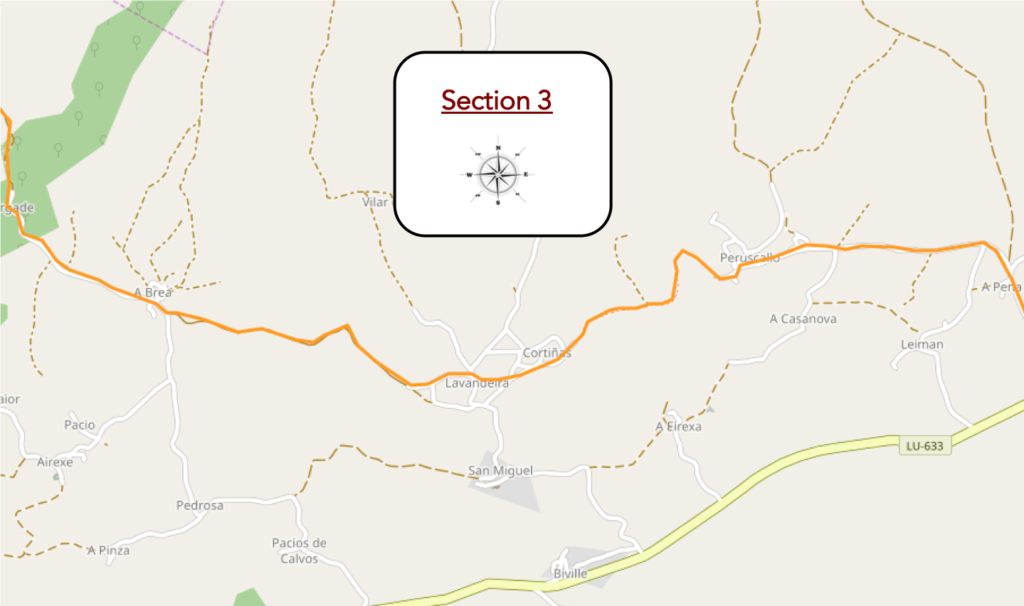

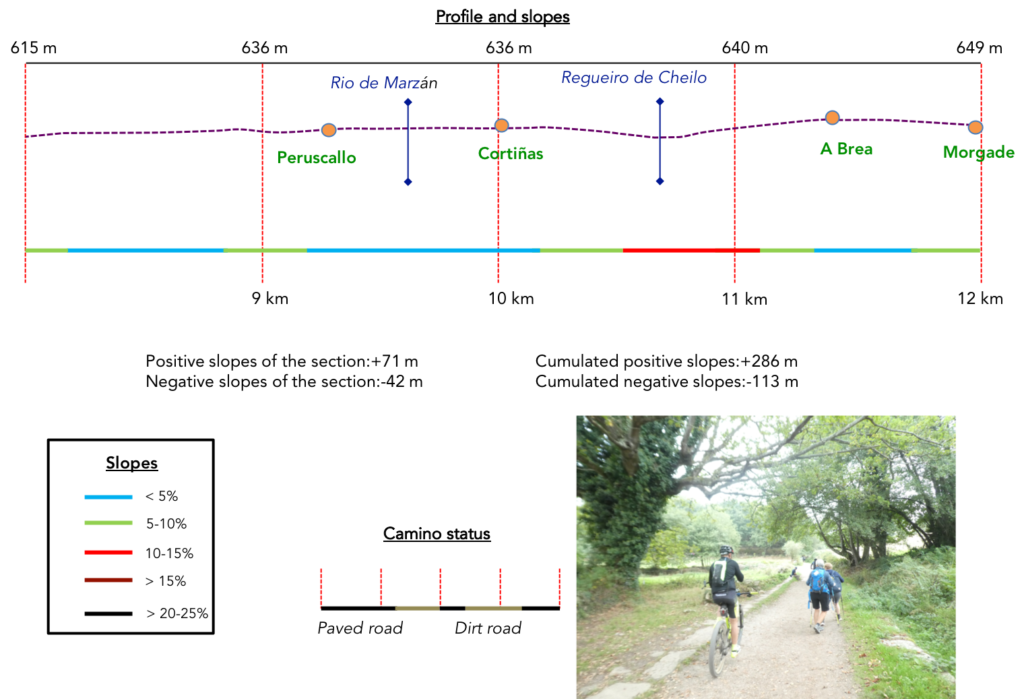

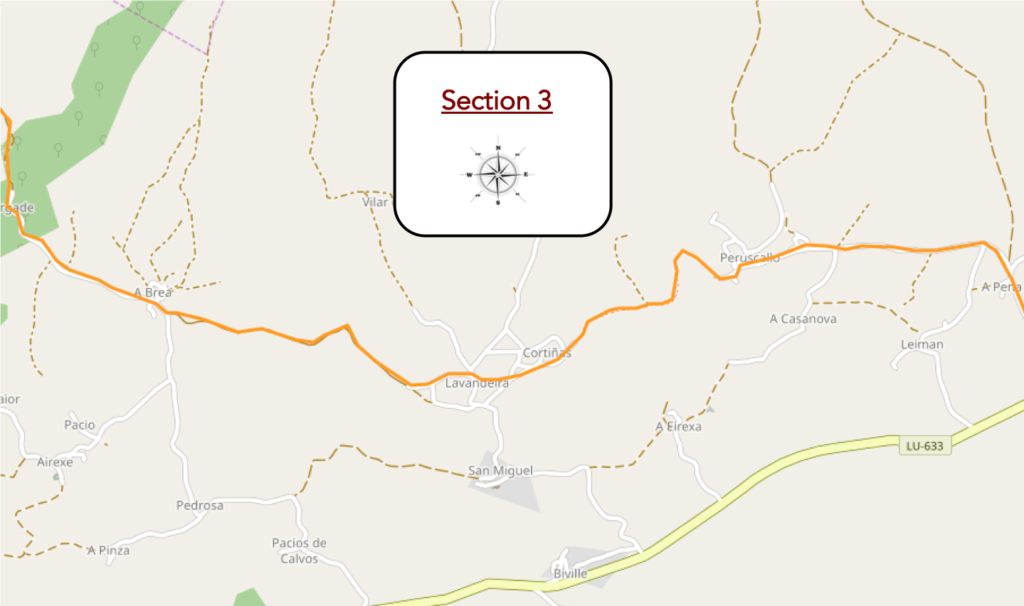

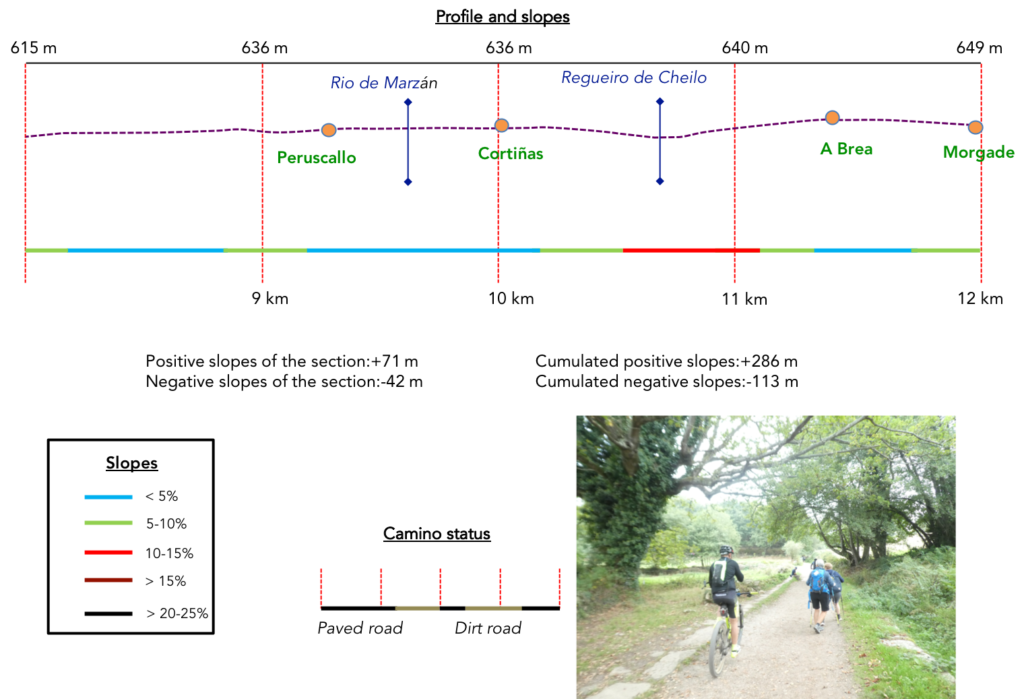

Section 3: From one village to another.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The road flattens in the countryside, of which you can guess scattered hamlets. You see rare fields that have known crops, but here it is mainly livestock, to see the extent of the meadows. |

|

|

| Further on, the road arrives at the first houses of the village. |

|

|

| Here, the road network is at work. It is a real organization, dependent on the Xunta (government) of Galicia, no doubt paid in part by Europe, to keep the Camino intact. These guys are so stylish that they turn off the brushcutter engine every time a pilgrim passes by. They have to turn off the engine often.

Shortly after, the road gets in Peruscallo. The village has no infrastructure for pilgrims, except, at the beginning of the village, a bar with a refrigerated cabinet. Pilgrims still stop there, because today there is hardly any place to eat on the route. |

|

|

| The village is quite large. Here grows corn, but it is rather the grass the livelihood of the farmers. |

|

|

This is the first hórreo on the course. This one is made of simple bricks.

| The road service has organized a whole commando here for the cleaning. The Camino soon leaves a village that does not breathe opulence. |

|

|

| Immediately beyond the village, a pathway descends to say hello to the Rio de Marzán. It is first a traditional corredoira, soon followed by a pasadoiro, to keep your feet dry, but today, the water does not flow aflot.. |

|

|

| Further on, on the corredoira, the line of pilgrims lengthens and marches. |

|

|

| There are sometimes cattle, and trees of extraordinary vigor. Who could estimate the age of this venerable oak tree? |

|

|

| Here, the Rubia galega cows take a siesta, when the pathway gets in Cortiñas, its rare and simple stone houses, so similar that you could have said they were built on the same day. |

|

|

| It is the same for the herréos who may have known the same architect. |

|

|

| The Camino goes around the hamlet, passes Lavanderia, which is continuous. Sometimes one has the feeling, to see certain pilgrims passing by, that they are on a war footing. |

|

|

| Beyond Lavanderia, the pathway slopes down gently towards the stream of Reguiero de Cheilo, through ferns, broom, small and large oaks. |

|

|

| Today, the creek is dry. So, how to justify this endless pasadoiro? You can easily imagine that in this basin, in strong rainy weather, you should not wade like frogs. |

|

|

| And besides, the slabs extend a good hundred meters, proof that the water must run off abundantly in rainy weather. Further on, the pathway slopes up from the basin on a stonier bottom, which poses less of a problem. |

|

|

| The slope here is steep and the vegetation almost Breton and island. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, the pathway runs through the hamlet of A Brea. |

|

|

| A small road leaves the hamlet and descends gently into the meadows. |

|

|

| There is great confusion regarding the exact mileage on the Camino francés and the veracity of the milestones. Some place the symbolic marker of 100 kilometers for Santiago here between A Brea and Morgade. We have seen many mistakes about this on the Camino, but it is understandable. On the one hand, these are new terminals. Formerly, they had another aspect. And then, the Camino could also sometimes change course. In fact, today the famous marker is located lower down, beyond the church of Ferreiros. But what does it really matter! Further down, the road joins the hamlet of Morgade. |

|

|

| There is often a buffet stop here at the refreshment bar. There is also the small chapel of Santa Mariña where pilgrims leave objects as a souvenir of their passage. |

|

|

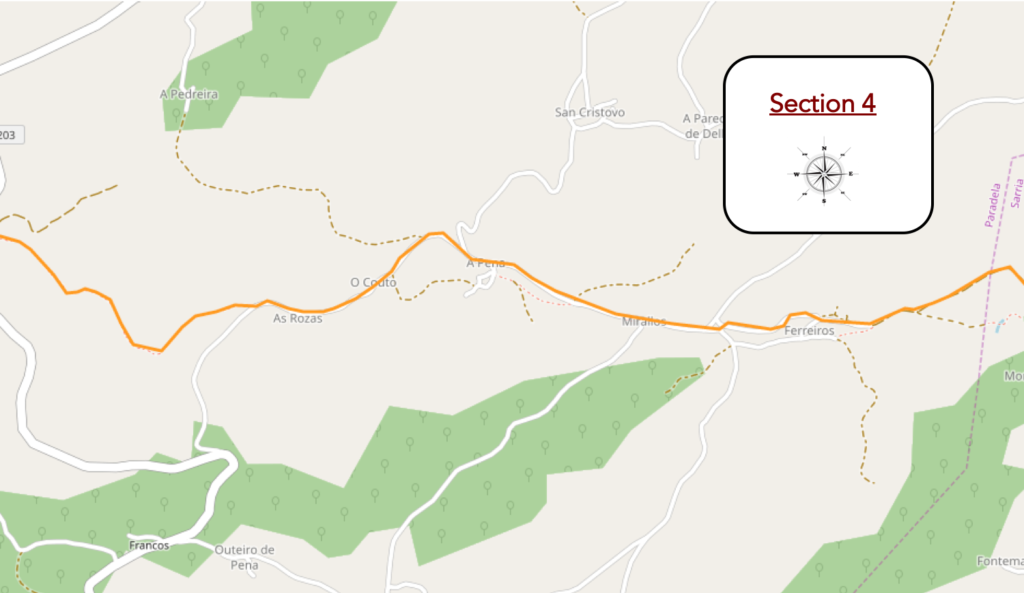

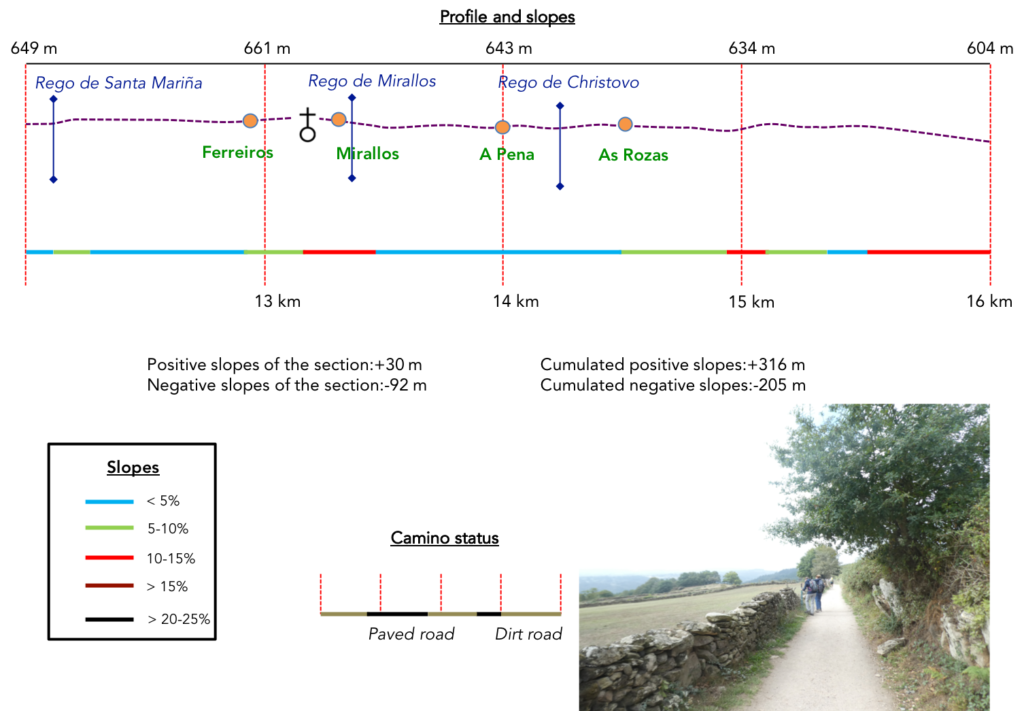

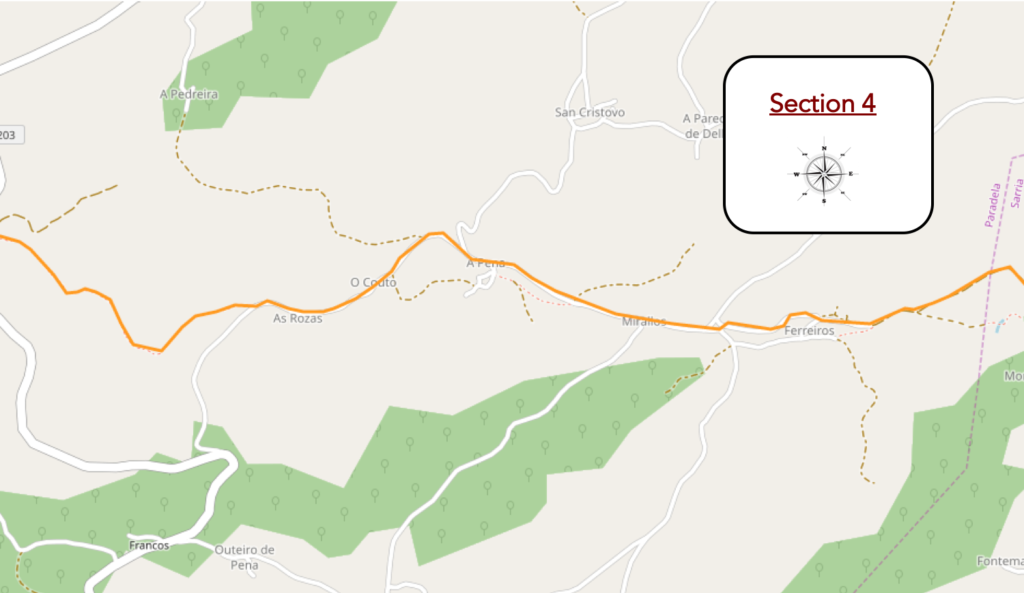

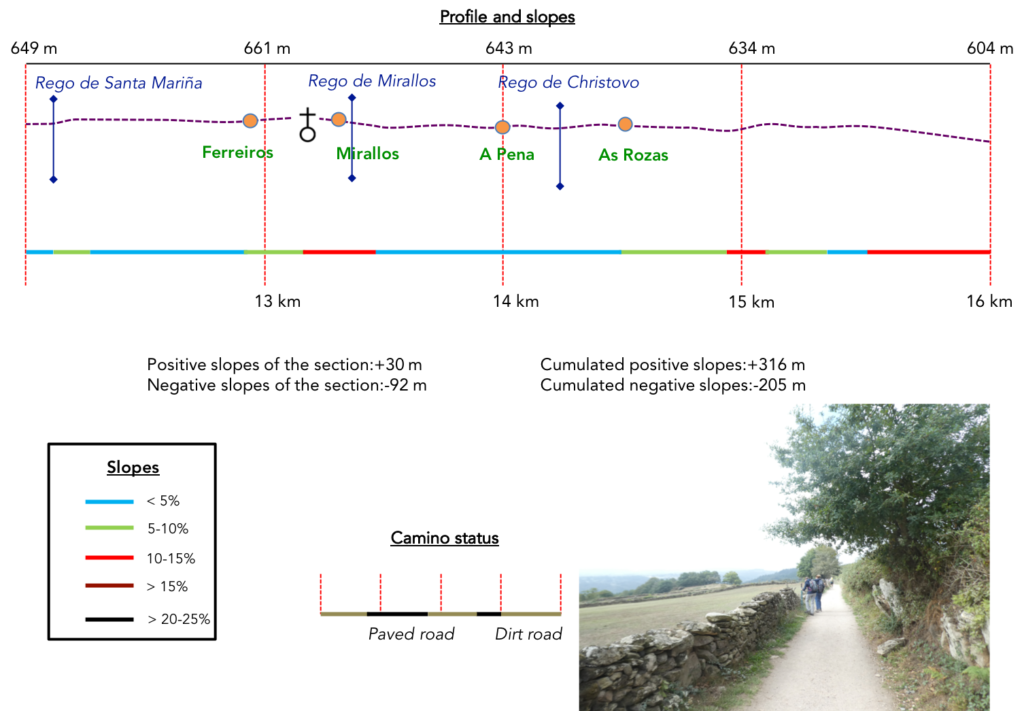

Section 4: The 100 symbolic kilometers.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course with slight bumps.

| Just below flows the Rego de Santa Mariña. So, it is again a pasadoiro to probably prevent water and mud in rainy weather. |

|

|

| And as often in this stage, pasadoiros and corredoiras alternate. Finally, today, the fog has lifted to give way to the sun. |

|

|

Like everywhere, Galician cows spend more time napping than working.

| Then, the pathway still caresses a few hundred meters these dry stonewalls, symbols of the Compostela tracks like beautiful postcards, transiting further above the gray houses of Ferreiros. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino follows a small road to reach the village. Ferreiros means blacksmiths. This village was born with the Camino. It was here that pilgrims could mend their shoes and also shoe their horses. |

|

|

| The Camino does not go to the village. It continues on the road towards Mirallos, where the church of Ferreiros stands. |

|

|

| The site is remarkable. The Church of Santa María de Ferreiros is a small church with a Romanesque facade originally built in the XIIth century on the site of an old monastery. There was also a hospital for pilgrims, but it has since disappeared. In 1790, people moved stone by stone the parish church of Santa María de Ferreiros to its current location, where it now functions as the cemetery chapel. |

|

|

| Beyond Mirallos, the Camino continues on the paved road, before finding a small section of pasadoiro, because here flows the Rego de Mirallos, which must not often be in water. |

|

|

| Further ahead, at the end of a slight descent, the pathway, smooth as a penny, gets in A Pena. |

|

|

This is where the symbolic marker of 100 kilometers that separates you from Santiago is located (official or not?). It is always a great moment of emotion for pilgrims who come from afar. Of course, the tourists of the Camino francés will not have the audacity to leave from here to fill their “credencial”. They leave all the same from Sarria, 14 kilometers before.

| A Pena est un village de pierre remarquable, avec un très bel hórreo en bois, vieilli par les siècles. |

|

|

| Beyond the village, it is a pathway that slopes downs in a delightful setting in the embankments and the low walls under the chestnut trees and the oaks. Such poetry, we want more. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway gives way to a paved road. Here, the density of pilgrims is great on the route. You have been told this elsewhere. There can be nearly 1,000 pilgrims a day beyond Sarria. From then on, it all depends on your schedule. It can be compact crowd or almost a desert. |

|

|

| Further on, the road runs through the hamlet of As Rozas. There is nothing for pilgrims here. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino leaves the road to find back one of these delicious corredoiras, which you never tire of. |

|

|

Can you find such a restful and charming haven to stop in the pines or, like the cows, to watch the pilgrims pass by?

| Walking and dreaming between these ageless stonewalls, in the shade of the trees, here is pleasure and fulfillment, for more than a kilometer. |

|

|

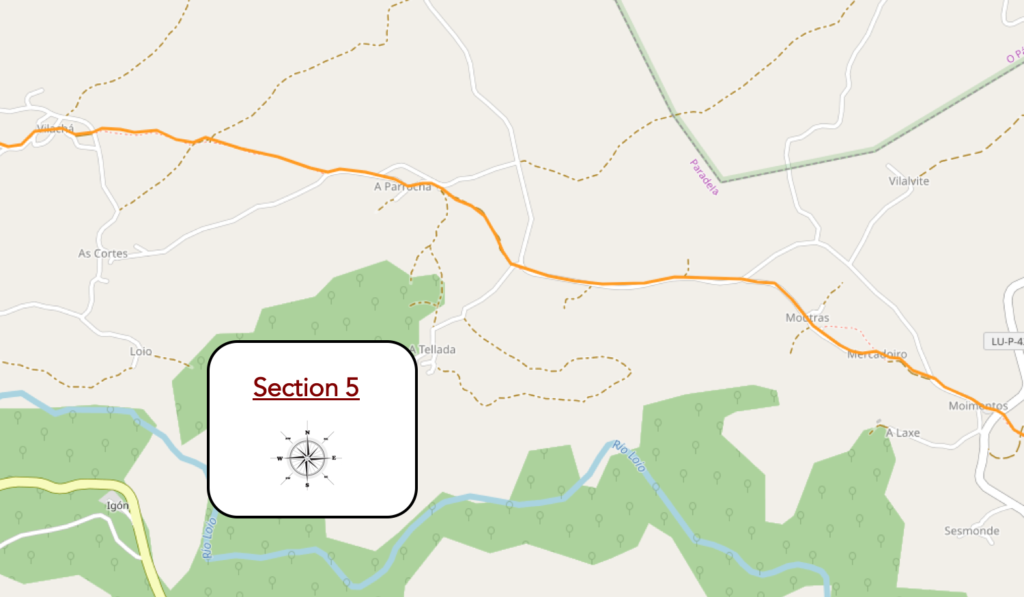

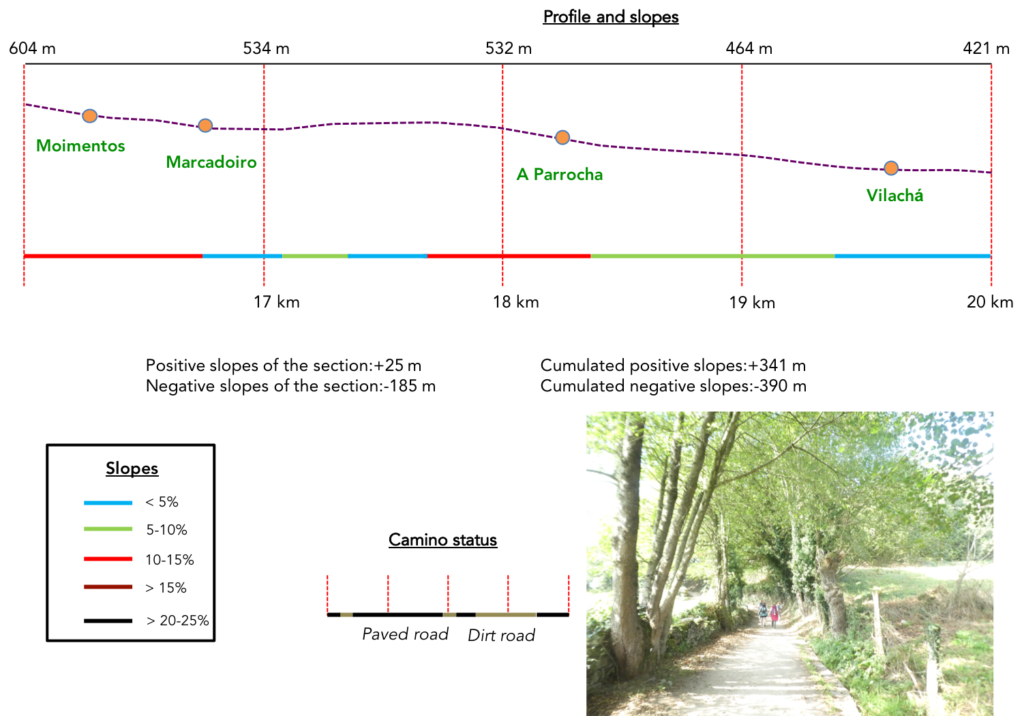

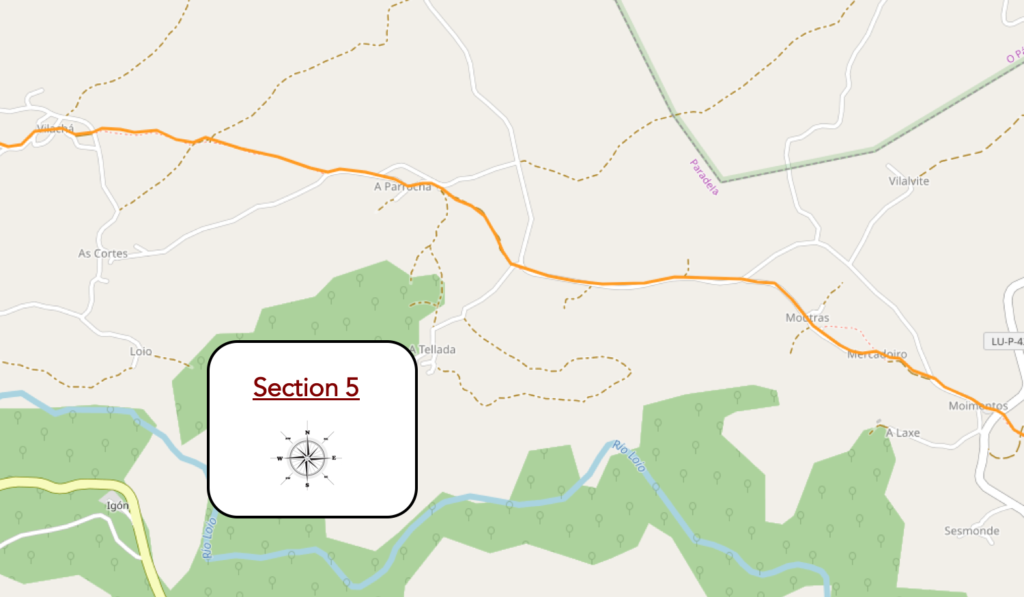

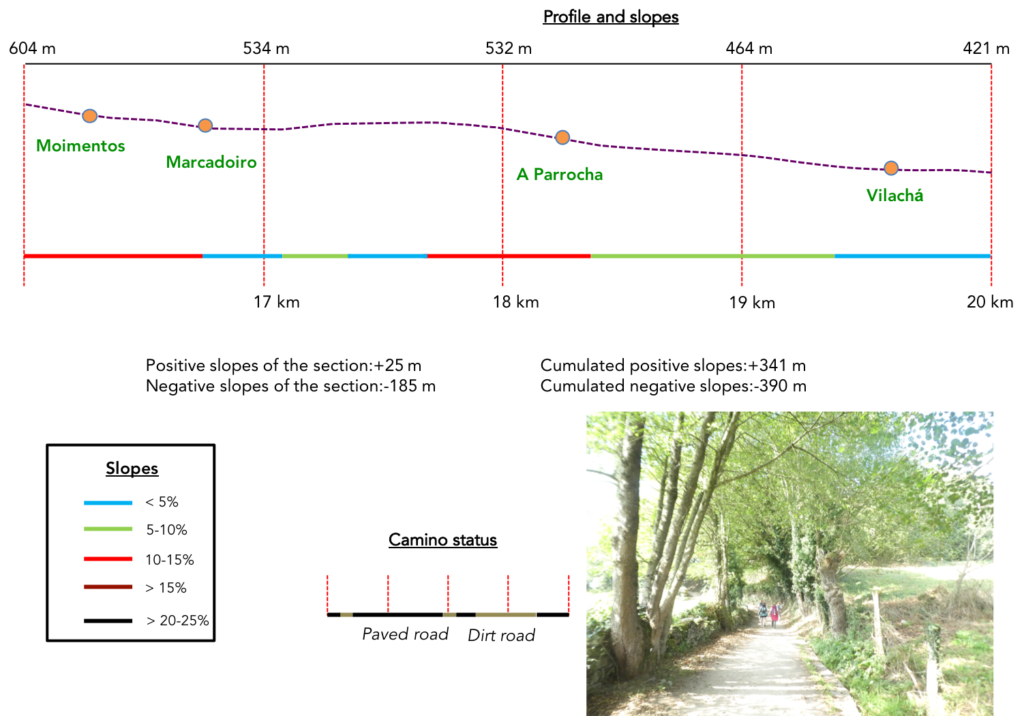

Section 5: From one village to another.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course with steeper slopes.

| A few more lengths in the woods, downhill, and the pathway joins a road below. |

|

|

| The road descends towards the hamlet of Mimentos. Here, there is nothing to serve the pilgrim either in a paved village, but sometimes with houses with rough stones, little masonry. On the other hand, there is the essential hórreo, here in bricks. |

|

|

| The road continues to descend from the hamlet and the line of pilgrims stretches out. |

|

|

| Shortly after, near a wooden cross, the Camino leaves the tarmac for a smooth dirt road that runs along some beautiful stone houses, where they also grow cabbage mounted on stilts. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the short descent, the pathway arrives in the fruit trees on the road at the entrance to Marcaidoro. |

|

|

| Here the antique wooden hórreo is still older than the old gentleman taking a break. |

|

|

Here is a symbolic monument that you will find if you have the courage to go to Fisterra, by the sea, after Santiago. Tied pairs of shoes, heterogeneous memories, as if to pray to Heaven.

| At the exit of the hamlet, the road flattens for a good kilometer in the pines. You will find that even though the organizers of the Camino have drawn a pathway by the side of the road, the pilgrims, for the most part, proceed on tarmac. Everyone according to their tastes, or rather according to their bad habit, right? |

|

|

| At the end of this long stretch where nothing happens except to take a look at the majesty of the pines, the Camino leaves the tarmac for a pathway that descends from the hill. |

|

|

| Here, the view extends over the valley of Portomarin. It is a royal driveway that slopes down moderately into the scattered oak trees to A Parrocha. |

|

|

| At the top of the village, there is a bar with a beautiful view of the plain, very often acclaimed by pilgrims. The village, where the old stones shine, is paved and sloping. What is amazing about the day’s route is the uniformity of the villages, with a very small number of modern housing estates, often quite common when compared to rough stone. |

|

|

| A moderately sloping road descends from the village into the countryside… |

|

|

| …before finding a dirt road further down. |

|

|

| You’ll find further down short undergrowth with its low walls under the oaks. |

|

|

| Then, the panorama opens more and more on the valley below. |

|

|

| Soon, the route arrives at Vilachá, the last village before the end of the stage, in Portomarín. |

|

> > |

| The village is consistent with the other villages encountered in the day’s stage, with however an infrastructure for pilgrims a little more present. |

|

|

Another brick hórreo, the last of the day.

| Beyond the village, the road follows the ridge… |

|

|

| …to arrive at a bifurcation that is very difficult to decipher. All the pilgrims who arrive here do not know which route to take. They go almost as far as tossing a coin. There are two routes shown here. Which one to choose? The indicated mileage is nonsense. But, one arrow is bigger than the other. So, choose the big arrow, which shows the direction of Portomarín that you see straight ahead. But, if you take the other, you will also arrive in Portomarín. You will see tomorrow, at the start of the stage, that all this is a subtle distinction between official and complementary routes. |

|

|

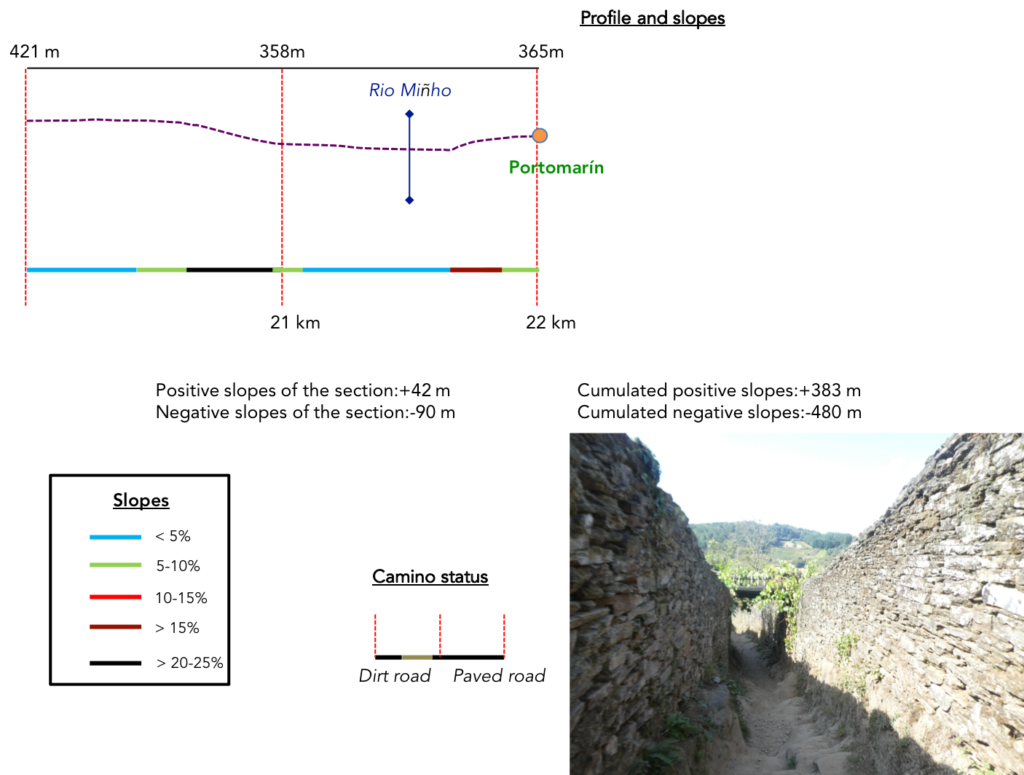

Section 5: On the Rio Miño side.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: marked and difficult slope to descend to the river and steep to climb to the village.

| Here, the road follows the ridge… |

|

|

| …until you find a narrow pathway at the corner of some houses. |

|

|

| The pathway still wanders a little on the ridge… |

|

|

| …but when you see the low walls appear, your life will change. |

|

|

| It’s a real gorge that awaits you on clay. You will dive between schist walls, sometimes with the impression of storming a fortress. In rainy weather, it must be busy around here. We cannot tell you if the other course is as delicate. When you pass here ask the bar further up the course. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway joins a road by the river. What a striking contrast! |

|

|

|

|

Then, Portomarín offers itself to you on the other side of the Rio Miño. (Rio Miñho, in Spanish)

The area around Portomarín has been inhabited for thousands of years. A bridge over the Río Miño, the largest river in Galicia, brought this area to life perhaps before Roman times. The Romans occupied it and named it Portumarini, suggesting that a bridge must have existed then. In the 2nd century, the Romans built a bridge over the river. The Roman bridge was 152 m long and 3.3 m wide. The Swabians and the Visigoths for their invasions used this bridge. In the IXth century, the Moors destroyed the bridge, which was later rebuilt. This medieval bridge would have remained intact until 1895, with the collapse of the central arch and the loss of structures, but this bridge functioned as well as possible, until the construction of a new bridge in 1929. Then, the place experienced a real tragedy. The current bridge is newer.

The village would have been founded in the Xth century. It is cited in the Codex Calixtinus as Pons Minéa. With the development of pilgrimage, its importance increased, as it was one of the very few bridges over the river. In the Middle Ages, there was a severe competition for power between the 3 orders of knights: the Templars, the Knights of Santiago and the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem. When the Order of Santiago was created at the end of the XIIth century, Portomarín was assigned to them. Then, the King of Galicia and León, Alfonso IX transferred its ownership to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, which managed several pilgrim hospitals here for centuries. Later, the village developed along both banks of the Miño. It was divided into two barrios, San Juan (formerly San Nicolás) and San Pedro, on either side of the river. On the left bank of the river were the Knights of Santiago and the Order of the Temple and on the right the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. San Juan was the main population center, located on the right bank. Both barrios had Romanesque churches of which that of San Juan was the most important. In the Middle Ages, the two districts together had around 1,200 inhabitants, like today.

| At the Mirador de San Pedro, pilgrims stop to take a photo of the bridge and the city up on the hill. |

|

|

| In the XIXth century, the rapid growth of the city of Lugo, 30 km to the north, and the development of a road network centered on Lugo cut off Portomarín from the commercial flow and the village began to wither away, being inaccessible. However, in 1931, the Romanesque church of San Juan (later San Nicolás) was declared a national monument. Then, in 1946, General Franco declared the place historic and artistic of special conservation. In 1950, the barrios of San Juan and San Pedro together had only 750 inhabitants, compared to 1,200 in the Middle Ages. But General Franco, who was Galician, spent many years improving the irrigation of northern Spain, such as the Meseta. So, in the interest of progress and prosperity, he decided to build a hydroelectric dam, 40 km upstream, to create the huge Embalse de Belesar reservoir, started in 1956 and completed in 1963. Unfortunately, the dam was going to flood fertile land and bury Portomarín under water. As the place had been declared a “historic village”, it had to be saved. The village therefore had to be moved to higher ground. The site chosen for the new village (Nuevo Portomarín) was on the nearby hill called Monte de Cristo. The move raised the village significantly above the reservoir’s maximum level. The streets of the new place were designed to reflect the characteristics of the past. After the construction of the reservoir, the population slowly recovered. Many years have passed since then, but those who lived through it remember it with sadness. Their homes were expropriated by the Franco administration and, although they were given a new home, there was no joy here. In fact, many preferred to take the money instead of a house and rebuild their lives elsewhere.

However, there are still remnants of earlier bridges. At the time of the flooding by the reservoir, a single arch of the Romano-Medieval bridge remained in the middle of the river; the arch on the buttress of the San Juan neighborhood was moved to Nuevo Portomarín. When the dam was completed in 1963, the waters of the dam filled the wide valley, so that the old Portomarín now lies under the waters of the reservoir. When the reservoir and river are low, usually in the fall, the ruins of the old village, with its houses, streets, mills, eel traps, and a pillar of the old Roman bridge, as well as the bridge built in 1929, can sometimes be seen emerging from the mud. |

|

|

| At the end of the bridge, the visit to Portomarín begins by climbing the steps of the Capilla de las Nieves (Chapel of the Snows). The Chapel of the Snows was the chapel of the former hospital of the Order of Saint John known as the Domus Dei, and the arch leading to it belongs to the old medieval bridge. Stone by stone, all the monumental heritage that existed down in the barrio of San Juan has been moved there. |

|

|

|

|

| If you follow the street that comes from Capilla de las Nieves, you will come across Rúa Compostela, which will take you to Plaza del Conde Fenosa. In this square you can see the Church of San Juan and the Pazo del Conde da Maza, seat of the city council. Inside is the Tourist Office.

The Church of San Nicolás, once the XIIth century Romanesque Church of San Pedro of the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, was dismantled stone by stone and moved up the hill to its current location. And so that there is not even the slightest mistake, they numbered the stones. You can still see a lot of numbers written on it. Apparently, it is only open during masses. The same was true of the facade of the Casa del Conde (count’s palace) from the XVIth century, which today serves as the town hall. However, the old pilgrims’ hospital and most of the medieval bridge remained buried under water. |

|

|

| The heart of the new village is the town hall square, and the many bars and restaurants under the arcades. It seems empty, but the pilgrims are still performing ablutions in their “albergue”! |

|

|

The Church of San Pedro is the other monument of the village, at the other end. This is all that remains of the barrio of San Pedro, at the other end of the bridge. This church was also moved from the old village before the Miño submerged it. Only its main facade remains. It was from the Xth century, older than the Church of San Juan. You cannot visit.

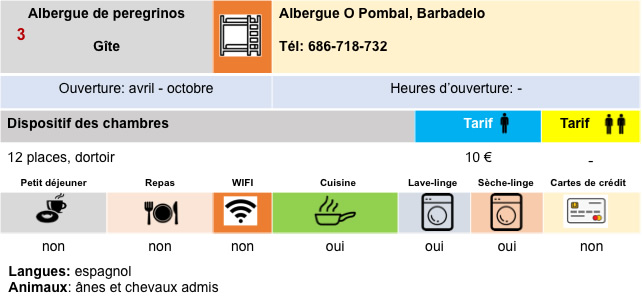

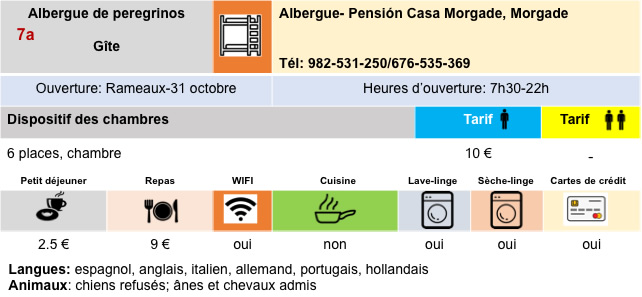

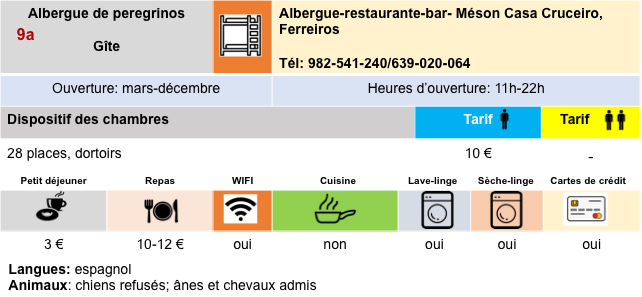

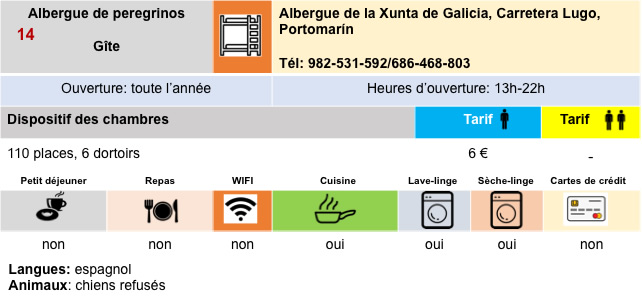

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 12: From Portomarín to Palas de Rei |

|

|

Back to menu |

/td>

/td>

>

>