The return of a quasi “Senda de los Peregrinos”

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-sarria-a-portomarin-par-le-camino-frances-43354761

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Galicia is a herd of one million cows that produce superb meat and delicious cheeses. Besides tapas, seafood is a particular delicacy. It is the land of pulpo a Galego (tender octopus), pulpo a feira (boiled or grilled octopus) and scallops are famous. Here, tasty fish or meat pies are called empenadas, usually stuffed with salt cod or tuna, but sometimes with shellfish or pork. The best Galician white wine is the white Albariño, fruity and full-bodied. The soils are mainly granitic, sometimes covered with clay, silt, sand or gravel. The soils are poor in organic matter, which gives wines with a lot of minerality. Rías Baixas is the most well-known appellation region in Galicia. In addition to Albariño, other white grape varieties sing in the glasses, such as Caíño Blanco, Godello or Torrontés. Galicia is claimed to be the land of Spanish white wine, but there are incredible red wines here that are not well known, and in every region.

For bred wines, the king grape variety is Mencía, the very one that grows in the vineyards of Villfranca del Bierzo that we crossed. It is the Ribeira Sacra appellation, located inland, which has the palm. Influenced by the oceanic and continental climate, on soils mainly composed of shale or granite, the vines plunge into the Sil and the Miño. Unfortunately, the Camino does not pass there but they are breathtaking landscapes, on steep hillsides that cannot be mechanized. In addition to Mencía, there are a good half-dozen red grape varieties unknown elsewhere, including Bastardo (Trousseau), which gives wines of incredible subtlety.

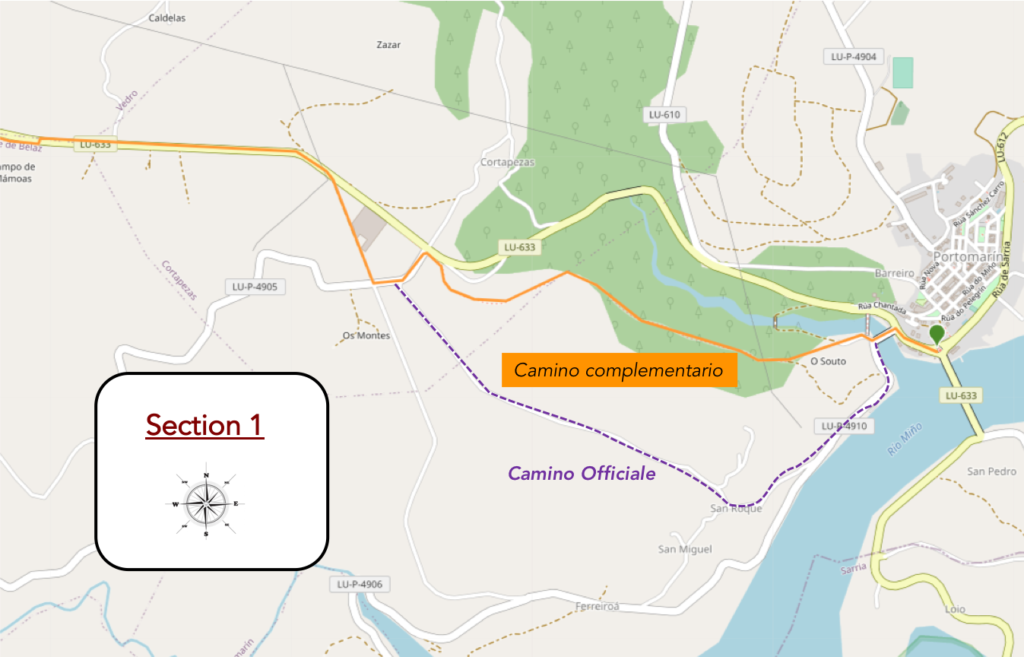

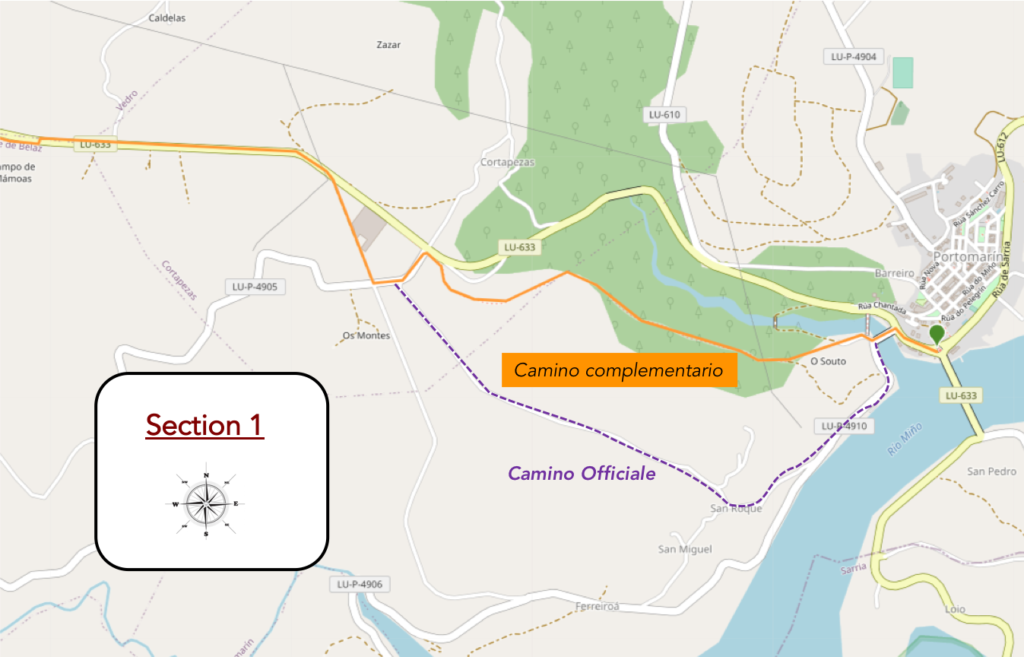

In some places, including here in Portomarín, the Camino is divided between the “official route”, with its markers marking the exact kilometers remaining to Santiago, and the “complementary route”, a route which also has its official markers, identical, but indicating no mileage but only the notation “Camino complementario”. Since the new pilgrimage milestones have been updated in Galicia, this is problematic and can be confusing. The interpretation is therefore complex, because often the pilgrim does not know what to choose. Above all, he doesn’t want to do any extra kilometers or get lost. The guides are very evasive about this. They will almost certainly introduce you to the “official course”. Why? It should be understood that in Spain the Camino is under government control, which however collaborates with many associations of the Ways of Compostela. For example, here, the Xunta de Galicia invests one million euros a year to improve the tracks and develop accommodation. Of course, they are also the ones who decide on the historical veracity of a journey. Don’t think they’re tossing a coin. They are also based on historical documents, when they exist. So, for them, the main road flows almost entirely through the traditional track, heir, it is believed, of the old medieval track. The variants allow the pilgrim to access significant places, lost pathways whose traces are still preserved. However, several points must be understood. First, nothing precise and definite is known about the original track. Second, there is economic policy there. Accommodation has developed where pilgrims go first. If you decide on a “complementary route”, find out before setting off on the stage. But you don’t always know that in advance. So, if you want to do it, know that you won’t get lost.

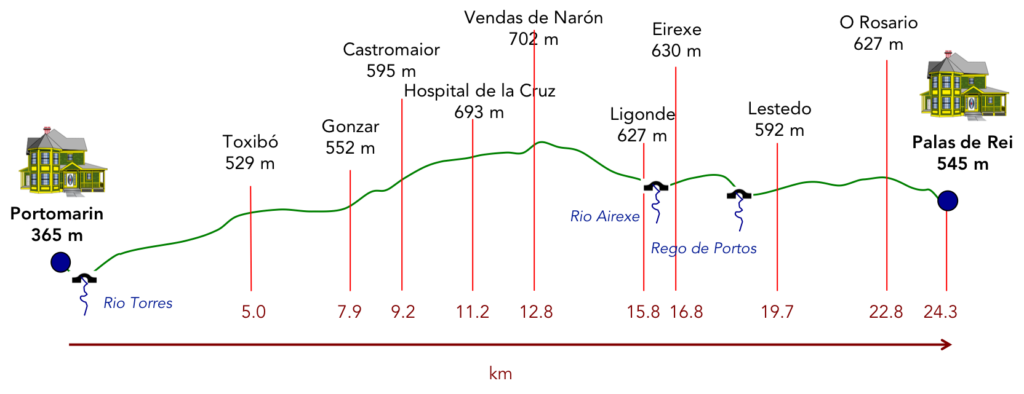

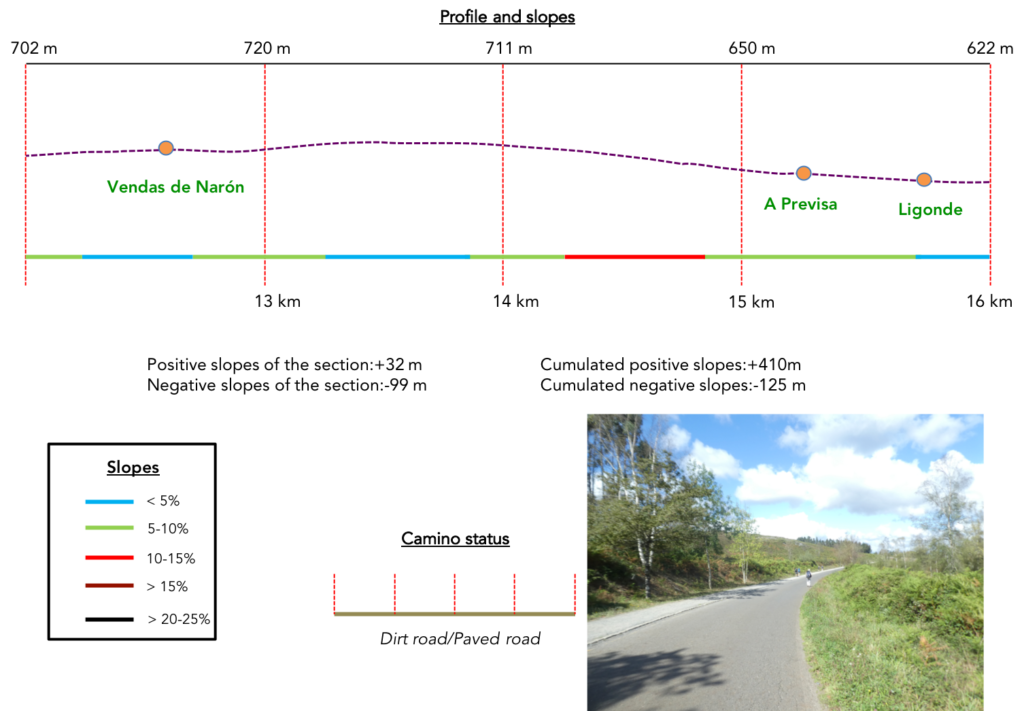

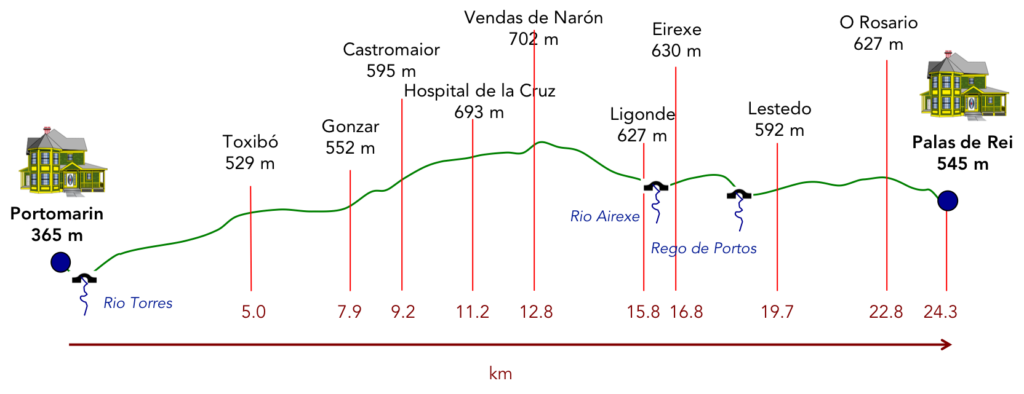

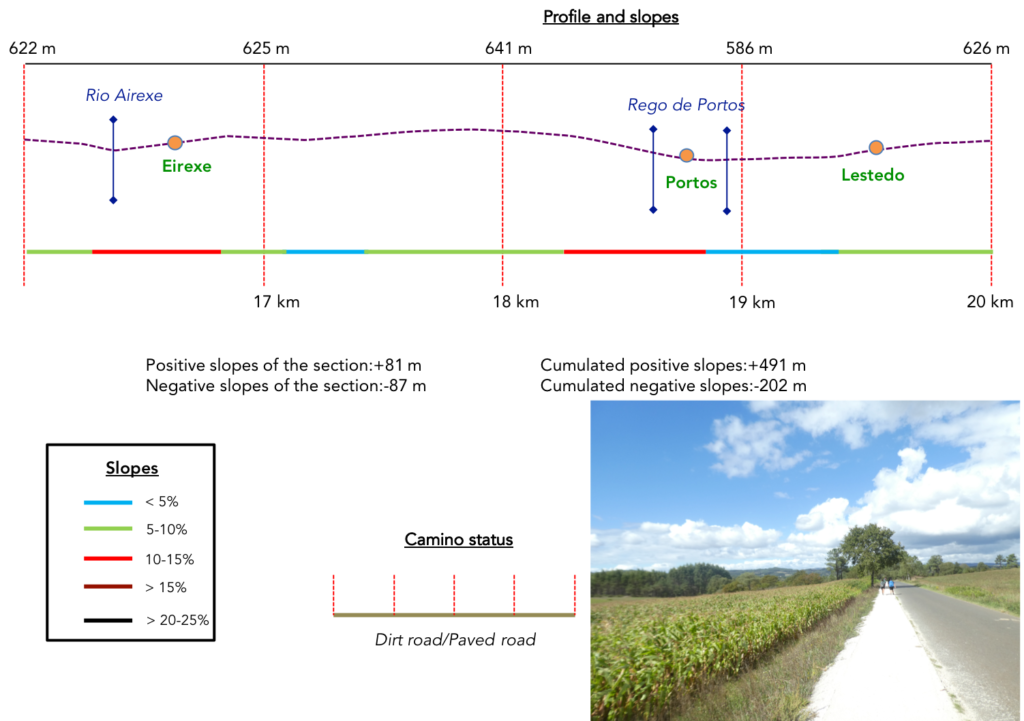

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the day (+383 m/-480 m) are quite pronounced for a Spanish stage, which crosses hills. The route climbs for the first 6 kilometers, often on fairly marked slopes. Then, there are permanent undulations, until the steep descent to Portomarín.

In today’s stage, the pathways are clearly to the walker’s advantage. Finally, it is a way of saying, because most often, the track is only a quasi “senda de los Peregrinos”, or rather a simple dirt or gravel alley not separated from the road:

- Paved roads: 2.8 km

- Dirt roads: 21.5 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

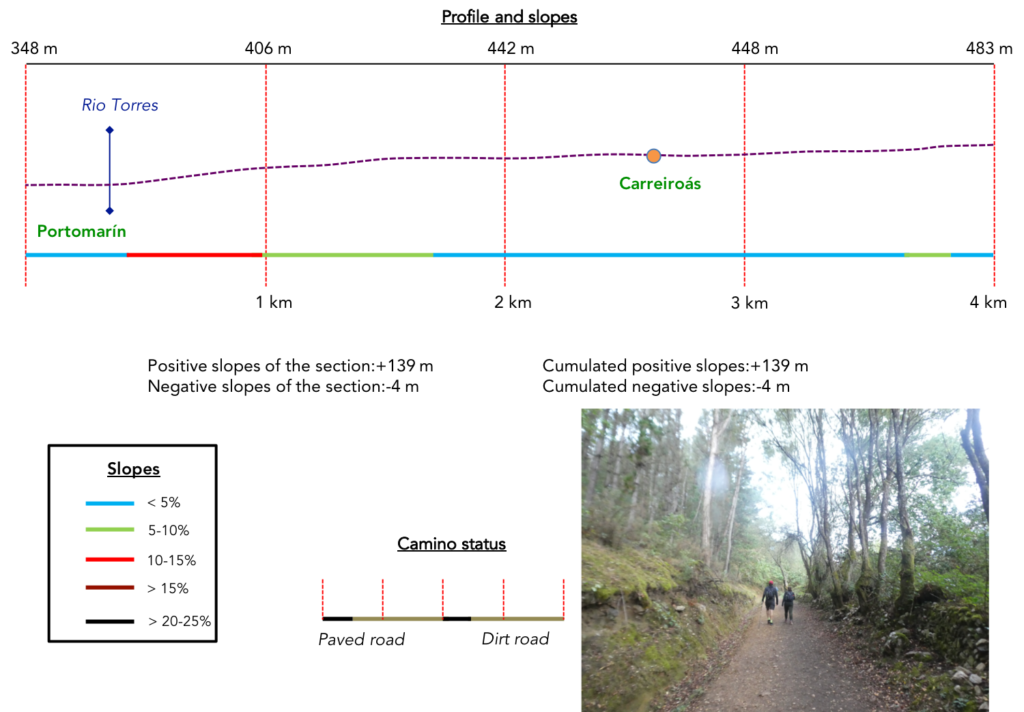

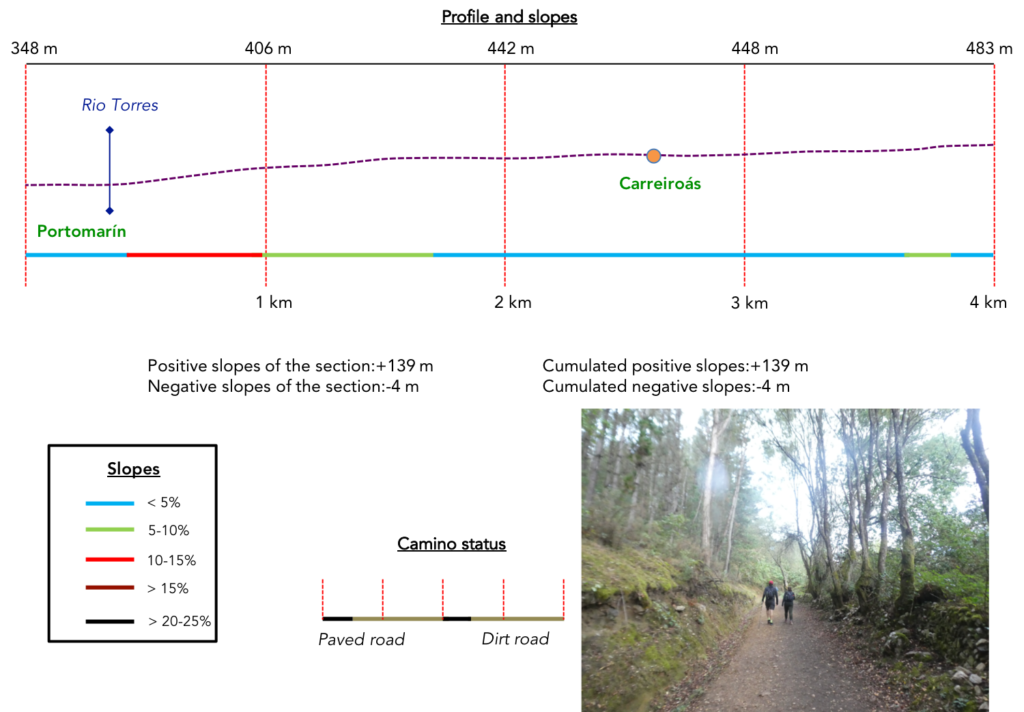

Section 1: In the forest before finding a new “Senda de los Peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: route often with very steep slopes.

| The Camino descends from the village to find the staircase that leads to the Capilla de las Nieves. The Camino runs to the right on the provincial road. This morning, the weather is still gray. But there is less fog than the day before, in an area where fog likes to hang around in the fall |

|

|

| Quickly, the route leaves the main road to cross the Rio Torres, which here joins the Rio Miño, with low water at this time. There is also a metal footbridge, possibly closed, to cross the river. |

|

|

At the end of the bridge, here is the choice: the “Official Camino” or the “Camino complementario”. You notice that only the official route is marked with kilometers. The other no. We stood there for a few minutes questioningly, as there was a large group of pilgrims behind us, to see what their chosen object would be. They took the “Camino complementario”. They had been advised at the Tourist Office to do so.

This complementary route, also traced by the Xunta, is much shorter, more beautiful, while the original route is longer by nearly 1 kilometer, often on the road. But then, why does the Xunta want pilgrims to pass through San Roque, the official and historic route? Precisely, because it is historic and there is a church, probably closed. It has swarmed here in recent years with peasants, unhappy that pilgrims pass through San Roque, which disturbs the cows. Some locals have even dug up the official milestone. When we passed, there were the two terminals. Before or after the uprooting of the bollard, who knows? We have not investigated this. All this history repeats again the problems posed for the organizers of treacks. We have seen the same problem in France. So, you will see, in your turn, passing here, which route will be preferred, if there are still two, or if there is only one track? / Be that as it may, today the pilgrims, at least the vast majority, walk to the right, along the Rio Torres, on the “Camino complementario”.

Quoi qu’il en soit, aujourd’hui, les pèlerins, du moins la très grande majorité, partent à droite, le long du Rio Torres, sur le “Camino complementario”.

| The Camino follows the tarmac for a short time, before reaching a dead end where it finds a pathway that climbs through the woods. |

|

|

| The pathway, a mixture of dirt and old tar, climbs at less than 15% in the oaks. |

|

|

| Sometimes, in a clearing, you see that the pathway runs parallel to the LU-633, the departmental road with which you will have a bit of conversation today. |

|

|

| Pilgrims parade like beads in the lush vegetation. Some are already struggling. Beyond Sarria, there are not only great athletes on the course. Here, the chestnut trees play in vain to compete with the oaks. |

|

|

| The higher you walk, the more the pines creep. Fortunately, today, the fog has dissipated. And the day will be beautiful. |

|

|

| Further up, the forest thins out, and the ground takes on an ocher hue. You then come out of the woods of Monte San Antonio, which, according to the Codex Calixtinus, was at the time a real open-air brothel. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the slope softens and the road becomes royal in the rows of pines. |

|

|

| The pathway then alternates on a gentle slope between the pines and the oaks, in the bushes and the large broom. |

|

|

| Soon, the pathway joins the departmental road. |

|

|

| You will then find that you are walking well on the “Camino complementario”, where a road descends towards the San Roque church, on the “Official Camino”. You have gained a kilometer and you have not walked on the road. |

|

|

| Here, the Camino makes a very small detour to momentarily avoid the road, where the two variants meet. |

|

|

| It then runs along the few houses of Carreiroás, including a factory where bricks are made. Palas33 |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino crosses the road, to engage again on a “Senda de los Peregrinos” which you guess is endless. |

|

|

| Here we have the feeling that cyclists have increased in number. And all around this heterogeneous little world of walkers, motorized or not, parades under the pines. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway runs in front of a place called Campo de Momoas. Here, have people unearthed some bones from prehistory? A mamoa, in Galician or Portuguese, is a tumulus, namely an artificial mound that covers a dolmen chamber. It can be made of dirt, clad in a cuirass of small interlocking stones, or be made of stones only. |

|

|

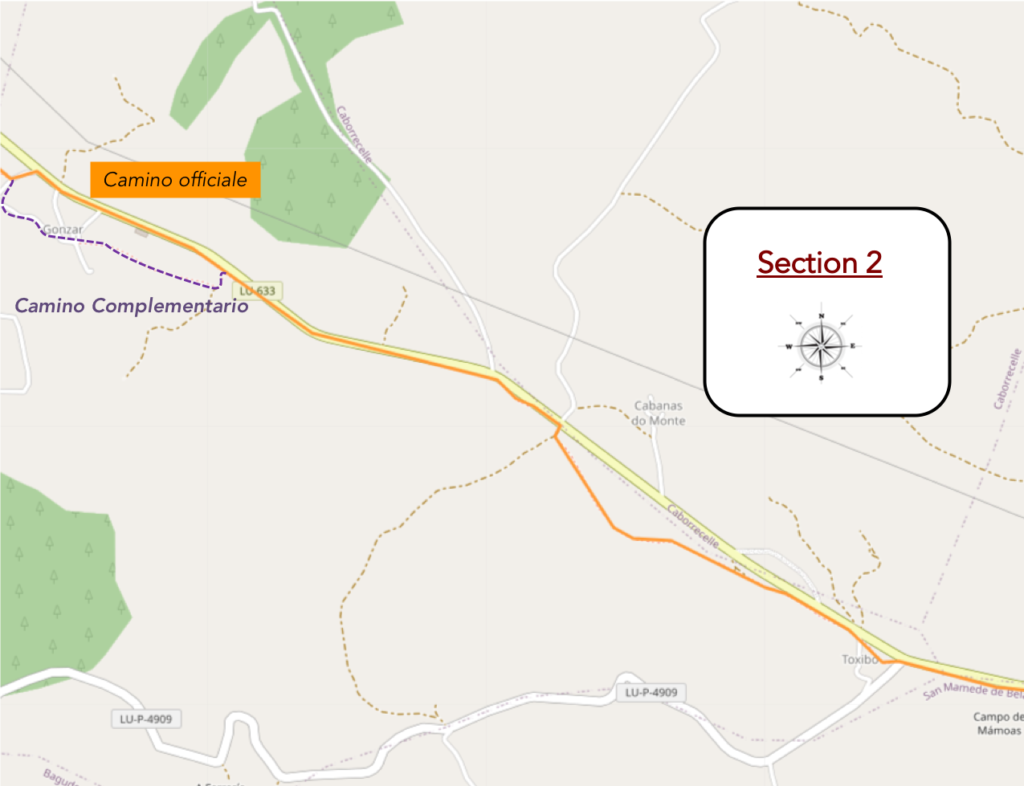

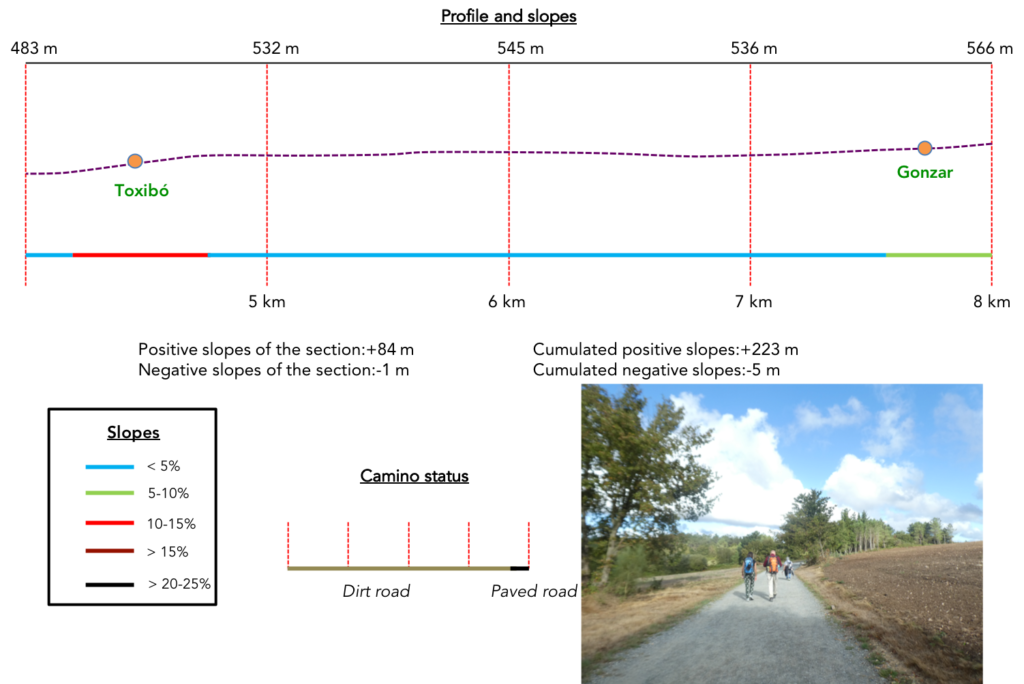

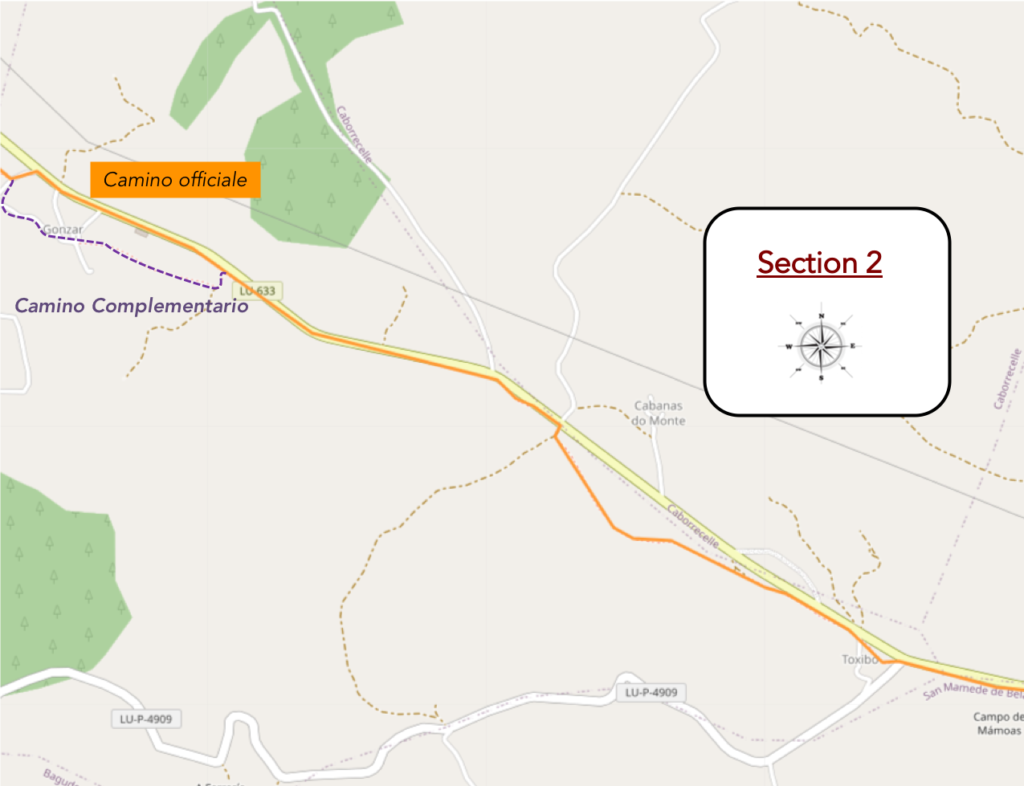

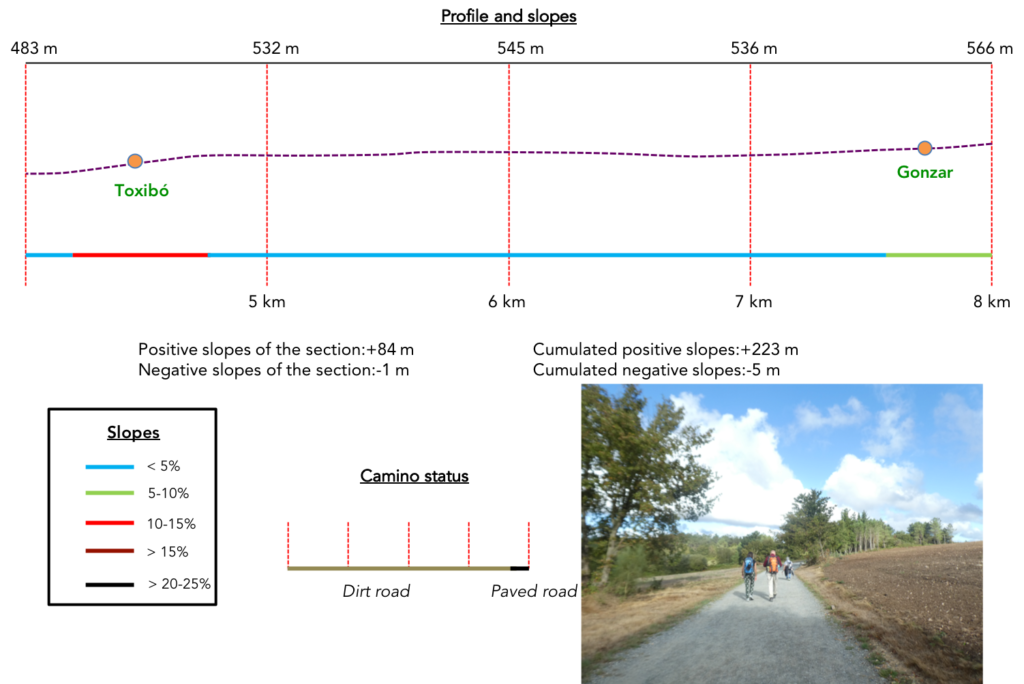

Section 2: On the “Senda de los Peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without great difficulty, often gently uphill.

| Further on, you can see a large fuel depot on the left of the road. |

|

|

| No, here, it is not the Vuelta cyclist that crosses the road, at the level of the fuel depot. The cyclists are divided into two groups: those who have their luggage transported, and, less numerous, those who are loaded like mules |

|

|

| In this immense Spain, it is still a luxury to be able to pass the “Senda de los Peregrinos” from one side of the road to the other, isn’t it? Here, two pilgrims, sitting in the grass, consult their phones. Couldn’t you do 5 minutes without these superfluous tools, when you walk? |

|

|

| Soon after, the pathway gets near Toxibó hamlet. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway climbs steeply along the few houses in the hamlet. Stone still reigns supreme. |

|

|

Here stands an elegant hórreo in stone and wood, decorated with a rose window and surmounted by a finial at one end and a cross at the other. It is the most elegant of these Galician heritage monuments that you have come across so far.

| Further on, at the exit of the hamlet, the pathway finds the “Senda de los Peregrinos” back. |

|

|

| But, here, surprise, it deviates a little… |

|

|

| …to visit a little further on an undergrowth where first the oaks grow, then the pines. It is quite nice that these ladies and gentlemen of the Xunta de Galicia offer a space for recreation to pilgrims from time to time. |

|

|

| Because it is quickly back to current affairs on the relentless “Senda de los Peregrinos”. |

|

|

| On the other side of the road is the hamlet of Cabanas Do Monte. There is nothing for pilgrims there. In this long plain, there are crops. Probably cereals. |

|

|

| The pathway then runs along undergrowth, along the road. Here, of course, there are oaks, but also pines, chestnuts and ashes. Ash trees are often present at the edge of the woods, where there is light |

|

|

Further on, there is a picnic spot under the trees. But, it is as always in Spain. We don’t really know whom they serve

| So, a little further, here is something else that is useless or not very useful: the controversy between the “Official Camino” and the “Complementary Camino”. The complementary route will visit the village of Gonzar. The official route, no, because it follows the road. You choose. There is a bar on both courses. |

|

|

| On the official route, the pathway follows the departmental road… |

|

|

| …before finding a bar, now full as an egg. It is the great communion of the Camino de Santiago, where all nationalities meet. |

|

|

| It smells a bit like a scam. The brave visionaries of the Xunta de Galicia are administrators. As in all useless administrations, it is necessary to occupy these people who manage the roads. So, they invent tricks to confuse the pilgrim. It’s a safe bet that they left the official path by the side of the road to thank the volunteer work of the bar. But, we can also be wrong.

On the “Official Camino” you can take a look while passing towards the village. You will see the steeple of the church pointing behind the corn. In the Middle Ages, Gonzar belonged to the Knights of the Order of San Juan de Portomarín. With this entire heritage, shouldn’t they have reversed the two courses? |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino leaves the “Senda de los Peregrinos” to return to the interior of the country. |

|

|

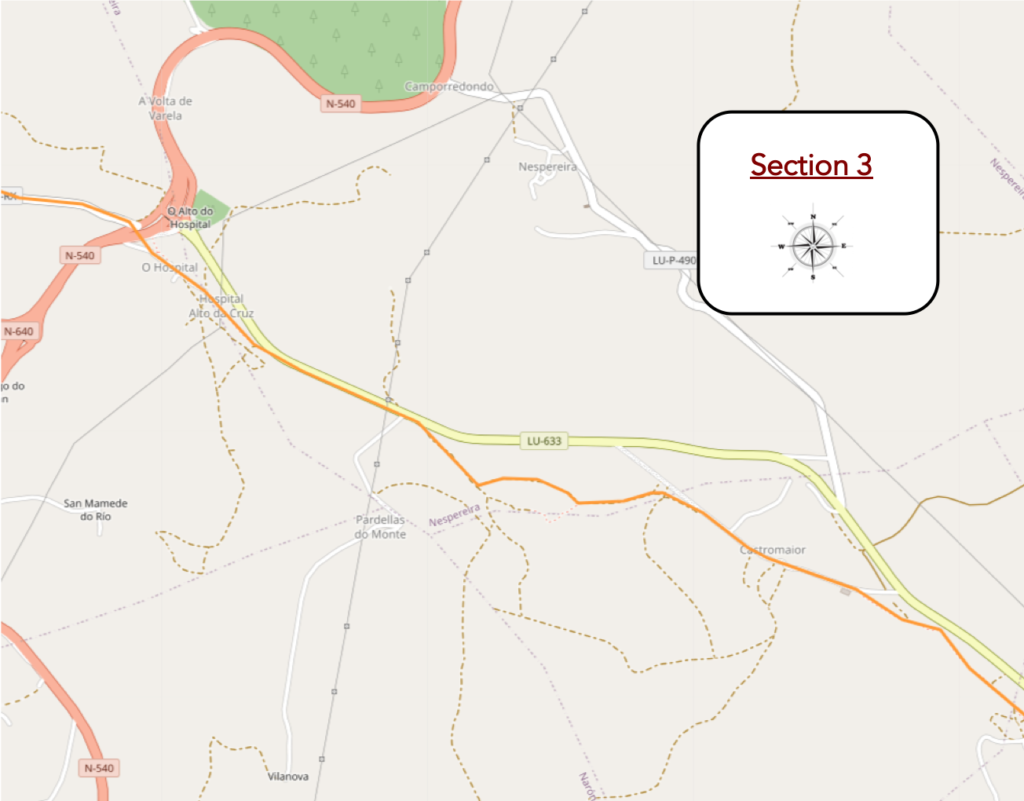

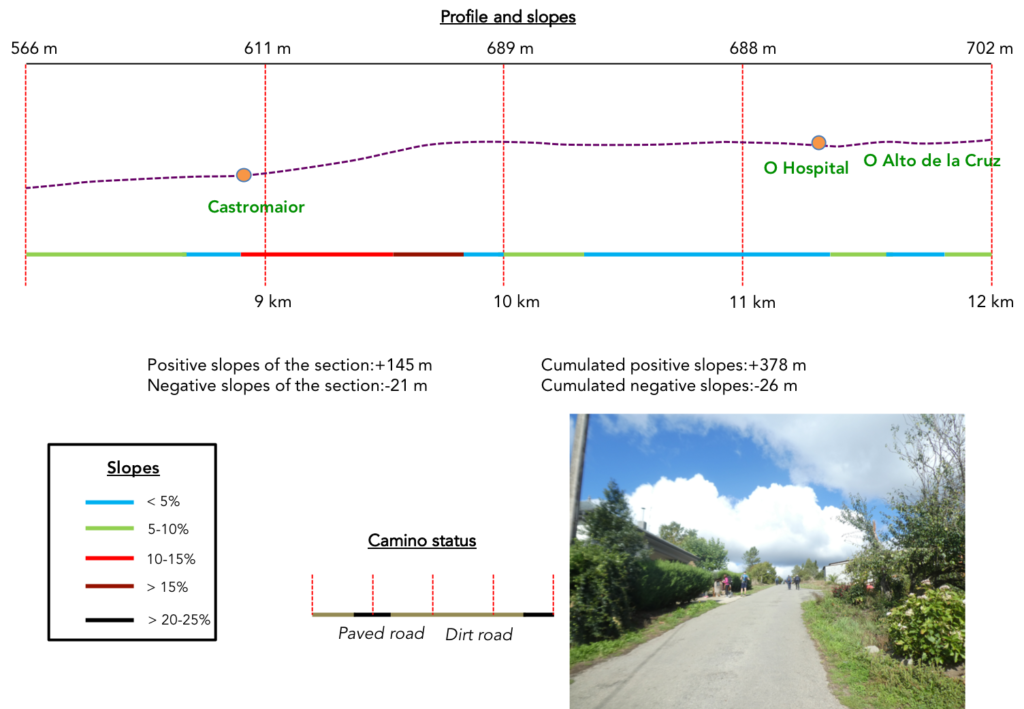

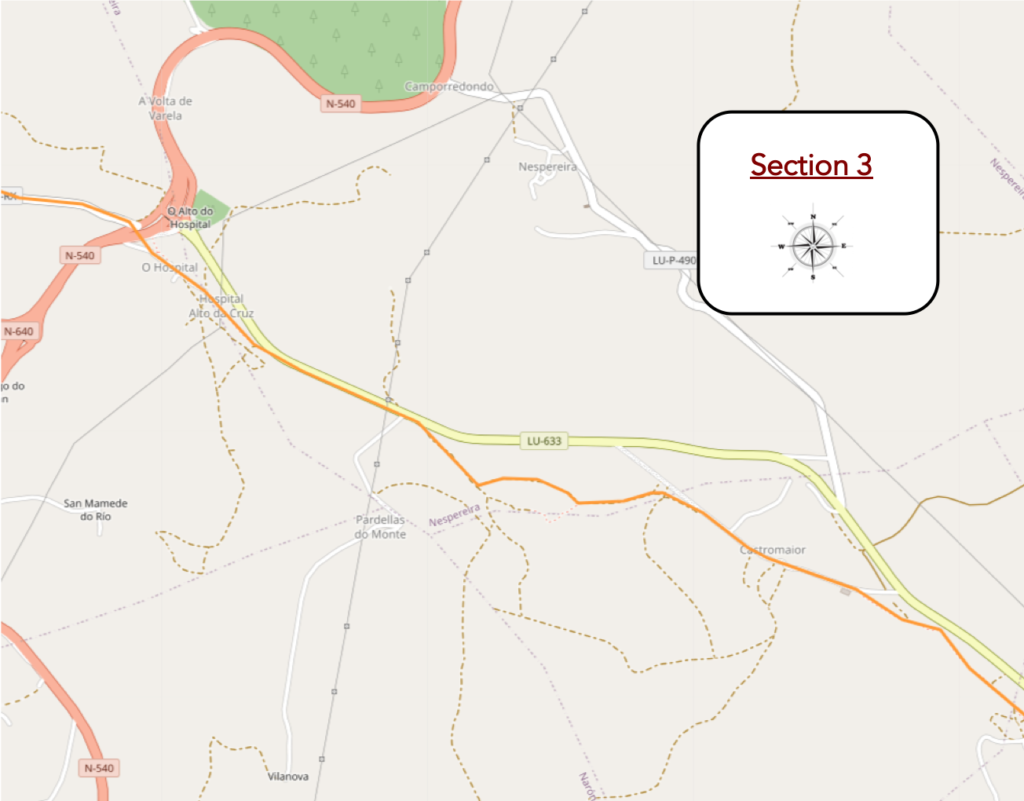

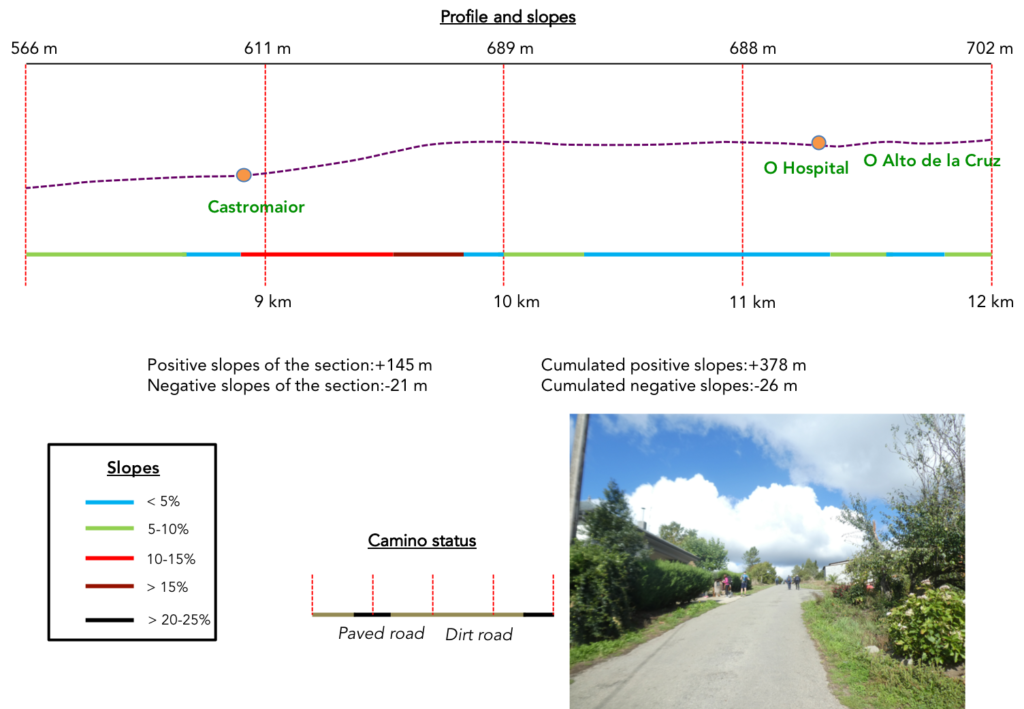

Section 3: Almost a “pass” on the course.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: quite difficult climb in places.

| First there is a small stretch of road in poor condition which climbs quite steeply at the exit of the village. |

|

|

| Then, the slope softens and the road gives way to a wide pathway that runs under the slender pines. |

|

|

| So, the oaks replace the pines, along the stonewalls. Here, the path is a little rockier. |

|

|

| Pretty soon, you’ll spot Castromaior on the hill. |

|

|

| The village is built on the slope. Here also stands an elegant hórreo in stone and wood, decorated with two finials. Castromaior takes its name from a large pre-Roman castro, a fort that stood not far from here. |

|

|

| The village is a mixture of rough stone houses and more modern buildings. There is a tiny XIIth century Romanesque church here dedicated to Santa María. |

|

|

| Beyond the village, the slope is steep to the top of the hill. |

|

|

In these conditions, it is often the line of pilgrims that stretches out and grits its teeth. But, it is not the Anapurna, either.

| Further up, the Camino leaves the road for a rocky pathway towards the castle. It’s not a real castle. These are the remains of the Celtic castro, still visible on the hill. |

|

|

| The higher you climb the hill, the more it becomes deforested and soon becomes a flat steppe. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, a wide pathway follows the ridge… |

|

|

| …to find the departmental road further on and cross it. |

|

|

Here you are 82 kilometers to Santiago. A joke, right? But, not for everyone. There are many tourists on the course dragging their misery. Even if they give “Buen Camino” with a strained smile.

| Now, here you are again on the “Senda de los Peregrinos”. |

|

|

| But, the latter is capricious. It runs back to the other side of the departmental road. The Spaniards still had a lot of earthworks to draw this side of the roads for nearly 500 kilometers. Did the “Senda de los Peregrinos” predate the route, or did it come after? We do not know it. But, this has nothing to do with the track of the Middle Ages, because if the pilgrimage exploded during these periods, it withered thereafter, to almost disappear and be reborn at the end of the last century. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway deviates from the road, passes through the undergrowth, where the holm oaks are back in abundance, as often when the soil is of poor quality. |

|

|

| A stone’s throw away is the hamlet of Hospital de la Cruz. As the name suggests, there was once a pilgrims’ hospital here, but apart from giving the village its name, nothing remains of the medieval hospital, nor the chapel which existed until the XVIIIth century. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the route becomes a little civilized, arriving at a major crossroads, at O Alto do Hospital. Here the N-540, the national road, the North-South axis of the province, which descends from Lugo in the North, the capital of the region, intersect in the middle of the departmental roads. There is a large bar-restaurant at the crossroads. |

|

|

| Here the Camino takes a small secondary road, direction Ventas de Narón. |

|

|

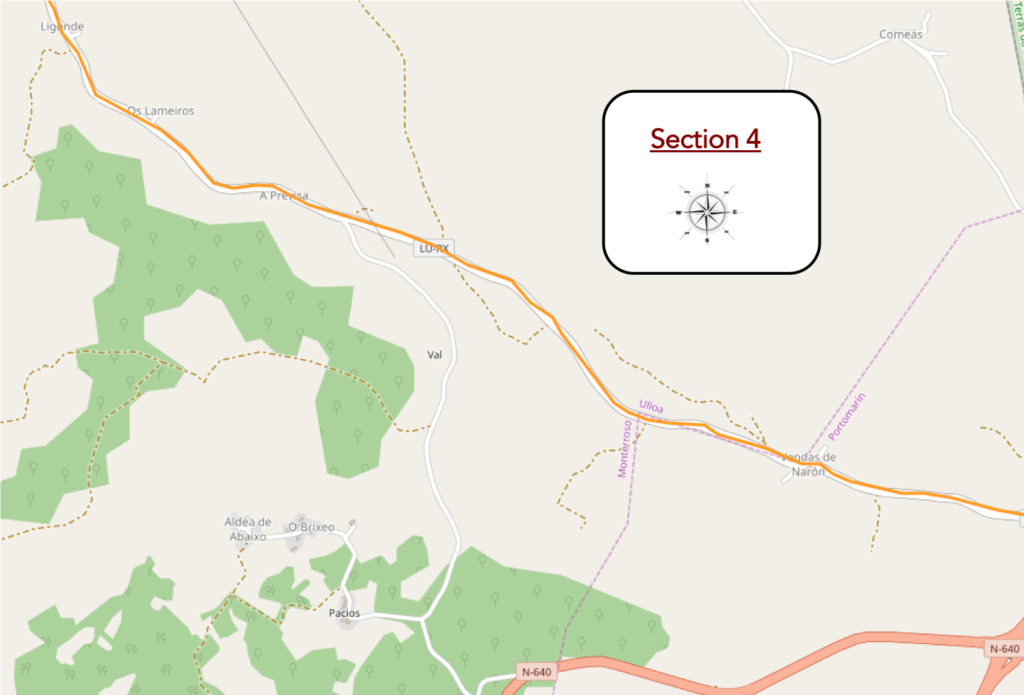

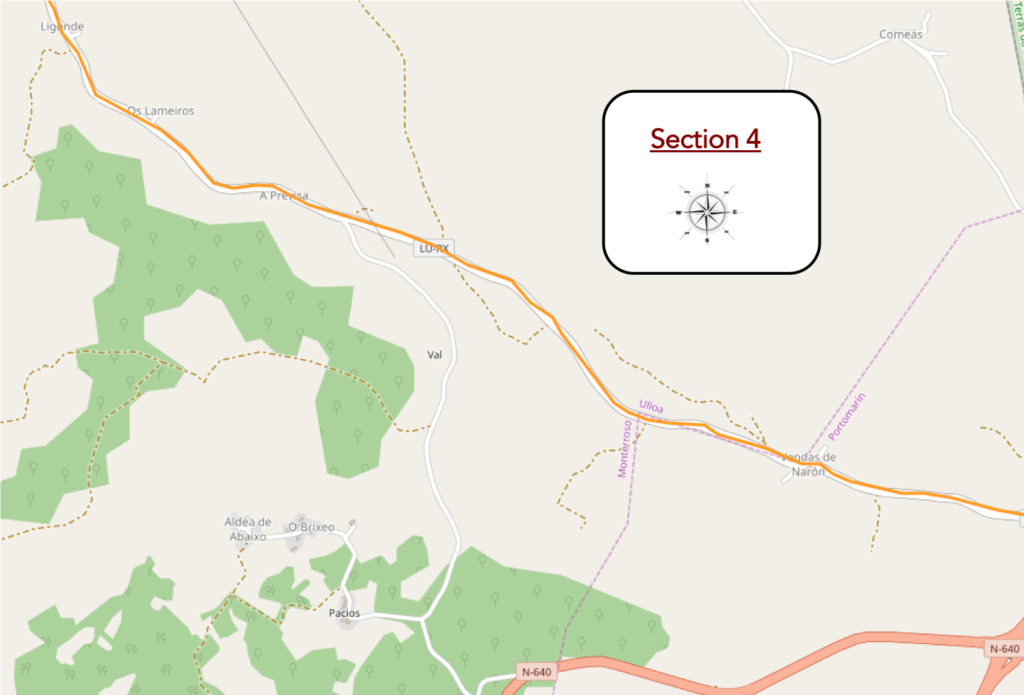

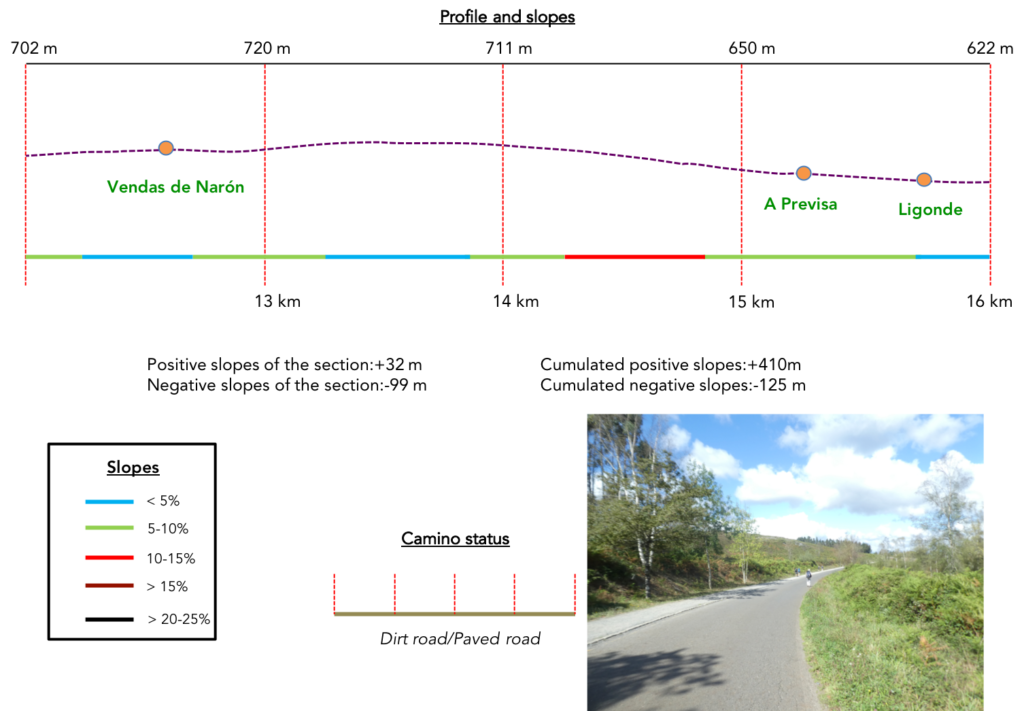

Section 4: Undulations between meadows and undergrowth.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: mostly downhill, but without difficulty.

| There is no exuberant traffic on this road. Often, pilgrims can use the dirt aisle for their own use. But, not all of them do. |

|

|

| Here, it is above all meadows, in oaks and birches. There are few crops in the region, which is above all a livestock region. Palas119 |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road reaches Ventas de Narón. |

|

|

| There is a crowd at the bar. Ventas de Narón is the place where, in 820, just a few years after the discovery of the tomb of Santiago, the Christians won a bloody victory over the troops of the Emir of Cordoba who were trying to conquer Galicia. In medieval times, the place was known as Sala Regina, as it says in the Codex Calixtinus. It was a stopover and a place of commerce. It had a pilgrims’ hospital built in the XIIIth century by the Templars. |

|

|

| La seule partie restante de l’hôpital est la petite chapelle en pierre de Santa María Magdalena. Il n’y a pas que foule au bar. |

|

|

The only remaining part of the hospital is the small stone chapel of Santa María Magdalena. It’s not just a crowd at the bar. Here it is the hunt for the “credential”. Tight as sardines, the pilgrims must first answer the questions posed by the facilitator. The “credencial” is primarily a religious matter, in fact, even if it has become a secular custom. So, you make it clear that you don’t understand Spanish, and the host, grumbling, stamps your document. In Santiago, the officials in charge of counting the “credencial” prefer to see seals of churches than those of bars. But, we have said it elsewhere. For this, the churches would have to be open, which is rare, when the pilgrim walks on the track.

| Beyond the village, the road slopes up gently towards the Serra de Ligonde. Here, at the edge of the road, a wide strip of gravel allows you to avoid the tar. |

|

< |

| Sierra means forest. There are conifers, mostly spruces. But, the soil is poor, in the middle of ferns, thickets of gorse, broom and heather. Sometimes the gneisses outcrop. It is the highest point of this stage at around 750m and offers superb views of the valleys below. |

|

|

| The descent of the Sierra is quite sustained. Sometimes it looks like a school race here, with pilgrims dawdling with their noses in the air. |

|

|

| Do you want proof. They even linger to watch the Galician cows in the meadows… |

|

|

| …or even play with them, in front of the bar of A Orevisa, in the shade of the chestnut tree. |

|

|

| Shortly after, at the edge of the road which slopes down in the thick vegetation, there is a place of picnic at the place called Cruceiro de Lameiros which others call Shortly after, at the edge of the road which slopes down in the thick vegetation, there is a place of picnic at the place called Cruceiro de Lameiros which others call Cruceiro de Ligonde. |

|

|

| Lameiros means pastures. It is a hamlet on the other side of the road. The Camino does not go there, but stops in front of the great XVIIth century cruceiro (crucero in Spanish), erected on the site of the old Capilla de San Lázaro. For many Galicians it is the most famous cruceiro of the Camino, representing the Passion of Christ, with a skull, bones, a hammer, nails and a ladder at the base. There reigns here an atmosphere between religion and the school race. |

|

|

| Just below the cruceiro, the road arrives at Ligonde. The village has existed since the XIth century. Here there was a hospital for pilgrims of the Order of Santiago, which existed until the end of the XVIIIth century. |

|

|

| In the past, many crowned heads stopped here. Today it is just a country village, all in length, with of course modest brick hórreos. |

|

|

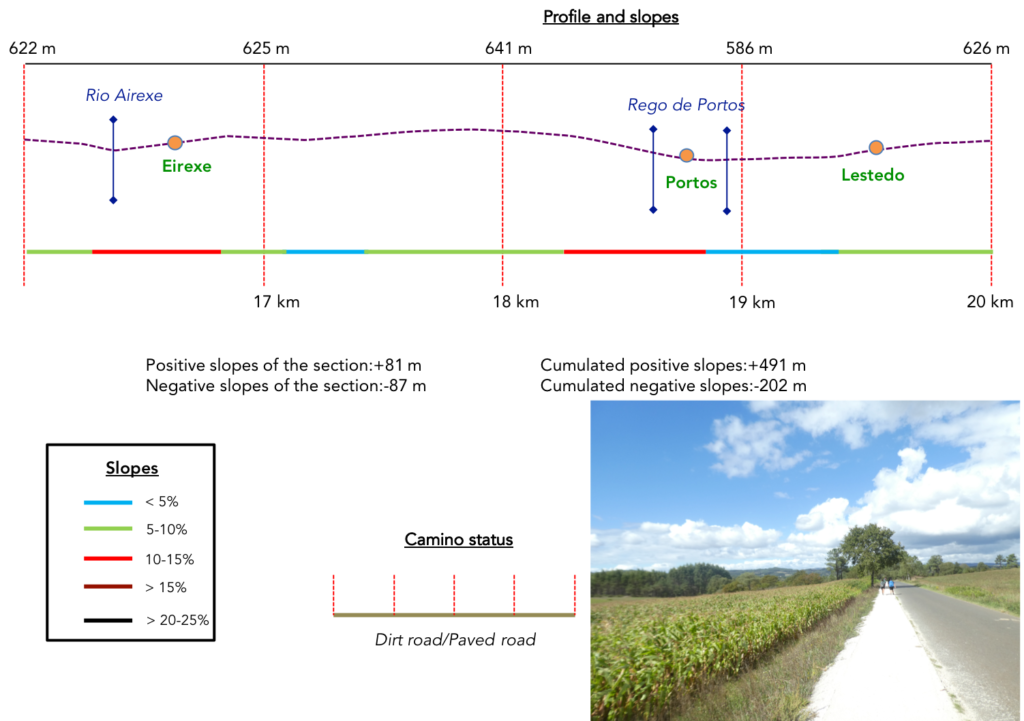

Section 5: From one village to another.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some slopes, but nothing difficult, even if the drop is 100 m, both positive and negative.

| The Camino leaves the village until you find a small shortcut that avoids the road that loops here. |

|

|

| The shortcut descends into the tall grass… |

|

|

| …until it finds the Rio Areixe, where it finds the road again. Two steps away, there is a bar under the trees. |

|

|

| The road slopes up back from the dale to reach Eraixe |

|

|

| Here there is a cruceiro and the neoclassical church of Santiago from the XVIIIth century, which preserves the Romanesque portal of a first church from the XIIIth century. |

|

|

| There is a good infrastructure here for pilgrims to rest, eat or stay. |

|

|

| The road continues to climb at the exit of the village. There is always a strip of dirt for the use of walkers, much like a traditional “Senda de los Peregrinos”. |

|

|

| Further on, the road passes in front of an old washhouse. |

|

|

| Then the slope is gentle. Here, chestnut trees, ash trees and even chestnut trees try to compete with the oaks. |

|

|

| Further up, the Camino comes to a crossroads, where it begins the descent to O Portos |

|

|

| At first, the slope is gentle, where the corn shares the space with the meadows. |

|

|

| It is here that the first eucalyptus appear, the king trees of Galicia by the sea. |

|

|

| The roadside pathway then descends steeper in the sparse woods, amidst oaks, eucalyptus and black poplars. |

|

|

Here you are 73 kilometers to Santiago.

| At the bottom of the descent the road passes to O Portos, where a stream flows that you can hardly guess. |

|

|

| Beyond the hamlet, the pseudo “Senda de los Peregrinos” continues under the trees, avoiding a road that heads towards Vilar de Donas, where there is a beautiful church with frescoes, 2 km from here. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road passes a place called O Portos, near a charming “albergue” and flattens under the trees… |

|

|

| …before finding a washhouse by the side of the road, apparently still usable. We even came across a pilgrim doing her laundry. |

|

|

| Lestedo is a stone’s throw away, and the road passes in front of the cemetery. All the villages in this region are small villages or even hamlets. |

|

|

| The parish church of Santiago de Lestedo, retyped over time, is surmounted by a bell tower pierced with two semicircular openings for the bells, and a third opening at the top. The cruceiro in front of the church door rests on a quadrangular pedestal. The upper part is new, because the old one was damaged a long time ago by a strong gust of wind. |

|

|

| Beyond the church, the pseudo “Senda de los Peregrinos” continues to climb gently towards the village of Os Valos |

|

|

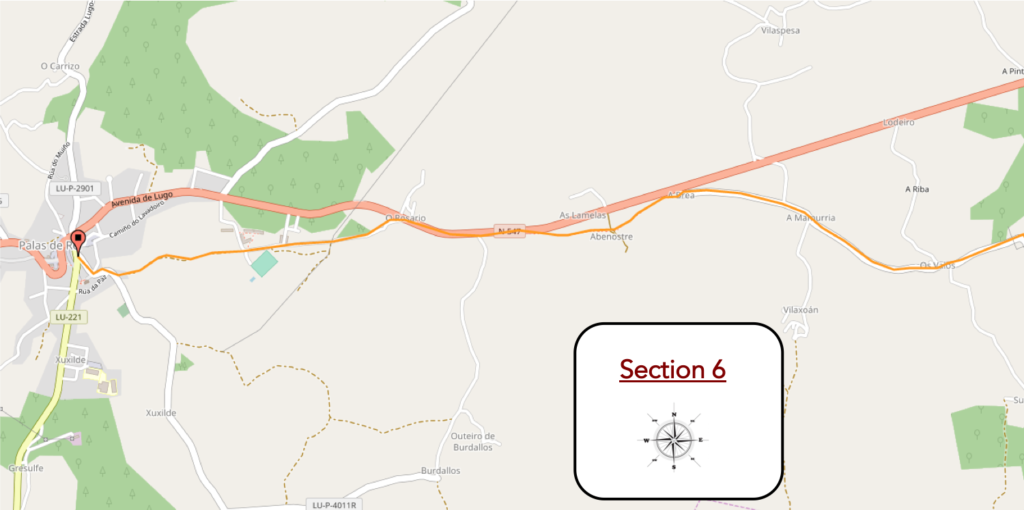

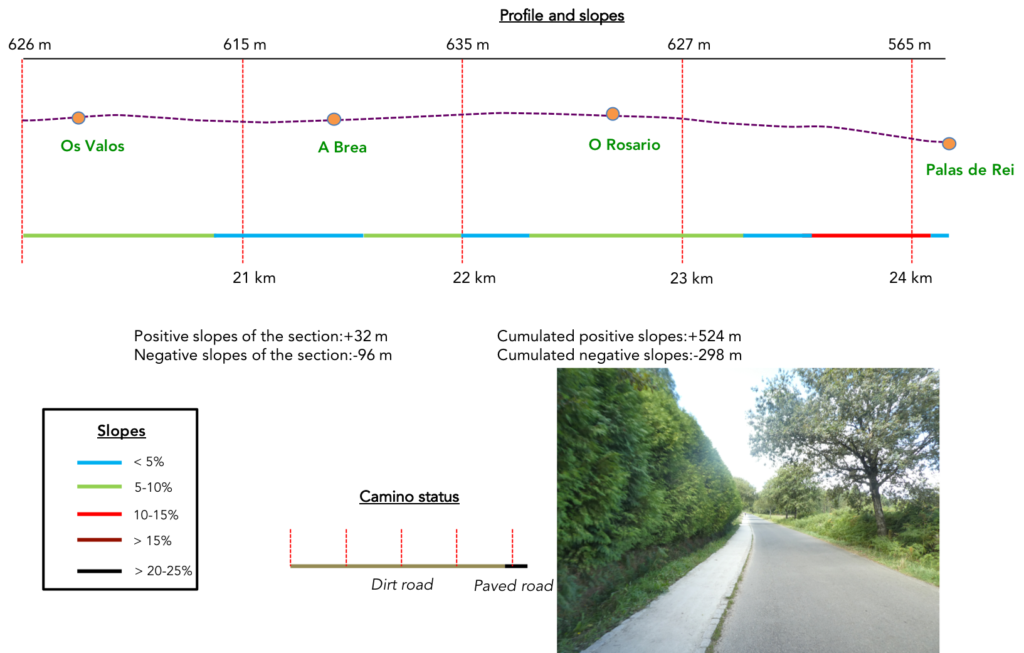

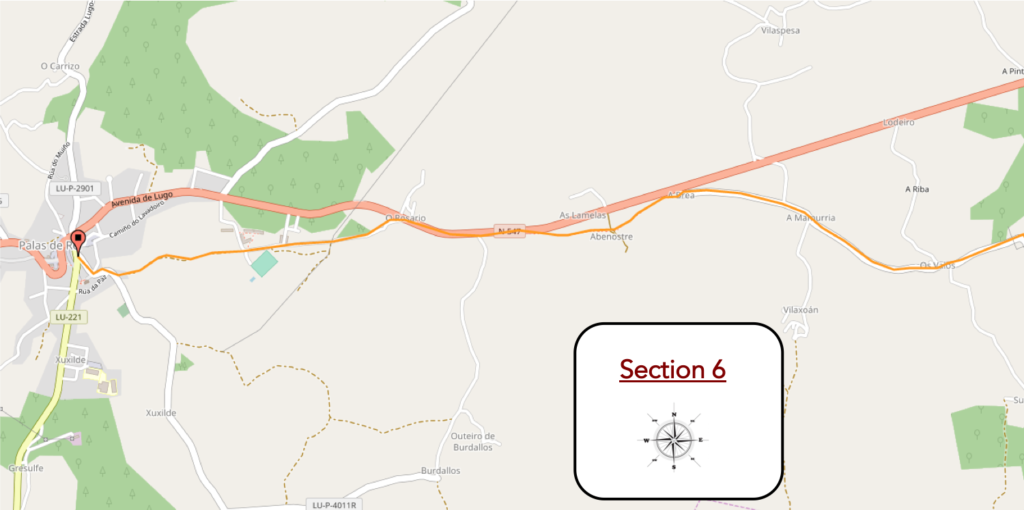

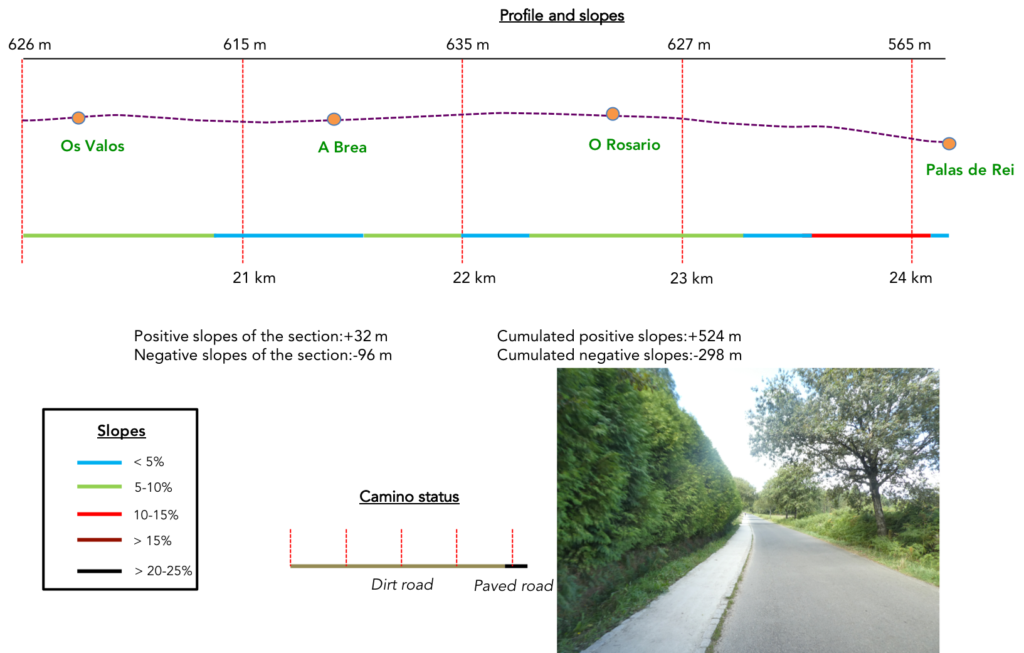

Section 6: At the end of the “Senda de los Peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: descent above all, without great difficulty.

| There is nothing for the pilgrim in Os Valos, with its few brick houses and hórreos. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pseudo “Senda de los Peregrinos” descends gently under the trees. |

|

|

| It is always the oaks that dominate the chestnut trees. When eucalyptus are present, they are compact plantations. We cannot tell you if they are used here to make pulp, as in Portugal, or if they are used to make furniture, poles or firewood. |

|

|

| In this region, there is almost no cultivation. These are above all meadows interspersed with woods, sometimes with the presence of cows. We did not encounter any sheep or horses. |

|

|

| The road soon arrives at A Brea, a haven of bliss and calm, like candy. |

|

|

| From here, the pseudo “Senda de los Peregrinos” ends, and it’s the return to the correidora, this type of Galician hollow track between the embankments and low walls, under the trees. |

|

|

| The pathway will undulate here gently, in the shade of the oaks. Nature is enchanting here. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway gets closer and will follow the N-547, the national road that connects Lugo to Santiago. The traffic there is tiny. There must not be often traffic jams in this sparsely populated part of Spain. |

|

|

Here you are 69 kilometers to Santiago. Next door, right?

| Shortly after, the pathway will leave the N-547 road, at the entrance to O Rosario. |

|

|

| In the past, when there were no slabs yet, when entering O Rosario, pilgrims would see the Pico Sacra, the sacred mountain above Santiago, and recite the Rosary here, hence the name of the hamlet. Today, you no longer see the mountain and the rosaries are almost all in museums. |

|

|

| At the exit of the hamlet, the pathwa still stays a little under the tall trees, before transiting in a recreational area, quite empty, we will say so. Palas de Rei is only 3,300 inhabitants. This explains that. |

|

|

| Further on, the parks follow one another. |

|

|

You can clearly see here that it is also a country of chestnuts. Yet we are only at the beginning of autumn.

| Beyond the park where you go out on the slabs, it’s back to dirt… |

|

|

| … before finding one last time the great oaks. |

|

|

| There is not a great transition from the countryside to the small town. The pathway soon arrives at the Church of San Tirso. Palas229 |

|

|

| Documents from the IXth century refer to a church on this site. However, the current church, which was built in the XIIIth century, has undergone many modifications over the centuries and the only original part is the modest Romanesque west portal |

|

|

But as the church is open, we still have to show you the interior without any particular style.

| Palas de Rei (King’s Palace), according to legend, received this name from the Visigoth King Witiza, who is said to have built a palace here, although the palace is long gone. Witiza was the last of the militant Arian heretics, who held that Jesus is the Son of God, but subordinate to God the Father, who created him. However, Roman and Celtic remains in the vicinity point to much older settlements here. The name of the city does not appear in historical documents until the IXth century. The city has always been an important stop on the Camino, marking the end of the XIIth stage of the Codex Calixtinus. Nothing remains of the heyday of the old city. There are a few mansions and noble houses scattered around to show the wealth of the area. But, you will probably not spend your holidays here. |

|

|

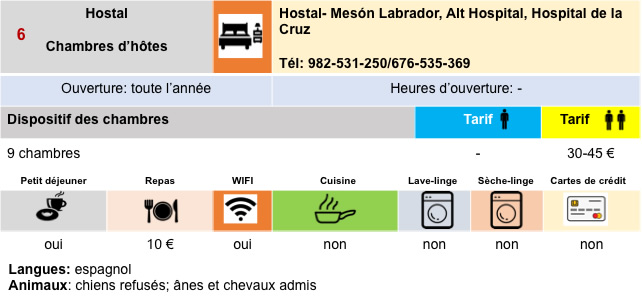

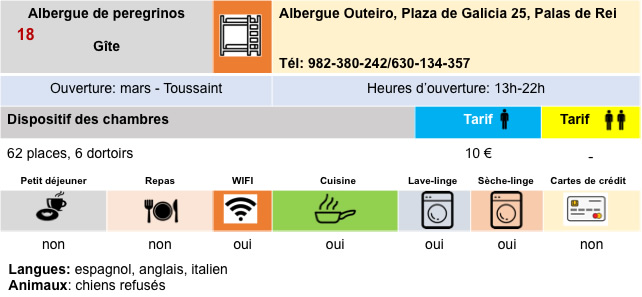

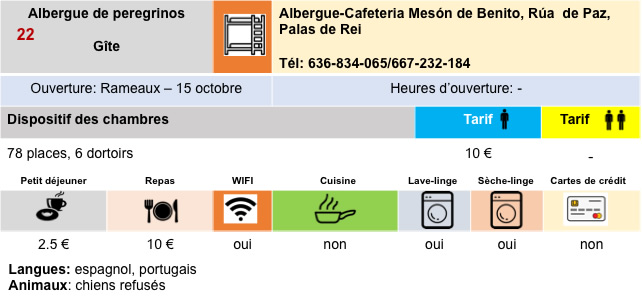

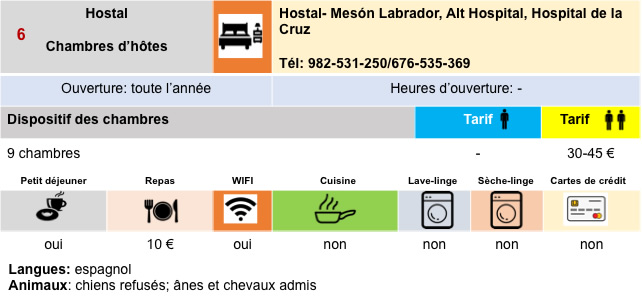

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 13: From Palas de Rei to Melide |

|

|

Back to menu |