Meseta, three syllables that evoke the desert

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

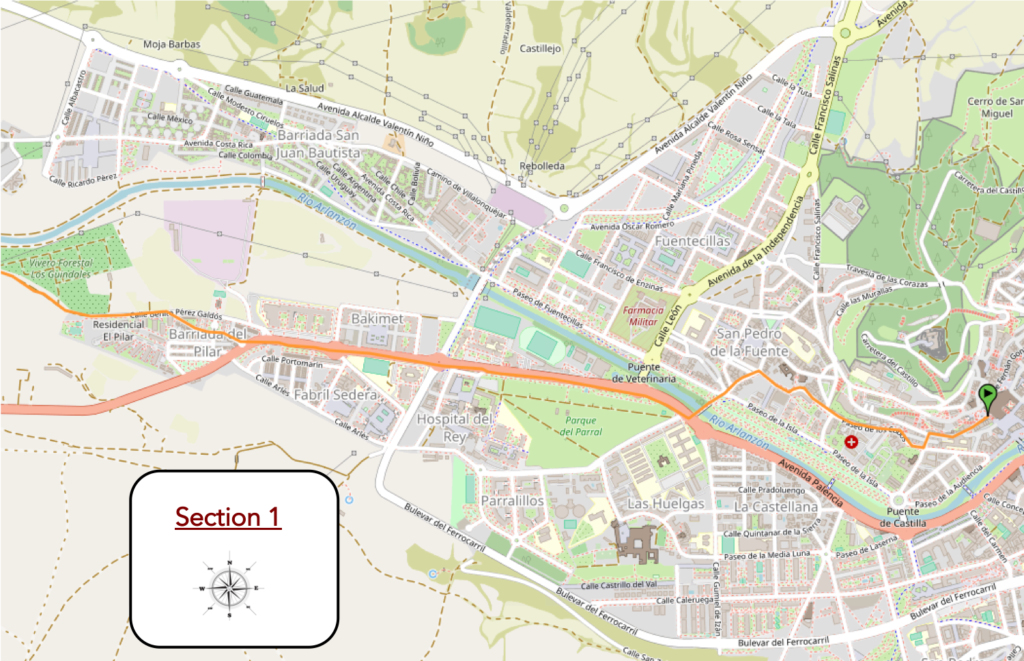

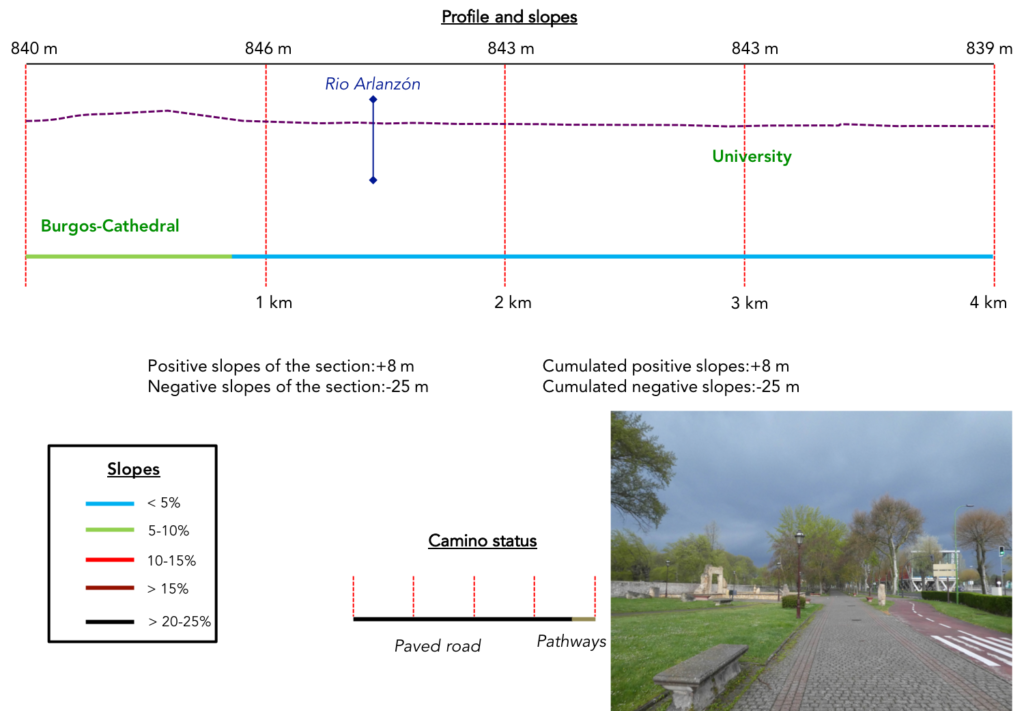

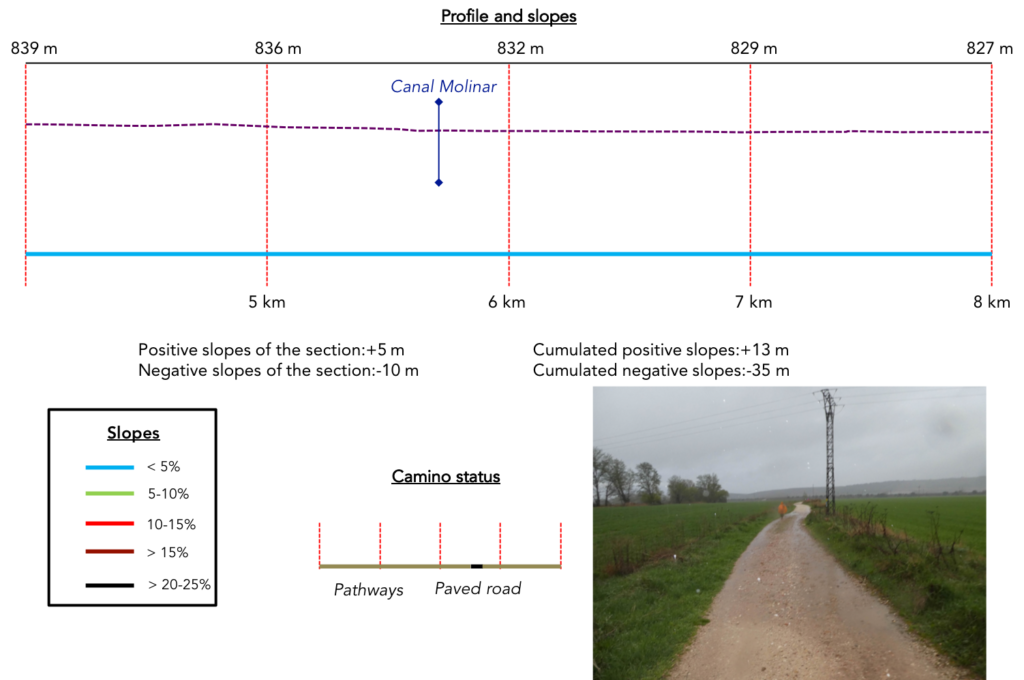

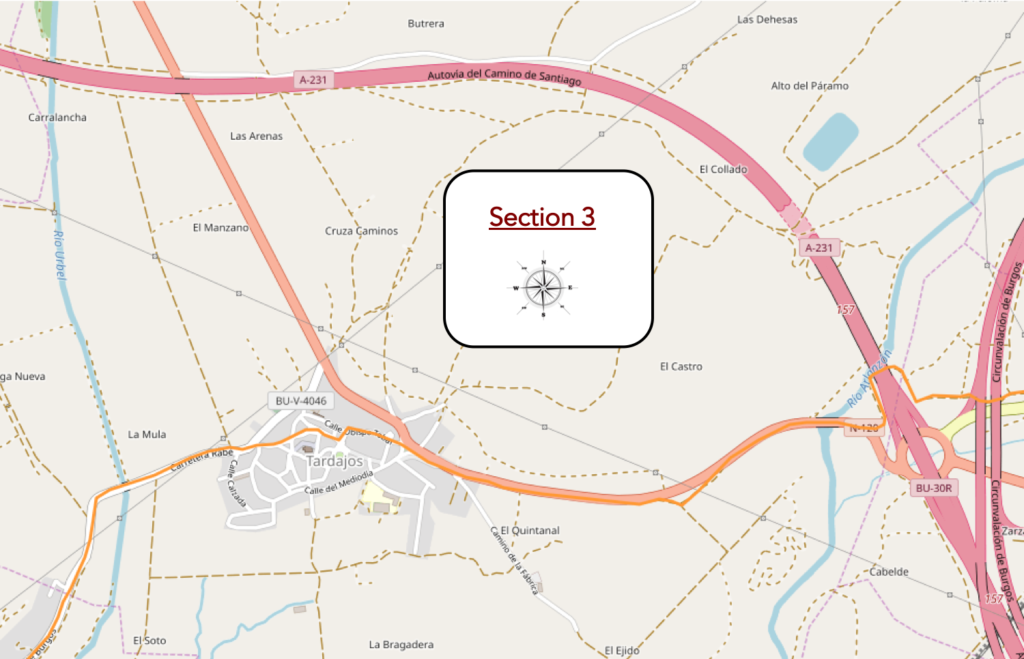

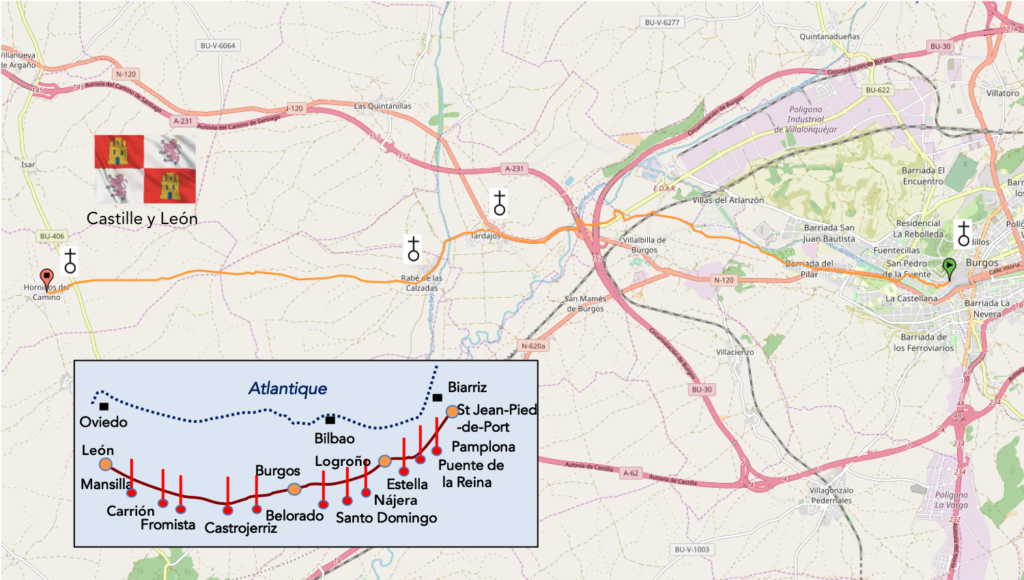

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-burgos-a-hornillos-del-camino-par-le-camino-frances-33833994

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

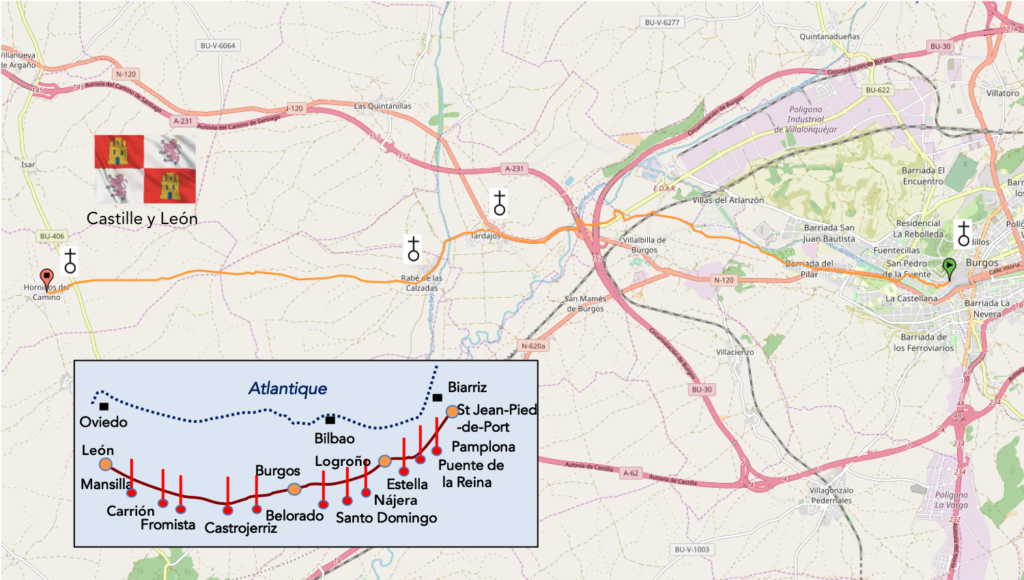

For many pilgrims, they enter Meseta only in Burgos. Some pilgrims even make the decision to go directly to León by bus or train, to bypass a dreaded route that has been portrayed to them, as a highway of boredom, without distraction, without trees. And yet, there have entered Meseta, head down, since the entrance in Castile.

But what exactly is Meseta? Central Meseta is the oldest relief unit in Spain and occupies most of the area. Its origin dates back to the Paleozoic, the primary era that extends from 550 to 250 million years, when the fish appeared, when many plates collided by creating mountains. Then the massif was eroded by Mesozoic erosion during the secondary era, or the era of reptiles and dinosaurs, between 250 and 65 million years ago. It was then a great peneplain, which still changed, at the Cenozoic, during the Tertiary and Quaternary eras, from 65 million years to the present day. The formation of the Alps, the erosion and the marine sediments of the Quaternary gave the current relief. The formation of the Alps also altered the edges of Meseta, causing the appearance of the Galician Massif and the mountains of León to the west, the Cordillera Cantabria to the north, the Iberian system to the east and Sierra Morena to the south. Spain is like a great fortress surrounded by mountains. It is not generally known, but Spain is the second most mountainous country in Europe, after Switzerland.

Meseta, called Meseta Central, is divided into two parts separated by the Central System. The Submeseta Norte, North Meseta, is at an average altitude of 700 to 800 meters, articulated around the great Duero River. The Submeseta Sur, to the south, is a little lower, with Tagus River axis. The Santiago track runs only in northern Meseta. (https://www.entrecumbres.com/sistemas-montanosos/meseta-central/)

As the geologic start is in the primary era, the rocks are therefore mostly granitic rocks, gneisses, schists, quartzites. Then, the marine sedimentation brought its lot of limestones, marls and clay. So, you will have rocks and soils often contrasting. The sedimentation process is more advanced on the eastern side of Meseta, the original hard and crystalline materials being more apparent on the western side

So, let’s get deeper into this Meseta, where some will say objectively that with an endless field to the right, then another equally similar to the left, it’s still not the happiness they hoped for in advancing a little further towards Santiago.

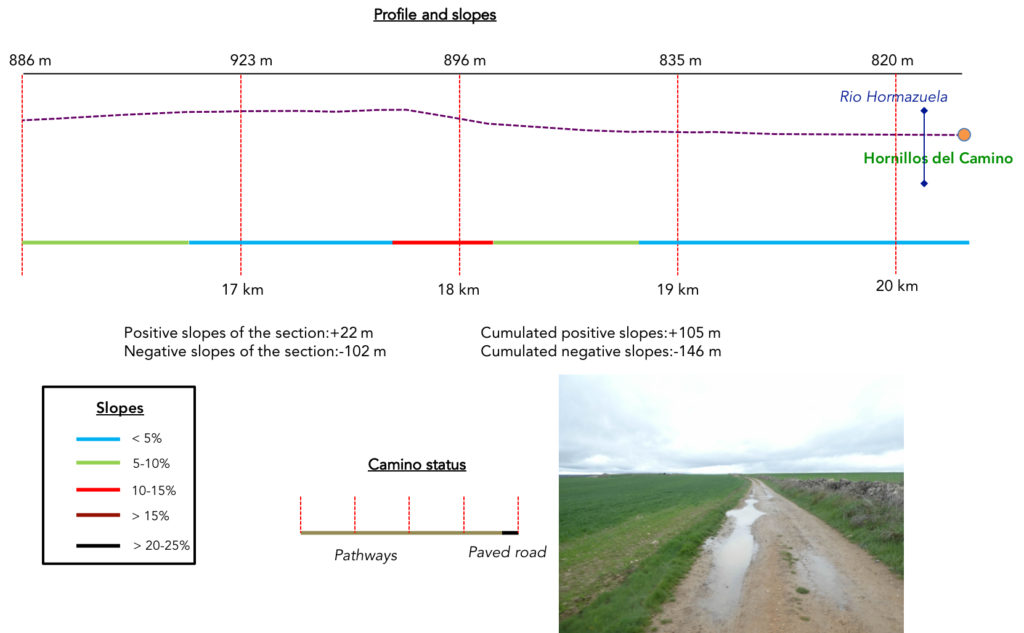

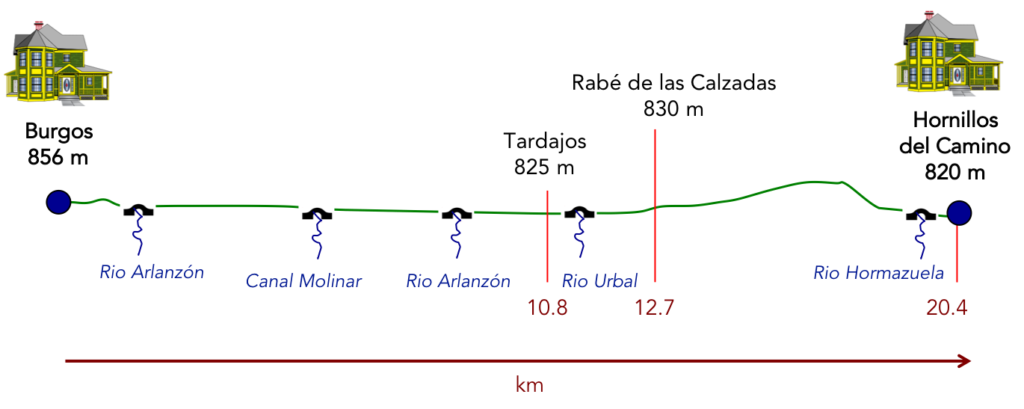

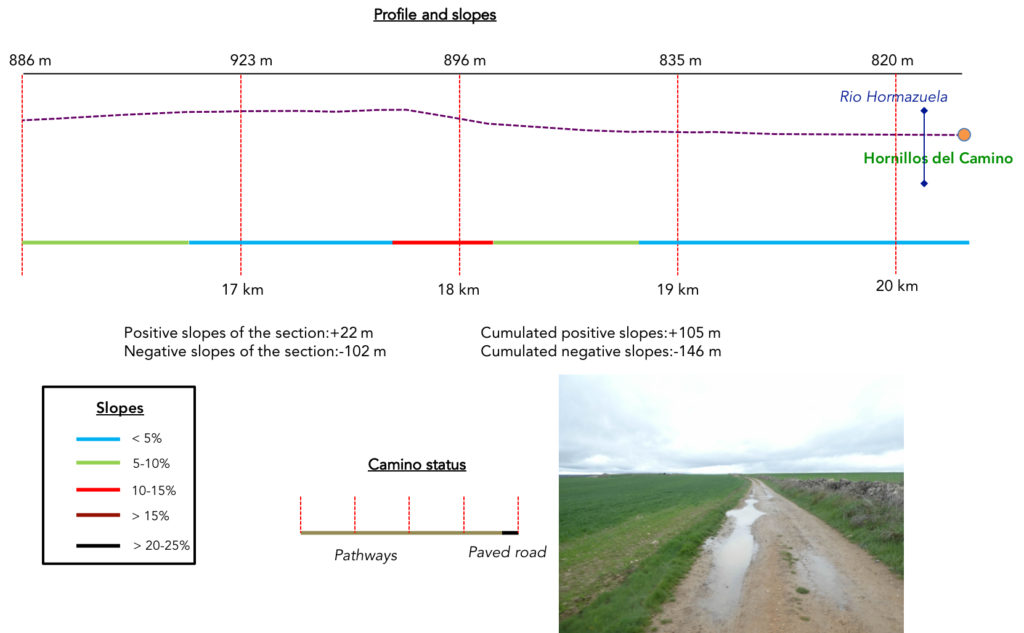

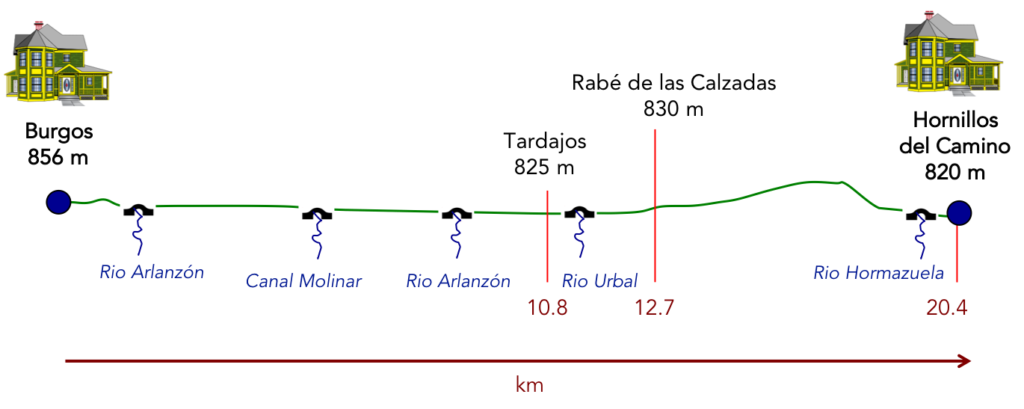

Difficulty of the course: Today, slope variations (+105 meters /-146 meters) are insignificant. It’s a flat ride, with just a slight bump before arriving. But, of course, if you make this trip in the rain, it’s not the same story.

In this stage, most of the journey takes again place on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

In this stage, most of the journey takes again place on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 7.0 km

- Dirt roads: 13.4 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

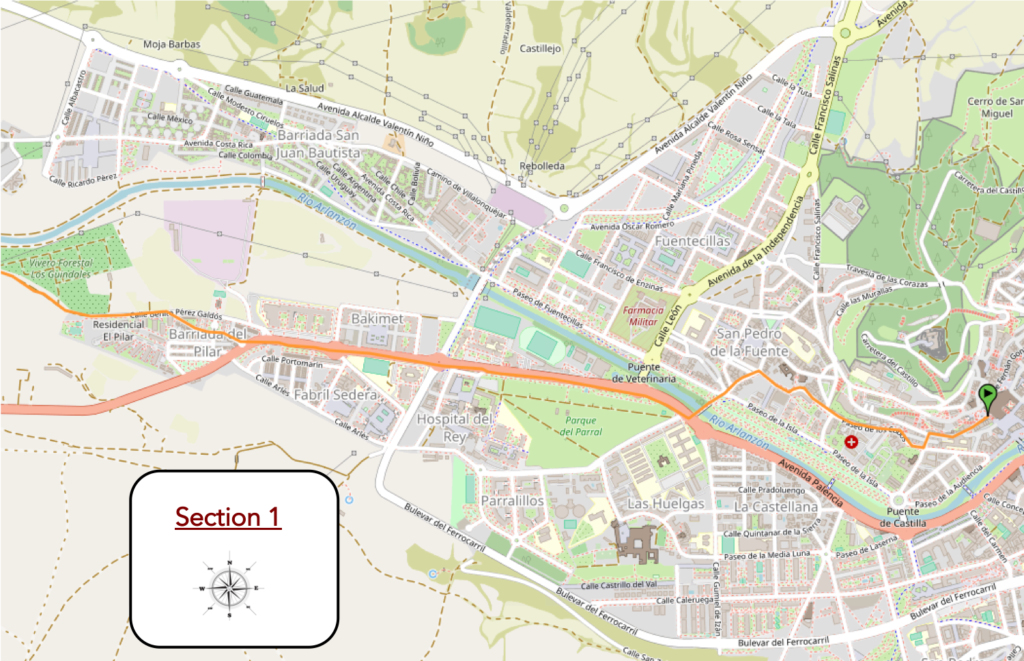

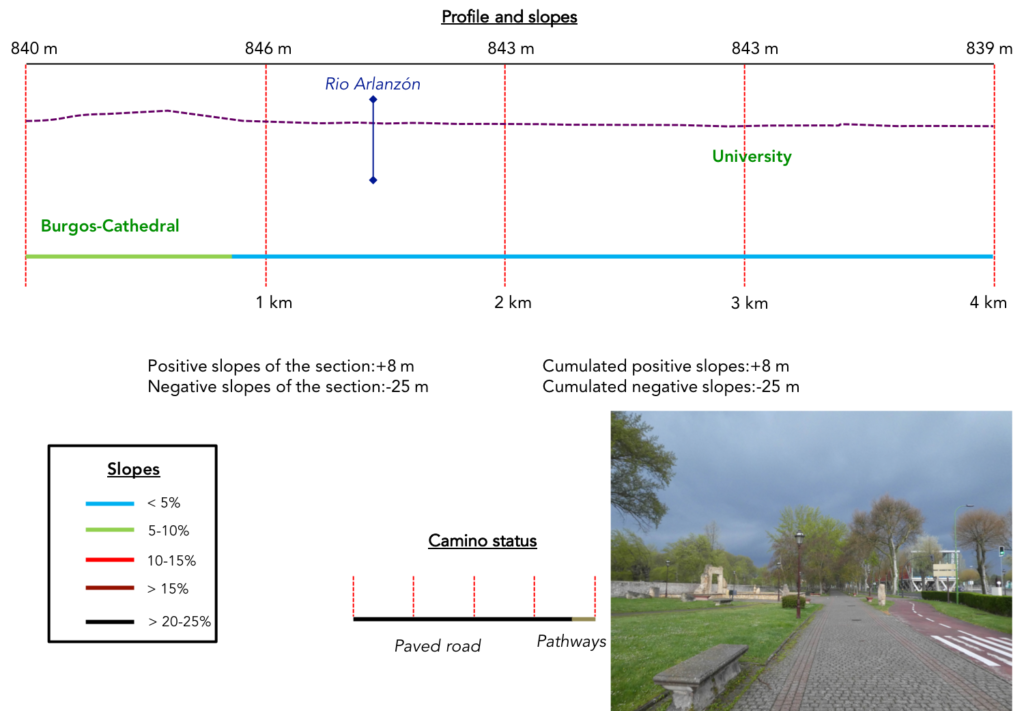

Section 1: You must leave the city.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| This morning, it threatens to rain and Burgos is empty. The only people you’ll meet in the early morning are the garbage collectors and the pilgrims. It’s going to rain, it’s written. |

|

|

| Not a single tourist or even a cat disturbs the serenity of the beautiful cathedral. |

|

|

Burgos does not only have arches from fortifications like the famous Santa Maria Arch. This one, close to the cathedral, is a small triumphal arch, built in the XVIth century, unknown to tourists. Only pilgrims and tourists who stay in a nearby luxury hotel, pass by here. The triumphal arch pays tribute to Fernán González, a local count who in the Xth century possessed nearly 30% of the current Castilla y León, a man even more famous than the Cid.

| The Camino soon reaches part of the fortifications, at the San Martin Gate, a gateway to the city, built in the XIVth century and part of the defenses of the city. |

|

|

| Extramuros, you’ll find the parish of San Pedro de la Fuente, one of the oldest parishes in the city. It owes its name to the former presence of a salt water source. The parish dates from the Xth century, but the original church and the successive ones were destroyed over the centuries. That church dates from the early XIXth century. Next door is a hospice of Benedictines, active in the education of children. |

|

|

| Shortly after, The Camino leaves the old quarter of San Pedro for a more recent suburb. It starts to rain and the temperature is cool. |

|

|

| Here, you’ll see one of these bronze statues that make the charm of the city. These human-sized statues still represent characters, accessible and familiar. They have multiplied for twenty years in many cities, including Burgos. Here, the Camino approaches step by step Arlanzón River, which he crosses over a bridge. |

|

|

The river flows quietly beneath the tall black poplars.

| On the other side of the bridge is the familiar N-120 road. |

|

|

| The Camino then flattens on tight pavements, under the big black poplars, between Parral Park and N-120 road. The rain is becoming stronger and big black clouds block the horizon. |

|

|

| At the end of the park stands the Hospital del Rey, a former hospital for pilgrims from the Middle Ages, dating from the end of the XIIth century, transformed over the centuries. Today, some buildings are part of the University of Burgos. Nearby, there is an “albergue” of pilgrims. |

|

|

Here pilgrims leave, armed to face another day in the rain.

| The suburb extends a little along N-120 road, between the residential areas of Fabril Sedera and Bakimet, past the church of Nuestra Señora del Pillar. |

|

|

| Further afield, you get to the city limit, and then the Camino regains its rights, becomes a dirt road again. And as if to celebrate the passage, the rain becomes torrential. Everywhere, pilgrims are busy adjusting their rain gear so they can keep something dry at the end of the stage. |

|

|

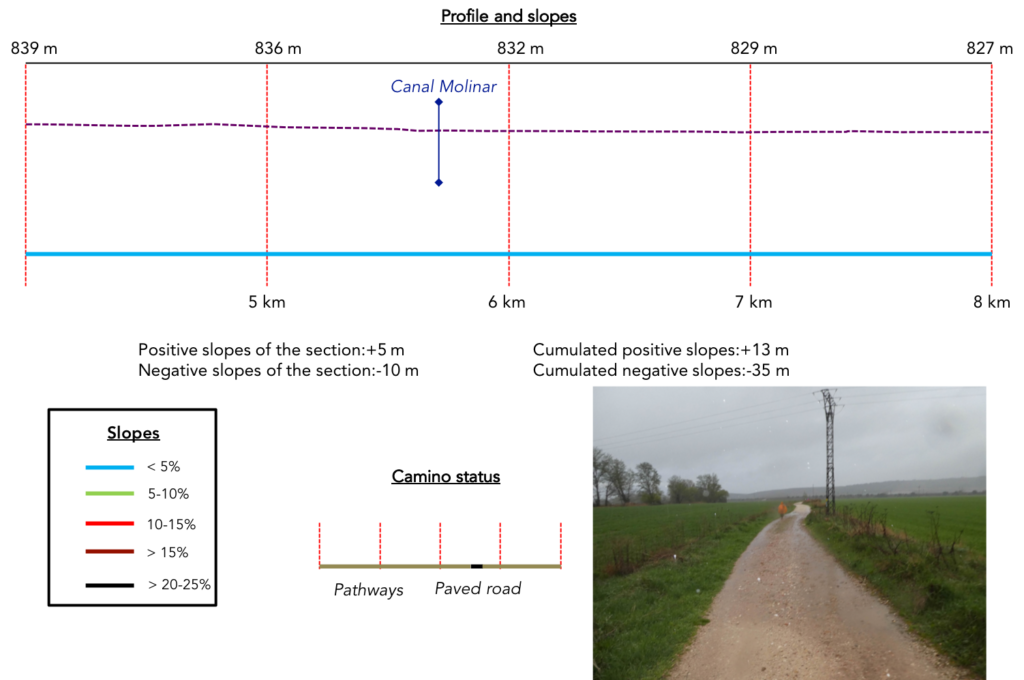

Section 2: The Camino gets closer to the highways.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| In the pouring rain, the pilgrims curl up under their cloaks, walk without a word on the wide gravel road full of water, not far from the river. Here you enter full foot in Meseta. At first, the landscape hesitates between meadows, crops and moor, but today we do not see much under the drops of water that pearl over the capes.

On this long dirt road of several kilometers, we had to use our camera only in minimal portion. |

|

|

| A little further, the dirt road crosses, near Bañada del-Real, a paved road, then continues immediately through fields. The gusting wind from the south-west makes the capes swell. |

|

|

| The dirt road, now flooded, passes under the railway track. Here, they are often small lines used for piggybacking. Further afield, it heads to the motorway interchange. |

|

|

| The bulk of the rain has now fallen, and even rags of blue sky are visible. The pathway is getting closer and closer to the motorways, passing over a bridge to avoid a departmental road. |

|

|

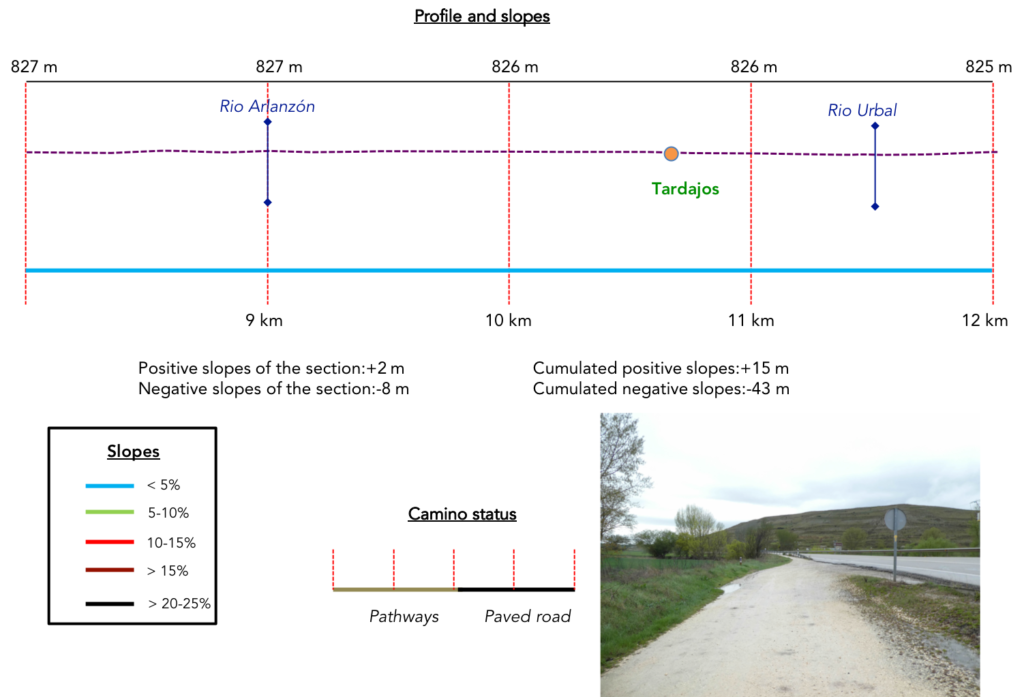

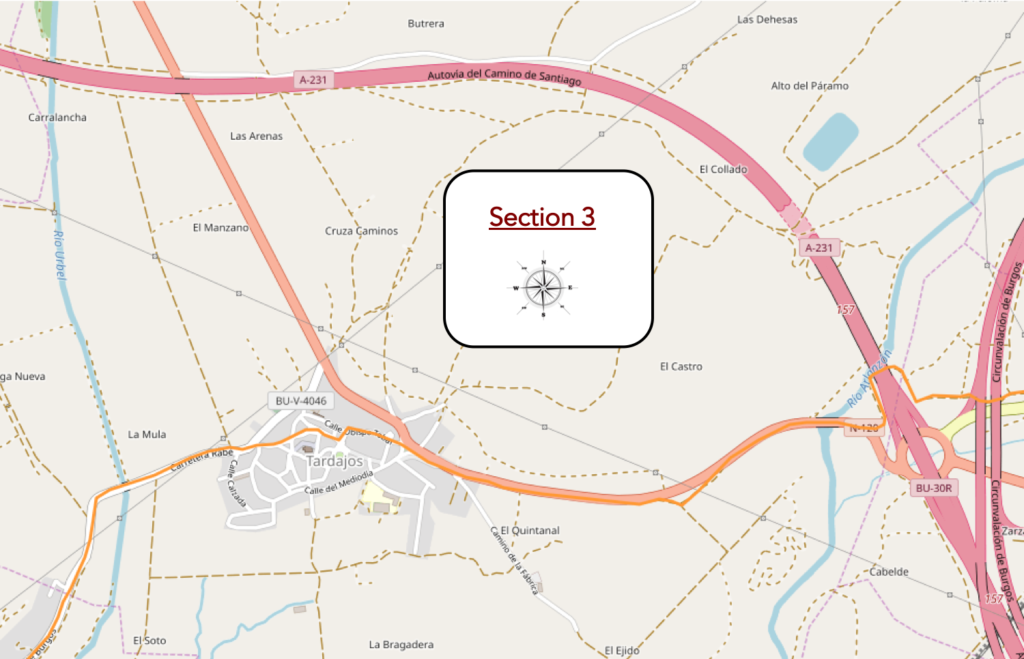

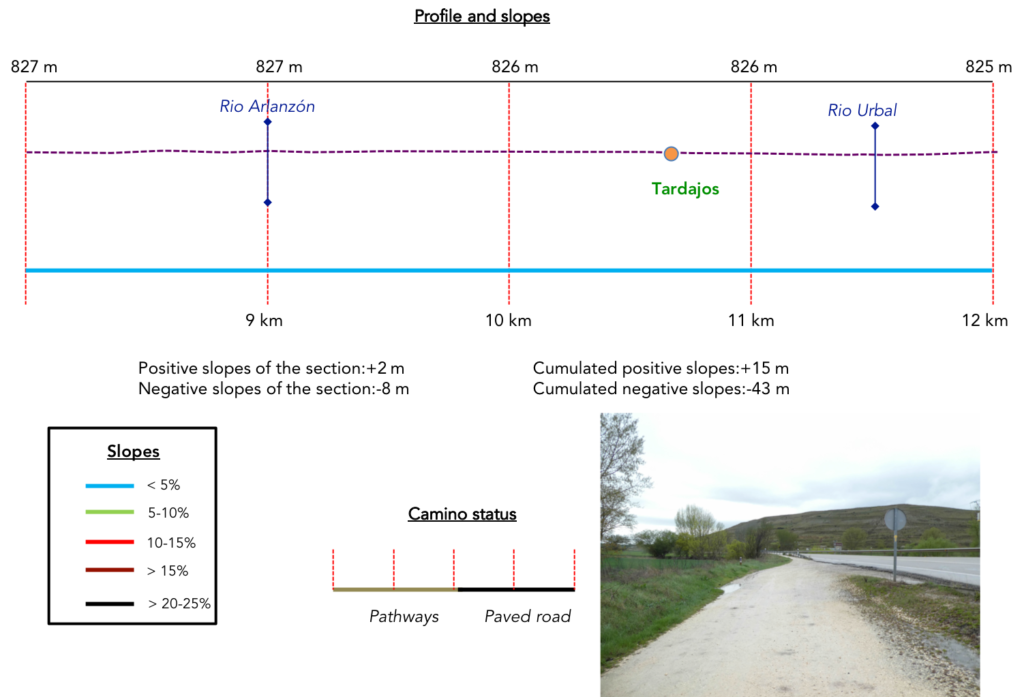

Section 3: Through a complex interchange of roads and highways.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Further ahead, the pathway makes a detour into the wheat to reach the intersection of highways. On the right side is the highway that goes to León, the Autovia del Camino de Santiago, the Pilgrim Highway. On the left, it is the major axis of the highway that goes down from the north to Valladolid, then Madrid. |

|

|

| The pathway plays a little with the motorway network and heads towards the motorway that goes towards León. |

|

|

| It runs under the piers of the highway to Arlanzón River that frolics between meadows and black poplars. |

|

|

| The pathway then crosses the N-120 road and heads towards the river. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the dirt road crosses the Arlanzón River and gently slopes up along the N-120 road, that you couldn’t stop looking in all these stages. |

|

|

| On the today soggy ground, the pathway gradually climbs between the fields and the road to the village of Tardajos. Now the rain has stopped and will perhaps leave us safe until the end of the stage. The pilgrim often lives in hope. |

|

|

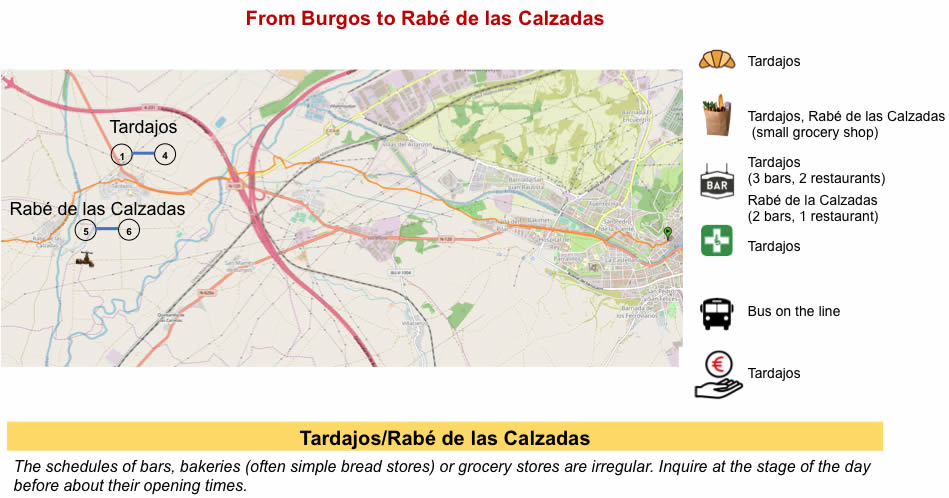

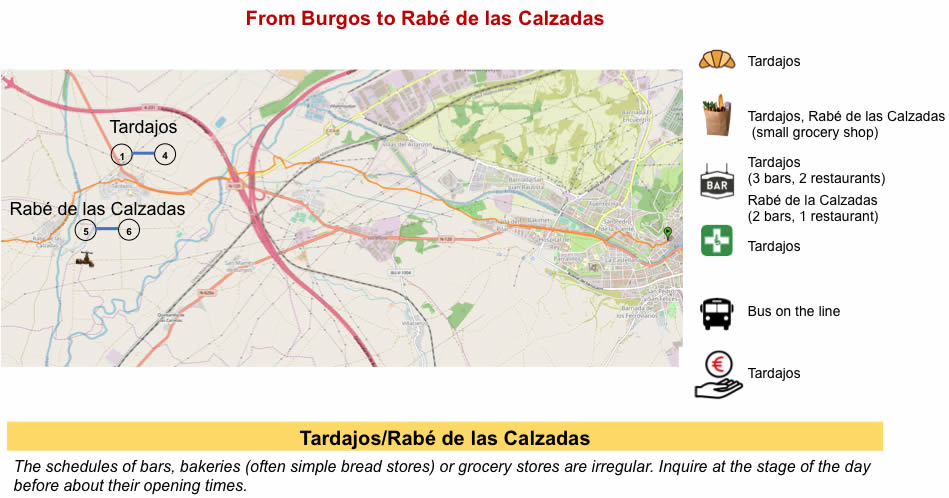

| The Camino arrives on the paved road in the village. The village, of Roman origin, was once located on a Roman road. The village was mentioned in the Codex Calixtinus. |

|

|

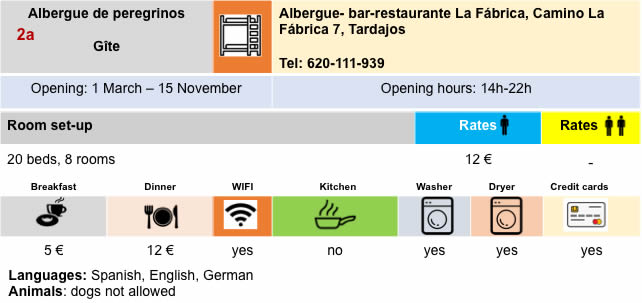

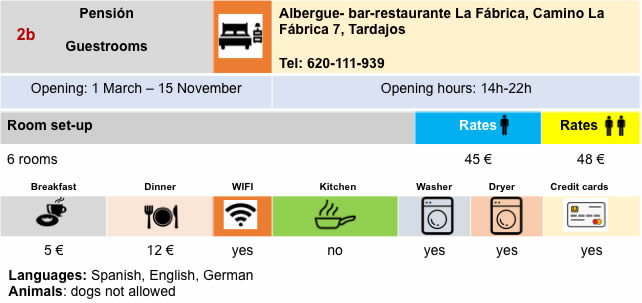

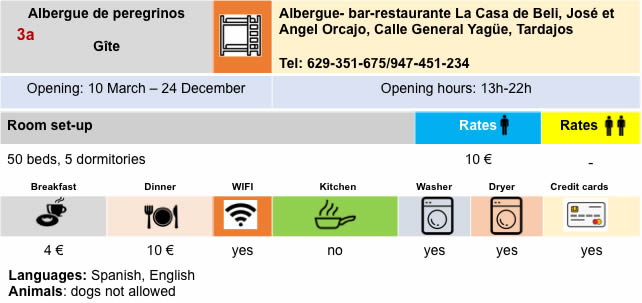

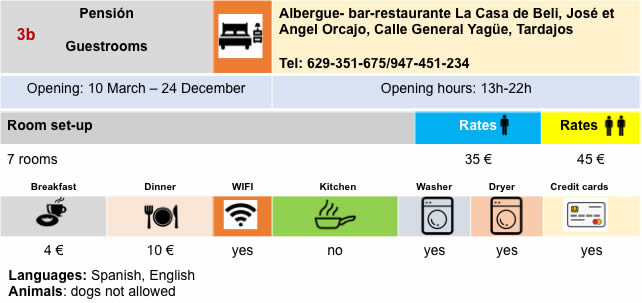

| On the Camino Francés, all villages, the most developed and the poorest, all have at least one “albergue” for pilgrims or a restaurant. Here in Spain, unlike France, it is not the bakery that is present, it is rather the sausage shop |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village, people pay homage to a local priest. |

|

|

| The Camino passes through a rather poor village, with simple houses, often made of simple bricks. But this village, like the others, has its church. In a very Catholic country, where people are still going to Mass, the statistics do not say whether the churches are still open on Sundays. The answer is probably yes. |

|

|

| Beyond the village, the Camino flattens on a paved road, but it is almost always possible to walk on the ground at the edge of the road. |

|

|

| In front of you stands a small hill above the cultivated plain. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road crosses the Urbal River, hidden under the black poplars. Rivers, quite important, are present in fairly large proportion in the Meseta. In a country that looks like a desert in summer and autumn, you understand that all this water in the spring is very useful for crops. |

|

|

| The paved road, which hardly slopes up, runs under a small hill and gradually reaches the first houses of Rabé de las Calzadas. |

|

|

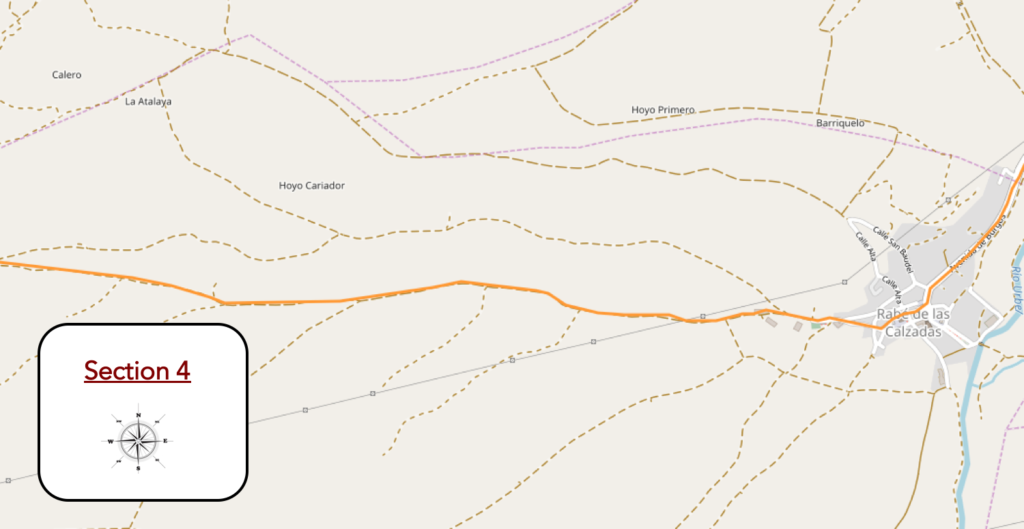

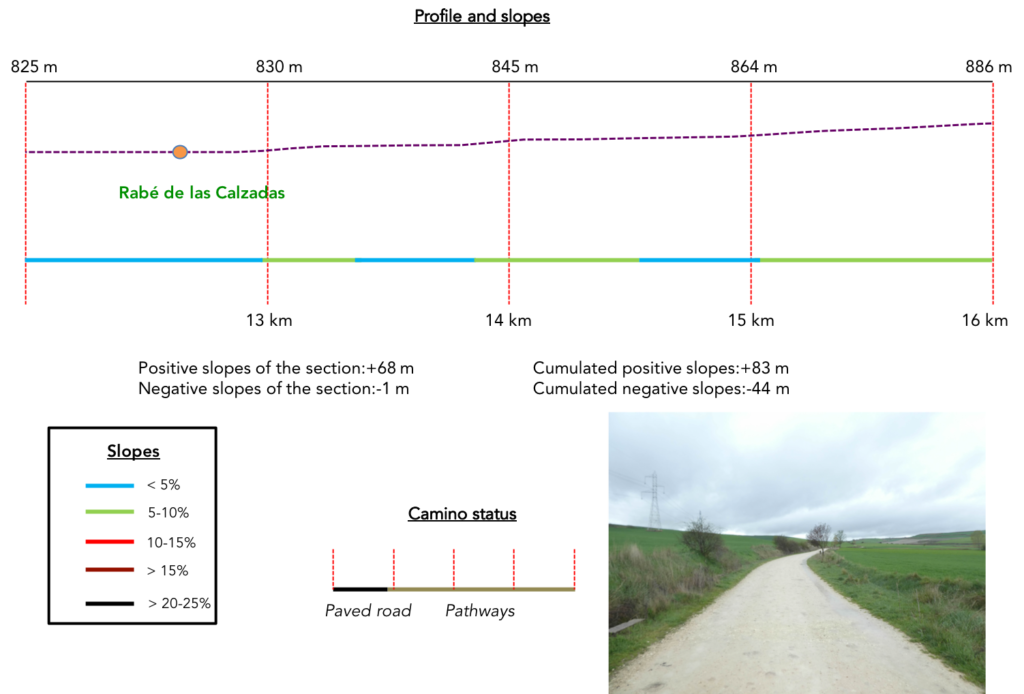

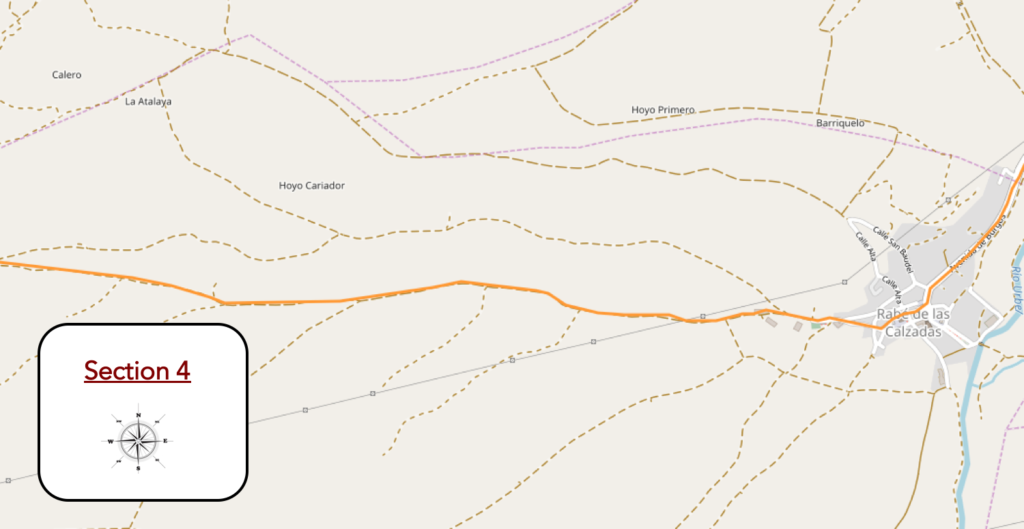

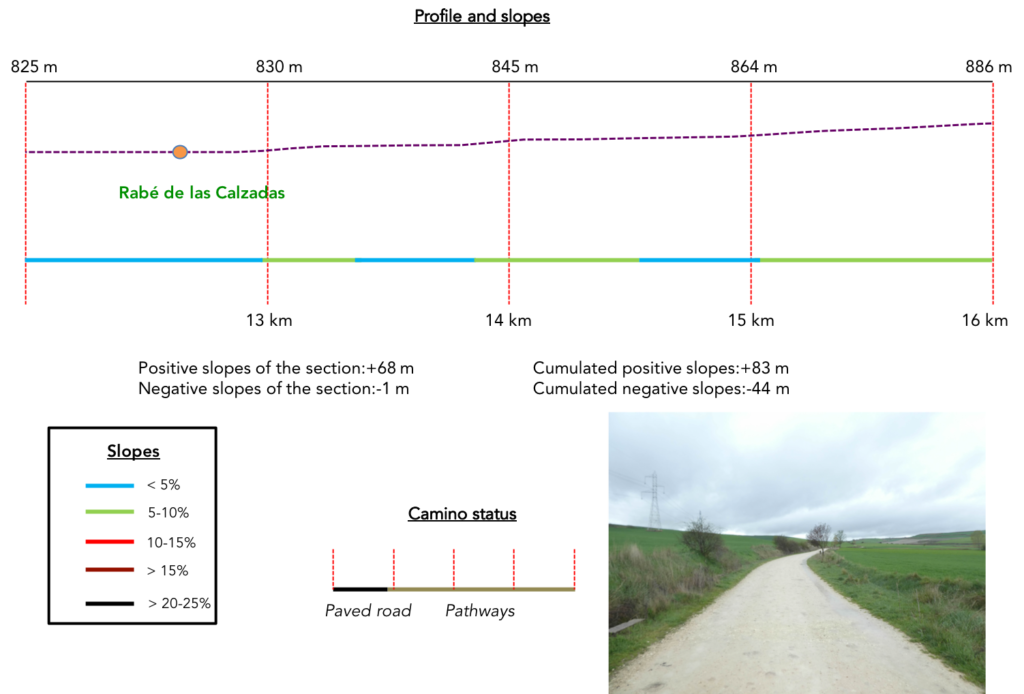

Section 4: A small climb in the nature, just to stretch your legs.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: some light slopes.

| The road soon gets to Rabé de las Calzadas. Calzadas means roads, indicating that the village has long been a milestone on the way from Santo Domingo de la Calazada. The village was not always called that. The name is of unknown origin, although there are several theories. Some say it may come from rabbi, which in Judaism means teacher, as there was a Jewish settlement in the village before the expulsion of the Moors from Spain. Others make other assumptions. Rabé could be the name of an important person who lived here. The first use of the name Rabé dates back to the Xth century, but at that time it did not appear with the suffix “de las Calzadas”. This would have been added later, as several Roman roads once passed through here. Old documents indicate that the medieval village was defended by a castle and had three churches. No trace remains today. However, the XIIIth century Church of Santa Mariña may have been built over one of the early churches. The castle protected the townspeople during the Reconquista, but was completely destroyed in the XVIth century. |

|

|

|

|

| It is a pretty, compact little village, with its stone houses, at the foot of the hill. The Peregrinos Santa Mariña y Santiago Hospital was built in the XVIIth century. Since 2000, it has been restored as an “albergue”. It must be said that many pilgrims stay here or in Tarjados. Just consider the number of beds available in these villages. Admittedly, the big battalion usually stops in the biggest boroughs, but with this way of doing things, it is sometimes more difficult to find accommodation. |

|

|

| The XIIIth century Church of Santa Mariña, closed as usual, has been extensively transformed, but retains a XIIIth century Gothic portal. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the top of the village passing in front of a jewel of a chapel. It is the hermitage of Nuestra Señora de Monasterio, in Renaissance style, dating from the XVIIth century, restored in the XXth century. Its name comes from an image of the Virgin found in the locality Monasterio. When you pass by these small villages, which seem so insignificant nowadays, it is hard to imagine what they must have represented in the Middle Ages during the great pilgrimages. Here, in addition to disappeared churches, there were also 4 hermitages. Just that! The San Roque, Santa Anna and Baudillo hermitages disappeared in the XVIIIth century. Only one remained.

But in terms of infrastructure, all is well in the best of worlds. Here, a sign announces that Europe will still invest to improve the path. Maybe one day it will be a highway. Discussions are going well among the elders who made the journey more than ten years ago. Everyone says, and with good reason sometimes, that the Camino has lost its soul of yesteryear. |

|

|

| The pathway will slope up the hill as soon as you leave the village. This is the only effort required of the pilgrims of the day. But rest assured. It is almost 5 kilometers of climb, but the slope never exceeds 10%. Although Spain is the second most mountainous country in Europe, about 40% of the country is made up of the Meseta, ranging between 400m and 1000m above sea level. A large part of it is in Castilla y León and will not end for you until you have reached the Bierzo, much further. |

|

|

| Here is the Meseta, in its beautiful and vast solitude. Almost no trees. Nothing but cereal fields as far as the eye can see, mostly wheat, others still covered with green manure. With the cold and rainy weather that reigns here this year in the spring, the wheat has not grown vigorously. The Meseta is largely treeless and windswept and extremely hot in the summer. |

|

|

| The pathway is wide, little crowded with stones, which is quite rare in the region, waddling on the hill. The Camino Francés always runs together with the European Way 1 which crosses Castile to go to Portugal. |

|

|

| Then, steps behind us, which are accelerating. It is a spanish guy who walks his young German Shepherd. He does as he says a little “caminata”, more than 15 kilometers each day, back and forth on the way. The couple advances at the speed of sound and quickly faints in the hill. |

|

|

| Further up, a bunch of black poplars, the only one on the hill, where a picnic place is set up under the trees. |

|

|

It’s likely that this refuge must be stormed by pilgrims in season, when the Meseta turns into a hot peeled desert.

| But in the spring, the Meseta is just a gigantic, endless, astonishing, outdated and unusual green desert. |

|

|

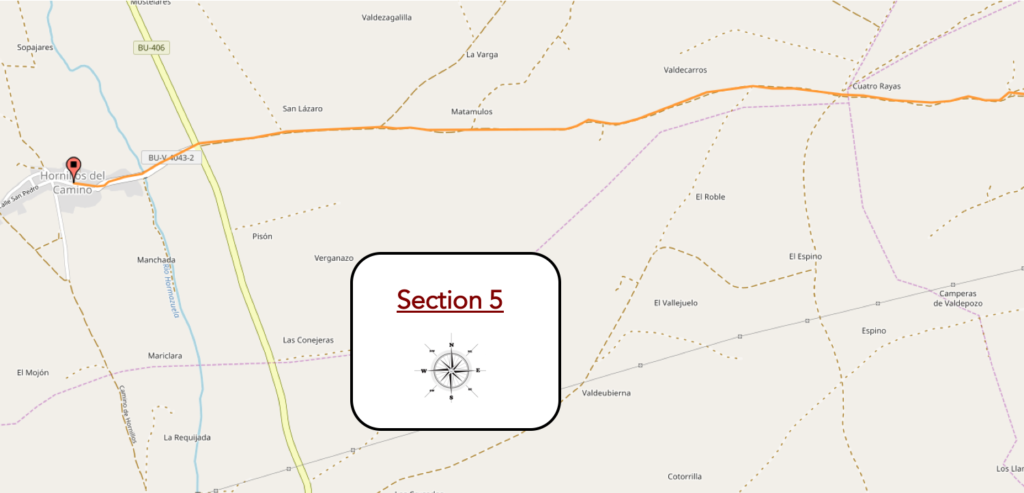

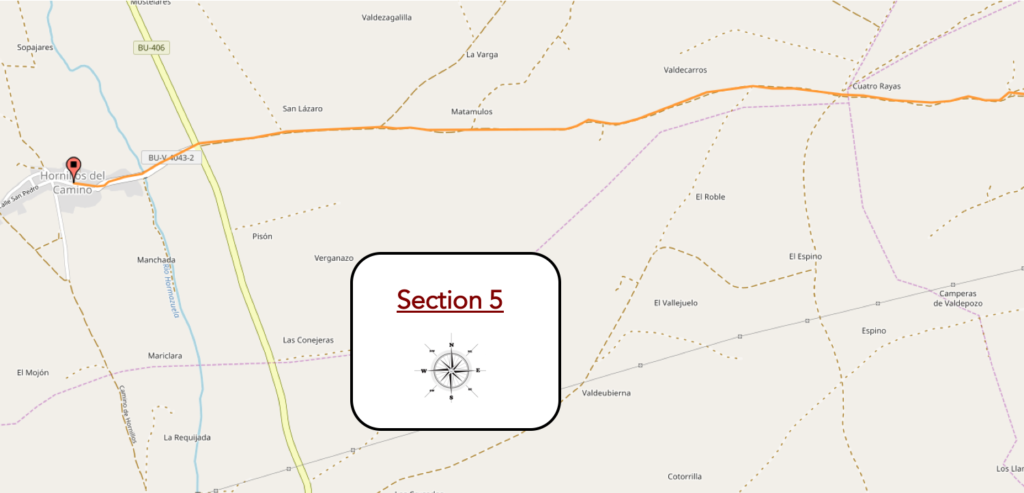

Section 5: From the top of the hill, the pathway descends to Hornillos del Camino.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without big difficulty, in light slope.

| You are not at the top of the hill yet. Sometimes today the pathway is a little soggier. The fields too. In the land where the green manure resides, it will be necessary to wait for the soil to dry before plowing, to plant perhaps corn, which is often planted last. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway reaches the Alto de Meseta, 950 meters above sea level. Here, it is a kind of small plateau where the slope becomes more and more gentle. Sometimes, near the heaps of pebbles formed by the peasants while stoning their fields, wild broom and wild cypresses grow, or rapeseed which has come to settle here according to the winds. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the landscape opens up, grandiose, infinite solitude. Transpose yourself to the Middle Ages and imagine the parade of pilgrims in these spaces of wind and solitude. It is estimated that the populations in Europe during this period must have fluctuated between 20 million and 100 million, depending on the plague and epidemics. As it is estimated that more than a million make the pilgrimage a year, there must have been an endless line here. More than 1-2% of the population, it is incredible to realize the Catholic fervor of the time. |

|

|

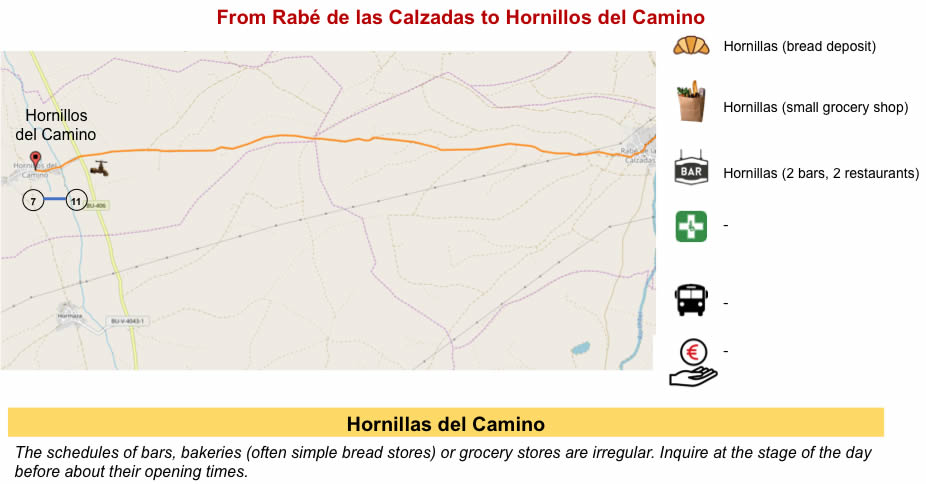

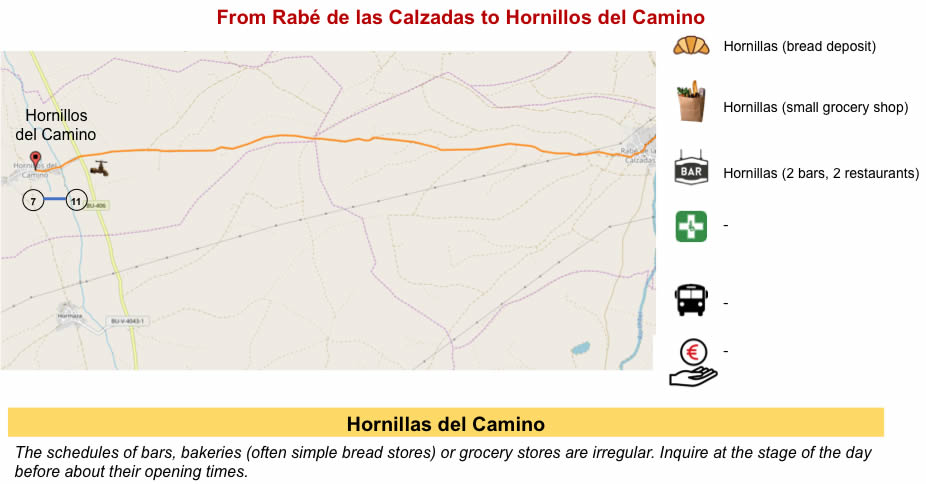

| The pathway soon slopes down to Hornillos del Camino, in the plain below. From here, you’ll see the big hangars where the agricultural infrastructures are stored. As everywhere in this region, no farm disturbs the great outdoors. The peasants all live in the villages, never outside. |

|

|

| The pathway, which has become a little stonier, slopes down, quite tough at the beginning, to almost 15% decline. Here, a farmer, with his 4×4 vehicle, will probably inspect his fields to estimate the work to be done in the flooded land. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope is gentle. Here, a Korean may be cast spells to claim the sun, or just makes simple exercises of relaxation of the shoulders. |

|

|

| Here is our sportsman on the way home with his dog. |

|

|

| The Camino gets to Hornillos del Camino. |

|

|

| It crosses Rio Hormazuela, where to consult the gauges, the water level can sometimes rise. |

|

|

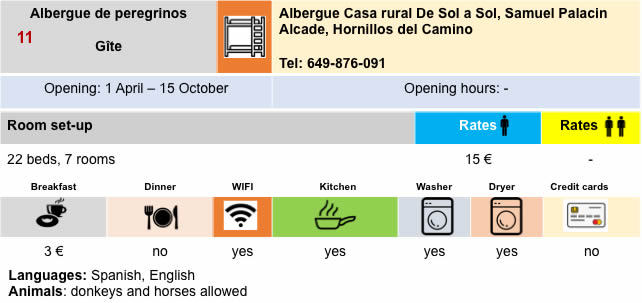

| The village is very long, with its stone houses and church. There is not much to do here, except spend the night at the hostel. Some pilgrims will go to Hontanas, the next village, the bravest to Castrojeriz. But to get there, it’s still almost 40 kilometers beyond Burgos.

Hornillos has less than a hundred year-round inhabitants, and no doubt the majority are just managing the flow of pilgrims. The village is documented for the first time in the IXth century, because the defensive line of the fortified towers of primitive Castile passed through it. This line of towers, built to contain the advancing Muslims, started from Burgos, passed through Tardajos and Rabé de las Calzadas, and reached Castrojeriz. The village is also mentioned in the Pilgrim’s Guide to the Codex Calixtinus. Hornillos means “small furnaces”, in which pottery and tiles were fired. Is it also to justify the legend or the historical truth that Charlemagne would have stopped here to bake bread for his army? Here too, during the High Middle Ages, the city had a monastery and three hospitals. Today they are all gone except for part of Santo Espiritu. The XIVth century Gothic Church of San Román was built on the site of an old fortress. The church is what remains of the old chapel of the monastery. |

|

|

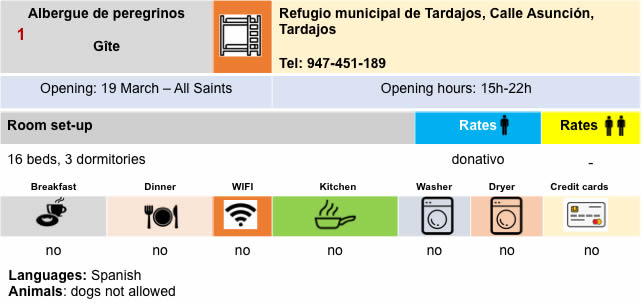

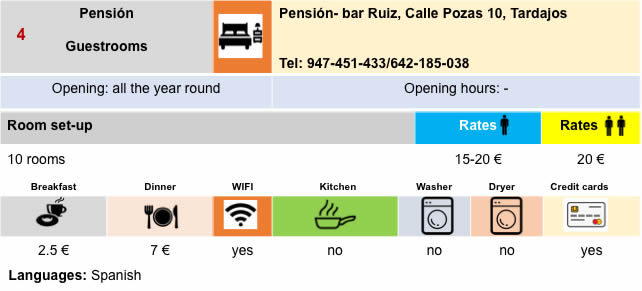

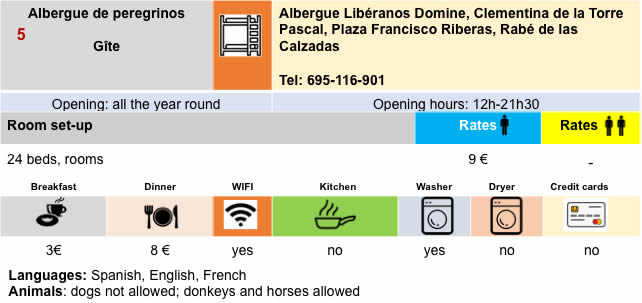

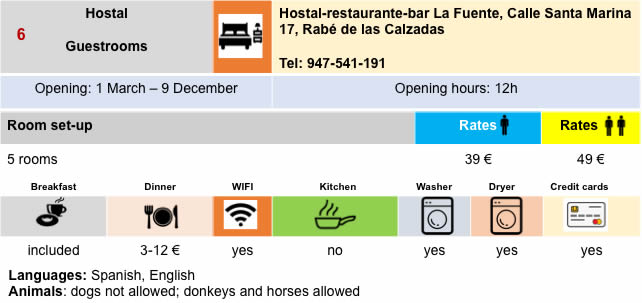

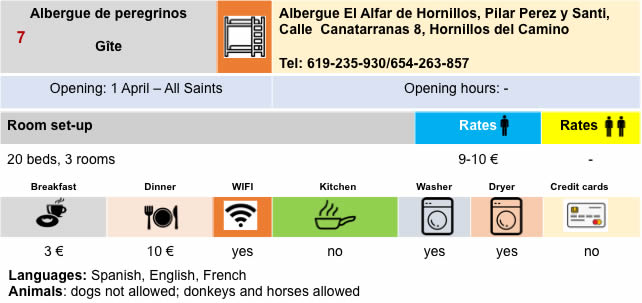

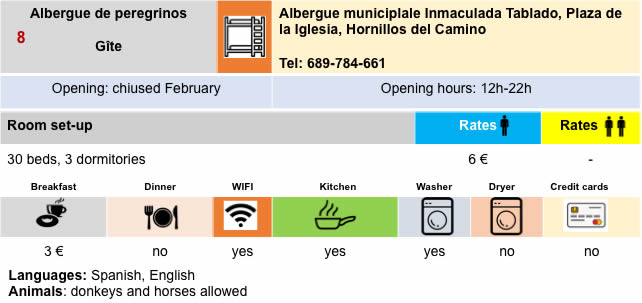

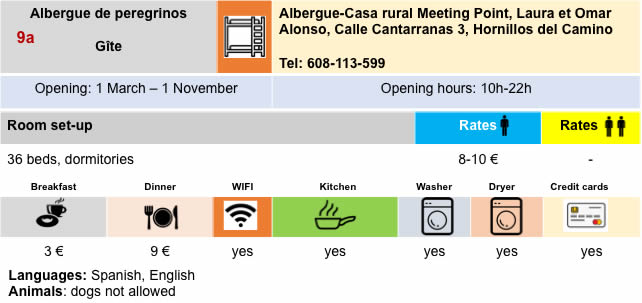

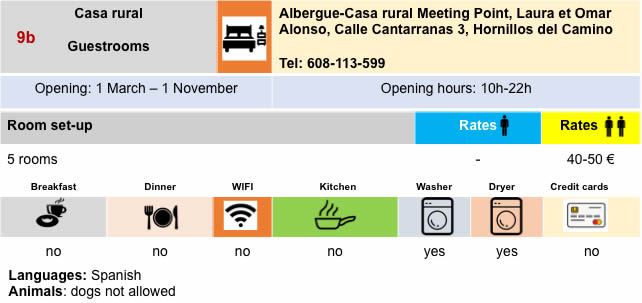

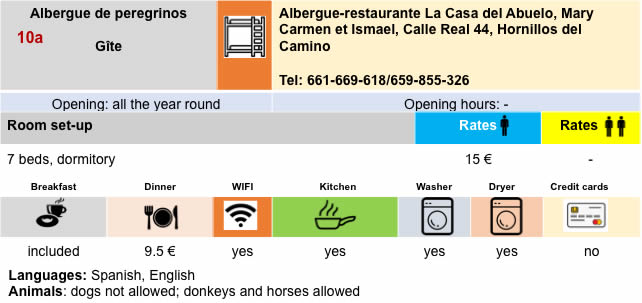

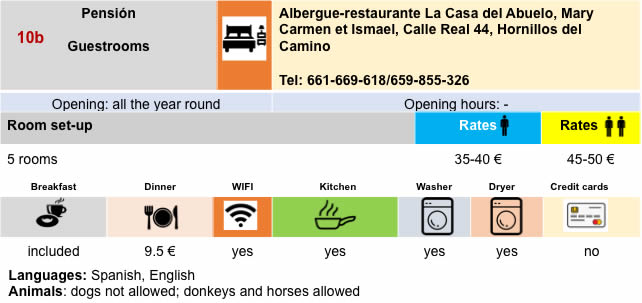

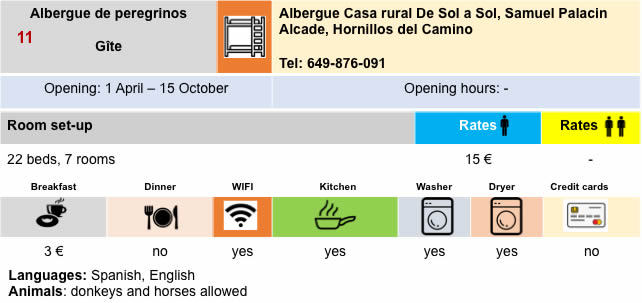

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 14: From Hornillas del Camino to Castrojeriz |

|

|

Back to menu |

In this stage, most of the journey takes again place on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

In this stage, most of the journey takes again place on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads: