In the solitude of the Meseta

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

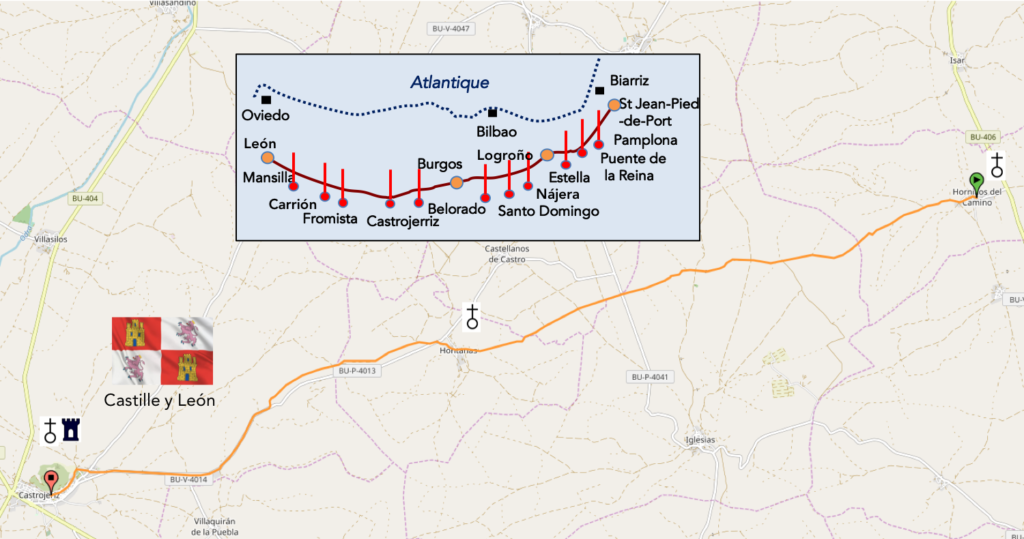

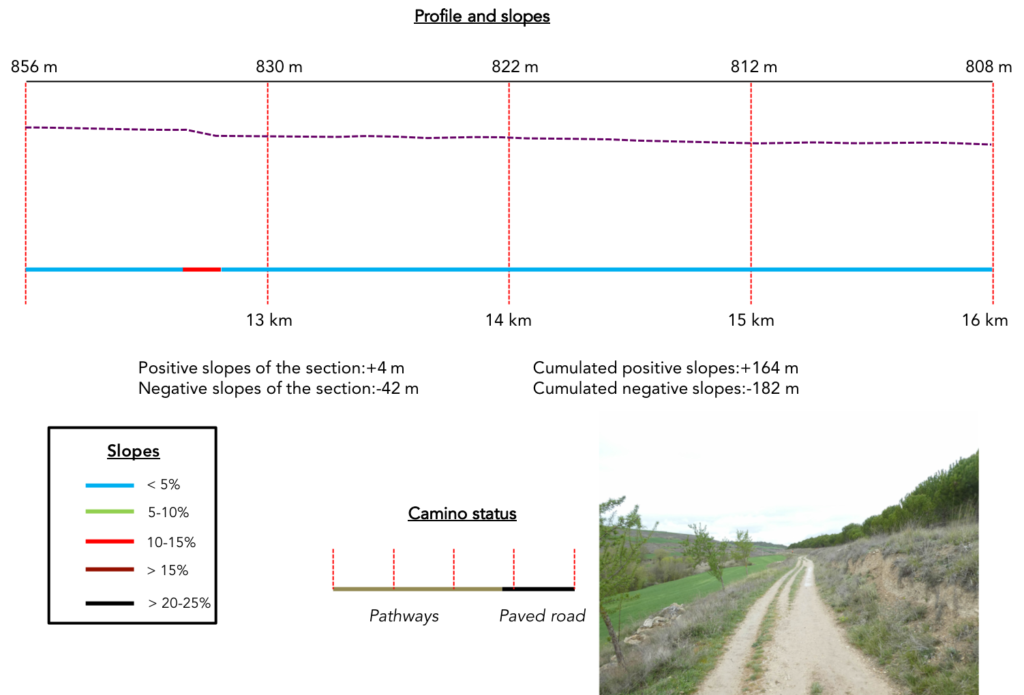

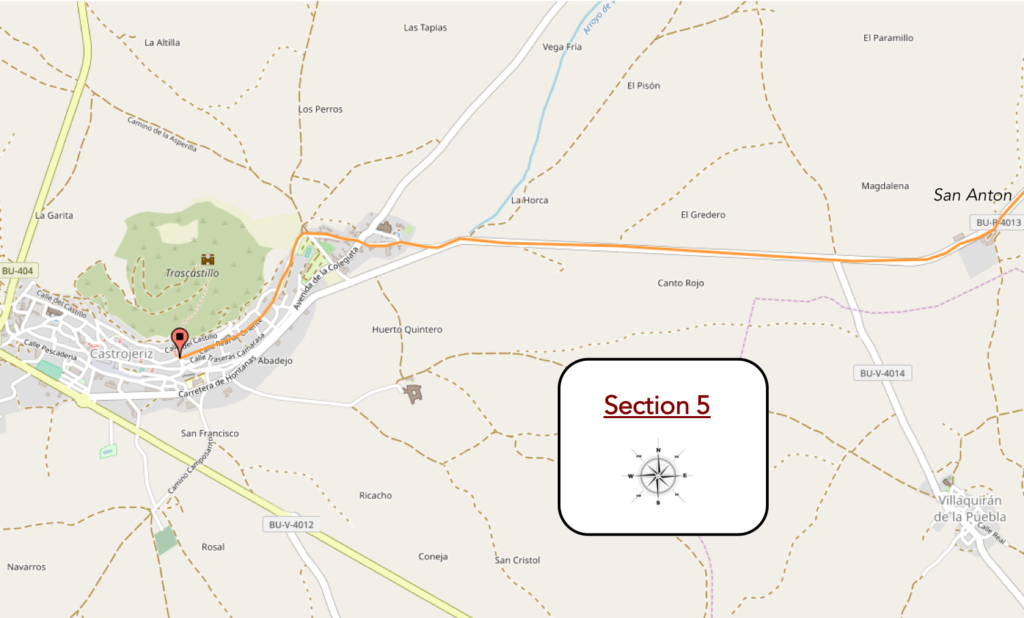

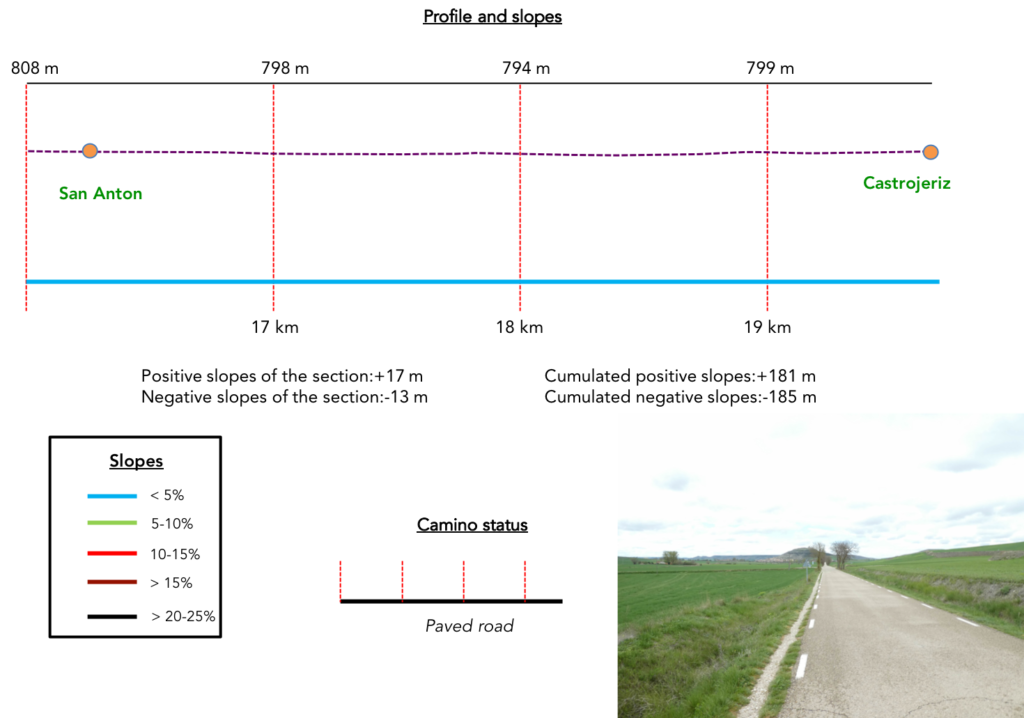

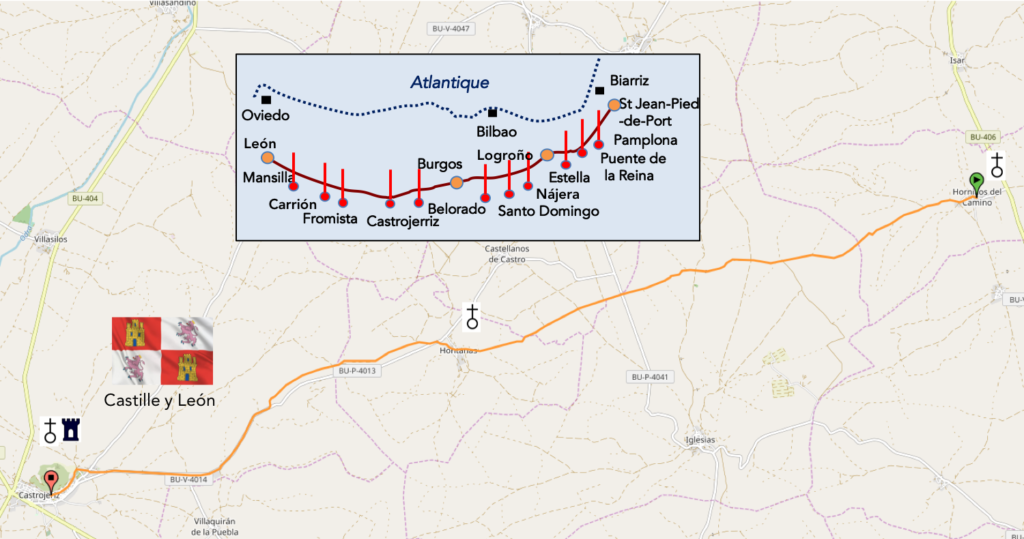

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-hornillos-del-camino-a-castrojeriz-par-le-camino-frances-33848222

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

It is often said that the first part of the way to Burgos is for the legs, simple mechanics well oiled. From Burgos to Astorga, everything is for the brain and the soul, total introspection. It is necessary to pass Astorga so that the spirit and the heart take the relay.

Because the Meseta is definitely a way of solitude, which must be furnished. The dirt road is sometimes red, sometimes ocher, sometimes white. Here, with time, they have torn down all the trees, removed the meadows and the sheep. In spring, everything is green cereals. In summer, everything is yellow with stubbles. Small villages, and there are so few, live out of time. So, moving forward, in a monotonous setting, unsurprisingly, if not sometimes a bush or a flower, is a real challenge that calls for an intense inner life. Some hate, others love it. Some enjoy a moment, then after hate it altogether. That’s life. You will have your own idea of this event. Now if you pass here like us in bad weather, you will understand that we have hardly any beautiful deserts to present to you. Too bad!

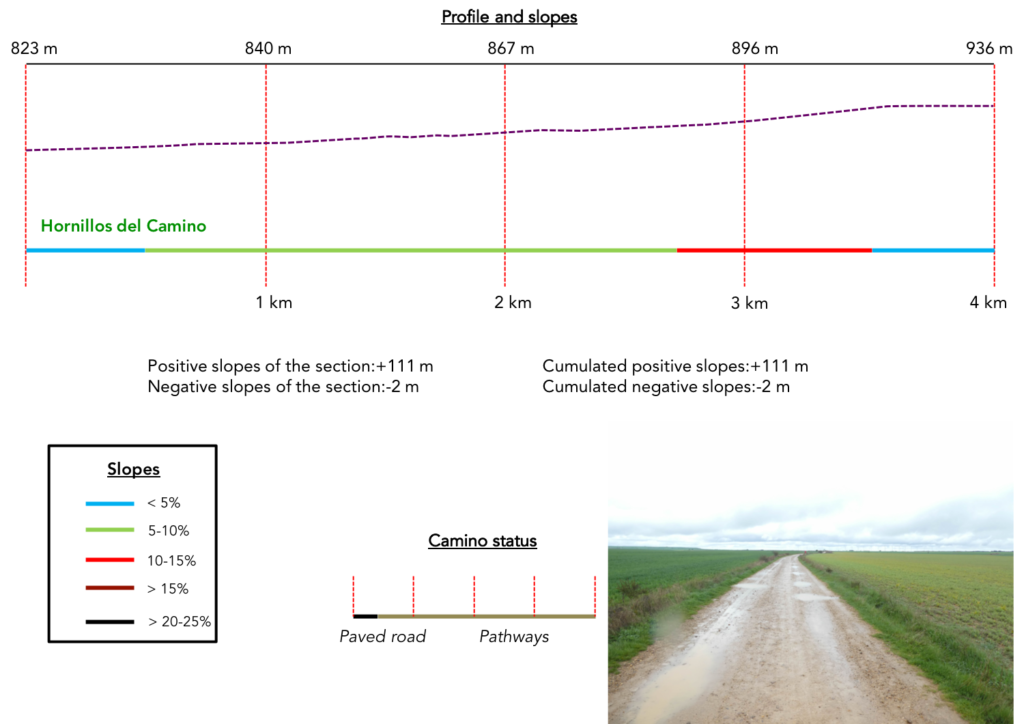

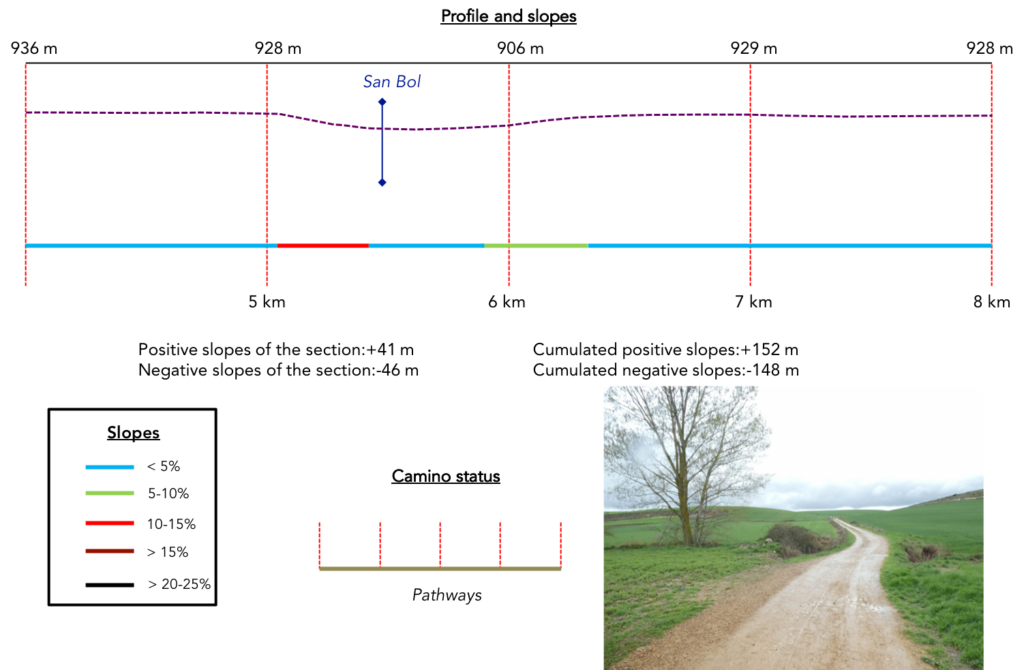

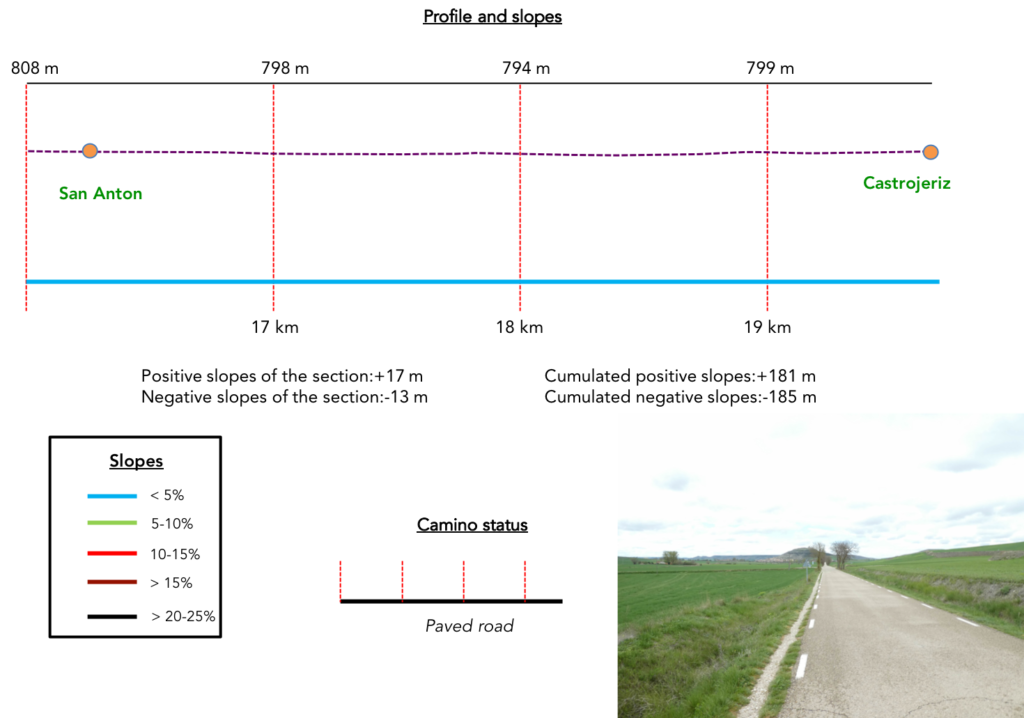

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the stage (+181 meters /-185 meters) are again insignificant. On the stage, there are only two or three small hills, uphill and downhill where the slope is around 15%. But for a very short time.

In this stage, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other paths of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on the pathways:

- Paved roads: 5.5 km

- Dirt roads: 14.1 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

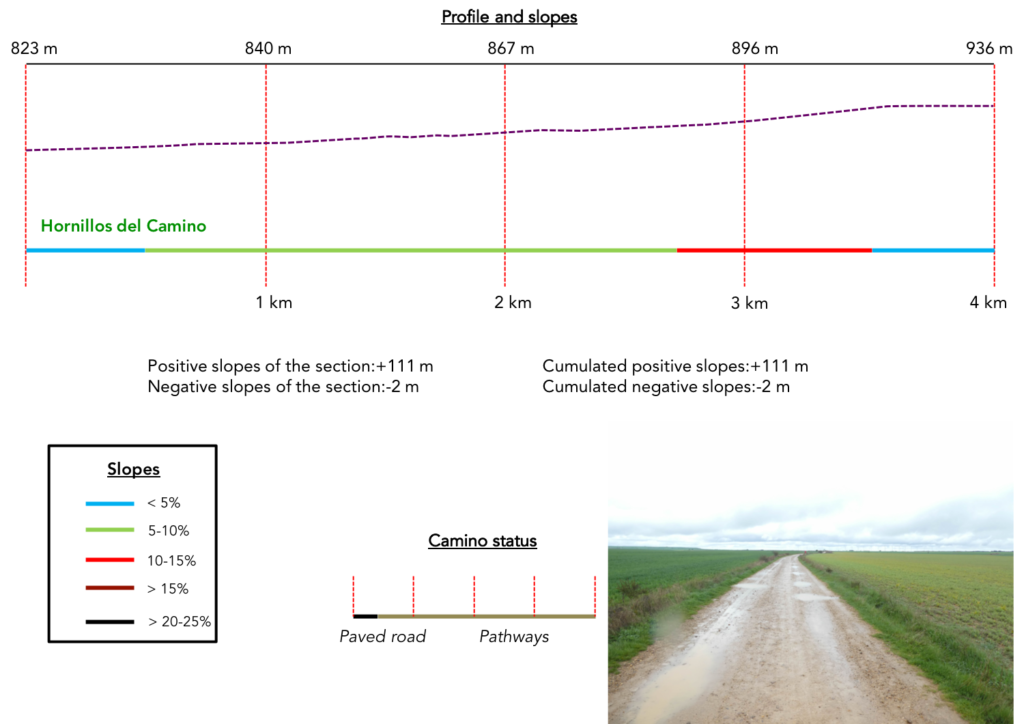

Section 1: The track slopes up back to the high plateau.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course in constant climb, most of the time quite soft.

| It has been raining since last night on the Meseta, and the rain will last again. But, as it’s said, the rain does not stop the pilgrim, right? At the exit of Hornillas del Camino, the pathway will climb on the high plateau. Here, you’ll still climb 100 meters over 4 kilometers. Today, we see almost nothing, so much rain pours.

We apologize for the poor quality of the images. That’s all we managed to salvage from the start of the stage. But you won’t lose anything now that you know the geography of the the Meseta well. |

|

|

| The Meseta is still just as vast with its cereal fields and land planted with green manure. Today, the wide dirt road is completely soggy. The mud sticks irreparably to the shoes, and you have to try to unstick them. |

|

|

| A fine rain and a howling wind lash the face and the ground is loaded with more and more water. Under the dripping pelerine, you can still see that the slope is not very steep. |

|

|

| Further up, the horizon opens up again, ever wider. We guess that the rain will perhaps stop. It is often like this in the Meseta in the rain. The weather is variable, even when it rains. We did many stages under morning downpours. Then, often, the rain finally stopped in the morning. You will tell me that all you have to do is check the weather forecast and leave later. Probably yes, but is the weather forecast really reliable? |

|

|

| After 3 kilometers of climbing, sometimes gentle, sometimes a little more demanding, the wet pathway arrives on the high plateau. Many puddles enamel the ungrateful land. You’ll stick this way and the thick mud will swallow your shoes. And to silence us, the rain immediately stops over a space that has become infinite. |

|

|

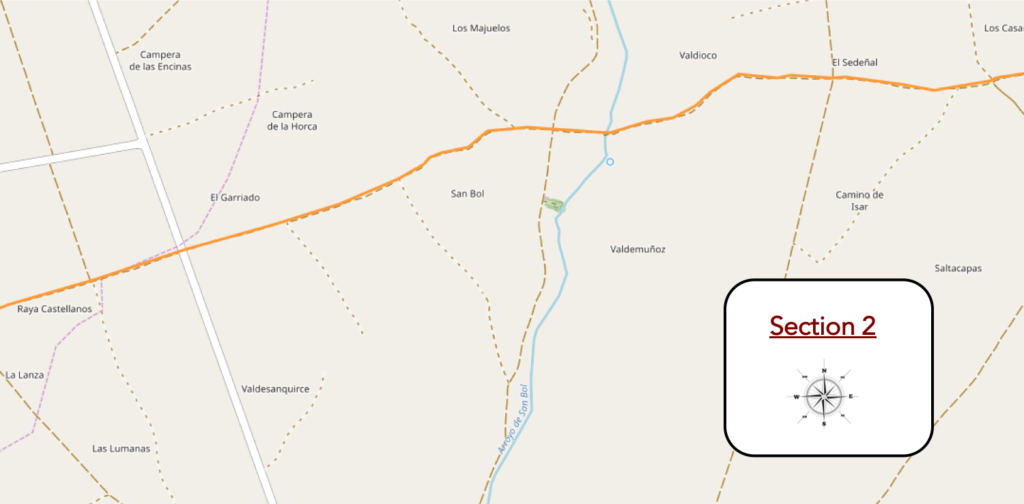

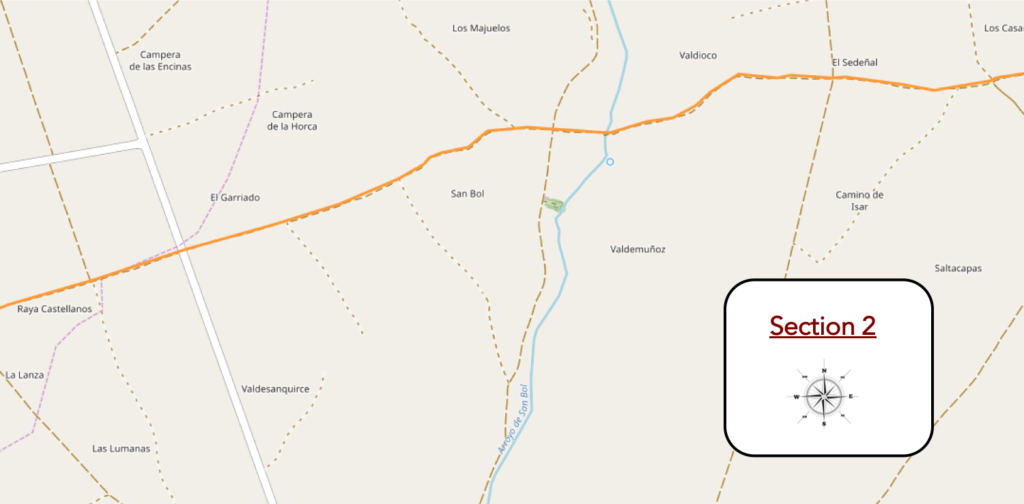

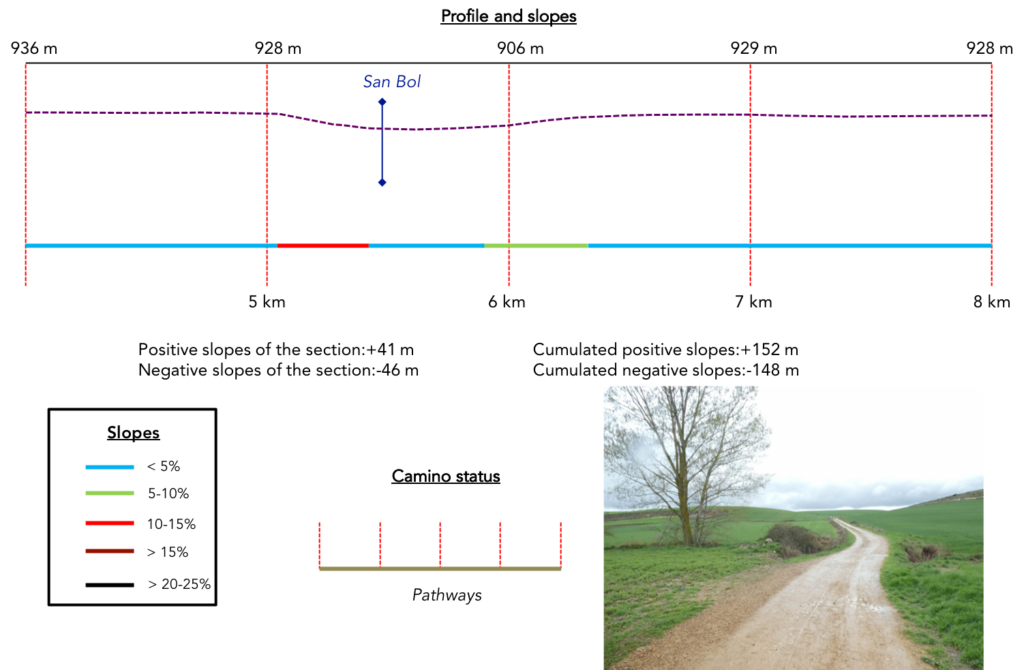

Section 2: Ups and downs in the Meseta.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

So, far below your feet, lies the majesty of this cereal desert. Further on, there are no more landmarks. There is only sky and earth, nothing vertical where the gaze can cling, and the pathway that flees away, straight. This opens up your imagination in this very little marked space, with a horizon constantly pushed back before your eyes.

At the end of the plateau, it’s even further, always further. Before your eyes, the pathway fades to the horizon.

The desert is like a big book open on the infinite, whether it is green like here or covered with dunes. It almost always arouses in most of us a real fascination, being at the same time a source of wonder and questioning, a total confrontation with an absolute of fear and freedom. Our mind wanders towards a horizon that never ends. The Meseta scrolls, offering a breathtaking majesty, a world almost enchanted. You feel a bit like the Little Prince of St Exupery who was ecstatic at the beauty of the desert. Contrary to what many people imagine, agoraphobia is not the fear of the crowd. It’s more the opposite, the fear of emptiness, an anxiety related to places from where it might be difficult to escape in case of panic. Many pilgrims testify to this state of mind by crossing such places. Moreover, it is only to see winding the pathway in front of you in an ever-wider horizon. Fortunately for worried people, there are always some pilgrims in front of or behind you.

| Moreover, for those people worried about too open spaces, “albergue”are announced at reasonable distances. The pathway then gradually slopes down from the high plateau. Here, the slope is a little more pronounced. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope lessens and the pathway nods in the fields. |

|

|

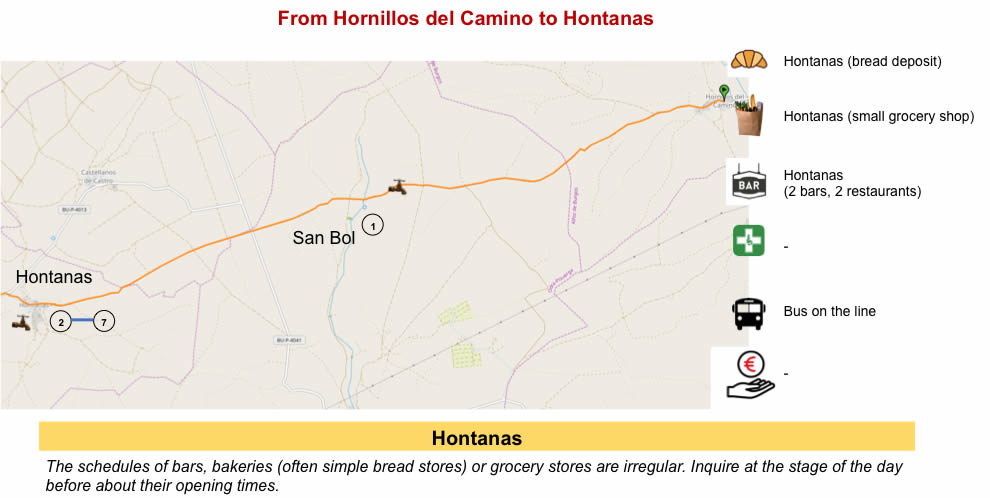

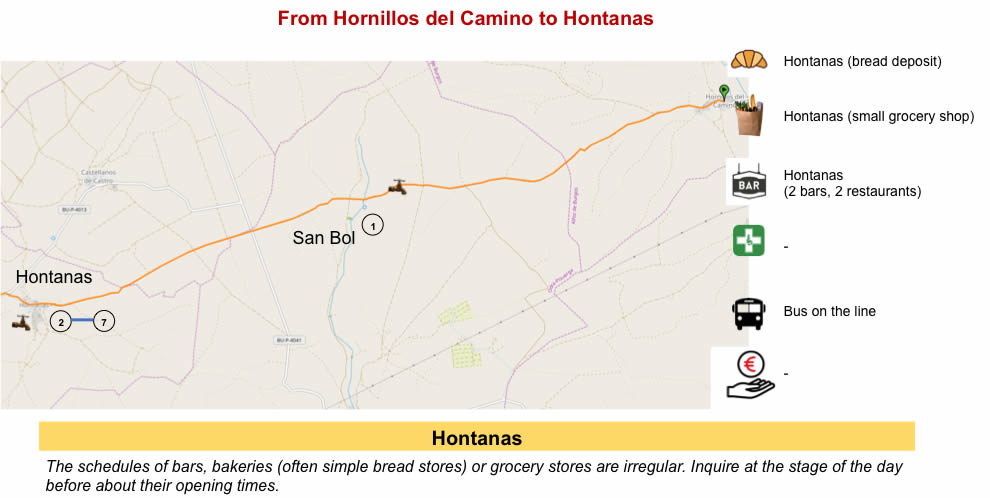

| You were told the “albergue” of San Bol 800 meters away. But that’s just an illusion. Here, it is only the road that takes you there. Considering the surrounding landscape, the village is not close, and no one tells you if San Bol is closer than Hontanas, 5 kilometers from here. In the valley called Arroyo San Bol, there was once a hamlet called San Baudilo, and during the XIVth and XVth centuries there was a hospital for pilgrims and a monastery run by the Antonine monks. For some unknown reason, the hamlet was abandoned at the beginning of the XVIth century. There is no trace left, except for a small “albergue”. |

|

|

| The wide dirt road, which is almost sand or clay here, then gently slopes uphill to the plateau, in cereals, sometimes with small limestone walls, which you do not know if they are natural or artificial, created during the fieldwork. |

|

|

| When you raise your head, your gaze naturally focuses on the distance, here constantly renewed, always the same. And the distance is far ahead of you, that’s its raison d’être. And the fields parade again, immense, infinite, on both sides of the road… |

|

|

| …until you cross a small paved road, which must please tractors. At this time, you do not see any work in the fields. You should know that spring wheat is planted in the fall and that there is not much to do before the wheat sprouts and that you then have to work a little with Syngenta and the other companies in the same hair, for their magnificent miasmas of pesticides. Path 1 of the road to Portugal still accompanies you. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway crosses an area that becomes a real treat for the walker in rainy weather. Here, you must find grassy areas to put your soles or wade in the slush. Soils are most often a mixture of sand, silt and clay, and their permeability depends on their respective percentages. The more sand and silt, the more soil absorbs water. But when the balance leans towards the clay, quite compact and impervious, the water remains on the surface and is poorly absorbed. |

|

|

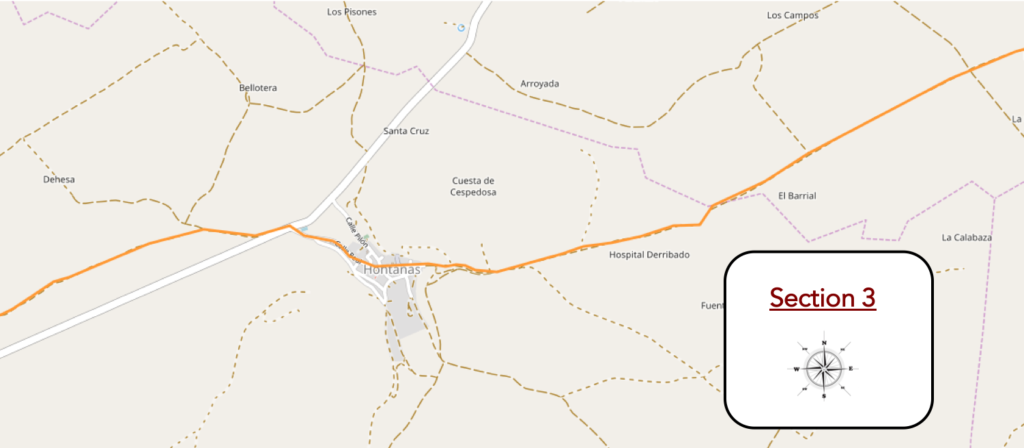

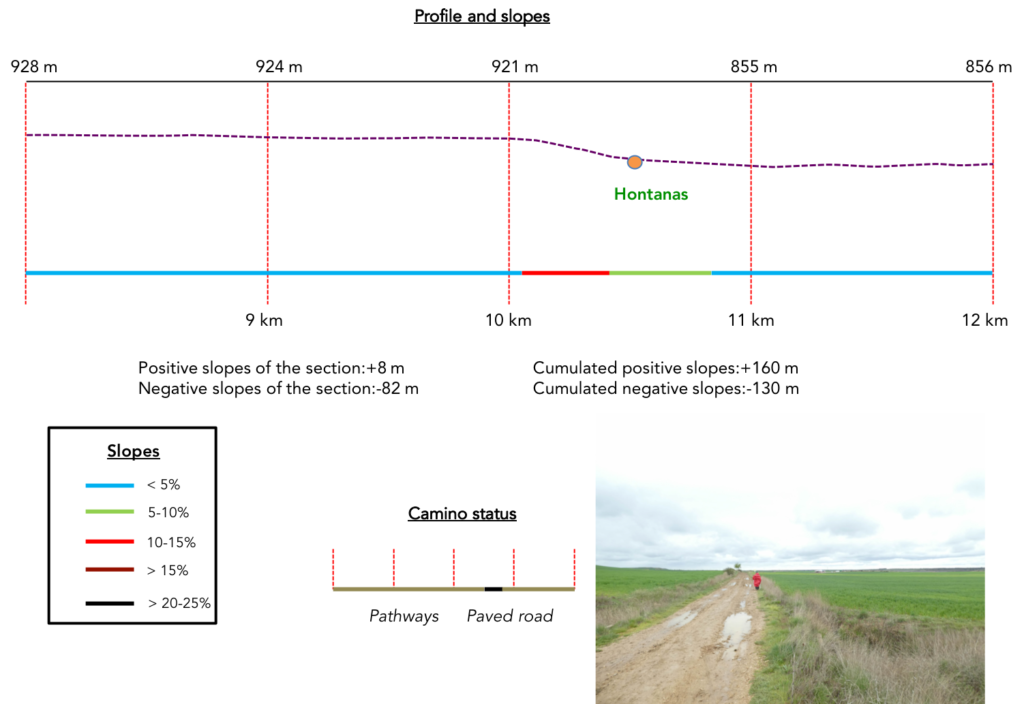

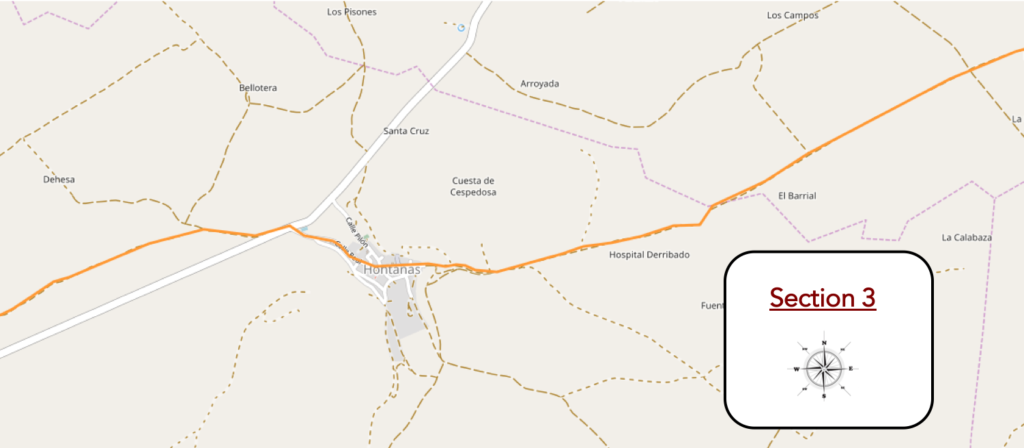

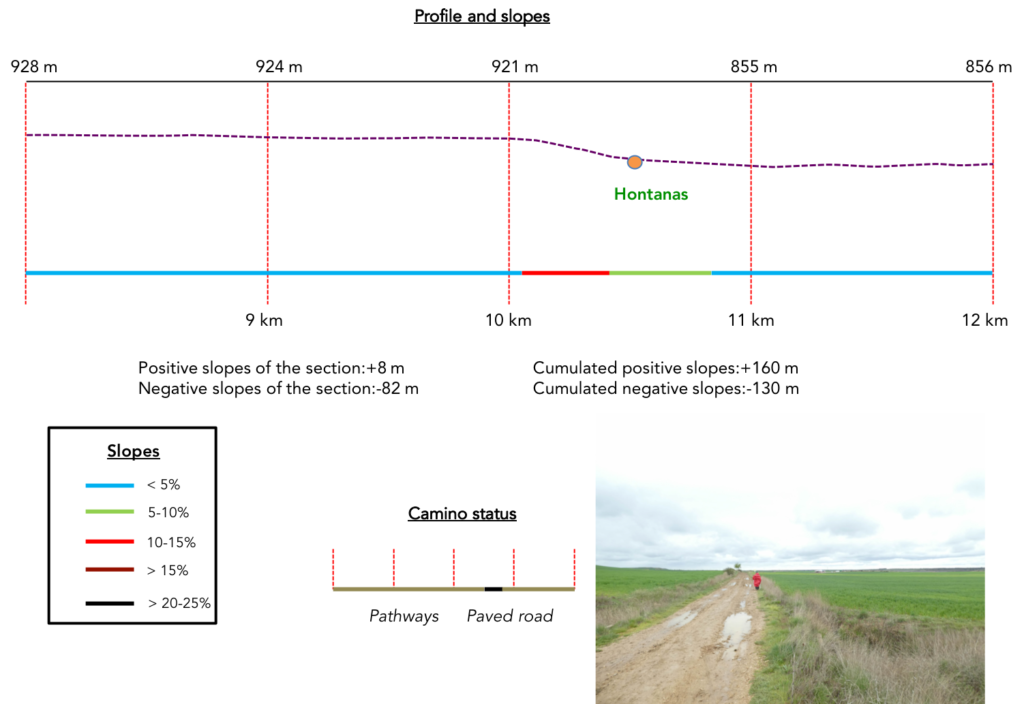

Section 3: Passing through Hontanas.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| This crossing here on the Meseta is gentle today, even pleasant, apart from the stubborn mud, because here the pathway avoids advancing parallel to the road, as it will do, alas almost on every occasion, in the later stages. So, you pay attention to unimportant details. You have to fill the void. In front of you, a pilgrim, traveling alone, somehow avoids puddles and sticky mud. She’s not moving fast. You see her red cape is getting closer in front of you. |

|

|

| The first billboards appear at the edge of the road. In this “albergue” they will offer you the happiness, the total, the Wiki, the bike garage, the dog kennel, the washing machine. You can even pay with the Visa card. Well, isn’t this rich? |

|

|

| And the pathway runs thus, monotonous and always so grandiose, probably also often in the mud of spring. Here, perhaps people build a new “albergue”, before arriving at Hontanas. The first accommodations are always best served, as pilgrims are reluctant to go further, especially if they have not booked in advance. On Camino Frances, many “albergue” do not favor bookings. But in the spring, there is room for everyone. In season, when the Camino is full, there may be a tighter competition between pilgrims to find room, in areas like this where housing is more restricted. So, some leave earlier in the morning, so as not to have to sleep out in the open. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the mud fades, almost like a miracle, when the pathway gets towards the end of the high plateau. On the detailed maps of the region, there are many places, probably corresponding to whole regions of cultures, which say something to the peasants. But for the pilgrim, there are only fields from one village to another, and the villages are not legion. Far from there! |

|

|

| The village is not far, to see the advertising that appears. Take your pick, if you haven’t booked. |

|

|

| And precisely there appears a village, which is discovered only suddenly at the sight, just below the end of the high plateau. |

|

|

| The slope is quite marked, between 10% and 15% to reach Hontanas on a stony pathway, nestled and compact in the bottom of a dale. It looks like a real jewel, beautiful like a sugar candy. |

|

|

| Along the way, you’ll find a small hermitage, as big as a handkerchief, dedicated to St. Brigitte. A slightly kitsch statue of the saint is nestled in a niche. |

|

|

| Many pilgrims spend the night here, in this charming stone village around its church, the church of the Immaculate Conception, built in Gothic style, in the XIVth century, amended with time. Hontanas means fountains, and you understand why such a place has developed since the Middle Ages, where there was already here a hospital for pilgrims. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the village, and soon after, it runs, today, in the mud and puddles of the pathway. |

|

|

| Here, you walk in a dale, parallel to the road that goes to Castrojeriz. As far we are concerned, we have almost forgotten now the Koreans who have melted into the nature and the mud of the road. You do not even hear any more about American people, it’s saying that the Meseta is a great desert. |

|

|

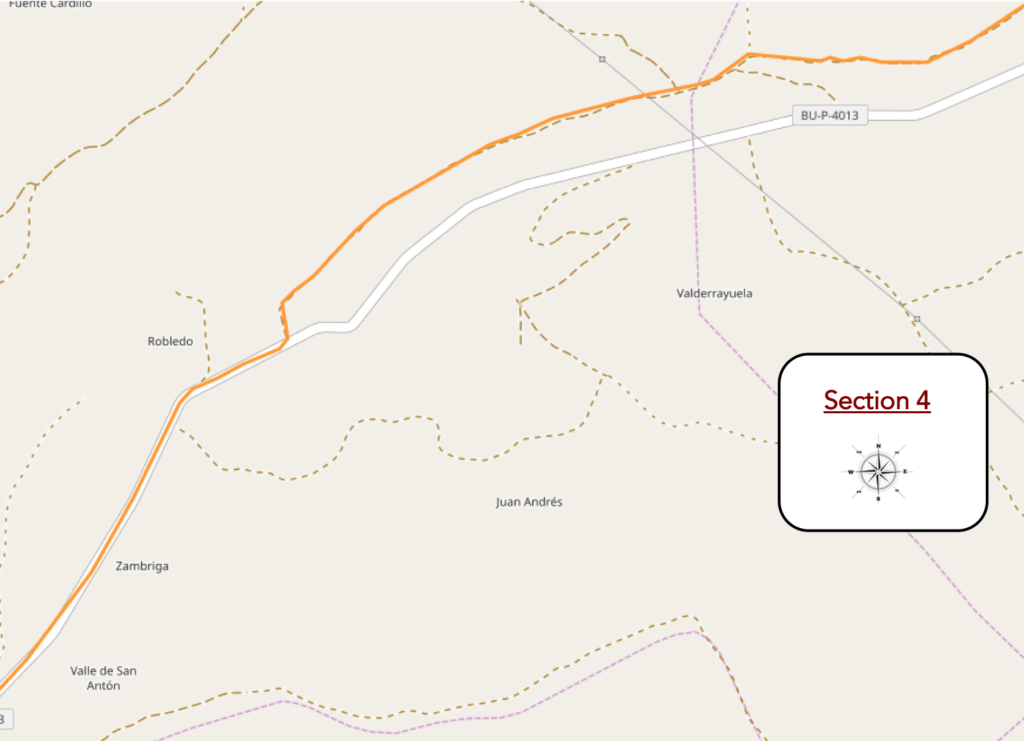

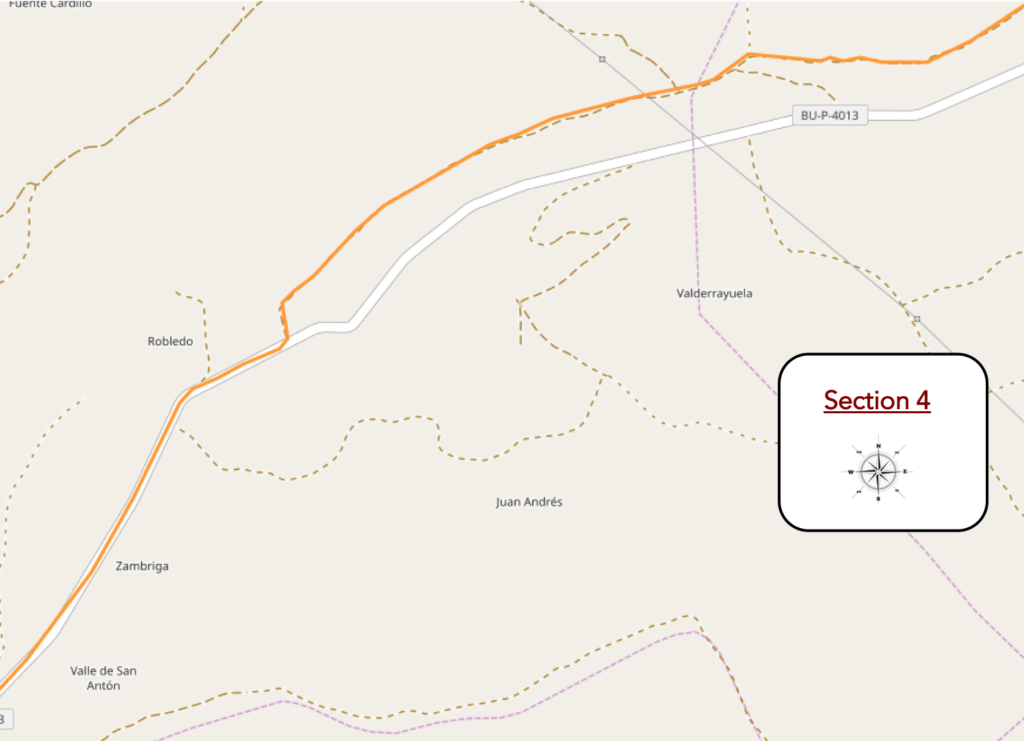

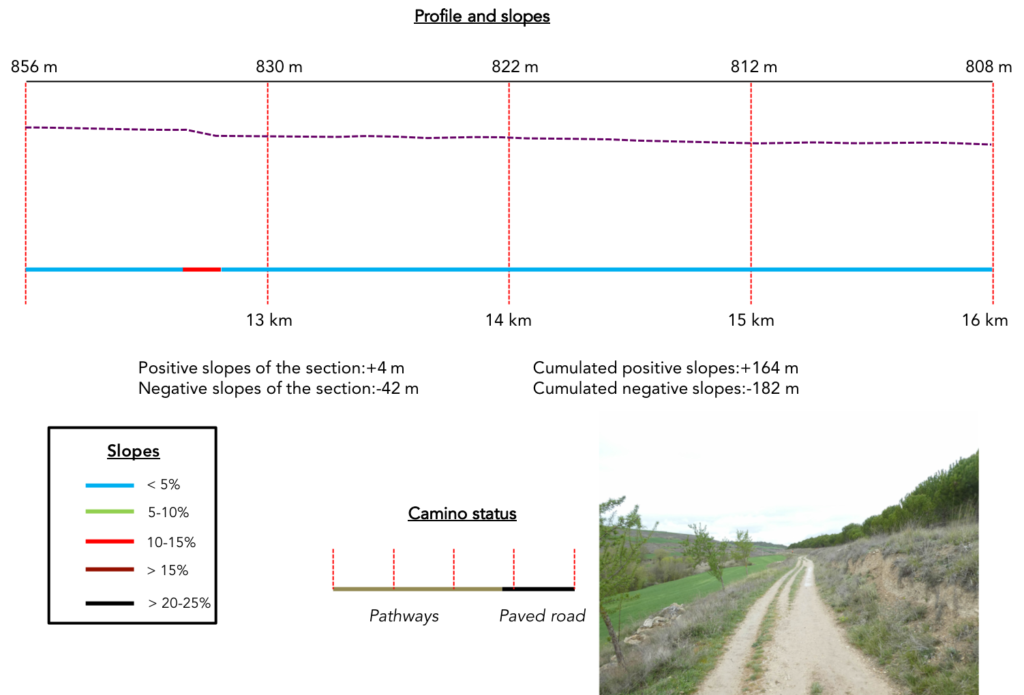

Section 4 : In the Garbanzuelo dale.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| In the Garbanzuelo dale that leads to Castrojeriz, the landscape is more contrasted than before. The huge wheat fields gave way to smaller fields interspersed with moorland and small pine groves. |

|

|

| It is most often a common, worn downhill pathway on a hillside. Sometimes walls sit along the pathway lined with brambles and dry grass. We will not say that it is the most attractive landscape of the the Meseta. |

|

|

| Further on, the mud is back today on the track. The most intrepid pilgrims flounder, with joy or resignation, in the slush, the less courageous take the edges of the fields to avoid getting bogged down. |

|

|

| In this sad landscape, and difficult in bad weather, even advertising for accommodation will not bring smiles to walkers. |

|

|

| The pathway will evolve like this for kilometers between the wheat fields and the bare hill, on the almost dry ground or the mud. In this valley that stretches endlessly and sinks who knows how far, psychological and physical endurance is put to the test and often leads to boredom. Here, even in good weather, it does not say to be a route to arouse the enthusiasm of its visitors. |

|

|

| Further on, it is compact mud, and the foot advances as much as it retreats. Fortunately, today you can see the end of the race. |

|

|

| After this (today) acrobatic gymkhana, the Camino quietly reaches the paved road that leads to Castrojeriz. |

|

|

| Then, for more than a kilometer, the pilgrims will follow the road or the grassy strip, at their choice, under the willows and the black poplars. |

|

|

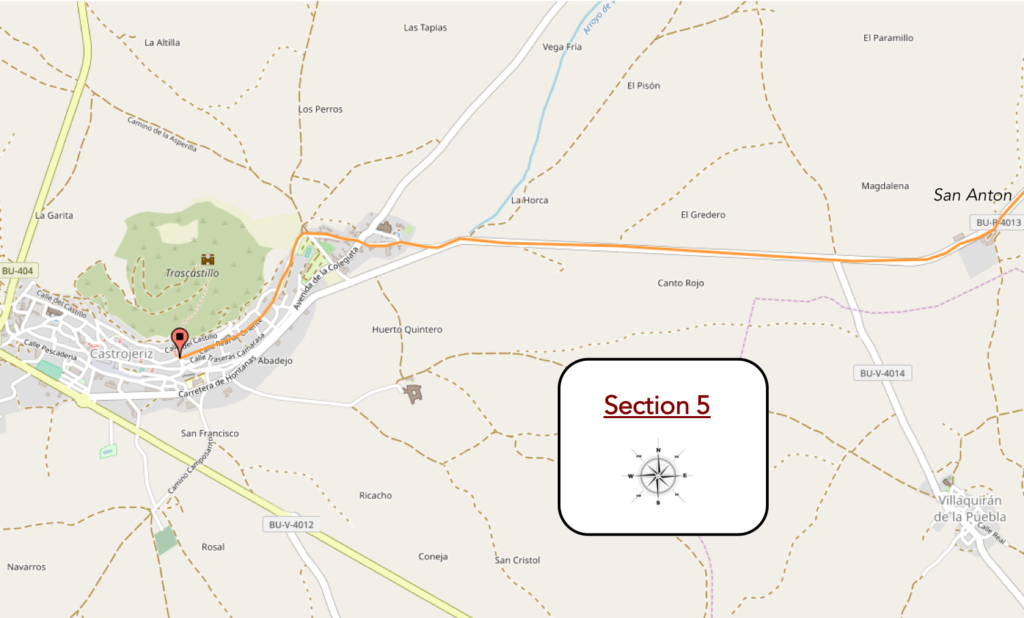

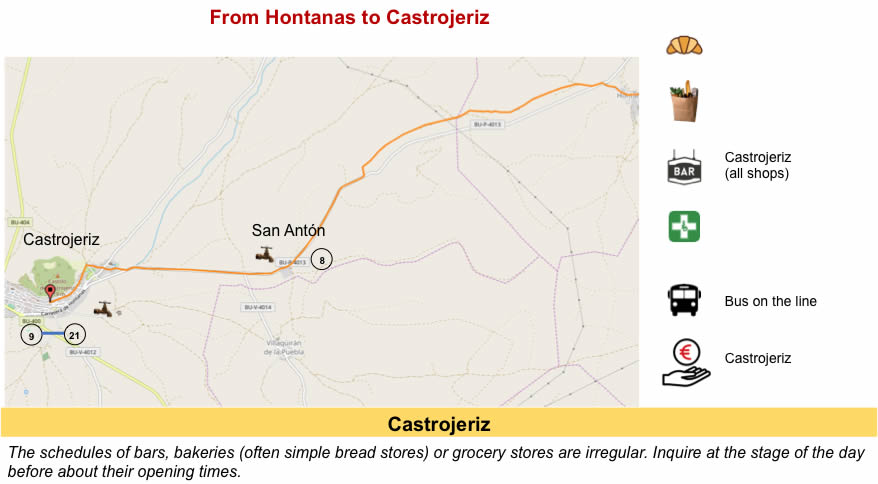

Section 5: On the road to Castrojeriz.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

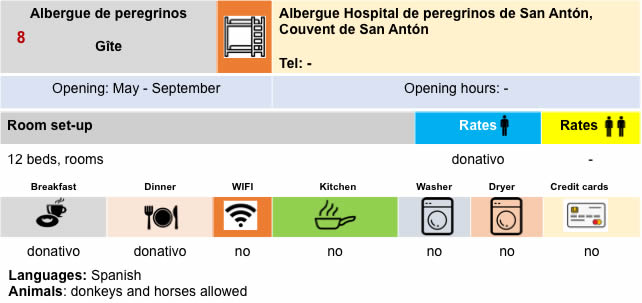

| At the bend in the road appears the monastery of San Anton, or at least what remains. The monastery dates back to the XIIth century, but the current Gothic ruins date mainly from the XIVth and XVth centuries, and the arch dates from the XVIth century. The decline of the monastery began in the XVIIIth century, until it was definitively abandoned and became private property at the end of the XVIIIth century. All this coincides with the evolution of the Antonine Order. The Order was founded in 1095, then sanctioned as a monastic order in 1218 and as a religious order in 1248. In the XIXth century, the very small congregation was canonically attached to the Order of Malta. In Spain, the Order was extinguished by a papal bull in 1791, dividing its assets and revenues between hospitals, local churches and town halls. |

|

|

| The road passes under the vaults of the arches of the portico. There remains a part of the church with three naves, but the monastery had a hospital in the Middle Ages. It was the former monastery and hospice of the Antonine Order, founded in France as a tribute to Saint Anthony of Egypt (San Antón Abad), patron saint of animals, usually represented with a pig at his feet. The sacred symbol of the order was the T-shaped cross known as Tau, the 19th letter of the Greek alphabet and symbolizing divine protection against evil and disease. In fact, the Antonins, we have already met them on the roads to Compostela in Isère and in the Gers, in France. The Antonins devoted themselves to the care of the sick who walked on the Way of Compostela. They had specialized in treating pilgrims with “St Anthony’s fire”, a disease caused by the fungus, ergot, which caused a burning sensation inside the body of its victims. This scourge, whose appearance is documented in the Xth century, reached epidemic proportions from the XIth to the XIVth century. The monks also treated pilgrims suffering from swine fever. This is why San Antón is represented in iconography by fire and with a pig by his side

Saint Anthony the Great (circa 251-356 AD), also known as Anthony of Egypt, San Antón Abad, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony of Thebes, Abba Antonius, or Father of All Monks, was a Christian saint from Egypt. He is often mistakenly considered the first monk, but there were many ascetics before him. However, they generally became hermits. Anthony the Great was the first of them to launch a spontaneous monastic religious movement. Although Antony himself lived in solitude and did not attempt to organize or establish a monastery, a community grew up around him based on his example of ascetic and secluded life. Around 305, after having lived in total solitude for twenty years, Antony came out of retirement and then devoted himself to the instruction and organization of the large body of monks that had formed around him. His rule represented one of the first attempts to codify the guidelines of monastic life. Then he retired again to the desert between the Nile and the Red Sea, where he spent his last 45 years. |

|

|

| Further afield, the road leaves under the black poplars. Quickly, you’ll see Castrojeriz in the distance under a hill. |

|

|

| The borough seems close. Challenge yourself, because there are nearly 3 kilometers to go. You will have plenty of time to see rising the hill and its castle perched on the hill in front of you. This kind of journey never provokes enthusiasm for the pilgrim, but it gives time to rub the muddy shoes, to unravel them in the grass, while walking on the grassy strip of roadside. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| At the beginning of the city stands Nuestra Señora del Manzano (Our Lady of the Apple Tree), the former collegiate church of Santa María del Manzano, outside what remains of the old city walls. It is the oldest religious building in Castrojeriz, whose origins date back perhaps to the IXth century. Formerly, it had the rank of collegiate, in other words an important church with a chapter, without being a cathedral. From the XIth to the XIIth centuries, it was renamed an abbey. The construction of this imposing and magnificent current building, with three naves, began at the beginning of the XIIIth century in an ogival Romanesque style, a late Romanesque style of transition with Gothic vaults. Then, there were many transformations during the following centuries, and the building evolved more and more towards the baroque. The gable was added in the XVIIIth century. Legend says that as St James passed by, he saw an image of the Virgin in an apple tree. He was so excited that he fell heavily on his horse, leaving behind hoof prints which can be seen embedded in the rock just outside the south door of the church. |

|

|

| When we passed through this property declared of Cultural Interest in 1974, we found the door closed. Surprise? Not really. Then, the altarpieces, the chapels, the paintings and the tombs of the illustrious local characters, you can put a cross on them. |

|

|

On the other hand, if you like kitsch, then here is a gift for you. Very tasteful, of course. The culture, it doesn’t matter, but the bed and the food, yes.

Above the collegiate church stand the ruins of the castle. The ruins are the oldest in Castrojeriz, as many peoples have passed through here. There has been a village in this area since Celtic times. Then it was a Roman city, possibly founded by Julius Caesar, using this vantage point to protect the route to their gold mines near Astorga. Some say that the castle was built by the Visigoth king Sigerici in the IXth century, thus called Castro Sigerici or Castrojeriz, hence the name of the city. The city was subsequently the scene of numerous battles between Christians and Moors in the IXth and Xth centuries. It rose to prominence during the Reconquista, that period of the Middle Ages when Christians took back the lands from the Muslims, a long period from the VIIth century to the XVth century, when the Catholic kings took back Granada, the last bastion, from the Muslims. Here, the castle and the fortresses became a stone quarry in the XVIIIth century. The current ruins are the result of the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. The hill below the castle is honeycombed with tunnels containing bodegas built to keep wine cool.

Castrojeriz (800 inhabitants) does not really have a center. It is a succession of parallel roads that crisscross the town endlessly, a succession of more recent or old houses, where stone and brick mingle. Castrojeriz is the last place of the Camino in the province of Burgos. It then developed a street, which is still the longest of the Way of Compostela, nearly 2 kilometers between the road and the hill. It takes a good half hour to cover its length. For this reason, it is also rightly called “the long city”. But, there is not just one street. In fact, there are 3 streets that run the length of the city, with perpendicular junctions, often by small stairs.

| When you come from Nuestra Señora del Manzano and follow the signposted Way of Compostela, you will quickly climb the upper street, the longest. The whole village is paved, with irregular flagstones, often hampering regular walking, but with a more comfortable central flagstone. The European deniers must have also circulated here. |

|

|

| Further up, you will then arrive at the Church of Santo Domingo. |

|

|

| This solid XVth century church is best known for its skulls or stylized crosses that adorn the facade. |

|

|

| Further on, the road reaches Fuero Square, a gentle esplanade that overlooks the plain below. |

|

|

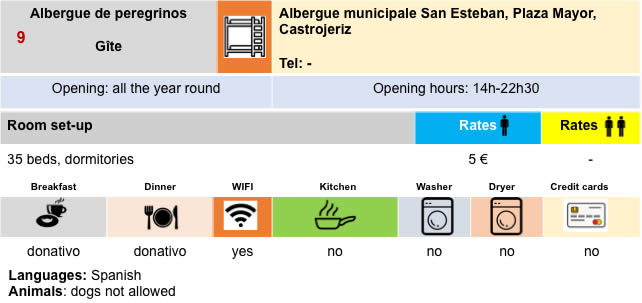

| It was the advent of the Camino de Santiago in the Middle Ages that brought Castrojeriz its prosperity. The Way of Saint James opened up to pilgrims who arrived here en masse. At one time, there were up to seven “hospitals” here to accommodate pilgrims, more than six churches and three convents. There is even a church that has become an “albergue. Shortly after, you will be near the top of the village at the Plaza Mayor. Admittedly, it is the center, but is there really a center in this complex village? It is not here that the restaurants or the shops are grouped. These are distributed in the 3 busy streets. You often have to travel from one street to another to find what you are looking for, especially the few accommodations or hostels. |

|

|

| Beyond the Plaza Mayor, the narrow street heads towards the San Juan church, also on the heights of the village. You may have sometimes the feeling that not all the houses are inhabited. |

|

|

| The Church of San Juan is a Gothic building dating back to the XIIIth century, with the appearance of a fortress. It has three naves and three apses, round pillars and ribbed vaults. The apse and the tower seem to be the work of the first decades of the XIIIth century. The building was subsequently restored in the XVth and XVIth centuries. |

|

|

| If the building is clearly Gothic, the statues and the altars have rather a Baroque air. There is also an adjoining cloister also originally dating back to the XIIIth century, later transformed. |

|

|

| At the level of the church, it is almost the end of the village, it is here that you will pass the next day. But, if you are staying on the other side of the village, you will have to cross the village for a long time to get here. So, to help you, just behind the church, the Camino finds a fountain and goes out of the village in road intersections. |

|

|

| Pilgrims must organize their leisure, often disembarking in the early afternoon at the end of the stages. And the day is long, very long until the evening meal. So, after the bar, the ablutions, the little laundry, the siesta, they wander the streets in search of a possible surprise. So here, in Castrojeriz, there is the choice to redo an entire stage, just by turning in the 3 parallel streets of the village. In one of the lower streets, you will find an oversized square where several regiments could be stored. |

|

|

| A monument to the pilgrim watches over the destiny of the square. |

|

|

| And then, by juggling from one street to another by the stairs, you can get an idea of what is still inhabited in this sprawling village. |

|

|

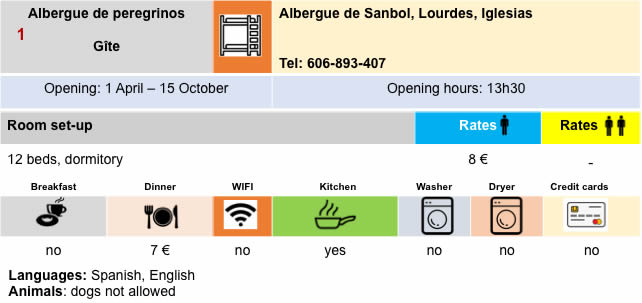

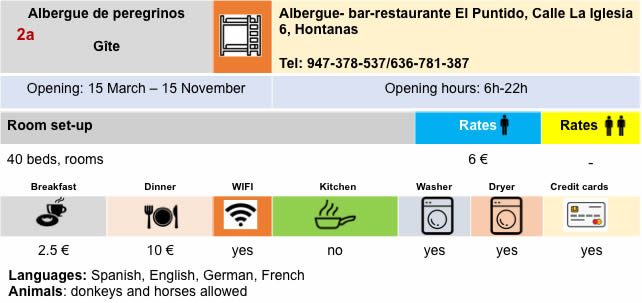

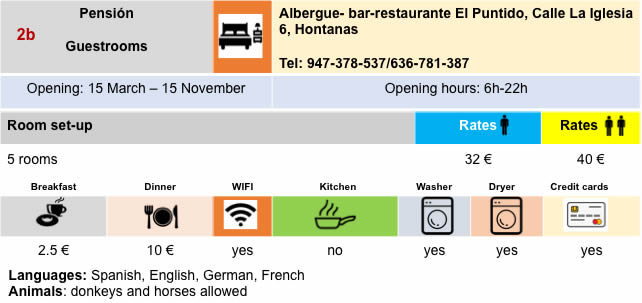

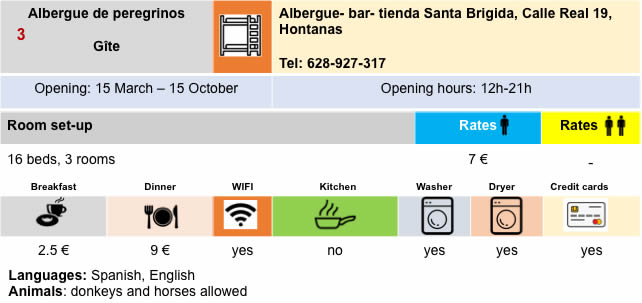

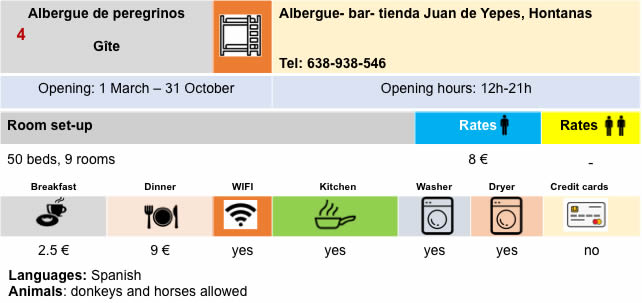

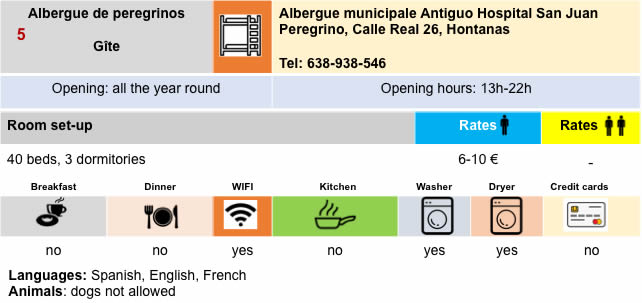

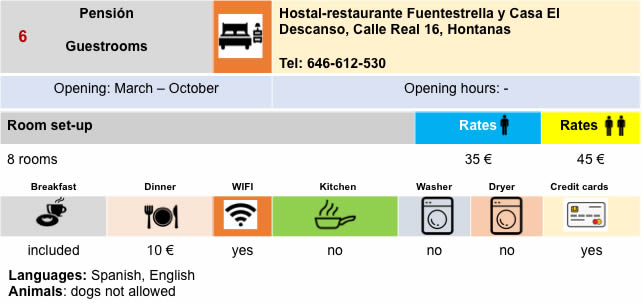

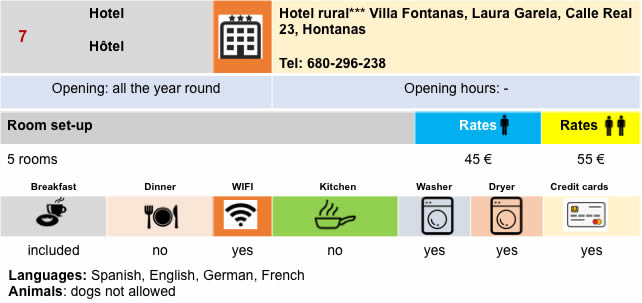

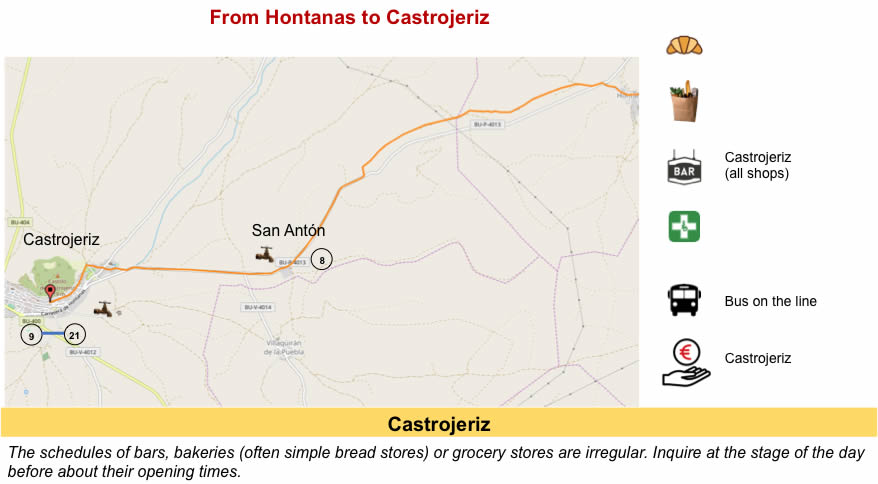

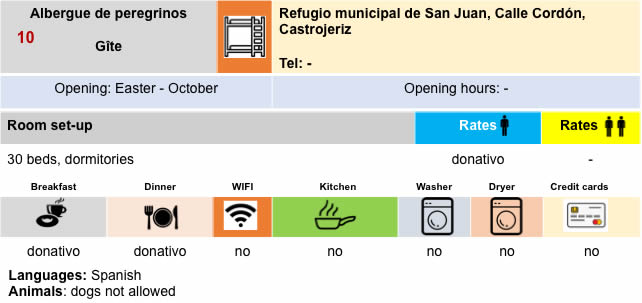

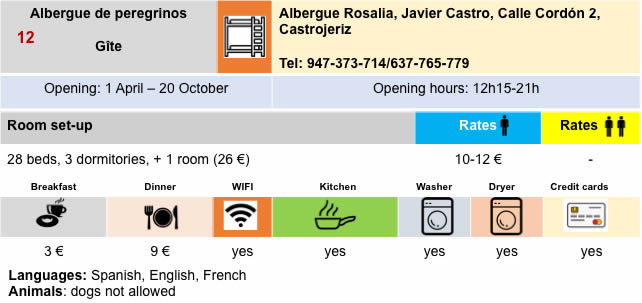

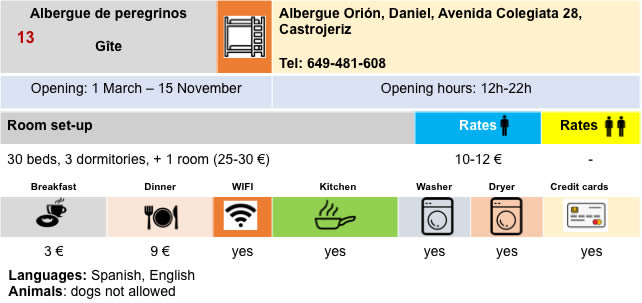

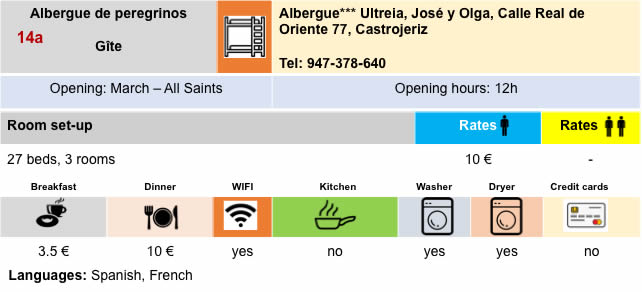

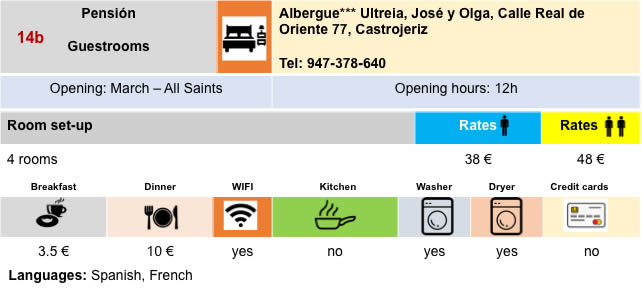

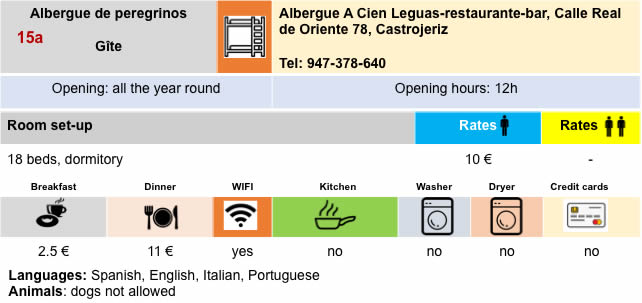

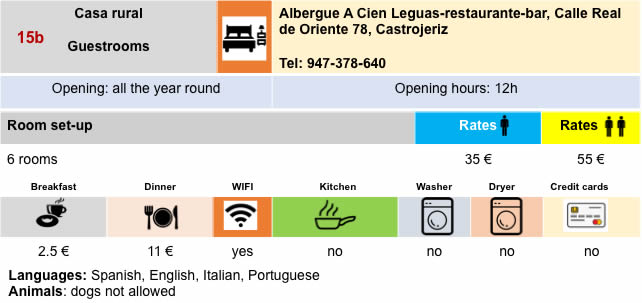

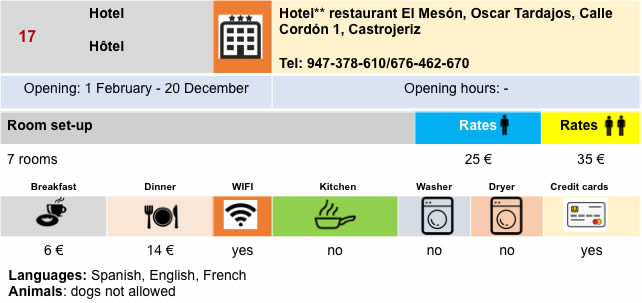

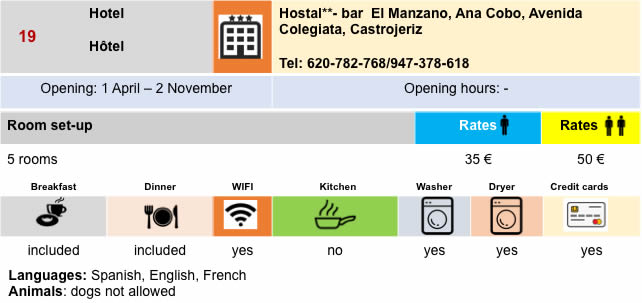

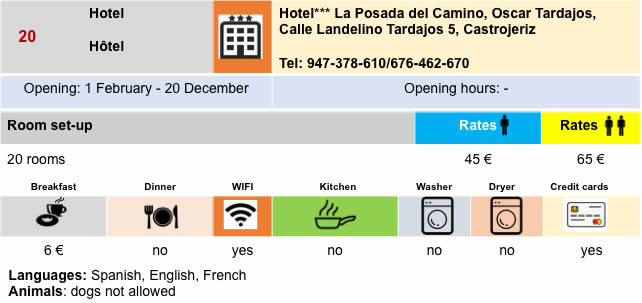

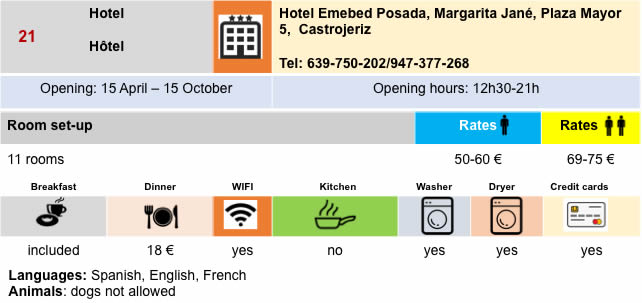

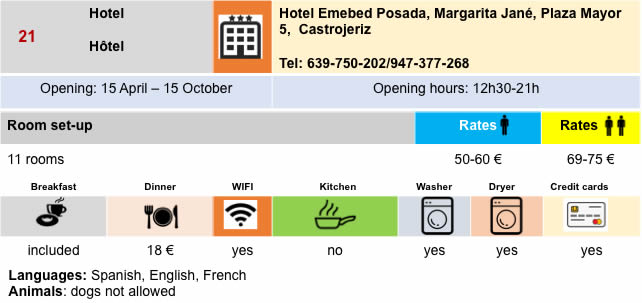

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 15: From Castrojeriz to Frómista |

|

|

Back to menu |