A dialogue with the N-547 road between oaks, chestnuts and eucalyptus

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

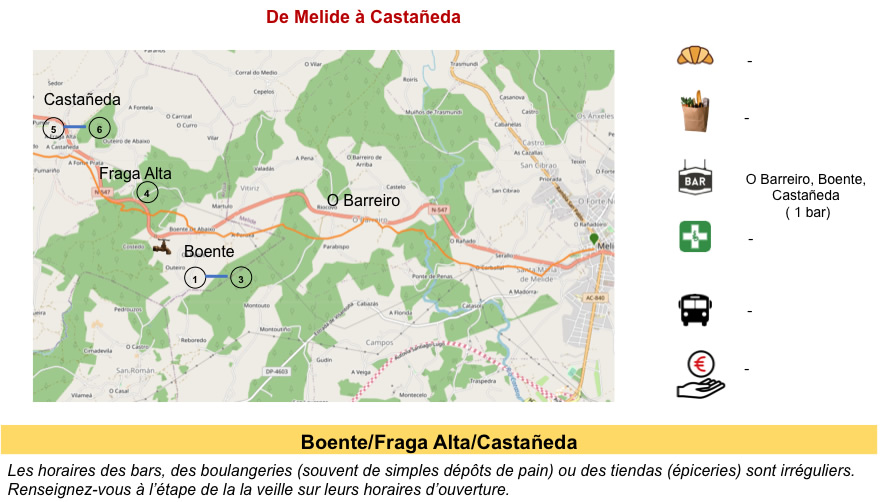

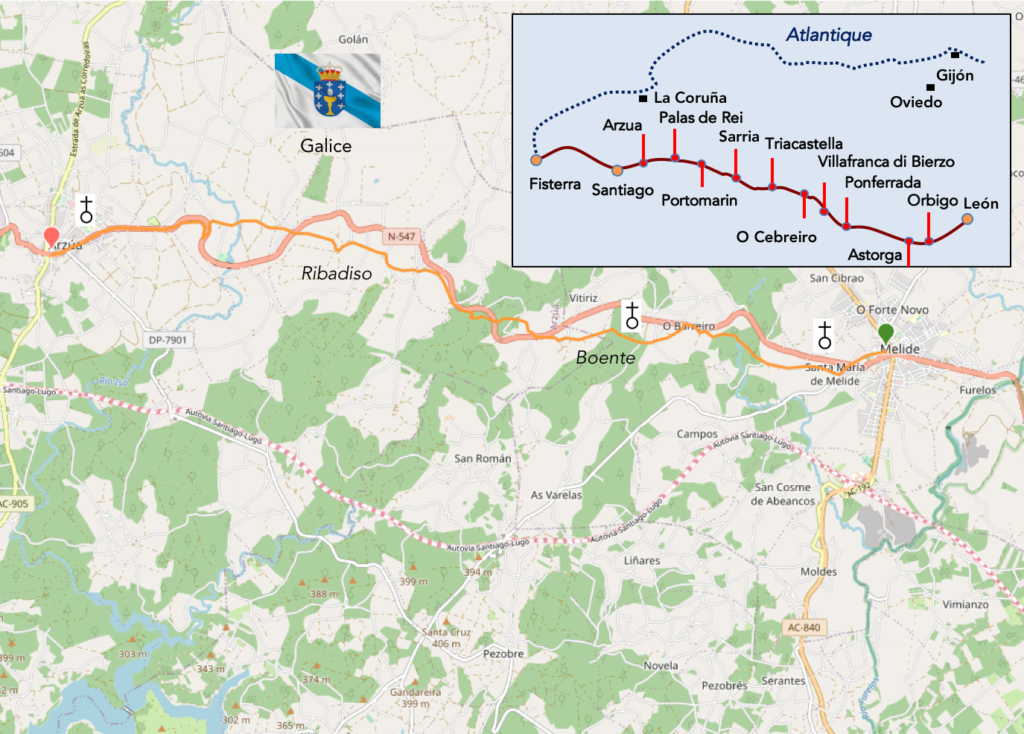

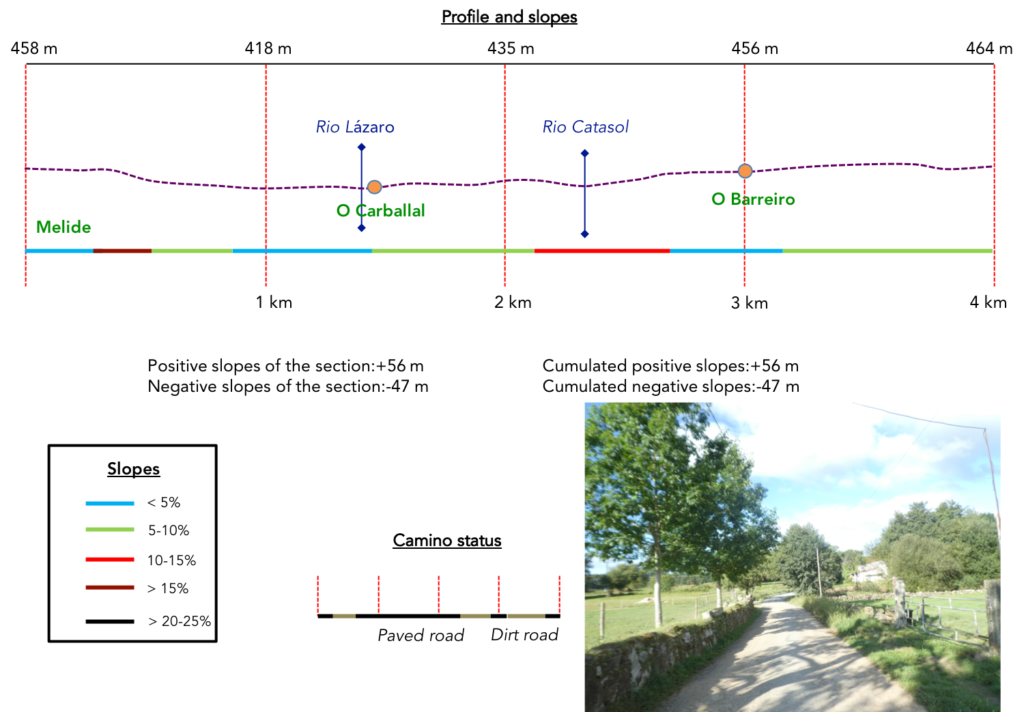

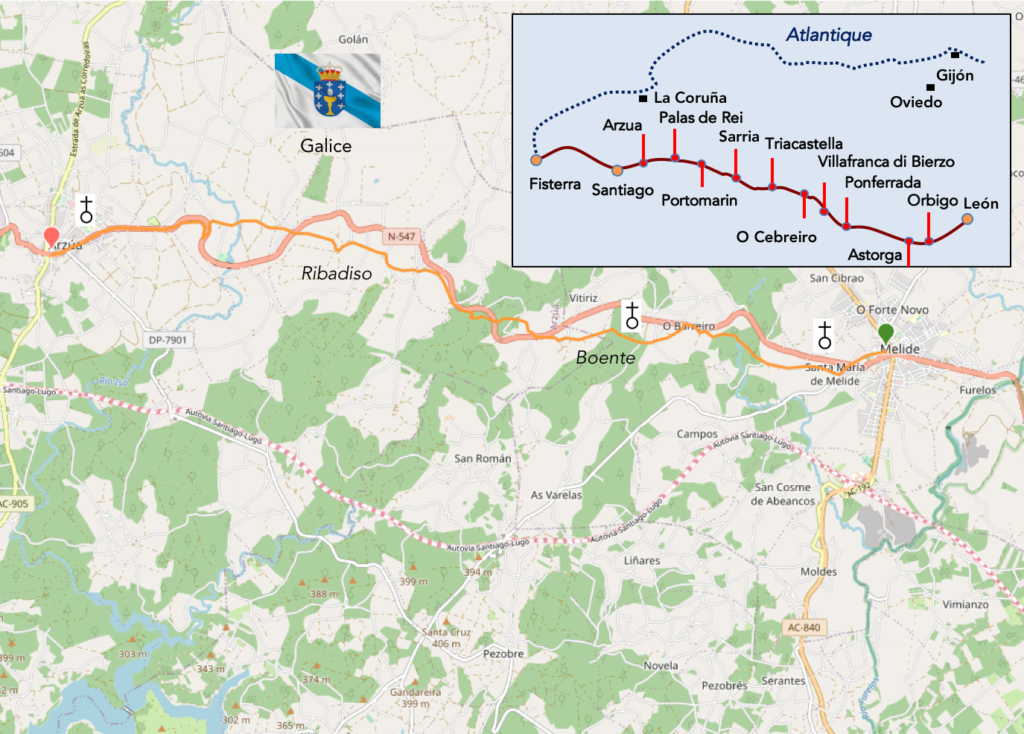

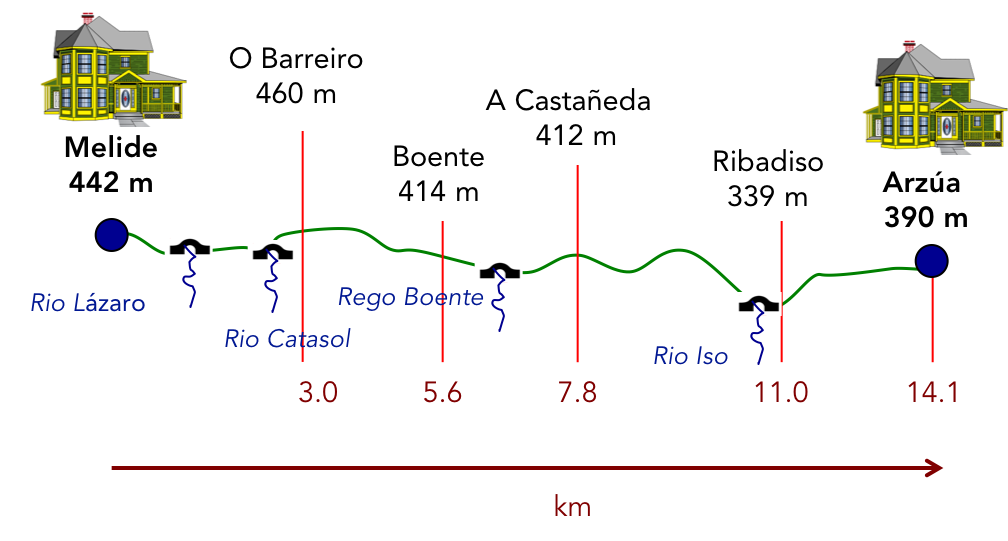

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-melide-a-arzua-par-le-camino-frances-125214471

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

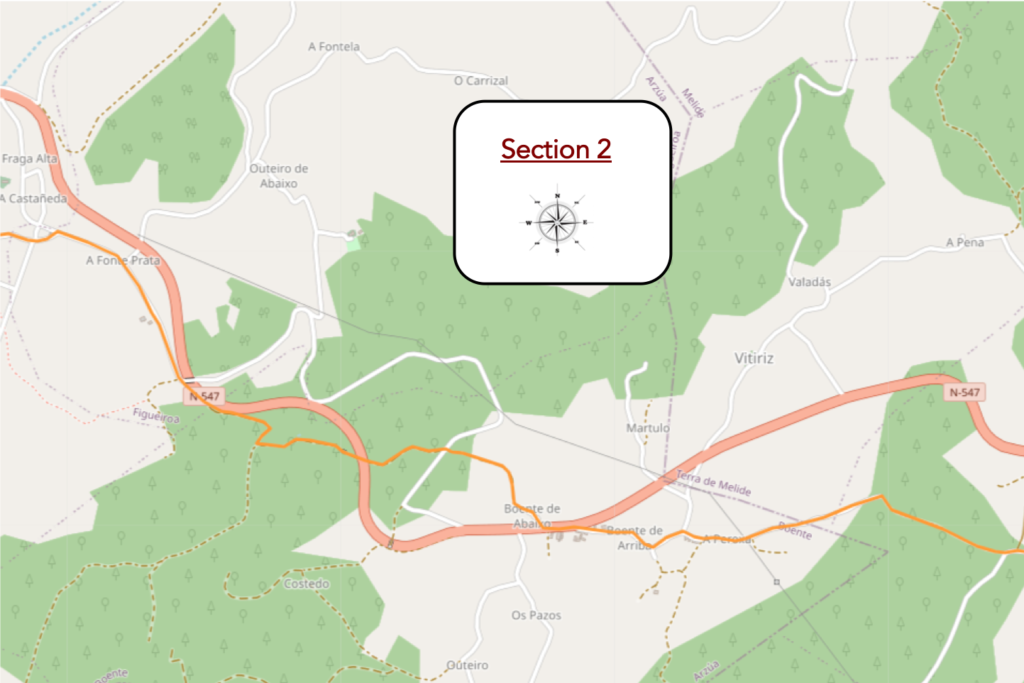

Beyond Melide, the Camino winds through shady forest, past oaks and chestnut trees giving way to more and more eucalyptus, planted for paper and timber. These forests are interspersed with cornfields. The fields west of Palas de Rei are called Campo dos Romeiros (Field of the Romans). There is very little elevation gain on the Camino from Melide to Arzúa, but the track continually climbs and descends, as many small rivers in the area have carved deep valleys. Many of the small villages retain their old rural Galician atmosphere, with their hórreos or haystacks or corn. The route goes back and forth along the long snake that the N-547 makes, but today, to tell the truth, there is no “Senda de los Peregrinos”. It changes life. When you discreetly look at the faces of the pilgrims, you see some of them pulling more and more sullen faces. Spain is a long journey. And those who come from very far are in a hurry: to get it over with. The tourist pilgrims of Sarria are a whole different story. The less athletic suffer. The others follow their life. The certificate is at the end of the road.

The closer you get to Santiago, the more the number of pilgrims swells on the route. But, here, the pilgrims, for a large part, do not stop at Melide, going directly to Arzúa. But is it so true? There are 700 beds available in Melide. They are not there to justify a large internal Spanish tourism. There is not much to do in Melide. One more word. We didn’t see a single open church on the route, and not all the hamlets have one, which is not routine in northern Spain. Often these churches are open for Sunday or holiday masses.

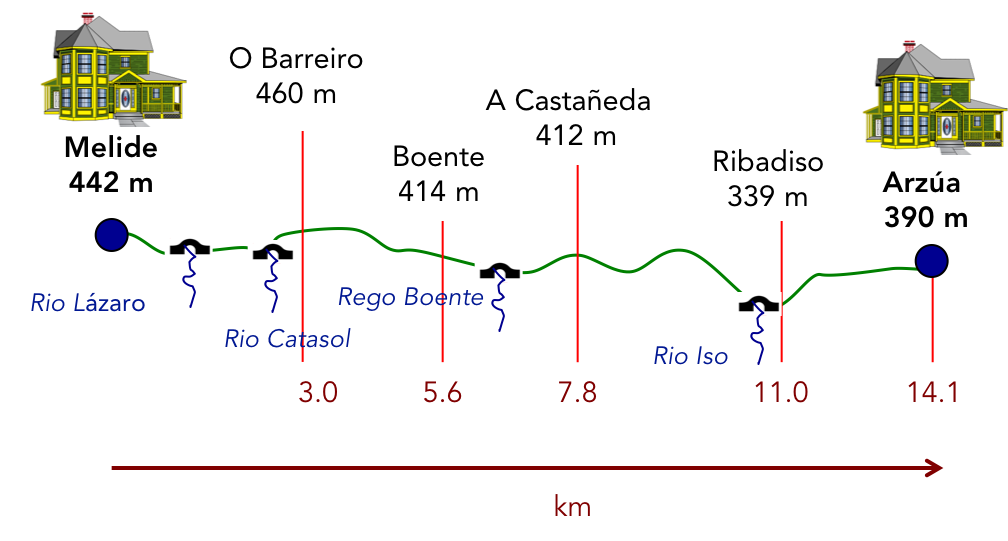

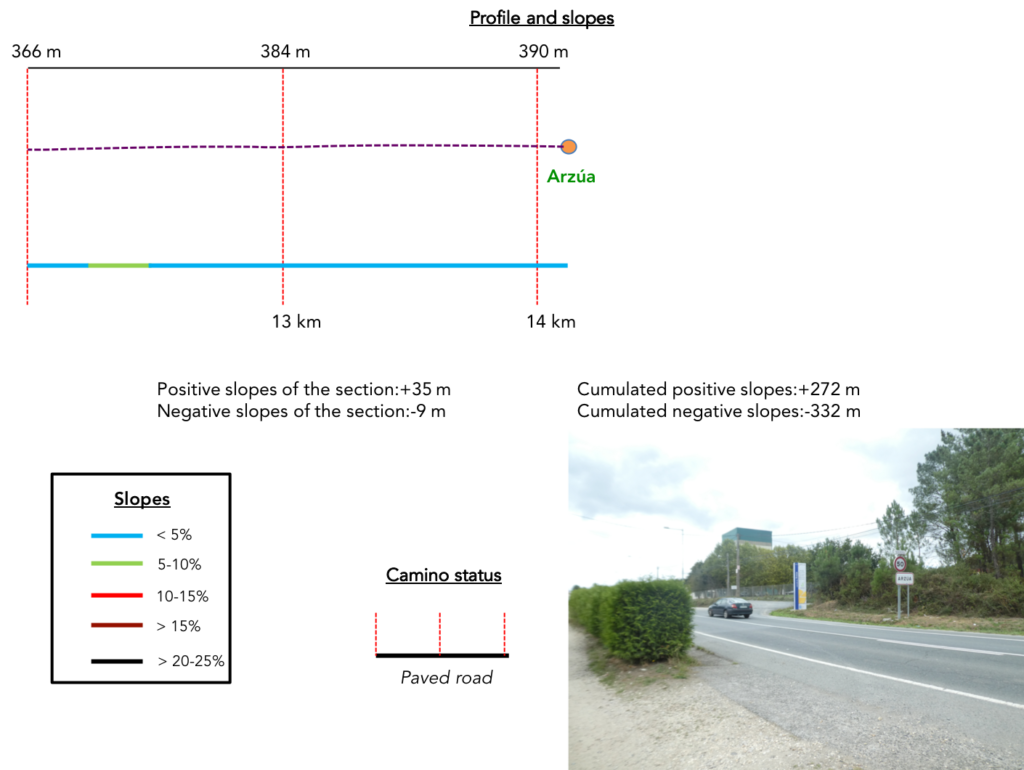

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+272m/-333m) are quite reasonable for a 14 km stage. It’s constant ups and downs game, from one stream to another, throughout the stage. There are sometimes sections with almost 15% slope, most often downhill.

In this stage, you will walk more on the roads than on the pathways, which is an exception on the Camino francés. But these are roads with little traffic:

- Paved roads: 7-9 km

- Dirt roads: 6.2 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: Between countryside and undergrowth.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| This morning is market day in Melide. The hams hang from the stall. The price is very reasonable: 5 Euros per kg. Some pilgrims go so far as to buy a whole 5 kg ham to put in their bag. |

|

|

| The Camino runs through the narrow streets of the western part of the town |

|

|

| There is even a hórreo here in town. This tells you the importance of these granaries in this part of Galicia |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino runs along the cemetery. In Spain, funerary architecture is an art. |

|

|

| Then, the slope becomes steep and the stony pathway descends between the stonewalls… |

|

|

| …to join the N-547road, at the exit of the town. The closer you get to Santiago, the more the real pilgrims, that is to say, those who have traveled from afar with their big bag, are diluted in the flow of tourist pilgrims. |

|

|

| Here the Camino crosses the national road and flattens towards Santa Maria de Melide where it also leaves the axis to pass in front of the church. |

|

|

| In front of the church stands a cruceiro representing the crucifixion. The XIIth century Church of Santa María de Melide is classified as a national monument. It is a jewel of the Galician Romanesque style, with its ornate entrances and intensely decorated capitals. It is only open on Sundays and public holidays. |

|

|

| Just beyond the church, a bridge crosses the small Río Lázaro. |

|

|

| There is a fountain-washhouse here under the trees. Shortly after, the tar ceases and a gravel road runs along the few houses of A Carballal. |

|

|

| The dirt road wanders here in the countryside, sometimes in tunnels of greenery, under the generous shade of the oaks. |

|

|

| Here you are 57 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

| Although the Camino de Santiago can sometimes be perceived as a single route and almost like a highway for pilgrims in which it is enough to advance, the truth is that the Way of Santiago is full of bifurcations that the pilgrim can sometimes take to visit significant places. We have already seen it on the side of Portomarín. These are the Complementary Ways. There are more than 20, according to the new signage installed by the Xacobeo, the Jacobeo, the umbrella organization of the Ways of Compostela in Spain, a sprawling institution.

One of the new Complementary Ways, which separates from the main road in Melide, has recently been signposted, tracing an alternative route that crosses the village of Penas, with no recorded Jacobean tradition so far, since it is claimed that the Camino de Santiago never passed through Penas. So here, unlike Portomarín, don’t go there, or if you do, you’ll find the official Camino a little further on. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway descends to the Catasol stream. The slope is steep under hardwoods, mainly oaks, which compete in power and elegance. |

|

|

| But, in western Galicia, the foresters have planted eucalypts, which make a clear place around them, and which, given the opportunity, dominate the landscape and subjugate the other trees. They are real tyrants. |

|

|

| Sometimes, in the forests, darkness brings silence, a silence made up of light breaths, tiny rustles and a thousand whispers. You will have to choose a different time from the crowd of pilgrims, to enjoy this state. Because, when the American cavalry or the Spanish guerrillas land, it’s more bullfighting around here. And what about South Americans? There, you will have to cover your ears. Only the Koreans, who whisper as if to apologize for being there, will allow you to appreciate the silence of the woods. Here, you still have 50 kilometers to learn to distinguish all this nice little world of pilgrim tourists |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the Camino crosses the stream by a narrow granite footbridge that pilgrims must cross in single file. This morning, the weather is gray in the country. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the pathway first slopes up through the undergrowth. Here, the eucalyptus trees have disappeared and it is now the chestnut trees that are waging war on the oaks. |

|

|

| Further up, the clearings appear as well as the first houses of O Barreiro de Abaixa (bottom). |

|

|

| Here, people also grow tall cabbage. |

|

|

| The pathway does not run through the center of the village. |

|

|

| Further up, it will keep the national road a little company. In Spain, all passages near roads are marked with warning signs, which many pilgrims will find superfluous. But caution requires, even if the traffic is not overflowing here. |

|

|

| The road runs along the houses on the other side of the village. Then, the Camino leaves the road… |

|

|

| …to gently descend on a wide leafy pathway. |

|

|

| Here again, the eucalyptus trees go hand in hand with the oaks and chestnut trees. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the dirt gives way to tarmac, and the Camino leaves the woods to find a tavern by the side of the road, very welcoming to eat and drink |

|

|

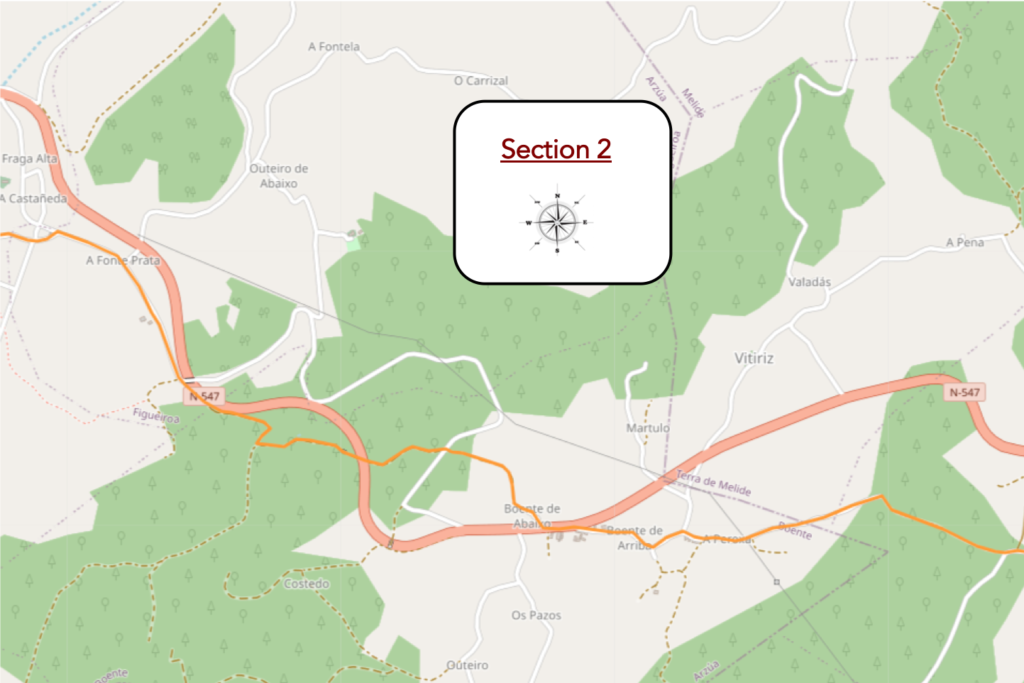

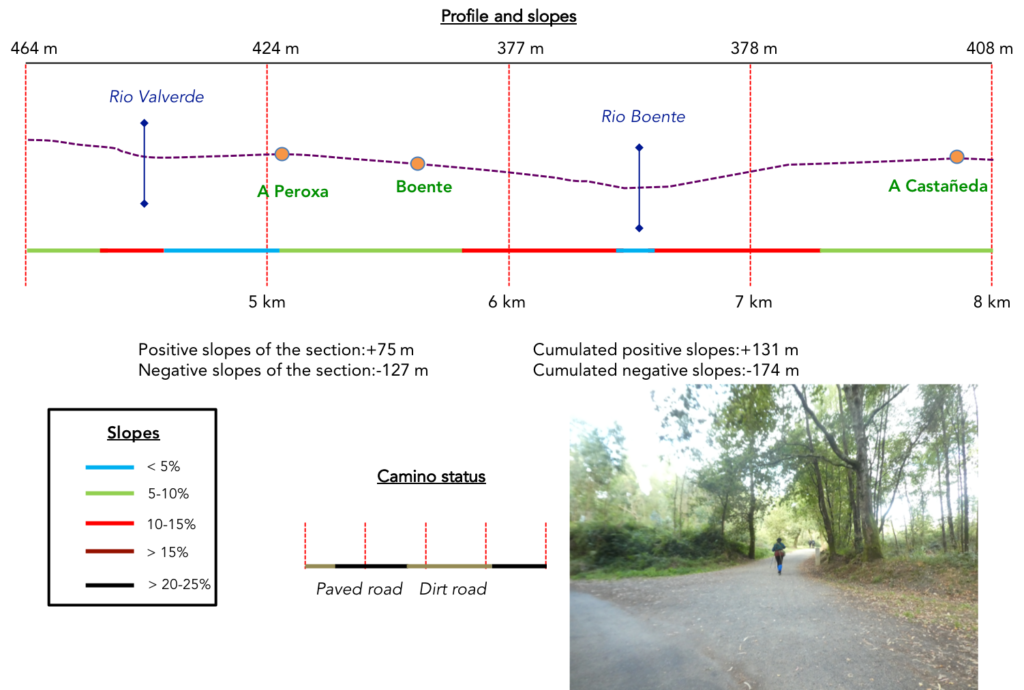

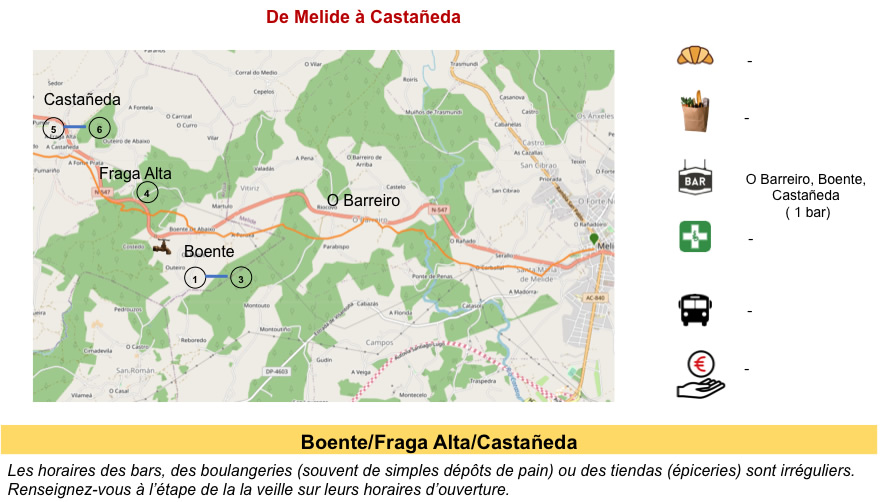

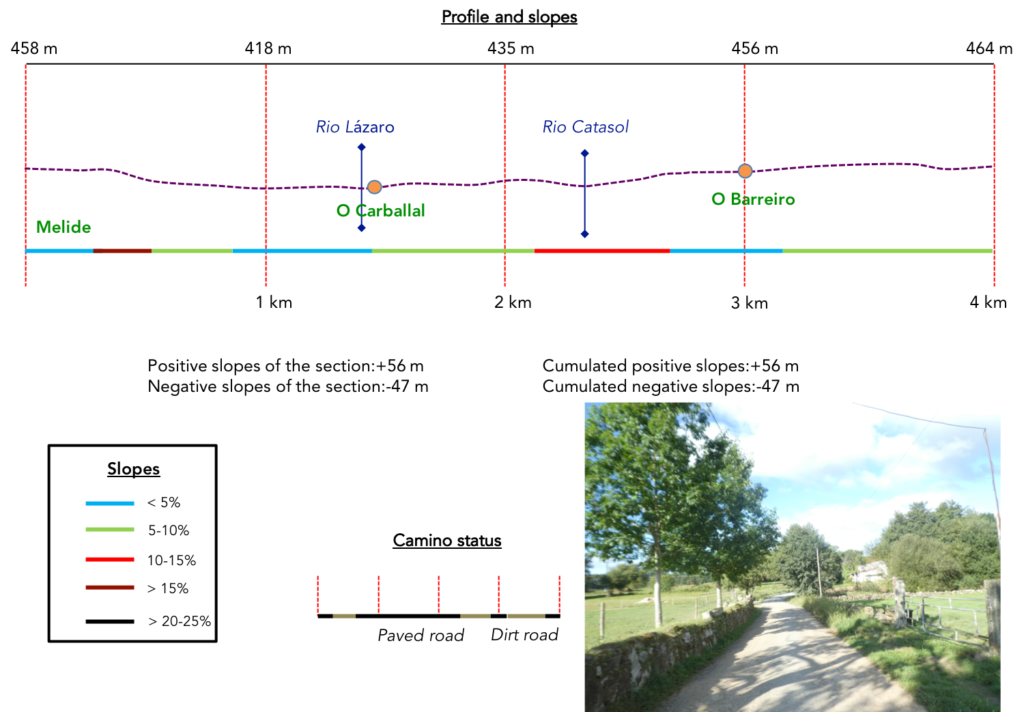

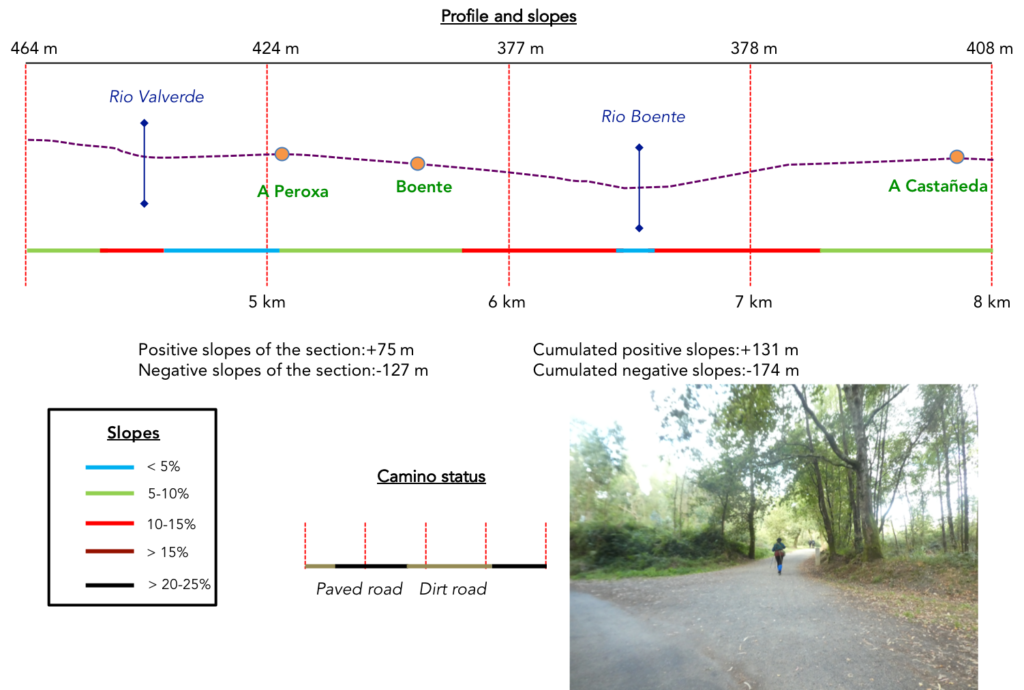

Section 2: In the forests of Melide.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course with significant slopes.

| Beyond the rest stop, the Camino still follows the road a little further, which enters the woods again. |

|

|

| Then, in the forest, the slope is gentle. Cyclists don’t even use the brakes. |

|

|

| This is no longer the case when the dirt road approaches the Valverde stream. |

|

|

At the level of the stream, a beautiful picnic spot is hidden under the tall trees. Empty, as most often on the Camino francés.

| It’s always been the same scenario for a few days. The sky is gray in the early morning, and then the weather becomes pleasant. Then, the landscape is even softer on the wide avenue of dirt in the meadows and the oaks. |

|

|

| Soon it’s the paved road and it’s A Paroxa, with its houses scattered among the fruit trees and stilted cabbages |

|

|

| Shortly after, and almost contiguous, the road arrives at Boente da Baixo. |

|

|

| Boente is a hamlet divided in two by the national road N-547. The village has a good infrastructure for pilgrims. The place is known for its cheeses. You can still find hórreos here, but more modern. |

|

|

A sober cruceiro stands as the village moves to the side of the national road.

| The church of Santiago de Boente is documented from the VIIIth century, although the current building dates from the XXth century. |

|

|

| A paved road with slabs leaves the village. |

|

|

| Further on, at the entrance to the undergrowth, it is a pathway that will descend very steeply for a while. The oaks accompany you in a dark and humid universe. |

|

|

| Along the way, the Camino crosses a small local road. But, it continues to descend straight in the direction of the Rio de Boente. The vegetation, always the same, is dense here. |

|

|

| Further down, it passes under a bridge on the national road… |

|

|

| ….before coming across a picnic spot in an enchanting setting near the river. |

|

|

| The pathway slopes up beyond the stream first between clearings and oak undergrowth above all. |

|

|

| The slope increases rapidly in the forest, 45 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

| At the exit of the forest, the pathway finds the national road back… |

|

|

| … and runs on a small parallel road towards A Castañeda |

|

|

| The road runs gently downhill past the houses of A Fonte Prata, then A Castañeda. |

|

|

| In the village, the Camino changes direction and reaches a crossroads towards Rio. It was here, in Castañeda, that medieval pilgrims deposited the limestone rocks they brought from Triacastela to be fired in a limekiln used for the construction of Santiago Cathedral. The Codex Calixtinus mentions it. Today, there is no longer any sign of the oven. |

|

|

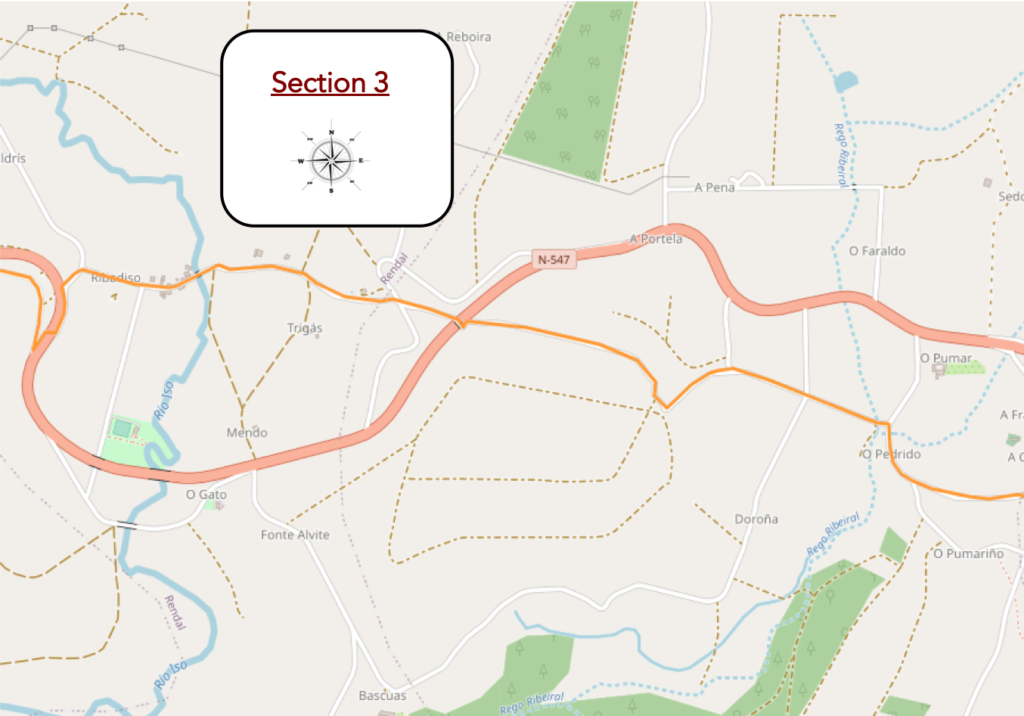

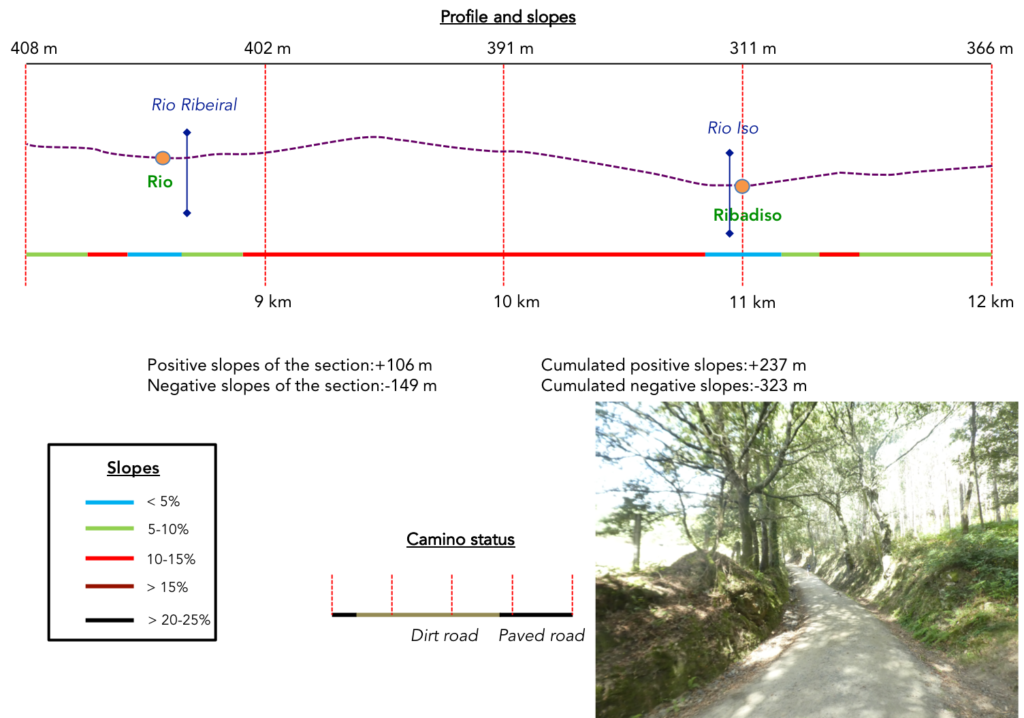

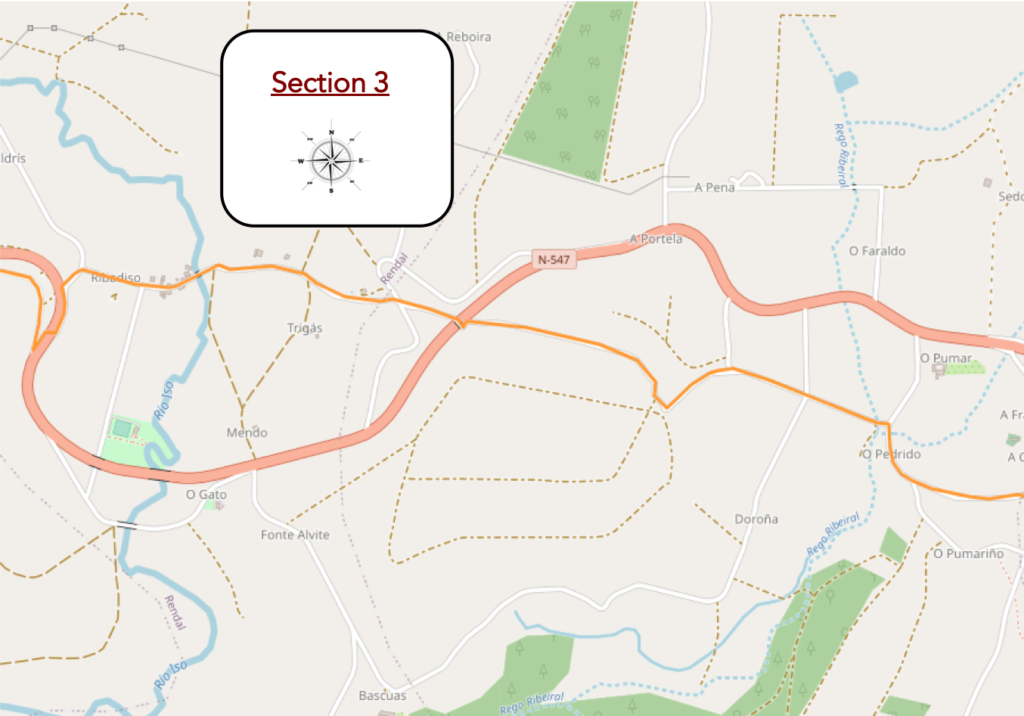

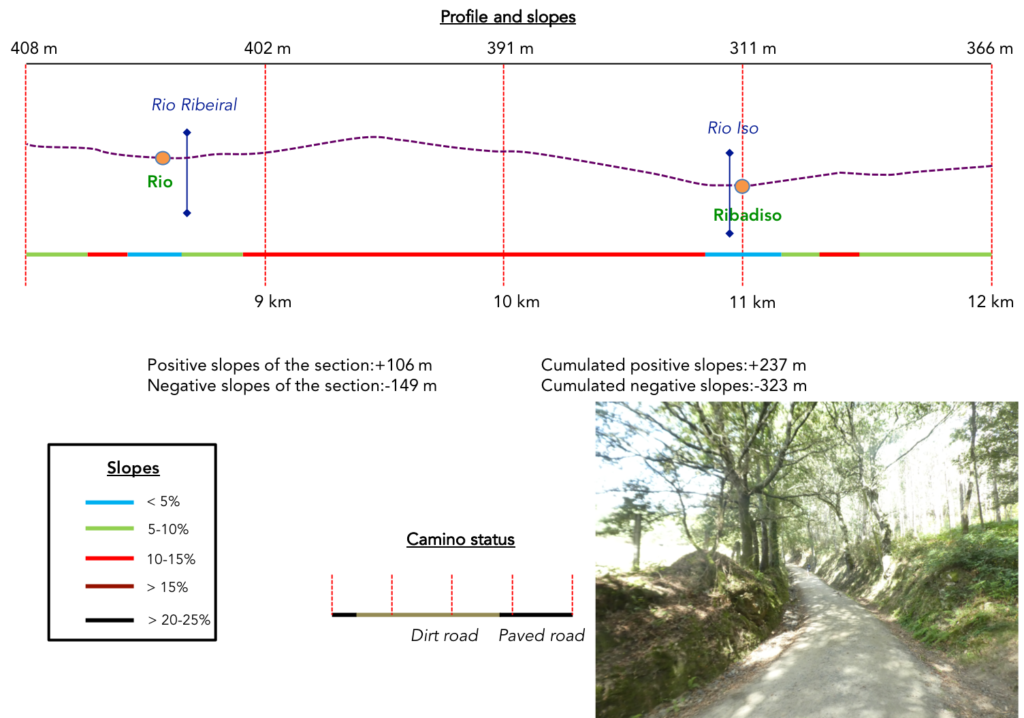

Section 3: Over hill and dale in countryside and forest.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course with significant slopes.

| Above all, there is agricultural activity here. But, the possibilities for pilgrims are not negligible. |

|

|

| Beyond Castañeda, a fairly long road heads to the hamlet of O Pedrido. |

|

|

| It is a country hamlet, with not very old houses. |

|

|

| Here, crops share space with meadows and groves. A stone’s throw away, the road runs through the hamlet of Rio, at the bottom of a dale. |

|

|

| This is where the Rio Ribeiral flows, a small stream adjacent to a picnic spot. |

|

|

| Here, there are not many picnickers. On the other hand, you have to take your ticket to relieve your muscles at the message table, in the middle of nature. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the road climbs gently into the crops. In autumn there is only corn. |

|

|

| Further on, after the crossing with a road, the Camino begins to climb towards the woods on an increasingly steep slope, but there is nothing demanding in this stage |

|

|

| Further up, when the slope becomes tougher, the eucalyptus trees beckon you not to leave the oaks alone. |

|

|

| Further, the road begins a long descent of the hill. An uninterrupted, motley line plays with the slope. Beyond Sarria, it is very easy to know who started the course there. They are the ones that give “Buen Camino” when they pass you. The others, those who come from very far away, sometimes more than 2,000 km from here, are tired of saying it. Even the Koreans, who begin their journey in Roncesvalles, have erased the word sesame from their vocabulary. |

|

|

| In the groups, the discussions are going well, useless as most often. Lonely people, often-older people, save themselves. |

|

|

| Further down, amid eucalyptus, oaks and a few conifers, corn grows. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway crosses over a bridge the N-547 road. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway gets closer to civilization again. There are some beautiful homes lost in the vegetation. Here, the Camino is tar. |

|

|

| But the slope remains steep on the road to the river. You guess that here the country seems a little more populated than during the first part of the stage. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the road arrives in the outskirts of Rivadiso. And here is the first bar. It is always so. The former is the best served. This is an essential rule of marketing. So, the pilgrims, thirsty or not, flock to the terrace to talk about their very relative exploits of the day. Viva el Camino inglés. “Buen Camino”. |

|

|

| The village is just below. Rivadiso (Ribadiso do Baixo) takes its name from its location on the Río Iso. A bridge has spanned the Río Iso here since the VIth century. Two other Romanesque bridges were built in the XIIth and XIIIth centuries. |

|

|

| The village setting is enchanting. Many pilgrims will stay here, as Arzúa is rather off-putting |

|

|

| There was once a XVth century pilgrim hospital, the Hospital de San Antón. It was restored in the 1990s and now serves as an “albergue”. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the road slopes up gently on the hill. |

|

|

| Here you are 40 km to Santiago. Next door, right? |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road makes a detour to pass through a tunnel under the N-547 road |

|

|

| The Camino climbs again passing near the houses of Ribadiso de Arriba, staged on the hill. |

|

|

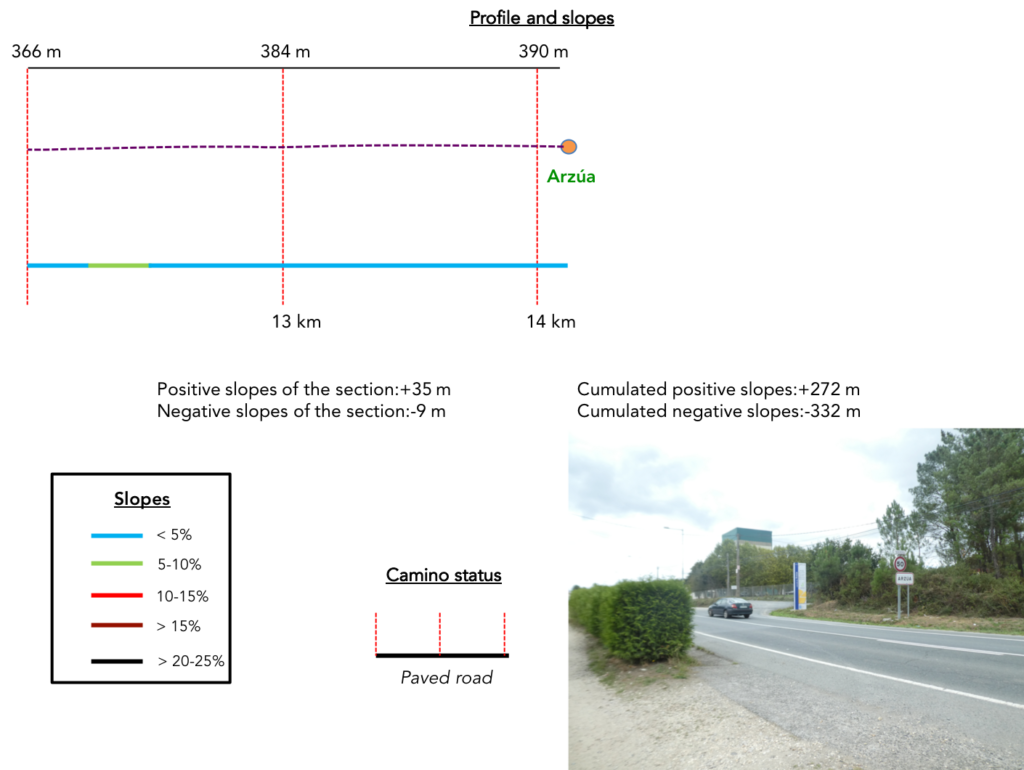

Section 4: Towards Arzúa.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The road that always climbs gently comes out of the last houses of Ribadiso de Arriba. |

|

|

| It approaches the N-547 road again. Here, one last hórreo to put under the pupil, which should no longer be of much use. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino joins the national road. |

|

|

| It is then a long approach to the town on a strip of dirt along the national road. |

|

|

You are then 39 kilometers to Santiago. The bravest will perhaps go in a single stage to Santiago

| Soon after, the Camino enters the city proper on the sidewalk. |

|

|

| Arzúa (6,000 inhabitants) is above all, for pilgrims, a long street where bars and accommodation follow one another. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino arrives in a district that could be called the old town. It is probably not here that you will plan your next vacation in Spain. |

|

|

| Arzúa is the last major population center before reaching Santiago. It is a city known for its cheese and honey. In the square is a modern statue of a cheese maker. There is archaeological evidence that this area was already inhabited a few centuries BC by the Celts. Then she saw the presence of Romans and Arabs. After the Reconquista, the repopulation must have been quite late, since the Codex Calixtinus refers to it as Villanova (new town). In the Middle Ages, it was a lordship of the Archbishop of Compostela. The village grew rapidly in the XIth century, at the peak of the Camino in the Middle Ages, when Arzúa was traditionally the last stop before Santiago. For most of the Middle Ages, Arzúa was a small fortified village. But the walls have disappeared.

The church of Santiago is recent, from the end of the XIXth century, built on the ruins of an old baroque church. On the other hand, in Arzúa there is the Capela da Madalena, a Gothic chapel dedicated to Santa María Magdalena, which was part of an Augustinian monastery founded in the middle of the XIVth century, dependent on Sarria. In the XVIth and XVIIth centuries, the monks of Sarria maintained a small hospital for pilgrims there. Later, the brothers settled in Santiago, and the monastery disappeared until not a stone remained. Only the chapel remained and worship was held there until the end of the IXth century, when it was abandoned. It has since been used as a prison or as an attic, before being restored. |

|

|

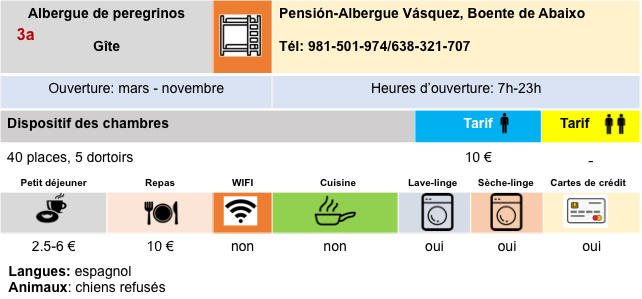

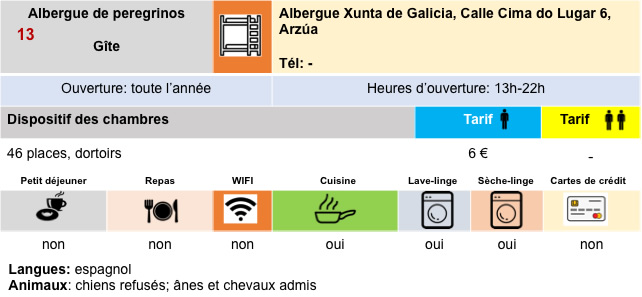

Logements

![]()