There is no longer a single mule in Mansilla

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

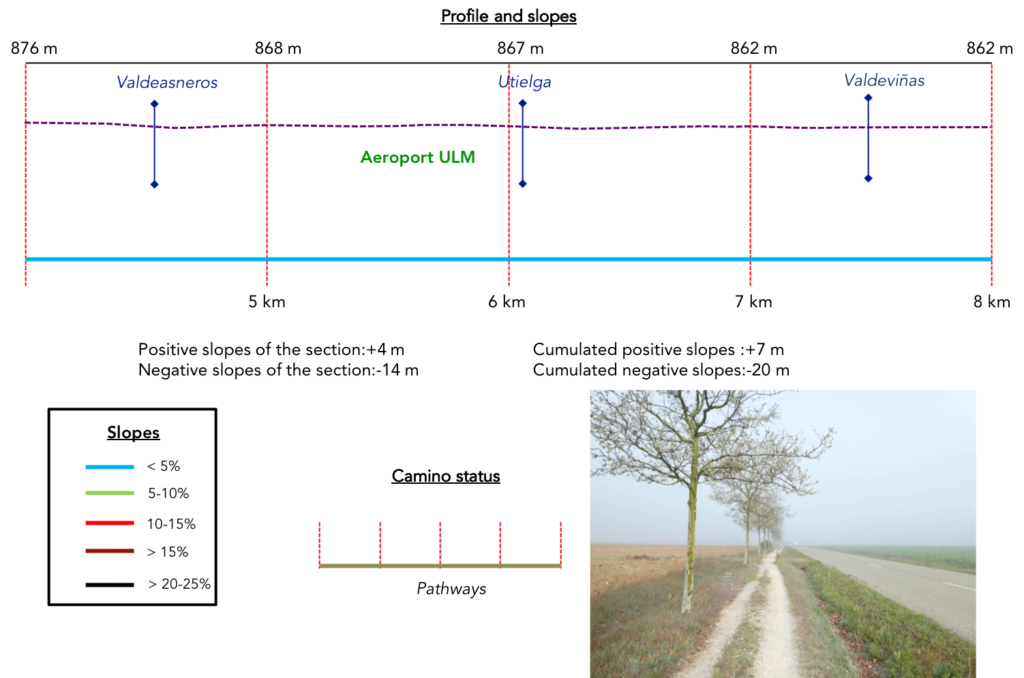

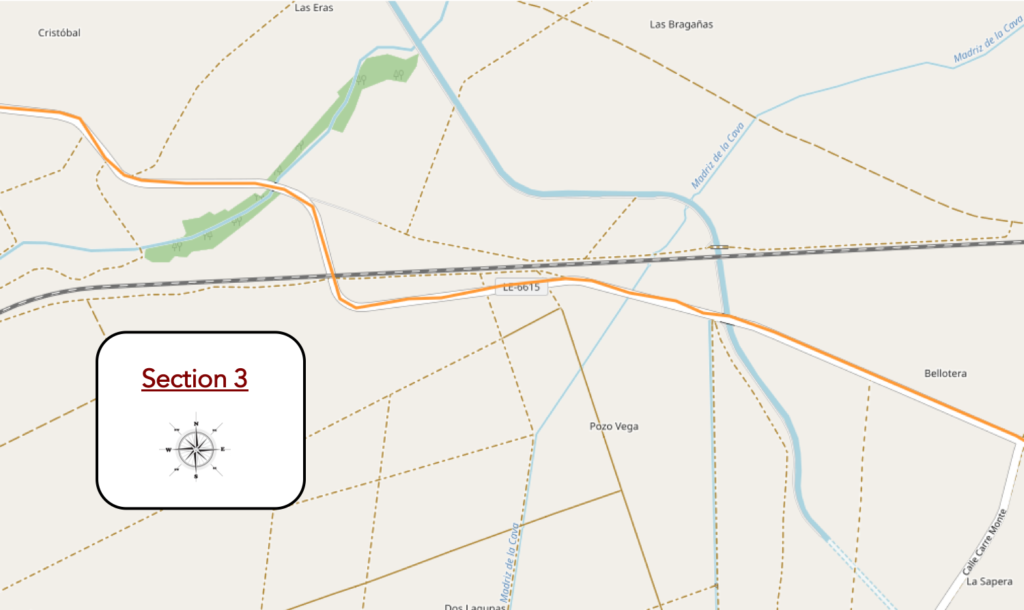

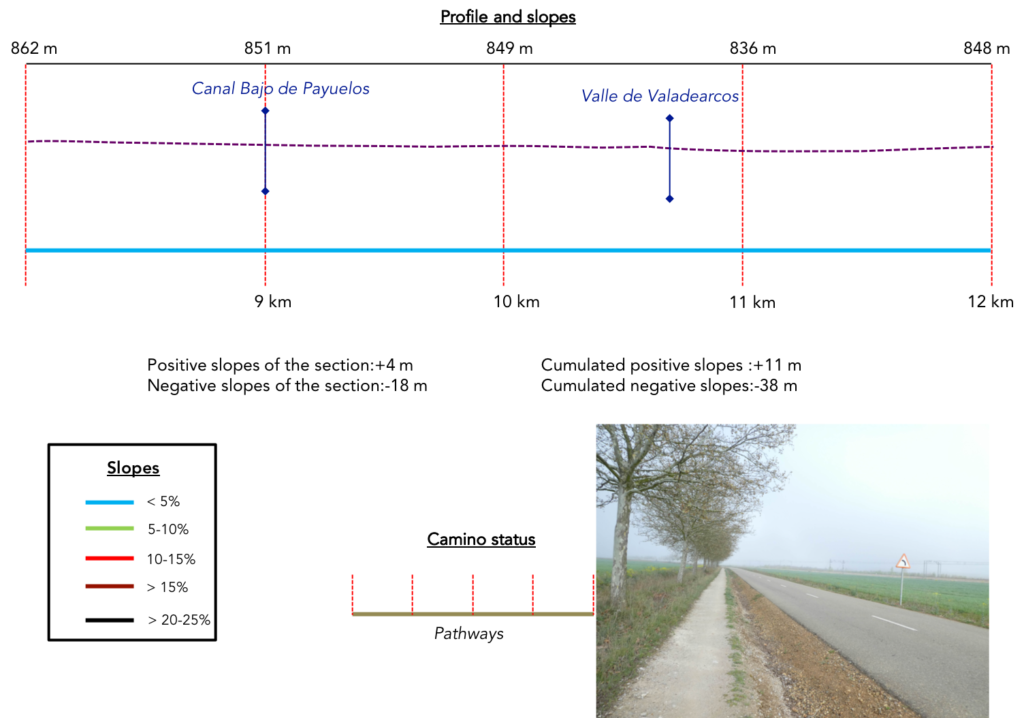

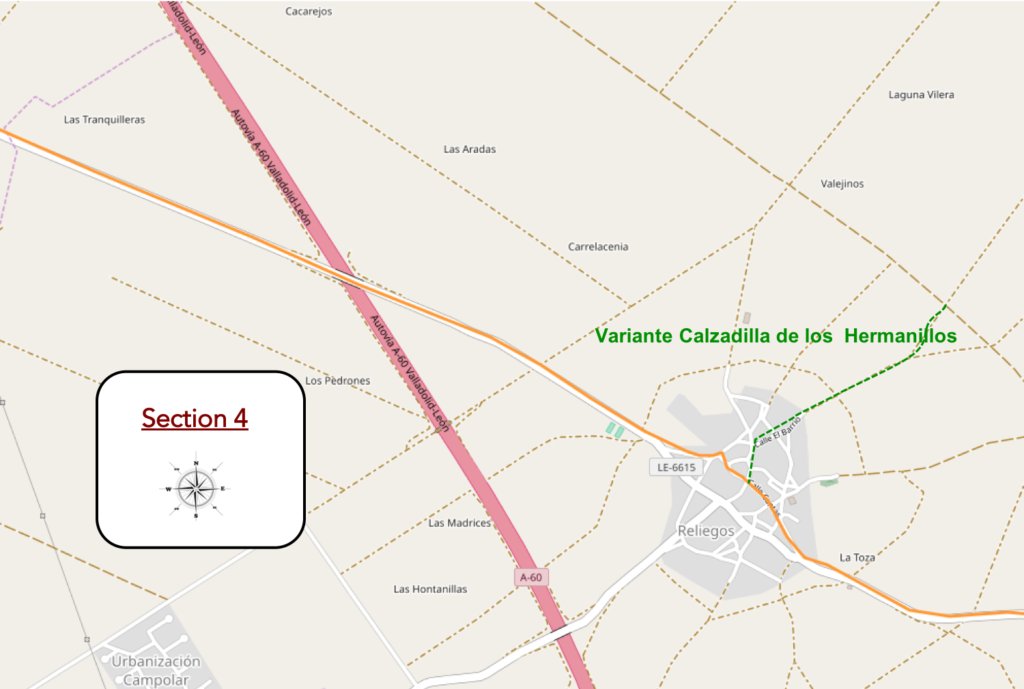

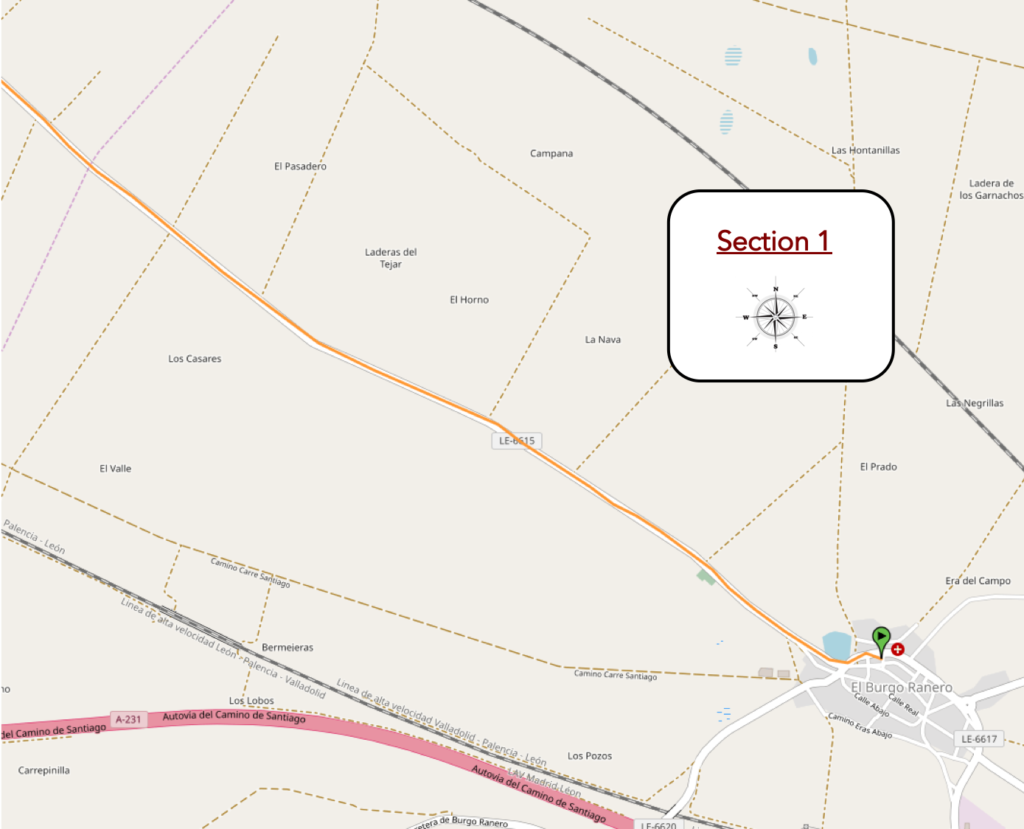

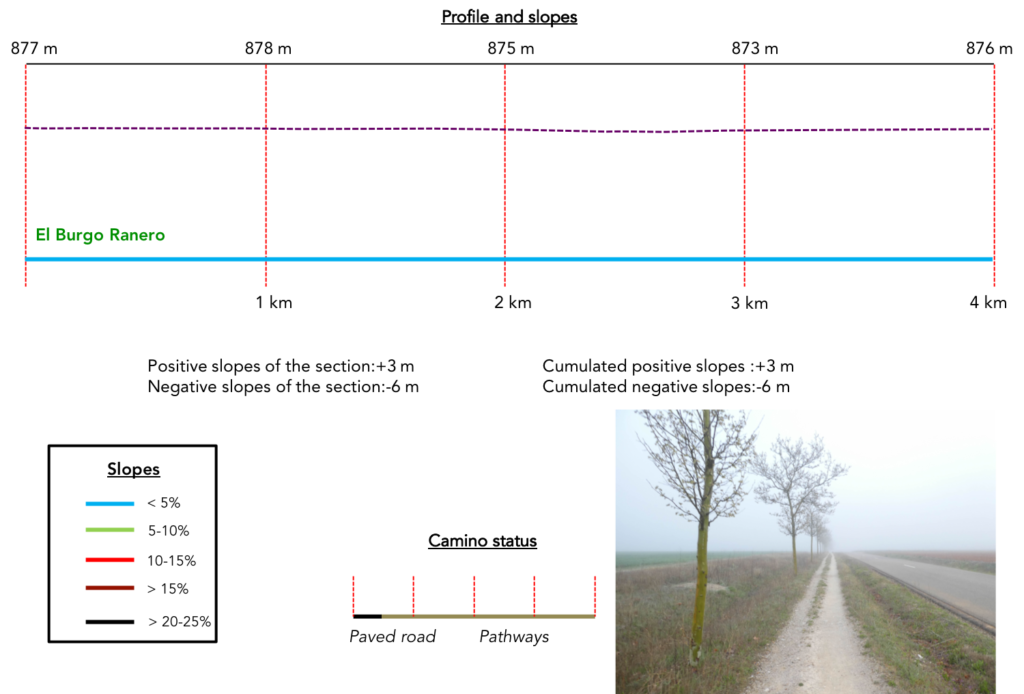

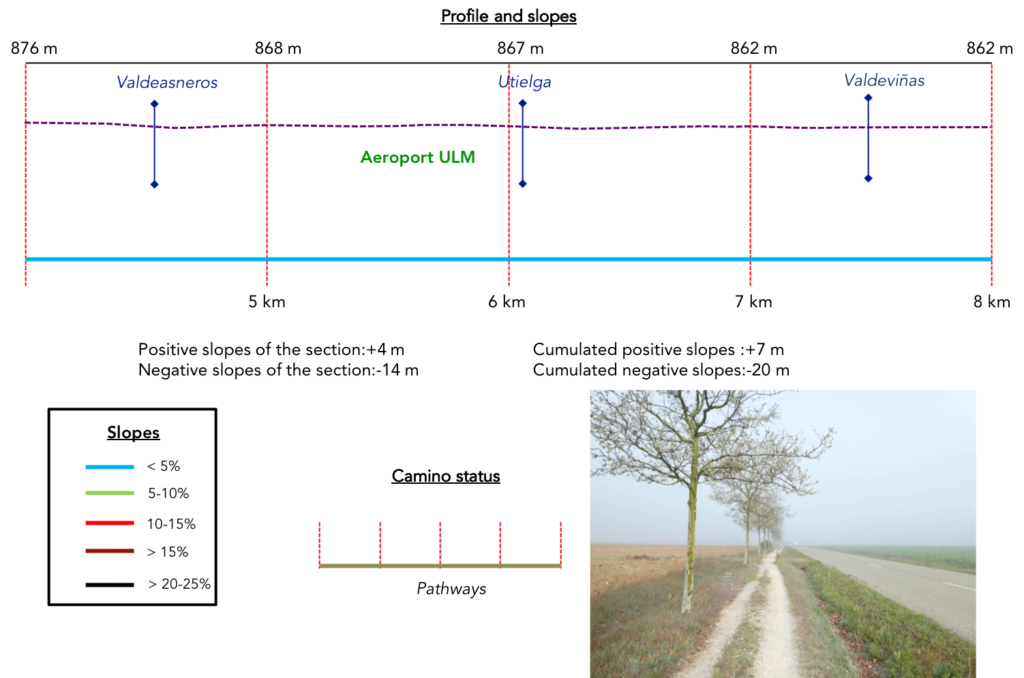

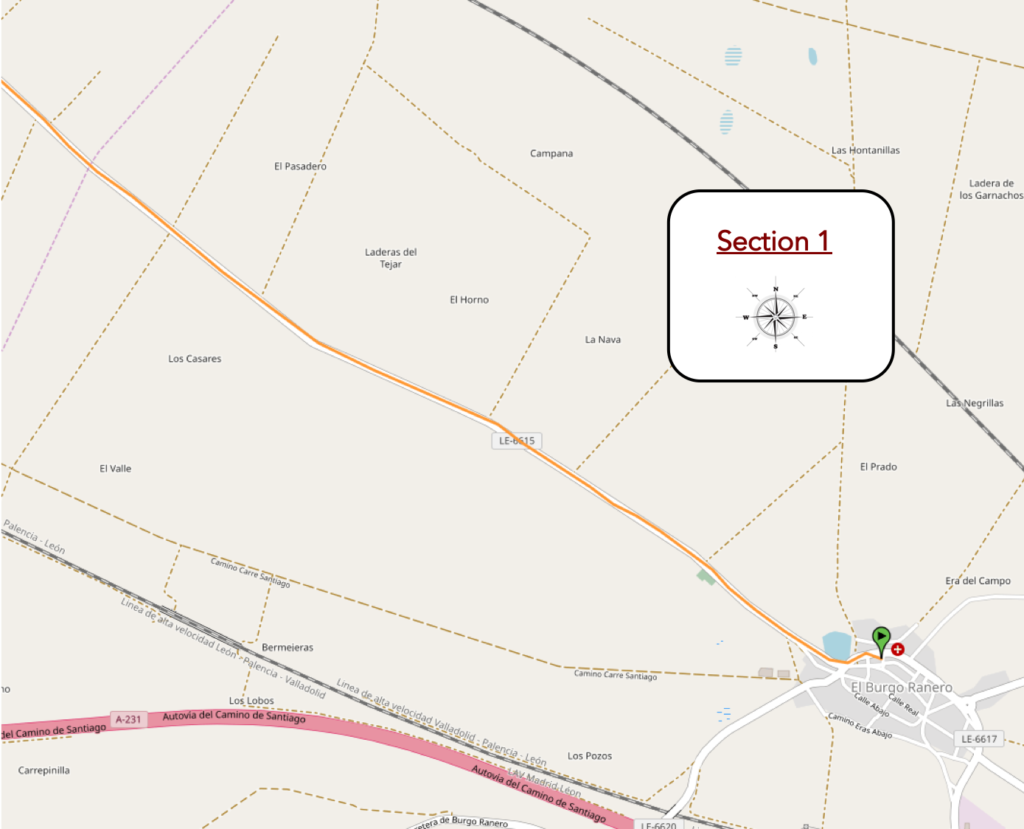

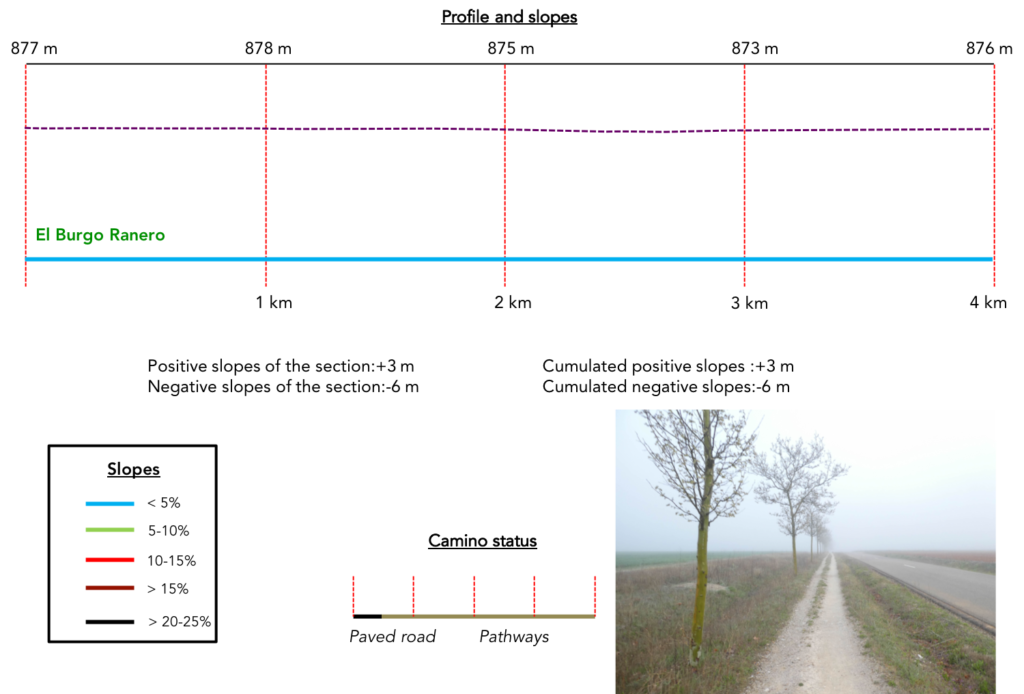

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

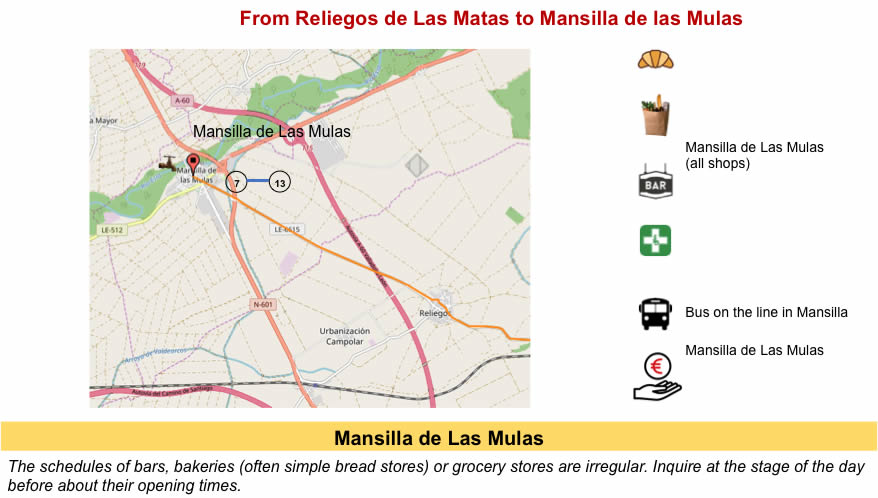

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-el-burgo-ranero-a-mansilla-de-la-mulas-par-le-camino-frances-33903996

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

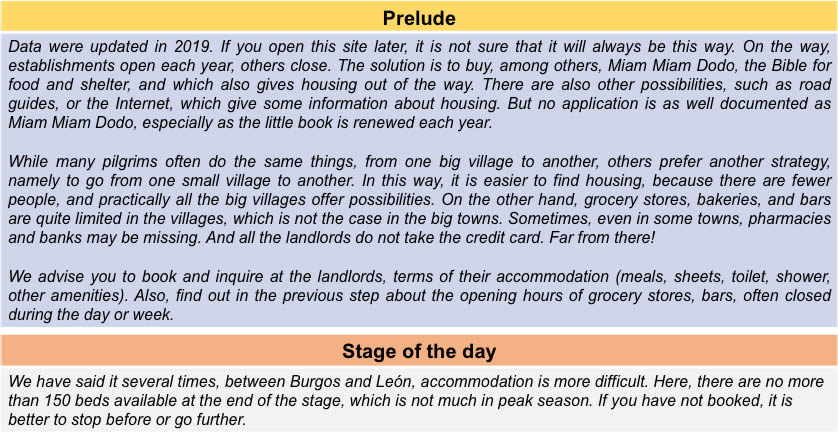

A few more days to cross this endless Meseta. And today, this is where the Meseta is the flattest and above all the largest. In places, your gaze will reach the mountains of Cantabria in the north, more than 50 kilometers from here. And the same goes to the south, where you almost want to discover Valladolid, or even Madrid in the very distant horizon. In Europe, you will not find anywhere a vision of such a nude area, of such an infinite plain. You could sometimes think you are traveling over the great plains of America.

It’s obviously no surprise today. Again and again, the “Camino real” which runs along the road along the horse chestnut trees. About twenty kilometers of “programmed pleasure”, right? Come on, this is not the most beautiful stage of the Camino francés. Far from there!

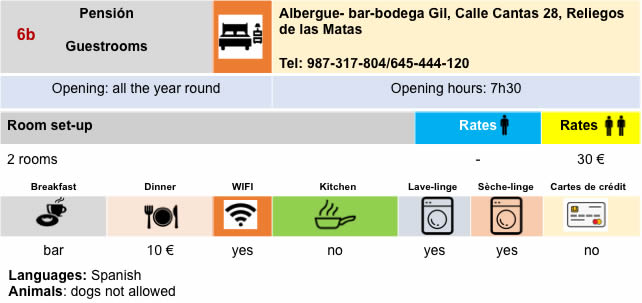

Be careful here with the accommodation. Add all the pilgrims who left St Jean-Pied-de-Port to those added on the way, and you can sometimes have more than 400 people to accommodate per day in these small villages. And if you consider the number of available accommodations, there are hardly more than 150 beds available in the village. Book.

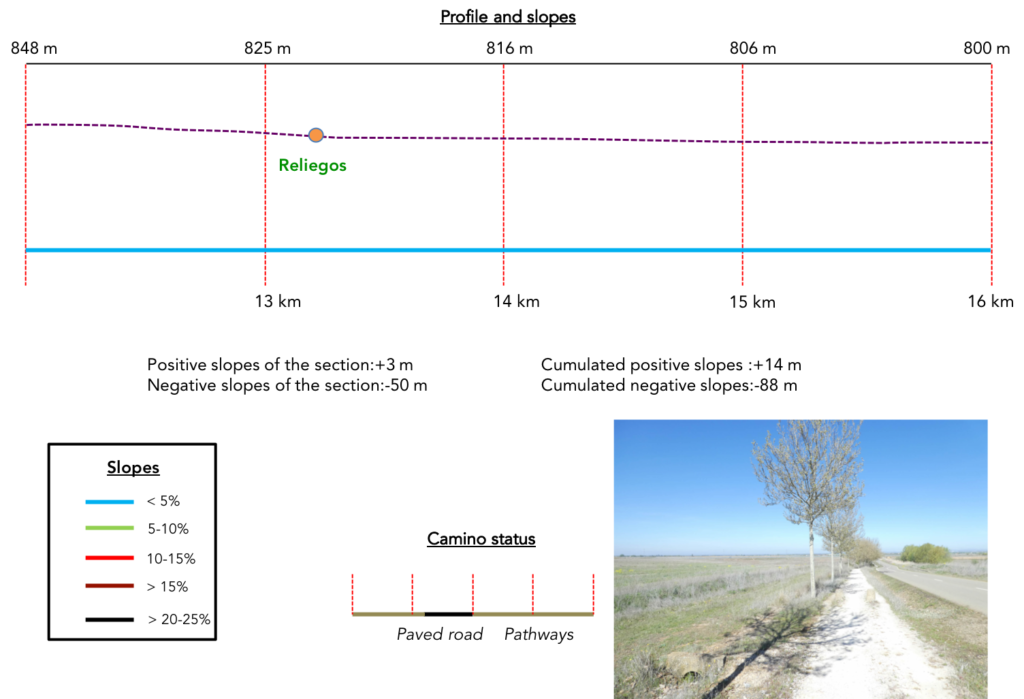

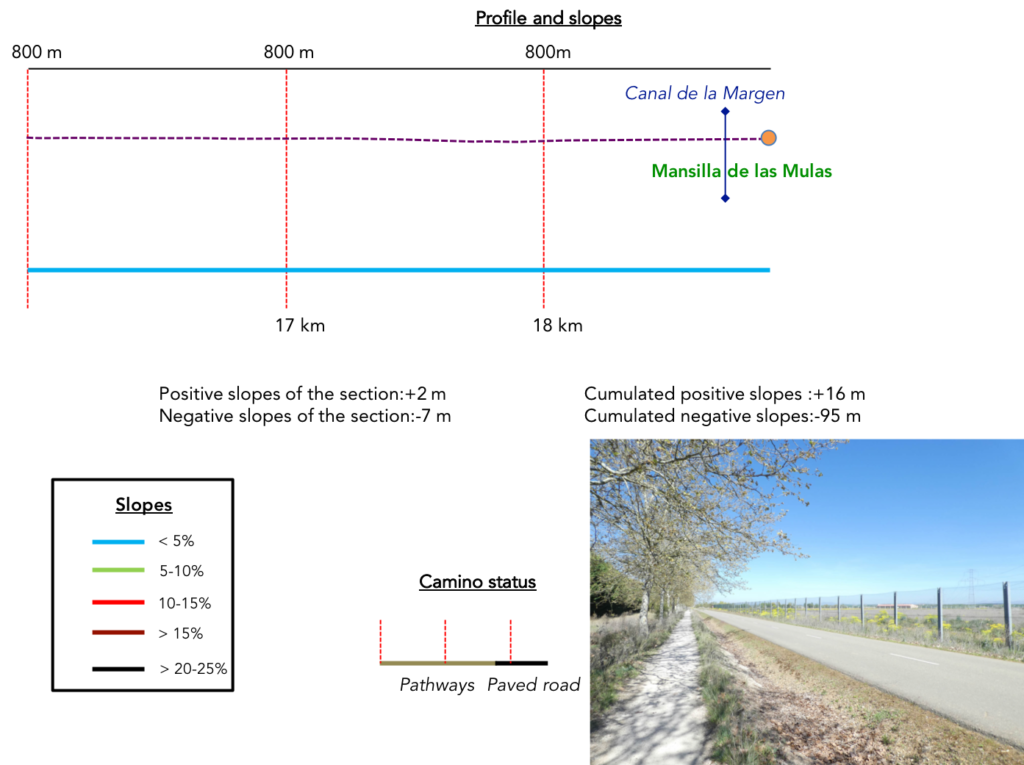

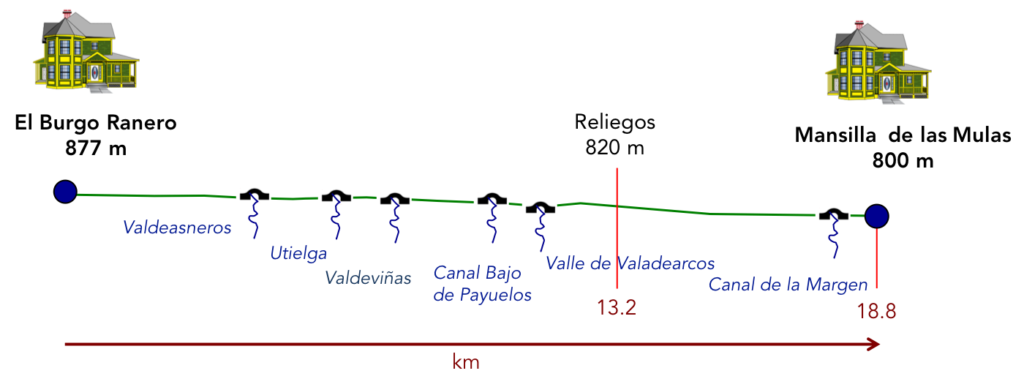

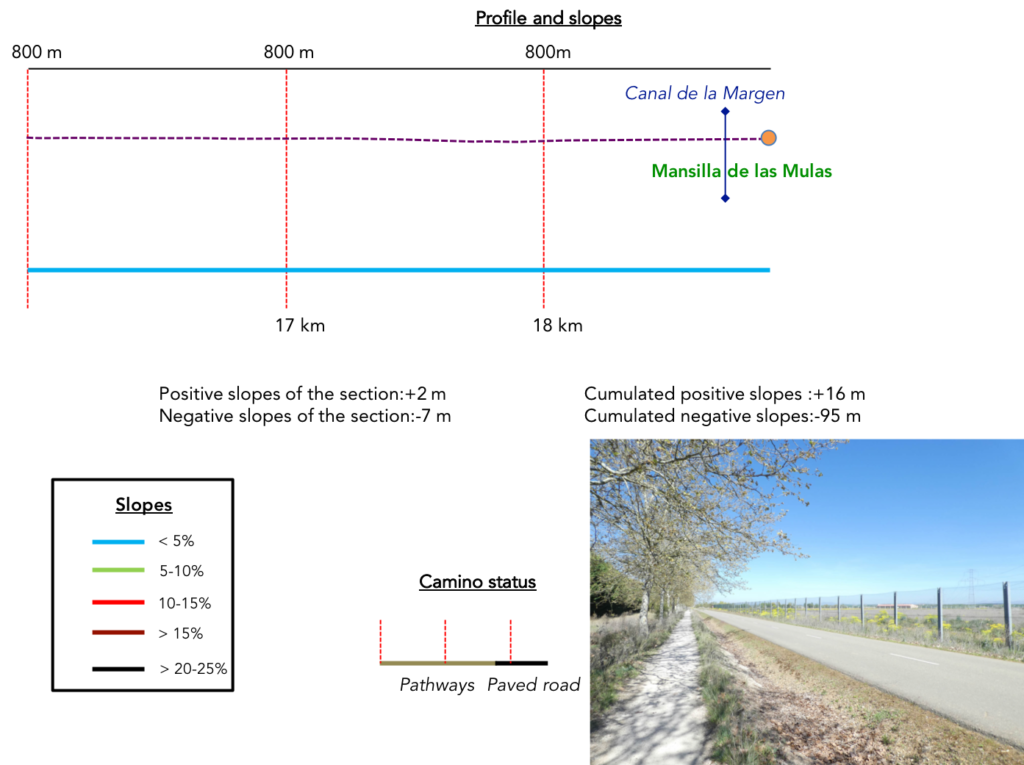

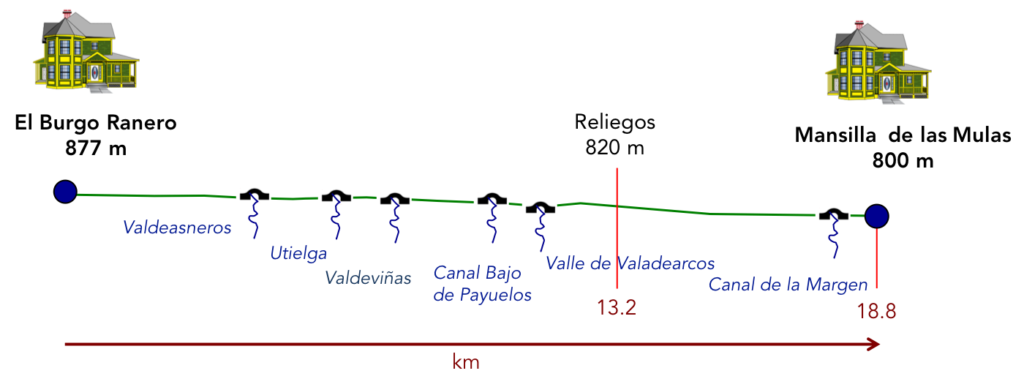

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the stage (+16 meters /-95 meters) do not speak for great difficulties that you will find on the course.

Again and again, you will walk on a pathway along the paved roads:

- Paved roads: 1.5 km

- Dirt roads: 17.4 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: Today, in the fog of the Meseta.

General overview of the difficulties of the routes: course without any difficulty.

| This morning, there is fog thick as potato soup over the Meseta. This spring, we will have known all the weather here, the rain, the wind, the blizzard, the snow, and now the fog. Here, you can hardly guess the Plaza Major from where the Camino starts. By road, Mansilla is 17.6 km away. By the Camino, it’s only one more kilometer. |

|

|

| There is a small pond at the edge of the village that you can barely guess. The Camino immediately enters the “Camino real”, along the LE-6615 road. |

|

|

| This is obviously no surprise today. The Camino is always and again a pathway that runs along a road along the horse chestnut trees. The fog is so dense that you cannot count the pilgrims on the way or the cyclists passing on the road. |

> > |

|

| How to describe a landscape that you do not see? If you saw it, you would find here all the panoply of fields that you have now been following for nearly 300 kilometers, wheat and barley in abundance, with a little corn and sunflower. However, there are benches and cruceros on the way. |

|

|

| It’s still as flat as your hand and sometimes the articulated irrigation systems pop out of the fog like zombies. |

|

|

| And the kilometers pass, repetitive, monotonous, without surprise. This morning, the pilgrims are no longer landmarks to measure your advance on the track. You sometimes exchange a word here and there with them, to pass the time and hope to see the fog dissipate. How boring! A rare vehicle runs from time to time. |

|

|

Section 2: Real Camino, always less “royal” but always so “true”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Then the fog dissipates slightly. You are now beginning to distinguish fleeting shadows of pilgrims walking in front of you. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway then descends somewhat towards a plantation of white and black poplars. This is the first time we have encountered here cows in hundreds of kilometers. They graze under the trees, where the small stream of Valdeasneros flows. |

|

|

| Beyond the trees, fields are back. In this country where the ground and the sky are one, the fields seem immense, right? You don’t need to see them to find out. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a ruin emerges from the fog, sepulchral and ghostly, like a gigantic question mark. |

|

|

| The pilgrims are nothing but shadow puppets which slide furtively under the horse chestnut trees. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a picnic spot under the trees, very ridiculous this morning. Europe has spent a lot of euros to humanize the way. |

|

|

| Fortunately, from time to time there is a point of reference to prove to yourself that you are moving forward and not that you are going backwards. Here the pathway crosses the Utielga stream. Walking, getting rid of the haunting presence of endless fields, clearing the fog from your eyes, that’s the delicious program. |

|

|

| You soon covered almost 8 kilometers, and did not see the time pass in a space that resembles the night, when stops a bus near a small road which crosses the pathway perpendicularly. |

|

|

| It’s Saturday, and the bus is unloading Spanish tourists, probably local, who may come to try a little the Camino. Here in the region, they have little choice to go hiking in the mountains. Like us, they will therefore have to take advantage of the flat immensity of the Meseta. Another detail to report. Today in Spain, they are renewing the authorities. So, the Guardia Civil goes back and forth on the road. Do they really fear a terrorist attack? You will find that the police are present everywhere in Spain when there are crowds, even in the markets. |

|

|

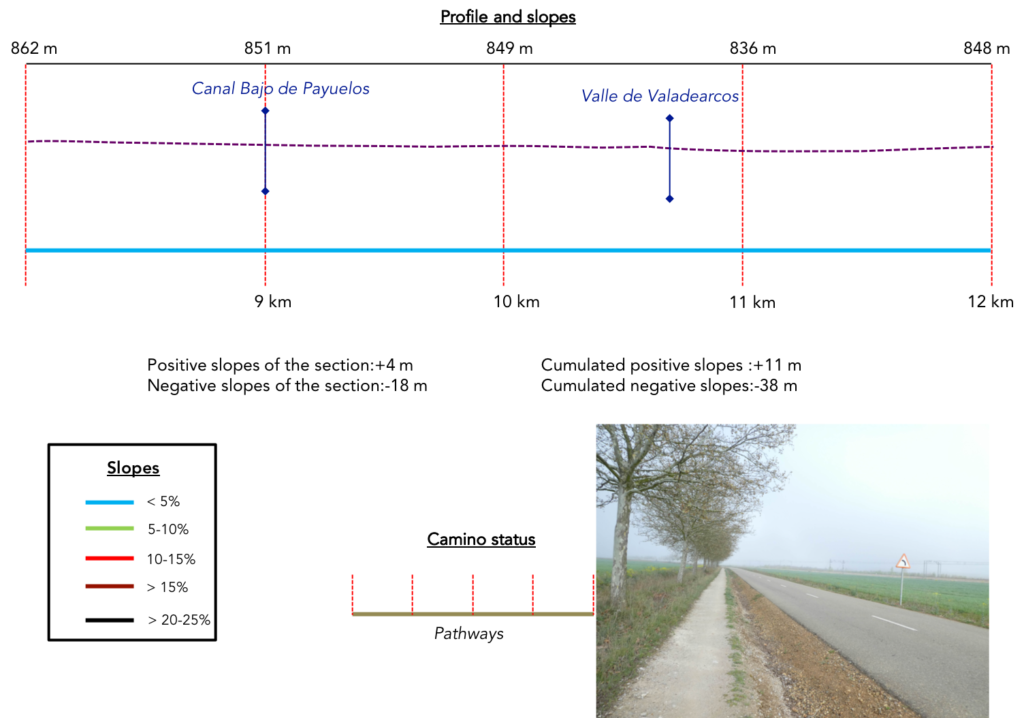

Section 3: Between the canal and the railway track.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Nothing really changes, neither the fog nor the country. Sometimes rapeseed grows along the fields. Why does it always choose to grow on the banks, the seeds carried by the winds at the edge of the fields, when there is no rapeseed field near here. At least, at first glance! |

|

|

| Today the fog gradually dissipates when the pathway arrives at the Bajo de Payuelos canal, a gigantic work of about thirty kilometers long, recently completed, paid for greatly by Europe. |

|

|

This canal, which draws its water from Rio Esla, which can be found in Mansilla, can irrigate more than 40,000 hectares.

| Soils must be relatively impermeable here, where rainwater is also collected in gutters for more artisanal irrigation. |

|

|

| And the pathway continues its straight walk along the horse chestnut trees. It is approaching a railroad track. In the distance you hear a train buzzing and honking over and over again. |

|

|

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway runs under the railroad track. Here, it’s no longer the TGV line. Only freight trains, numerous in the country, run through. On the roads, along the Camino, you never come across heavy trucks. Should we conclude that the transport of goods takes place mainly by train? We cannot say, especially as the highway does not pass far from here. |

|

|

| Beyond the railway, the Camino ends up in the small valley of Vadearcos… |

|

|

| …where a stream meanders under the poplar plantations. |

|

|

|

|

| Shortly after, another picnic spot under the trees… |

|

|

…beyond, you’ll find these huge fields, which sometimes you do not see the end, which sometimes you have the feeling that they cover a good quarter of Spain. And, it’s true. When you talk a little with the pilgrims on the way, one day drives out the other. Is it to see the snow-capped peaks of Cantabria in the distance that makes them happy? Yesterday they were grumpy, hardly responding, jaws clenched, staring. Today they are almost mischievous, laughing. And yet, it’s the same landscape, the same track, the same road, the same horse chestnut trees. But there! First, the stage is shorter, then they stride closer to the end of the Meseta. Then, coming back home they can say “We did it, the Meseta”. And the amazed people will look at them with their mouths open, because they don’t know what the Meseta is, or what country it is in.

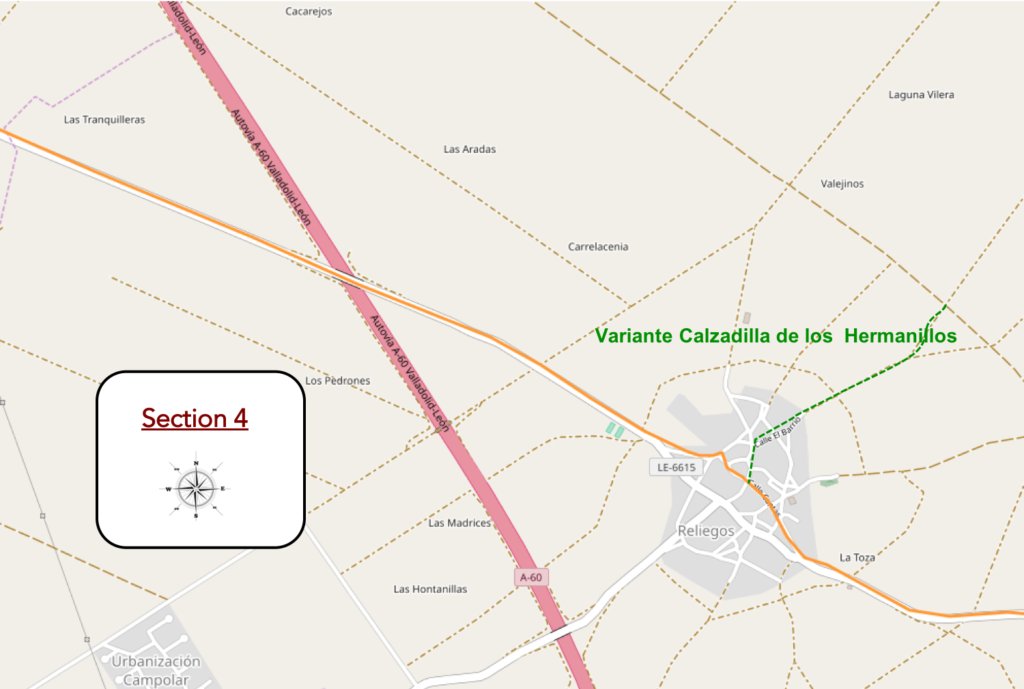

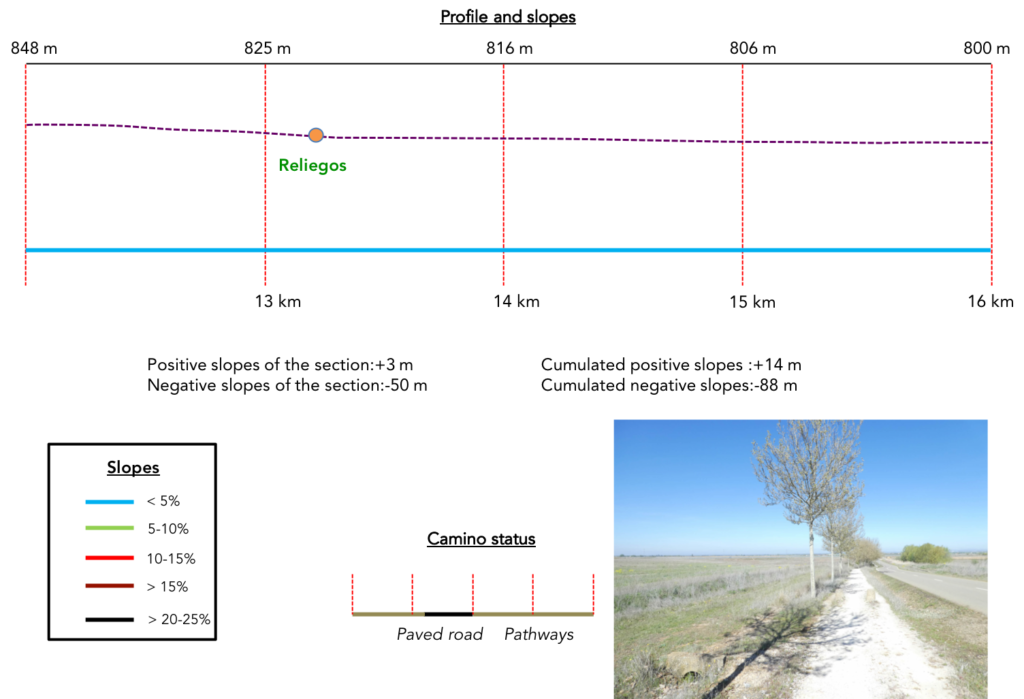

Section 4: You will cross the highway again.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway is still nearly a kilometer on the plateau, in this immense plain where the gaze is panicked. |

|

|

Here, the crucero is massive, lacking in elegance. As usual, these crosses punctuate the course.

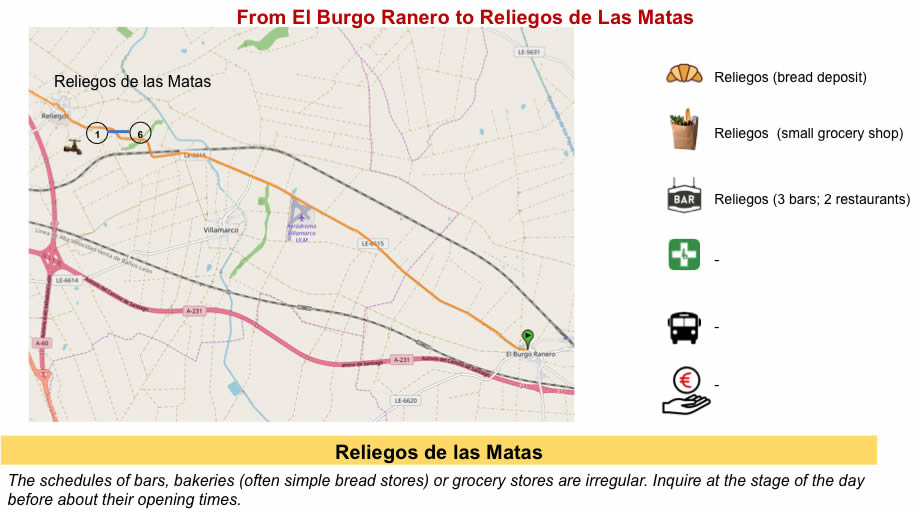

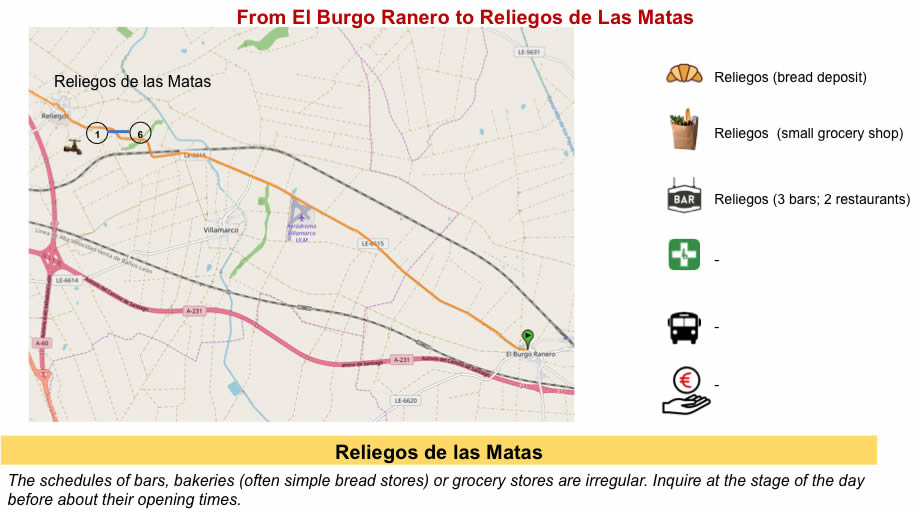

| Further on, the pathway slopes down very gently towards the village of Reliegos. Everything is compact. In northern Spain, nothing exists outside the villages. In the Meseta, life here is only conceived as collective. And it’s an old story. This dates back to the Reconquista period, when people realized that it was easier to defend themselves by being grouped. |

|

|

| It is in this poor village that the variant of Calzadilla de los Hemanillos returns, which separated from the “Camino real” shortly after Sahagún. Few pilgrims take this way, and yet it is a Roman road, the Via Trajana. But can a Roman road compete with a “real” track in Spain? |

|

|

| The full name of the village is Reliegos de Las Matas. Matas means brambles. You crossed them in abundance on the way. Nor do the guides say where a small meteorite fell in the brambles last century. In the village reign brick and adobe. The church has been tinkered from here and there, with a pinnacle. Honestly, would you have stopped in this polyglot bar in normal times? |

|

|

| The church was cobbled together from odds and ends, with a steeple. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, near the padel court, there is a small park with a recent monument in homage to St Jacques. |

|

|

Sincerely, you wonder why the sculptors of the Camino francés have almost always considered showing a St Jacques as a paunchy and severe old man.

| Then it’s again the straight line on an incredibly huge plain. It’s flat and the only bumps you can see are man-made bumps. It is a safe bet that from north to south the width of the plain must be around 100 kilometers, as in the American plains. You will never see such immensity elsewhere in Europe. |

|

|

| Here, the moor sometimes replaces the crops. And a bump, here is just one. |

|

|

| In an area where 10 airports could easily be built next to each other, the A-60 freeway, the highway that runs from León to Valladolid, passes, non-discreetly. The least you can say is that you don’t push yourself through the gate here. |

|

|

| And in this endless universe, a small patch of lawn, with free stalling cattle. The peasant comes here with his 4×4 to inspect his cows, calves and bulls. The bulls here are probably not part of the breed bred for bullfighting, found in Castile in the south, near Salamanca, but especially in Andalusia. But who knows? |

|

|

| And not surprisingly yet, the Camino sets off again in a straight line on wide open spaces. But, by scanning the horizon, you’ll see that it is gradually approaching inhabited areas, or at least industrial areas. |

|

|

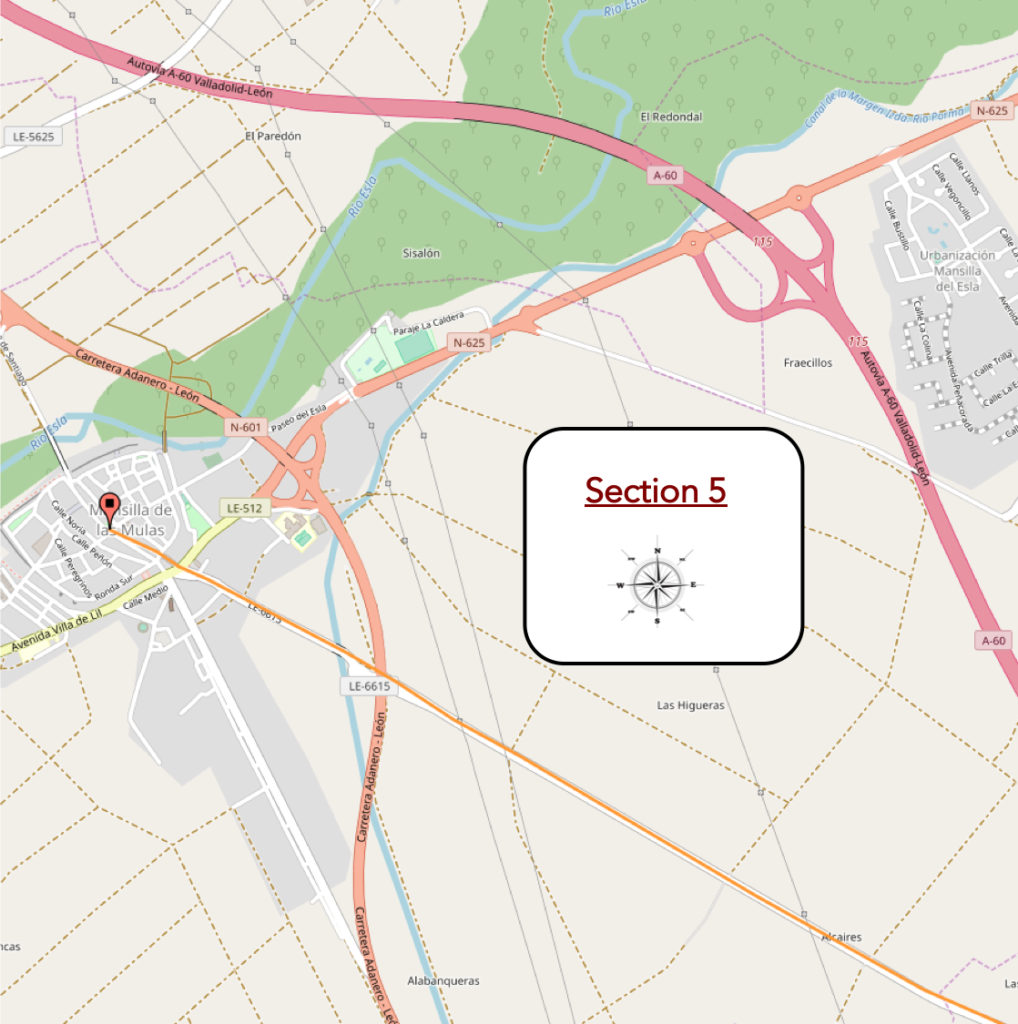

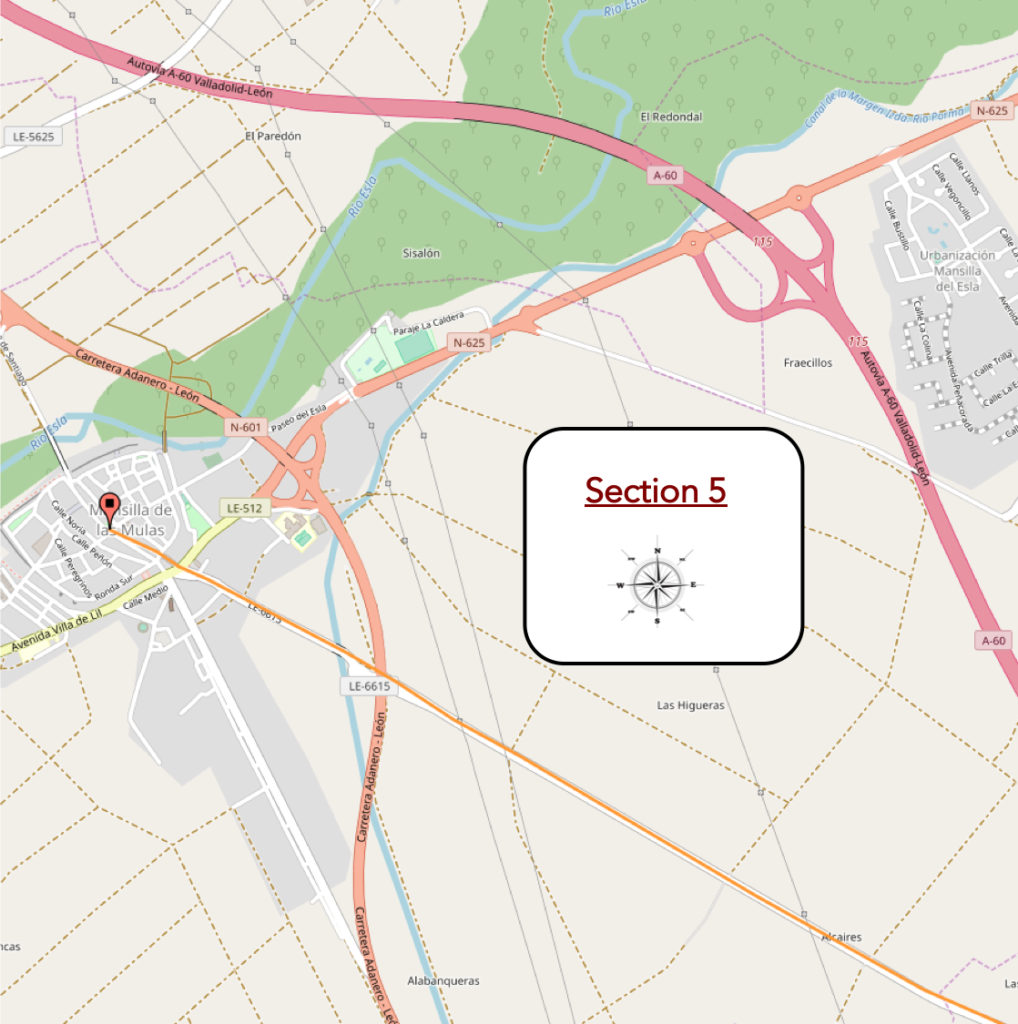

Section 5: There is no longer a single mule in Mansilla.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway then crosses a mixed zone where cultures are still mixed, but also the moor. |

|

|

| There are farms behind the gates, and even a nice dump. |

|

|

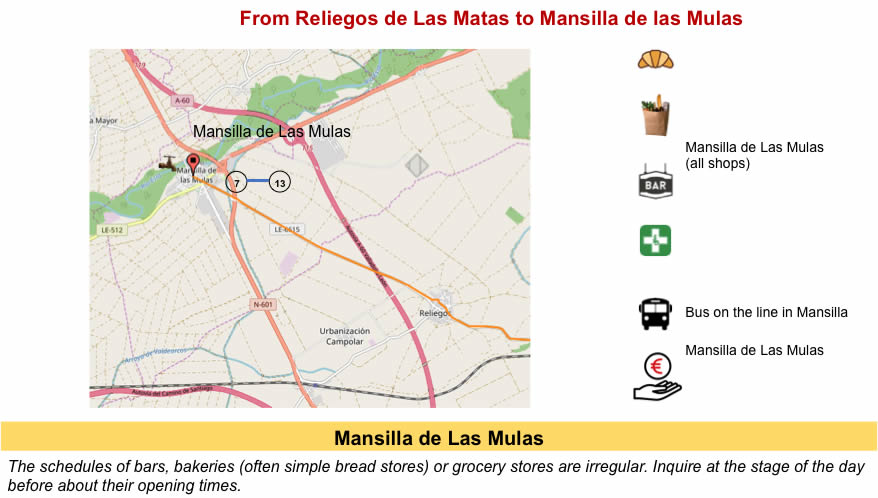

| The pathway soon gets in view of Mansilla de Las Mulas, runs on a national road which leaves the borough. |

|

|

| Below flows the Margen Canal. Another one of these great works for irrigating fields. |

|

|

| It is the first borough that you find beyond Sahagún. |

|

|

| The borough, like all the others in the region, experienced a great development in Roman times, when many Roman roads crossed in the Meseta. Then, in the Middle Ages, it was protected by its ramparts of which there are many traces, near the Esla River. It experienced a great boom during the expansion of the Camino de Santiago. Here there were 7 churches and 4 pilgrim hospitals. They had to welcome the million pilgrims who wandered on the way. But no one has ever been able to confirm this astronomical figure. Today, the borough which has kept a fairly old, but not medieval aspect, as claimed in the guides, has less than 2,000 inhabitants. |

|

|

| Mules, they used to be here when the borough was the center of a great cattle fair. All that has disappeared. The borough is quite nice with its many squares, and here you can see people in the street. The name of the city is derived from Mano de Silla (hand on the saddle). The coat of arms of the city represents a hand leaning on a saddle. |

|

|

| Nothing remains of the churches of the past. The parish church of Santa Maria, rebuilt on the site of a XIIIth century church is recent, from the XVIIIth century. Another pinnacle is visible in the center. But it is no longer a church, it is the municipal administration. That day they voted in Spain and the Guardial Civil crisscrossed the district. Our ad hoc polls have shown that in the region people votes for the right, but it is the left that has renewed power in the country. |

|

|

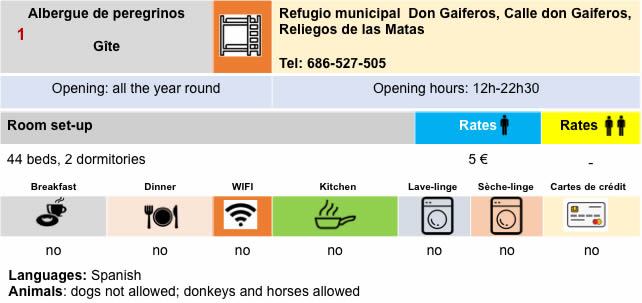

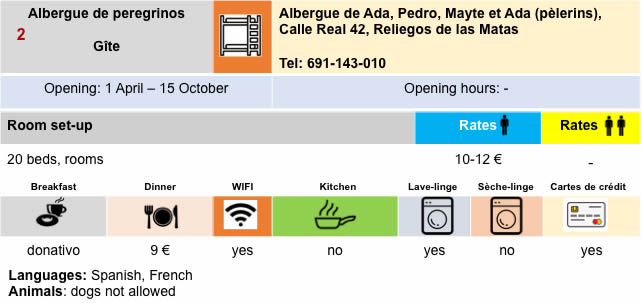

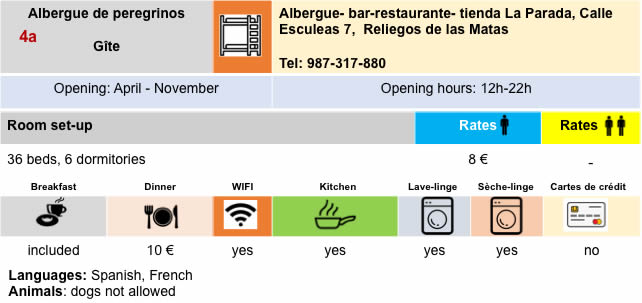

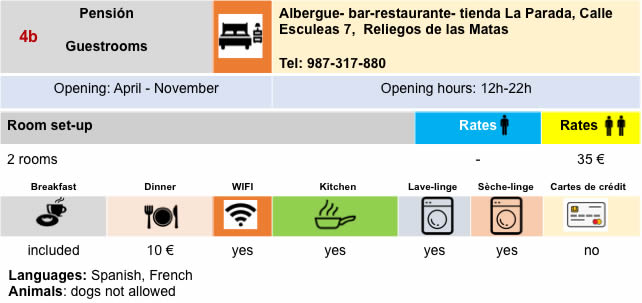

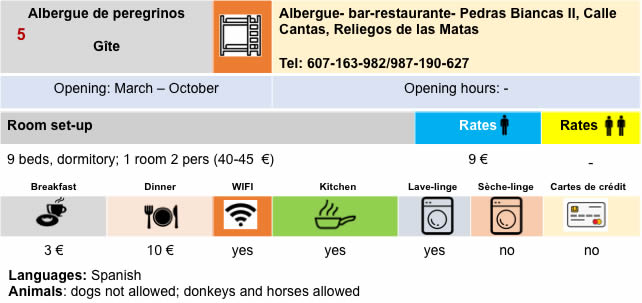

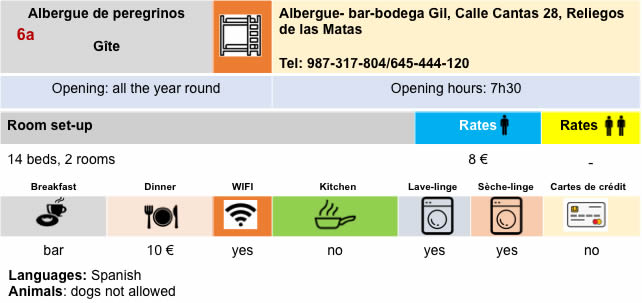

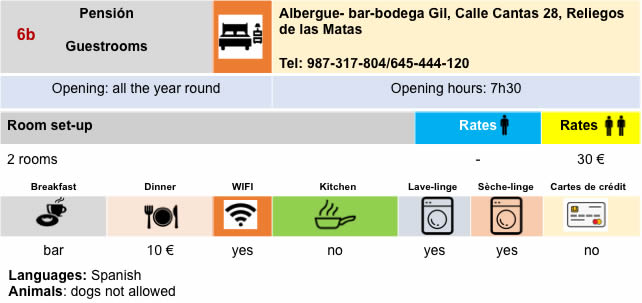

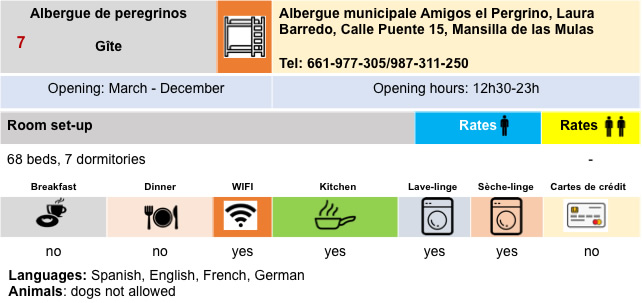

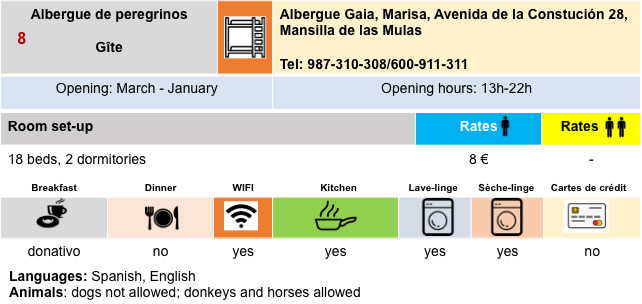

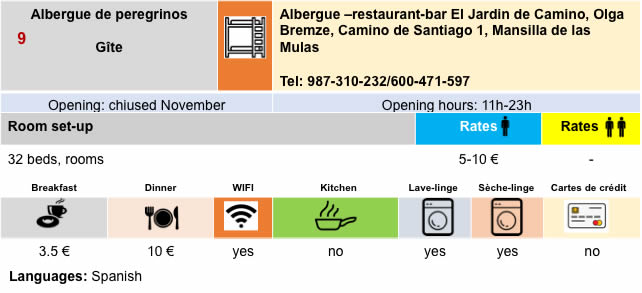

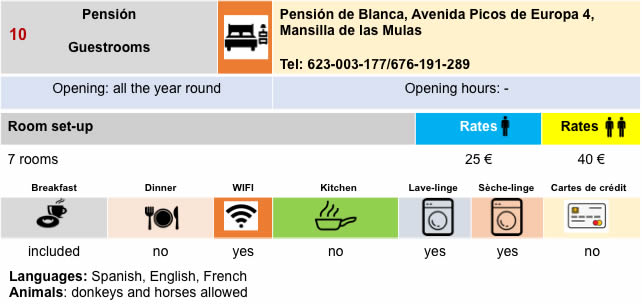

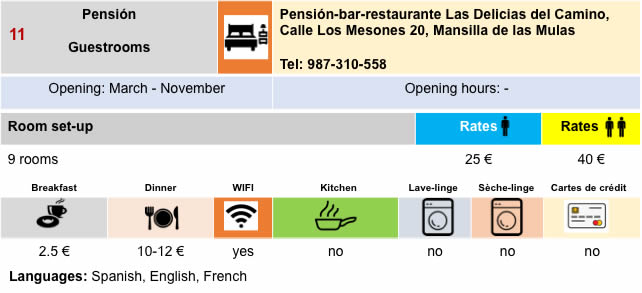

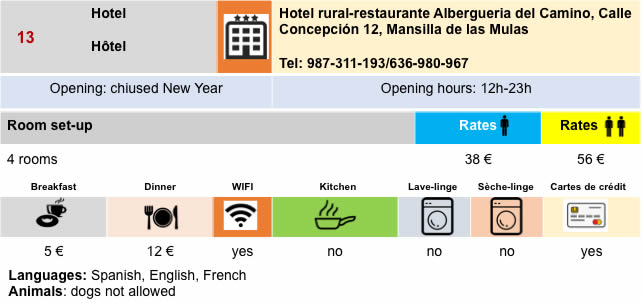

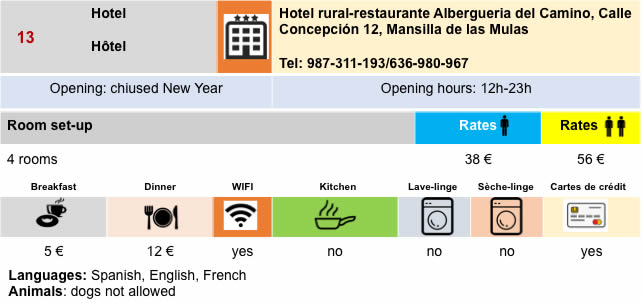

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 20: From Mansilla de La Mulas to León |

|

|

Back to menu |

>

>