A beautiful city, almost at the end of the Meseta

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

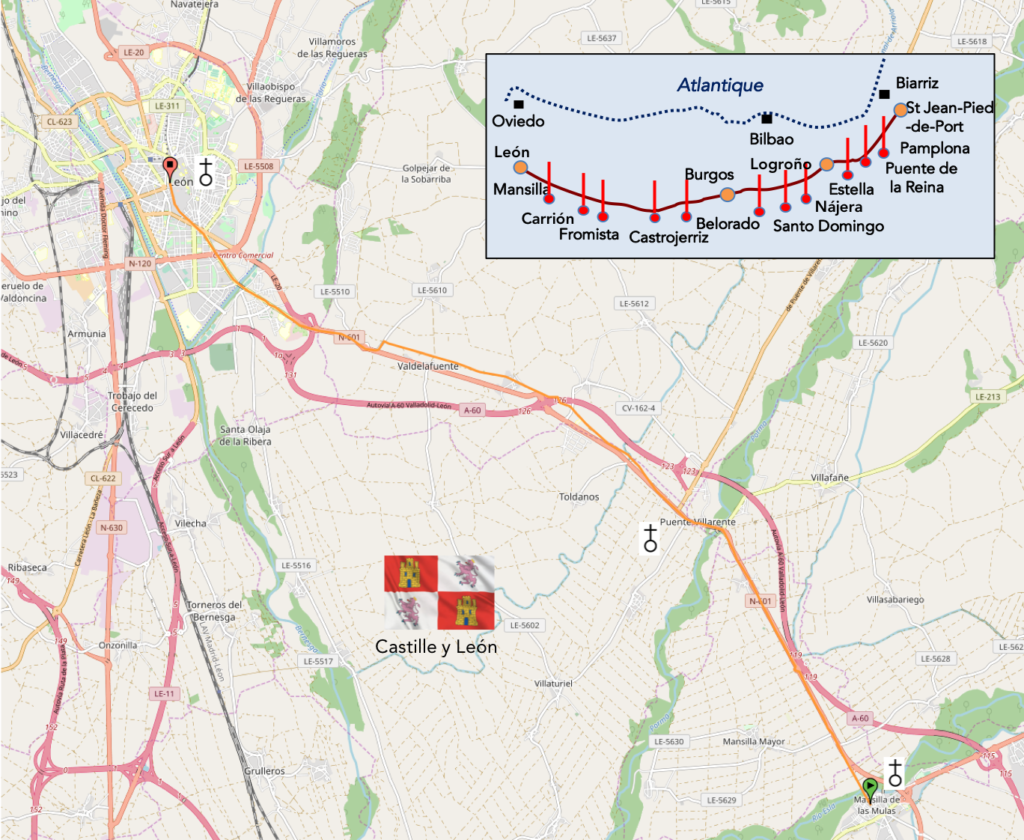

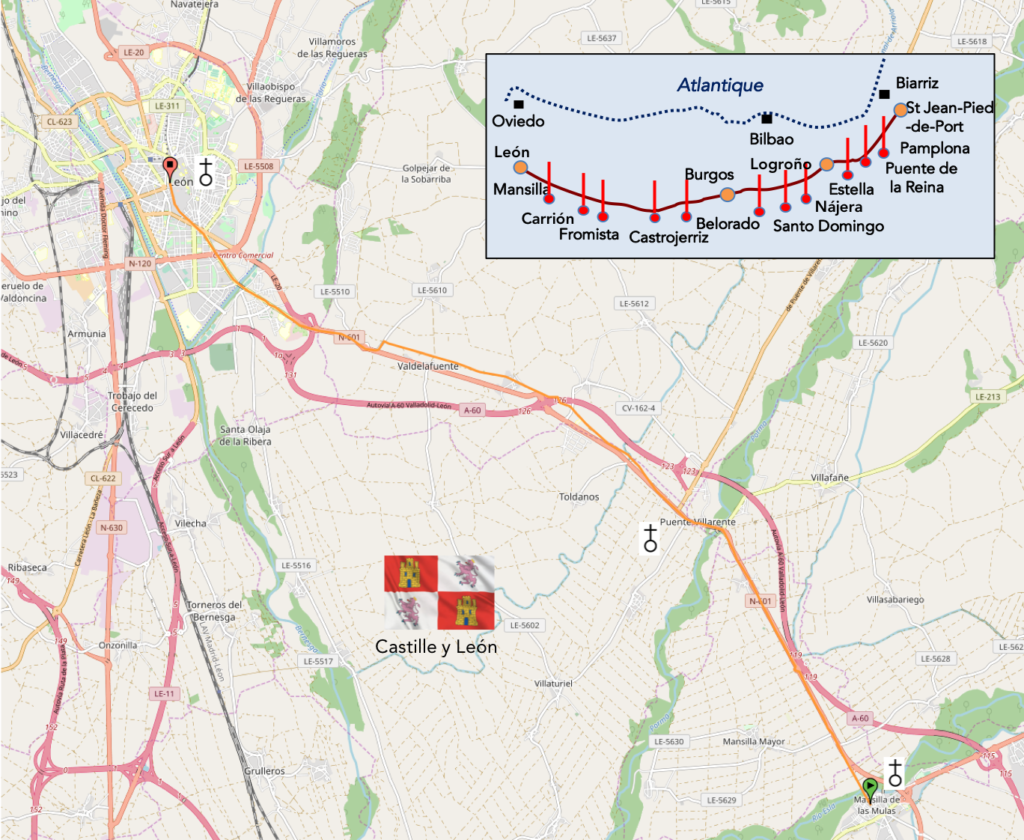

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-mansilla-de-la-mules-a-leon-par-le-camino-frances-33935923

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today, the infinite fields are behind you. You will have to learn to forget this bare high plateau, where in summer the midday sun is more formidable than elsewhere, this “green hell” in the freezing spring, where the wind blows the drizzle and all its aggressiveness in your face. In two days, we know that the country will change. Certainly, there will be hints of the Meseta, because the central Meseta continues further west. But, for you, you are going to turn sideways, see the hills come into being, and soon the mountain. Today is therefore a full day of transition to the city. The route will not always run through sites that trigger excitement, but it is almost always so when approaching cities. It’s actually little countryside, from the rather semi-urban landscape to the city.

León, on the banks of the Río Bernesga, is the last major town on the Camino before Santiago to the west and before the climbing through the Cordillera Cantabrica mountains to the north, into the Montes de León. It is the capital of the province of León, which is the largest in the autonomous community of Castilla y León. Contrary to popular belief, the name León is not derived from the lion (león in Spanish, featured on the city’s coat of arms), but rather from the Roman legion. The origin of the city dates back to the Romans, who settled here to control the transport of gold from the Bierzo gold mines to Rome. Founded as the Roman military encampment of the Roman Legion, it was the military capital of the peninsula until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476. When the Roman province of Galicia was created in the 3rd century, León was integrated into it. León was Christianized in the 3rd century, becoming the oldest bishopric in Western Europe. The City of León played an important role in the history of Spain during the first centuries of the Reconquest and King Ordoño I succeeded in integrating the city of León into the Kingdom of Asturias, rebuilding the city. At the beginning of the Xth century, León became a kingdom. Kings succeeded one another here, extending as far as Valencia and Toledo. At the beginning of the XIIth century, the last king of León, Alfonso IX, convened the first parliamentary assembly in European history. Since 2013, the city has been declared the cradle of parliamentarism by UNESCO. Ferdinand III, the son of Alfonso IX, by his mother also became King of Castile. From then on, from the year 1230, the kingdom of León merged with that of Castile.

It is not the purpose here to tell you again the history of Spain and Castile in particular. Let us say here that dynasties reigned, from the House of Navarre to that of Trastamare, from the XI1th century to the XVth century. It is with the arrival of Charles-Quint, son of the famous queen of Castile, Isabella the Catholic, that the separate history of Castile ends, which then merges with that of royal Spain, under Philip II, son of Charles V. In fact, Castile has changed its capital several times. At first it was Burgos, then León, then Toledo, and finally Valladolid, which is still the capital of the province today. It was Philip II, who on a whim removed the rank of capital of Valladolid for Madrid, which was then only a small town in New Castile.

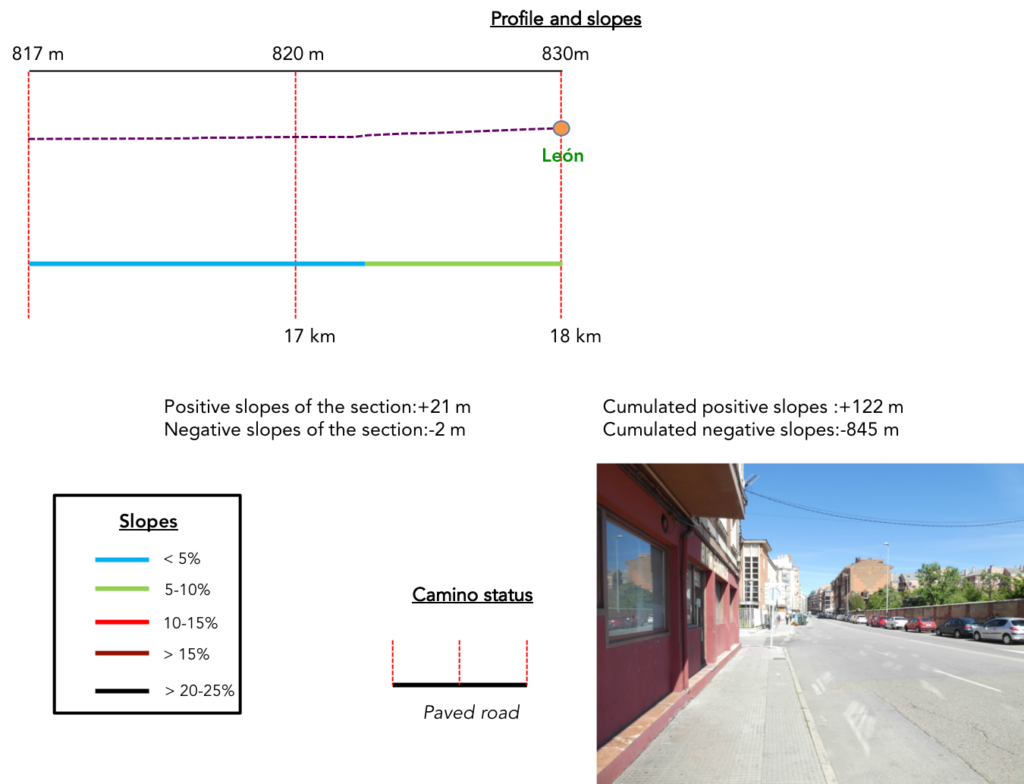

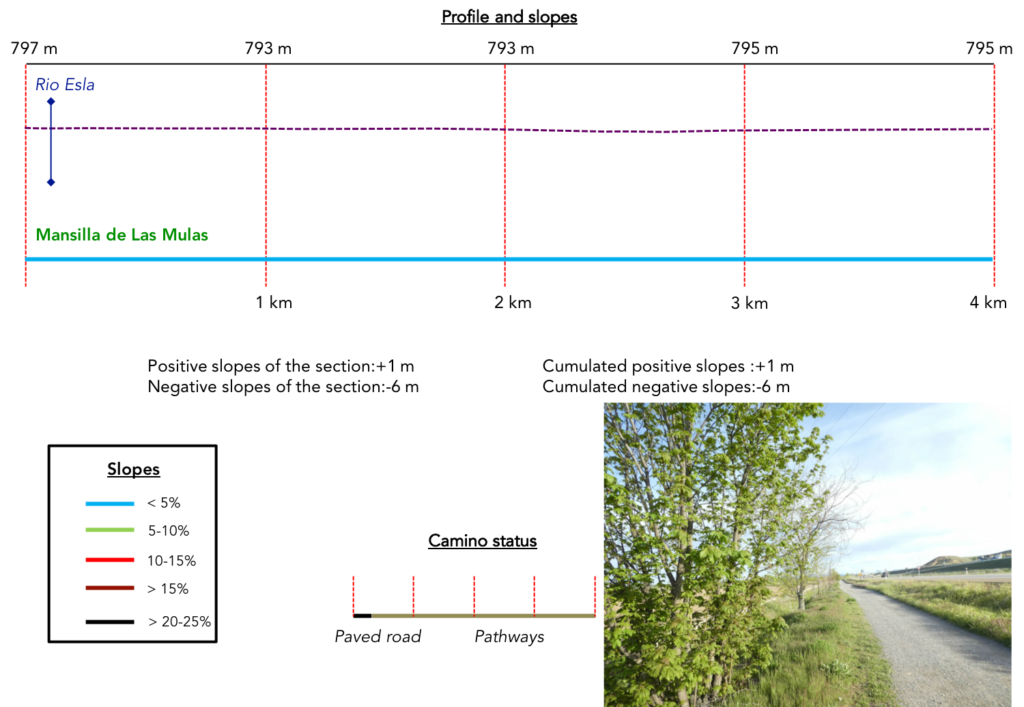

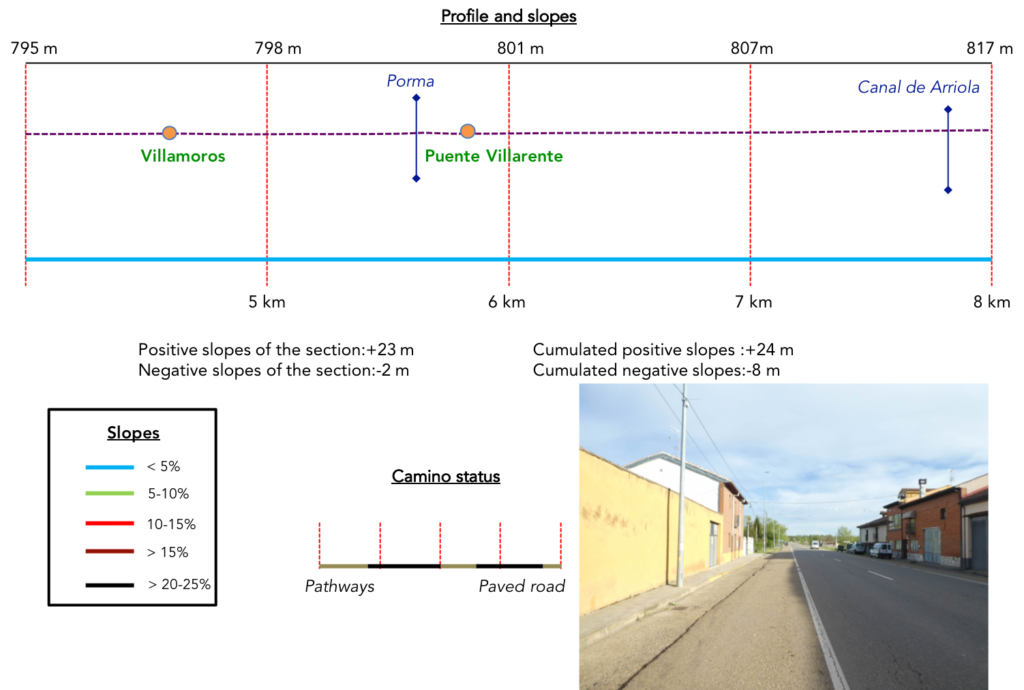

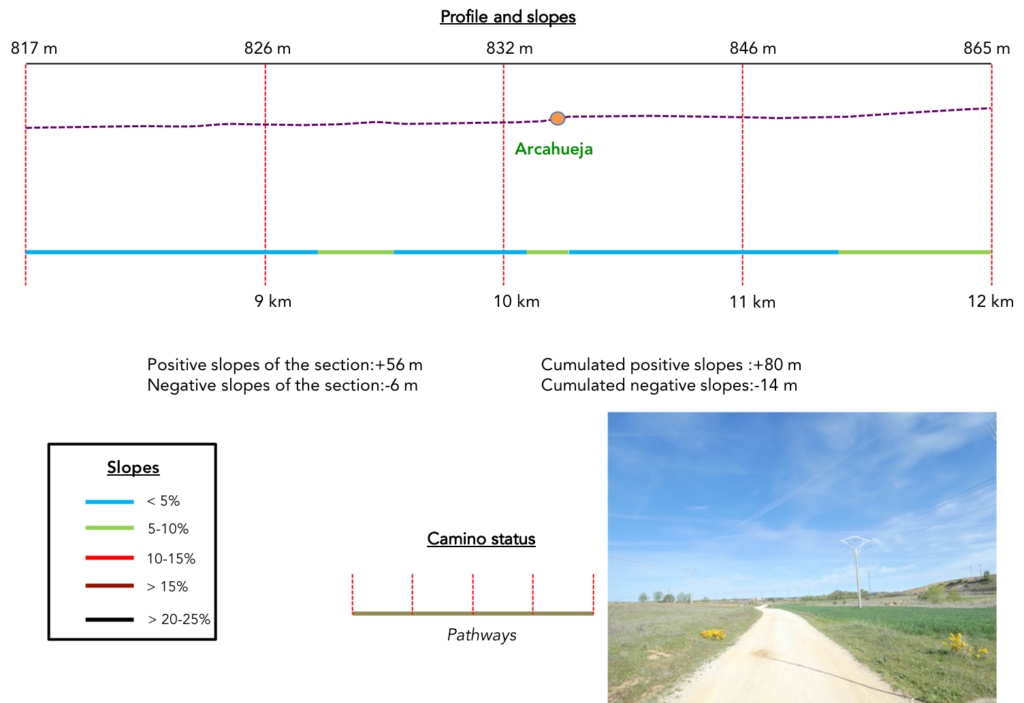

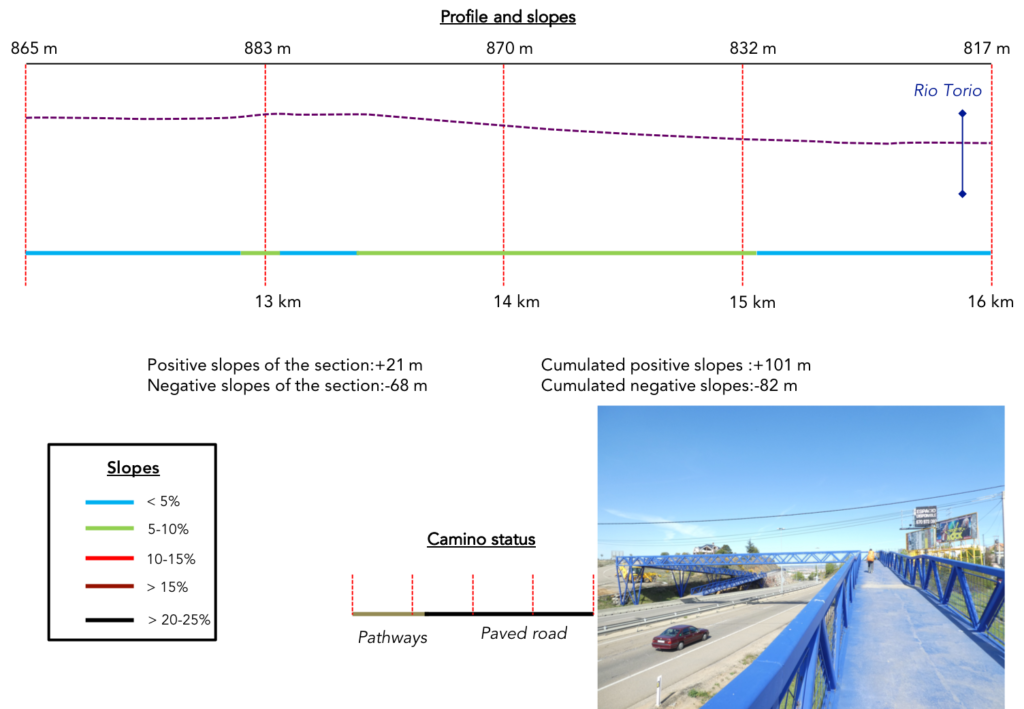

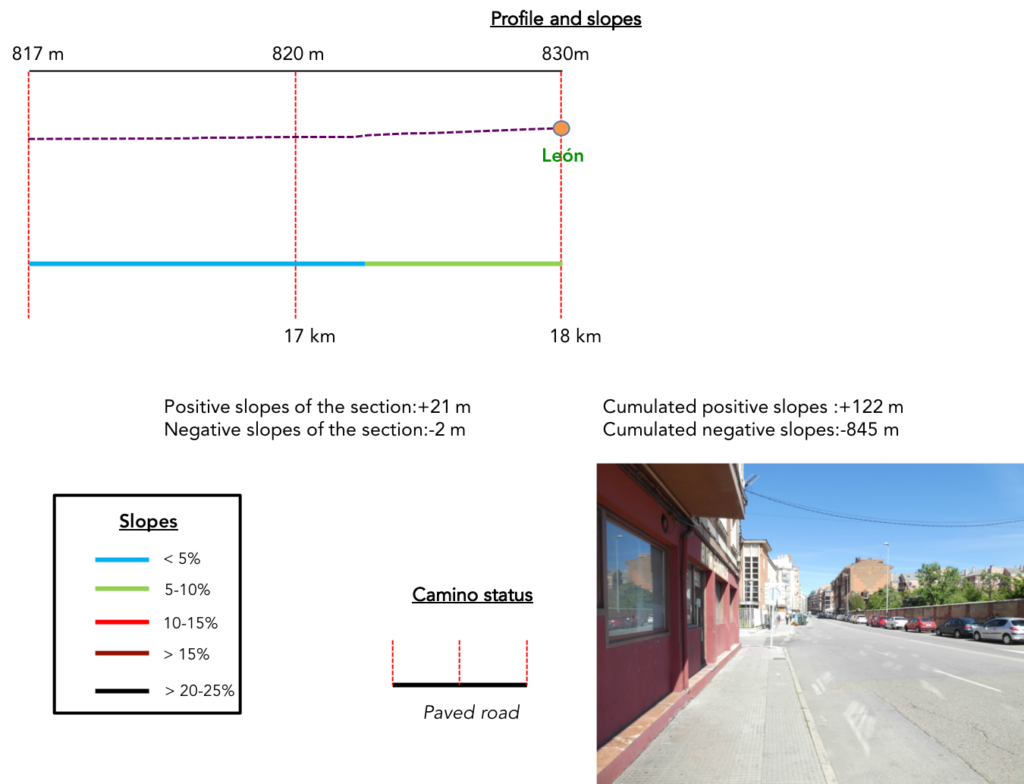

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the stage (+122 meters/-84 meters) are again weak. There is hardly anything but a small bump before arriving in town, but nothing very significant.

Today there are a few more trips on the paved road. You’ll be walking near a big city:

Today there are a few more trips on the paved road. You’ll be walking near a big city:

- Paved roads: 7.4 km

- Dirt roads: 10.6 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

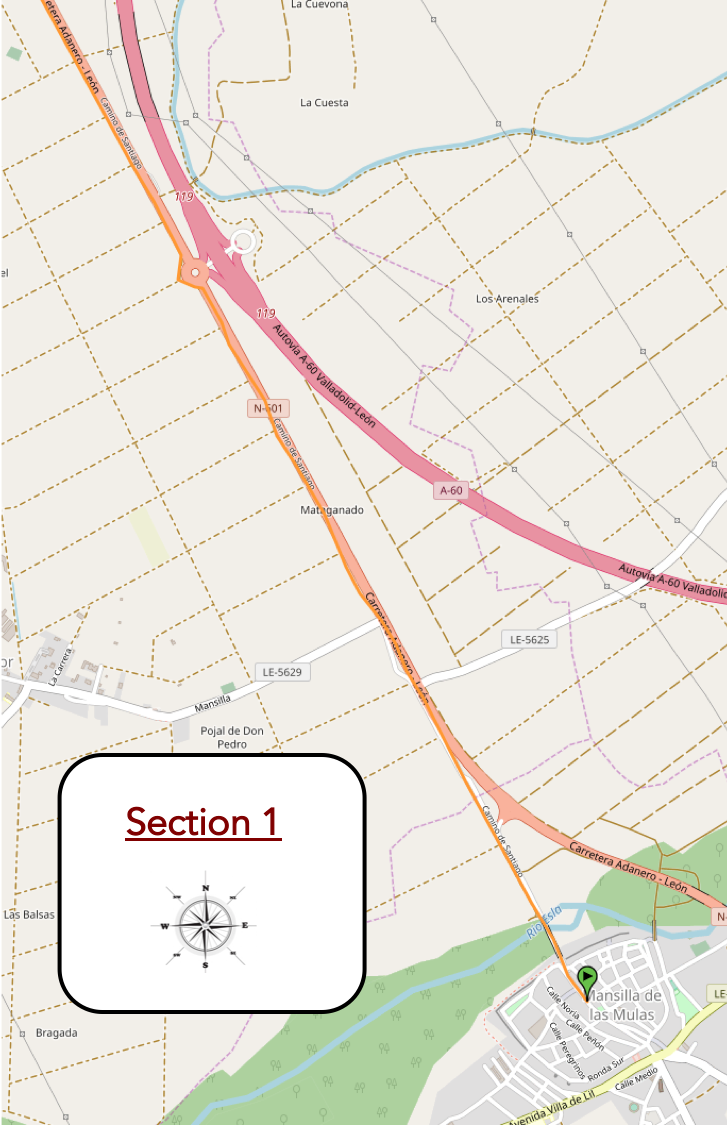

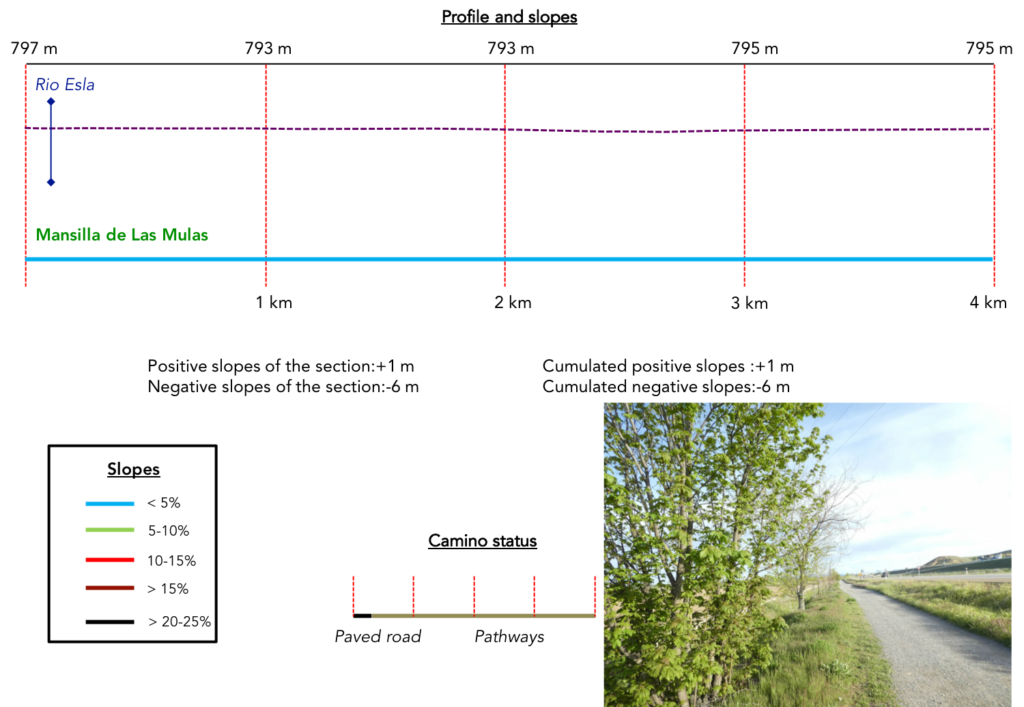

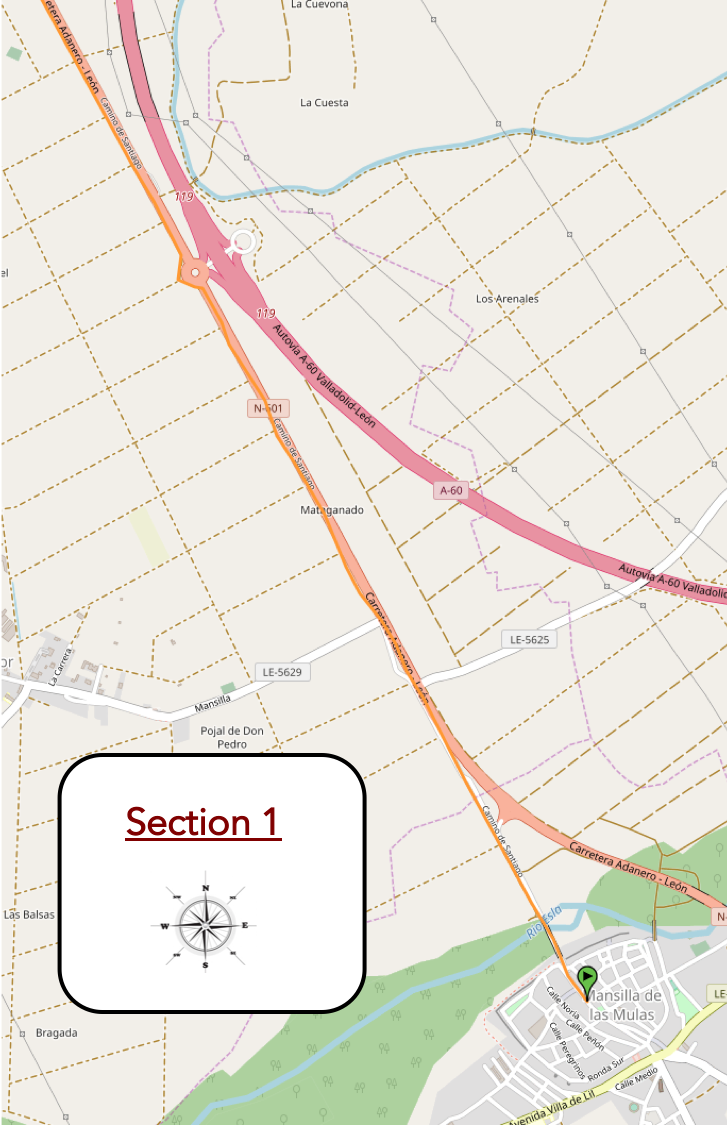

Section 1: Along the national road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The Camino leaves Mansilla de Las Mulas in a square near the old walls. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, there is a long one-way bridge over the Rio Esla, a wide river which flows here, again under the poplars. |

|

|

| Here, there is no longer any “Camino real” with its horse chestnut trees. But that doesn’t change anything ordinary. It’s still a wide path running along the busy N601 road, which goes to León. |

|

|

| These are always the fields you’ll cross. Even if the altitude is a little lower, 800 meters above sea level, the trees, if not the poplars, have not yet resumed their foliage. The vegetation is a little more varied. Here there are even beech trees, a species that you have very rarely encountered so far on the way to Spain, if not at the beginning of the Camino, where they were very numerous. |

|

|

| Here, pilgrims are encouraged to make a detour to visit the Monastery of Sandoval. But it’s a lost cause! Today the pilgrim program is very clear. They have to get out of this Meseta very quickly, which becomes tasteless, to finally reach a city. It will soon be almost 200 kilometers from Burgos without having seen a real city again. |

|

|

| Sometimes the traffic is somewhat heavy on the national road. Motorists here can do their daily statistics on the number of pilgrims who advance here in single file. |

|

|

| Here are some maples that have already returned to their leaves! There is no need to say, we went down a bit in altitude. |

|

|

| Beyond the roundabout, the pathway flattens straight as usual. |

|

|

| Here, you’ll find again these ingenious concrete irrigation canals. |

|

|

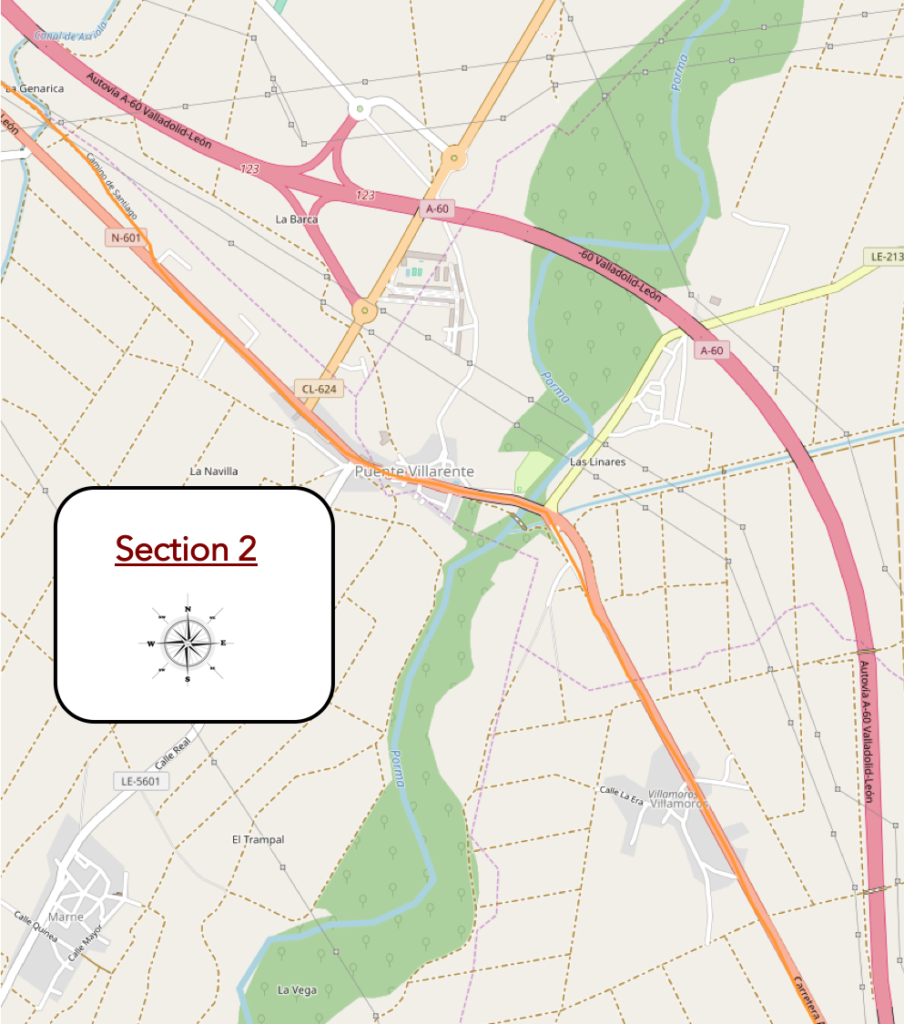

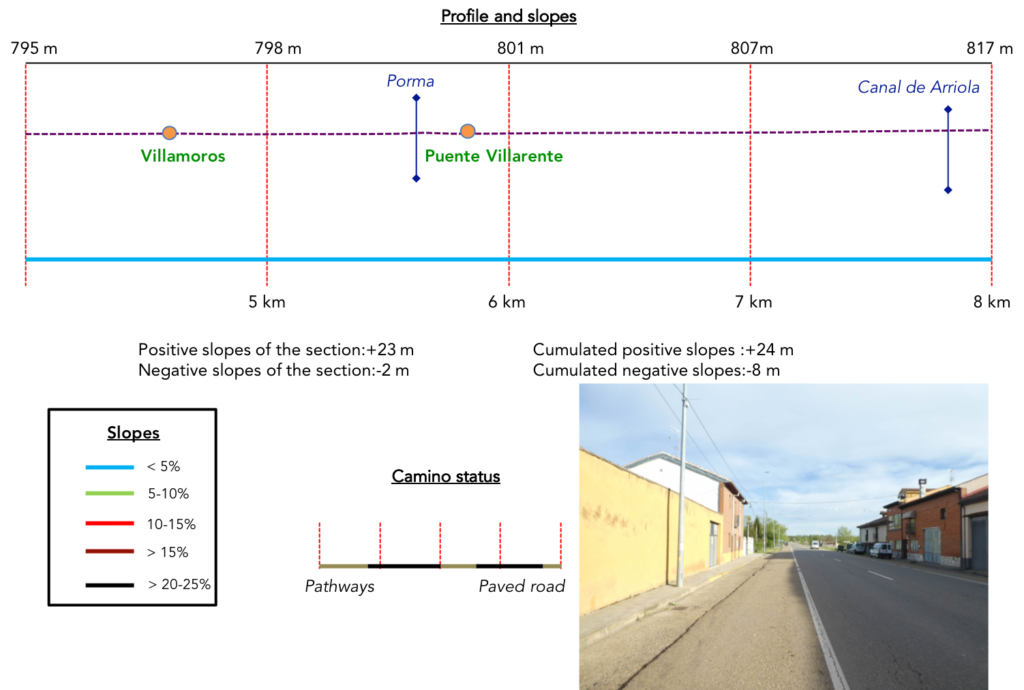

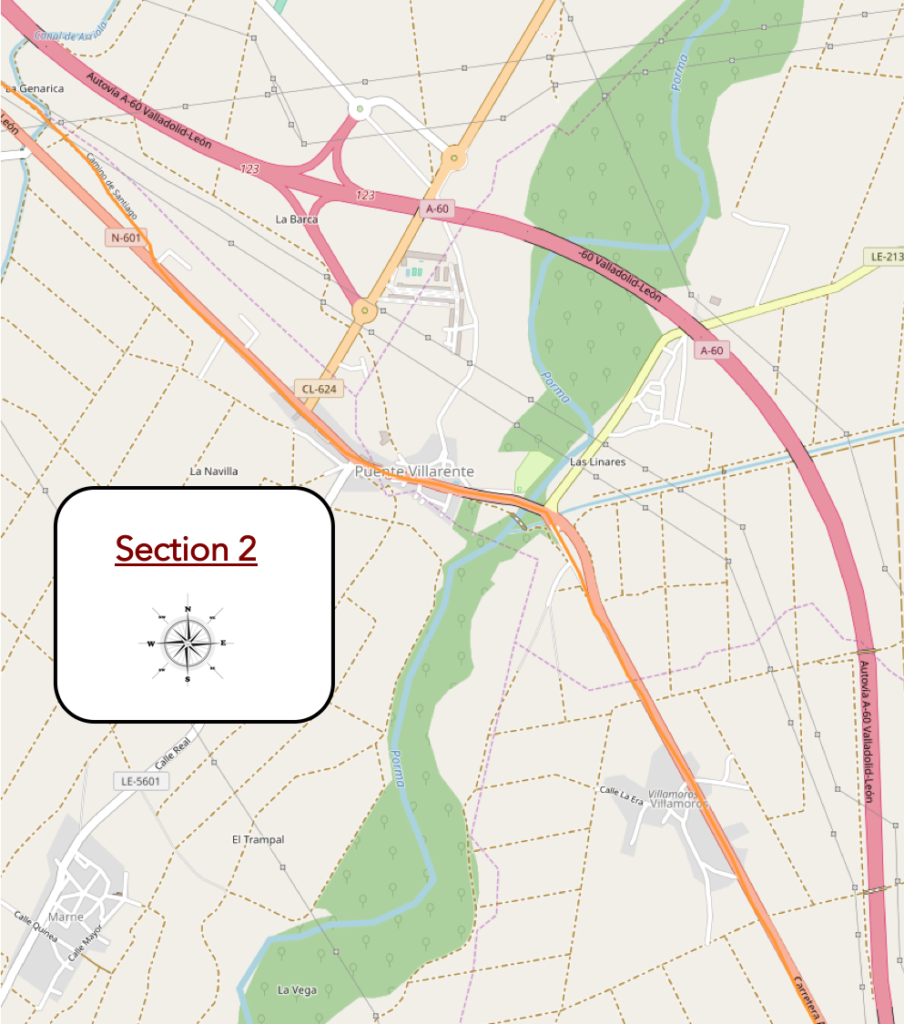

Section 2: Through village and small town on or along the national road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The straight pathway will lead you to Villamoros village. |

|

|

| It is then a long crossing of the village, but still beyond, which awaits the pilgrim, on the edge of the national road. |

|

|

| A little further, the Camino leaves the paved road for a parallel pathway which runs towards the wood in the meadows, where you’ll find cattle in free stabling. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway then finds black poplars in the wood. |

|

|

| Here, under the bridges flows serenely Porma River. The Spanish have indeed pretty big and beautiful rivers. |

|

|

| There, the Camino crosses the borough of Puente Villarente for a long time on the national road. Here is already the city, a large suburb of León. |

|

|

| Towards the end of the borough, the Camino leaves the paved road for a dirt road, here called Camino de Santiago (what a surprise!), which heads into wasteland, heathland, and small industrial areas. |

|

|

| Quickly, the paved road gives way to the dirt road. Here, the pathway finds a bit of serenity among the dry grasses and wild cypresses, very present on the way from here. It is most often the motley moor that dominates. |

|

|

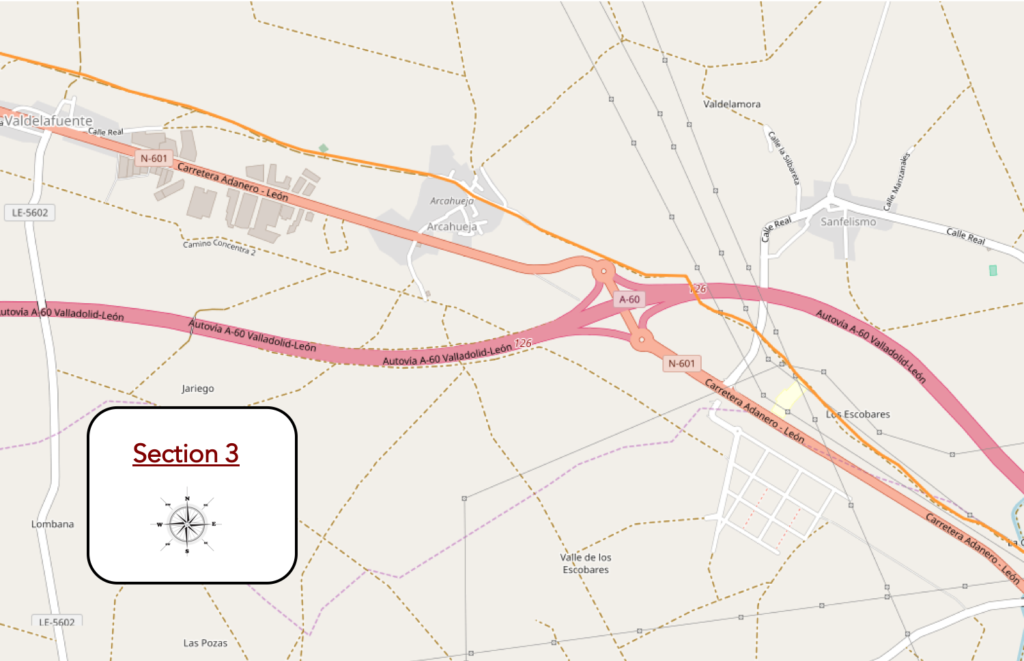

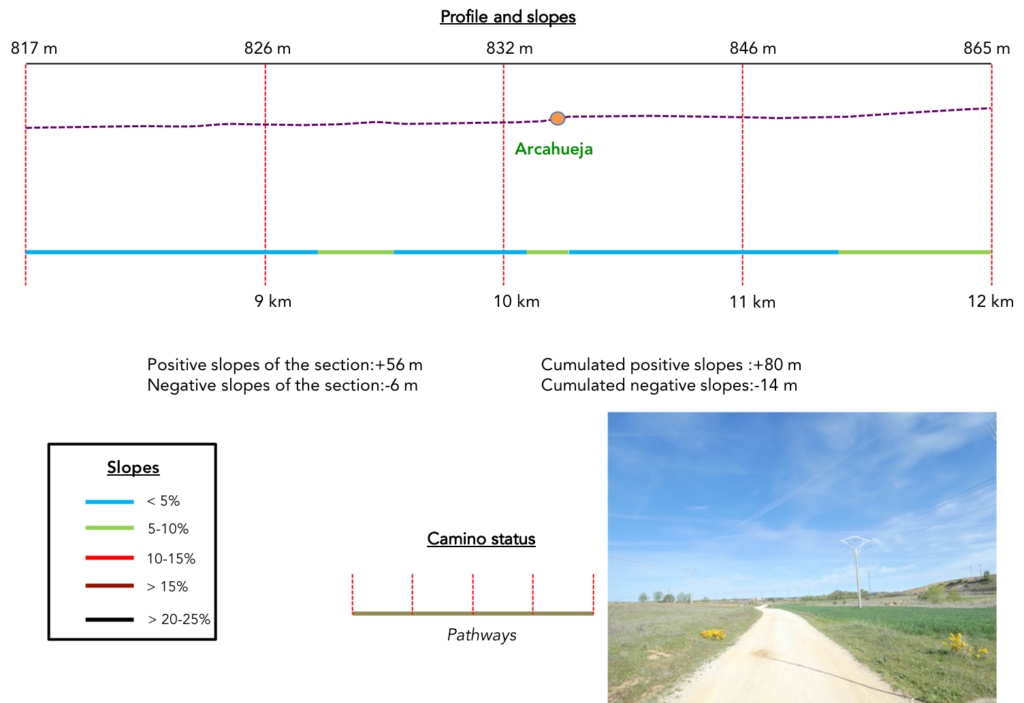

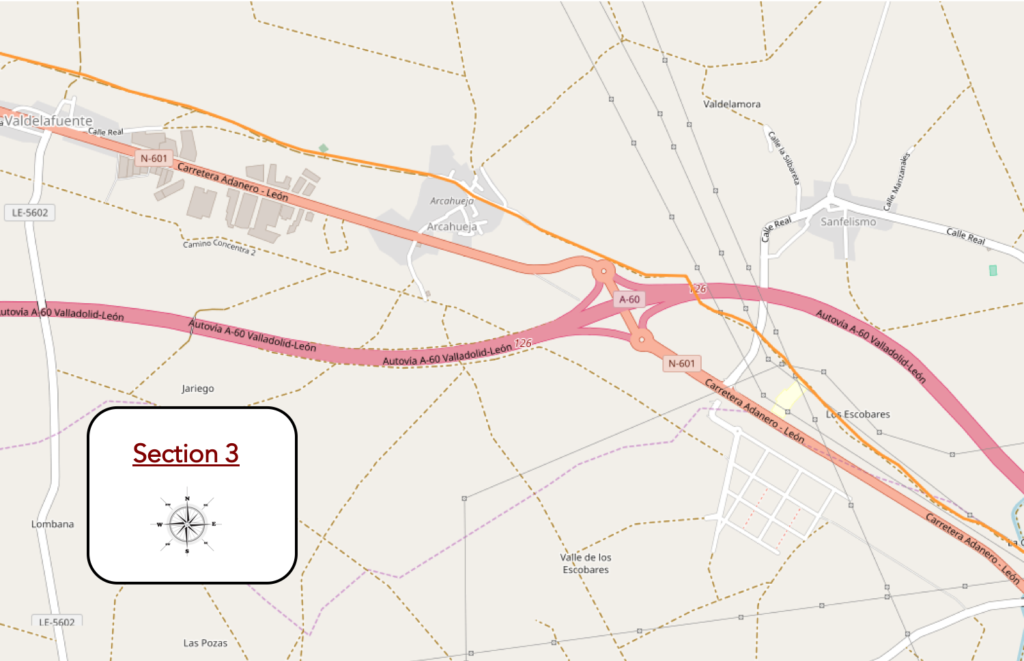

Section3 : Between countryside and industrial zones.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, with a little more slope, but slight.

| In these spaces where sometimes fields adjoin vacant lots, there are also cattle grazing in the meadows. |

|

|

| But more to cattle the country here belongs to the pilgrim. Wherever you turn your head, you can see them here, putting their shoes on, at the top of a hill. Sometimes you get the feeling when you travel to northern Spain, that this country is for the exclusive use of pilgrims. Along the roads, you only see them, in the villages too. Even in the cities, you recognize them when they put down their bags, by their basic clothing, by their sandals. |

|

|

| Further up, under the high-voltage line that cracks in the sky, the pathway arrives near an industrial area. |

|

|

| There, the dirt road heads towards the highway, skirting the industrial area. This is often the case on the outskirts of large cities. |

|

|

| Shortly thereafter, the pathway runs under the A60 motorway. |

|

|

| On the other side of the highway, there is real nature, with meadows. The pathway heads to Arcahueja village. |

|

|

| It has been a long time since the route had experienced such a slope. Almost 10%, yes! |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, you naively expect to see León appear, but this is not yet the case. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway slopes up slightly along some small gardens, buildings on the hill, or semi-industrial islands. But, the pathway avoids running on the side of the industries. The Camino francés is a real institution, and, as far as possible, a free passage has been made for the army of pilgrims. |

|

|

| The climb is quite long and steady on the mound, with, below, a chapel lost in the broom, cypresses and tall grass. |

|

|

| Further up, there is a fork for the village of Valdelafuente. But the Camino does not go there. |

|

|

| Soon, it is the top of the hill, which ends at the level of a cemetery. |

|

|

| Beyond the cemetery, the pathway heads to a new industrial area. It starts to become haunting this transit from one industrial zone to another. For little, you would like to find back the monotony of the Meseta and its fields. |

|

|

Then, at the bend of a small business development, the route returns to the national road, in a large commercial and industrial area, on the outskirts of the city.

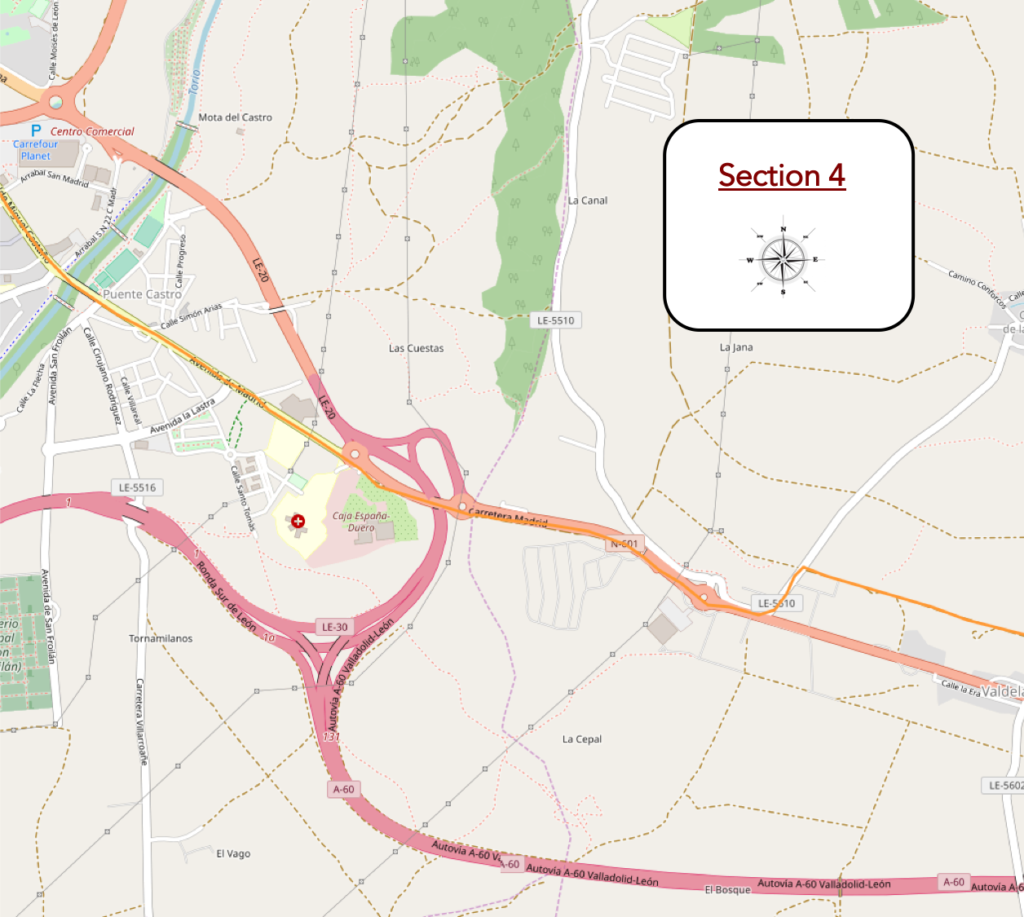

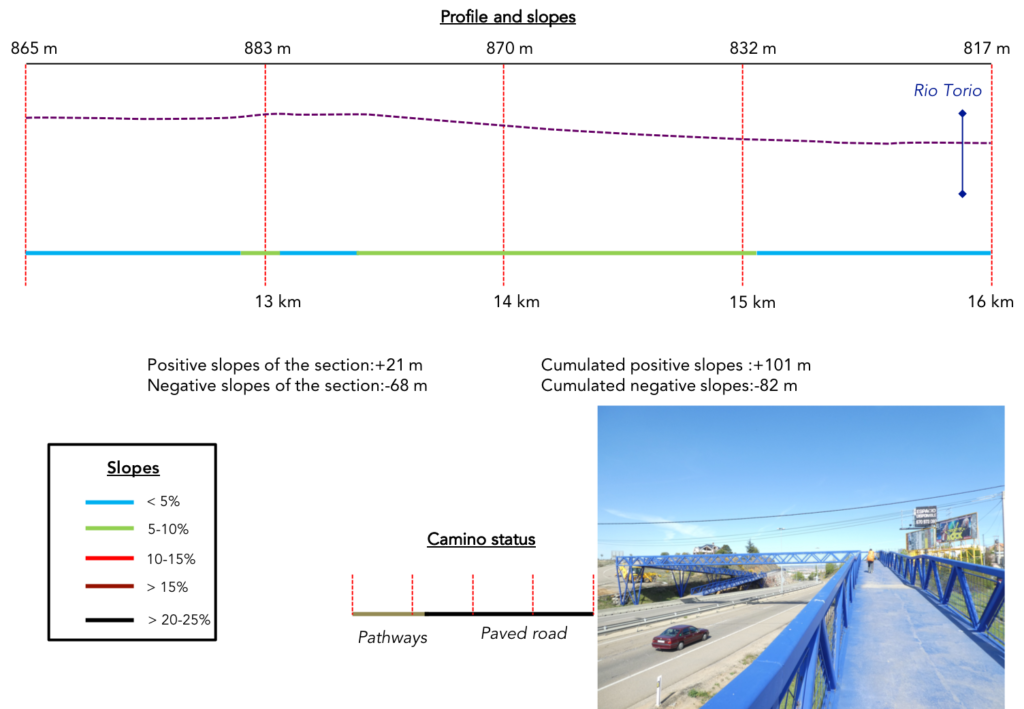

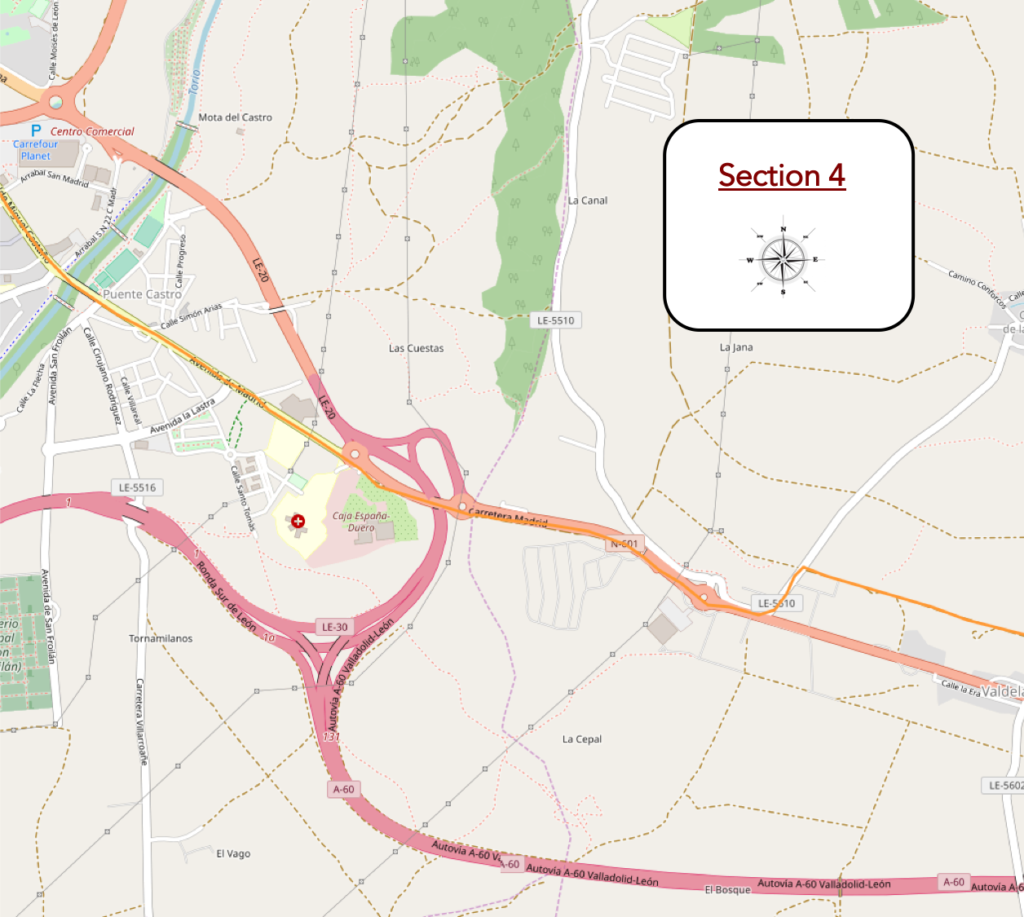

Section 4: In the suburbs of Léon.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, with however a little more downhill slope, but slight.

| The organizers of the Santiago track do not like to see the pilgrims wandering on the main axes, so as soon as a solution arises, they make a way out, here a pathway behind the fences, along the national road, before finding a large blue footbridge. It’s like being in a luna-park, in front of the roller coaster. |

|

|

| Then, it’s a real gymkhana on the footbridge to cross the roads. There are so many roads that pass through here. |

|

|

| On your way down, you’ll see the spiers of the cathedral in the distance. The pilgrim pathway plays a bit with the ramps of the motorway and the national road, to arrive at the bottom of the descent in the outskirts of the city. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the road junction, the Camino enters the city and descends Madrid Avenue towards the parish of Puente Castro. |

|

|

The storks, apparently very religious, have taken up residence here. Storks are numerous in the region.

| Further ahead, the Camino crosses the Rio Torio, one of the two rivers that bathe the city with the Rio Bernesga. Here there is a pilgrim information post, which is very useful for finding the direction and the necessary information. The pilgrim is now no further from the city center. But not quite! |

|

|

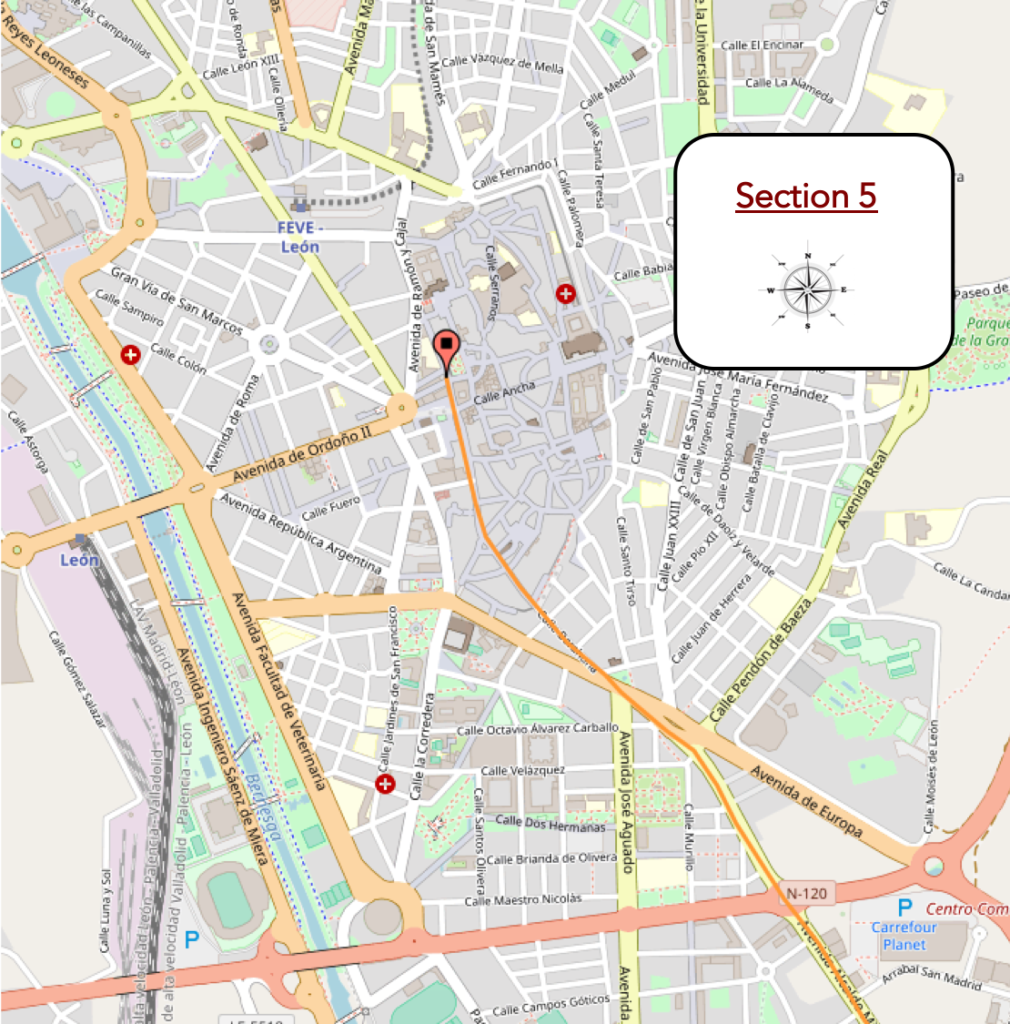

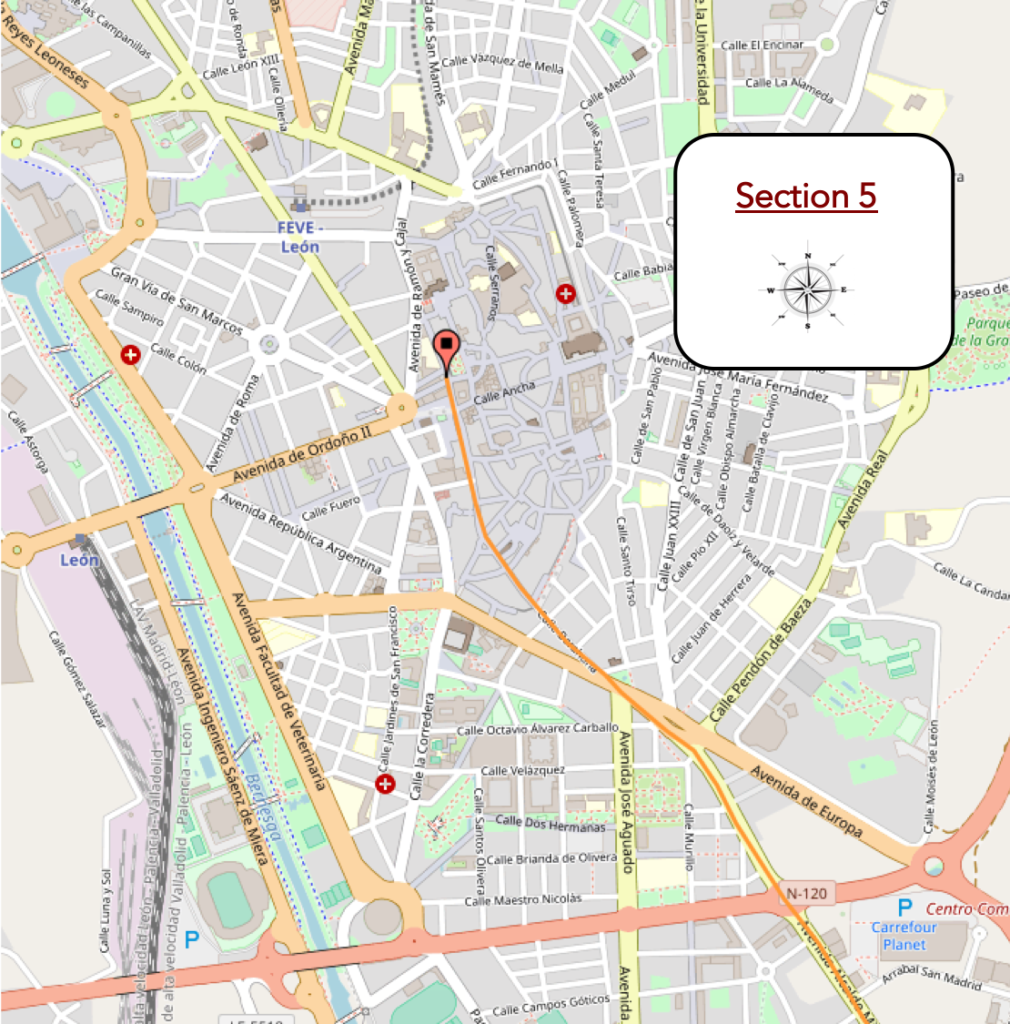

Section 5: Léon is also a magnificent city.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| León is a large city in the north, with its 130,000 inhabitants, almost as populous as Burgos, with its 175,000 inhabitants. Its name comes from the word “legio”, because the Romans came here, as they have been everywhere in Europe. The city was for a long time under the influence of Christians and Muslims, passing in the IXth century under the yoke of Asturia, of Oviedo, that erected here a fortress on the Roman fortifications. Then came the rise of the Camino de Santiago, and during the Middle Ages it was a period of posterity, which lasted until the city’s economic and demographic decline around the XVIth century. Today, the boom is again permanent in the city, in a city where tourists and pilgrims flock.

The Camino first crosses a part of the new city, with austere buildings that can be found everywhere, in most major cities. There is no risk of getting lost. The route is marked here with large yellow arrows. And then, there is only to follow the pilgrims in front of you, who them, will undoubtedly look at the signs, unless they seek to find accommodation. |

|

|

|

|

| The Camino runs through small tree-lined squares with fountains. On the pedestrian crossings, you sometimes notice that the pedestrians who cross are often pilgrims. |

|

|

|

|

Here too, in the parish of Santa Anna, the storks have taken up residence.

Further on, the route joins the medieval city wall, and then arrives in the historic part of the old town. The walls date back to Roman military fortifications. What can be seen today is a new wall built at the end of the 3rd century. It actually consisted of two walls: a lower exterior called rampart 4 m high and almost 2 m thick, and an interior 6 to 10 m high and 3 to 5 m thick, with a crenellated parapet. Between them was a space of almost 4 m for walking and fighting. Among the 9 gates of the city wall was the Puerta Moneda (Money Gate). It was the gate through which pilgrims and all who came from the east and south entered the old city. It was the shopping district (moneda: coin, currency), also of the Jewish quarter. Much of this wall was destroyed in the XIXth century, at a time of industrial modernization when urban sprawl was more important to citizens and city leaders than the preservation of the old walls.

| Further on, the Camino enters the old town. |

|

|

| Right next to it is the parish of St Marcelo. The foundation of the church dates back to the XIth century, having been built at the same time as a hospital intended to help pilgrims. With a Latin cross, its current design dates from the XVIIth century, its Gothic tympanum having been preserved. The Roman centurion Marcelo, martyr in Tangier, is the patron saint of the city. Its remains were brought to León in the XVth century. It is said to house beautiful altarpieces, no doubt, but to see them, the church would still have to be open. |

|

|

| Near the center, the narrow streets of the old town are charming, crowded with people, except at siesta time. |

|

|

| Through the small alleys, the route gets to the large squares of the city center. |

|

|

|

|

| On the Plaza Obispo Marcelo, stands the palace of Casa de los Botines, a building, rather austere in appearance. La Casa de Botines is sometimes translated as “house of high shoes”. This is a mistake, the name of the building is actually derived from the surname of Joan Homs i Botinàs, a Catalan entrepreneur who had settled in León and founded a textile company there located in the Plaza Mayor. It was this family that bought the land in Plaza San Marcelo, next to the Palacio de los Guzmanes, and commissioned Antoni Gaudi to build a new house there for the company. Gaudi’s controversial neo-Gothic edifice is one of the first monumental buildings to be built with private funds. Until now, constructions of this magnitude were financed by religious institutions or the aristocracy. The building was constructed towards the end of the XIXth century, overlapping Gaudi’s work on the Episcopal Palace of Astorga, built in a similar style. For his new project, Gaudi moved to León, where there were skilled workers and stonemasons who had worked on the restoration of the cathedral. The exterior appearance is reminiscent of one of the luxurious castles of the Loire Valley in France. Gaudi followed the design of a medieval palace with towers, a Gothic facade. Originally, the basement served as a central warehouse for the textile company, and the ground floor was occupied by its offices. The building today is owned by the Caja España savings bank. |

|

|

| Next door is the XVIth-century Palacio de los Guzmanes, a Renaissance palace whose main facade faces Plaza Marcelo near Casa de Botines at the western end of Calle Ancha. The Guzman family was one of the oldest noble lines in León. The palace has four towers, one at each corner. In 1881 it was purchased by the Diputación Provincial de León (provincial parliament) and currently houses the offices of this council. |

|

|

| It is at the corner of the Guzman Palace that Calle Ancha starts, with its terraces, its shops, the busiest street in the city, which leads to the Cathedral. Calle Ancha (broad street) in the heart of the old town (Casca Antigua) was once the decumanus, i.e. the main street of the Roman camp of the Roman Legion. |

|

|

At the end of Calle Ancha stands the cathedral, dedicated to Santa Maria de la Regla, the city’s flagship building. It is colloquially nicknamed “Pulchra leonina” (Beautiful Lioness). It is a true Gothic masterpiece. At this site, formerly Roman, succeeded one another at the beginning of the Middle Ages of the Romanesque Benedictine churches. Then, everything was razed to build the new church, between the XIIIth and XIVth centuries. With its high and slender naves, it looks a lot like Notre-Dame in Paris. One might think that the church has not undergone any transformations over the centuries. This is not the case. At many times, it was necessary to reassemble the collapsed vaults, the stained-glass windows in particular badly damaged during the terrible earthquake in Lisbon in 1755. The church has been in its current state since the end of the XIXth century only.

| But where does this particular habit of being photographed in front of monuments come from? On the main facade, with its arches, its portals, the statues tell Saint Mary the White, the life of Christ, and the eternal Last Judgment, often major theme of all the eardrums of the churches. On the facade, the rose window is under construction, framed by the two Gothic towers. Now, when you go a few meters towards the side facade, there is not a tourist, not a photographer. The facade is intact and as beautiful as the main facade. All tourists in the world, and sometimes we are also part of this world, often have a partial vision, due to lack of time and interest, to consider in detail the intricacies of monuments. |

|

|

| You can walk around this authentic masterpiece several times. Everything here breathes the beautiful, the eternal, the majesty, the prayer. It is almost as majestic as the cathedral of Burgos, although the building is much less complex, more compact. |

|

|

|

|

Inside, the dimensions are 90 meters long, 29 meters wide and 30 meters high. The church has the shape of a Latin cross, with its transept, its naves, its ambulatory and its apses which house the chapels, some of which have become museums. But what makes this church a real gem is the richness and color of these stained-glass windows, which makes this building a temple of multicolored light. Stained glass windows, there are a hundred, some exceeding 10 meters in height. The oldest date back to the XIIth century, but most were restored until the XIXth century.

Unfortunately, the church is a bit dark. Everything was black in our photos. So we are borrowing some pictures from inside for you to enjoy this gem.( https://madillcamino2014.blogspot.com/2015/10/new-monday-september-08-2014-leon.html) |

|

|

|

|

| Very close to the cathedral, stands the Royal Basilica of Saint Isidoro, which dates back a long way in time. It is integrated into the Roman foundations and the medieval walls of the city, located on the site of an ancient Roman temple. In the Xth century, there was a monastery and a church here housing the bones of Saint Pelagius, a 13-year-old boy martyred for his Christian faith in the Muslim-controlled city of Cordoba. Around the year 1000, the city of León was razed by Moorish troops, and with it, the monastery of San Pelayo. At the beginning of the XIth century, King Alfonso V, after recovering the city, ordered the reconstruction of the monastery and a small church called Iglesia antiqua on the site of the old church dedicated to St. John the Baptist and restored the convent occupied by Benedictine nuns. Later, the basilica changed its name and was dedicated to St Isidore, Archbishop of Seville, the most famous theologian of the period preceding the Arab invasion, whose bones were repatriated here. The legend says that near León, the bishops who brought back the remains of Saint Isidore, got lost in marshy lands, without the horses being able to advance. Covering the eyes of the horses, they got out of these swamps without difficulty and headed for the recently rebuilt church of Saints John the Baptist and Pelayo. |

|

|

| A little later, the sovereigns also had a funerary chapel built in the Iglesia antigua to house the remains of the monarchs of León, who had been scattered throughout the kingdom in different churches. It was called the Pantheón Real a few centuries later. It houses the tombs of the first royalty of Castilla y León. At one time, 23 kings and queens were buried here, but some of their tombs were destroyed by Napoleon’s troops. Today eleven kings, numerous queens and numerous nobles rest under the polychrome vaults of the medieval royal pantheon. It is one of the first manifestations of Romanesque art in Castile, with its squat columns, crowned with sophisticated capitals, and magnificent 11th century murals.

The Puerta del Cordero (Gate of the Lamb) is famous for its XIIth century tympanum, using scenes from the Old Testament, but also historical episodes from the Reconquista.

In addition to the major reforms carried out in the Romanesque period, the architectural ensemble of San Isidoro underwent several modifications in the XVth and XVIth centuries in the Gothic and Renaissance styles. Only the south facade and the south apse are visible from the outside. The rest of the church is surrounded by other buildings, and the western part (except the tower) is hidden by the wall. The XIXth century was a sad moment in history for this building. It suffered the occupation of French troops with looting. The rooms and the chapels became barracks, barn and stable. When the troops withdrew, they burned the church. The monument was then slowly restored. In 1936 the complex became the housing of military troops during the Spanish Civil War. Today, Saint Isidore is still a collegiate church, where the office of the canons is celebrated every day. |

|

|

| Wikipedia, public domain |

indexed in the Spanish heritage register of Benes of Interés Ciultural

|

| Below the cathedral, you have crossed the Barrio Húmedo (Wet Quarter), its narrow streets where the heart of the city beats, where people drink, eat and celebrate… |

|

|

| …you’ll get to the Plaza Major, which all the cities of Spain display with pride. This one is no exception. It is vast and magnificent, under its arcades. |

|

|

| Tight for time, we did not have the time to visit the San Marcos convent, on the outskirts of the city. We will come back to this in the next step. But for now, after having eaten a few tapas in the old town, another little tour to taste the pleasure of once again admiring this illuminated jewel, at this hour free of all tourists. |

|

|

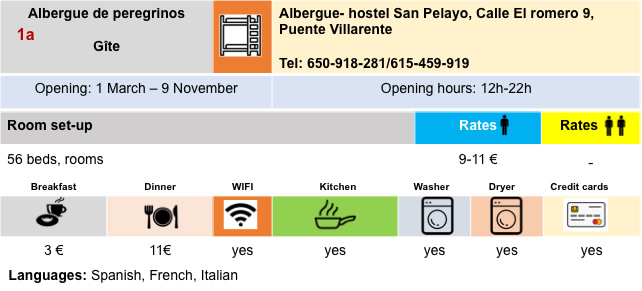

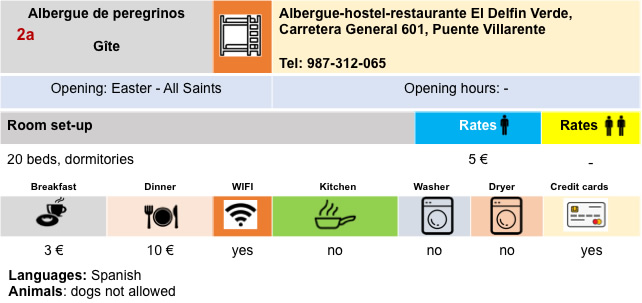

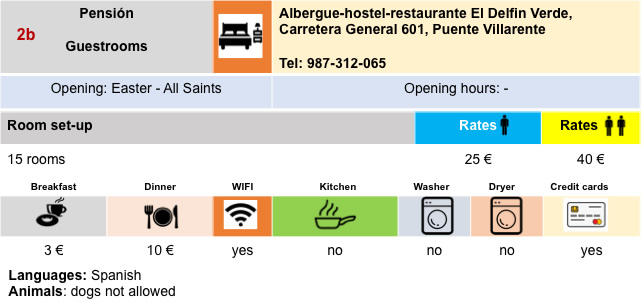

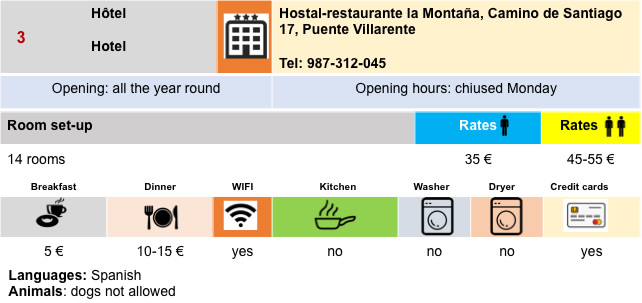

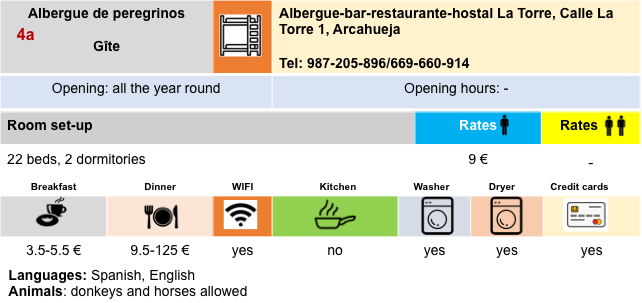

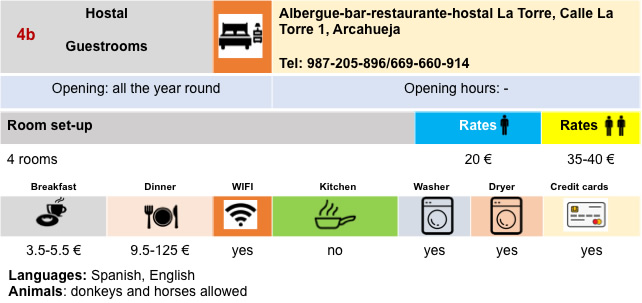

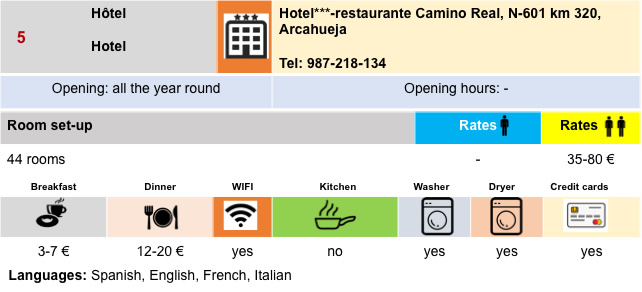

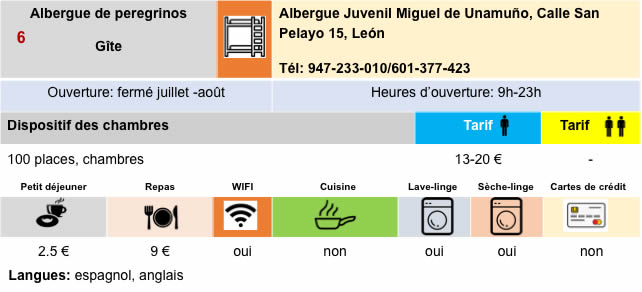

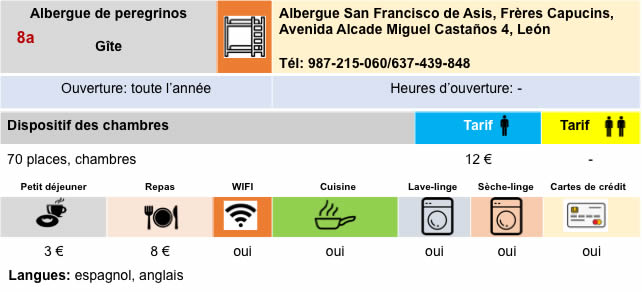

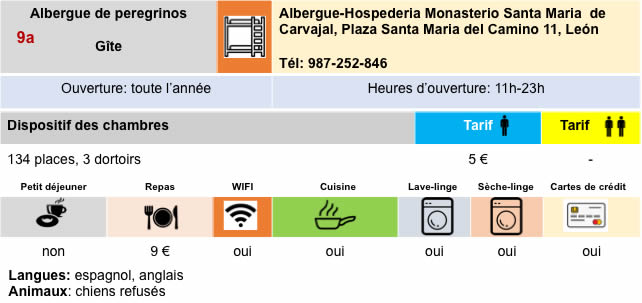

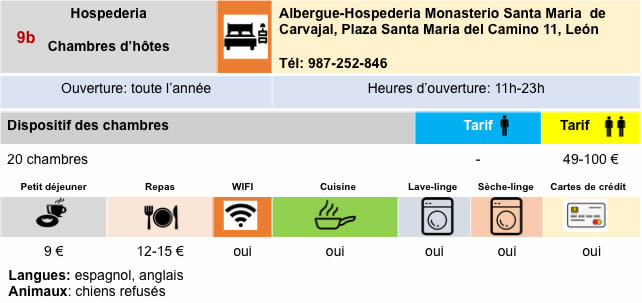

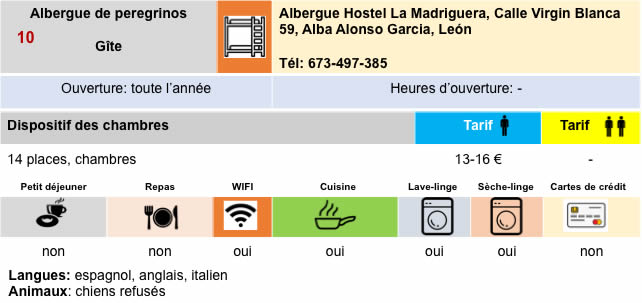

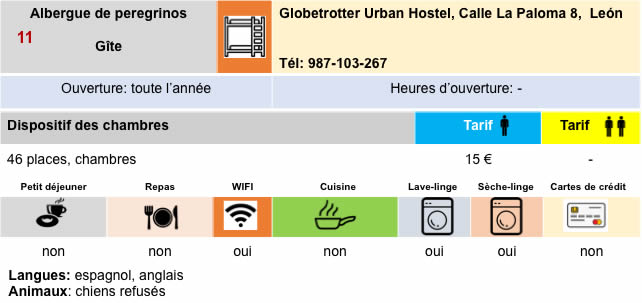

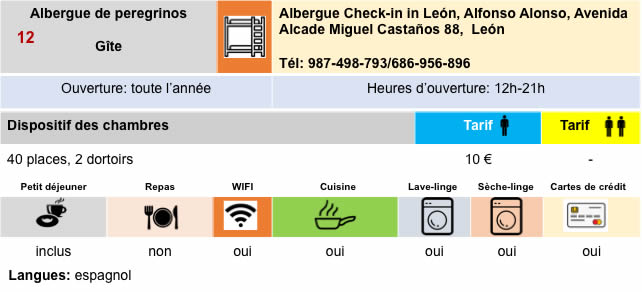

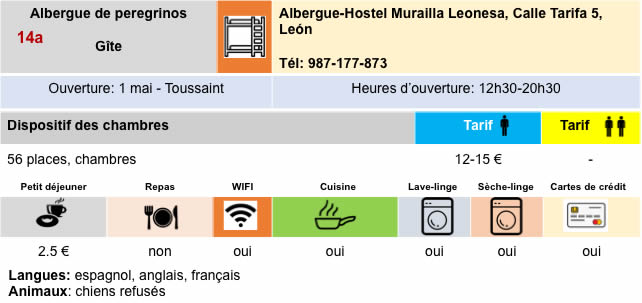

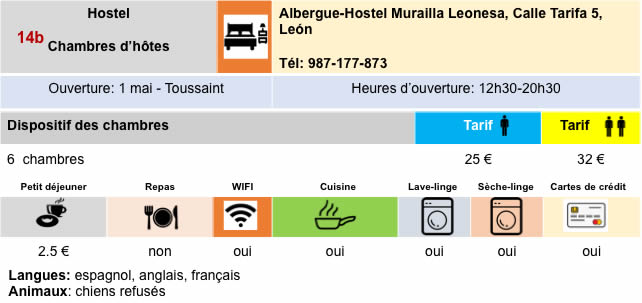

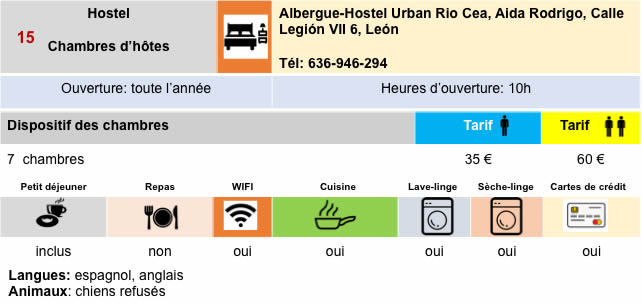

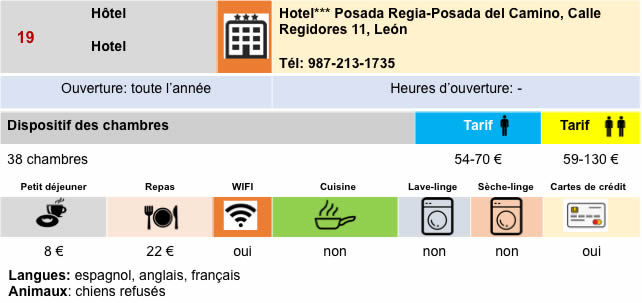

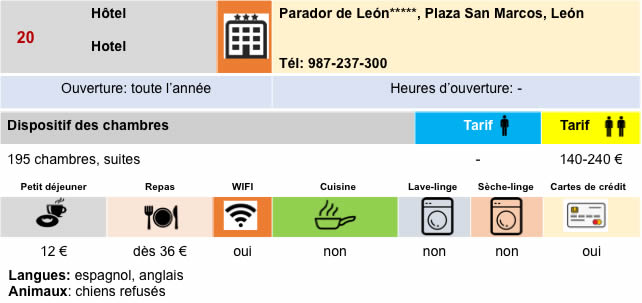

Lodging

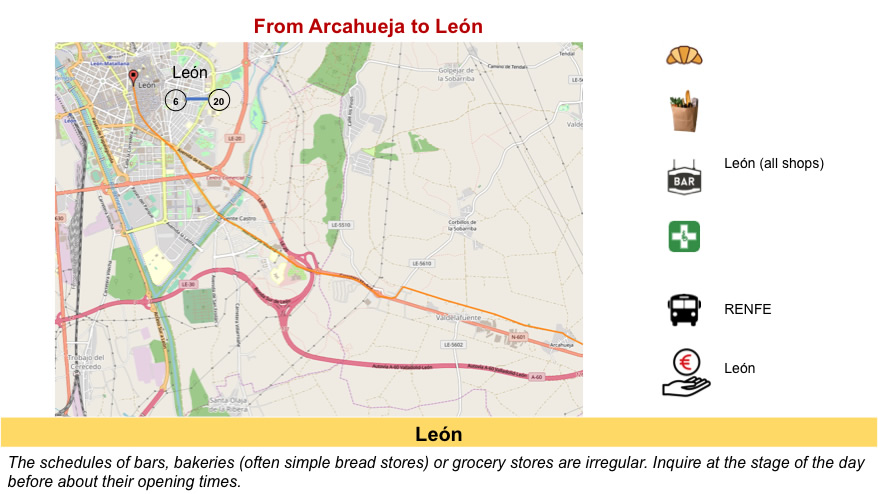

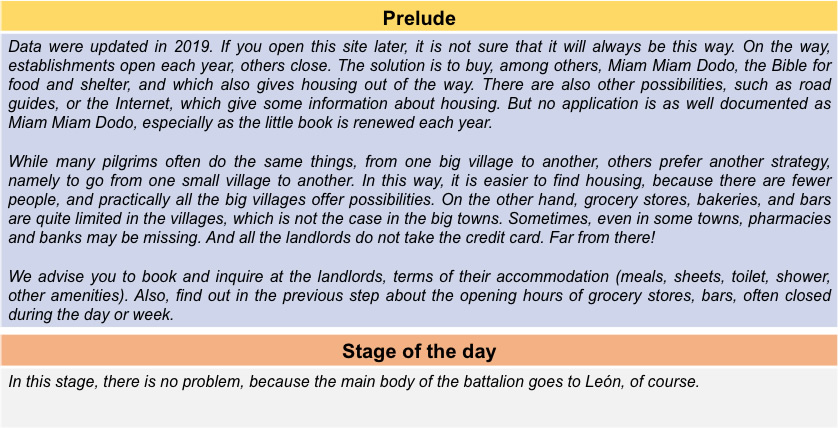

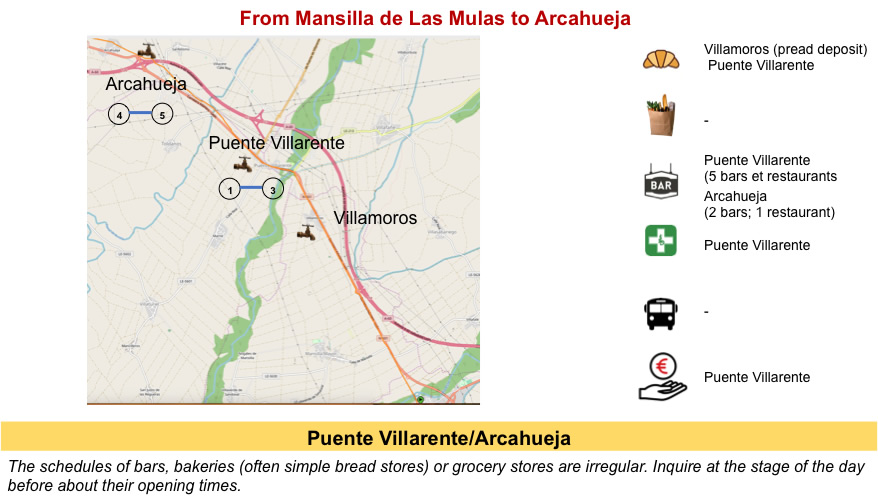

Today there are a few more trips on the paved road. You’ll be walking near a big city:

Today there are a few more trips on the paved road. You’ll be walking near a big city: