A different Meseta still continues here

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

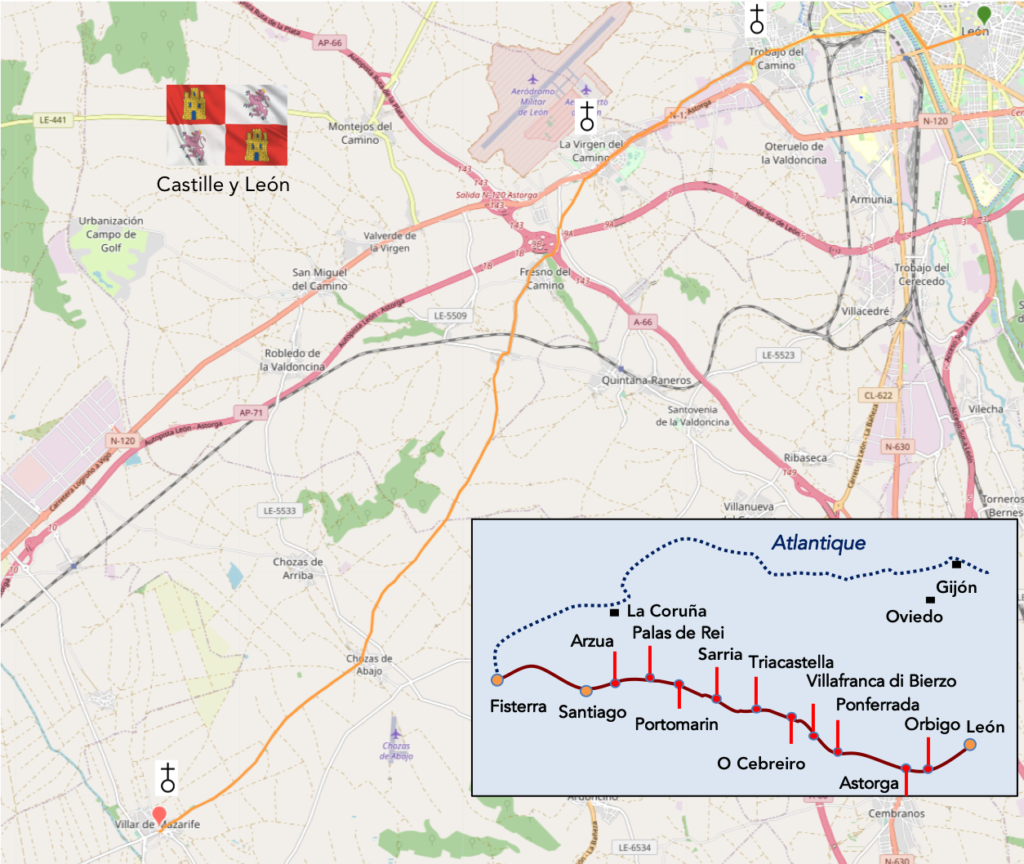

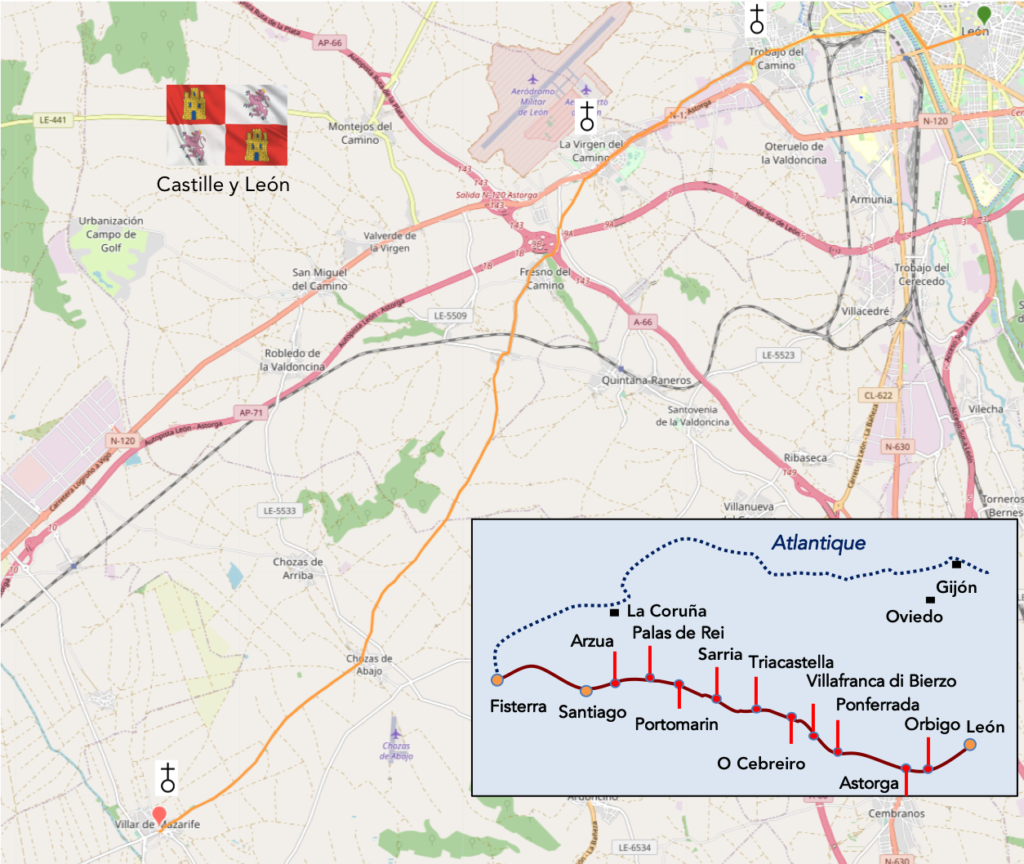

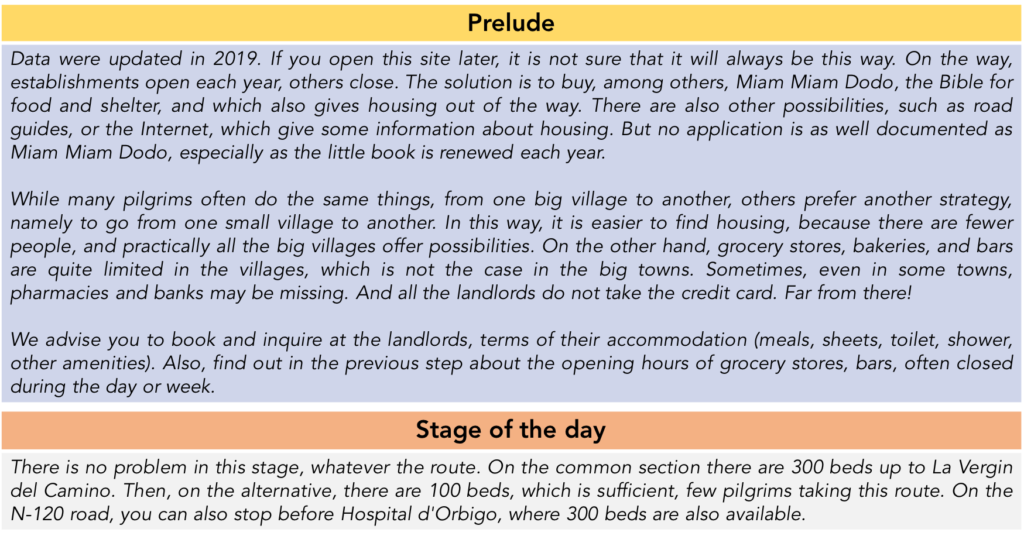

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-leon-a-villar-de-mazarife-par-le-camino-frances-123718911

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Nobody, apart from geographers, knows where the Meseta really begins and ends. Beyond León, the route heads towards the Montes de León, but does not reach the mountain that you guess is very far away. This mountain range, with snow in winter, touches the mountains of Cantabria, near the sea, and the Meseta. Today’s stage is again a marathon in the Spanish countryside.

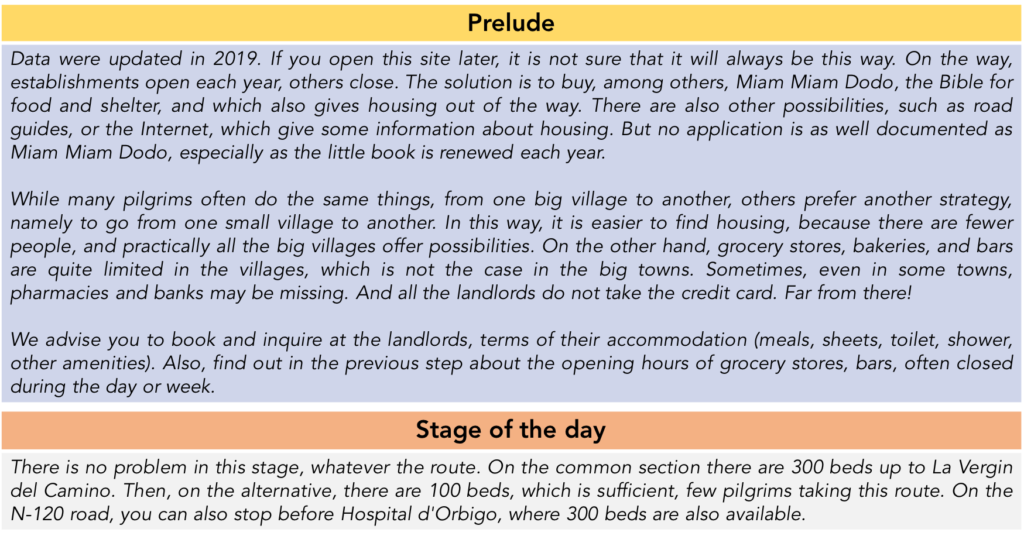

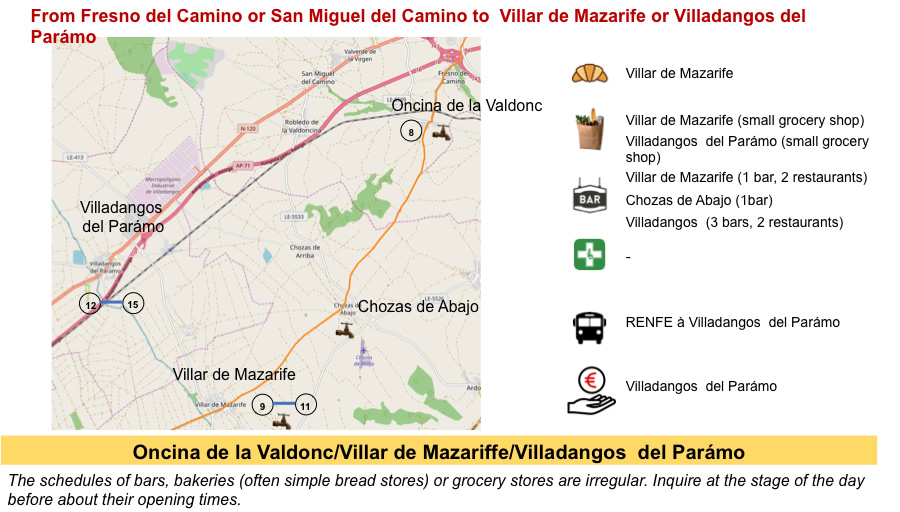

Here too, as in the long crossing of the Meseta, everything is a question of your division of the stages and the state of your legs or your joints. To go to Hospital de Órbigo, there are two possibilities. The first, which the vast majority of pilgrims use, is the direct route along the N-120 road. But, it’s deadly. The advantage is that it is only 27 kilometers long. The other possibility is to take the Calzada de Los Peregrinos. To reach Hospital de Órbigo, it is a little longer, 35 kilometers. But it is not the sea to drink, for many pilgrims, especially since the route is not very demanding. On this variant, the course is often monotonous, but it is far from the cars, which is not nothing. Here, you will avoid the horde of pilgrims, because the bulk of the battalion walks on the N-120 road. As 35 kilometers may seem long for many walkers, we split the stage in two, stopping in Villar de Mazarife halfway through.

To change the scene, we describe from León to Santiago the stages covered at the beginning of autumn. As the route passes through many forests, it is best, if you can, to pass here in autumn, with foliage on the trees.

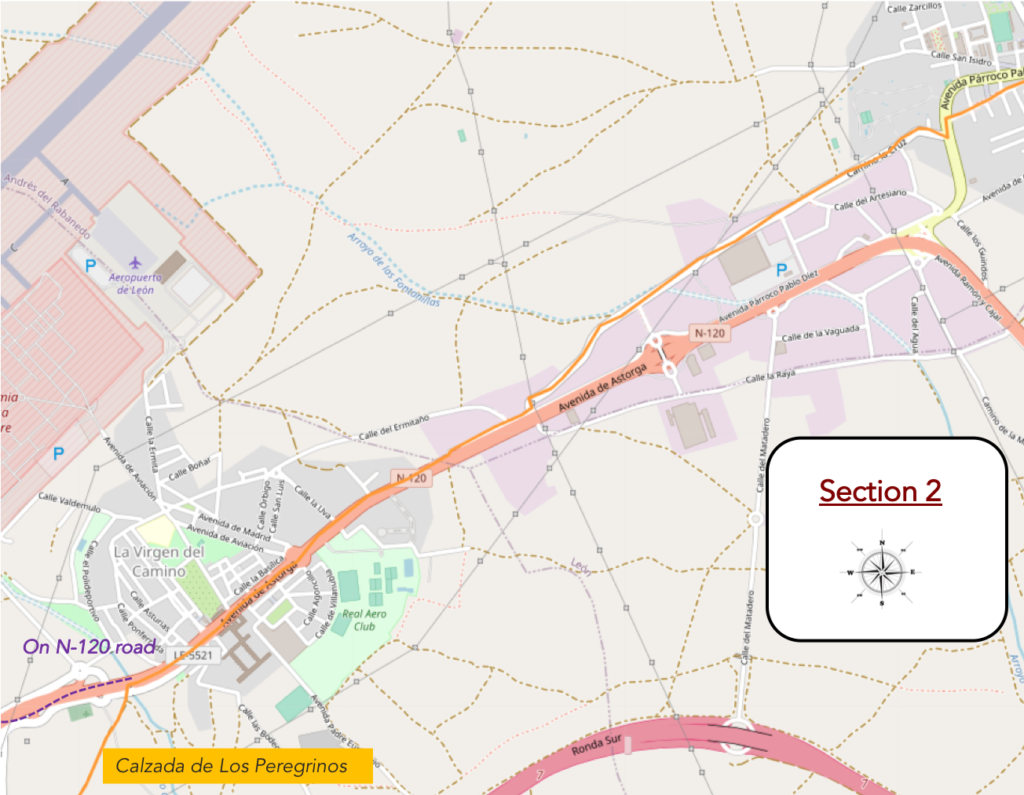

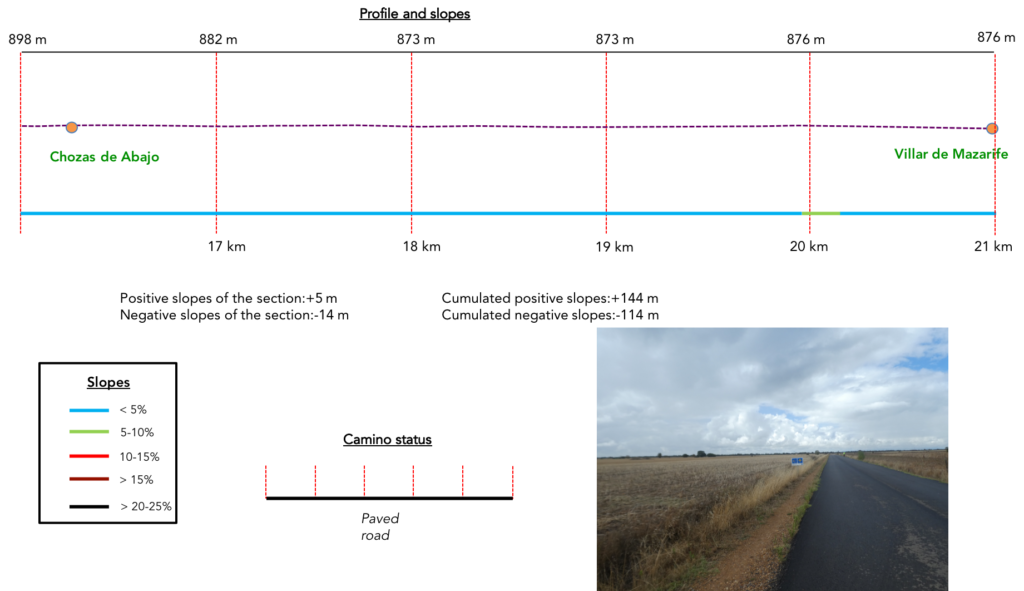

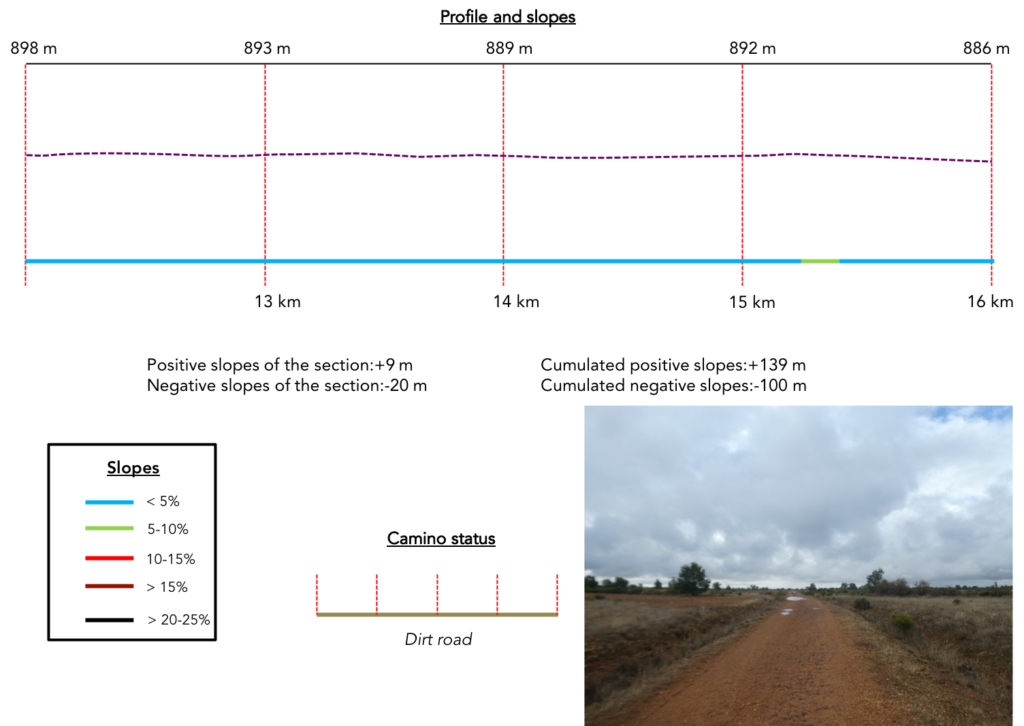

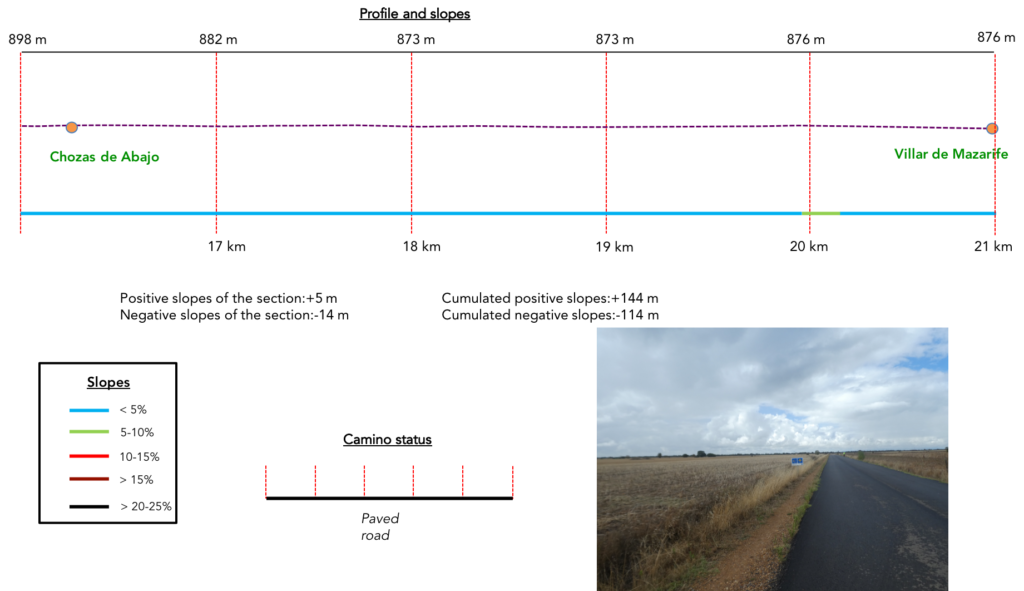

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (144 meters/-114 meters) are insignificant. In rare places on the course, the slope reaches 10%.

On the variant, even if you walk quite far from the main axis, there is a lot of road, first out of León, but also later in the countryside. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. But, here they are either real roads or pathways far from the roads:

- Paved roads: 14.4 km

- Dirt roads: 6.6 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

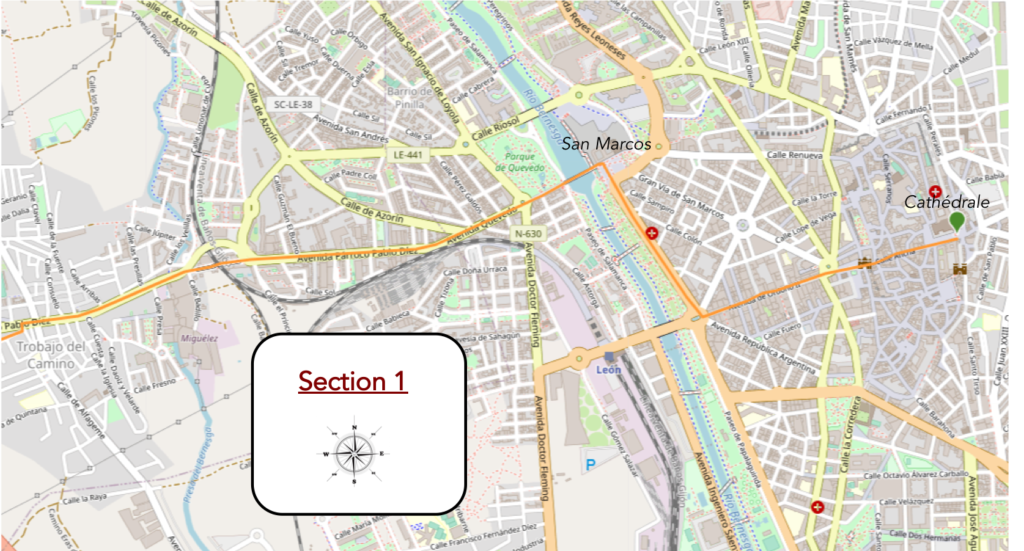

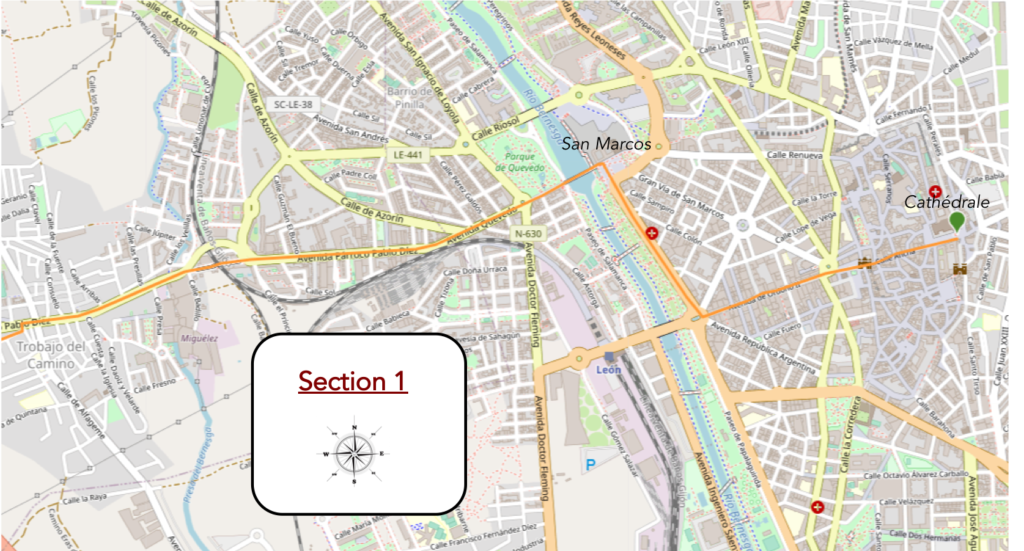

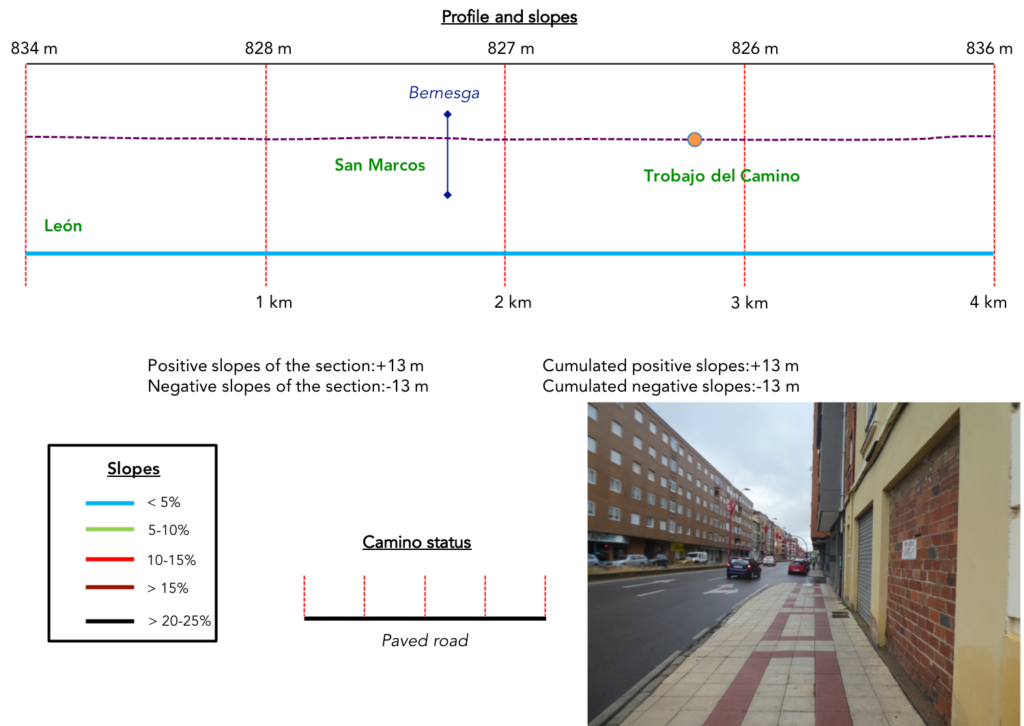

Section 1: A long journey through town to leave León.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| This morning, it’s raining lightly on Castile, but you have a feeling that it won’t last. In the traditional route, from the cathedral, it is difficult to find the right direction, because the route twists in the old town to pass by the church of San Isodoro, before reaching the convent of San Marcos. But, if you visited San Isodoro the day before, you can skip this tortuous route and take a more direct route. Just take Calle Ancha, which quickly leads to Plaza de Santo Domingo, near the building designed by Gaudi, continue straight along the long Avenue Ordoño II which leads to the monument dedicated to Guzmán el Bueno, very close to the Bernesga River. |

|

|

| There, you have to turn right and walk up the beautiful riverside promenade under the trees. |

|

|

| The route then arrives at the Monastery of San Marcos de León. This convent was preceded in the XIth century by a hospital for pilgrims and the poor, built under Ferdinand I of Castile. Then, in the XIIth century, the knights of the Santiago Order settled here. They were knight monks, protectors of pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. The sumptuous building of today was built under Ferdinand II of Aragon in full Renaissance, at the beginning of the reign of Charles V. During the Spanish Civil War, it was even a prison for Republican prisoners. Castile has always been very politically right wing, in the time of Franco. Here, there is a church and a cloister, and a museum which you may visit. But part of the building has now become a very expensive luxury ***** parador. |

|

|

| The facade displays a remarkable unity of Renaissance style over a hundred meters, despite a few late additions. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino runs through the Qevedo Park, crosses the beautiful Bernesga River on a paved bridge. |

|

|

| From here, it’s not the most pleasant route. The Camino will cross the suburbs of the city for a long time. It first runs through the Barrio de Pinilla. |

|

|

| Further on, at the entrance to the endless Trabajo del Camino, it progresses along the railway track, then deviates from it. |

|

|

| Here you cannot get lost. Shells are carved on the pavement and yellow arrows abound on the walls. |

|

|

| The temperature is quite cool, during this time of the year, 14 degrees. Until Santiago, we will never exceed 26 degrees this year. This is also a reason to promote these routes in the fall. |

|

|

| Throughout the suburb, the sidewalks are paved, under relatively austere buildings. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino crosses a bridge to pass over the railway line. |

|

|

| Après le pont, le Camino traverse le cœur proprement dit de Trabajo del Camino. Pour vous cela se résume en une grande rue qui monte en pente douce le long d’immeubles sans grand caractère. |

|

|

| Beyond the bridge, the Camino runs through the heart of Trabajo del Camino proper. For you, it boils down to a large street that slopes up gently along buildings without much character. There is a church or an oratory at the edge of the road. |

|

|

| Everywhere, the signs of the Camino de Santiago are flourishing. |

|

|

| But you still need to be careful. Here, the Camino leaves the axis of the main street to turn left. |

|

|

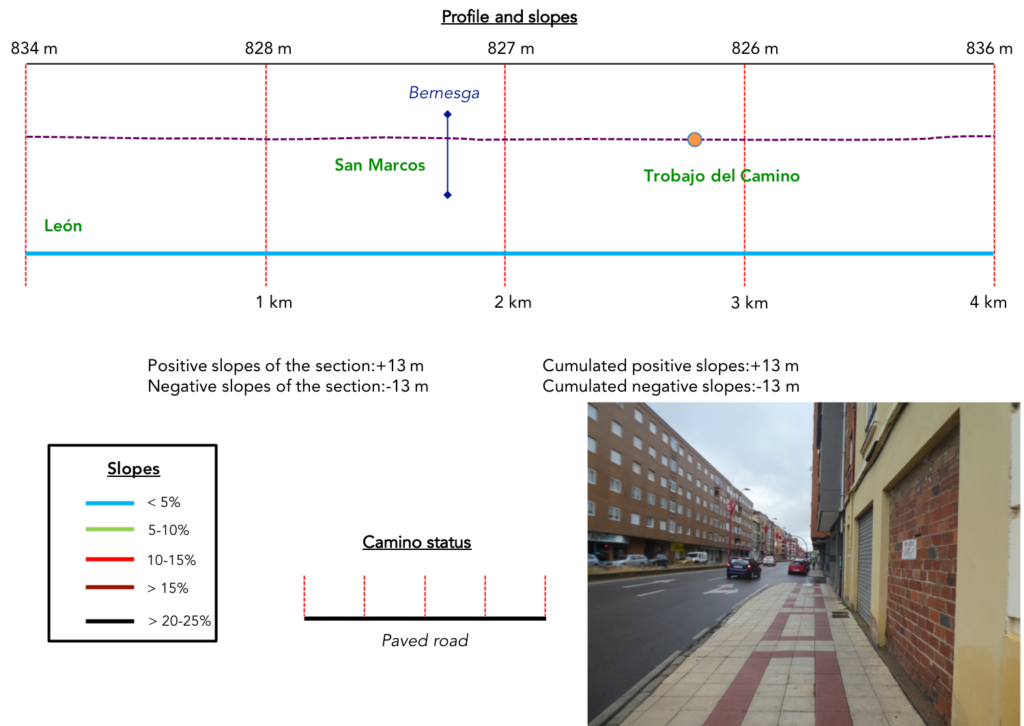

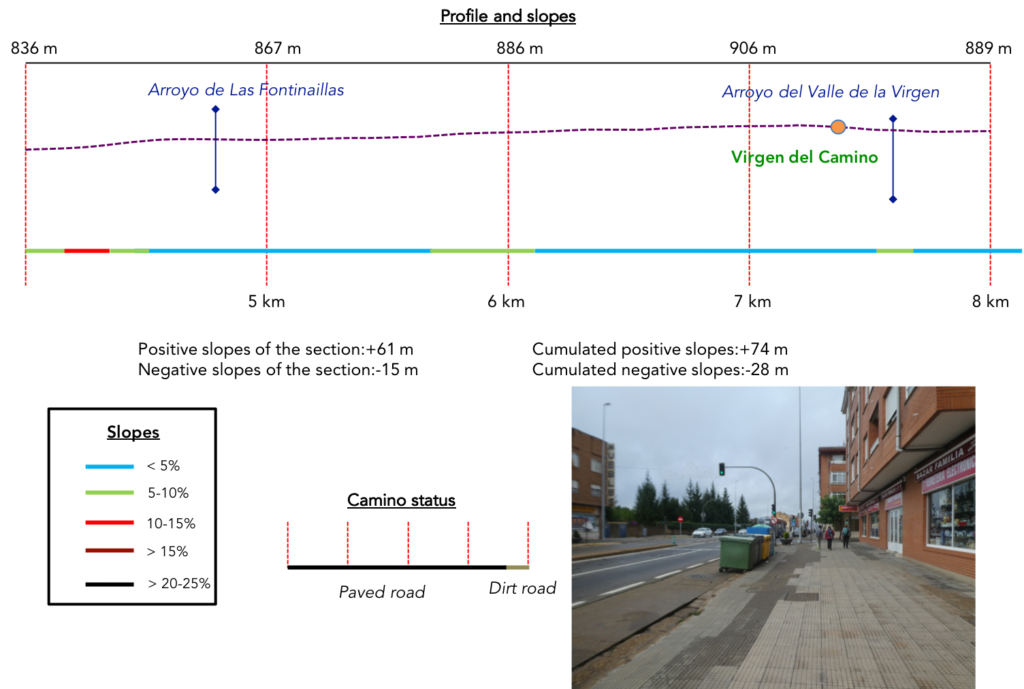

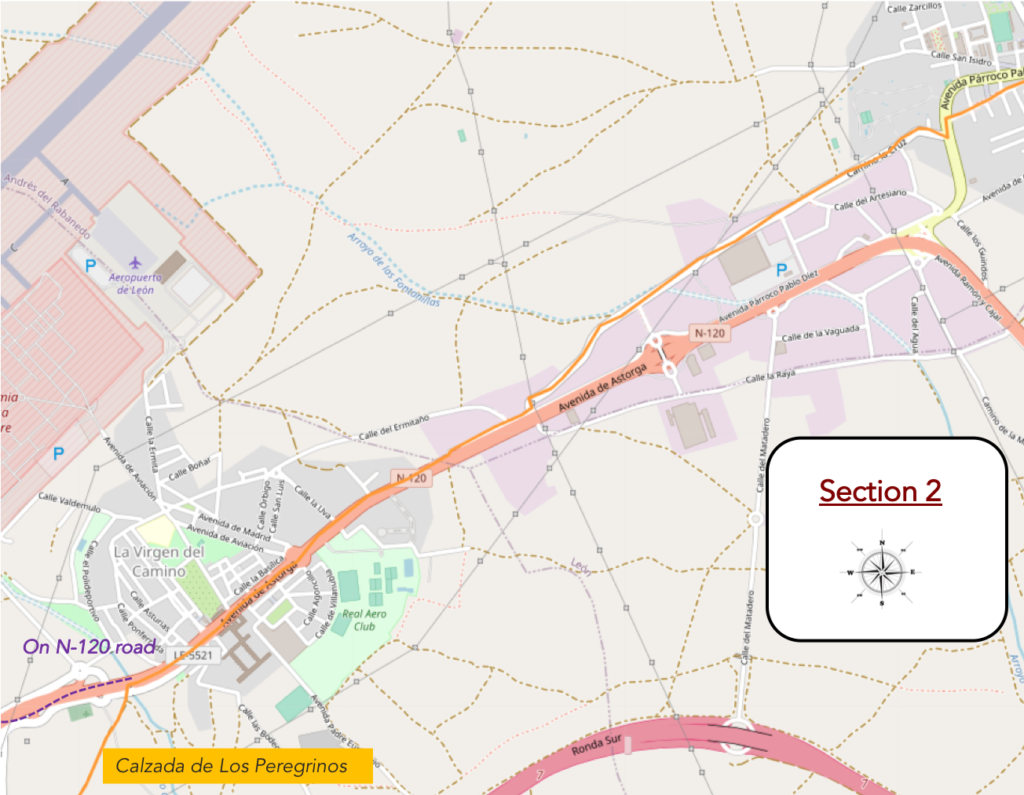

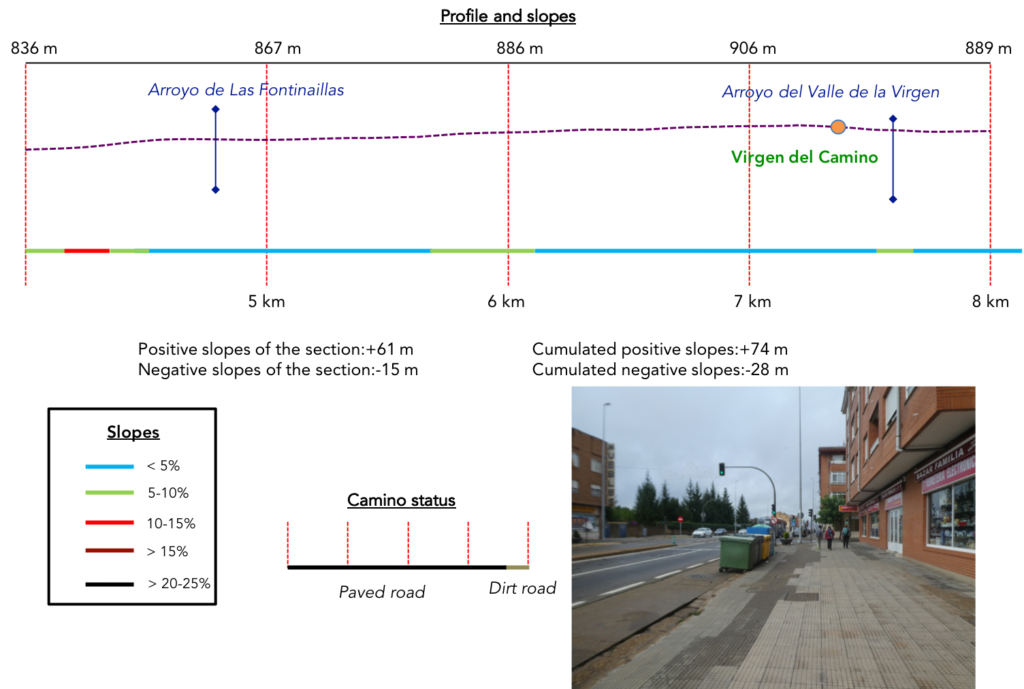

Section 2: The penitence still lasts to leave the suburbs of the city.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Crossing the city (22,000 inhabitants) will seem endless. And it is, for more than 3 kilometers. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino finally leaves a city that will be described as gloomy. |

|

|

| A road then climbs to visit troglodyte houses erected underground. It is difficult to say if people live in these curious residences. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road descends a little and runs along a semi-industrial zone for a long time, a little above the parallel N-120 road. |

|

|

| Here, the horizon is so clear that you could count the groups of pilgrims in front of you. It must be said that since Léon, the number of pilgrims has increased considerably on the route. If you stick to the official statistics of the Camino, for the month of September you should find 270 pilgrims a day beyond Léon. But, these statistics are biased, because they only consider pilgrims who have their “Credential” stamped. You can comfortably double that number. There are probably now more than 500 pilgrims walking here. |

|

|

| Further on, the road joins the N-120 road. |

|

|

| We will not say that the traffic is frantic on the axis. |

|

|

| According to the good tradition of the Camino de Santiago, motorists and pilgrims are always told when the route follows a national or departmental road. But, most of the time, like here, you won’t be walking on the road. |

|

|

What a pleasure to find your dear N-120 road again, right? It will be 310 kilometers that you follow it, from near or far.

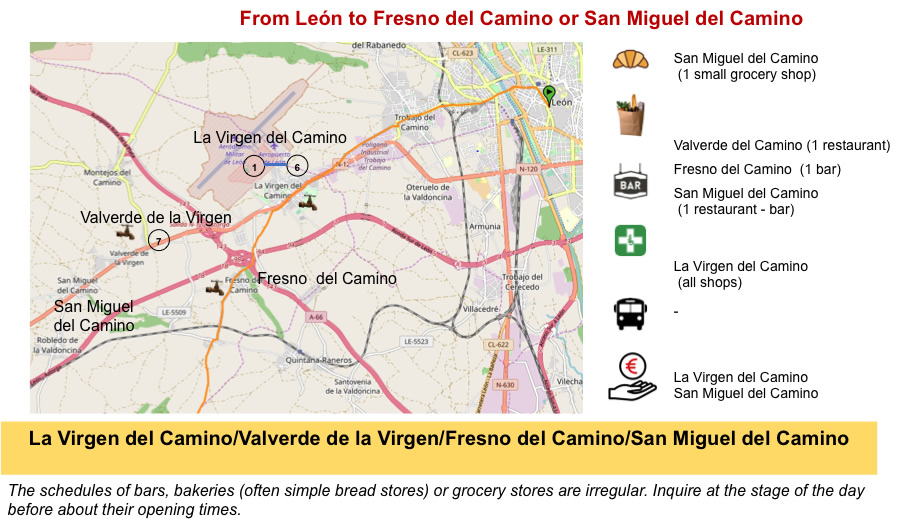

| he road then enters Virgen del Camino (5,000 inhabitants). The town is full of bars where pilgrims take their breakfast break. |

|

|

| It is the little sister of Trabajo del Camino, with quite large buildings very common along the national road. The colors are often quite bright and many buildings are made of exposed brick. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino gradually leaves the town… |

|

|

| …heading to a modern church. |

|

|

| At the exit of the town, the Camino leaves the N-120 road for a small road which descends under the national road. You walked nearly 8 kilometers to leave behind you the city and its suburbs. It is by far the longest route to leave a city on the Camino de Santiago. |

|

|

| It will soon be the moment of choice: the direct route to Hospital de Orbigo along the N-120 road or the Calzada de Los Peregrinos. |

|

|

If you have forgotten, in front of this baroque fountain, you are walking well on the Camino de Santiago.

| The choice is now at the top of the small paved road. The N-120 road is straight ahead. Good luck to those going there! The variant turns left. |

|

|

| We briefly mentioned in the introduction the reasons for following the variant. However, we will say that probably more than 80% of pilgrims continue straight on the N-120 road. In the minds of many of them, the goal is to get to Santiago as quickly as possible, for many reasons, either that they tire or that they can trumpet faster than the Camino de Santiago, they did..

oday, we’ll follow the Calzada de Los Peregrinos. It starts on a dirt road that nods in a kind of wild steppe. |

|

|

| Although you are still in the Meseta, here the landscapes are no longer the same. You have for the moment left behind the large cereal fields of the beginning and the corn of recent days. |

|

|

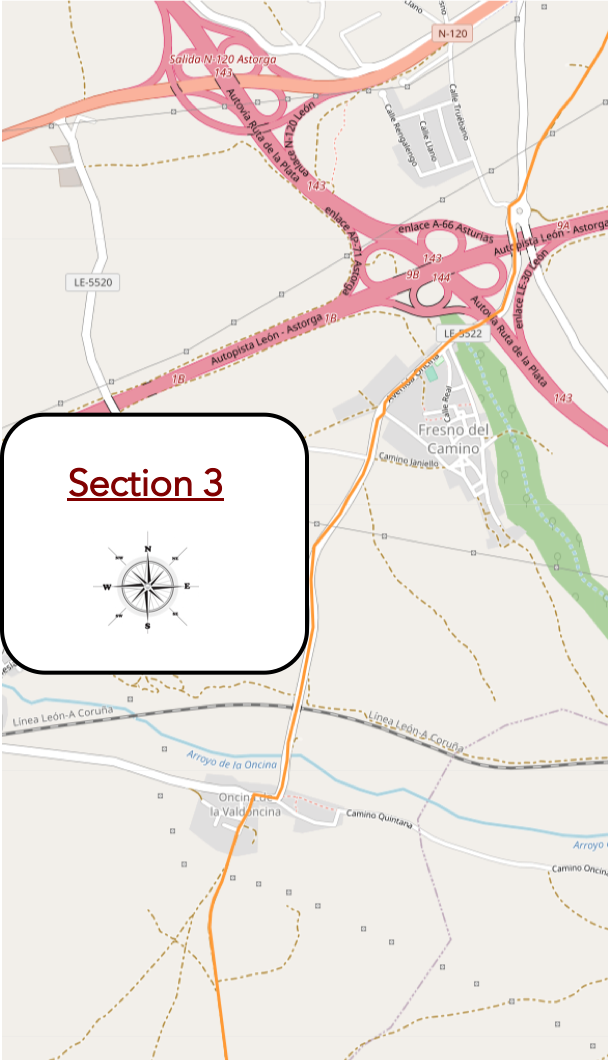

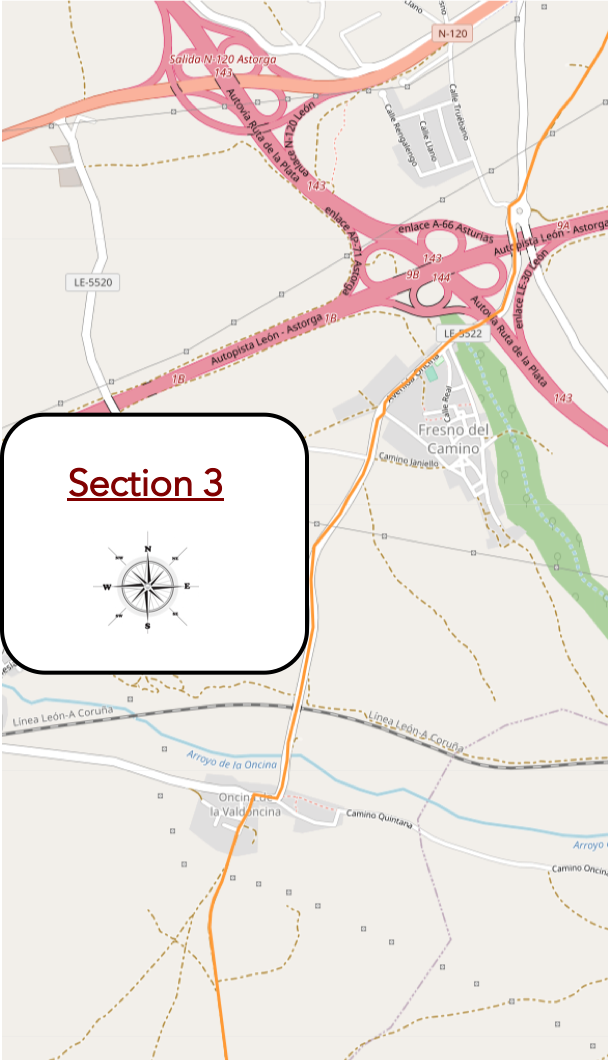

Section 3: Walk in the steppe.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

Looking back, you can clearly see that since La Vergin del Camino, you have changed countries.

| On the steppe, wild herbs crawl, as multiple as they are unidentifiable to an untrained eye. There are often small tufts scorched by the summer sun, for which it is difficult to associate a species, unless you are an experienced botanist. These plants oscillate between broom, laburnum and wild cypress, all plants that love arid lands. There are more than a hundred species for these bushes. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway crosses a small departmental road, the LE-5522 road, where, according to custom, the fact is signaled, to redouble your attention. But here, vehicles are rare as gold. |

|

|

| The departmental road then runs over the highway, which sleeps in the early morning, and also during the day. Here, two small regional highways intersect, in a very complex node. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road descends to pass lower under a ramp to the highway, under tall ash trees and oaks. |

|

|

| Soon after, the road gets in Fresno del Camino. |

|

|

| The road only skims the village. The paved sidewalks are welcoming, Is all this gleaming decor due to European funds? We cannot tell. |

|

|

| Water flows cool at the fountain, near a picnic spot. There are not many pilgrims here on this variant, maybe around fifty a day. |

|

|

| Further up, you leave the sidewalk for the raw tar. There is only a thin thread of gravel at the side of the road, and the slope is steep. The sky is low, but it will not rain today. This does not prevent some pilgrims from keeping their walking conditions in the rain. |

|

|

| The climb is not long, and the road descends gently from the mound. All around, it’s almost steppe with scattered bushes, always the same, and islands of greenery. |

|

|

| Further on, the road winds like an eel through the rough vegetation, undulating at will. |

|

|

| In the region grow rosehips, also known as wild roses or field roses. These shrubs produce rose hips, a term for the false fruit of the wild rose. With the red flesh that surrounds the fruits, people make syrups, herbal teas, alcohols or jams. The rosehips are like small red spots in the middle of the stunted holm oaks, which are lost in discreet bouquets on the slopes. |

|

|

| Further afield, the road runs over a small hill to cross the TGV line, which goes from La Coruña to León. |

|

|

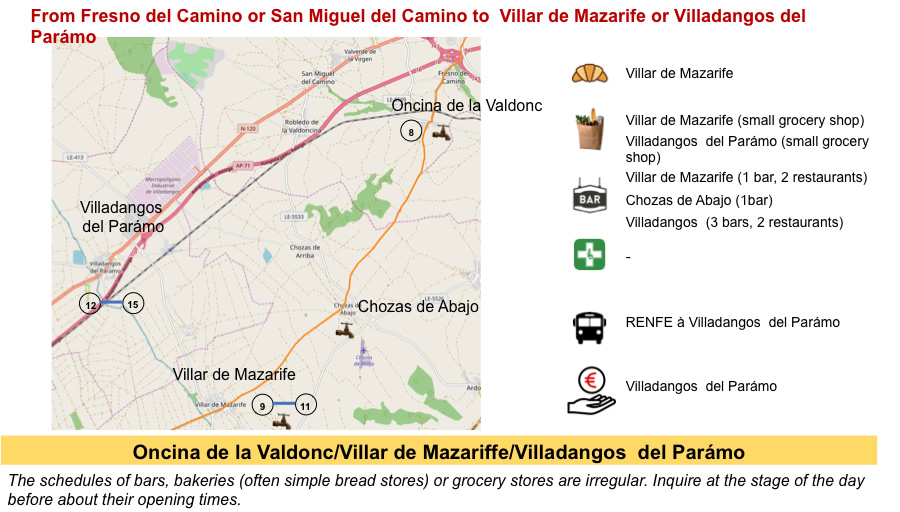

| Shortly after, before entering the village of Oncina de la Vadoncina, the road crosses the Oncina stream, a thin trickle of water in the wild grass. |

|

|

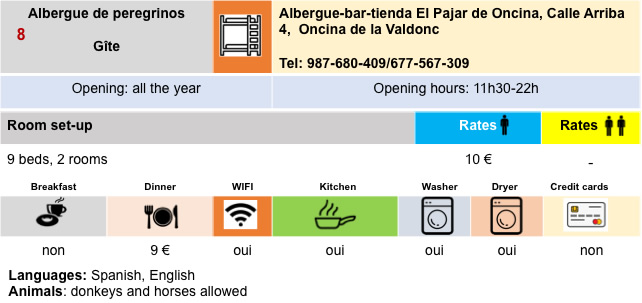

| In the village, you’ll find the bar, the inevitable “albergue”. But, as the route is little frequented, the pilgrims do not line up in front of the establishments. |

|

|

| In these relatively poor villages of Castile, adobe and exposed brick remain the favorite style of construction. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino will go crazy, climb a little more abruptly on a new hill and leave the tarmac. You then enter the Camino Real until Chozas de Abajo. |

|

|

| Rest assured, the climb is steep, but brief. |

|

|

| On the top, the Camino resumes its ease on the ocher dirt, in the steppe. Here, the pathway is so wide that you could pass several regiments in line. |

|

|

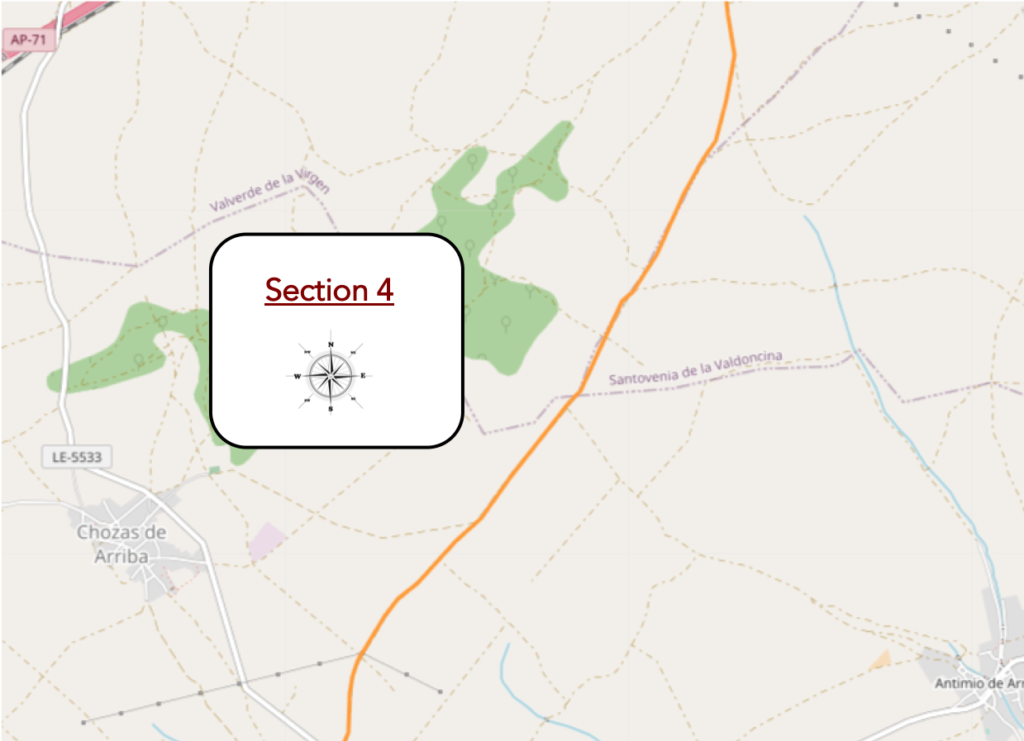

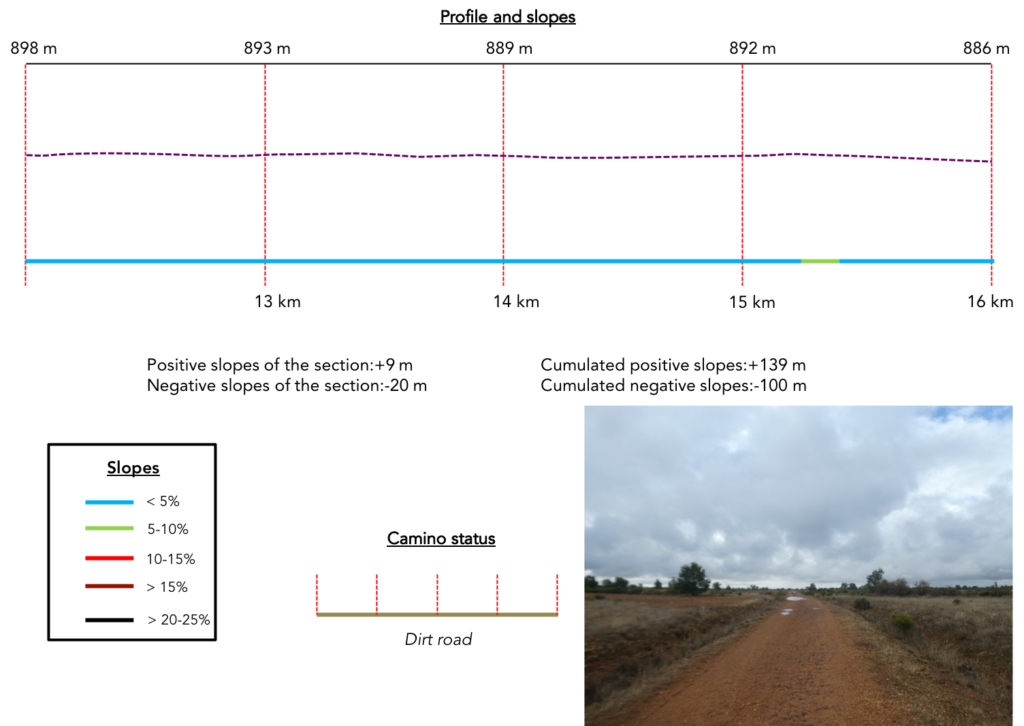

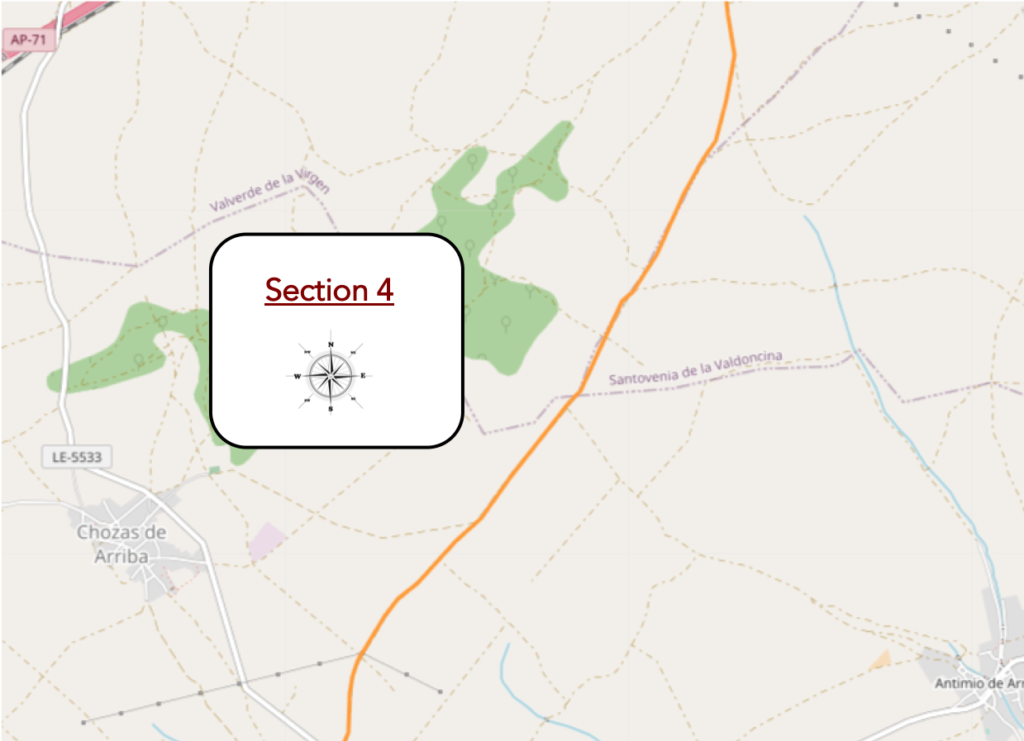

Section 4: At the end of the steppe.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Here, you leave for a great moment of solitude, a walk in the flat steppe. But, track organizers won’t let you down. Signs are present to tell you that you are not lost. |

|

|

But if you were to survive here, you could suck rose hips, one of the rare signs of life in this lost paradise, far from men.

| Many puddles dot the ungrateful land. It is easy to imagine that in heavy rain, you will stick here, that the thick mud will swallow your shoes. |

|

|

| Further, small black poplars have allowed themselves to grow in the middle of clumps of holm oaks, the encinas of the Spaniards. These rare trees on the French path are very present in Spain. |

|

|

| If you walk here in autumn, you can get the feeling that in this desolate desert only short grass grows, as if baked. But, you often find stubble, this stubble left by the harvesters. But, it is a safe bet that on this ungrateful land, it is not fields of beautiful wheat that proliferate. |

|

|

| You think you are alone. No way. This small point, which moves on the horizon, is a pilgrim who walks. |

|

|

| Like him, you will arrive at the top of the gentle mound and switch to the other side. |

|

|

| Further on, bad tar replaces dirt, but that hardly changes the situation. |

|

|

| Shortly after, here is again a pilgrimage milestone and a panel. You’ll soon cross the psychological barrier of 300 kilometers to reach Santiago. Will this news be indifferent to you or full of hope? The panel details the route, the hostels, the public buildings and even the state of the tracks.In fact, everything that we offer you. |

|

|

| Further on, the cultivated fields gradually take the place of the moor. But, it is no longer quite the Meseta. The peasants here have not murdered all the trees. |

|

|

| Sometimes the boxwood gleams on the embankments amid the scorched grasses and rough vegetation. |

|

|

| Sometimes the immensity makes you dizzy, as in the Meseta. |

|

|

| You approach a village little by little and the road rises a little again, as if to prove to you that the country is not as flat as a pancake. |

|

|

| But nothing changes or moves, except the oaks which have taken a little more height and which are no longer all stunted holm oaks. The varieties of real oaks, the Spanish robles, are more numerous in Spain than in France. Space is still just as big, majestic, immutable. |

|

|

| However, at the top of the last mound, which is not one, you can see Chozas de Abajo in front of you. |

|

|

Section 5: An asphalt road along the cornfields.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| The bad road passes in front of a troglodyte house whose chimneys can be seen emerging from the ground… |

|

|

| …and reach the village. Throughout this region, signs have been installed providing information on the Camino and on the villages, it passes through. |

|

|

| n many villages on the Camino de Compostela, it is often the bar that is offered first, as if the pilgrims were only waiting for that. |

|

|

| The villages follow each other and all look alike. Deserted streets where adobe, lime and brick mingle. We wouldn’t vacation here. But why would the locals consider such initiatives? These villages are only there to provide food and lodging. |

|

|

| Here, there is no church, which is rare in villages, but a curious bell tower welcomes you. |

|

|

| You leave the village directly by the road, behind the last adobe houses. From here you no longer walk on the Camino Real but on the Camino de Santiago. This does not change the landscape in any way, except that now it is the paved road. |

|

|

| As soon as you leave the village, the country road crosses the Arroyo del Monte, which looks more like a swamp than a real stream. |

|

|

| At first, the landscape mixes hints of steppe and harvested fields. |

|

|

| The day promises to be long enough on this endless plain, on this straight road where the horizon does not end. |

|

|

| So, you pay attention to unimportant details. You have to fill the void. For example, here new asphalt was deposited. |

|

|

| Further on, another detail that is important. You are walking on the Camino de Santiago but you know that. |

|

|

| Then, the message is repeated. Is it to apologize for running through such a prestigious track? |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road approaches the trees. Here, as mentioned in the introduction, it is possible to walk on dirt at the side of the road. There are the fans of dirt, the indifferent who alternate sometimes clay, sometimes asphalt. Still others who don’t care at all. |

|

|

| he wood is sparse, but there is a picnic spot under the tall oak trees. You have a feeling that there will never be a crowd here. |

|

|

| Further on, there are no more landmarks. There is only sky and ground, nothing vertical where the gaze can cling, and the road that flees in the distance, straight. |

|

|

| So, in these cases, you invent a benchmark, according to the rule of calibration, if practiced by hikers. As the pilgrims are rare, it is necessary to change the point of fixation. You spot a group of trees in the distance and then you lower your head, let your disparate thoughts run wild and only raise your head when you imagine having passed the aforesaid group of trees. It doesn’t work in all cases. |

|

|

| And the road keeps on going, always further. Here you can count the trees. On the dead crops, it is always difficult to say what the farmers have planted and harvested. No doubt cereals, to see the stubble that populate the endless fields. |

|

|

| Further on, behind the trees, you can see the village of Villar de Mazarife. |

|

|

| Shortly before the village, the eye rests on a charming piece of water where the poplars are mirrored with delight.e. |

|

|

| The road arrives at the village in the corn. |

|

|

| The village welcomes you with a fresco showing the church in the middle of the apostles. The church is further away, closed. |

|

|

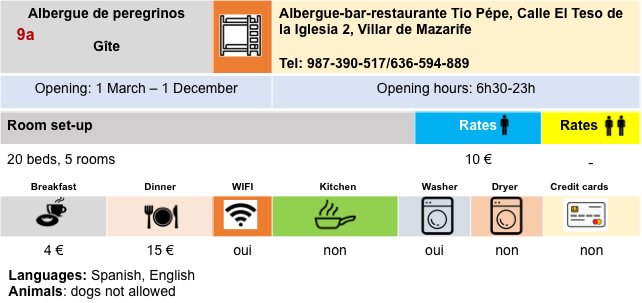

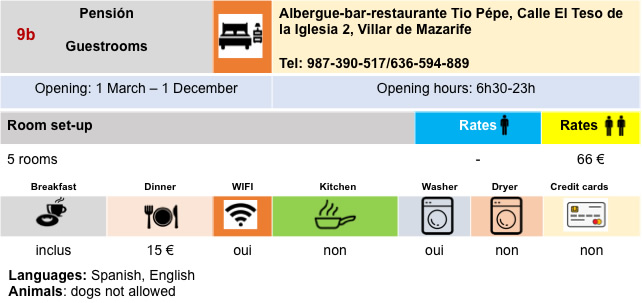

| The village here is quite large. The village is an ancient Roman place. Documents from the end of the Xth century testify to the presence here of an Arab family, the Mazarefs, which gave the name to the village. |

|

|

| In addition to inns and bars, the village offers grocery stores, an important resource for the pilgrim, when they are open. |

|

|

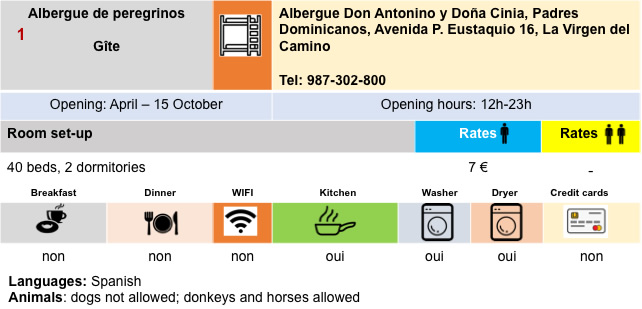

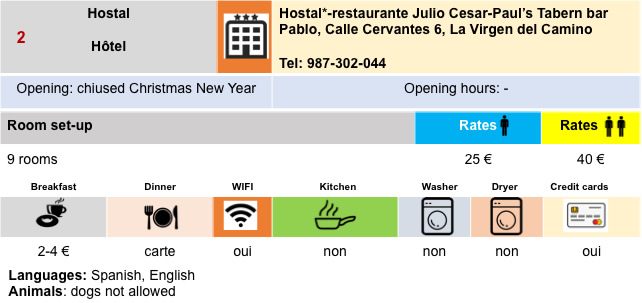

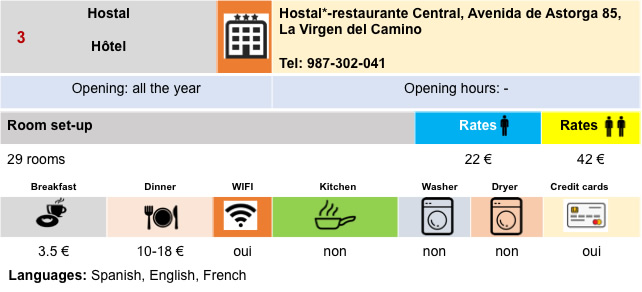

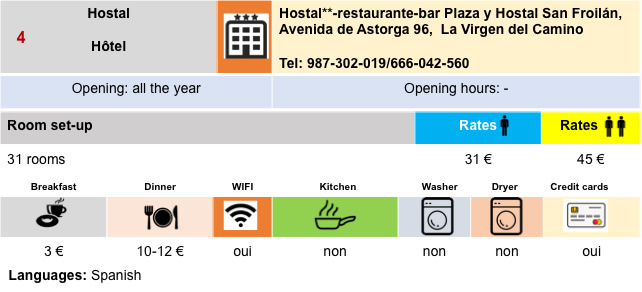

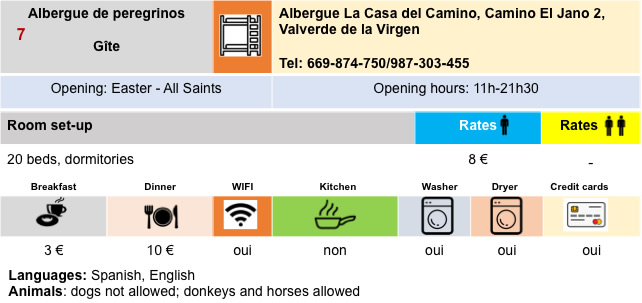

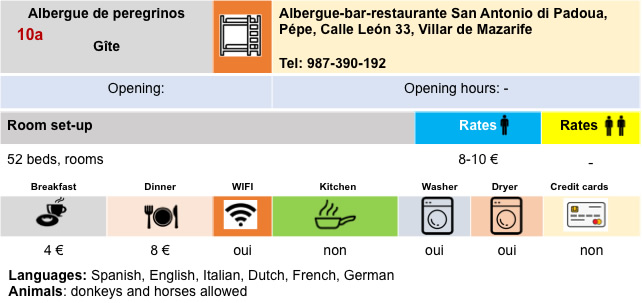

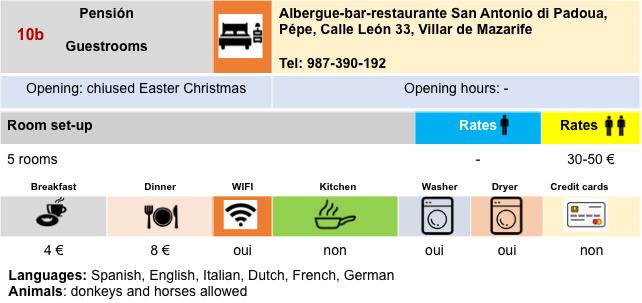

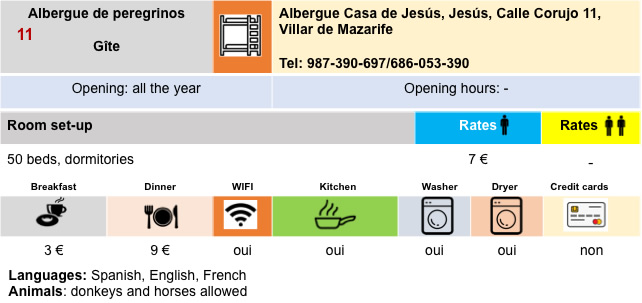

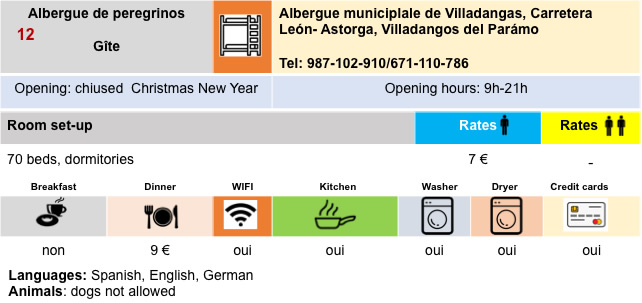

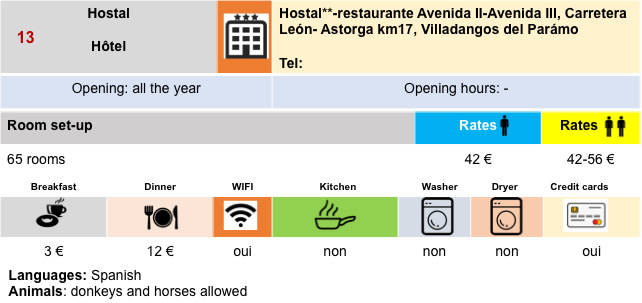

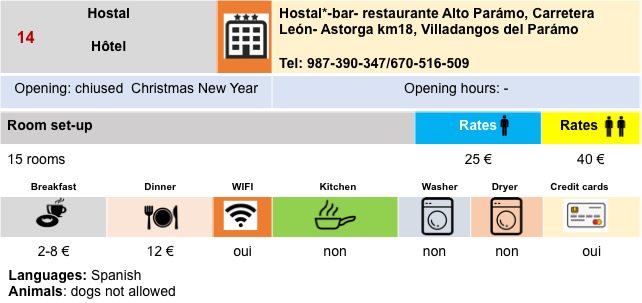

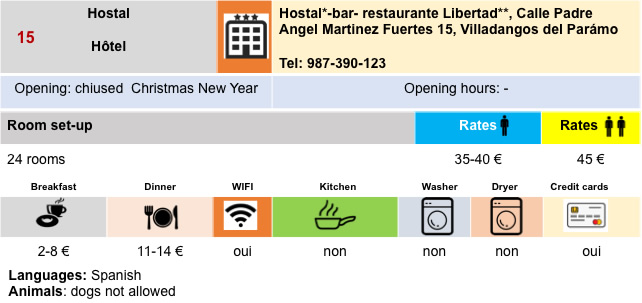

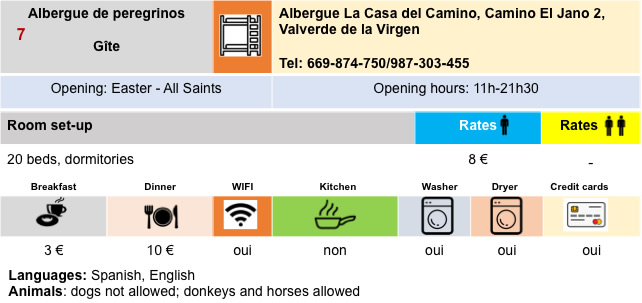

Housing

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 2: From Villar de Mazarife to Hospital de Órbigo |

|

|

Back to menu |