Aqueducts for corn on a straight line that runs away to the horizon

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

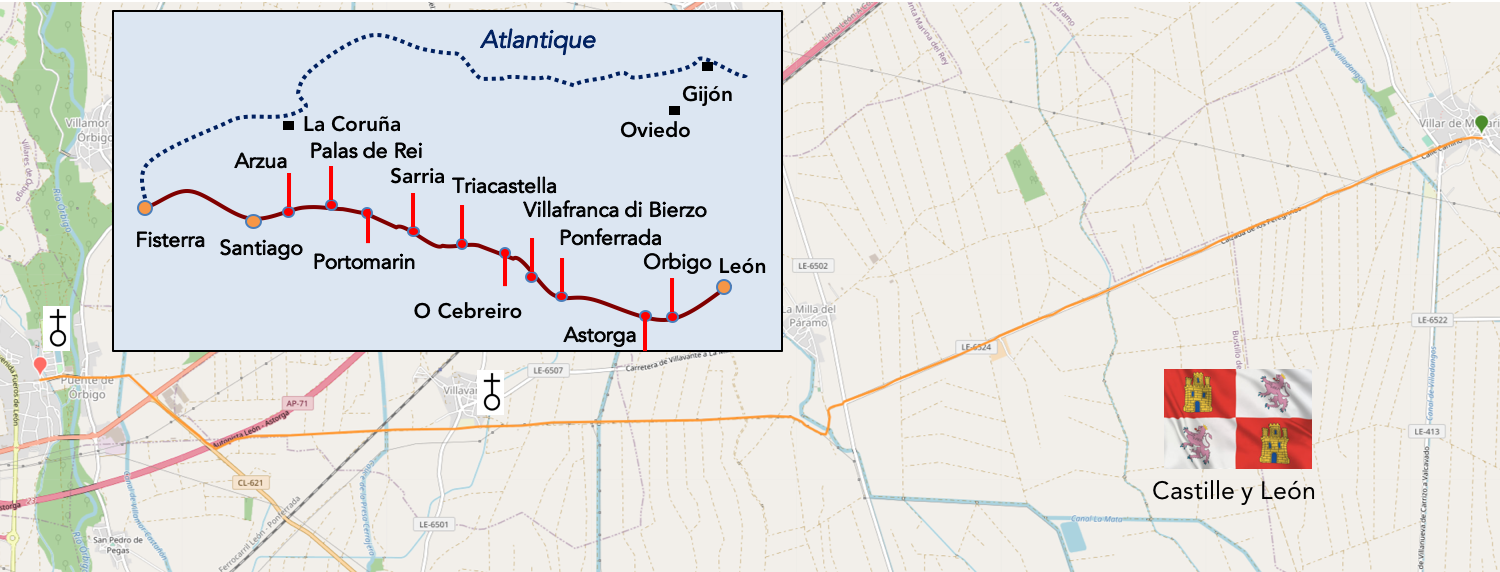

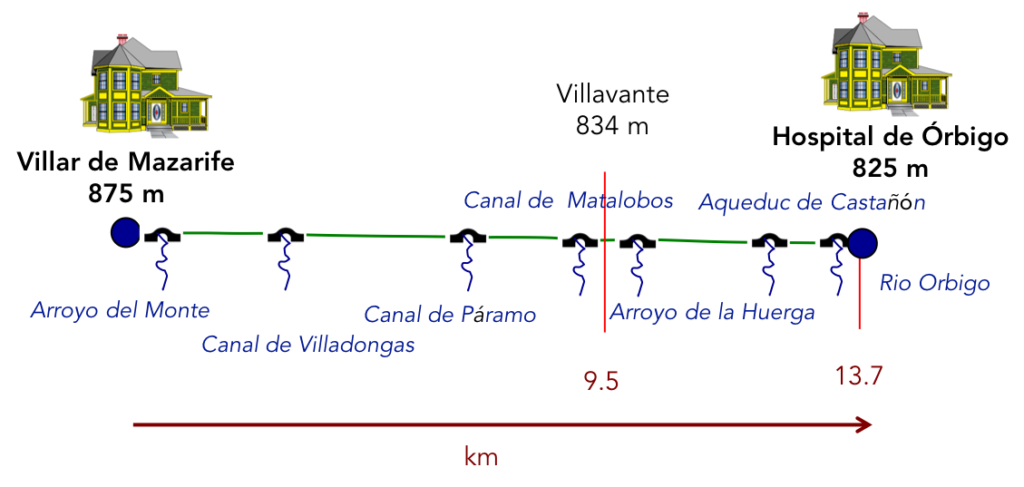

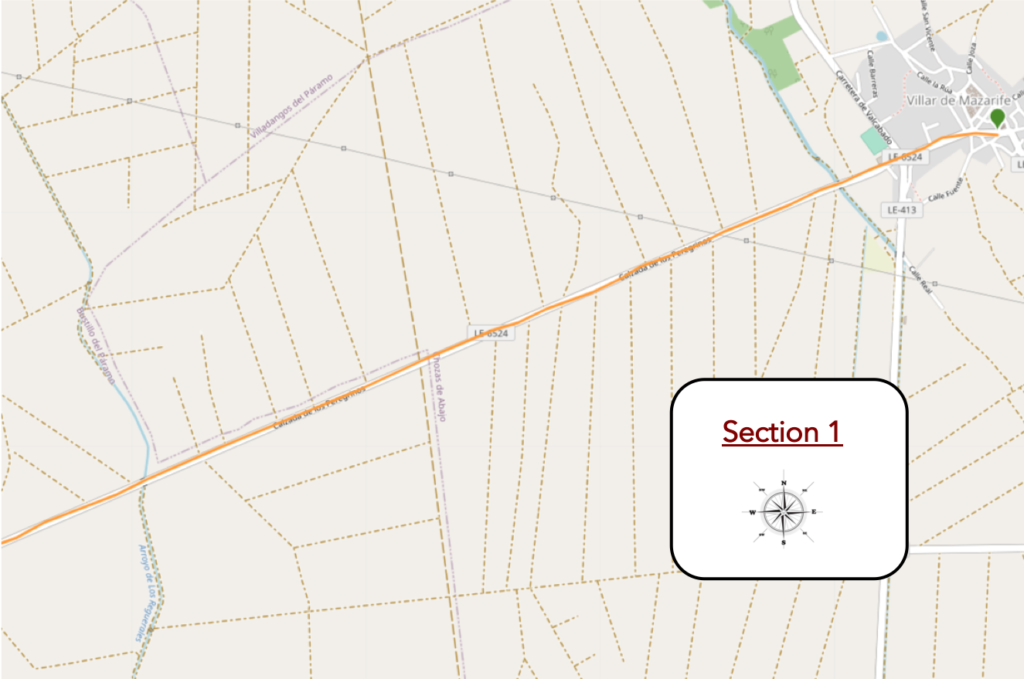

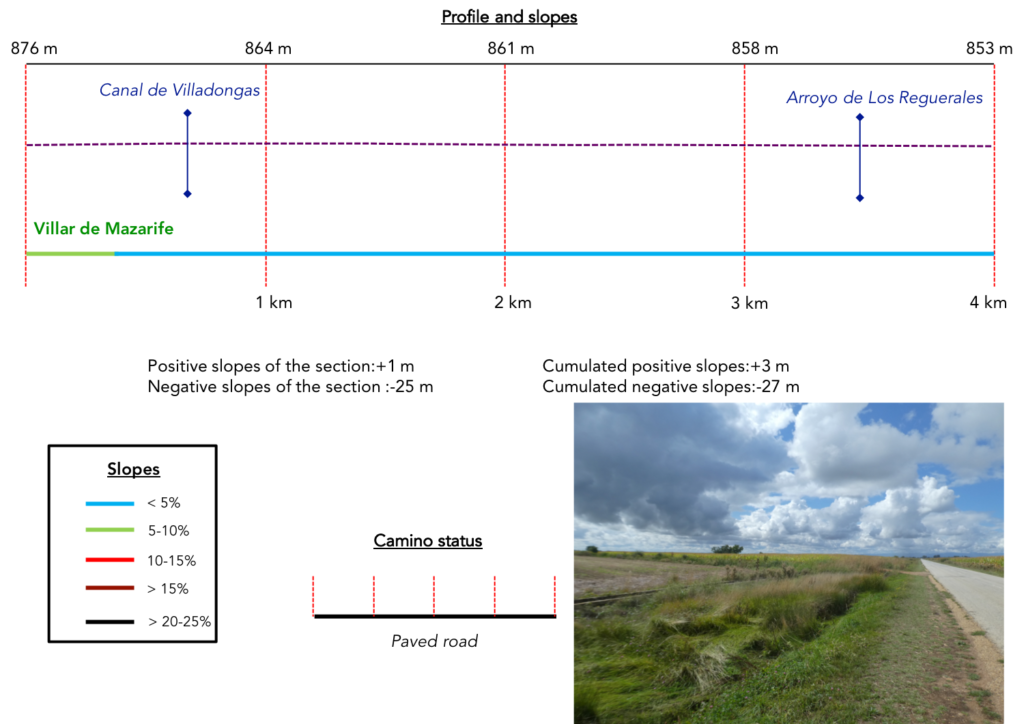

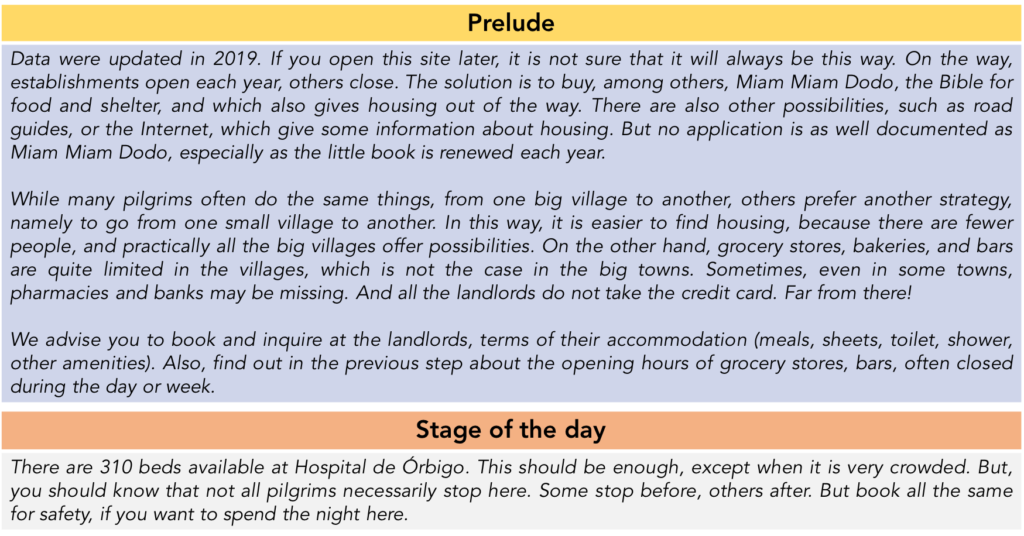

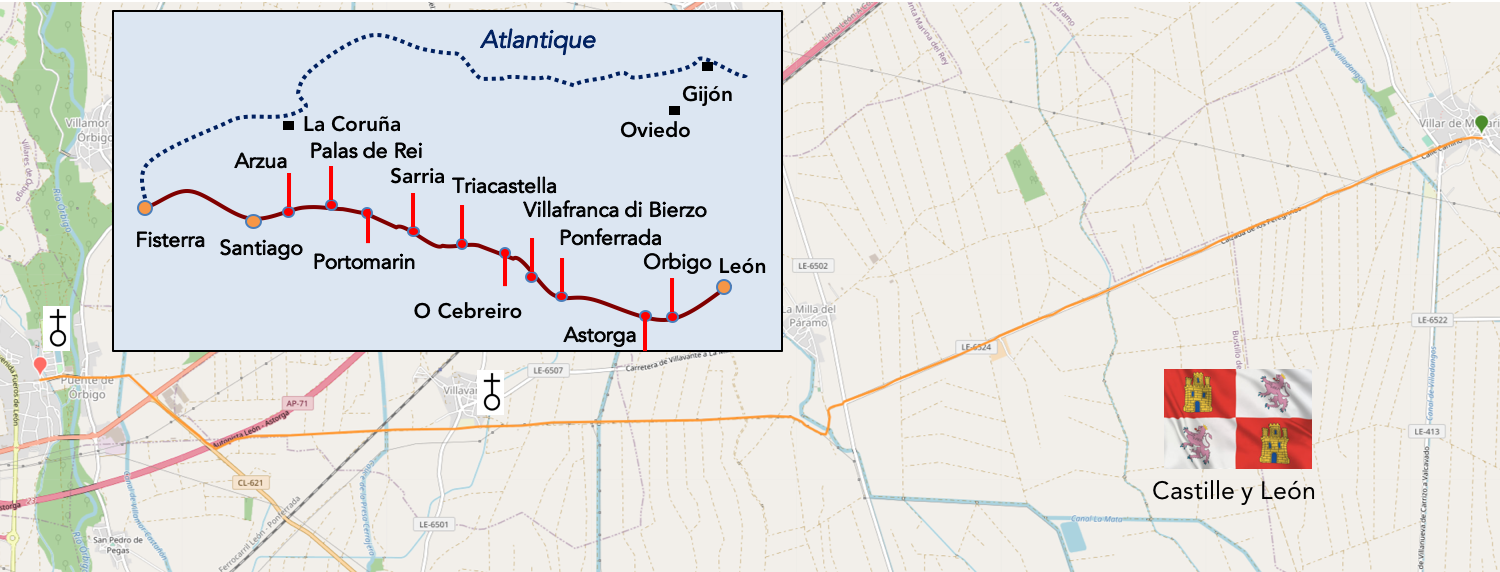

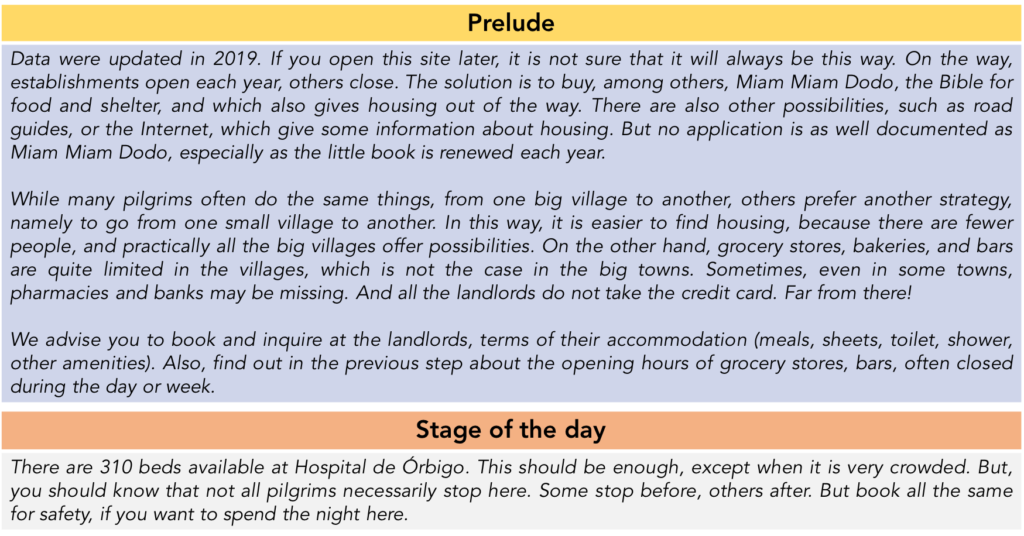

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-villar-de-mazarife-a-hospital-de-orbigo-par-l-camino-frances-123722003

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

We had driven many years ago, between León and Astorga, on the N-120 road. We had seen these cohorts of pilgrims dragging themselves on this deadly axis for them, along the national road. God the guides are liars, who claim happiness beyond León. All that nonsense! In any case, you will have to walk as far as Astorga, and even further, to find some peace of mind. It is however to avoid the N-120 road, that we opted for the Calzada de Los Peregrinos, far from the cars, which is not nothing. As 35 kilometers may seem long for many walkers, we split the stage in two, stopping in Villar de Mazarife halfway through. You saw the course in the previous stage. So, what about this second section, up to Hospital de Órbigo? The stage the day before was pleasant, in beautiful landscapes, at least until Chozas de Abajo. From there, everything went wrong. Here, in this second part of the course, you will swallow corn, nothing but corn, as far as the eye can see, in a plain that never ends. You will have to cultivate your sense of abnegation, tame the monotony, which inevitably eats away at you. But if you still want to see something positive in it, you can regain some of your soul at the sight of the many aqueducts that irrigate this plain all along the route.

Therefore, follow the stage with us. And when it is your turn to choose, consider that if you decide on the traditional route, you will be walking almost all day along the N-120 road. Good luck!

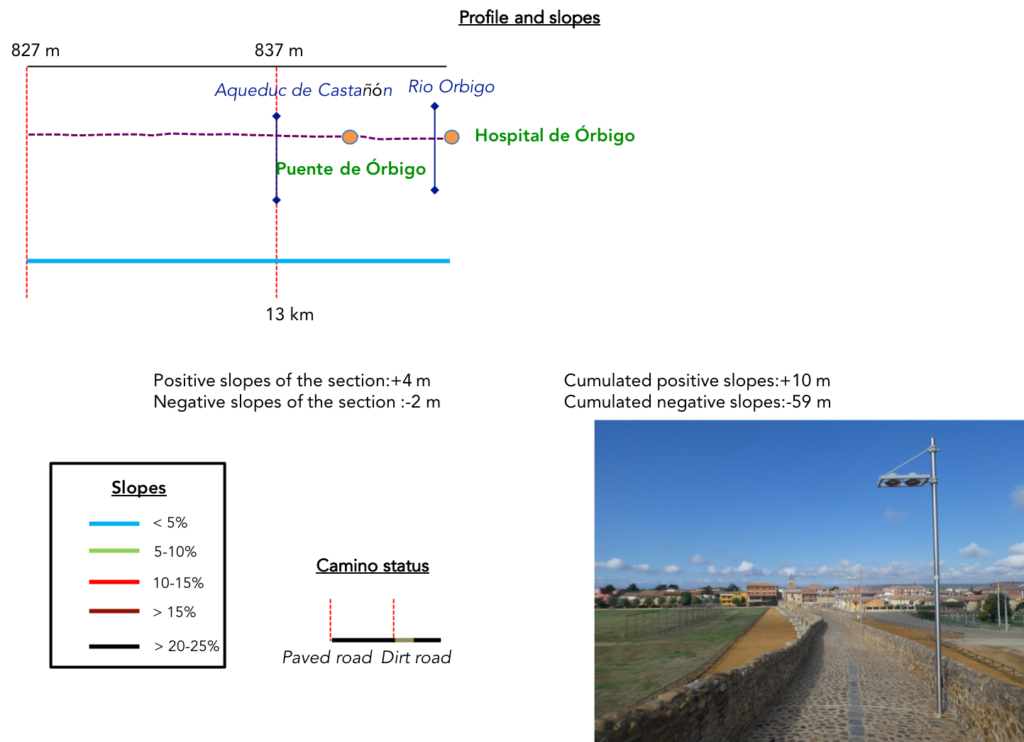

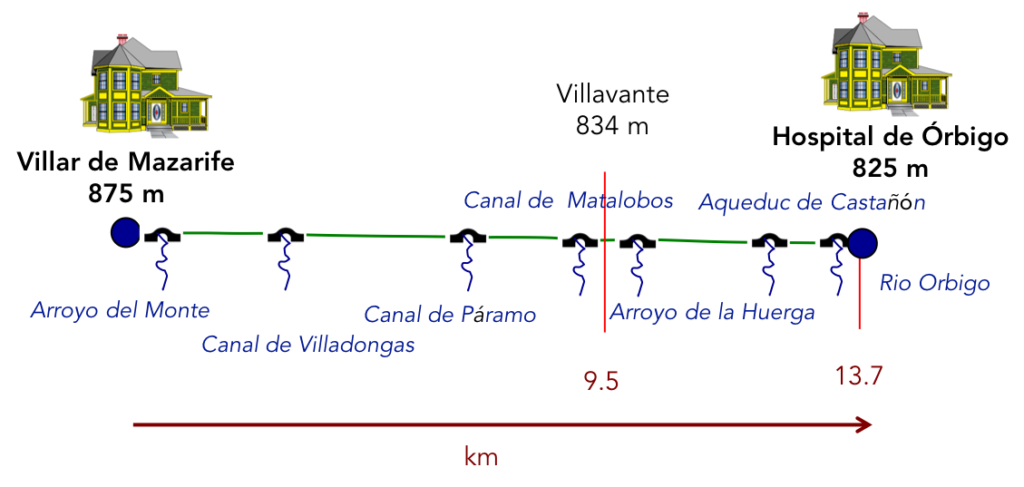

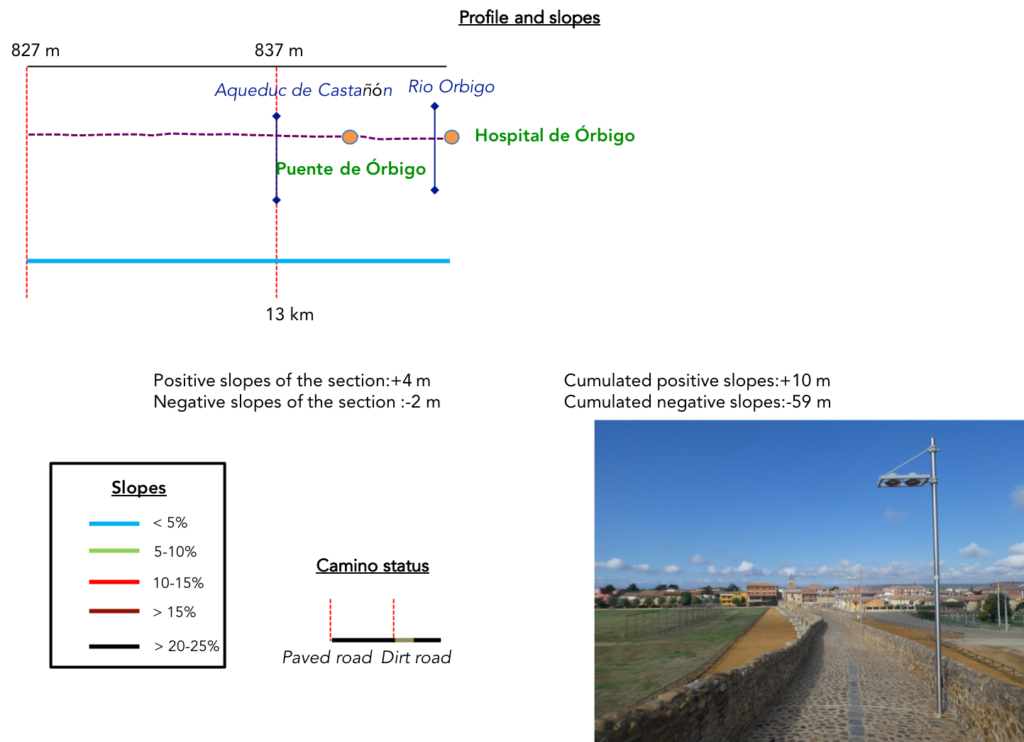

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations today (+10 meters/-59 meters) are almost non-existent.

On the variant, even if you walk quite far from the main axis, there is a lot of road. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. But, here it is cramped, less than 50 centimeters of dirt, grass or bad gravel. You are just as good on the tarmac. But, there are also real pathways:

- Paved roads: 14.4 km

- Dirt roads: 6.6 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

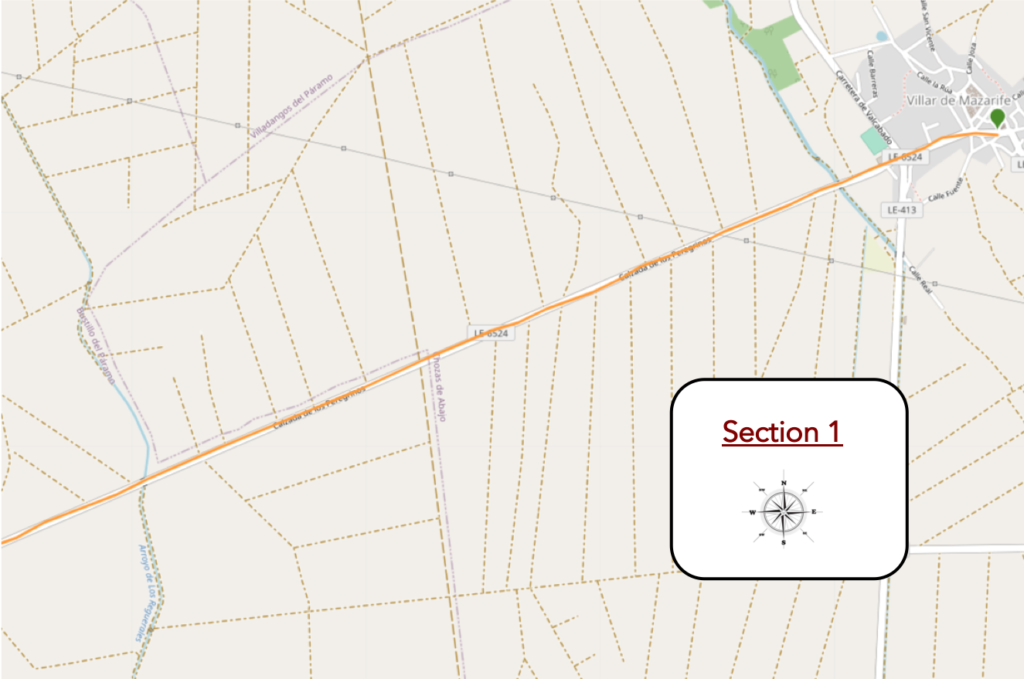

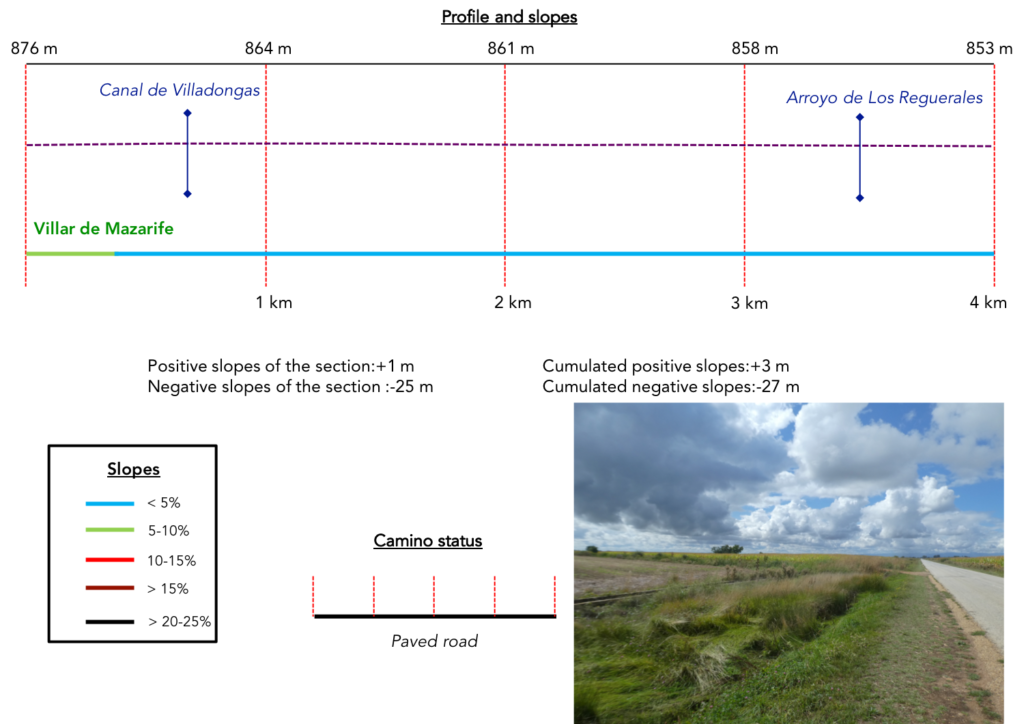

Section 1: A paved road along the cornfields.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| On leaving Villar de Mazarife, you are very happy to learn that you will now be dealing with LE-46524. You are no longer on the Camino de Santiago, but on the Calzada de los Pelegrinos. So, what? |

|

|

| But the country has changed. At the beginning of the Meseta, it was the orgy of wheat and barley. Here, it is still corn, as far as the eye can see. |

|

|

| In this plain that stretches endlessly and sinks who knows where, our psychological endurance is put to the test and often leads to boredom, unless you are passionate about these soulless dangling stems, in autumn. |

|

|

| From now on, you have to walk, your retina glued to these cereals, smiling and blooming. A wall of corn on the left another on the right. And on to the music! |

|

|

| Fortunately, from time to time, your eye can rest on the particular irrigation systems used in this part of the country. |

|

|

| So, you try to understand the mechanism. Canals linked to each other, soak pits, but what else? And where does the water come from, other than rainwater? You guess it more than you really understand But, it passes the time. |

|

|

| Yet your gaze has spent whole days marrying these ugly corn hedges, for all those, like us, who have followed the Way of Compostela in the Southwest, in France. And there it was much more than here and even higher. But, the brain likes to comfort itself in oblivion, when it bothers. |

|

|

Then, suddenly, a pilgrimage milestone. You have crossed the limit of 300 kilometers which lead you to the goal. So here, let’s argue about a small detail. A very long time ago, well before Chozas de Abajo, the marker said 301 kilometers. You have covered more than 10 kilometers since. One of two things, either the Spanish surveyors are merry men, or the companies organizing the Caminos de Compostela in Spain, paid by Europe, have installed this marker 5 minutes before the weekend.

| You never get tired of these landscapes, right? |

|

|

| So, you go back to the details of the side of the road, like this stagnant brackish water, where the toads are silent… |

|

|

| … or the little Arroyo de Los Regueraes stream, which flows who knows where in this endless plain. |

|

|

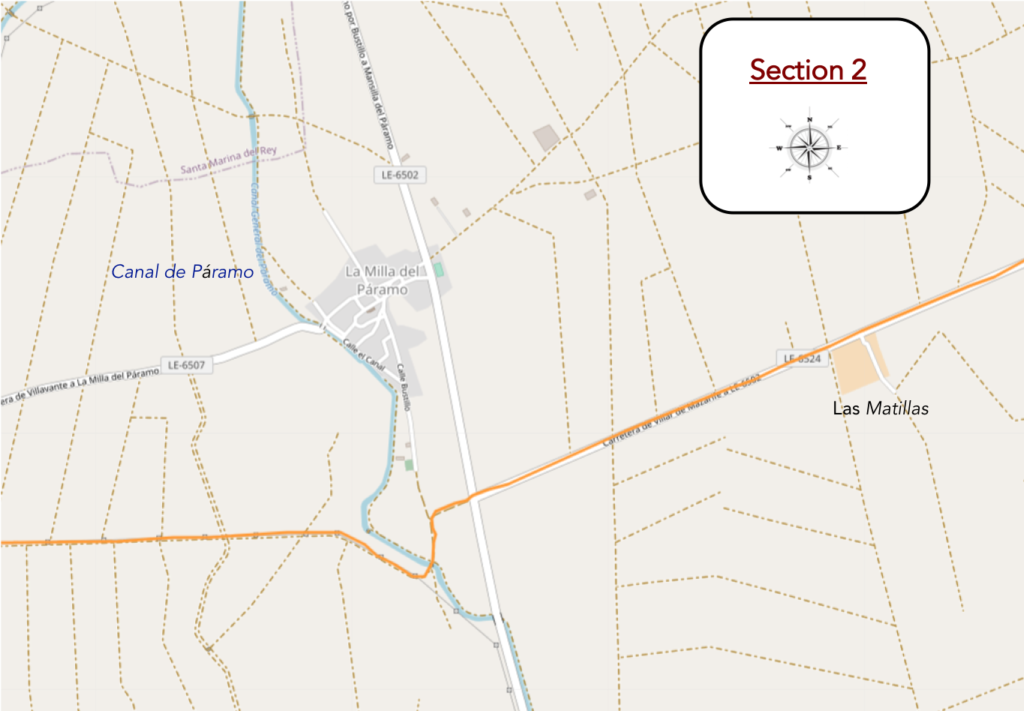

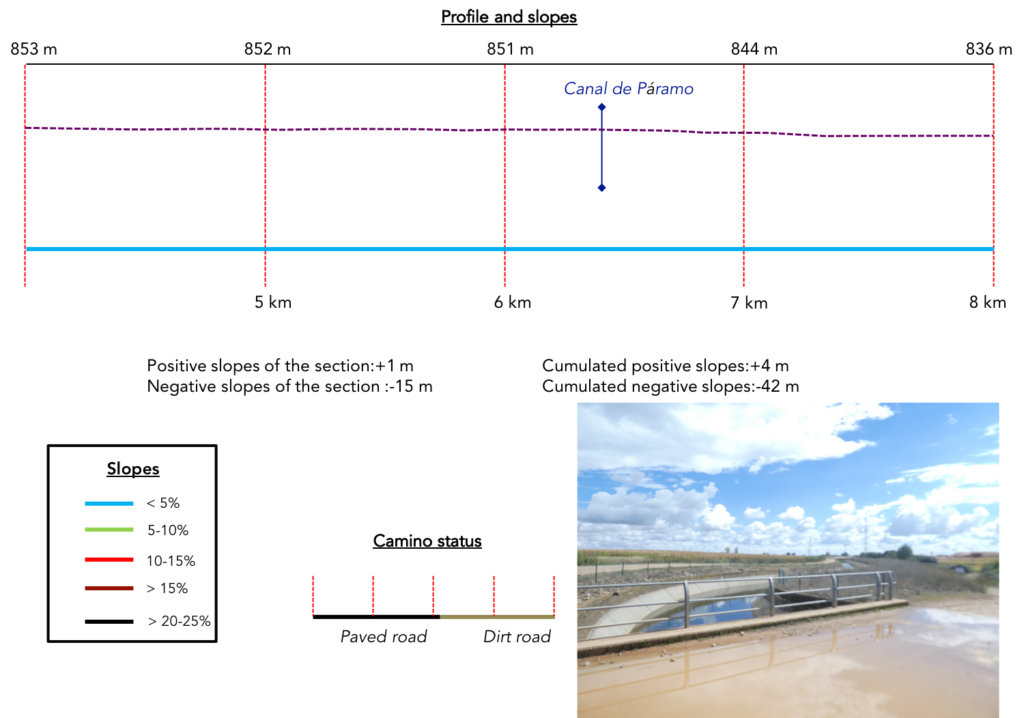

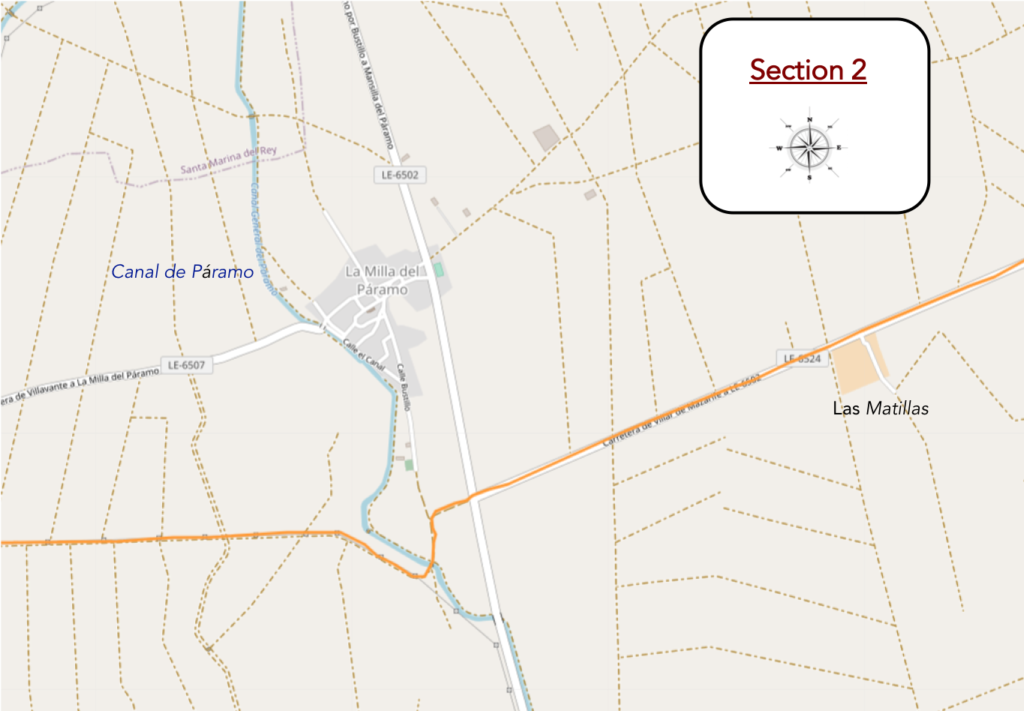

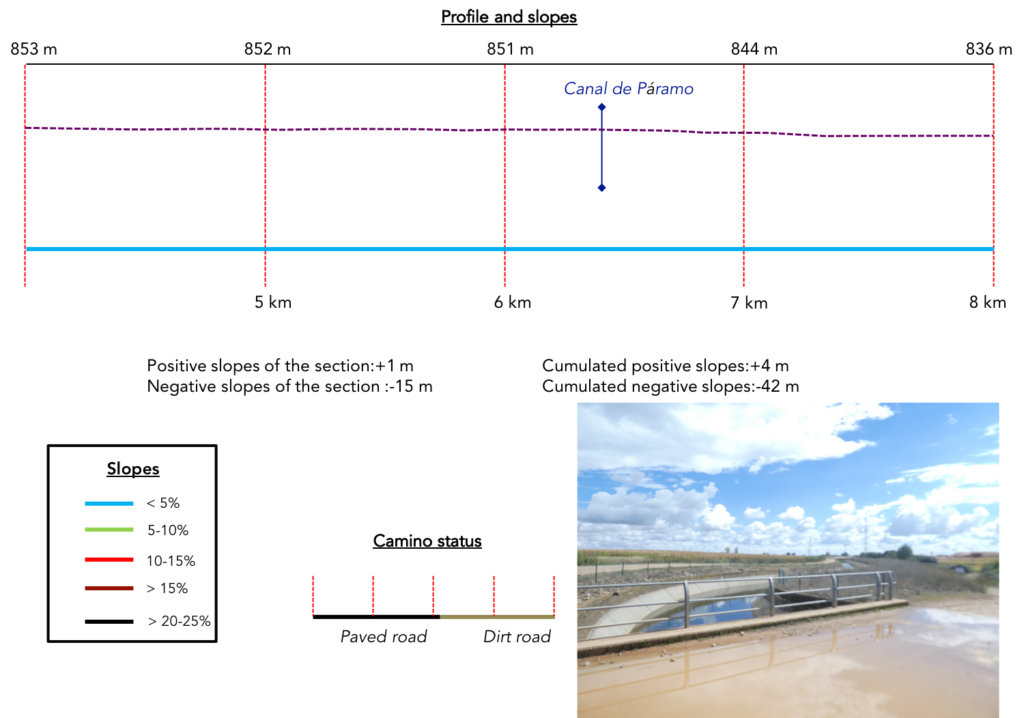

Section 2: In the endless cornfields.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Beyond the stream, the road runs along a fenced property for a long time. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it arrives at the heart of the property, at a place called Las Matillas. The Diputación de León has launched auctions for eight lots of agricultural land in the Las Matillas farm, located in Bustillo del Páramo, for a total area of 80 hectares. The starting price, including rent and duties, is 614 euros per hectare. Try your luck. The lease is for a period of 5 years. |

|

|

| Further on, nothing changes, nothing moves. The banality of corn, nothing but corn, and an endless road. |

|

|

| Then, a rivulet flows, and a village peeks to the side, which the Camino avoids. |

|

|

| Will you go to the end of Spain like this? So, you say to yourself that it would have been better to choose the direct route by the N-120 road. But isn’t the trip the same over there, along the insipid cornfields, in the noise of the engines? Here, no car circulates, it is the only positive side of the business. |

|

|

| Further on, you then have the feeling that everything could change. The road comes to an intersection with a cross road. And dirt is finally coming back. |

|

|

| The pathway abandons the straight line and turns towards a bridge. This is where the Páramo Canal flows, a work inaugurated in 1962. This canal runs 14.5 kilometers, allowing the irrigation of 16,900 hectares, with its branch canals. You finally know where a large part of the water that circulates in the many canals you crossed comes from. |

|

|

| But this curve is only fleeting, only to cross the canal, and the Camino quickly finds the infinite straight line. When you raise your head, your gaze naturally focuses on the distance, here constantly renewed, always the same. And the distance is far ahead of you, that’s its raison d’être. |

|

|

| And small canals, you come across a few in this sea of corn. This area was once a dry, wheat-producing country. But thanks to the canals, and the wells dug to exploit the underground aquifer networks, water is now abundant. This allowed for some crop diversification, such as potatoes and sugar beets. But corn remains the lord, as in many countries where water flows. |

|

|

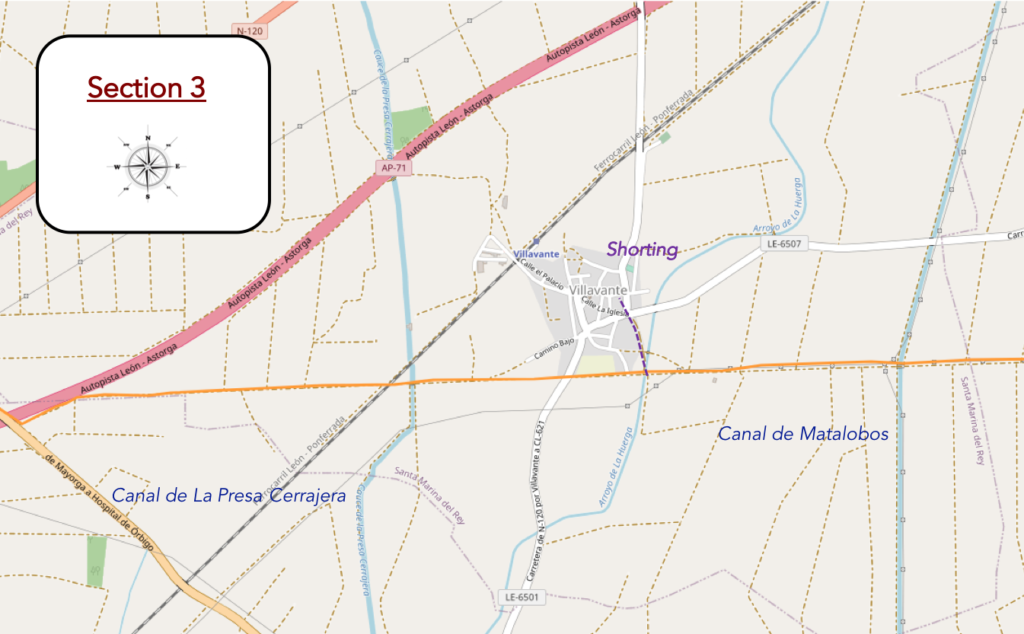

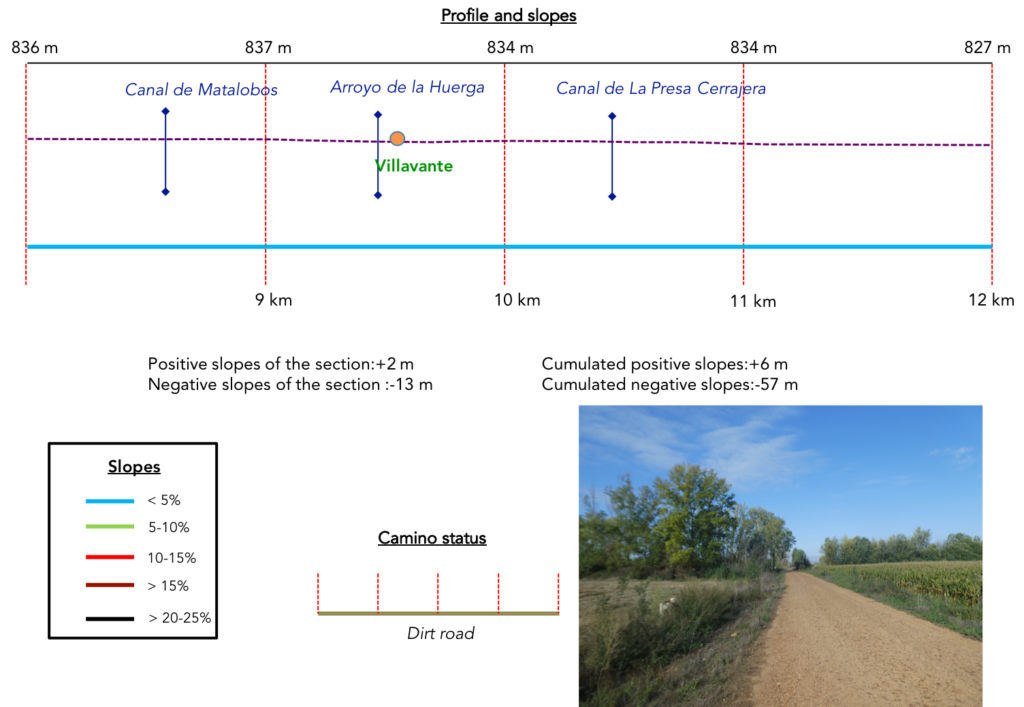

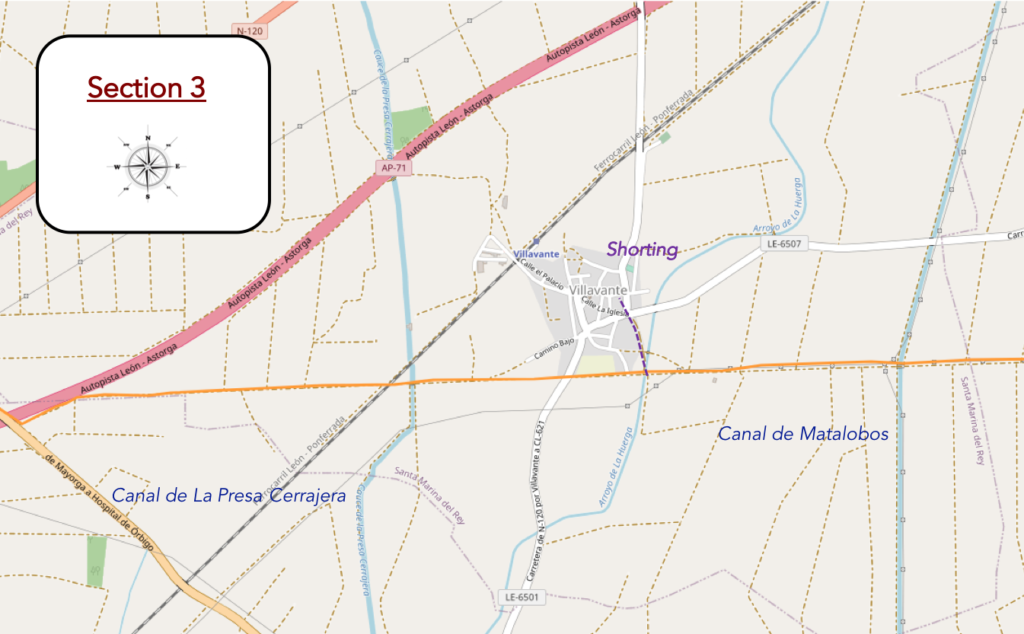

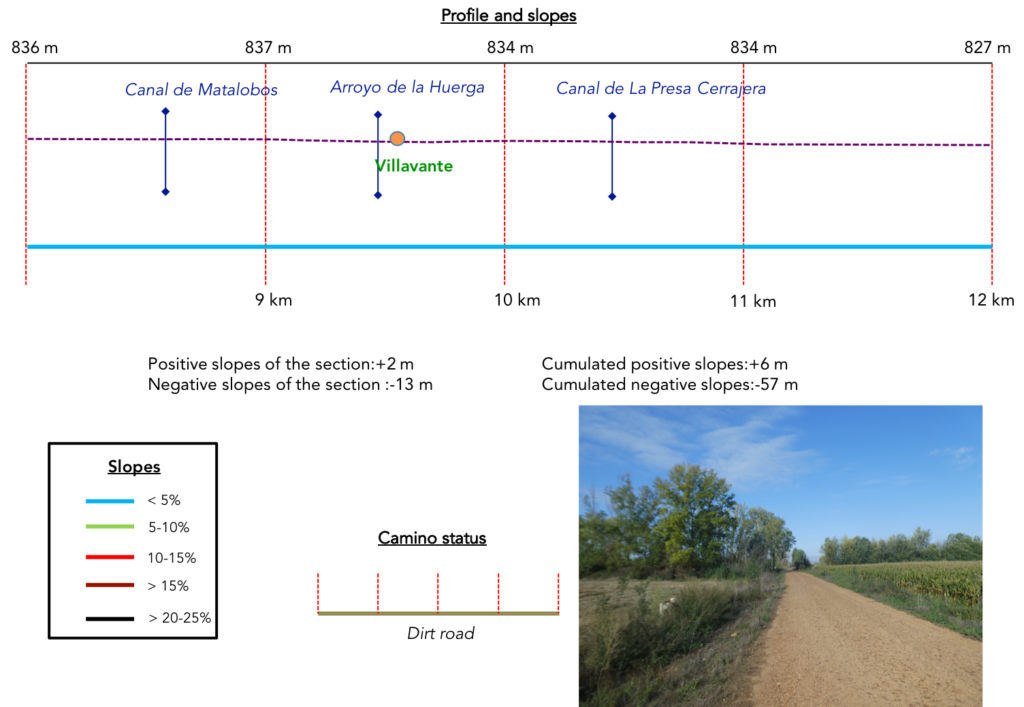

Section 3: A passage through Villavante to restore a little courage.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| The dirt road is quite stony, and you spend most of your time here avoiding stones. You sense that in rainy weather, here must be the absolute pleasure of wading through the mud in a soil that hardly absorbs water. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino finds another channel. |

|

|

This is the Matalobos Canal, inaugurated in 1967. This canal runs 20 kilometers, allowing the irrigation of 6,600 hectares, with its branch canals. Like the Canal de Páramo, it draws its water from a large dam, the Barrios de Lina in the mountains of León.

| Here you are still walking on the Camino de Santiago, as the sign confirms. It is always reassuring. It must be said to you that if by misfortune you had missed a bifurcation, you would have to go back to make the pleasure last. |

|

|

| Further on, you vaguely feel that deliverance is near. There are a few farms along the way. |

|

|

<

| Then, the village of Villavente reaches out to you, hidden behind the oaks. |

|

|

| How can you tell the pleasure of seeing a little stagnant water at the bottom of a well from another age? And then, there are probably humans in the village. When you have spent tens of kilometers, sometimes with a pilgrim, 500 meters in front or behind you, you need a little human warmth. |

|

|

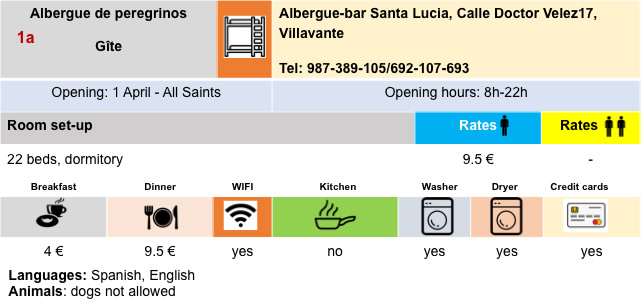

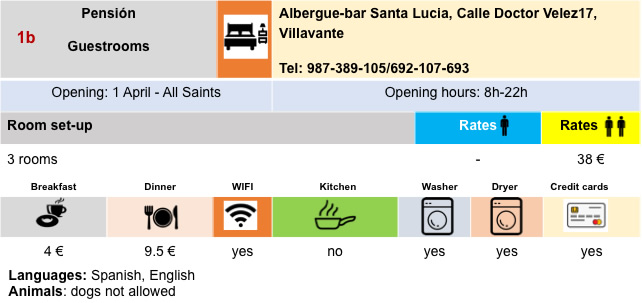

| The route does not go to Villavante, but it is good to take a trip there, to rest your retina a little with something else to see and soothe your soul. It is a village, like the others, with its “albergue” and its small church. |

|

|

| You have to return to the starting point of the shortcut to the village to continue the route. |

|

|

| Now the weather is very nice in Castile and the tractors are there. |

|

|

| The dirt road runs along the bottom of the village and out. Again, here a tribute to St Jacques. |

|

|

| But you are not done with the corn fields, far from it. |

|

|

| Further on, the trees are back, above all oaks and poplars. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway meets another irrigation canal, the Canal de La Presa Cerrajera. Corn, fond of water, should not have a dry throat in the region. |

|

|

| It is right next to it that you have to cross the railway line, at risk and peril. But it is not the TGV that passes through here. |

|

|

| It’s always straight, no surprises. Corn, you are now accustomed to the point of ignoring it. |

|

|

| So, to pass the time, you replay the game of landmarks, because everything over there passes the highway. |

|

|

| But, it is still far, too far, almost half a kilometer to get there. The monotony is both disturbing and reassuring, an unstable balance, which here the tireless repetition of artificial nature created by men imposes on you. |

|

|

| So, you start dreaming when you finally see a big truck driving on the highway. You are at the end of this endless penitence. |

|

|

| The dirt road then runs along the highway for a while, before crossing it on a bridge. |

|

|

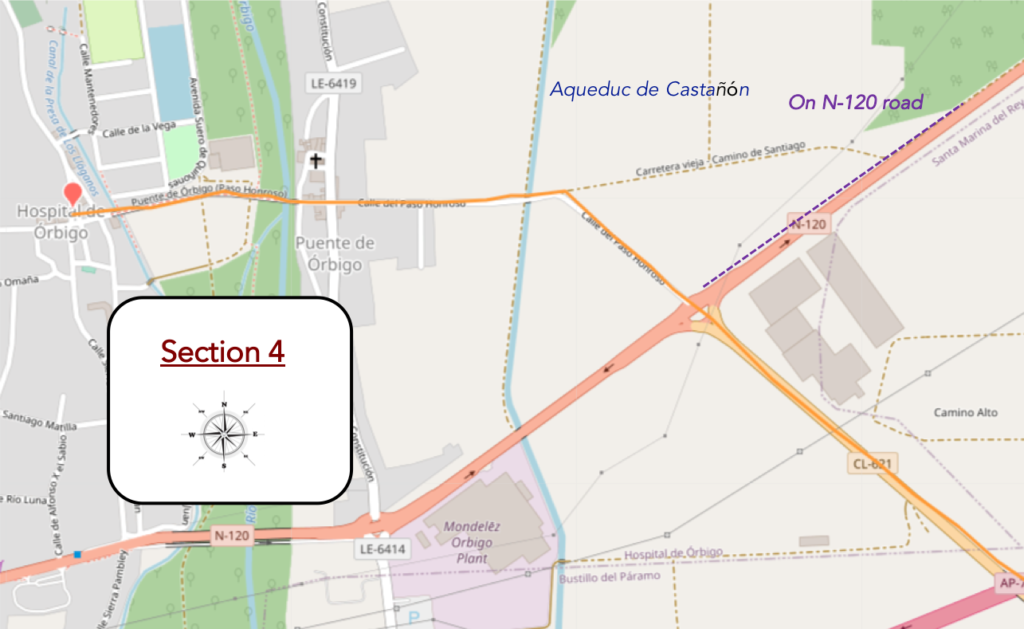

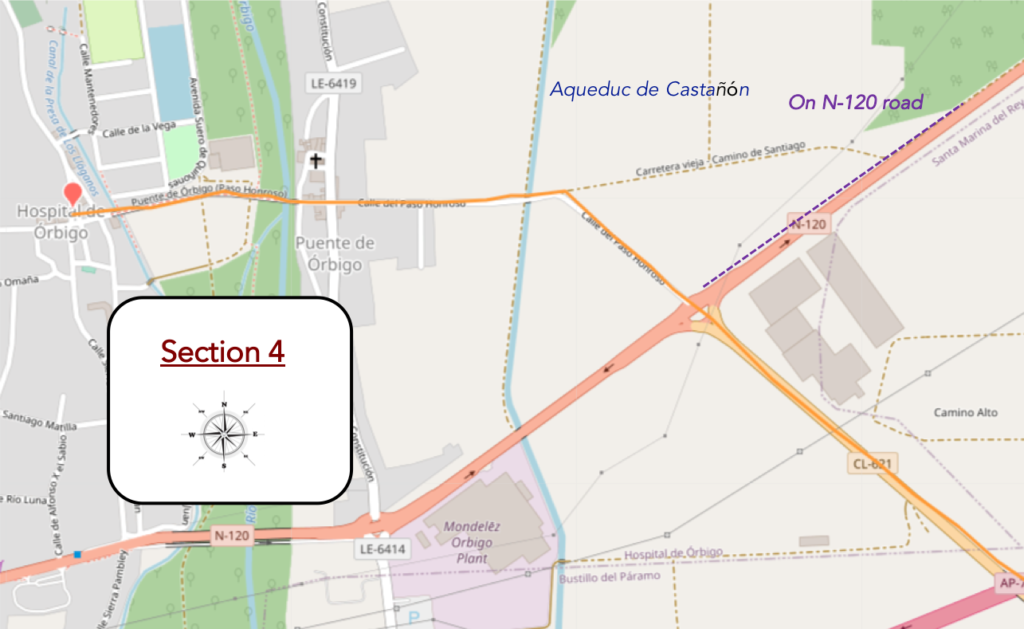

Section 4: Fortunately, there is Hospital de Órbigo at the end of the road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Further ahead, the Camino runs along a secondary road to return to the N-120 road. |

|

|

| There it crosses a large crossroads where the N-120 road passes and continues straight. |

|

|

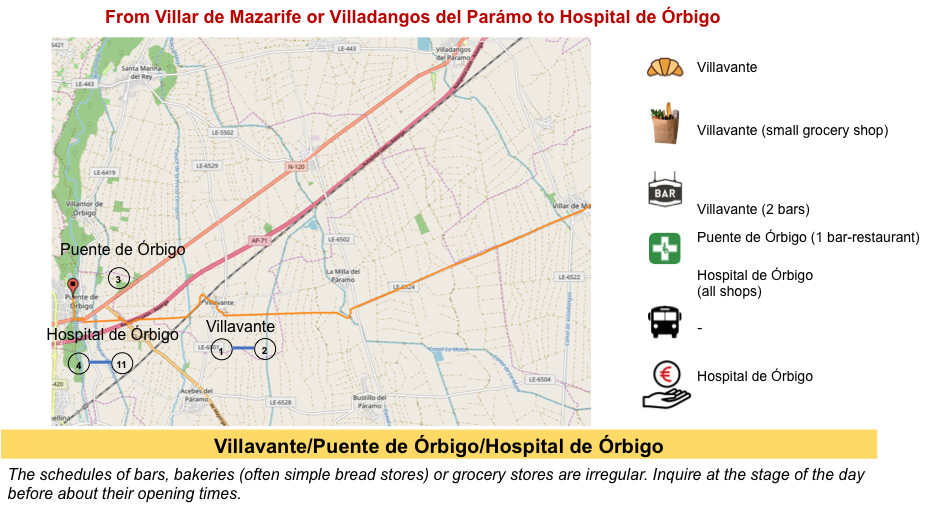

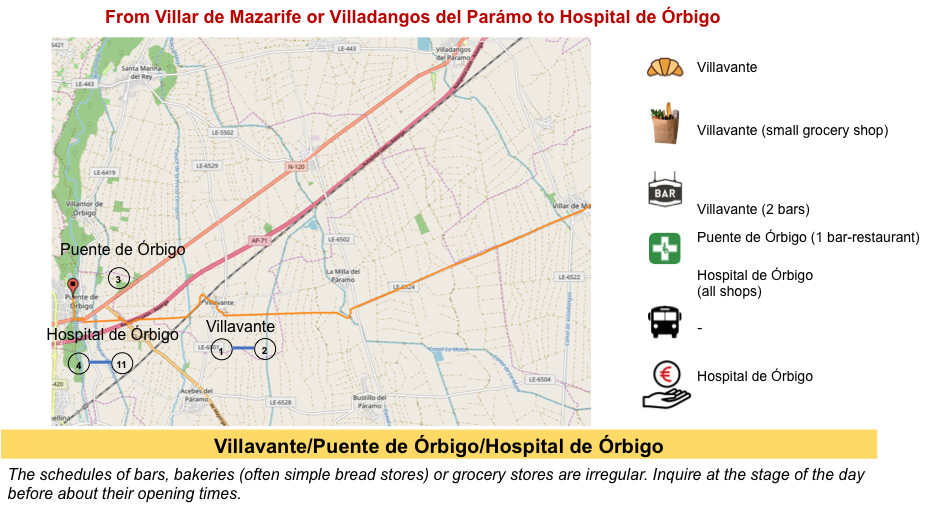

| Shortly after, the route joins the traditional Camino that returns from the N-120 road and flattens on a dirt road towards Puente de Órbigo. It is there that it is easy to see that the bulk of the troop has gone through this route. It’s no surprise. As soon as it’s shorter, pilgrims go through it. Your galley comrades will have spent hours watching cars driving on the road. 27 kilometers is a long time, and they will have swallowed as much corn as you. So, play heads or tails to find out which course you will take. |

|

|

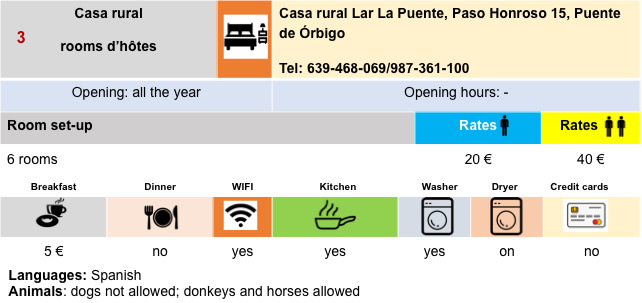

| The Camino then enters the village of Puente de Órbigo. Puente de Órbigo and Hospital de Órbigo are the same village, two villages separated by the bridge. In ancient times, there was undoubtedly a ford on the Río Órbigo, a sort of strategic transport node, leading the Romans to establish a colony here. Later it was the site of many battles. In the Middle Ages there was a small village here, on the east bank of the Río Órbigo which had formed around the Church of Santa María. The bridge has facilitated trade since Roman times, gold for the Romans, then cattle, finally pilgrims. |

|

|

Along the way, the route crosses the magnificent Aqueduct of Castañón, a work dating back fifty years, which irrigates more than 4,000 hectares of cultivable land in the region.

| The Camino crosses Puente de Órbigo. Before the bridge stands the XVIIth century hermitage of Our Lady of Purification. You will find stork nests there. The swamps provide enough food for the storks to stay here all year round. |

|

|

| It is here that the Rio Órbigo flows at a low rate, between the two villages. The river is a sub-tributary of the Douro. |

|

|

| This bridge is just amazing. The Puente de Órbigo bridge is the longest of the Camino, with its 200 meters. It is one of the best-preserved medieval bridges in Spain, dating from the XIIIth century and built over an old Roman bridge that was on the old Roman road Via Aquitania, from León to Astorga that linked the silver mines from El Bierzo to France. There may have been a ford or an even older bridge that was remodeled by Roman engineers. The bridge seems too big for the river, but before the construction of the Barrios de Luna reservoir, the river was much wider. But, as the water from the dam is poured into the canals as much as into the river, its flow has been reduced. Floods have washed away one or more of the arches of the bridge at least five times since the XIIIth century. As a result, the bridge has been transformed several times during its history, but retains part of its original structure with its pointed arches. This national monument was also part of the Roman road from León to Astorga. |

|

|

| A noble knight from León, Don Suero de Quinones, from an illustrious family in the Páramo region, was despised by a beautiful lady, Doña Leonor de Tovar. He made a promise to fast every Thursday and to wear a heavy iron ring around his neck as a symbol of his love for her. Then he obtained permission from King Juan II of Castile to organize a special tournament in which he would challenge all the men passing through the Puente de Órbigo. Only unarmed pilgrims were allowed to cross. He threw down the gauntlet to any knight who dared pass as he set out to defend the bridge and his honor in the process. If they refused to participate, they had to lay down a glove as a sign of cowardice and ford the river. The king invited the best knights of the kingdom to take the road to the Hospital de Órbigo. Those attempting to cross the bridge engaged in single combat with Don Suero or one of his 9 companions. They had to break a total of 300 spears. Sixty-eight knights from all over Europe took up the challenge. Don Suero successfully defended the bridge for a whole month. He was supposed to continue until 300 spears were broken, but Don Suero was injured, with the contest judges deciding that 166 broken spears was enough to release Don Suero from his pledge. Suero de Quiñones died 14 years later at the hand of a former adversary, an ancestor of Cervantes. These characters contributed to the personification of his Don Quixote. This historical fact of chivalry is related by Cervantes in his Don Quixote. Ten years later, the de Quiñones family received possession of the bridge from the Order of Saint John, in return for looking after the interests of the Order in the area. |

|

|

| At the end of the XVIth century, another village was organized for pilgrims, on the west bank of the Río Órbigo. This is Hospital del Órbigo (1,200 inhabitants). A hospital for pilgrims was founded there by the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem. The hospital operated until 1850. Then, in 1808, the English troops had to withdraw towards Galicia, forced by the pressure of the French army commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte in person. They then largely destroyed the bridges to delay their pursuers. Such a waste!

At the exit of the bridge starts the Calle Mayor, the main street of the village. This is the street of historic houses, a little more opulent than in the villages we passed. Many houses are of exposed brick, as throughout the region. |

|

|

|

|

| The current Church of San Juan Bautista dates back to the XVII-XVIII century, in a combination of Baroque and Neoclassical style built in stones, in the shape of a Latin cross with a bell tower bearing bells. You may see storks there. Originally, in the second half of the XIIth century, the church was built for pilgrims, then handed over to the Order of San Juan of Jerusalem, who built a hospital for pilgrims nearby. This one has disappeared. |

|

|

| The very pleasant village is full of tourists and pilgrims, bars, restaurants and “albergue”. |

|

|

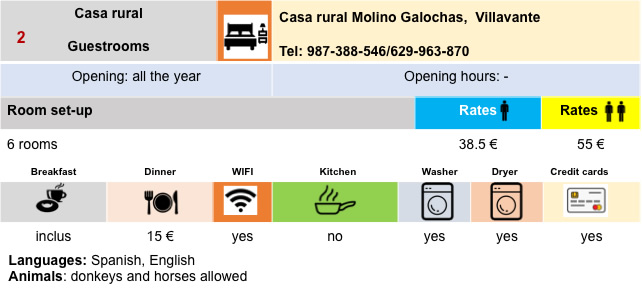

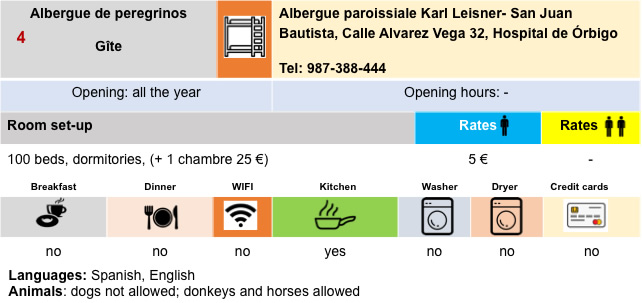

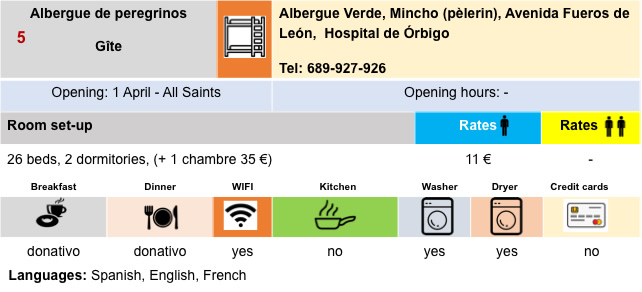

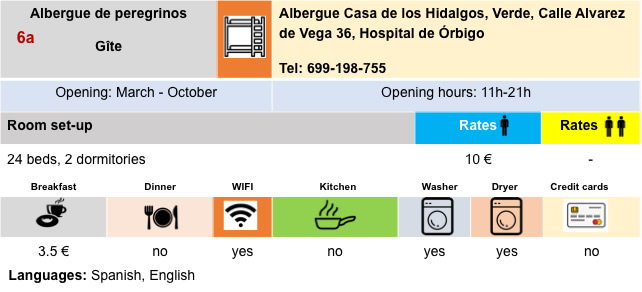

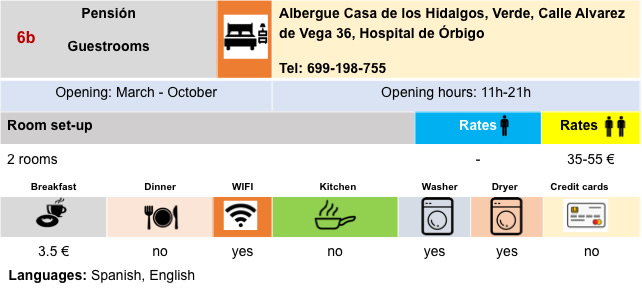

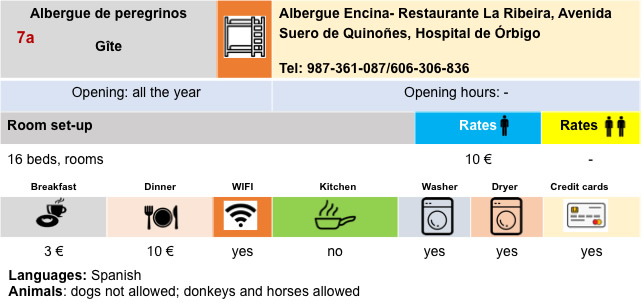

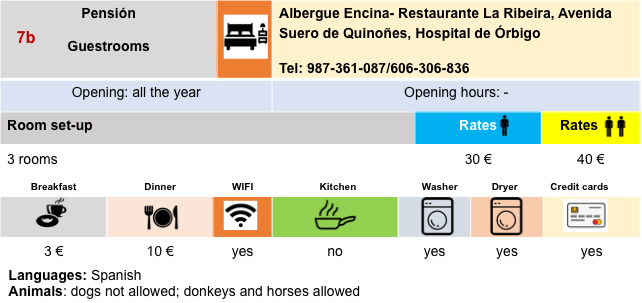

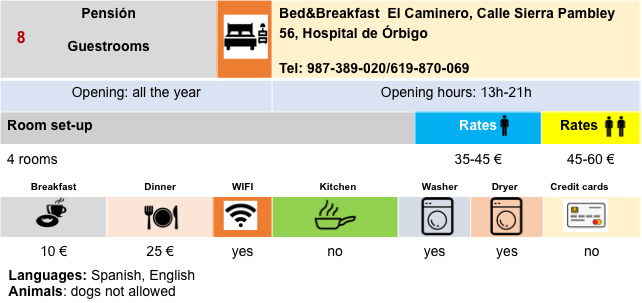

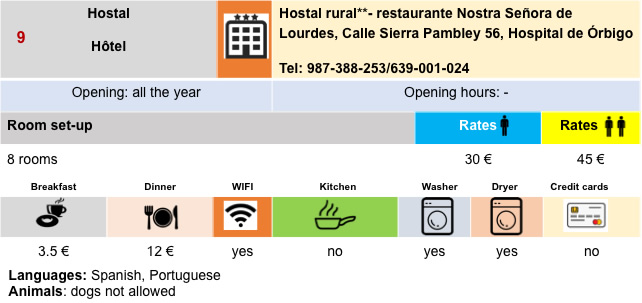

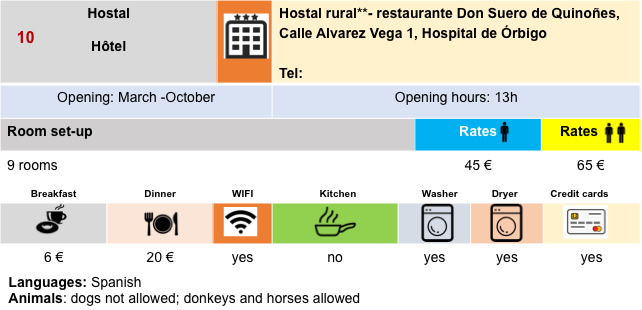

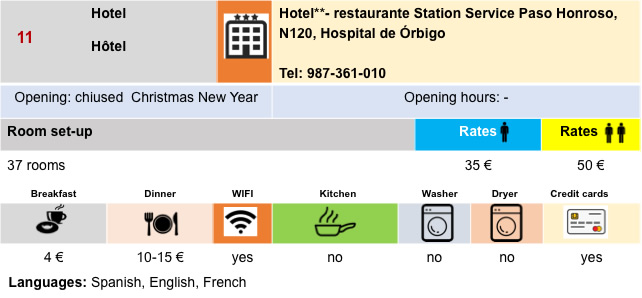

Housing

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 3: From Hospital de Órbigo to Astorga |

|

|

Back to menu |