You leave the Meseta for a beautiful city

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

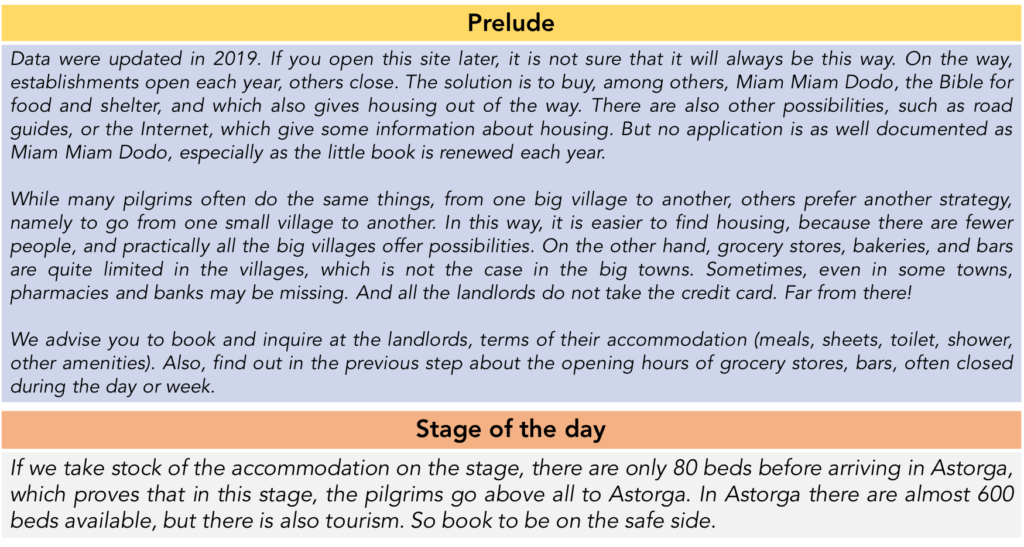

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-hospital-de-orbigo-a-astorga-par-le-camino-frances-43259715

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

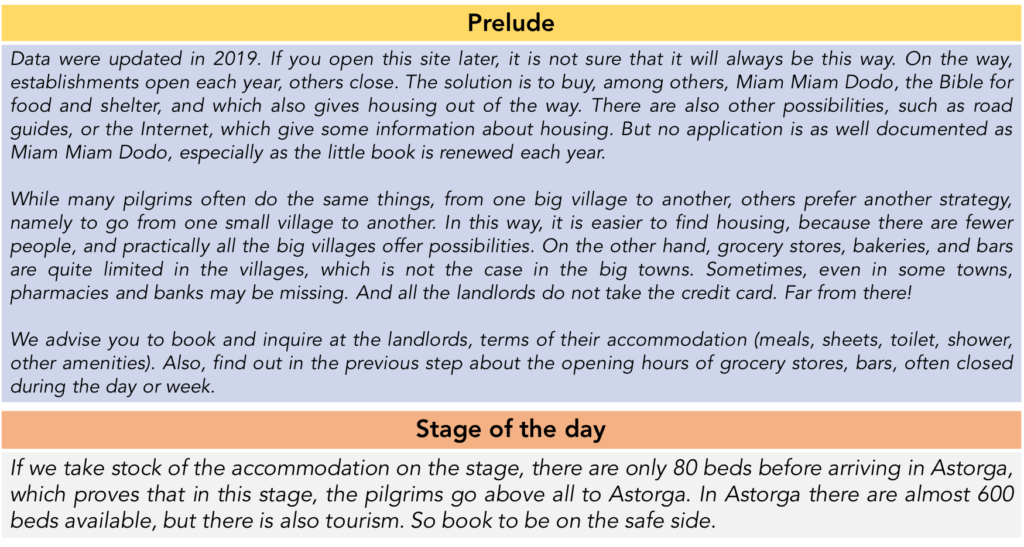

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today is a magnificent stage, one of the most beautiful of the Camino francés. For once, you will leave behind you the coldness of the cornfields on an endless straight road. Here, it is a bucolic, hilly country that awaits you. This route will reconcile a large part of the army of pilgrims with the Spanish route. Because, make no mistake, in the “albergue” the discussions are going well. Some are reluctant to shorten the trip. Others look at train schedules. This is not the beautiful track so dreamed of. However, if they had inquired before leaving, they would have known that the Meseta is something to be earned. So today they will walk with pleasure on the ocher ground, among oaks and pines, from one hill to another, to end the journey in Astorga, a real gem, an open-air museum, where it is good to sit in the Plaza Mayor for an aperitif before lunch. If it’s not raining.

Astorga sits on a steep ridge with an array of historic buildings tightly packed within its medieval and Roman walls. Before the arrival of the Romans, Astorga was home to the Celtic Astur tribe. The Roman legion Legio X Gemina, settled on the hill where the center of the city is today. In 14 BC, the Romans founded the city there, which they named Asturica Augusta. It became an important Roman fortified town due to its dominant position at the junction of several main roads and the presence of numerous gold mines in the area. Asturica was the main city in northwestern Spain during the Roman Empire. The first city walls date back to the IVth century AD. The Moors, then the Visogoths looted the city Its real revival came in the XIth century, when the town became a major stop on the Camino. Astorga was a place where pilgrims rested and prepared to climb the mountains to the west. This is where the Camino francés (part of the Vía Trajana connecting Astorga to Bordeaux) and the Calzada Romana (i.e. Vía Aquitania) joined the Roman Silver Route (Vía de la Plata) from Seville and the south. This convergence of routes gave rise to 22 pilgrim hospitals at the height of the Camino de Santiago in the Middle Ages.

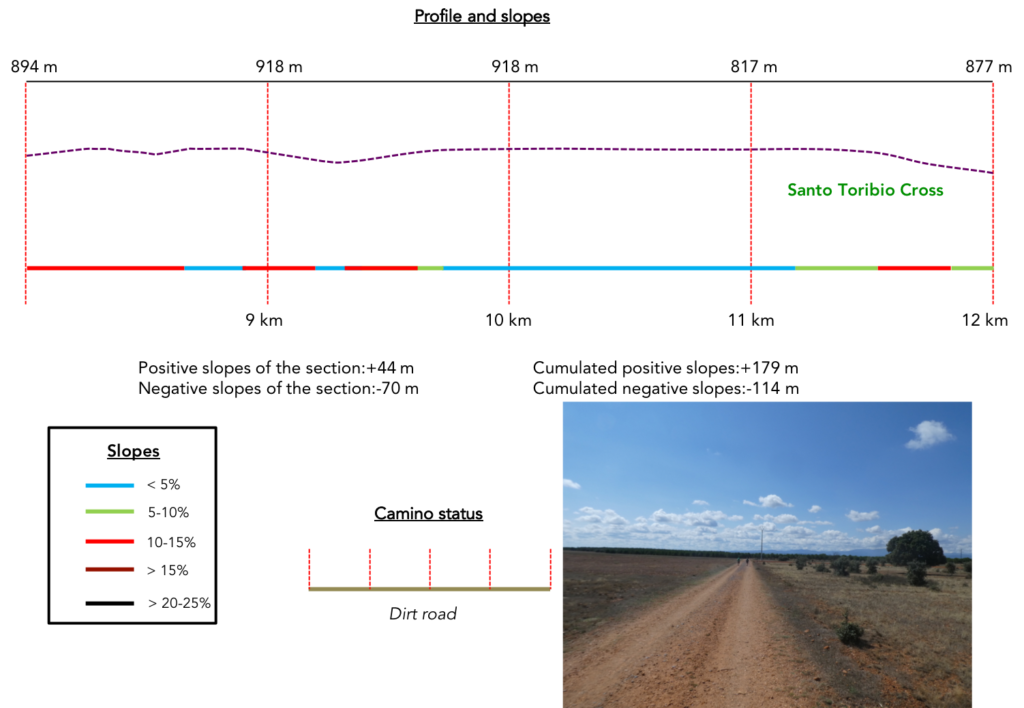

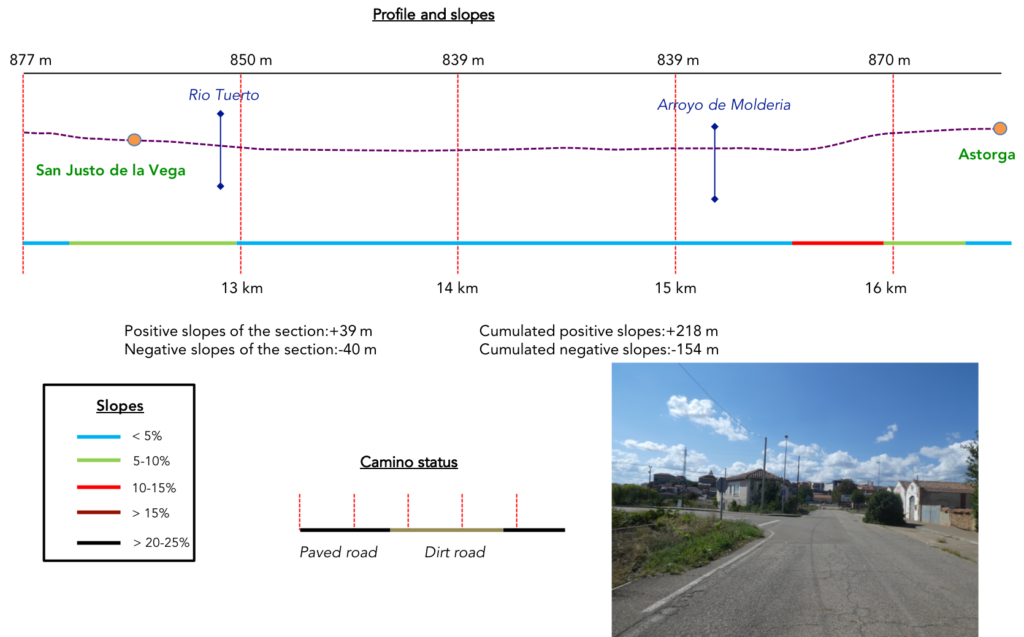

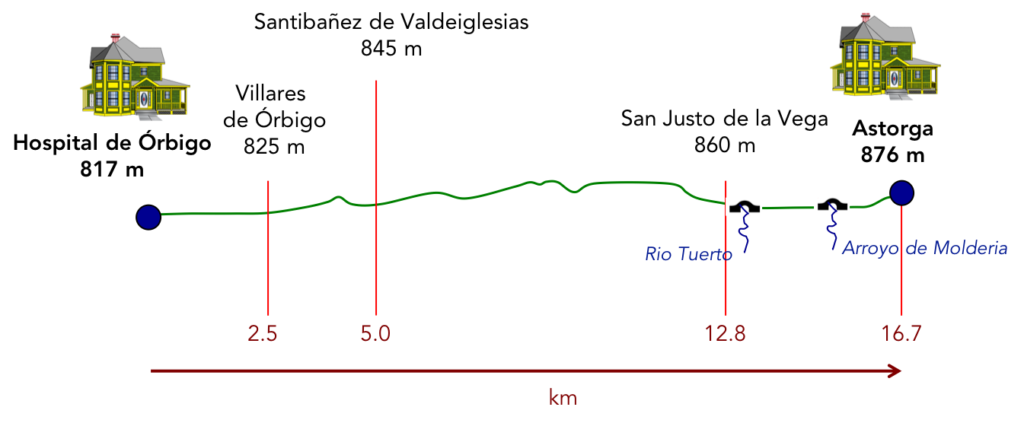

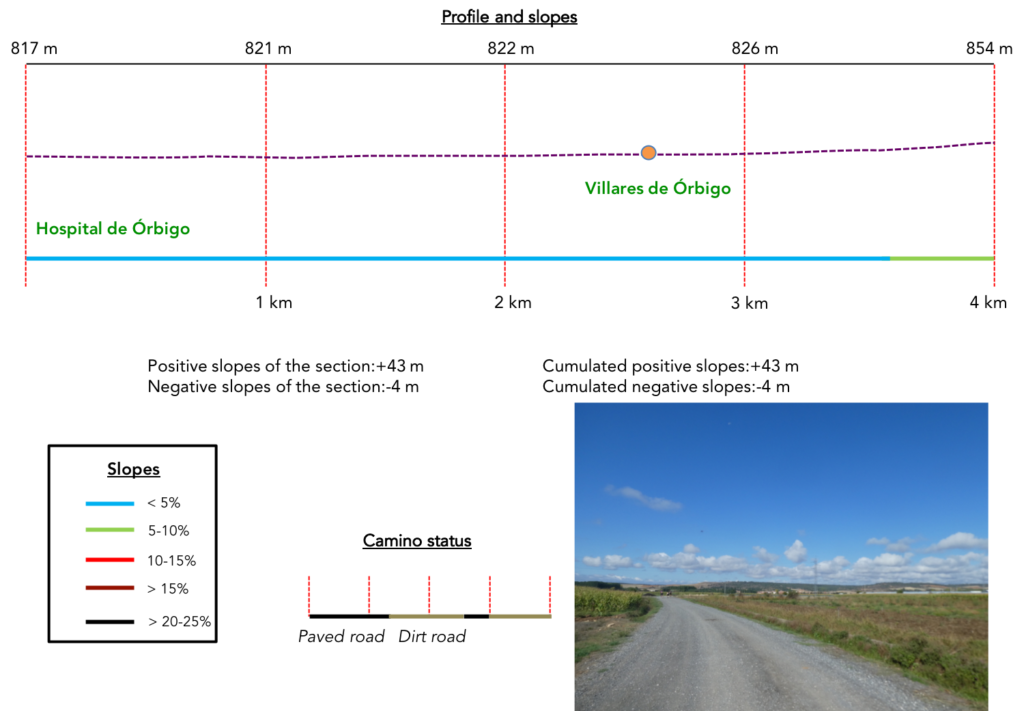

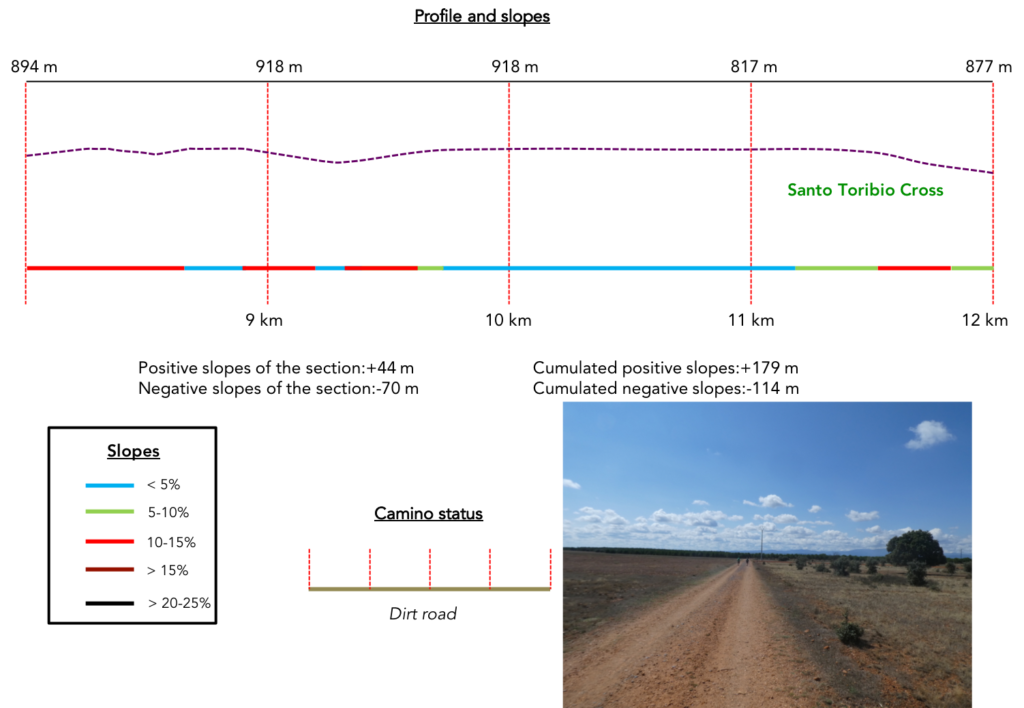

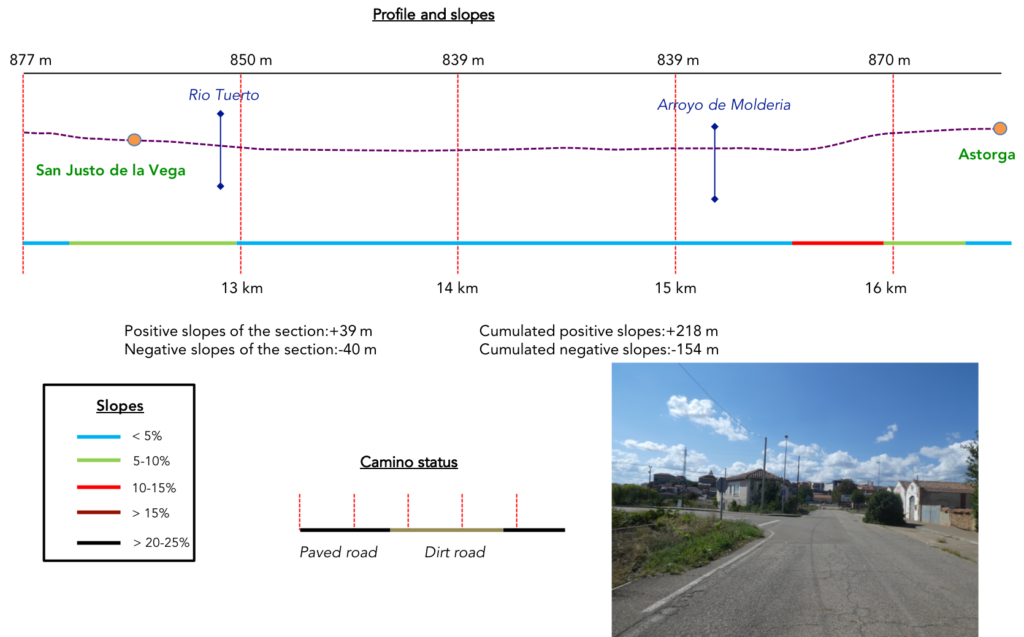

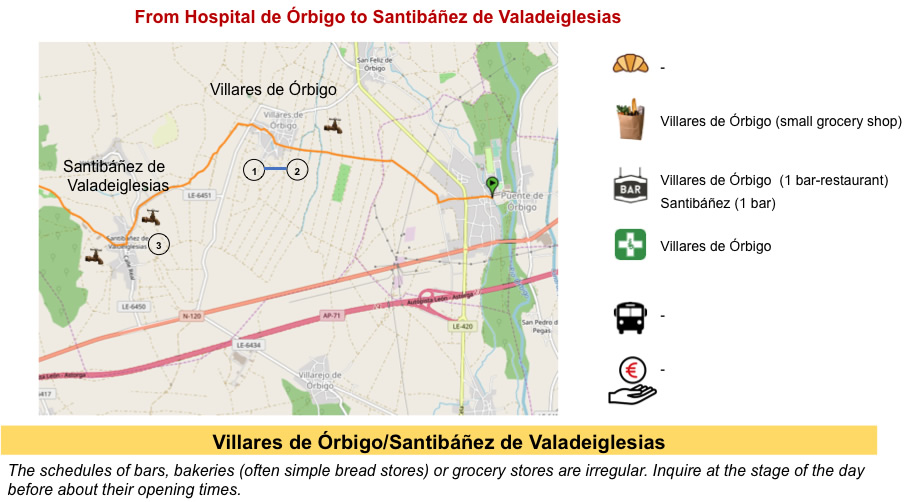

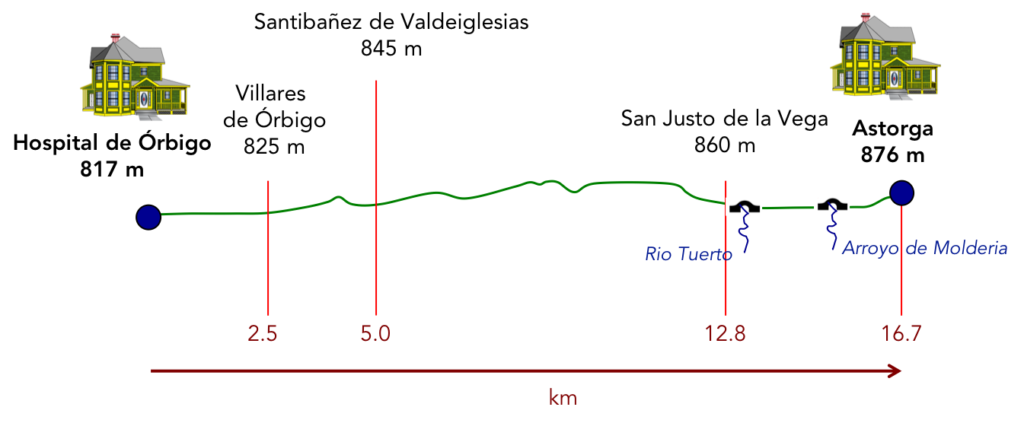

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations today (+218 meters/-154 meters) are again very low. However, you will have the feeling that the course is much steeper than that. But, there are many almost flat passages.

Today the pathways clearly have priority, as is the norm in Spain. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road. But, there are also real pathways:

- Paved roads: 5.6 km

- Dirt roads: 11.1 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

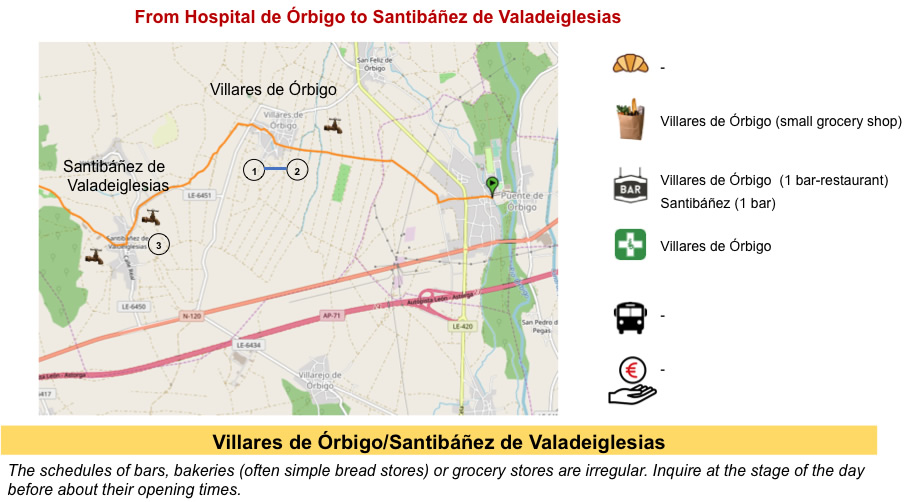

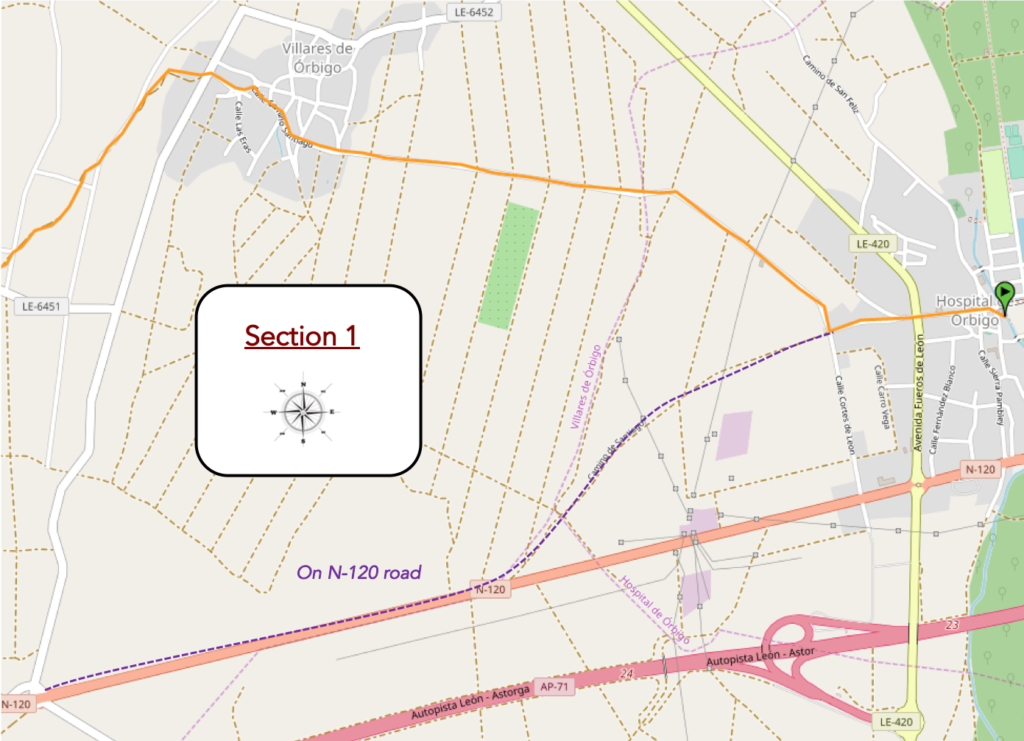

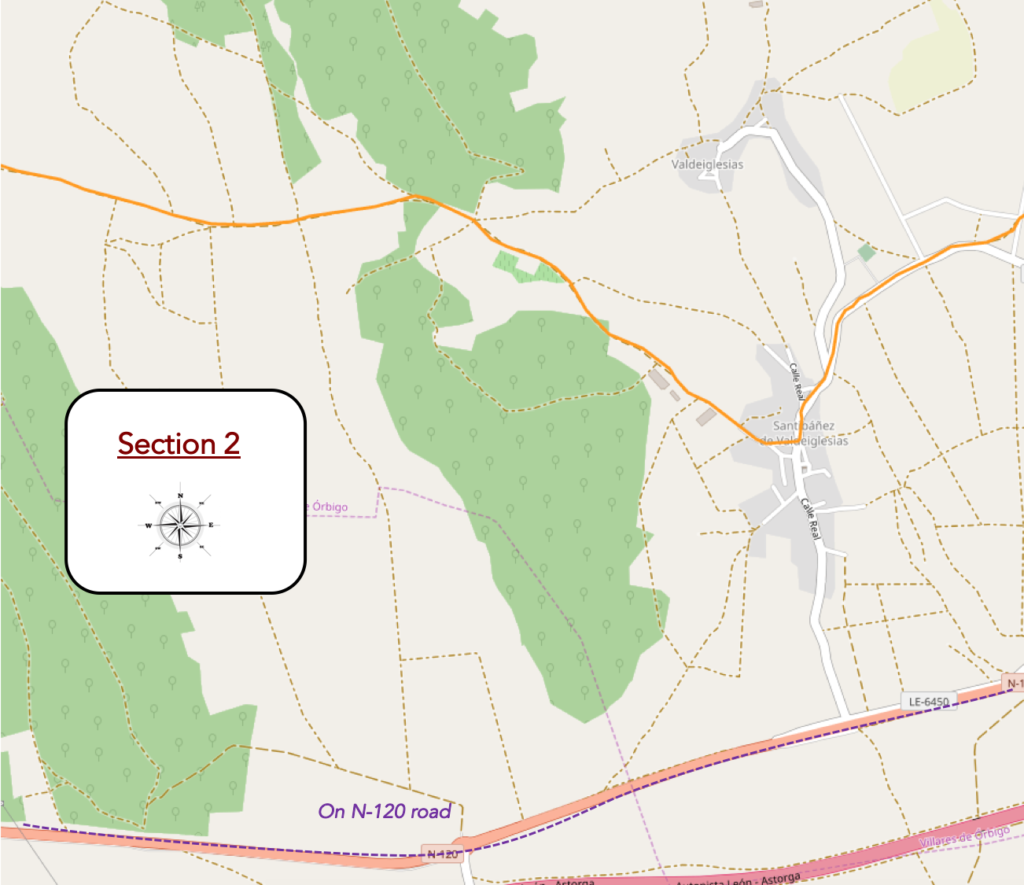

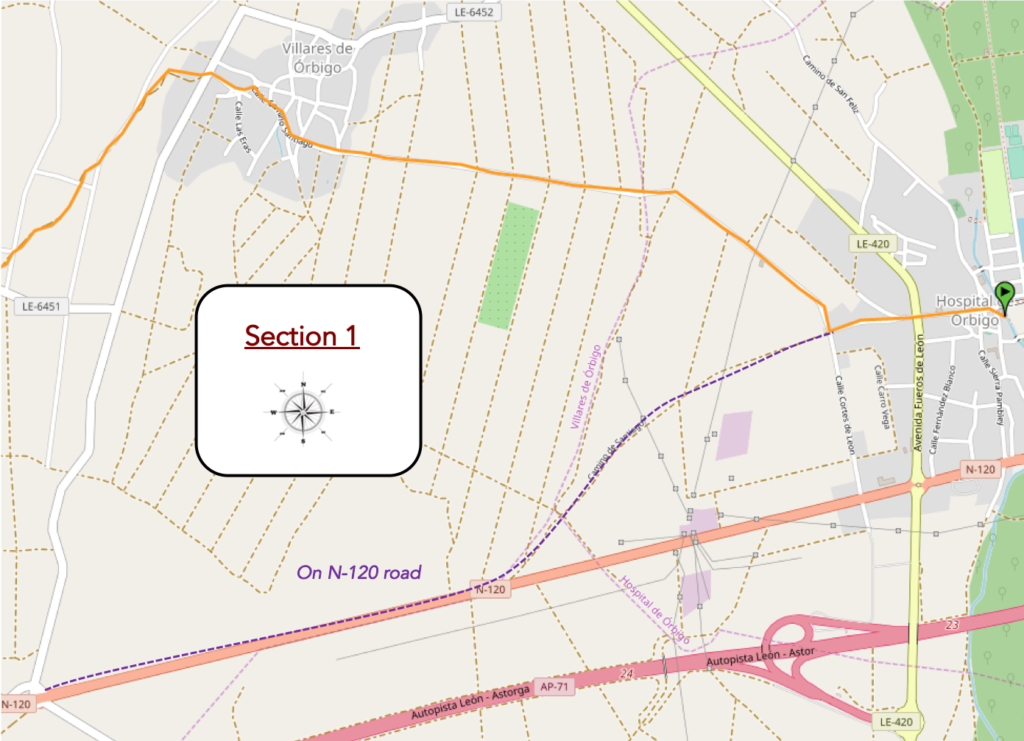

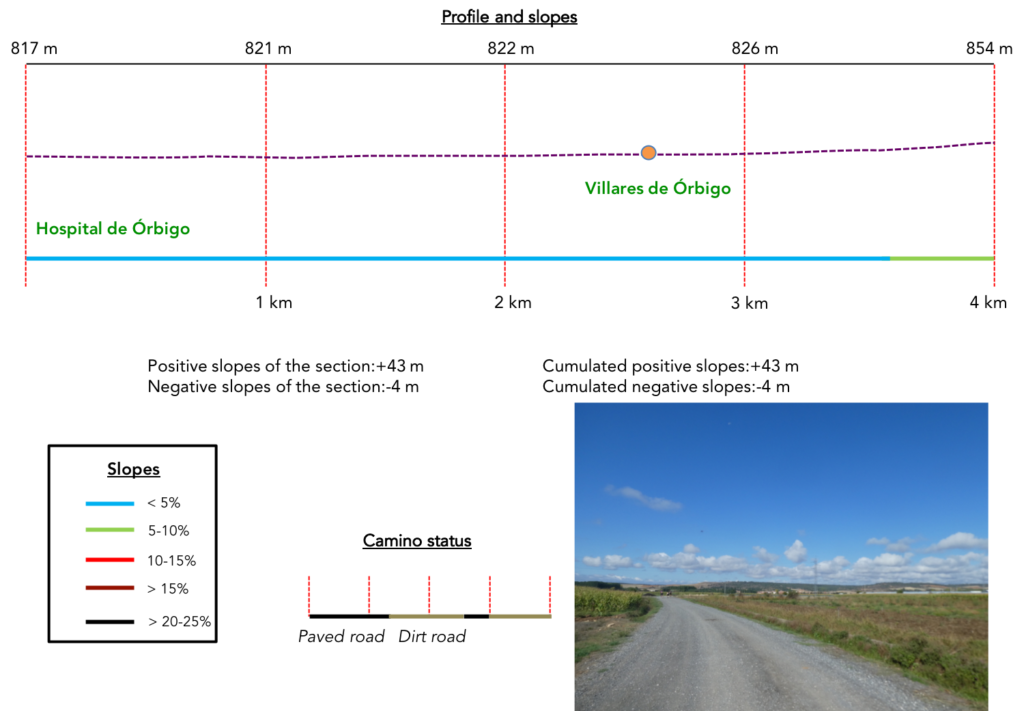

Section 1: In corn and vegetables.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| The Camino leaves the village of Hospital de Órbigo along the long Calle Mayor. |

|

|

| At the end of the village there is the possibility of following the N-120 road again. But, the pilgrims, who walked the day before along this route, are saturated with it. Today they will not go. Moreover, the signs at the exit of the village no longer offer this route. The Camino will therefore rather flatten in the surrounding fields. |

|

|

| It runs on a wide artery of gray dirt, gravel. What a surprise! There is still corn today. |

|

|

| There is corn, of course, but the route is less austere than the day before for the pilgrims who followed the Calzada de Los Peregrinos. It is no longer straight, daunting. And, then, you see hills, which changes the game. |

|

|

| You also note that the number of pilgrims has increased on the way. Many pilgrims start the Camino in León. They get there by train. From here, when you walk on the route, you can estimate that there are probably 500 pilgrims a day, even if no one has ever come to count them, as far as we know. We do not understand why the organizers of the Camino francés do not make punctual counts on the route to improve their false statistics which only consider the pilgrims who stamp their “credencial”. |

|

|

| Along the road flow the small irrigation canals, so frequent in the country. |

|

|

| Further on, cultures diversify. A lot of cabbage is planted in the region, and sometimes leeks as well. |

|

|

| The road gradually approaches Villares de Órbigo, in the market gardens. |

|

|

| Further on, it crosses a plantation of young poplars… |

|

|

| …to enter the village, a place made of fairly simple houses, often colored or in bare brick. |

|

|

| These villages are largely devoted to pilgrims. There are crowds here, often in the morning. Many “albergues” do not serve breakfast. So, pilgrims flock to the buffet at the first opportunity. There used to be a hospital here for pilgrims, which no longer exists. The church is a mixture of Romanesque and Baroque. Closed, of course. |

|

|

| As soon as you leave the center of the village, there is no one left, except for a few pilgrims who are progressing. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino quickly finds a pathway that climbs into nature. |

|

|

| The pathway leads to a grove above the village. |

|

|

| In the undergrowth many varieties of oak grow, largely unknown to pilgrims who have traveled the Camino de Compostela in France. In France, these are mainly large pedunculate and sessile oaks or small downy oaks. Rates are the holm oaks. But, there are more than 500 species of oak trees in the world. In Spain, there are also large oaks, but many holm oaks, called here encinas. But, in addition, other varieties also grow, as here, which only a specialist’s opinion can assess. It is not enough to look at the leaves, because they are not all serrated as we are used to seeing running oaks. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a picnic spot nestles under the trees. You can even use the barbecue. But, in general, pilgrims do not love these places. They prefer to crowd into village bars. |

|

|

There is also a source of drinking water. Here again, Spain is making a special effort in this direction, which is not the case for the other Caminos de Santiago in Europe.

| The pathway then slopes down gently in a beautiful moor. It’s magic here. |

|

|

| The stony ground is of a beautiful ochre, the wild nature at will. It is still more relaxing than the cornfields of the previous days. You feel alive again, loving the Spanish way again. |

|

|

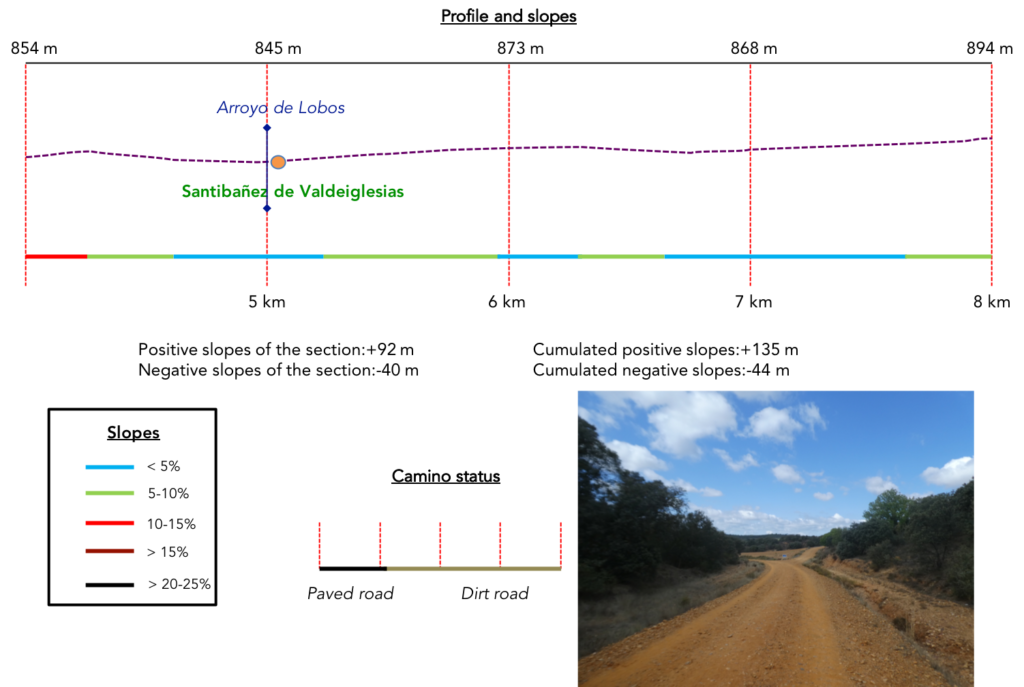

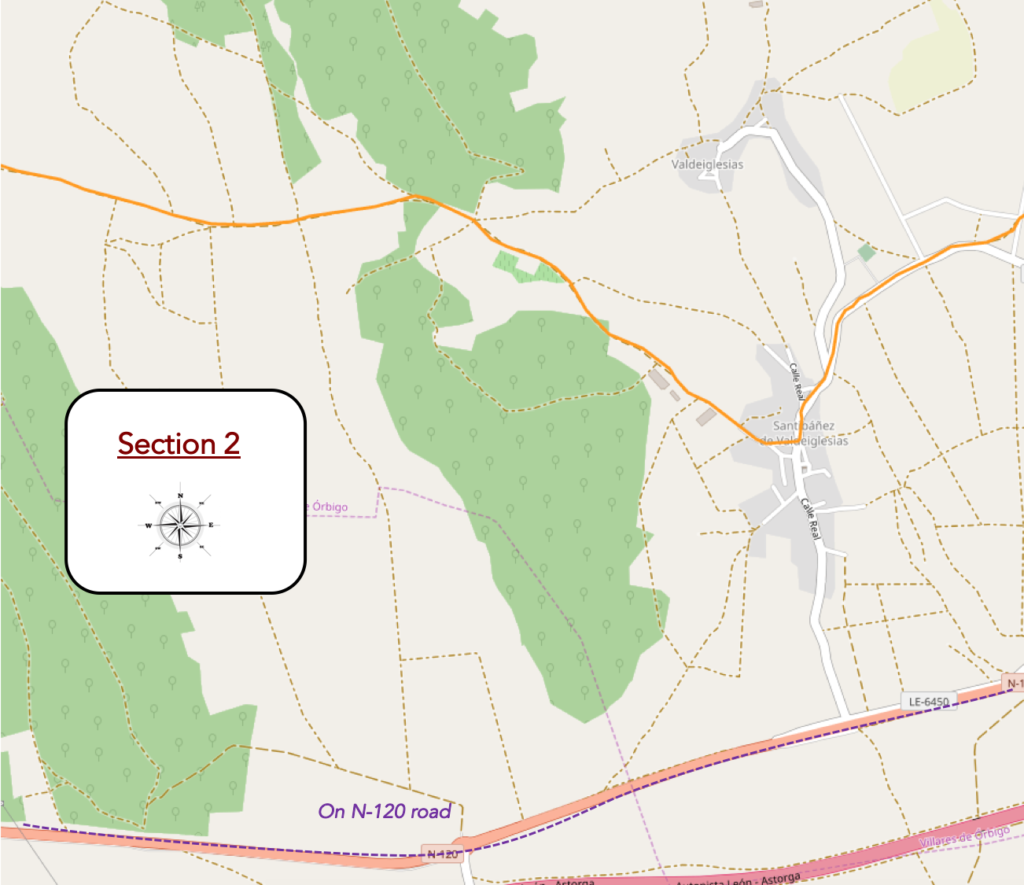

Section 2: Over hill and dale in beautiful nature.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course with more marked slopes, from one hill to another.

| Further on, the wide ocher pathway joins a paved road. They could probably have continued the track straight, but the organizers thought that it would be more profitable to give the pilgrims a little exercise. |

|

|

| Therefore, the pathway climbs on a bare hill, even if you sometimes guess some crops on the slope. |

|

|

| The climb is tough, but not very long. |

|

|

You catch your breath higher. So, you take advantage, even if you are neither hungry nor thirsty, to get stamped in a temporary bar the essential “credencial” which will give you the sesame to obtain the certificate of the Way of Compostela in Santiago.

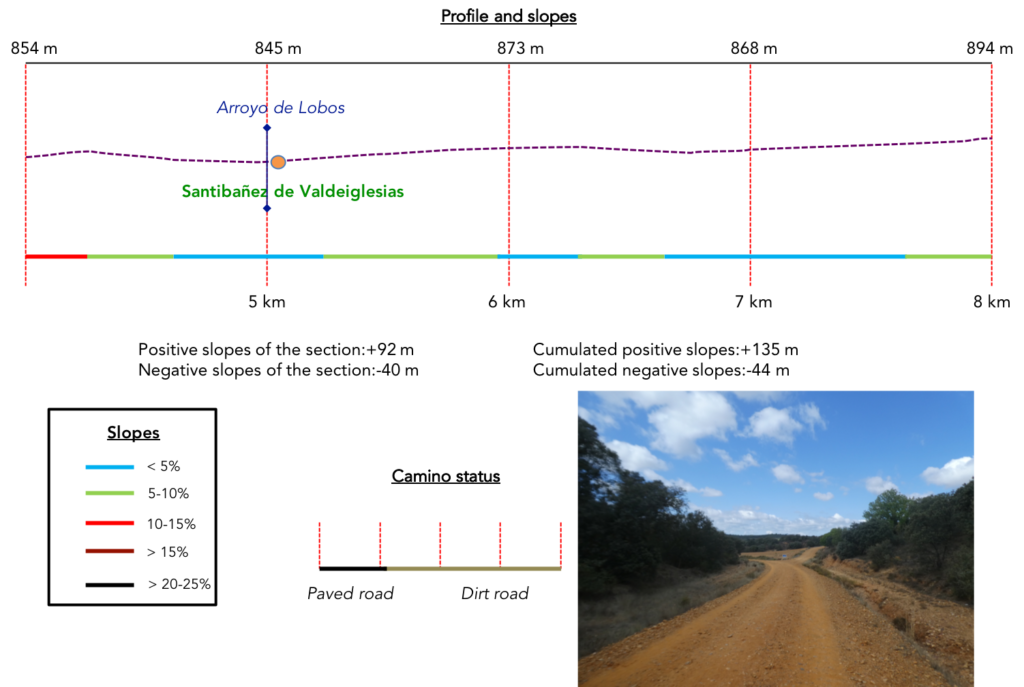

| Beyond the hill, the ocher and stony pathway descends, parallel to the bad asphalt road towards Santibañez de Valdeiglesias. Santibañez is the name of many places referring to Saint John. Valdeiglesias means “valley of churches”. |

> > |

|

| At the entrance to the village, the road crosses the discreet Lobos stream. This is where you enter the land of Maragateria, of which Astorga is the capital. |

|

|

| The village here is indistinguishable from the others, with low houses plastered or built of exposed brick. |

|

|

| Although the name of the village evokes St Jean, here the church is called Churh de la Tinidad. The church, like many others in the area, has a bell tower with a porch to the rear, which may have served as a gazebo. It is closed, as usual. |

|

|

| Watch out here! If you take the idea of going to visit the church, you will be tempted to continue straight, even if there are signs of a route that allows you to reach the variant on the N-120 road. Don’t do it, because in the middle of the village, before the church the Camino leaves the village to slope up above. |

|

|

| Leaving the village, the dirt replaces the tar. |

|

|

| Here, nature exudes the scent of the countryside, livestock and manure heaps. Considering the Holsteins, you know that it is the milk, and not the meat, that the peasants favor here. It is one of the rare times that you’ll find this context from Navarre, which is now far behind you. |

|

|

| urther ahead, the pathway climbs up the hill. The slope is not steep, but the stony state of the pathway sometimes hinders walking. |

|

|

| Your gaze embraces a hill as vast as it is wild. The colors and sounds produced by your soles crunching on the small rolling stones respond to each other. |

|

|

| Sometimes the pathway is so disproportionate that you could imagine yourself on a ski slope in the Alps, after the snow has melted. |

|

|

| Anyway, cyclists seem to appreciate this kind of giant slide. |

|

|

At the top of the climb, near a cross and a pilgrim as a scarecrow, the Americans hold a meeting. Koreans, so prone to family photography, have vanished into space. Perhaps they prefer to come here in the spring, when they make the number.

| Beyond the hill, the wide pathway descends gently towards a vast plain in the middle of oaks lost in nature, in the embankments covered with clumps of bushes that look like broom but are not. |

|

|

| It is a suspended moment, beautiful as a postcard filled with tenderness. |

|

|

The rain must often gully down the sides of the valley, which gather in iron red moraines.

| Further on, the Camino slumbers a little at the bottom of the vast plain. |

|

|

Here, there are hardly any cultures. The ground is ungrateful. It is only moorland with short grass and a mess of bushes that delight in it.

| Further afield, the pathway begins to climb again on another hill. |

|

|

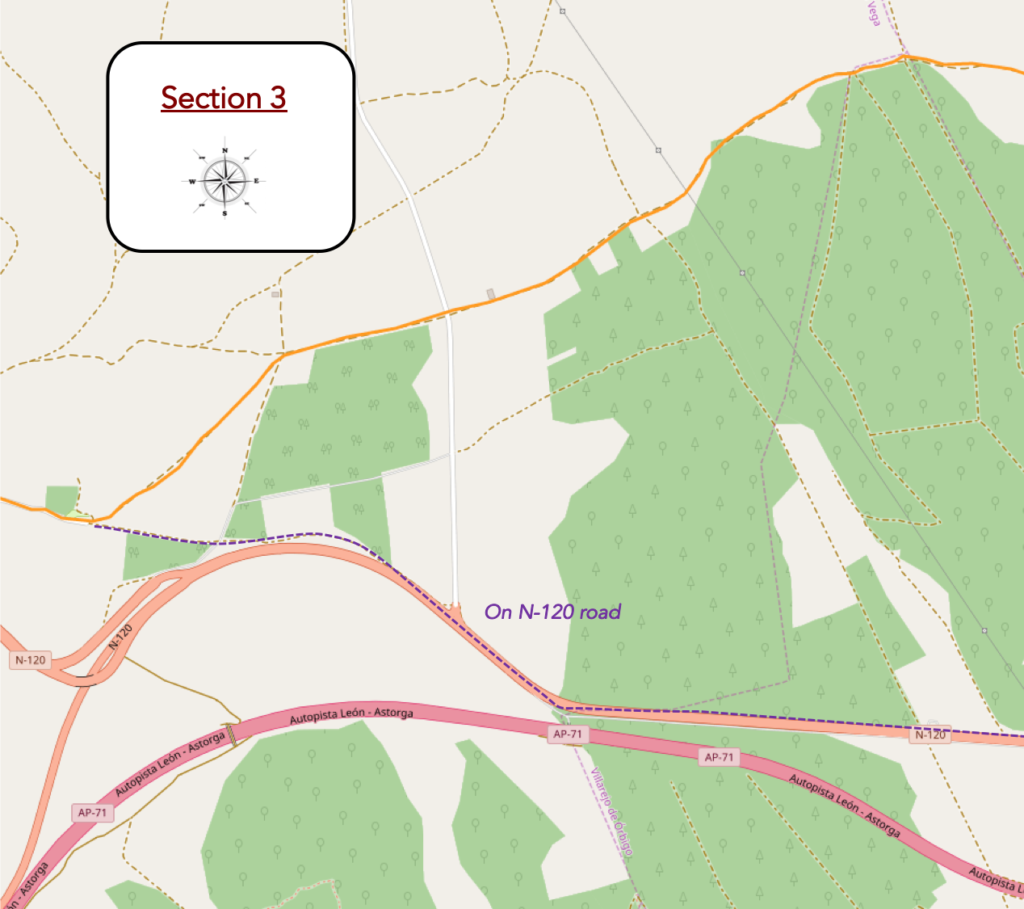

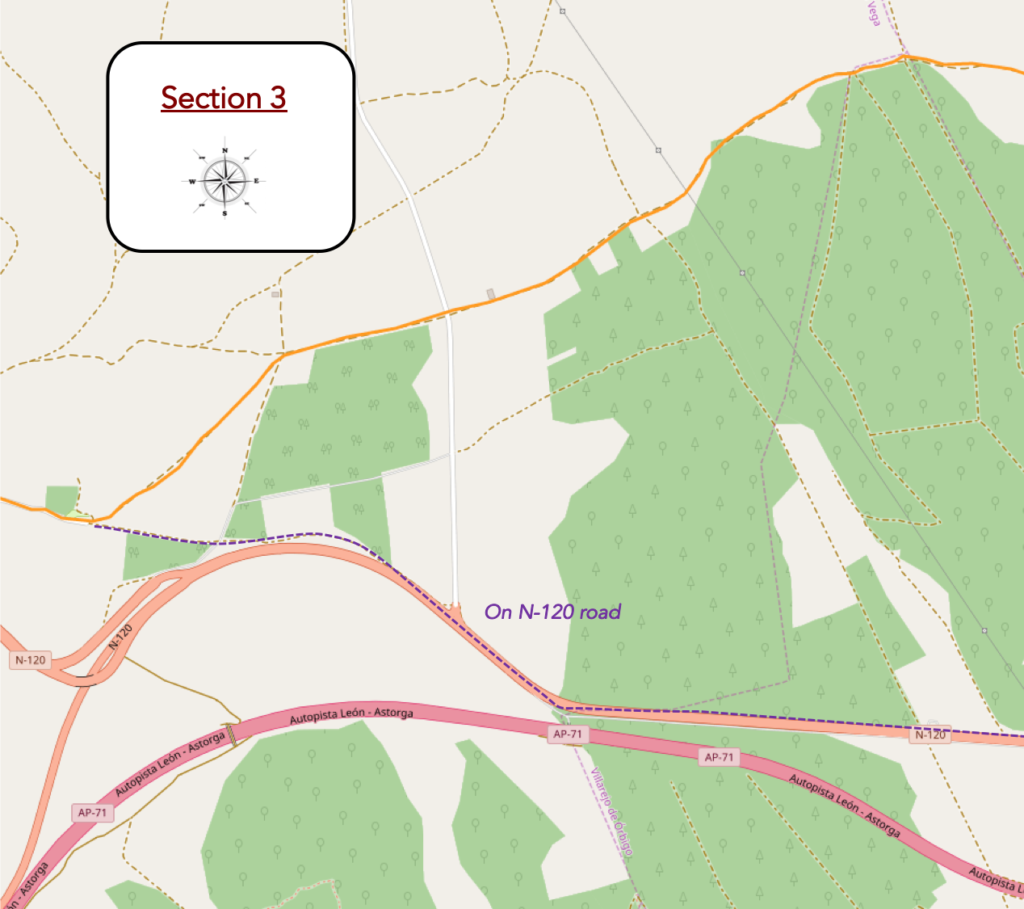

Section 3: Oaks and pines aplenty on the ocher ground.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course with sometimes marked slopes.

| The slope becomes steeper as you slope up. |

|

|

| On this ocher highway, the oaks offer a beautiful contrast. There are, so to speak, only oaks capable of growing on this ungrateful land. |

|

|

| Pilgrims catch their breath on a high plateau, where you wonder what could grow in season among the stones. |

|

|

| Further on, the stony pathway bumps and wobbles between fields and oaks. |

|

|

Sometimes the pathway is almost a real scree. The fields too. What the hell can you grow on it?

| Sometimes, nature is more generous and the stones have flown away. |

|

|

| Further on, the stones return, and the pathway sinks into a small dale in the chlorophyll of the oaks. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the dale, you can see the cultivated fields lined up in front of you again. |

|

|

| But, as is often the rule on the Camino de Compostela, every descent is generally followed by a climb. Then, the wide stony pathway slopes up between the fields on one side, the moor on the other, with its bushes and its oaks. The slope is quite substantial here. |

|

|

| But every effort deserves sometimes pay, because at the top of the climb an oasis arises like in the desert. |

|

|

| The locals do not lose the north, unlike the pilgrims who generally do not know where the north is. A small road arrives here, and so do the drinks and food. It’s a real bazaar, with all possible refreshments, fruits, nuts, olives. These temporary bars are taken over, as if it were heaven after hell. In these places, as usual, the Americans are the kings of the ball. |

|

|

| Beyond the bar, the pathway heads towards the forest. |

|

|

| Here, a royal, magical alley awaits you, in the middle of the pines. |

|

< |

| At the end of the alley, the pathway opens onto a wide plateau. |

|

|

| It is a moorland of formidable beauty, a lost open-air paradise. |

|

|

| The wide ocher pathway strolls with delight in this little world of stunted pines and stunted oaks. |

|

|

Then, at the end of this paradise, stands before you the Cross of Santo Toribio, commemorating the flight of the saint, bishop of Astorga in the Vth century. He would have fallen to his knees here in a final farewell, after being banished from the city. From here there are wonderful views of the town of San Justo de la Vega and the town of Astorga with its twin cathedral towers further in the distance. Visible beyond Astorga are the Montes de León, which you will cross in the days to come.

But, if you think you are reaching the goal, think again. Astorga is still almost 5 kilometers from here.

| The slope is steep to reach the plain below. |

|

|

| You can, as you wish, follow the pavement or the dirt, in the shade of the ash and maple trees. |

|

|

| Almost at the bottom of the descent, the Camino joins the road, where stands the statue of a thirsty pilgrim. The bronze statue is by a local painter and sculptor, inaugurated in 2014. When you press the button on the top of the fire hydrant, water flows from the Pilgrim’s Gourd. |

|

|

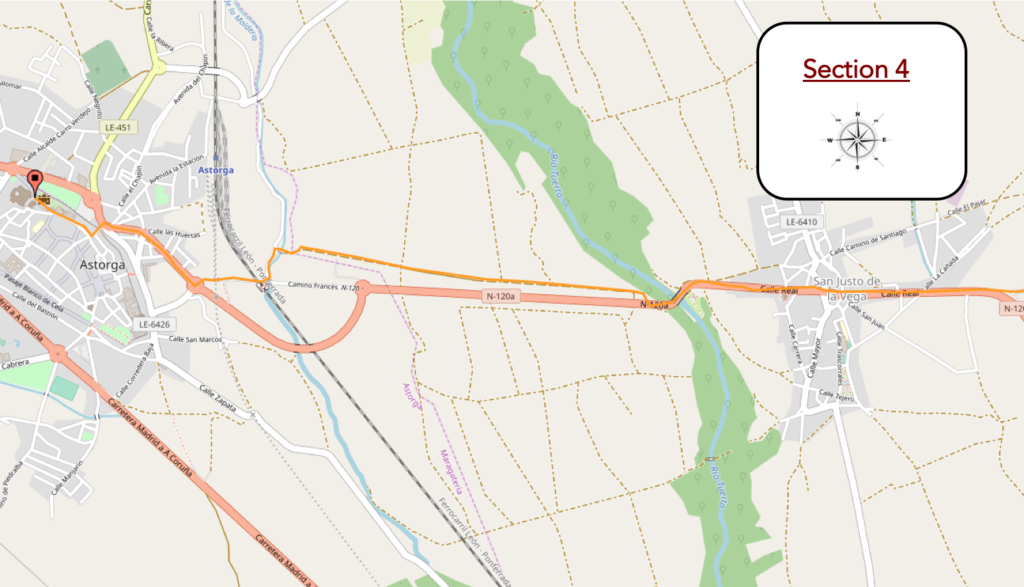

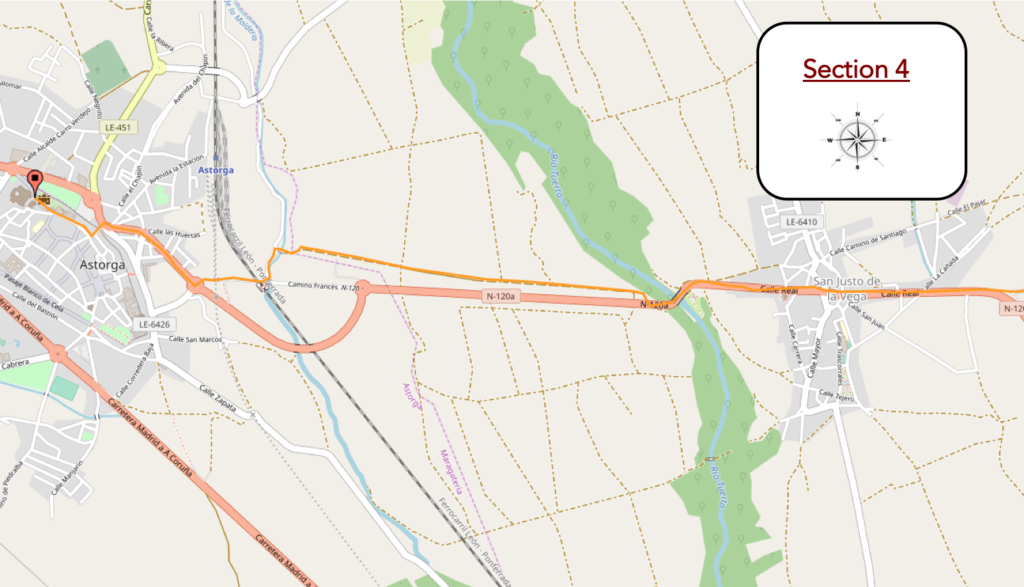

Section 4: A long road to get to Astorga.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Further down, the Camino joins the N-120 road. Here comes the variant that follows the N-120 road, which few pilgrims use today. |

|

|

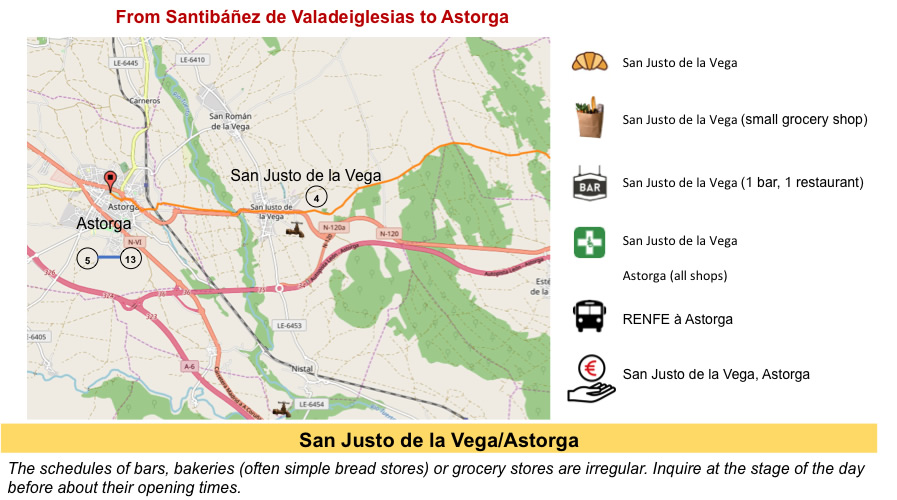

| The Camino then crosses the length of the village of San Justo de la Vega, where we find the type of construction observed in all the villages of the region. These villages are rarely wealthy. There was also a hospice here for pilgrims in the Middle Ages, but no trace of it remains today. The brothers Saint Justo and Saint Pastor are venerated as Christian martyrs. They were two school children who were killed for their faith during the persecution of Christians by Roman Emperor Diocletian. Having refused to denounce Christianity, they were beheaded near Madrid. According to tradition, they were nephews of Santa Marta de Astorga. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, it is a sidewalk that leads you along the road towards the river. |

|

|

| Then, the road crosses the Rio Tuerto, a beautiful and calm river under the trees. |

|

|

| Further, it is again a short journey on the N-120 road, before finding a side road. |

|

|

| It is a nice dirt road, under oaks and poplars, which takes you to the outskirts of Astorga. |

|

|

| Further on, it reaches a factory near tired sunflowers. |

|

|

| It is then a loving dialogue with the walls of the factory, an idyll that has difficulty in ending. |

|

|

Further on, under the lime trees, you will see the towers of the Cathedral of Astorga. They seem to you within reach. Think again. You are still far from the goal.

| Because the towers will disappear from your sight. All this to admire, after a small stone bridge, the Moldeira stream, which hops in the wild grass. |

|

|

| The route runs around the stream to arrive in front of a curious labyrinth. |

|

|

| This roller coaster, on which you go up, down, to go up and down again, is just there to cross the track of a regional train. There is money in Astorga. |

|

|

| We told you, the approach to the city is long. The Camino still turns for a long time in the suburbs, from one roundabout to another… |

|

|

…to reach the foot of the city. It is the ancient Asturica Augusta, a regional capital in Roman times.

| But there! The old town is on the promontory and you will have to climb up there. |

|

|

Section 5: Astorga, an open-air museum.

A Roman wall surrounded the old town of Asturica Augusta. The first defensive wall, built in 15 BC corresponded to the borders of the camp of the Legio X Gemina. As it was built of perishable wood and adobe mud, it was demolished and erected in stone, becoming the first surrounding wall of the urban core. Very little of this wall remains. Finally, the third wall was built between the 2nd and IVth centuries. This last wall built by the Romans is what is visible today, although many renovations and restorations were made in medieval times. It is 2.2 km long, between 4 and 5 m thick, and surrounds the hill on which the old town is located. The wall remained intact until the XIXth century, largely because the city had not gone beyond the fortified wall. In 1808, during the War of Independence, French and Spanish troops caused significant damage. These walls are of a rather impressive height, in places very well preserved, especially around the castle and the cathedral. Of the original wall, part of a Roman gate remains.

Here is a map of the old town. The cathedral is on the opposite side of the city, when you enter it by the Camino de Santiago.

| Astorga (12,000 inhabitants) is quite a magical place, an open-air museum, which houses a fairly unequaled historical and cultural heritage. When you enter the old town by the southern entrance of Puerta Sol on a steep road, you pass the major seminary, a building as large as it is austere. |

|

|

| You’ll arrive at San Francesco Square. The bronze statue, “Quo Vadis El Caminante” (Where are you going, walker?) dates from 2011. We also owe it to the sculptor Garcia Ramos (also known as “Sendo”), a native of San Justo de la Vega, who also carved the thirsty pilgrim. |

|

|

In the square stands the Convent of San Francesco. It is said that Saint Francis of Assisi, during his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, would have spent the night in the city without being recognized, except by the bishop of Astorga, who proposed to found a convent in his honor. Do you believe this legend? Still, the convent was founded in the XIIIth century, although the building today dates from the XVIIth century. This convent belongs to the Redemptorist Fathers and preserves Gothic vestiges in its church. Often, pilgrims flock there to have their “credential” stamped. But you still have to go to opening hours.

The convent forms a unit with the adjoining La Chapelle de Veracruz. It is the seat of the brotherhood of the Vera Cruz (True Cross). It is here that the floats of the Holy Week processions, so dear to the Spaniards, are kept.

| The origin of Astorga dates back to the 1st century BC when a Roman military camp settled here on the hill. Of the Roman presence of more than four hundred years, there remain many vestiges, including these excavations next to the monastery of San Francesco, and remains of tombstones, coins or pottery collected in the Roman museum, not far from here, in a modern gray building with narrow windows. |

|

|

| Very close to the Roman square, there are two more churches. The first is the sanctuary of the Virgin of Fatima, close to the wall that surrounds the city. This small church, which dates from the XIIth century, was for a long time a parish. In the middle of the XXth century, it was restored and changed its name to Our Lady of Fatima. This sanctuary is a World Heritage Site as part of the Camino de Santiago. The other church, near the Roman Museum, is the Church of San Bartolomeo. It is the oldest church in the city, built at the end of the XIth century in the Romanesque style. Subsequent interventions resulted in an amalgamation of styles from different eras. There are vestiges of the primitive construction of Mozarbic, Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque and other interventions. The tower dates from the XIIth century, although its summit is later, the portal and the rose window which overhangs it from the XIVth century and the transept from the XVIth century. Successive reforms gave the facade the feeling of breaking symmetry. |

|

|

| Wikipedia Creative Commons ; author Rodelar |

Wikipedia Creative Commons ; author Rodelar |

| Shortly beyond the Roman Museum, you will come to the Plaza Mayor. Located on the ancient Roman forum of the city, it has been the epicenter and the nerve center of the city for more than two thousand years. At the back of the square stands the Town Hall (Ayuntamiento), with its XVIIth century Baroque facade, its pinnacles, and the automaton clock that strikes the hours. In the evening, it is crowded with pilgrims and locals sipping aperitifs, before having lunch on the many terraces. In Spain, we usually sit down to eat after 8 o’clock in the evening. |

|

|

| Every Tuesday, and since medieval times, the square has become an open-air market. Astorga is the capital of this region of Castilla y León, called the Maragateria. Historically, the term maragato refers to merchants, primarily muleteers. It is estimated that since the Middle Ages the muleteers represented 20% of the population of this region. These people, very powerful, devoted themselves to breeding, fishing, selling and transporting food in the country. They disappeared at the beginning of the XXth century with the arrival of the railway. But many maragatos have since settled in Galicia, and even in Madrid, where sometimes they still hold food monopolies.

So here, in the Plaza Mayor, or in Astorga, and still in the surrounding area, the maragata signs are flourishing. The cocido maragato is the star of the local gastronomy. It’s actually a stew, with chickpeas, beef, pork and chicken. But it is a complete meal, with soup and dessert. What distinguishes the cocido maragato from other cocidos is that you eat the meat first, then the chickpeas, then the soup and finally the dessert. Enjoy your food and good luck, because it’s heavy to digest. |

|

|

| Beyond the Plaza Mayor, you reach the cathedral by small alleys or by the main roads. You will come across many chocolate shops. Contrary to popular belief, chocolate was not born in Switzerland or Belgium. Astorga is the European cradle of chocolate. In 1528, explorer Hernán Cortés brought Mexican cocoa beans to Spain. Chocolate became popular here in the XVIIth century. In 1919 there were 49 chocolate makers in the city. |

|

|

| On the cathedral square, two imposing buildings stand out, first of all the majestic cathedral, but also the episcopal palace, designed by Gaudi. Despite its name, it has never hosted bishops. During the Spanish Civil War, it served as the barracks and headquarters of General Franco’s Falange party, during which time there was considerable damage, especially to the windows. Architects repaired everything to convert it in 1963 into a museum. |

|

|

It is a modernist style building; a modern Catalan style of which Gaudi is one of the pioneers. The palace was designed around the 1890s by Gaudi. It is one of the few important works by the master outside Catalonia, along with the palace built in Burgos, which you have already seen. The construction of this palace is a funny story. After the old episcopal palace was destroyed by fire in 1886, the bishop of Astorga entrusted the construction of a new palace to Gaudí, with whom he was a friend. At that time, Gaudi was busy with the Palazzo Güell project in Bacelone. Unable to go there, he documented the location of the new building, having photos sent to him. The project experienced some delays, because Gaudí had to obtain the approval of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. So, he modified his project twice. You know Gaudi. He was a free man, and he was deeply offended that his plans were changed. Nevertheless, after final revision of the project, the first stone was laid in 1889. In 1893, on the death of the bishop of Astorga, Gaudí entered into conflict with the episcopal authorities and abandoned the direction of the project, ulcerated by the constraints and late payment of his fees. He swore never to return to Astorga again. He left the palace unfinished, without the top floor and the roof. Other architects between 1905 and 1907 completed the work.

| Anyway, Gaudi is a disturbing genius, here as in Barcelona. You either love or hate the Sagrada Familia. But, it is true that here, the episcopal palace disturbs even more, because the building has no equivalent in the city, nor anywhere else in the world, to which it could be compared. To some, the Bishop’s Palace looks like a Disneyland setting. For little, you would expect to see Snow White appear on the porch.

But, you can also consider the building from another point of view. From afar, you can see a medieval castle. At the origin of the project, he had been sent photos, and he had seen an esplanade above the walls of the fortress. Of course, he was not going to redo a Sagrada Familia here. So, he probably decided on something else, paying homage to the city’s medieval past. He then employed the neo-Gothic style and combined in the palace two types of constructions evoking both the sword and the aspergillum. He therefore decided on the one hand for a castle with its moat, its battlements and its towers and on the other hand, a cross church, with apses and pointed arches. Moreover, when you enter the museum through the garden, behind the little angels, you can make out the moat and the battlements overlooking the high wall. |

|

|

| You enter the palace. Here, it’s a shock, it’s no longer a castle, but a church, where the vaults and ogival arches respond to each other on three floors, between granite, mosaics and red brick. It’s Gaudi, we like it or we don’t like it. |

|

|

| Here, you never know if you are in the church or in the bishop’s apartments. |

|

|

| After his first visit to Astorga, almost two years after the start of the project, Gaudí decided on a central core to generate a focus of light coming from the ceiling to illuminate the entire palace. He also had many multicolored stained-glass windows installed. So, by the staircase, you go from one floor to another and find the light each time. |

|

|

| On leaving the episcopal palace, the gaze is first and foremost directed towards the cathedral. Nearby stand two small churches. The Church of San Esteban (St. Stephen) is a simple structure with a single nave, built at the beginning of the XIVth century, transformed in the VIIth century, especially in the apse. The chapel was originally connected to a pilgrim hospital founded in the second half of the XIth century and collapsed at the end of the XVIIth century. The neo-classical façade dates from the XVIIIth century.

The Church of Santa Marta is more recent, from the XVIIIth century. It is dedicated to the patroness of Astorga, a 3rd century Christian martyr from the city. Santa Marta was the teacher of San Justo and San Pastor, the two child martyrs. The current Baroque church was preceded by at least two others, including a pre-Romanesque one from the VIIth century and from the Xth century, making it the oldest church in Astorga. Few traces of these churches remain. Its proximity to the cathedral made this church the “hijuela del Cabildo” (little sister of the cathedral chapter), that is to say, it was the parish of the cathedral and until the XIXth century, the parish priest had the title of rector and was a canon of the Cathedral. |

|

|

| https://madillcamino2014.blogspot.com/2015/10/new-thursday-september-11-2014-astorga.html |

https://madillcamino2014.blogspot.com/2015/10/new-thursday-september-11-2014-astorga.html |

The celebration of Easter with processions in Astorga dates back at least to the XVth century, supported by two brotherhoods (confradias) under the tutelage of the Franciscan and Benedictine monasteries, and flourished throughout the XVIIIth century. At the beginning of the XIXth century, however, much of the tradition died out. In 1908, at the suggestion of the Bishop of Astorga, the revival, reorganization, improvement and promotion of Easter and its Holy Week processions began again. In the XXth century, after the Spanish Civil War, a new impetus was given with the emergence of 8 new brotherhoods. The members of each group have robes of a particular color and wear an executioner’s hood. Obviously, you have to come here at Easter to enjoy the fervor and the spectacle.

| And then, there is above all the imposing Santa Maria cathedral, in pink sandstone, whose tower was rebuilt after the terrible earthquake in Lisbon in 1755, estimated at 9 on the Richter scale. It decimated Lisbon, northern Spain and the Maghreb, killing more than 100,000 people. It is a wonderful blend of late Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical styles. Its interior structure is essentially Gothic. It was built over the XIth century Romanesque cathedral and a second late Romanesque structure begun in the XIIIth century. It took its current form in the XVth century, retaining some parts of the Romanesque cathedral. The construction lasted nearly a century, mixing Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles. The main facade was started at the end of the XVIIth century in the Spanish Baroque style with three doors. |

|

|

| The main western facade marked the triumph of the Baroque of León. Completed at the beginning of the XVIIth century, it resembles a large Baroque stone altarpiece. It is articulated in imitation of the Gothic western façade of León Cathedral with three richly carved portals and flanked by two towers, which are connected to the central body by elegant gracefully carved buttresses. Both towers offer different shades ranging from green to pink. The facade is surmounted by turrets and pinnacles, as in León, but adapted to the Baroque style. In the central niche of the facade is an image of the Assumption. On the pediment just above this niche is an image of Santiago. Of the three front doors, the central portico takes up much more space. The arch is framed by columns, and under it is a vault with carved scenes from the Gospel. |

|

|

| The interior is divided into three very tall naves. Curiously, for a Spanish church, the interior is bare, sober, except for the high altar which gleams with gold and bronze. |

|

|

| The church also contains a cloister and a small museum of religious art, both of great sobriety. |

|

|

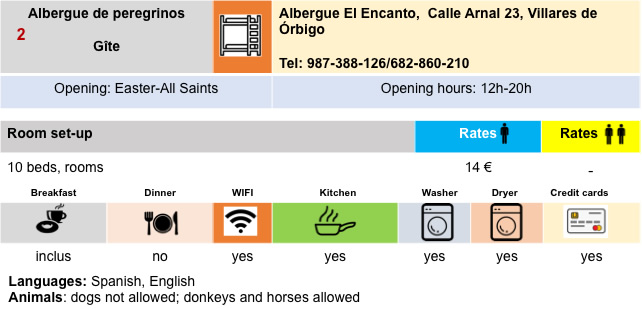

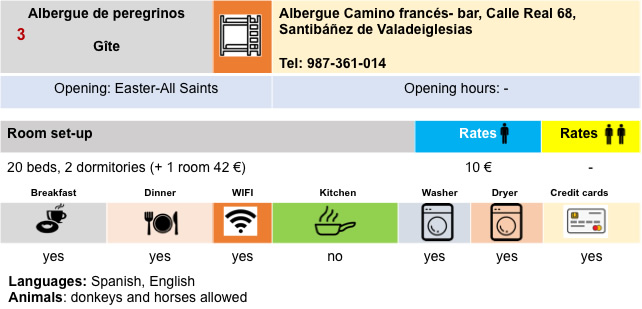

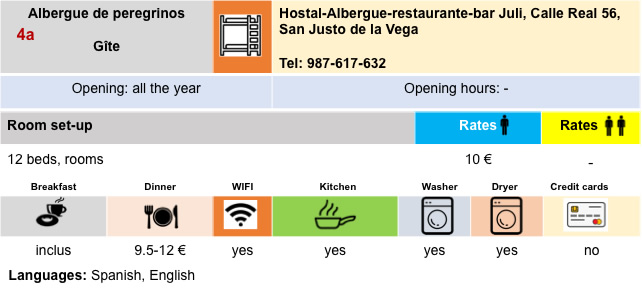

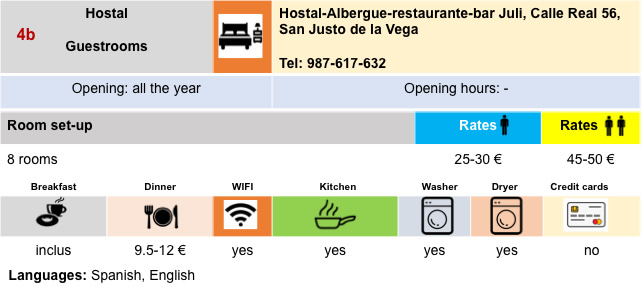

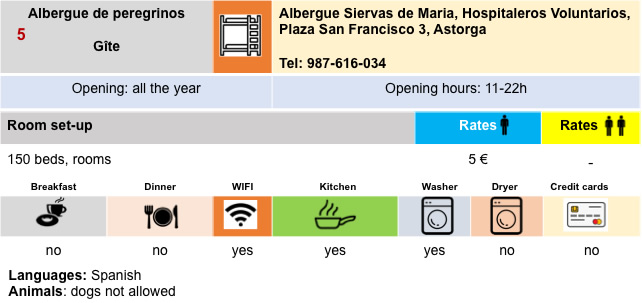

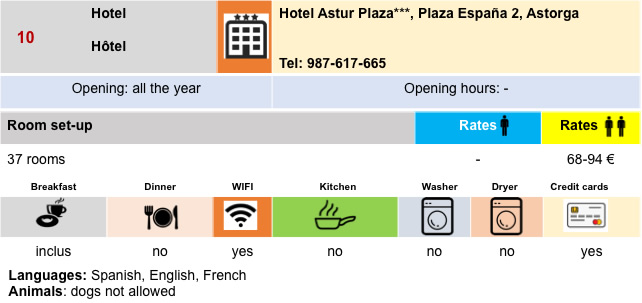

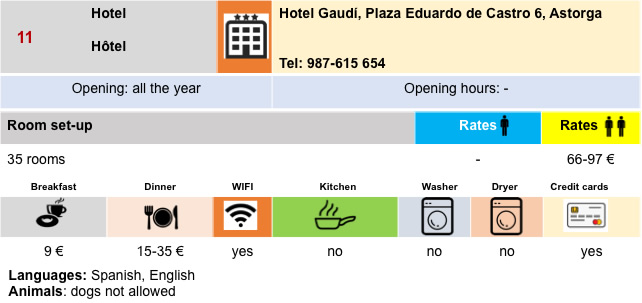

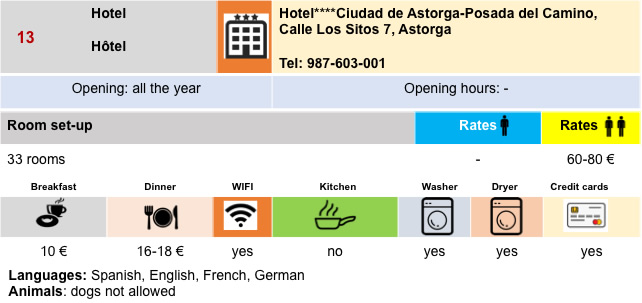

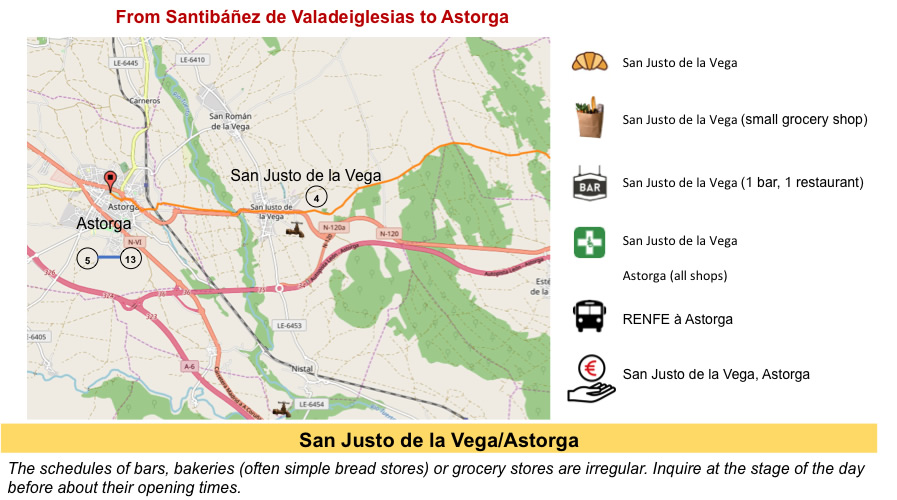

Housing

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 4: From Astorga to Rabanal del Camino |

|

|

Back to menu |

>

>