O Cebreiro, the other myth of the Camino francés with Ronceaux

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-villafranca-del-bierzo-a-ocebreiro-par-le-camino-frances-115061881

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Today our route is in Galicia (Galiza in the local language Galego), the last part of the trip. This part of the country is very hilly. The mountains of Galicia are the first obstacles that the westerly winds coming from the Atlantic hit. As a result, there are often frequent rain showers, thunderstorms, and even heavy fog here. Galicia is of Celtic origin. In mentalities and in geography, it is reminiscent of other Celtic lands, in particular the west of Ireland. Galicia is the greenest region in Spain. Galicia and its inhabitants retain many traces of the Celts, who arrived here from 800 to 600 BC, although the Romans gradually assimilated them in 137 BC. The name Galicia derives from the Latin Callaecia, which became later Gallaecia. It is the name of an ancient Celtic tribe that resided here and coexisted with the Romans for 3 centuries, the golden age of Celtic culture. The Romans called these people Gallaeci and later extended this name to all other tribes who spoke the same language and lived the same way of life. It must be said that the favorite traditional instrument of the Galicians remains the bagpipe, as in Brittany, Cornwall or Ireland.

In Galicia, ruined castros still survive, perched on the hills. In these fortified Celtic villages or settlements, the natives lived in pallozas, conical-shaped stone houses with thatched roofs. There are some beautiful specimens left in O Cebreiro, which you will reach at the end of the stage. The Galician population remains predominantly rural, the highest proportion of any European region. Isolated from the rest of Spain by a rampart of mountains to the east and south, Galicia remained relatively safe from Muslim influence. Galician culture showed a greater affinity for Portuguese culture than for that of Spain. All this is to tell you that the people here feel more Galician than Spanish.

Why has O Cebreiro become a myth? All this is linked to the imagination of the pilgrim. He knows nothing of the magic of the site that he learned in his readings or from the mouths of former pilgrims. So! All the guides talk about the difficulty of the exercise which some compare to the climb of Roncesvalles. On this point, it is not true. Only the last part of the climb is difficult. Previously, you have to swallow almost twenty almost tasteless kilometers along the highway or national road. The valley is deep (Valcarce comes from the Latin: Vallis Carceras, narrow valley) and very wooded. This valley reflects the struggle between León and Galicia. But, fortunately, the villages along the road are pleasant to see. Although the Camino does not officially enter Galicia until just before O Cebreiro, the atmosphere, topography, architecture and weather are above all Galician and not Castilian. It is only at the end of the stage, beyond the village of Hospital, that the sweat will gradually bead in a wild, sometimes bewitching nature. We can only wish you to pass here in good weather, and not in the current fog or drizzle, to enjoy the scrubland, the forests and some exceptional views of the Leonese Mountains. Then you will arrive at O Cebeiro, in this cradle of legends and striking rural architecture.

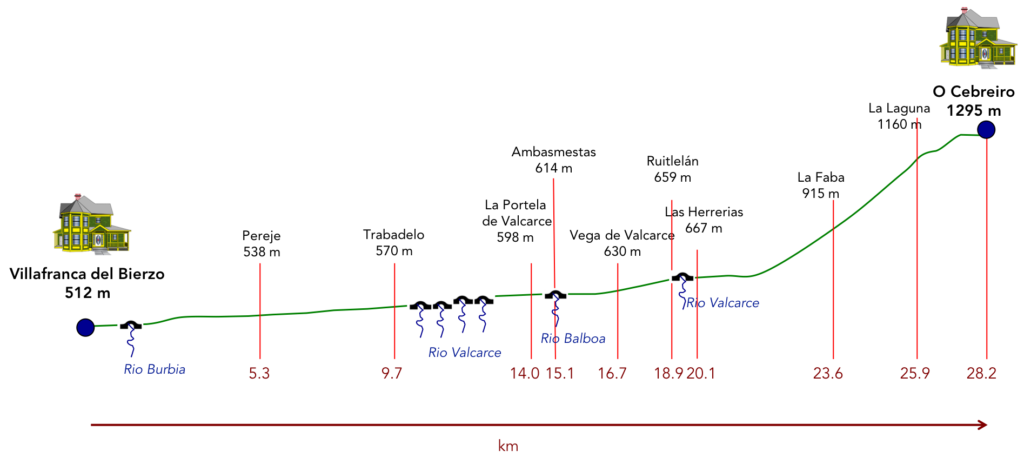

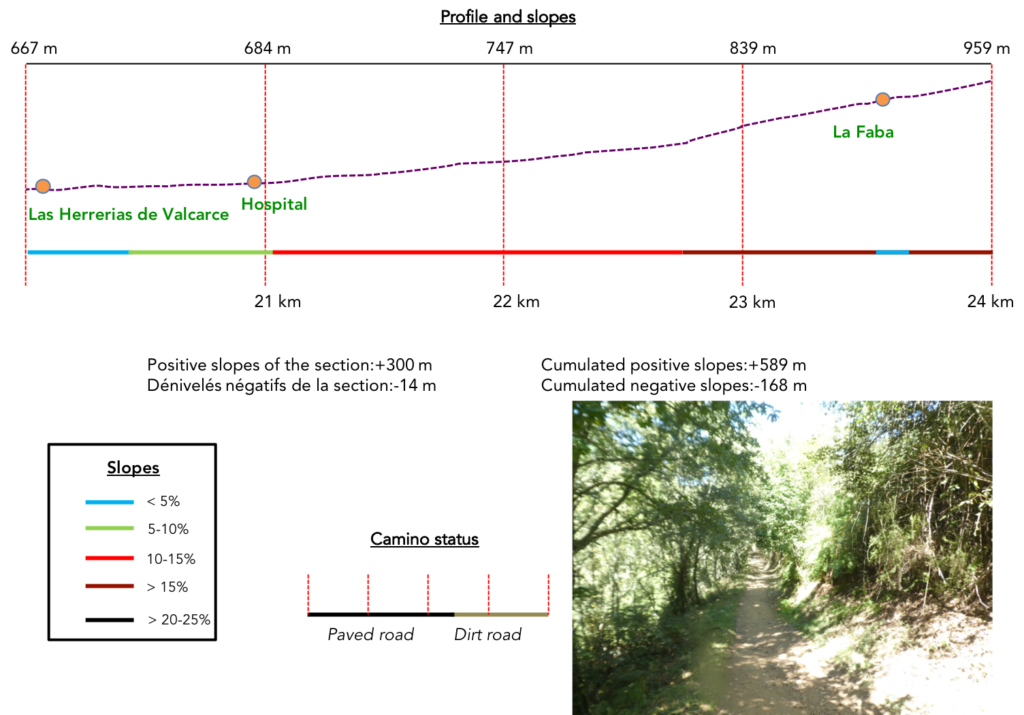

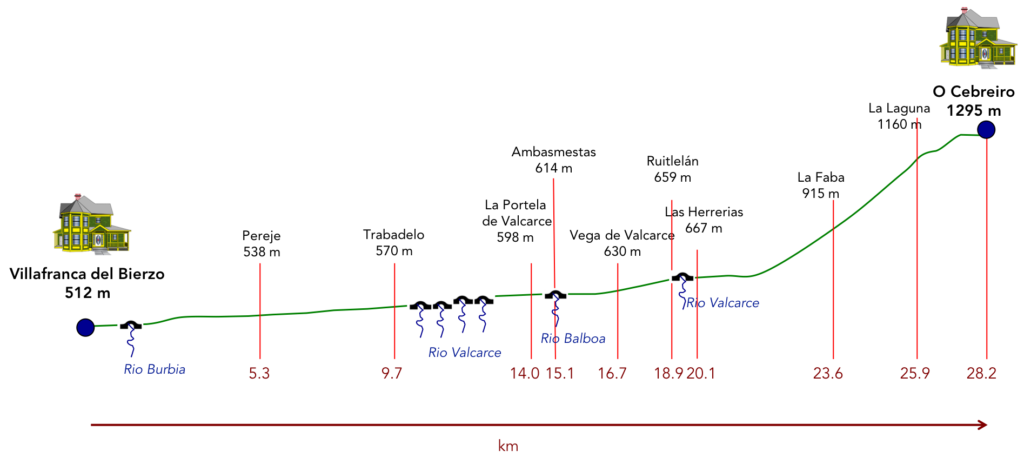

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+941 meters/-174 meters) are significant, which is not a surprise when the route heads towards a pass. You still have to pass the Montes de León. But, the slope is not marked for the first 21 kilometers to Hospital, being only 300 meters of elevation gain. It is from there that the course climbs toughly.

Today, the routes on the tarmac are very marked. It’s only the road to Hospital. Thereafter, it is the real pathway to climb to O Cebreiro:

- Paved roads: 22.4 km

- Dirt roads: 5.8 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

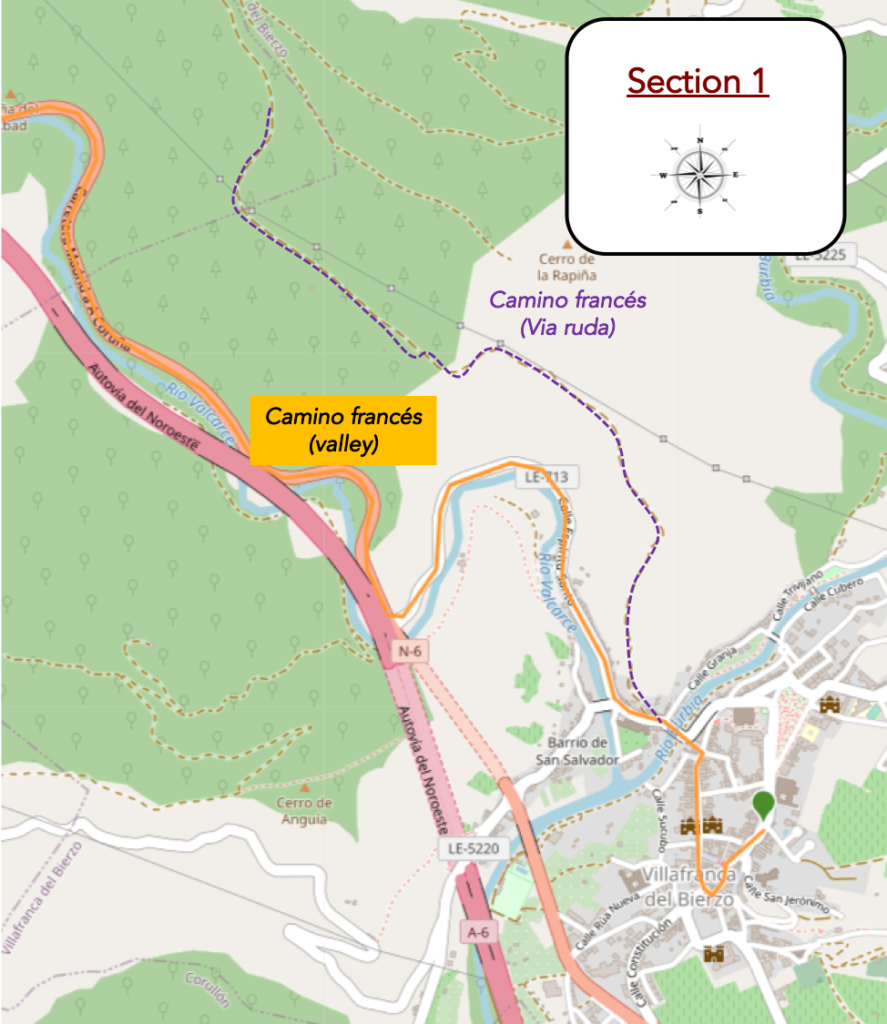

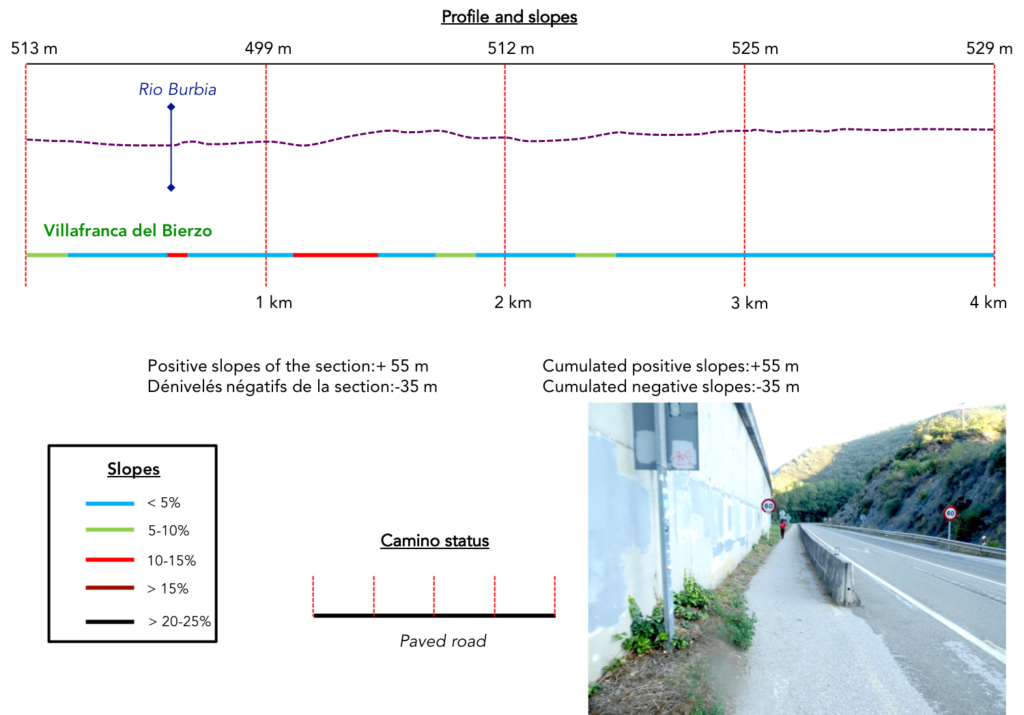

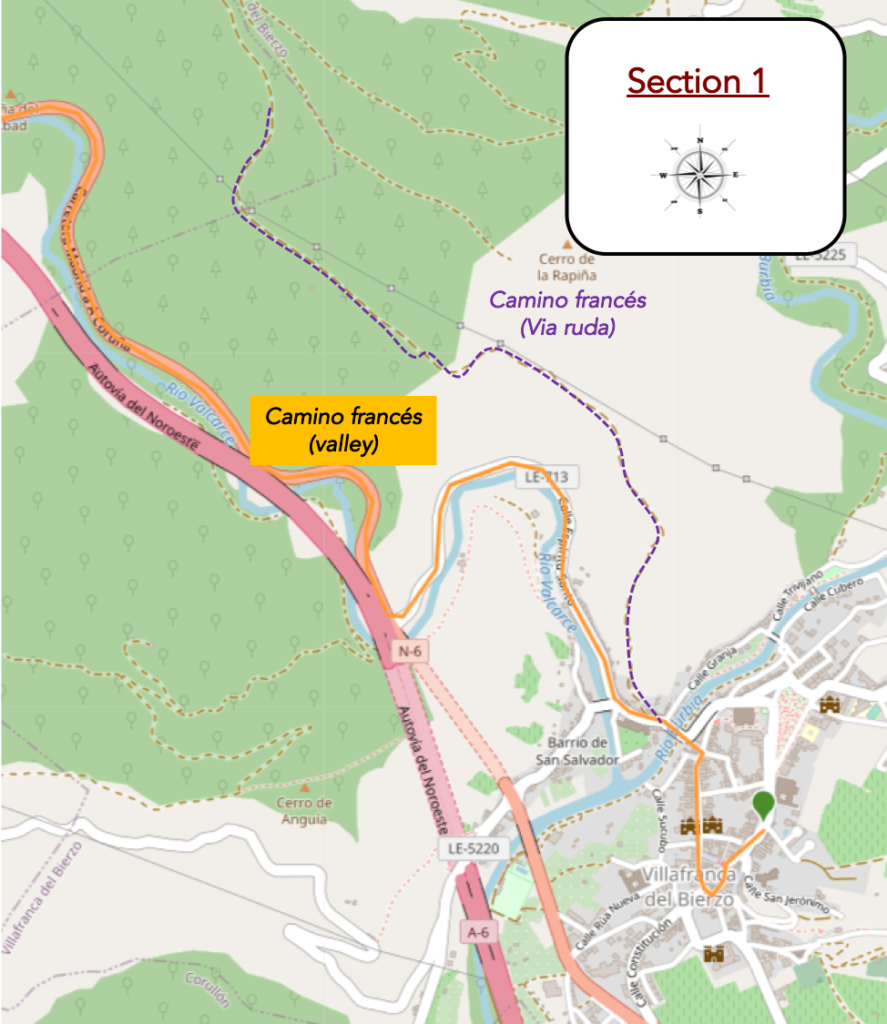

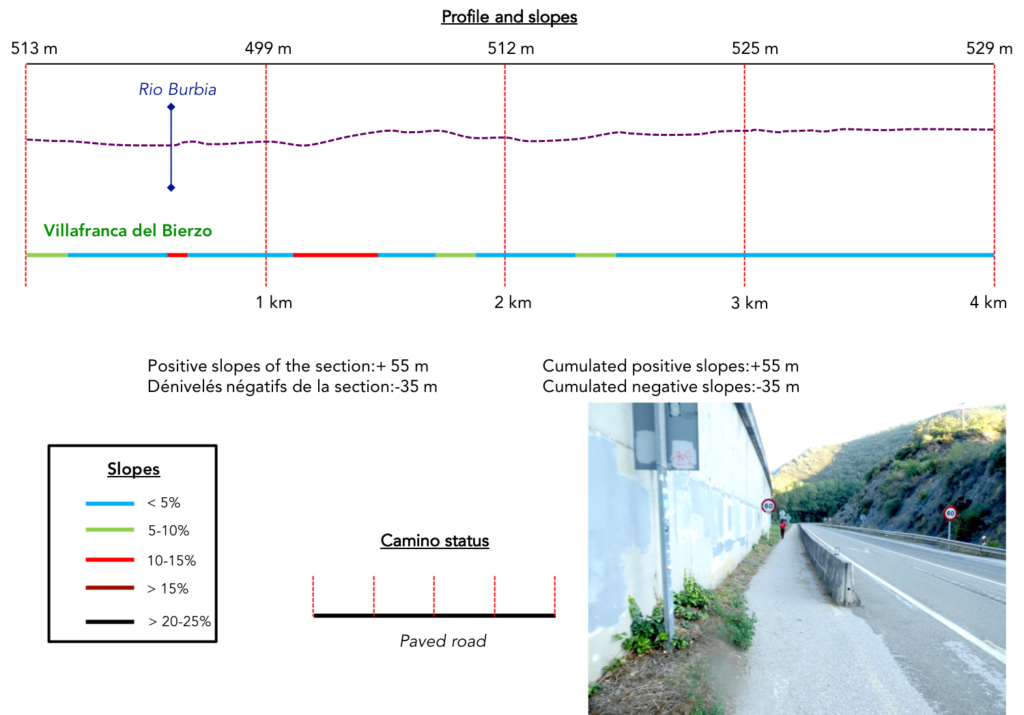

Section 1: Departure for a new “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without great difficulty.

| To leave Villafranca del Bierzo, follow Calle de Ribadeo from the city center down to the river. It is the most charming of the city; all bathed in an almost medieval atmosphere, with very present Compostela shells. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the street, the Camino heads to the large statue of St James and crosses the Rio Bubra. Today the weather is beautiful. There is even a ray of sunshine in the early morning. But, as the valley is steep, you will have to wait to leave the valley to see the sun again. And walk almost in the night in the gorge. |

|

|

| Here the Camino crosses the part of town on the other side of the river. Formerly, beyond Villafranca del Bierzo, there were at least 2 possible routes. In order not to confuse the pilgrims, there is no longer any clear indication for what is called the Camino francés (Via ruda), which as its name suggests is a more difficult route, running through the heights of the valley, before joining the Camino francés which only follows the valley. Today, few pilgrims, if not none, pass through the Via ruda. |

|

|

| Here, the Camino climbs following the valley along the Río Valcarce, which flows below into the Rio Bubra. The valley is steep-side, very narrow. Valcarce comes from the Latin Vallis Carceras, which means, “narrow valley”. And that’s true. |

|

|

| On the course, you learn that you have 185 kilometers left to go to Santiago. Here youwalk on the LE-173 road and the road makes a big hairpin following the river. You have to walk on the road, but the traffic is not frenzied, the motorway passing just a stone’s throw away. |

|

|

| Further up, the LE-173 road joins the N-6, the national road of the valley, which leaves Villafranca through a tunnel. |

|

|

| From here, a standoff with the N-6 road begins. And for a long time. And to make it even more postcard-perfect, the A-6 motorway, the Autovia del Nororeste, runs above, parallel to the N-6 road. |

|

|

| There are concrete barriers separating the paved pedestrian walkway from traffic. Since the completion of the A-6 motorway, there is less traffic on the N-6 road, but it remains a noisy thoroughfare. The positive point for us, because there is one, is the gradual arrival of the sun, which will make the pill less bitter. |

|

|

| Further up, the N-6 road deviates from the A-6, but the landscape hardly changes. The vegetation is quite dense in the valley, in oaks of all varieties, ash trees and everlasting black poplars. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the N-6 road returns and passes under the highway. |

|

|

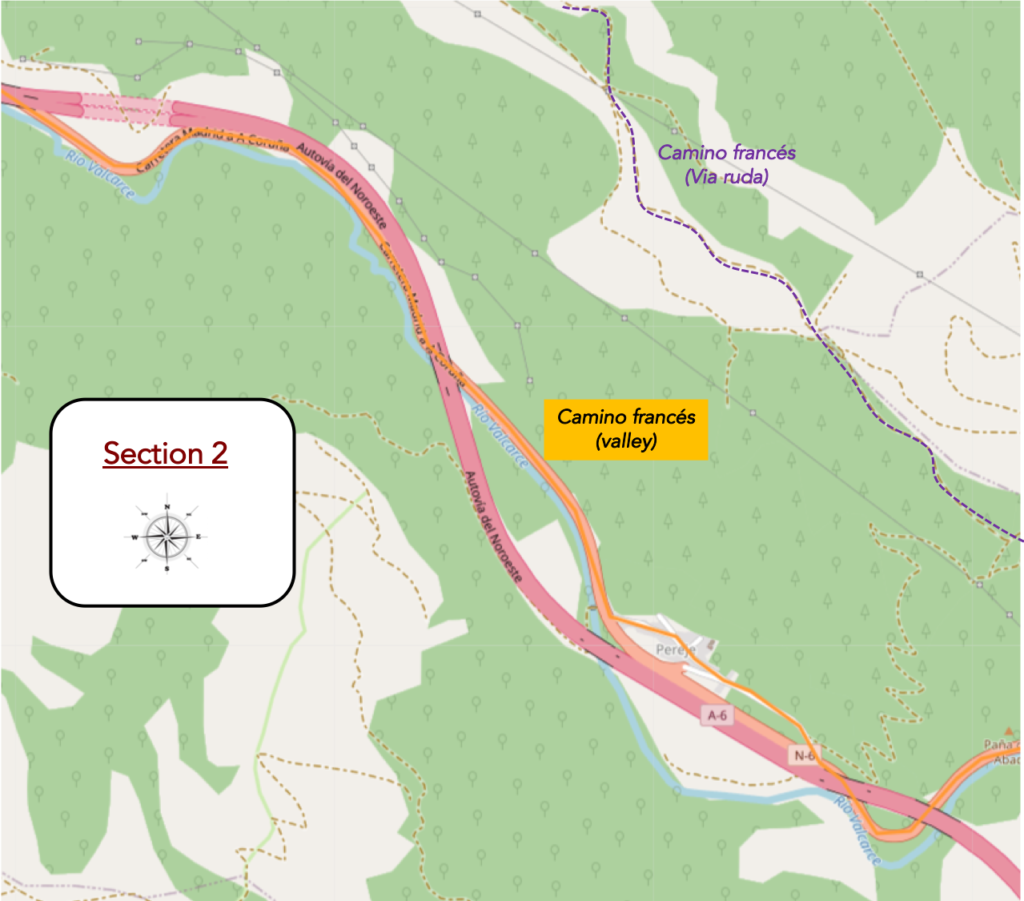

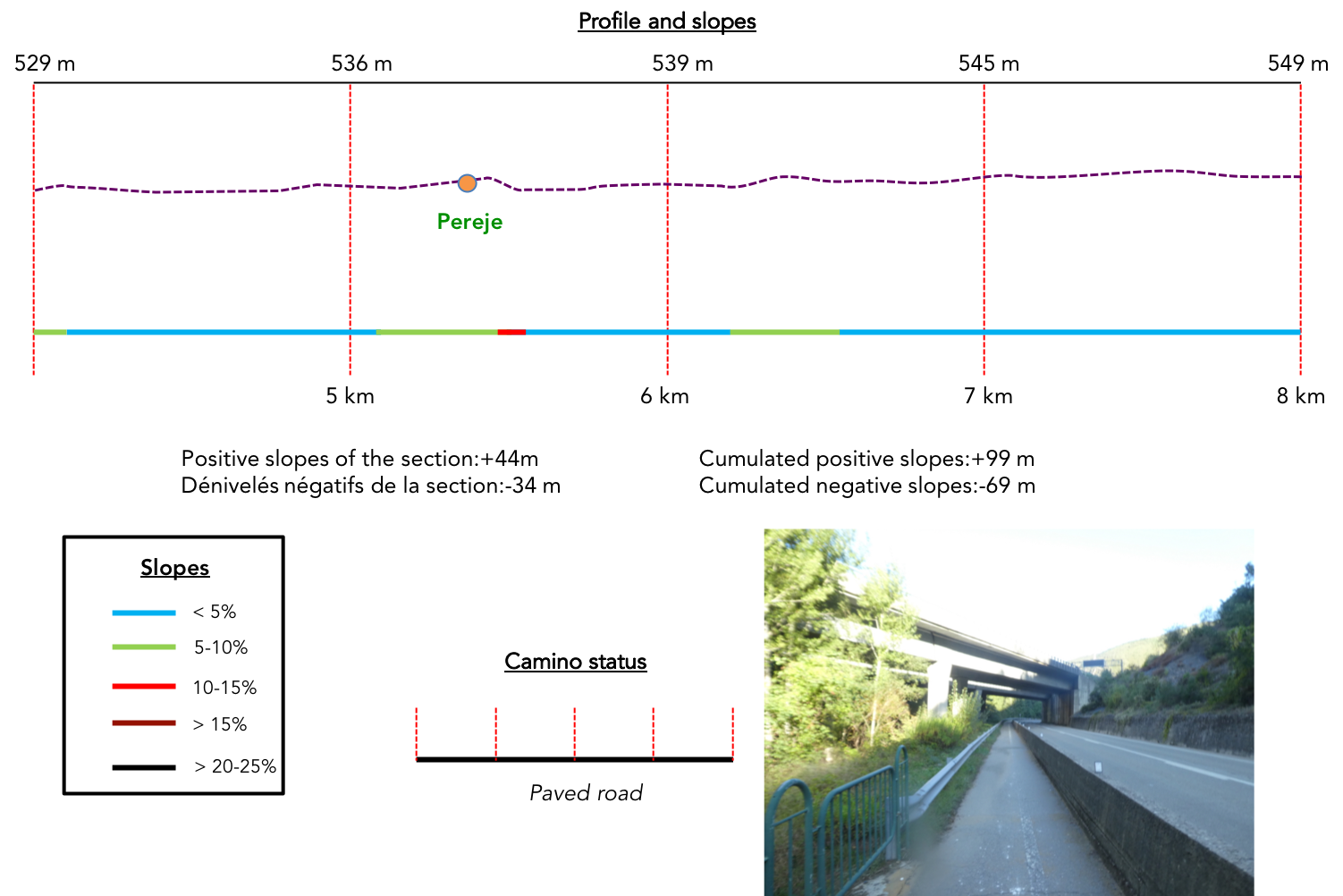

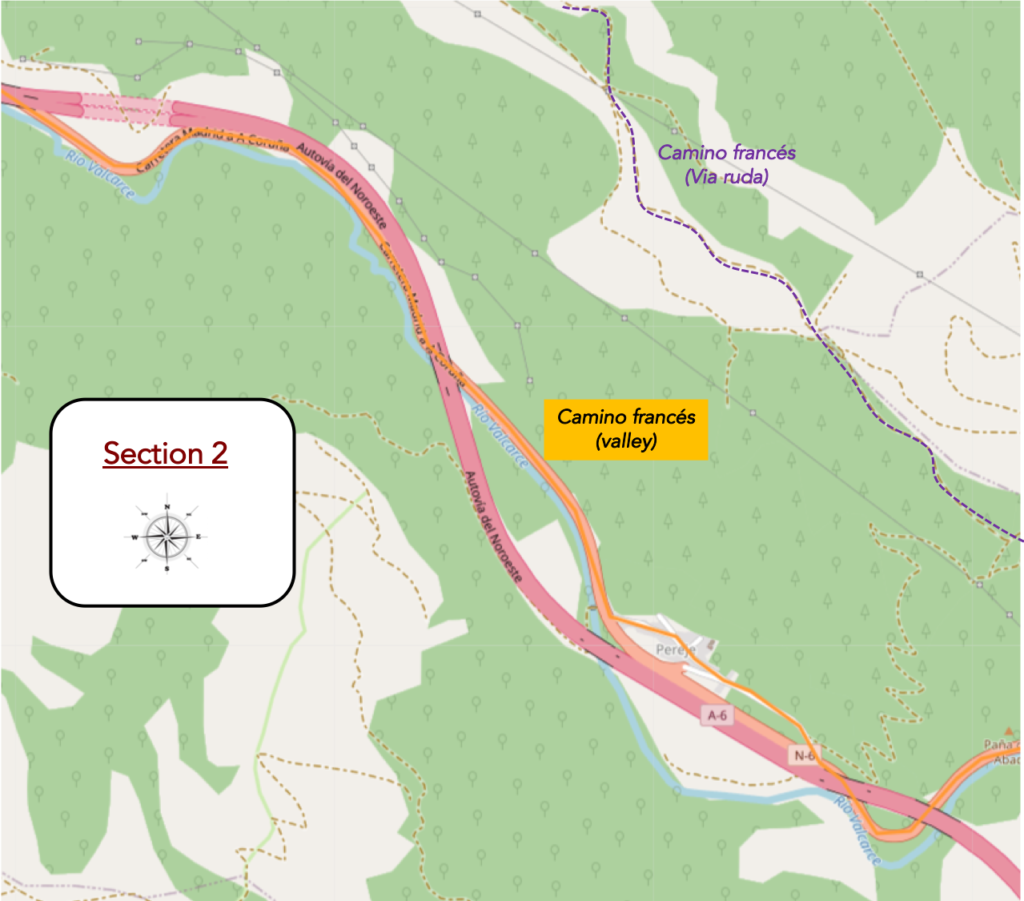

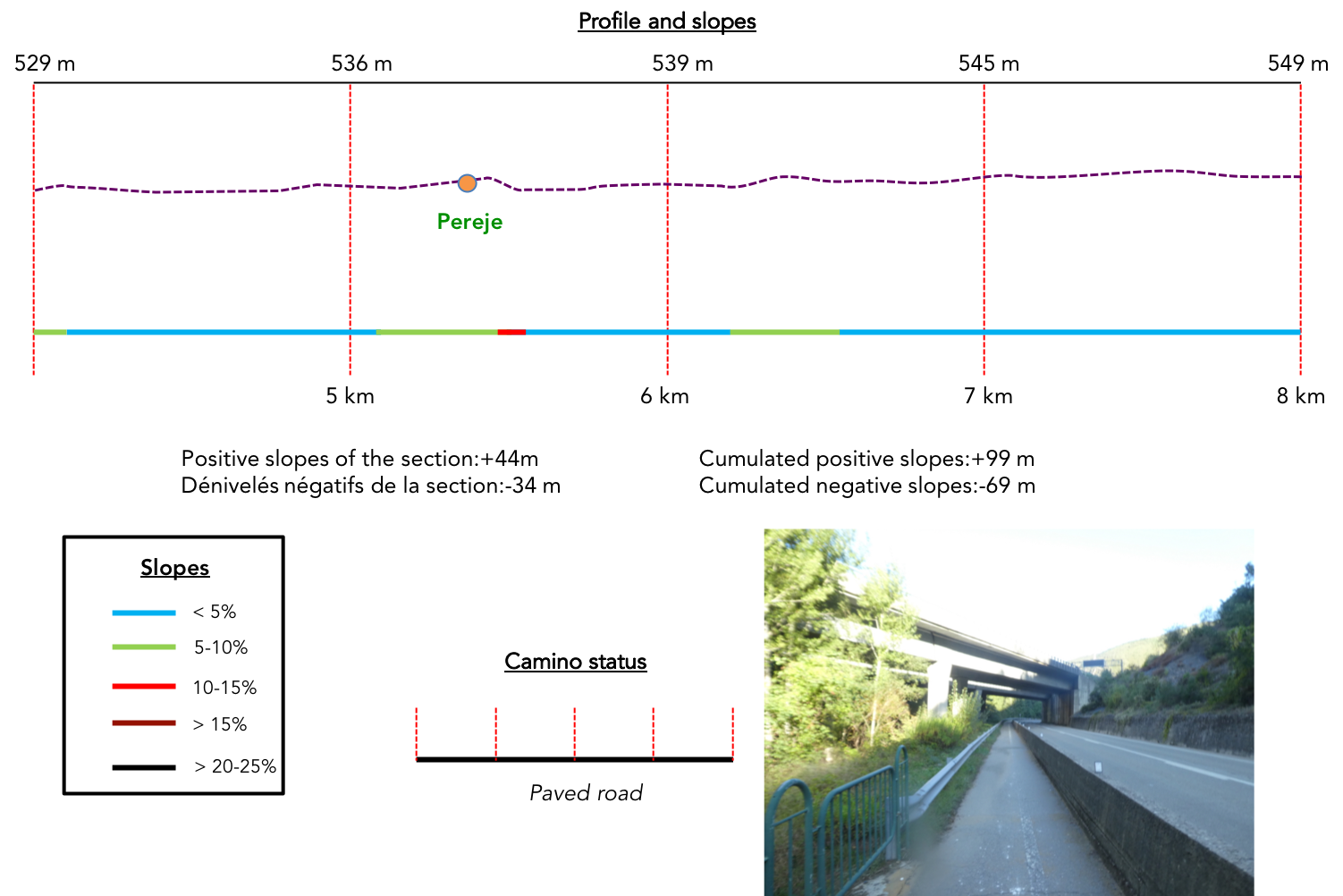

Section 2: Some undulations on the “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, even if the course slopes up constantly in an imperceptible way.

| The ball along the concrete blocks on the N-6 road continues and soon after the Camino runs again under the highway. |

|

|

| Further on, fortunately, the Camino will leave the national road for a while to head towards the village of Pereje. |

|

|

| The road crosses an area of heavy vegetation. Here grow chestnut and wild walnut trees, in the middle of the usual hardwoods. |

|

|

| Plus haut, la route arrive à Pereje. Ici, on a peint à la main le panneau pour changer l’orthographe du nom du village, passant de la version léonaise Pereje à l’orthographe galicienne Perexe.

Let’s situate the story, namely the centuries old struggle between Villafranca, in León, and Galicia for the Bierzo Valley, a story that has been told many times in the previous stages. To untangle the knot, the monarchy and the papacy intervened. In the XIIth century, the pilgrims’ hospital of Pereje was attached to the monastery of O Cebreiro, therefore Galician. This hospital was very useful for pilgrims who could not climb to O Cebreiro in the snowy season. Later, the quarrel became open between the monks of O Cebreiro, and the Cluniac monks of Villafranca. It became a religious dispute, with the matter going all the way to Pope Urban II, who ruled in favour of O Cebreiro. But there! Today Pereje is in Castile, not Galicia. So, for Galicia aficionados lost in enemy territory, all that remains is the possibility of expressing their disapproval, such as changing the spelling of a name. This is often the case in the wars of independence, which do not all use firearms. |

|

|

| The village is a traditional stop on the Camino de Santiago. The main street is called Camino de Santiago, testifying to the concentration of pilgrims who had to stop there in the past. At the time, there was a pilgrim hospital and even a prison. Today, the village has only 40 inhabitants. |

|

|

| The village looks like a mountain village, quite poor, with many sealed stone houses. Water flows from the fountain. |

|

|

The Church of Santa María Magdalena is in a bad state of decay. Apparently, you cannot visit.

| Leaving the village, the Camino finds the N-6 road back and the languid forced march along the river, which is hardly visible behind the foliage. The valley is still narrow. |

|

|

| Here grow beautiful maples and old chestnut trees, but the black poplars that line the road remain the masters of the place. |

|

|

| Further on, the N-6 road returns again to the other side of the highway. This ballet will eventually become boring. But, as an excuse, you have to understand the particularity of the region. To go to Galicia, in the north, there is no other possibility than to cross the Montes de León, and here the valley is narrow. To avoid this penitence. it would have been necessary to choose the Via ruda, which run much higher than this indigestible road network. |

|

|

| There are always the concrete barriers that protect you from the N-6 road, where a car rarely runs. On the other hand, vehicles drive on the highway and the valley is quite noisy due to its steepness. |

|

|

| Further on, the sun finally shines near a picnic spot. No doubt that pilgrims will stop there to finally taste the virtues of the sun. It took us nearly 8 kilometers of walking before finding the light. You can imagine that in rainy weather, this route will be even more brackish. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the N-6 road deviates again a little from the highway… |

|

|

| … but to better go back. The two axes will no doubt now be married for eternity. But, for the pilgrim, a slight change is looming. On the N-6 road, the exit for Trabadelo is announced. |

|

|

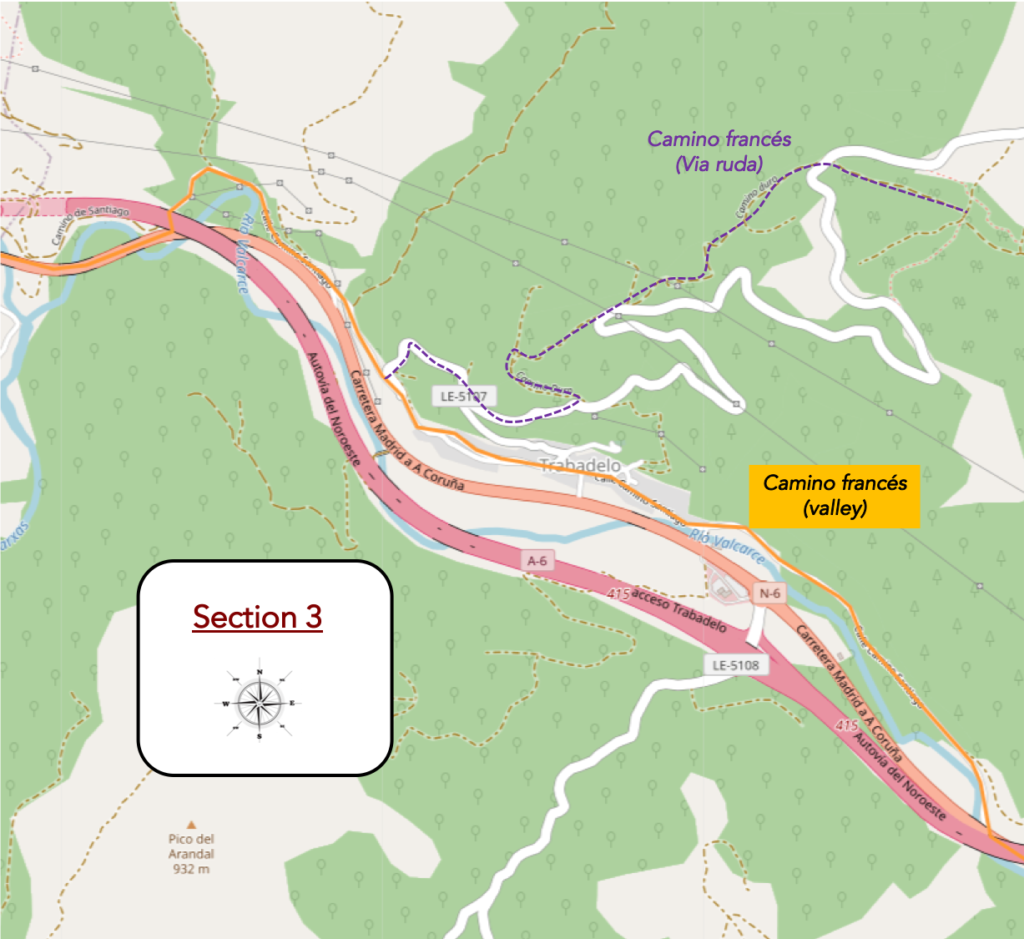

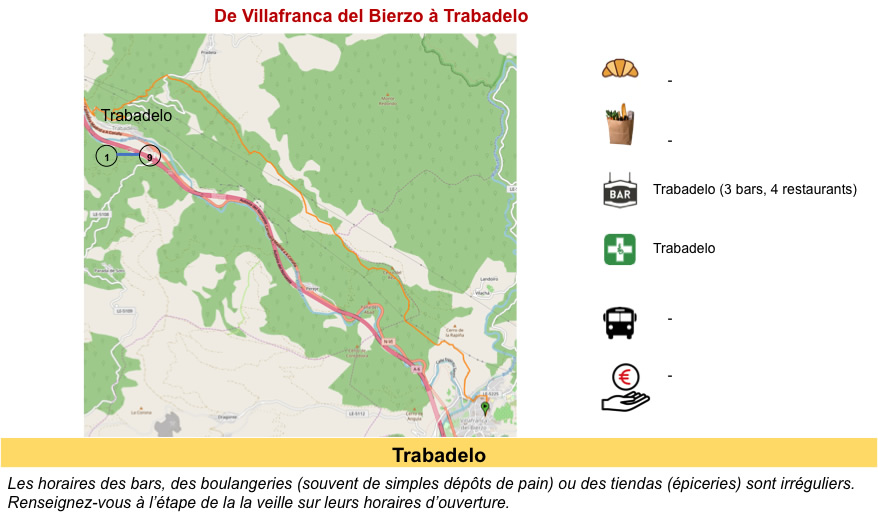

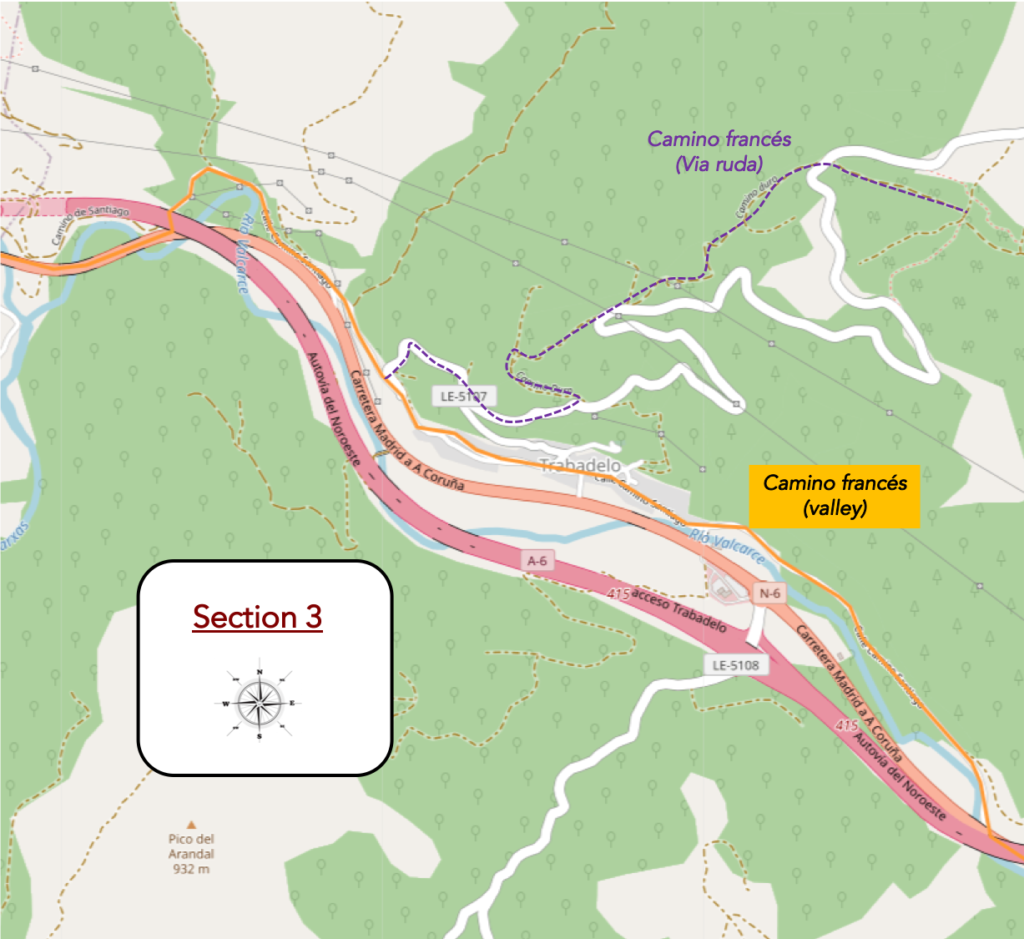

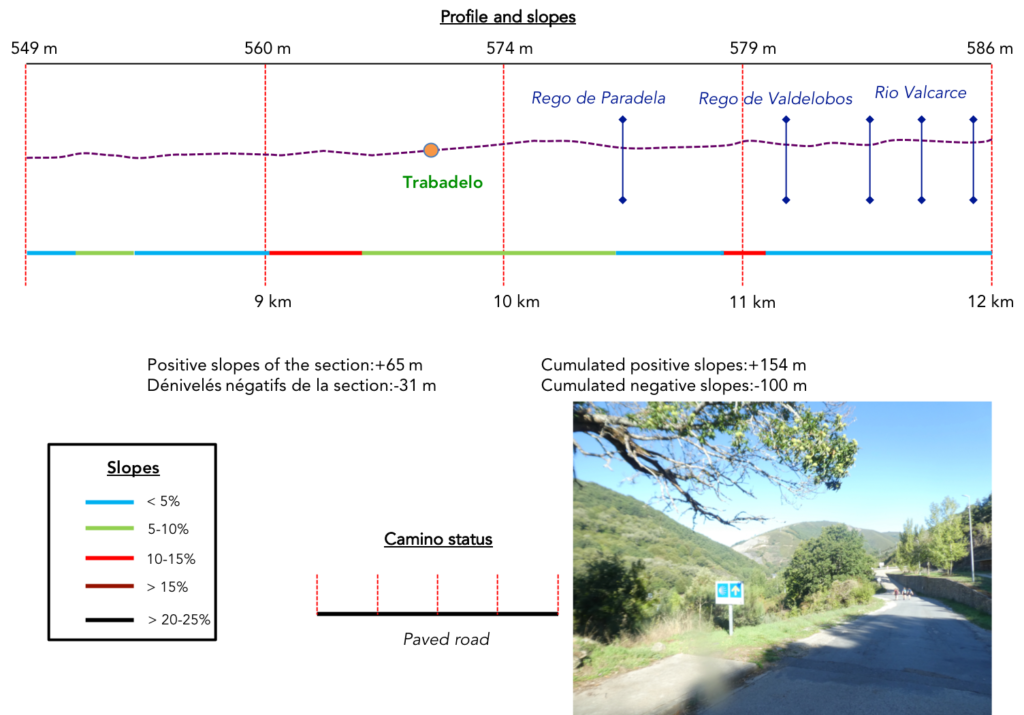

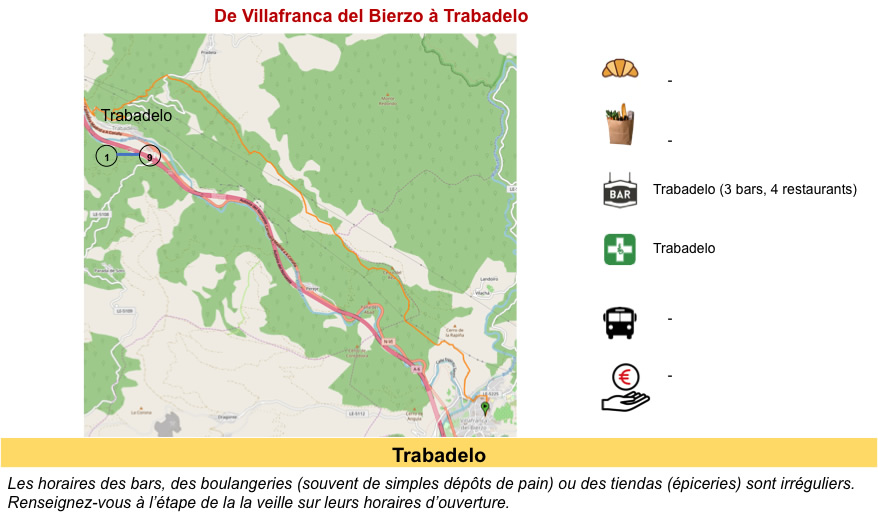

Section 3: A few ripples, again and again, on the “senda de peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, even if the course slopes up constantly in an imperceptible way.

| The Camino still passes under the highway and the route will finally change. At least for a few miles. You are going to leave behind you this long tarmacked road that you followed from Villafranca and a landscape that we will say a little repetitive, if not to say otherwise. |

|

|

| You are here 180 kilometers to Santiago when the Camino leaves the N-6 road to go towards Trabadelo. |

|

|

| It is a small road that climbs in stages, most often on a slight slope, in the abundant vegetation. The humidity is quite present here, and the ferns are tall as shrubs. In the middle of maples and oaks, chubby century-old chestnut trees have taken over to please you. |

|

|

| The heaps of chestnut wood are sometimes scattered, sometimes lined up like barcodes, adding to the charm of the place. |

|

|

Here is a sumptuous specimen that has found another purpose.

| Further up, the road arrives at the village. |

|

|

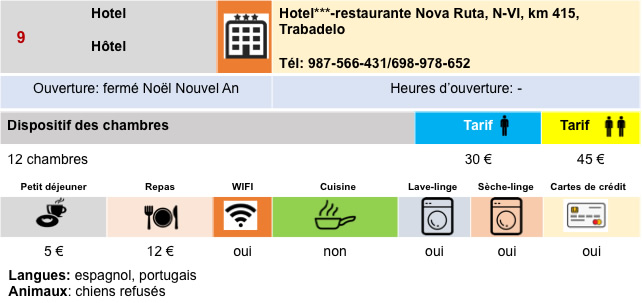

| The origins of the village date back to Roman times and the region’s gold mines. Then, the village, over the centuries passed alternately from Castile to Galicia, according to the sovereigns and ecclesiastics who disputed the region. In the Middle Ages, there was a toll to cross the region, which was abolished, which did not prevent some outlaws from ransoming and imposing their own tolls on innocent pilgrims.

It is a very elongated village, at the edge of which flows the Rio Valcarce. It is a Castilian village, but there is still here a council of the Galician language of Castilla y León. The crossing of the village takes almost a kilometer. |

|

|

| The village offers a good infrastructure for pilgrims. As a result, many pilgrims stop here, before facing the pass the next day. The houses are sometimes colorful, often in stone, with wooden balconies or awnings overlooking the street, as in all the villages of Bierzo.

Apart from the people who take care of the pilgrims, the 350 inhabitants of the village are mostly peasants. Livestock and agriculture remain the main axes today, especially market gardening. The chestnut is one of the flagship products of the whole municipality, an important source of employment. There are several companies dedicated to the chestnut trade in the municipality. The pig is the animal of choice in the region, and you will come across few cows, goats or sheep. |

|

|

| In a sloping street of the village stands the parish church of San Nicolás, surmounted by its belfry and its bells, a XVIIth century building. Closed, as it should. On the other hand, fresh water flows from the fountain. In the XVIth century there was a chapel dedicated to San Lazaro and next to it, in all probability, a hospital for pilgrims. Nothing remains.

From the IXth century, the parish church of San Nicolás in Trabadelo was under the protection of the Cathedral of Santiago. The church tower dates from the XVIIth century, as does the Baroque altarpiece. The church should house a small image of the Virgin and Child from the XIIth or IVth century. The problem with all these churches is that they often only open for evening masses, when the pilgrim has passed. |

|

|

| The Camino then gradually leaves the village. |

|

|

Along the way, you will come across an St Jacques, which is making the beautiful under the oaks.

| Further on, the Camino will wander for quite a long time on the road that leaves the village. Along the way, it crosses a small road. It is here that the Via ruda returns, which descends from the hill. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses the Rego de Paradela (rego is a Galician word for stream), a small bloodless stream, and goes to dawdle above the N-6 road. |

|

|

| Then, it deviates a little to prowl in the kingdom of the chestnut, before finding another small stream, the Rego del Valdelobos, as silent as the previous one. But, it is suspected that in rainy weather, it could be different. |

|

|

| Further on, the road arrives near the highway and the N-6 road, which progress together, pass under the piles of the two bridges… |

|

|

| …to end up again along the N-6 roiad. What a nice surprise, right? |

|

|

| Then begins a great waltz with the bridges over the Rio Valcacere. The river likes to weave on both sides of the road and the highway, which sometimes passes through tunnels. The river, at least in fact in its own way. On the course, as soon as you see a blue barrier the water flows below. And bridges, there are a good half-dozen before arriving at Portela de Valacre. |

|

|

| In the distance, you see the highway in front of you emerging from a tunnel. Nature is tortured in this deep valley |

|

|

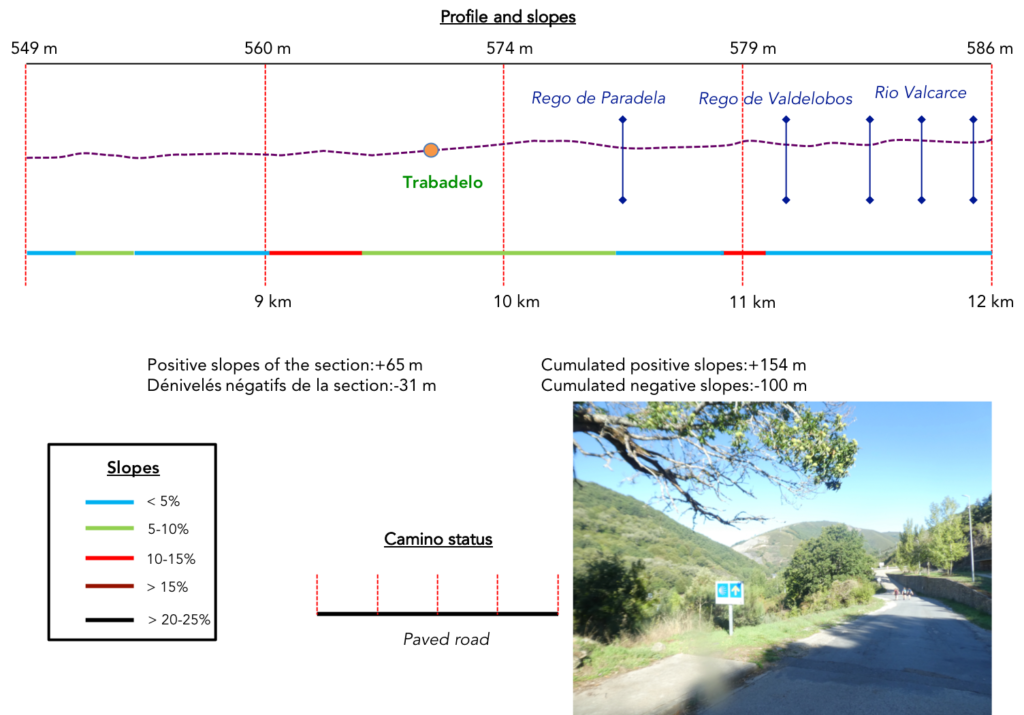

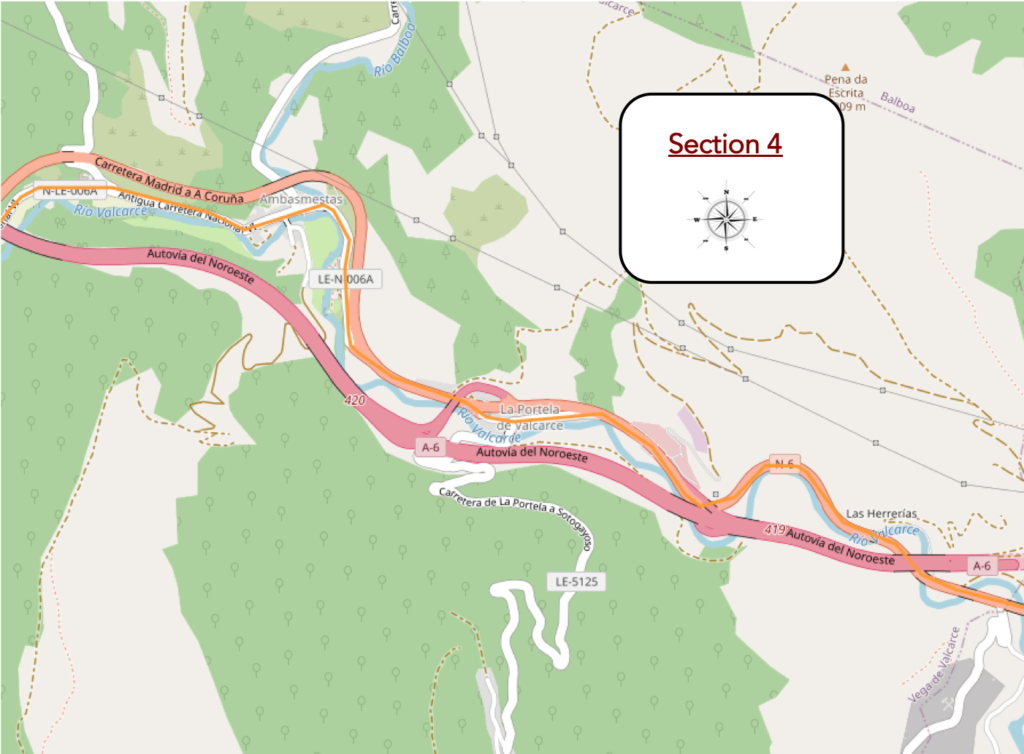

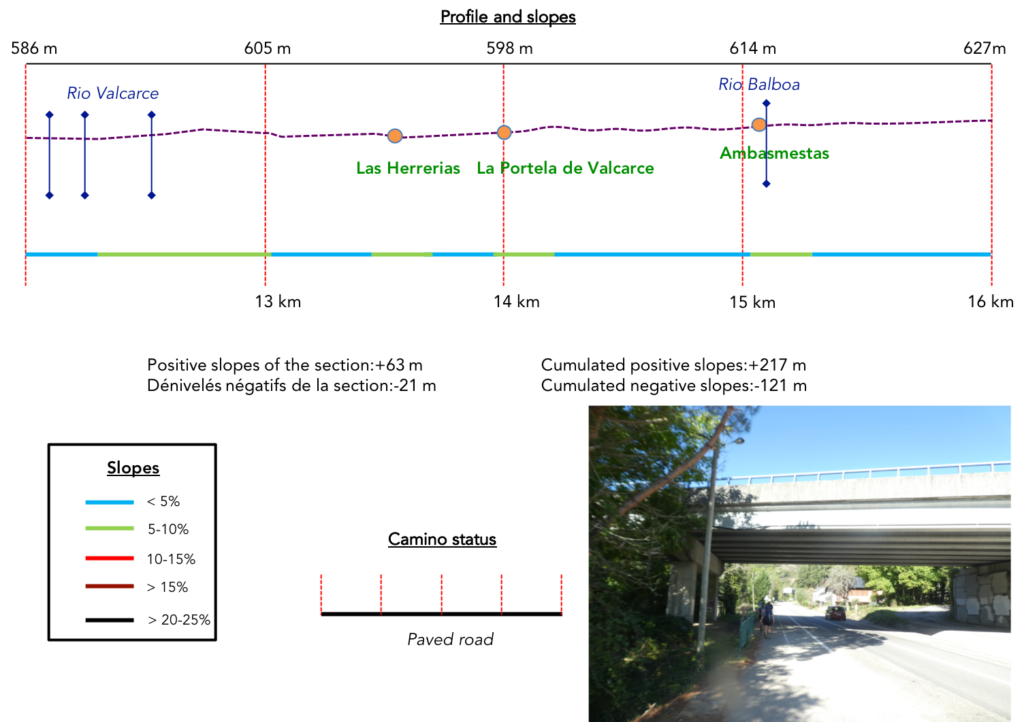

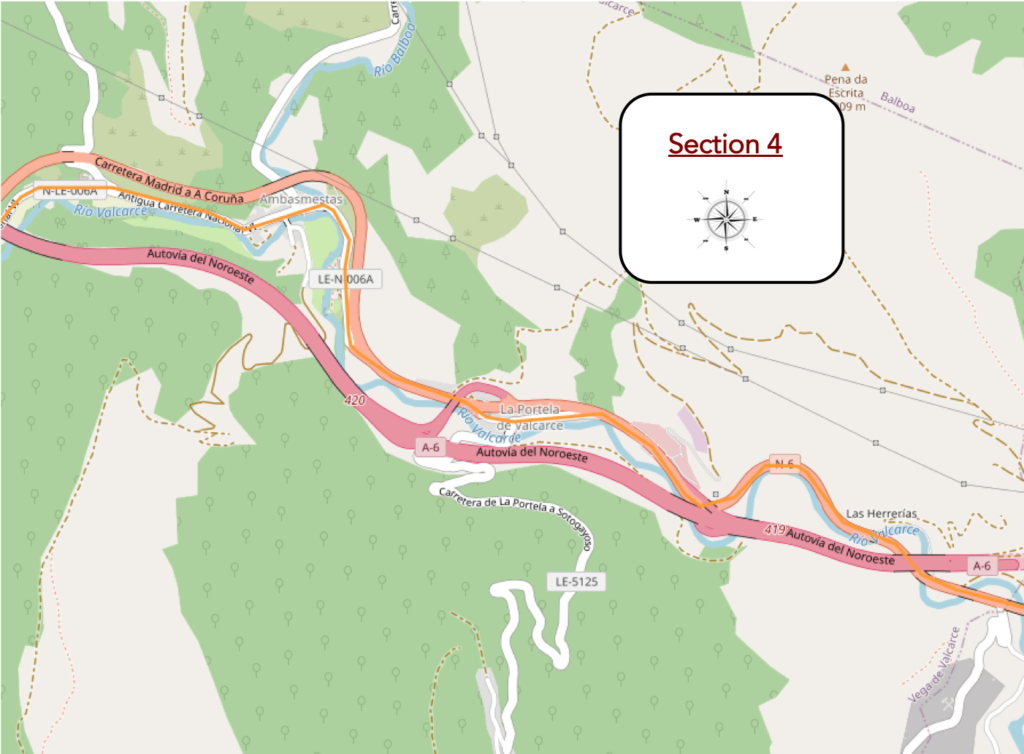

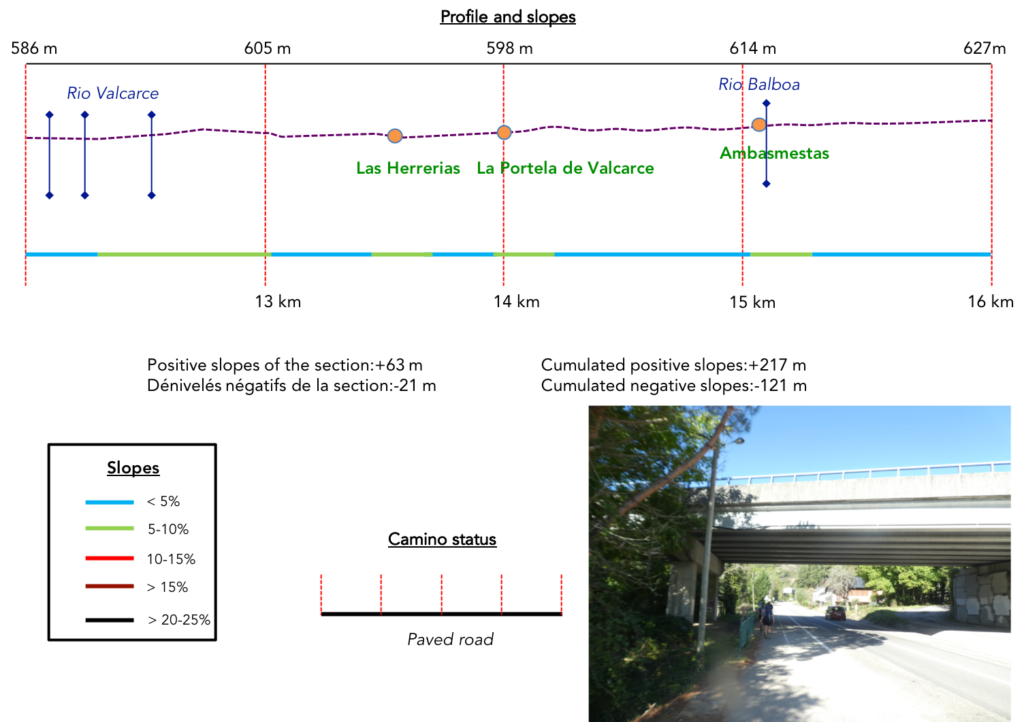

Section 4: You haven’t tried the “senda de peregrinos” enough yet.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, even if the course rises constantly in an imperceptible way.

| Further on, the N-6 road still plays with the river several times… |

|

|

| …before passing under the highway and ending up on the other side. To change a little. Without a doubt. |

|

|

| So, you’ll start playing leapfrog with the river again. |

|

|

| Las Herrerias that should not be confused with Las Herrerias de Valcarce, further on the route. A hotel, drivers who stop on the highway, solar panels that cover the mountain, and hikers who disembark to do a little Camino de Compostela, that’s the program. |

|

|

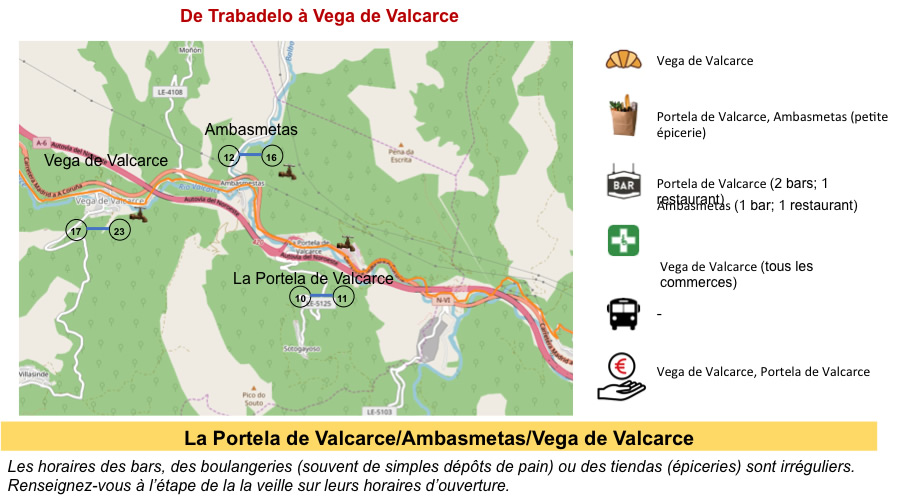

| La Portela de Valcarce is the next door, at the end of the square. The small village of La Portela de Valcarce also reflects the shift towards Galician culture. In feudal times, the nobles demanded the payment of a toll from all travelers wishing to enter Galicia, including pilgrims. It is believed that the name of the village derives from this toll, abolished at the beginning of the XIIth century by Alfonso VI, King of León and Castile. However, feudal lords continued to collect the tax over a century later. The first motorway tolls therefore date back a long time. |

|

|

| Portela means breach in Spanish, and narrow passage in Galician. We understand. One wonders again and again what money the pilgrims traveled with at that time, and how they paid the tax. 35 inhabitants occupy the hamlet, where there is a fountain and a picnic spot. |

|

|

Here, a monument with an ungentle-looking St Jacques marks the distance between Roncesvalles and Santiago.

| The parish church, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, is Baroque in style and dates from the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries, with its gable with three bells. Closed, of course. There would be a beautiful altarpiece here, with the central figure of San Juan Bautista, and old baptismal fonts. |

|

|

| Leaving the hamlet, the Camino stays on the N-6 road for a few hundred meters, running under the highway for the last time. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it leaves for another road, the N-6a road. Here, the Camino somewhat reluctantly leaves the N-6 and the A-6, which rocked you for 15 kilometers, and which leave we don’t know where under the mountain or in another valley. Because to cross the O Cebreiro Pass by car, there are only small mountain roads. But rest assured, the N-6 road and the A-6, you would find them later. If not them, it will be their twin sisters. The Camino francés cannot do without them. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the road arrives at Ambasmestas. Here, the ríos Balboa and Valcarce join here to give the village its name aguas mestas (mixed waters), which evolved into Ambasmestas. Once there was a Roman bridge here. The village is hardly bigger than the previous one, with about fifty inhabitants. |

|

|

| The medieval Nuestra Señora del Carmen church looks like all the other churches in the valley. They are made of large stone rubble, with a steeple proudly displaying bells. Maybe you will have the privilege of finding it with the door open, who knows? |

|

|

| The road leaves the village and wanders for a good kilometer under the splendid chestnut trees. You understand that the chestnut is indeed the priority occupation of the peasants of the valley because the cattle are almost non-existent in the meadows. |

|

|

Below the road, under the chestnut trees, it is always the Rio Valcarce which coos.

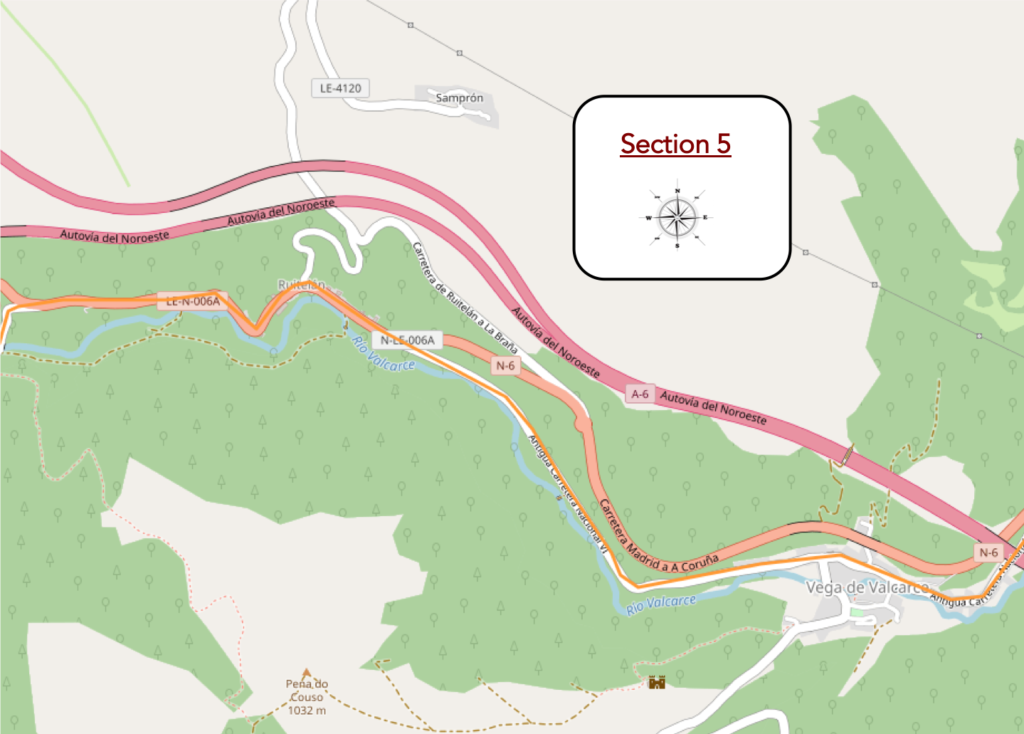

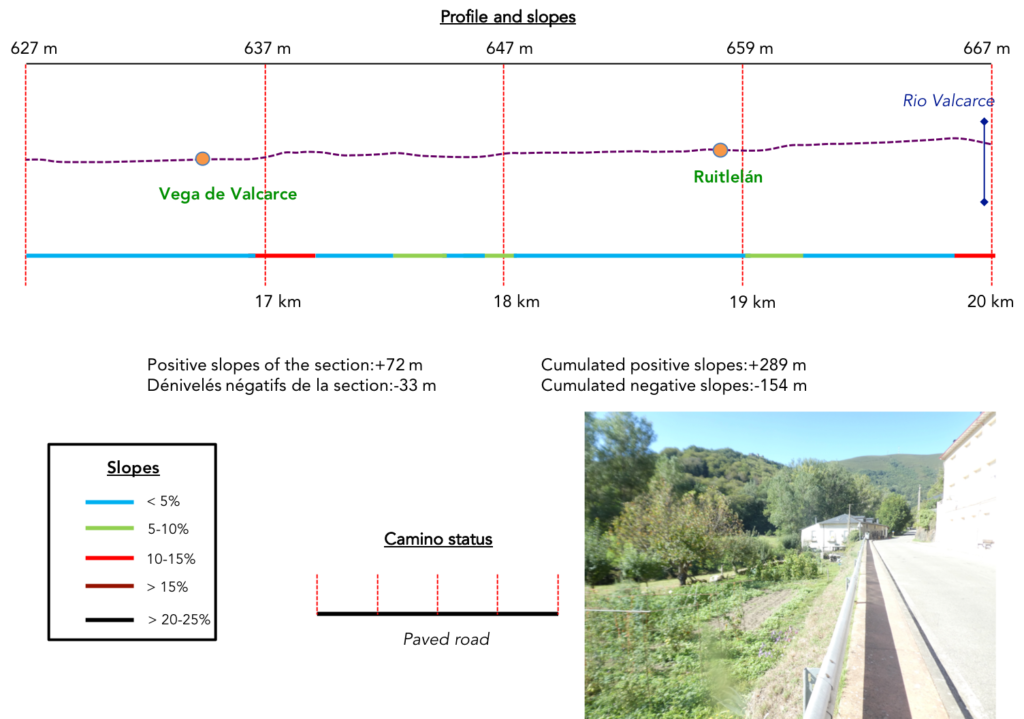

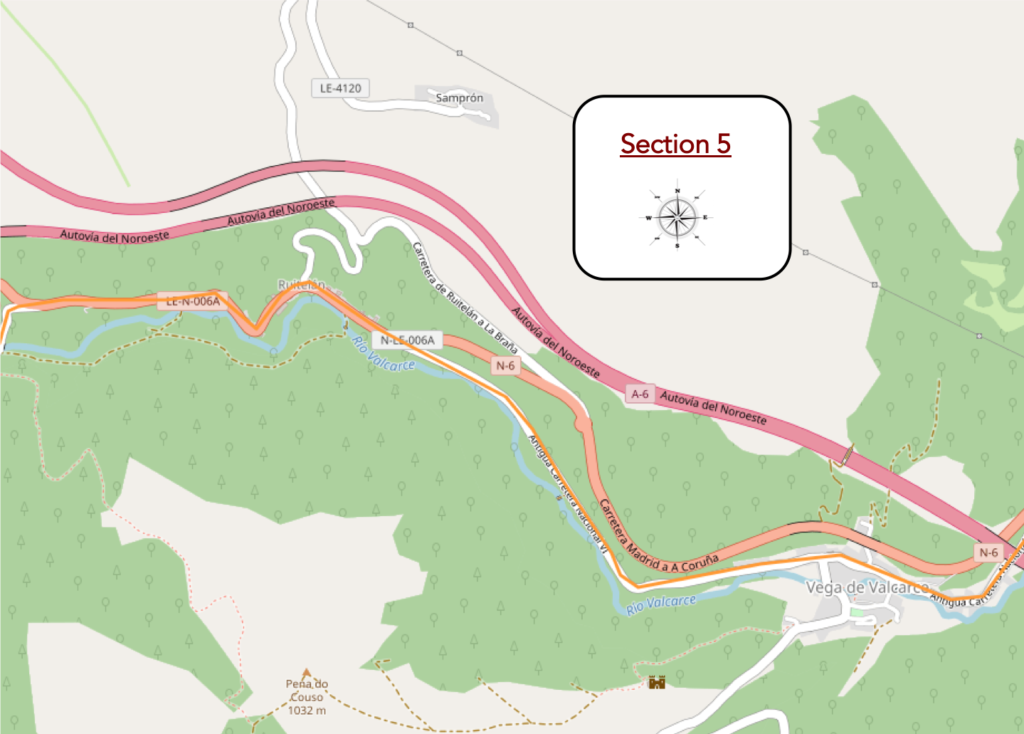

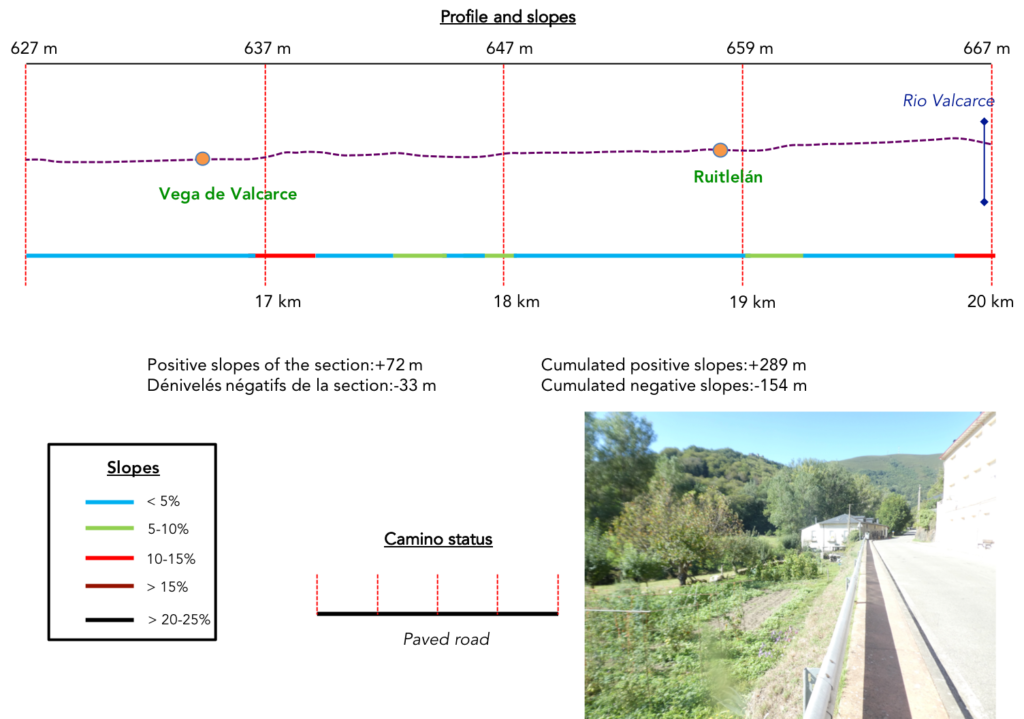

Section 5: A few steps from the climb to the Pass.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, even if the course slopes up constantly in an imperceptible way.

| Further on, the imposing motorway bridge can be seen, when the road arrives at the outskirts of Vega de Valcarce. |

|

|

| The approach to the village is very long, here too, the village close to the highway, well below. |

|

|

| Beautiful stone houses sometimes adorn the road to get further, to the center of the village (500 inhabitants). The village is the main entrance to Galicia from Castilla y León. From the time of the Romans, criminals and bandits who preyed on passing travellers, mainly pilgrims and merchants, invaded the region. |

|

|

| The country’s history really begins with the reconstruction of a mythical castle here, the Castillo de Sarracín, which would have been destroyed by Muslim invaders in the VIIIth century. Its reconstruction will begin in the IXth century, after the Reconquista. At that time, the Bierzo was an Asturian land. King Ordoño I of Asturias charged his brother, Count Gatón, with the reconquest and repopulation of the region, up to Astorga. Then, it was his son Sarracino Gatónez, Lord of Sarracín, who succeeded his father as Count of Bierzo and Astorga. Count Sarracino also founded the city of Vega de Valcarce. When you cross this small village today, you have little idea of what the city must have represented in the past.

The castle was built to guard the road through the valley, to control the bandits present in medieval times, who harassed the pilgrims. It is also for this reason that the Templars later occupied the place. With the dissolution of the Templar order in the XIVth century, the castle passed into the hands of the Marquises of Villafranca, who partly rebuilt it. During the following centuries, many crowned heads spent the night here. Today is a ruin up there on the hill before you. |

|

|

| The village is one of the 47 municipalities of Galicia estremeira, that is to say a country not located in Galicia, but which speaks a Galician dialect. Of course, if like us, you use travel Spanish, you will have a hard time getting into these linguistic subtleties. But, as this subject is of cultural importance here, it is good to take a little leap into history to understand Bierzo and Galicia. Their common history began in the High Middle Ages, when the country passed from the governance of the Kingdom of Asturias to that of León. But already, in the Xth century, León donated the Valcarce Valley to the monastery of Samos, in Galicia. Then, in the XIIIth century, the Pays de Valcarce was given as an ecclesiastical seigniory by the kingdom of León to the cathedral of Santiago. It is therefore to this period that the toll for the passage in Galicia dates back.

Subsequently, the lordship of the Pays de Valcarce passed into the hands of the Rodríguez de Valcarce family, which in the XIVth century ended up integrating practically the entire western third of Bierzo. Later, in the XVth century, there was a great upheaval throughout the country, during the reign of Carlos I, King of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, who thus united for the first time in one person the Crowns of Castile, Navarre and Aragon. In the region, to cut short the problems of succession, the Catholic Monarchs solved the question with the creation of the Marquisate of Villafranca, attached to the province of León. But, as we have already said, the Galician culture never really disappeared from this country, and until Ponferrada. |

|

|

There is a church, also closed, the Church of La Magdalena, a solid and rectangular building, renovated many times over the centuries.

| At the exit of the village, it is a road, which undulates slightly under the trees. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road shows a steeper slope, in the middle of chestnut trees, oaks and poplars, which provide their shade. |

|

|

| Shortly after, in front of you, the high pillars of the highway loom again, forming an impassable barrier above the straight road. |

|

|

| Little by little, the highway becomes more present. Wind turbines dance on the hills. |

|

|

| On the side, in the meadows, still flows the Rio Valcarce, which is only a trickle of water here. In front of you, stands the double viaduct of the highway. |

|

|

| Ruitelán is just on the other side of the hill, under the majestic chestnut trees, which make like a garland. |

|

|

| In this small hamlet of 30 year-round residents, there is a relaxing park with a fountain by the river. Not far from here lived, in the IXth century, St Froilán, who later became bishop of León. The small hamlet of Ruitelán is located near the ancient Roman city of Autharis or Uttaris, in the Sierra de Ancares mountains. |

|

|

| The road crosses the village, as big as a pocket-handkerchief, passes in front of the church… |

|

|

| …and continues under the chestnut trees. Above the hill passes the highway. Nature is beautiful and generous here. |

|

|

| Further on, in what looks like a small paradise, the road arrives at the entrance sign of Las Herrerías del Valcarce. But, this is only the entrance sign, because the village is further. |

|

|

| The road heads to an inn, where many pilgrims stop and continue…. |

|

|

| … before descending on a steeper slope to cross the Rio Valcarce, on the so-called Roman bridge. |

|

|

| This bridge, at least in its upper part, has nothing Roman about it. It was only built in the XVth century. It is made of roughly carved stone masonry with a very open vault. It has no parapet. |

|

|

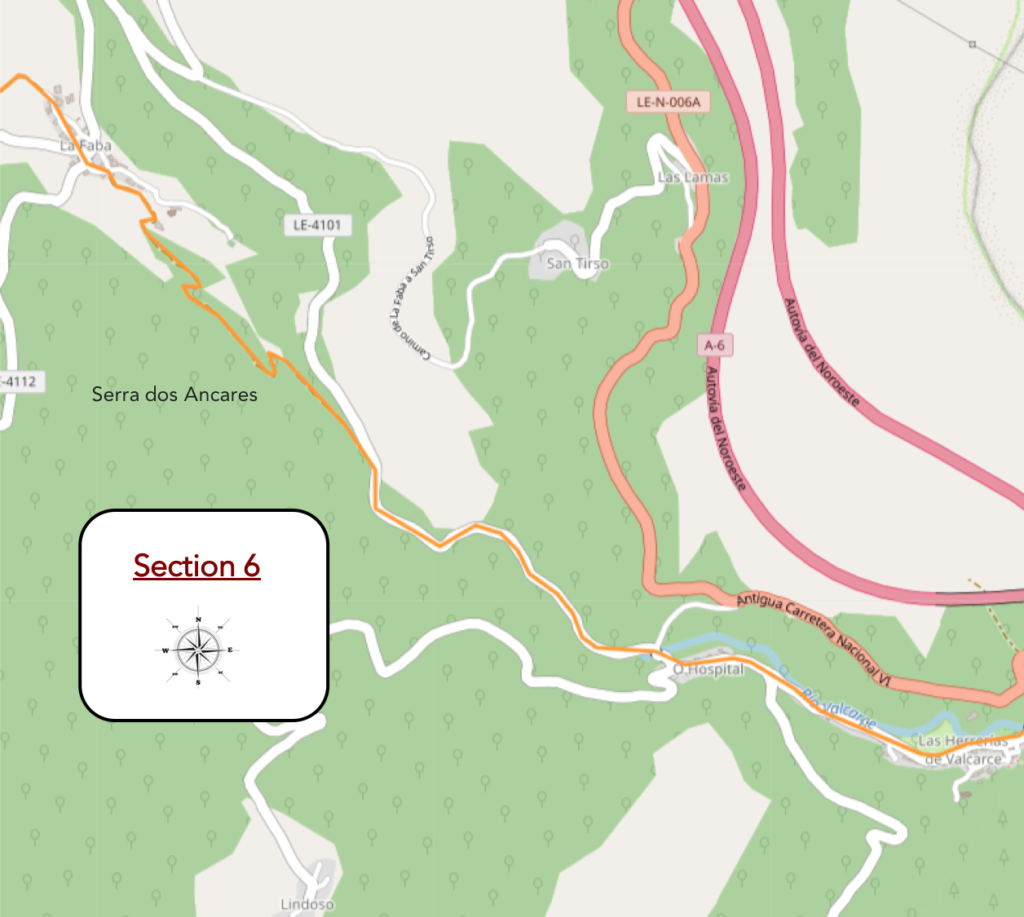

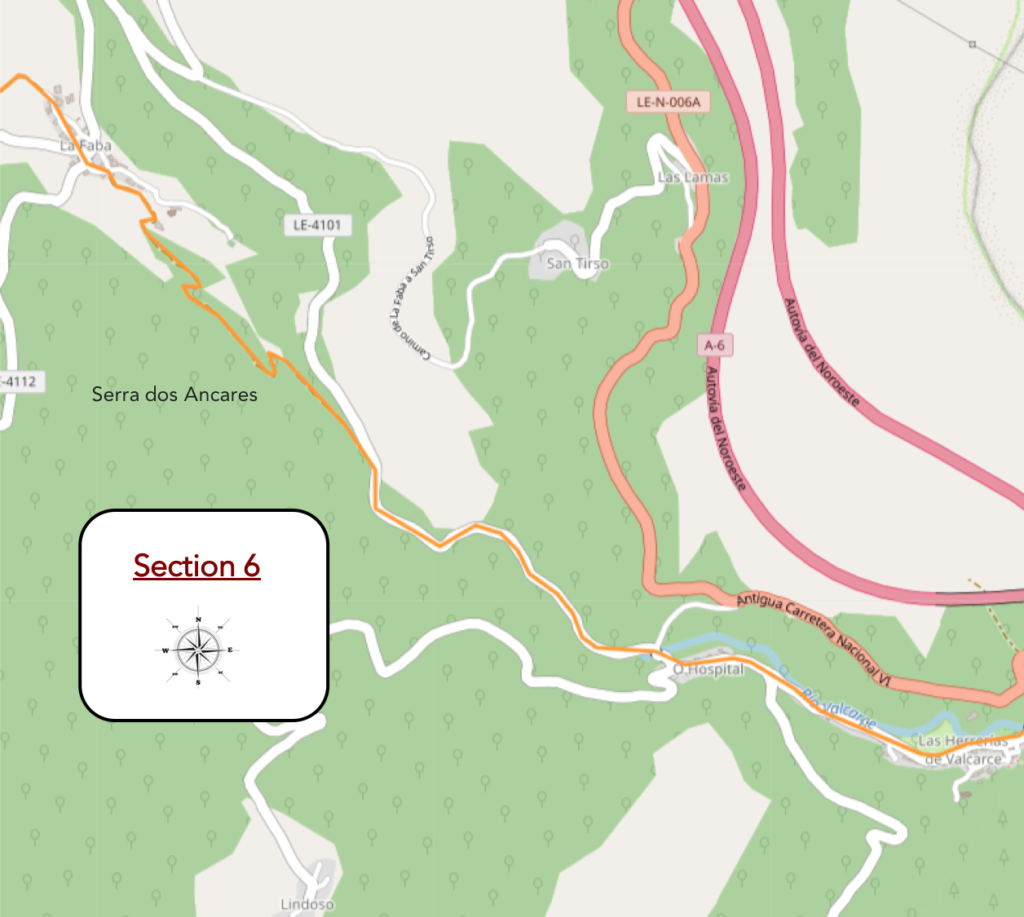

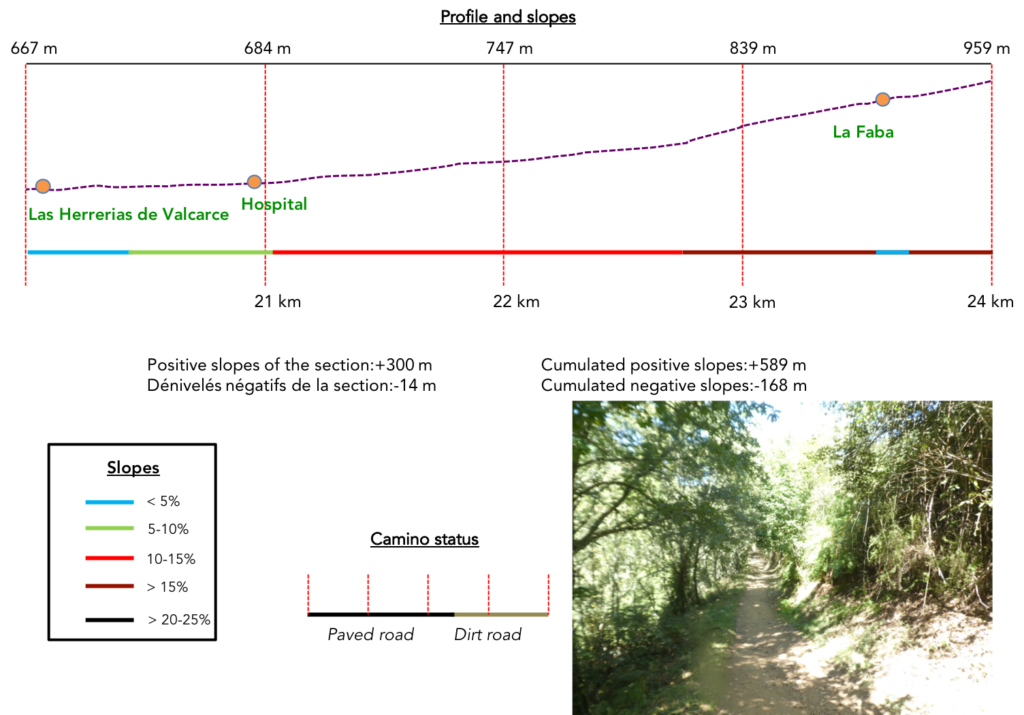

Section 6: First ramps to O Cebreiro.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: 300 meters of elevation gain over 4 km, with tough slopes.

| The name herrería means forge and refers to an ancient iron industry in this mining region. As soon as you really enter the village, the actual crossing is brief. |

|

|

| There was a hospital here for pilgrims, called Hospital Inglés known from the Codex Calixtinus. The historical archives say that this hospital was founded at the beginning of the pilgrimages, in the XI-XII centuries and that its founder was French. There was also a chapel and a cemetery where the deceased pilgrims were buried. As pilgrimages declined in the following centuries, these places were used as warehouses. At the beginning of the XIth century, the French set fire to the chapel and ransacked the hospital. All of that is gone now. |

|

|

| The river meanders along the village. The isolated houses follow one another up to the village of Hospital. Here, near the river, you see cattle in the meadows, goats and cows, which are not common in a region that is said to be livestock. The fountain by the river is known as Fuente de Quinoñes, in honor of the chivalrous knight who defended the Órbigo bridge. |

|

|

| Further on, the road climbs through gently sloping meadows towards the village of Hospital. |

|

|

| Hospital is the last village, at the bottom of the valley, where the climb to O Cebreiro only begins. You will therefore have walked in the valley for 21 kilometers, without effort, going from 513 meters above sea level in Villafraca del Berzo to 684 meters here. Just nothing, right? But that will change quickly, it is written above. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses for the last time the Rio Valcarce, which is lost higher up in the ravine. |

|

|

| So off you go for a ride at a 15% slope on the tarmac for 1.5 kilometers. |

|

|

| What to do? What to say? Count your steps; take a look at the overflowing vegetation. Here, oaks of all kinds have taken the place of chestnut trees in the wild valley. |

|

|

| There are sometimes small limestone rocks that outcrop. |

|

|

| 1.5 kilometers higher, comes the choice for walking pilgrims or cycling pilgrims. Cyclists will follow the road, walkers the pathway. If you feel like a cyclist or you don’t like walking on steep pathways, hit the road. You will also arrive at Faba, 156 km to Santiago. |

|

|

| By the way, the effort will be tougher, most often at almost 20%. On the road, expect a bit of the same gradient. |

|

|

| It’s still amazing how the dirt changes your state of mind. Walkers know this well. Here, on the pathway or on the road, it is the same landscape, the same trees. But, take a side road and your soul evolves in another world. So, on the pathway that climbs in the forest, you imagine these bits of forest hanging down like so many real asylums, yesterday for wolves, today for wild boars and deer. Here you walk in the Serra dos Ancares, this large mountainous and wooded massif that covers part of the Montes de León and especially Galicia. |

|

|

| It’s steep yes, but beautiful. When the light penetrates a little more, then the trees gain in size. The chestnut trees bloom with pleasure. Oaks, ashes and maples compete in height, high up in the canopy. |

|

|

| But, most of the time, you rarely see the sky under the huge roof of branches. The roots enclose the embankments and the trees stand straight behind the stonewalls where the moss crawls. |

|

|

| In this ocean of greenery, the pathway sneaks furtively. Under the high forest grows a thick copse of shrubs and small trees. A few plants manage to survive, low grasses impoverished by the lack of light and ferns. |

|

|

| Here, there are no big trees. Muffled suckers of chestnut, maple and hazel look like stocky little dwarfs with a short feather duster of slender branches |

|

|

| Further up, nature opens the light again. Then the trees regain their height, great providers of shade. |

|

|

| Soon the first signs of human presence appear again. |

|

|

| The Camino then arrives at La Faba. The name La Faba evolved from the Moorish al fawara, meaning “abundant spring”, as Muslims also passed through here. Under the current cemetery, there were perhaps the remains of an early Mozarabic church dedicated to Saint Andrew. The current church was built in the XVIIth century because the previous one was in poor condition. |

|

|

| There were two “albergues” in this magnificent hamlet where stones are bursting everywhere. One of the two unfortunately burned down at the beginning of 2022. The other is buzzing like a beehive. It must be understood that after a steep climb (more than 250 meters of altitude difference from Hospital), this type of establishment is taken by storm. It speaks loudly, very loudly, too loudly, in American most of the time. |

|

|

| As soon as you leave the village, the stony pathway finds the brushwood and shrubs of the undergrowth. |

|

|

| But, it does not make old bones, and quickly you find the light back, on a pathway, which climbs to nearly 20% of slope. |

|

|

Up there, the moor stretches up to the heights, letting your mind wander and your calves harden.

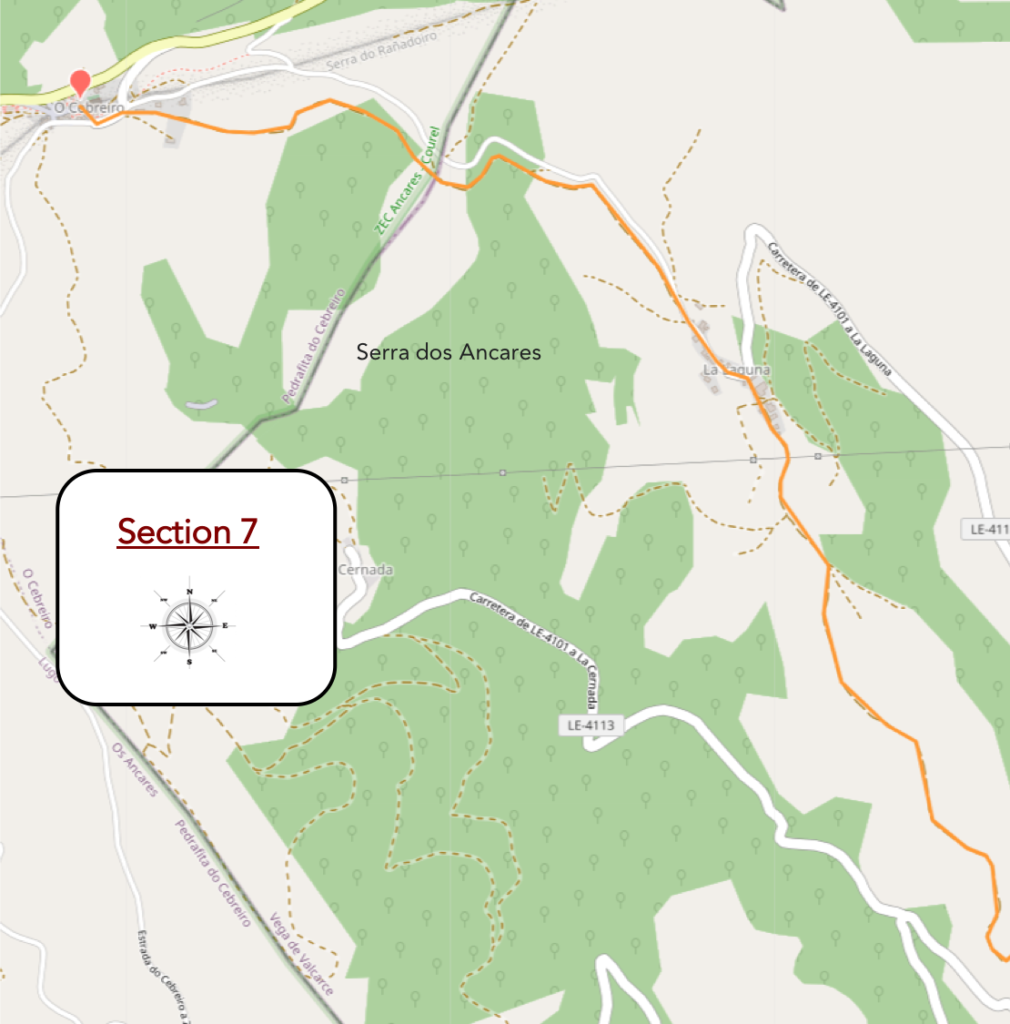

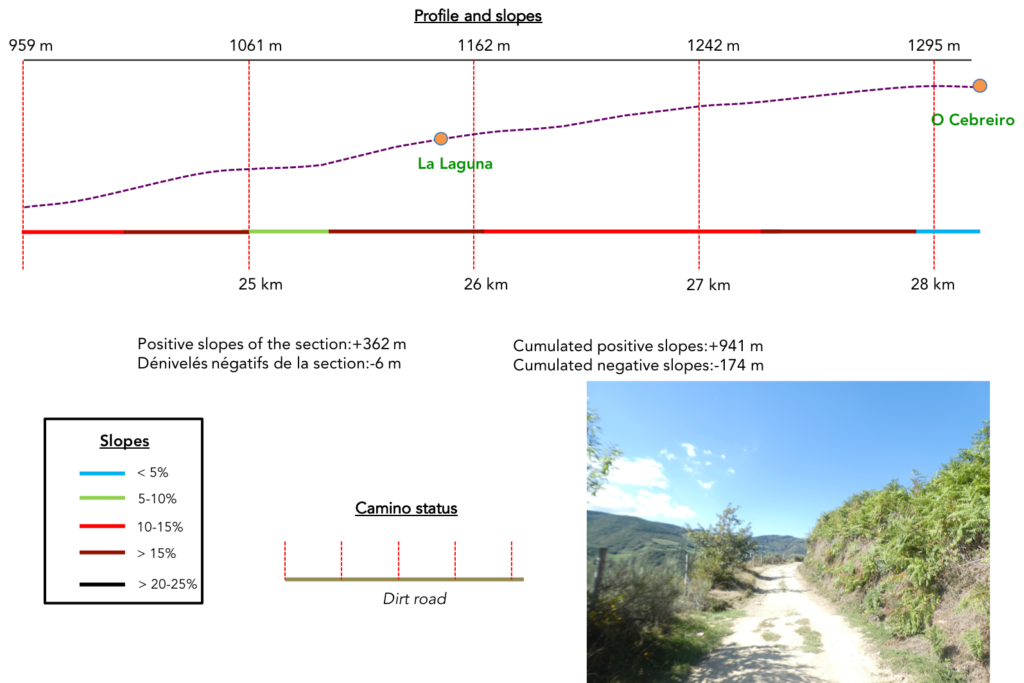

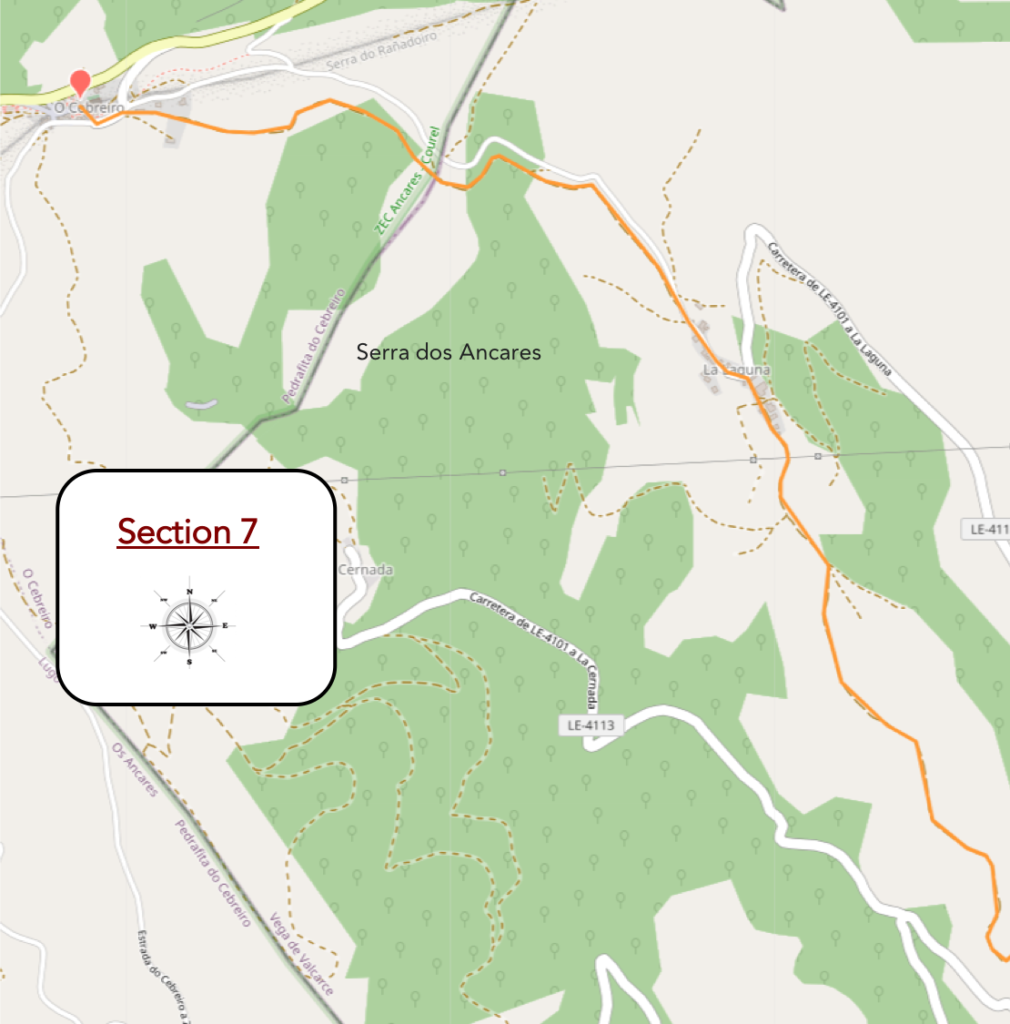

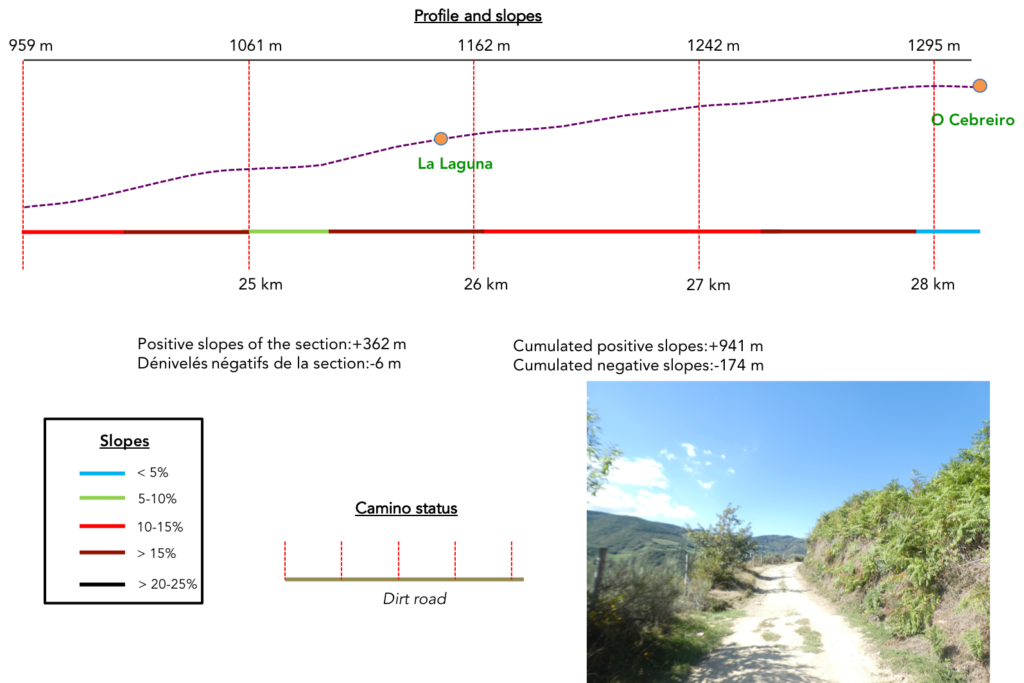

Section 7: Up there, in O Cebreiro.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: 360 meters of elevation gain over 4 km, with severe slopes.

| On the slopes cling cypresses, burnt lavender, brambles, heather, gorse and juniper. It is the moor, all the poorer as men abandon it. |

|

|

| Here, nothing really grows, except the grass, dry in autumn, which lies down in the winds, and the thin bushes, which survive from one year to the next. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway finds a little shade, but the slope does not diminish. |

|

|

| The wild cypresses take height on the embankments and the pathway, for a few hundred meters calms down a little on a less steep slope. |

|

|

| So, you can see the hamlet of La Lagune above, reaching out to you. |

|

|

| Here, the slope starts to rise again. Now, there are a few trees, especially oaks, which appreciate these barren soils, and which look beautiful along stonewalls. |

|

|

| One more last push, and the Camino arrives at La Lagune. |

|

|

| Here, pilgrims take a break at the “albergue”. The climb was tough from La Faba, with nearly 250 meters of elevation. But the climb is not over. There are two kilometers to go to reach the pass, at O Cebreiro. Some pilgrims spend the night here, because they believe that the day spent is enough for their happiness and that it is not always easy to find a place at the pass to stay. |

|

|

| La Laguna de Castilla is the last village in Castilla y León, before entering Galicia. However, this village is Galician in its essence. The village is known as the “village of two lies”, because there is no lagoon and it does not resemble the Castilian landscape at all. The name actually comes from a Celtic word Aghun, which the Muslims supplemented with al-aghuna, which over time turned into La Laguna. |

|

|

| As soon as you leave the village, the slope takes off again. However, it is a little less steep than before the village, between 10% and 15%. |

|

|

| It is quite a long time, like lower down, a country of open, scrubby moors, dominated by tall cypresses, laburnums and gorse, with here and there clumps of oaks. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway then crosses an area where the vegetation is denser again. |

|

|

| But, that does not last long, and the pathway returns to its normal course in the moor. And, icing on the cake, the slope is again more demanding. |

|

|

Further up, a signpost appears on the embankment, indicating Santiago at 152.5 kilometers and bearing the inscription “Teso dos Santos”. There was once a small chapel here marking the border between León and the province of Lugo in Galicia. The old Galician-style poles have been modified and modernized in recent years.

| And the pathway continues to climb in the enchanting nature. Here a man descends with three horses. The third escaped. There are sites that organize transport on horseback from the bottom of the valley. It’s like in the desert, when you ride a camel. You learn to ride these beasts in minutes. In the desert as in the mountains, these animals know the way well. You feel like you are in control. What an illusion! But the horses have to be brought back to the fold. |

|

|

Soon after, the Camino says goodbye to Castilla y León. It is a border without customs officers. You are now in Galicia and, more precisely in the province of Lugo. Here, tears of happiness sometimes flow down the faces of pilgrims who have come from far, far away, sometimes from eastern countries or Italy. To be so close. Obviously, many Spaniards start the Camino from León, few in Roncesvalles. So, for them, Galicia or Castile is the same country.

| Further on, the Camino still crosses the undergrowth before arriving at the pass. |

|

|

Honestly, you will never have the feeling of having changed country when entering Galicia. It is always the same wooded hills that scatter in a distance that is not very accessible. A mysterious legend says that the Holy Grail is hidden somewhere around here, and it is believed.

| Before the pass, the pathway heads to a large stone building, under the trees. |

|

|

| A bronze lady welcomes pilgrims. The pilgrims who make the way in winter (and there are some) often arrive here in a harsh climate, with snowfall and abundant ice. The pass is 1,300 meters above sea level. There are never too many tourists, except in summer, and you can enjoy solitude and peace. But, it is relative, there may be more than 1,000 pilgrims passing through or stopping at the pass. |

|

|

| There is a Calvary and a beautiful esplanade in the courtyard above the village, where the pass road arrives. Due to its strategic position, the pass was an important place during the Spanish War of Independence, which opposed Napoleonic troops to the Bourbons of Spain, Portugal and England. The village has about twenty houses developed from and for the pilgrimage. It is one of the most unusual villages on the Camino, still reflecting its ancient origins. The origin of the name is debated. Some sources say he comes from cebrarium, a place with many wild donkeys (asnos, also called onafros or cebros). Other sources say the name refers to the zebra or enzebro, an animal similar to a zebra but without stripes, once very abundant in Galicia until its extinction in the XIVth century due to hunting for its skin. In the Codex Calixtinus the village is quoted as Mons Februarii, saying that there was a hospital at the top of the mountain. This area has been occupied since antiquity. Before the arrival of the Romans, there was a Celtic settlement here. |

|

|

| The story begins here around the XIth century. The Church of Santa María La Réal seems to have its origins in a hospital for pilgrims, which would have been the first construction linked to the pilgrimage of O Cebreiro, built by the French. The church would have been built in the XIth century, being originally a priory dependent on the blessing monks of Aurillac. Subsequently, from the XVth century, the priory passed into the hands of the Benedictines of San Benito de Valladolid. Among the patrons, we must highlight the Catholic Monarchs, who after their stay here in the XVth century, donated a reliquary to preserve the sacred relics of the miracle of the Holy Grail.

The story of the miracle is part of the tradition of the pilgrimage to Compostela. One particularly snowy winter day, a monk was celebrating mass in the church. A neighbor of the parish, called Juan Santín, braved the storm and went to the church to attend mass. The monk underestimated the sacrifice of the parishioner, exclaiming when he saw him arrive: “Who comes, in such a great storm, to tire himself to find only a little bread and wine! ”. At that precise moment, the host was transformed into flesh and the wine into blood. In the reliquary are the chalice, which, according to tradition, was used at the Last Supper, and the cup of the young man. |

|

|

Santa María La Real also houses the tomb of a prominent priest. Historically linked to the Camino de Santiago and charged with a strong symbolism, the notoriety of the village and of the Camino francés in general, we owe it above all to the work of its parish priest, Elías Valiña. He was the visionary promoter of the pilgrimage to Santiago since the 70s. A tireless researcher, he devoted decades to mapping what we know today as the Camino fracés, initiating the signaling of the route with the now yellow arrows traditional.

| The village preserves intact a set of pallozas, stone dwellings with thatched roofs, generally circular, still inhabited not so long ago. These pre-Roman dwellings, of Celtic origin, are the oldest houses in Spain and have survived the centuries thanks to the geographical isolation of this region. They are perfectly preserved or restored in this village. In addition to being used as dwellings until less than a century ago, they were also used to keep livestock. One of these houses is integrated into one of the two rural tourism establishments in the locality. The other, much older, has been converted into an Ethnological Museum. You should also stop off at the San Giraldo de Aurillac inn, probably the busiest since Roncesvalles, since it started operating in the IXth century.

Here are some images of these places, in the early morning, before the departure of the pilgrims. |

|

|

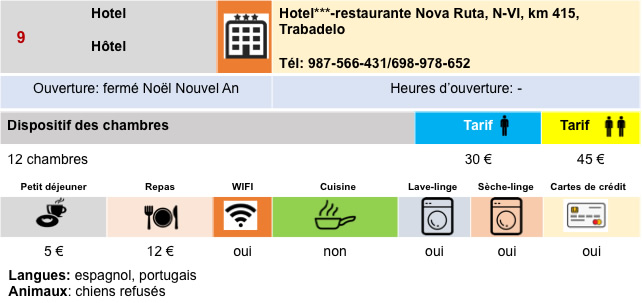

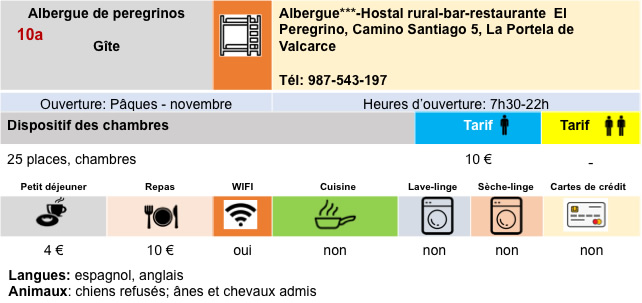

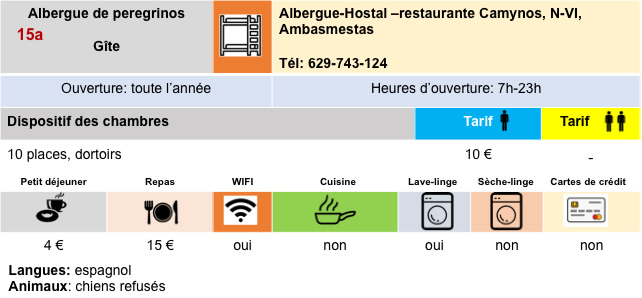

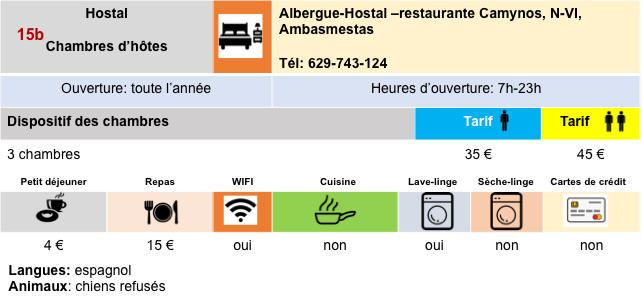

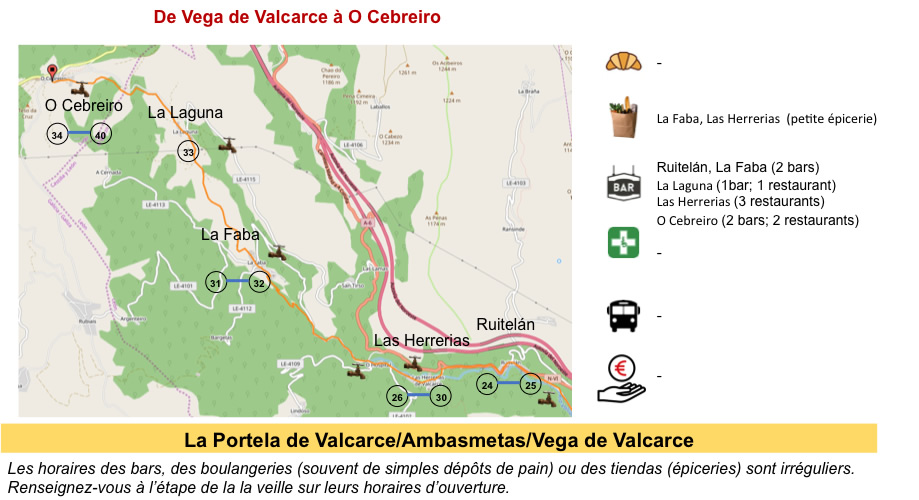

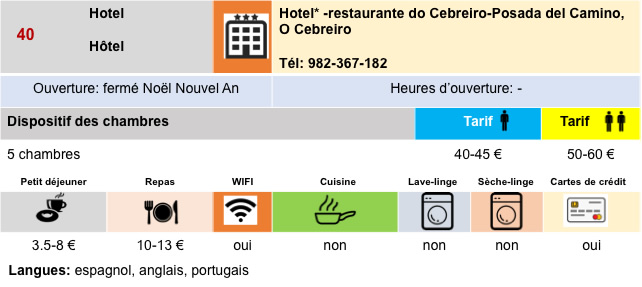

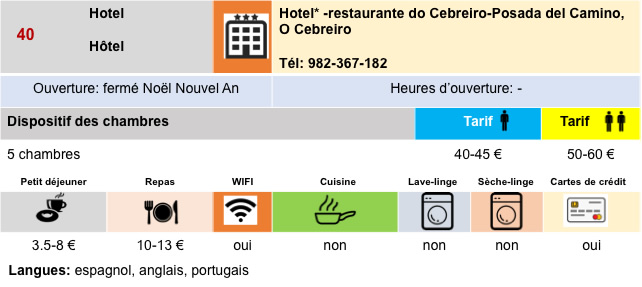

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 9: From O Cebreiro to Triacastela |

|

|

Back to menu |