In the splendor of the Galician wilderness

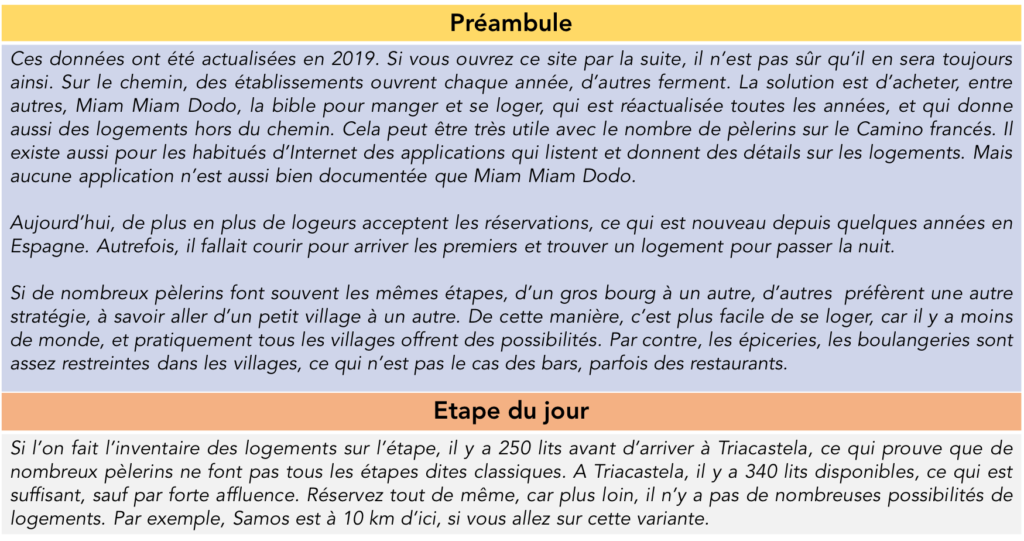

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

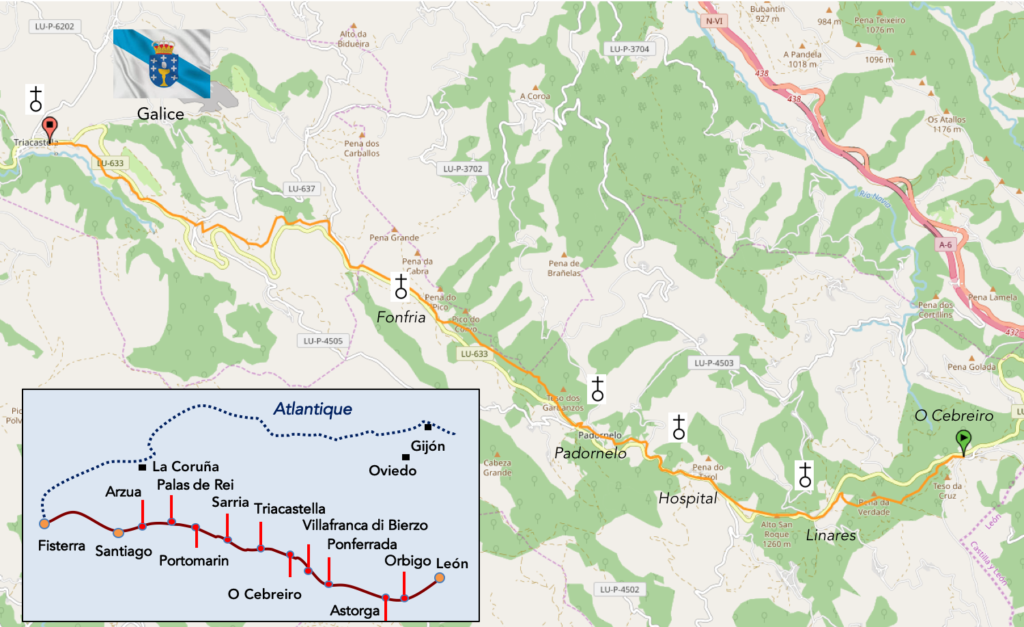

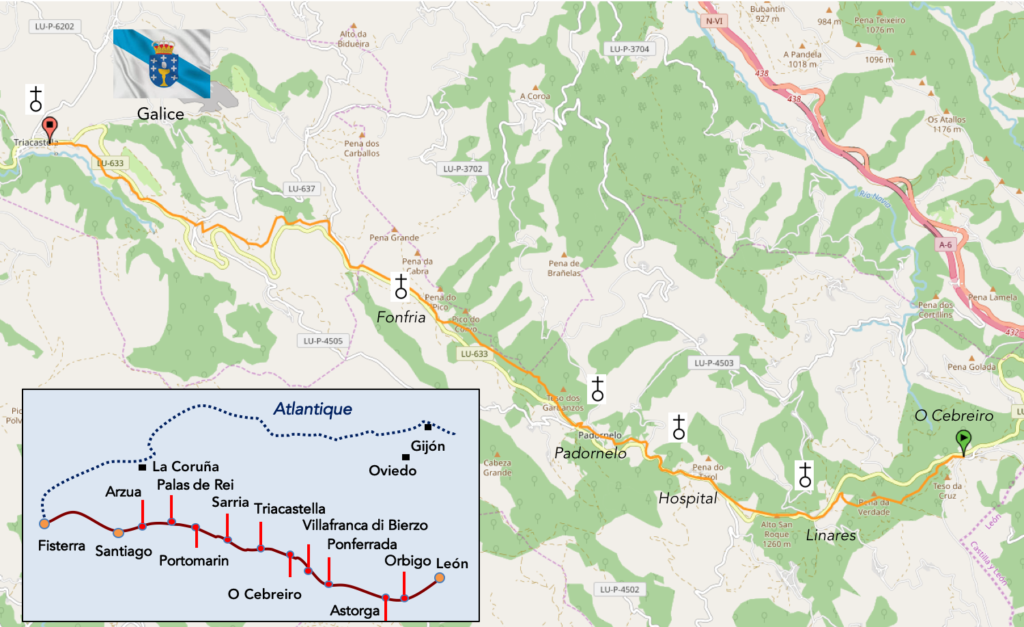

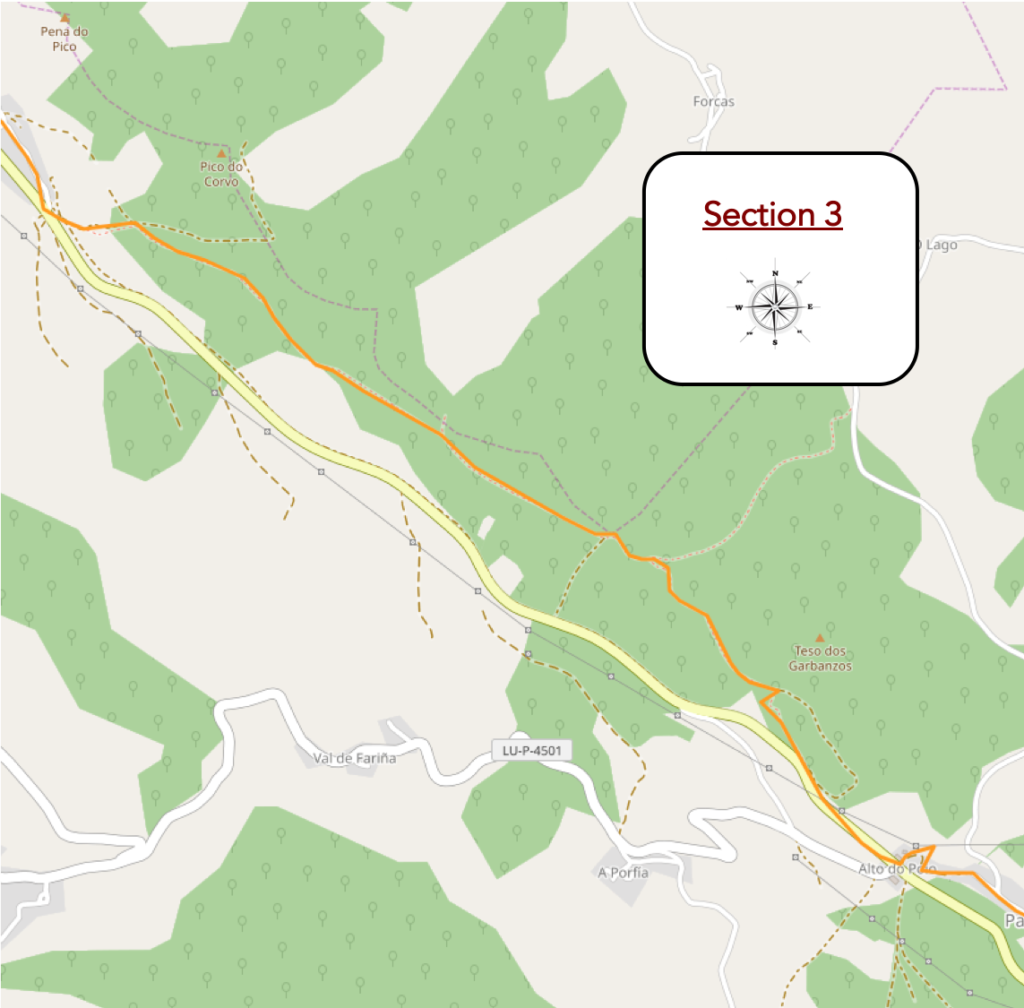

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-o-cebreiro-a-triacastela-par-le-camino-frances-43324277

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Galicia entered a period of instability favored by the invasion of the Germanic peoples. The first to settle were the Swabians, who later clashed with the Visigoths for control of the territory. After the Visigoth domination, which constituted the first Kingdom of Galicia, and the passage of Muslims who settled here little, except to collect taxes, Galicia passed under the control of the King of Asturias. It was in the IXth century, during the reign of Alfonso II of Asturias, that the supposed sepulcher of the apostle St. James was discovered, a fact that would determine the future of Galicia and the pilgrimage route that extended all over Europe. It was also at this time that Alfonso III drove out the Muslims and took possession of all of northern Portugal and part of Castile.

A fierce struggle for the throne of Galicia began with the death of Alfonso III the Great. Galicia gradually passed under the control of the Kingdom of León. The Kingdom of Galicia lost its independence, even came to be divided into counties between several families, dividing the north of Portugal. In the XIth century, the first archbishop of Santiago ordered the construction of a cathedral to preserve the supposed remains of the apostle Saint Jacques. Then, in the XIIth century, the Crown of Castile incorporated the kingdoms of León and Galicia. Although its independence was diminished, Galicia did not lose its title of kingdom. But the government posts remained occupied by Castilian nobles. In the XIVth century, a new conflict of succession brought the kingdoms of Galicia and Portugal closer together, the Galicians preferring to be governed by Fernando de Portugal rather than by the Castilians. But, the stranglehold of Portugal did not last long, and Galicia regained the power of Castile. There was then in the XVth century, a very important social uprising known as the revolt of Irmandiña. The abuses perpetrated by the nobles and the Church, as well as bad harvests and epidemics, pushed the people, as well as the lesser nobility and certain members of the clergy, to rebel against the power. The aim of the attacks was not so much to kill the lords, but to destroy all their possessions in order to expel them. This is why there are few medieval castles left in Galicia and many of them suffered significant damage.

The Kingdom of Galicia therefore entered the modern era under the Castilian crown, although it tried many times to have complete independence. One of the most striking phenomena in the history of Galicia has been the massive migration to the American continent. From the end of the XVIIIth century until the XXth century, this migratory fact continued. We call Kingdom of Galicia, this long period, which goes formally from the Vth century to the XIXth century. In 1833, the regent Marie-Christine signed the decree dissolving the kingdom. Then, Galicia ceased to be a politico-administrative entity. Nevertheless, it continued to evolve with its cultural, economic, social and political particularities. In 1936, she voted by referendum a project of autonomy, but this project did not have time to be implemented, because of the Civil War. During the war, Galicia found itself on the side of the nationalists. During the dictatorship of Franco, a native of Galicia, the autonomous status of Galicia was annulled, as were those of Catalonia and the Basque provinces. The Franco regime also suppressed all measures in favor of the Galician language, although its use was never prohibited. During the last decade of the Franco era, there was a revival of nationalist sentiment in Galicia. On the death of Franco, the new institutions resulted in the status of autonomy, as for the Basque Country or Catalonia.

Today, it is one of the most beautiful stages of the Camino francés, through stunning landscapes, in the wild nature. We ask for more.

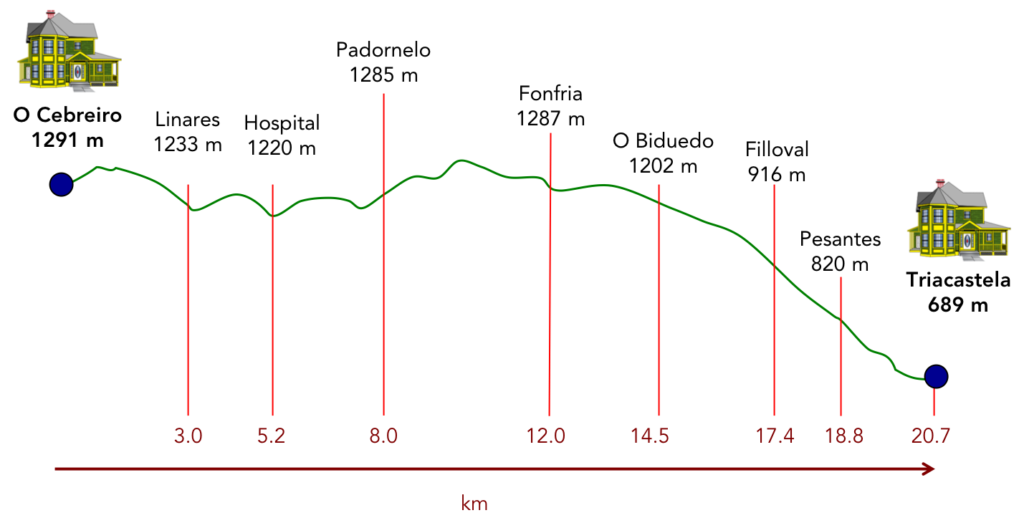

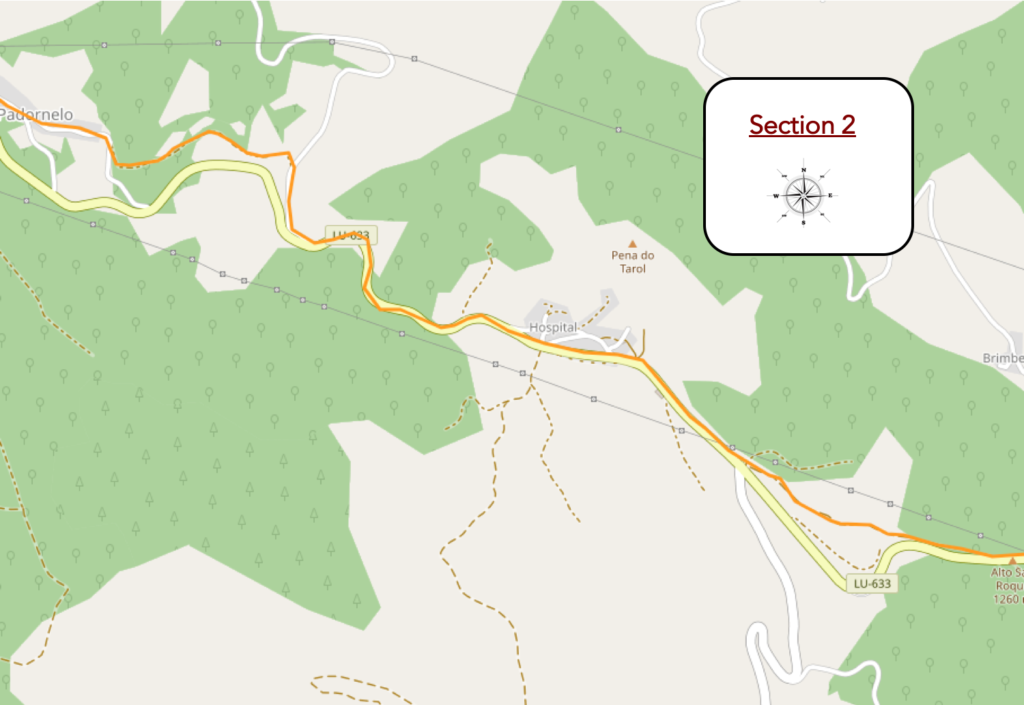

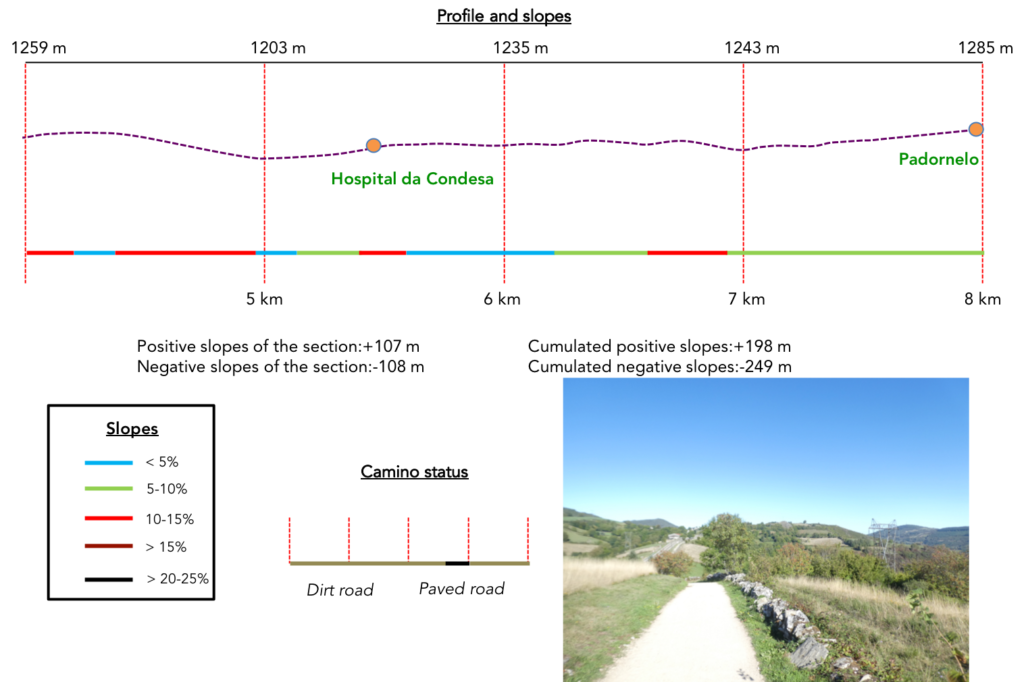

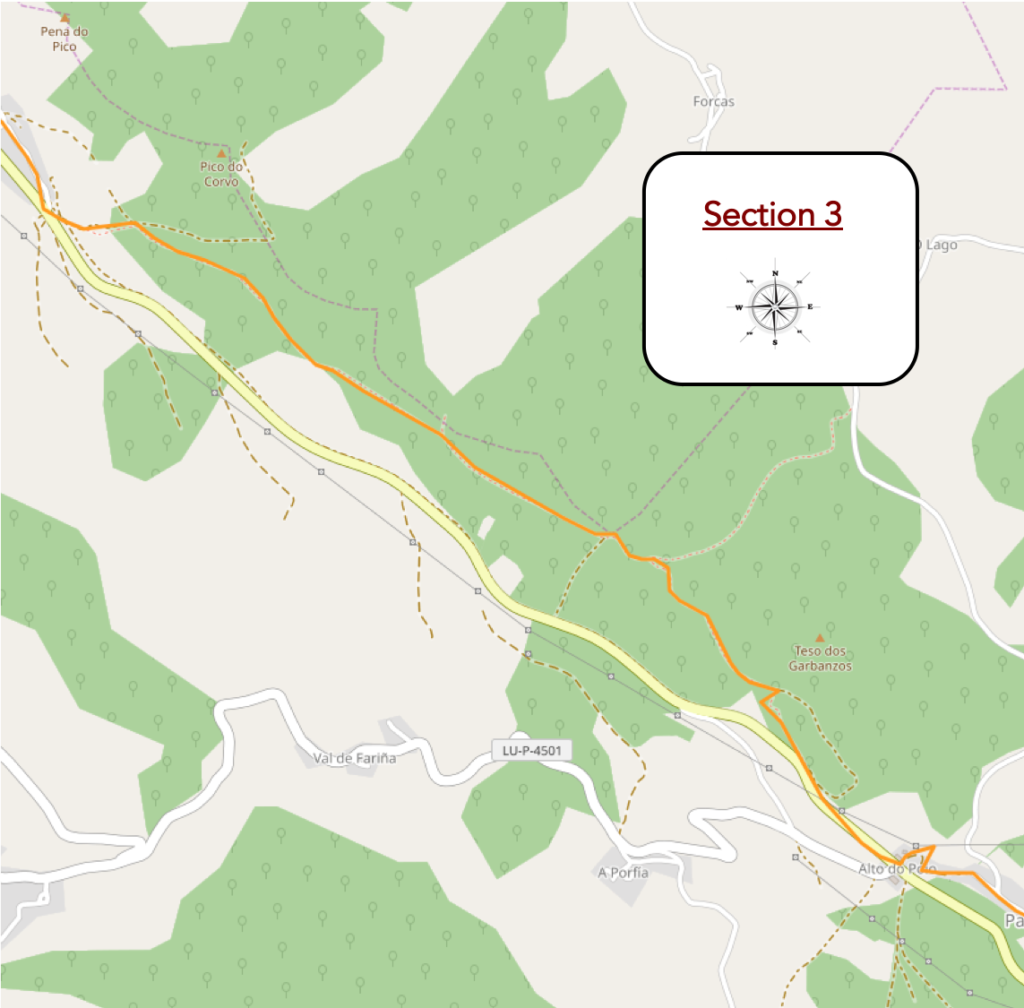

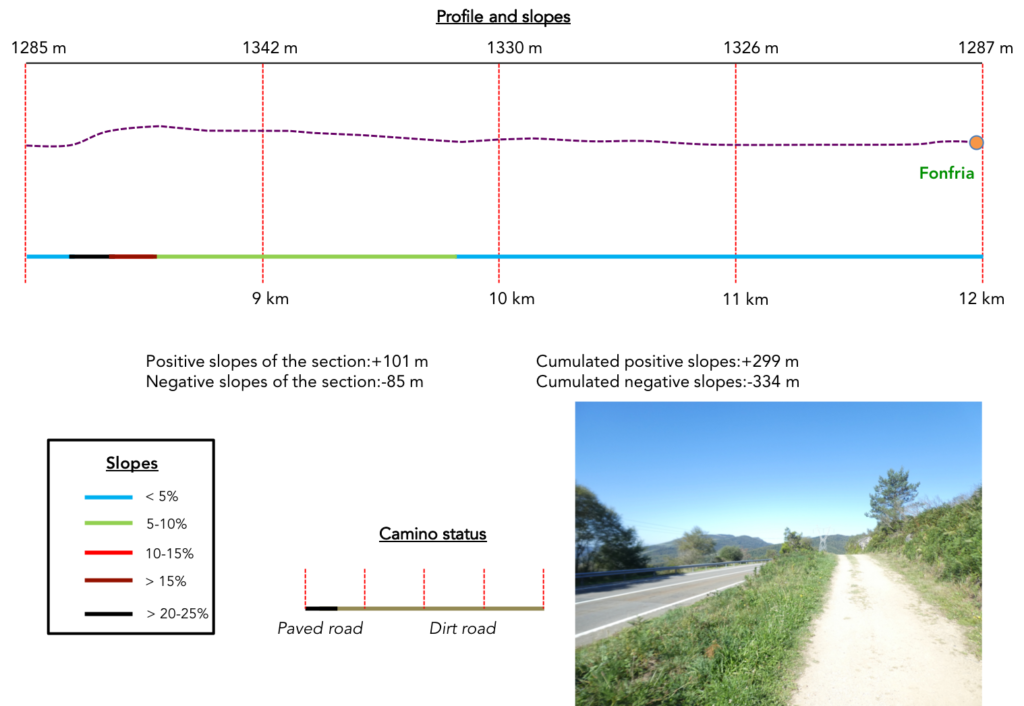

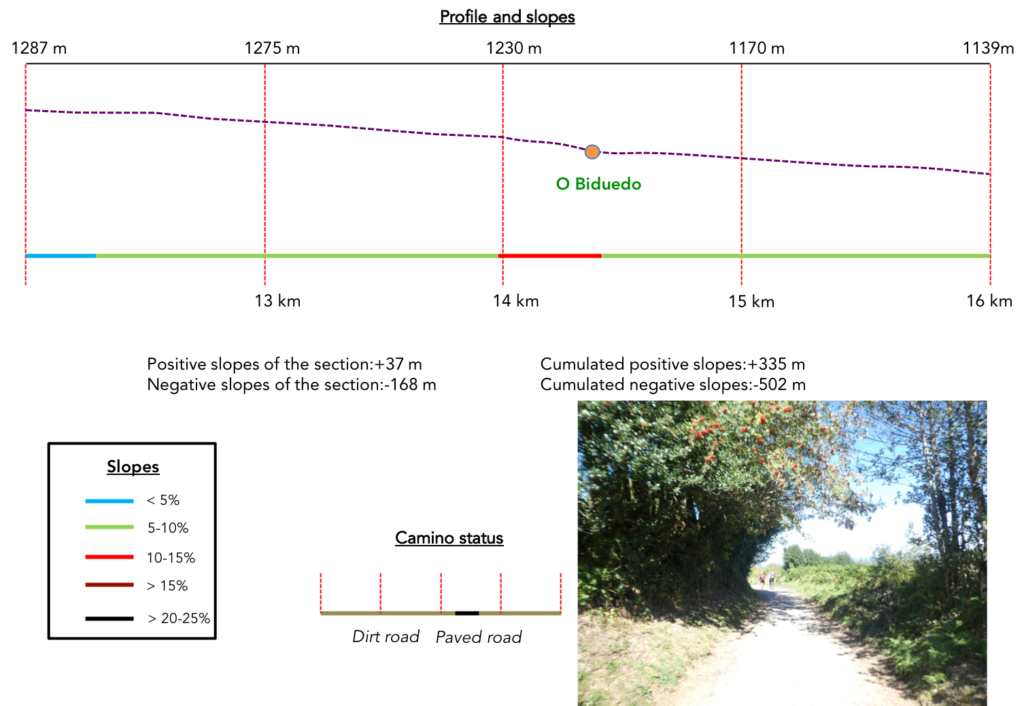

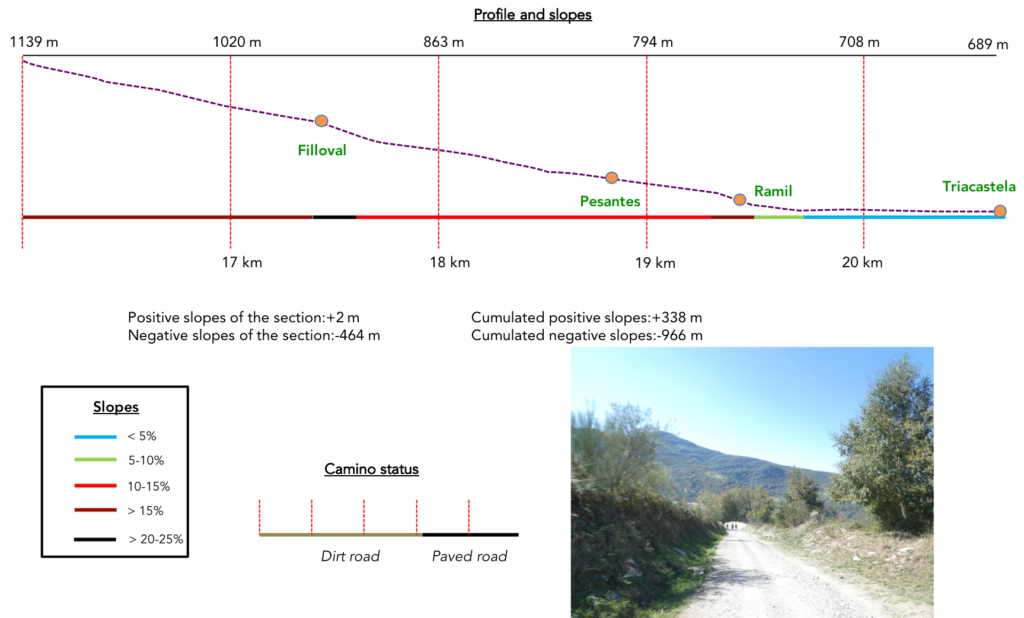

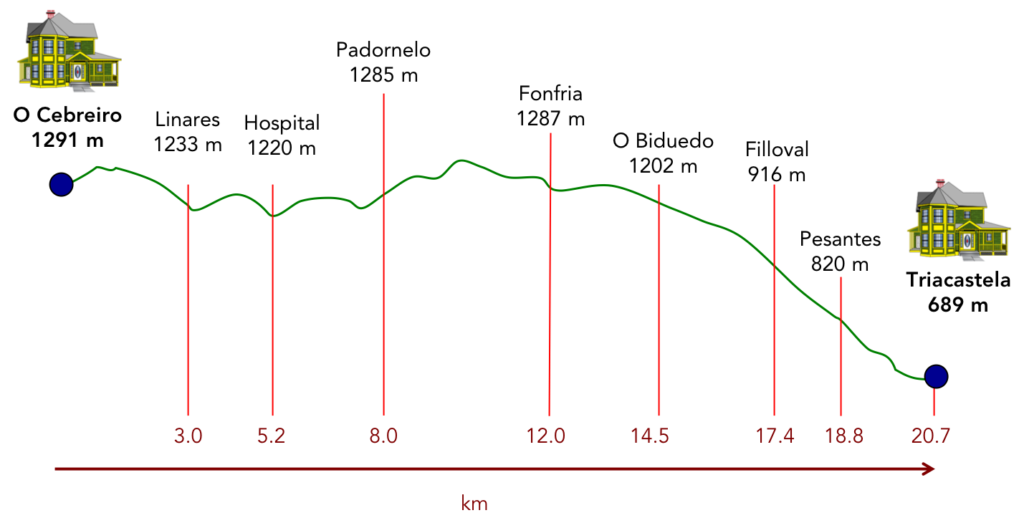

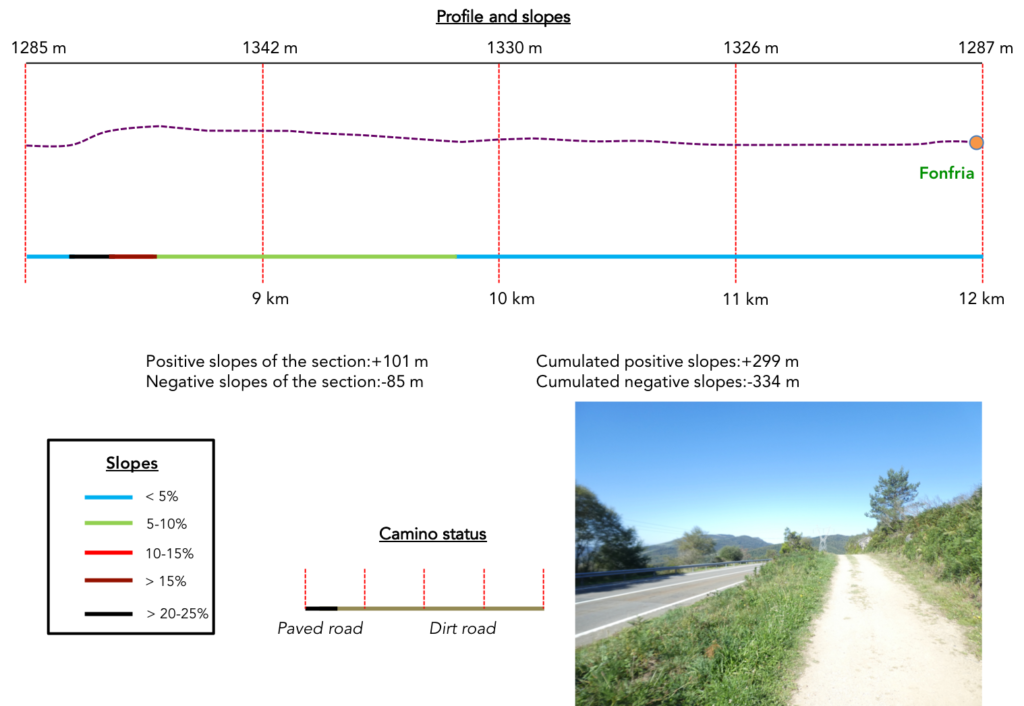

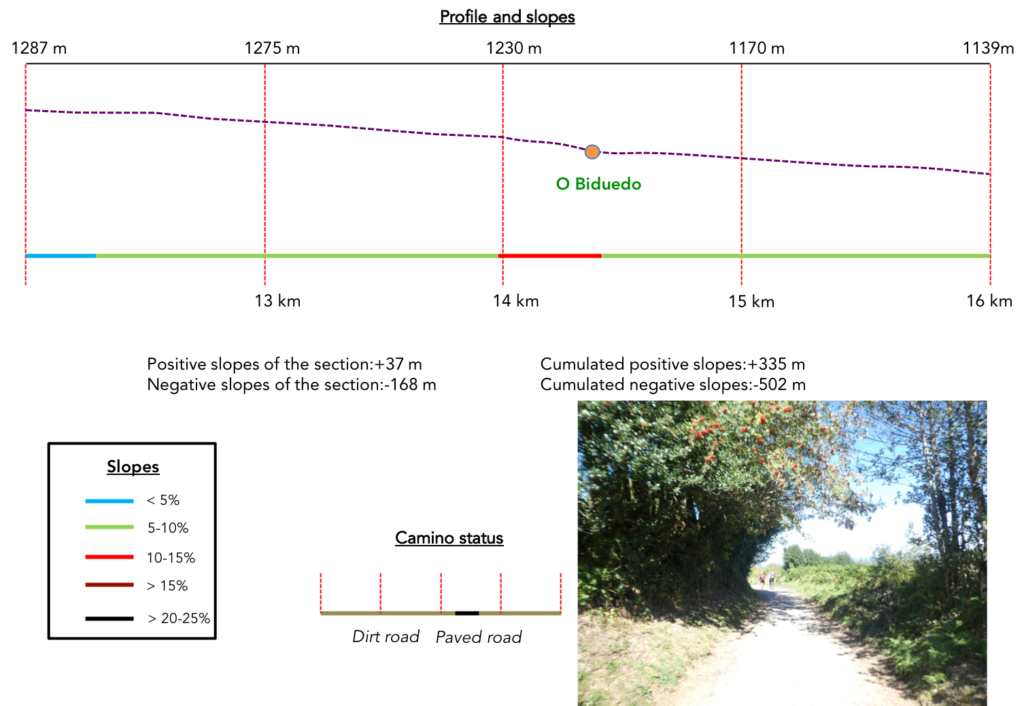

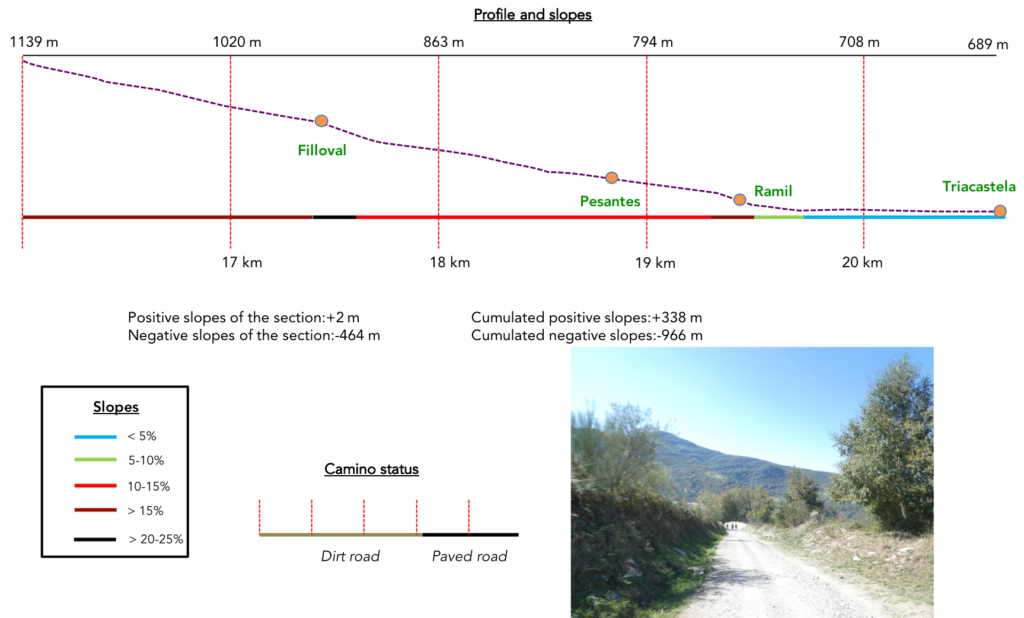

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations today (+338 meters /-966 meters) are very pronounced for a stage of only 20 kilometers. The course plays ups and downs in the first 12 kilometers. There are severe hillocks, both downhill and uphill, especially near the hamlet of Padornelo. Beyond Fonfria, the descent is gradual to end in a rather demanding way at the end of the stage.

In this beautiful stage, the pathways are very clearly to the advantage of the pilgrim:

- Paved roads: 3.7 km

- Dirt roads: 17.0 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

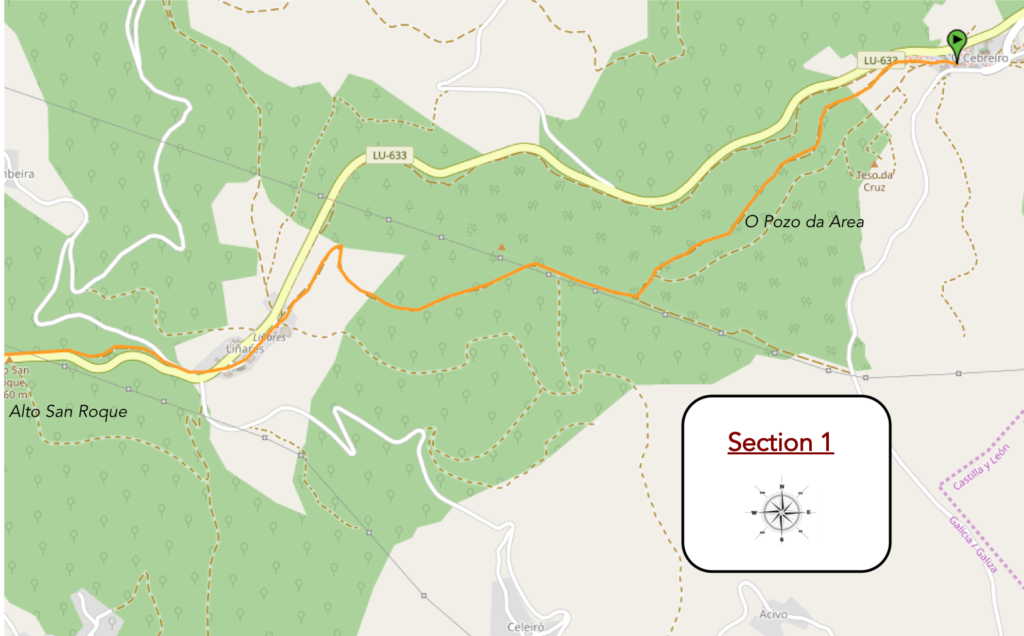

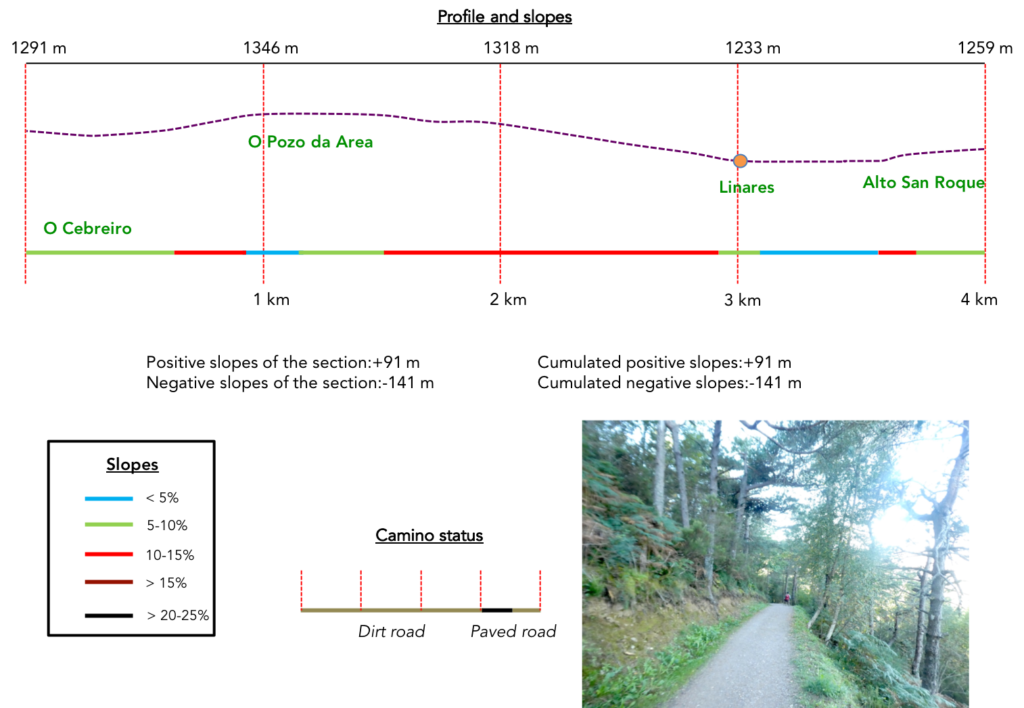

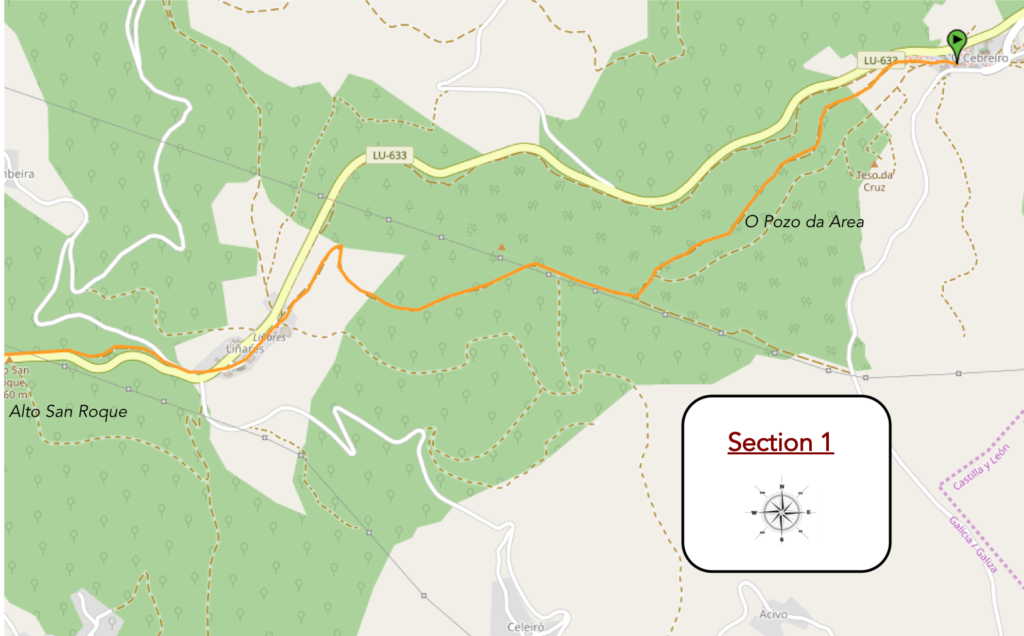

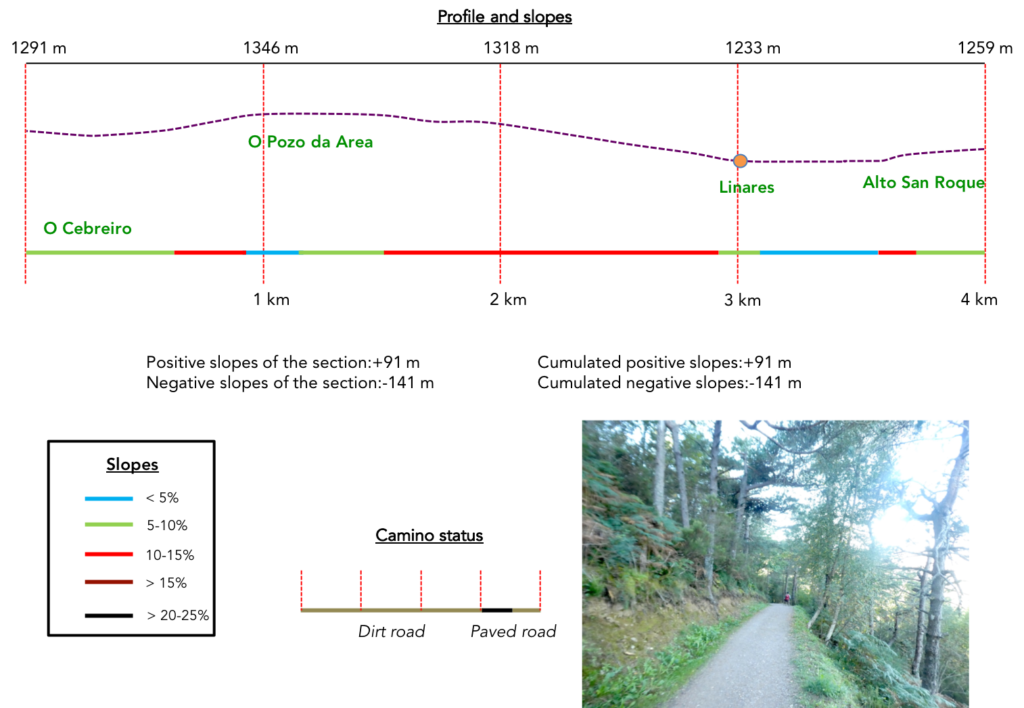

Section 1: On the way to Alto San Roque.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: rather pronounced ups and downs.

| This morning, the weather is nice in Galicia. The Camino leaves the beautiful village of O Cebrero on the slabs. |

|

|

The pathway runs above the pass road. Your gaze is lost below on the gentle hills beyond the Montes de León. Very far, the national road that you had taken the day before passes over bridges. Do you think you see the sea? No, it is only fog, so present in the region in autumn. Generally, it dissipates during the day.

| Here, some pilgrims sometimes decide for the road, but you have to walk on the tarmac, because there is no shoulder and sometimes a few vehicles circulate. |

|

|

| Here, the forest is a mixture of conifers and hardwoods, with mostly pines, poplars, oaks and maples. |

|

|

| Below the wild cypresses and boxwoods, runs the pass road. |

|

|

| Further down, the gently sloping pathway descends under the majestic and very twisted pines. |

|

|

| Track organizers don’t mess with safety on the Camino. Here, they even put up safety barriers, because a trickle of water flows there from time to time. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway slopes up in the woods. |

|

|

| Nature is deliciously gentle and wild on the trail. |

|

|

| Gradually the conifers fade to give way to hardwoods. When the country opens up, you almost always see the ash trees appear, trees of light. |

|

|

| Here a cyclist passes near the pilgrim milestone. In Galicia, as in Castile, the pilgrimage terminals are omnipresent, but many pilgrims do not read the mileage, do not want to know how many kilometers separate them from Santiago. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway descends on a steeper slope to approach the pass road again. |

|

|

| Then, the wood gradually lightens… |

|

|

| … to arrive in sight of the hamlet of Liñares do Cebreiro, on the road to the pass. |

|

|

| The village is already mentioned in the VIIIth century, due to its belonging to the monastery of O Cebreiro and its royal foundation. Here, there is a beautiful fountain where the water from the mountain flows. |

|

|

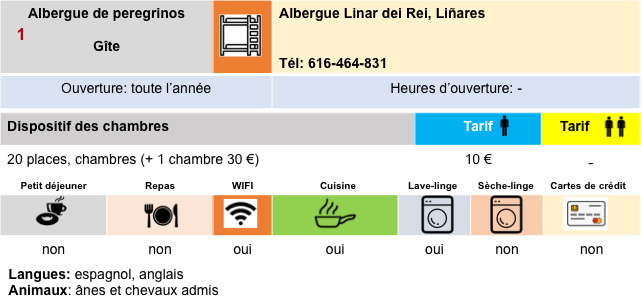

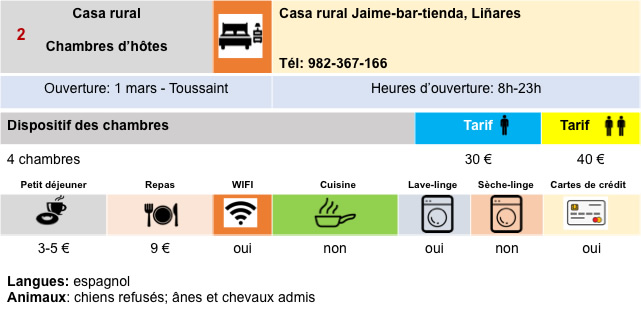

| The village is also mentioned in the Codex Calixtinus under the name of “Linar de Reges”, the name evoking the flax plantations of the region, grown for the looms. It is said that the Romans used Galician linen for their ships. There were also houses with thatched roofs here, which have disappeared. You can stay in the village, which is not negligible, accommodation being rare in these remote countries. |

|

|

| There is some livestock farming in the country. The Romanesque church of San Esteban resembles the church of Santa María de O Cebreiro, with a rectangular nave and a square tower. In the Middle Ages it belonged to the monastery of O Cebreiro. Some sources say that this church was from the VIIIth century; others place its construction in the XIth century. But it was restored later, and again recently in the XXth century. It is closed with an iron door. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino leaves the road of the pass to engage on a small paved road, which slopes downhill towards a neighboring hamlet. |

|

|

| But quickly, it leaves the tarmac to slope up in the hardwoods on a dirt road. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope becomes steep to return to the pass road. Here, the Camino constantly plays with the road. |

|

|

| Further afield, it arrives at Alto de San Roque, at an altitude of 1,270 meters. |

|

|

The Pilgrim’s Monument is a 1993 bronze statue of a medieval pilgrim struggling against the wind, leaning on his staff and holding his hat. It is about 4m high. The sculpture is titled “Luchando contra el viento” (Struggle against the wind). It is one of the most photographed sites on the Camino. It is easily understood.

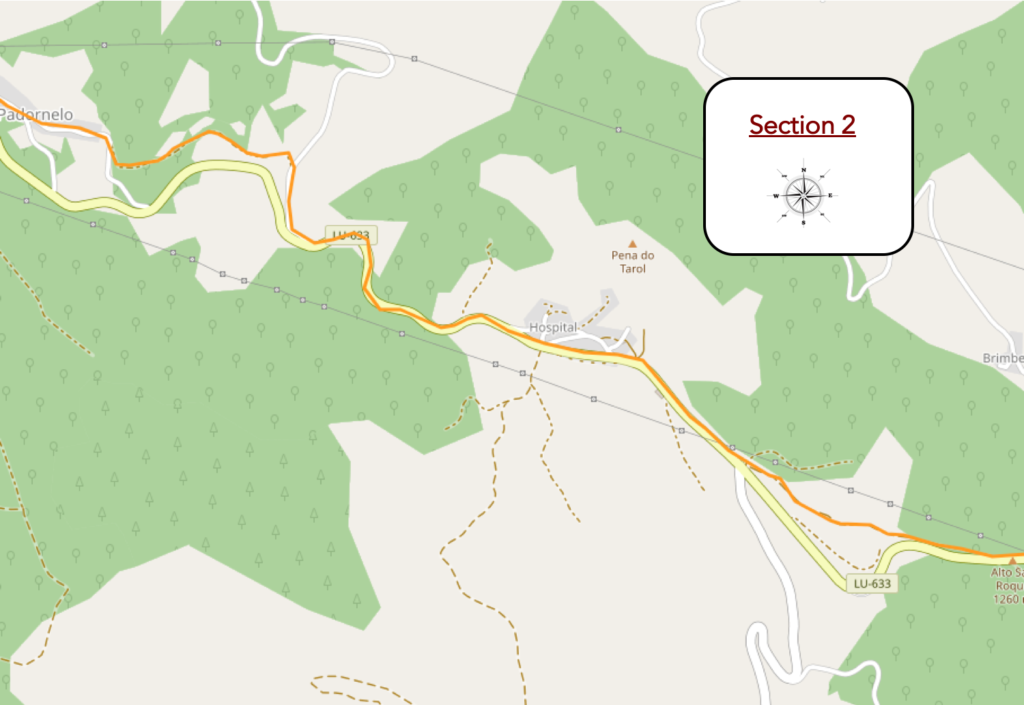

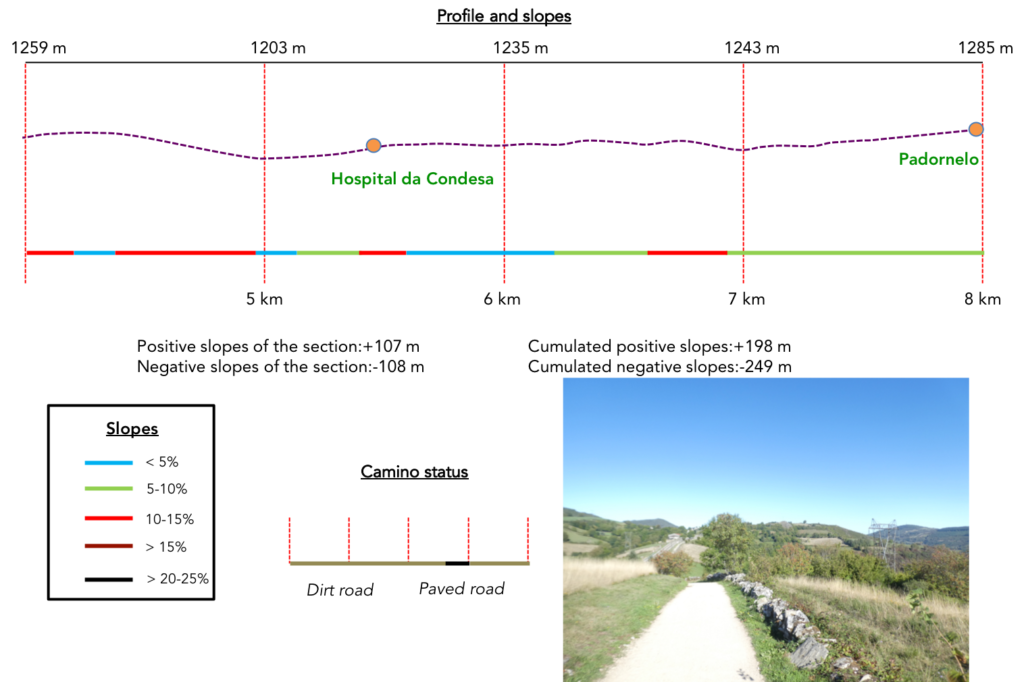

Section 2: Over hill and dale under the pass road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: rather pronounced ups and downs.

| Beyond Alto San Roque, the Camino climbs further into the wilderness. Wherever you look, it is only scrubland, ferns, small wooded hills that follow one another on the horizon. |

|

|

| It is easy to see that humans do not have much to cultivate in this thankless, but so beautiful nature. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway descends from the hill. Here, in the middle of the oaks grow ashes, mountain ash and stunted chestnut trees. |

|

|

| Soon you can see the village of Hospital de Condesa in front of you. |

|

|

| The presence of small walls of large stones still indicates a certain agricultural life. The base stone of Galicia is granite or transformed metamorphic rocks, such as schist or gneiss. But, there are also often limestones which outcrop with which people also make low walls. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway finds the road to the pass back… |

|

|

| … and heads towards the village, parallel to the road, gently sloping at first, then more steeply sloping. |

|

|

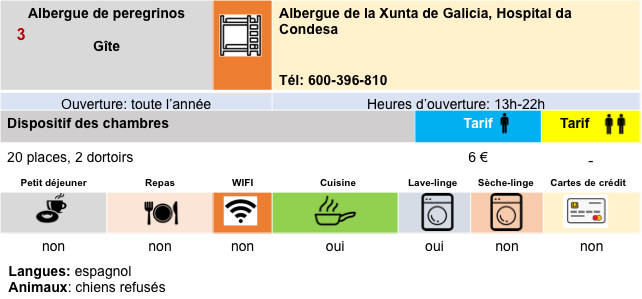

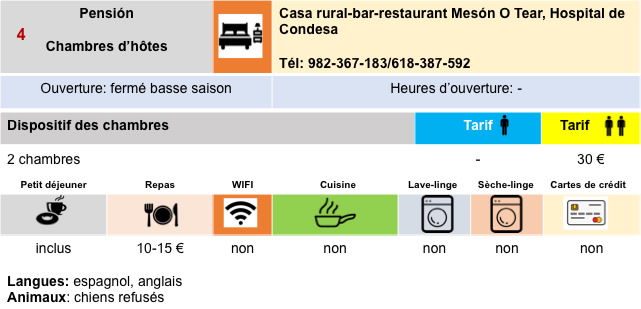

| The village of Hospital do Condesa once housed a pilgrim hospital built in the XIth century, reputed to be one of the first ever built for Christian pilgrims on the way to Santiago. It belonged to the jurisdiction of O Cebreiro. The only vestige of the hospital is the name of the village. It is a magnificent and solid granite village cut in the mass. |

|

|

| On the Camino, there are many water points in the villages, unlike the French Way. The Romanesque church of San Xoán (Saint John) was also dedicated to San Roque. It was linked to the order of Saint John of Jerusalem, then to the Order of Malta. |

|

|

The church is potentially XIIth century, but the church you see today is almost entirely the product of a late XXth century restoration. It is built in granite, with raw stones from the fields. Like the other churches in the region, it has an austere Romanesque style and has a tower with an external staircase crowned by a stone dome. A cross of Santiago surmounts this tower.

| The Camino comes out of the village under the maples to find the road to the pass. |

|

|

| It is then the return of the traditional “senda de peregrinos”, which haunted you so often in the long crossing of the Meseta. Here, the trees will hardly shade you. |

|

|

| It thus lasts more than a kilometer, on a road with little traffic. There is no mandatory reason for cars to pass through the pass to enter Galicia. Further on, the Camino leaves the pass road, to take a small road below. |

|

|

| There are many ash trees, and even hornbeams here, which is rare in Spain. The Camino does not stay on tarmac for long. Soon it slopes back up a dirt road. |

|

|

| The slope is gentle here and the leafy trees provide generous shade. |

|

|

| The vegetation is abundant here on a pathway often surrounded by large stones on the slopes. Further up, the pathway joins a small paved road. |

|

|

| The paved road is very bad to reach the hamlet of Padernelo. |

|

|

Here, cats are probably the most present living beings in the hamlet.

| The hamlet of Padornelo is built exclusively of granite rubble. In the XIIth century, the Bishop of Santiago placed the church under the protection of the Hospitallers of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, who established a priory here, with the mission of serving and defending pilgrims. Nothing remains. The XVth century Church of San Xoán (Saint John) is beautiful and charming with its slate roof and its three-bay bell tower surmounted by a triangular top. |

|

|

Section 3: Again and again under the pass road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: rather pronounced ups and downs.

| The pilgrim salivates in advance, because he has seen in a not too distant horizon the road, which seems to climb steeply. So, he takes the opportunity to quench his thirst at the fountain. All these fountains on the Camino look alike. They smell of European money. But they are very tasteful. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the Camino leaves the tarmac to begin the climb on a dirt road that winds up the hill. |

|

|

| The pilgrims are sweating profusely. Cyclists too, who have to get off their machine, like the latter who carries his dog. |

|

|

| The dog turns around the cart, as if to encourage its owner. Turning around, to catch your breath, you can still admire the slate roofs of the hamlet lost in the vegetation. |

|

|

| In order not to scare you too much, we will spare you the few switchbacks that the pathway makes on this tough climb. Fortunately, the climb is not eternal to reach the pass road.. |

|

|

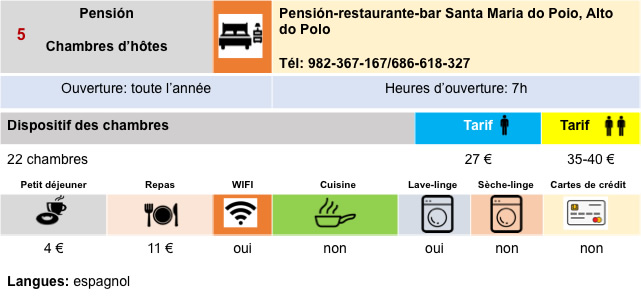

| The Alto do Poio (1,337 m) is the highest point of the French Way in Galicia. In medieval times there was a hermitage on this hill and even the church of Santa María del Poyo that belonged to the Hospitallers. There remains only the bar and the restaurant where many pilgrims stop after the effort. |

|

|

You will occasionally come across passenger transport vehicles on the Camino. These are people who walk part of the route and then get transported. Many parallel circuits are possible, such as splitting the trip, having the bag transported, spending the night in hotels. There are walkers who no longer support a back load, or who do not close their eyes, opportune as they are by the promiscuity of the snorers present in the lodgings.

| Beyond the pass, it is again the traditional “senda de peregrinos” and its vicissitude, even if the landscape here is far from ordinary. |

|

|

| The vegetation is divided between small deciduous trees, bushes and pines. There are even altitude pines here (Pinus cembra in Spanish), high altitude trees. |

|

|

Further down, you will see Triacastela, nestled in the greenery at the bottom of the valley. But you are far from done.

| Here, the ground is almost sand. Ferns, wild cypresses, laburnum and lavender still grow on the slopes. |

|

|

| The mountain ash trees still have a place in this scrubland, which extends ever further over the surrounding hills. |

|

|

| Sometimes a pilgrimage milestone punctuates the walk. |

|

|

| Sometimes, rare meadows give way to scrubland. Here, you can see some Galician cows grazing the grass there. These are often Rubia galega cows. This breed is considered a must in gastronomy. The major asset of this meat is the high but harmonious concentration of intramuscular fat commonly known as marbling. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway diverges a little from the pass road… |

|

|

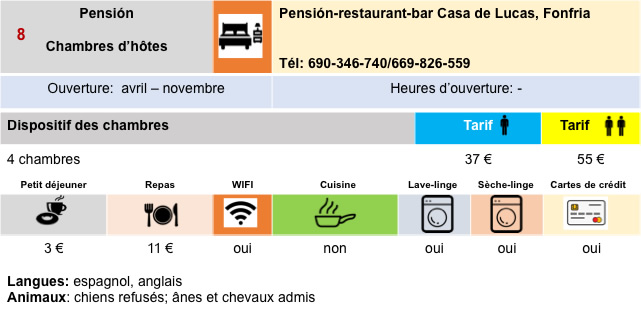

| …to arrive at Fonfría, a small typical Galician village that smells of the countryside. |

|

|

| It owes its name to fons fría (cold spring), which still exists in front of the parish church. Until the end of the XIXth century there was a pilgrim hospital dedicated to Santa Catarina, managed by the Order of Saint John, but it no longer exists. But if the village smacks of good cattle, it also smacks of pilgrimage. |

|

|

The church of San Xoán (Saint John) comes from the XIIth century, rebuilt in the XVIth century, then it underwent several transformations, the last dating back to the last century. Either way, it is remarkable. The roof is slate. If the facade has been restored, the stones of the door are original. The bell tower, also restored, consists of a single wall pierced with openings for the bells and surmounted by a triangular point. The original appearance has been so well preserved that one must think it was Romanesque.

Section 4: The Camino begins the descent into the valley.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: most often gentle slopes.

| From here to Triacastela, the Camino descends. At the exit of the village, it is no longer the traditional “senda de peregrinos”, because a beautiful path way runs, far from the road. Pretty mossy stonewalls brighten the pathway in the middle of the cows. They are still Rubia galega, but there are also other breeds, crosses perhaps. Only the discerning eye of a Galician will be able to identify them. |

|

|

| The pathway sometimes runs through more bare spaces. It is bucolic to the highest degree when the countryside sings like this. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway begins to undulate a little more on the gentle hill. Above your heads swings the power line. |

|

|

| It is clear that the forest had to be cleared one day to make way for the meager meadows used by the few local farmers. Because, as soon as the gaze is lost above the road, it is only dense forests, where man must only stray to collect mushrooms. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway finds the road to the pass back. |

|

|

| The Camino stays on the same side of the road and descends on a small crossroad. |

|

|

| Here, the chlorophyll trickles and casts shade. Almost the entire panoply of hardwoods is present. Only the beeches are missing. |

|

|

| Further down, the Camino leaves the axis to take a dirt road that runs towards O Biduedo. |

|

|

| There are again rowan trees in abundance and the embankments are lined with tall ferns. |

|

|

| But another species proliferates here: the birch. The name of O Biduedo comes from the large number of birches (abedule, in Spanish; betula in Latin and Portuguese). But poplars are also numerous. |

|

|

| The slope is more pronounced in the birches to reach the hamlet. |

|

|

| People who live here must not be very numerous, probably less than fifty. The hamlet is unlike any other in the region. The buildings are more modern. The church of the hamlet is the old hermitage of San Pedro. |

|

|

| There are still a few stone houses, more recent youth, and cattle are often present in the sloping meadows around the village. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the pathway still flattens under the trees, on a straight line. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway turns to the other side of the valley. In the plain, you guess a large quarry. This quarry is one of the founding myths of the Camino Francés, which nowadays has been abandoned. The quarry is a rare source of Galician calcium and lime, granite being the basis of Galicia. This limestone was used for the construction of the Cathedral of Santiago. In the XIIth century, pilgrims collected stones rich in calcium and brought as much of these materials as possible to the lime kilns of Castañeda, a village located further along the route, almost 100 km between Arzúa and Melide, where they were baked. and transformed into mortar for the cathedral, which was transported to Santiago. In this way, each pilgrim could feel that he had contributed to the construction of the place where the saint rested. |

|

|

| The Camino then descends on the narrow pathway, gently sloping, in the green scrubland. It’s just beautiful over here. |

|

|

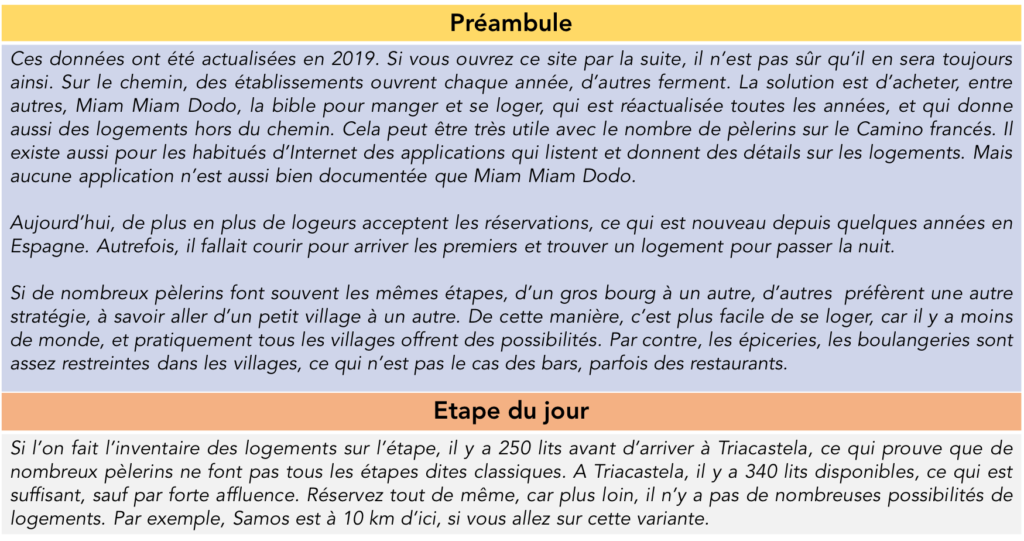

Section 5: Descent to Triacastela.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: very steep slopes most of the time.

| At some point, the slope will change percentage. This is the steepest part of the descent. And it will sometimes be demanding on the joints and the knees to reach the bottom of the valley. At the start, it is a wide pathway, not very stony, but with a certain grain all the same, which can cause the shoes to slip. But, there is no reason to be tied down. The Camino de Santiago is a track for everyone. |

|

|

| We are at the beginning of autumn, and the cows look like brown spots in the meadows. |

|

|

| The rowan trees are still there, offering their color palette. |

|

|

| It’s quite classic when the slope is steep, both uphill and downhill, the groups of pilgrims tend to merge. |

|

|

| Further down, the rooftops of Filloval appear below. |

|

|

| In front of you, the valley is still as rough, as deep, and on the way the slope does not decrease in any way. |

|

|

| When you reach Filloval, you’ve almost done the demanding part. |

|

|

| Here awaits an uninviting Australopithecus. |

|

|

| At the exit of the hamlet, the Camino takes a few steps on the tar… |

|

|

| … before finding a hollow pathway with a very steep slope that descends into the undergrowth. |

|

|

| The steep slope does not last long, and the pathway takes fresh air under the majestic oaks and the sumptuous chestnut trees hat have taken up residence here. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope decreases further, between 10% and 15%, and the line of pilgrims forms and threads through the undergrowth. It is as if all the pilgrims had agreed to arrive at the end of the stage at the same time. Which is rarely the case. |

|

|

| Then, the Camino approaches the pass road again and crosses it… |

|

|

| … to take the dirt road a little further, below the road. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway heads to Pasantes. |

|

|

In these small peasant villages, it is not wealth that characterizes them, but the old stones are still their poetry. The tiny hermitage along the way is intangible proof of this.

| Dans ces petits villages de paysans, ce n’est pas la richesse qui les caractérise, mais les vieilles pierres en sont encore la poésie. Le minuscule ermitage a bord du chemin en est une preuve intangible. |

|

|

| On leaving the village, the Camino enters what the Galician people call a corredoira, in fact a corridor bounded by granite stones under the trees. This type of pathway will become familiar to you until Santiago. It is a bit like the tracks of the Causses on the French route. |

|

|

| This pathway is magical, worn to the bone by the soles of pilgrims and the hooves of cows that have passed for centuries. Venerable chestnut trees guard this primitive pathway. There is nothing like an old chestnut tree to lift your soul. |

|

|

| A little further, in a gap, you will see Triacastela in the near horizon. |

|

|

| There are not only sumptuous chestnut trees here. Venerable oaks and beeches also offer you their beneficial shade./td> |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway arrives at Ramil, at the bottom of the very long descent. |

|

|

| Here, almost thousand-year-old chestnut trees guard the place. Poetry, in the sky! Chestnuts are picked in November in Triacastela and throughout Galicia with a festival called Magosto. |

|

|

| Here, European funds may have helped to pave the way, to make it look like a royal alley in the middle of the old stone houses, of which we never know the century. |

|

|

| Leaving the hamlet, the pathway heads back into the corredoira, still just as bewitching. |

|

|

| At the exit of the wood, the pathway disembarks in the suburbs of Triacastela, where the pilgrims, as usual, hasten to pile up in the bars, to celebrate as they should their exploit of the day. |

|

|

| Triacastela (1,000 inhabitants) is a stone’s throw away. Triacastela means “three castles”. The three castles that gave the village its name date from the beginning of the Xth century. All three seem to have been destroyed in the wars against the Norman invaders in the Xth century, and nothing remains of them today. Other experts claim that the name could refer to three castros, in fact forts that surrounded the city. Count Gatón, the rebuilder of Bierzo after the Reconquista, could have founded it in the IXth century but nothing is less certain. This city was an important stopover for medieval pilgrims descending from the mountains, with several hospices and a monastery. Only one of the hospitals remains, which is now used as a private home. |

|

|

The village bears little resemblance to the other villages in the valley. It is more extensive, with many whitewashed houses. Few of the cut stone houses remain in the village.

| Le village ne ressemble guère aux autres villages de la vallée. Il est plus étendu, avec de nombreuses maisons crépies à la chaux. Rares sont les demeures de pierre taillée qui restent dans le village. |

|

|

| The Church of Santiago was built in the Romanesque period (IXth century) but underwent a profound transformation at the end of the XVIIIth century. Its apse is probably Romanesque. Its facade and its unusual bell tower date from the XVIIIth century. We found it closed. |

|

|

| Triacastela remains a stage where accommodation is plentiful and where most pilgrims stop. |

|

|

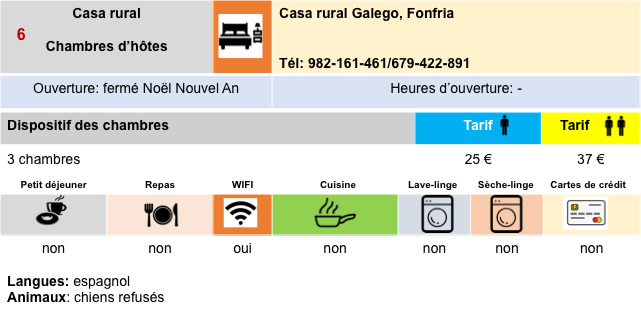

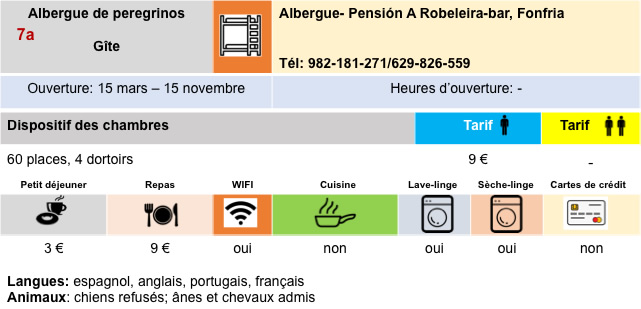

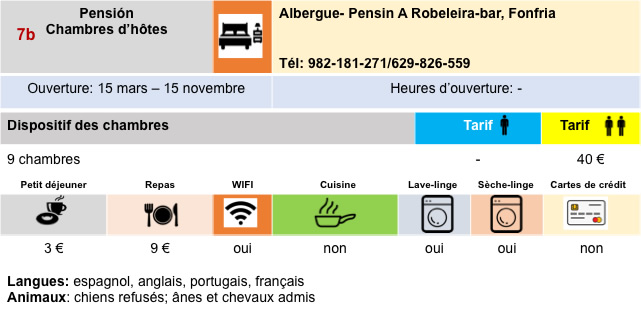

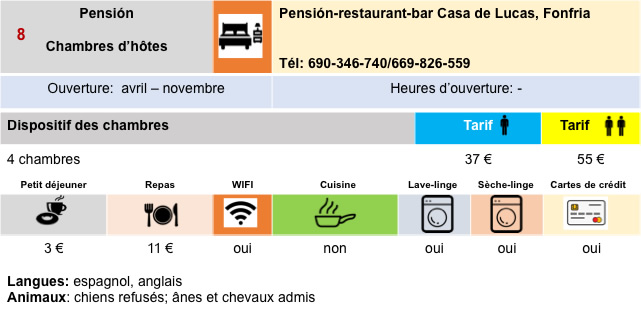

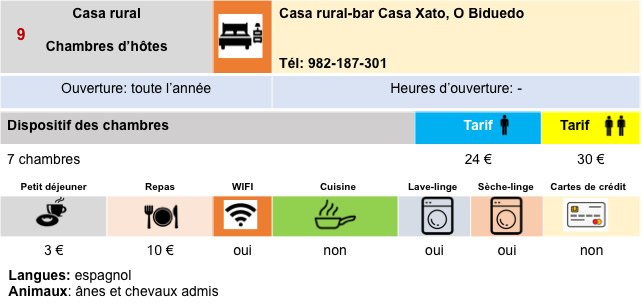

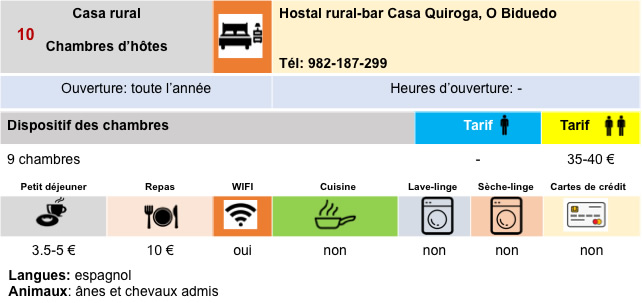

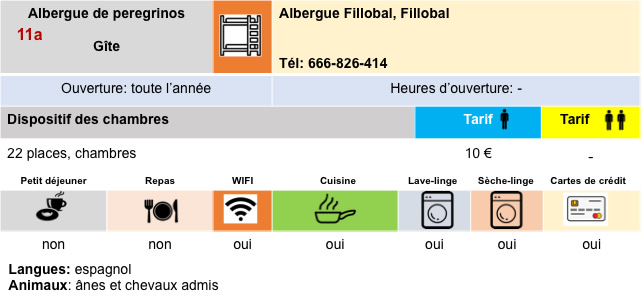

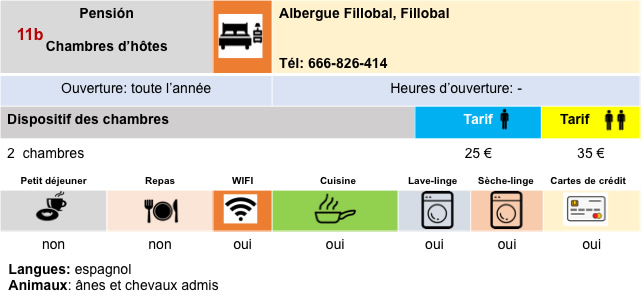

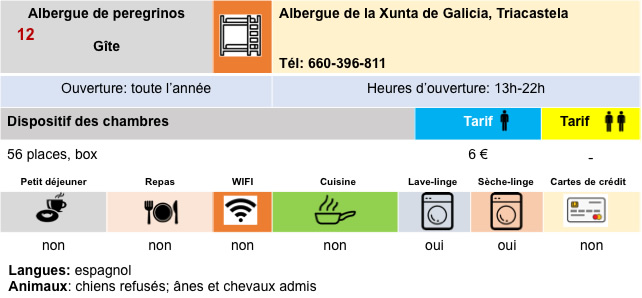

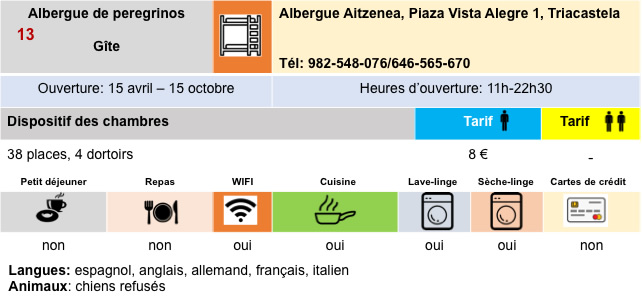

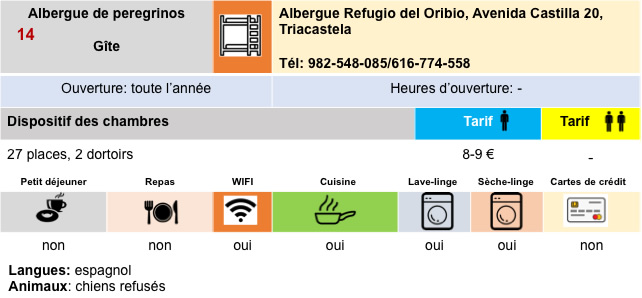

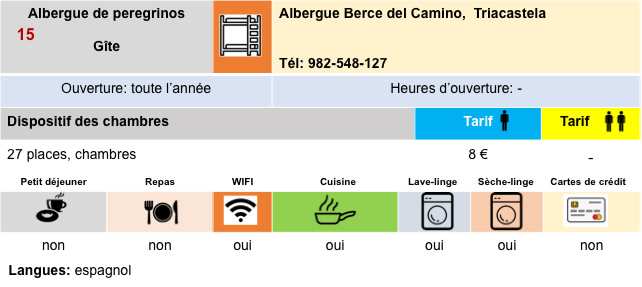

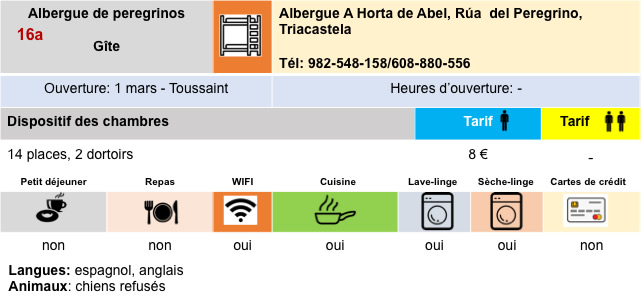

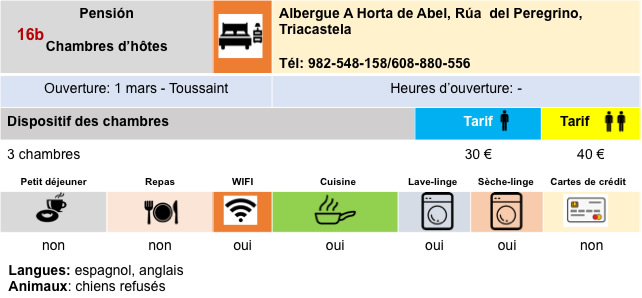

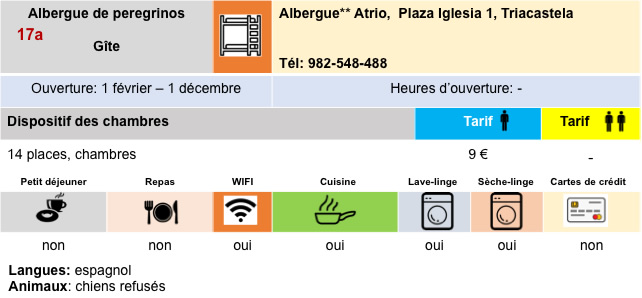

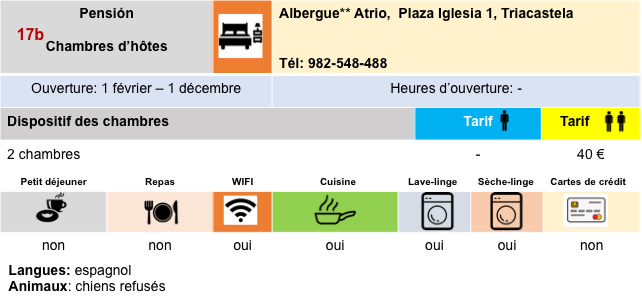

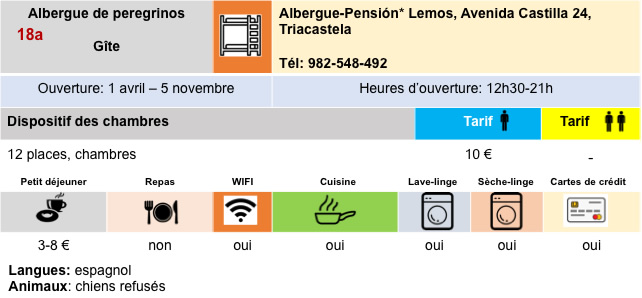

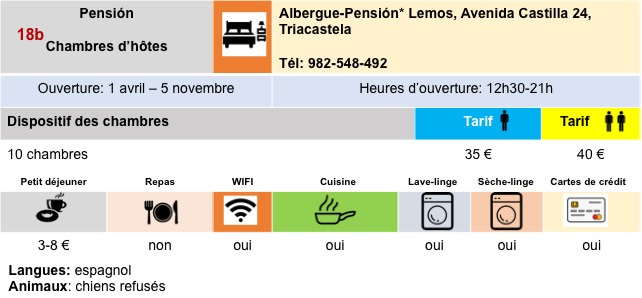

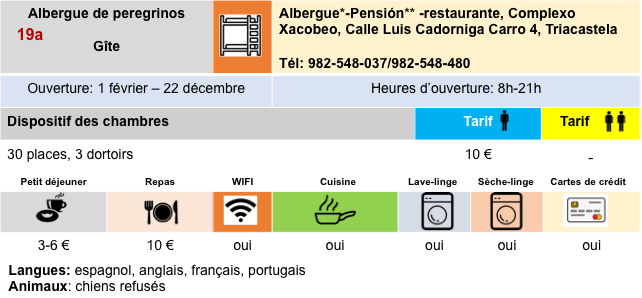

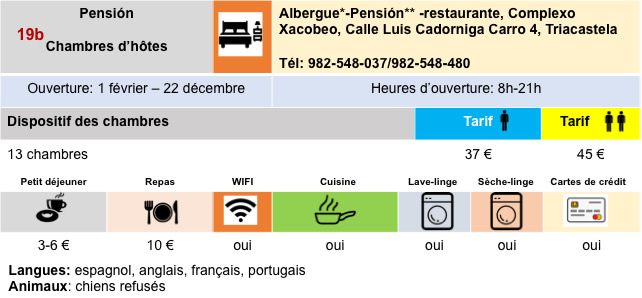

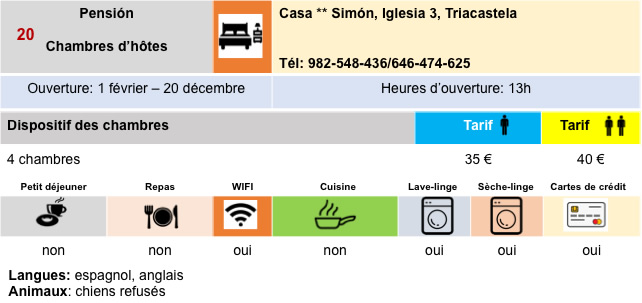

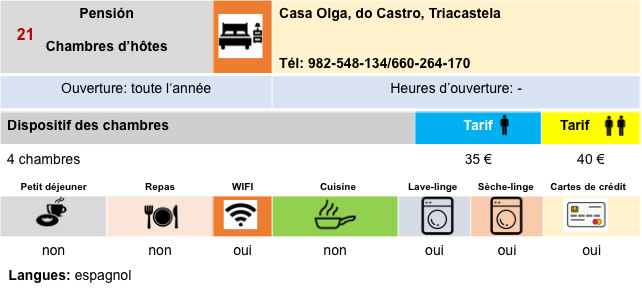

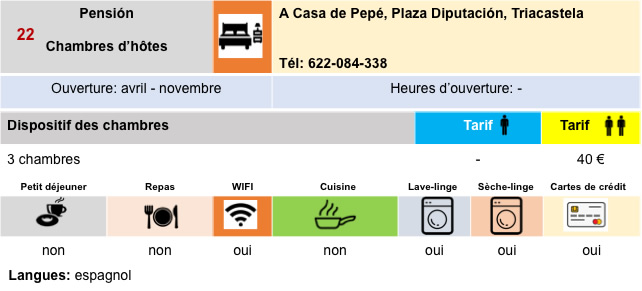

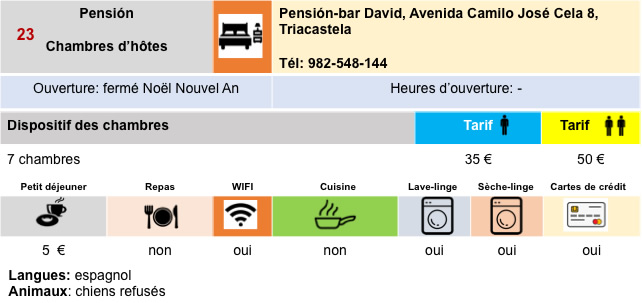

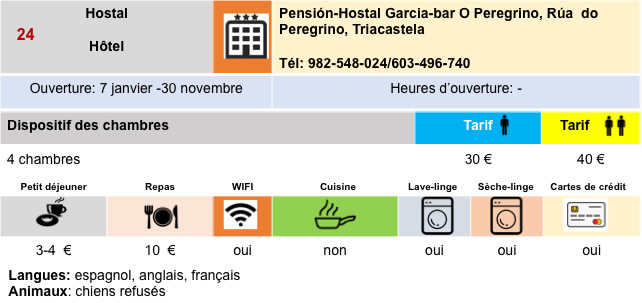

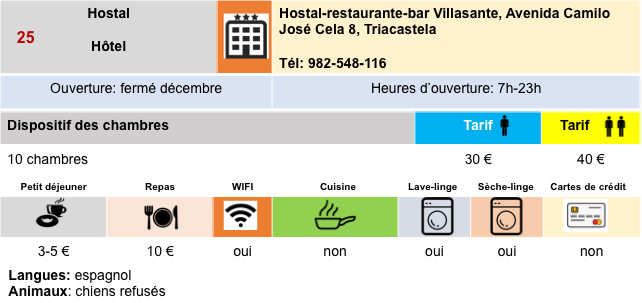

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 10: From Triacastela to Sarria |

|

|

Back to menu |