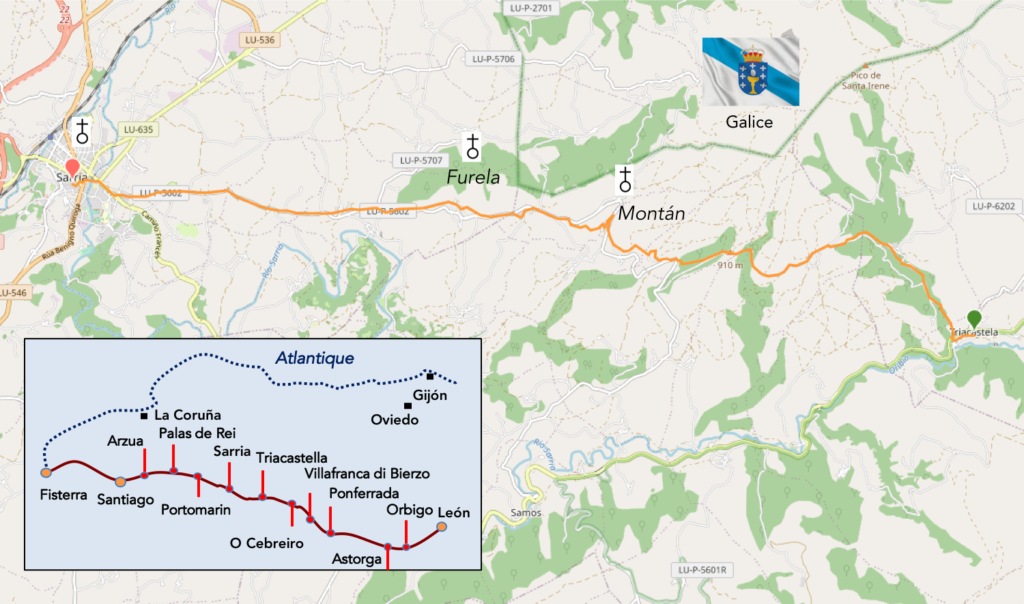

In the province of Lugo

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

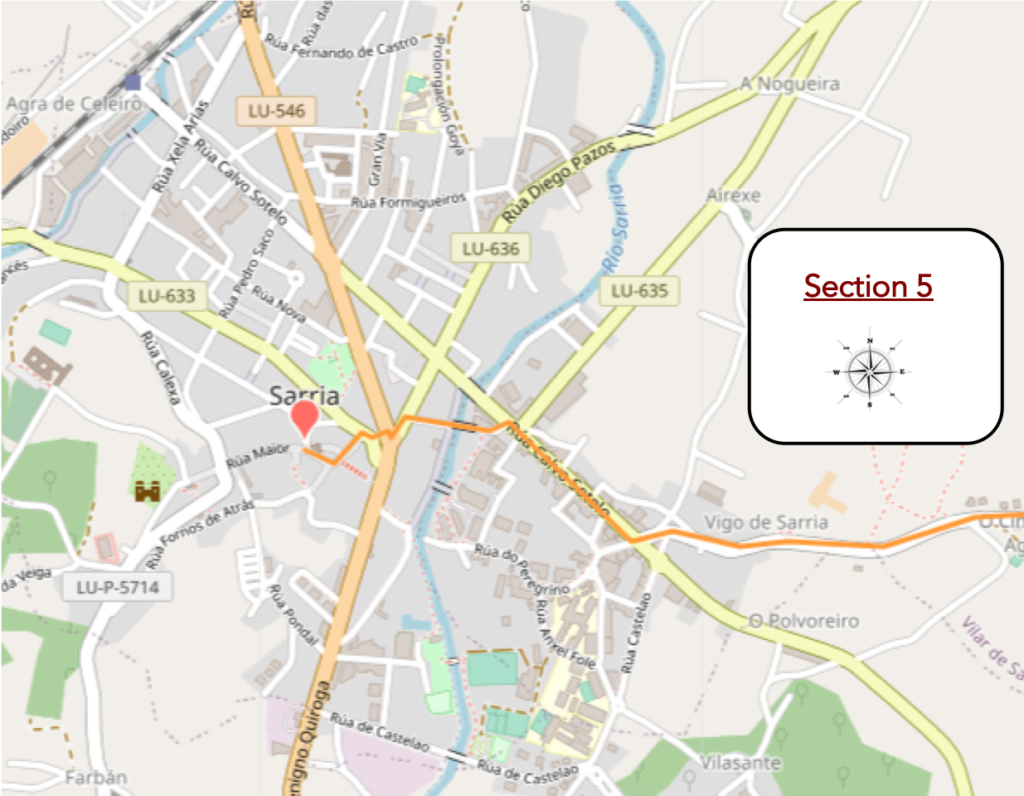

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-triacastela-a-sarria-par-le-camino-frances-via-san-xil-115141681

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

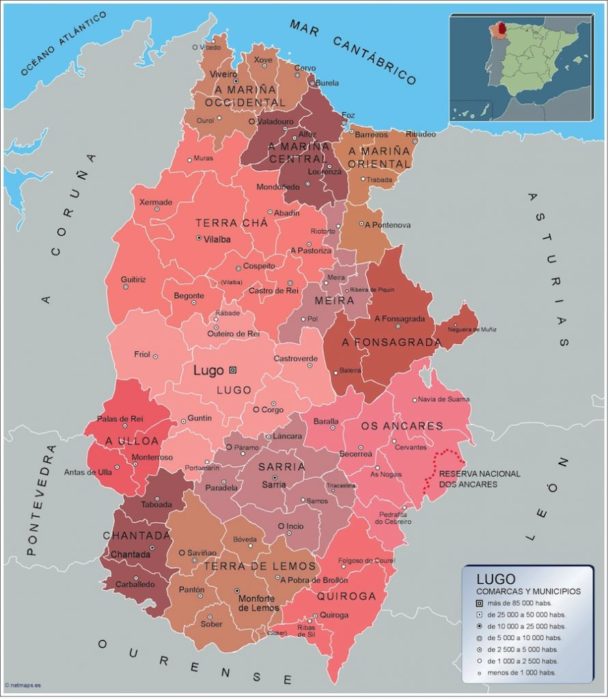

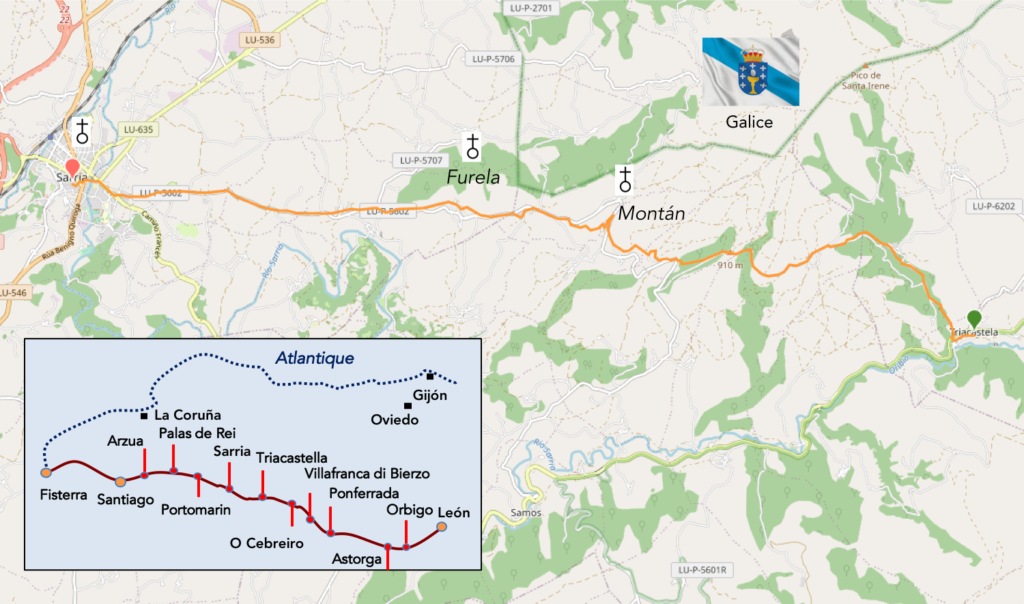

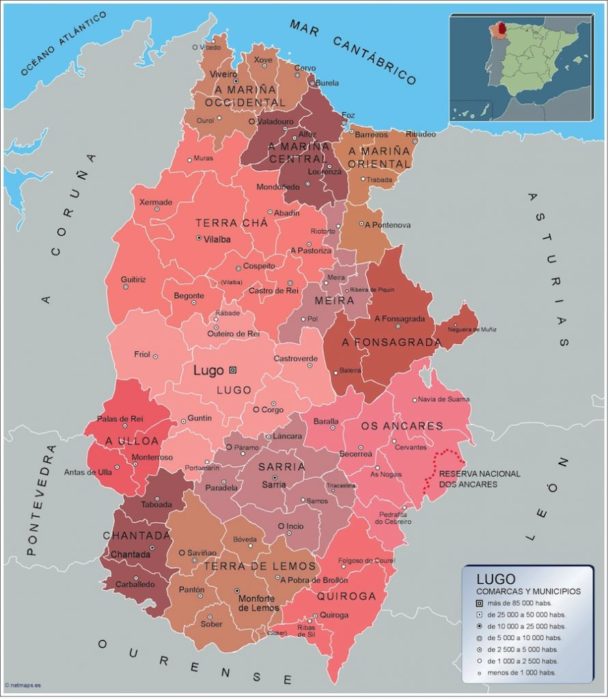

Today the route crosses the province of Lugo. The province of Lugo, in the northeastern part of the autonomous community of Galicia, is the largest province in Galicia. It is crossed by the western foothills of the Cantabrian mountain range and the Galician massif, interspersed with valleys dotted with hamlets. The main source of income is agriculture, with the province producing a lot of rye and potatoes. But cattle and pig farming are economically more important. It is also one of the main timber producing regions in Spain. The province takes its name from its main city, Lugo (98,000 inhabitants). The course does not pass there. Lugo was the most important Roman city in the Gallaecia during Roman times. Under the Swabians, the Visigoths, the Muslims, and until the IXth century, Lugo was the most important city in Galicia. However, its hegemony fell in 813, when the tomb of Saint James was discovered. As the city of Santiago grew around this tomb, Lugo’s prosperity declined. In the Middle Ages, Lugo, like Santiago de Compostela, was a center of pilgrimage. In modern times, Lugo had certain supremacy in the region, although other neighboring towns contested it. It was not until the division of Spain into provinces in 1833 and the creation of provincial governments that Lugo became the most important city in the province of Lugo, due to its status as capital. It is quite paradoxical but Santiago is not the capital of a province. It is part of the province of La Coruña.

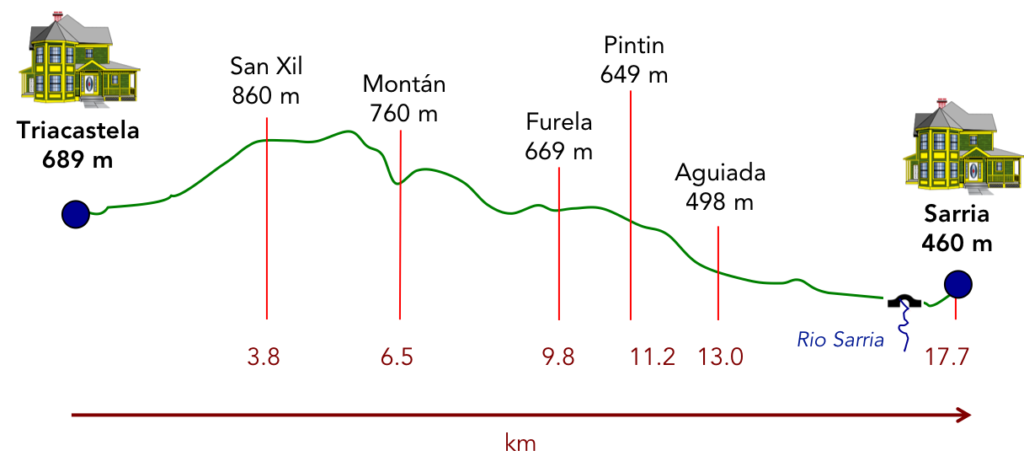

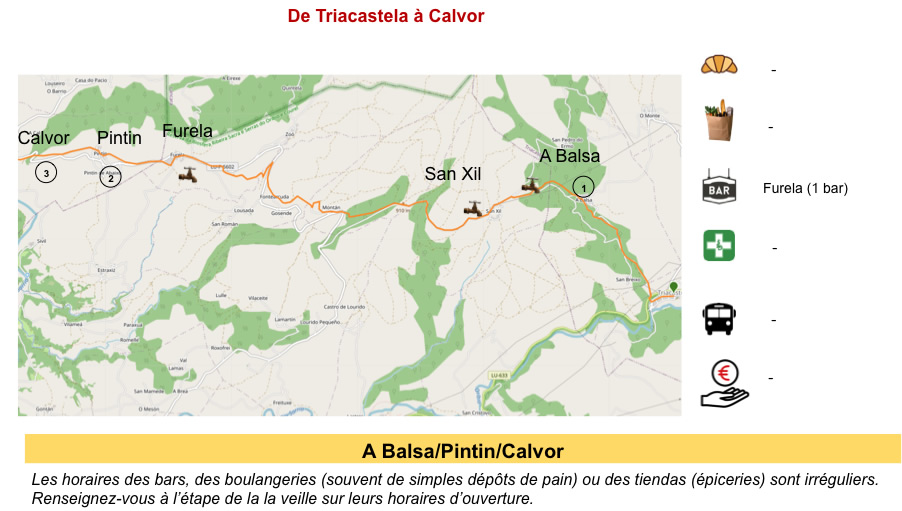

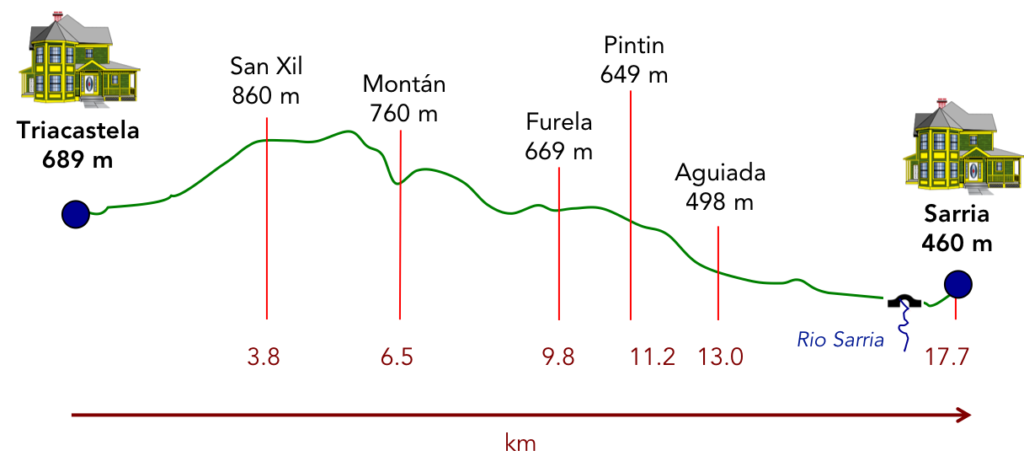

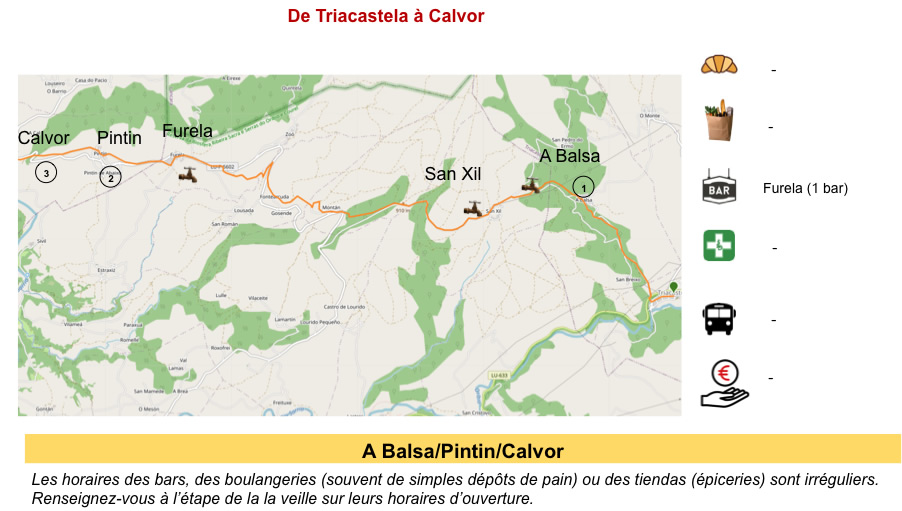

From Triacastela to Sarria there are two possible routes. One option is to follow the valley of the Río Oribio, which winds southwest to the village of Samos, where many pilgrims visit the Benedictine monastery, founded in the VIth century, and then head north to rejoin the more traditional route. This route is 25 km to Sarria. We will also describe it in this site. The traditional, more direct route is only 18 km from Sarria via San Xil. Purists claim this is the original route. It follows tracks through the lush Galician forests, sometimes like tunnels through chestnut, oak and birch trees, passing through some quite picturesque villages.

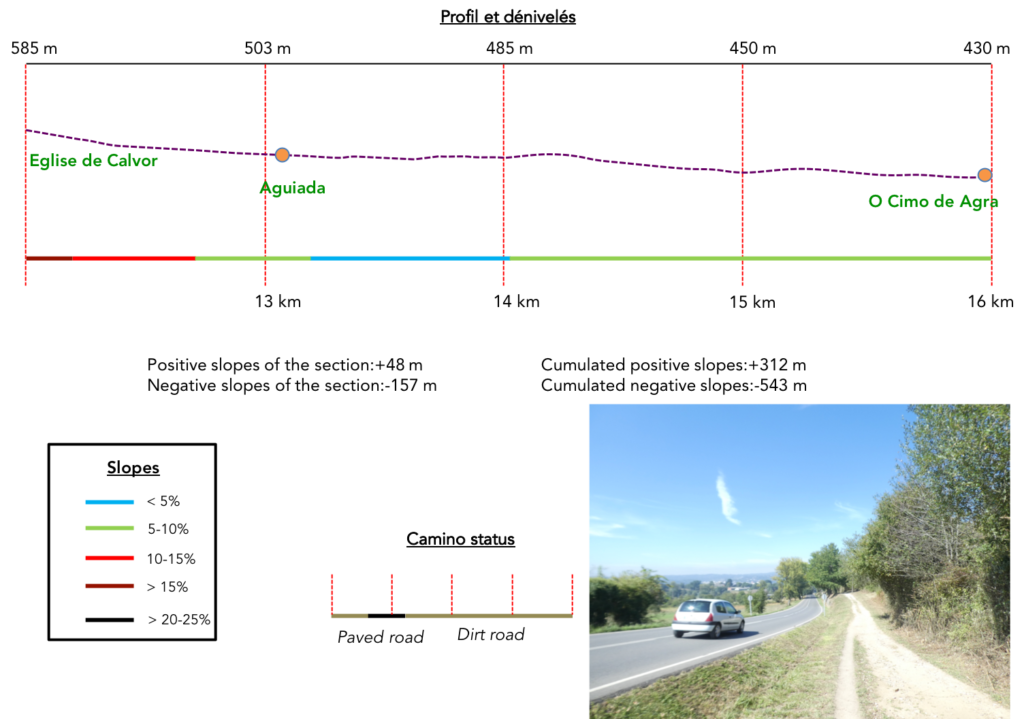

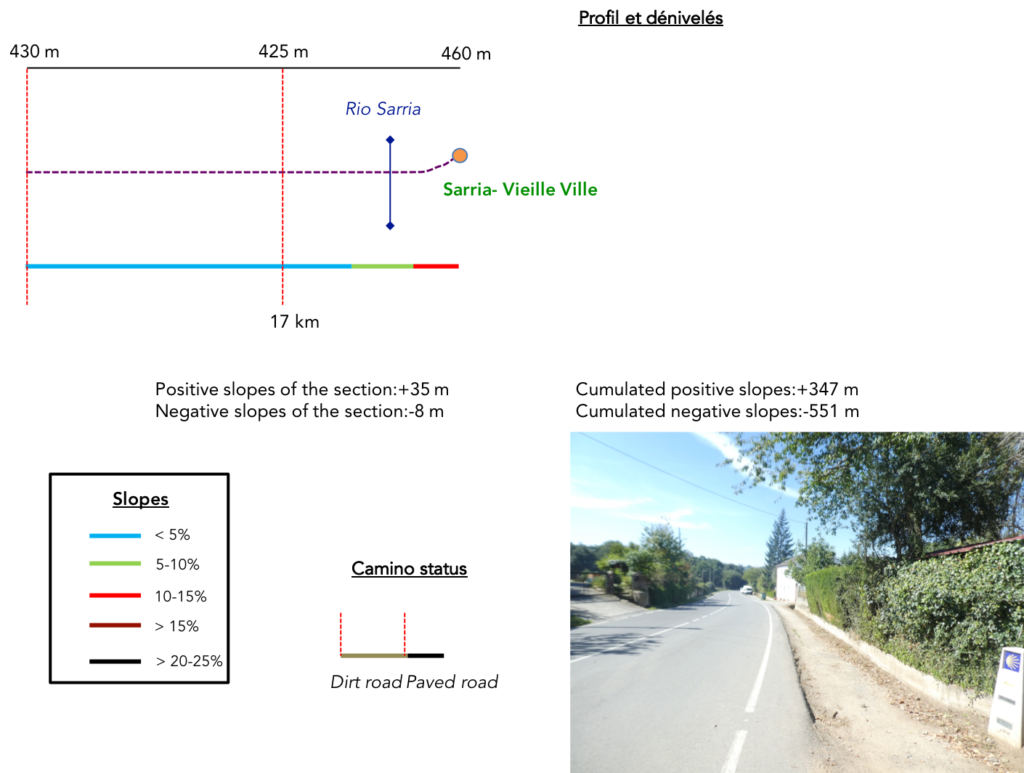

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+347m/-551m) are not negligible. This stage, although it is one of the shortest (18 km), has a certain degree of difficulty due to the long climb that takes place in the first section, until reaching the top of Riocabo. Thereafter, it is incessant ups and downs, just before undertaking the long descent to Sarria.

In this stage, you will walk almost as much on roads as on pathways. But these are roads with little traffic:

- Paved roads: 8.0 km

- Dirt roads: 9.7 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: In the forests of San Xil.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: 200 meters of elevation gain, with slopes not exceeding 15%.

| Beyond the center of Triacastela, the route passes a cruceiro and heads to the end of the long street that crosses the village. |

|

|

| There, a wooden St Jacques protects the village. |

|

|

This is where the choice is made: the traditional route or the Samos variant.

| The traditional route goes to the right, crosses the pass road and runs towards San Xil. |

|

|

| Quickly, through the meadows, the small road approaches the forest. |

|

|

Here, you will undoubtedly come across cows of the Rubia galega breed, also known as “red or blond from Galicia”. It is a meat breed, of large size, which wears a plain wheaten coat, with shades that can go from light blond to red. The legs are lighter, the mucous membranes pink, and they sport light horns with black tips.

| The road slopes up gently in the forest, under the shade of large trees, especially chestnut trees, oaks and maples. |

|

|

| Further up, at the level of a forest road, the route continues straight. |

|

|

| Beneath the venerable chestnut trees, it momentarily leaves the woods to cross the Rego da Balsa, a stream without much water. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the road briefly follows a steeply sloping paved section. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the course leaves the road… |

|

|

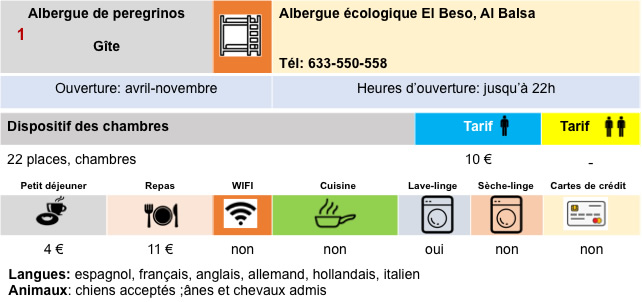

| …for a pathway that quickly reaches the place called El Beso. Here, the pilgrims get rid of their superfluous clothes, because they have undoubtedly learned in Triacastela that the climb becomes more difficult. In the middle of these rare stone houses, where beauty shines everywhere, there is a renovated old house, a community ecological lodge where you practice yoga, meditation, even bathing under the chestnut trees. |

|

|

| Just above the lost hamlet, nestles at the edge of the road a small marvel of a house in rough stones. A watercolourist once lived and worked here. Apparently, his shop has disappeared. |

|

|

| From here, dirt has replaced tar. Shortly after, the pathway runs to the outskirts of the village of A Balsa. |

|

|

| This is where the slope steepens, but will not exceed 15% until the top of the hill. |

|

|

| It is still here a corredoira, one of those magnificent sunken pathways that you can never get tired of, along stonewalls covered with moss, in the shade of tall trees. |

|

|

| The path sinks into the valley of the Rio Valdeoscuro, which means “dark valley”, which is justified. Here, the centuries-old chestnut trees compete with the great oaks and beeches. We are at the beginning of autumn. The ground is sometimes riddled with large pebbles which hinder walking, or else with a carpet of chestnut leaves, and you cannot tell if they are from the current year or from last year. |

|

|

Here, a majestic chestnut tree guards the meadows and woods like a sentinel.

| Just above, the hollow pathway joins at the top of the hard climb a small paved road, at a place called Fonte dos Lameiros. |

|

|

There was here on the edge of the fountain, a couple seated having a picnic. We did not want to disturb them to take the photo. But, as the fountain is magical, with its Compostela shell, we apologize for borrowing this one from Wikiloc; author : CHUCH100

| Beyond the fountain, the road climbs gently through meadows and trees to end up at the entrance to San Xil. |

|

|

| Here, there are some beautiful cut stone houses along the road, but the route does not go into the village, which is located below. |

|

|

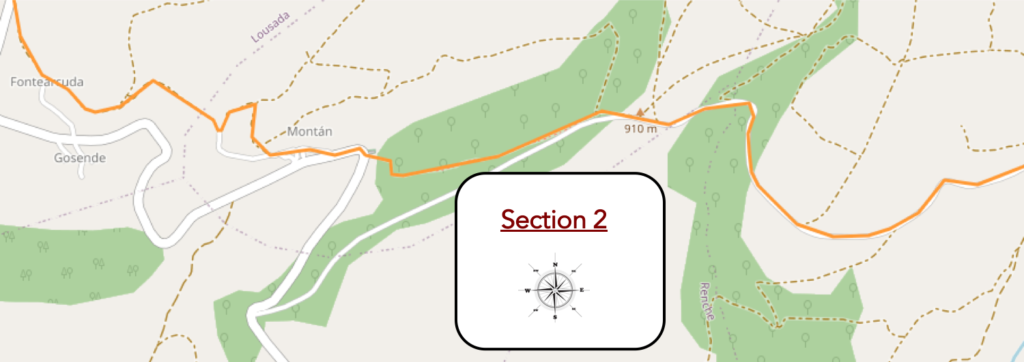

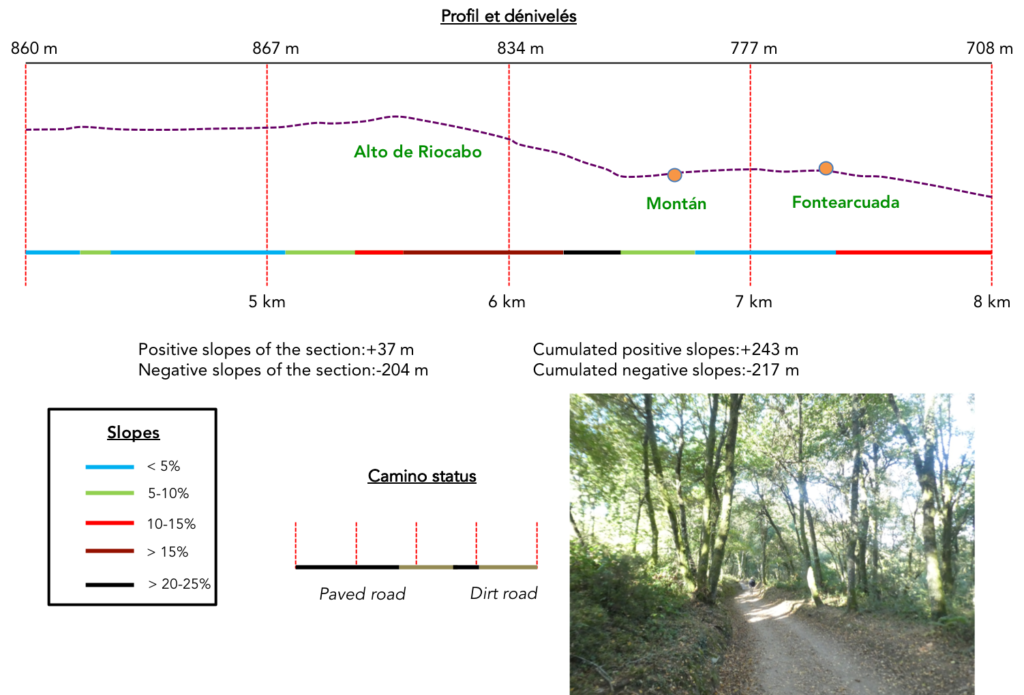

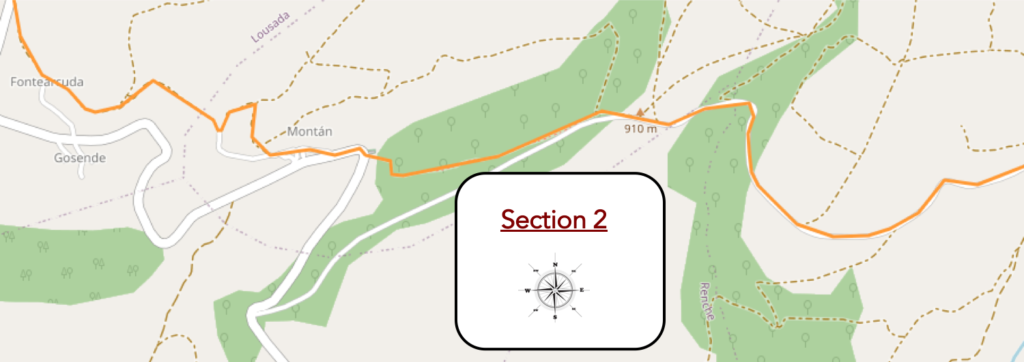

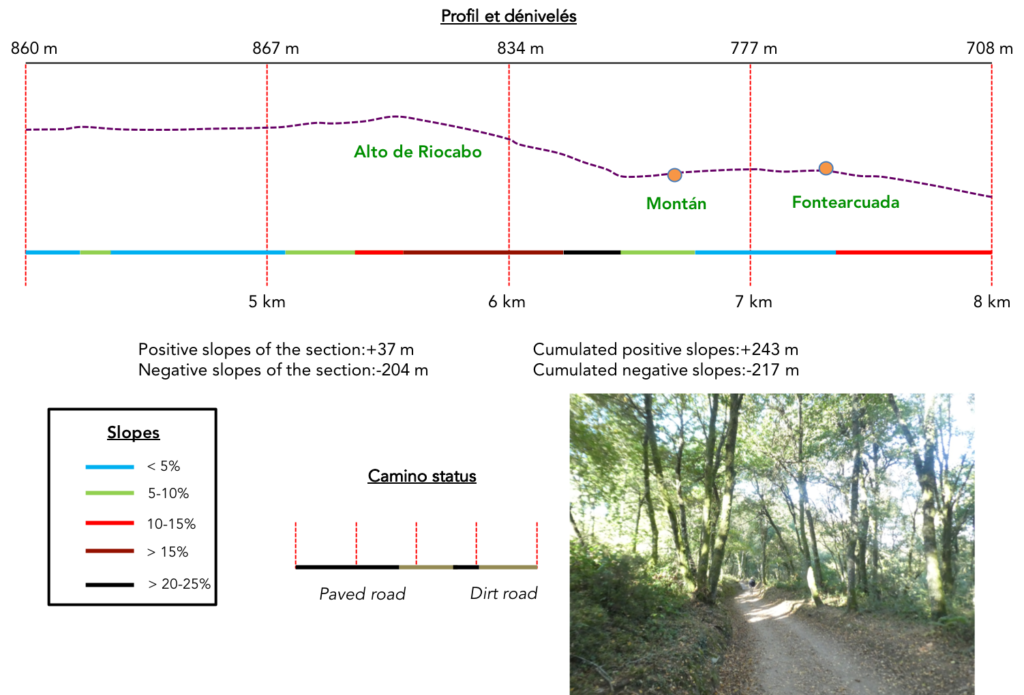

Section 2: A slight climb to a “false pass” before a steep descent.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: the descent is sometimes more than 20% steep.

| The road then flattens for a long time in the hardwoods. Here the chestnut trees have clearly disappeared and the dominant trees are poplars, birches and oaks. We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again. In Spain, oak species are much more numerous than in France, for example. Therefore, if you have an unacclimated eye, you will sometimes have difficulty recognizing them |

|

|

When the gaze is lost below, it is only dense woods without human presence.

| Further on, the road begins to slope up gently. Here, a pilgrim thought the right place to take a break was by the side of the road. It is also that the vehicles hardly circulate, if not at all. |

|

|

| We will tell you here that you are climbing a pass. You’ll find it hard to believe, right? Spruces are hardly present in these regions. They are only oaks, beeches, birches and poplars straight as stakes. |

|

|

Nearly, the road begins a kind of hairpin, as in the real passes. But it’s just to have a little fun with the hill.

| So, a last effort and you will arrive at the pass; at L’Alto do Rocabo, which is the official name of the pass (905 m), which is part of the Cordillera Cantábrica. This is the highlight of today’s stage. There is no refreshment bar here, nothing to show you the pass, just a toboggan waiting for you on the way down. |

|

|

| Here, the pathway plunges into the hardwoods. Here, the chestnut trees have taken over, dominating the oaks, maples and birches. |

|

|

| The forest is thick, delightfully, and the narrow pathway is not too rocky. It’s almost a mile of pleasure or pain. It depends. |

|

|

| The chubby chestnut trees make you real guards of honor. |

|

|

| It is at the bottom of the descent that the slope is the steepest. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the Camino joins the LU-P-5602, the departmental road which turns constantly on the hill, where stands the beautiful Romanesque church of Santa María de Montán, carved in rough stone. |

|

|

| Quickly, the Camino leaves the road to enter the compact dirt in the hamlet of Montán. |

|

|

| It is a peasant village, poor, without tourist infrastructure, except for a refrigerated cabinet that serves drinks. |

|

|

| But Montán actually consists of two parts. The pathway leaves the first part of the village to run towards the large stone farmhouses of the other half. |

|

|

| Here, an owner has established a stopover in a magical setting where it is good to eat. This type of place is the kind of haven favored by pilgrims. |

|

|

| The pathway leaves the village in oaks and bushes. Above winds the departmental road. |

|

|

| Vegetation is rich and abundant here, and oaks of all varieties cast generous shade over the lightly gravel pathway. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway crosses the few houses and farmhouses of Fontearcuda. The hamlet originates from an inexhaustible source of water. But, the source is apparently not in the way. At least we didn’t drink its water. |

|

|

If you take a look below at the Sarria Valley, you will very often see large patches of fog there. In autumn at least, the valley has this reputation.

| Beyond the hamlet, the pathway descends steeply into the oak undergrowth… |

|

|

| …until you join the departmental road below. |

|

|

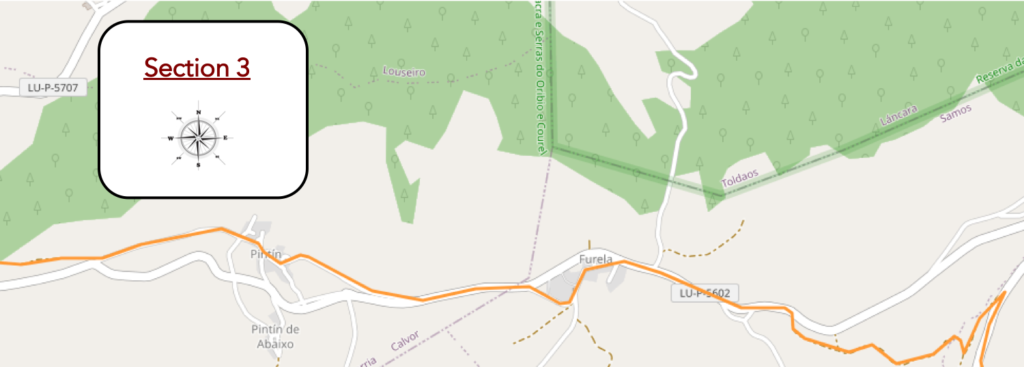

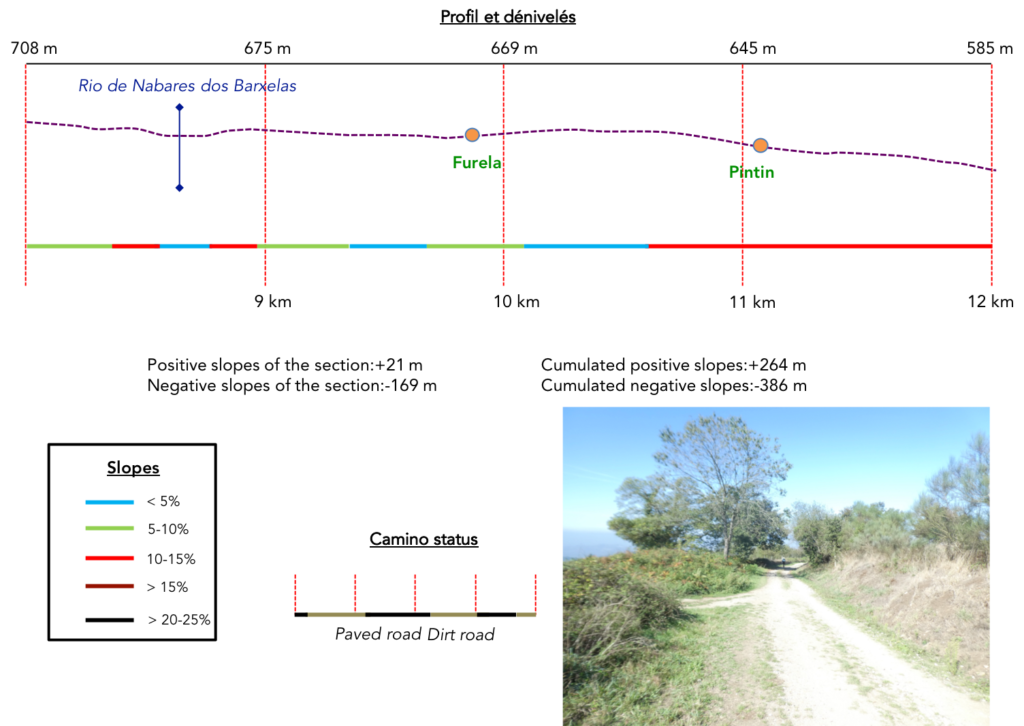

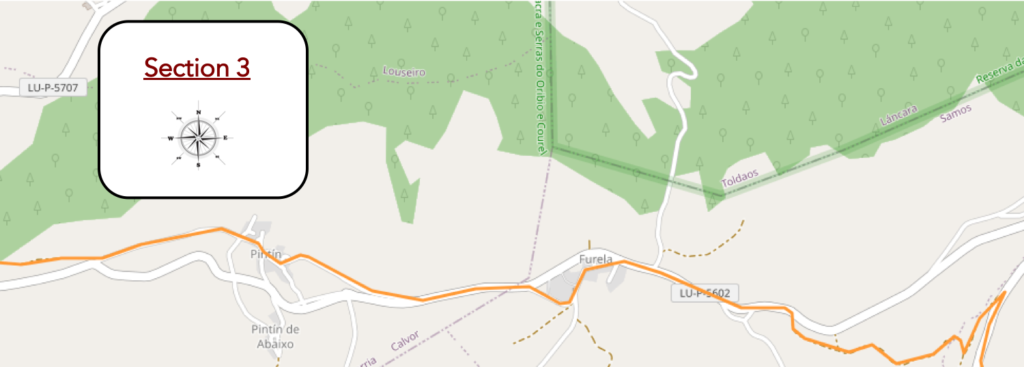

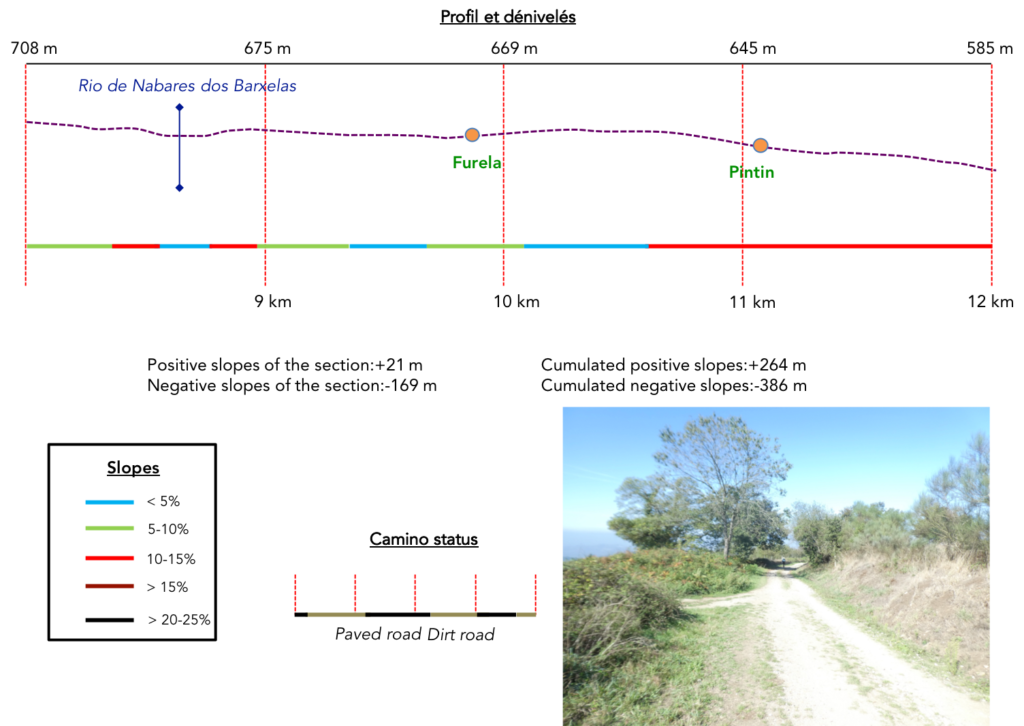

Section 3: Over hill and dale in the countryside.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: descent above all with reasonable slopes.

| The Camino then follows the departmental road for 200 meters, which will make a large loop here to return to Furela. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it leaves the road to descend steeply along the Rio de Nabares dos Barxelas. |

|

|

| The descent is short, in the sumptuous oaks and dilapidated chestnut trees. At the bottom, the pathway crosses the stream. The setting is lovely. |

|

|

Here, an alchemist does some publicity for his house of art away from the track.

| Beyond the stream, the pathway slopes up gently in the meadows… |

|

|

| …then, more steeply, in a sunken pathway under the big oaks. |

|

|

| From the top of the short hill, the pathway descends gently into the meadows until it rejoins the secondary road, which has completed its loop. |

|

|

| It is possible to walk along the side of the road to reach Furela, but here it is not the traffic that bothers. These are fairly empty regions of people, and the villages often have less than fifty inhabitants. |

|

|

In Galicia, you will often see cabbages grown on very tall stems.

| Further on, the Camino leaves the departmental road to enter the village on slabs. |

|

|

| It is a peasant village, without much infrastructure for pilgrims, except for a small bar with drinks and sandwiches. The village borders the municipalities of Samos and Sarria. |

|

|

| Here, there are also dairy cows, these brave Holsteins, with hanging teats. A small chapel is discreet at the edge of the road. |

|

|

| People probably didn’t know what to do with the stones. So, they made flat stone hedges. Behind them, there is probably nothing valuable to hide. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, beyond a superb oak tree, the Camino finds the departmental road back. Pilgrims no longer raise an eyebrow at the sight of a new “senda de los peregrinos”. It is now as if they were born in northern Spain. |

|

|

| But here, it is no longer the Meseta, and the passage is short, in the meadows. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway diverges from the road. |

|

|

| Then, it gradually descends steeply on the embankments towards the village of Pintin. Here, it smacks of the good and real countryside, that of the heaps of manure, and the beautiful Rubia Galega. |

|

|

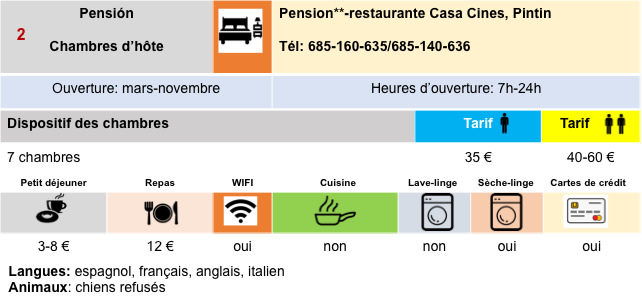

| Pintin is also a poor, sloping village with an inn and a restaurant. |

|

|

| At the exit of the paved village, the Camino finds a small paved country road. |

|

|

| It follows the road for a few hectometers… |

|

|

| …before finding a dirt road. |

|

|

| Here, it is still one of those beautiful sunken paths bordered by stonewalls from another age, which descends steeply into the oaks that grow in abundance. |

|

|

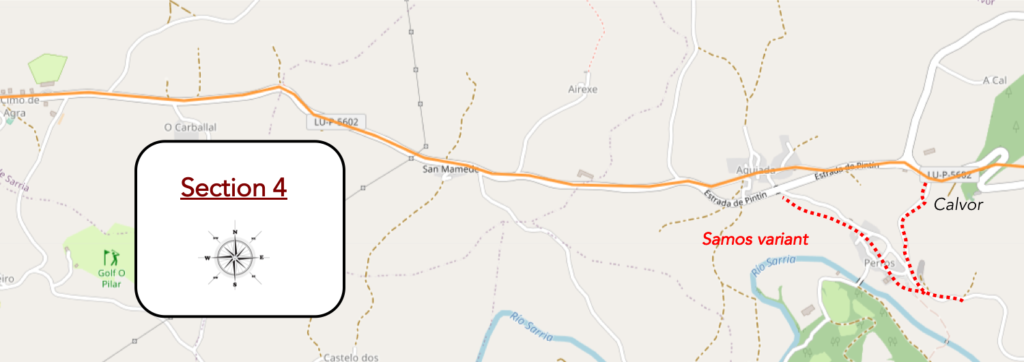

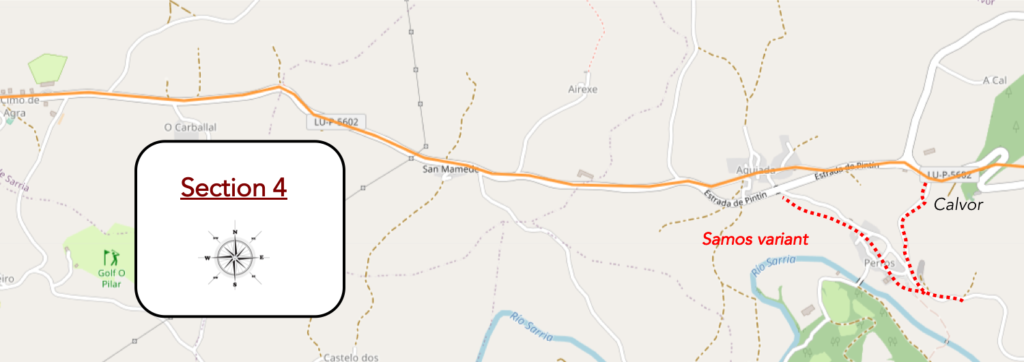

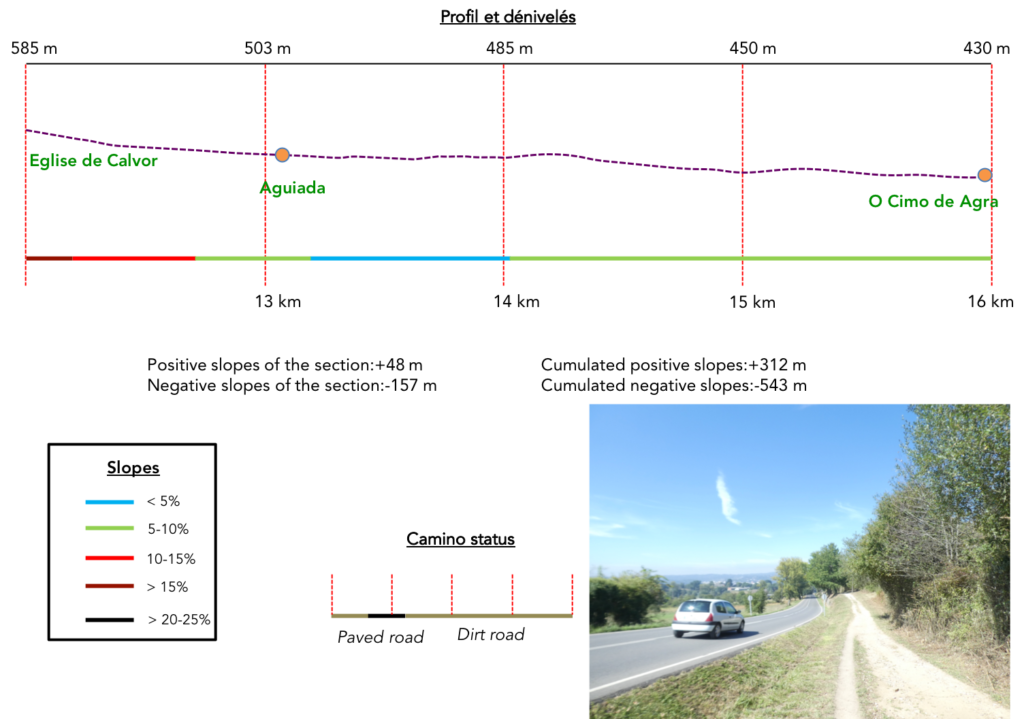

Section 4: Again on the “senda de los peregrinos”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: steep descent at the start, then course without difficulty.

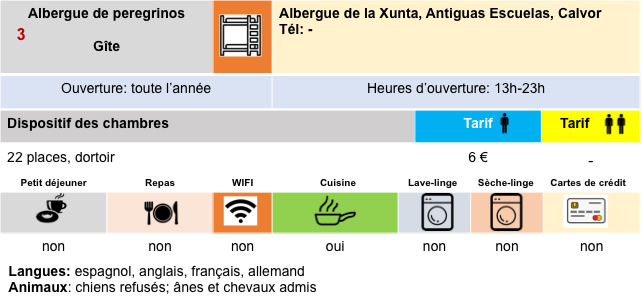

| The pathway comes near Calvor Church but does not go there. Calvor occupies the site of a pre-Roman fort, Castro Astorica. In the VII century, a monastery was founded here. The Church of San Esteban dates back to Visigothic times, but what remains today is mainly from the XVIIIth-XIX9th century.

Here, the Camino does not follow the road, but descends very steeply into the undergrowth. |

|

|

| Here, the oaks are very majestic. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway joins the departmental road back… |

|

|

| … to then begin a long section along a new “senda de los peregrinos”. |

|

|

It’s not just the cows that watch the pilgrims pass by, in the shade of the oaks.

| Further down, the Camino leaves the “senda de los peregrinos” to visit the hamlet of Aguiada. |

|

|

| This is where the variant that goes through Samos returns. |

|

|

| There were once several hospitals for pilgrims. Nothing remains. There is a tiny, simple chapel with a bell by the roadside. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses a poor village, where you also find cabbage high on the stem. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino finds the “senda de los peregrinos” back. |

|

|

| Traffic is derisory on the axis. And the walk is gentle under the mighty oaks. |

|

|

| There are hamlets the size of pocket-handkerchiefs, far from the road, like San Mamede do Camiño here. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway approaches some undulations in a gentle countryside landscape. |

|

|

| At a bend in the road, you will see Sarria in front of you. But it’s not next-door. |

|

|

| A rare vehicle runs and the slope is gentle under the oaks and poplars. |

|

|

| Further on, the oaks and ash trees create real tunnels of shade… |

|

|

| …and even the pines join in. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway arrives at O Cimo de Agra, a suburb of Sarria. |

|

|

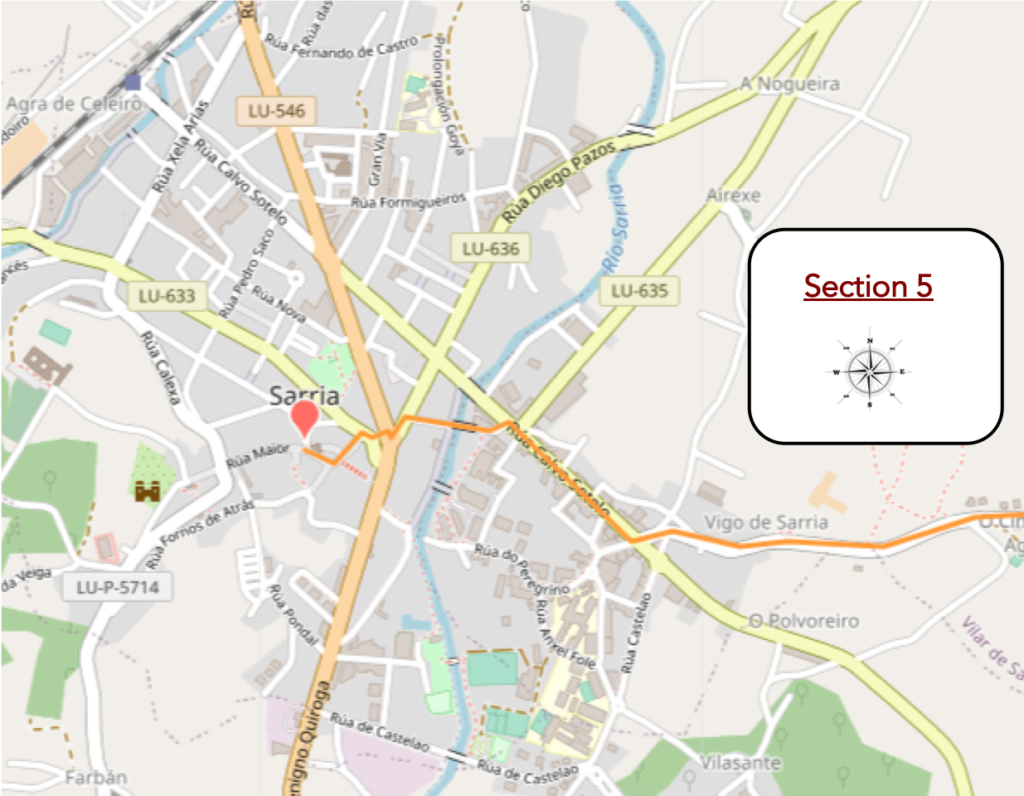

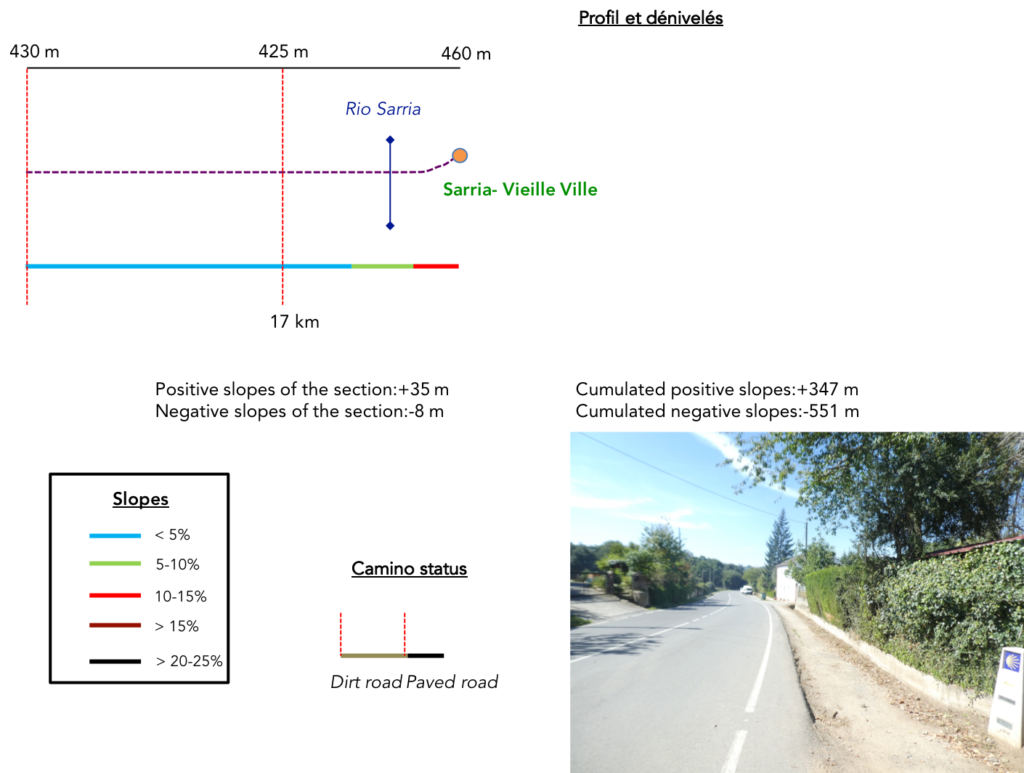

Section 5: In Sarria.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: without difficulty, but it climbs to reach the old town.

| The pathway crosses O Cima de Agra. |

|

|

| Further on, at the entrance to the town, there is a large park with a campsite. |

|

|

| The route then enters the city. Sarria (11,000 inhabitants) is the capital of the region of the same name. It is a place populated for thousands of years, inhabited by both Celts and Romans. The Roman presence in Sarria is linked to the neighboring Roman city of Lucus Augusti, the current Lugo. The Muslim conquest was limited and left virtually no trace. The main history of this municipality began here with the first pilgrimages to Santiago. At the end of the XIIth century, Alfonso IX, the king of Galicia and León, established the city here as a “royal city”. The king died there in 1230. Sarria then became a major medieval center for pilgrims, giving rise to hospitals, chapels, monasteries, bridges and inns. |

|

|

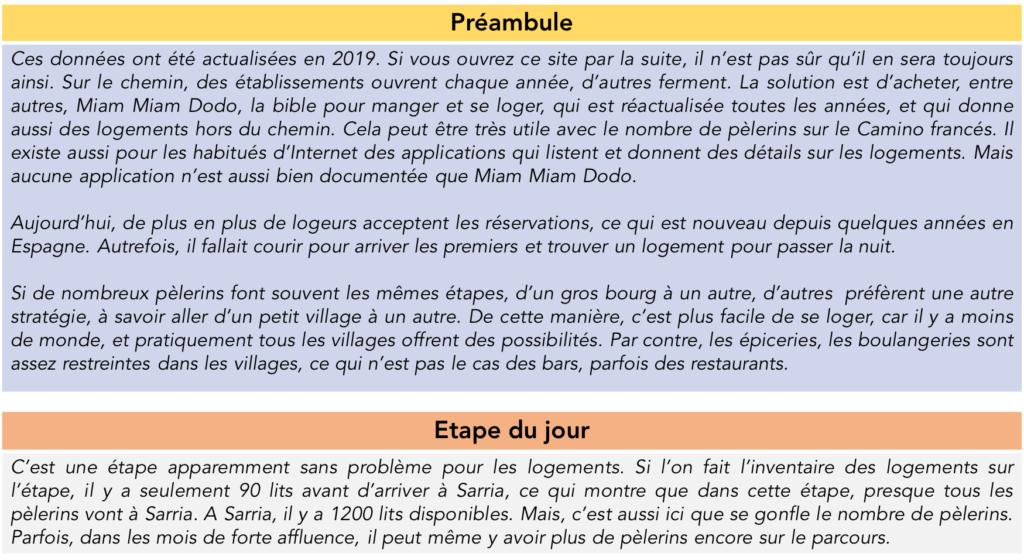

When you arrive at the end of the road (LU-P5602) by which you came, you will cross the main street, the LU-633 that goes towards the city center. The Camino does not go there, it continues straight at the crossroads, to follow Rua Peregrino and cross the Rio Sarria by the Ribeira bridge over the Rio Sarria. To help you, here is an animated map proposed by the Tourist Office.

| The XIIth century Ponte Ribeira on Rúa do Peregrino (Pilgrims Street) is one of four medieval bridges in the city which together were declared Bien de Interes Cultural in 2011. There were many works undertaken here. This left the bridge cut for months, until 2015. But everything was back to normal. But, there is an alternative, namely crossing a once pedestrian bridge (ponte pedonal) that leads to the charming restaurant district on the river. |

|

|

| The decline of pilgrimages to Santiago brought a long period of decline for the city. In the XVIIIth century, there were only 70 houses and a few stalls in the village. Sarria was then a rural municipality. In the XIXth-XXth centuries, the city developed, the city center gravitated towards the east. This part of the city, the big part in fact, does not offer much interest for pilgrims.

For the pilgrim, everything happens at the entrance to the city and especially in the old town located on the hill. It is accessed from the bridge by the Escalinata Mayor, formerly called Escaleira da Fonte (in Galician: Bridge Staircase), dating from the XIXth century. |

|

|

| The staircase leads to the Rúa Mayor, the main street of the old town, passing by the Church of Santa María, with its painting of pilgrims going to the church. The Church of Santa María (St. Mariña, a Galician martyr) was built on the ruins of the ancient Romanesque church from the XIIIth century, dedicated to San Xoán, patron saint of the city. The new church was inaugurated at the end of the XIXth century. It is located on Rúa Mayor, next to the old Plaza del Mercado, where Sunday markets were held until the end of the last century. Its pyramidal tower contains a clock. |

|

|

Beyond the church, the Rúa Mayor climbs towards the fortress. Here, during the day, and in the evening, at dinnertime, it is full of pilgrims. You have to take the pictures in the morning to find some peace.

| Depuis l’église, la Rúa Mayor monte vers la forteresse. Ici, en journée, et le soir, à l’heure du dîner, c’est noir de pèlerins. Il faut prendre les photos au matin pour trouver un peu de calme. |

|

|

| Further up, the restaurants are sometimes in fierce competition. There are so many new pilgrims arriving in Sarria to join the other pilgrims. |

|

|

Further up, on the Praza da Constitución (Constitution Square), there is a statue of Alfonso IX, king of León and Galicia, in the XIIth century, who made this city a royal city. He died here of a serious illness while making a pilgrimage to Santiago. He is buried in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

| At the top of the street stands the Church of San Salvador, mainly from the XIIIth century, in late Romanesque style. You have to climb to the top of the hill to see the ruins of the castle. The Fortaleza de Sarria dates from the XIIth century, built on the site of a former castro (hill fort). Of the original fortress, only one of the 4 towers remains. Called Torre de Sarria or Torre de la Fortaleza, it is crenellated, 15 m high, and built of stones and granite slabs. The rest was destroyed in the XVth century, during the uprising of the peasantry against the aristocracy known as the Irmandiños. The castle was rebuilt in the XVth century and inhabited, but at the end of the XVIIIth century, it was in ruins. So, the city council bought the castle and dismantled it using the stones to pave the streets of the city, and many of the stones and the other towers were sold to the townspeople. The remaining tower is private and cannot be visited. |

|

|

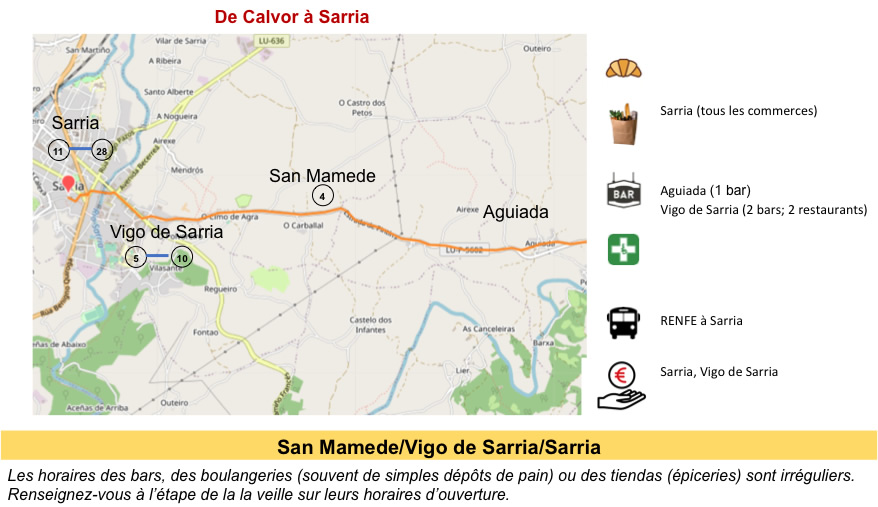

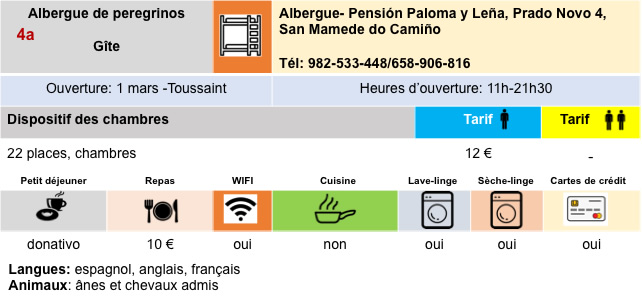

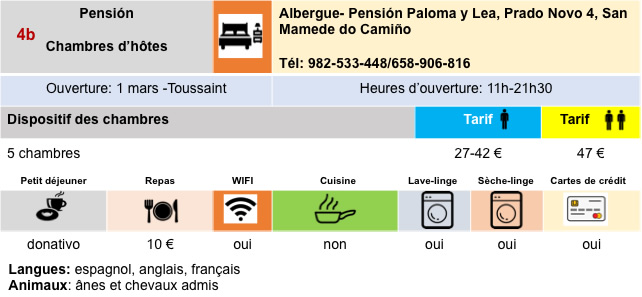

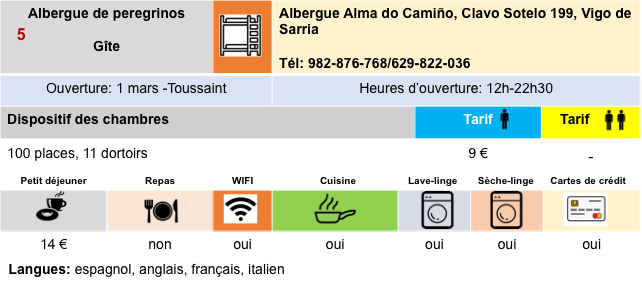

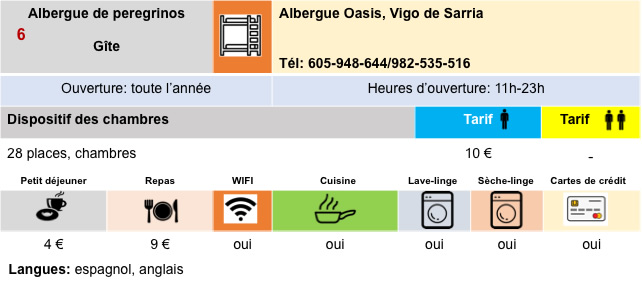

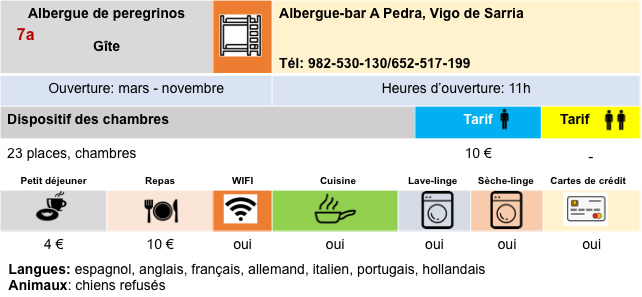

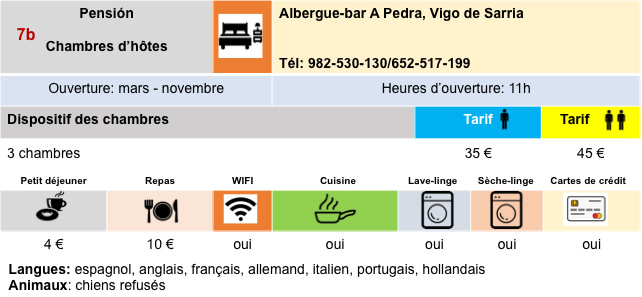

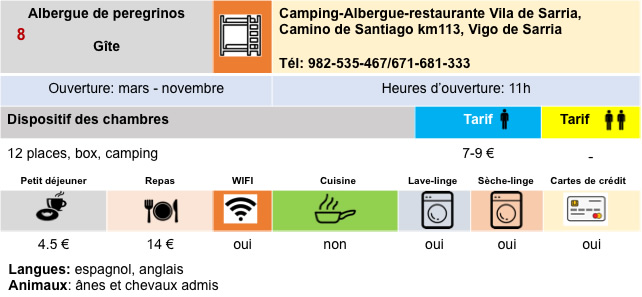

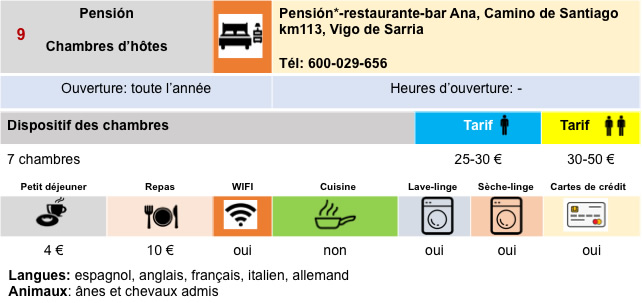

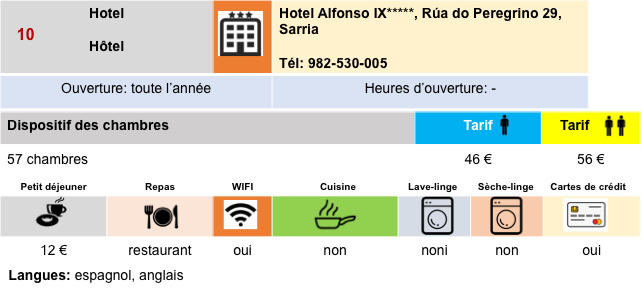

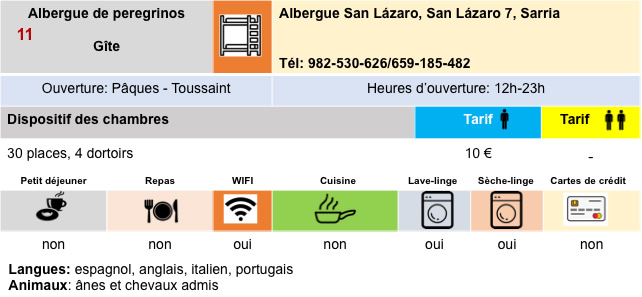

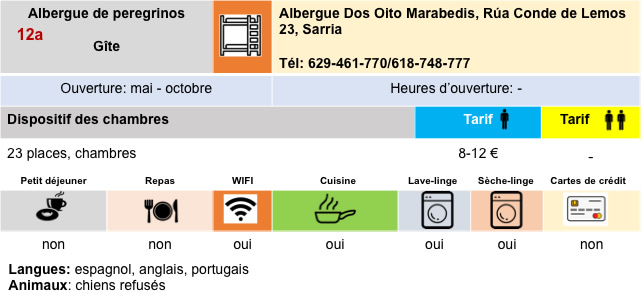

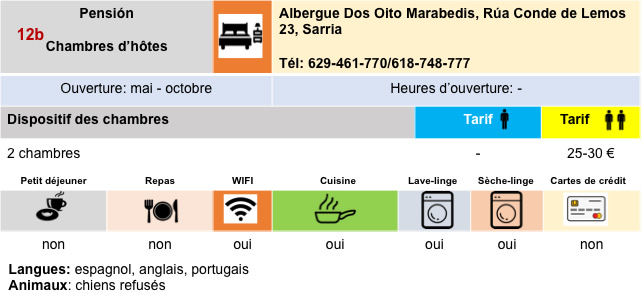

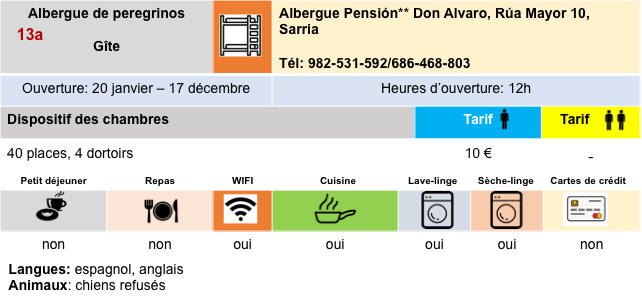

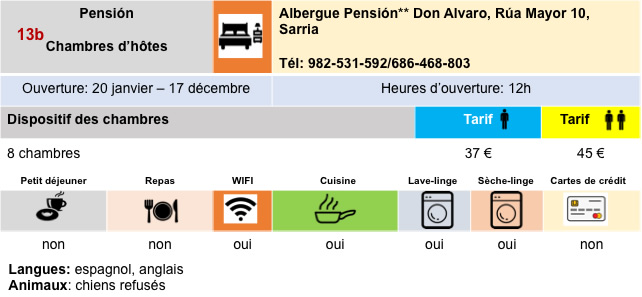

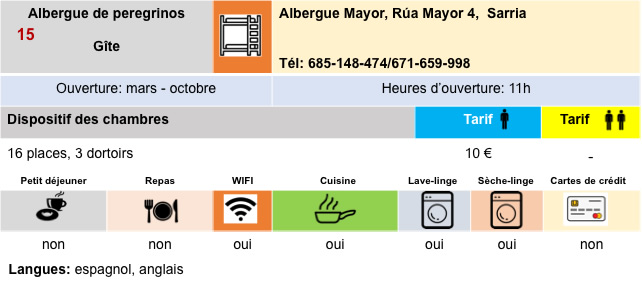

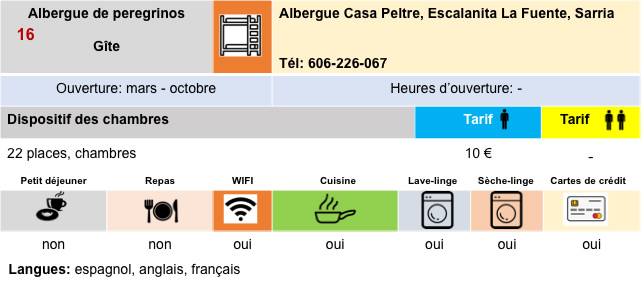

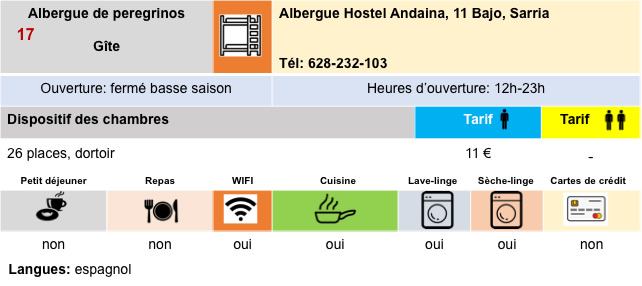

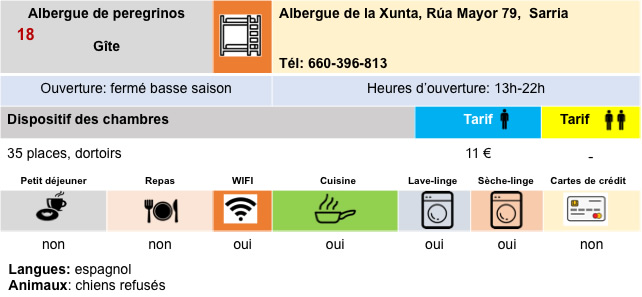

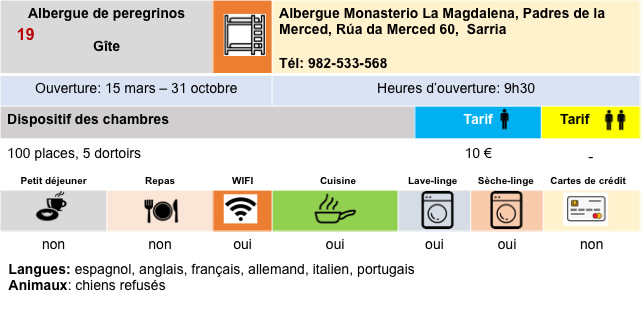

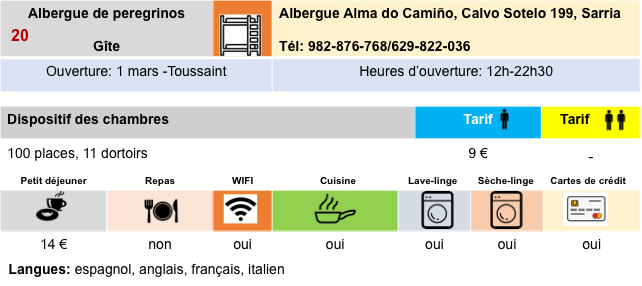

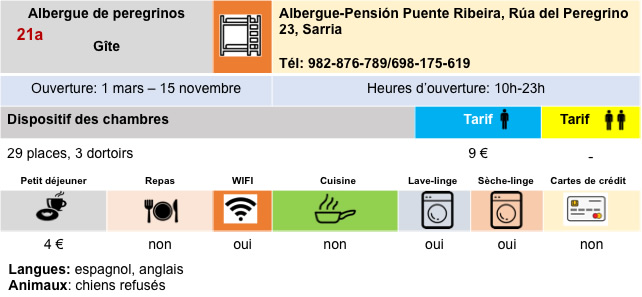

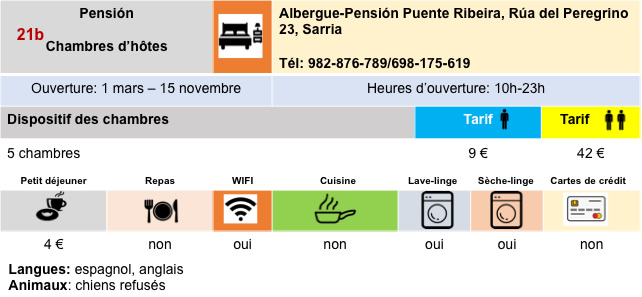

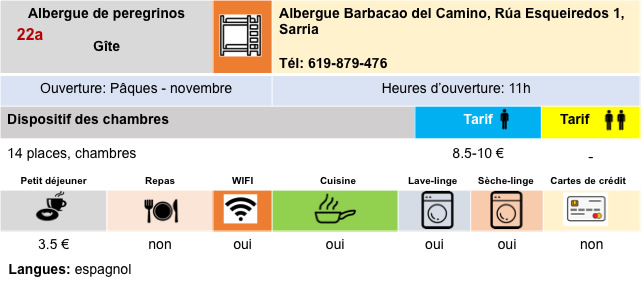

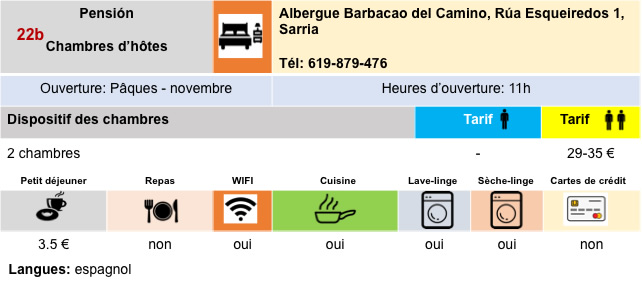

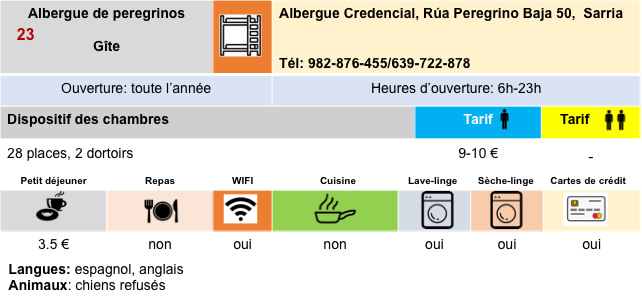

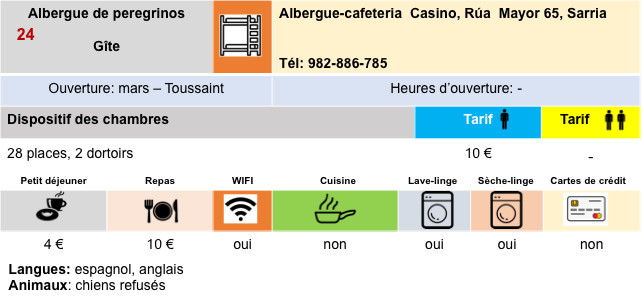

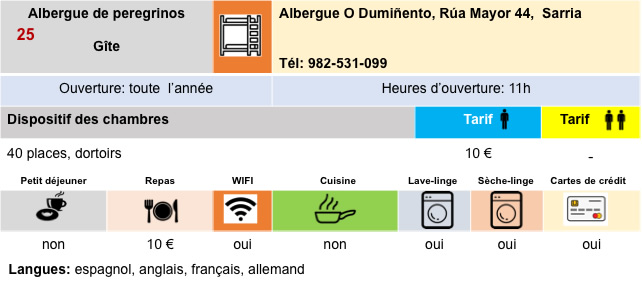

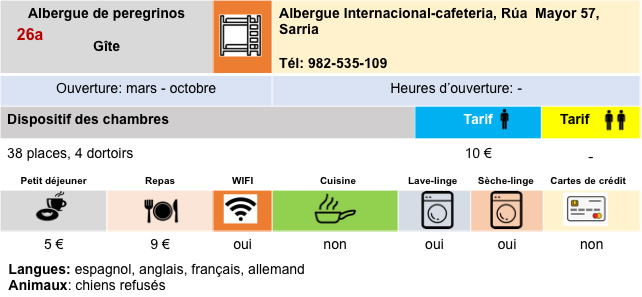

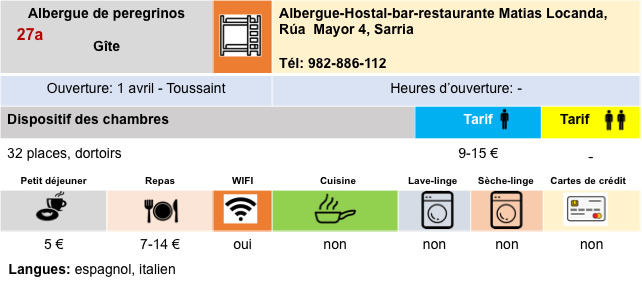

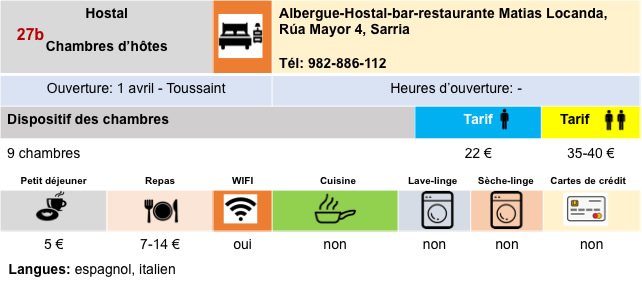

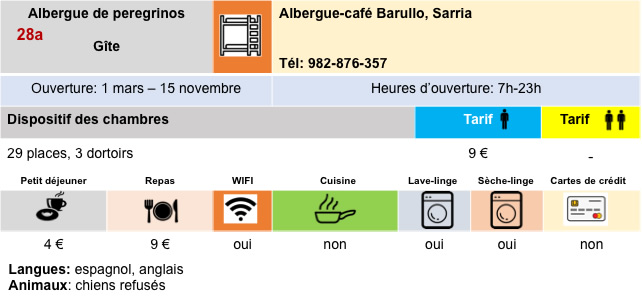

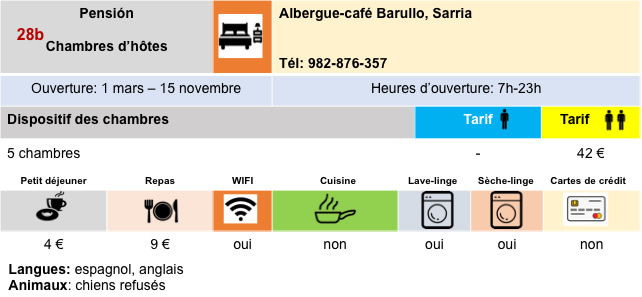

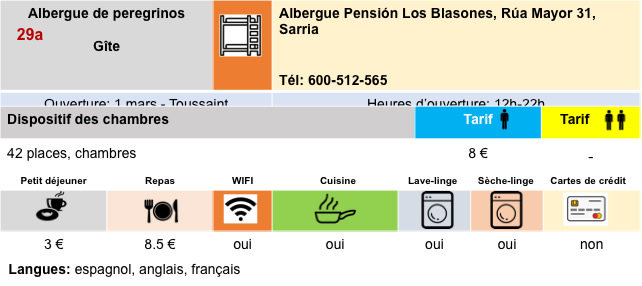

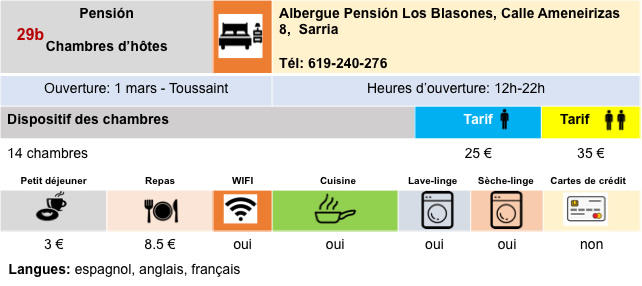

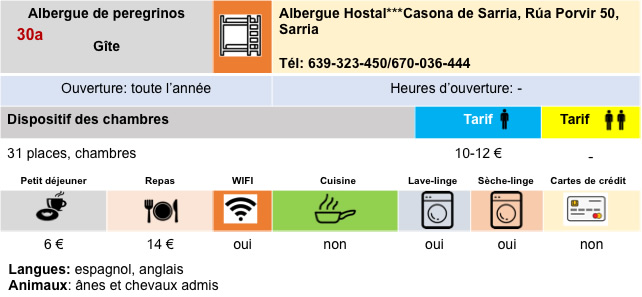

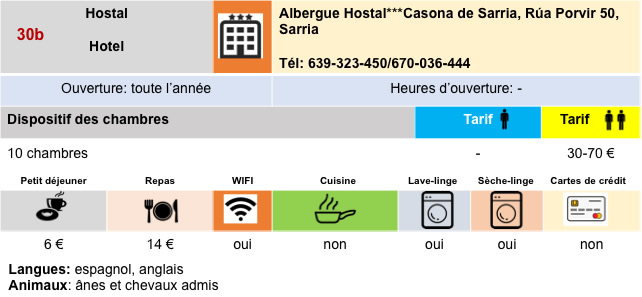

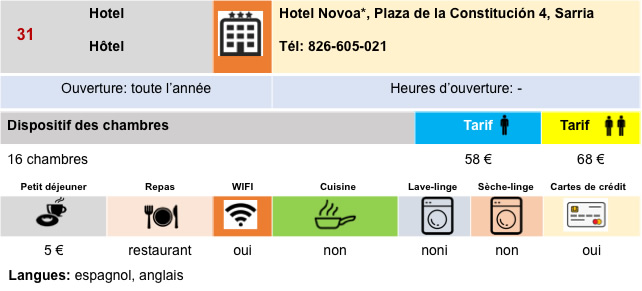

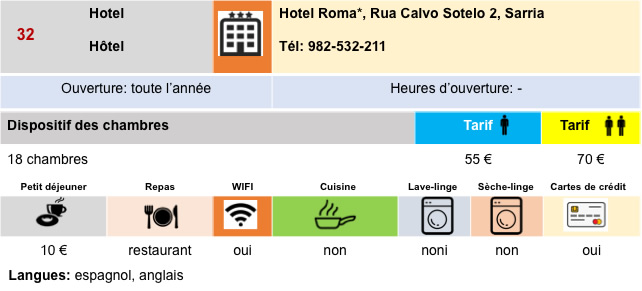

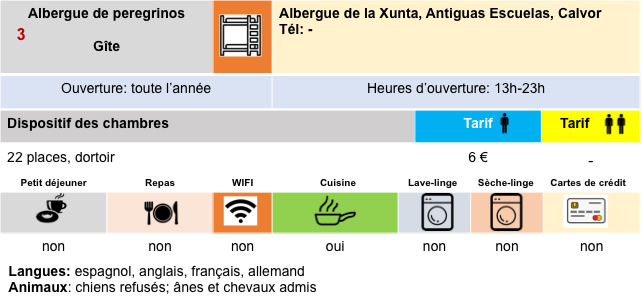

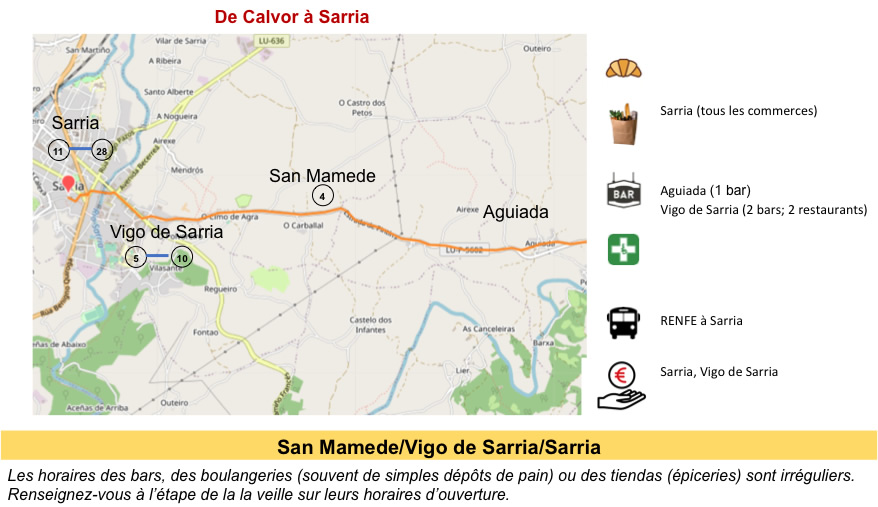

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 11: From Sarria to Portomarín |

|

|

Back to menu |