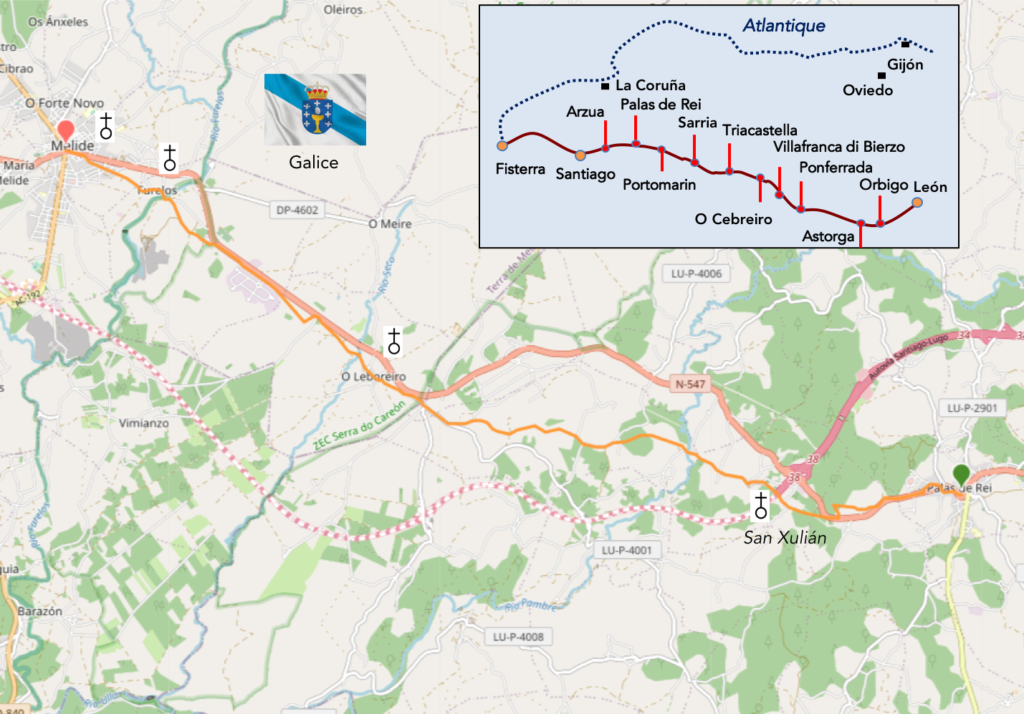

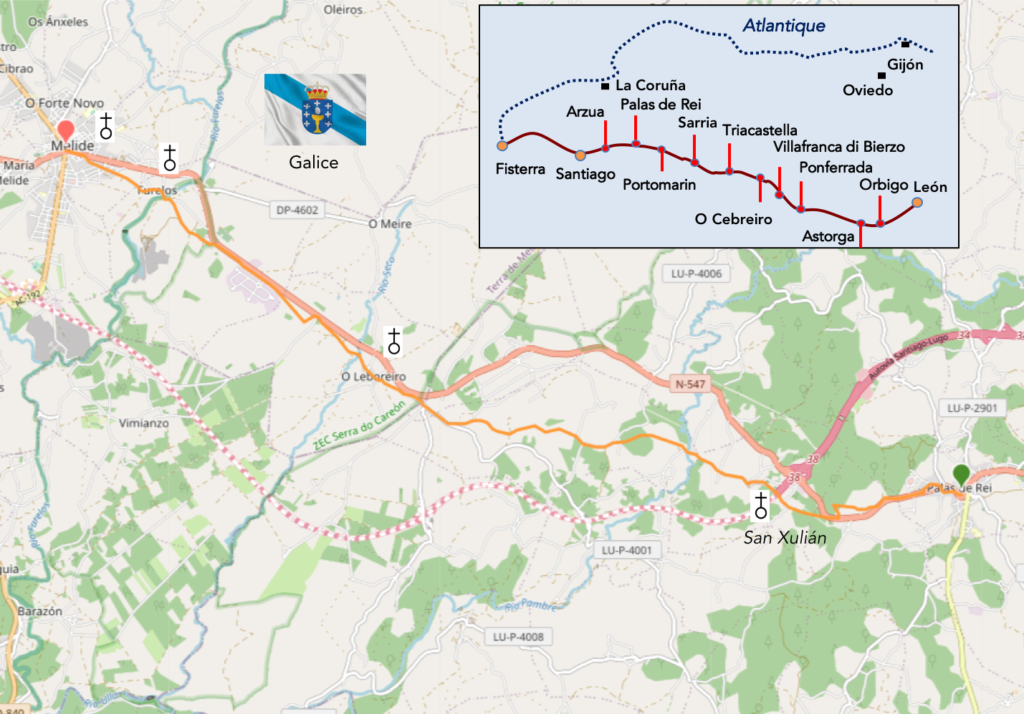

From the province of Lugo to the province of A Coruña

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-palas-de-rei-a-melide-par-le-camino-frances-125093673

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

The origins of Melide date back over 4,000 years, as evidenced by the megalithic dolmens and burial chambers found scattered around the area. The site was inhabited in Celtic times and, in Roman times, the city took its name from its owner, who was called Mellitus. It was once an important crossroads of the Roman Via Trajana and the northern routes descending from the Cantabrian coast. The village, documented from the VIIIth century, belonged to the bishoprics of Oviedo, then of Santiago. The city proper dates back to the Xth century, but it seems to have gained importance when King Alfonso IX gave the lands surrounding Melide to the Archbishop of Santiago in the XIIth century. In the XIVth century, a castle was built here and the city was walled to fortify it, but the walls were destroyed during the uprising of the Irmandiños against the nobility. The ruins of the castle and the walls were used to build the monastery and the hospital of Sancti Spiritus in the XIXth century, of which today only part of the Gothic church remains.

In the Middle Ages, the Camino route was Melide’s most prominent feature, and the city centered its businesses, hospitals and residences on a long street that locals simply called “la Calle” (the street). The people were primarily innkeepers and there were 4 major pilgrim hospitals. Today, the old part of Melide follows its medieval layout with narrow, winding streets with shops, bars and restaurants serving the regional specialty, pulpo (octopus). Restaurants here typically specialize in pulpo a la feria, where octopus is cooked in large copper cauldrons and served on wooden platters sprinkled with paprika and olive oil, to be enjoyed with bread and a drink of Galician white wine, Albariño or Ribeiro.

It is still a beautiful stage, sometimes a little more busy, most often in the middle of oaks, chestnut trees and eucalyptus, along magnificent sunken pathways. The fields west of Palas de Rei are called Campo dos Romeiros (Romans). The forests are interspersed with cornfields. There is also, alas, road and the villages are almost medieval. Today you’ll leave the province of Lugo for the province of La Coruña. It is in this province that Santiago de Compostela is located.

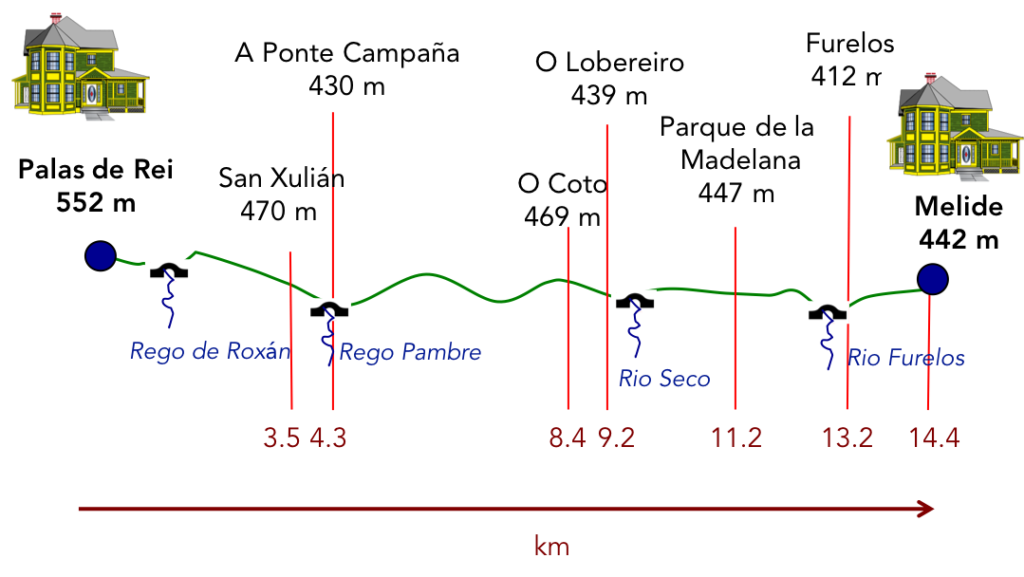

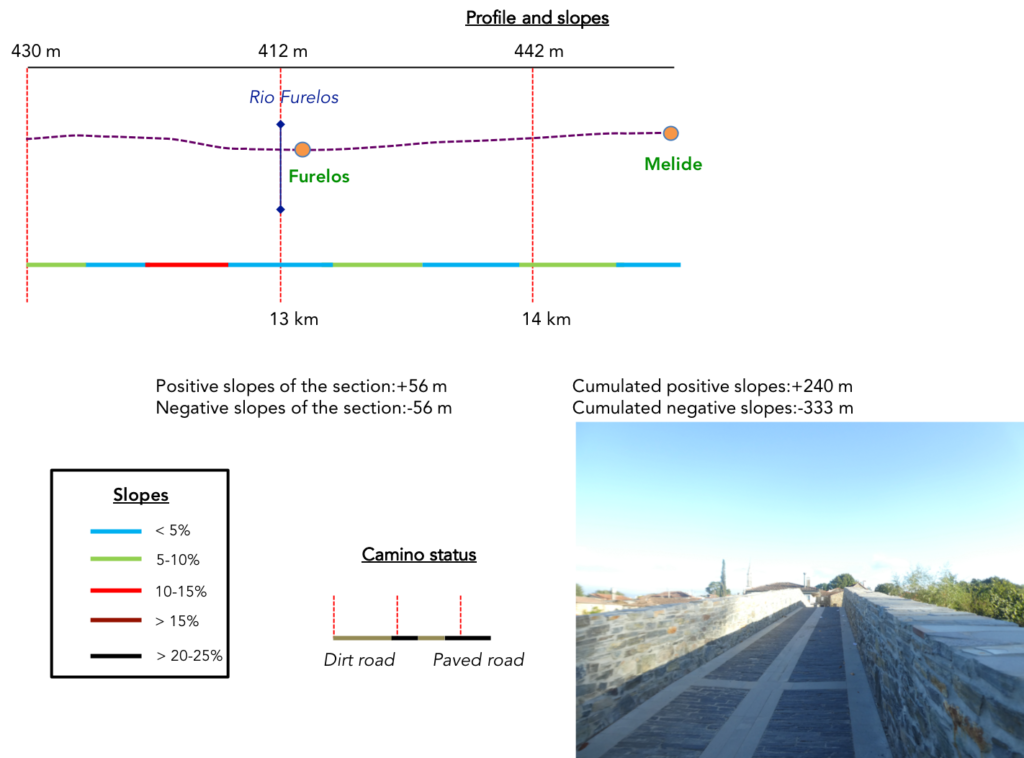

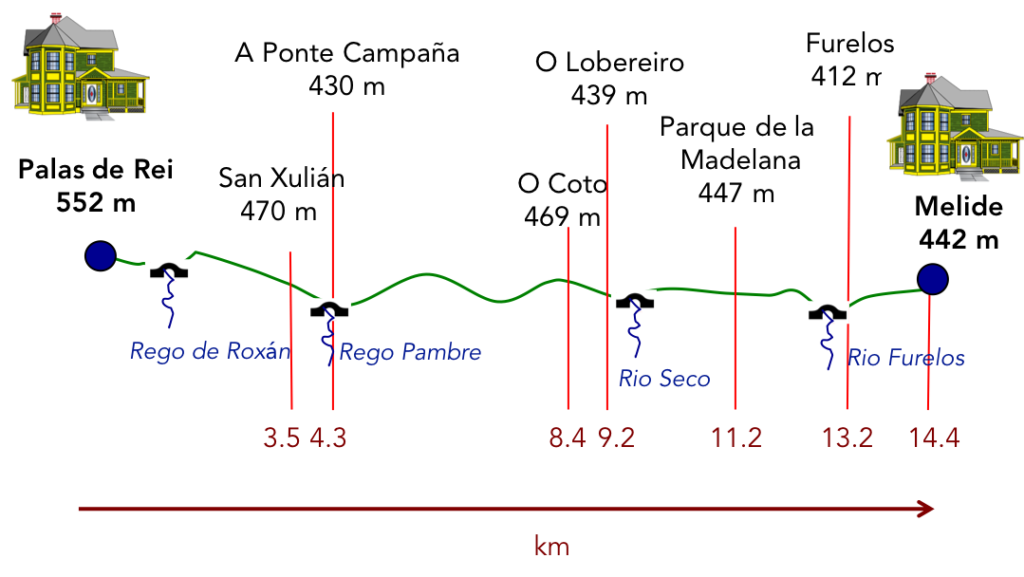

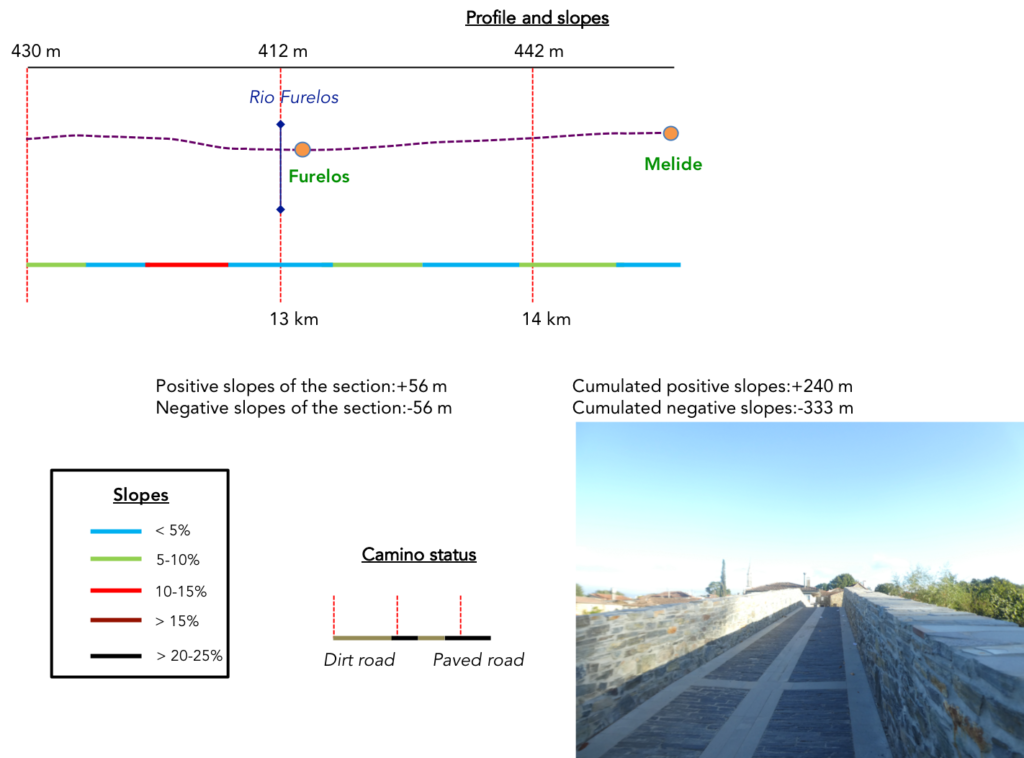

Difficulty of the course: In today’s stage, slope variations (+240m/-333m) are very reasonable. There is nothing special to report. These are just hills, some more marked than others.

Even today, as generally in Spain, the pathways are to the advantage of the walker:

- Paved roads: 5.2 km

- Dirt roads: 11.2 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

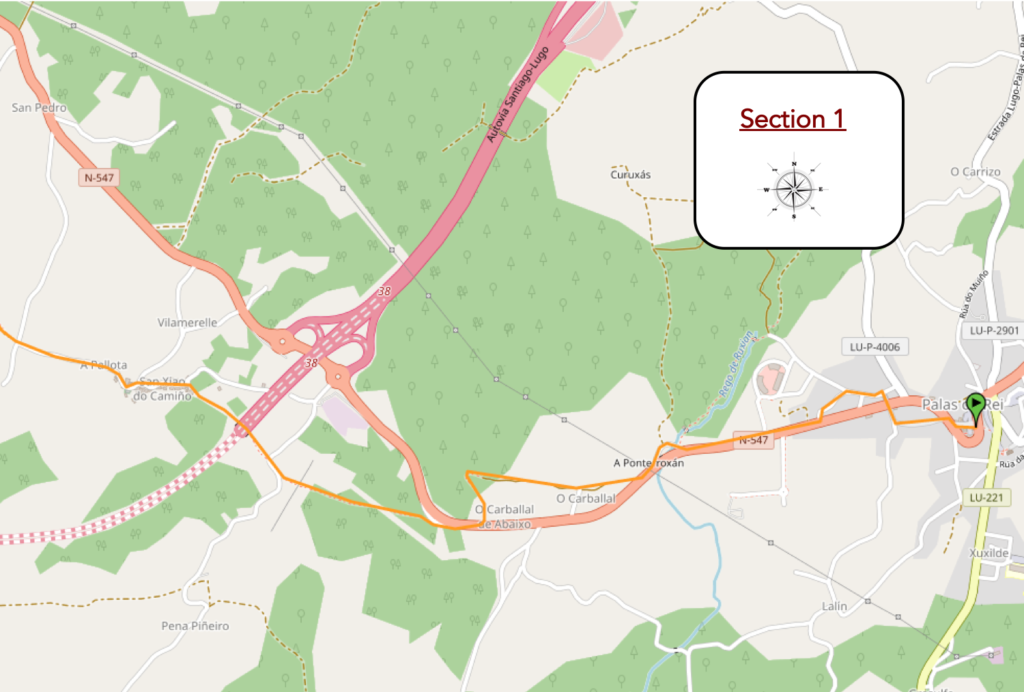

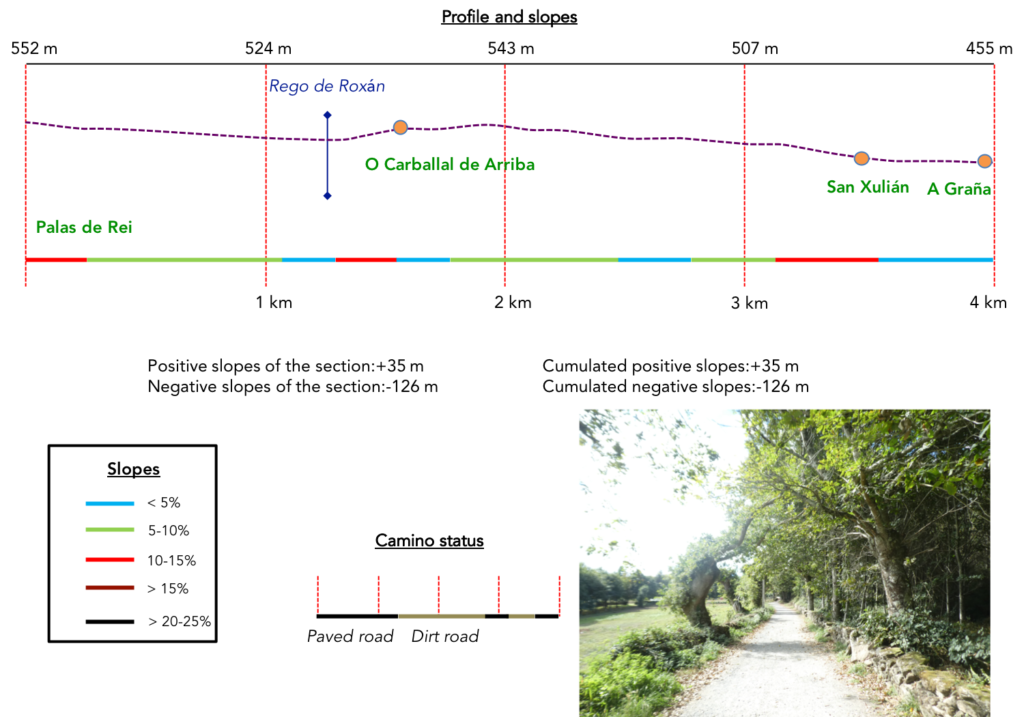

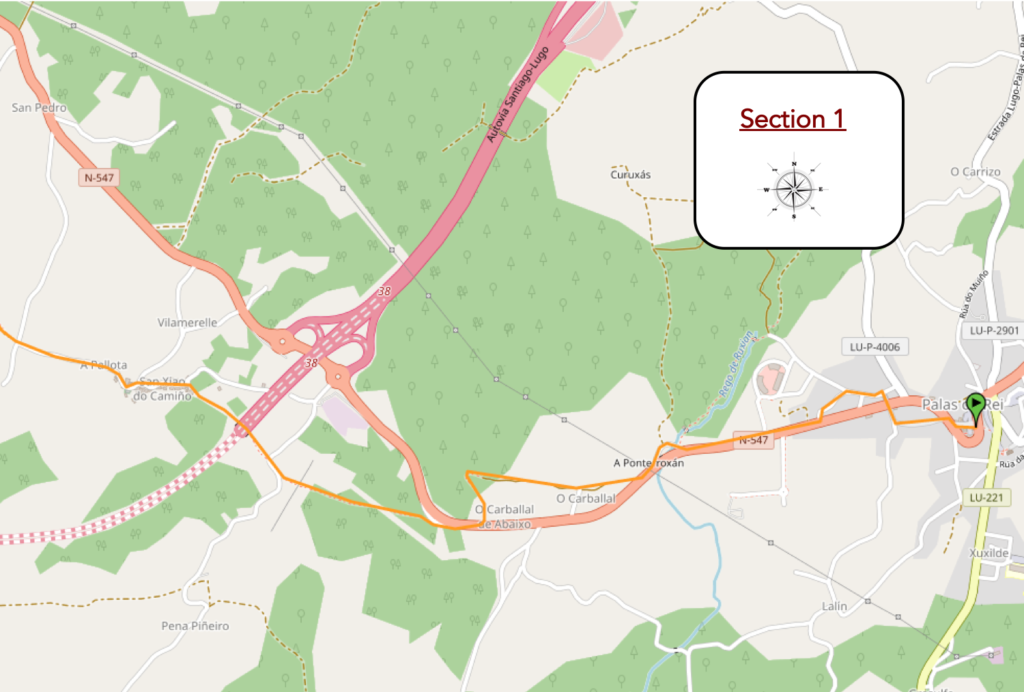

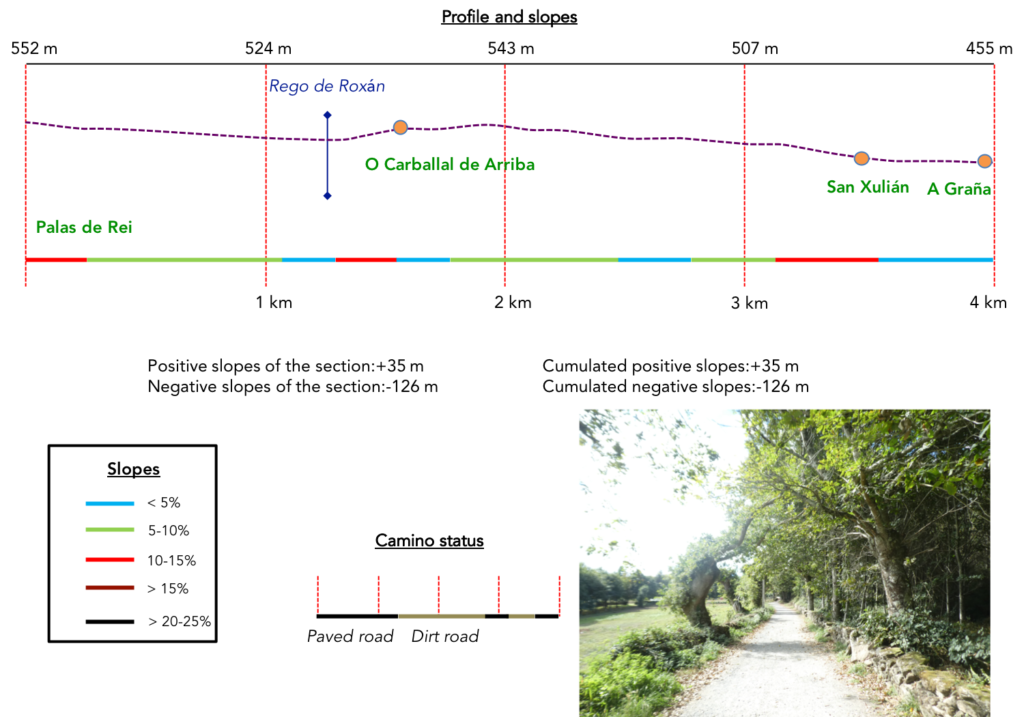

Section 1: In the forests of Palas de Rei.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: above all downhill, most of the time on a reasonable slope, with however sometimes a steeper slope.

| The Camino planners did not simplify the route out of the small town. From the rather winding streets of Palas de Rei, starting from the Town Hall, you could have just followed the N-547 road. But, the route prefers to zigzag on both sides of the road, and take you on the sloping slabs of the Rúa do Apostolo and lead you into the suburbs which is already the countryside, to cross the N-547 rod again, the main national road, which is also the Avenida de Santiago. |

|

|

| There, instead of following the N-547road, which it will find later, the Camino goes to the suburbs on the other side of the N-547 road. |

|

|

| The detour is there for you to see a stone statue of two dancing pilgrims. |

|

|

| And there, unsurprisingly, you return to the national road. For two pilgrims who dance and are not gay lads, you could have avoided the detour. The choice is yours, simply staying on the N-507 road |

|

|

| The Camino then runs along the main road, before exiting quickly to the right, onto the old N-547 road. |

|

|

You learn here that you are only 66 kilometers to Santiago. From here, the ultra present pigrimage milesotnes will punctuate your route.

| Here the road crosses the Rego de Roxán and climbs uphill at times a little steep in the oaks and chestnut trees. |

|

|

| Quickly, the Camino leaves the tar for the gravel. |

|

|

| The pathway soon reaches O Carballad de Arriba, in the middle of the hórreos. These granaries abound in the region. Here, people prefer wood to raw brick. Then, the slope stabilizes, and the pathway crosses a magnificent undergrowth, under the generous shade of large trees. |

|

|

| Puis, la pente se stabilise, et le chemin traverse un magnifique sous-bois, sous l’ombre généreuse des grands arbres. |

|

|

| It is still a sunken pathway, a corredoira so dear to the Galician people, one of those magnificent pathways that you cannot get tired of, along stonewalls covered with moss, in the shade of tall trees. It is the equivalent of the tracks of the Causses on the French Way. To see the carpets of leaves in autumn the chestnut trees are not in the review here. |

|

|

| But, the charm does not last long, because further on, the Camino joins the national road. |

|

|

| Pilgrims no longer raise an eyebrow at the sight of a new “senda de los peregrinos”. It’s almost entered into their genetic heritage. It must be said that there is not a frantic traffic on the axis. The highway passes or should pass by. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino leaves the main road to embark on a jewel of a sunken road, where the charm plays wonderfully with the effects of shadow and light. |

|

|

| This is all the truer as the oaks and chestnut trees play at overtaking the eucalyptus in height, but hardly manage to do so. |

|

|

| Here, the slope is reasonable. Further down, the pathway comes out of the woods, crosses a small country road. |

|

|

| It is then that the highway bridge appears in front of you. The highway from Lugo to Santiago is a long story, which began more than 20 years ago, and which should end in 2024, if we respect the promise. But there were many interruptions to the project, especially here in this region that goes from Palas de Rei to Arzúa. It is a sparsely populated region, therefore a low priority. Therefore, we cannot tell you if the highway here is open. We did not see any vehicles passing. But this is not proof of its non-openness. There are not many people on the motorways of Spain, outside the big cities |

|

|

| Beyond the highway, the slope is steeper in the sparse but exuberant forest to head towards the village of San Xulián. |

|

|

| San Xulián has various names: San Xulián do Camino, San Xiao do Camino or San Julián del Camino. It is a very beautiful rustic village in which the old stones flourish and the wooden hórreos flourish. One sometimes wonders how the local farmers grow enough corn to fill their granaries, with the density of the surrounding forests. |

|

|

| Here, red tiles have replaced the slates on the roofs. |

|

|

| In the center of the village stands a sober cruceiro, and next to it the small church dedicated to St Julien, closed of course. This Romanesque church dates back to the XIIth century, although it was considerably transformed in the XVIIIth century. |

|

|

| A road leaves the village, passes in front of a fountain and runs in the fields towards the hamlet of A Graña. |

|

|

| Here, farmers mainly grow corn. Because, it is necessary that the many hórreos are not there only to flatter the eye of the pilgrims. |

|

|

| At the side of the road stands a bar. Don’t think it’s closing day, seeing the empty terrace. There were pilgrims inside. It is when we walk out of step with the schedule of the mass of pilgrims that this happens. This way of doing things also allows for a more serene walk, almost always disturbed by the eternal talkers of the Camino. And many of them chatter like geese. Beyond Sarria, it is not the murmur the rule, but the din. |

|

|

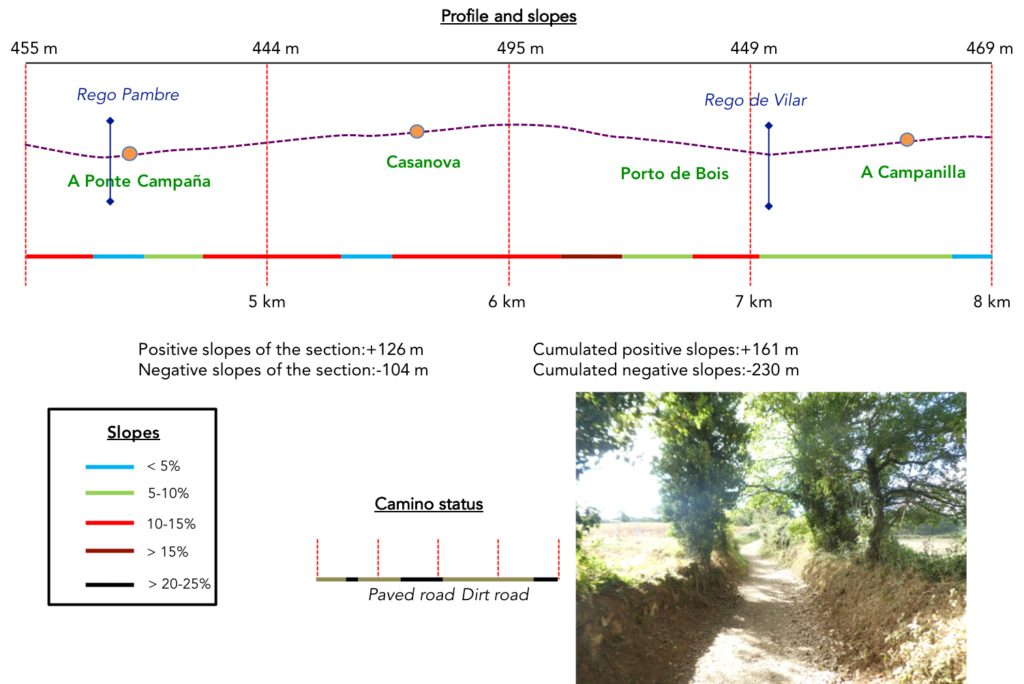

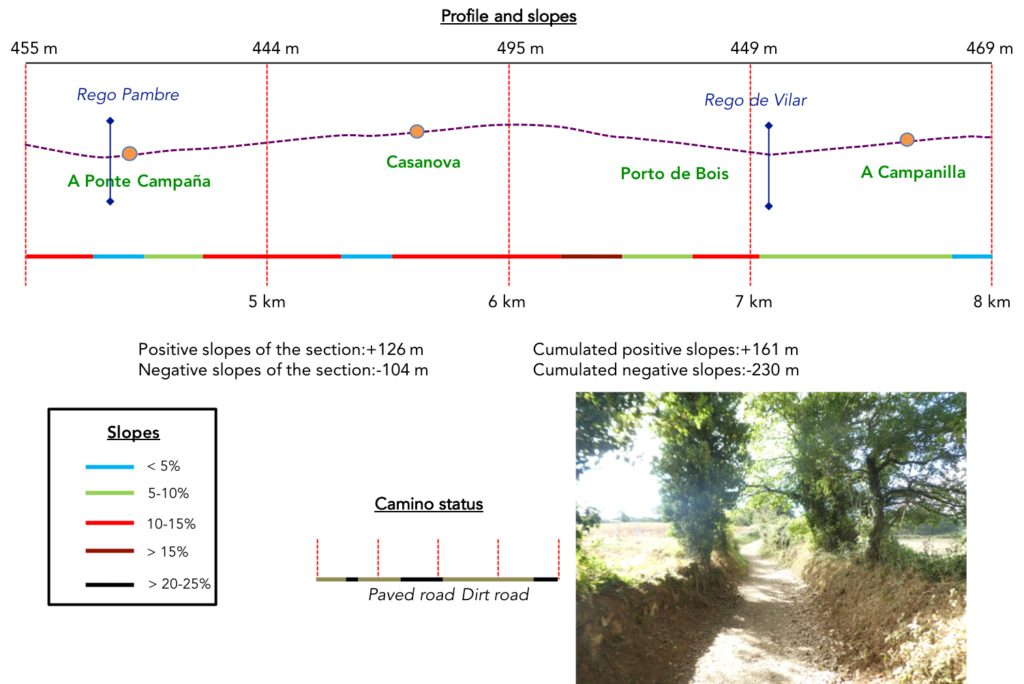

Section 2: Over hill and dale between countryside and undergrowth.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: slopes often marked, both uphill and downhill.

| Beyond A Graña, the pathway climbs further up the hill into the slopes of the undergrowth. Here the chestnut trees have somewhat disappeared in favor of the oaks. We repeat it again. In Spain, the species of oaks are very numerous, difficult to define for an unacclimated eye. But it doesn’t really matter, they are beautiful trees that provide beneficial shade. |

|

|

At the top of the hill, the gaze is fixed on two hórreos which stand here like two ancient temples. Gorgeous! In spirit, but more collected, more geometric, it functionally resembles the raccards found in the Alps.

| Here you are 63 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

| Here the pathway joins a small road that descends steeply to the Rio Pampre, an apparently slow-flowing stream. |

|

|

| At the foot of the stream is A Ponte Campaña, a small hamlet, with its “albergue” in such a charming setting that you could stay there with pleasure. It’s as big as a pocket handkerchief, and the Camino leaves the tarmac for the dirt road. |

|

|

| And the Camino starts again with a more sustained climb on the beautiful sunken road in a veritable tunnel of greenery. At this time, the chestnuts are ripe. |

|

|

| Further up, the oaks make you real guards of honor in a dark and humid world, with sometimes aligned eucalyptus straight like sentinels. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino joins a dirt road which flattens towards Casanova. |

|

|

| There is an “albergue” in the hamlet, and of course hórreos, veritable living monuments of local heritage |

|

|

| Beyond the hamlet, the road climbs a little further in the scattered woods… |

|

|

| …until you find a pathway. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway descends from the steep hill under the oaks. |

|

|

| In the meadows, elegant Rubia Galega cows sometimes graze, proudly displaying their beautiful horns. |

|

|

| Sometimes there are beautiful plantations of eucalyptus, compact and straight like drumsticks. Here, there are soon only 60 kilometers to reach Santiago |

|

|

| Further down, the slope becomes very steep for a short stretch. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the steeply sloping section, the pathway heads to a place called Porto dos Bois. |

|

|

| Shortly beyond an alley of oaks, the pathway crosses the Rego de Vilar on large slabs. |

|

|

| Here, off the track, there are a few cultures. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the Camino slopes up gently in a sunken path, sometimes quite stony. Vegetation is rich and abundant here, with oaks of all varieties casting their generous shade. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway reaches A Campanilla, its bar and its rare but solid cut stone houses. It is the last village in the province of Lugo that the Camino crosses. You are now in the province of La Coruña. |

|

|

| Here your life will change a bit. You leave the wild nature for a paved road and a little more civilization. |

|

|

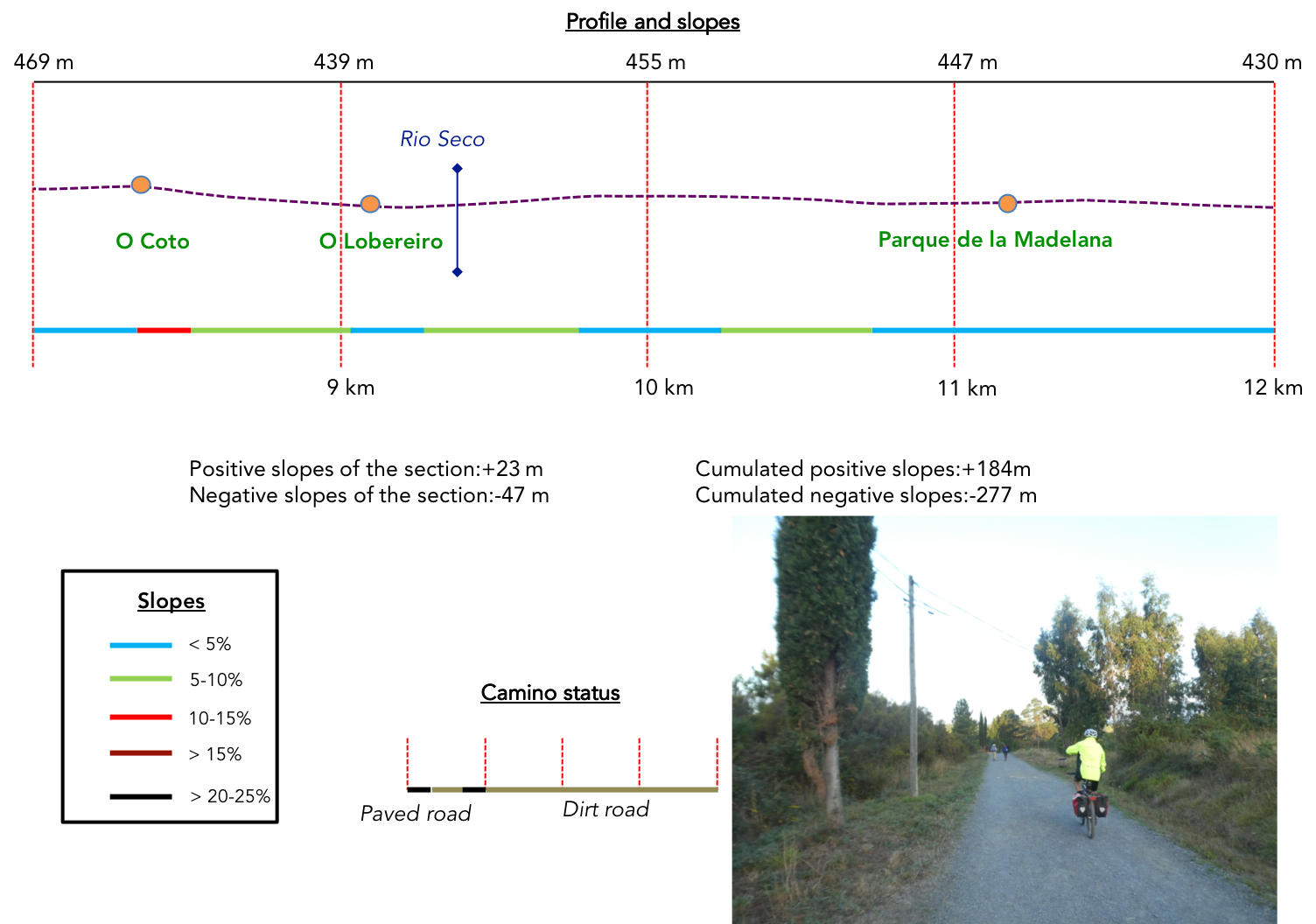

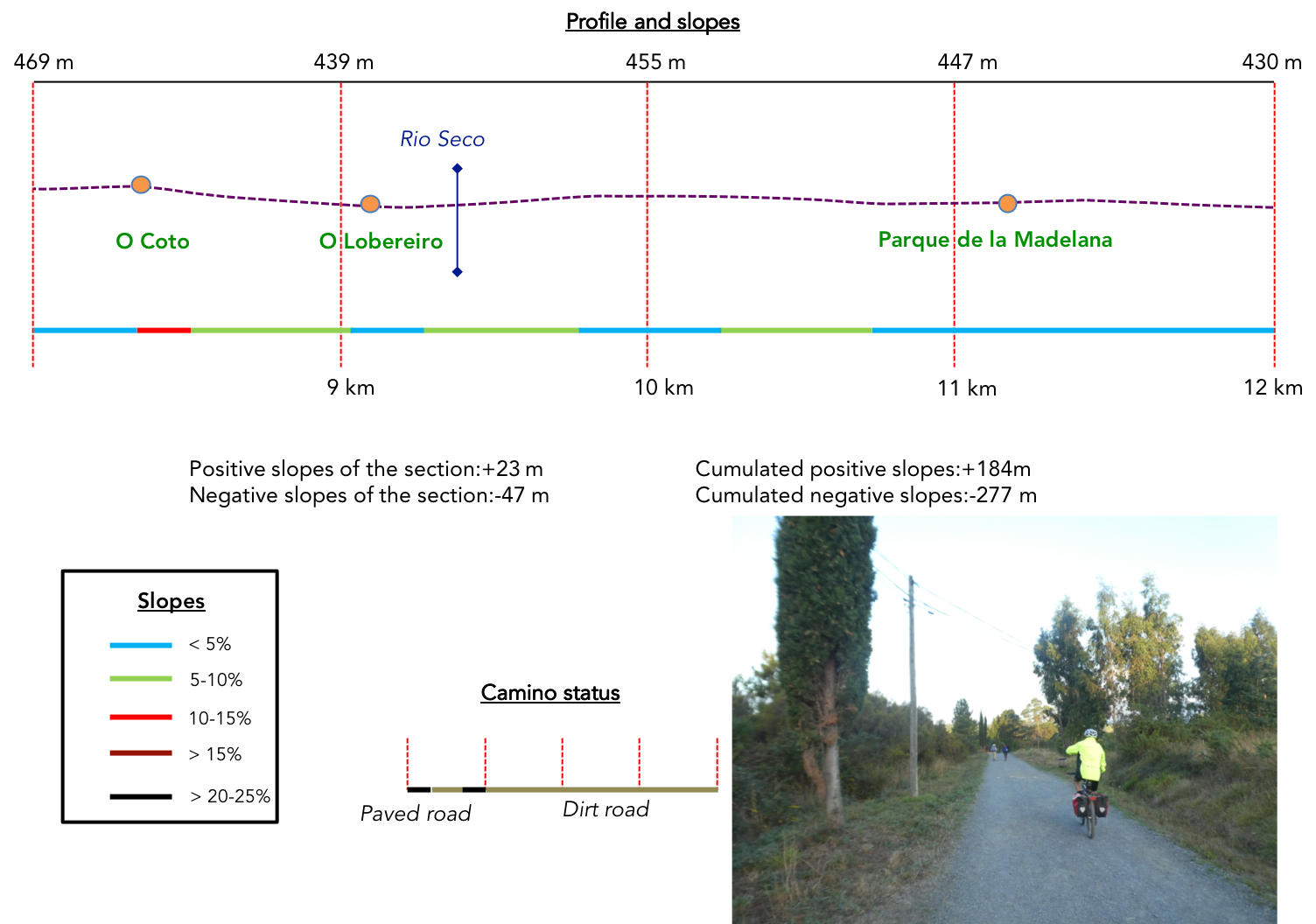

Section 3: Over hill and dale in the countryside.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Here, a bad road heads to O Coto. O Coto means border. You pass from the province of Lugo to the province of La Coruña. Specifically, you enter the municipality of Melide. |

|

|

| Here, it is a fairly inhabited region, more touristy, on the edge of the N-547 road. |

|

|

| O Coto has a developed infrastructure for pilgrims, and many pilgrims stop here. A rather severe St Jacques watches over the village. |

|

|

| Further ahead, a beautiful and delicious pathway under the oaks descends from O Coto. |

|

|

| It arrives on the slabs at Leboreiro. Leboreiro means “land of hares” (liebres). In the Middle Ages, it was called Campus Leporarius, as indicated by the Codex Calixtinus. |

|

|

A sober and stripped cruceiro welcomes pilgrims in the main street of the village

| It is a beautiful village flanked by traditional stone houses, some better preserved than others. The village had its heyday between the XIIth and XIII centuries, when it offered important services to pilgrims. It subsequently declined. |

|

|

| In the village, there are granaries with the same use as the hórreos. These granaries are called cabaceiros or cabazos. They are kinds of bells, intertwined with branches of chestnut, oak or willow, used mainly to preserve fruit, especially squash. |

|

|

The Romanesque church of Santa María from the XIIIth century was rebuilt in the XVIIIth century. It was built to house a statue of the Virgin. According to legend, the villagers found the statue near a local fountain. For several days, they placed the Virgin on the altar of their church, but the Virgin returned to the fountain. Finally, they decided to honor the Virgin by sculpting a tympanum and dedicating the church to her. At that time, the statue did not move from the church.

| Just beyond Leboreiro, the paved pathway crosses the XIVth-century Puente María Magdalena (Magdalena Bridge), a medieval humpback bridge over the Río Seco (dry river), which, as its name suggests, is not heavily waterlogged. This is where an old Roman road once passed. |

|

|

| Beyond the bridge a gravel pathway climbs gently through poplars, broom and heather towards an industrial district. |

|

|

| Further on, it approaches the national road again. |

|

|

| But, it returns inland, first in a kind of moor with orchards… |

|

|

| …then in a neighborhood of warehouses, where you see the wines of the Ribeira Sacra, amazing red wines unknown outside of Spain, wrongly. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the gravel pathway approaches the N-547 again. |

|

|

| It crosses a trickle of water to find itself at the entrance of Madalena, the gigantic industrial polygon of Melide. Big, for such a small provincial town. |

|

|

| The pathway runs along the park for a long time under the horse chestnut trees, close to the national road. |

|

|

| Our cycling friends pay little attention to the industrial buildings of St Gobain, and company. |

|

|

| At the exit of the park, the gravel pathway remains under the horse chestnut trees near the N-547 road, which shows a little more activity here. |

|

|

| Further on, at the end of a long straight line, the pathway turns and leaves the main road. |

|

|

| Here you are 55 kilometers to Santiago. |

|

|

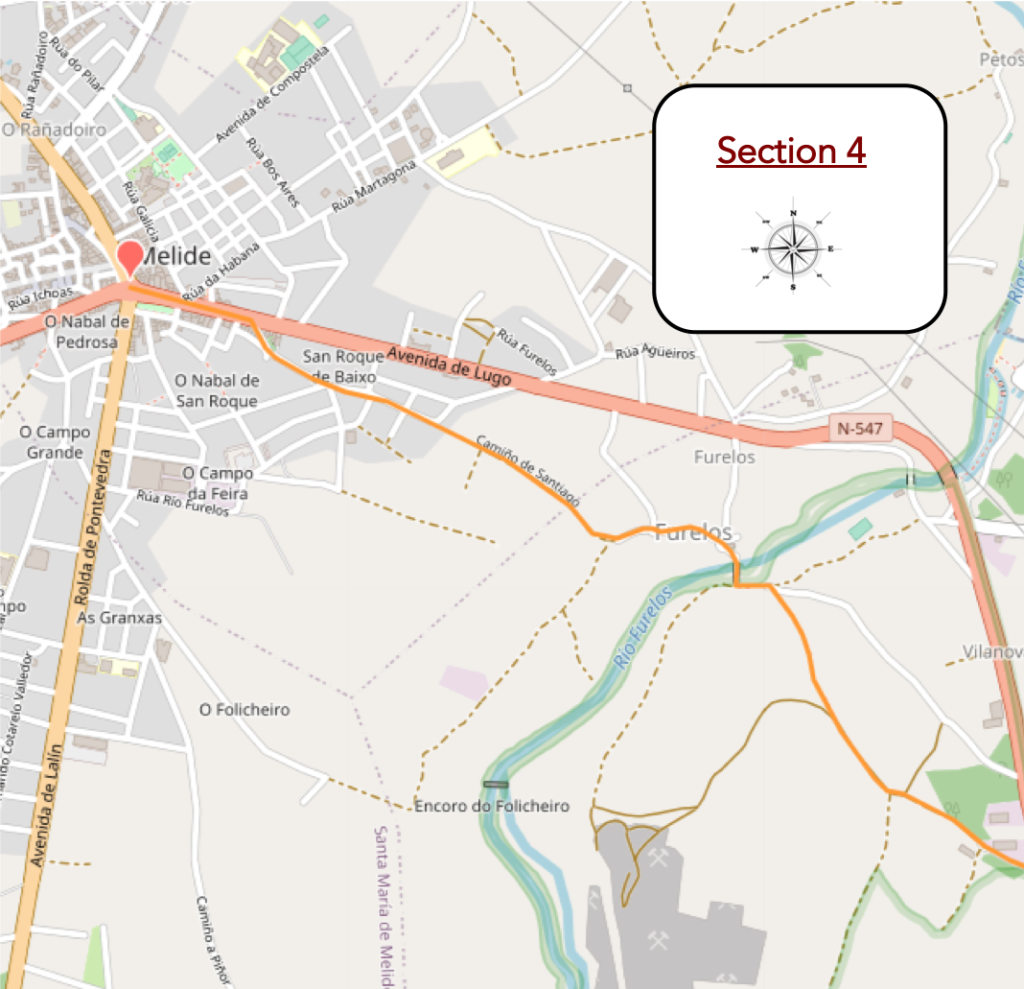

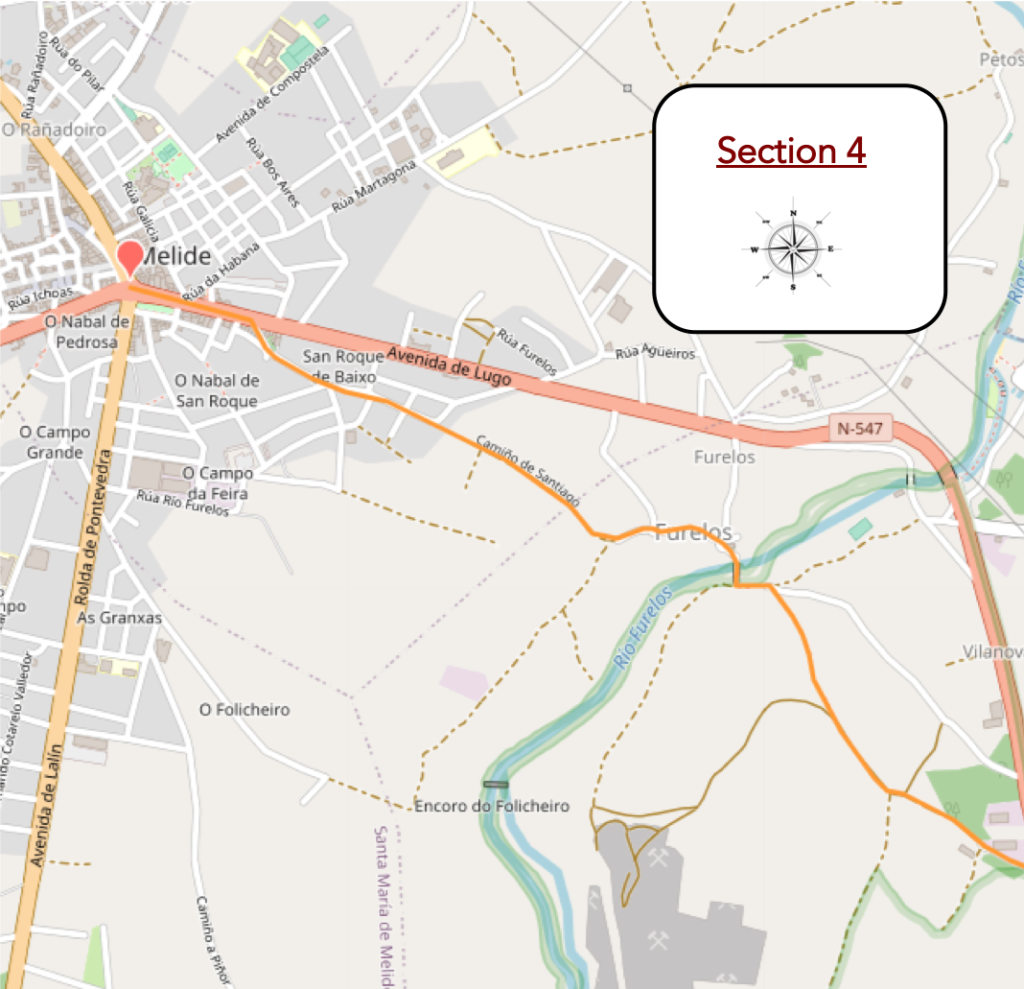

Section 4: Towards Melide.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some reasonable slopes.

| Further on, the pathway runs in front of plantations of poplars, eucalyptus and pines. |

|

|

| Then, it begins a descent into the wilderness. |

|

|

| Nature is beautiful and cheerful here. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope becomes steeper in the sunken lane, dark as night. |

|

|

| IHere, which is not the rule, the eucalyptus mingle with the oaks. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway joins a small road. |

|

|

|

|

We are going to make a small parenthesis here. This is where the Camino primitivo can join the Camino francés, before Melide.

The Camino primitivo (primitive path) is one of the oldest routes in Santiago de Compostela. The starting point is in Oviedo and the route stretches from Asturias to Galicia through small villages. The route is a little more difficult than that of the Camino francés. The Camino primitivo is important for the history that links it to the Cathedral of Santiago. We must go back to the time of ancient Gallaecia, a territory formed by the communities of Galicia, Asturias and León, which was ruled by Alfonso II at the beginning of the IXth century. He is considered the first pilgrim. In 813, Alfonso II traveled from Oviedo to Santiago, after the discovery of the tomb of the apostle Saint James. After seeing the tomb, it was Alfonso II who ordered a church to be built on the site, giving birth to hundreds of years of Camino de Santiago history.

So, of course, the number of pilgrims will increase further on the route. According to Spanish statistics, on average, more than 50 people per day follow this route.

Parenthesis closed, the Camino (inglés and primitivo) is opposite the very beautiful medieval bridge, the Ponte Velha (Veux Bridge) over the Rio Furelos.

| This bridge, mentioned in documents from the XIIth century, was partially rebuilt in the XVIIIth century. It is 50 m long and 4 m wide, with four unequal round arches. This bridge is just awesome. |

|

|

| On the other side of the bridge, the village of Furelos once belonged to the Hospitallers of San Juan. There were formerly hospitals for pilgrims, which have now disappeared. We also know that much of this area was inhabited long before the Roman conquest. The Camino crosses a beautiful village, authentic, on the slabs |

|

|

| The Church of San Juan (San Xoán) dates back to the XIIIth century. Of the old Romanesque church, only the south wall remains, with its eaves. The present church was rebuilt in the XXth century. |

|

|

| The Camino gradually leaves the village all in length. |

|

|

| You’ll quickly see Melide a little above. |

|

|

| The approach to the small town is not the most interesting there is, we will put it that way. The city has placed large photographs here to fill a fairly empty space. |

|

|

| Further on, tar replaces the wide gravel road in the suburbs. |

|

|

| Shortly after, track organizers put slabs to do more of the Camino de Santiago. |

|

|

| Soon the Camino joins Avenida de Lugo, in fact the N-547 road, in the city center (7,500 inhabitants). |

|

|

| The XVIIIth century Church of San Pedro y San Roque (Capela de San Roque) was built with the stone of two old medieval churches, that of the parish church of San Pedro and the original Capela de San Roque, from the XIIIth century century. When the church of San Roque fell into disrepair, its Romanesque door was moved to San Pedro. The current Chapel of San Roque was built in the last century.

On the left side of this church is the XIVth century Gothic stone cross, the Cruceiro do Melide, considered the oldest in Galicia. However, only the top half is original, with the lower column and stone base as modern additions. On the granite cross at the top, the front face represents Christ; the reverse depicts a scene from Calvary. |

|

|

| Further on, at the big crossroads, the Camino heads towards the old town. |

|

|

| This is where the second church in the city is located. The XIIth century Church of Santa María de Melide, declared a national monument, is a jewel of the Galician Romanesque style. It has 2 decorated entrances, one of which, the door of the main facade, has a simple tympanum. The west door has a triple archivolt with unusual medallion designs and intensely decorated capitals. |

|

|

If you are staying here, all that remains for you to fill your leisure time is to taste the pulpo a la Galega. The pulperias, octopus restaurants, of Melide have the reputation of having the best prepared pulpo in Spain.

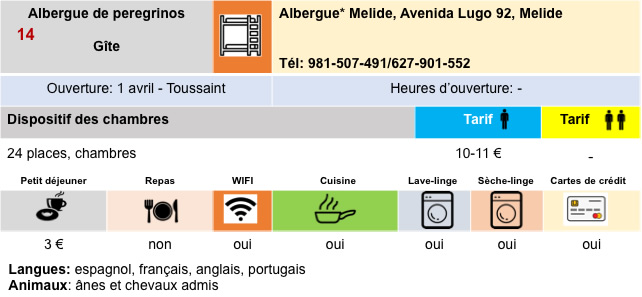

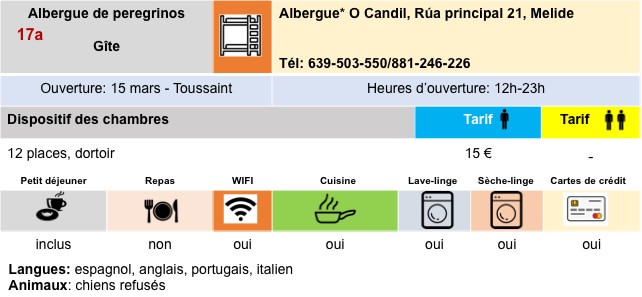

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 13: From Melide to Arzúa |

|

|

Back to menu |