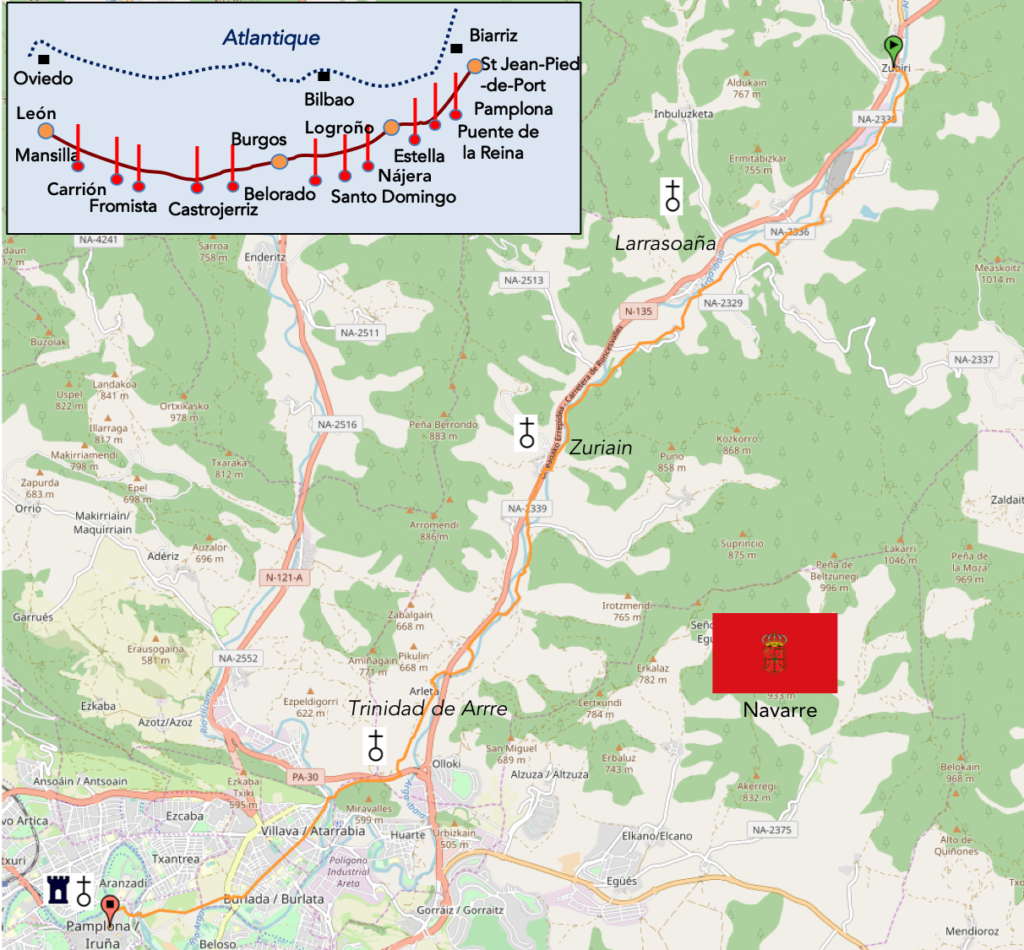

The axis today is the Arga River

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

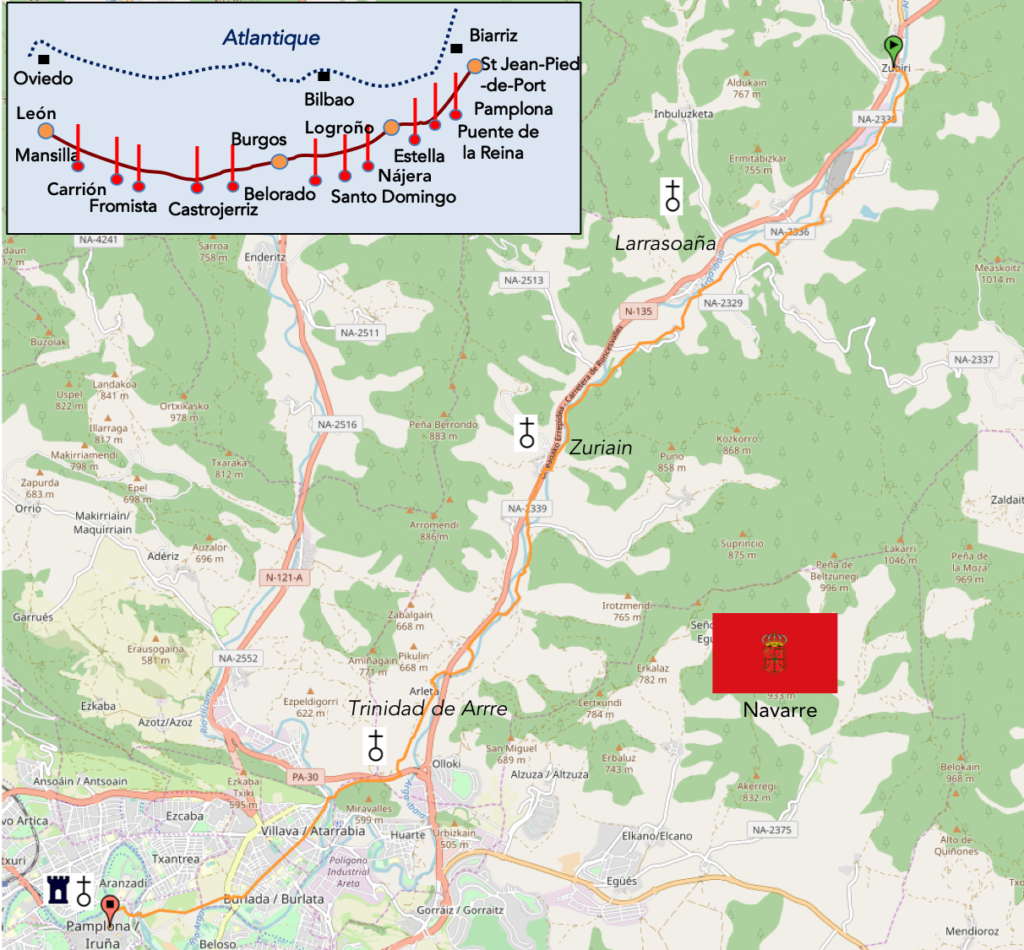

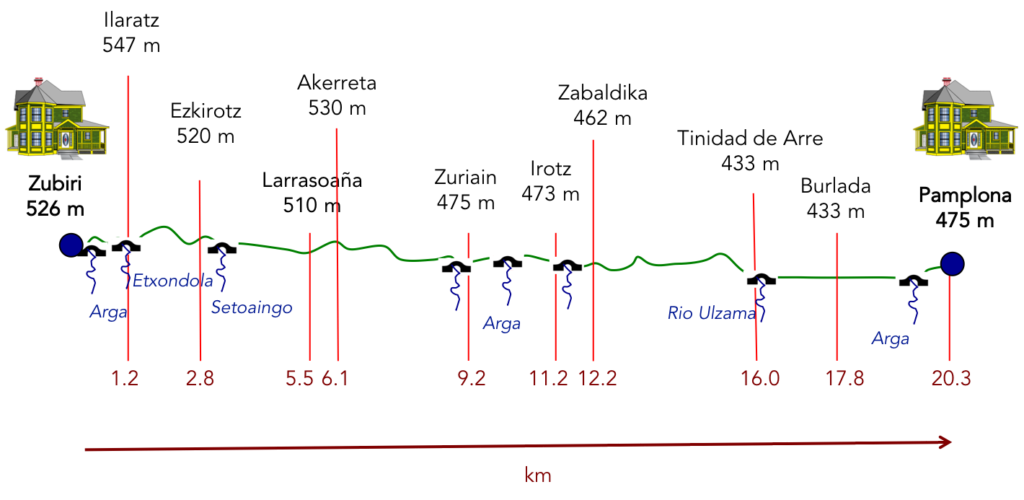

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-ronceveaux-a-zubiri-par-le-camino-frances-37582828/

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

When you walk on the Camino francés, you will quickly see, rather you will hear that Americans are legion here. Why? This is actually because a movie that has been very successful in United States, The Way, a film by Emilio Estevez, which features a comfortable American doctor, who urgently travels to France where his son Daniel has just disappeared. He is asked in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port to ascertain the death of his son during the course to Roncesvalles. Of course, the relationship between father and son had to be complicated to create a story. What did the scriptwriter do? He sent the father to do the Santiago track. Simple, no? Of course, the doctor has a difficult character and it takes a lot of time to open up to others, to Jack the Irishman, to Sarah the Canadian, or to Joost the Dutchman. They will discover each other gradually, with a lot of clashes and misunderstandings. They will arrive at Santiago and then at the seaside where the hero will throw the ashes of his son to the sea, under the gaze of his companions. The film, produced in 2010, was a resounding success in America and Spain, and later in France. Some critics have seen a pious idea, as many pilgrims who still go on the track as an occasion for redemption. Others have seen a psychiatric analysis of father-son relationships, citing the superficial relationships among the participants in the trip. But critics, for the most part, have defined the film as a commercial, a stereotypical view of what has become The Way today. It is for them theatre, ritornellos added to the legend of the way. This point of view is not wrong, alas. The French Camino has certainly lost much of its religious component. Let’s not forget that the film was made by Americans, and when you lived there, you know that much of the relationship between people is very superficial. You can spend an evening with an American and meet him again the next day. He will not remember seeing you. So, you will find Americans on the track and you will see that it does not change. As in the movie, the Americans here only open to English speakers. And so little, that’s enough for their happiness.

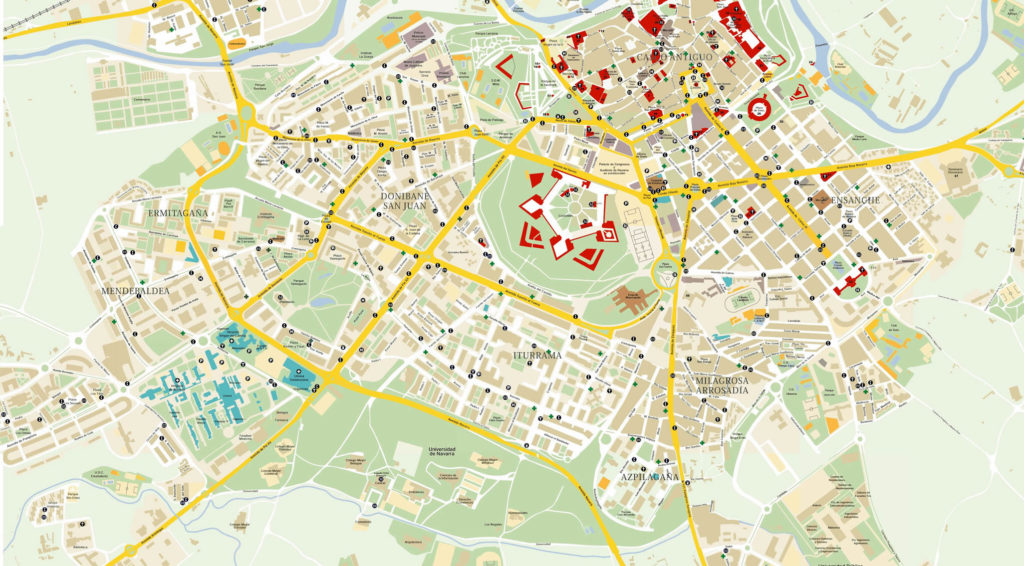

The stage of the day is a beautiful walk in the narrow Arga valley. The track twirls on both sides of the valley on small hills, to reach Pamplona When you’ll arrive here, in the fortress, remember that many war events have happened here. Of course, you can go straight into your « albergue » and ignore everything about this story. But it’s always interesting to have a little idea of the places you cross. So, here are some brief elements to enlighten the subject. Pompey, the Roman general would have established here a city towards 75 BC giving it the name of Pompaelo, which would have given Pamplona. Beyond the roman period, they would have erected important ramparts here, about 67 towers. Then there were many invasions, first the Franks, then the Arabs. But the greatest damage was caused by Charlemagne at the end of the VIIIth century, who razed the ramparts. In retaliation, the Basques trapped Charlemagne’s army, including the legendary Roland, at Roncesvalles.

At the end of the IXth century, the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Navarre. The city developed then especially in the Middle Ages, thanks to the Santiago track. At that time, the city consisted of three distinct boroughs. The most important was the Navarreria, around the cathedral, with the king, the court and the clergy. The other two boroughs were those of San Saturnio and San Nicolas, populated by artisans and merchants from the northern Pyrenees. Each town had its own fortifications. We will tell you a little more about the history of Navarre later, in the next stage. Let’s just say that Philip II, fearing the French, built this huge fortress around the city. Many walls still exist.

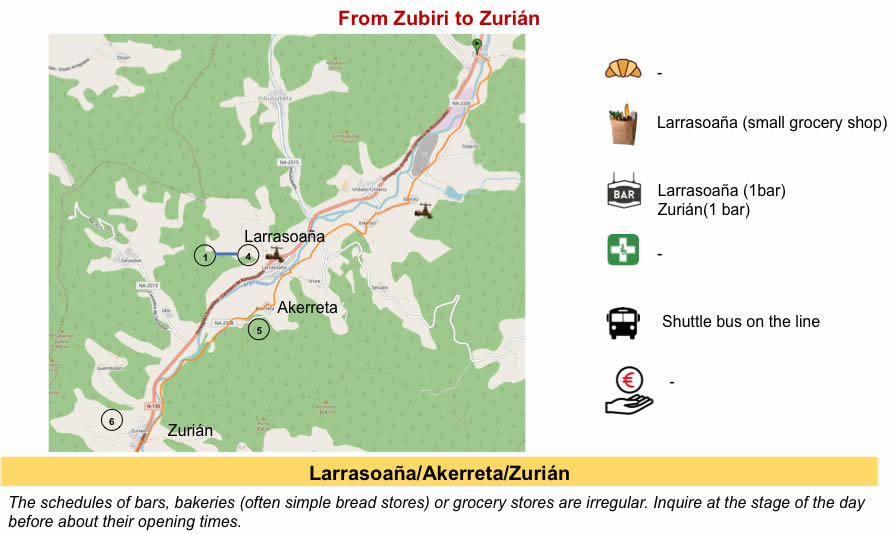

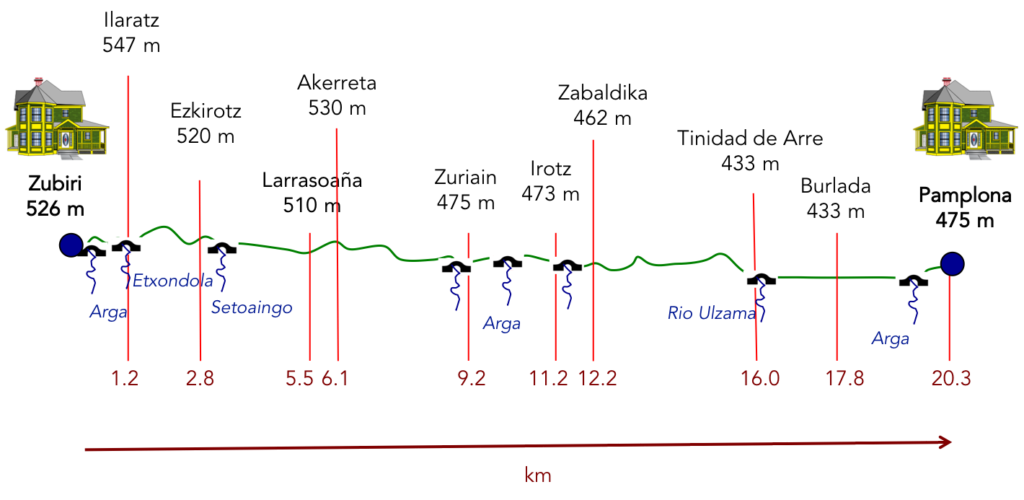

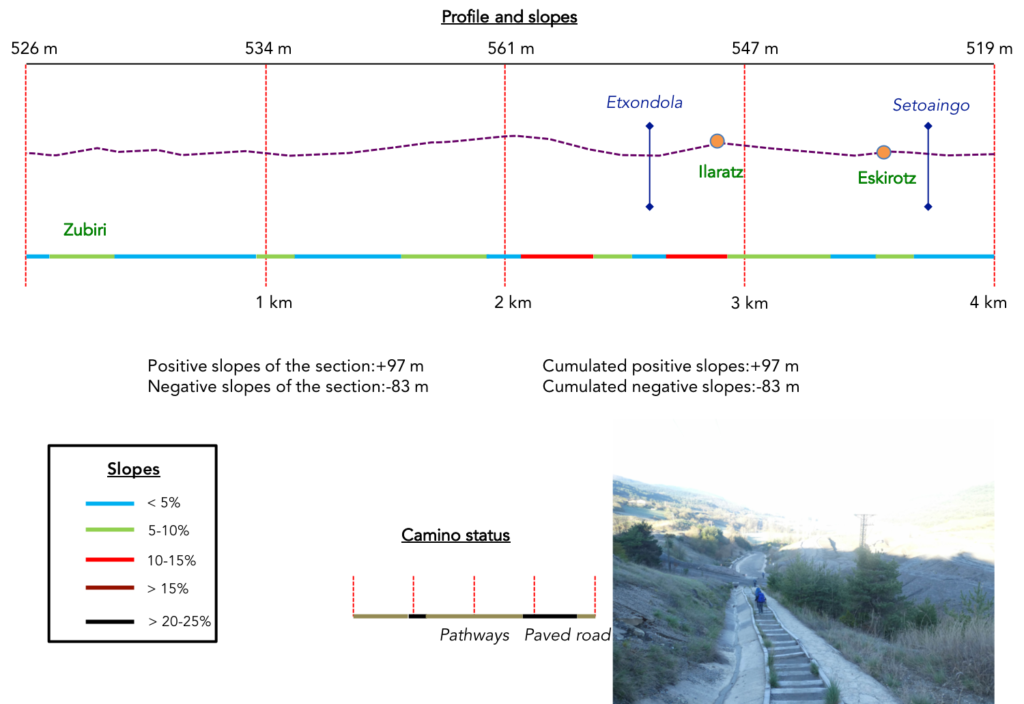

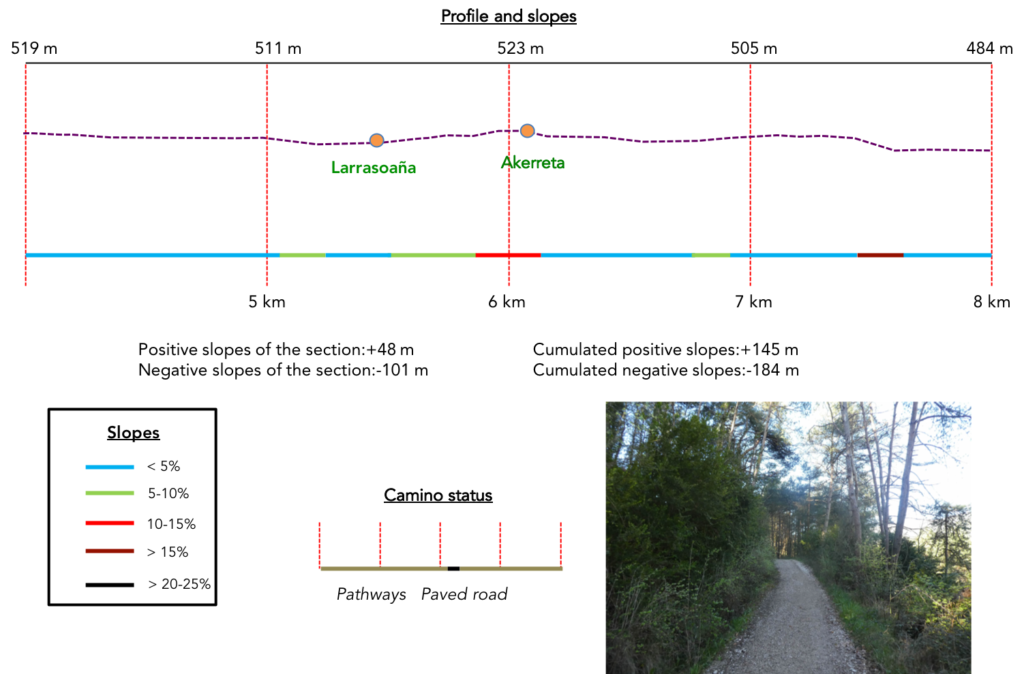

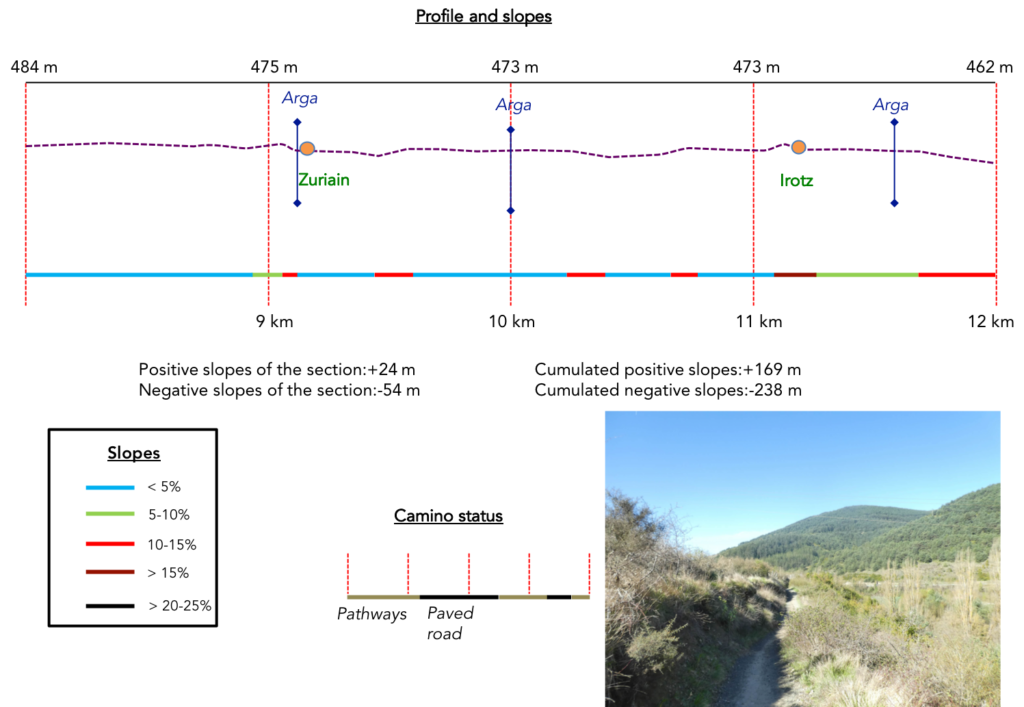

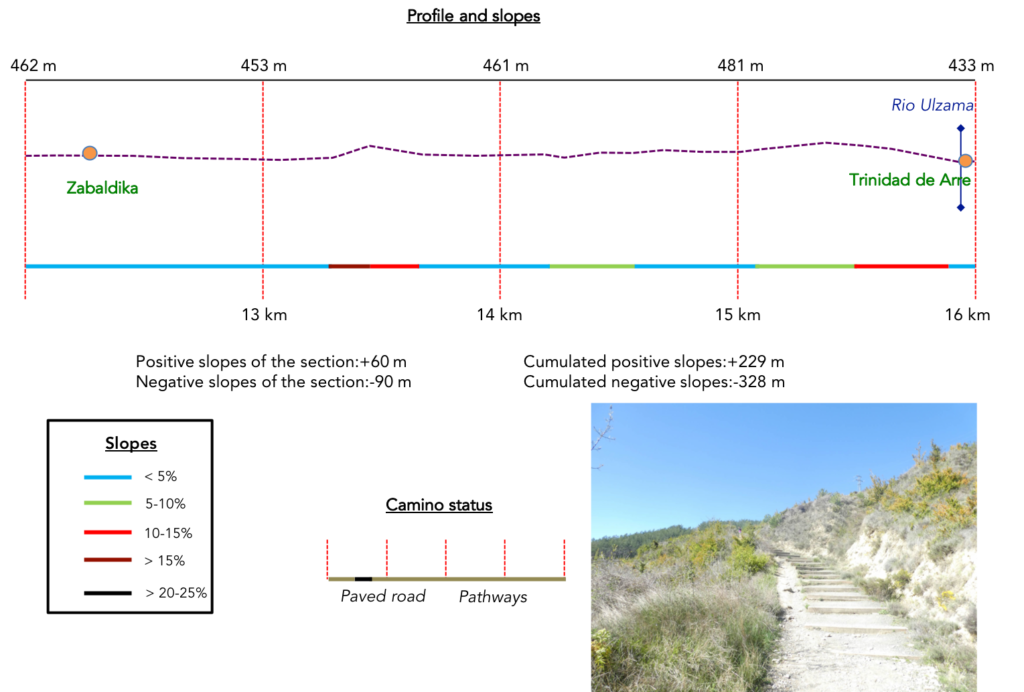

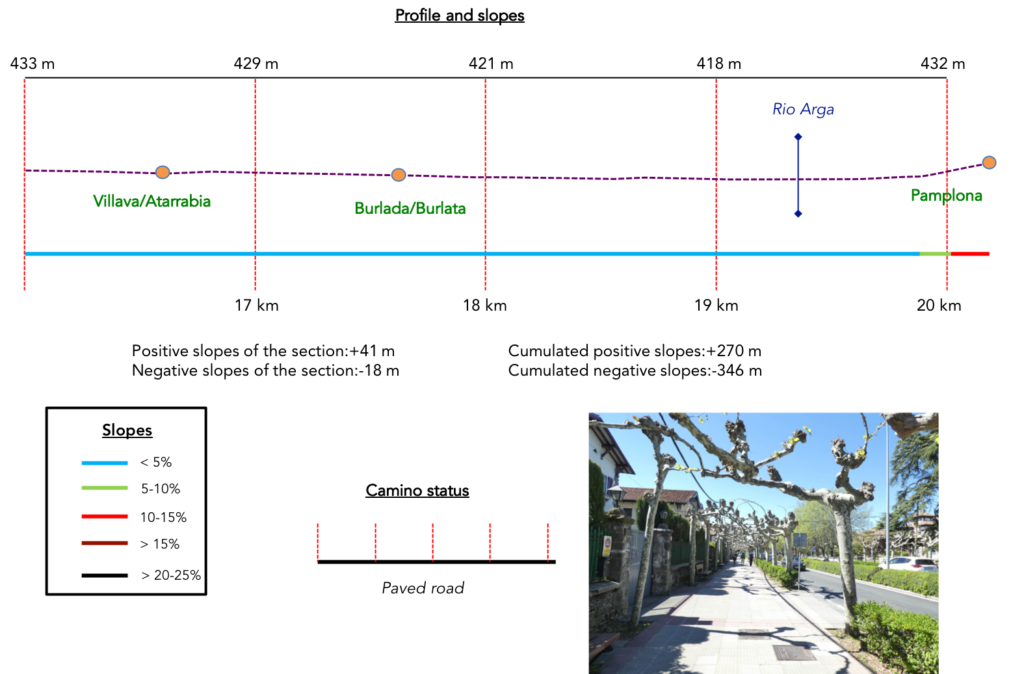

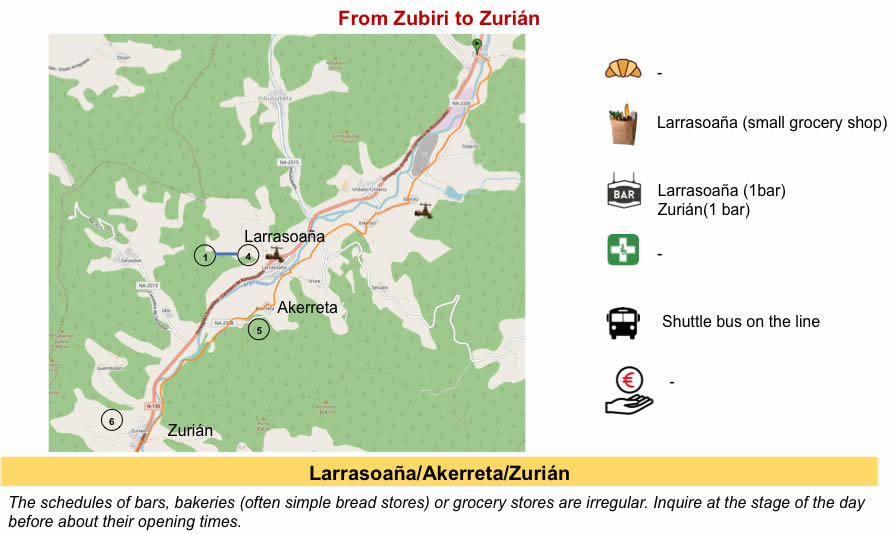

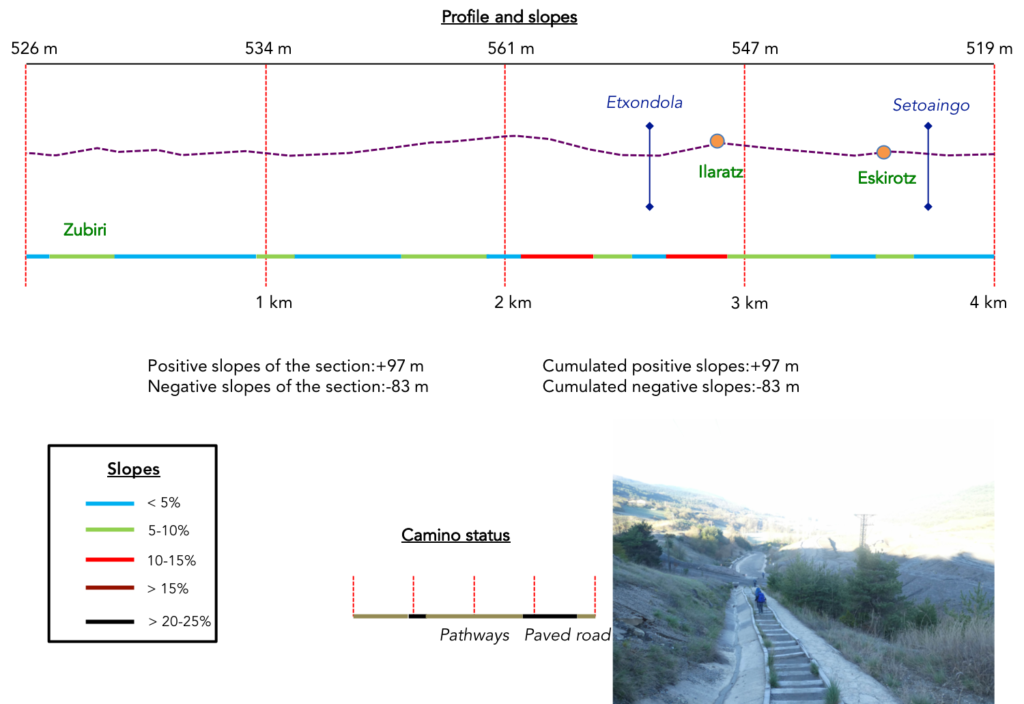

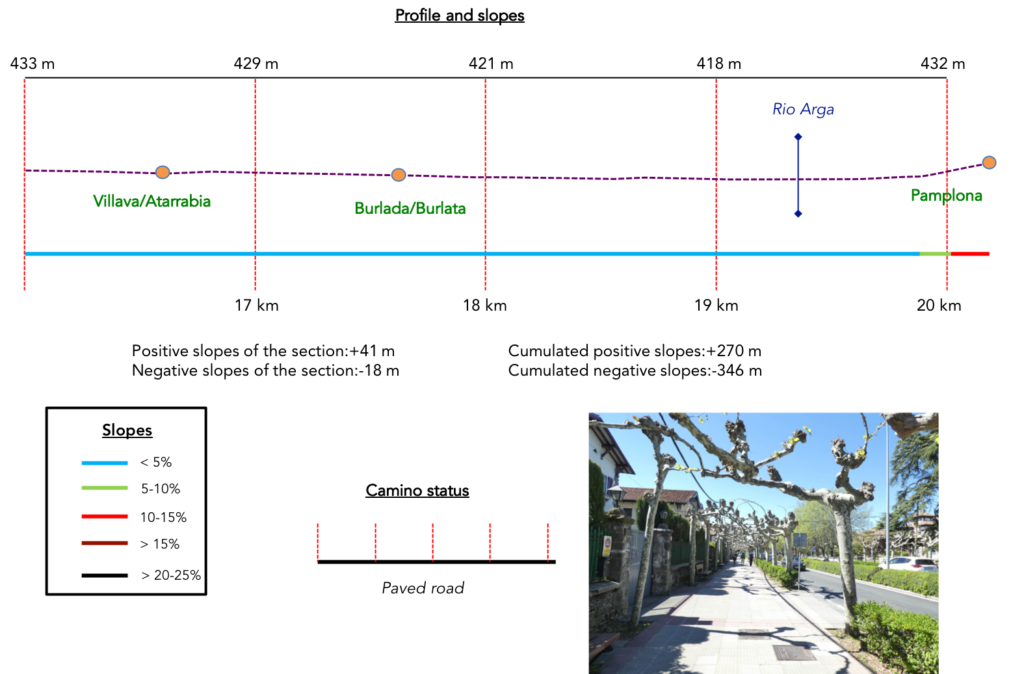

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+270 meters /-346 meters) are very low in the day’s stage. There is not much to report as difficulties. However, let’s mention some passages a little more sustained. First, at the beginning of the stage you’ll note the passage beyond the gravel pit towards Ilaratz and the descent on the slabs to the Arga River before Zuriain. Then, on a very short stretch, the route climbs toughly in the bush beyond Zabaldika. The following is no problem.

In this stage, there is a lot of road, because you cross the city. But, most of the trip is on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 7.0 km

- Dirt roads: 13.0 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

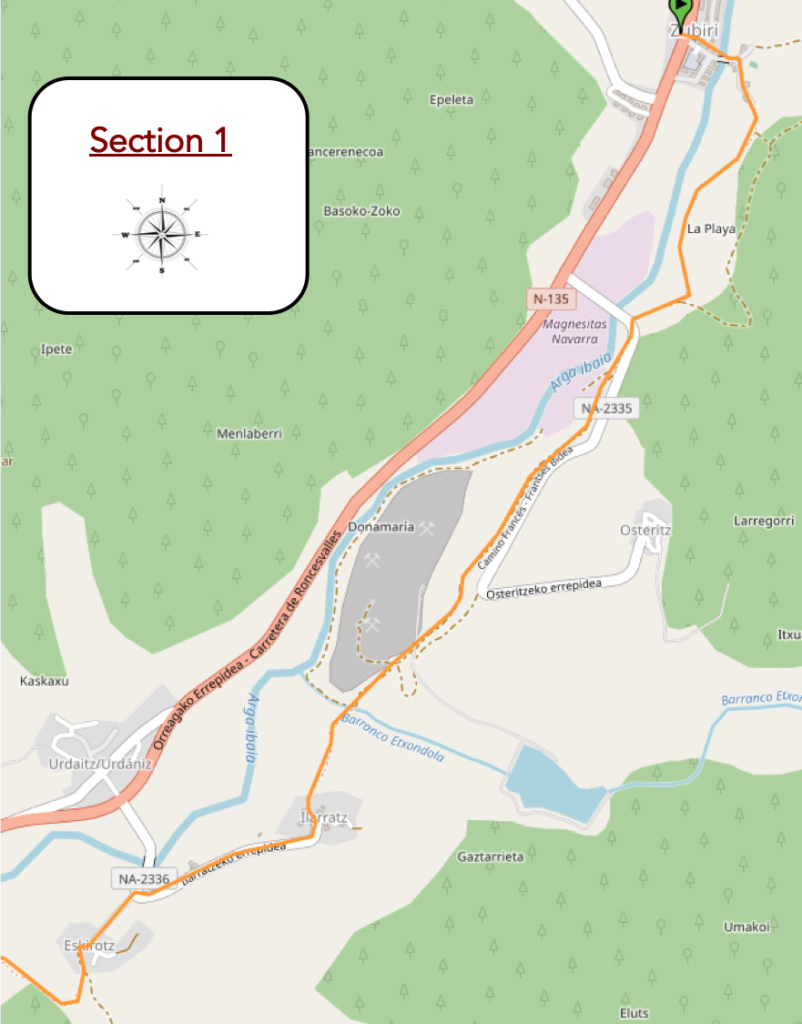

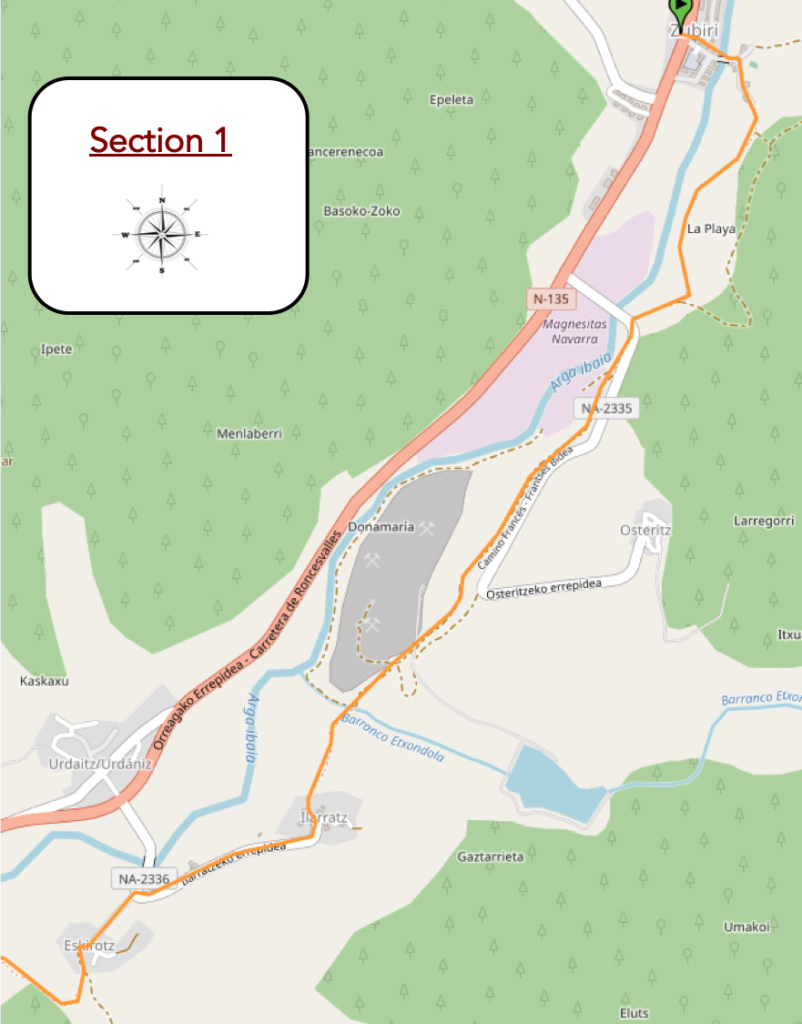

Section 1: A huge gravel pit on the way.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, except around the crossing of Extodola brook and the climb to Ilaratz, but the slopes never exceed 10% to 15%.

| Today, the weather promises to be splendid in Navarre. It is in the early morning, shortly before the sun rises, that usually pilgrims leave Zubiri near the stone bridge over the Arga River. |

|

|

| The direction is that of Larrasoaña, 5.5 kilometers from here. The stage is not long until Pamplona. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses a few houses in the village, on the other side of the river, and immediately heads to the meadows, crossing a small trickle of water. |

|

|

| It then climbs undulating in the undergrowth and meadows, hesitating between stony dirt and small slabs, which sometimes generously pave the way to avoid stones and mud, when the slope becomes steep. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway undulates again to descend towards a gigantic factory, which occupies almost the entire valley. |

|

|

| A road then slopes up a long way along the factory. The sun appears on the horizon. |

|

|

| Further up, the Camino leaves the road for a pathway that runs into the tall grass. Looking back, you measure the immensity of the factory. Here, magnesium oxide is extracted, for industrial and food use. Enjoy your lunch ! On hectares, there is only mineral waste and the pathway zigzags in the middle of this nice little polluted world. |

|

|

| Everything is gray here, and the pathway runs along the ridge for a while. In front of you opens the Arga plain. |

|

|

At the end of the ridge, the pathway will still take advantage of the exotic beauty of the industrial site, descending on stairs in the plain.

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway breathes a little, crosses the Etxondola stream, which must be polluted to the marrow of the waters. It then resumes his rights of life on the slabs of a pathway that climbs steeply towards the village of Ilaratz under the stunted beeches. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway slopes up the side of the hill… |

|

|

| …until you reach the hamlet and its solid stone houses. |

|

|

| At the exit of the hamlet, the Camino descends from the hamlet on the road. Here, there are only meadows, no crops. Breeding must be the rule. |

|

|

| The road heads to the hermitage of San Lucia, which looks more like a castle than a church. This building dates back to the XIth century and was transformed in the XVIth century. But the baptismal fonts are still from the period. In historic religious buildings, you will most often find guides who will tell you the history of the place and who will stamp your “credencial”. If there is no guide, you will also often have the opportunity to stamp your pilgrimage passport yourself. |

|

|

| Shortly beyond the hermitage, the road heads to the hamlet of Ezkirotz. |

|

|

| Behind the few houses in the hamlet, the pathway slopes down into the undergrowth to cross the Setoaingo stream on a footbridge. |

|

|

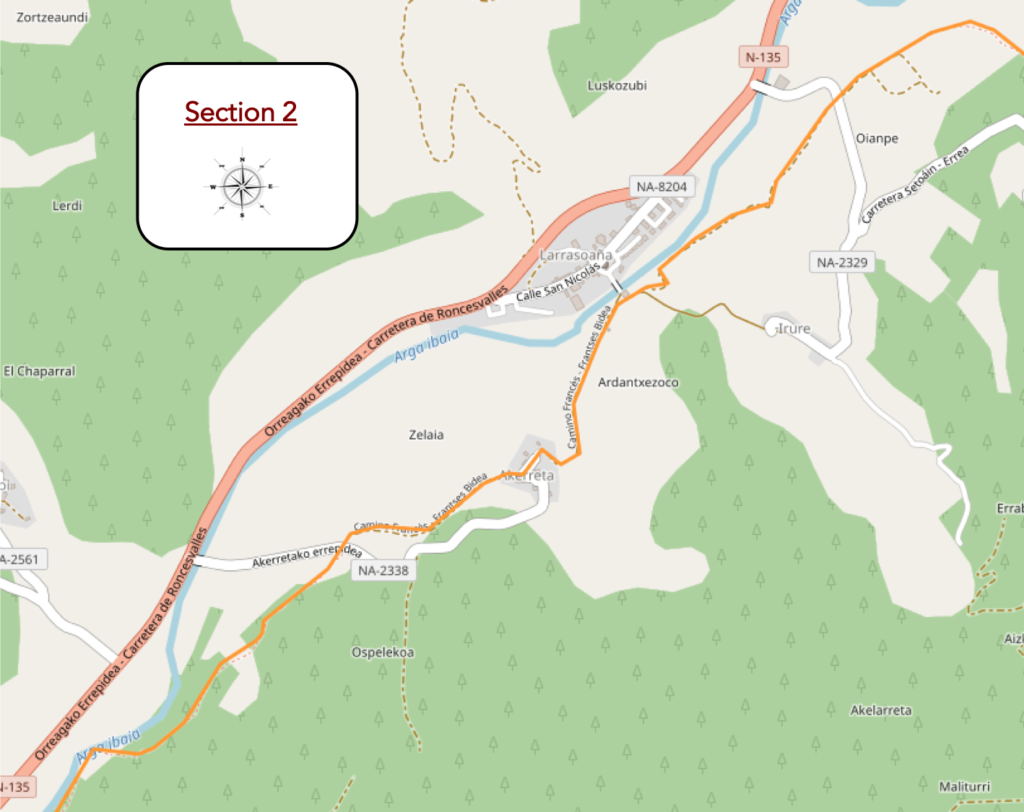

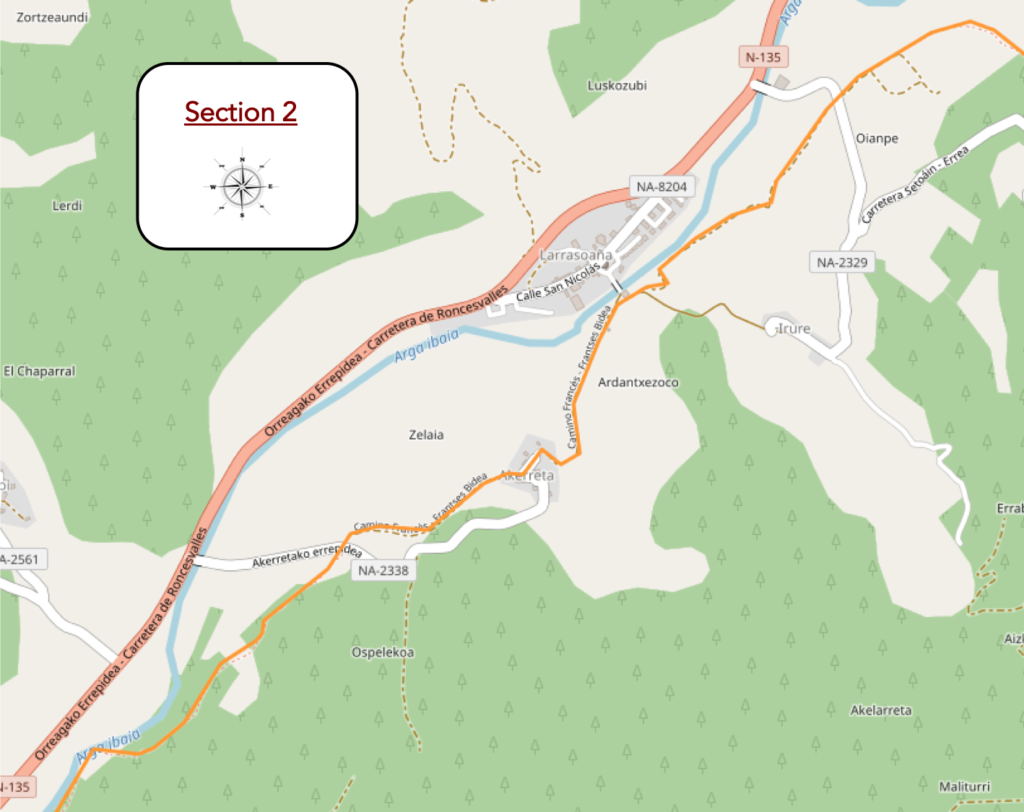

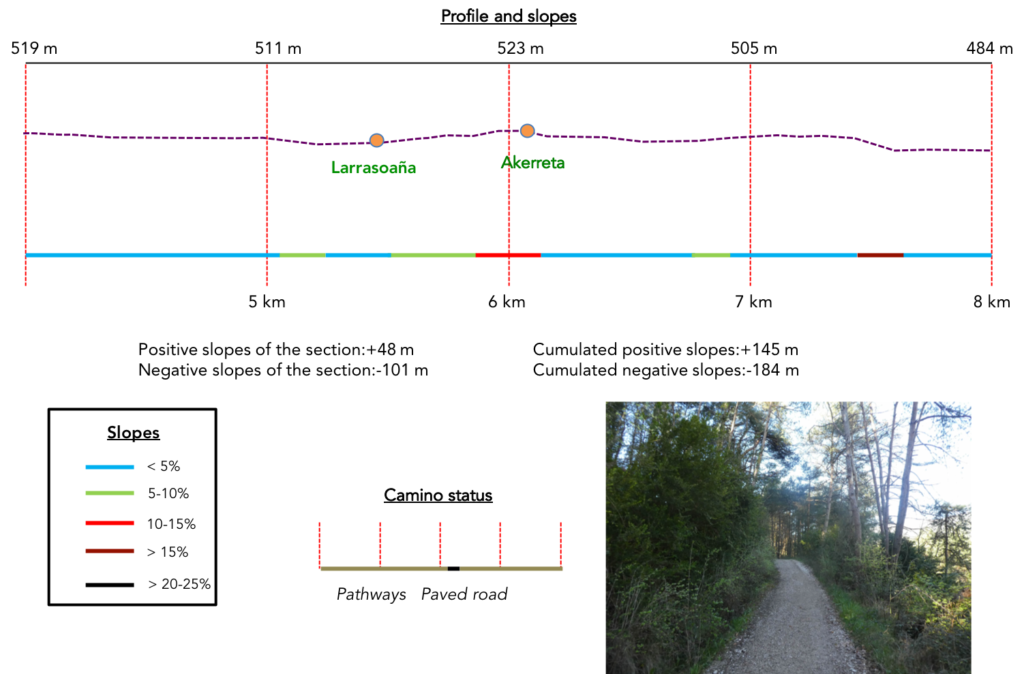

Section 2: On the heights of the Arga River.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty, except for a very steep section, but paved, down to the river.

| Further afield, the pathway crosses an undergrowth dominated by oaks and heads towards a large farm. |

|

|

| Here, you are assured that you are in the Basque country. And that’s true. Navarre together with the three historical territories of the autonomous community of the Basque Country (San Sebastian, Vitoria and Bilbao) form the Basque country. Shortly after, the dirt road crosses a small road. |

|

|

| The pathway then runs a little in the meadows where beautiful cows graze here, which look a bit like the French Aubrac. But they have a thinner snout under their beautiful horns. They are Betizu, meat cows, which are said to have a fierce appearance and are often on the alert. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway returns to the thick undergrowth, where bushes, small alders, dogwoods, clematis, holly and stunted maples emerge. It runs along the undergrowth just above the river. |

|

|

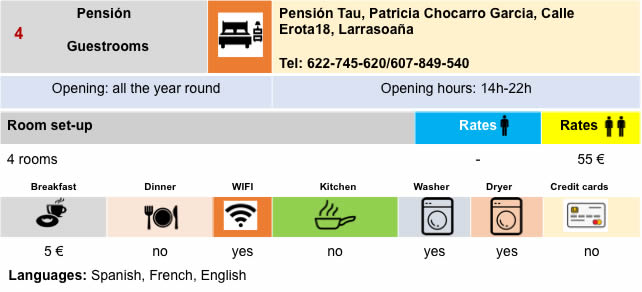

| At the exit of the wood, the pathway runs above the village of Larrasoaña, where a medieval stone bridge is thrown over the Arga River. Many pilgrims, who did not stop at Zubiri, spend the night here. The village had two hospitals for pilgrims in the XIIth century. Nothing remains there. |

|

|

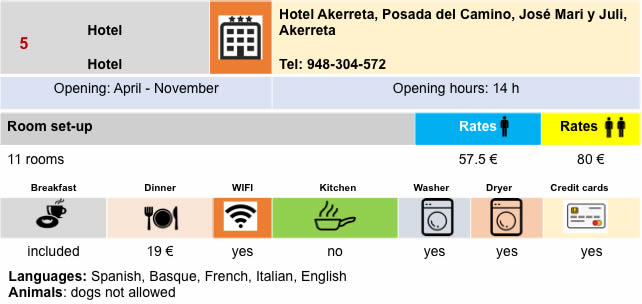

| Shortly after, a road climbs towards Akerreta. |

|

|

| If the slope is not very tough at the beginning, it increases seriously as you approach the village. |

|

|

| The village is an open museum with its beautiful stone houses, with their openings framed in cut stone. The parish church of the Transfiguration is of medieval origin, of which the robust stone tower remains. But its current appearance, baroque, dates from the XVIIth century. Even if the village hosted the filming of The Way, no American (or very few) will climb there to see the church. It is 50 meters above the track. Americans, on the whole, are not very interested in culture. But, they believe that the Camino francés is their way. So, they prefer to spend their time trumpeting aloud, so that all pilgrims can enjoy it, the misdeeds of Spanish cuisine, poor in hamburgers. Fortunately, there are many exceptions. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway undulates a little between meadows and undergrowth, where alders, maples, brambles and dogwoods abound. Here, the tall beeches have almost disappeared and only the pines and oaks remain. |

|

|

| Further ahead, alternating on a pathway smooth as a penny or covered with stones, the Camino approaches a denser forest, above the river. |

|

|

| It sometimes hesitates a little before reaching the undergrowth. |

|

|

| The forest is again splendid here, in the boxwoods, in the shade of robust oaks and august pines, which give you a little holiday atmosphere. |

|

|

| So now, organizers propose to you, so that you don’t spend the day daydreaming with your head in the air, a paved pathway that descends very steeply towards the Arga River. “These damn slabs again” will say your Italian from the day before passing by here. On the other hand, our Korean grandmother, who is moving slowly on the track, will undoubtedly find a little more comfort there. |

|

|

Here, the Arga River, most often peaceful, fragile, is not devoid of spectacular mood swings. It bubbles like a fiery torrent.

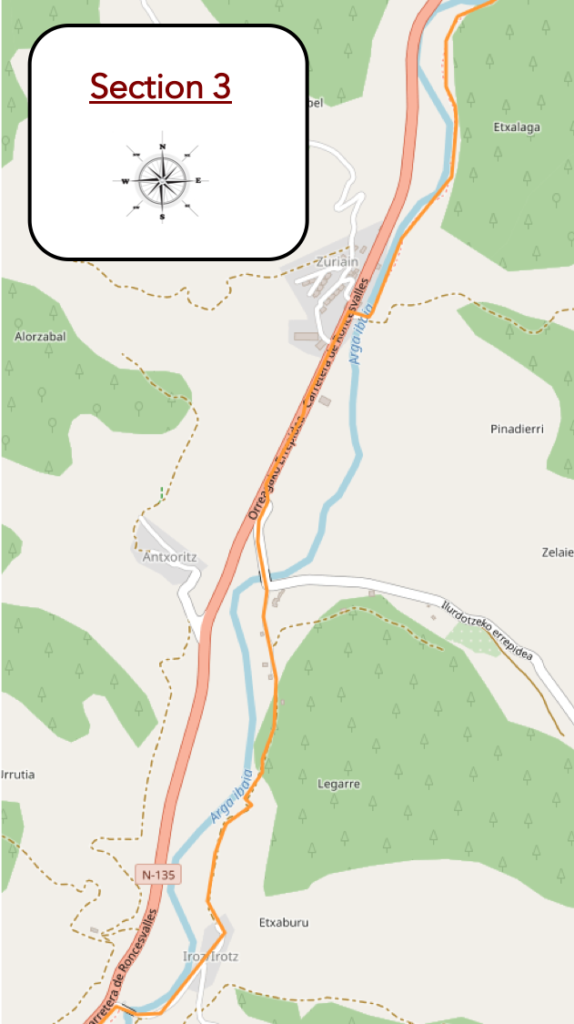

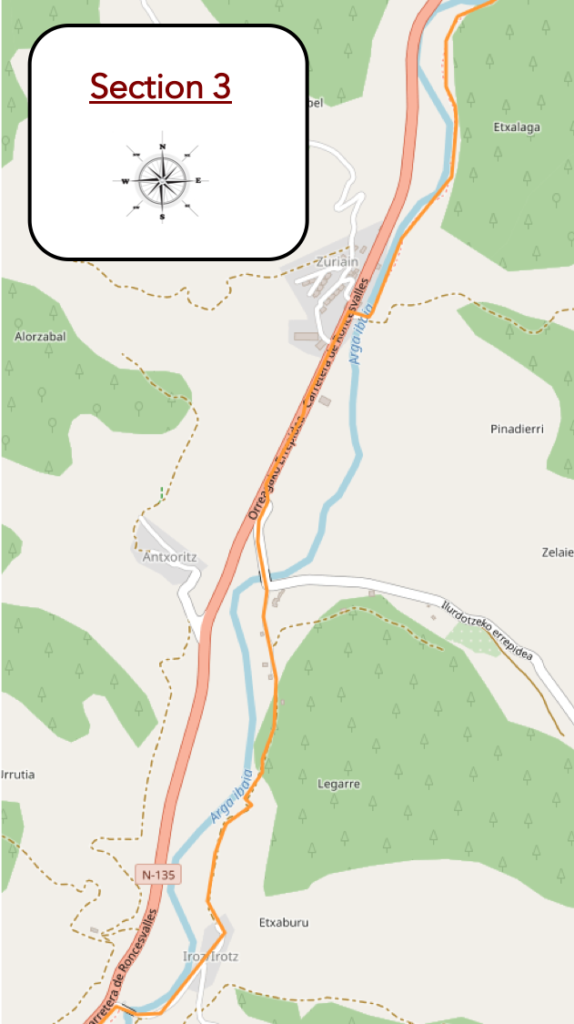

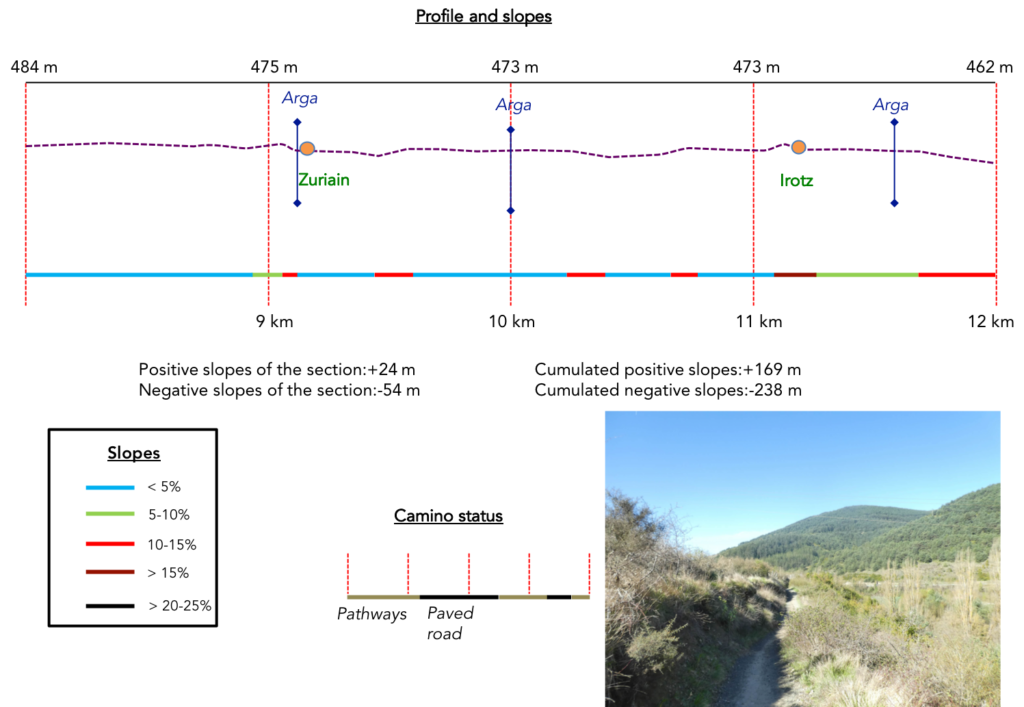

Section 3: A great dialogue with the Arga River.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway then follows the river bank. Ivy and moss often line the trunks of beeches and especially oaks. |

|

|

| Here, the light plays with the tall alders and maples that dip their feet in the river. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway plays a little with the river, moving away from it to better return to it. |

|

|

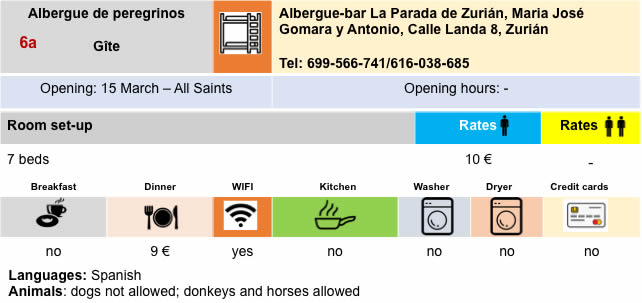

Further on, behind a small hill, you can see the village of Zuriain nestled a little above the tumultuous river.

| Shortly after, the pathway crosses the river and faces an inn. |

|

|

There is always a line in this kind of establishment. The pilgrims take advantage to have a snack. Some pilgrims do not have lunch in the “albergue” in the morning and do so on the way. Others may stop by to have one of these authentic masterpieces that adorn the terrace delivered to their homes. In Spain, it is the bull or the pilgrim the object of desire, as in Italy, Michelangelo’s David, which can be planted at little cost in his garden.

| At the exit of the village, here is a passage that pilgrims love: walking on the national road. In Spain, you can most of the time walk on the side of the road, here there is none. |

|

|

| A little further on, the Camino branches off onto a smaller road… |

|

|

| … to cross the Arga River again, which, in the meantime, has fallen asleep. |

|

|

| On the pathway that heads again towards the undergrowth, climbing Is available on a vertical wall that conceals a kind of fortified house. |

|

|

| Further on, a narrow pathway winds its way through a kind of moor where boxwood and juniper thrive. |

|

|

| The Arga valley is not wide. On the right runs the national road. |

|

|

| After a slightly steeper passage, the pathway arrives at the hamlet of Irotz. In the shade, an Asian pilgrim taps on his phone. Even busy, it will reward you with regulatory “Buen camino”. It would be a good thing to do without a few hours or better a few days of this instrument to flood the networks that we will call “associative”? In Spain, communication is good. The network is present almost everywhere, not like in France. So, phone aficionados are having a blast. |

|

|

| Here, in the past, there was also a hospital for pilgrims. The Camino crosses the village, passes near the XVIth century San Pedro church, closed as often. According to the philosophy of the “Credencial” it is better to have your passport stamped in churches. But no one is bound to the impossible. So, the aficionados of the phone give themselves to their pleasure and addiction |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway slopes down beyond hamlet… |

|

|

| …to return to the other side of the river, where there is a large beach. |

|

|

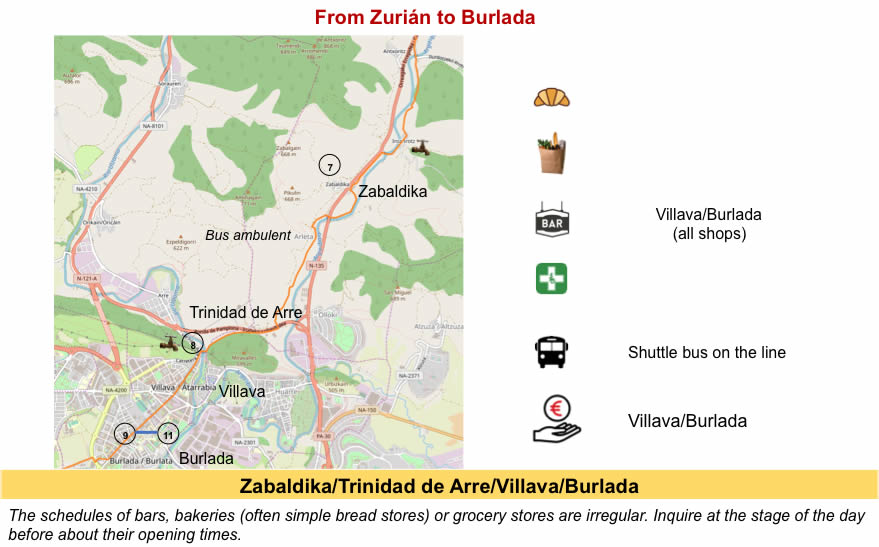

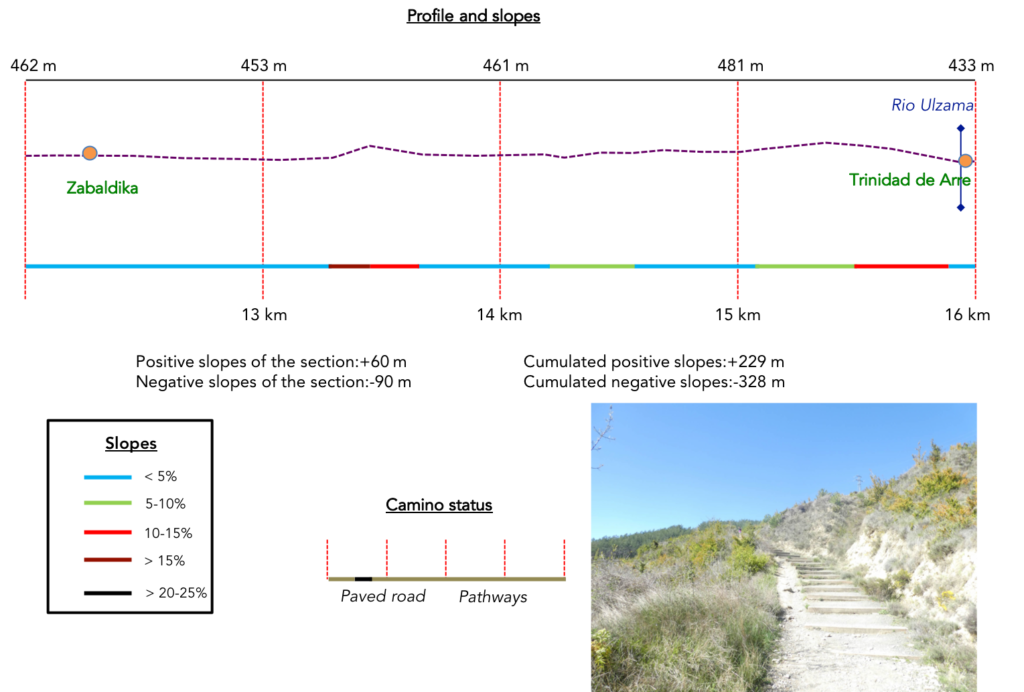

Section 4: Ripples over the Arga plain.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without great difficulty, with however a severe but brief climb, to almost 20%, in the scrub near the river. The descent to Trinidad de Arre is no problem.

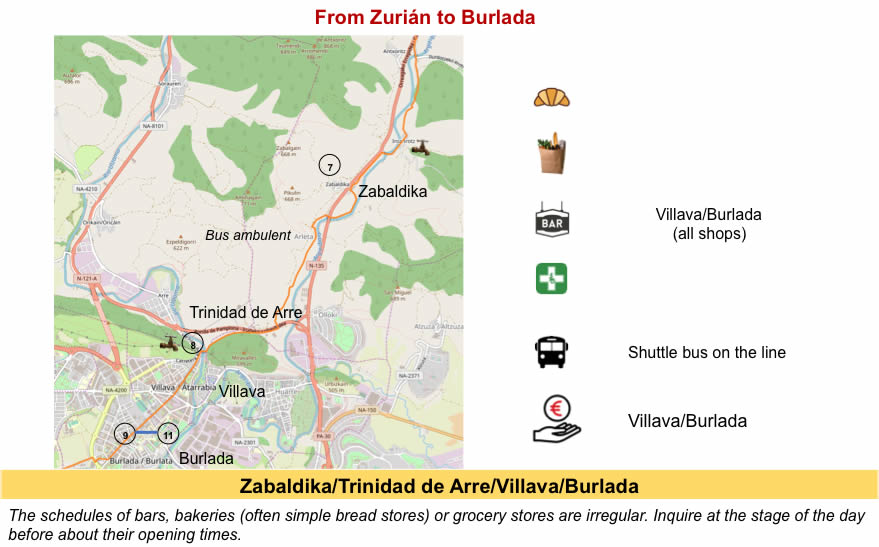

| Beyond the bridge, there are two ways to continue, on the cycle track or on the narrow pathway that runs on the sand in the moor, the signposted track. The two tracks meet beyond Zabaldika. |

|

|

| On the small pathway, the way is narrow in the bushes of the moor. |

|

|

| Further up, you’ll cross the village, or at least its lower part. |

|

|

| High above the village stands the Church of San Esteban, an old church from the XIIth century, remodeled over time. The course does not pass there. |

|

|

| A stony pathway joins the cycle track on the way down from the village. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino follows the river again. Here, these are the first real cultivated fields that you’ll see since entering Spain. You are relatively low, less than 500 meters above sea level and the wheat has already sprung up, which will not be the case further in the endless wheat silo of the Meseta. |

|

|

| Quickly, the pathway passes on the other side of the national road… |

|

|

| …and here there is just a real climb for your pleasure. |

|

|

| On a bare hill, the pathway climbs through boxwood and short grass. It’s short, but tough, almost 20% incline. It is always on these sections that pilgrims dawdle, stopping on the way to catch their breath or take pictures, whistling to give the illusion of ease. From up there, you can better measure the extent of the Arga valley. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway descends towards the plain. Safety gates were put on a track that is not dangerous at all. They do not joke with the safety of pilgrims in Spain. |

|

|

| The pathway soon arrives in the hamlet of Arleta, with its massive and somewhat dilapidated houses. Here, you’ll see for the first time lime trees and almond trees on the way. |

|

|

| Here, a colorful Spaniard, who has traveled around the world, especially in America, will tell you about his life with passion. He thinks of learning Korean to increase his turnover. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway nods at the foot of the plain, sometimes in the meadows… |

|

|

| …sometimes in spaces that look more like steppes. You sometimes encounter maples, but especially see black poplars, the king trees of northern Spain. |

|

|

| On the other side of the valley are the settlements of Olloki, apparently a large suburb of Pamplona. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway heads to a forest of pinis cembra… |

|

|

| …before going through a tunnel on the other side of the national road. |

|

|

| A wide dirt road then runs, in the direction of a pine cembra forest, above the PA-32, the road that leads to Pamplona from the national road… |

|

|

| …then slopes down to the edge of the wood on the other side of the hill on the tarmac. |

|

|

| Further down, hardwoods take over from conifers. |

|

|

| This magnificent stone bridge, with its six arches, overlooks a charming and romantic site, where the water once again bubbles and cascades. |

|

|

| At the end of the bridge stands the Church of La Trinidad, which dates back to the XIIIth century. The church is still part today, as in the Middle Ages, of a convent run by brothers of Mary, who still run the pilgrims’ inn. |

|

|

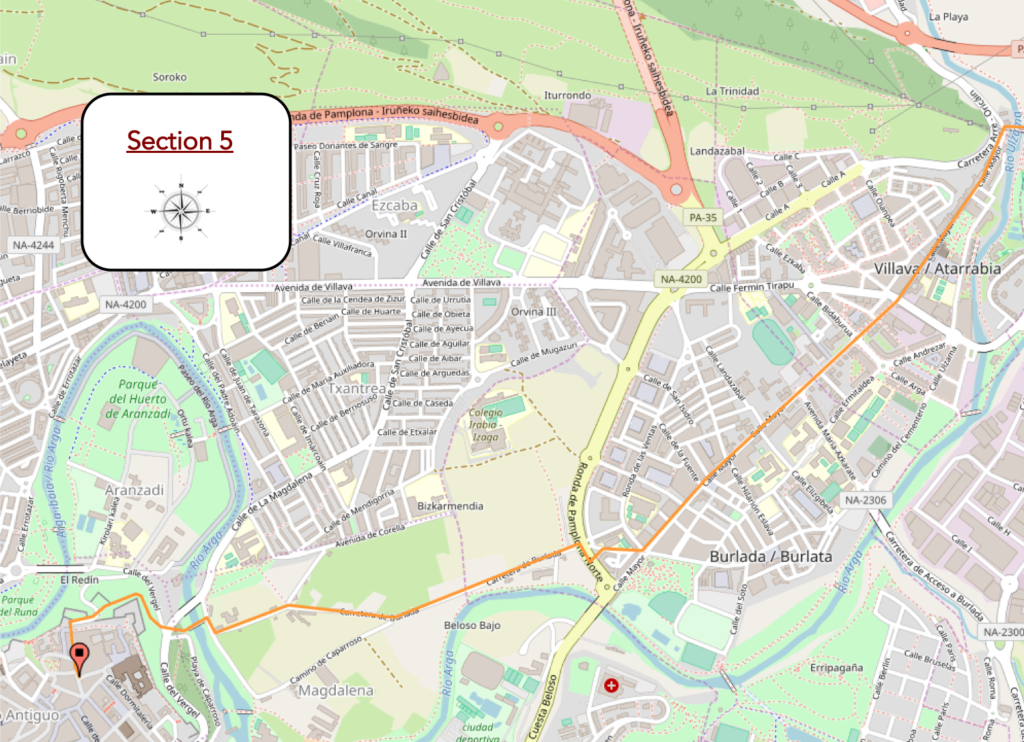

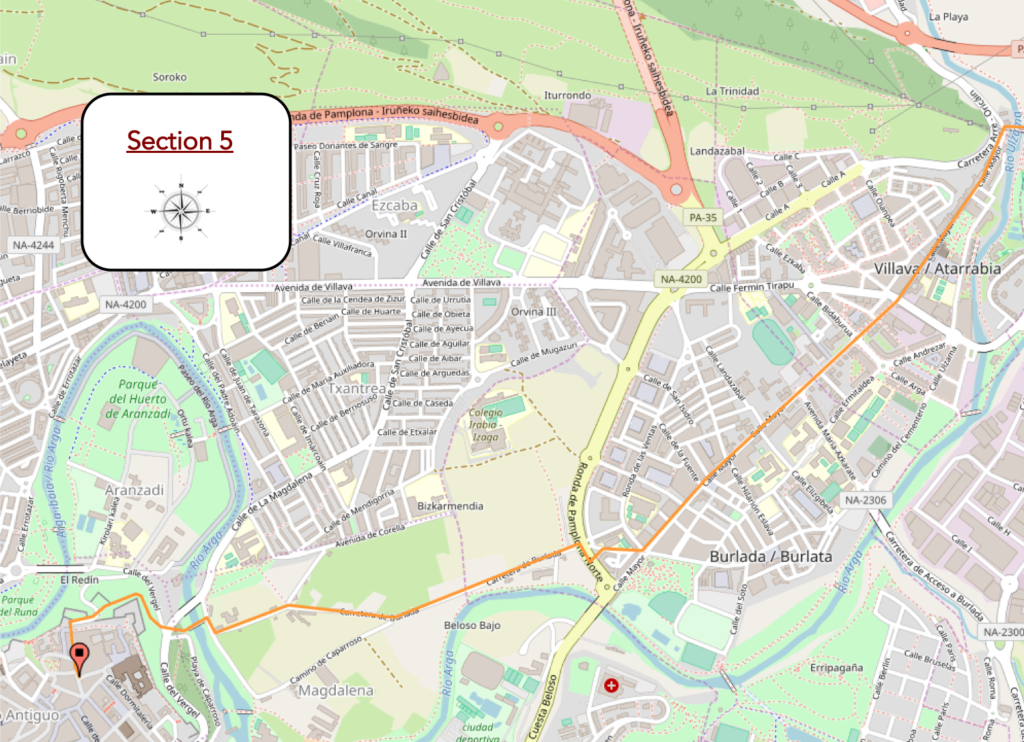

Section 5: In town before the fortress of Pamplona on the hill.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| From here, the Camino takes on an almost exclusively urban aspect, in the greater suburbs of Pamplona. It immediately runs through the neighboring town of Villava/Atarrabia. It is the birthplace of the great cyclist Miguel Indurain, multiple winner of the Tour de France, to whom the city has given a place. In Spain, the main street is almost always the “Calle Mayor” and the main square, often the “Plaza Mayor”. |

|

|

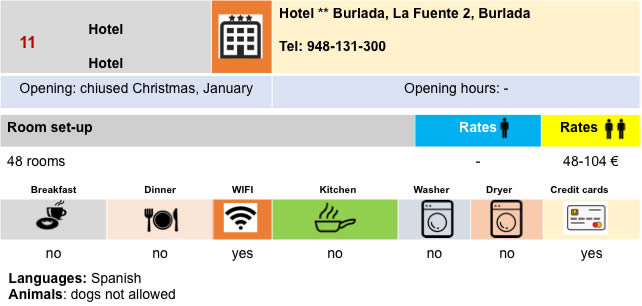

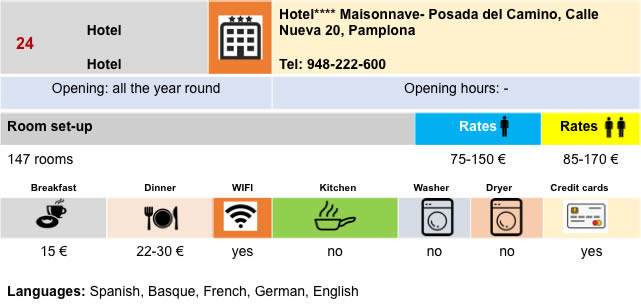

| Then, on the long straight line under the horse chestnut trees, the Camino passes without transition from Villava to Burlada/Burlata. These two cities still have more than 30,000 inhabitants. |

|

|

| In Spanish cities, there is little chance of getting lost. Signs are everywhere, be it paint or scallop shells, most often stylized. But if by distraction you do not see them, you just have to follow the pilgrims in front of you who will undoubtedly show you the way to follow. |

|

|

| Towards the end of the city, a curious XXth century palace stands near large gardens. |

|

|

| Further on, the Camino leaves the road for a sidewalk. A bit of a return to greenery, in a way. |

|

|

| It will run for some time in an alley under the modest black poplars… |

|

|

| …then along a high wall, at the end of which you can see the bell towers of Pamplona on the hill in the distance. |

|

|

| The Camino then quickly approaches the city, running through the suburbs of the lower town. |

|

|

| Shortly after, you are in front of the beautiful Magdalena bridge, undoubtedly of Roman origin, but deeply remodeled over the centuries. Together with the San Pedro bridge, it is the oldest bridge over the Arga River, although the last transformations date back to 1960. This beautiful and very popular bridge, with its promenade along the river, is a historical monument. But, it is often the pilgrims who haunt the place. |

|

|

| Here flows the Arga River, the great river, which has become calm and majestic. |

|

|

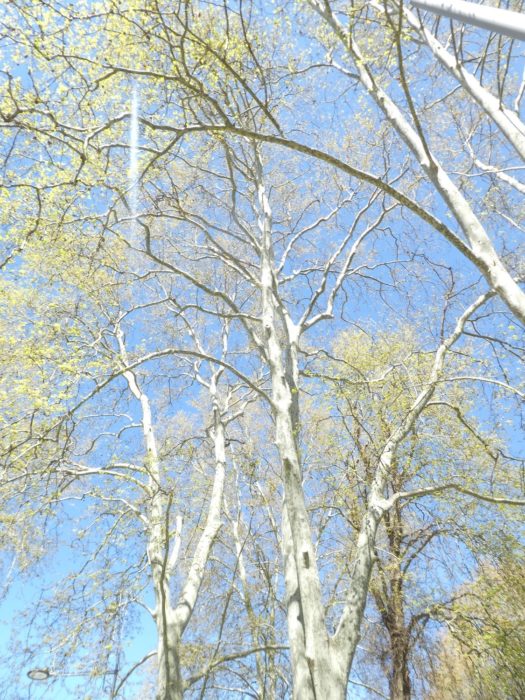

| Here, near a stone calvary, mighty horse chestnut trees soar skyward along the riverside promenade. |

|

|

| The Camino then skirts the enormous walls to climb towards the old town. The citadel is huge. To say the least, it is the most imposing in Spain. Under King Philip II, its construction began in the XVIth century, designed by the Italians to defend the city from potential invasions. Here you see only part of this fearsome construction, which is part of a pentagonal star-shaped fort connected to the rest of the city walls. |

|

|

|

|

| It passes two monumental gates to enter the city center. There are few cities in Europe that exude such great military power. Despite the drawbridge which gives it a medieval appearance, the Portal de Francia only dates from the XVIIth century. After passing through this outer gate, the route reaches a second gate, the Portal Zumalacarregui which leads, through the fortress, into Calle del Carmen. This gate, in the original wall of the walled city, was previously called Puerta del Abrevador, in the XIVth century, later Puerta de Francia, in the XVIth century. The shield bears the coat of arms of Carlos I of Castile and Carlos V of the Holy Roman Empire. |

|

|

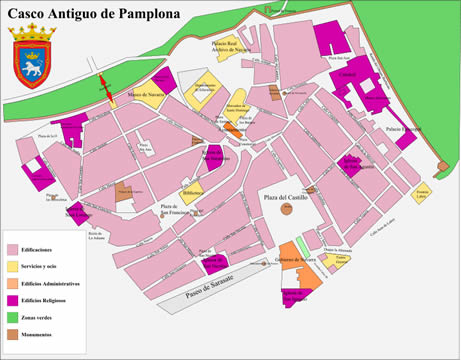

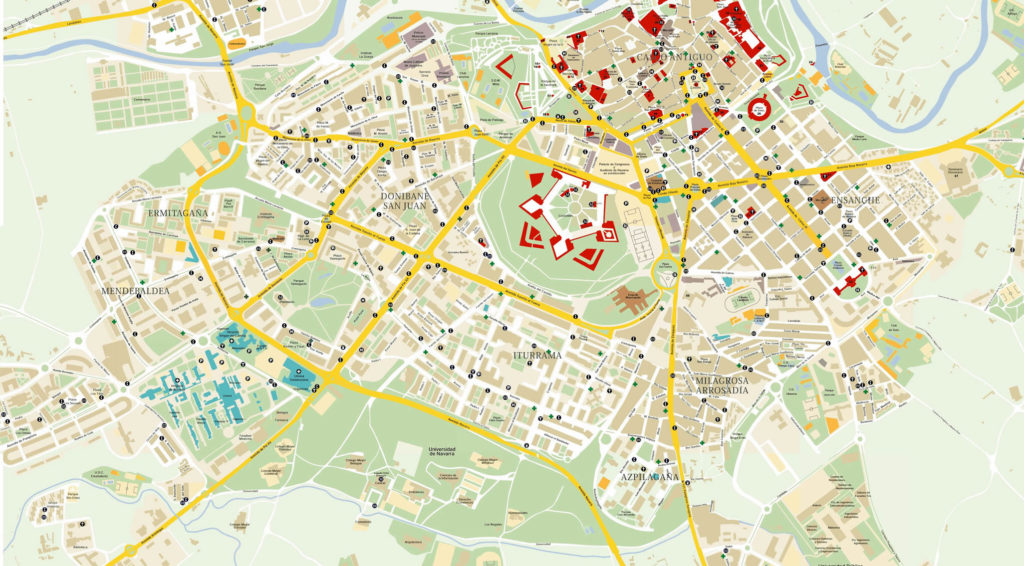

Section 6 : A short tour in Pamplona old town.

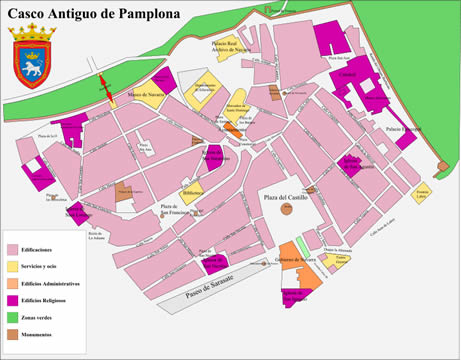

Pamplona ( Iruña in Basque) is a vibrant university town that retains its strong historical ties to the Camino de Santiago. The old town includes the Casco Antiguo and the citadel (Ciudadella), which the Camino will skirt in part, leaving the town. Pamplona is not a small city with its 200,000 inhabitants. It is the largest city crossed by the Camino de Santiago, but it is only in rank 29 of the hierarchy of Spanish cities.

http://www.orangesmile.com/guia-turistica/pamplona/mapas-detallados.htm

It is especially in the Casco Antiguo that the monuments are stored.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Casco_Viejo_de_Pamplona.svg

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Casco_Viejo_de_Pamplona.svg

| Through the often-narrow streets, the Camino quickly reaches the center, near the Plaza de los Burgos and the town hall (Ayuntamiento). It’s Saturday, at 1 o’clock in the afternoon. The streets are dense, just before the siesta, when Spain then empties and stops breathing. |

|

|

| However, by taking the streets that head towards the cathedral, there are sometimes a little less people. |

|

|

| Saint Mary’s Cathedral then appears at the end of Calle Curia. There is not much clearance on the Cathédral Plaza. It is a church-museum, with a rather complicated history. Of the primitive Romanesque church of the XIth-XIIth century, nothing remains except for a few capitals and portals exhibited in the museum. At the end of the XIIth century, a Gothic cloister was added, which has come down to us. At the end of the XIVth century, the Romanesque nave collapsed, so a new Gothic cathedral was rebuilt here, keeping the cloister. In the XVIIth century, a few more baroque and neo-classical additions were made. |

|

|

The nave is quite bright and uncluttered with its large arcades and windows.

| The same cannot be said of the golds and gildings that the Spaniards love. |

|

|

There is also a very beautiful black Madonna in the church. This Smiling Virgin is called the French Virgin.

Here rests the alabaster tomb of King Carles III, the founder of the cathedral, which he had erected for himself and his wife.

| In an elegant and modernly designed transition space, you then pass from the church to the cloister. |

|

|

| The visit continues with a visit to the pleasant and educational diocesan museum. It really changes many dusty museums, where you are bored to death. But, this trend fortunately is becoming more and more visible in the world. |

|

|

| The visit ends with the cloister, which was being renovated during our visit to Pamplona. |

|

|

| Returning from the cathedral towards the center you will arrive at the Plaza del Castillo, the main square of the city, the equivalent of the Plaza Mayor of the major cities of Spain. |

|

|

| Among the Spaniards of the XIIth century, the fueros represented the law, the status, the privileges of a state, a province or a city. It comes from the Latin forum, meaning public square or public assembly. This status is therefore a precursor of what the Spaniards love, namely regional autonomy. Here in Pamplona, the fueros were behind the creation of the city. A monument is dedicated to them, a little away from the Plaza del Castillo.

A little further, you can jump to the arenas, dating from 1922, with 19,000 seats. Of course, it’s a little more hectic during the San Fermín fiestas, the Sanfermines, celebrated every year from July 6 to 14, in honor of the patron saint. It’s as crowded as Oktoberfest in Munich, with over 3 million people during the week. Bullfights are the highlight of this famous celebration, immortalized by Hemingway in his novel The Sun Also Rises. The races take place every morning. The bulls are released at the corral of San Domingo near the Arga River and the music begins. Thousands of people run every day, sometimes 3,000 a day, big adrenaline junkies, to avoid the six huge bulls, on a course signposted by the winding streets that lead to the arena. Paradoxically, there are few deaths in this perilous exercise, only about fifteen people since 1911, the last of which in 2009. Once arrived at the arenas, the bulls are parked for the evening bullfight. |

|

|

| You will probably run the closed church of San Saturnio, one of the first quarters at the origin of the city. |

|

|

| It is also a pleasure to stroll near the small squares of San Francisco or San Nicolas or near the town hall. |

|

|

| In this fascinating city, you can also stroll through almost deserted streets at siesta time. |

|

|

| But, when the siesta is over and the shops reopen again, when the city bustles at tapas time, you can stroll at leisure in the picturesque alleys, where the bars and ice cream parlors are busy. The city seems to be in a permanent state of celebration. |

|

|

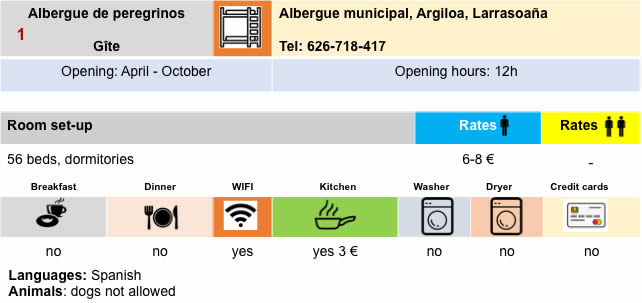

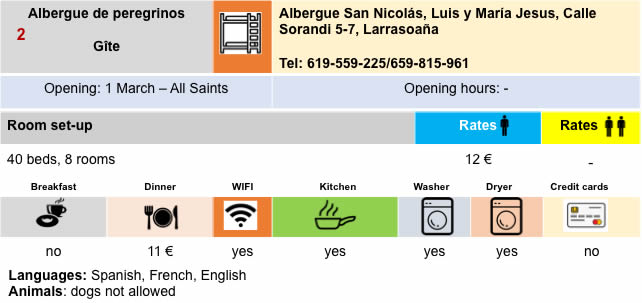

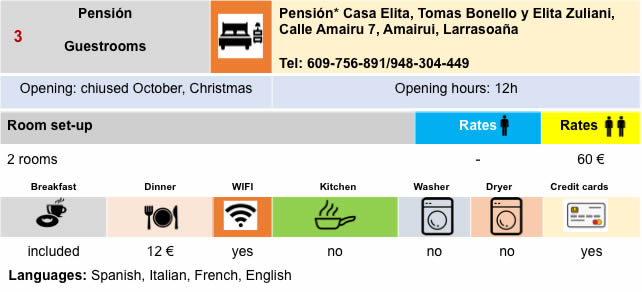

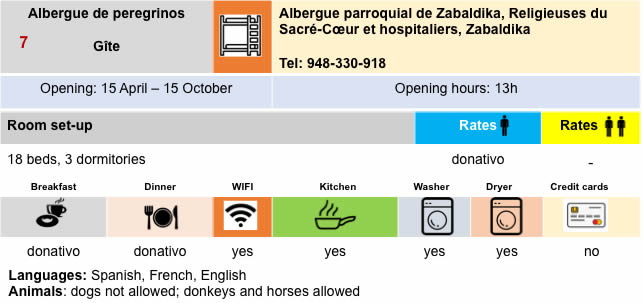

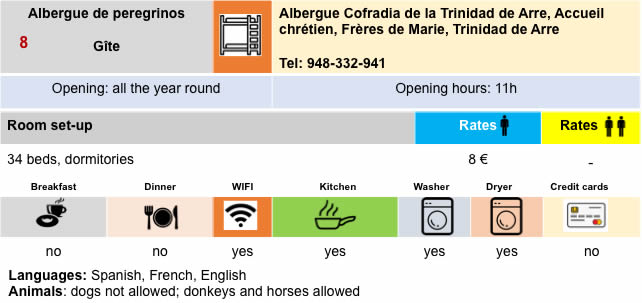

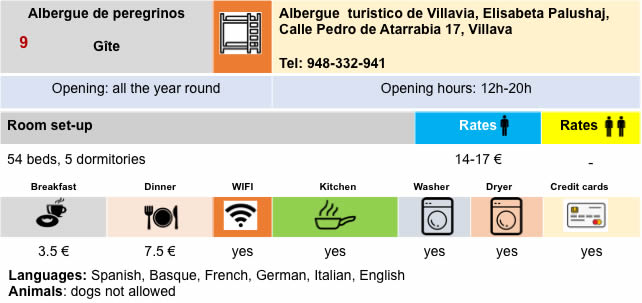

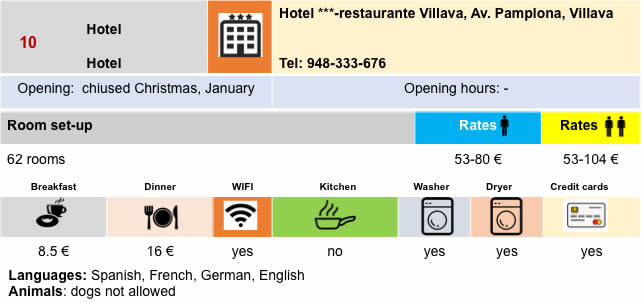

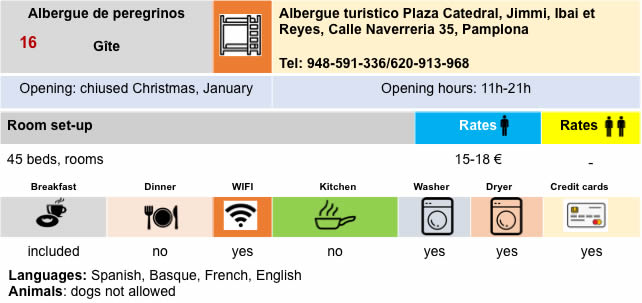

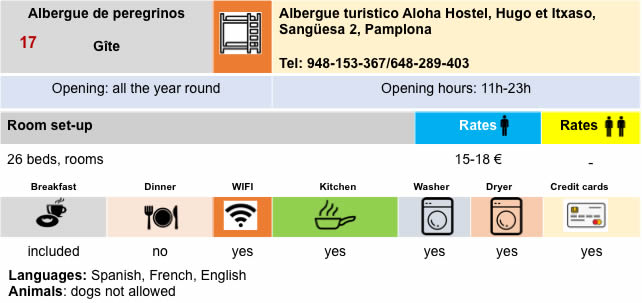

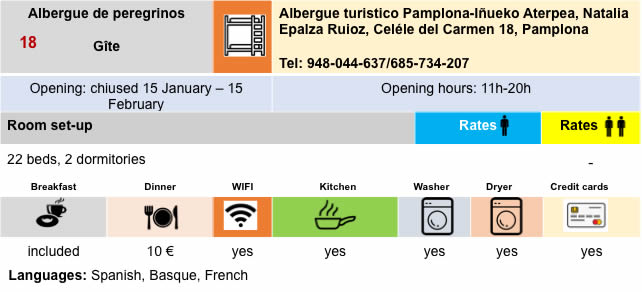

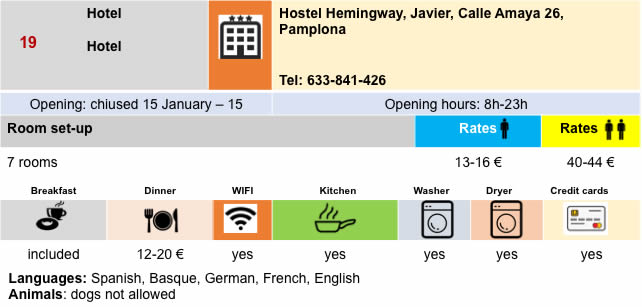

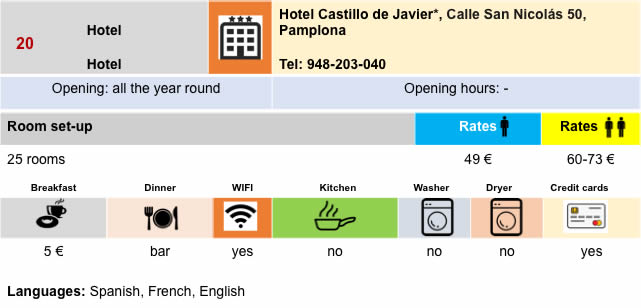

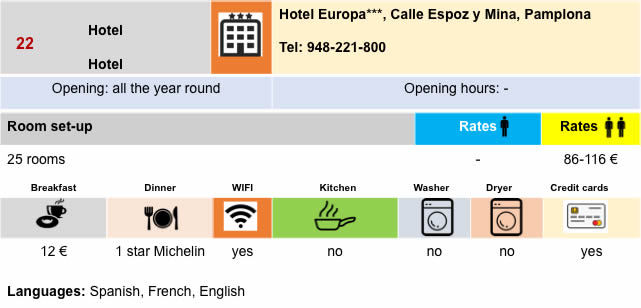

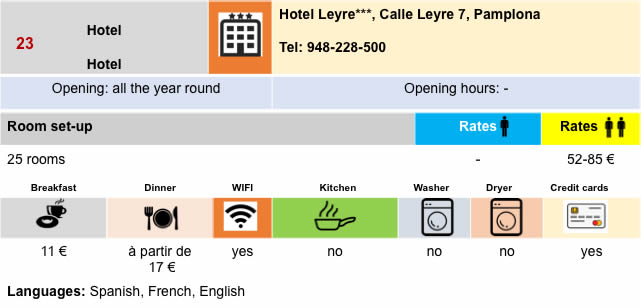

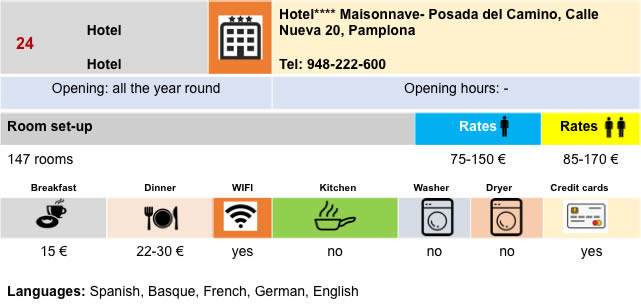

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 4: From Pamplona to Puente La Reina |

|

|

Back to menu |

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Casco_Viejo_de_Pamplona.svg

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Casco_Viejo_de_Pamplona.svg