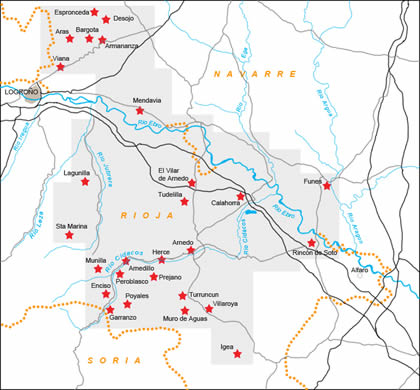

From Navarre to Rioja

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

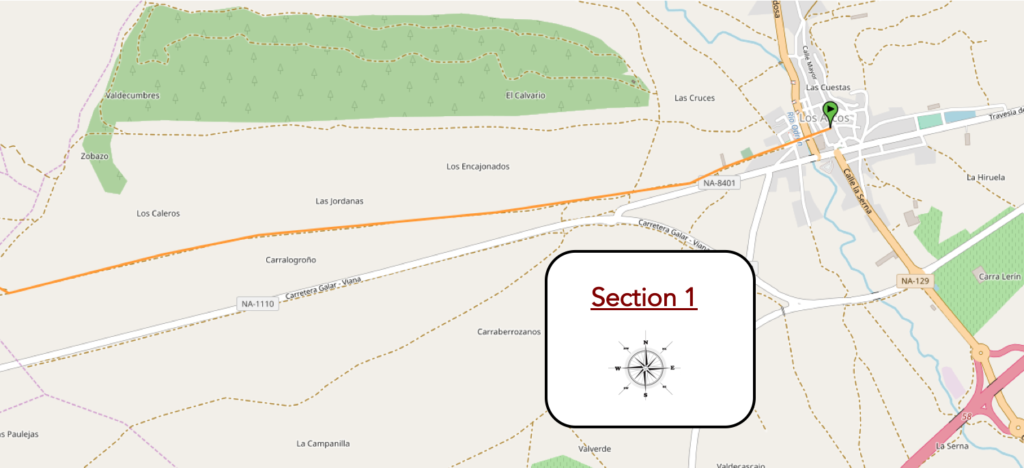

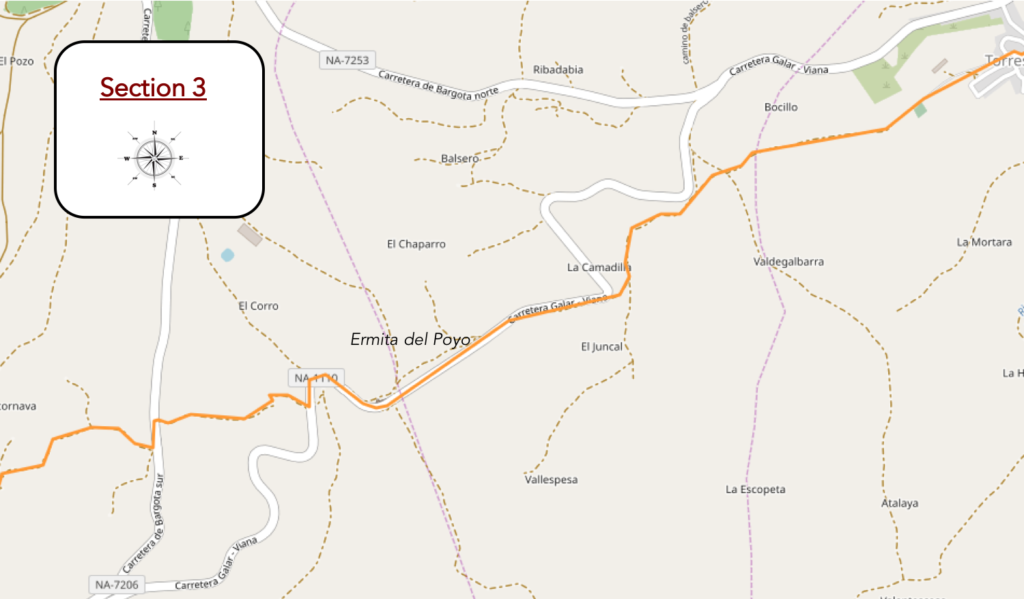

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-los-arcos-a-logrono-par-le-camino-frances-33702244

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

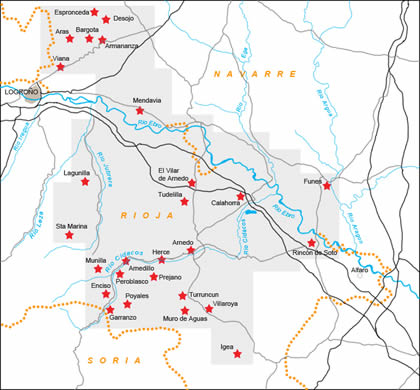

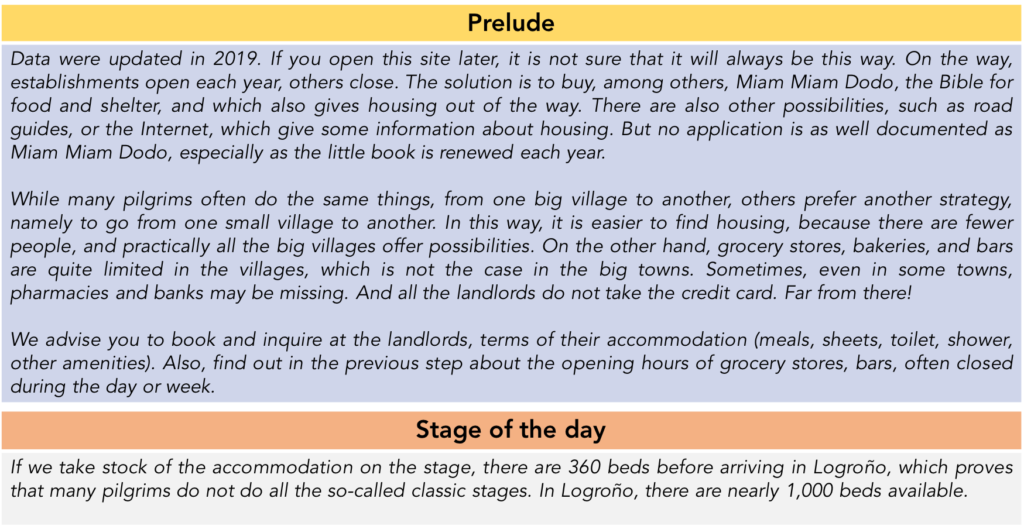

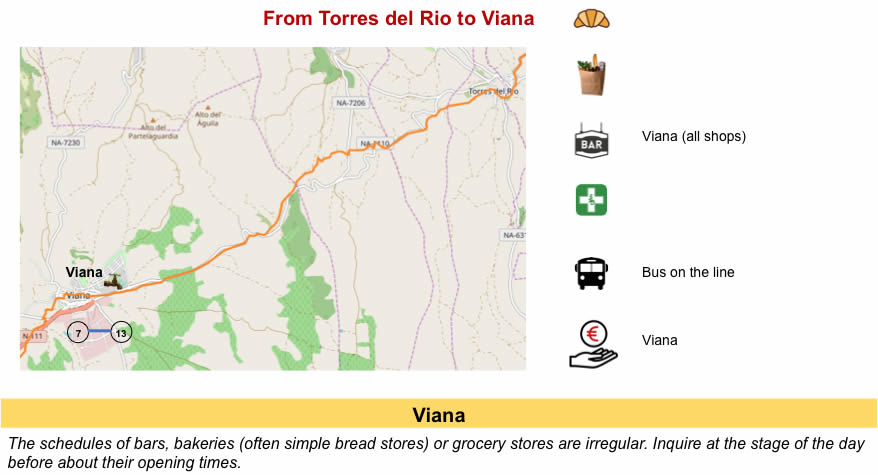

Today, the route heads to Rioja. These are the last jumps of Navarre, sometimes on wide dirt roads crossing the Meseta, but also in small dales, where the course likes to follow the national road that leads to Logroño. No highway today, too bad! On the way, the course crosses two beautiful medieval villages, Torres del Rio and Viana. When you walk over the Camino francés, you can still understand why Europe has made this track a real way of exception. The heritage is truly of great wealth in the country, unique, almost medieval appearance, when in fact, the buildings were erected most of the time after the XVIth century. But the XVIth century is old enough, right? At the end of the route, the track leaves Navarre for Rioja.

Rioja has actually no history of its own. For centuries, the territory has been at the heart of incessant conflicts between the kingdoms of Navarre and Castile, and this since the Xth century. In the XIIth century, it became a part of Castile. It obtained a pseudo province status in the XIVth century, standing out from the big Castilian provinces of Soria and Burgos. It was not until the “Spanish democratic transition”, from 1975 to 1982, that the process, after the death of Franco, created a real democracy in Spain. The autonomy status of Rioja dates from 1982, when the region finally broke away from old Castile.

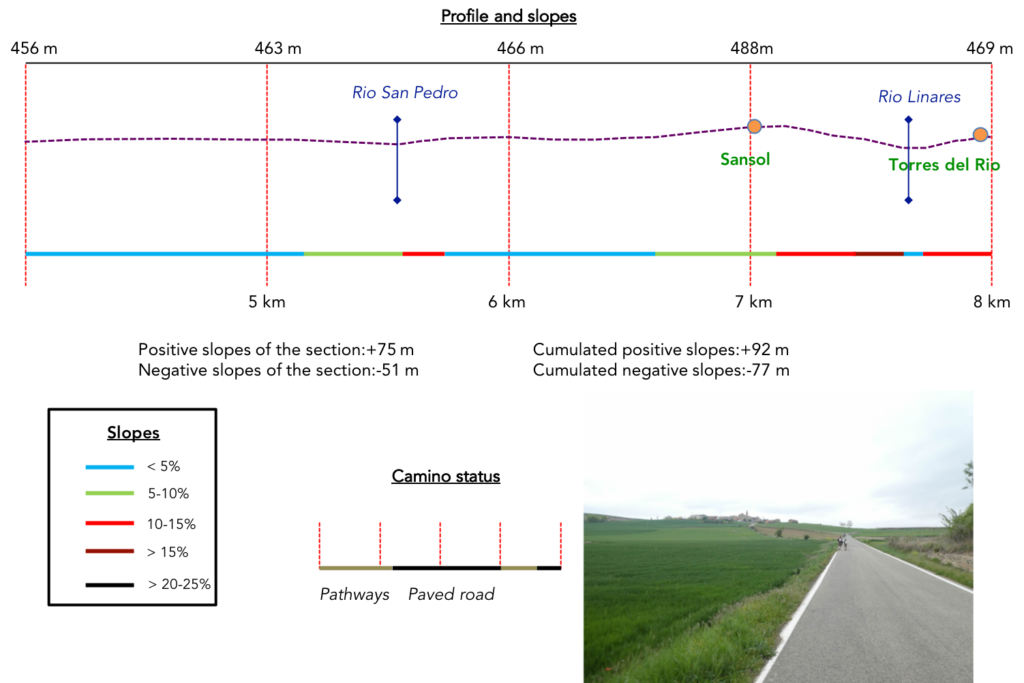

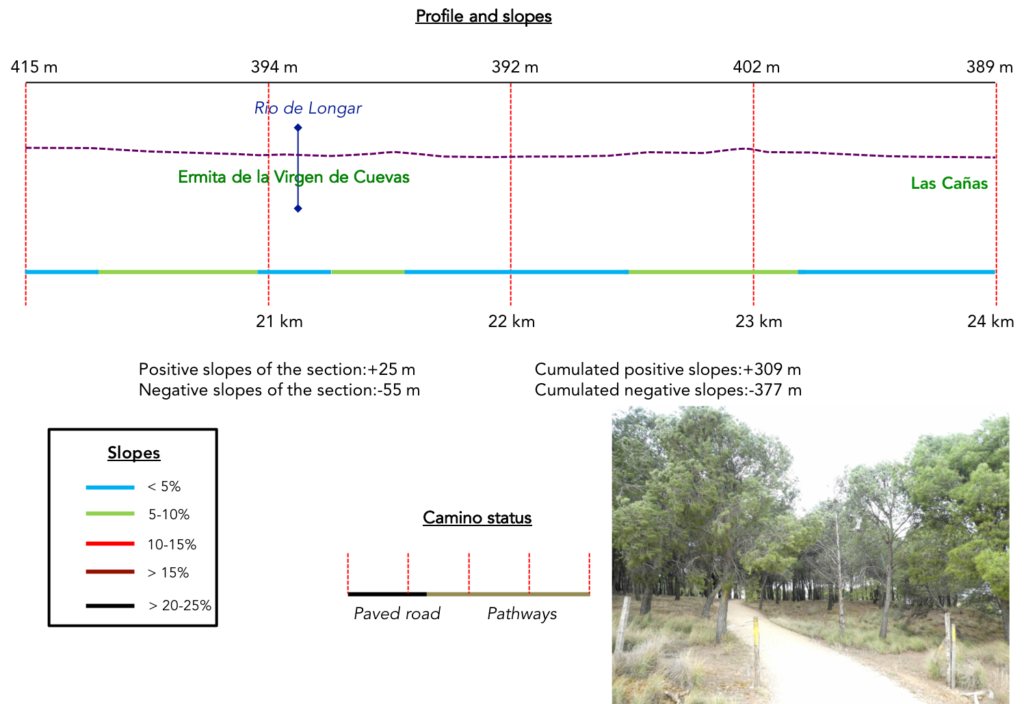

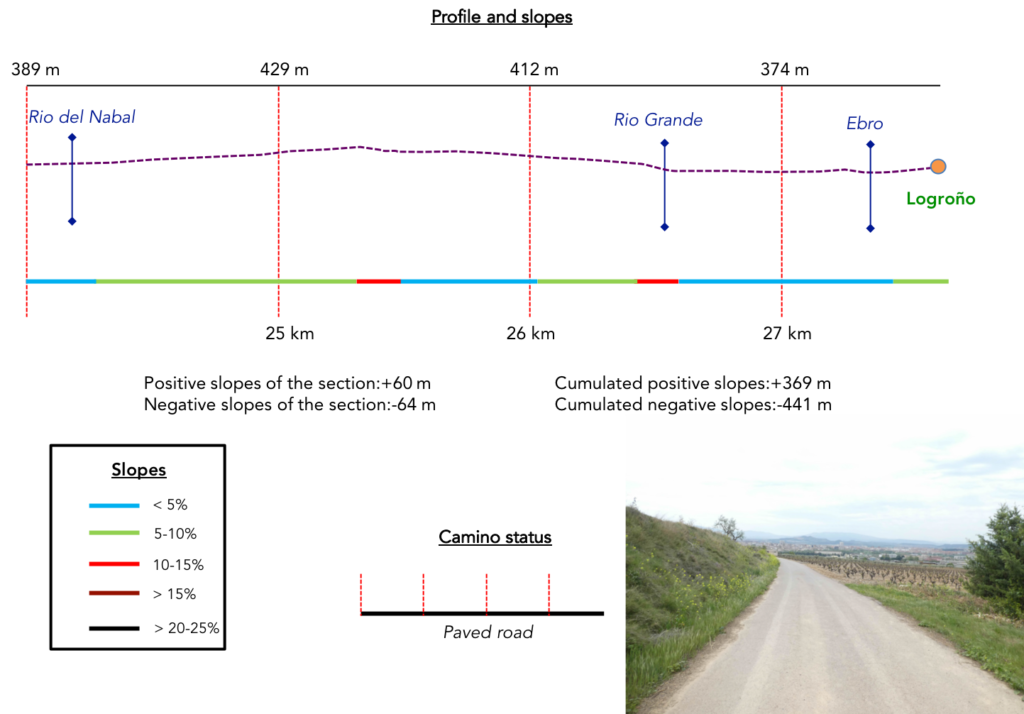

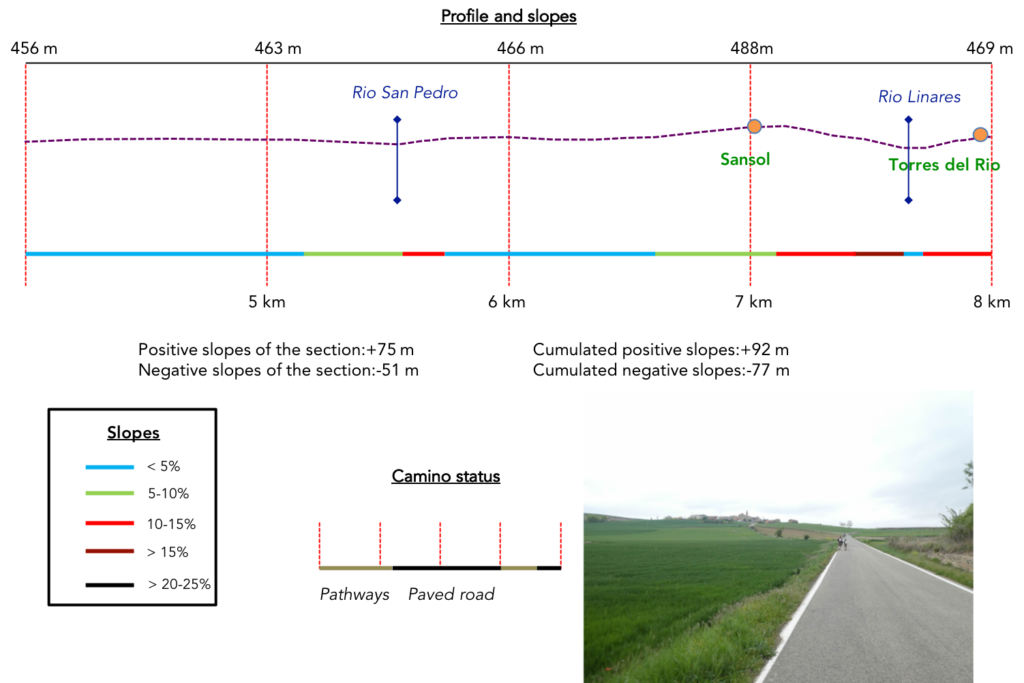

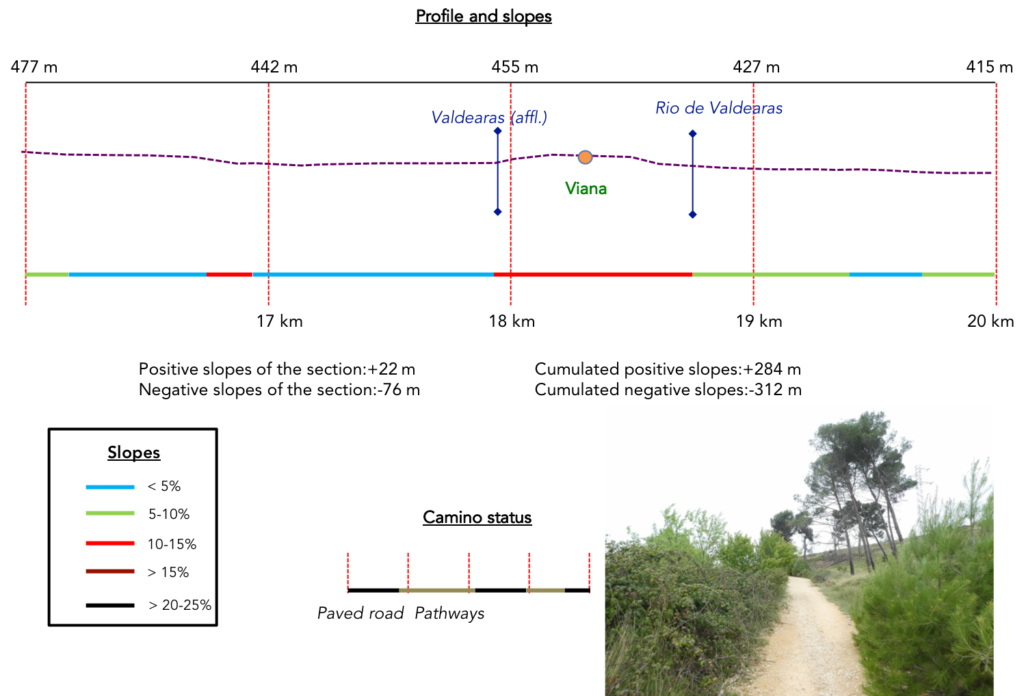

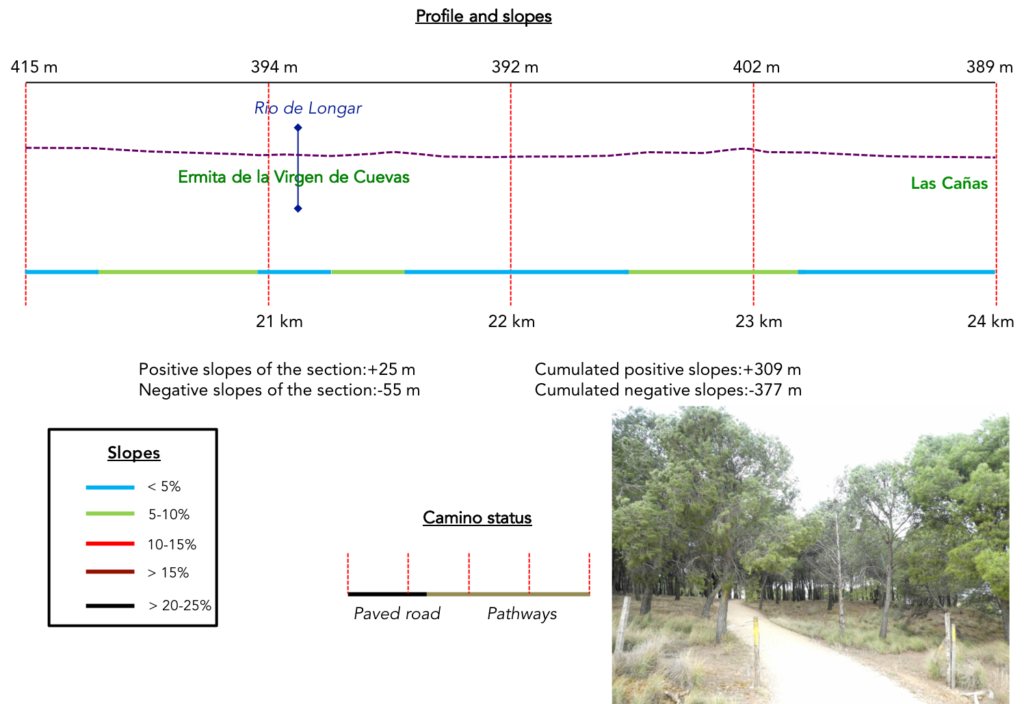

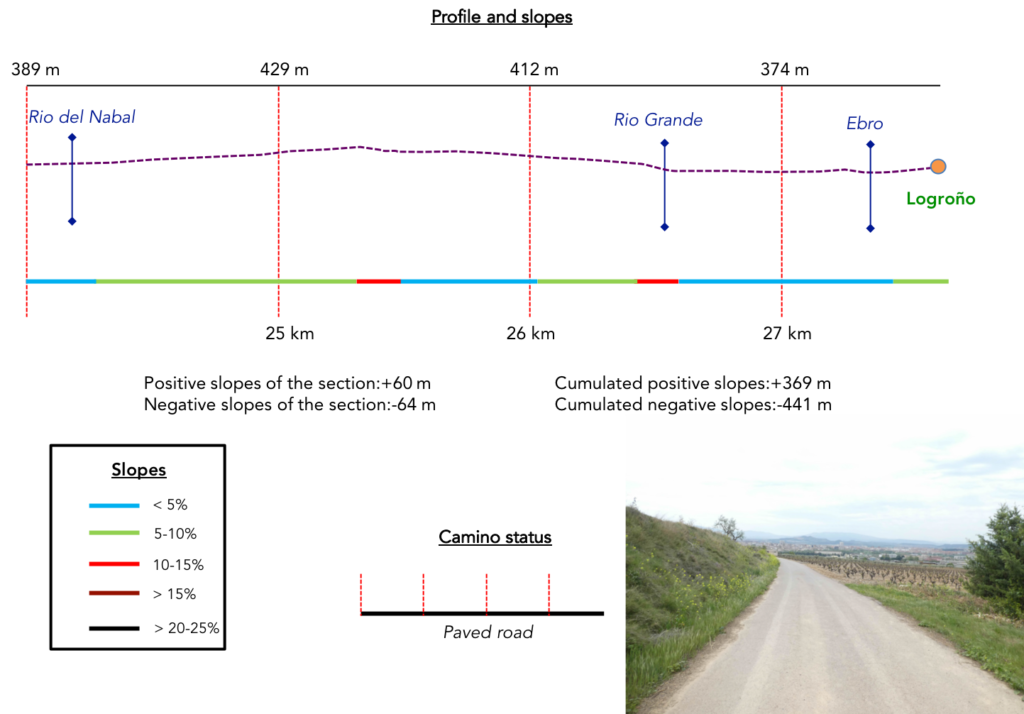

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations today (+369 meters/-411 meters) are low for a stage of nearly 28 kilometers. The Camino francés remains a low altitude course, even if you walk on a high plateau. But, do not doubt about it, there are still some nice bumps. The most tortuous passage is when the road passes near Sansol, then after when it makes efforts to avoid the national road along the small hills. But beyond Viana, it is the plain, even if the course makes still a small detour through the hills before reaching Logroño.

In this stage, there is a lot of paved road, because the approach of the city is on the tar. But, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads :

In this stage, there is a lot of paved road, because the approach of the city is on the tar. But, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads :

- Paved roads: 7.2 km

- Dirt roads: 20.4 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

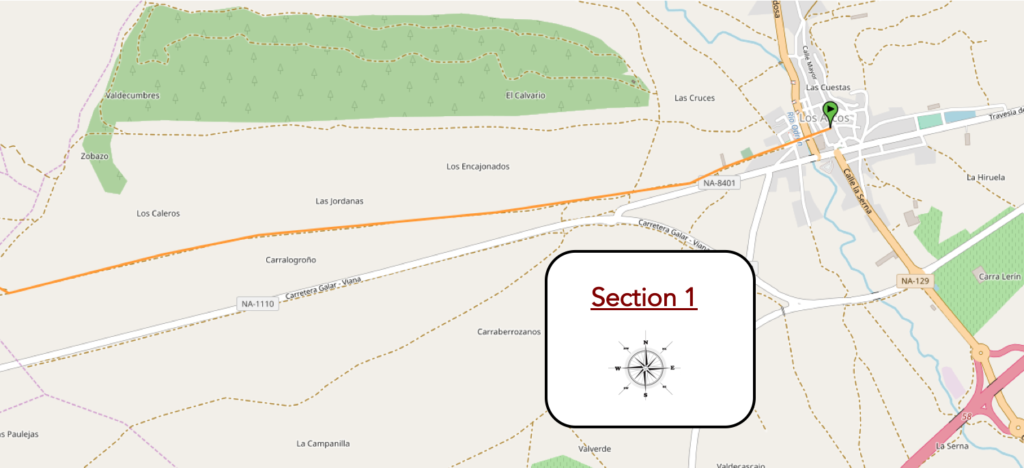

Section 1: An endless length.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem.

| The route leaves Los Arcos in the arcaded square near the Santa Maria church, through the XVIIth century gate which opens onto the exit from the old town. |

|

|

| Just behind the door flows the Río Odrón, under the black poplars |

|

|

| Depending on the year, it can be waterier, even very muddy. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the village fairly quickly, passing the large Pilgrims’ Inn and climbing the hill. |

|

|

| A wide pathway then opens near a small electrical unit and runs between the fields of cereals and the vines. |

|

|

| You’ll have to get used to it, you don’t have much choice. This is yet another taste of what you will soon find on the Camino francés. Here, it’s only 7 kilometers, almost in a straight line, to reach the village of Sansol that you can see far in front of you. |

|

|

| The eyes naturally take you to the distance. On these tracks of great solitude, everything depends on your departure time and your walking pace. You can find yourself almost alone or be inundated and swallowed up by the cohorts of pilgrims. |

|

|

| It is haunting and confusing at the same time, a universe that annoys or fascinates. |

|

|

| Further on, a small mishap in the form of the discreet Valesca stream, and in front of you the line of pilgrims lengthens. Pilgrims, for the most part, advance in this great plain without grumbling. Nobody forced them to come here. But there are always the incorrigible, who find criticism in everything. However, the village of Sansol has come a little closer in front of you. |

|

|

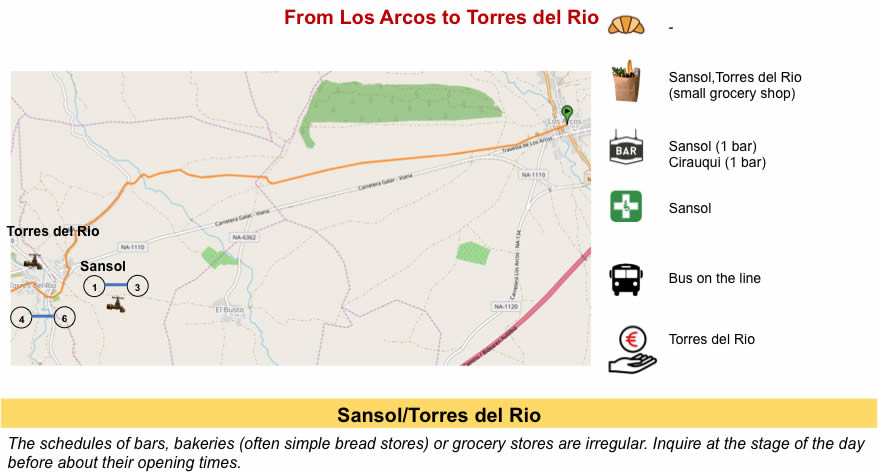

Section 2: Passing through the beautiful village of Torres del Río.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: more difficult course near Sansol, but nothing demanding.

| However, a little further the pathway, generous, begins to wiggle slightly and the landscape becomes a little more varied, mixing fields of cereals, vineyards and even olive trees. On the way, some pilgrims put their protection against the rain, yet it has not been raining for five days, even if it is always cold. |

|

|

| Here, the ground, varying between red and dirty gray, must not absorb water easily. It is felt that it must be pretty muddy here in the rain. |

|

|

| Sansol is getting closer and closer and the pathway crosses San Pedro brook, no more in water than the previous one. |

|

|

| Shortly beyond the stream, the Camino finds a small departmental road that climbs gently towards the village. As the landscape is not exciting for all, this pilgrim benefits from answering these emails while walking. There is not a minute to lose on the way. But why the hell cannot you do without this damned cell phone? |

|

|

| Here, a father walks with a child on the road which straightens a little on the village. |

|

|

| There, a pilgrim takes a picture of her friend to fix on film this unforgettable memory of Sansol’s first “albergue”. |

|

|

| Sansol is a uniform village, with its massive stone houses, some emblazoned, others resembling opulent Baroque mansions. Baroque too is the XVIIth century church. The Camino only skims the village. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves Sansol on the road and heads towards Torres del Río, also formerly called Torres de Sansol, a village dominated by the San Andrés church on the other side of the small valley. These two villages have experienced the same historical evolution as Los Arcos, having long been attached to Castile. Here you are about 20 kilometers to the end of the stage. |

|

|

| A paved pathway then steeply slopes down through the dale in the valley between the two villages. These slabs will surely still moan our Italian friend who claims that they have killed the course. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the dale, the pathway crosses the Rio Linares. The village of Torres del Río then appears, homogeneous, perched on the hill, dominated by the parish church of San Andrés, a Baroque building of the XVIth century.

Torres del Río means “Towers of the river”, in reference to Río Linares. A colony already existed in Roman times. The city, also known as Torres de Sansol, existed before the Muslim invasion. It was reconquered after the capture of Monjardín. Already in the XIIth century, it had a monastery subordinate to that of Irache. In the XIIth century Codex Calixtinus, Aymeric Picaud writes: “Near a place called Torres, on Navarrese soil, flows a river which kills the horses and the men who drink there”. This brave Aymeric did not always like Spaniards. |

|

|

| A fairly steep slope leads to the top of this magnificent village with massive, baroque and emblazoned houses for the most part. The climate must have been harsh to be able to erect these dwellings which are like stone fortresses. |

|

|

At the bend of a narrow alley then appears the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (Santo Sepulchro). It is a historical monument, based in particular on its octagonal layout, its beautiful star-shaped dome and on Muslim influences mixed with Romanesque art. Mudéjar is a style of architecture and decoration strongly influenced by Moorish taste and craftsmanship. The Moors had dominated the Iberian Peninsula since the VIIIth century. The Mudéjar style, resulting from Muslim and Christian cultures cohabiting for nearly 800 years, imposed itself as an architectural style in the XIIth century in the Iberian Peninsula. Mudéjar architecture is characterized by the use of brick as the main material. It also used elaborate tiles and stuccos, especially in mighty bell towers, some resembling an Islamic minaret, and arcaded apses.

Originally, the church dates back to the XIIth century. Closed of course, we could not enjoy its interior which is said to be magnificent.

| It must be said, it is rare to find a village with so much harmony where no building comes to mismatch the whole, like a louse in a sumptuous hair. |

|

|

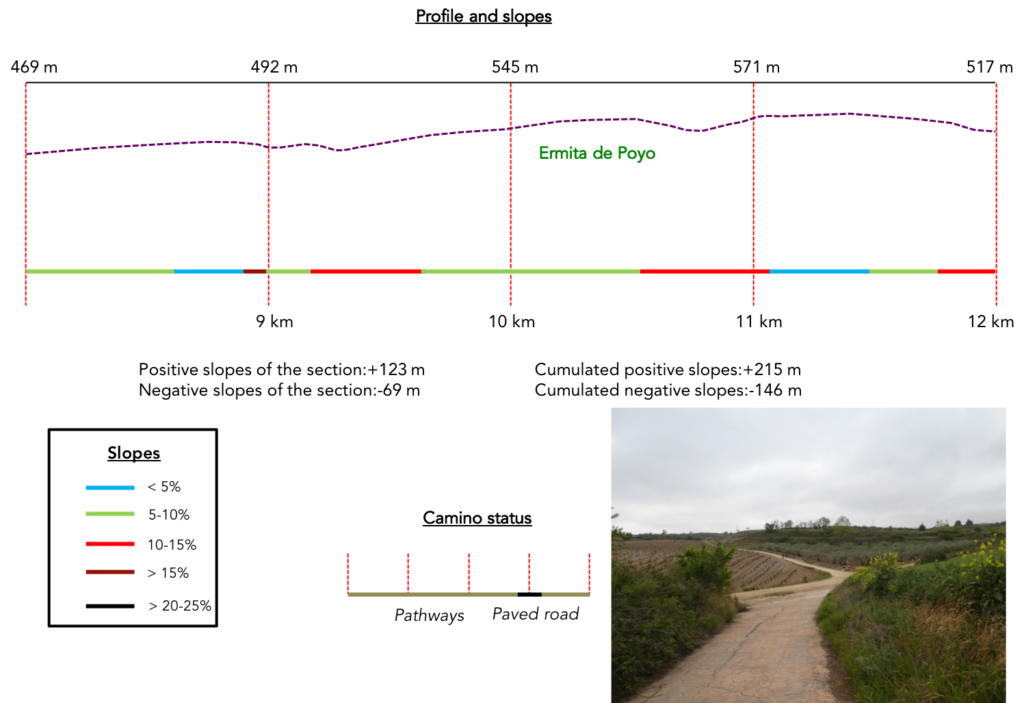

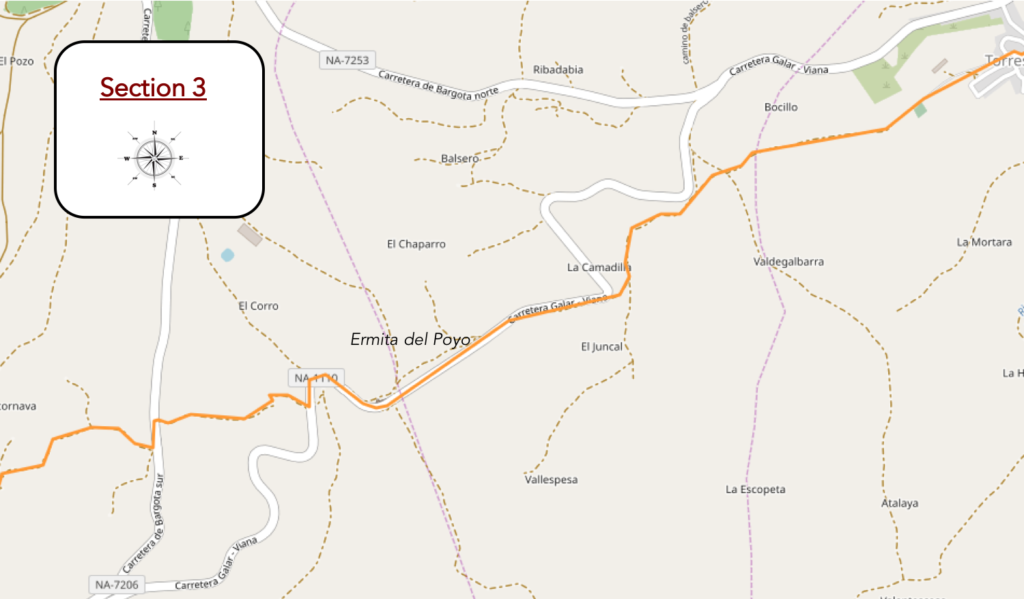

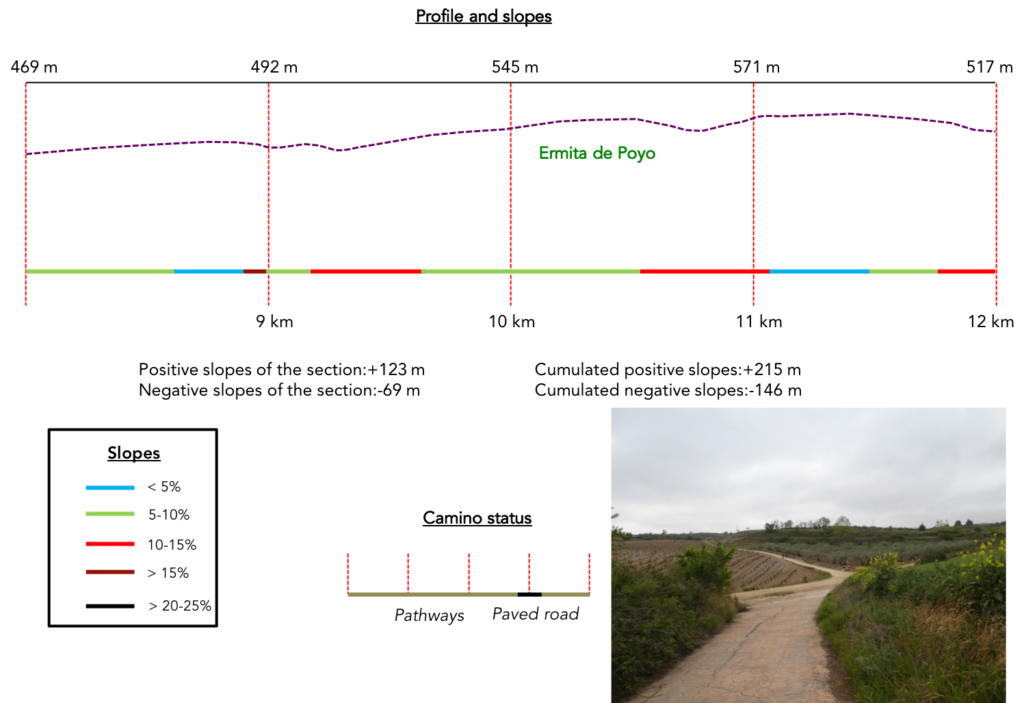

Section 3: Very beautiful undulations in the nature.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: leg-breaking course, with marked slopes.

| The pathway leaves the upper village of Torres del Río among the olive trees. You will rarely see olive trees here in Spain, a paradox, right? |

|

|

| It runs near the cemetery and flattens in the nature, in the middle of cereals and rare poppies or tufts of rapeseed which is re-sawn everywhere in the country. |

|

|

| Then, the country becomes hillier and the pathway will undulate in the fields and vineyards. It does not run very far from the national road. It is hard to understand why in such a vast country the Santiago track has been made so close to the paved roads. But, moment of anger quickly passed, it will be said that traffic, with rare exceptions, is very marginal on these axes. |

|

|

| Nature is again beautiful here, the ground red in the middle of vineyards and olive trees, before the pathway steeply slopes down again in the wild nature. |

|

|

| You went down, so you have to slope up, right? The pathway climbs up on the slabs until you’ll reach the national road that runs above. |

|

|

| But it stays quietly under the road running under the little maples. |

|

|

| Then the route takes on impressionistic hues on a small narrow pathway which climbs steeply first on dirt and then again on slabs. At the top of the climb, which joins the road which had fun making a big bend, the Koreans take the family photo. They most often do it at the top of the hills, as if they were climbing Mount Halla, the highest peak in their country, culminating at less than 2,000 meters in height. But what the hell are these courteous and polite people of Asia doing here? We know that 20% of Koreans are Catholics. But this does not explain everything. They do not frequent churches more than other pilgrims, that is to say very little. One day in the future, a sociologist will perhaps look into it to try to understand how you can go into exile like this for a month, completely outside of your culture. “Buen camino” they say again, as you pass. You greet them with courtesy and sympathy. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway passes on the other side of the NA-100, the small national road that crosses this depopulated region. The pathway continues to climb through olive trees, maples, then through broom. You are less than 500 meters above sea level. Here are the brooms used for anything other than making brooms or are they not there just for your pleasure? The yellow bursts into golden sparkles, but which do not yet smell of honey, in the middle of the dead heather of the past season. When you walk further into the Meseta, 100 meters higher, you will only see the withered stems of this great wonder of nature. |

|

|

| Just up, the pathway reaches a pine forest where beautiful cairns stand. Our Korean lady, whom we meet every day and who also leaves very early, who walks alone, in her inner life, with her headphones on her ears, may have appreciated the arrangements of wild stones that are a little reminiscent of her country. But she will not say a word about it, no doubt foreign to the languages practiced on the track. But she will give you a smile. |

|

|

At the end of the woods, the pathway passes in front of the Poyo hermitage (Notre-Dame du Puy), rebuilt in the XVIIIth century, but closed of course.

| From here, the pathway slopes down first on dirt, then on the slabs to join the national road which does not stop twisting, marrying all the hills. |

|

|

| The Camino then follows the road a little… |

|

|

| … then runs back into the scrubland on dirt, sometimes ochre, sometimes grey. Here, the slope is almost 15%. |

|

|

| Further up, at the level of olive groves, the slope softens and the pathway joins a small road. |

|

|

| The Camino does not stay on tarmac for long. Quickly, it runs on a dirt road along the side of the bare hill, a kind of scrubland with bushes, small maples, boxwood and sometimes a few pines or a few Cembra pines. |

|

|

| Further afield, in the broom shoots, the pathway begins to descend a little more. Then appear olive and almond trees which complete the panoply of trees. |

|

|

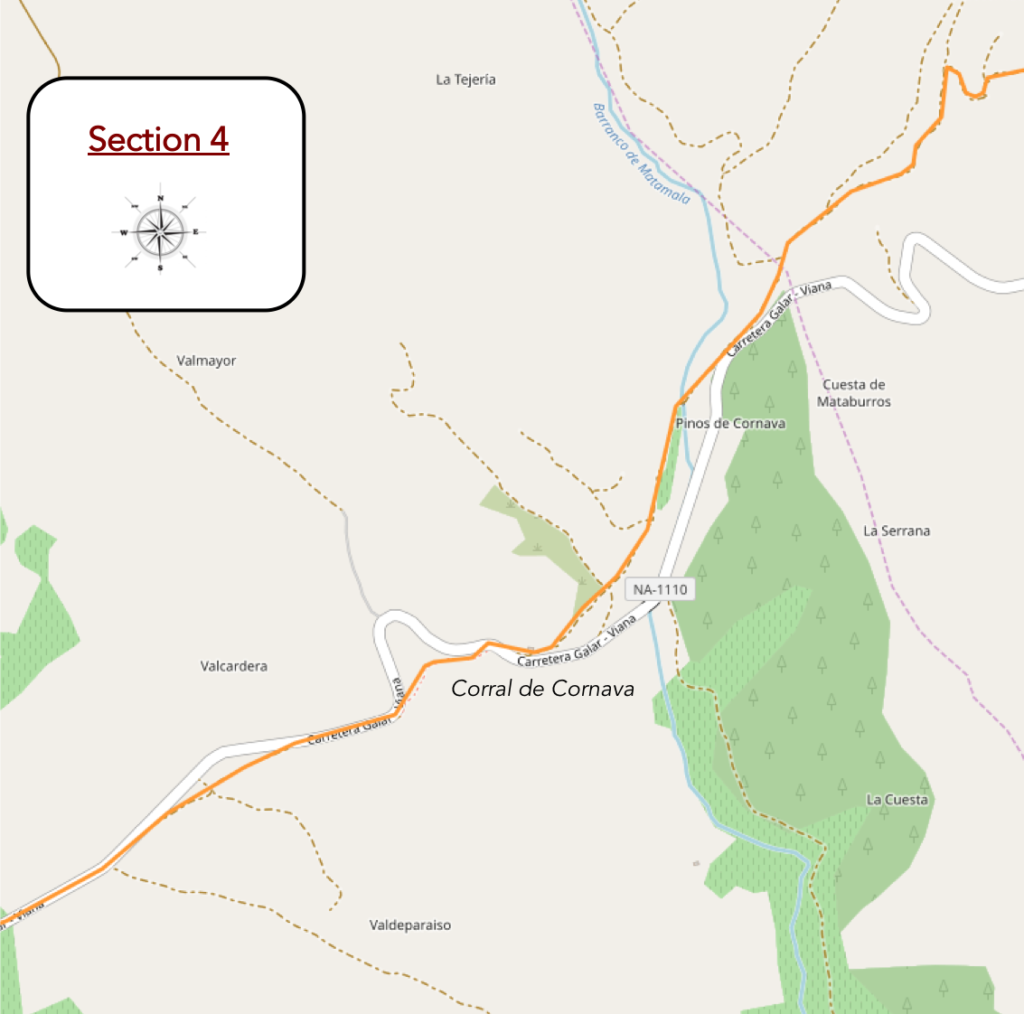

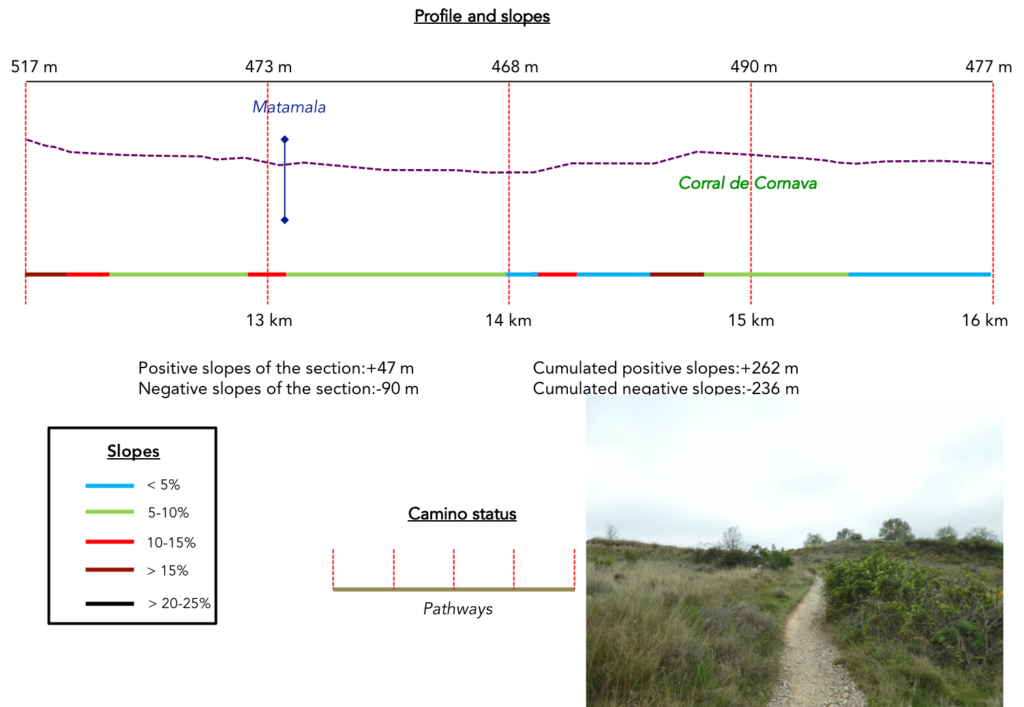

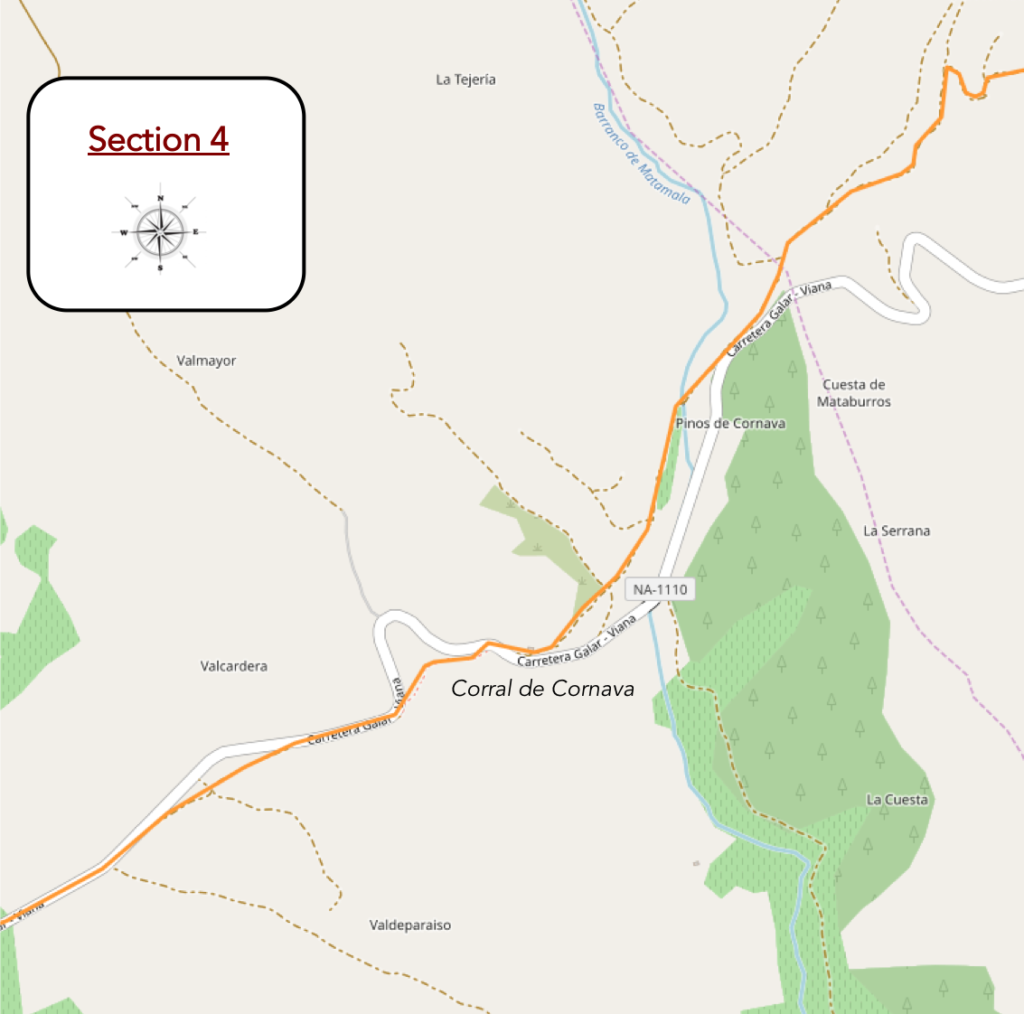

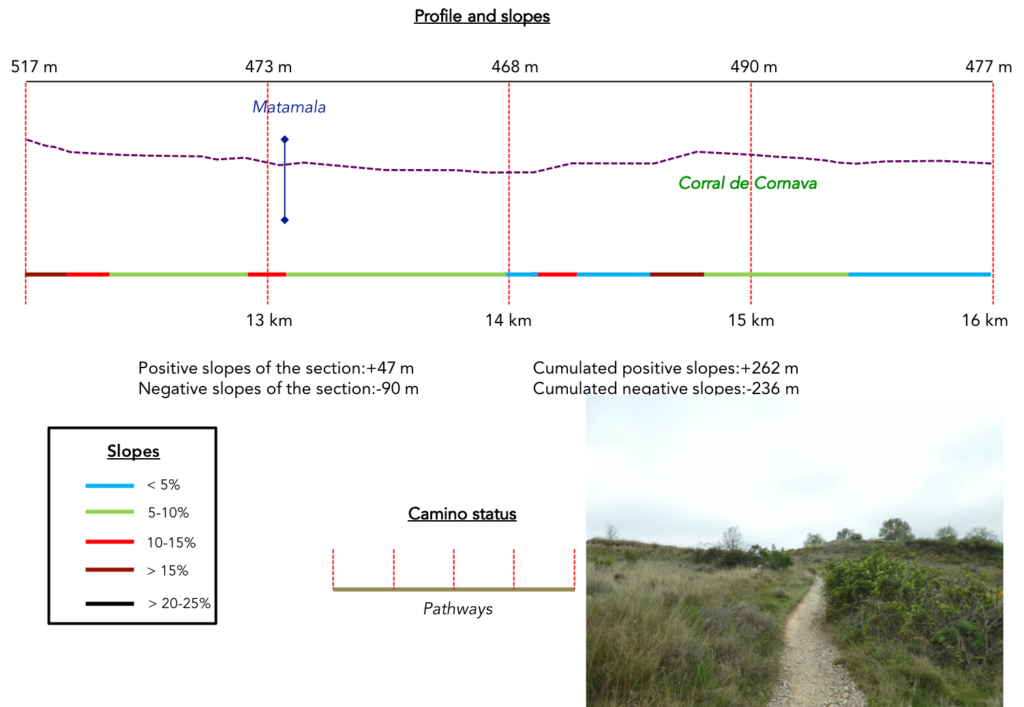

Section 4: Still some ripples on the hills.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course with some pretty bumps, steep, but short, uphill as downhill.

| The pathway keeps on sloping down. There are even steep slopes in the bush. On the hillsides on the other side of the valley grow the vines. Further down are the olive and almond trees that glide through the pine trees on the arid land. |

|

|

| Soon, the pathway reaches the bottom of the dale and runs along lush hedges. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway arrives at the bottom of the dale, where a few vines are nestled in the middle of the bushes. |

|

|

| Shortly after crossing the discreet Matamala stream, the pathway follows vineyards and almond trees. The vines increase in number. You are still in Navarre, but not very far from La Rioja. |

|

|

| Here, you move forward without difficulty, but in front of you stands a pathway where you will have to give a little push. |

|

|

| It’s steep in the broom, boxwood and pines, but it’s short. |

|

|

Further afield, the pathway heads to a place known as Corral de Cornava, lost in the middle of nowhere. Here, you are about 4 kilometers to the borough of Viana and 13 kilometers to the end of the stage.

| But even today, you’ll get trouble getting rid of the NA-1100 road, which follow you. The pathway slopes down to the paved road, crosses and continues. To tell you that the traffic is calm here, you certainly will not cross any vehicle until Viana. |

|

|

| So, for a few hundred meters, the Camino crosses the vineyards, then runs in the virgin nature to make you believe that the paved road is behind you… |

|

|

| … but soon, the paved road is back. But in Spain you can easily avoid tar and walk on the side. Well! The Camino francés is a European way, almost maintained by the gardeners. In dry weather, pilgrims in large numbers will adopt this way of doing. In rainy weather, tar will be used rather than soil, to be not mired in the mud. |

|

|

| Anyway, the course quickly resumes its rights at the edge of the road, before leaving it again. |

|

|

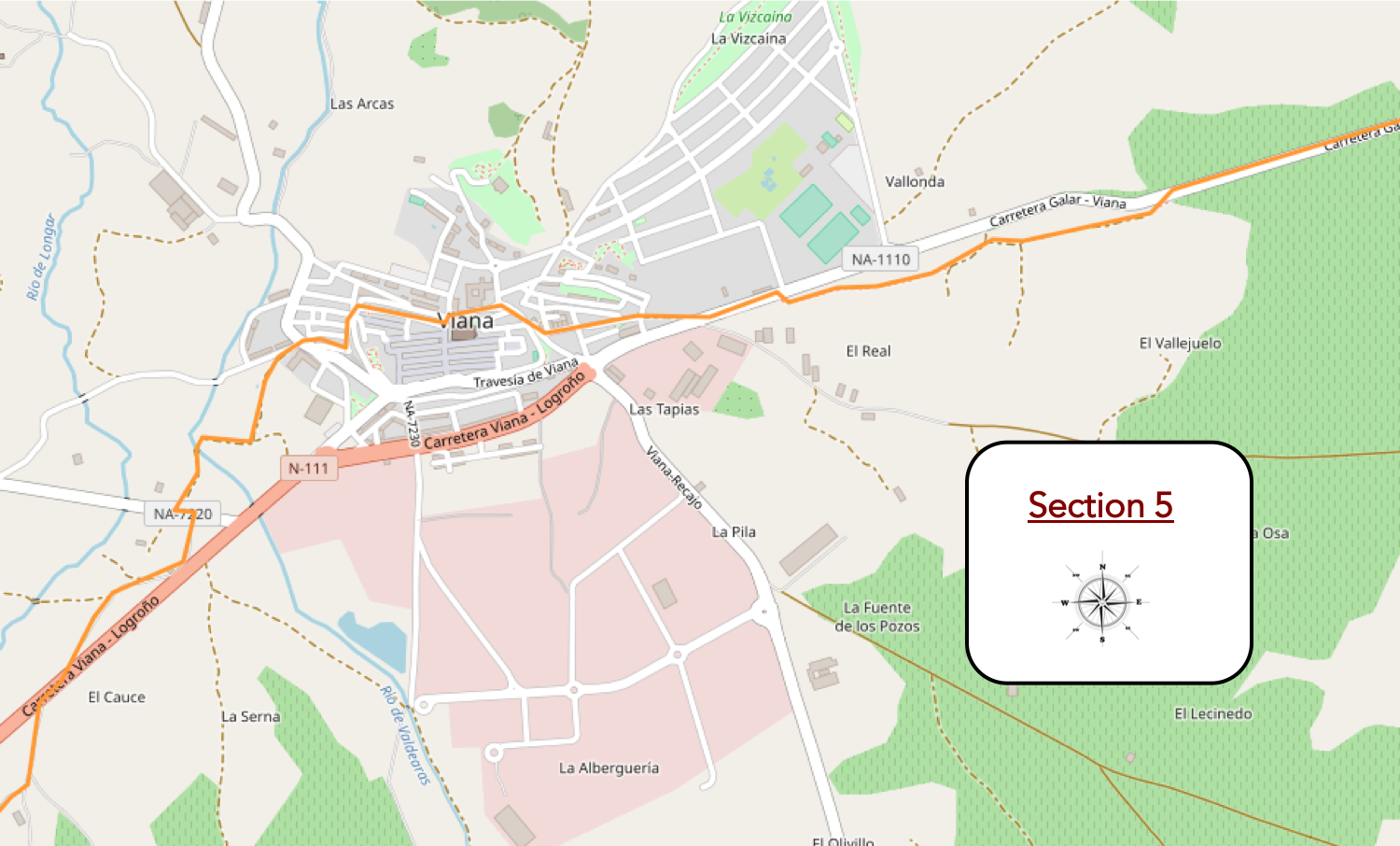

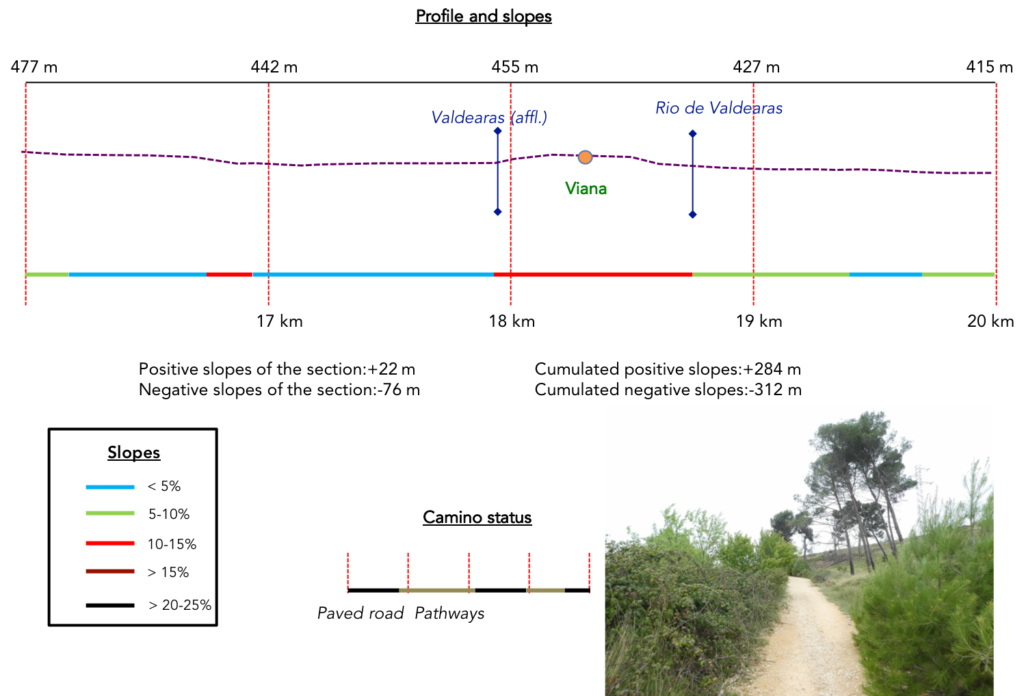

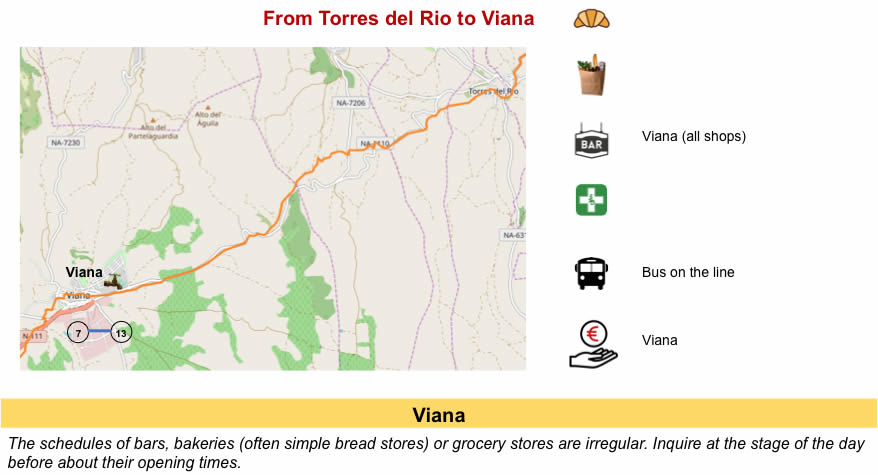

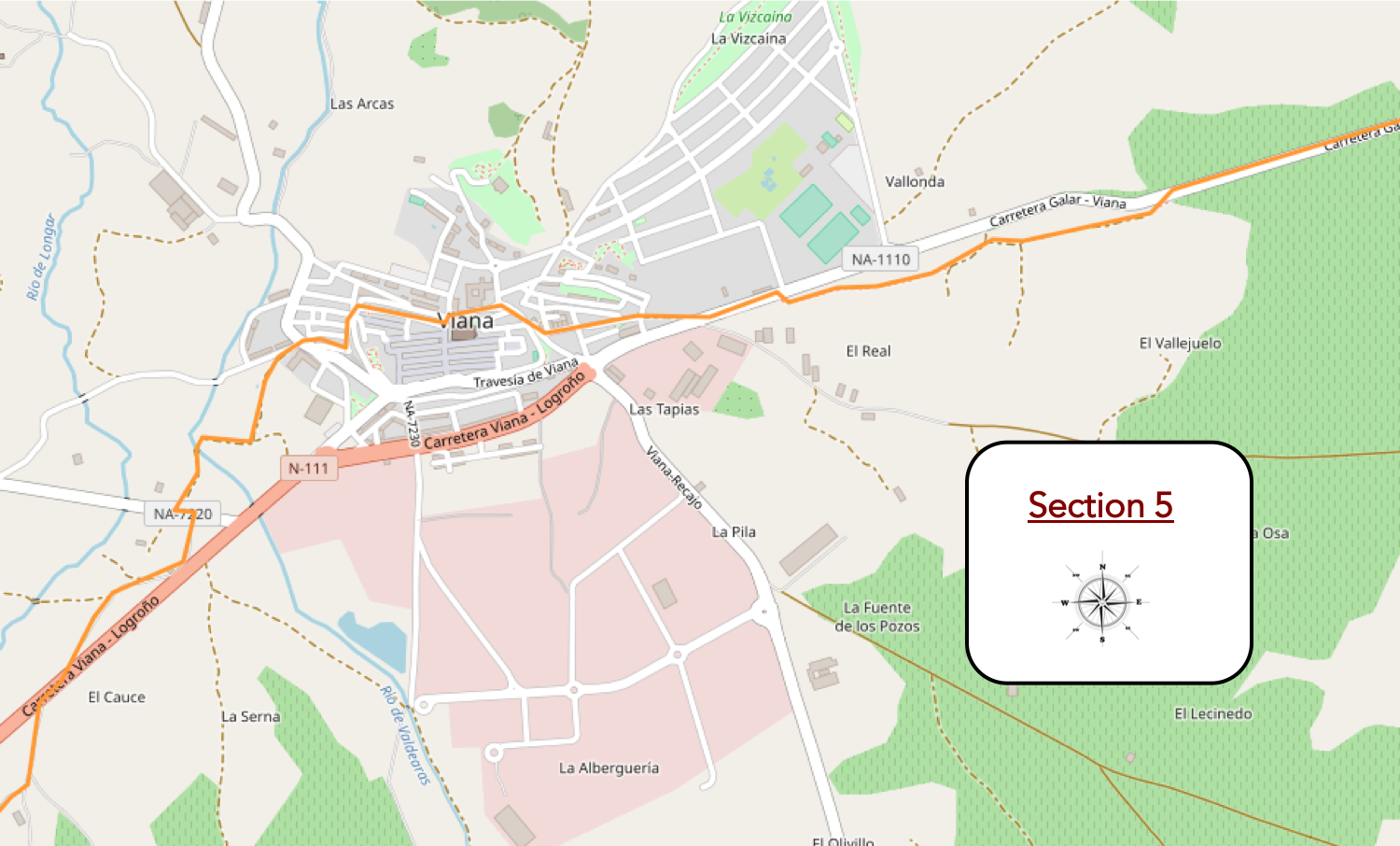

Section 5: Passing through the beautiful medieval city of Viana.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without difficulty, except around the hill of Viana-

| The pathway then lags a little in the bush … |

|

|

| … then comes back to the national road. The Camino francés is so well organized that the track is twice mentioned. The pilgrims are warned that they will cross a road. Motorists are also warned of the presence of pilgrims. From here, count two good kilometers to reach the city of Viana. |

|

|

| There are pilgrims so satisfied with walking the roads that they even anticipate and avoid taking the dirt road. They could simply hitchhike to get to Santiago more quickly. |

|

|

| So, at your choice, take the tarmac or the dirt along the almond trees and the vines. Koreans love tar. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway leaves the road for cereal fields and vineyards. |

|

|

| You’ll see soon Viana growing up on the hill. |

|

|

| Just a stone’s throw from the city, the pathway crosses the tiny Valdearas brook that crisscrosses the plain. |

|

|

| The pathway then crosses again the national road and passes in the lower part of the borough, in the middle of low-cost housing. We imagine that in Viana (4,500 inhabitants), this part of the city must be inhabited by commuters who work in Logroño. |

|

|

| The Camino climbs steeply at the entrance to the old city. The Camino will pass through the historic center of the city founded in the XIIIth century, and which has changed little since the passage of medieval pilgrims. It retains part of the fortified complex and many houses adorned with coats of arms. In the XVth century, Viana was an important pilgrimage stopover with four pilgrim hospitals. Viana is the last town in Navarre on the Camino, near the border with La Rioja. Due to its border location, the city had a checkered past as a defensive garrison against the Kingdom of Castile. The monarchs of Navarre used it frequently as a residence and command post. The heir princes of Navarre held the title of Prince of Viana until they ascended the throne. |

|

|

|

|

| You enter through a narrow door. The city is squared like a country house, with a main street. The whole city exudes a frankly medieval atmosphere. This city, the last bastion of Navarre, has known the same history as the others, with its difficult relations with Castile. Like the villages of the region, it experienced the same boom thanks to the Way of Compostela. It had four hospitals for pilgrims in the XVth century. |

|

|

| If you walk here during Holy Week, when the weather is good, there can be a lot of people, a big market on the narrow street that leads to the town center. |

|

|

| You will then arrive in the center, on the square of Los Fueros, a lively, central square, where stands the town hall, a building from the end of the XVIIth century, with its two towers and its arcades. |

|

|

| Of course, there are also quieter periods, but throughout this harmonious city tourists flock, in the middle of beautiful buildings emblazoned in often Baroque style. |

|

|

| The most celebrated monument is the Santa Maria Church, a historical monument that is like a great cathedral enthroned in the middle of the old town. This imposing church dates back to the end of the XIIIth century, built in Gothic style. The church is high, with a very ornate facade, many chapels, a busy interior, baroque. Its magnificent portal, in the Renaissance style, is later. |

|

|

| Here are buried the remains of César Borgia, condottiere and cardinal, who spent his short life between Italy and Spain, the family being from Valencia and having given popes, each more corrupt than the other. Lucrezia Borgia was his sister, who was probably wrongly accused of all misdeeds, in particular of incest with her brother, of being a poisoner. But it was certainly not a simple family, in a troubled century. César Borgia, who owes his great notoriety to Machiavelli who used him as a prototype in his famous live The Prince, was assassinated here, in Viana, in 1507, at the age of 31. |

|

|

| During Holy Week, the Office is followed with great devotion. |

|

|

| Further on, on the central street, the Camino passes in front of the San Pedro church, the oldest church in the city, dating from the XIIIth century. The original building was remodeled in the XVIth century. With its powerful tower, the building occupied a strategic place on the western flank of the bastide. But it was ruined in the XIXth century, during the Carlist wars, when it became a barracks. This Gothic church, now deconsecrated and partly in ruins. Although in ruins, its XVIIIth century Baroque portal is in excellent condition. There is a piece of fresco under the remains of the chapel. |

|

|

| It is easy to imagine that the building undoubtedly experienced a more prosperous era. |

|

|

Next door stands the Pujadas Palace, a Baroque building from the XVIth century, now converted into a hotel.

| You leave the medieval center, as you entered, through a door that is part of a complex of walls that are still present at the bottom of the city. |

|

|

| The Camino then slopes down on the road to the other side of the city to quickly find nature. |

|

|

| In the vegetable gardens, the Camino crosses the main arm of the Rio de Valdearas. |

|

|

| After crossing a small road, the Camino leaves, sometimes on a dirt road, sometimes on a paved road, in the fields. |

|

|

| Here, the countryside is diverse, and there are side-by-side vacant lots, gardens, vineyards and meager fields of cereals, which is rare, it must be said, in Spain. |

|

|

| Shortly afterwards, the Camino, which became a dirt road, crosses the N-111, the main road, follows it a little, then immediately flattens on a small paved road under the black poplars. |

|

|

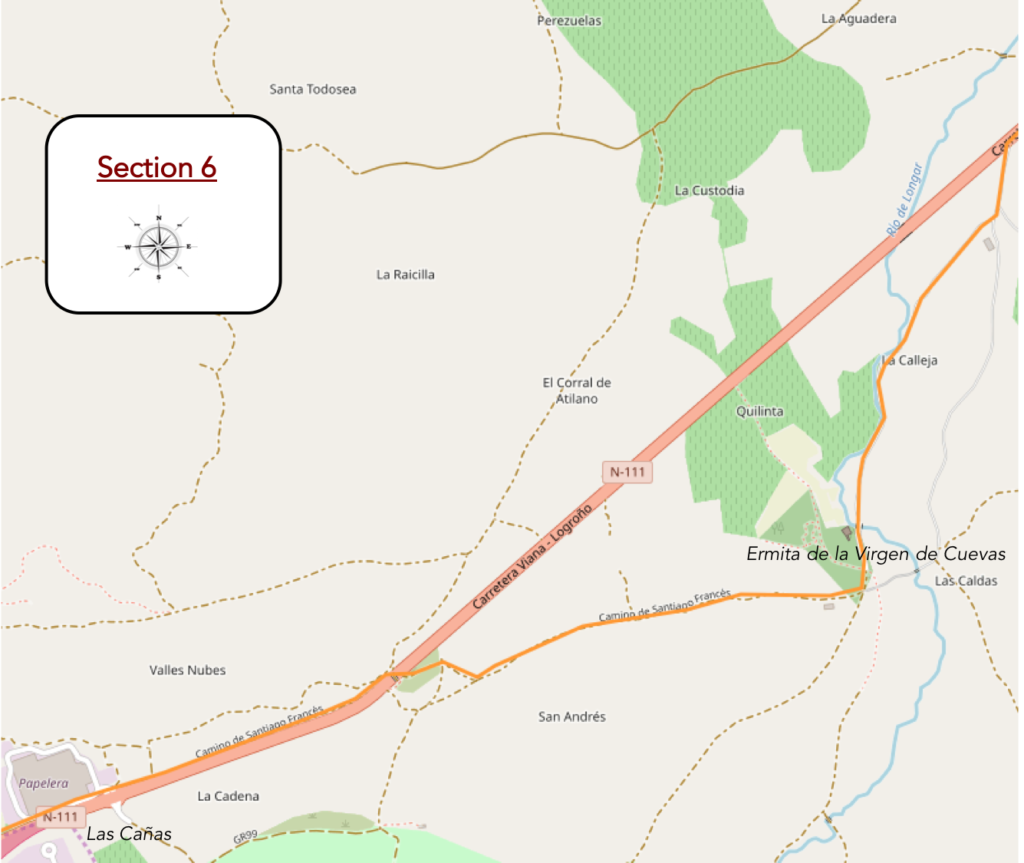

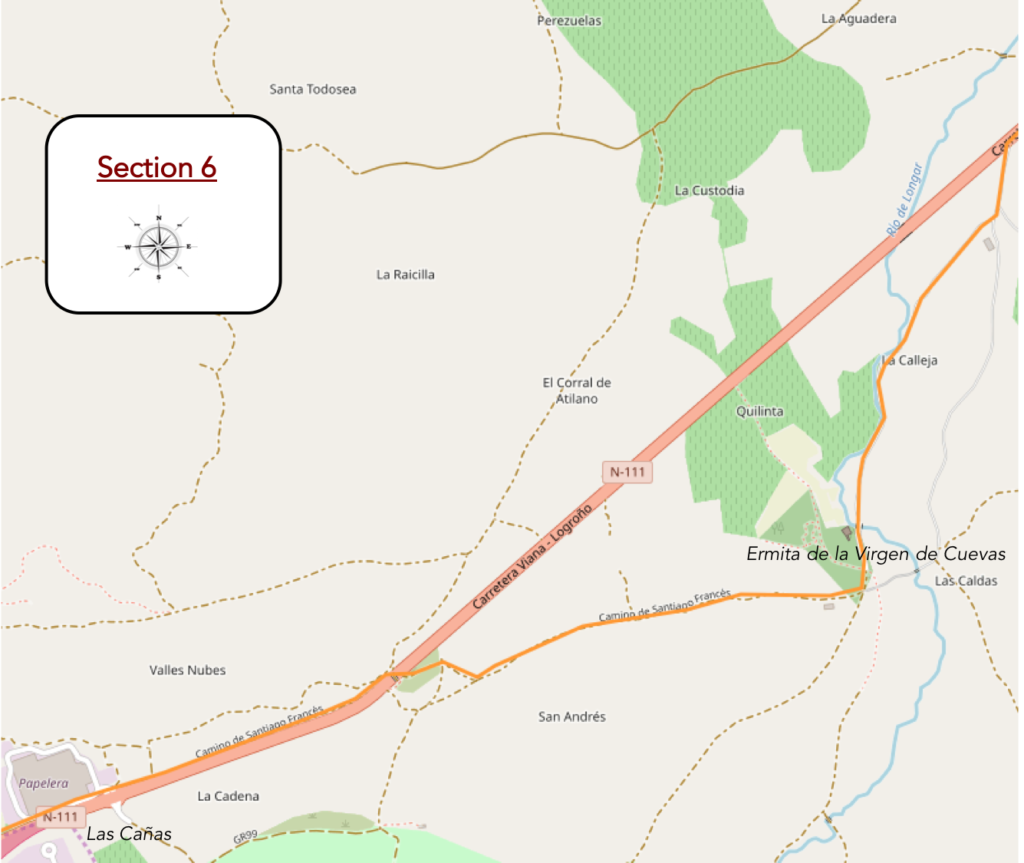

Section 6: From Navarre to Rioja.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without difficulty.

| The road runs now along the Longar stream under the black poplars, along the vineyards. Here a pilgrim drags his cart with high wheels. It’s still easier to do it on the tar. |

|

|

| Further afield, the road crosses the brook, near the Virgen de Cuevas. |

|

|

| You get at the Hermitage of Virgen de Cuevas with its picnic area under the almond trees. The church here is documented since the XIVth century, being mentioned in the famous codex Calixtinus. |

|

|

| Here you are 2.8 kilometers to La Rioja. La Rioja is not a village, which could be confusing on the sign, it is a Spanish province. You are therefore near the border between Navarre and Rioja, Logroño being in Rioja. |

|

|

| But what is this farm doing here, which is not one? An anachronism, we haven’t seen one for a week. No doubt, a shed for storing tractors and harvesters. The pathway then leaves in the plain between vineyards and fields of cereals. On the horizon, the suburbs of Logroño take shape. |

|

|

| The pathway here crosses a long plain. Navarra wines are not as celebrated as Rioja wines. And yet, you came across many vineyards in Navarre, but often discreet and planted in the plains, which is not the best way to produce great wines. On the other hand, for the large wheat fields that cover the plain, there is no problem, apparently. |

|

|

| Further on, you’ll arrive near the border, 5 kilometers to the city center. The pathway then runs through a beautiful pine forest, in which it is necessary to do some gymnastics on a complex wooden bridge to cross the national road. |

|

|

| Here, the traffic is a little more present. You are still next to a city of 150,000 inhabitants. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway runs along the road, most often under the pines. |

|

|

| Shortly after, you’ll see the Ebro, the great Spanish river, flowing in the plain. |

|

|

| At the exit of the pine forest, the pathway gets in Las Cañas, in the industrial suburbs, 4 kilometers from Logroño. |

|

|

Section 7: The track is getting closer to the city.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without difficulty.

| The Camino then enters the Rioja at the Rio del Nabal. The autonomous region of La Rioja is the first wine region in Spain. La Rioja takes its name from the Río Oja. It is separated by the Río Ebro from the Basque Country to the north and from Navarre to the east. When Spain became a union of 52 provinces in 1822, one of them was Logroño. La Rioja only regained its name in 1980.

You could have imagined seeing the Camino flattening to the city, but it has another program for you, a little sportier. |

|

|

| Shortly later, a small paved road passes again under the national road and climbs in the banks on the Camino Viejo de Viana, the old road of Viana. |

|

|

| The road gently climbs until you cross a road under a tunnel. |

|

|

| The pathway continues to climb a little through poplars and vines to a small plateau lined with granite posts, symbolic of the track. Then, you can see the city below. |

|

|

| Beyond the plateau, the road gently slopes down towards the city between meadows and vineyards. |

|

|

| A local lady is trading on the side of the road trying to bait the pilgrims with her stamps for the « credencial ». In Spain, gardens are often hung in pots on the facades. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, in a profusion of green, where the rapeseed is everywhere, the paved road crosses the Rio Grande, whose only name is big. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino then arrives a few steps from the city, in a large park along Ebro River.. |

|

|

| It soon reaches the stone bridge crossing Ebro River. This is one of the 4 bridges that lead to the city. The bridge was the key to the development of the city. There was here a XIIth century bridge, with defense towers, which would have been erected by San Juan de Ortega, the holy builder. The current bridge, the most important in the city, dates only from the end of the XIXth century. It is simply called “Puente de piedra” (stone bridge), in opposition to the iron bridge that passes a little further. Ebro River is the largest Spanish river. It stretches for nearly 1,000 kilometers, starting from the north in Cantabria, crossing Castile, Rioja, Navarre and Aragon to reach Catalonia, not far from Tarragona. |

|

|

| Beyond the bridge, just follow the shells on the pavements of Rúa Vieja, one of the oldest streets of Logroño, then Calle Barriocepo. These streets were once the heart of the city, with blazons still visible on the facades.. |

|

|

| At the end of these narrow streets, very colorful, you will arrive somewhere between the Casco Antiguo and the new city, near the Calle Once de Junio and Plaza Alférez Provisinal and its roundabout. Here is a statue that you can believe attributed to the pilgrims, two walkers, right? For once, that’s not the question. This is to commemorate a small trip of 63 kilometers to the Valvannerada Sanctuary, organized each year by the Association of Blood Donors of La Rioja. |

|

|

Section 8: A litte tour in Logroño.

Logroño, the capital of La Rioja is traditionally a center of pilgrims. It lies between the Rioja Alta (the wet and mountainous western part) and the Rioja Baja (the flat and arid eastern half). The old town is bordered by the Río Ebro and the medieval walls. The Puente de Piedra (stone bridge) was built as part of the pilgrimage route. The town is the center of the Rioja wine trade. The churches, i.e. the main monuments are quite grouped.

http://centrodelaculturadelrioja.es/files/uploads/pdf/plano-turistico-logrono.pdf

| When you enter the city, at Rúa Vieja, the first monument you will see is the hermitage of San Gregorio. There was a XVIIth century hermitage here, built over the house where the saint died. The latter is known to have made the way with another well-known saint in the country, Santo Domingo de la Calazada, to whom the way passes further. In 1994, the hermitage was demolished and rebuilt with the original stones.

A stone’s throw away is the Church of Santa María del Palacio, so named because it was built on the base of a palace donated by the King of Castile. It is also called “La Aguja” (the arrow). It is an XIth century church, rebuilt in the XIIth century, then enlarged in the XVIth century. |

|

|

| Inside, you swing between Gothic and Baroque, without deep unity. |

|

|

| Logroño is a succession of charming little streets that intersect each other, and a more central artery, Calle Portales, with shops and the cathedral. By small streets, you will quickly arrive at the cathedral. |

|

|

| As with all cities in the region, Castile has dominated the country’s history for a long time. And when the King of Castile granted these cities the privileges (fueros), with the development of the Way of Compostela, churches were built, one after the other. Santa Maria la Rotonda was a Romanesque church, but located in the suburb, a little away from the road. So, the church was razed, considered too small, and a cathedral was built at the beginning of the XVIth century, a construction that lasted several centuries. The church today opens onto the Plaza del Mercado. Its main facade is a vaulted form, flanked by two high ornate baroque towers, the twins. The naves are Gothic, but Baroque additions are present throughout the building. Around the side walls are chapels. In 1959, the former collegiate church of Santa María de la Redonda received the title of concathedral because, together with the Cathedral of Calahorra and that of Santo Domingo de la Calzada, it is the seat of the Diocese of Calahorra y La Calzada-Logroño. . |

|

|

|

|

| Quite paradoxically for Spain, for a cathedral, it is a fairly sober building, with bare pillars and vaults that rise very high |

|

|

| But, of course, there are sometimes a few more golds and bronzes, like the high altar which shines with a thousand lights. |

|

|

| It can get crowded on Saturdays or holidays on Calle Portales, near the cathedral. |

|

|

| Just near, the Rúa Vieja leads to the Church of Santiago el Real, on the facade designed as a triumphal arch, in which is a niche representing Saint James, the first representing him as a pilgrim, the second as a warrior on horseback. This church is the oldest church in the city. Originally Romanesque, it was destroyed by fire. It was therefore rebuilt in the Gothic style in the XVIth century and a tower was added. If you like gold and bronze, you will find what you are looking for inside this monument classified as a historic monument, probably not because of its historicity, but because of St Jacques and because it is here that the former city council. The building is very dark. Even the statue of the Virgen de la Esperanza (Virgin of Hope), patroness of Logroño, disappears into the shadows. |

|

|

At the time we visited, we were preparing the services for Holy Week. In Spain it is a real institution. Unfortunately, the week was rotten as ever. So, people gave up on exhibiting religious heritage everywhere in Spain. We understand. The Spaniards cried real tears. The second time we passed by here, the church was closed. This happens very often.

| You still have a church, which is worth visiting for its external architecture. It is the San Bartolomé church, the most authentic. The Church of San Bartolomé is the oldest church in Logroño. Its construction dates back to the XIIth century, then, it evolved thereafter in Gothic style. |

|

|

| The arched portal is remarkable, Gothic, ogival, carefully ornamented, containing Romanesque sculptures which tell the life of Saint Bartholomew and other passages from the Bible. |

|

|

| It is good to stroll the day on Calle de San Nicolás or Calle Portales. At the end of the street towards the city center, you have the Parliament of Rioja, which looks like a large glazed church. |

|

|

| It is good to stroll in the evening in the Calle Laurel district. Logroño is famous for its pincho bar. Pinchos or pintxos are the name of tapas from northern Spain. There are more than 50 taperias (tapas restaurants) located near the city center. The pincho bars are grouped around two narrow streets close to each other in the old town: Calle de Laurel, known as the “path of the elephants”, and Calle San Juan.

In the Casco antiguo, unusual things can appear at any time, such as the chimney of a tobacco factory, a cowboy or a statue from another time. |

|

|

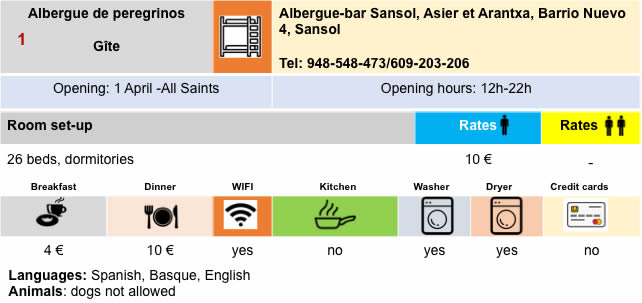

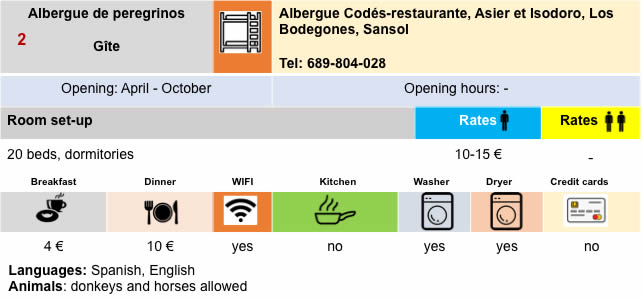

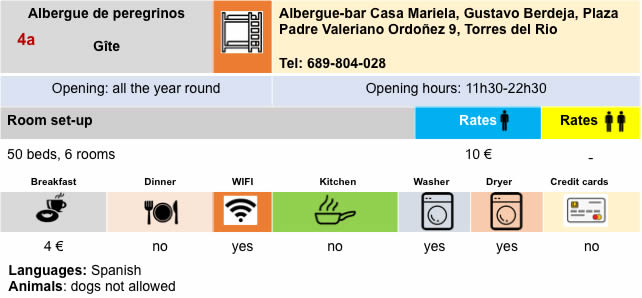

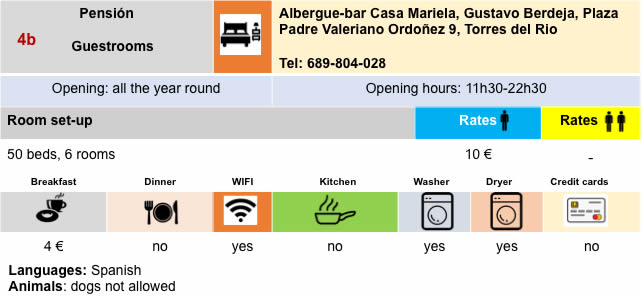

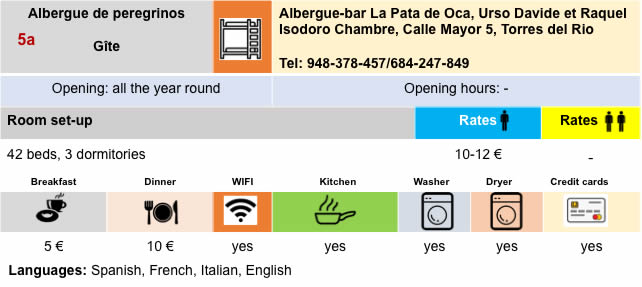

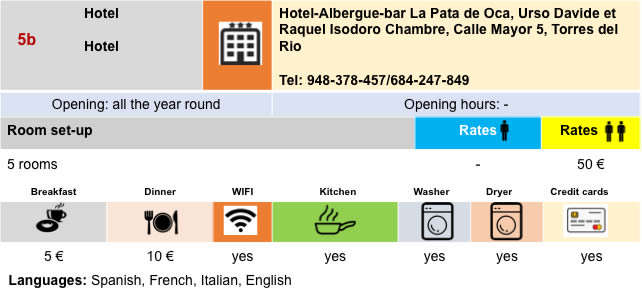

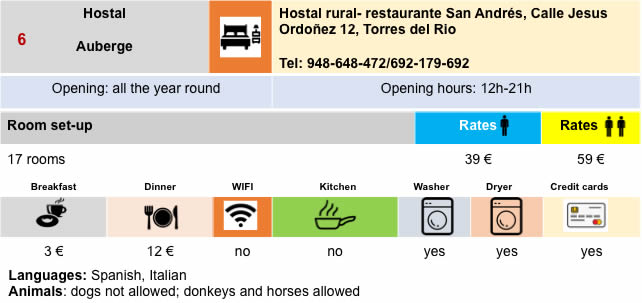

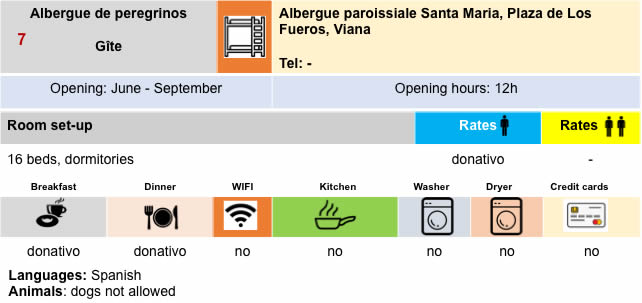

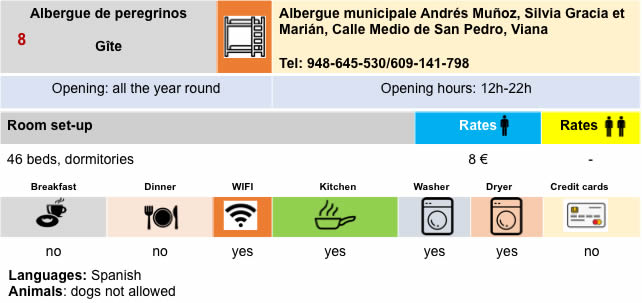

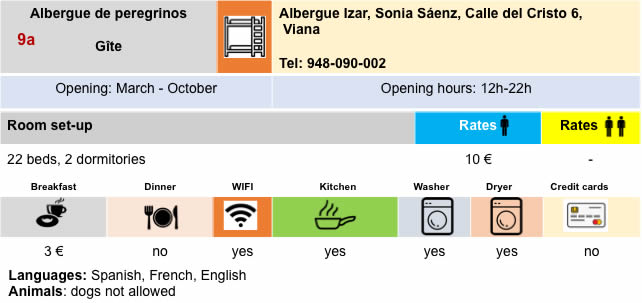

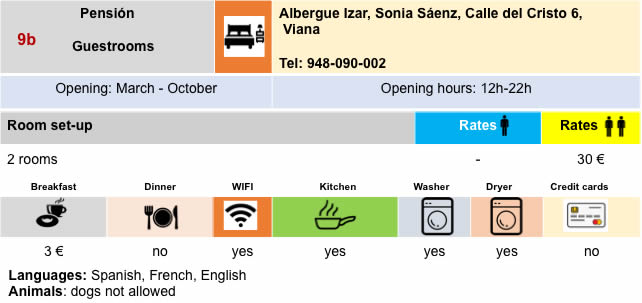

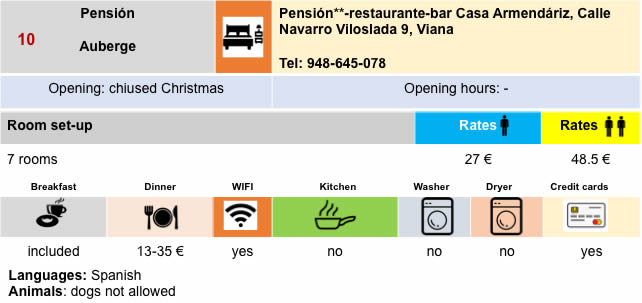

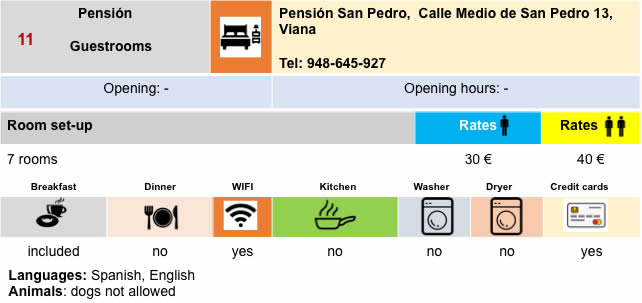

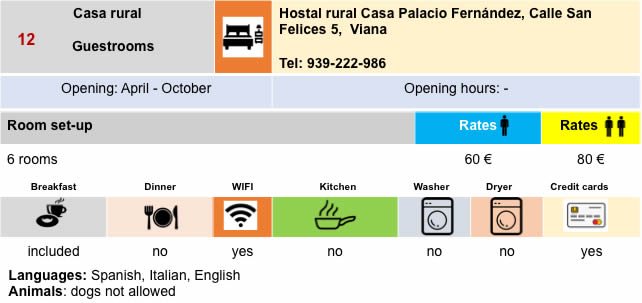

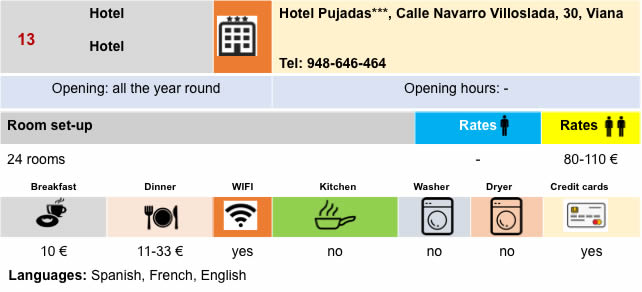

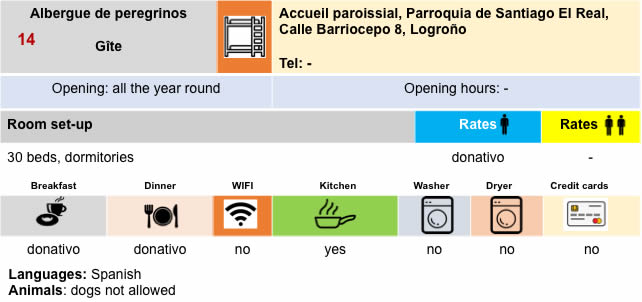

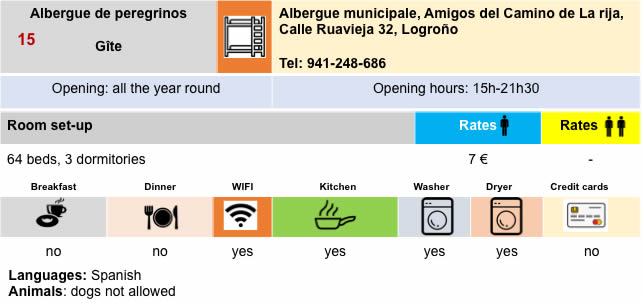

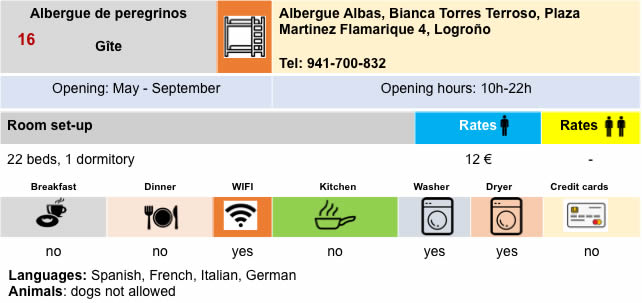

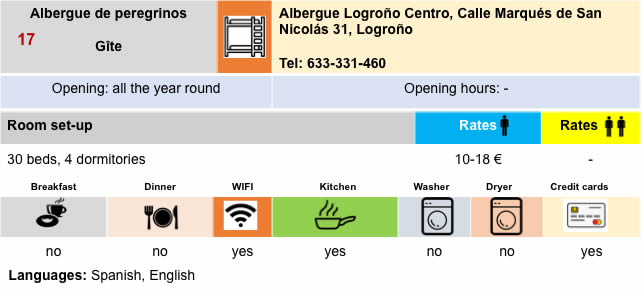

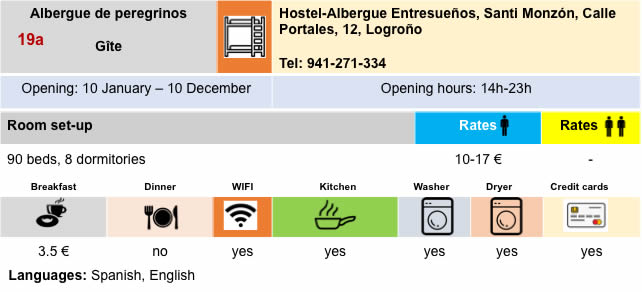

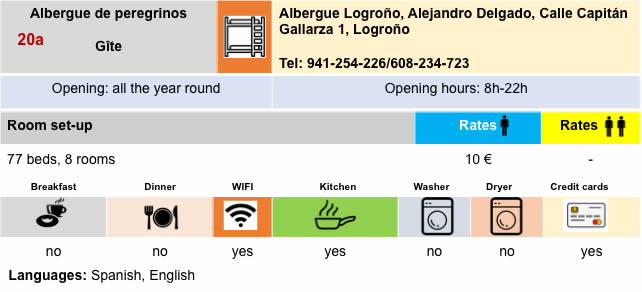

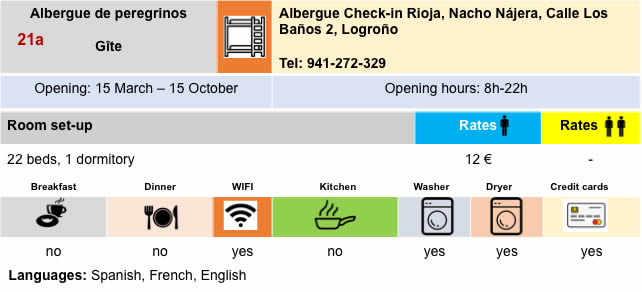

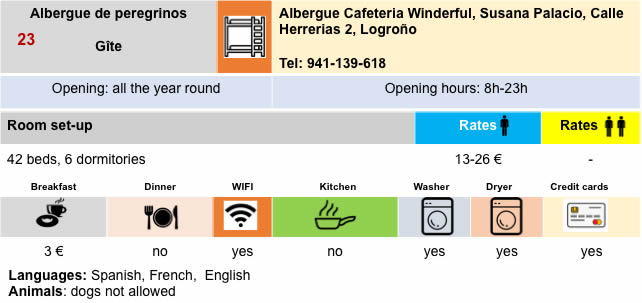

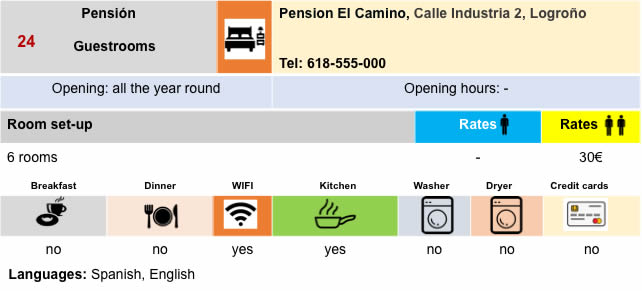

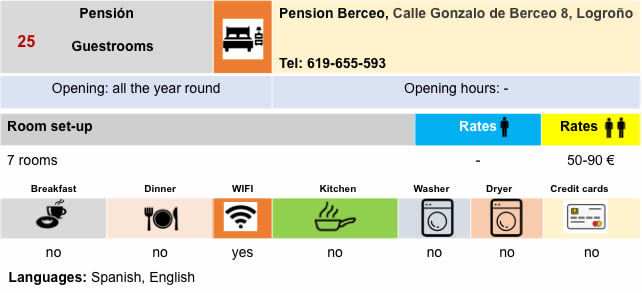

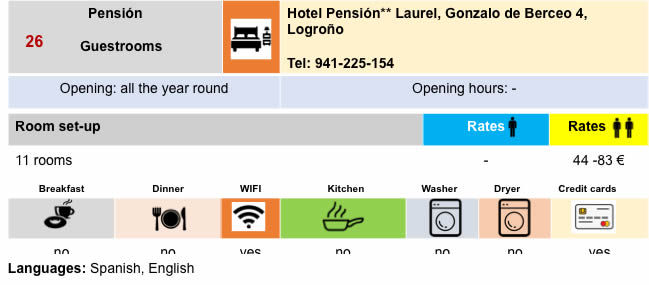

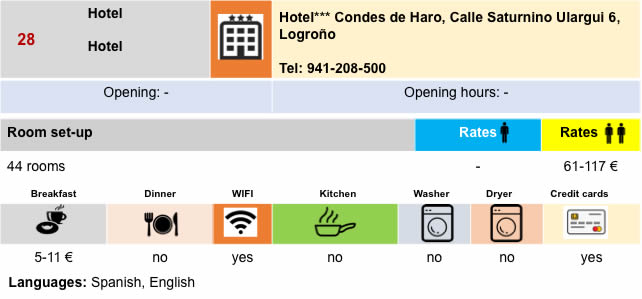

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 8: From Logroño to Nájera |

|

|

Back to menu |

In this stage, there is a lot of paved road, because the approach of the city is on the tar. But, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads :

In this stage, there is a lot of paved road, because the approach of the city is on the tar. But, most of the journey is still on the pathways. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true pathway, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads :