In the Oca Mountains, home of Juan de la Ortega

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-belorado-a-atapuerca-par-le-camino-frances-33793122

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

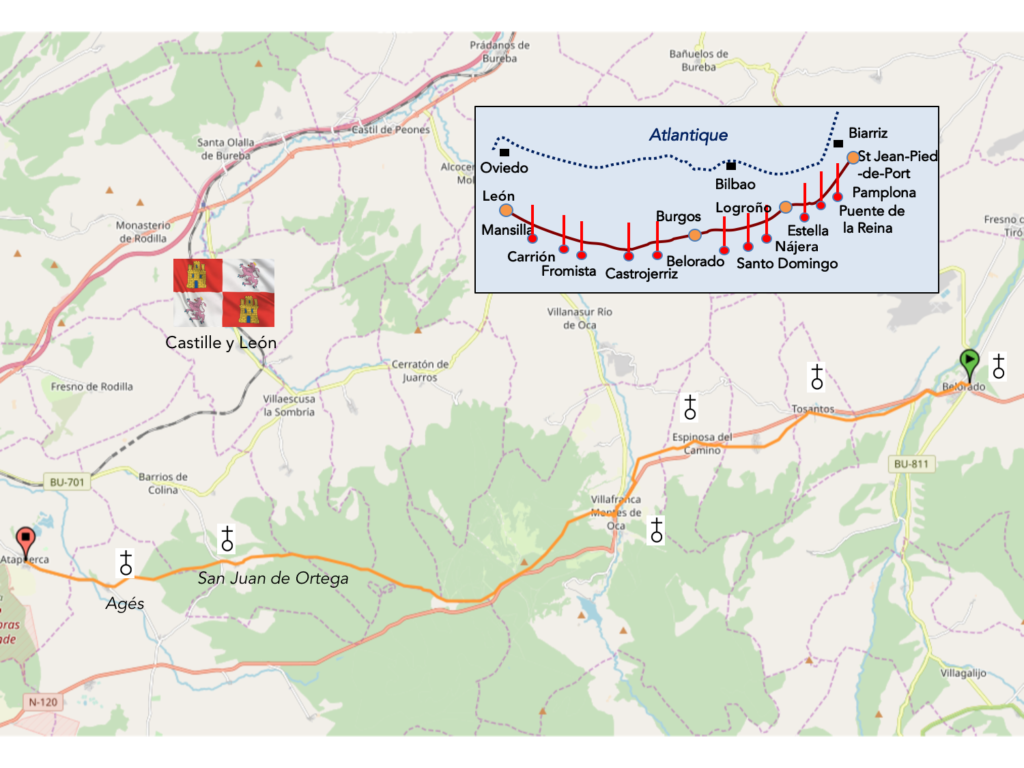

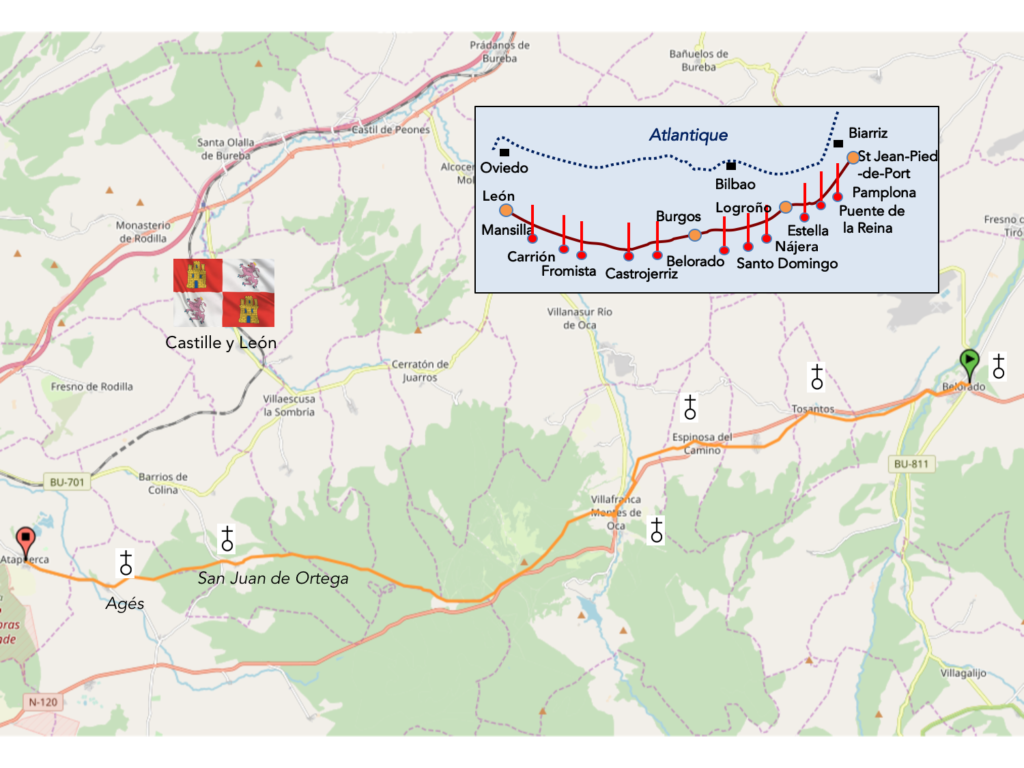

Spain has alternated between regionalism and centralization several times over the past century and a half. In 1869, present-day Castile and León plus the provinces of Santander (now Cantabria) and Logroño (now La Rioja) drafted the Castilian Federal Pact, which provided for the creation of a federal state under the name of Castilla La Vieja (Old Castile) made up of 11 provinces. However, the fall of the First Republic in 1874 put an end to this initiative. During the Second Republic, especially in 1936, there were many attempts to promote regional autonomy. However, the establishment of a centralizing regime after the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) put an end to these aspirations for regional autonomy. In 1983, Old Castile officially became Castilla y León, which is the largest autonomous region in Spain.

Today, it is one of the most beautiful stages of the Camino francés. You’ll climb up to 1’150 meters to reach a pass in the beautiful Oca mountains. Finally, here, mountain, say rather high hill. For at least one day, we’re going to leave the weary loneliness of N-120 road for the enchanting landscapes of Monte d’Oca forests, where you might meet wolves, who knows? These forests are the chosen domain of a saint, a great friend of Santo Domingo de la Calzada. It is to both of them that we believe we owe the current track in Rioja and Castile y León. Juan de Quintanaortuño, known as Juan de Ortega, lived between the XIth century and the XIIth century. He was a disciple of Santo Domingo de la Calzada. In Spain, he is the patron saint of the “roadmenders”, the name given to the pious men who have been responsible for the maintenance and development of the pilgrimage routes. In his youth, Juan de Ortega collaborated with Domingo de la Calzada to open and improve the pilgrimage routes. According to tradition, it is attributed the completion of the road between Nájera and Burgos and the completion of the construction of bridges initiated by his master, in Nájera, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, Belorado, and Agés.

In 1109, when Domingo died, he went to Jerusalem. He almost died in a shipwreck, but he managed to escape by imploring San Nicolás de Myra, an Italian saint of Bari, to whom he promised to build a chapel in his honor. The place chosen was a place full of nettles and infested with brigands, named Ortega (Latin Urtiga, French nettle). Then, he erected a hospital for pilgrims next to the chapel. He then decided to build a real monastery in 1138, founding a community of religious adopting the rule St. Augustine. Juan de Ortega died in 1163, in Nájera, buried in the church of San Nicolás of his monastery. Many miracles are attributed to him. The monastery survived somehow. Poverty set in and the rules relaxed at the beginning of the XVth century. The Bishop of Burgos brought here a community of Spanish monks of the order of St Jerome. At the end of the XVth century, Isabella the Catholic, queen of Castile, but also of nearly half of Italy and Spain, who came on pilgrimage to the monastery, had the nave of the church and the chapel of San Nicolás rebuilt. Then gradually, the monastery fell into disuse. In 1835 it was sold. It was not until 1931 that it was declared a national monument and restored in the 1960s.

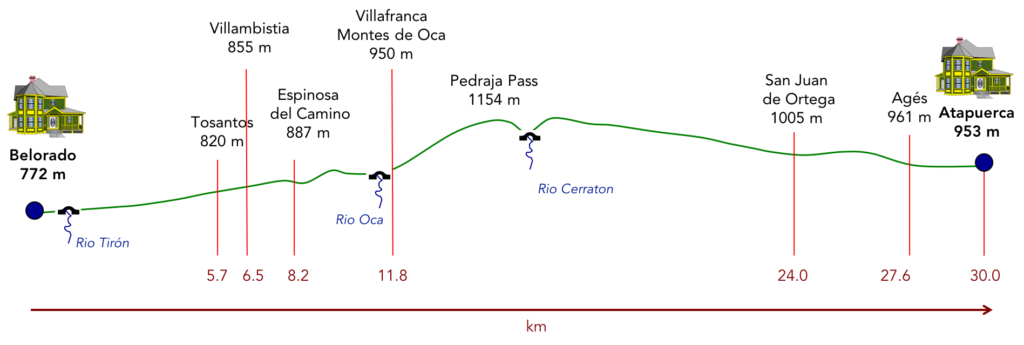

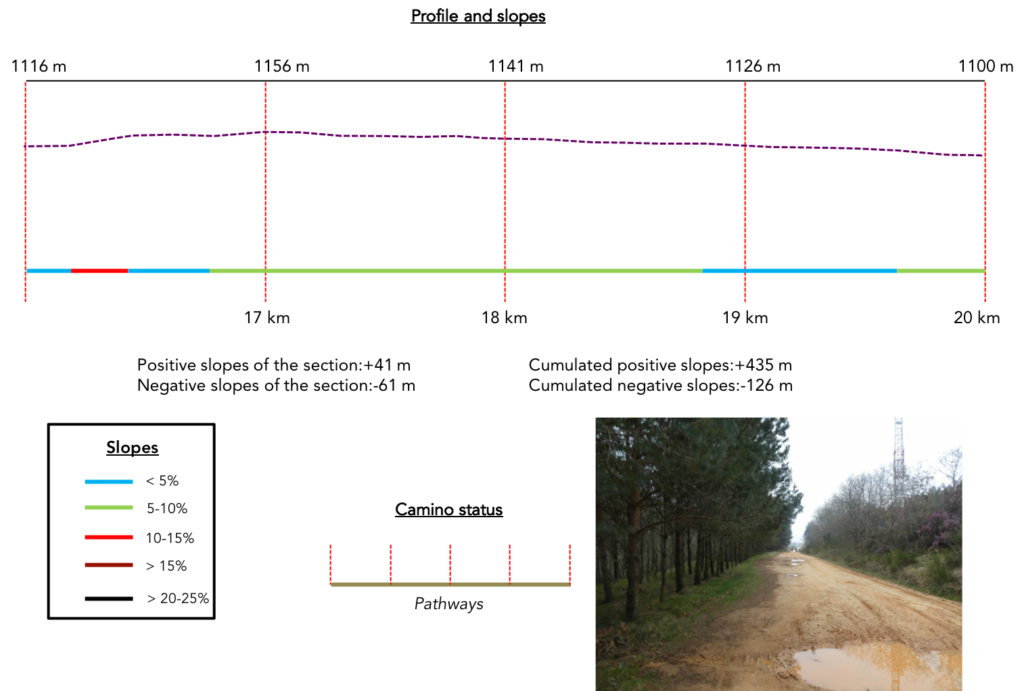

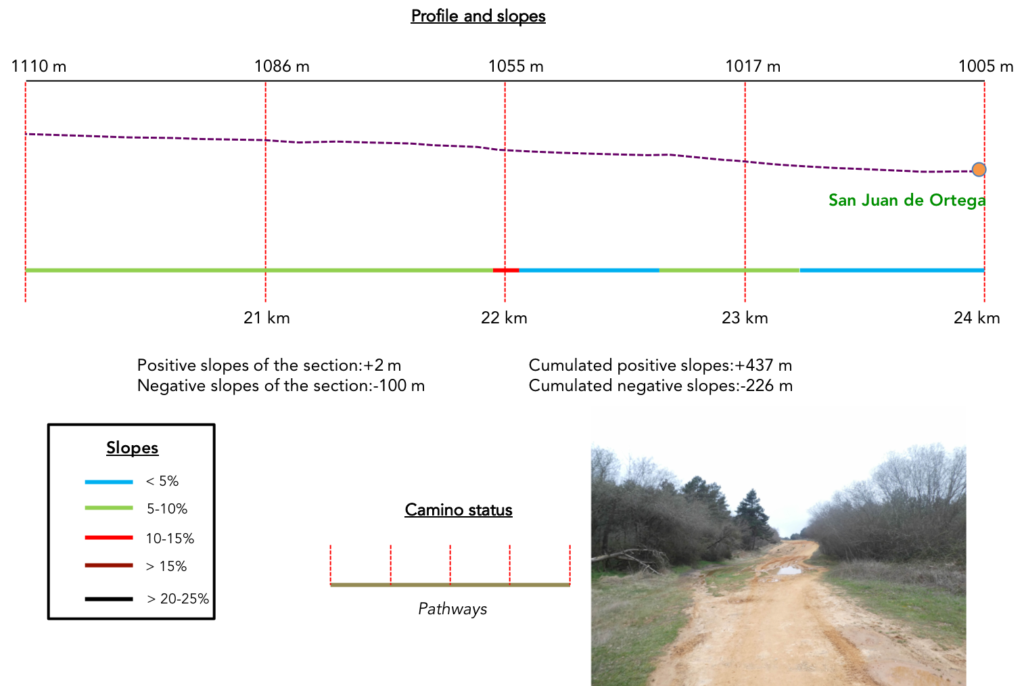

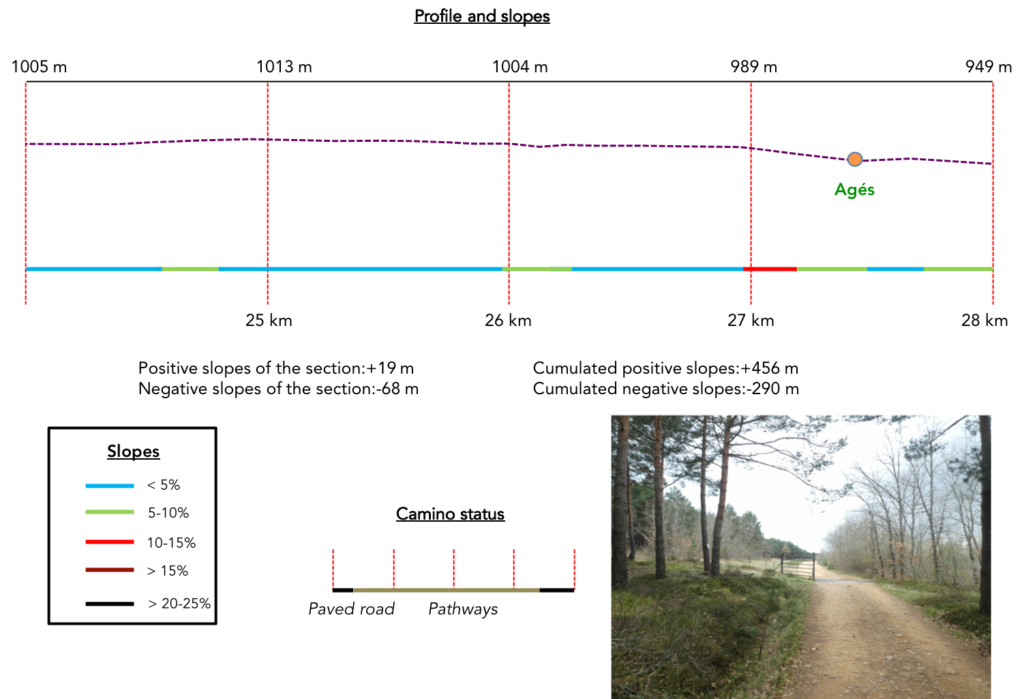

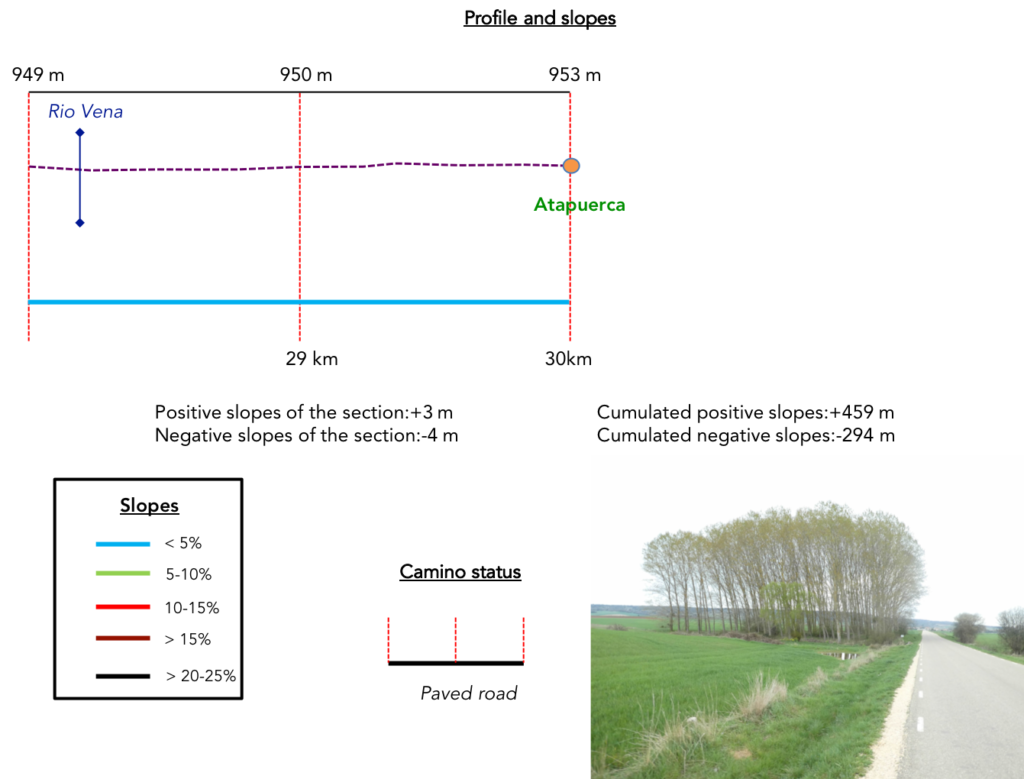

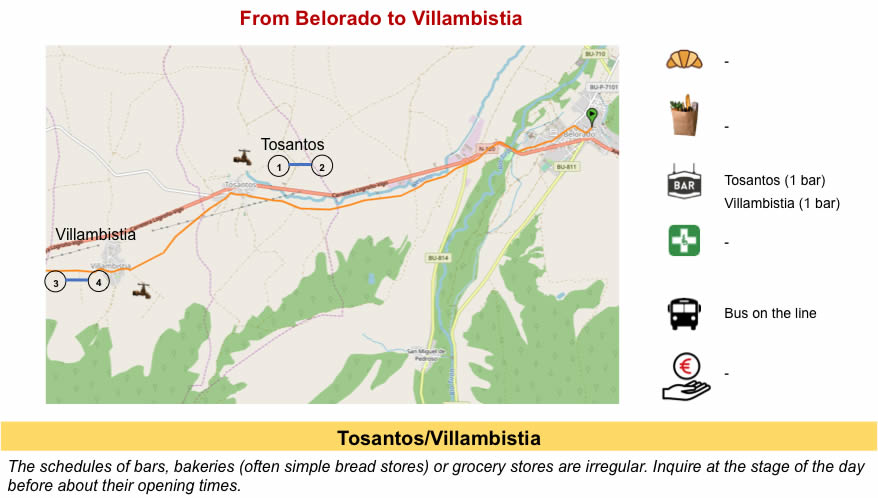

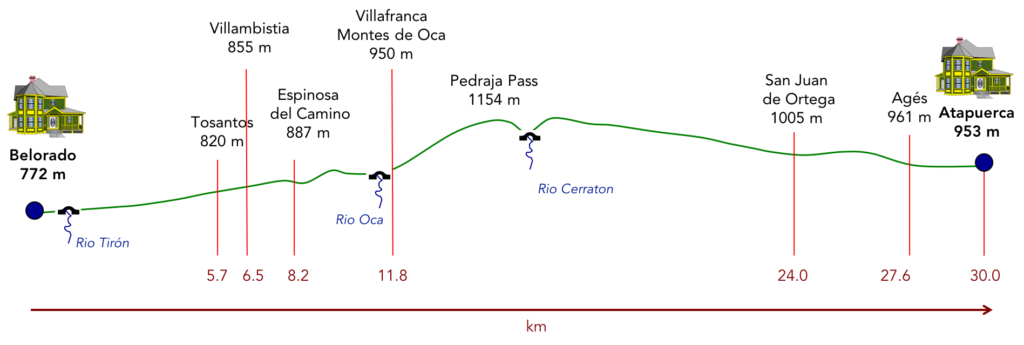

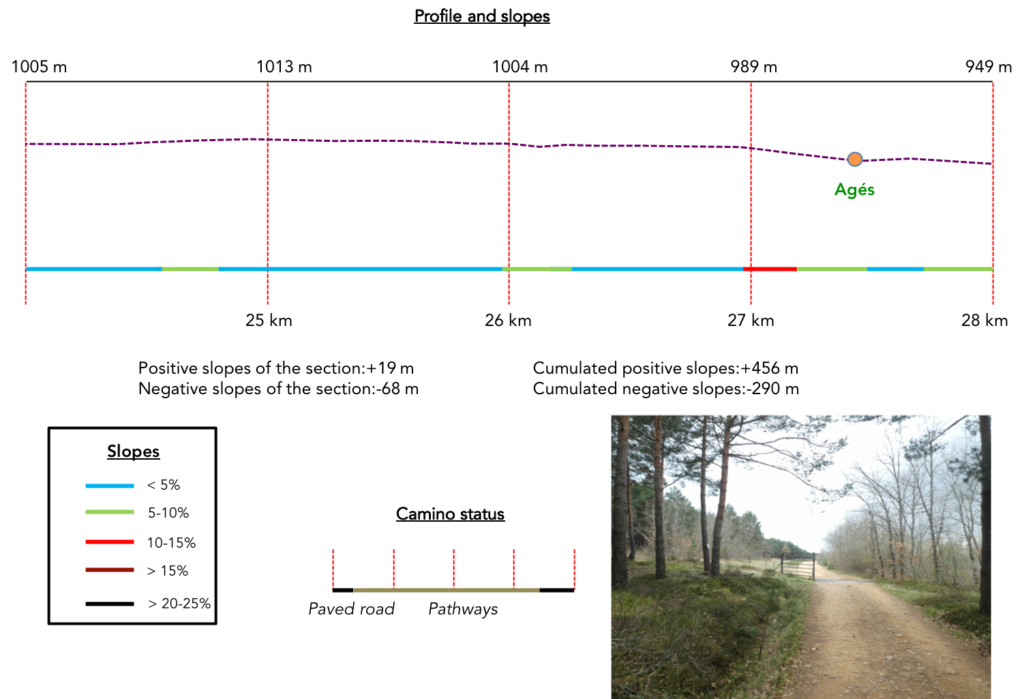

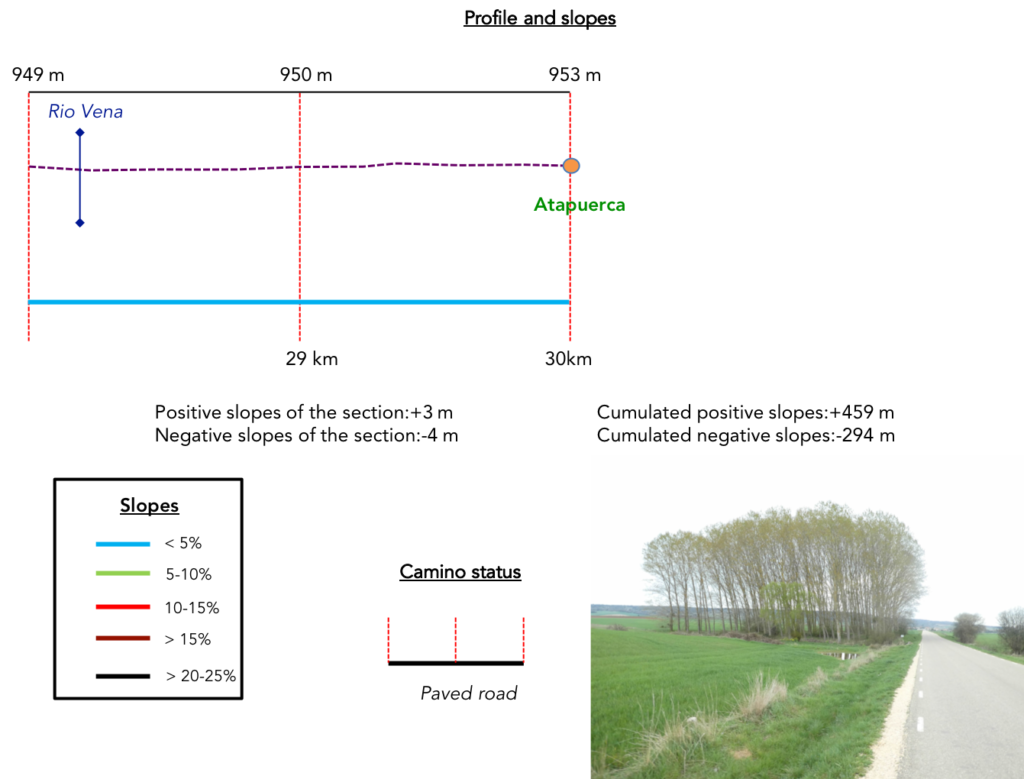

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations of the day (+459 meters /-294 meters) are more marked than the previous days. There is reason for that. It is necessary to climb to Pedraja Pass at the top of Oca Moutians. But, except for this passage, the rest is a walk on gentle hills.

In this stage, most of the route is on the paved roads. In Spain, apart from villages and towns, paved roads, for the most part, have grassy strips or dirt on the sides. Thus, the Camino francés is above all a true dirt road, compared to other tracks of Compostela in Europe, where the courses are only halfway on dirt roads:

- Paved roads: 4.0 km

- Dirt roads: 26.0 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

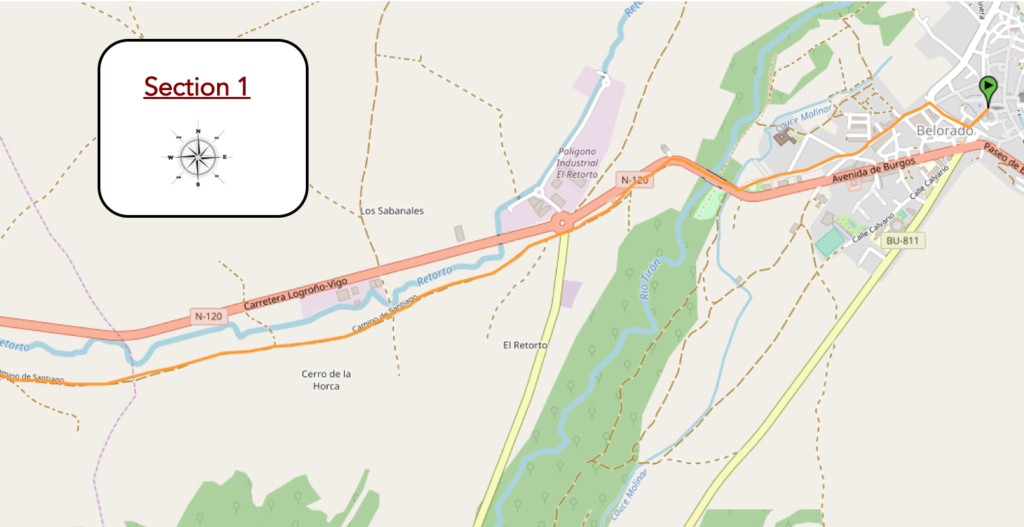

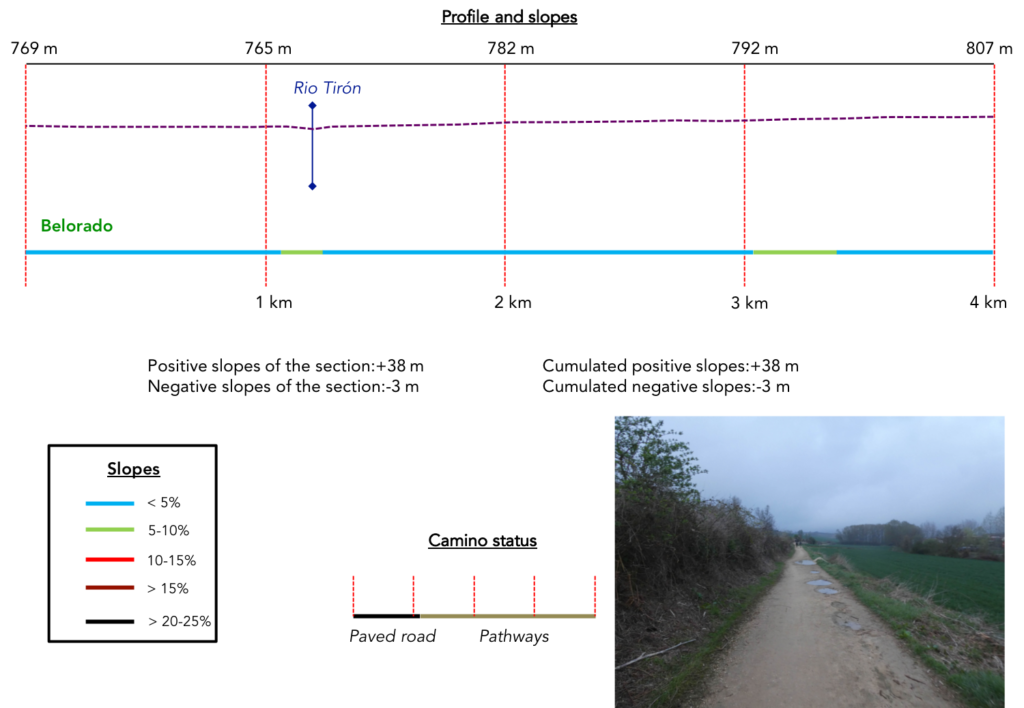

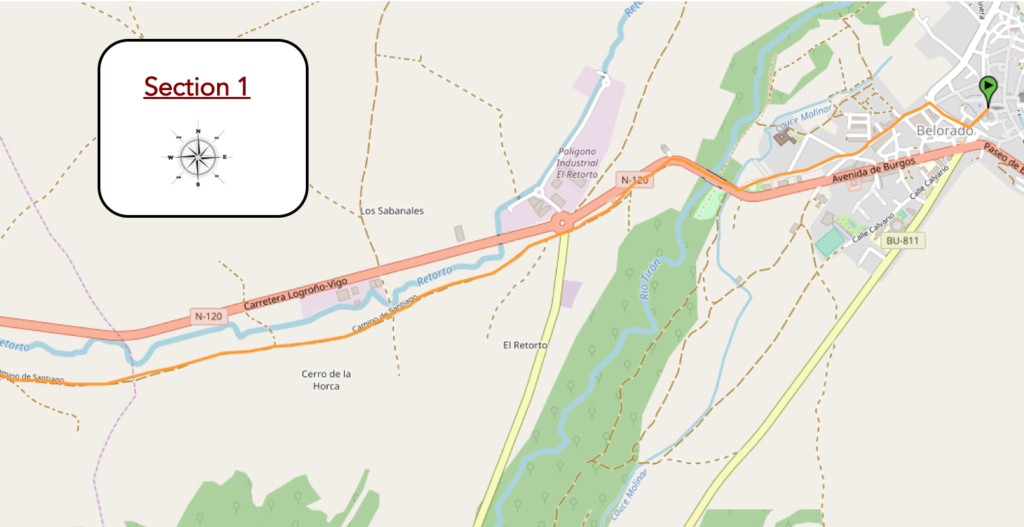

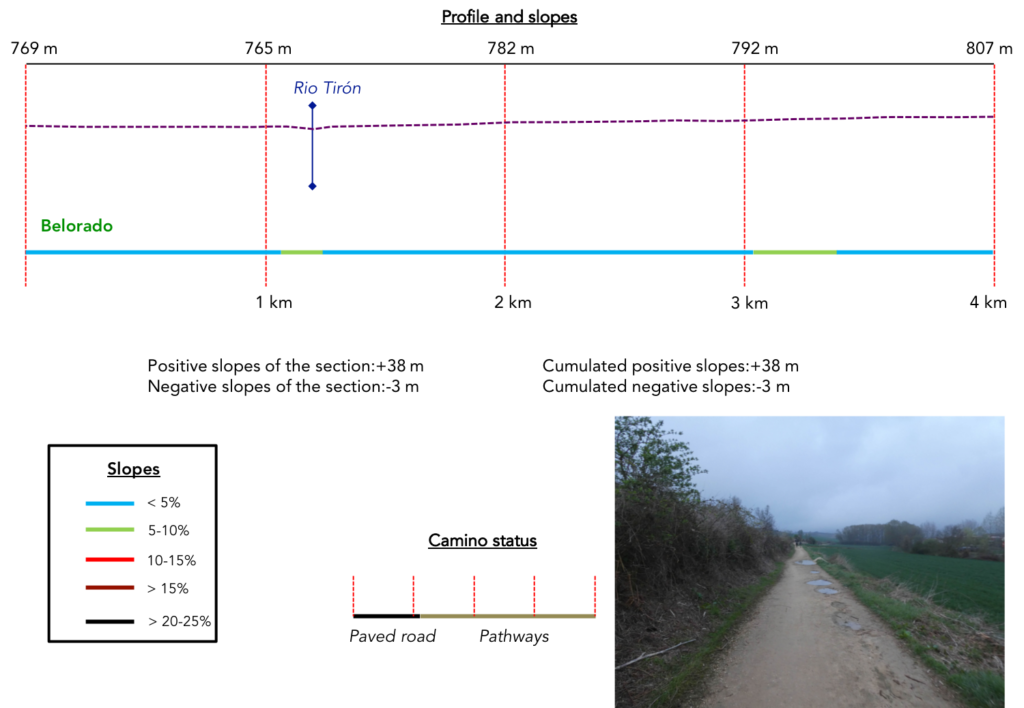

Section 1: A gradual return to the Meseta.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The weather forecast was wrong. Today, it does not rain on the region. So, pilgrims got up earlier than usual from their bunks. You never know, the rain can come back. The Plaza Mayor is deserted. Not that much! The young people of the village have not yet gone to bed and roam the streets and the square in search of a piece of bread, or perhaps a last glass of alcohol. |

|

|

| Do not imagine that youth is shameless here, but we have the feeling, to see the number, that all the youth was out. Yesterday was Saturday night. But the young people pay no attention to the pilgrims who leave the village in the still dark alleyways. They see them scrolling every day. |

|

|

| The Camino then follows the suburbs of Beldorado to find N-120 road again. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it crosses Rio Tiron on a bridge parallel to the road. The Spanish rivers are all wide, in water at this time. The bridge, the people here say, without proof, was made by Juan de Ortega with which Santo Domingo made many pilgrimages towards Santiago. Of course, the bridge has since been transformed. |

|

|

| A pathway follows the N-120 road for a few hectometers, before crossing another local road. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway deviates from the N-120 road, flattens along the hedges. |

|

|

| On your right, under the black poplars, flows the discreet Retorto stream. Here, water retention is common. When you see poplars, there is often a river. It’s curious, but the Spaniards apparently do not always favor corn in humid regions. |

|

|

| No, you did not take the wrong track. The number 1 European track to Portugal always accompanies you. |

|

|

| Further on, in the fields of cereals, the pathway gradually approaches the village of Tosantos. |

|

|

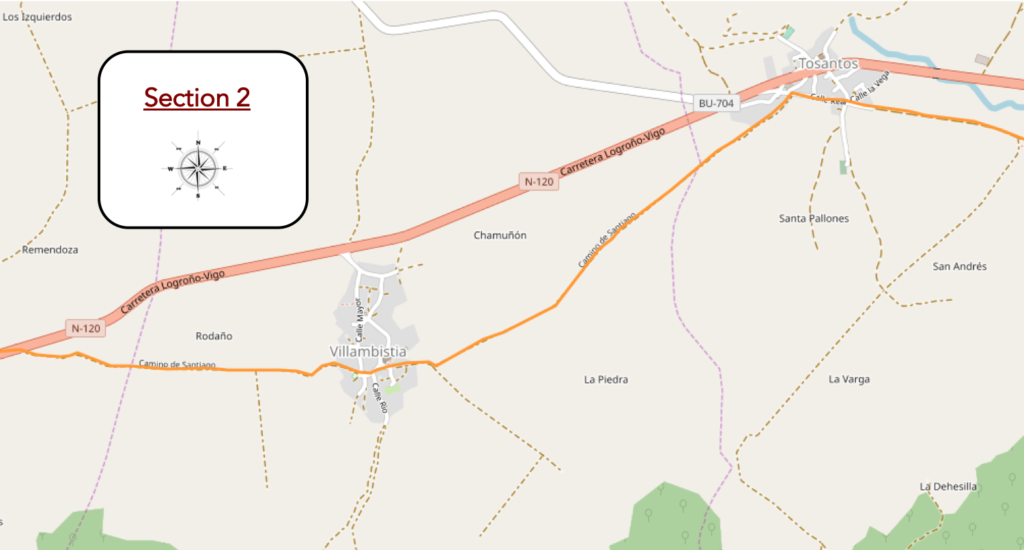

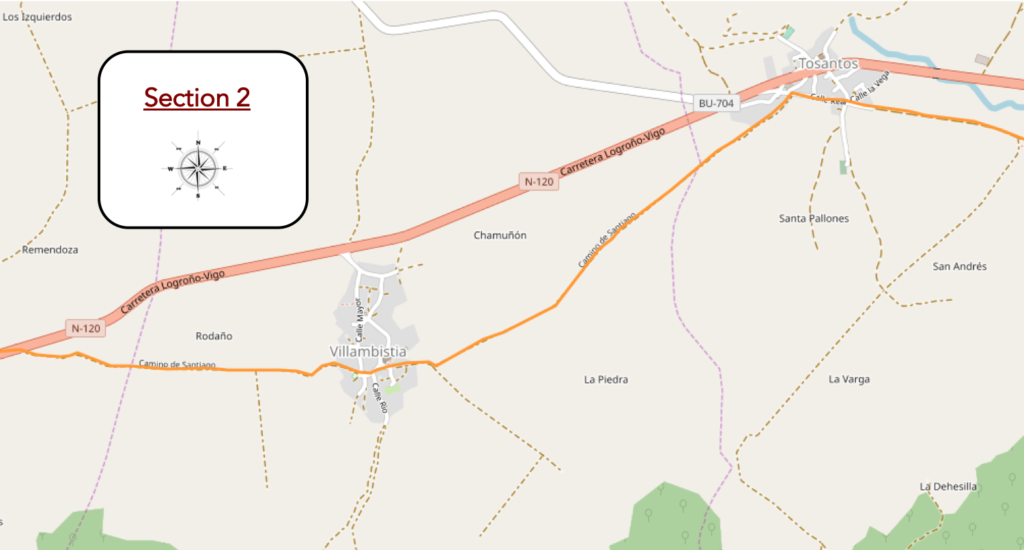

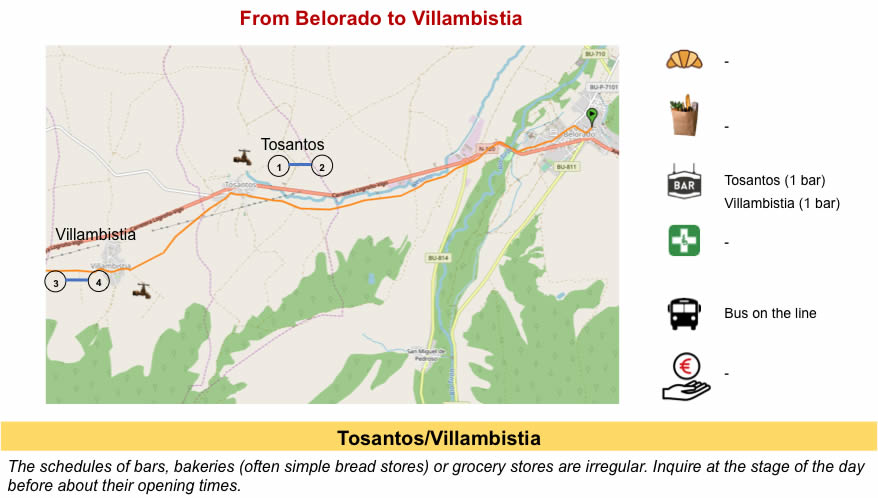

Section 2: From one small village to another.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| No doubt no pilgrim will stop this morning at the picnic place… |

|

|

| …because the village is close. |

|

|

| These village inns are the heart of the matter on the track. You can sleep, eat, drink, but they often serve as a grocery store, because it must be said, grocery stores are often missing on the way. But no one dies of hunger or thirst. |

|

|

| In the Middle Ages there was here a hospital for pilgrims. A little further from the village, there is a hermitage dug into the rock. No indication to go there. In any case, the pilgrims will go straight to the exit of the village. |

|

|

| On leaving the village, the pathway heads to a hangar where the tractors must be stored, which will not be leaving this year. |

|

|

| In those sections where no natural obstacle comes to disturb the space, the monotony and the uniformity of the places, you will often have the feeling of being very so close to the goal. But, you do not really move forward. For you, the next village is still as far away. |

|

|

Here, in a region where maize must also have its rights, you can see little hills ahead, and the village of Villambista is not far away. You already see the church.

San Eteban Church, on the hill overlooking the village, is a massive church of the XVIIth century. Such a large church for such a small village, the Spaniards did not refuse anything in the past.

| There were two hospitals here for the pilgrims. In the center of the village stands the disused St Roch Chapel, the patron saint of pilgrims. Next to it stands the pilgrim’s fountain. |

|

|

| Beyond the village, a wide sandy dirt road, it looks like a highway, leaves in the cereals, along the hedges. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway slopes down to a picnic area under the black poplars. The Koreans may have gone before you to do their daily group picture. |

|

|

| Then, the pathway joins and crosses N-120 road. |

|

|

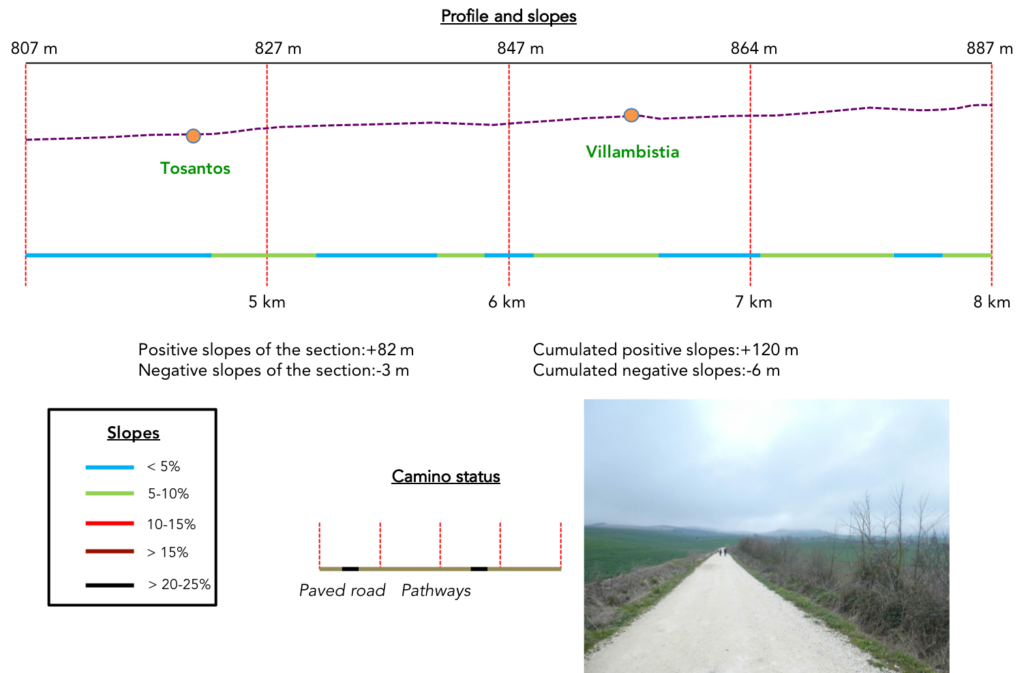

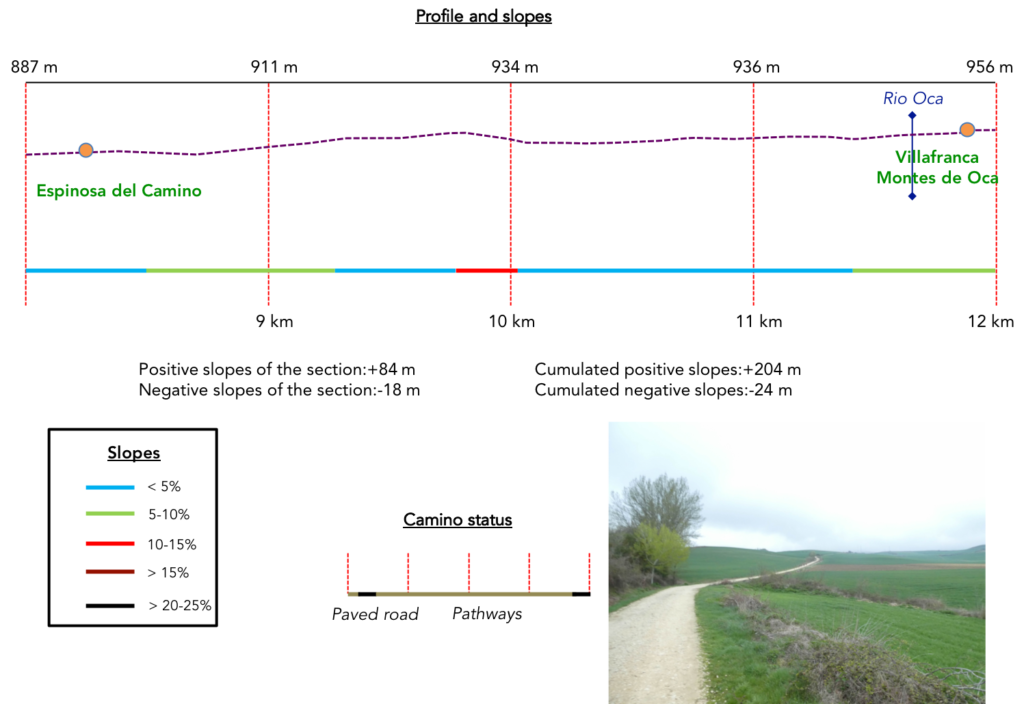

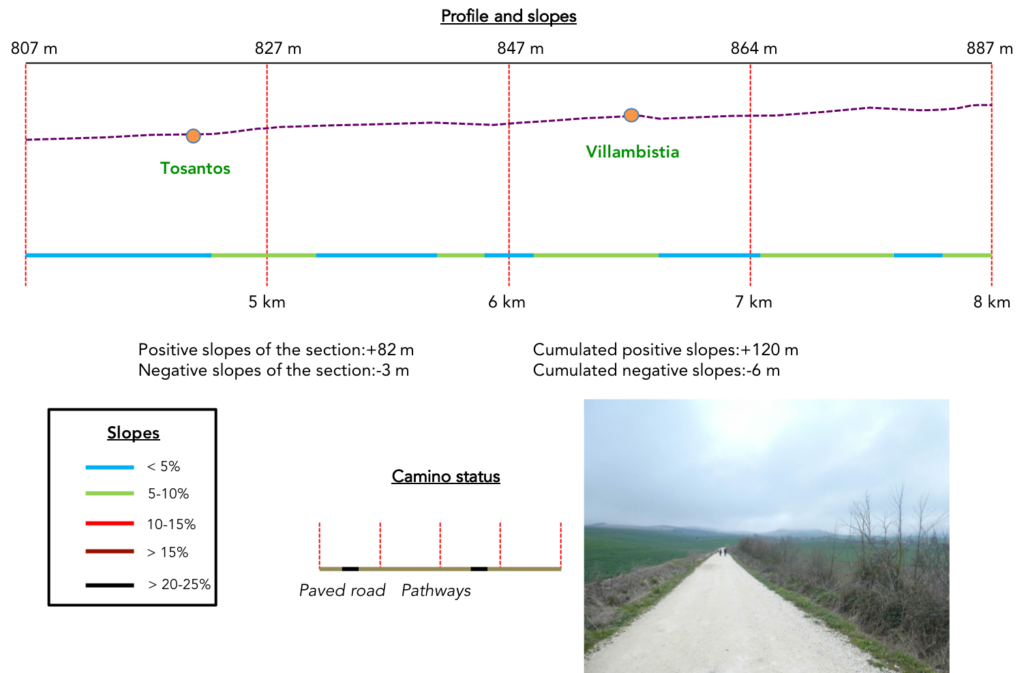

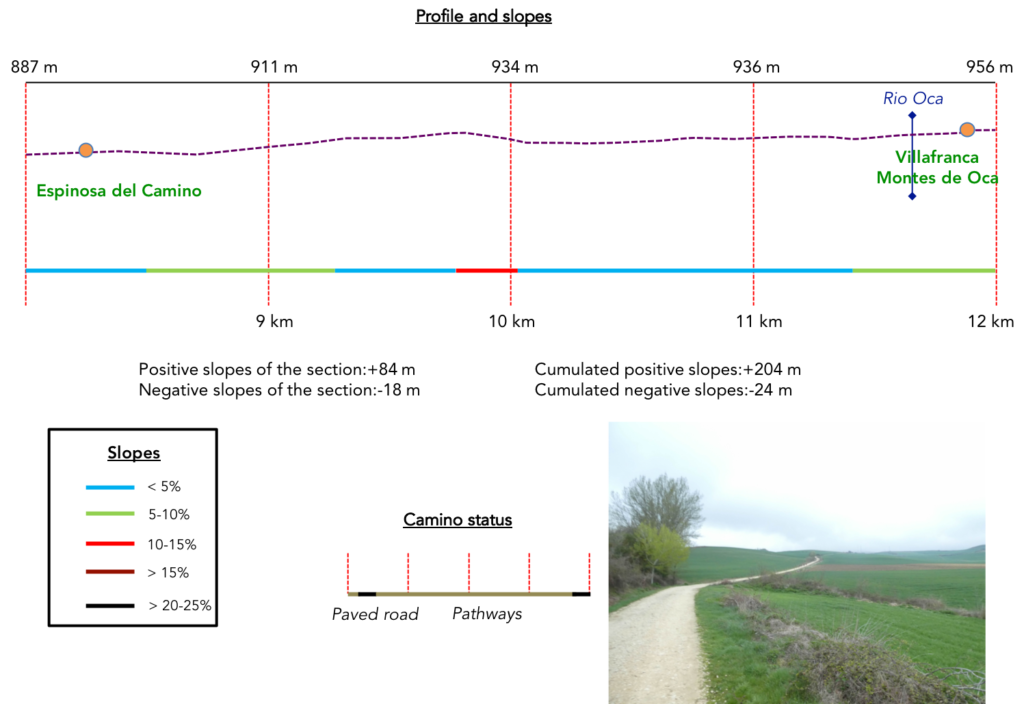

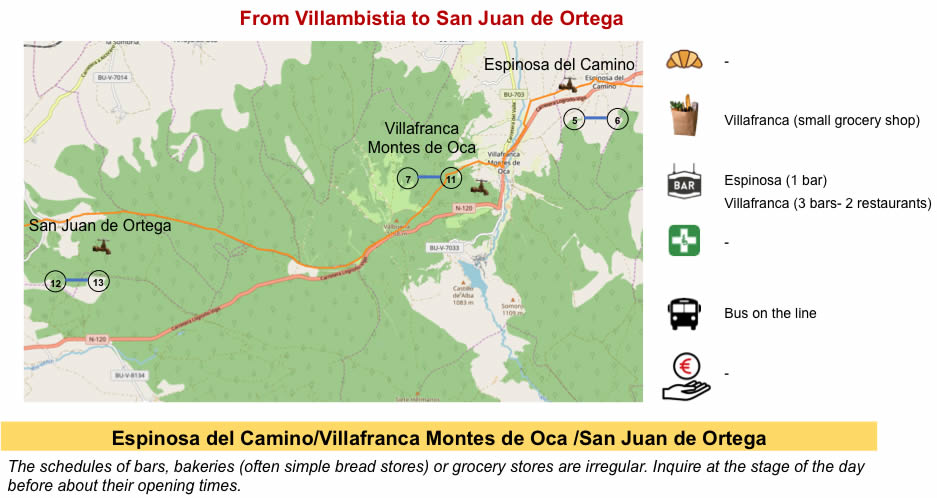

Section 3: From the Meseta to Oca mountains.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: some light slopes.

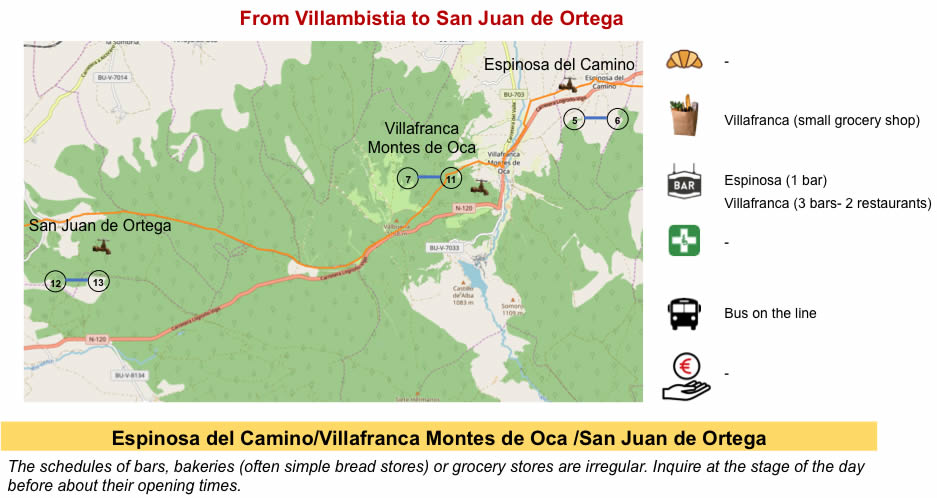

| As soon as you cross the national road, the Camino arrives at Espinosa del Camino. |

|

|

| The villages seem to be poor in the region. Here, the few stone houses sit next to fairly new houses that are not expected to last for centuries. But some homes where the cob is still in use are not lacking in charm. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, a long clay snake opens in front of you which climbs gently in the fields towards a small hill. It is often in these moments that you see the rows of pilgrims who fly away like little flies in the distance. |

|

|

| Sometimes the pathway is a little stonier. Not a tree here again, only small bushes along withered hedges. They have deloused the country to the bone. One wonders again in which universe the pilgrims of the Middle Ages traveled. No doubt there were trees. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, you can see the village of Villafranca nestled under Oca Mounts that disappear in the clouds and fog. |

|

|

As you descend the hill, the pathway heads close to what looks like a pile of stones. You approach it. No, it is not a refuge for wolves or for pilgrims. These are the miserable ruins of the ancient monastery of San Felix de Oca, which dates back to the IXth century. San Felices, or Felix the Hermit, lived between the IVth and Vth centuries. The peasant would have eliminated this pile of stones to let his tractor run, but it is here that Count Diego de Castille, one of the founders of Burgos, was buried. Pilgrims pass through without paying any attention to the greatness of Spanish history.

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway, almost sand, flattens towards the village. |

|

|

| You’ll quickly find N-120 road again, that you follow for a few moments. |

|

|

| A small pathway then sneaks down under the black poplars to cross Rio of Oca. |

|

|

|

|

| The pathway arrives at the village. The latter seems a little larger than the previous ones, but it only has a hundred inhabitants. However, it has a long history. Villafranca Montes de Oca welcomed pilgrims from the IXth century. It is one of many villages along the Camino which became home to the Franks arriving as pilgrims and remaining in the country as craftsmen, thus giving these villages their familiar appellation.

Villafranca Montes de Oca is the ancient Auca of the Romans. Its first bishop would have been named by St Jacques himself. It was here that, at the beginning of the XIIth century, a miracle attributed to St James took place, known as the sixteenth miracle of the saint in the Codex Calixtinus. A Frenchman, who was unable to have children, set off on the Camino de Santiago to curry favor with the apostle. In Santiago, he prayed and begged the saint to grant him a child. Back in France, he found his wife and she gave birth to a son who was called Jacques. When the child was fifteen, they all left for Santiago to thank the saint. But arrived in the mountains of Oca, the teenager fell ill and died. The mother implored the saint to return her child to her. So, the teenager got up and the family continued their journey to Santiago.

The village is located at the foot of the Montes de Oca, once a wild and uninhabited area and known for bandits who roamed its slopes to hunt pilgrims. In the XIVth century there was the pilgrim hospital of San Antón Abad here, which has been restored as a hostel. San Antón Abad (Saint Anthony the Abbot, aka Anthony the Great) was a Christian saint from Egypt, the first known ascetic to travel to the desert in the second century, known as the father of the hermit movement. |

|

|

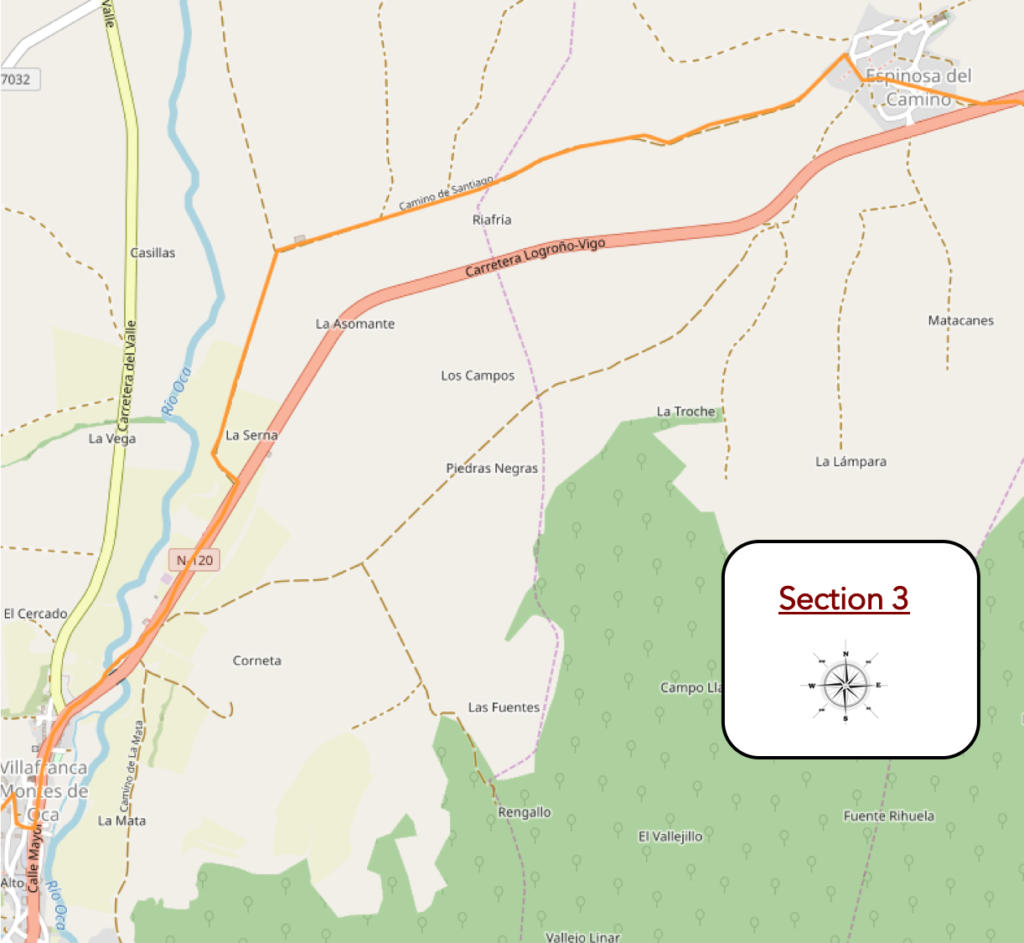

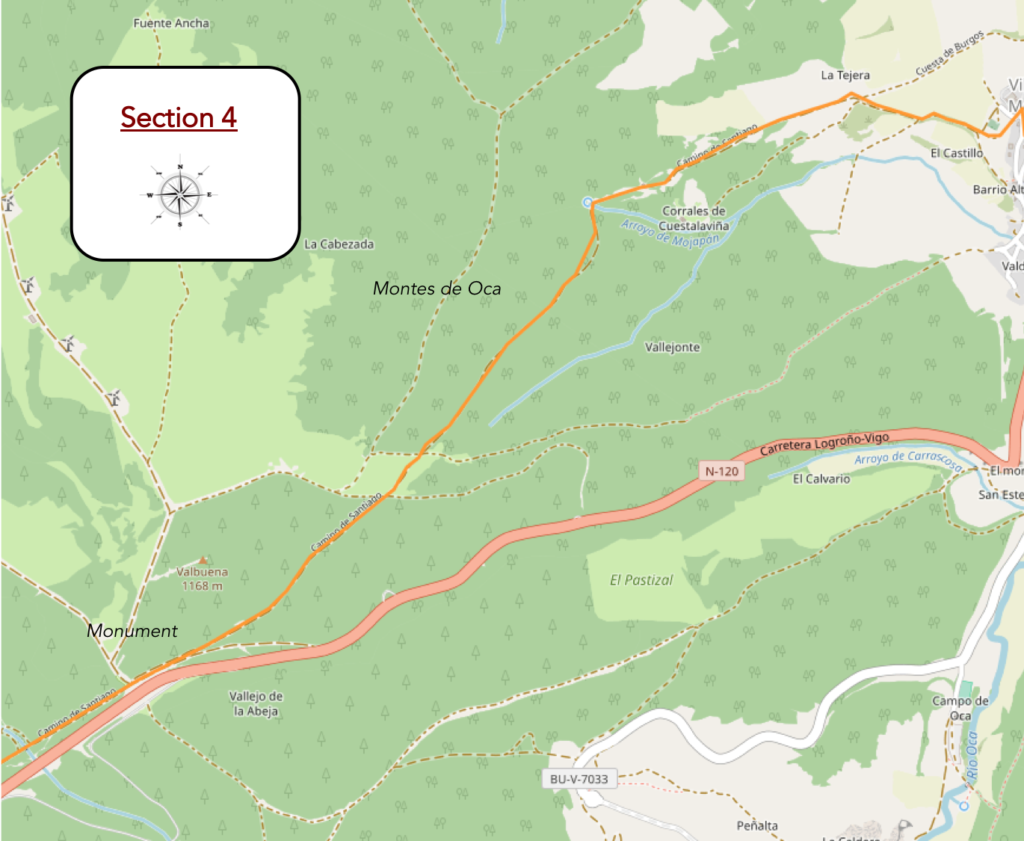

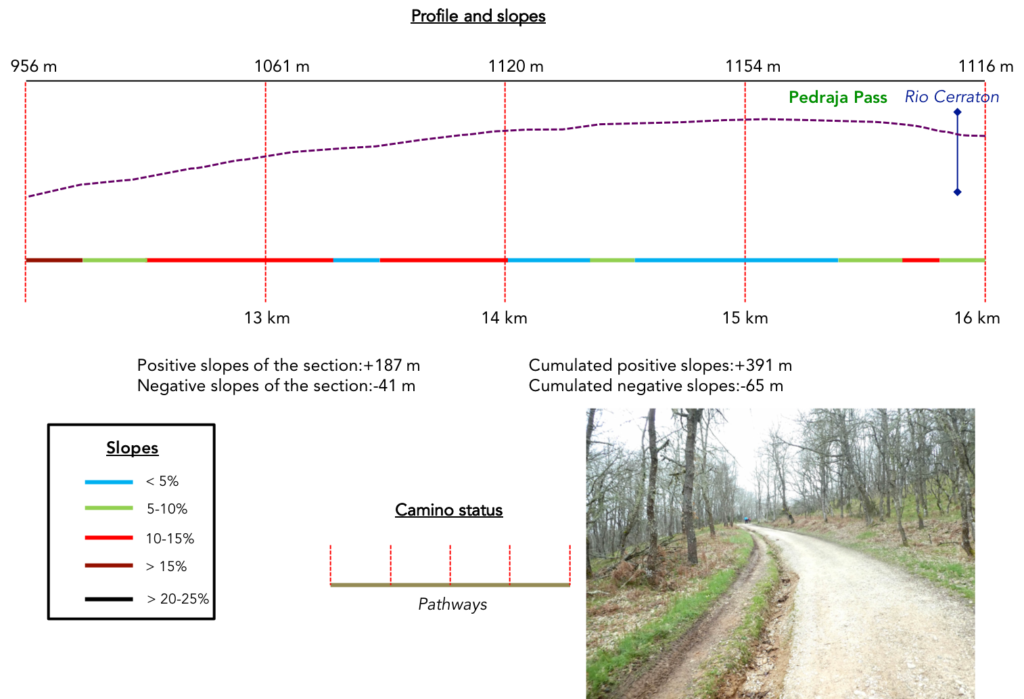

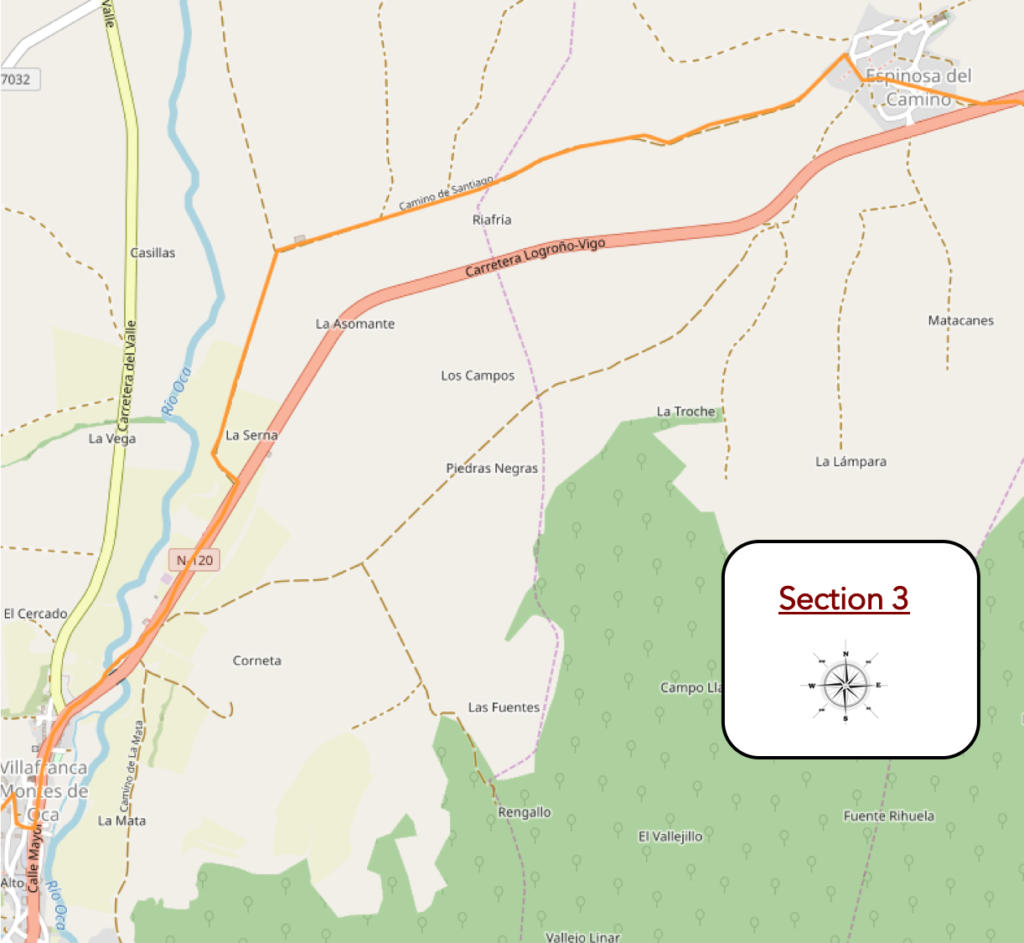

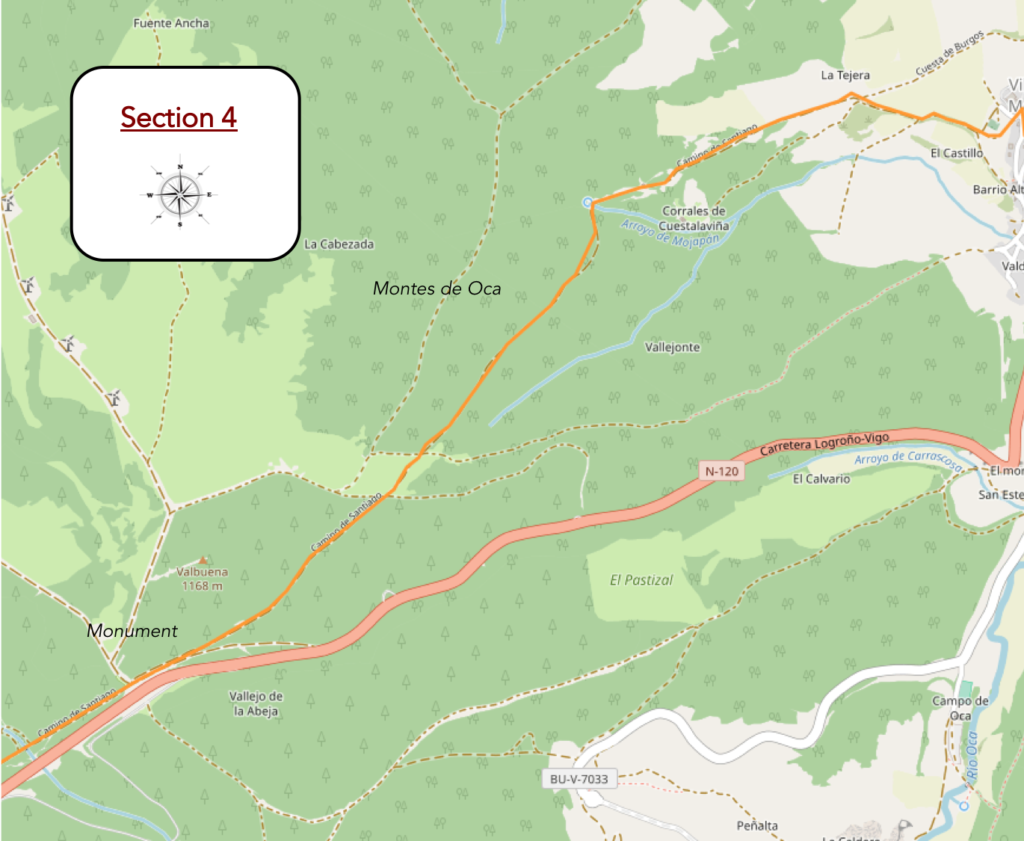

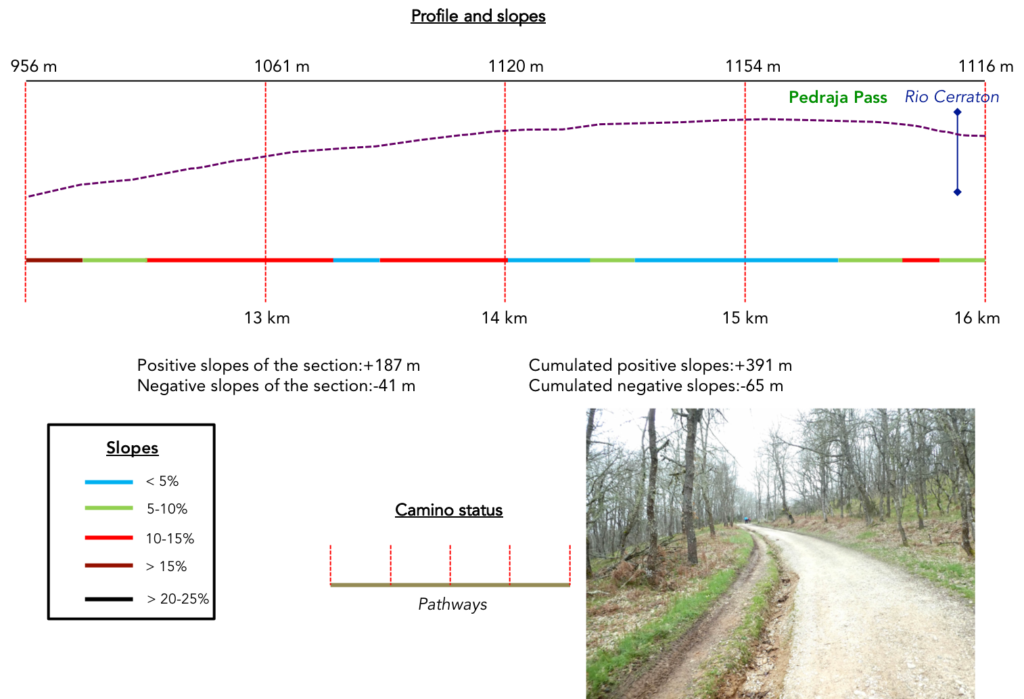

Section 4: In the forests of Montes de Oca to Pedraja Pass.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: the toughest course of the day, but with slopes rarely exceeding 15%.

| As soon as you leave the village, the pathway heads towards Montes de Oca. The slope is quite steep at first, at almost 20%, in bushes and weeds. The cyclists come down from their machine, to get an idea of the slope. |

|

|

| Cyclists sweat, but TGVs with two legs get away. Always, under the same circumstances. The steeper it gets, the more adrenaline rises. “It’s good for cardio”, they say. Yes, but for endorphins too. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway becomes more generous, decreasing its inclination, in the ocher ground, under the oaks, in the middle of the brooms and small conifers. |

|

|

| Further up, beyond a picnic spot, the pathway then regains altitude, with slopes close to 15%. To reach the high plateau, there is still nearly 200 meters of elevation over 3 kilometers. |

|

|

| The pathway then crosses a dense forest of oaks. It is the first time that we have seen so many oak trees in Spain. The ones we have encountered so far were holm oaks, which the Spaniards call encinas. These are real oaks, which the Spaniards call robles. These stunted trees look more like downy oaks than sessile or pedunculate oaks. But, in northern Spain, there are more than a dozen species of oaks. |

|

|

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway leads to the summit of the climb in a large moor, before sinking into the pine forest. At all times, the forests of Oca Montes have been feared. In the famous Codex Pilgrim Guide, it was “the ultimate test between the wild Navarre and the welcoming Castile”. It was only crossed during the day. It was said in the XVIIIth century that an Italian pilgrim was lost and that it survived only thanks to some miserable mushrooms found in the woods. And the wolves in this case? If you ask people in Villafranca, they will tell you that they have seen some and that it is better to avoid taking the road at night. Phew! |

|

|

| A real dirt highway, sometimes ocher sometimes beige, leaves in the big forest. You may scrutinize behind the trees. No wolf, no highwayman, disturbs the harmony of the trees. And then, you feel reassured, there is the high-voltage line, and right next door, parallel, N-120 road. |

|

|

|

|

The pathway then reaches Pedraja Pass (Puerto de Pedraja), Here there is a stele. 1936, the date speaks for itself. Above the stela a dove, symbol of peace. There, at the end of the road, the Francoists shot and threw in the ditch 300 republicans, desirous of freedom. This mass grave was erected by the families of the missing. In Franco’s day, people came here scared to death in memory. Then, in 1976, at the death of Franco, the families began to progressively organize at All Saints’ Day a sort of pilgrimage, with a modest cross that was planted, but that the old Franco supporters tore off every year. Then times passed and Spain calmed down. So, families had this stele erected in 2011, which tells the sordid story.

Obviously, we cannot blame the pilgrims for passing here indifferent. It’s not their story, and no one has told them. But some deposit small pebbles on the edge of the stele, as they usually do for crosses, whatever their origin.

| Here, you are still more than 1’150 meters above sea level. Beyond the monument, the pathway plunges into the dale. Here, you’ll really feel like you are on a ski jumping hill, with the track sloping up to the other side for the landing. But, if it sounds dizzying, it is not. It’s just 15% slope, but it’s the space that looks amazing. |

|

|

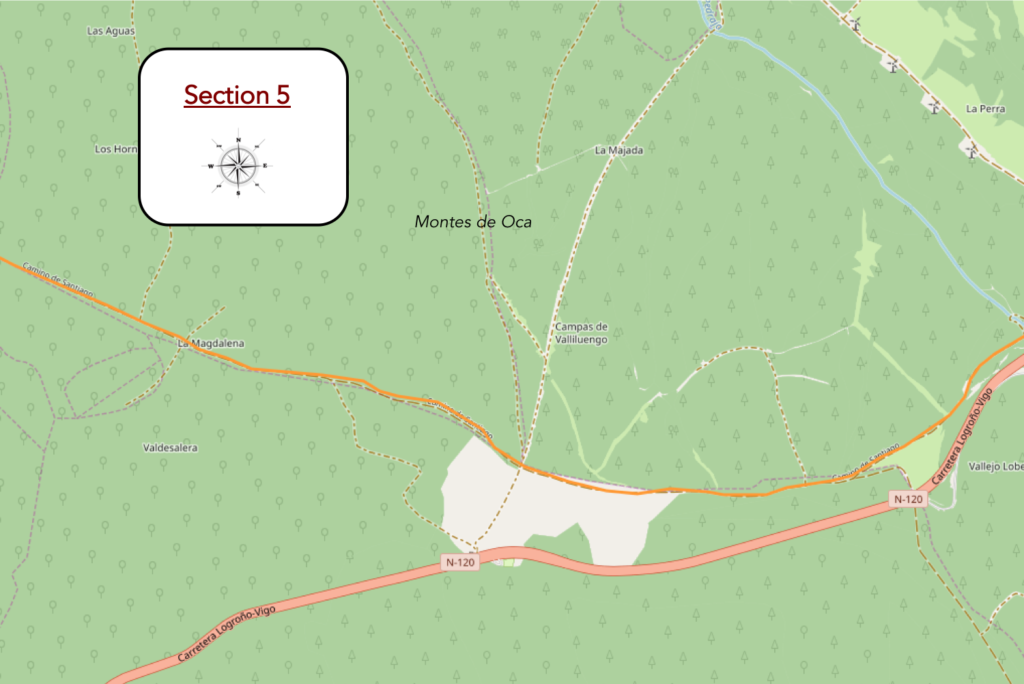

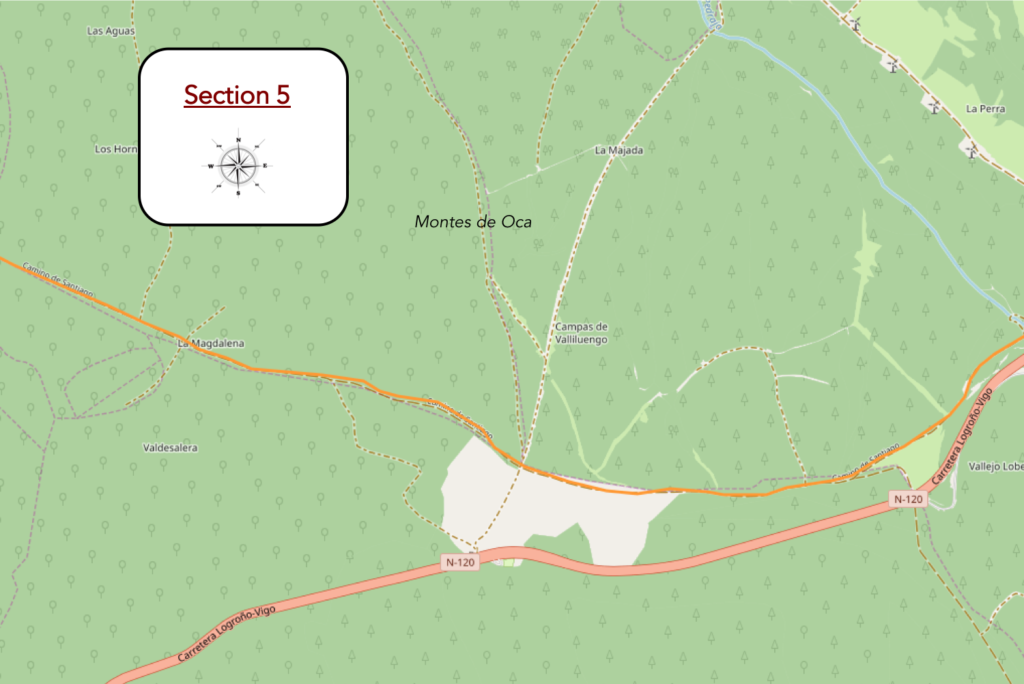

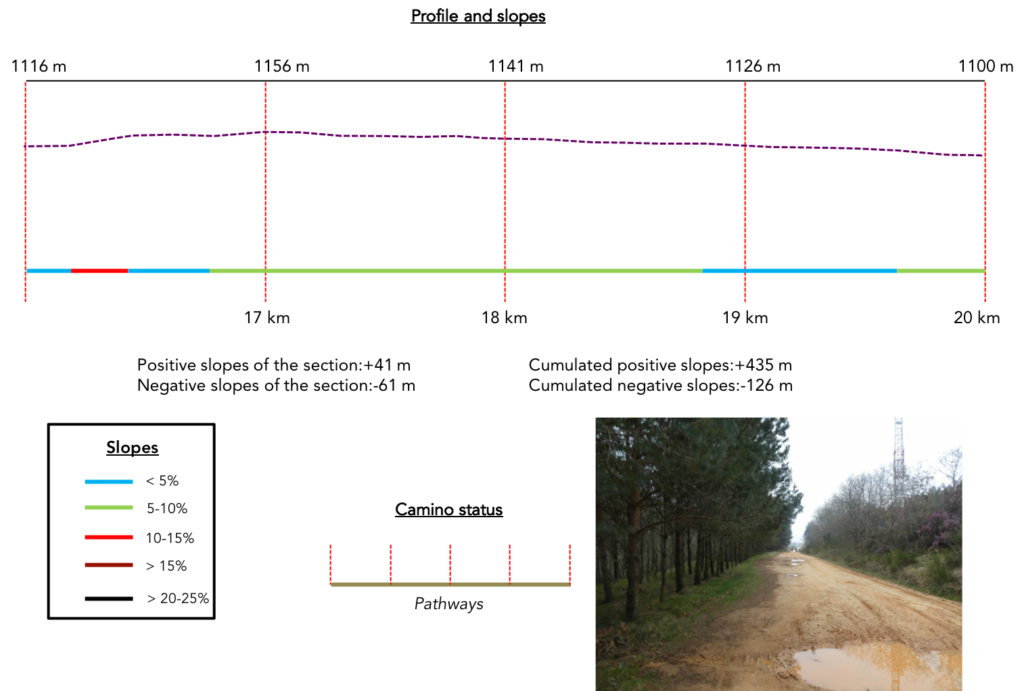

Section 5: Along forests that never end, just for fun.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| At the bottom of the springboard, the pathway crosses the small, bloodless Rio Cerraton on a wooden bridge. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream, the pathway climbs up for almost a kilometer, sometimes with a steeper slope, in the middle of the oaks and beeches which have reappeared among the pines. Sometimes the pathway is a little stonier in the bushes and the broom. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway finds a high plateau. Many pilgrims catch their breath here. |

|

|

| But why has this region been dubbed “Montes de Oca” (Mountains of the Goose)? The symbolism of the goose is as varied as it is diverse, combining prudence, cunning, intelligence, but also female infidelity or the messaging of the gods. In the Middle Ages, the crow’s feet was a sign worn by the cagots, like later the Jewish star by the Jews. The cagots, carpenters for the most part, lepers living apart, wore this sign. They were present in many places, in the French and Spanish Pyrenees. Apparently, the origin of the word is not to be found in this register. So, people went to look for Muslims who used to live here. Among them, there were Persians who traded in geese. Perhaps, but there is another even more obvious reason. In Roman times, the village was called Auca. “Auca, Oca”, the connection is quickly made, right?

But whether or not there were geese here, nothing adds to this magnificent plateau that the pathway joins at the top of the climb. |

|

|

Spain is often made of freedom, large spaces that make you dizzy, which turn minds to travelers. The wild nature takes place under the gaze and the soul is immersed in the deep depths of the horizon.

| And here is again our nice Korean lady, who is advancing at her own pace on the track. Here, today, she has left her earphones on her ears. Is it to better appreciate the silence that reigns here? She is walking slowly, of course, but we left at the same time together from St Jean-Pied-de-Port. |

|

|

| At the turn of the track, and there is not a lot of detours, the dirt road arrives on an unlikely site. |

|

|

No indication is given on this festival of primitive open-air art, on this exuberance of totems distributed in nature. Here, no entrance ticket, the course is free.

| Of course, the charm and the unusual place does not prevent answering his emails on the cell phone. Here, the network works, in the middle of the wilderness. Viva Spain! |

|

|

| And the way to leave tirelessly, in the same setting of loneliness, under the pines and the oaks, with the pilgrims in front of you, or sometimes alone with the wolves. |

|

|

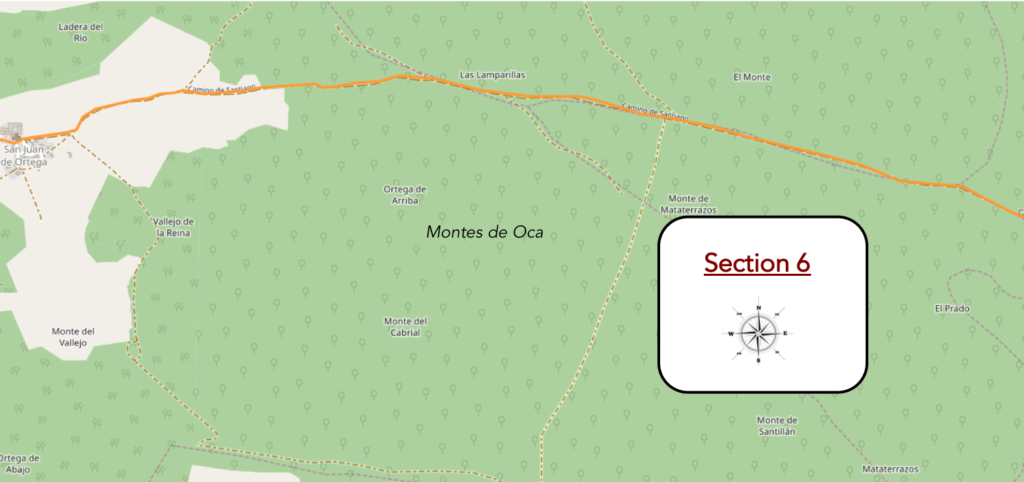

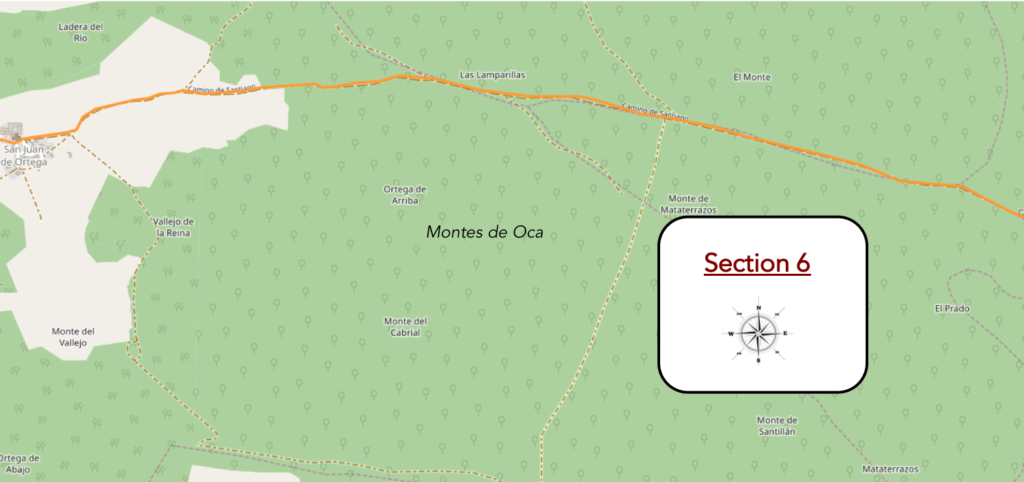

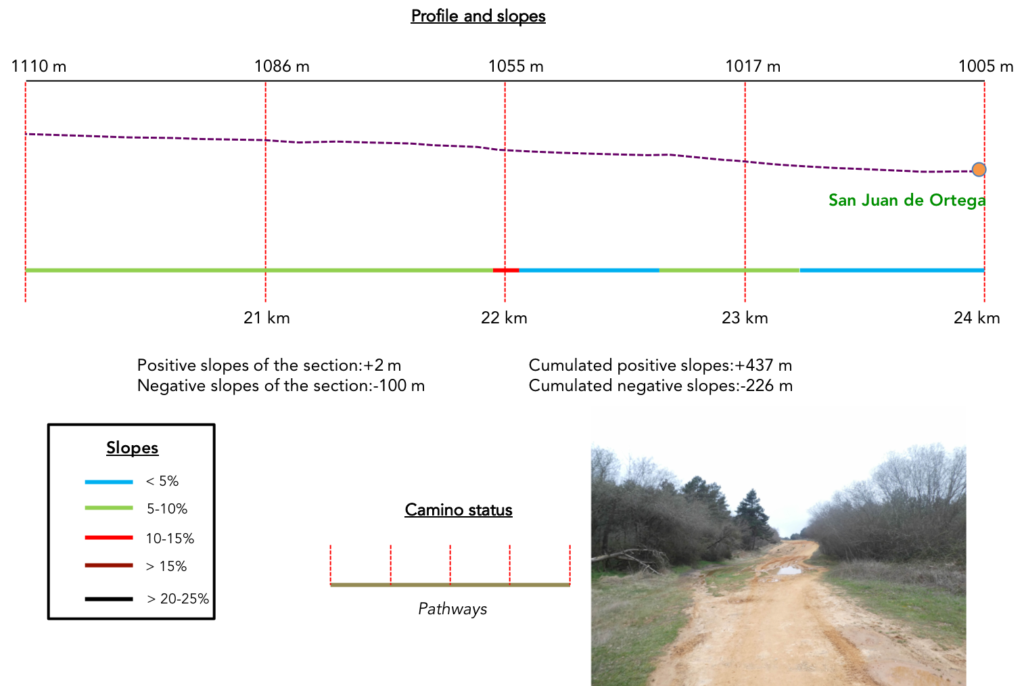

Section 6: Towards the haven of San Juan de Ortega.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| There is no landmark, no small cross road nor streams for miles, just this pathway that runs to infinity. |

|

|

| If you let the pilgrims slip past you, then the universe is yours. The pathway, which is getting wider and wider, will no doubt also seem longer and longer to you. For some, there is nothing to do but move forward, with an empty mind, without thinking of anything or not much, in the middle of the pines. For others, it’s the time for interior monologue, stories that constantly come back to your mind, that you still wonder what you’ve come to look for so far. But, it is magnificent, out of time. |

|

|

| Winter is harsh here, in the snow and the wind. In the Middle Ages, probably the wolves were already rushing there. But it was not only the wild animals that showed the fangs, the highwaymen too. A saying used to say here: “Si quieres robar, véte a los Montes de Oca” (If you want to steal, go to Oca Mounts). |

|

|

| Who will dare to pretend that the forest is not majestic here, as big as Spain? |

|

|

| After a few kilometers of gentle monotony, you see the forest opening up, the clearings getting closer. |

|

|

| You walked nearly 12 kilometers in this forest without seeing a wolf. Now it’s time to get out. |

|

|

| From here you have San Juan de Ortega in front of you. |

|

|

| There are meager crops, even a few cattle on the outskirts of the village. |

|

|

San Juan de Ortega is above all a monastery more than a village.

| It is believed today that the construction of the church began shortly after the death of the saint in the early XIIIth century. Then in successive works, it was completed in the middle of the XVth century. The pediment of the main facade was added in the XVIIth century. The church has a Latin cross plan, with three naves, a transept, and at the bedside three apses, each forming a chapel. The church is a mixture of Romanesque and Gothic style, without great Baroque flourishes. The church is very bright and the barrel vaults are beautiful. A cloister (closed) is adjoining. |

|

|

The oldest and most noble building of the monastery is the Chapel of San Nicolás de Bari, also called “Chapel of the Saint”. As mentioned in the introduction to the stage, it alone sums up the story of the saint. The construction of the chapel was not easy in a universe populated by brigands. Here in the sepulcher are buried the relics of the saint. The style of the chapel is primarily Romanesque.

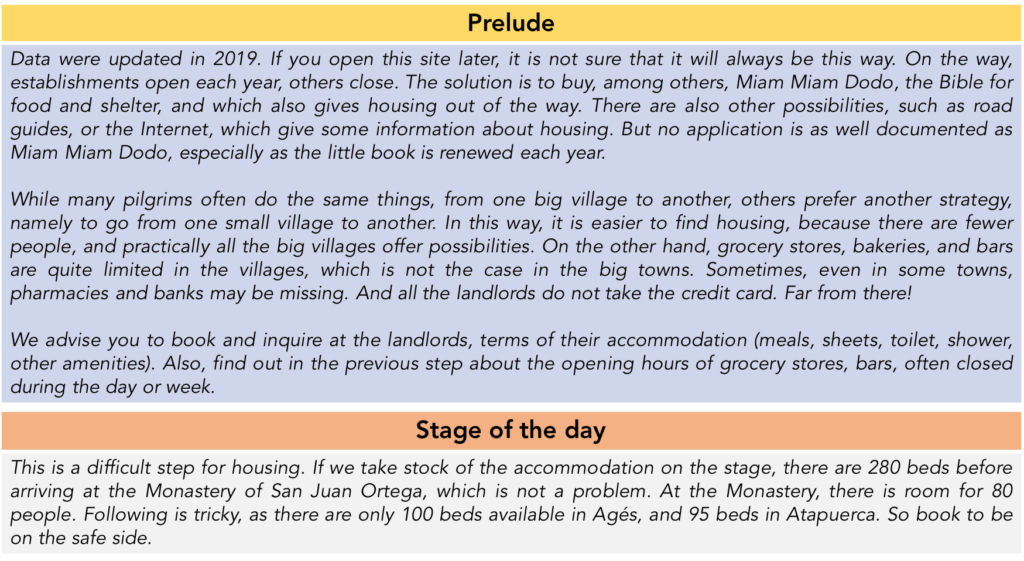

| The housing capacities here are limited. The village, especially the hospice of pilgrims forming part of the monastery, can accommodate only about seventy pilgrims. The others, who have not had a chance or who have not booked go further on the track, to Agués or Atapuerca. |

|

|

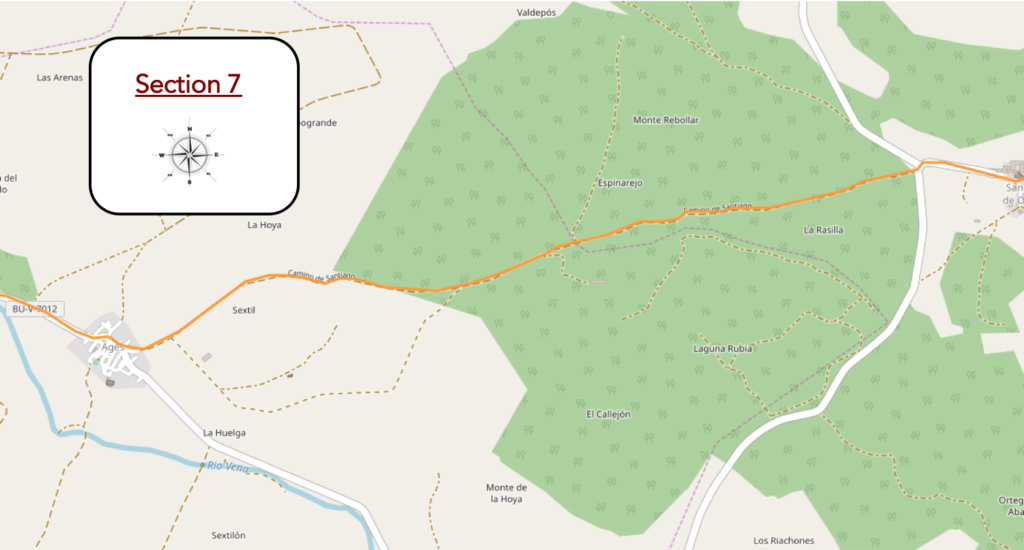

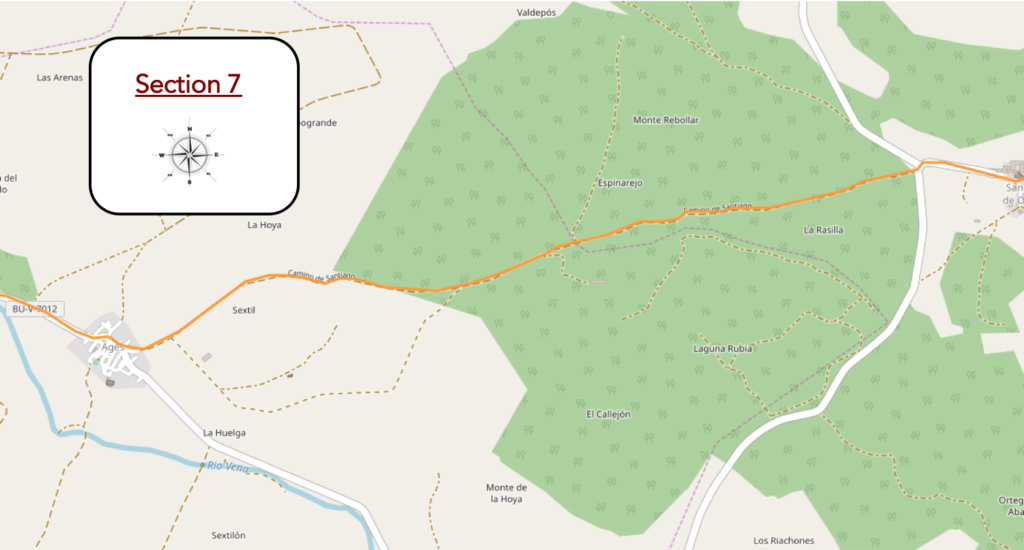

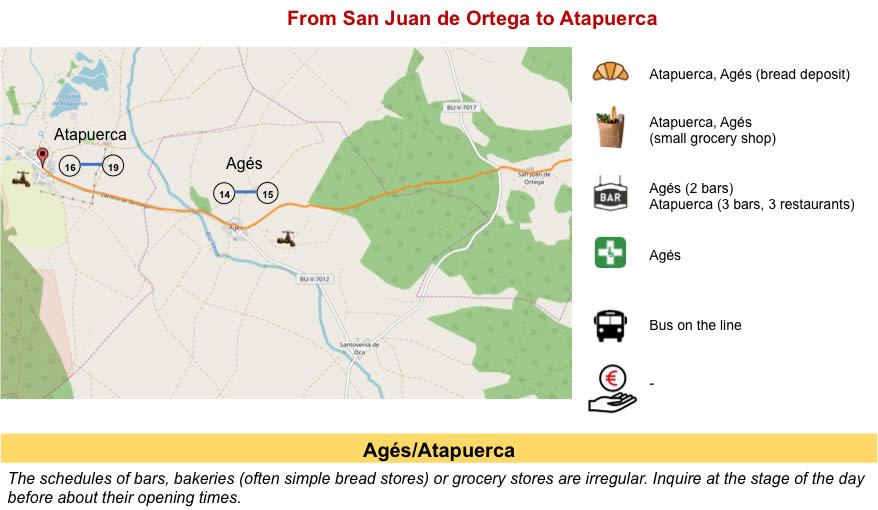

Section 7: Direction Agés, to find other accommodations.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| A paved road leaves the monastery to head towards the forest which is still that of Oca Montes. |

|

|

| The pathway is wide in the soft and relaxing pine forest. It is again and also the route taken by the European route N01 to Portugal. |

|

|

| Shortly after, there are containment barriers in the forest where pines and oaks line up on both sides of the road. We have not seen a single head of cattle for a week. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway then comes out gradually of the wood. |

|

|

| The space opens soon before you. In the meadows stand tall solitary oaks. You are here at 1’000 meters altitude and the trees have not yet taken their spring adornment. They are still in their state of marcescence, with their dead leaves attached to the bottom of the trees. |

|

|

| The pathway flattens in meadows to the end of the high plateau. |

|

|

| Further ahead, it slopes down to Agés in the plain. |

|

|

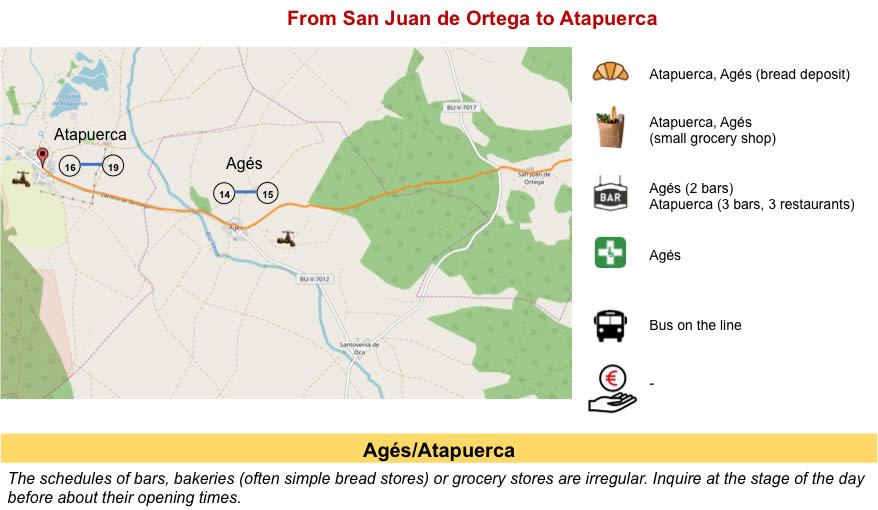

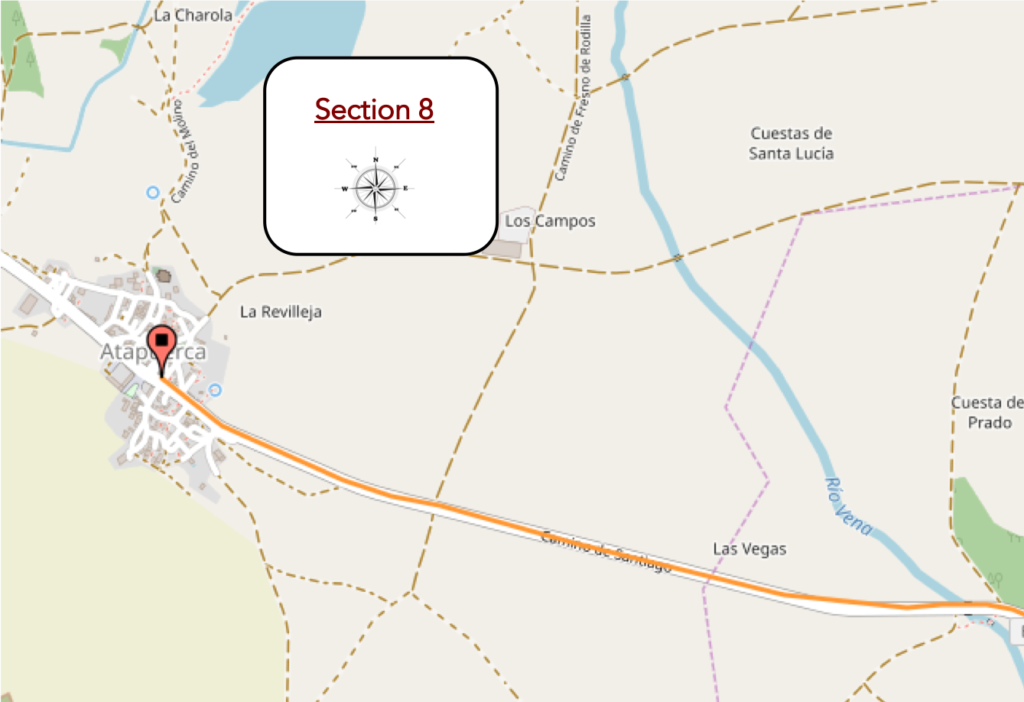

| Agés has its origins in the middle of the Xth century during the Reconquista. In the XIIth century, King Fernando VII, in his efforts to protect the pilgrims heading for Santiago, diverted the old road, and since then it has passed through Agés. Agés arouses interest among pilgrims not for aesthetic reasons, but for logistical reasons. Here, you find accommodation, if you could not do it in San Juan de Ortega. Some pilgrims even push as far as Atapuerca, two kilometers further. |

|

|

| The Camino then leaves the village and flattens into the meadows to visit a bridge over the Rio Vena. |

|

|

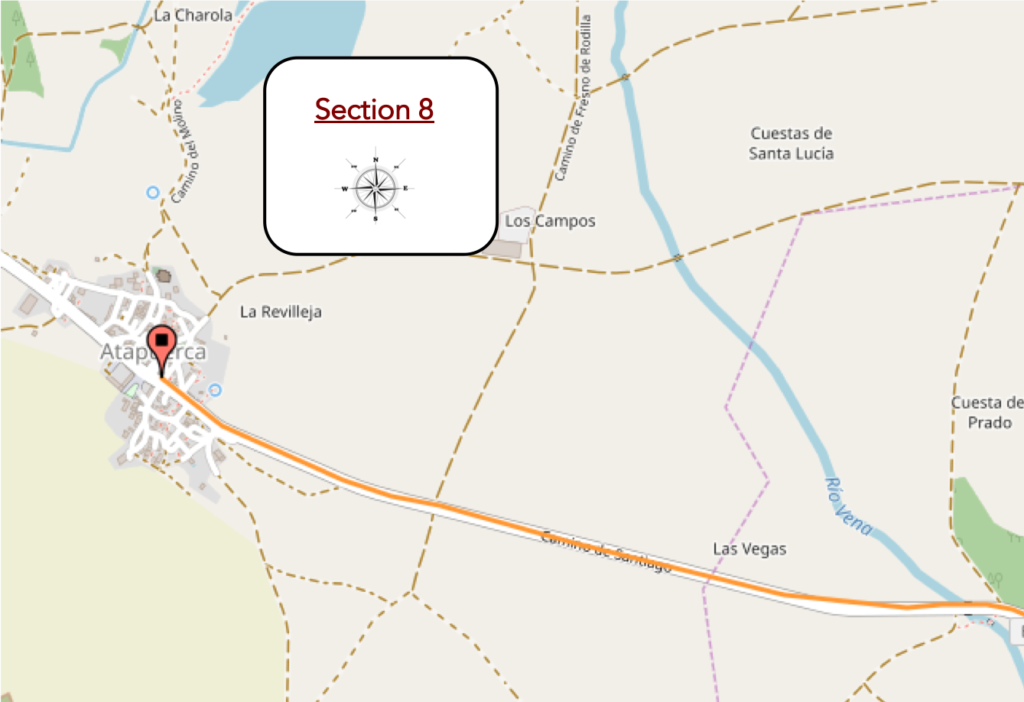

Section 8: In Atapuerca, among men of prehistory.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any dificulty.

| This bridge, we owe it to Juan de Ortega. When you look at these old stones, you are like in front of the stones of the Roman bridges, fascinated. Certainly, here the brook should not be difficult to cross. But it’s touching, full of old-fashioned charm to say that hundreds of millions of shoes have caressed these stones. |

|

|

| Alas, beyond the bridge, there is no small lane in the grass. It’s the paved road for two kilometers. Even black poplar bunches will not give you shade. |

|

|

| The road is gradually approaching a park of standing stones before the village. |

|

|

| This park with reconstructed standing stones is here to mention the great discoveries that take place here. |

|

|

Pilgrims will not today dig up the bones and mandibles of our ancestors in the mountain of Atapuerca. Palaeontology, like archeology, is only a matter of specialists, experts, people who know how to identify and date the “contents of garbage cans”. When you see the complexity of the site, you will understand that you cannot go for a search for a bone, especially as it is the knowledge of our origins. Endless trenches, the collection of clues, it’s like a huge crime scene. Then a lot of know-how, a little carbon-14 dating, a little nuclear magnetic resonance, a little of genetics and DNA, and voila. Here, there are three sites under study, with bones, some of which may be as old as a million years ago, when modern man separated from his Neanderthal cousin. So here lived proto-men. Other pits have already identified one of our cousins, the homo antecessor, an ancestor of the Neanderthal man, who dragged his sandals here, 500,000 years ago. The site is part of the World Heritage of Humanity since 2000. Of course!

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Atapuerca_map.jpg

| The road then arrives at the village, which is not classified to the heritage of humanity. There is nothing to do here, nor to see, otherwise San Martín Church at the top of the hill, built between the XVth and the XVIth century in Gothic and Renaissance style, closed of course. And in the evening, garlic soup, of course. |

|

|

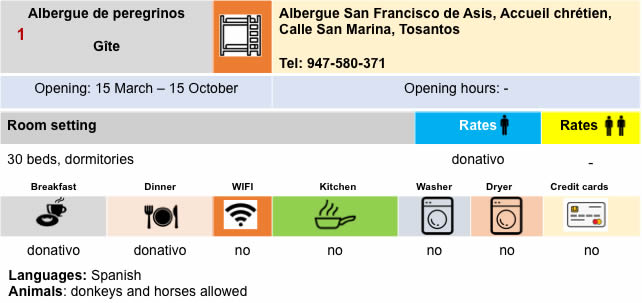

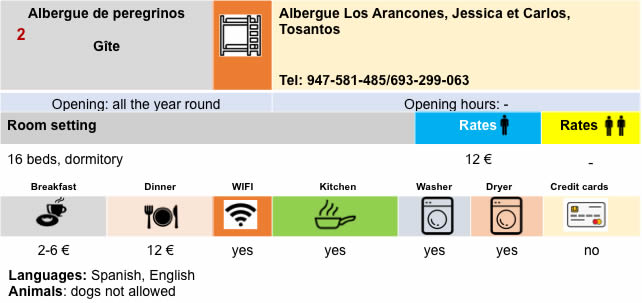

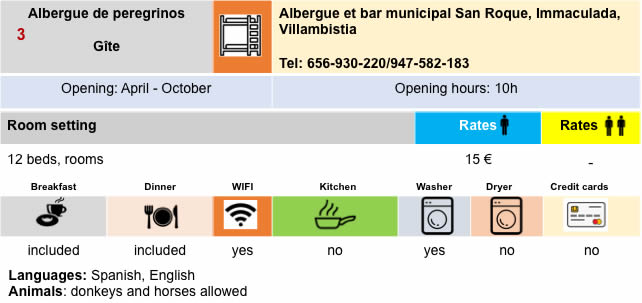

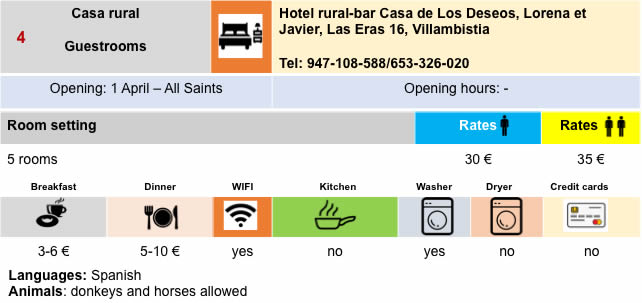

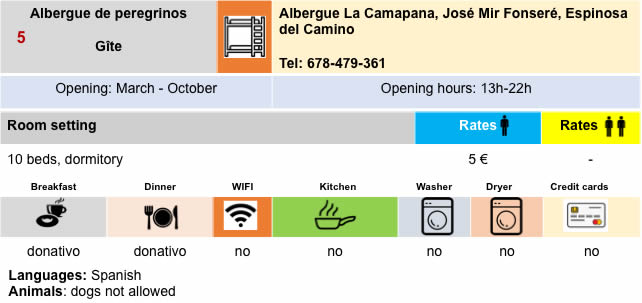

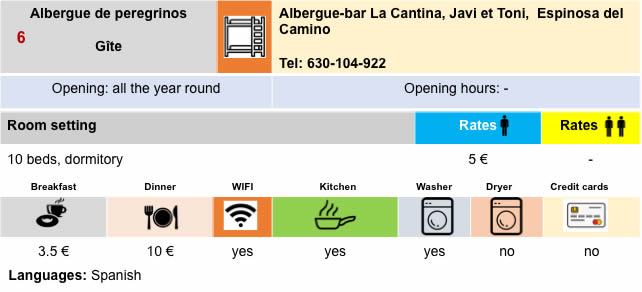

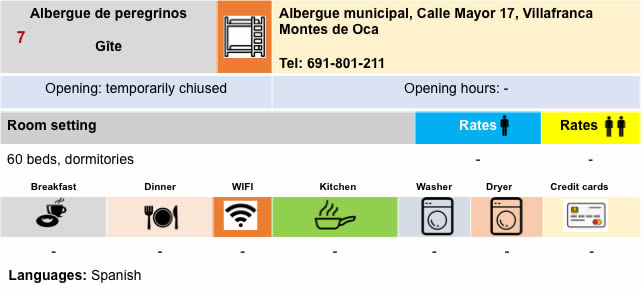

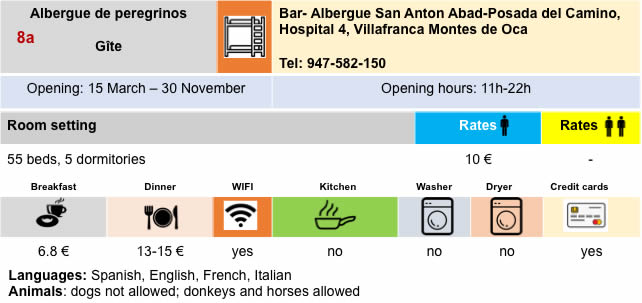

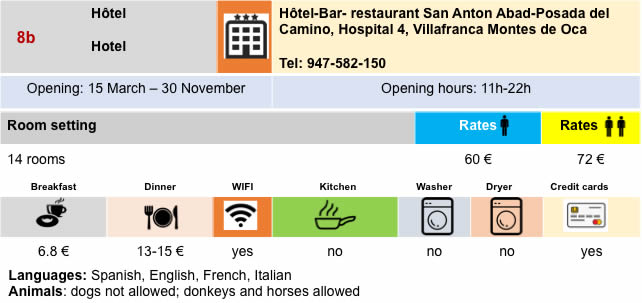

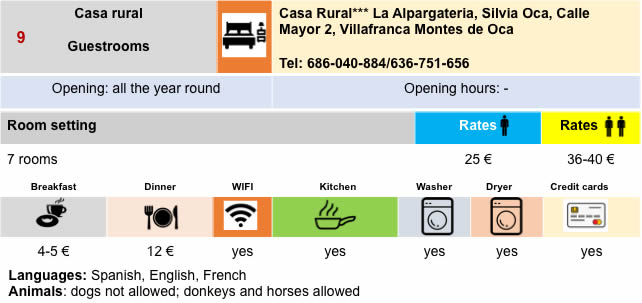

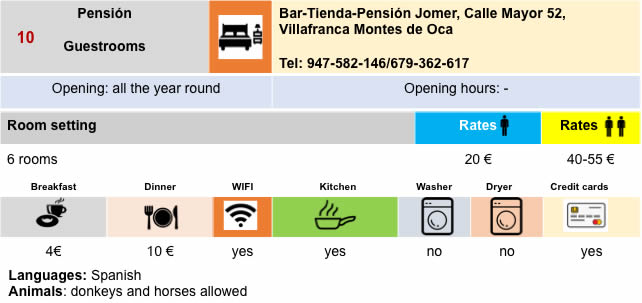

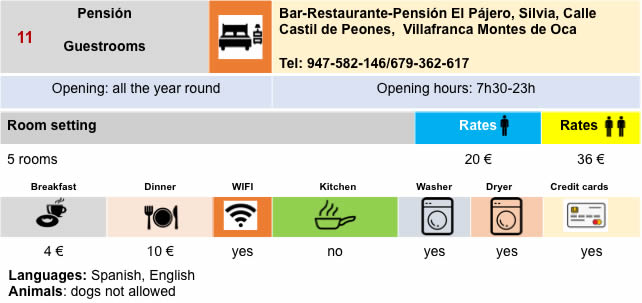

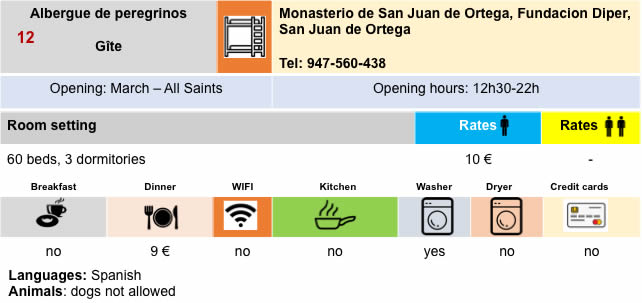

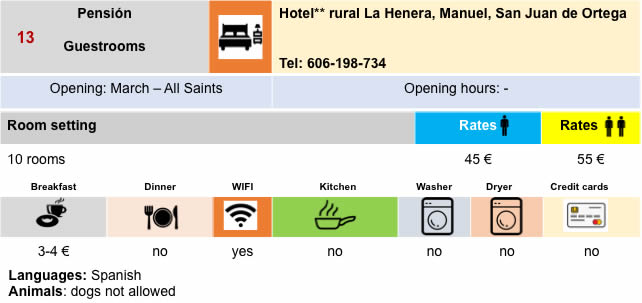

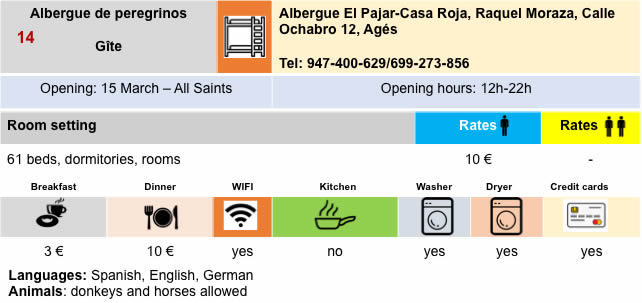

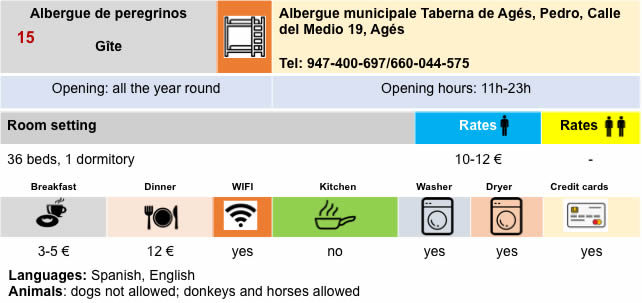

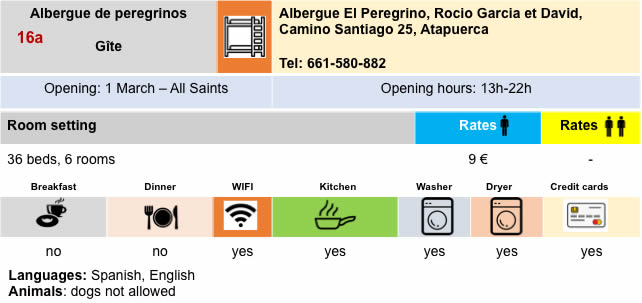

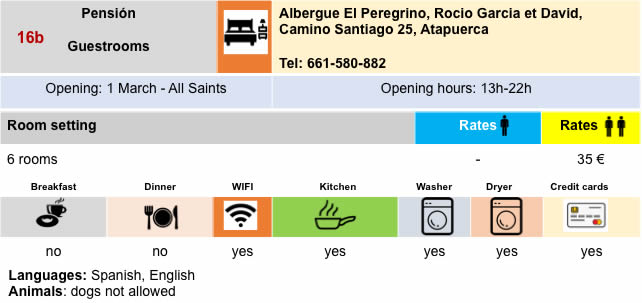

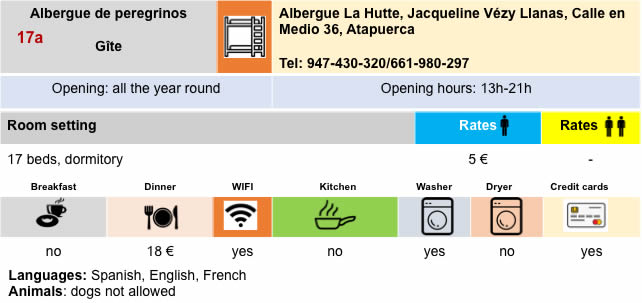

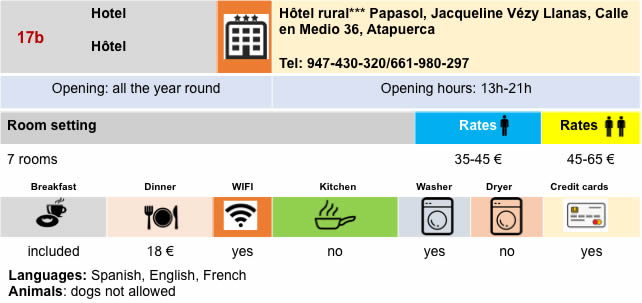

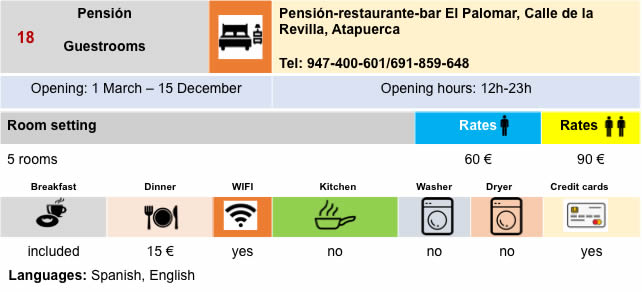

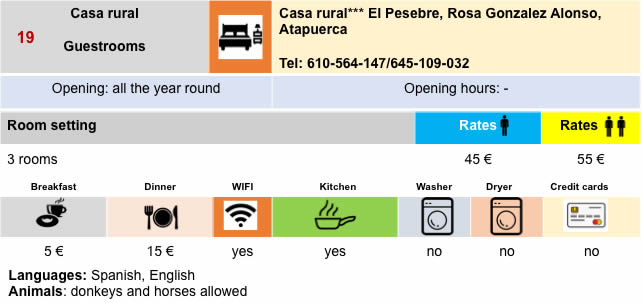

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 12: From Atapuerca to Burgos |

|

|

Back to menu |