A long descent to the plain which is deserved

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-el-acebo-a-ponferrada-par-le-camino-frances-117474748

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find soon a book on Amazon that deals with this course.

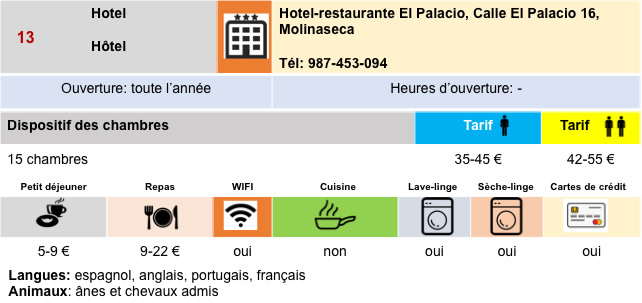

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

El Bierzo (O Bierzo in Galician) is a comarca, i.e. a traditional region or local administrative division of the province of León. Historically part of the Kingdom of León, and briefly (1821-1823) an independent province, with the new administrative division of Spain in 1833, the majority of the region became part of the Province of León, other parts forming part of Galicia. We will return later in this site to the complex history of Bierzo and its interaction with neighboring Galicia. El Bierzo has developed its own particularities as Galician and Leonese traditions blend under Castilian influence. The inhabitants of the region are called bercianos. Its capital is the city of Ponferrada. The other important town is Villafranca del Bierzo, the historic capital. You will get there the next day.

Ponferrada has existed since pre-Roman times, when the Asturs inhabited the area, a Hispano-Celtic Galician people. The Gallaeci were tribes that had settled in the northwest of Spain. They were conquered and assimilated by Emperor Augustus. The region then gained in importance and prosperity during the Roman occupation thanks to the gold mines of the region of El Bierzo, which was the largest mining center of the Roman Empire. The city is located in a fertile valley and in a rich mining district. In modern times, local deposits of tungsten were mined to supply the arms industry during World War I. After 1918, the coal deposits were exploited by what had become the largest coal mining company in Spain. From the 1980s, most of the mines were closed and since then the city has had to change activities. The Romans also imported vines. The city was then known as Flavium. The vineyard prospered in the region, until the spread of phylloxera at the end of the XIXth century destroyed most of the vineyards, as everywhere in Europe. But the vineyard took off again, and you will see many vines in the Bierzo valley. Bierzo is a Spanish Denomination of Origin (DO) for wines located in the northwest of the province of León. Being surrounded by mountains on all sides creates a sheltered microclimate conducive to the cultivation of recognized quality produce.

But if the Romans introduced the vine to the region, the greatest expansion of viticulture is most certainly linked to the growth of monasteries, in particular the Cistercian order, in the Middle Ages. In this sense, Molinaseca played an important role in the historical development of El Bierzo. The road coming from Foncebadón was an old pre-Roman road. Caesar Augustus will take this road during the wars of conquest. Along this route were several castros, fortified settlements, notably at El Acebo, and another east of Molinaseca. The crisis at the end of the Roman Empire in the Vth century facilitated the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by various Germanic tribes, including the Suevi, then the Visigoths. In the VIIIth century, Muslims, who also came here, invaded the peninsula. Their presence in the region was ephemeral, because very quickly the new kingdom of Asturias, founded by Don Pelayo, protected the region. However, the sporadic Muslim presence led to the depopulation of hotspots, and the flight of inhabitants to the mountains, where they felt more protected. The repopulation of Bierzo revived in the IX century, under the Asturian king Ordoño I. In this period, the monasteries were repopulated, among them the Monasterio de Santa María de Tabladillo, located on the descent of Foncebadón, shortly before arriving at El Acebo. This monastery has long since disappeared. The revival of the monasteries was accompanied by an increase in pilgrimages to Santiago. This encouraged the birth and development of important cities in Bierzo, including Molinaseca, Ponferrada, and further afield Cacabelos and Villafranca del Bierzo.

It is still today a magnificent stage, in the majestic landscape of the mountains of León. This is the continuation of the stage of the day before, a crossing of the wild moor. This beautiful tumble is worth its weight in strong emotions. But there is no danger, except for your joints, which are already so stressed. You will remember it, it is signed in advance. At the bottom of the descent, you will catch your breath in the very beautiful village of Molineseca. At the edge of the river, you will now have reached the Bierzo Valley, whose capital is Ponferrada, a short distance further down the plain.

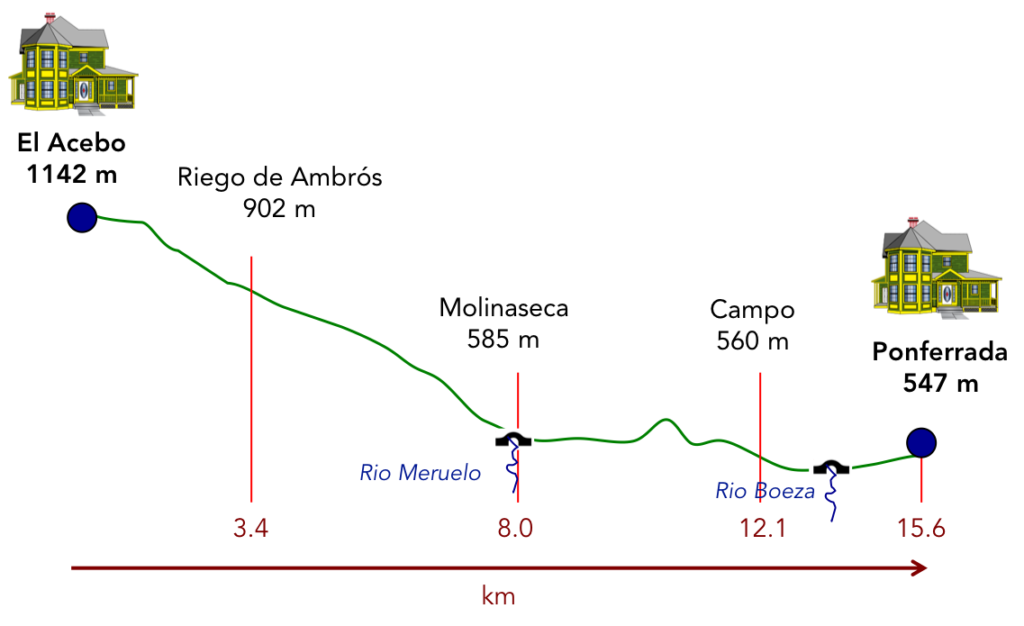

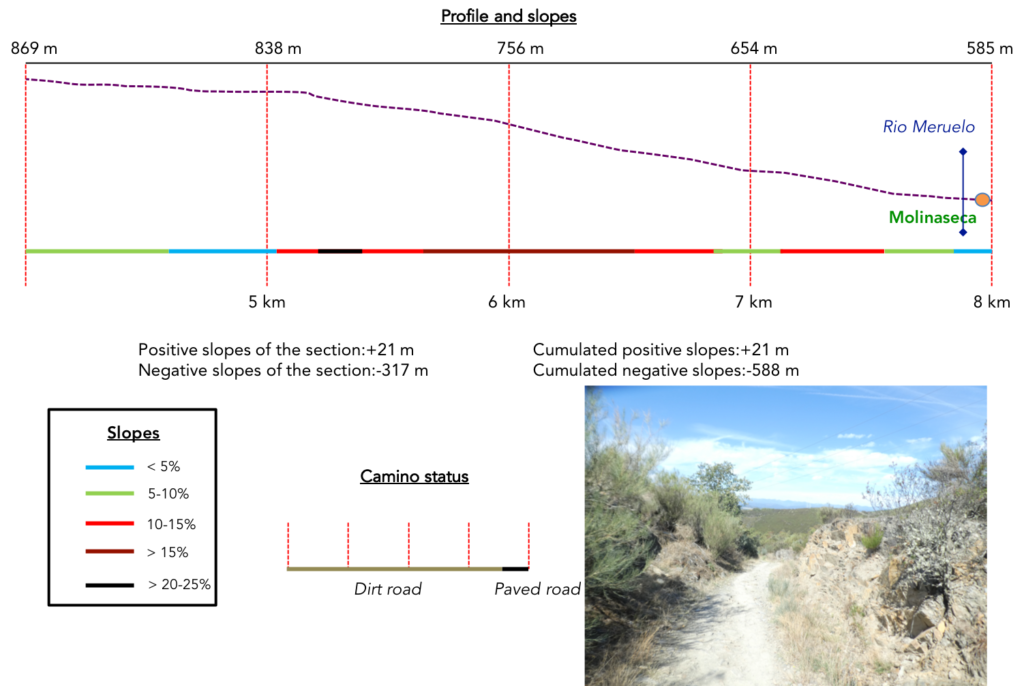

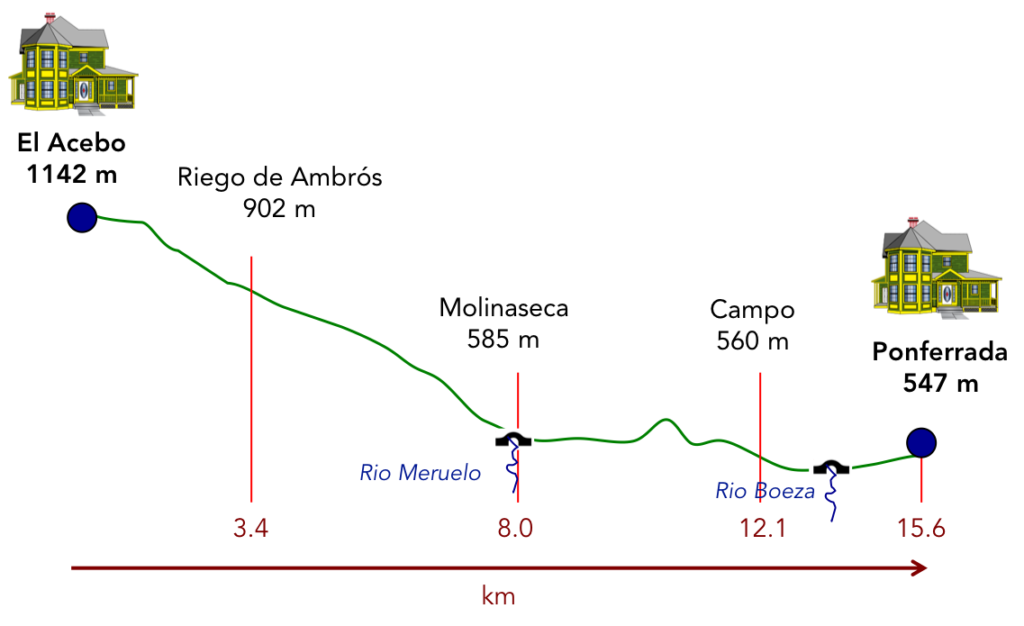

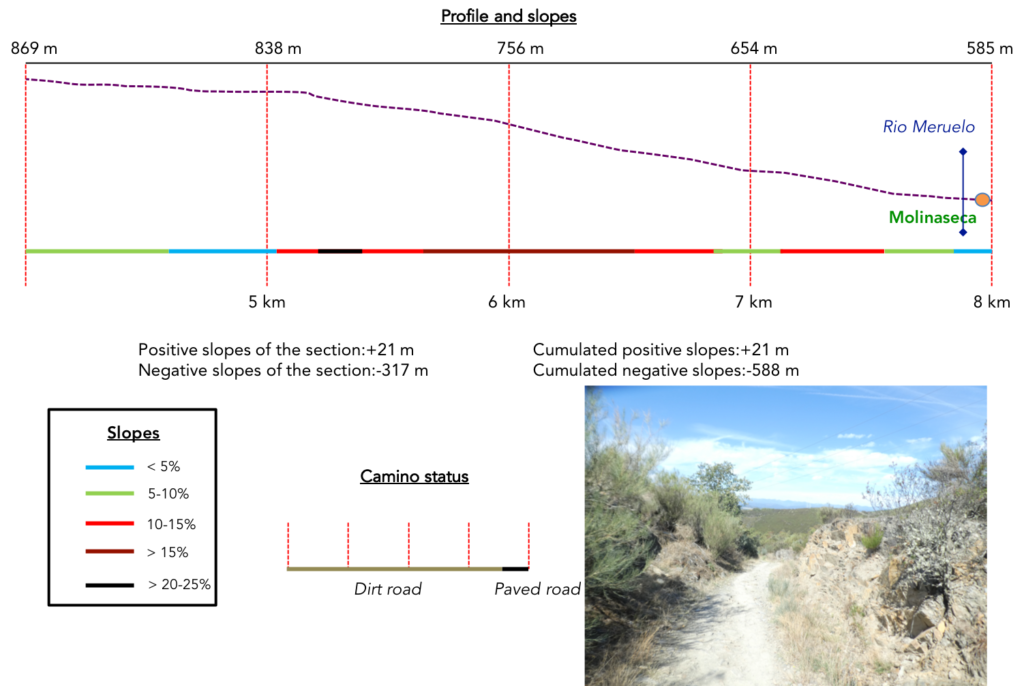

Difficulty of the course: Today, slope variations (+111 meters/-707 meters) are significant for such a short stage. It is above all a long descent, sometimes very steep. Thereafter, they are hills of no importance to reach Ponferrada.

Today, pathways or paved roads are fairly equivalent. Beyond León, many passages on the roads can be practiced on a strip of dirt, more or less wide along the road, but here, it is mainly a sidewalk:

- Paved roads: 7.2 km

- Dirt roads: 8.4 km

We did the route from León in the fall, in fairly good weather, unlike the first part of the route, which was done on soggy ground, mostly in sticky mud.

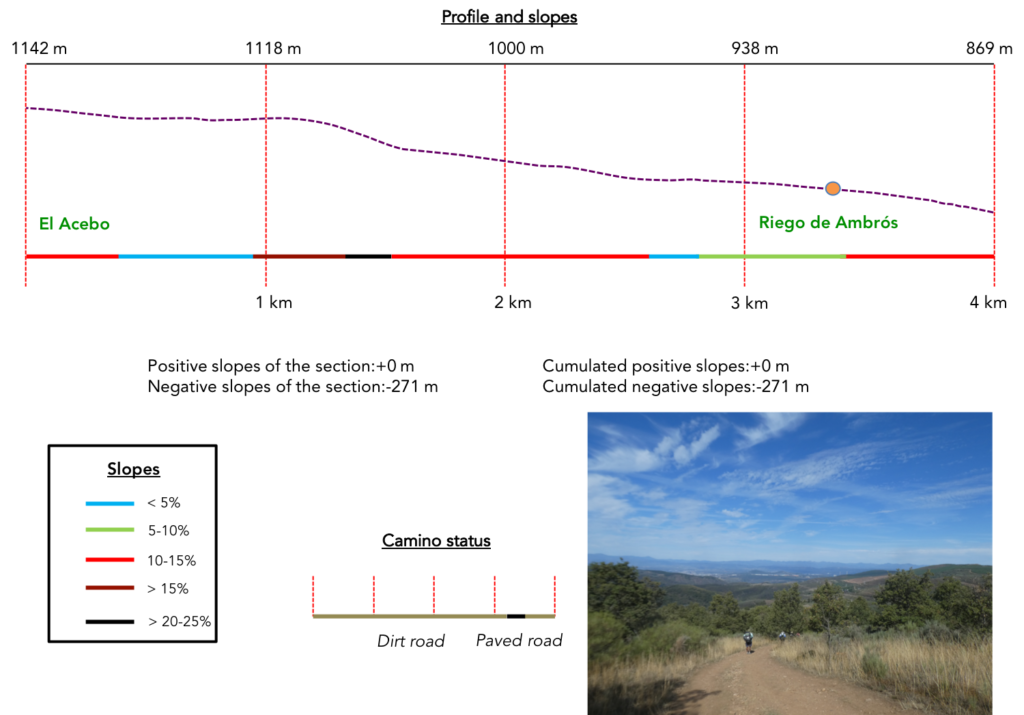

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes” reread the mileage manual on the home page.

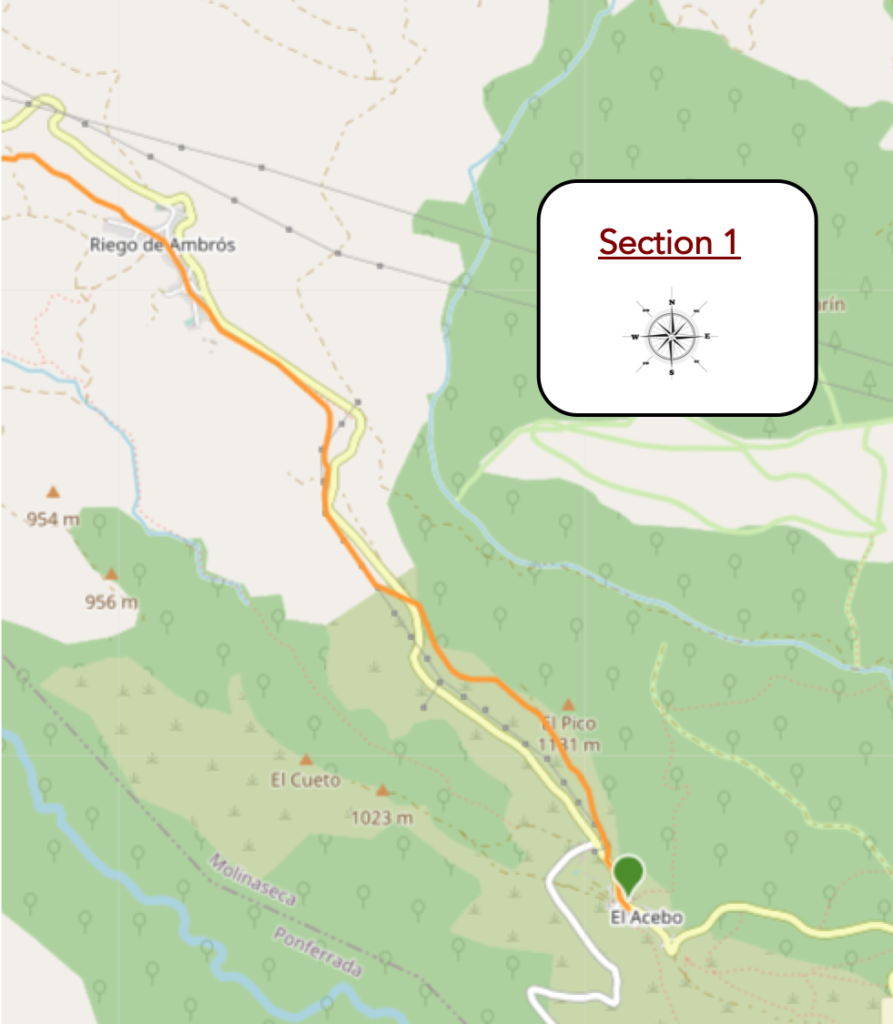

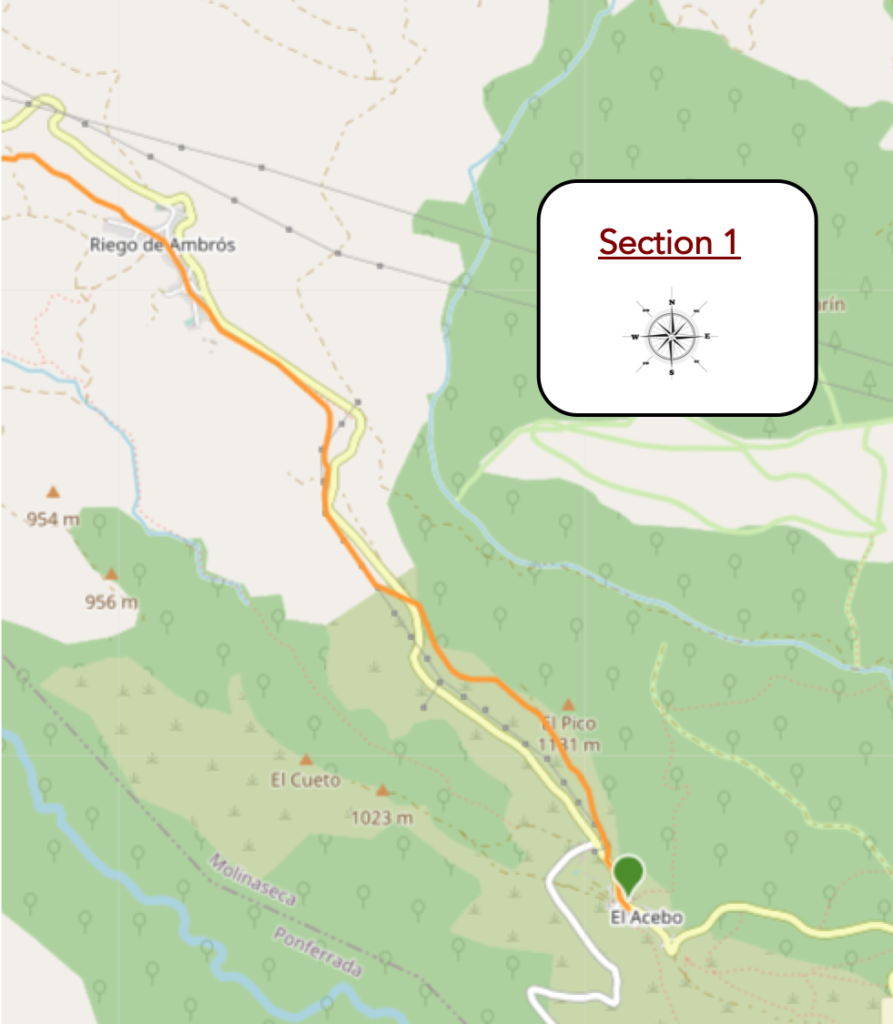

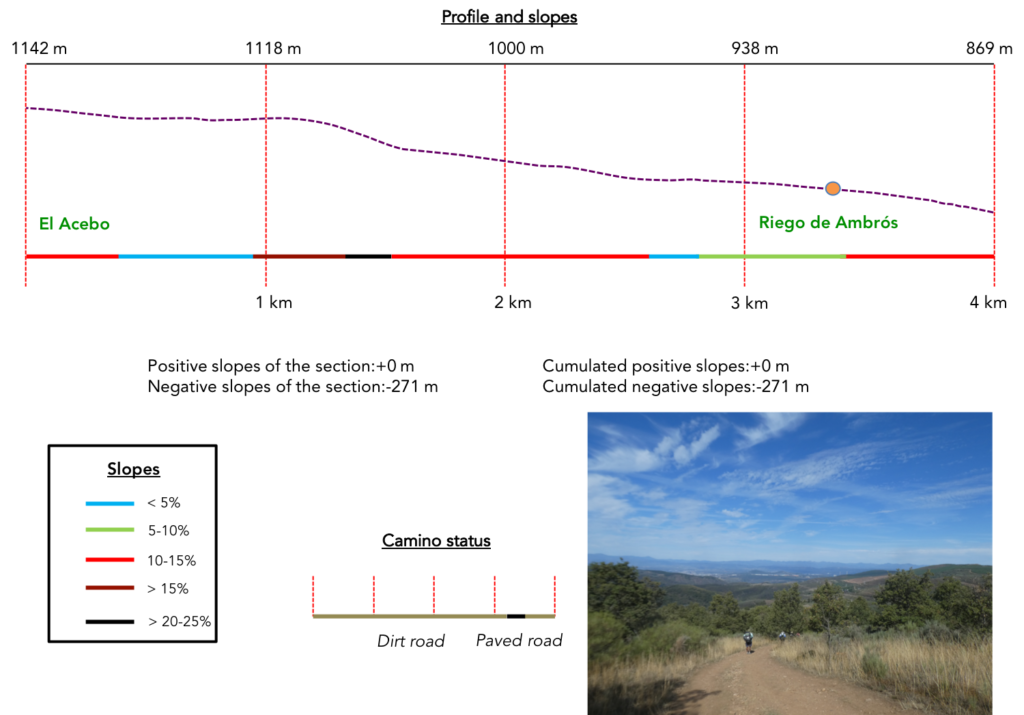

Section 1: Departure for a new and tough dive in the valley.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : difficult course, often with very steep slopes.

| The Camino leaves El Acebo behind the church and the beautiful stone houses of the village. |

|

|

| It transits little on the road to the pass… |

|

|

| …before leaving it for the dirt road. |

|

|

| At the start, the course presents no difficulty. It is a wide pathway that dawdles on the ridge. The landscape has not changed since you entered the slopes of the Montes de León. They are always dry grasses, wild cypresses, laburnum, and lavender for the most part, and clumps of oaks, mainly holm oaks. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway heads towards the end of the ridge, where an antenna stands. |

|

|

| This is where things will drastically change. The pathway will descend almost continuously into the plain. However, it does not seem too complicated, because the stones have strongly dominated since the day before. |

|

|

| But, the slope is steep, very steep, almost 20%. So, you see some pilgrims clinging to the slope, to survive and keep their balance. |

|

|

| Opposite, you see that the hills are pierced with small roads, probably for the installation and maintenance of wind turbines, because no one lives or cultivates anything in the arid moor. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope softens, but remains above 10%, when the pathway runs close to the pass road, but does not cross it. |

|

|

| You always find on the route the marks of the Way of Compostela, but there is no reason to get lost here. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope starts to rise again in the steppe, at nearly 15%. |

|

|

| Sloping down, you see the village of Riego de Ambrós emerging below. |

|

|

| Further down, the pathway passes on the other side of the LE-142 road. |

|

|

| Here, civilization is announced, 1 kilometer away. |

|

|

| So, the pathway, which has become softer, will follow the contours of the hill, as does the road just above. |

|

|

| Further on, it even slopes up the hill slightly.. |

|

|

| The arrival in the village is much less chaotic than the arrival in El Acebo. The slope is weak here. |

|

|

| Here you are 223 kilometers to Santiago. You’re making progress, right? Above the village you find the hermitage of San Sebastián y Fabián Riego de Ambrós and the parish church of Santa Mara Magdaena. The Camino does not go there. In the XIIth century, there was a hospice here for pilgrims. |

|

|

| Riego de Ambrós and El Acebo look alike like two drops of water. It’s the same charm, the same picturesque. The houses of wood and big sealed stones are like in the picture books. The very old beams are blackened by the sun and bad weather. Tiny windows, which allow you to see without being seen, protrude from the stone rubble. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses the long street of the village, which bathes in the same warmth, the same harmony. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, you’ll pass without transition from paradise to hell. |

|

|

The slope is not excessive, at less than 20%, but the balance is precarious on the large shales that bar all the way.

| Luckily, the ordeal is not too long, a few hundred acrobatic meters. Further down, the large stones fade, but the slope remains steady in the galloping jungle, where the chestnut trees take up a little space between the oaks and the countless bushes. |

|

|

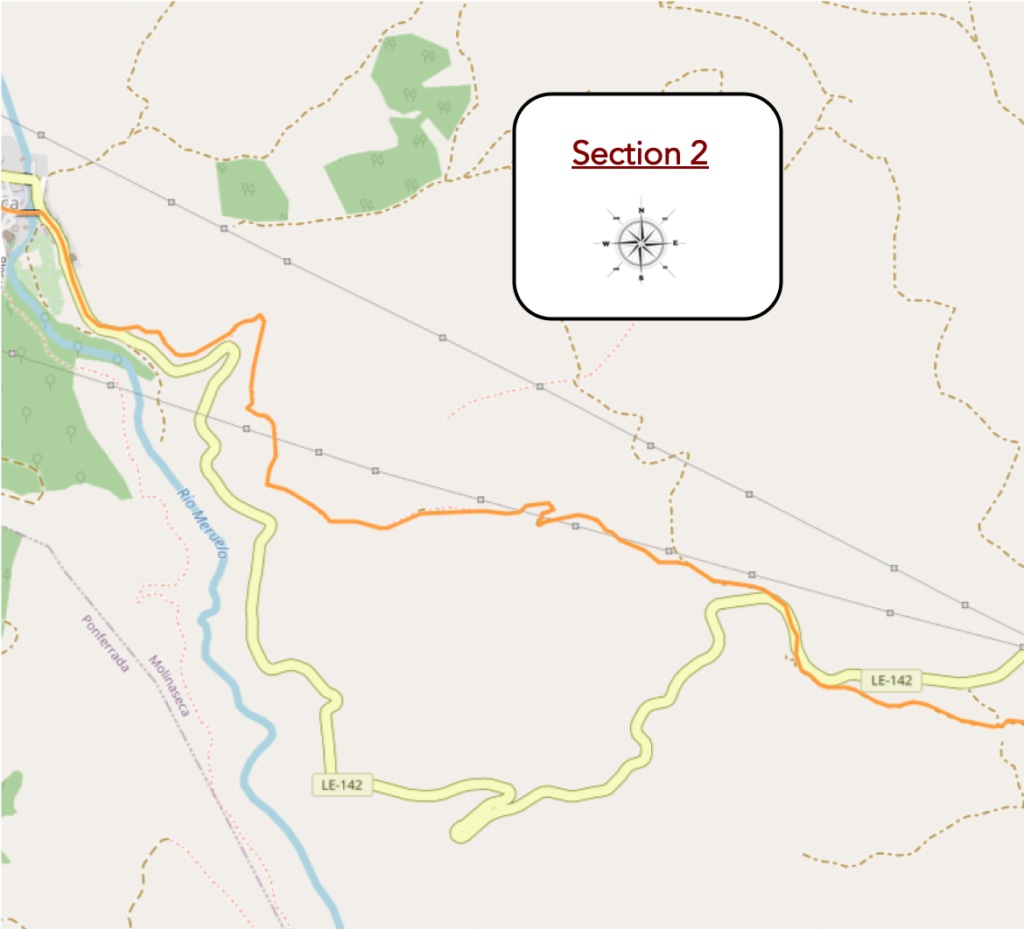

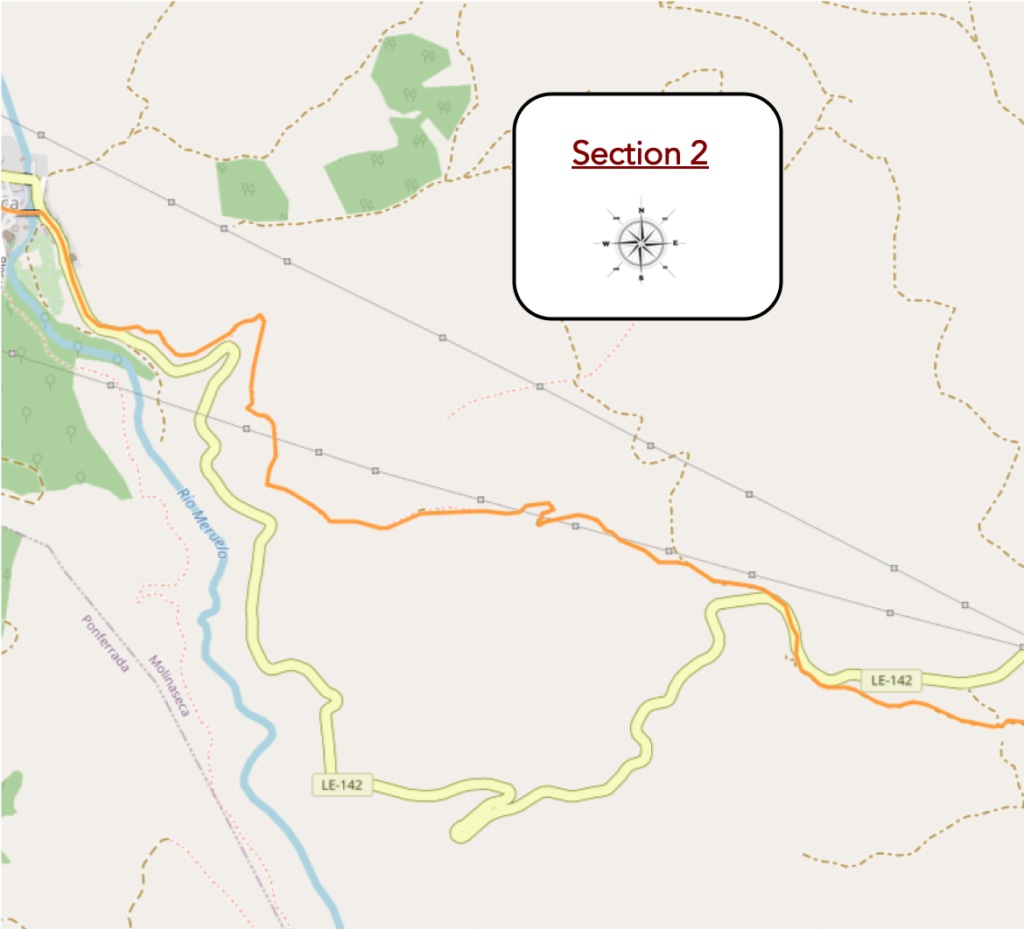

Section 2: In the slides of the Bierzo.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : difficult course, often with very steep slopes.

| Further down, it is as if the holidays had returned. The pathway slopes down an almost imperceptible slope in the moor where the trees gradually disappear in favor of the bushes. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway rejoins the LE-142 road… |

|

|

| … doing a few hundred meters in its company before setting out again in the virgin nature. |

|

|

| ere, the pathway remains soft, heading towards a pylon of the high voltage line. |

|

|

| When you see these signs, know that your destiny will change again. |

|

|

| Because immediately, the waltz starts again along the snags of rocks on a pathway as rugged as it is detestable. |

|

|

| Further down, it’s war again on slopes of around 20% and the show is not there to mitigate your ordeal. |

|

|

| In this confused and muddled nature, the wild cypresses are almost trees. |

|

|

| Further down, the stones come back in force to increase your pleasure. In rainy weather, you may need to rope yourself. |

|

|

| And the pleasure lasts, apparently for an eternity, in this labyrinth of stones, which does not diminish its inclination one iota. Under your feet, the stones roll at the risk of entangling you. |

|

|

| But, let’s stop whining. Some sports cyclists also run through here. |

|

|

| Let us reassure the next pilgrims who are going to embark for Spain. In this stage, at no time are there any rough passages, at most, a few passages where the shales outcrop like hard and brittle rocks. In places with steep slopes, you may even see people walking backwards. But the vast majority of pilgrims navigate here with ease, even if some brake with both feet with extreme caution. |

|

|

| Further down, the plain begins to open up a little below the narrow valley. You then see Molineseca, but there is still a long way to go to get there. |

|

|

| Sometimes a few brave cyclists honk and pass. Other times, real traffic jams obstruct the passage. You give them the ritual “Buen Camino”, and they let you pass, tense. They are often Koreans or South Americans, who hardly have a mountainous walk. |

|

|

| It is easy to understand that when you take 700 meters of negative drop in your legs (1,200 meters from the pass), you cannot do it with impunity. Yet further down, the slope decreases between 10% and 15% when the pathway sinks into a dale. |

|

|

| Soon, you see the road to the pass back, and the pathway joins it through a bed of large brittle shales. |

|

|

| No pilgrim will praise the beauty of this descent from the valley. On the other hand, many will remember that the slope was part of it. |

|

|

| Molineseca is just down the road. Molinaseca owes its name to the existence of several mills on the Río Miruelo. In fact, its name is a derivative of the Latin molinum (mill), in the plural molina, since not one but several mills existed in the village. At least 5 mills existed in the XVIIIth century, built on the river and on a dam in the deep valley, which tumbles over the village. To this was added the Latin adjective siccum, with the meaning of “dry mills”. Why? This would be explained by the fact that in some years, due to the movements of the riverbed, some mills would have been sometimes deprived of water and that people sometimes had to build irrigation canals to irrigate them again. |

|

|

| The road passes in front of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Angustias. The baroque sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de las Angustias (Our Lady of Sorrows) is partly built on the mountainside. A small chapel and a hospital for pilgrims were there in the XIth century. The present church is from the beginning of the XVIIIh century, with its apse set into the mountain. Its lantern dome and side doors are from the XVIIth century. The current square tower at the foot of the church, which partly hides the old facade, was built in the last century to stop the pressure of the mountain on the church.

On the other side of the road and the river is the parish church of San Nicolás de Bari. It is located on a promontory above the Puente Romano. It is a massive monument in the neoclassical style, built in the XVIIth century. Although the bridge and the mills were two key elements in the origin of Molinaseca, urban life was centered on the Church of San Nicolás. This church is already documented since the XIIth century. The current parish church was started in the second half of the XVIIth century, when the village had only a few hundred inhabitants, and was completed at the end of the XVIIIth century. The elegant tower, which preserves the first body of the medieval tower, is a belfry with a large clock. In a niche of the first body of the tower there is a stone statue of the titular saint, symbol of one of his miracles. The altarpieces of the church are Baroque. But you still have to come here during church opening hours. |

|

|

| Here flows the Rio Meruelo, the river that descends into the valley, which you will never have encountered. There is a river beach in season, very popular with locals and pilgrims, with terraces and bars. |

|

|

| The Camino crosses the Roman Bridge or Puente de los Peregrinos. This beautiful bridge is made of masonry with seven light arches, the first three of which belong to an older bridge and are half buried. The pebbles are not from Roman times either, but the setting is exceptional. The bridge gives access to Calle Real. This pedestrian bridge is not Roman but medieval in origin, dating back to the XIIh century. During its history, it has undergone several extensions and modifications, including a very important one in the XVIIIth century and even a last one in 1980. These changes were made necessary in part by modifications to the riverbed. |

|

|

| On the other side of the bridge, the Camino enters the village (1,000 inhabitants). The village of Molinaseca is documented as far back as the IXth century, when the Camino de Santiago began to gain prestige with the flow of pilgrims. From the XIIth century, new settlers arrived here, coming from different parts of the peninsula and even from beyond the Pyrenees. In the XIIIth century there was a barrio franco (French quarter) on the left bank of the river, near the church of San Nicolás. Undoubtedly, the bridge over the Miruelo river, which the route must cross to continue towards Ponferrada, was a decisive factor in the birth and development of the village. In the XIIth century, pilgrims were received in at least 4 hospitals here. There was also a mill near the bridge here. The village was known since ancient times as “un oasis en el Camino” (an oasis on the Way). For centuries it was a welcome stopover for pilgrims but also for Galician harvesters heading east to work the harvest on the other side of the mountains. |

|

|

| Three elements were decisive for the prestige of the village: the bridge, the old mills and Calle Real. As usual, village life revolved around the main street, which was also the pilgrim route. The cobbled Calle Real stretches from the bridge to the Viejo Cruceiro. It is lined with stone houses and noble mansions displaying the family coat of arms. The houses are lined up next to each other, separated by narrow alleys barely wide enough for a single person to pass through. There are several small perpendicular streets. However, the only other east-west street was Calle de la Iglesia, which ran parallel to Calle Real and led from San Nicolás Church to Viejo Cruceiro, where the two streets merged.

Many pilgrims will stop here, as many pilgrims come from Rabanal del Camino all the way here. But, it will be for them the next day a very long stage to go to Villafranca del Bierzo. Also, some of them push on to Ponferrada, to shorten the next day’s stage. |

|

|

|

|

| The street is charming and long. It ends in a square where the Viejo Cruceiro (Old Cross) stands. The stone cross is mounted on an octagonal column on a square plinth, with steps. There is a figure of Christ framed under a glass reliquary. Experts say this cross does not look medieval. |

|

|

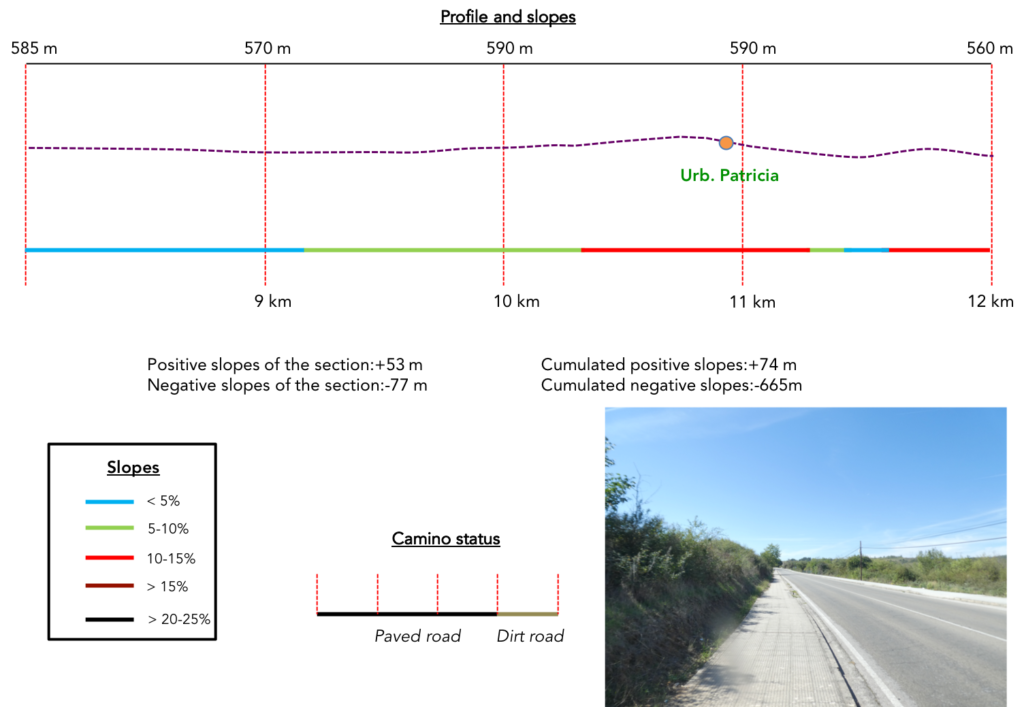

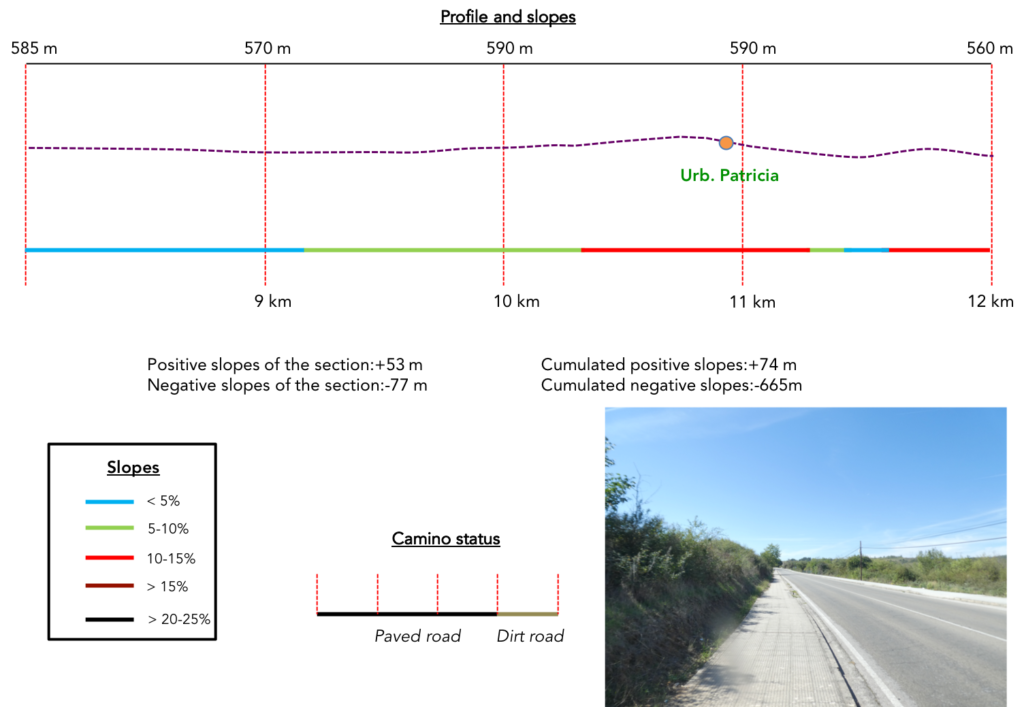

Section 3: Over the hills before Ponferrada.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without great difficulty.

| We have had a beautiful but difficult, wild journey so far. But, beyond Molineseca, it will be a completely different song. This will mostly be the road to Ponferrada. And it begins with the long crossing of the suburbs of the village on the sidewalk. |

|

|

| The village must be expanding, because on the embankments appear new colorful housing estates. |

|

|

| Further on, the LE-412 road leaves the village and runs up the gently sloping hill. |

|

|

| Over nearly two kilometers, it’s long and not alluring. The only spectacle is that of the rare vehicles circulating on the axis. |

|

|

| Above, the organizers have kindly made available a strip of dirt on the right, to make believe that this is not the road. But, the pilgrims stay on the left sidewalk. Weary, the road arrives at the top of the hill. |

|

|

| From here you see the towers of the outskirts of Ponferrada. You naively tell yourself that you will be there quickly. But think again. You are not going to follow the direct route, because the Camino francés has another program for you, choosing a dirt road, which you see heading up a hill away from town. |

|

|

| The pathway descends along a housing estate called Urb. Patricia. The pathway is wide, quite stony. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the depression, even if you see the towers of Ponferrada, the pathway slopes up on the other side, in the other direction. |

|

|

| It is a pathway so wide that you could pass two trucks abreast, but the landscape is as gloomy as possible. |

|

|

| At the top of the mound, the pathway descends, of course. From here you always see the towers of Ponferrada, always your azimuth for the end of the stage. |

|

|

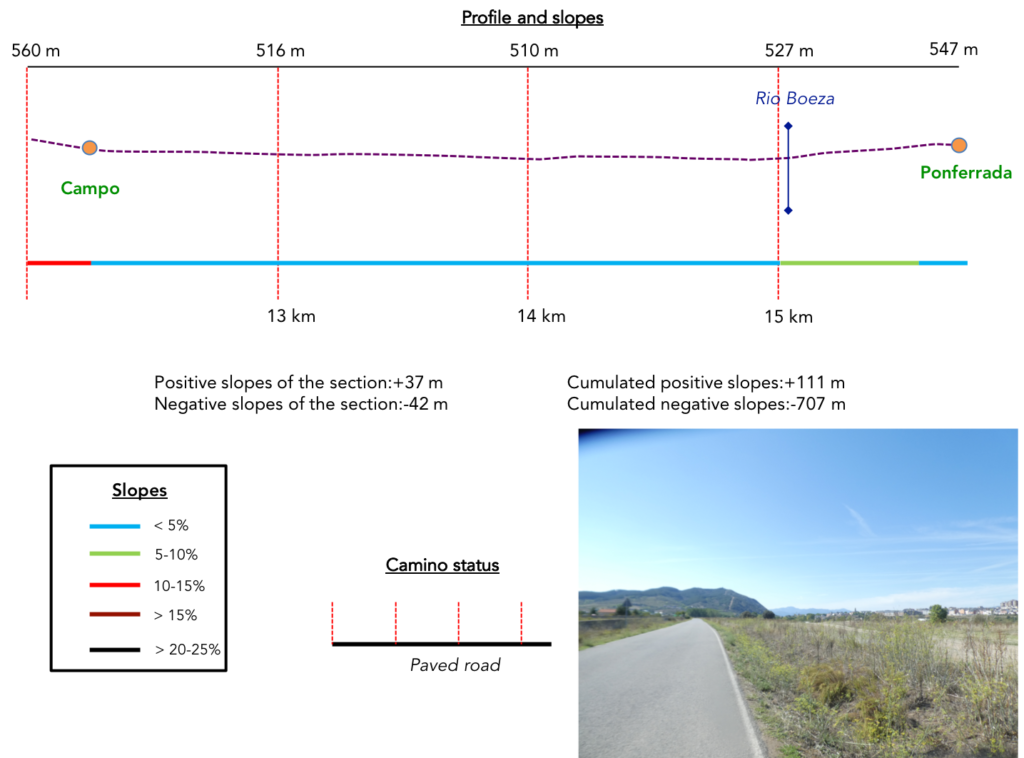

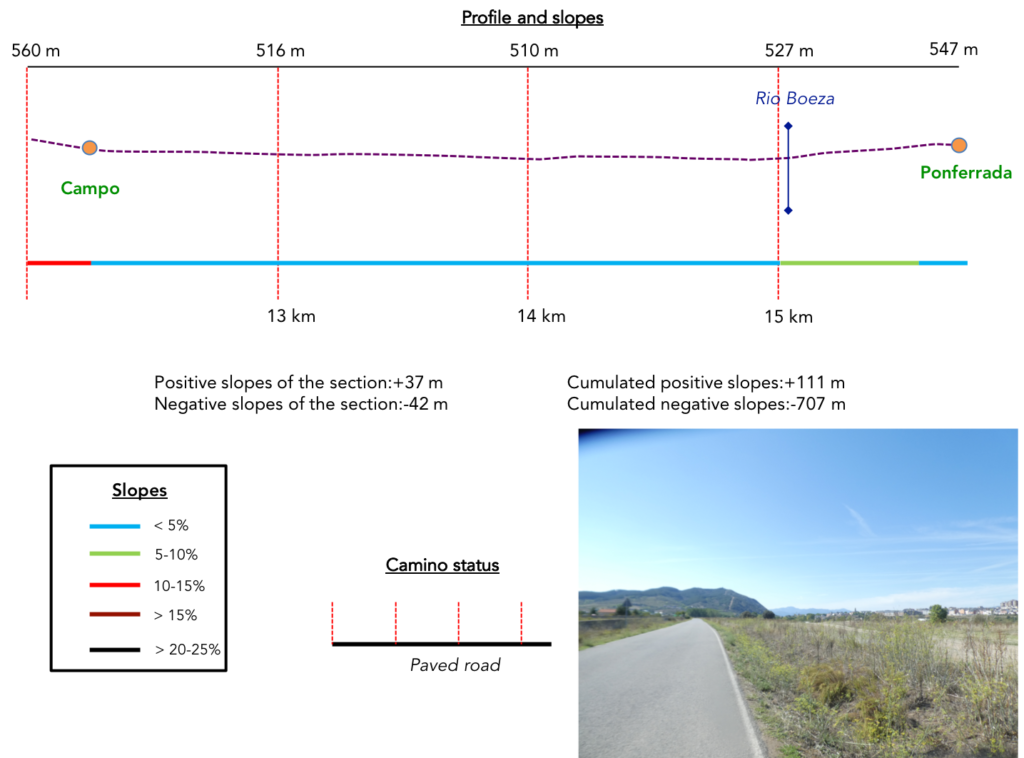

Section 4: Towards Ponferrada, the capital of Bierzo.

General overview of the difficulties of the route : course without any difficulty.

| Just below, the Camino arrives at Campo. |

|

|

| The Camino passes through the village, a village consistent with other villages in the region. The only difference is that it is not a village devoted to pilgrims. |

|

|

| Further on, the road leaves the old village to cross the new part in the plain. |

|

|

| It is then a long crossing of the plain on the tarmac. You are getting a little closer to the Ponferrada towers. |

|

|

| Further on, the road gets in Borreca, in the greater suburbs of the city. |

|

|

| It is a fairly large suburb, which is like any neighboring suburb of a fairly large city. Ponferrada still has 66,000 inhabitants. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the Camino heads towards the Rio Boeza and crosses it. The Rio Boeza is a tributary of the Rio Sil, which you will meet tomorrow when descending from the old town. The Mascarón Bridge is the oldest bridge in the city. It dates back to medieval times, and some call it the Roman bridge, because of its barrel vault. But this bridge is no longer original, having been modified many times. It is pedestrian only. |

|

|

| Beyond the bridge, the Camino climbs towards the city center. |

|

|

| It is a fairly long ramp that runs above the station and the railway line. Here runs the train connecting La Coruña to Palencia, ensuring direct connections with the most important cities in the north of the country. |

|

|

| The Camino then arrives under the city center, under the castle. |

|

|

| Ponferrada is the capital of the Bierzo region. Of Roman origin, from the Xth century, with the rise of the pilgrimage to Santiago, a town called Pons Ferrata, named after the iron bridge that crossed it, developed. The old town of Ponferrada stretches out at the foot of an imposing castle founded by the Templars in the XIIIth century for the protection of pilgrims. In the Middle Ages, it was one of the most important fortresses in northwestern Spain. It is an immense convent-fortress, polygonal in shape, which retains its towers, battlements and robust walls.

Due to camera failure, here we will borrow some images from the internet to give you an idea of the city. |

|

|

| Wikipedia Creative Commons; auteur jgaray |

Office du tourisme |

| The baroque church of San Andreas dates from the XVIIth century. It is located at the foot of the castle. If it’s open, you’ll find the Christo de la Fortaleza, a relic that was in the Templar Castle. The most important church is the Basilica de Nuestra Señora de la Encina (Basilica of the Virgin of the Oak). The old medieval church of Santa María, erected at the end of the XIIth century, became too small, so this basilica was built at the end of the XVIth century, a construction that lasted until the end of the XVIIIth century. It is rather Renaissance in style. It is dedicated to the Patroness of Bierzo, whose image was found in the hollow of a holm oak (encina) by a Knight Templar. |

|

|

| Wikipedia Creative Commons; auteur B25es |

Wikipedia Creative Commons; auteur Zarateman |

| In 2003 a statue was placed in the Plaza de la Encina representing the discovery of the image of the Virgen de la Encina. A Knight Templar stands next to the remains of an oak tree holding the image of the Virgin in one hand and a sword in the other. |

|

|

| Image par Ferran Gómez de Pixabay |

Image par Ferran Gómez de Pixabay |

| Ponferrada developed as a town between the XVIth and XVIIIth centuries. At the beginning of the XXth century, the city had only 3,000 inhabitants. Today, a population of over 67,000 inhabitants makes it the last major city before Santiago de Compostela. Today it is a modern metropolis and the capital of the El Bierzo region.

Many small alleys crisscross the historic center (Centro antiguo). You will find the Clock Tower there, built in the XVIth century, amended in the XVIIth century, located on one of the gates of the medieval enclosure, the only one that is preserved, with its granite freestones, its slates, his coat of arms and his bell. The bell was once used to sound the alarm in case of fire or for prisoners who escaped from prison. Calle del Reloj stretches between Plaza del Ayuntamiento and Plaza de la Encima. The streets, as well as the two squares, are pedestrian zones. Calle del Reloj is well preserved, surrounded by houses with coats of arms and traditional balconies filled with flowers. Right next to it stands the Town Hall (Ayuntamiento), a XVIIth century building. |

|

|

| Wikipedia Creative Commons; auteur Lancastermerrin88 |

Wikipedia Creative Commons; auteur José Luis Cabana |

Logements

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 7: From Ponferrada to Villafranca del Bierzo |

|

|

Back to menu |