In the Meseta, a little further from the paved roads

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

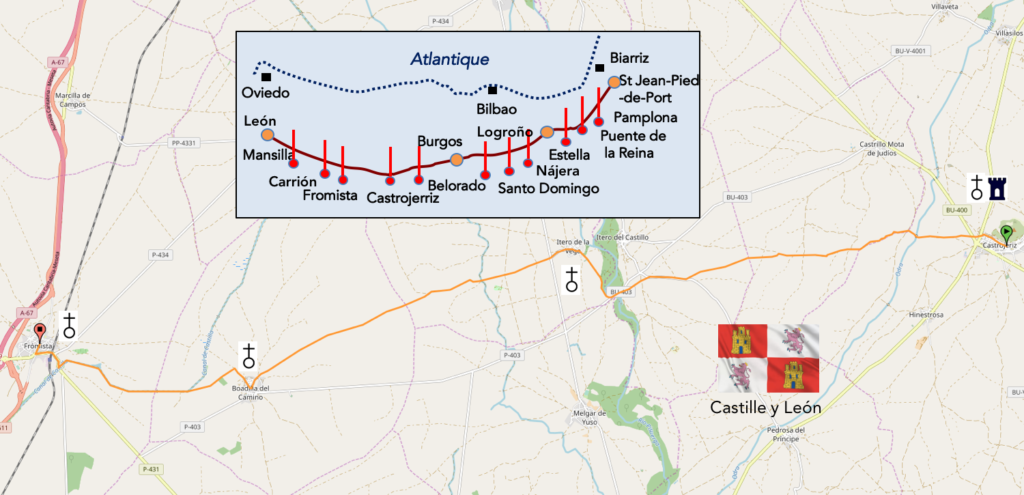

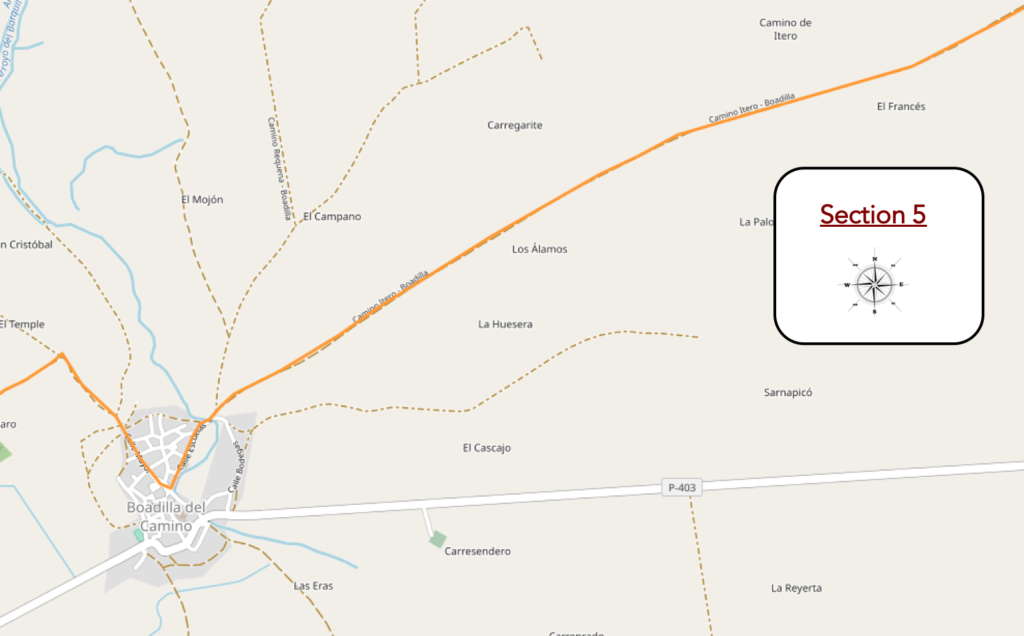

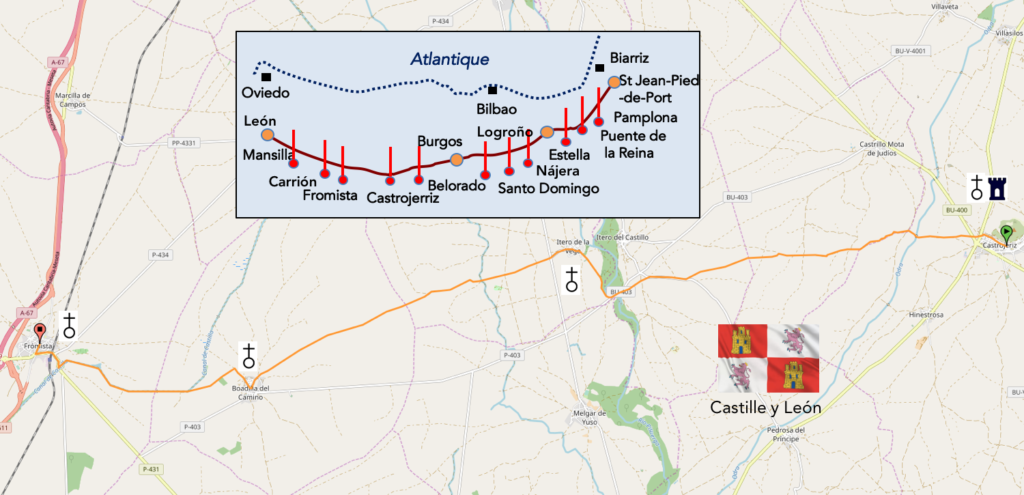

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-castrojeriz-a-fromista-par-le-camino-frances-33853561

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

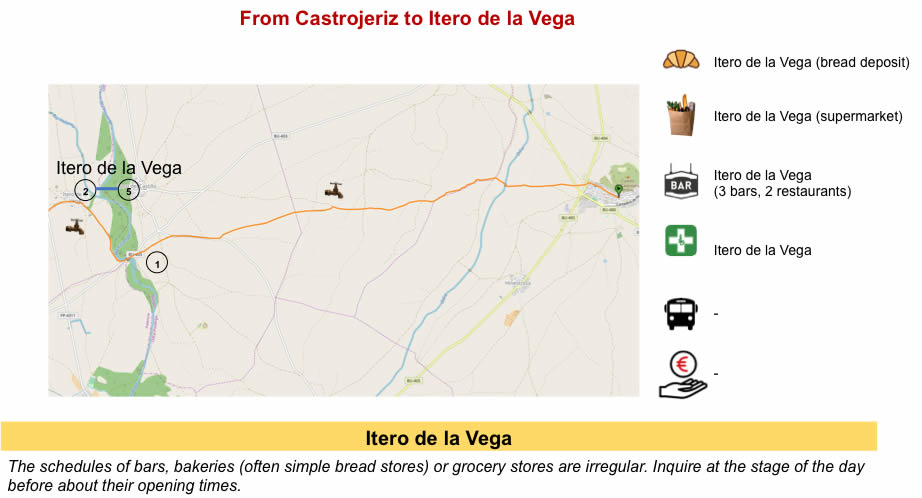

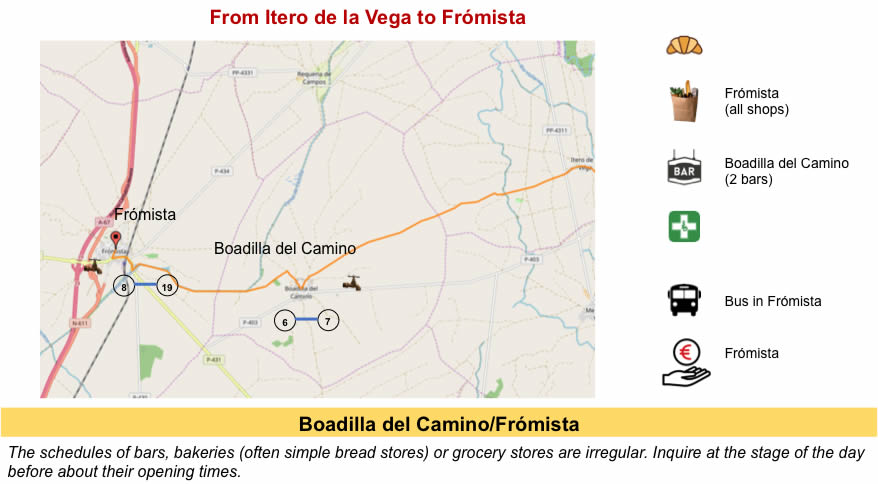

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Castile y León is the granary of Spain. Wheat and barley are grown almost equally, and much less oats or other species. The area dedicated to maize in Spain is much smaller. It is in the region of León that you find mostly corn. Meseta is still almost 2 million hectares, something like half of a country like Switzerland.

In today’s stage, the Meseta is quite pleasant. The route is almost always far from the paved roads, it is pleasant to point this out. These are very wide dirt roads that cross the fields of cereals. We have repeated the same stories many times, rehashed this or that aspect of the panorama. We will do it again. But, obviously, it is not easy to mount many details, which hardly exist in this green desert in spring. And as is customary in the Meseta, the villages can be counted on the fingers of one hand, let alone. Here, there are only two on a 25-kilometer stage. But all these villages have a remarkable infrastructure, which makes the charm and precision of the Camino de Compostela in Spain.

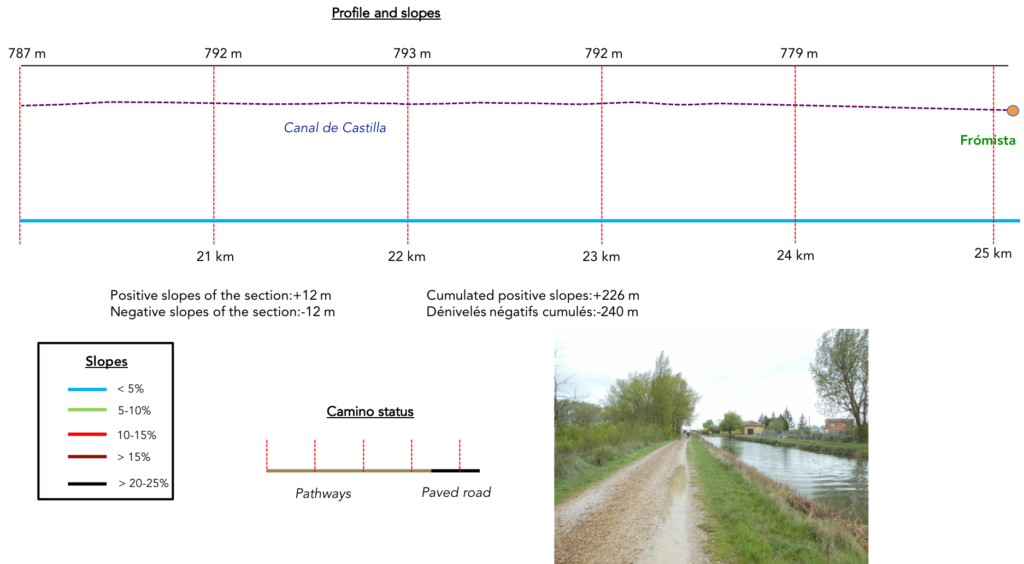

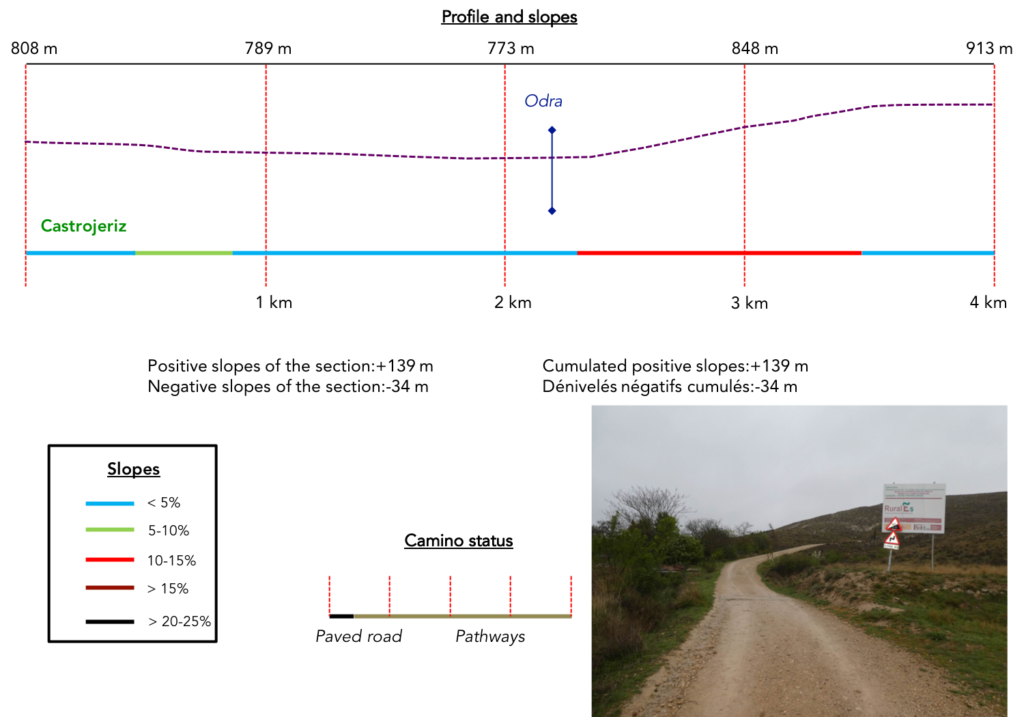

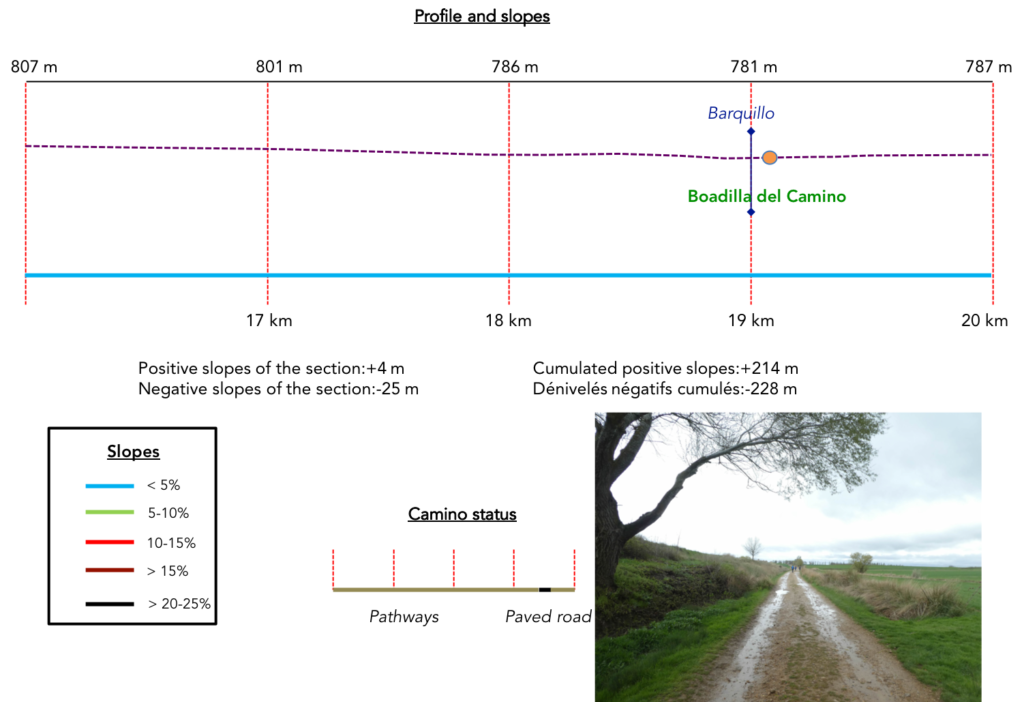

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+226 meters /-240 meters) are again very low. But, do not trust it if you think it will be holidays. Holidays, yes, if the weather is nice, and after completing the climb on the hill at the exit of Castrojeriz, almost 15% slope on two kilometers.

As we said above, today the dirt roads have a clear priority:

As we said above, today the dirt roads have a clear priority:

- Paved roads: 4.1 km

- Dirt roads: 21.2 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

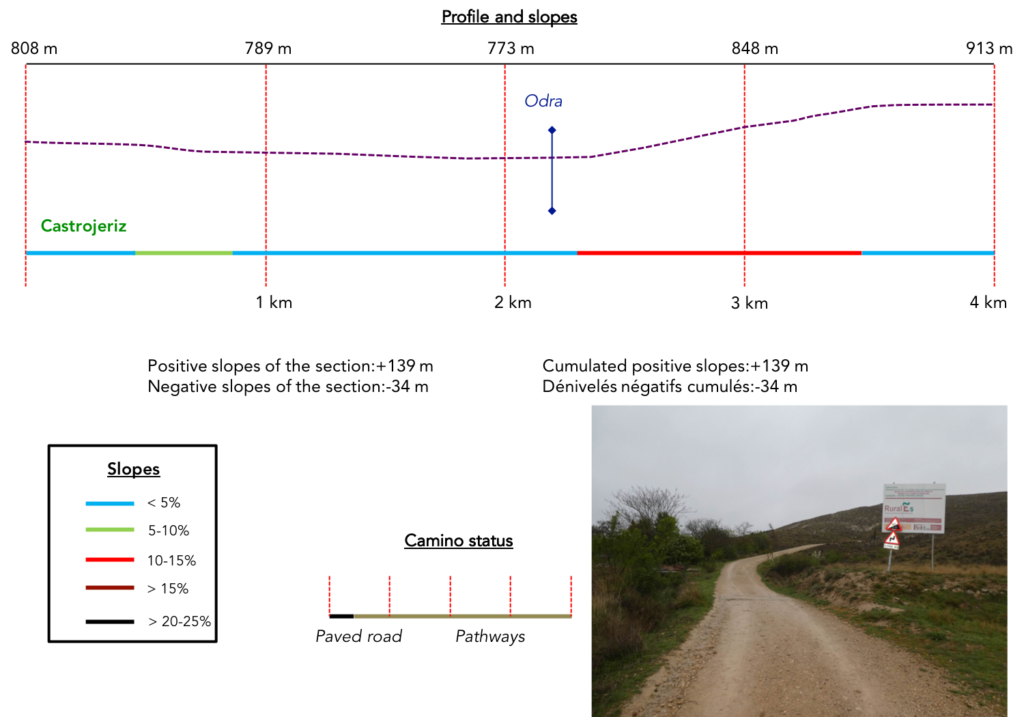

Section 1: Here, you will have to pass over the mountain.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: the only real difficulty of the day’s stage.

| This morning, here, the temperature is 2 degrees. They announce rain, wind and perhaps even snow. And, it’s true, it is already raining on the Meseta. Beyond San Juan Church, at the end of the borough, the Camino slopes down to the crossroads of the roads at the bottom. |

|

|

| On the track pilgrims are lined up as if to go to war. The Camino crosses a small road at the exit of the borough and reaches the plain, in the wheat fields. It is expected that the rain will last because heavy black clouds are charging in the distance. By the way, pilgrims have already donned their rain suits. |

|

|

| Here is no surprise. The pilgrims consulted their notes: 2 kilometers of flat, then the passage by the mountain. In the distance you can already see the road meandering in the mountains. |

|

|

Further ahead, the pathway gets near the Odra River.

| In the past, there was a Romanesque bridge here. The pathway runs today on another bridge, today wet and slippery. The river flows, peaceful, under the black poplars. The climb on the hill is not far. |

|

|

In front of you is the main course. The climb on the mountain is still almost 150 meters of elevation over a long kilometer, with slopes ranging between 10% and 15%.

| It is especially the start that is steep on a wide pathway, sometimes quite stony. The sides of the hill are streaked with veins of mica which were extracted in Roman times. |

|

|

The cyclists who make the Camino francés are more and more numerous. Turning, you see them lined up, in single file, on the way.

| Here, the landscape is a scenery of barren moor and clay. It is beautiful, a sublime savagery, which sharply contrasts with the fields of cereals, which unfortunately become tasteless by too much repetition. In hot weather, it is even more demanding here than in rainy weather. |

|

|

| The bikers parade, bent over their machine, getting short of breath. They are not all advancing at the same speed. It does not matter! They will wait for the last one at the top of the mountain. |

|

|

| The Spaniards liken this way to a “colada”, a “draille” as for the transport of cattle in Aubrac, in France. Some pilgrims have a heavier step and struggle under their load in the more difficult places of the track. It is often older ladies, often American or Asian, who walk alone with courage and determination. But, the deliverance, is near, because the way gets to the top of the mountain. |

|

|

| The pathway soon reaches the summit, Alto de Mosterales. The Spaniards also call it the Pico del Francés, to make it more tough. Turning around, Castrojeriz fades into the distance and disappears from view. |

|

|

| Further afield, the pathway flattens for a few moments on the high plateau, in the middle of the cereal fields. In this country of wind and cold that no obstacle contradicts, the trees here can be counted without difficulty. |

|

|

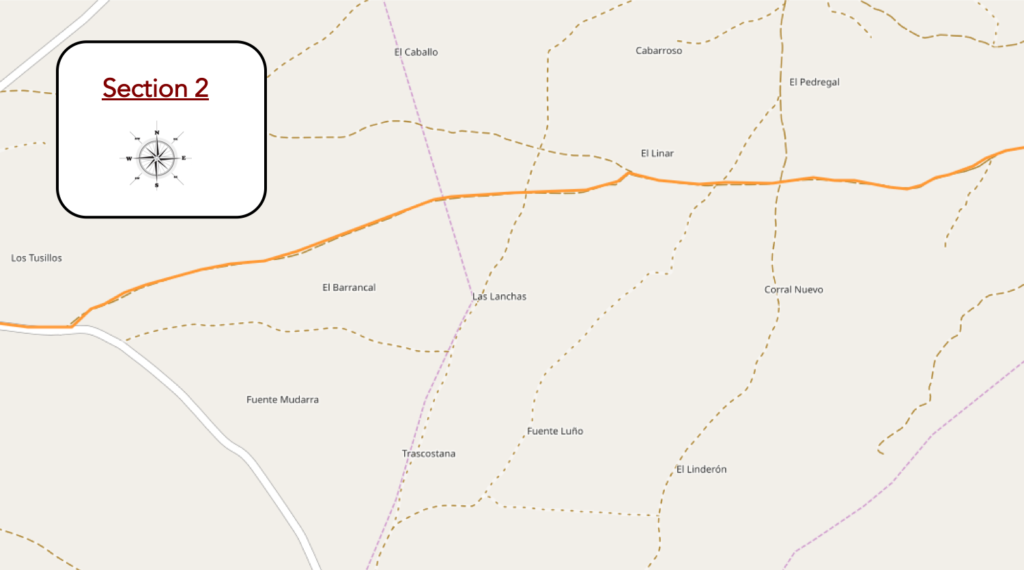

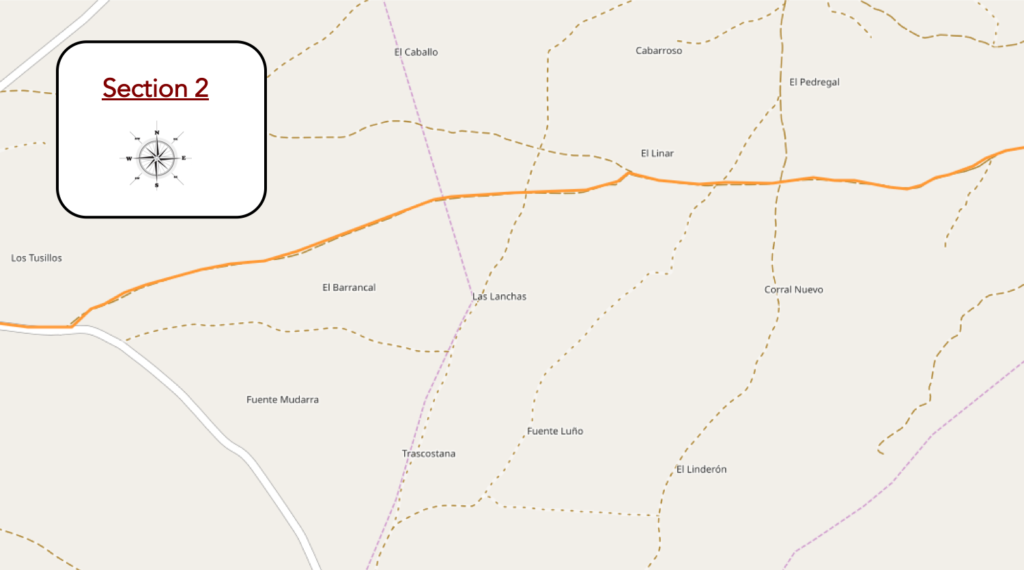

Section 2: Some waves in the immensity of the beautiful Meseta of Mostelares.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without problem, after the steep descent from the mountain.

| The pathway still flattens for a few moments before descending. From up there, the site is grandiose, often with this kind of serenity that often marks the pilgrim. It’s as if time stands still. Everything is in place for the soul to panic, with even more this hint of fog which creeps in and descends on the distant hills on the horizon. |

|

|

And now it starts to snow, when the pathway begins the descent. In this rainy spring, the rain no longer surprises anyone, but the snow, all the same? It’s beautiful like a gift from heaven.

| The descent is slippery in these conditions, with initial slopes significantly exceeding 15%. Here, they poured concrete to make the passage easier. The snow is tickling the faces. The pilgrims will all have memories for their family and friends. Come to Spain, in the country of the heat wave and find snow. Funny, no? All pilgrims will talk about tonight in the “albergue“. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope softens and the dirt road quickly regains its rights. You can see the pathway in front of you, often lined with wild grass in the spring, disappearing into a very distant horizon. It’s green, magical, like a painting by a Flemish painter. |

|

|

| The cyclists left and the snow stopped. The rain and the wind got involved in an ocean of cereals under a low sky loaded with black clouds. It is a heavy rain, always obstinate, sometimes aggressive, which streams on the mud of the road. |

|

|

| And the fields parade again, immense, infinite, on both sides of the pathway. These landscapes filled with emptiness, this nature as far as the eye can see, they look like doors opening onto the invisible. Today, the granary is green. But, later, these expanses of cereals will take, at harvest time, the ocher tone of the sands of the great African deserts. The harvest often takes place in the month of June, when the hordes of pilgrims are passing along the way. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway finds a zone of delight for the walker in rainy weather. Here, you have to find grassy areas to put your soles on or wade through the slush, in the clay. Many pilgrims then pass instead along the fields. But, is it really more comforting? Here, some areas are still covered with green manure or have already been plowed. The farmers must have fallen behind this year and it will be necessary to wait for the soil to dry out so that the tractors do not get bogged down, before planting corn in all likelihood. |

|

|

| It is ecstasy, absolute pleasure. The ground takes on a little more iron and you soon see the hill at the end of the high plateau. |

|

|

| At the top of the hill, there is a picnic spot, the Fuente del Pojo, (Fountain of the Pou) where no doubt no pilgrim will stop today in the rain to light the barbecue. However, there is a source of fresh water and the only shaded place in this area. The pilgrim will undoubtedly wait for the next “albergue” to replenish his energy. |

|

|

| Further afield, the Camino flattens again on the paved road. It also sometimes happens that pilgrims bless the saving asphalt. |

|

|

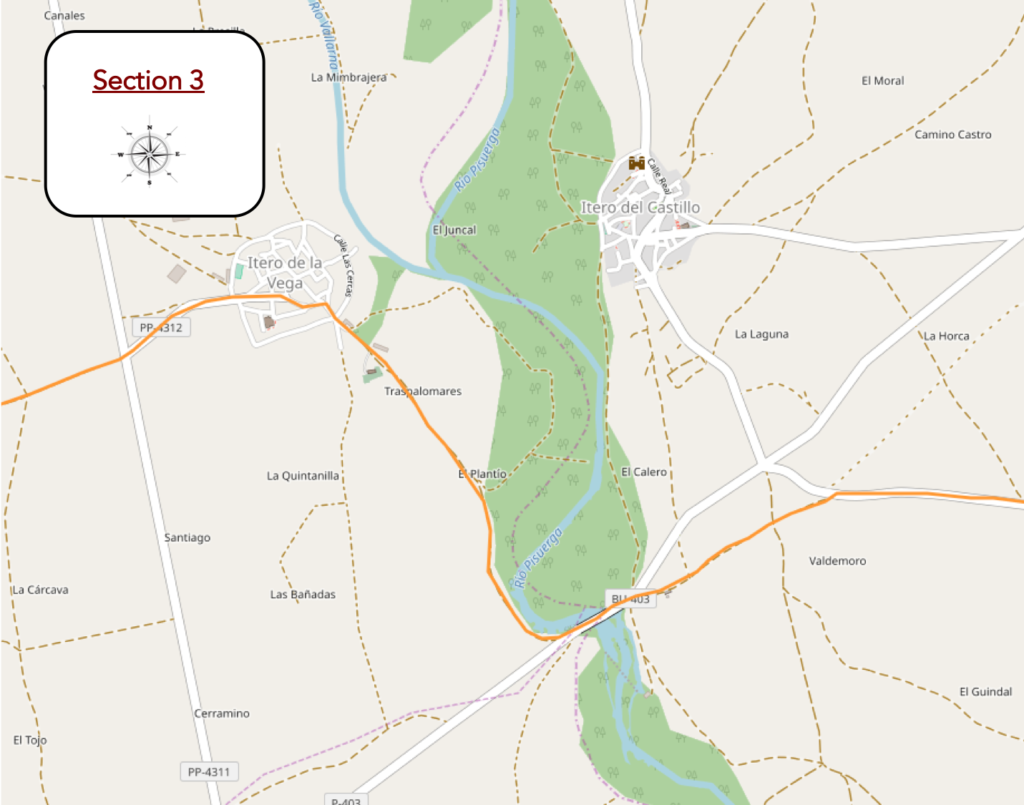

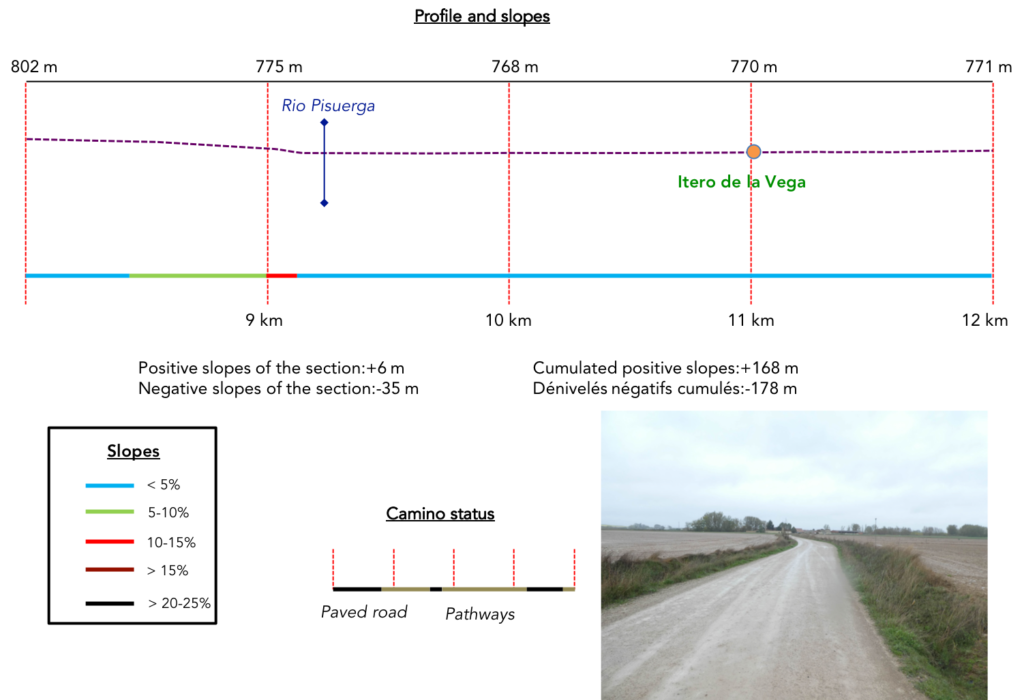

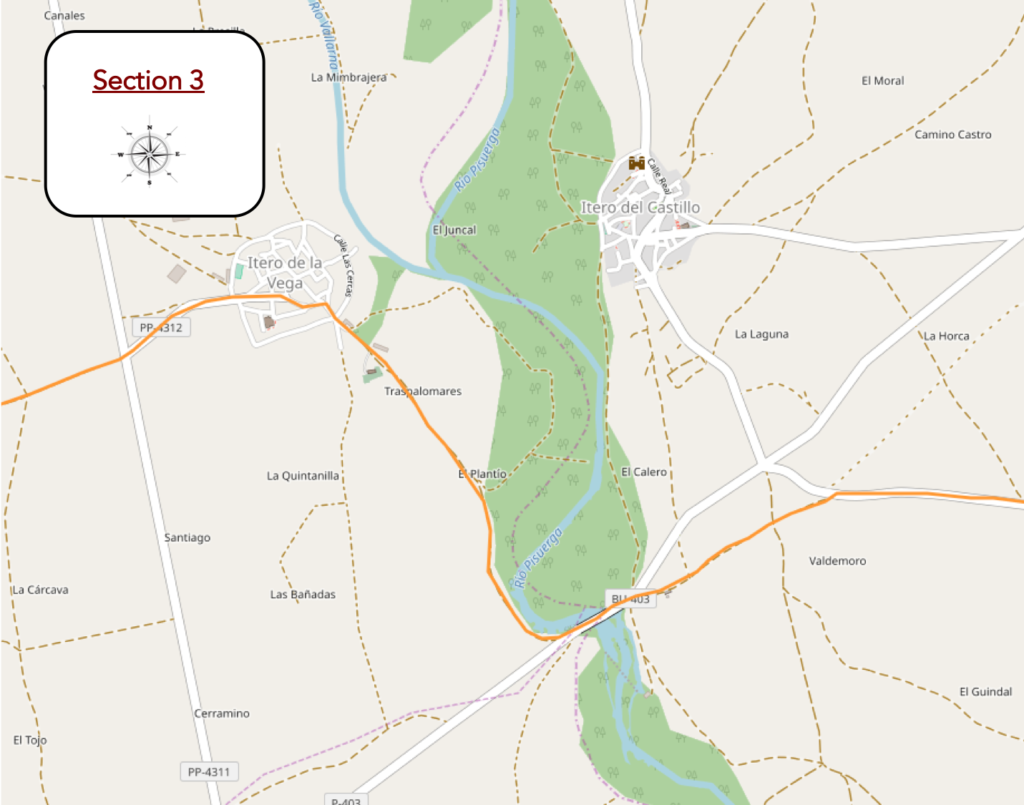

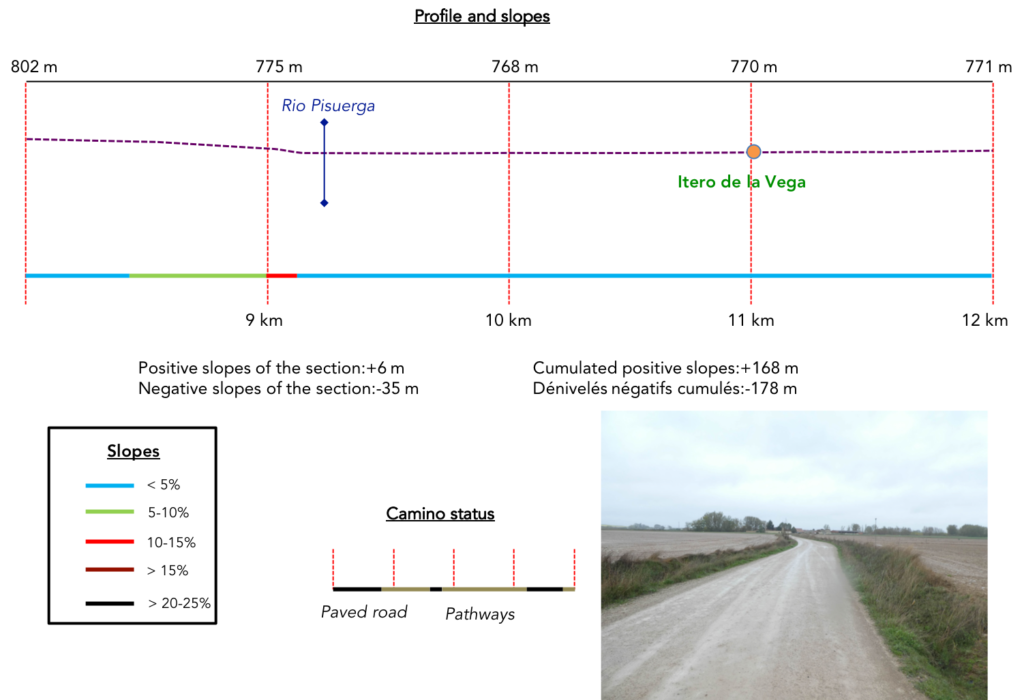

Section 3: Through the Romanesque bridge over Rio Pisuerga.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| It’s still raining hard on the Meseta. The wind is blowing violently in gusts, coming from the southwest. There is not much obstacle to stop the wind in these regions sometimes flat as the hand. The Camino follows the rough road a bit. In front of you, sheds, the only tangible sign of the presence of peasants in the country, because there is never an isolated farm and the sheds are all lined up on the outskirts of the villages. |

|

|

| A little further on, the Camino starts again on a dirt road, now completely soggy, like a sponge where water runs off everywhere. The foot sinks and drags the stubborn mud with it. |

|

|

| The pathway soon gets to the hermitage of San Nicolás de Puente Fitero, a Romanesque building dating back to the XIIth century, recently renovated by volunteers from the Confraternity of Santiago de Compostela in Perugia, Italy. We know that it belonged to the Knights of Malta, an order that protected the pilgrims of the Middle Ages. Today, volunteers provide the reception, even offering the washing of the feet. It is also a place chosen to have the “credencial” stamped, while listening religiously to a volunteer who tells the story of the place and speaks only Spanish. |

|

|

|

|

| A stone’s throw from the hermitage, the pathway gets to the Roman bridge over the Rio Pisuerga. This bridge is quoted in the Pilgrim’s Guide to the Code Calixtinus, as proof that the pathway passed through here. The Puente Itero (also called Paso Itero, Puente Fitero) is a bridge with 11 arcades. This bridge was once the historical border between Castile and León in a highly contested region throughout the Middle Ages. The original bridge was built by King Alfonso VI of Castile and León at the end of the XIth century to unify the kingdoms of Castile and León. It was originally in the Romanesque style, but was modified in the Gothic period. Thus, some of the vaults are semi-circular and others ogival. The XVIIth century remodeling retained the original Romanesque style. It is one of the longest bridges of the Camino. Not all 11 arches are visible today as some are partially buried by farmland next to the bridge. |

|

|

| The Rio Pisuerga is a fairly large river. Unlike in France, where the course mostly meets only small streams, here in Spain it is often large streams. It is a paradox for this flat part of the country, but the region is not so far from the mountains of Cantabria which border the country to the north, near the sea. Crossing the bridge, you enter the province of Palencia, one of the 9 provinces of Castilla y León. If you take the train from León to Burgos, you will pass through Palencia. The province of Palencia is located in the northern part of the autonomous community of Castilla y León, between the provinces of Burgos and León. It is north of Meseta Central, south of Tierra de Campos. The north is crossed by the Cantabrian Mountains. |

|

|

| The Camino then follows the road that leads to Itero de la Vega. The road runs along plantations of black poplars. |

|

|

The poplar is really the tree symbol of all this northern region of Spain, the species most clearly represented.

| Quickly you’ll see the village. |

|

|

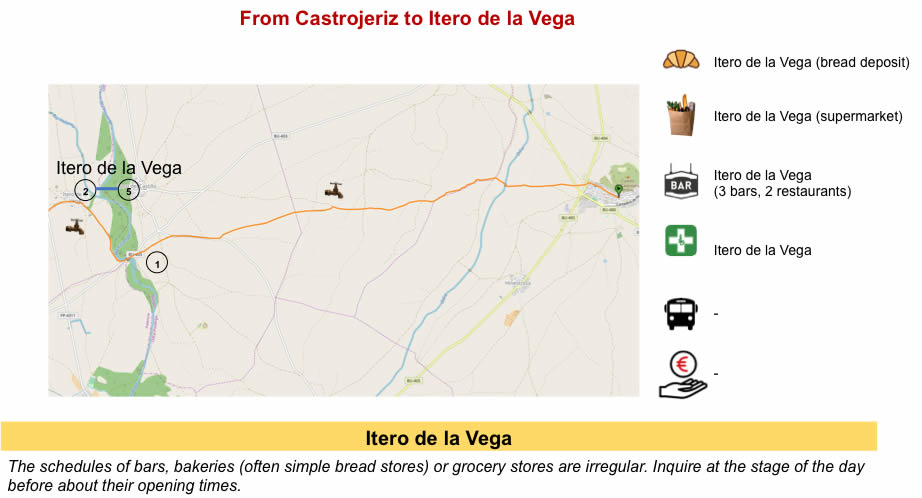

| Itero de la Vega is located in the so-called Tierra de Campos region. It was an important place in the history of the founding of Castilla y León. Its origins date back to the repopulation of the region between the IXth and Xth centuries, during the Reconquista. In the Middle Ages, Itero de la Vega had a hospital for pilgrims, now converted into a bar. |

|

|

| Today, the rain is intensifying. The first restaurant is literally stormed by pilgrims. After walking more than 10 kilometers in the rain, it is good to put down your cloak at the entrance and warm up a little by swallowing a coffee, or even by tasting a bocadillo or a tortilla. Here, even the grandfather diligently serves the coffees at the bar. There are crowds, let’s be honest. It is an essential rule of marketing, to be well placed. The other bars further in the village will be deserted, or almost. |

|

|

| And if we change a little time, one day of great weather. On the village square, stands a rollo juridiccional, that is to say a jurisprudential column. You will read later what this is for. Here it is very sober. |

|

|

| You put on your cape, readjust the hood, and cross the village. In Castille y León, the villages are much more basic than in Navarre. They appear light in structure, with many brick or adobe houses. The absence of wood and stone made earth the natural building material. In Itero de la Vega there are even bodegas, wine cellars quite present throughout the countryside of Palencia. These cellars built on the sides of the hills, store the local wine in cool underground rooms. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the village, crosses a small country road and flattens on a gravel pathway. Small detail here: the Koreans have very special clothes for the rain. They are often integral suits with sleeves, allowing you to shelter your bag, or not. |

|

|

As soon as the pathway leaves the villages, the Meseta is usually deprived of black poplars and you can see in the bare countryside of the fields that the pathway unfolds very far on the horizon. Everyone will appreciate in their own way this kind of austere stroll in the Tierra de Campos (land of the fields), all this often quite flat region between the Río Pisuerga and Río Cea in Sahagún. It is a vast agricultural area with rivers and canals that irrigate the fields, mainly wheat with vegetable and wine production. There are few trees that offer shade from the relentless sun or cut the terrible wind that blows here in heavy weather.

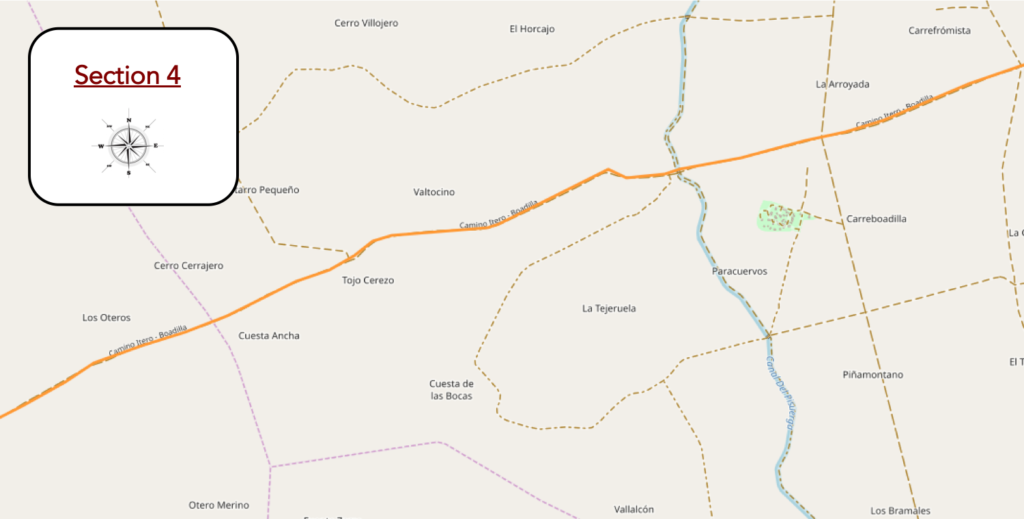

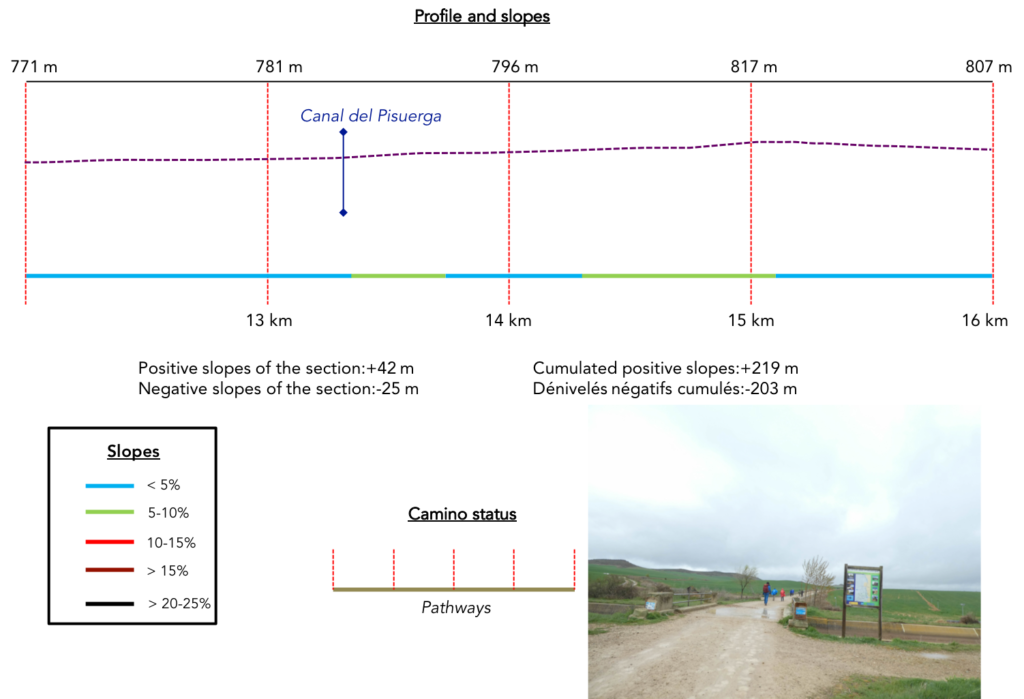

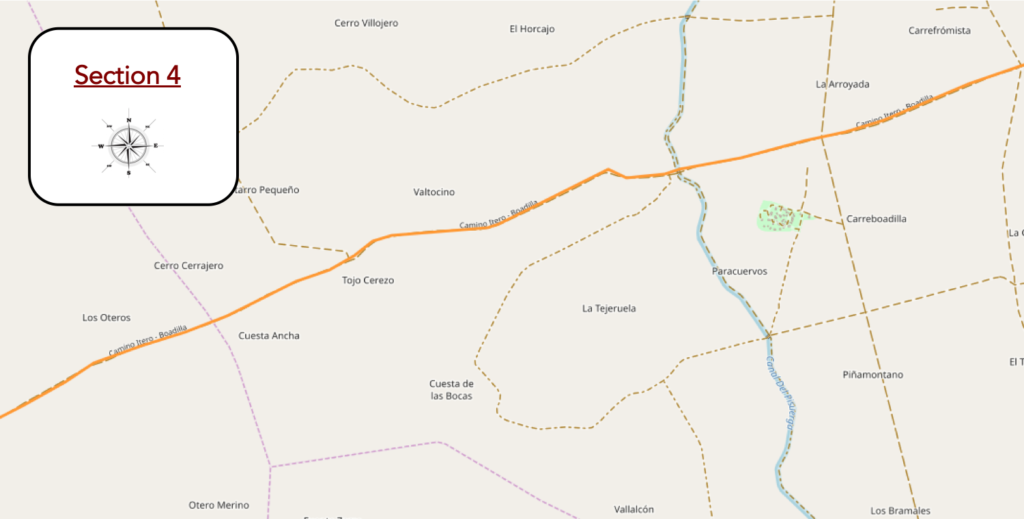

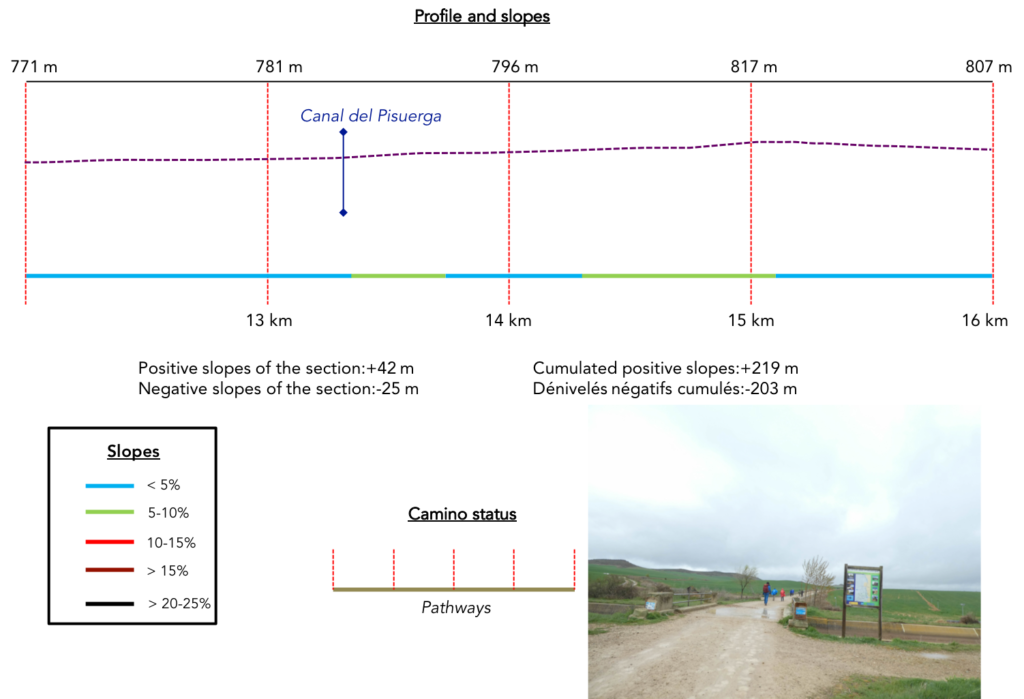

Section 4: A channel to irrigate the fields.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The pathway heads towards the small village of Carreboadilla, but does not go there. Here, you start to find these gigantic articulated arms for the irrigation of fields. Maybe it’s raining less often here, which is not the case today. There are even a few vines, which is rare in the region. |

|

|

| Then, today the rain stops. But the pilgrims do not remove their combination of rain because the rain can come back at any time. Rain coats often also offer protection against the wind, because now gusts over 80 km/ hour are cracking your face, and you have to fight to advance against the wind coming from southwest. |

|

|

| Today, the pilgrims save their saliva, their useless chatter. There’s nothing like rain or gusty winds to make superfluous conversations disappear. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway heads to the canal del Pisuerga. Part of the water was diverted from the river to a canal. The Spaniards have found many ways to irrigate their fields, as water is often lacking in these growing areas (yes!). |

|

|

| Beyond the canal, the wide dirt road climbs gently and for a long time towards a small hill. When you walk, at times on the Camino Francés, you have the feeling of seeing an army in retreat. |

|

|

Here, a German pilgrim returns from Santiago back to his country, with his cart. You heartily applaud. Bravo!

| On this highway where the footsteps of the pilgrims who precede you fade over time in the thick mud, the top of the hill is up there near a small grove. The slope is gentle to get there, along small mounds covered with cypresses, faded brambles and weeds that no longer have their age. |

|

|

| Here, the wind is even stronger than earlier and rushes into the gap that marks the beginning of the descent. We will not have really chosen the good year to walk here in this rotten Easter time. But do we really have the choice when we embark on the road for a month? Be that as it may, Spanish peasants are still less fortunate than us, right? |

|

|

| The descent is not long, and the lying grasses tell you for sure the direction of the wind. In the distance, you can see the village of Boadilla del Camino. It’s flat, infinitely flat, without fantasy. |

|

|

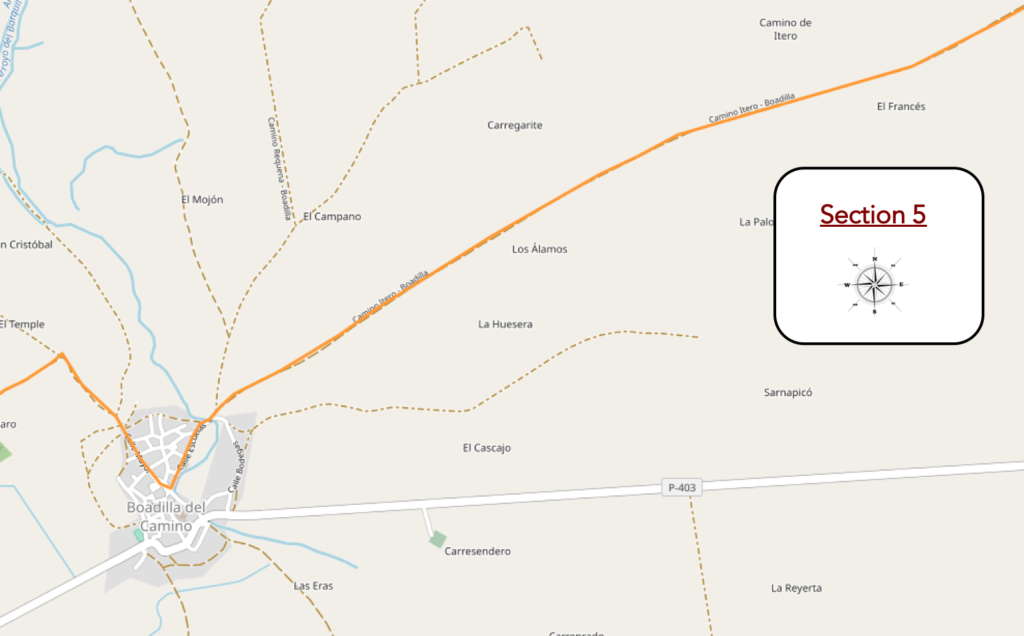

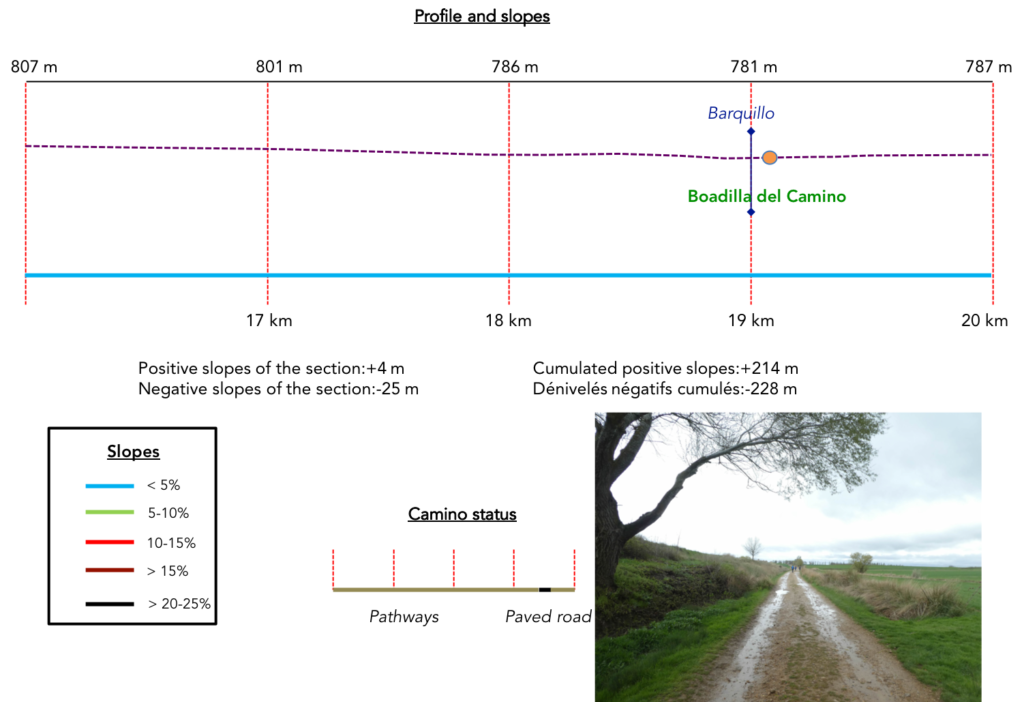

Section 5: In the immeasurable immensity of the Meseta.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The dirt road then travels, tirelessly, for miles fields as vast as the ocean, green as spring, flat, extending to infinity under the gaze. But what have we come to do in this mess? think the less brave. |

|

|

Here, the earth seems more imposing than the cloudy sky that bathes there. No doubt peasants will plant corn here when the land will be less waterlogged. The country opens on a space so big that you feel very small and insignificant beside a universe as vast as one dares to imagine. Only the wind turbines on the horizon take us back a little bit to the scale of men.

| Further afield, the pathway now finds the puddles of water and the black poplars, getting closer to the civilization again. |

|

|

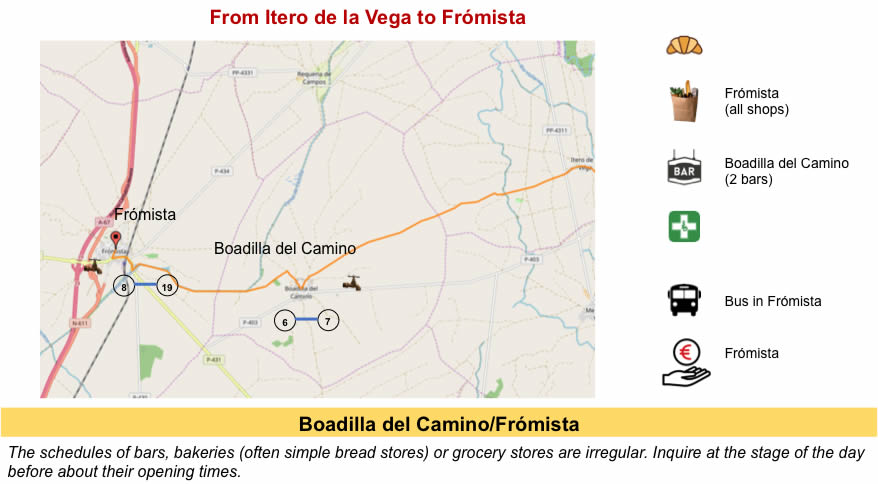

| Much further, the pathway crosses Barquillo brook and gets in Bocadillo del Camino. |

|

|

| As in any self-respecting Spanish village, the church is almost always massive in the middle of the village, behind the red brick houses. The Church of Santa María Assunta dates from the XVIth century. It is known for its exceptional XIVth century Romanesque baptismal fonts, its altarpieces and its altars. But, to see them, the church would still have to be open! |

|

|

| When we passed by here that day, the rain began to increase. Also, we prefer to show you some images of another passage, under the bright sun. It definitely changes the atmosphere. Back to the church |

|

|

|

|

| The period of greatest growth here took place in the XVth and XVIth centuries, when the rollo de justicia, the current church of Santa María Assunta and a hospital for pilgrims were erected. The village was populated when the initial section of the Castilla North Canal was built nearby in the late XVIIth century. Today, everything has melted. The village has only a hundred inhabitants. |

|

|

This is where the famous rollo juridiccional is located, that is to say a jurisprudential column, Gothic, from the XVth century, with motifs of scallops, animals and heads of little angels. It is the richest column in ornamentation of all the rollos in Spain. This work was the symbol of the jurisdictional autonomy granted to the city by King Enrique IV and confirmed by the Catholic Kings Ferdinand and Isabella in 1482. It also marks the place where criminals were chained and subjected to cruel and unusual forms public humiliation before being judged.

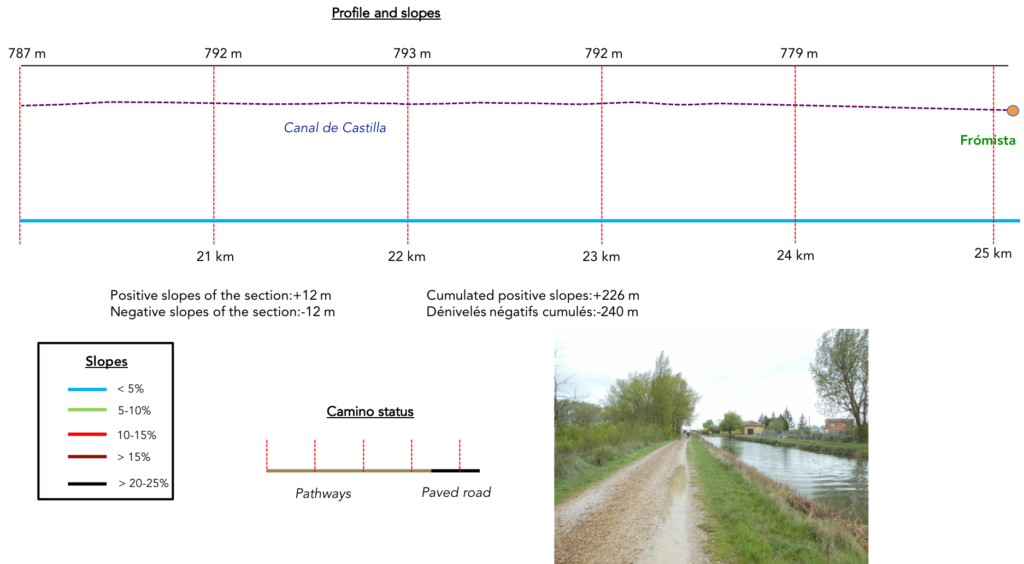

Section 6: Along the Castile Canal to Frómista.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| At the exit of the village, the pathway resumes on a long straight line along an alley of white poplars. It was necessary to vary one day, and forget the black poplars a little. And always the wind which knocks, spurts, contradicts the walk and inflates the cape like a balloon. |

|

|

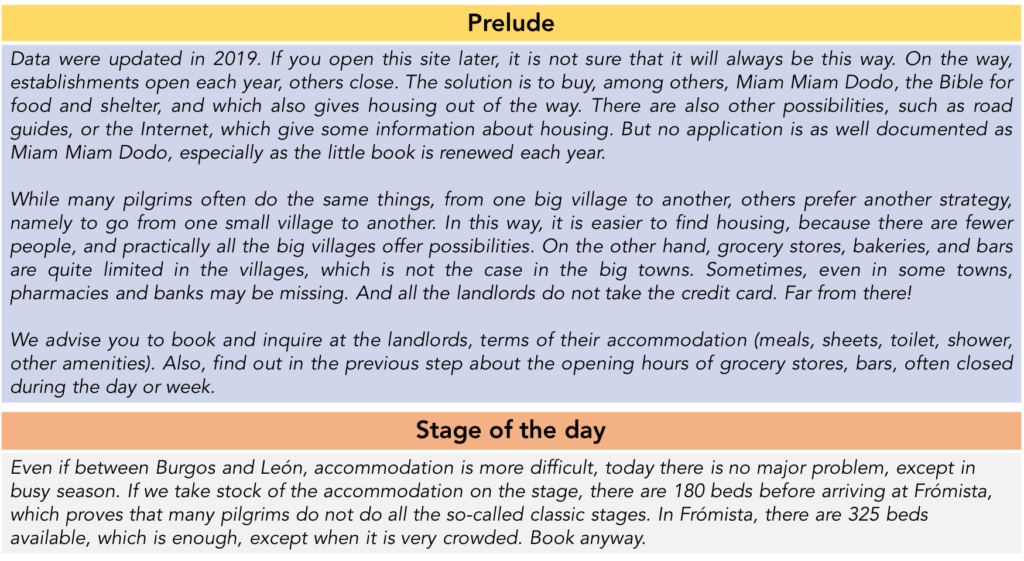

The little game lasts until you reach the Canal de Castille a little further. The Canal de Castille, built in the last half of the XVIIIth century and the first half of the XIXth century, crosses the provinces of Palencia, Burgos, and Valladolid. The canal stretches for 207 km. Here we are on the north branch. While the modern Pisuerga Canal, which you passed through earlier, was designed exclusively for irrigation purposes, the Castile Canal provided transportation for the crops grown as well as the energy needed to turn the corn mills. With the advent of highways, it is now confined to irrigation and recreation. However, there is a project to restore the canal system with its original 50 locks

| The Camino will follow the channel for two good kilometers before getting closer to Frómista. Today, small cruise ships have replaced the wheat boats. |

|

|

| The Camino leaves the canal at the locks. The Castile Canal and a city with history, which dates back well before Franco. Its history begins in the XVIIIth century. It will know its peak between 1850-1860. At that time more than 300 boats crisscrossed the canal for the transport of wheat, mainly. It is a complex arrangement of canals, with many locks. In Frómista, it is a particularly spectacular place. These are the locks N17, 18, 19 and 20, redeeming a height difference of 14 meters, with several branches. This canal seems obsolete nowadays, being used mainly for irrigation and a meager river tourism. |

|

|

| The Camino then heads towards the entrance to Frómista, crossing a large industrial suburb. Now it’s raining in buckets and the wind is blowing hard again, in gusts. It becomes necessary to close the hatches of the pelerine so as not to be submerged. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the road runs under the Palencia-Santander railway line, where trains do not have to run every hour. |

|

|

| The road then reaches the center of a fairly scattered borough (less than 1,000 inhabitants). It is a crossroads on the Palencia-Santander axis, located by the sea. Today, merchants will leave the bocadillos in their box. |

|

|

| It was part of a Benedictine abbey dependent on Carrión, dating back to the XIth century. In 1755, during the terrible earthquake in Lisbon, part of the church was destroyed. The church has since been restored, and this restoration has been contested by many lovers of Roman art who have seen notorious errors in the restoration. Anyway, this building is remarkable. It contains in particular magnificent capitals richly carved and well redone, inside and out. |

|

|

| There are also two other churches in the village, the church of Santa Maria del Castello… |

|

|

| …and above all the XVth century San Pedro church, built in Gothic style, then later transformed. In particular, the front tower, which contains the bells, was added to it. This is the parish church. Here we found the door closed. |

|

|

| To change you from this gloomy weather, here are some images of these monuments under the sun. |

|

|

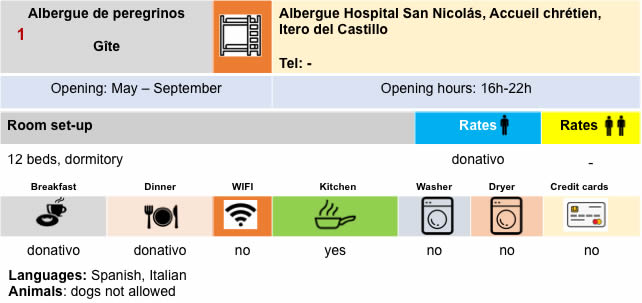

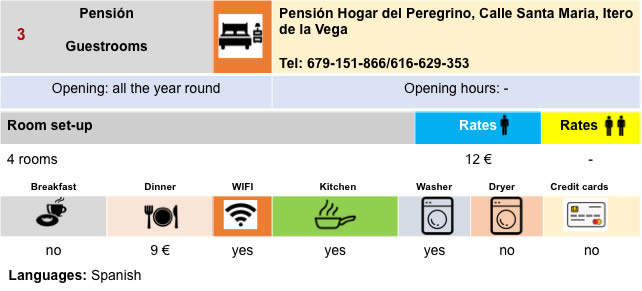

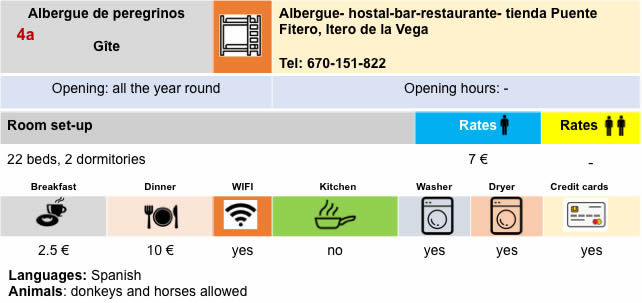

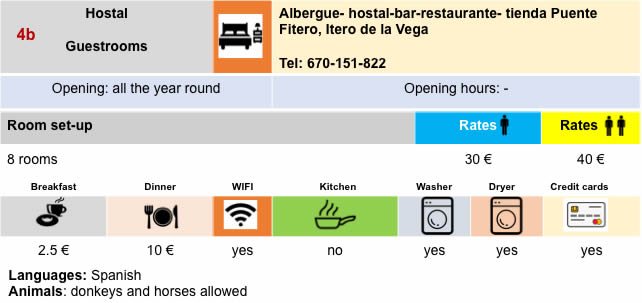

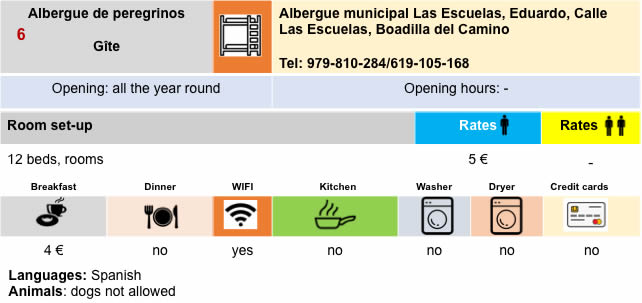

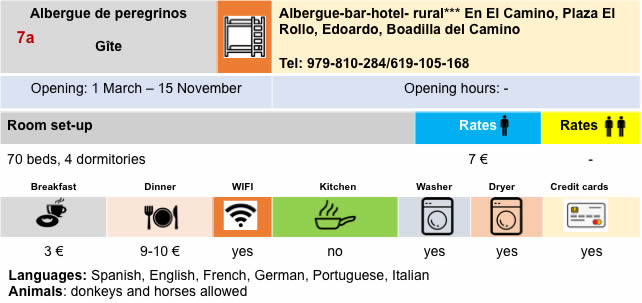

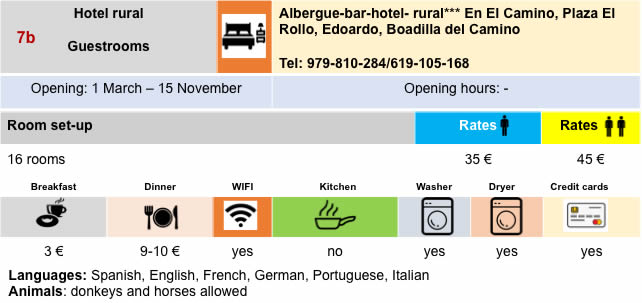

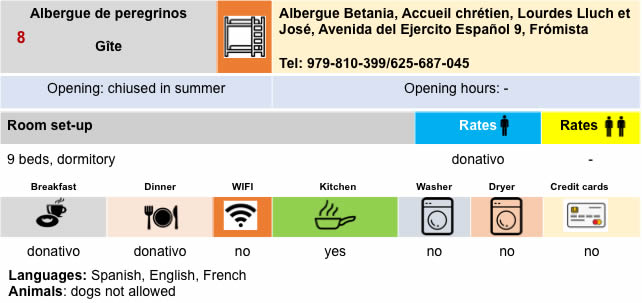

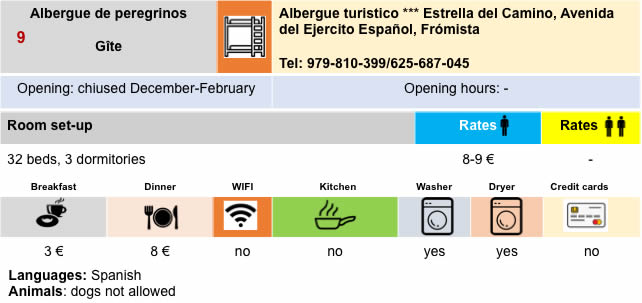

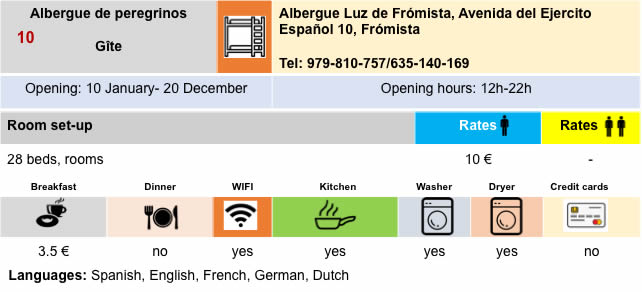

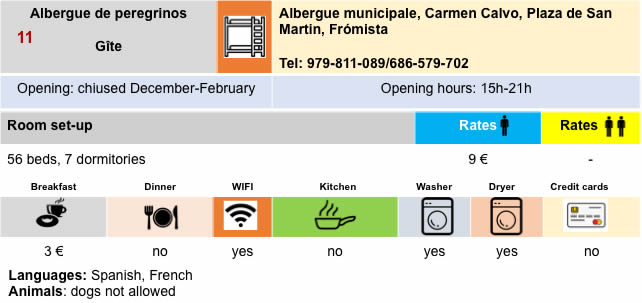

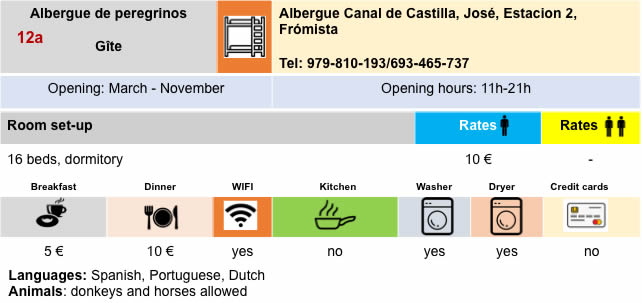

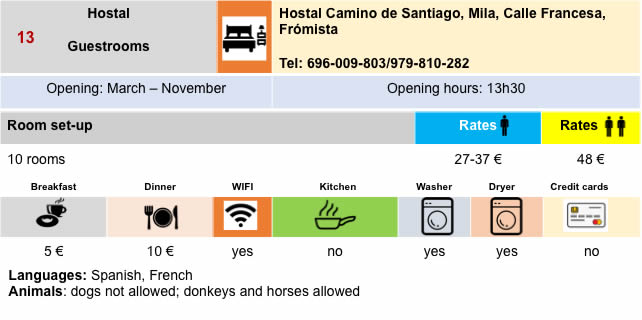

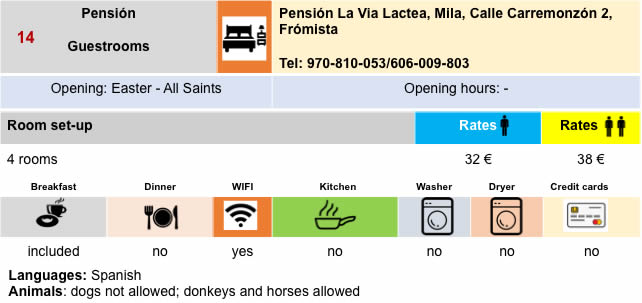

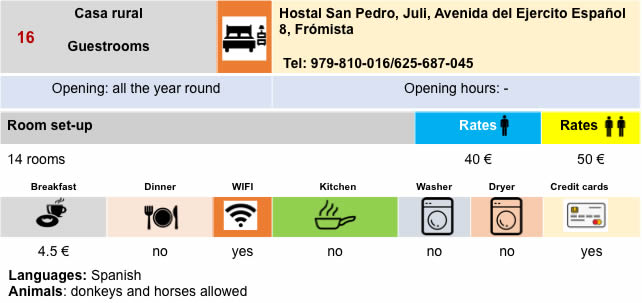

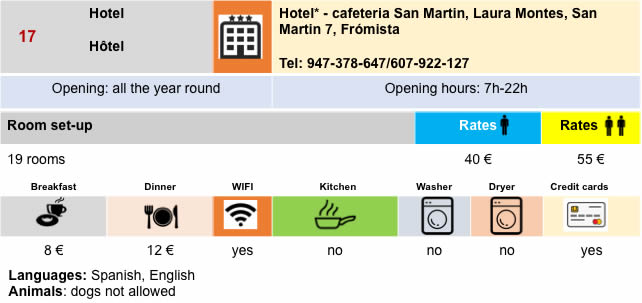

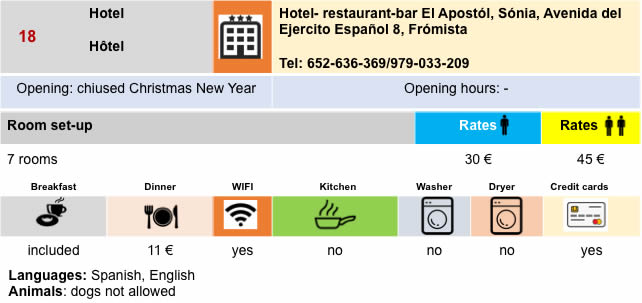

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 16: From Frómista to Carrión de los Condes |

|

|

Back to menu |

As we said above, today the dirt roads have a clear priority:

As we said above, today the dirt roads have a clear priority: