Dear Spanish friends, you are taking matters too far, though

DIDIER HEUMANN, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

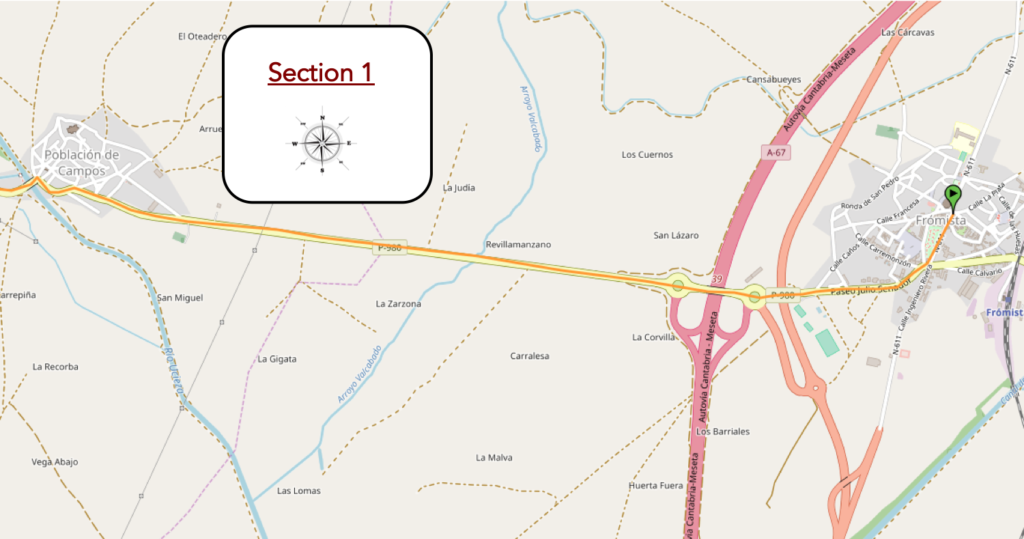

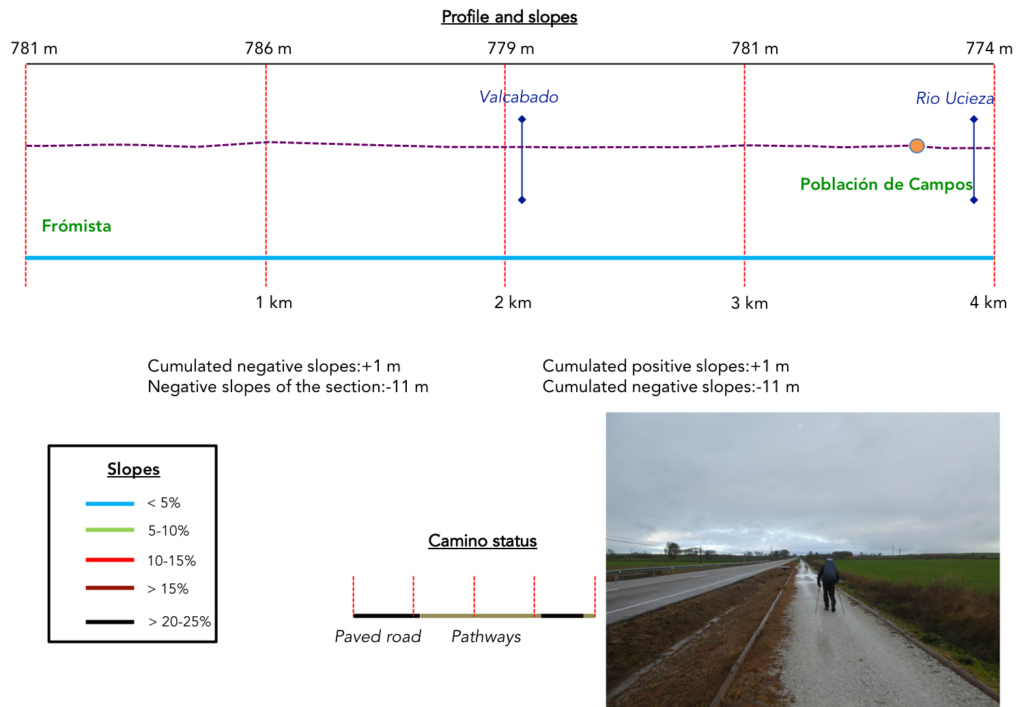

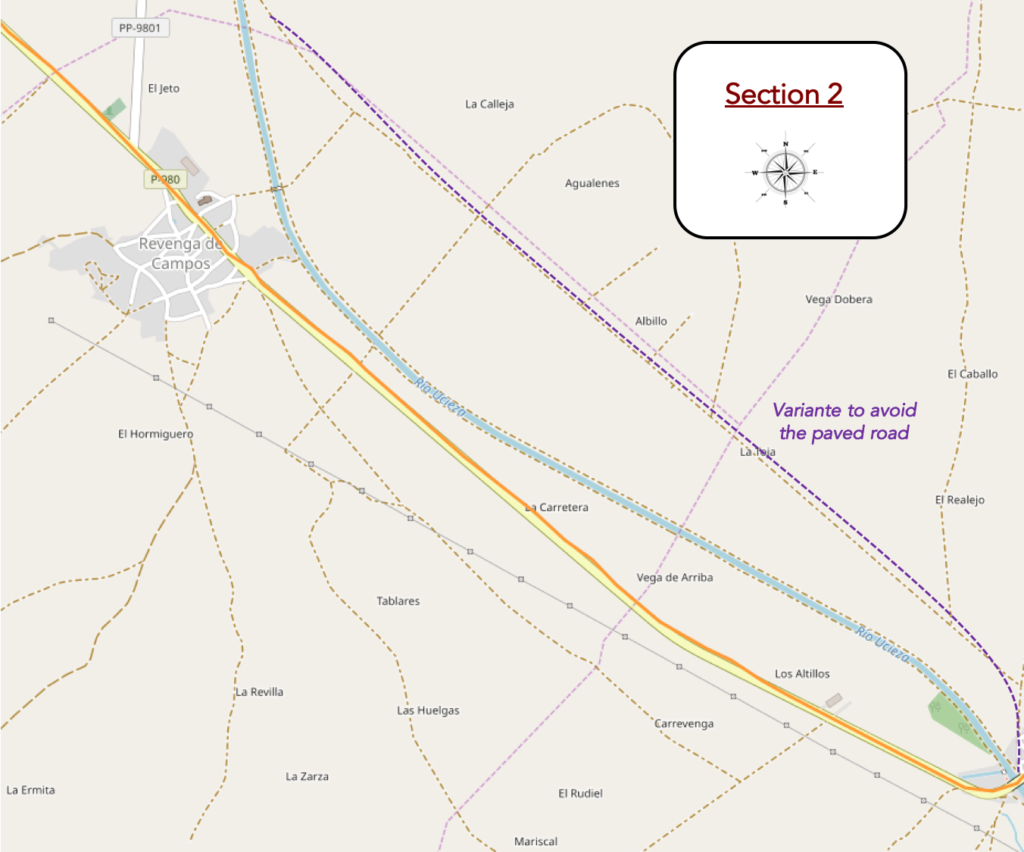

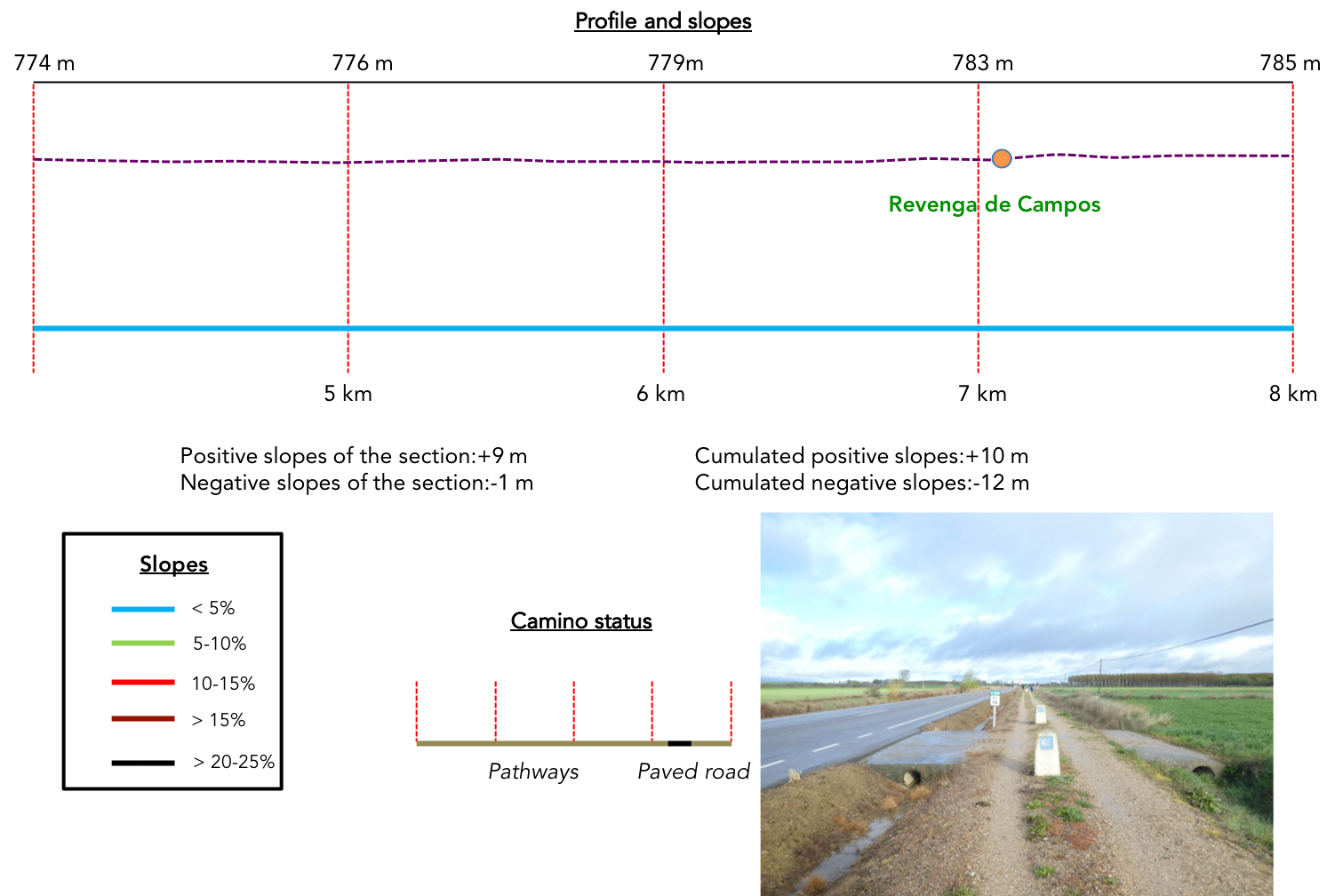

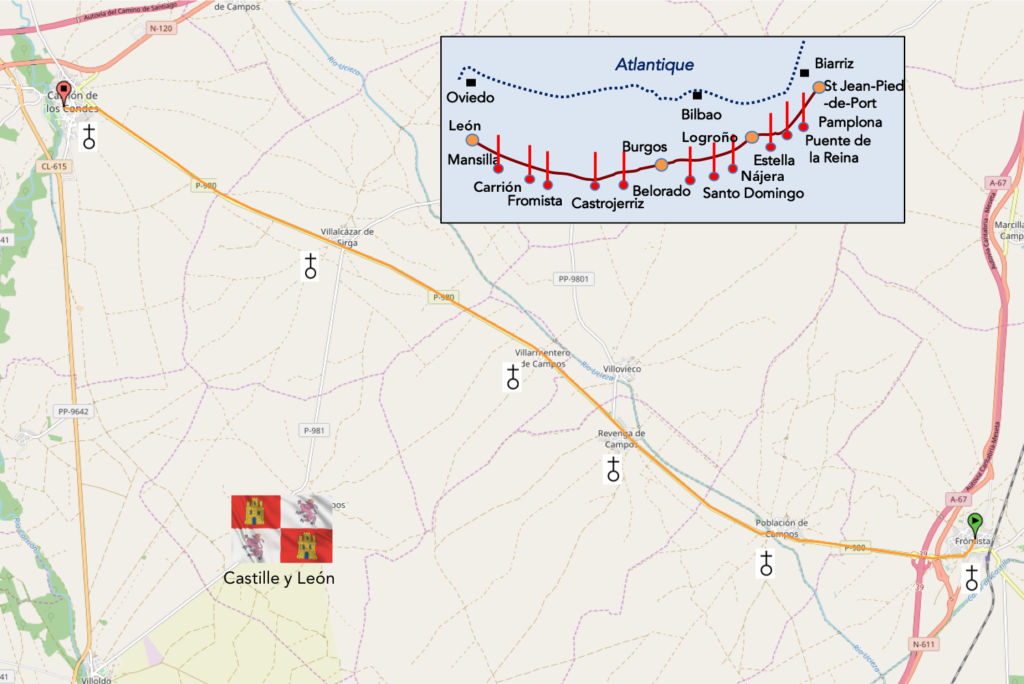

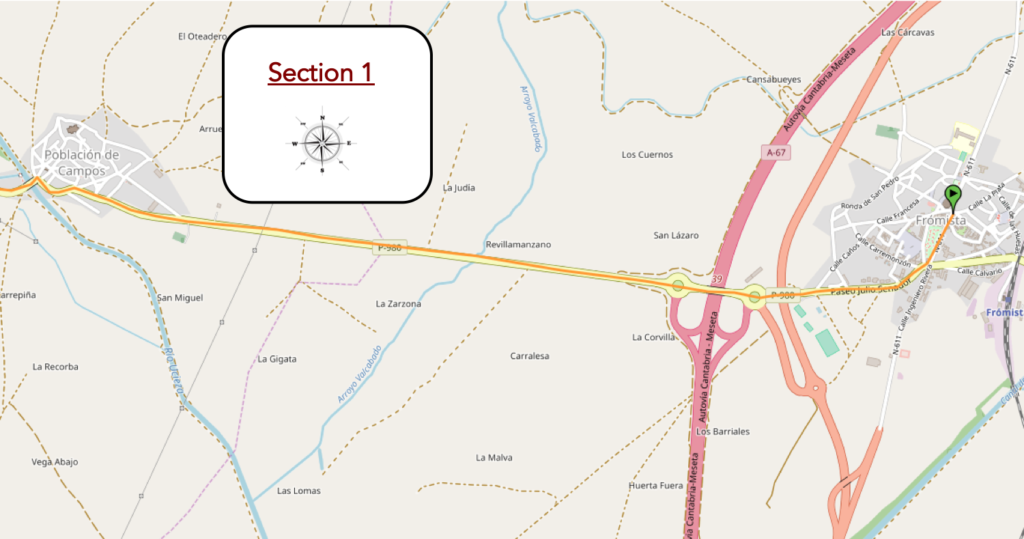

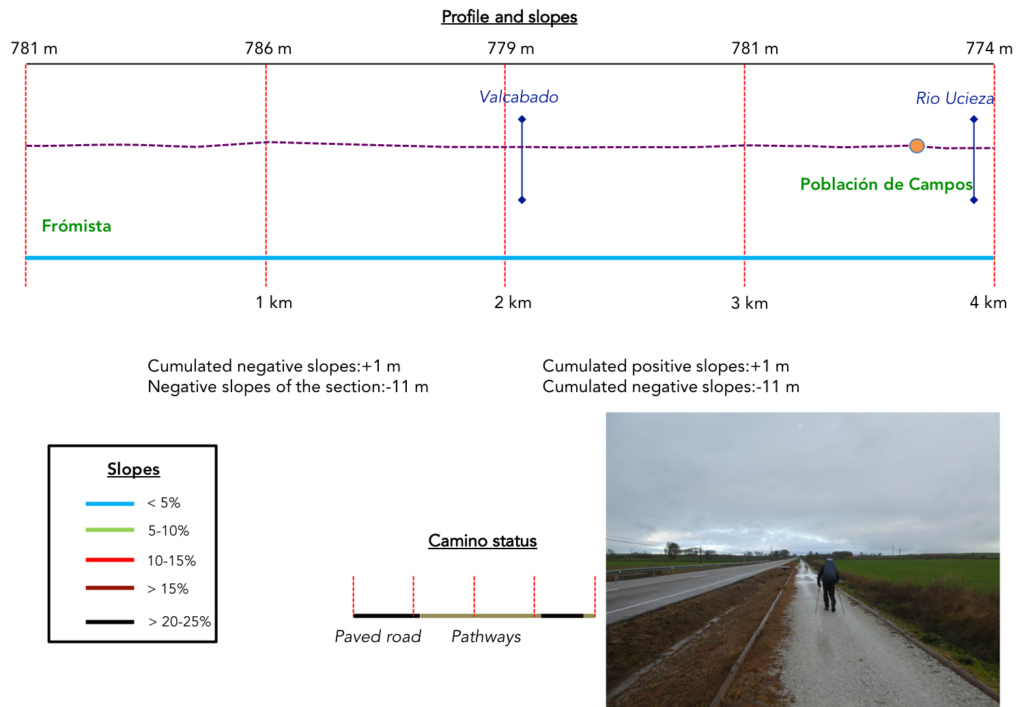

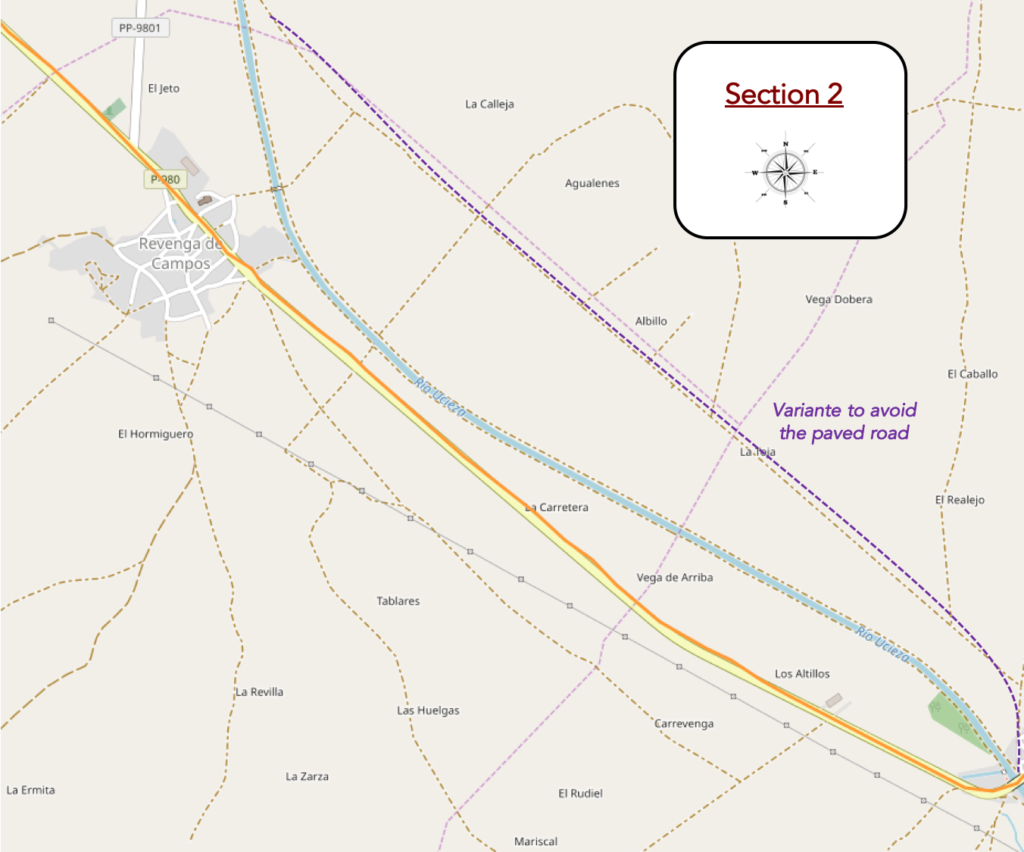

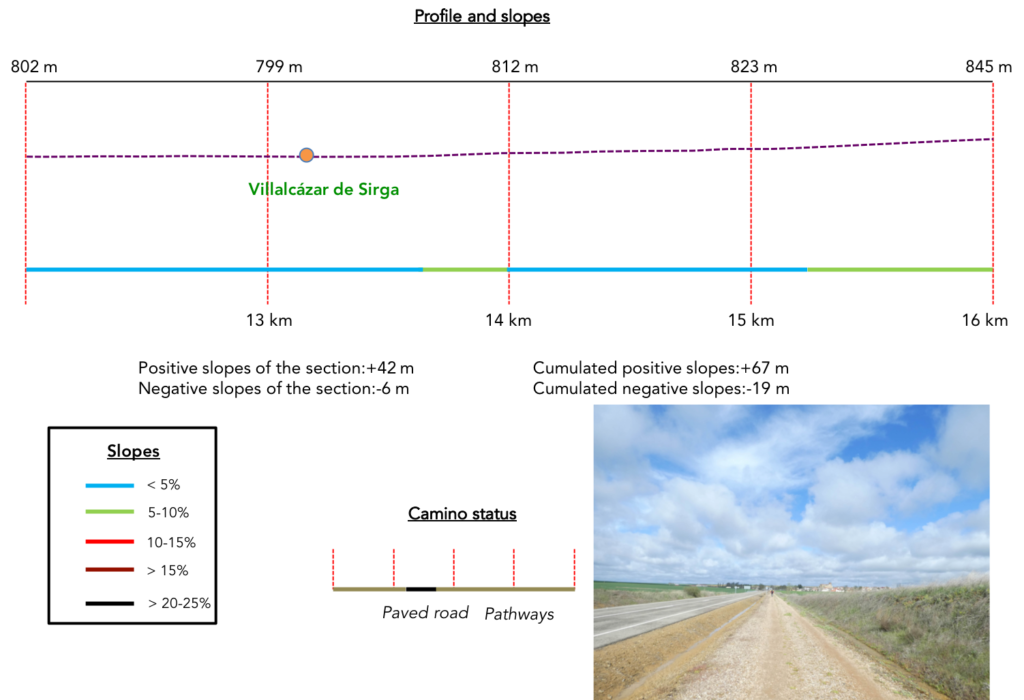

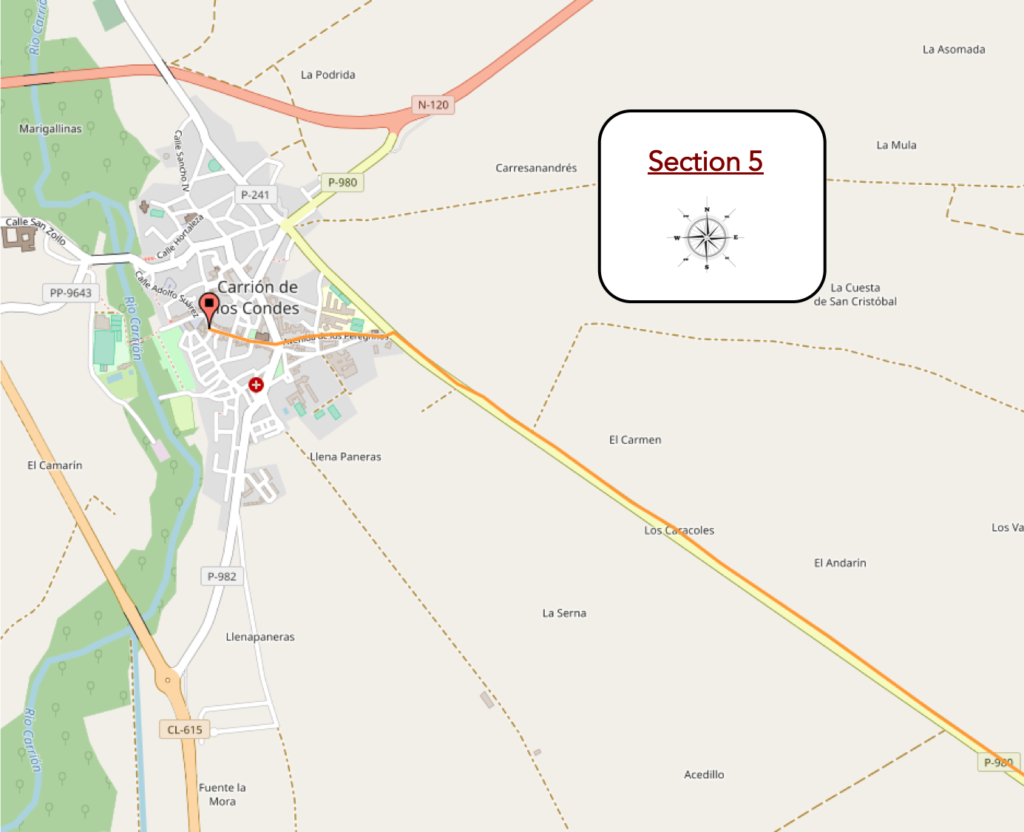

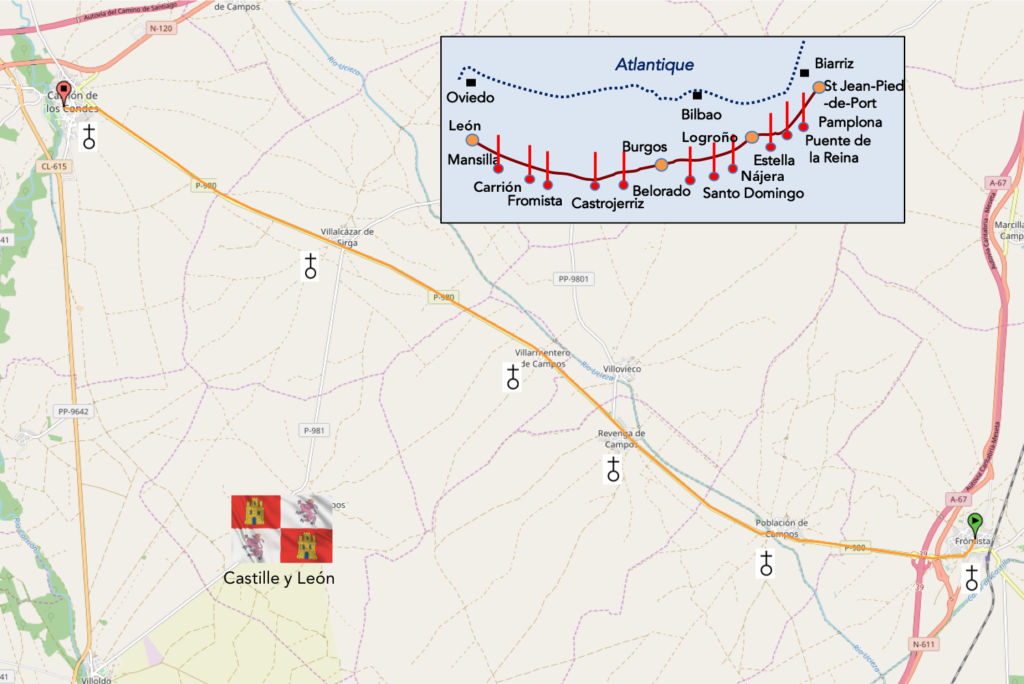

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the Camino. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link :

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-formista-a-carrion-de-los-condes-par-le-camino-frances-33863876

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in Europe without an Internet connection. Therefore, you will find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the title of the book to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Here, the organizers of the Camino have invented a beautiful trickery, to have you believe that the course they have drawn is the “real” Santiago track, the “historic path”. It’s a bit like the pilgrims from the Middle Ages came back to tell the organizers that the track had to be passed two meters from the road. But why then would these nice organizers not have had the idea of drawing the way at least 500 meters from the road? There is really room here. Everyone would have benefited. The course would have remained “historic”, since there is a good chance that the track at all times crossed the Meseta from Burgos to León. But, they would have managed to avoid the pilgrims walking almost all day near the cars, although, it must be said, the traffic is not dizzying on the axis.

Today, you’ll be walking in a region called Tierra de Campos. But why then? Fields, weren’t there before? People of all times have loved to mark their territory. And at the end of the road, there is the capital of these immense fields, Carrión de los Condes, a city with very beautiful monuments. The city has already been celebrated by the Codex Calixtinus Pilgrim Guide as an “excellent city, where bread, meat, wine and all kinds of things abound”. The story begins here when the relics of St Zoilo, a martyr, were brought in for which a large church and monastery were built, some of which are still present today.

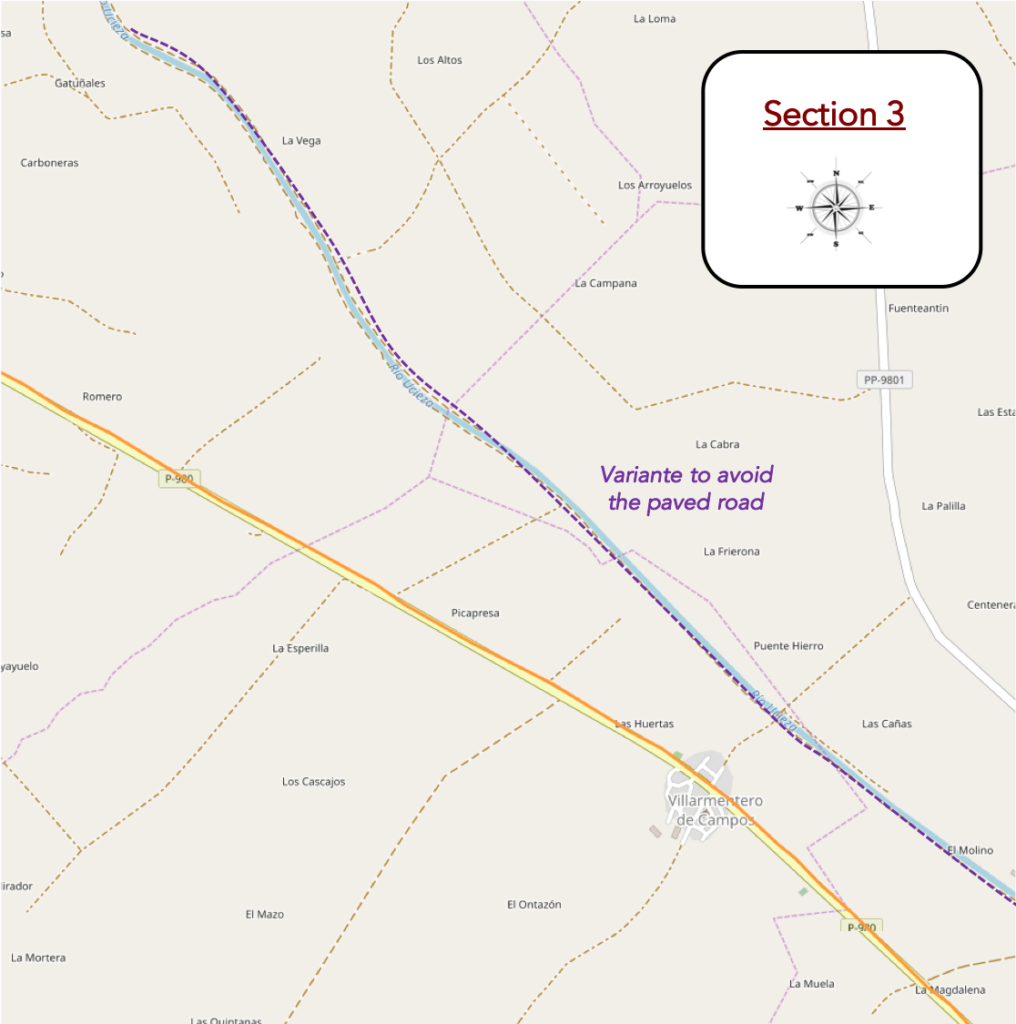

So, this track is called “Ruta Peregrinación” or “Senda de los Peregrinos”, a narrow strip of dirt, gravel, sometimes grass, two meters from the provincial road. But, as it is sometimes necessary to silence the detractors, the organizers also created at one time an alternative to avoid the road, following the Ucieza river for a while. Yet, the alternative, lasts almost 7 kilometers, However, pilgrims have little taste for alternatives, and moreover, they have now grown accustomed to following the roads for a good ten days. When we arrived at the start of the badly signaled alternative, no one decided to follow it. So, as our objective is to describe the route taken by the majority of pilgrims, we stayed on the traditional track.

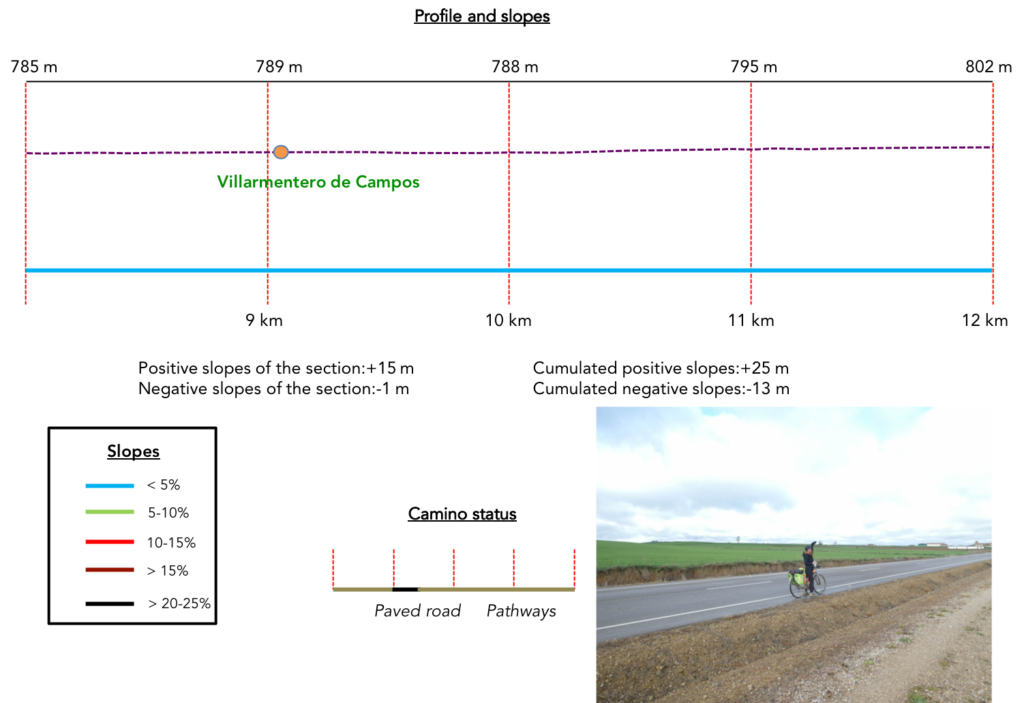

Difficulty of the course: Today’s slope variations (+77 meters/-39 meters) are insignificant. It’s a fully flat stage, without any difficulty.

The pathways, as they will be called, clearly dominate the paved roads:

The pathways, as they will be called, clearly dominate the paved roads:

- Paved roads: 3.8 km

- Dirt roads: 15.2 km

We made it all the way to León in one go, in a cold, rainy spring. From then on, many stages were made on soggy ground, most often in sticky mud.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

Section 1: Full speed ahead on the “Ruta Peregrinación”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| This morning it’s still raining on the Meseta. It has been going on for almost a week now. Admittedly, it often does not rain all day. There are lulls, but the temperature is freezing, well below 10 degrees. The Camino leaves from the crossroads at the entrance to Frómista. Like the day before, bocadillos will not always be served here. |

|

|

| The Camino quickly reaches two roundabouts where the A67 highway runs, the motorway which descends from Cantabria by the sea to Palencia through the Meseta. It is also here that the P-980 departmental road starts which you will follow today. You left the N-120 road, did you really win the change? Here, it is no longer soft rain, but a real blizzard that lashes the faces of pilgrims swaddled under their capes. |

|

|

So here is the landscape of what will be the stage of the day: the “Ruta Peregrinación”, the pilgrimage route, a fairly narrow strip of dirt backed by the road. What happiness to salivate in advance. Carrión de Los Condes is almost straight over there at the end of the straight.

| On the long straight line of 3 kilometers which leads to the next village, the only activity is to put one step in front of the other, to readjust the visor of his dripping hood, or to retain its cloak agitated by a stormy wind. The only fun activity is to note his progress compared to other pilgrims who overtake or catch up with you. And in this exercise, retirees are not the last. |

|

|

| Walk here or there, it doesn’t matter to your legs in fact but to your head yes. It makes the difference. So, you can let the images scroll through your mind, which come and go, or you can focus on the equipment of your peers, compare them at will. What fun, isn’t it? But when you’re bored, you have to invent some games, right? |

|

|

| Much further, the pathway approaches the village. |

|

|

| It soon arrives at Población de los Campos. A small chapel stands here, to the left of the road, but away from the pilgrim route. It seems closed. So why waste your time. Or, go and have breakfast in the rain, in front of the chapel. |

|

|

| “de los Campos”means “fields”. You will not be surprised since you have been crisscrossing the Tierra de Campos and its fields for more than 50 kilometers. No pilgrim stops, in the village it is too early for the coffee break. Here, there is a way to leave the “Ruta Peregrinación”, and to join it later, but apparently no pilgrim considers the detour. And yet, if the organizers had just decided to reverse the two panels, everyone would go through the fields. But there! Europe has invested in making roads and the farmers here must have said to themselves that it was better to let the track pass next to the road to spare their fields. Anyway, with this explanation or another, the traffic on the road is quite ridiculous and the landscape will probably be the same on the detour. The sun appears discreetly. The pilgrims gradually take off their cosmonaut suits. Like what, of course, the saying that claims that the morning rain does not stop the pilgrim, sometimes turns out to be true. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, the Camino crosses the Rio Ucieza on an old bridge in Baroque style from the XVIIth century. The river, calm and placid, flows through the wild grass, under the black poplars, as do all the rivers in the region. |

|

|

The pathway then leaves the village definitively. At the exit of the village stands a crucero (cruceiro in Galician). It is a monument surmounted by a cross above a long stone pillar, a bit like the thin and slender figures of El Greco or Giacometti. They are found in crossroads, villages, cemeteries and many other places. In most cases, their purpose is multipolar, such as obtaining graces, giving thanks for blessings, asking for a healing miracle, or protecting crops or farm animals. But they also fulfilled the mission of guiding pilgrims and identifying the boundaries of parishes and properties. When they have a more jurisdictional function, they are then rollos, as you learnt in the previous stage.

The crucero, especially the Galician cruceiro was probably born in Ireland around the VIth century, on the occasion of the Christianization of Celtic symbols. Then there were illustrations used to educate Christians with scenes from the Bible. Irish pilgrims are believed to have brought this tradition to Galicia via the Camino de Santiago during the XIth and XIIth centuries, although the first ones they built bore little resemblance to those who now populate the Camino, particularly in Galicia where it there are more than 10,000. In Galicia, they represent the Passion of Christ, the expulsion from Paradise, purgatory. Gradually, a platform was developed on which pilgrims could rest at a crossroads. Above the steps, the column can be decorated with motifs related to the Passion of Christ, such as nails, pliers, or references to Adam and Eve or angels. At the top of the column there may be a capital, often decorated with flowers, cherub faces, skulls or acanthus leaves. But, the main part remains the cross. The real birth of the crucero is in the Gothic period.

The crucero is somewhat the equivalent of the Breton calvary. That of Población de Los Campos is very sober.

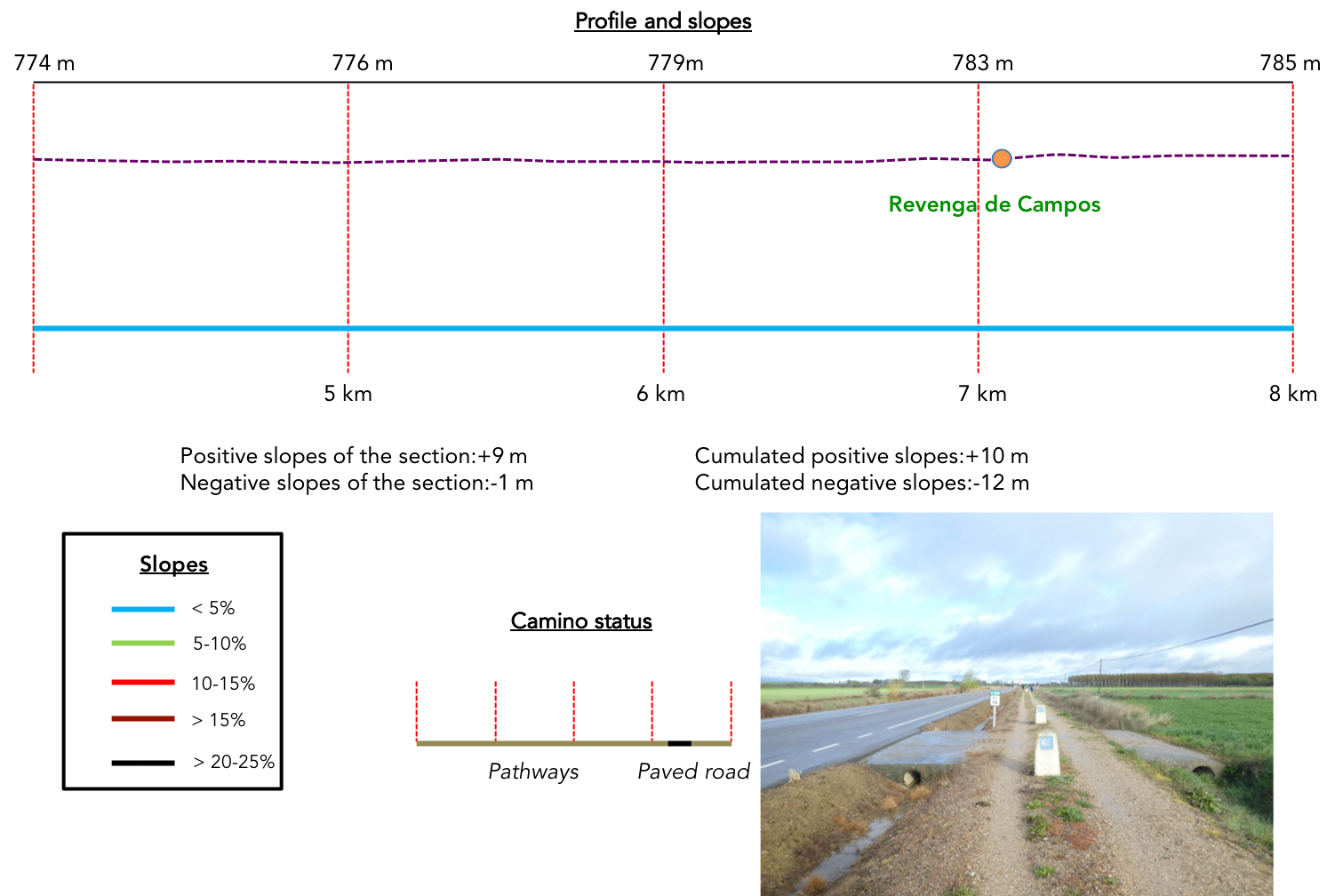

Section 2: From one village to another on the “Ruta Peregrinación”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| And now, luckily, the rain stops and the day finally begins to rise, almost under the sun. The pathway starts again on the “Ruta Peregrinación”, also called “Senda Peregrinación” or “Senda de los Peregrinos”. Few vehicles circulate on the axis, very little, which does not bother the pilgrims in their advance or in their thoughts. On the outskirts of the villages, large hangars that house agricultural machinery are often grouped together. At the beginning of the XXth century, Spain was a mixture of large landowners in the south of the country and a large agricultural proletariat of small and medium landowners in the northern Meseta, which willingly and unwillingly covers half of Spain. Then came Franco and his land reforms. The latter mainly focused on developing the country’s poor irrigation, and not being on the left-wing, favored the development of large estates. There was then a massive rural exodus which increased over the years with companies in the hands of bankers under the laws of market economy |

|

|

| And the pathway again runs along the long straight road across fields. Here, you have the choice of walking on dirt or on grass, everywhere with small water towers, pipes or even drains to store rainwater. And to encourage or discourage the pilgrim, it depends, the milestones remind you throughout the route of the number of kilometers that separate you from Carrión de las Condes |

|

|

| Here, a plantation of black poplars to break the monotony of the fields, one on the right, the other on the left of the road. Black poplar, very resistant to diseases, is used for marquetry, for frameworks, but especially for the manufacture of plywood. This wood also served as a support for the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. |

|

|

| Then, a picnic spot under the willows and black poplars. A rare truck hums past, drowning out the rare chirping of birds or the often-idle discussions of pilgrims. |

|

|

| The pathway gradually approaches Revenga de Campos. |

|

|

| At the entrance to the village are lined up the tractor sheds. Here, when people practice a bit of art, it is still the Camino de Compostela that is involved. |

|

|

| According to history, the village was founded in the Xth century. The name Revenga probably comes from “revenia humeclecense”, meaning a rather humid place. In ancient times it was known as Revenga del Camino. But “del Camino” or “de los Campos”, it doesn’t matter. You then cross a long village, as they all are in the region, with its small square near the traditional church. The Church of San Lorenzo was built in the XIIth century, remodeled in the XVIth century in the Baroque style. Whether it is sometimes opened, we do not know. On the other hand, storks have the right to worship, nesting near the bell tower. In these villages, where the infrastructure is deficient, we hear a van sounding the horn. It delivers food and drinks. The housewives go out to fill their bags and the van continues its concert a little further. |

|

|

| The panels tirelessly indicate the direction of the “Ruta Peregrinación”. At the exit of the village, miracle finally, we feel that the tractors will soon be out. We have not yet come across a single one of these vehicles since our entry into Spain, 15 days ago. Incredible for a region where there is only agriculture, right? But, the weather is rotten this year, we have said it and repeated it many times. |

|

|

| In front of you, the next village on the road is already looming. |

|

|

And always those slender granite cruceros that mark the way, like so many milestones. This one is as simple as the previous one.

Further on, beyond the cemetery, the pathway resumes its ballet with the road, 11 kilometers from the goal. This time, the next village on the road seems closer.

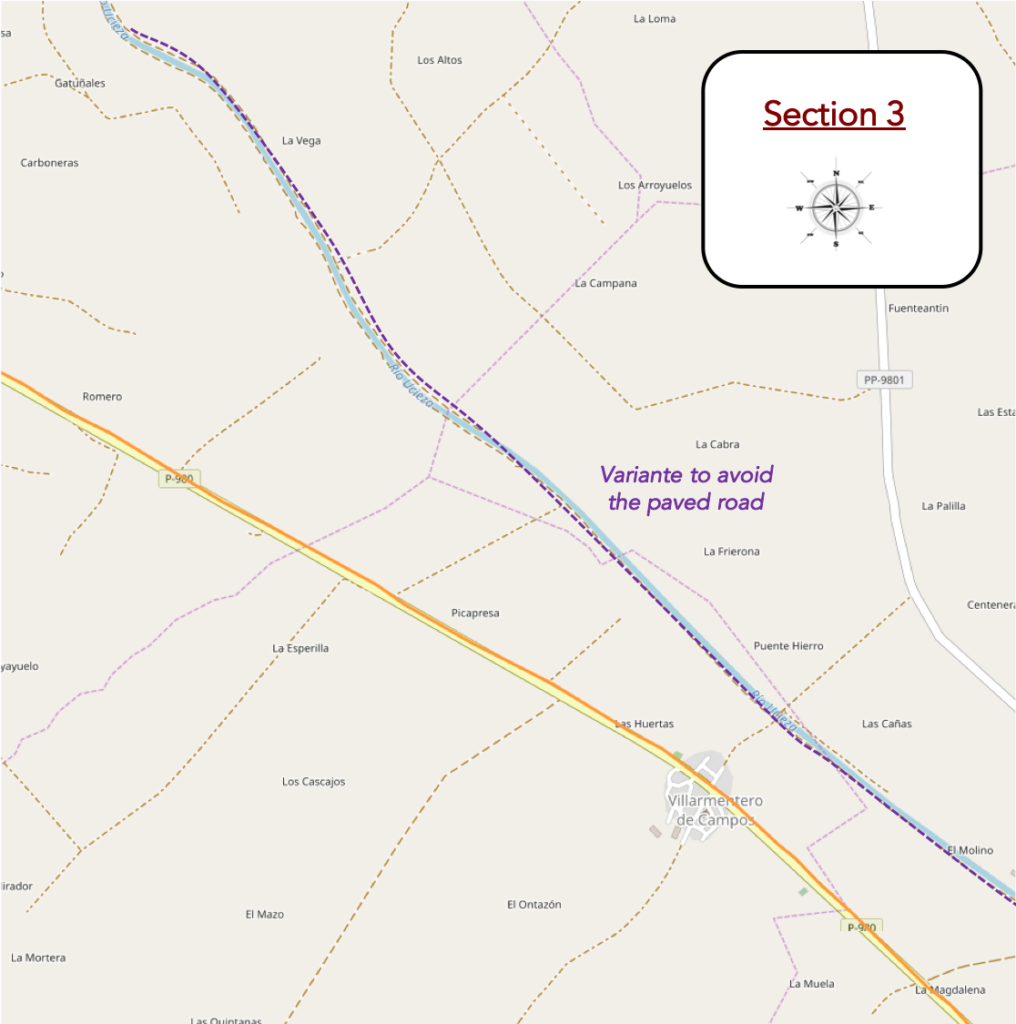

Section 3: A few more kilometers on the “Ruta Peregrinación”.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| And the pathway is getting longer and longer in the monotony of Meseta. Almost never a tree, sometimes a rare vehicle on the paved road. When you walk here in spring, you may think of the suffocating heat which haunts these regions in summer and autumn and which dries up the throats of pilgrims. |

|

|

| Sometimes you take a look around. Here, it is to note that it is still a pilgrim who plays the role of scarecrow under a few rare fruit trees. At the side of the road, a smiling cyclist takes stock of her “roadbook”. She comes from northern Germany. Have a good trip! |

|

|

| In these immense expanses, the gaze is lost, for lack of being able to cling to a precise point. |

|

|

| Yet, the pathway approaches the village of Villarmentero de Campos, by force. The sheds are lined up like sardines at the entrance to the village. Farmers even plant corn around here, which is rare to see in the spring in the Meseta. |

|

|

| So here is the anecdote, at the entrance of the village, the first tractor in activity, observed since our entry into Spain, there are almost 400 kilometers! Champagne! |

|

|

| The pathway crosses a village where there are quite a number of adobe and red brick dwellings. There is not much in the village, but there is still a church, closed of course. |

|

|

| Here, under the umbrella pines, a pilgrim has kept her cape on, sensing that the rain could still fall. Who knows? Long cruceros are present at all village exits in the region. Here, you leave again for a good hour of walking, still in the same monotony, the same destitution until the next village. |

|

|

| Pilgrims also serve as a point of support, allowing them to assess the distances to be covered, their own speed on the way. When you no longer see them, the pathway drags on even longer. “Still 8 kilometers to go, will say the most pessimistic”. “But why didn’t I choose the variant?” others will say. |

|

|

| It’s crazy what a paved road can distort the landscape. Here, without the road, many pilgrims would have found happiness in serenity, like the day before. Today they suffer rather from boredom, from a heavy weariness. |

|

|

| A little further, there are some embankments along the way. Here, the ground is compact clay. Rainwater stagnates in the gutters along the road. |

|

|

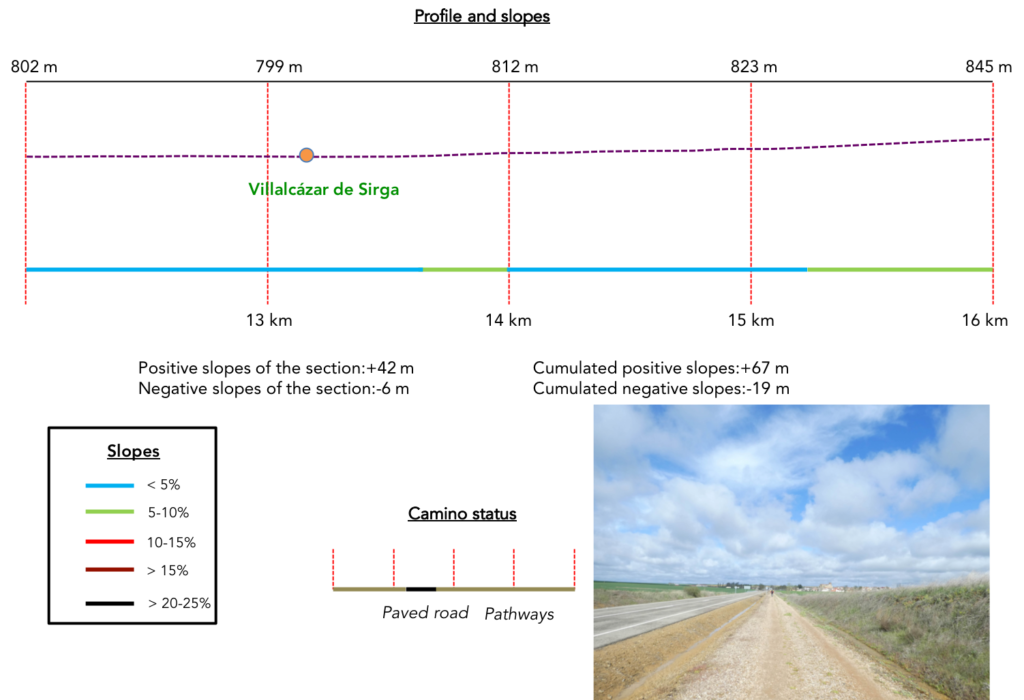

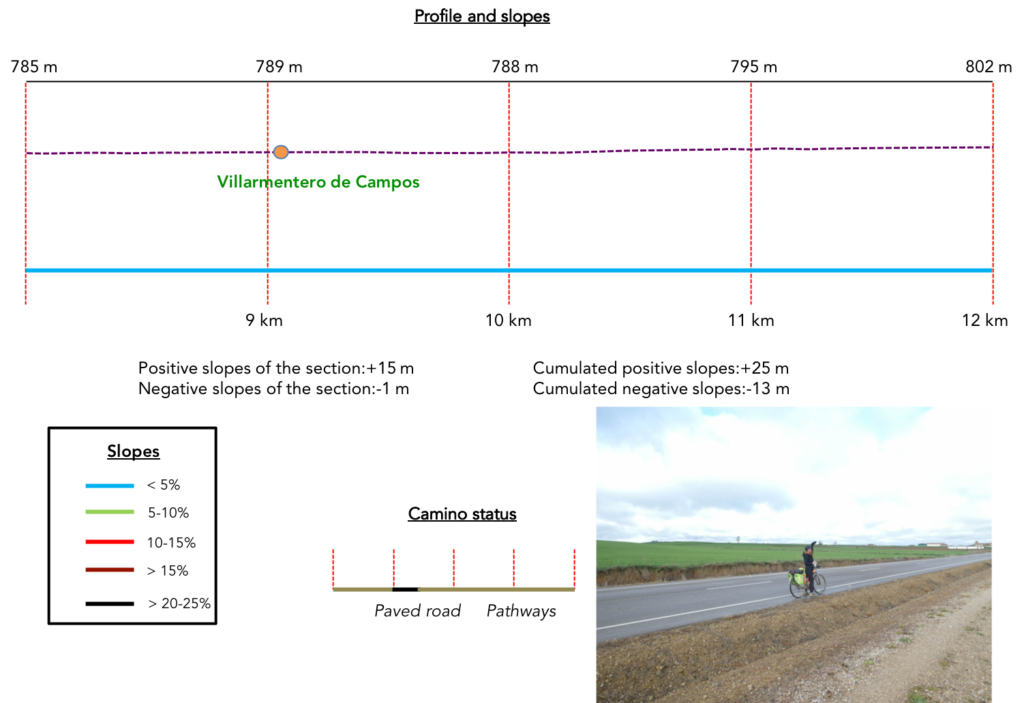

Section 4: Via the very beautiful church of Villalcázar de Sirga.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| There are hardly any turns in the way. It’s straight, hopelessly straight and flat. However, in the countryside, there are sometimes slight undulations. |

|

|

| Approaching Villalcázar de Sirga the massive silhouette of a church, let’s say a cathedral, stands out above the village. This is the Church of Santa María la Blanca.

The origin of the village dates back to Roman times. Formerly, the city was called Villasirga. The name derives from the Latin name villa (villa, place) and from the Spanish sirga (towing path), referring to an ancient Visigoth road that crossed the city. Then, at the beginning of the XIIth century, the Templars on their return from Jerusalem, with the help of the Cistercians, began to build what was to be a great fortress for the defense of Castilla y León in the Middle Ages. The fortress was completed at the end of the XIIth century and became the residence and logistics center of the Templars. This fortress extended to the north of the church. It gradually disappeared over the centuries.

In the XIIIth century, the Camino was diverted to pass through here, as people began to speak more and more of the miracles performed by the Virgen Blanca. The name Villasirga will remain until the middle of the XVth century, when people began to call the city Villa Alcázar (the last part of the Arabic Quars, meaning castle or fortress) then Villalcázar de Sirga because of the aspect of the fortified church of the Templars. Today, mail and documents use Villalcázar de Sirga, and the shorter Villasigra is the most common popular usage. With the disappearance of the Templars at the beginning of the XIVth century, the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem took over, caring in particular for pilgrims and the sick in their hospitals and hospices. |

|

|

The pathway arrives at the village, then continues straight without passing by the church, which is located a little up at the top of the village, 200 meters from the pathway. But the vast majority of pilgrims go straight ahead, including Europeans. But why the hell, or rather the good Lord, do we continue to call the Camino the Pilgrims’ Way? There are soon no more pilgrims on the way, only hikers. We often repeat it, off and on: everyone makes the journey in their own way. You can go to a church to pray, to contemplate the old walls or simply to meditate, to be silent for a moment. But, the track, we should rather call it “the Way”, as the Americans say. No American (or very few) stops here to contemplate this marvel, one of the most beautiful churches in Spain. Certainly, in their country, there are only minimalist churches, most of them without a soul. But their ancestors may have contributed part of their lives to building the cathedrals in Europe. But Americans don’t care. They pass straight by, talking loudly, as usual. It’s their way of life. They hurry to arrive in Santiago, and later be able to say to their friends: “The Way, I did it.” So why are the Koreans stopping? Because Koreans are Asians and these people are curious about everything. Moreover, many Koreans are Catholics, but the statistics do not say how many Catholics there are among the Korean pilgrims.

Colossal, imposing, National Monument since 1919, built between the XIIth and XIIIth centuries by order of the Order of the Temple, it is one of the most remarkable points of the Way of Santiago de Compostela, which has diverted its route original to pass in front of this marvel of religious architecture, with Romanesque traces, but especially of Gothic style. The Church of Santa María la Blanca is an example of the transition from ogival Romanesque to Gothic. The Templars actually built a fortified church, taking the form of a Latin cross, with a double transept. Throughout this region where the limestone outcrops, the churches are most often made of large blocks of ocher molasse, or even sometimes of compact bricks. The church had twin towers at the ends of the main transept, one of the towers of which is still partly in place. Its austere exterior gives it certain aspects of an alcazar (fortress, castle). In the XIVth century, some extensions and additions were made, including chapels. The huge church we see today is what remains of a much larger building, which was damaged by the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 and by Napoleon’s troops during the Napoleonic Wars. The church is now about 25% smaller than it was in the 17th century. The church has lost 9 meters of its length, including what was the main facade, with the Puerta del Ángel, a sculptural jewel worthy of a cathedral and praised by ancient travelers and pilgrims. Also lost in this collapse, the choir, and the atrium with its narthex, and the twin towers. But, there are still beautiful wonders of this church.

| The south door is distinguished by its large rose window and the access covered by a portico. It is the most beautiful of all the entrances to the temple. The doorway is flanked by six archivolts decorated with 51 13th-century sculptures depicting different religious figures, such as angels and saints. Above there are two friezes. The lower part is dedicated to the White Virgin and decorated with figures that refer to the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi. In the upper part, we can see the Pantocrator, accompanied by the evangelists and the apostles. There is a legend that says that on the day of the spring equinox, when the sun shines on the figure of the bull (Luke) next to Christ and coincides with the mouths of the two heads that appear in the same frieze, one then has the direction of the exact location of a treasure hidden by the Templars. Many detectives have tried. But in vain. It’s a bit like The Da Vinci Code, with Spanish sauce. |

|

|

|

|

| You can take a tour of this wonder. It is still as imposing, monumental, luminous. |

|

|

| Inside, you notice the height of its vaults and the light that penetrates through the rose window, as well as the richness of its sculptural and pictorial pieces. The arches and vaults signify the late Romanesque style, when the vaults gradually took on a slightly more ogival shape. The capitals and stained-glass windows are discreet. The naves are high, tight, ocher and bright. In the church, gold and bronze, which the Spaniards love, have been kept to a minimum. The Chapel of Santiago houses 3 magnificent Gothic tombs, where knights of the Order were buried, including the Infante Filipe of Castile and his wife and Juan Perez, the last of the master Templars of Villasirga. |

|

|

|

|

| The Camino crosses the village at the side of the road. Here comes the variant that cut across fields. Here, a second tractor in the village. It activates, doesn’t it? What is it doing? He weighs his load at the public weight, which is often found at the exit of villages. Perhaps it belongs to a cooperative where everything is weighed, both at the entrance and at the exit. |

|

|

| At the end of the village, you are 6 kilometers to the end of the stage, much further to Santiago. But the scenery hardly changes. It’s always a long straight line that you never see the end of, in the middle of waiting cereals and cornfields. Like every day, in the spring, the density of pilgrims thins out at the end of the stage. There are those who left early and who have already returned to the “albergue“.There are those who dawdle along the way. Later, when there are more than 1,000 on the way, you can sometimes observe real trains of pilgrims. |

|

|

| Between km 6 and km 4, nothing happened. But no! Two cars have passed here and the pilgrim will have walked another half hour in languid monotony. |

|

|

Come on! It is unlikely that anything will change during the next few kilometers. Just focus on the stamped terminals of the shell. Yet everything remains silent, mute. A few trees on the horizon, but not a patch of shade.

| Further on, the pathway undulates slightly between very low altitude hills, a bit like a pleated tablecloth stretched over the table of the universe. |

|

|

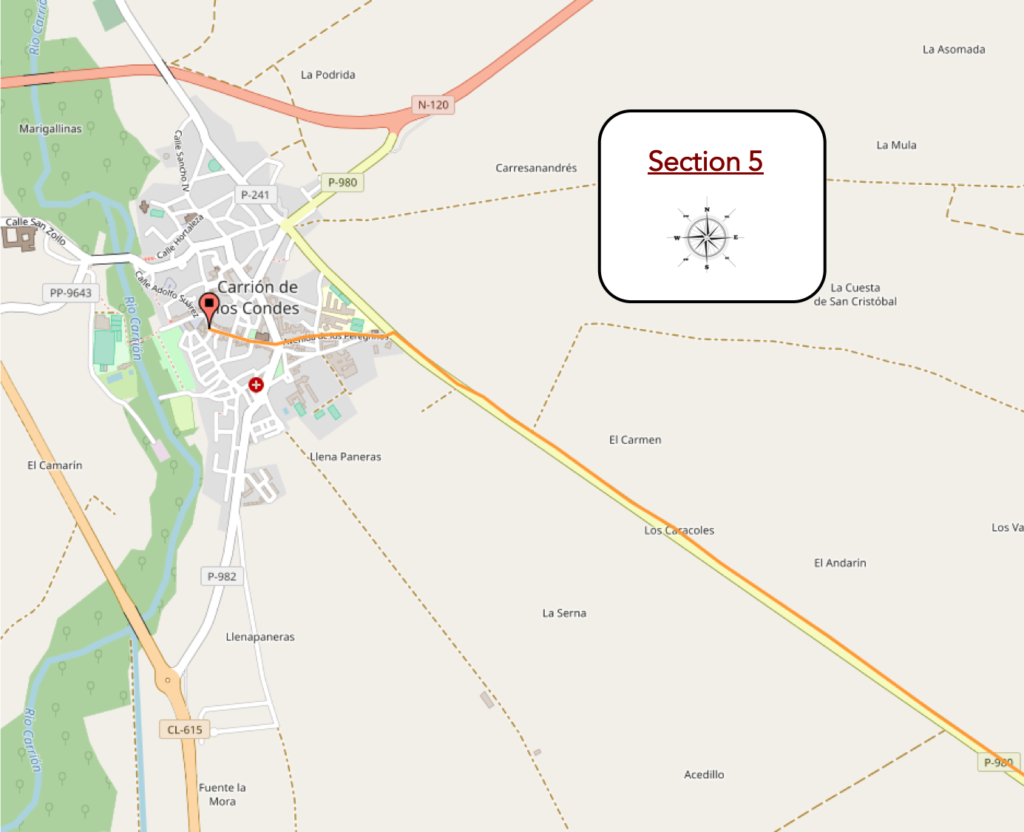

Section 6: Fortunately, there is a beautiful small town at the end of the road.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| The Santiago track is not a fashion show, but sometimes the multicolored outfits of pilgrims brighten up the austere universe somewhat. Here is the final stretch before the end of the stage. |

|

|

| It seems so close. However, there is still 2 kilometers of walking. On the rectilinear roads, time always passes at the slowness of the snail. There are couples who walk together, in apparent harmony. There are unconditional loners. Then, there are all these pilgrims who invent families, who go a long way together, find themselves in the same “albergue”, then dissociate, to perhaps find themselves further. For one reason or another it is necessary to separate one day. You have then to get used to walking alone. |

|

|

|

|

| The Camino then arrives at Carrión de los Condes (2,000 inhabitants), a small town quite rich in monuments where Romanesque and Gothic mingle, located in the fertile valley of the Río Carrión. This region was first inhabited by Celts and Greeks, some of whom came from the province of Caria in Asia Minor and named the place Carrión in memory of their homeland. Then it was the Romans and the Visigoths. The Muslims invaded the region in the XVIIIth century, then they were driven out by the Reconquista. Then, the place took the name of Santa María de la Victoria, because the Christians had built there a church dedicated to the Virgen de las Victorias. In the XI1th century, it took the name of Santa María de Carrión, combining the reference to the Virgin and the primitive foundation of the city. The name Carrión de los Condes (of the counts) only appears in the XVth century, underlining the fact that the square was the seat of a family of very influential counts. It is said that at that time the town had more than 10,000 inhabitants. The Codex Calixtinus said it was “rich in bread and wine”. It was a walled city and once had 12 churches and 14 pilgrim hospitals. It was effectively the capital of much of the Tierra de Campos region and from the XIth century was ruled by the powerful Leonese Beni-Gómez family, the Counts of Carrión

The place assumed for centuries a defensive role to protect León. The local potentates erected in the XIth century the magnificent monastery of San Zoilo, a Cluniac monastery, which for a long time had a great influence in these peasant lands. The passage of pilgrims favored the development of the town, which became very prosperous. If this track in the Meseta has been made a “historic track”, there are many current reasons for this state of affairs. Then over the centuries, the locality lost its splendor, but there is still a medieval atmosphere here in the old town. |

|

|

| You enter the small town from the side of the monastery of Santa Clara, dating from the XIIth century, restored in the XVIIth century, with its Renaissance style facade. We found door closed here as well as at the adjacent museum which houses nativity scenes from all over the world. |

|

|

| There are still some traces of the medieval walls at the entrance to the old town. In the long street that crisscrosses the entire town, it is not the signs of pilgrimage that are lacking. Does this Martian outfit really make you want to start the Camino Francés? |

|

|

Here, even the door handles sing a familiar refrain.

| Near a square at the beginning of the town the church of Santa Maria del Camino or de la Victoria. |

|

|

| Many Spaniards on organized trips stop here. The parish church of Santa María del Camino is the oldest church currently preserved in Carrión de los Condes. It is in Romanesque style from the middle of the XIIth century. However, some historians believe that the construction of the Church of Santa María began at the beginning of the IXth century, on the remains of a Byzantine chapel. It was originally called Santa María de las Victorias, because of the victory over the Moors, and later Santa María del Camino because pilgrims passed by it on the Camino. Since then, it has had both names. |

|

|

| The main portal, decorated with bulls and everyday scenes, is supported by flying buttresses under a canopy where pilgrims were told the details of the sculptures. In the portico stand out the adoration of the Magi, the figures of Samson and Charlemagne, and many other characters. Inside, too, the existing capitals are decorated with human figures and fantastic animals. It is a rather exceptional monument. |

|

|

| The interior is bare, under its Romanesque vaults, its bays, its barrel vault and its slightly broken arches, which is all the charm and depth of Romanesque churches. There is little Gothic or Baroque, except for the altar and the sacristy. Here, they still say mass. |

|

|

Further on, you’ll find the Plaza Mayor, with its small arcades, its town hall and its supermarket. It is a beautiful and large square which testifies to the importance of the borough, an obvious contrast to what is found in the other villages of the region.

| In the square stands the Church of Santiago, which was built in the middle of the XIIth century in Romanesque style. It was part of a disappeared monastic complex and initially adjoined the primitive wall of the city. The church was destroyed by the explosion of a powder keg during the War of Independence in the XIXth century, but fortunately leaving intact the magnificent west facade and its frieze, classified as a national monument. The church was then rebuilt using the original materials but reducing the size. The tower was rebuilt in Moorish style. |

|

|

The frieze summarizes the Apocalyptic Revelation of John the Evangelist on Patmos, with Christ and his apostles. This frieze is considered one of the most remarkable works of late Romanesque art in the Iberian Peninsula.

| The capitals are also exceptionally well preserved. |

|

|

| Attached to the church, there is a small museum of Sacred Arts. |

|

|

| Some pilgrims may appreciate the old chasubles, the old church desks, the old harmonium or the somewhat kitsch statues representing the saints or the Virgin. |

|

|

| There are still many churches to the north of the town overlooking the river, including the Church of San Andres, known as the “Cathedral of Carrión de Los Condes”, a massive XVIth century church, which is said in guidebooks to be the he interior is majestic. We found closed door, like next door, at the hermitage of La Cruz, a XVIIth century building, belonging to the brotherhood that stores the icons and organizes the processions of Holy Week. |

|

|

| No more open was the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Belen, a XVth century building, which from the top of the hill overlooks the river and San Zoilo. This is where the faithful come every December 13 to kiss the wood carving of Saint Lucia. Nowadays, a good half of the churches in Europe are closed and they are only opened to individuals or for specific reasons. Gone are the days when churches were synonymous with hospitality. |

|

< |

| To reach San Zolio, you have to cross over a bridge originally dating back to the XIth century, the Rio Carrión, a tributary of the Rio Pisuerga, which we met in the previous stage. This is where pilgrims will pass to continue the Camino. |

|

|

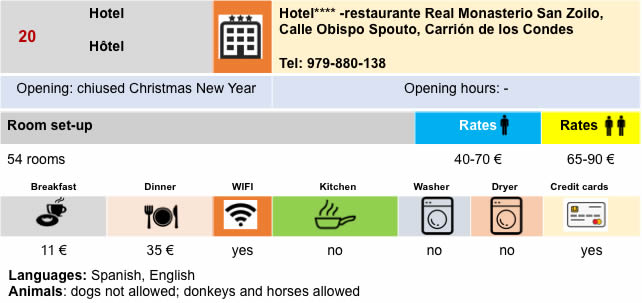

Near the medieval bridge stands the monumental monastery of San Zoilo, an ancient refuge for pilgrims whose initial construction dates back to the Xth century, with the arrival here of the relics of Zan Zoilo and which were ceded to the order of Cluny in the XIth century. From this period remains a window. It also served at one time as a royal residence and over time became a pilgrimage inn. The monastery separated from the Cluniacs to become a Benedictine monastery in the XVth century. The Dominicans destroyed the old cloister to build the new one, in the Renaissance style, which is still relevant today. Then the building was gradually amended between the XVIth century and the XIXth century. Then, in the XIXth century, the Jesuits, the new owners, made it a college. The building has therefore known during its history three major religious orders. Today, you no longer visit the church, but the cloister is accessible.

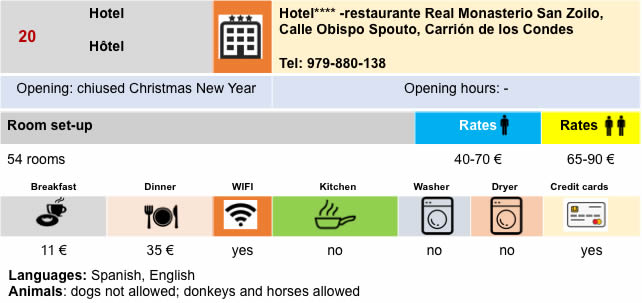

| On the way, the pilgrims, in great majority, spend the night in the « albergue”. There are many reasons for this. First of all, there is the price of accommodation, most often less than 10 Euros per night, in Spain. There is above all the spirit of the journey, this feeling of conviviality, of almost fusion where sharing, even that of meals, is often appropriate. But sometimes pilgrims make an exception to the rule, to find a little more comfort. So here, there is enough to satisfy your desires at the Real Monasterio de San Zoilo hotel, a **** establishment, which has very reasonable prices and which uses the monastery and its cloister. Even if this establishment is not part of the list of Paradores, these high-flying hotels, which use the infrastructures of old historical places, such as castles or cloisters, this one does not pale in comparison. So, let’s take a look around. |

|

|

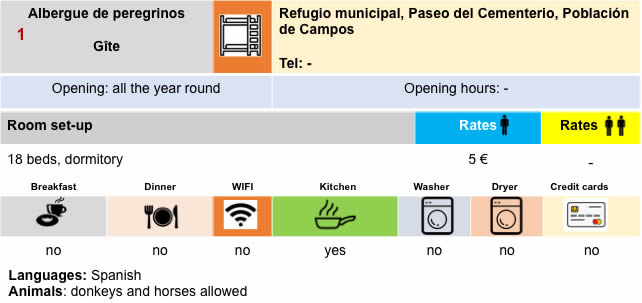

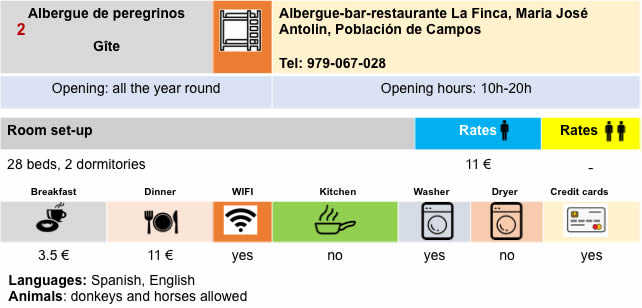

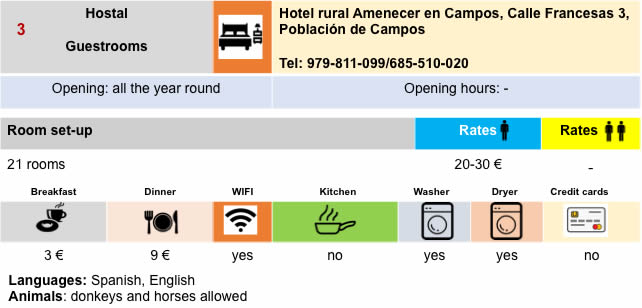

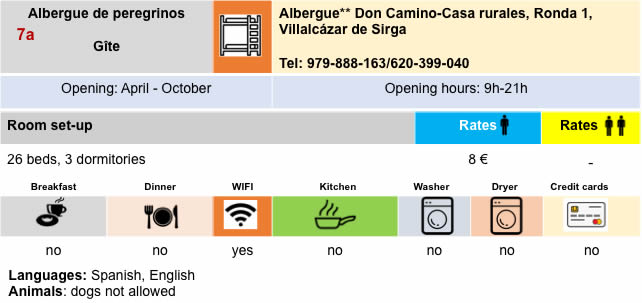

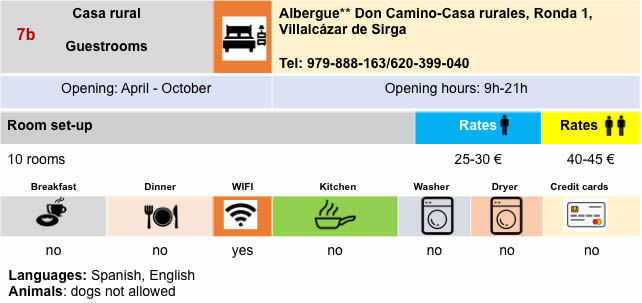

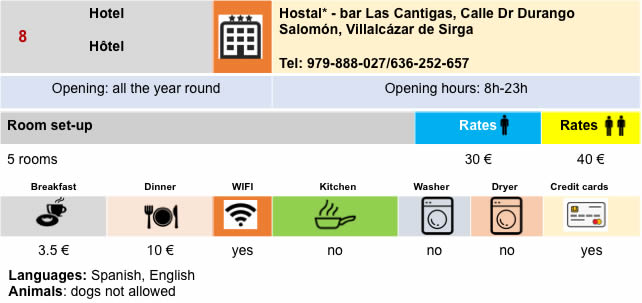

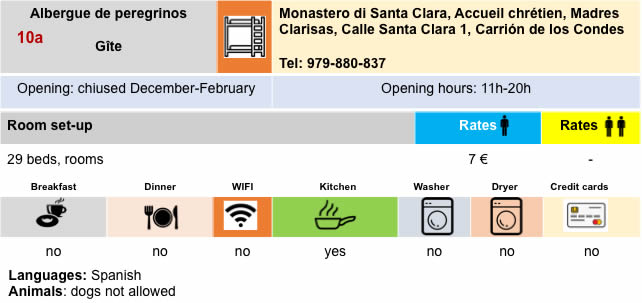

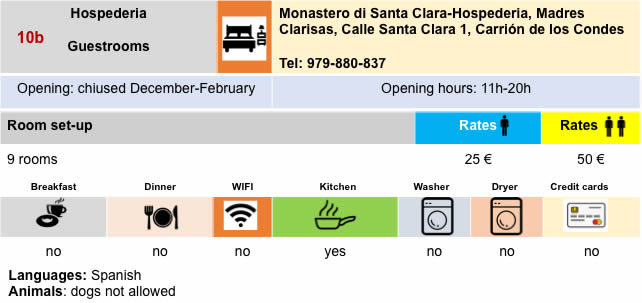

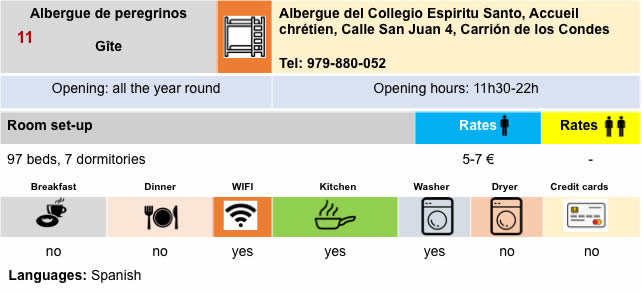

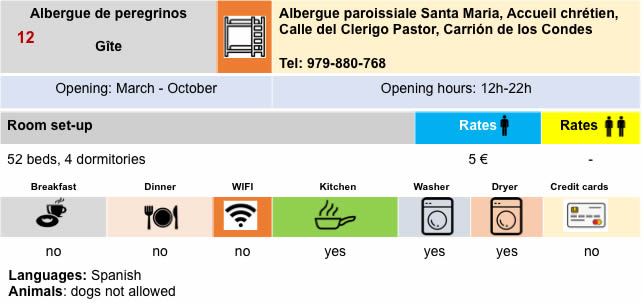

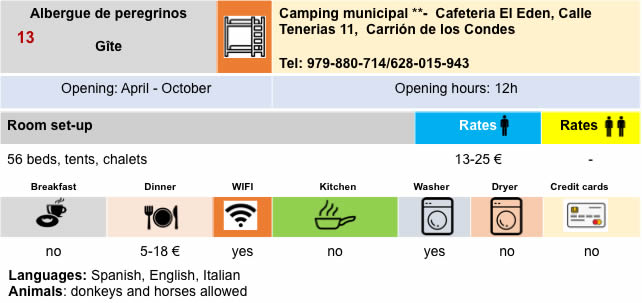

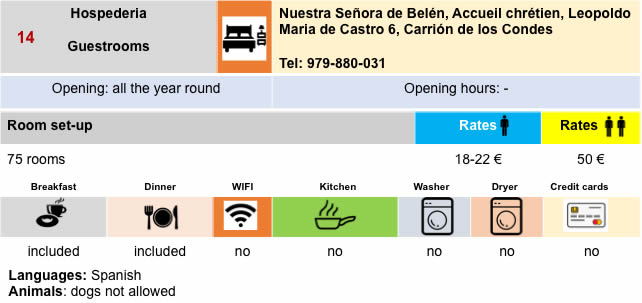

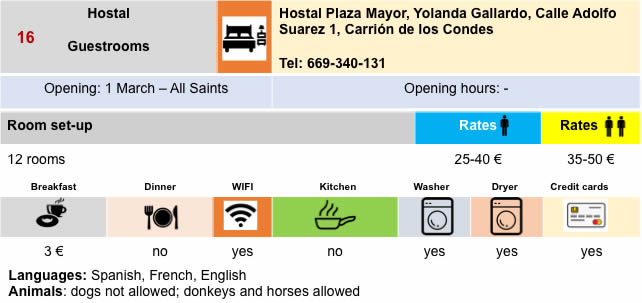

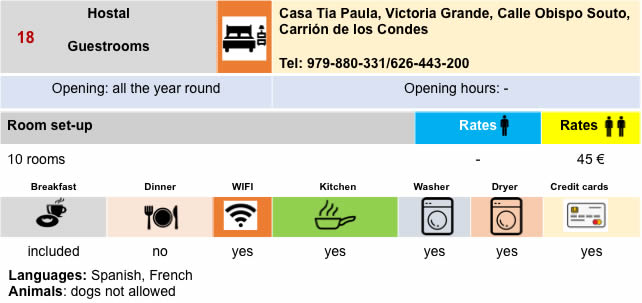

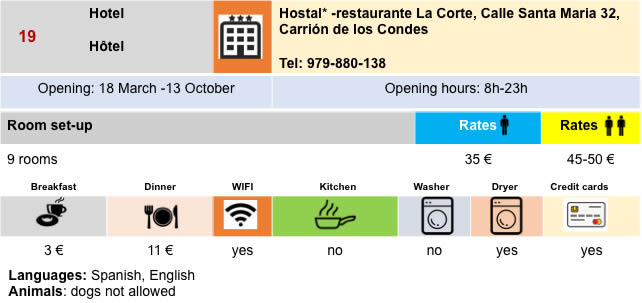

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 17: From Carrión de Los Condes to Terradillos de Los Templarios |

|

|

Back to menu |

The pathways, as they will be called, clearly dominate the paved roads:

The pathways, as they will be called, clearly dominate the paved roads: